On 1 January 1805 Napoleon wrote to George III using the address ‘Monsieur mon frère’, customary between monarchs, proposing a new peace settlement based on a division of spheres of interest. France was not interested in overseas empire, and if allowed a dominant role in Europe would not contest Britain’s dominion over the seas. The world was large enough for both nations, he argued. The offer was dismissed in a letter addressed to ‘the head of the French government’. An unintended consequence of Napoleon’s activities at Boulogne was to make the war popular in Britain for the first time since hostilities had begun over ten years before. The threat of invasion by ‘Boney’ struck a chord in all classes of the population, and the government now had the support of the country.1

Napoleon had also written to Francis I of Austria, to inform him that he had magnanimously ceded all his rights over Italy to his brother Joseph, who would ascend the Italian throne and renounce his claim to that of France, thereby ensuring that the two countries would never be united under one ruler. He expressed the hope that this sacrifice of his ‘personal greatness’ would be reciprocated by goodwill on the part of Francis, urging him to reverse the Austrian troop concentrations in Carniola and the Tyrol.2

The letter had hardly left Paris when Joseph declared that he would not, after all, renounce his right to the French throne. Napoleon then offered the crown of Italy to Louis, who also refused, equally jealous as he was of preserving his right to the imperial throne. Napoleon resolved to take the crown himself, and to appoint his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais as his viceroy. On 16 January a sick and depressed Melzi agreed to offer him the crown, and in a ceremony at the Tuileries on 17 March he was acclaimed by a number of Lombard nobles. On 31 March he left for Fontainebleau on the first leg of the journey to Milan for his coronation as King of Italy.3

Marshalled by the grand equerry Caulaincourt, carriages, horses and three sets of court officials and servants leapfrogged each other along the way, so that when the imperial couple reached a stop everything was ready for them, with a full complement of staff, while the second set raced ahead to prepare the next stage, and the third waited to clear things up once they had left. Napoleon himself now had a travelling berline, sometimes referred to as his dormeuse, as he could sleep in it, which maximised his capacity to work. The vehicle could be turned into a study, with a tabletop equipped with inkwells, paper and quills, drawers for storing papers and maps, shelves for books, and a lamp by which he could read at night. It could also be turned into a couchette, with a mattress on which he could stretch out, and a washbasin, mirrors and soap-holders so he could attend to his toilette and waste no time on arrival, and, naturally, a chamberpot. There was only room for one other person – Berthier on campaign, Méneval at other times.4

They left Fontainebleau on 2 April and stopped at Brienne the following day, staying the night at the château with the ageing Madame Loménie de Brienne and visiting the ruins of Napoleon’s old school and other former haunts. On 14 March, Easter Day, they made an imperial stop at Lyon, where they attended mass celebrated by Fesch in the cathedral. By 24 March they were in Turin, and on 1 May reached Alessandria, from where Napoleon rode over to contemplate the field of Marengo. Four days later he reviewed 30,000 troops under Lannes on the battlefield, in the coat and bullet-holed hat he had worn during the battle.

The next day he met his youngest brother. Jérôme had reached the shores of Europe at Lisbon, but the French consul there refused to allow his wife ashore, and while he travelled on to plead with his brother she sailed to London. In July she would give birth in Camberwell to a son, Jérôme Napoléon, who would never be recognised by the emperor. ‘There are no wrongs that genuine repentance will not efface,’ Napoleon told his brother when they met at Alessandria on 6 May. Elizabeth Patterson was granted a pension on condition she went back to America, and Jérôme was given command of a frigate, with the mission to sail to Algiers and retrieve French and Italian subjects imprisoned there.5

On 8 May 1805 Napoleon entered Milan. Although his entry was described by one French soldier as triumphal, with people weeping for joy in the streets, he was not satisfied. There followed nearly three weeks of receptions and festivities, culminating on 26 May, when he crowned himself with the iron crown of Lombardy once worn by Charlemagne, declaring, ‘God has given it to me, woe to him that reaches for it!’ The ceremony was greeted with enthusiasm by many who dreamed of a united Italy. It also made a lasting impression, with woeful consequences for much of South America, on a twenty-one-year-old Spanish creole who happened to be there, named Simón José Antonio Bolívar.6

