OUR FIRST BIG MISTAKE WAS COMING DOWN OUT OF THE TREES

The British are a nation of nature lovers. That’s not to say other nations are necessarily less caring of their wildlife. It’s just that in the UK, there is a

proud if slightly eccentric tradition of studying and celebrating nature. Wildlife documentaries are blockbuster productions here; their presenters are popular celebrities and national treasures.

Birdwatching, rambling, horse riding, dog walking, sightseeing, rock pooling, pond dipping, or just strolling through the countryside delighting at butterflies and buntings, and picnicking in

flowery meadows, are mainstream activities. Gardening is probably more popular, or it certainly comes a close second.

According to all the surveys, ‘attracting wildlife’ into our humdrum domestic lives is a major driver of horticultural interest, and a major

commercial interest, what with all the merchants for birdfeeders, nest boxes, bat boxes, night-view trailcams, bug hotels, bumblebee boxes, mason-bee lodges and hedgehog houses. We love nature, and

we want to see it close up.

Something odd, though, happens at the back door. It’s fascinating to watch squirrel acrobatics along the fence and the birds squabbling at the seed ball; it is amazing to watch insects

jostling on the flowers – bees, hoverflies, butterflies and plenty of smaller fry – and it may even be acceptable to suffer a few nibbles in the nasturtium leaves from the large,

speckled caterpillar of a cabbage white butterfly, but our toleration seems to stop dead the moment any of these creatures has the temerity to step inside our homes.

A spider crawling up the wall off the recently cut flowers, a lone ant wandering over the kitchen table or a single fly buzzing in erratic zigzags under the light bulb is often enough to produce

immediate feelings of disgust and revulsion. While a gentle waft of the hand may be enough to dissuade a curious wasp attracted to the cream tea on the patio, it will have the occupants of a living

room reaching for the swat or the bug spray if it comes indoors. Sparrows are merely amusing figures of fun when landing perkily on the back of a garden chair and eyeing up the last of the

sandwiches, but if they start roosting under the eaves, or dragging nest material into the loft, they become vermin. The mouldering, beetle-chewed fence post at the end of the lawn can be ignored,

but a tiny, trickling pyramid of sawdust, just a milligram or two, beneath the exit hole of a woodworm under the stairs will elicit an immediate call to a pest-control agent. We do love nature, and

we do want to see it up close, but not that close.

To understand this apparently contradictory human reaction, we simply have to understand the difference between a dwelling being a house and it being a home. The most important thing about a

home is that it has become what anthropologists (and some entomologists, for example Robinson 1996) call a ‘sacred space’ – not a place of worship or

superstition or New Age mumbo-jumbo, but a private living space, shared by a family and entered only by invitation.

The barrier to the living space is traditionally a door, but this need not be an impervious block of wood; it may be a symbolic barrier like a draped cloth, balanced sticks or hanging strings of

beads. In almost every human culture a visitor must first ask permission to enter, before crossing the threshold into a family’s sacred space. The unwelcome are not granted access, and in

most societies violation of even a symbolic barrier is vigorously protected by law, so much so that ‘reasonable force’ (even armed force) can be used to eject intruders. It is no wonder

that insects (and other animals) that invade human premises without permission are viewed at the very least with suspicion, and usually with outright opposition and extreme prejudice.

This protective feeling about our homes is so deep-seated and widespread in human societies around the globe that it is hard to imagine it to be anything other than a truly ancient and

fundamental part of our very being. It is now not possible to know how and where the first door was put in place, but the temptation must be to suggest that wherever it was, it had to be defended

against intruders, both human and non-human.

The house, as understood in our modern world, is on the verge of becoming a hermetically sealed brick box. Double glazing, plastic- or metal-framed windows and doors, draft excluders, and cavity

and loft insulation all conspire to make entry virtually impossible, even to the smallest of insect explorers. Things were not always thus. So to get an idea of why we are invaded in our homes

today, we need to take a look at how human homes have come about in the first place, and where and when in our history (and prehistory) we first came into contact with the myriad intruders that

pester us and vex us today. So, by way of a slight digression, let’s start way back in time and consider our long-gone ancestors, and where they lived.

IN A HOLE IN THE GROUND THERE LIVED A … CAVEMAN?

Contrary to popular belief, mostly influenced by children’s cartoons and Hollywood B-movies, early humans did not all live in caves. Rocky overhangs and dark caverns no

doubt offered some shelter, but they were also the lairs of bears, big cats, hyenas and a wealth of other dangerous and highly non-domesticated tenants. There are some cave connections, but there

can be several explanations for this. Each new archaeological discovery puts another metaphorical brick into the housing puzzle of the past, but it’s not immediately clear where most early

hominids lived, because the fossil evidence is so sparse as to be sometimes almost non-existent, and what little there is can be difficult to interpret.

The latest in a series of typical caveman stories in the media was sparked by the discovery (by Brown et al. 2004) of tiny, human-like skeletons about 1m in length in a cave on the

Indonesian island of Flores. Archaeologists are still debating the finds, which date from ‘only’ 95,000 to 13,000 years ago, and which may or may not represent a distinct and separate

species, but even so the idea of humans and human-like creatures living in caves is firmly fixed in the minds of the general populace.

Before caves, though, trees would have been an obvious place for our ancestral primate relatives to live. A brief exploration of hominid development lays the foundation for understanding how, as

humans, we came into being, how we took over the world, and started building, making and owning the stuff we now have to protect from pests.

About 4 million years ago Africa was home to various humanish apes, some of which walked about mostly on two legs. This upright stance is one of the most striking characteristics that make us

human. The other is that we have only relatively light body hair; the two are possibly connected. At the time, those millions of years ago, this strange adaptation probably gave early hominids the

edge over their hairy shuffling ape cousins; Harcourt-Smith (2007) gives a good overview. One explanation is that on the hot, dry, lightly wooded savannahs of southern and eastern Africa, standing

upright took the head, with its rapidly evolving and energy-hungry brain, away from the radiated heat of the red, sun-baked African earth to catch the light breezes wafting

gently at what would now, conveniently, be head height.

Other possible reasons for the evolution of walking upright include standing up to look out across the savannah for danger, reaching up to pick fruits from trees, and carrying things in our arms

while we walked. Whatever the reason(s) for bipedalism, lack of body hair assisted those creatures on the hot, dry grasslands, and sweating became the paramount temperature-control mechanism for

the body; any fur would immediately impede this cooling effect. As naked apes, early hominids were quite at home in the tropical and subtropical glare of the African sun. We remain one of the few

mammals that can keep moderately active during the day in the hottest regions of the world, but lacking hair we have low cold tolerance. This adaptation would come back to haunt later humans when

they finally ventured into the cooler north.

Pieced together from scattered bones and bits of bones, various pre-human species have been described, the earlier ones usually in the genus Australopithecus, from the words meaning

southern (Latin australis) and ape (Greek pithekos), and echoing the old scientific name of the chimpanzee Anthropithecus (man-like ape). Some of the more dainty

specimens have been called Australopithecus afarensis and A. africanus, while more heavily built skeletons have been assigned to A. robustus. Even at their most robust,

though, australopiths were short – the males were around 1.2m tall, the females a head shorter.

There are suggestions (from fossils of slightly more curved finger bones and stronger arms than ours) that these early humanoids were more at home in trees than we are, but apart from a few

other inferences based on pelvic-bone shape we can know little about these creatures. Although mostly walking upright (and probably being mostly naked of body hair), they had proportionally shorter

legs than us, and a more shambling, less proudly striding gait. We do not know what they ate, where they sheltered (if at all) or how they interacted with the environment. The excellent Masters

of the Planet by Tattershall (2012) gives a good review of early human development as far as body structure is concerned, as far as we know it, but he is candid about how little we know of the

behaviour of our precursors.

The likelihood is that early humans were living wild on the savannah, without shelter, without homes, and at most making temporary roosts in which to sleep. Today, gorillas,

chimps and orang-utans make rough nests, little more than platforms of twisted vegetation or branches on which to spend the night. Darkness is a dangerous time, what with big cats and other serious

predators prowling about; diminutive australopiths would have done well to keep out of the way as best they could. The ‘nests’ of apes are used for only a few days at a time; they are

by no means permanent, and this is why the higher primates do not have fleas. Let’s just jump forward a few hundred thousand years to understand why we have them today.

FLEAS – WELCOME ABOARD

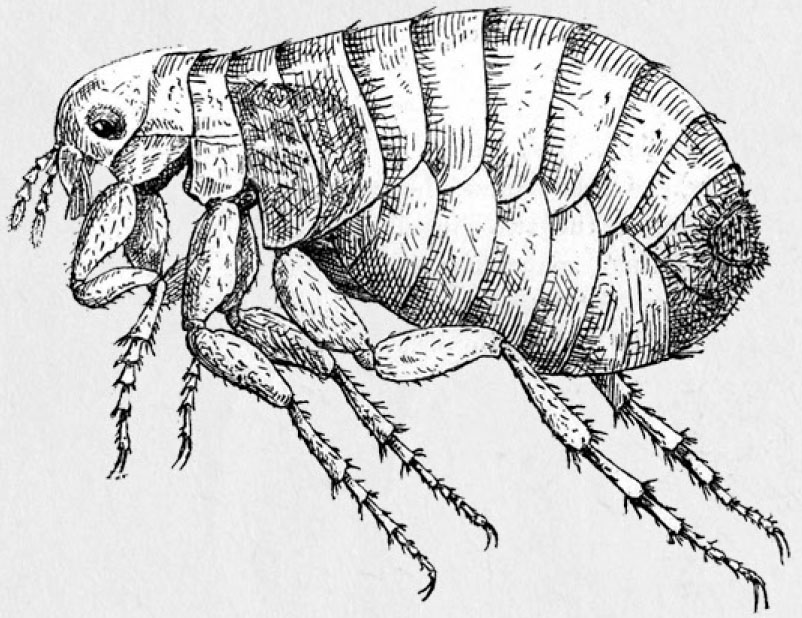

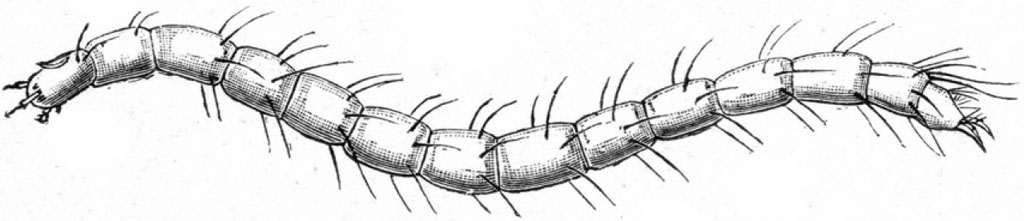

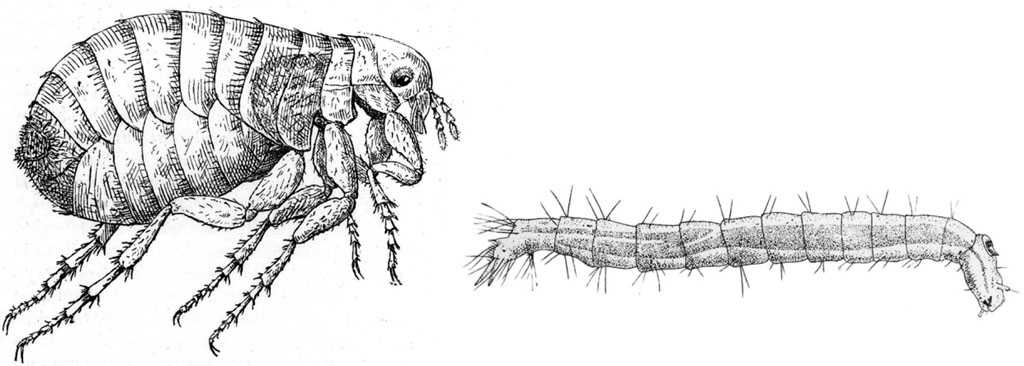

Modern humans are the only apes to have their own fleas. This is unfortunate, but is a direct consequence of our sedentary lifestyle. We do not, however, carry our fleas with us

wherever we go (that’s lice, see further on in this chapter). They jump aboard us to bite us and suck our blood, but really fleas are denizens of the nest. More particularly, only adult fleas

jump on us to bite; the tiny (1–2mm), pale, worm-like larvae wriggle around in the deep nest detritus. This is where a permanent host nest (a home) becomes important.

Fleas living on an animal (bird or mammal) drop their tiny, smooth eggs willy-nilly, to fall down into the nest. The fleas also drop copious dark squiggles of hard, dry faeces. Since blood is on

tap, as it were, the fleas feed freely, and their abundant excrement is little different from dried blood, still highly nutritious. A flea larva down below feeds on this secondhand blood, along

with any other organic matter like host droppings and rotten nest material, until grown and matured enough to change into a pupa (chrysalis). It does not, however, automatically emerge as a new

adult flea, but bides its time.

One of the features of birds and mammals is that they are active daily and seasonally, and there would be no point in a flea emerging from its pupa only to discover that its host had gone

walkabout for a month. Instead it waits, dormant, sometimes for many months, until vibrations indicate that the host has returned to take up residence again. Within seconds the

flea quickly shimmies out of its chrysalis and jumps aboard.

Anyone who has cats (more about them later) will recognise the phenomenon of returning from a few weeks’ holiday the pets having been shipped off to a cattery for the duration, and coming

back into the empty home to be met with what seems a sudden plague of cat fleas Ctenocephalides felis jumping up and biting the ankles. They have not been multiplying wildly while the

house occupants have been away, but have just been quietly reaching the end of their larval stage and waiting in their chrysalises. The vibrations of the returning humans trigger what has now

become a synchronised mass emergence, where before the continual trickle turnover would have gone unnoticed. Except maybe by the cats.