The coronation could only be viewed in Vienna as a provocation. With the aid of British subsidies, Austria had been arming over the past year, and had concentrated considerable forces in the Tyrol. They would be difficult to contain if other states on the peninsula were to join Austria. Napoleon had written to Queen Maria-Carolina, the power behind the throne of Ferdinand IV of Naples, warning her not to allow herself to be drawn into a coalition against him; she was the sister of the late Marie-Antoinette, and hated the French. He rightly suspected that a plan already existed to land British and Russian troops in Naples.7

After the coronation he set off on a tour of the kingdom of Italy, inspecting fortifications and troops, meeting local authorities and nobles, going to the theatre and the opera, in a display of confidence and mastery. On 1 July he reached Genoa, which had been under French control for some time and was being administered, along with Liguria, Lucca and Piombino, by Saliceti, and now requested to be incorporated into the French Empire. The act was accompanied by elaborate celebrations, with Napoleon and Josephine towed out into the bay on a floating temple surrounded by gardens from which they watched a firework display. He went aboard the flotilla which Jérôme had commanded, greeting the 231 liberated slaves as they came ashore to universal applause.8

A week later Napoleon was back at Saint-Cloud. He was expecting a new Russian envoy, Count Nikolai Novosiltsev, through whom he hoped to negotiate a separate treaty with Russia, but Novosiltsev had stopped in Berlin and sent back his French passports, on the grounds that Napoleon’s encroachments in Italy had made negotiations pointless. The tsar had originally meant to avoid foreign entanglements and concentrate on reforming the Russian state. He secretly admired Napoleon, but had been shocked by the execution of Enghien – and mortified by Napoleon’s retort to his protest. Supported by his anti-French foreign minister Prince Czartoryski, he now put himself forward as a champion of ethical politics, with a far-reaching vision for the remodelling of the political arrangement of Europe.9

Napoleon affected to ignore the military preparations being made against him, and on 2 August he went to Boulogne. At the end of June he had given orders for the invasion force to be ready for embarkation by 20 July. He expressed frustration that his plan of drawing British ships off to the Indian Ocean and the Caribbean before sailing back to the Channel was proving difficult to implement. He was hoping to concentrate up to sixty-five ships of the line to protect the invasion craft. Impatient and accustomed as he was to overcoming any difficulty, he could not accept the delays imposed by the weather, blaming the admirals. They did indeed lack the dash he expected of them; hardly surprising, given the poor quality of the ships and the inexperience of the crews, which were no match for a Royal Navy in which Pitt had invested heavily during the late 1780s and early 1790s, and which had reached a peak of performance. The only French admiral with any initiative, Louis-René de Latouche Tréville, had died the previous summer. Napoleon urged Decrès to seek out younger men to command his fleets, but the real problem was, as he had already noted, lack of discipline among the crews, which could not be imposed in the British way, given his distaste for corporal punishment and the fact that, as he put it, ‘for a Frenchman it is a principle that a blow received must be returned’.10

He kept up the appearance of intending to go ahead with the invasion, even though eight months earlier, on 17 January 1805, he had told the Council of State that the concentration at Boulogne was a pretext to build up an army to strike against any of France’s enemies at a moment’s notice. On 3 August he instructed Talleyrand to warn Francis that he only meant to attack England, but might feel obliged to turn about and fight Austria if she supported Britain. Ten days later he instructed Talleyrand to send what amounted to an ultimatum to Francis, repeating that his invasion of England did not constitute a threat to Austria, but that if Francis persisted in rearming there would be war, and he would be spending Christmas in Vienna.11

Throughout August Napoleon kept up a stream of instructions for the invasion of England, and on 23 August he wrote to Talleyrand saying that if his fleet arrived in the Channel in the next few days he would be ‘master of England’. But on the same day he ordered supplies and rations to be stockpiled at Strasbourg and Mainz; two days later he sent Murat ahead along the Rhine to scout routes into southern Germany and gather maps of the area. ‘The decisive moment has arrived,’ he informed Berthier. A few weeks before, on 13 August, he had renamed the Army of England La Grande Armée. It was not only the name that had changed.12

The army Napoleon had inherited was a mixture of regulars from the royal army and untrained volunteers and conscripts. Each unit had coalesced in wartime conditions around its most competent officers, and each of the armies around their commanding general. Given the soldiers’ aptitude for desertion, it was impossible to impose discipline in traditional ways. Incompetent and disloyal officers had been purged and generals moved about, undercutting loyalties forged on campaign; demi-brigades had been re-formed as regiments; the men were paid, clothed and fed, and a sense of pride was instilled through parades. It nevertheless remained an unaccountable assemblage of men with idiosyncratic loyalties.