Dogs are not immune to this either; they have their own very similar flea, C. canis. I’m a cat person myself, so I’ve had plenty of cat fleas jump upon my bare ankles as I

pad around the kitchen making coffee first thing in the morning. There was a chicken flea Ceratophyllus gallinae, too, once, but that wasn’t indoors. I encountered it when I was

playing hide-and-seek in my grandfather’s chicken coops, and I guess my childish stomping gave the flea in its chrysalis just the right signals to encourage it to emerge. That one hurt, if

memory serves.

The flea life cycle is only possible in conventionally nesting (rather than merely roosting) species, which is why all the nomad great apes live flea-free lives. It was only because humans

returned, night after night, to sleep in the same shelter, and accumulated nest material in the form of bedding, that a human-based flea community could become established.

Astonishingly, this was only a very recent occurrence.

The human flea Pulex irritans is a rather adaptable flea, and a fascinating insect – I thoroughly recommend The Compleat Flea, by Lehane (1969). It certainly did not

start off sucking human or even Australopithecus blood.

There are about 2,600 flea species across the globe, most with varying degrees of host specificity. Fleas have been biting mammals and birds for over 200 million years, and had evolved their

modern shape and form by 40–50 million years ago. Busvine (1976) goes into plenty of helpful detail on how the bloodsucking habit of fleas and other insects might have evolved. Usually a

given flea species only occurs on one host species, although it might also occur on a small number of similar hosts. The mole flea Hystrichopsylla talpae, for example, only occurs on

moles, but the chicken flea occurs on a wide range of other bird species apart from chickens, and on the occasional child playing in a chicken house. The human flea is one of six species in the

genus Pulex, all of which originated in the Americas. Humans did not arrive in the New World to collect their fleas until about 14,000 years ago, when they crossed the land bridge between

present day Chukotka and Alaska as the ice retreated after the last ice age. But when they did, they soon picked up some Pulex from their original hosts – prairie dogs, peccaries and

guinea pigs (Buckland and Sadler 1989).

YOU ARE WHAT YOU EAT – HUMANS START HUNTING AND EATING MEAT

Meanwhile, from the Pleistocene epoch, many Australopithecus bones (and those from later humanoid species) have been recovered from caves and subterranean pits.

They’re still not cavemen bones, though. Various ideas are put forward. Streams and rivers that dried up long ago may have washed the scattered bones into the caves along with general debris

during seasonal floods, or the unfortunate australopithecines could have been the victims of big-cat attacks, the bodies having been dragged down into the darkness to be devoured later. Caves,

silted and in-filled with rubble, offer good preservation conditions over the aeons, and the bones remained moderately well preserved until excavated by excited archaeologists. But these were not

homes.

By 2 million years ago more human-like primates had appeared. So like modern humans were they that they are generally included in our own genus – Homo. Various species names are

bandied about, including Homo habilis and H. erectus. They were erect, but still some way off modern human height, with various estimates of around 1.5m.

At this point in time their diet, as suggested by their teeth, was very similar to that of the predominantly (but not all wholly) vegetarian large apes we still know today – gorillas,

chimpanzees and orangutans. A knowledge of pre-human diet is important for us because it gives clues to the beginnings of food preparation and storage, and a prehistoric technology that would

eventually produce long-term shelters – homes. Two million years ago was roughly when human tool making began, with bashing one rock against another to make a sharp edge. At first,

technological advance was very slow, and it took another million years before typical ‘Stone Age’ sharpened flint fragments appeared regularly. The presence of these blades begs the

question of what the early humans were cutting. The usual suggestion is that they were butchering animals for food.

This immediately summons up, to the mind’s eye, caricature images of unkempt, hairy (but not furry), brutish-looking people clutching wooden clubs, and casually dressed in draped animal

skins knotted fashionably at the shoulder or cut to make loincloths of varying modesty. Too much of this is ill-informed myth. Meat eating (the obvious precursor to wearing

fur) is so commonplace in modern societies that it is difficult to imagine how it began. It certainly did not start by some epiphany for a lone Stone Age forager wielding his club or launching his

flint-tipped spear into the succulent and deliciously nutritious flank of a gazelle, thus suddenly elevating him from mere gatherer to the new-found iconic status of hunter. It seems much more

likely that early humans stole kills (or at least bits of kills) from proper predators like lions and leopards.

Evidence for this comes from the unlikely study of tapeworms, the disturbing and distasteful gut parasites that feed the nightmares of many a squeamish new biology student. These huge intestinal

worms are highly species specific, and at one time it was thought that humans acquired their several species with the domestication of cattle and pigs, only around 10,000 years ago, ingesting the

egg-like larval cysts by eating the poorly cooked beef or pork meat in which they lodge. The flat, many-segmented worms developing in the human digestive tract can reach about 6m in length;

segments full of eggs break off and are passed in the faeces. In the close human/animal confines of the shelter/barn or shelter/sty, the eggs soon get accidentally swallowed by the stock animals

and hatch in their stomachs. The tiny worm embryos migrate out through the body to the muscle tissue, ready to be eaten by the next hungry person.

In fact, molecular analysis of these worms (Hopberg et al. 2001) across a range of mammal hosts shows that humans had tapeworms long before this, and that it was probably us who gave

tapeworms to our stock animals. Humans picked up tapeworms from the same sources that lions, hyenas and wild dogs got theirs – from eating antelope or gazelle meat – and at a time well

before stone (or indeed any) tools. The implication is that meat eating began as meat scavenging. Animal carcasses attract a huge variety of scavengers, including (after hyenas, vultures and

humans) plenty of insects like flies and beetles. When early humans were using their small stone blades to slice morsels from freshly abandoned kills on the lightly wooded African savannah, it did

not matter what came along to feed after them, but the moment they started to bring home the bacon (or venison, or beef or whatever), including any skins, horns, antlers,

tendons, hooves and all the other useful bits, they were positively asking for trouble. We’ll come back to this interesting larder-centric relationship later.

From about 600,000 years ago, the human fossil record becomes a little more enlightening. This is the era of the almost-modern humans – Homo heidelbergensis and H.

neanderthalensis. H. heidelbergensis, although named after the illustrious city in south-west Germany where a fossil jaw was first found in 1908, was the first truly cosmopolitan human. Other

modern-type human (Homo) fossils have been found scattered piecemeal across Africa, Europe and parts of Asia, but H. heidelbergensis was the first nearly worldwide human. This is

notable because it coincides (roughly) with the apparently worldwide spread of a new stone-shaping technology (Acheulean, after the French town of St Acheul, where it was first excavated and

identified) of large hand axes and chopping tools. What were they chopping? At a similar time humans may have started to understand, and maybe even ‘use’ fire. Were they chopping

wood?

The current earliest known example of what is thought to be human use of fire comes from an apparent hearth at an 800,000-year-old site in Israel, but this is rather an archaeological outlier,

and real evidence of regular controlled fire does not appear until about 400,000 years ago. Now, however, things start to get interesting, because this is also the time of the earliest documented

human shelter.