In May 1804 Napoleon had nominated fourteen marshals of the empire. While those singled out were all military men, this was in fact a civil rank, placing its bearer on a par with the ‘grands officiers’ of the empire and giving them a position at court, with the privilege of being addressed as ‘mon cousin’ by the emperor. The fourteen included close comrades such as Berthier and Murat, some awkward ones Napoleon needed to neutralise, such as Augereau and Bernadotte, as well as a number of capable generals whose loyalty he needed to capture. One such was Nicolas Soult, five months Napoleon’s senior, the son of a small-town notary who had distinguished himself fighting under Moreau and later Masséna, a braggart and an opportunist who needed to be controlled. Another was the cooper’s son from north-eastern France Michel Ney, seven months Napoleon’s senior, who had also risen through the ranks under Moreau, brave but limited, and therefore in need of cousinly guidance; Josephine had taken the first step in 1802 by arranging his marriage to one of her protégées. A very different man was Louis-Nicolas Davout, the scion of a Burgundian family that could trace descent from Crusaders, who, being almost a year younger than Napoleon, had just missed him at the École Militaire and had served as a cavalry officer in the royal army. He had been introduced to Napoleon in 1798 by Desaix, who valued him highly, and although he too had served under Moreau he was not a man for factions; self-assured and professional, a strict disciplinarian and unflinchingly brave, he was devoted to the service of France. But whatever their origins, attitudes and sympathies, on receiving their marshal’s baton such men became Napoleon’s lieutenants, bound to him by far more than mere bonds of loyalty. They would allow him to operate in larger numbers on a wider theatre, and they would hold his army together.

The concentration of the greater part of the army at Boulogne for over a year transformed it. The idea of taking the war to the hated English aroused enthusiasm, and the rate of desertion dropped off. The cohabitation and frequent contact, both in drilling and exercises (although there was surprisingly little of either) and in off-duty activities, developed a wider esprit de corps and, in the words of one soldier, ‘established relationships of trust between the regiments’. It had forged an army for Napoleon.13

By 3 September he was back at Malmaison. A couple of days later he learned that Austria had invaded Bavaria, an ally of France. Over the next three weeks he attended to matters that needed to be despatched before he went on campaign, including an edict abolishing the revolutionary calendar and reinstating the Gregorian. On 24 September, having instructed the Senate to put in hand the raising of 80,000 more men, and leaving Joseph and Cambacérès in charge, he left for Strasbourg to join the Grande Armée, which had been on the march since the end of August.

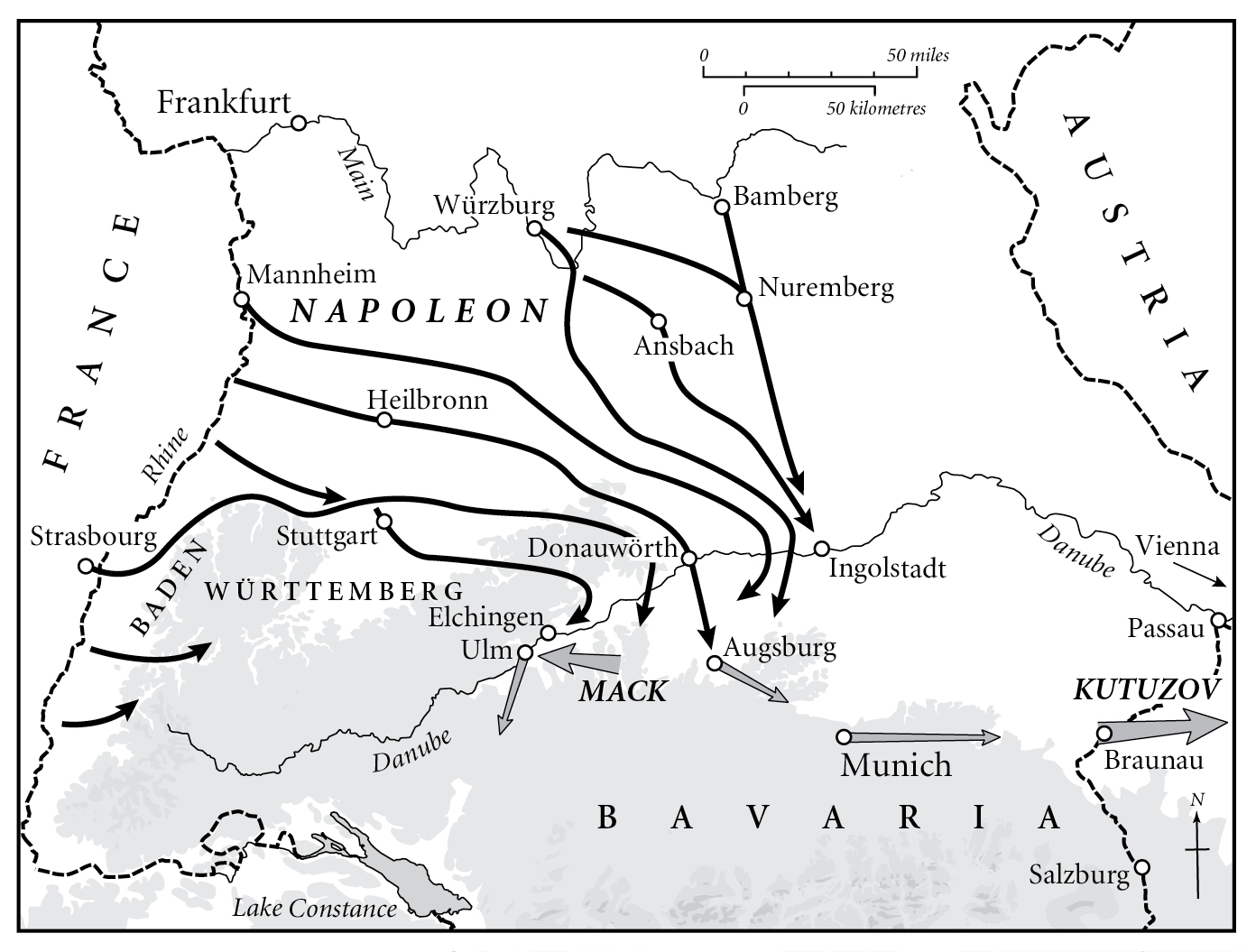

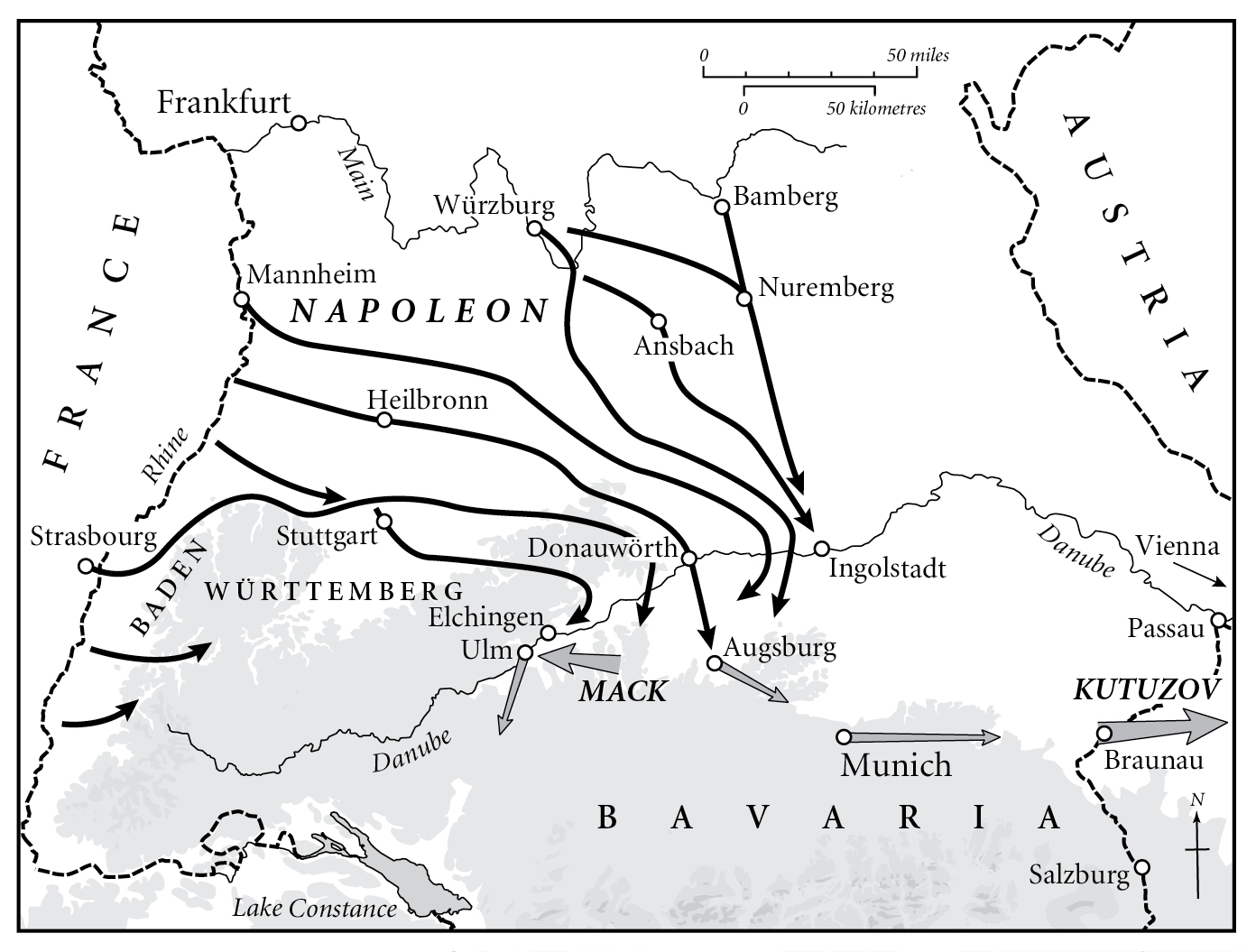

While the 90,000 Austrians in Carniola and the Tyrol under Archdukes Charles and John moved into Italy, on 8 September General Karl Mack with a corps of 50,000 Austrians under the titular command of Archduke Ferdinand had marched into Bavaria and taken up position in the west of the country to await a Russian army under General Kutuzov which was to join him in invading France. The Grande Armée had left the Channel coast in seven corps, commanded by Bernadotte, Marmont, Davout, Soult, Lannes, Ney and Augereau, with a cavalry force of 22,000 under Murat, a total of some 180,000 men. They moved with astonishing speed, living off the land, allowing men to fall behind and catch up as best they could.

Napoleon left Strasbourg on 2 October in fine weather, cheered as he passed troops on the march, some of whom would present him with petitions. He would stop his horse or carriage alongside resting units and address the men; thanks to his extraordinary memory he could always name one or other of them and allude to their or their unit’s battle records. On 4 October he was at Stuttgart with the elector of Württemberg, with whom he attended a performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and from whom he had to borrow fresh horses as his were all spent. Three days later he was directing the crossing of the Danube at Donauwörth, far to the east of Mack’s positions, which enabled him to sweep round and attack him from behind. From Augsburg on 12 October he wrote to Josephine that things had gone so well that the campaign would be one of his shortest and most brilliant yet: ‘I am feeling well, although the weather is dreadful and it’s raining so much I have to change clothes twice a day.’ He was always in the thick of the action, and when Murat and Berthier took his horse’s reins to pull him away from an exposed position in which bullets were whistling around their heads, saying it was not the place for him, he snapped at them, ‘My place is everywhere, leave me alone. Murat, go and do your duty.’14