THE FIRST HOMES AND THE FIRST HOME BUILDERS

The several ancient shelters, as they are fancifully reconstructed in the imaginative minds of palaeoanthropologists de Lumley and Boone (1976), were built about 350,000 years

ago at the archaeological site of Terra Amata, in what is now Nice, in the south of France. A small group of hunters seems to have returned every so often to the site, but unfortunately left no

traces of themselves. Each shelter is defined by a large, oval ring of heavy stones anchoring cut saplings that were embedded into what was at the time a sand and pebble beach. The presumption is

that the saplings were drawn together overhead to create a hut that could shelter 20–40 people. There is conjecture as to whether the construction would have been covered

with animal hides or turf, or thatched with leaves, but there are no remains to indicate any of this.

What is most interesting, however, is that a gap in the stones demarcates a doorway, and just inside this is a shallow, scooped-out hearth, multilayered with ash, surrounded by blackened cobbles

and containing burned animal bones. Here are tantalising echoes of our sacred space, with its entry portal open to guests, but protected by flames against intrusion from … what? Prowling

animals? Prowling enemies? Howling wind? Biting flies? We still don’t know quite enough, and there are plenty of arguments about the shelters’ exact age, form and use, but this

important excavation marks at least a theoretical start to the notion of home building. We’re still not quite ready to leave the caves, though.

Around 150,000 years ago those most famous of ‘cavemen’ start to appear – the Neanderthals. Homo neanderthalensis is so well known to us because although it has been

found as far afield as present-day Israel and Iraq (but not Africa), it is really Europe’s endemic proto-human, and finds in the abundant caves of France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and

Spain have fixed it firmly in our consciousness.

The most striking thing about any reconstructed Neanderthal image in textbook or museum displays, apart from the prominent, stern-looking brow ridge, is that these people are usually portrayed

(as per caveman stereotype) wearing animal-hide clothes and carrying flint-tipped weapons. There is at least some archaeological evidence for these.

Neanderthals made Europe their home at a time of world cold – during the series of regular ice ages that have characterised the northern hemisphere for the last 3 million years, since the

tectonic plates of South and North America met to create the Panama isthmus, thus blocking out the warm circulating currents from the Pacific Ocean (Van Andel 1994). Incidentally, this same

tectonic event earlier started the cooling and drying of Africa that transformed copious lush tropical rainforest into the savannahs where delicate (or robust) Australopithecus could

evolve.

Several things seem to have allowed the Neanderthals to survive so far north. Their stout, stocky body form (they were seriously squatter, larger and heavier than modern

humans) gave them some advantage in conserving body heat. However, they would have had to be sumo wrestlers in size and blubber content to feel comfortable in those skimpy loincloths. It is much

more likely that they wore warm clothes – the discovery of stone scrapers and piercing awls certainly suggests that they were preparing and stitching animal hides. Coincidentally, rickets, a

distorting disease of the bone joints from lack of vitamin D, also starts to appear, and since this vitamin is synthesised in the skin as a response to sunlight, covering the body with heavy,

lightproof clothes appears to have been the cause.

Later humans, the Cro-Magnons, modern Homo sapiens to all appearances, colonised even further north and were well clothed, with tunics, leggings and cloaks decorated with beads,

according to the archaeological records from their burials. The emergence of clothes would later usher in the era of clothes-destroying insects, but we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves

here – first let’s look at some clothes-infesting animals.

LICE – CLOSE UP AND VERY PERSONAL

The discovery of Neanderthal awls and Cro-Magnon needles dating to 100,000–40,000 years ago, and the suggestion that this is when humans first put on clothes, fits in very

nicely with the evolution of perhaps our oldest personal guests – lice. Unlike fleas (see here), which hop on and off as the mood takes them, lice never leave

the human body unless it is to move to another human brushing or lying against it. They never let go; only the death of the louse or the host will ever induce a louse to relinquish its hold

(Maunder 1983). Consequently, we have had lice from a time before we were remotely human, and long before we ever settled down to make homes.