‘For the past eight days, rain all day and cold wet feet have taken their toll, but today I have been able to stay in and rest,’ he wrote to Josephine from the abbey of Elchingen on 19 October, adding, ‘I have carried out my plan: I have destroyed the Austrian army just by marching.’ Archduke Ferdinand had managed to get away with a small force, but Mack had been checked by Ney at Elchingen and was left with no option other than to seek refuge in the town of Ulm, where he was bottled up with some 30,000 men while his cavalry fled back to join the Russians in Bohemia. On 19 October Mack had been obliged to capitulate, bringing the number of Austrian prisoners taken by the French in the space of two weeks to 50,000.15

It was an extraordinary feat. Sébastien Comeau de Charry, a fellow artillery officer who had emigrated and ended up serving in the Bavarian army, now allied to the French, could barely believe what he witnessed. He had watched what looked like a rabble pour into Germany, shedding men and horses but streaming on, suddenly turn into a fighting force. On the Austrian side there were beautiful uniforms and fine horses, on the French ‘not one unit in order, just a compact mass of foot-soldiers’ pouring down the road. ‘It is only a superior man, a sovereign, who can bring unity and harmony to such a crowd,’ he reflected. A young French officer in Ney’s corps thought he had dreamed it all when he reflected that he had been at Boulogne on 1 September and was taking Mack’s surrender in Bavaria on 20 October.16

Comeau de Charry had last met Napoleon at a mess table in Auxonne in 1791, when he had refused to sit next to him on account of his republican views, and was now astonished to see him adopt ‘the tone and manner of an old, loved, esteemed comrade’. Attached to his staff, he was able to observe not only the emperor’s extraordinary grasp of the situation, but also the unorthodox behaviour of the French army. Where another general would have wished and another army demanded a few days’ rest and resupply after a victory such as Ulm, Napoleon pressed on along the Danube towards Vienna and his troops surged on, stopping in groups to cook up something to eat, then resuming their march, dropping behind their units, getting mixed up with others, going off on ‘la maraude’ in search of food and other necessities, but always ready at a moment’s notice to form up columns, lines or squares, without having to be directed by their officers. Colonel Pouget, commanding the 26th Light Infantry, noted that on the march soldiers of various units would get together in groups to scavenge, mess and find comfortable overnight quarters, only rejoining their respective units in camp, but in an emergency they would integrate with the closest unit and fight as though they belonged to it.17

On 24 October Napoleon entered Munich, and invited the elector of Bavaria to repossess his capital. On 13 November, after Murat, Lannes and Bertrand had managed to fool the unfortunate Austrian colonel guarding it to let them cross a bridge over the Danube, assuring him that an armistice had been signed, Napoleon entered Vienna. He took up quarters outside the city in the imperial palace of Schönbrunn. He was in an evil mood, to judge by a letter to Joseph written the next day in which he raged against Bernadotte, who had failed to act on his orders and missed a valuable opportunity. He was also displeased with Augereau, who had been slow, and with Masséna, who had failed to pin down the Austrians in Italy. His mood would not have improved three days later, when he received news that instead of sailing into the Mediterranean and harrying British ships supporting Naples, Admiral Villeneuve had left Cádiz with the combined French and Spanish fleets only to be disastrously defeated off Cape Trafalgar by Admiral Nelson. He took his displeasure out on Murat, who had allowed a Russian unit to give him the slip.18

After Ulm, Napoleon had suggested peace negotiations to Francis, pointing out that Austria was bearing the brunt of the war and suffering on behalf of her British and Russian allies. Although he had lost an army, Francis remained sanguine, as Napoleon’s position was precarious. In Italy, Masséna and Eugène had defeated the archdukes, but they could not pursue them as they had to turn about and face a Neapolitan attack supported by British and Russian troops. Forced out of Italy, the archdukes were now hovering on Napoleon’s southern flank. Having been obliged to detach a force to head them off and leave men behind to cover his lines of communication, he was himself down to little over 70,000 men. A combined Russian and Austrian force of nearly 90,000 had gathered at Olmütz (Olomuc) to the north of Vienna, and there was a risk that Prussia might join the coalition and attack him from behind.19

King Frederick William had been wavering between the option of joining France and acquiring Hanover as a reward, and that of joining the anti-French coalition. News of Trafalgar lifted the spirits of every enemy of France, and increased Napoleon’s vulnerability. Tsar Alexander had visited Berlin on 25 October and, aided by the fiercely anti-French Queen Luise, managed to persuade the king to sign an accord promising to take the field against the French by 15 December at the latest. The pact was sealed by a night-time visit by the tsar and the royal couple to the tomb of Frederick the Great, where by the light of flaming torches they vowed to fight together and Alexander kissed the sarcophagus of the renowned warrior.