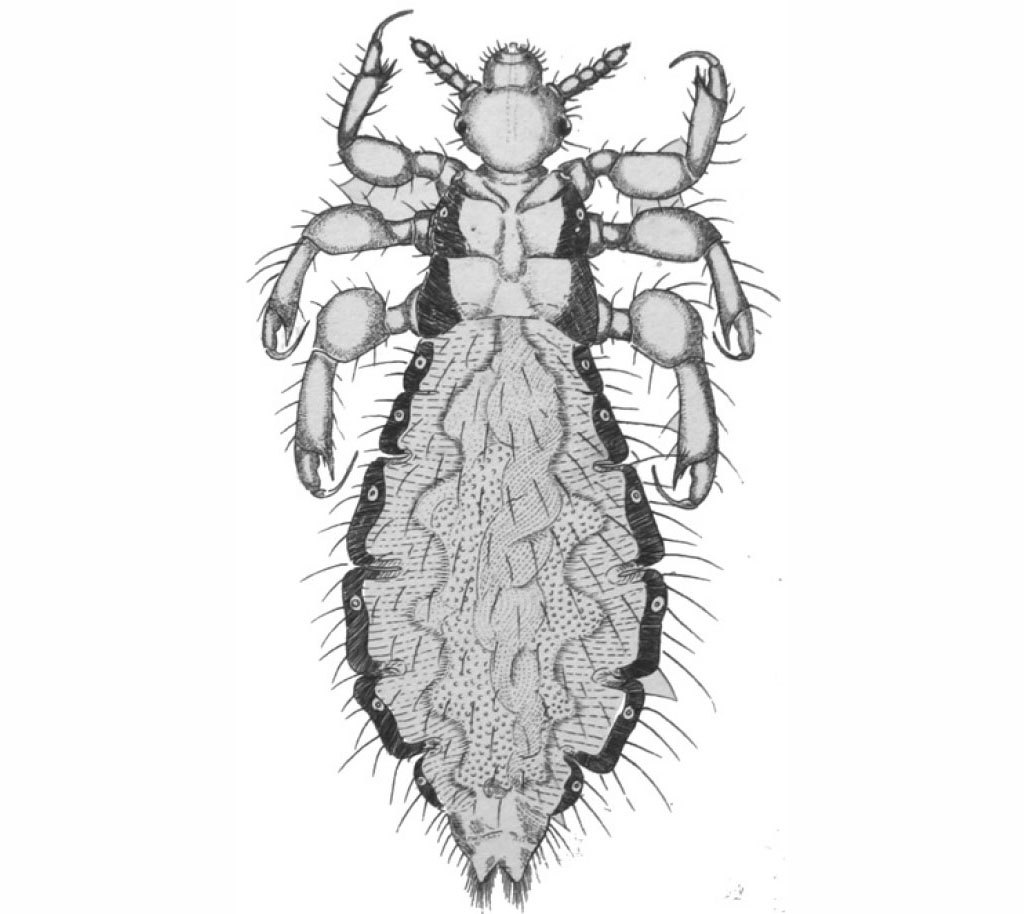

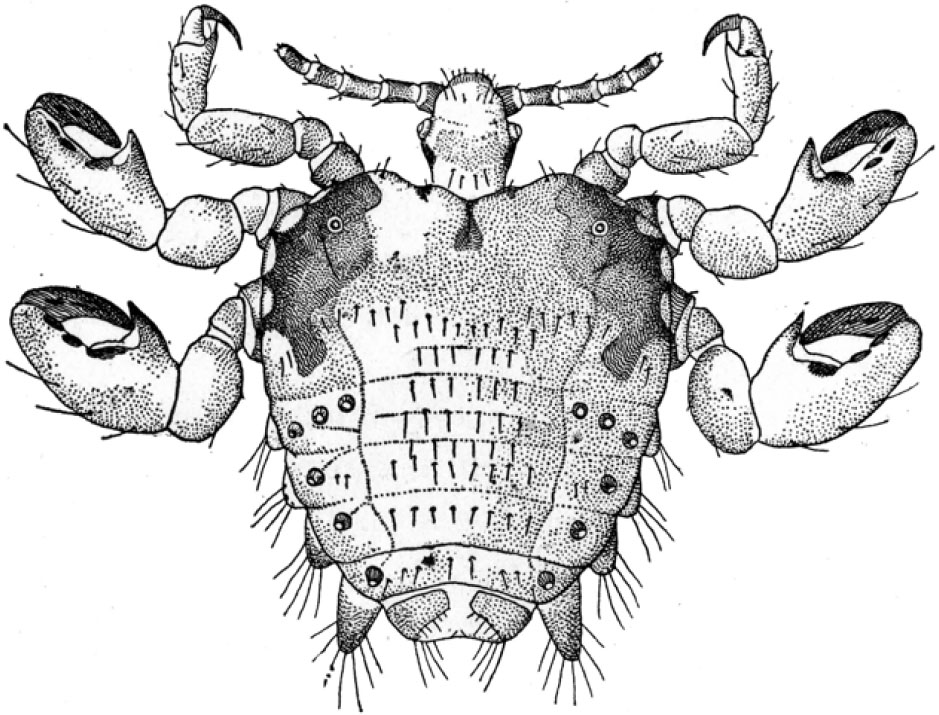

Humans are host to three louse species – the crab louse Pthirus pubis, the head louse Pediculus capitis and the body louse P. humanus.

The crab louse, sometimes also called the pubic louse due to its preferential occurrence around the nether regions, is a short (2mm), squat beast, and despite its name is really the generalist

louse of coarse human body hair. It has stout, powerful claws for gripping the thick, fairly well-spaced hairs of the groin, but can also occur on men’s hairy chests, and in beards, armpits,

eyelashes and eyebrows. It’s generally agreed that the crab louse is just about the most embarrassing insect in the world, so enough about it here.

The head louse is all too familiar to anyone with school-age children. It occurs on heads, and its claws are perfectly sized to grasp the much finer, more tightly packed hairs on the human

scalp. It’s an annoying nuisance, for sure, but completely harmless, and does not transmit any diseases. In The Little Book of Nits, Jones and Crow (2012) try to placate parents and

dispel some of the many myths surrounding this irritating insect. There is an uneasy repugnance at the idea of tiny creatures living in your hair, but this is a modern phenomenon of a fastidious

Western society that finds it unacceptable to scratch the head at the dinner table. I take a certain scholarly pride in claiming that I am alone, as far as I know, in being the only person who has

ever exhibited a live head louse, plucked from their own head, at a meeting of a national entomological society (Jones 2001).

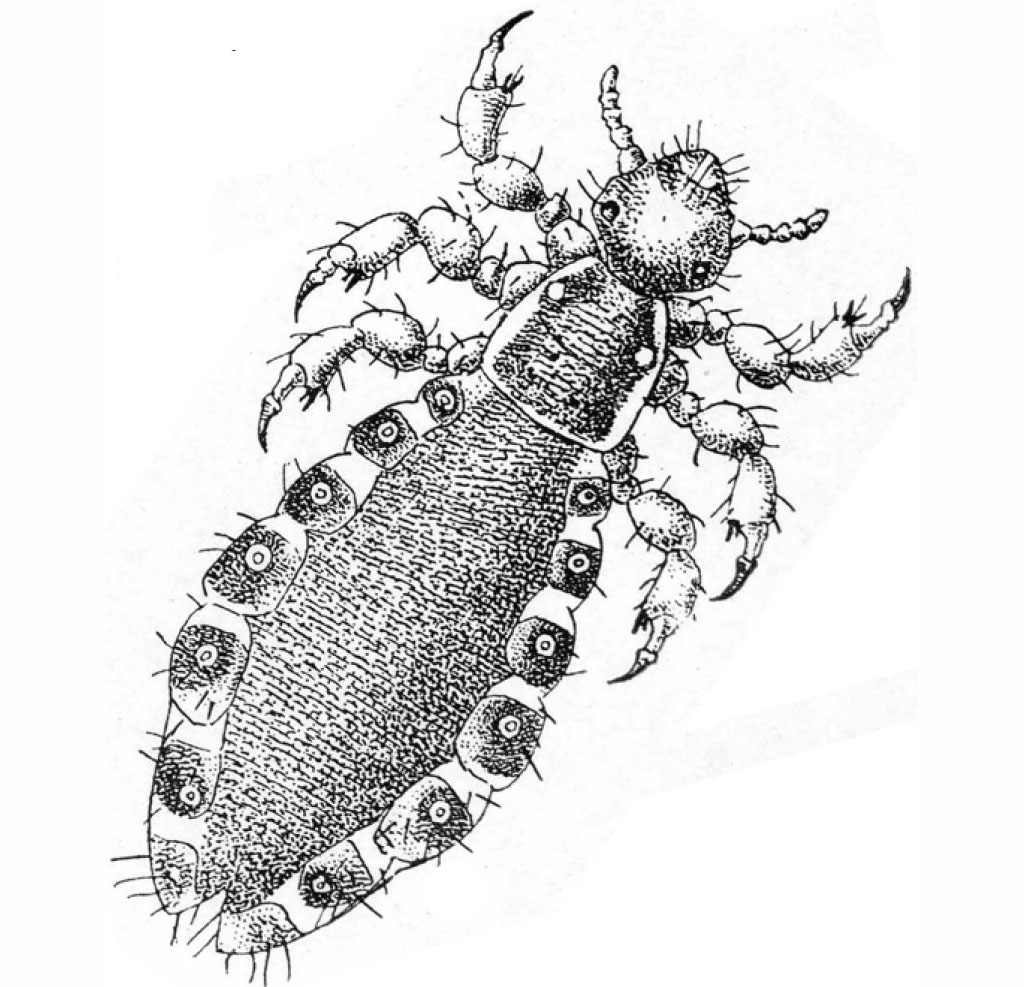

Thankfully the body louse is all but extinct in modern society. This is a nasty, unpleasant creature. It transmits typhus Rickettsia prowazekii, trench fever Bartonella

quintana and relapsing fever Borrelia recurrentis, bacterial diseases that breed in the guts of the louse but infect human victims through cuts in the skin when the louse is squished

during scratching, or by contamination with its copious bloody faeces. Busvine (1976) gives lots more gory details. Typhus epidemics throughout history have killed countless millions. Up until the

middle of the 20th century it was the louse of the morbidly unclean, the homeless, the pitifully squalid and the unwashed poor, but also of the soldier in the trenches (hence

trench fever), the famine victim and the refugee; this is the louse of natural and man-made disasters.

Although almost identical to the head louse, the body louse differed in one very important aspect – its behaviour, because instead of living on heads, it lived in the clothes. In fact

‘clothing louse’ would be a more accurate name for it, a conviction echoed in an old scientific name, Pediculus vestimenti. Ironically, it is the easiest louse to get rid of.

All you need do is change your clothes, but people who suffered from body lice were the victims of situations where they could not take off their clothes for many weeks, and even months; the

clothes they stood up in (or lay down in) were probably the only possessions they had. Louse infestation rates could reach appalling proportions in the occasional hapless person, and it was not

uncommon for grim cleansing stations to report numbers of 30,000 body lice on a single individual.

There is still a certain squeamish shame attached to head lice, even though they actually do better on clean hair than on matted locks, and afflict middle-class children just as much as

working-class kids. Part of this embarrassment is due to the close resemblance of the head louse to the body louse, and the fact that in the past the two have sometimes been regarded as one and the

same species, just different subspecies or races. The differences between them are extremely slight: the adult body louse is usually slightly longer (2.3–4.1mm) than the adult head louse

(2.1–3.3mm), but there is considerable overlap; in the laboratory head and body lice can be induced to interbreed, producing intermediate lice.

It is only through the advance of DNA studies that we can now see clearly how head and body lice are different. They have very similar DNAs, showing that they are indeed very closely related,

but subtle differences in the double helix sequences have accumulated over evolutionary time. These changes (mutations) in the DNA strands of all organisms are well documented,

and occur at a low but more or less constant rate over the aeons. By comparing DNA sequences, and counting the minor differences between head and body lice, it is possible to extrapolate backwards

in time to estimate where the ancestral lineages of the two creatures meet – how long ago they shared a common ancestor. By these calculations (Kittler et al. 2003), body lice

evolved from head lice about 70,000 years ago (give or take a few millennia). This, coincidentally, was just at the time when Homo neanderthalensis and slightly later H. sapiens

were making themselves at home in the cool Eurasian wilderness, sitting around the fire, and cutting and stitching animal skins to make themselves something warm to wear – putting on the

first clothes.

REAL CAVEMEN LIVED IN FRANCE

Back in the cave, despite fur coats it is dark and gloomy, and the cold, hard starkness of bare rock doesn’t look very enticing to modern eyes. It’s tempting to

assume that the Neanderthals introduced at least some creature comforts to make life worth living. Animal fur bedding sounds about right.

The Neanderthals excelled in Mousterian stone technology, named after the French site at Le Moustier, in the Dordogne. This skilful working of hard stone produced razor-sharp cutting and slicing

implements, and elegant long blades that look very like spearheads, to the point where it is generally accepted that the Neanderthals were successful hunters. Indeed, chemical analysis of their

bones shows that they were probably top predators; it’s all to do with different nitrogen isotopes accumulating in carnivores as opposed to herbivores. Neanderthals’ arm and shoulder

structure implies that they were spear thrusters rather than spear throwers; nevertheless they appear to have been capable of ambushing and bringing down mammoths and woolly rhinos, which were

quite the most fearsome creatures of the day.

Evidence of healed and fatal bone fractures in the skeletons of the fearless Neanderthal hunters testifies, down the millennia, to the dangers of the large-mammal hunt using close-range stone

weapons. But when the big game was caught (and skinned), a veritable feast ensued, and judging from the increasing frequency of hearths, the feast was cooked on an open

fire.

Cooking using fire is a clear indication that food, both animal and plant material, was being brought back to the home base for preparation. This may have also been the start of smoking and

drying to preserve meat and fish for later consumption – unless the food-storage pests got in there first. Even if the hunted and gathered food was consumed relatively quickly, it would still

have offered plenty of opportunities for the unwelcome attentions of any local scavenger pests. As anyone who has lived in rural France will attest, leaving the supermarket shopping out on a work

surface for a few minutes is a clear invitation for house flies to come and settle. Even in the dubious semi-darkness of the cave entrance, any food left unattended for a moment would have been

abuzz.

All these clues to Neanderthal cuisine and loincloth fashions indicate, through the hazy window of patchy prehistoric archaeological remains, that although faced with an inhospitable or

inclement climate these people were coping. Not only did they cope, but they also coped very well, enough to see them through 100,000 years, more than twice as long as ‘modern’ humans

have been about in these latitudes. They coped by using the ingenuity of human (or pre-human?) inventiveness. They sought shelter in the cave openings and overhangs (French archaeologists have a

special word for them – abri, from the Old French abrier, to shelter); they warmed themselves using animal pelts for clothing and probably for bedding too, and they warmed

their ‘homes’ and prepared their food using fire.

Just as an aside, the common association, in the modern mind, of Stone Age peoples living in caves has much to do with European cave paintings. These actually came later, with the appearance of

the Cro-Magnon people, a race of modern humans (Homo sapiens) that migrated out of Africa only about 40,000 years ago. The caves (occupied from about 33,000 to 11,000 years ago) were

obviously special to the Cro-Magnons, but they were certainly not homes. The cave paintings are not domestic murals; they are seriously weird and symbolic images painted by the disciples of some

lost and forgotten shamanic ritual. And the painted caverns are deep underground, so deep that they could take an hour of walking or crawling to get to, clutching feeble,

guttering tallow torches. No one could live here. They were claustrophobic, cold, dark, dangerous places.

On a cheerier note, camping would have had all the advantages it still has today – you travel light; the tent or bivouac is quick and easy to establish; the materials are cheap, or at

least readily available to hunt and forage; you have all the ease of healthy cooking over a barbecue or fire pit, and you can move with the seasons or with the hunting, or when you’ve got

bored, or when the latrines and middens get too smelly.

Judging from ‘recent’ (that is, in the last 1,000 years or so) nomadic hunter-gatherer societies, seasonal migratory moves could follow the prey herds and the constantly changing

forage crops. Easily dismantled, transported and reassembled shelters like tepees, wigwams, yurts and gers offer a fine balance of comfort with manoeuvrability. They still have their unwelcome

visitors, though, climbing in through the flimsy animal-skin door or crawling through the air and smoke vents. It’s not too much to imagine similar structures punctuating a Neolithic

landscape 50,000 years ago. It’s difficult, though, to imagine how any traces of them might be preserved for modern archaeologists to argue about.