Napoleon’s anxieties were compounded by the situation at home, where the fall-off in trade following the end of the peace of Amiens, a bad harvest and a budget deficit caused by military expenditure had precipitated a financial crisis and a run on the Bank of France, which Joseph was barely managing to contain. The first successes of the campaign, reported in fulsome Bulletins which were plastered on street corners and read out in theatres, had elicited enthusiasm and created a sense of national solidarity. But by the end of October there were scuffles outside the bank as people struggled to withdraw specie. By the beginning of November troops were being deployed to keep order outside the bank. Joseph and Cambacérès sent Napoleon daily pleas for good news to feed to the jumpy population. ‘It is highly desirable that Your Majesty should send me news every day,’ Joseph wrote on 7 November. ‘You cannot imagine how easily anxiety rises when the Moniteur does not give any news of Your Majesty and the grande-armée; in the absence of real news, anxiety forges false news.’ Although the official reports played down its significance (Napoleon would dismiss it with talk of gales dispersing and wrecking some of the fleet), news of Trafalgar further undermined confidence. By 9 November, Joseph warned that ‘we must either support the Bank or let it fail immediately’. Napoleon tried to ease the tension by sending back more mendacious Bulletins, but as he and his army marched further and further away, anxiety mounted, and by late November there was mild panic in Paris.20