There are precious few finds. We do, however, know that the ‘modern’ Homo sapiens (Cro-Magnon and other groups) moving out into Eurasia 40,000 years ago were skilled makers

of all manner of artefact – a range of elegant yet practical tools made from stone, bone, antlers and wood, including hooks, harpoons and rope. It is only as we move towards the

‘modern’ era that a scattering of shelters is unearthed, some of which might be considered semi-permanent. Among the most unusual shelters we know of are the mammoth-bone huts of the

Russian plains, built some 15,000 years ago. Excavations of massive bone piles at several sites show circular structures of 150–650 interlocking mammoth bones weighing up to 20 tonnes, using

a heavy base of stacked jaws and skulls, and surmounted by a superstructure of arching tusks and timber, presumably covered with skins or turf.

The idea of these huge piles of mammoth bones might jar with modern readers wondering at the killing power of a few people armed with stone-tipped spears. There is a rather

romantic idea that aboriginal peoples had little effect on the environment, and that their hunting schemes were somehow in balance with nature and ultimately sustainable. However, whenever humans

arrived at a new ‘empty’ land, like they did in Australia (40,000 years ago), the Americas (15,000 years ago), New Zealand (3,500 years ago) and Madagascar (2,500 years ago), it did not

take them long (just a few centuries) to wipe out many species of large, but slow, megafauna. The overhunting of mammoths and woolly rhinos (and all the other large animals) by Neolithic humans has

been termed the Pleistocene overkill (Martin and Klein 1984), and although it may have provided meat, skins and building bones aplenty for many generations, it would later become one of the driving

forces behind the change from hunting to farming considered in the next chapter.

Modern mammoth-bone shelter reconstructions (Fletcher 1993) indicate that it might have taken ten people about 15 days to build a settlement of half-a-dozen shelters, and that once completed

they would have been weatherproof and snug enough. They don’t, however, indicate more subtle attributes, like the smell.

Bones are not without a certain odour – this was, after all, a temperate region, and bones left out in the open did not become sun bleached and sterile as they do in a desert, say. Modern

noses might be unaccustomed to it, but bone smell was familiar to all right up until well into the first half of the 20th century, when large industrial factories were rendering cow, pig and horse

bones for glue. Textbooks of the time (for example Hinton 1945) list the many scavenger beetles that populated the bone-works. Although these beetles no longer feed on our stored bones, some of

them are the same beetles we still find in our kitchens today, namely hide, bacon and larder beetles (more on them later). It is tempting to imagine that these same beetles were attracted to the

mammoth-bone huts, and fascinating to consider what the occupants called them in their archaeo-Siberian tongue.

Smell is something that the already disjunct archaeological record cannot preserve. However, this primordial sense is what first brought so many domestic pest (and guest) species into the lives

of humans. It is also the smell that might have first alerted humans to the idea that some of these visitors were less than healthy.

THE SMELLY EDGES OF SOCIETY

Back in the Stone Age camp, flimsy timber-framed shelters, roofed with hides, turf or thatch, continue not to leave archaeological remains; burial mounds have not been invented

and traces of human day-to-day activity are very thin on the ground. Nevertheless, wherever humans go they do leave traces of themselves – in their litter. The best signs of a prehistoric

human presence in the landscape often come from dumped rubbish. This may be in the form of huge coastal seashell middens (Waslkov 1987) accumulated over centuries (millennia even), or small piles

of broken stone tools mixed with butchered animal bones. Eventually pottery shards would start turning up too. The discarded refuse of human enterprise still says much about us today; looking

backwards it lets us surmise what our ancient ancestors were doing, and also how they were tested, early on, by the pests that still pester us.

Anthropologists and sociologists use a neat turn of phrase that is precisely apt here – the septic fringe (Robinson 1996). Today this may well mean the dishevelled, rambling, often lawless

sprawl of the shanty town. In tropical conurbations it is still associated with squalid living quarters, lack of waste disposal and sewage facilities, contaminated water, poor hygiene, and diseases

spread by rodent and insect pests. In prehistoric times it meant the edge of the settlement, the place where unwanted rubbish was dumped, and as well as broken tools it contained food waste, both

cooked and uncooked.

Harking back for a moment to pre-humans scavenging their first tastes of animal flesh from lion kills on the African savannah, meat eating is not without its dangers. It does not take long for

raw meat to become inedible, then toxic, and cooked meat also goes off pretty quickly. Humans, right the way back in their ancestral history, have never been adapted to eating the rancid meat that

wolves and foxes down quite happily. Our herbivore forerunners had already evolved long, convoluted intestines to assist in vegetable digestion – intestines in which toxins easily build up to

create food poisoning if we get our meal choices wrong. The smell of rotten meat (second only to the smell of dung perhaps) rightly repels us, an instinctive warning that it is not good to eat.

Smells from the Palaeolithic midden would have been fairly strong too, enough to tell our ancestors that the dumped food scraps were beyond edibility, and probably enough to

suggest that anything living in the refuse was not worth befriending. Here, then, would have been humans’ first contacts with so many of the noisome nuisances we still have today –

house flies, blow flies and cockroaches. This would be the metaphorical back door into human societies, before an actual entry into the real front door of the hut was tried later. The chances are

that this is how dogs got inside our homes.

WHEN DID WE LET OUR BEST FRIENDS INDOORS?

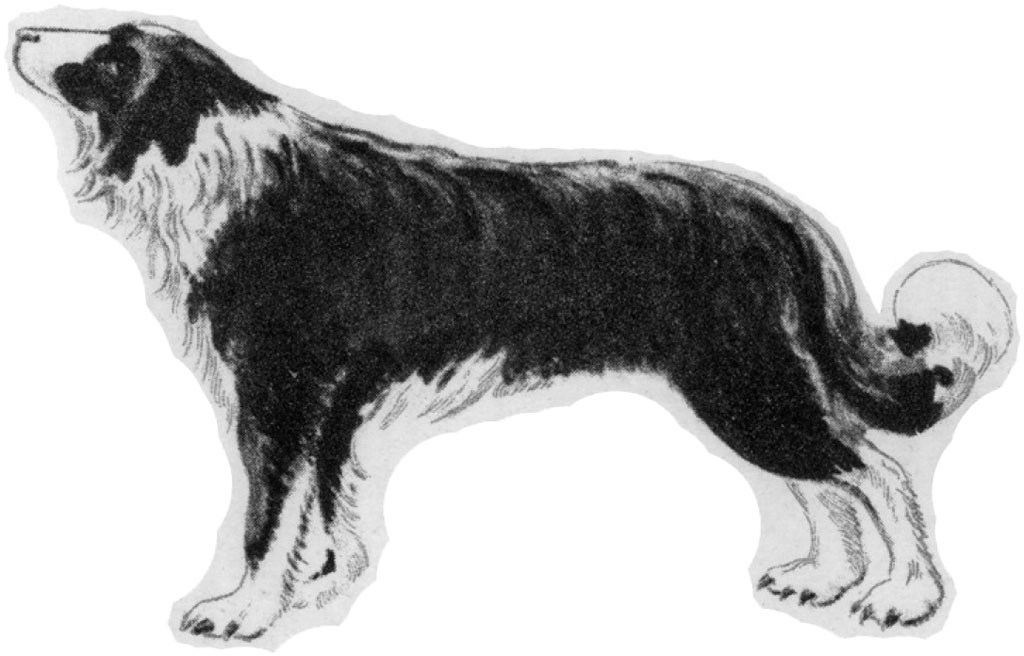

Dogs are now part of every human society across the world. Irrespective of rules set down by the Kennel Club and other official dog-breeding groups, they occur in all shapes and

sizes, and most colours and patterns, and have been used for everything from hunting to fashion accessory. But they are all dogs, all one, single interbreeding species, as demonstrated by unlikely

crosses of the chihuahua with the bulldog, standard poodle with the St Bernard, and doberman with the basset hound. It is no surprise to discover that modern dogs are descended from wild grey

wolves Canis lupus, and whatever their pedigree status all domestic dogs go by the scientific subspecies name Canis lupus familiaris, sometimes shortened to just Canis

familiaris.

What is perhaps more surprising is the fact that although archaeologists have uncovered dog-like (but still also quite wolf-like) remains in close association with humans from about 35,000 years

ago in Belgium, Ukraine and Russia, all modern dog lineages are actually descended from a single domestication event somewhere in Eurasia only 15,000 years ago. It would seem that for very many

millennia, humans had almost-wolves for pets, but true dogs only became our best friends much later.

There are several ways in which wolves could have first come into contact with humans, and become domesticated. They could have met at a carcass site, either group having

made the kill, but the other hoping to scavenge or thieve. Wolves could have come into conflict with people during particular hunts, for example on the seasonal migrations of prey animals like

reindeer. Wolves are curious animals, and although wolf attacks on humans are exceedingly scarce today, they have probably happened occasionally from time immemorial, with the possible consequences

of humans seeking revenge or removal of the perceived threat. Cubs left after such an incident could have been taken alive for trophies, talismans or playthings. Humans and wolves are both pack

animals, loosely based around family units, with a pecking hierarchy enforced by violence or threat; wolf cubs would have fitted in very well with a pack of hunter-gatherer humans.

An intriguing bit of genetic evidence, however, suggests that they may have first come face to face over the septic fringe, the midden rubbish heap at the edge of the camp. Dogs, as is well

known, will eat anything; wolves, on the other hand, are carnivores. Dogs can easily digest starch in the form of bread, rice, potatoes and the like, but this is a recent physiological trait, one

that has apparently been selected for by humans. Wild grey wolves do have two copies of the gene that codes for the starch-digesting enzyme amylase, but dogs have up to 30 copies. The implication

from the researchers that carried out the DNA analysis is that any wolves that scavenged and could successfully process starchy food bits thrown out by humans would have the advantage over those

that could not.

In good old natural-selection style they were more likely to thrive and pass on this ability to their similarly more successful offspring, who would continue to frequent the food-giving middens.

At this point other selective pressures also came to bear on the increasingly human-acclimatised wolves. Flight distance decreased – this is the physical distance at which an animal feels

threatened enough to run away from danger. It can be decreased by learning from a young age, but there is also a propensity in there, under genetic control, or at least under genetic influence.

Connected to aggression (fight or flight being the two best responses to danger), flighty or aggressive wolves would not have been tolerated even at the encampment’s rubbish dump.

.By comparing the genomes of wild wolves and domestic dogs, the starch gene scientists (Axelsson et al. 2013) identified 36 regions in the DNA that probably

represent real genetic changes caused by human selection (selective befriending and selective breeding). Nineteen regions contain genes important in brain function (eight controlling nervous-system

pathways and potentially underling behaviour), and ten genes had key roles in starch digestion and fat metabolism.

Since the rendezvous at the rubbish dump, wolves have become dogs in various structural ways too. Today’s breeds are the result of many centuries of increasingly selective breeding to

produce animals for various purposes. In their (our) history dogs have been used for tracking, hunting, herding, guarding, companionship and warmth, as beasts of burden and occasionally for their

flesh or skins (Millais 1911 recommends dog skin for the projectile pouch of a handy catapult). The huge variety in body shape, form and mass of modern dogs belies the fact that there are several

key changes that have been orchestrated right across their range. They mostly became significantly smaller (as too did domesticated cattle, sheep, goats, horses and pigs a few millennia later), the

jaws became shorter (initially leading to teeth crowding, but eventually to smaller teeth) and the skulls shrank, leading to smaller brain size. Maybe without the need to cope with the

‘wild’, domestic dogs don’t need to be so wily. They do, however, need to be calm, friendly, loyal to the pack (now their human family) and able to digest processed, often

starch-based pap delivered to their dinner bowl from the family leftovers or now from a tin. Even in a society where large, powerful dogs command respect as rather menacing status symbols, vicious

uncontrollable wild animals are not tolerated, and will not be invited indoors.

THE FIRST HOUSES

Today ‘house’ usually means something built of brick, stone or concrete – something quite substantial and long-lasting. There are still plenty of timber-framed

houses, and thatch is a perfectly acceptable roofing material; these are less obvious in the archaeological record, but where (and when) they occur, there are also signs of

stone dwellings, or at the very least, stone foundations. The most important point about a house is that it is permanent (that is, it is not a seasonal camp), and that it is part of a settlement.

By definition a settlement implies that the occupants are settled, no longer camping nomads; in prehistoric terms this means that they were no longer hunter-gatherers, but had become farmers.

This transition appears to occur very suddenly in the archaeological record, around 12,000–10,000 years ago (Henry 1989), and the Fertile Crescent, from Anatolia (present-day Turkey),

Mesopotamia (the land in and around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers), and the Levantine coast of the Mediterranean to Upper Egypt, is usually portrayed as the hub of this great leap forward –

the Neolithic Revolution.

Certainly this is the start of serious house building, and Jericho in Israel/Palestine, built in around 7500 BC, is usually cited as the first walled city, the stone remains of which are still

being excavated today. Agriculture brought high returns in terms of food production; excesses could be stored against famine or even short-term seasonal hardship. It was able to support a much

higher human population density, and although it gave rise to the disparity between rich landowner and poor serf labourer, or subsistence farmer, it also allowed for the appearance of commerce,

trade and wealth, which in turn allowed for the flowering of art, literature, philosophy and science. It gave us, in effect, civilisation.

Domestic pests, however, were no respecters of human niceties, no matter how civilised, and merely took advantage of human beings’ increased ability to create and own more things. The

highest in the land were not beyond depredation. When the great pharaohs were laid to rest in their giant sarcophagi in or under their giant pyramids, the food stores set aside for their journey

into the afterlife were tainted from the start with cockroaches, grain weevils and biscuit beetles, and their mummified bodies were polluted with carrion beetles (Pettrigrew 1834; Hope 1836).

Civilisation has brought mankind great advantages, but it has also brought with it plenty of hangers on.