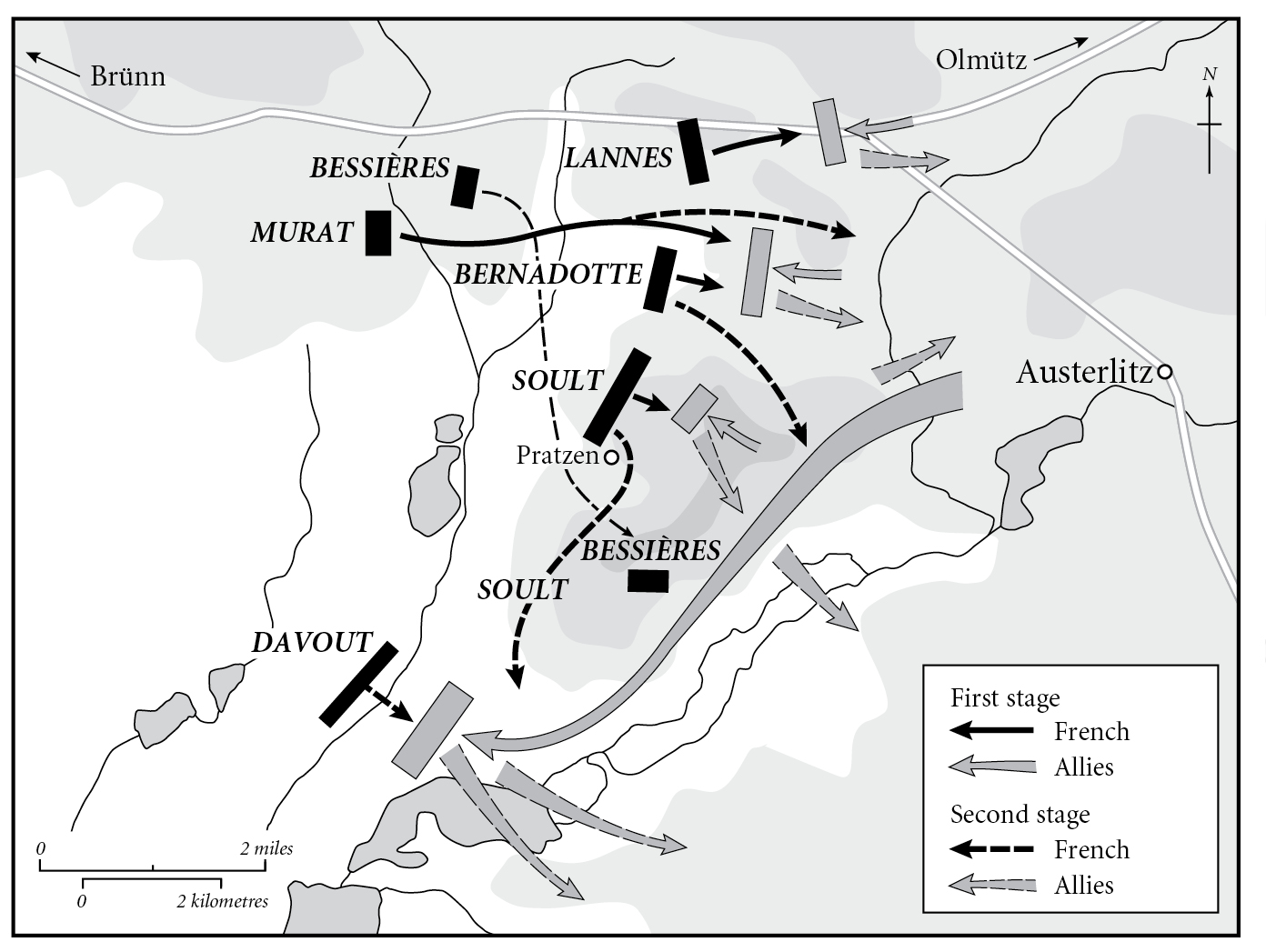

Napoleon needed a quick victory. He marched north to confront the Austro-Russian concentration at Olmütz, reaching Brünn (Brno) on 20 November. He rode out with his staff and spent a long time surveying the vicinity, noting various features of the terrain. ‘Gentlemen, look carefully at this ground!’ he said to his entourage. ‘It will be a field of battle! You will all have a part to play on it!’21

He was eager to bring on events, fearing the entry of Prussia into the war. Having ridden out and scouted the ground again, he began acting as though he wished to avoid an engagement. He withdrew units which had approached the enemy positions and instructed others to retreat if attacked, gradually drawing the enemy onto his chosen ground. On 26 November he sent a letter to the tsar through General Savary. Savary was snubbed at Russian headquarters by sneering aristocratic young aides, and although the tsar was more polite, his reply was addressed to ‘the head of the French government’. Napoleon sent Savary back with a request for a meeting, to which Alexander responded by sending one of his aides, Prince Dolgoruky. Along with others in the tsar’s entourage, the young man took these overtures as a sign of weakness, and when they met, out in the open, he looked down on Napoleon, whom he thought small and dirty, and declared that he must evacuate the whole of Italy and all Habsburg dominions, including Belgium, before any talks could take place. A livid Napoleon told him to leave. The exchange confirmed that Russian headquarters was dominated by inexperienced hotheads eager to prove themselves in battle, like the tsar himself, who would prevail over wiser counsels.22

Two Austrian delegates arrived at Napoleon’s headquarters requesting an armistice, and two days later, on 27 November, the Prussian foreign minister Count Christian von Haugwitz also turned up. Napoleon recognised these moves for the delaying tactics they were, and rudely sent them off to Vienna to confer with Talleyrand, to whom he wrote on 30 November saying he would be prepared to make far-reaching concessions to make peace with Austria. But he spent that day preparing for battle.23

Impervious to the alternating rain and hail, he again carefully surveyed the terrain and observed the Austro-Russian army’s movements. He seemed preoccupied, but rubbed his hands together with satisfaction. That night he slept in his carriage. After a final reconnaissance on 1 December, he settled into a small round hut which his grenadiers had built for him near a cottage in which his staff put up. He was joined by Junot, who had travelled from his embassy in Portugal to be at Napoleon’s side and was overjoyed to have arrived in time for the battle. That night, after lecturing his staff over dinner on the subject of the deficiencies of modern drama when compared with the works of Corneille, Napoleon rode out for a last look at the enemy positions. He then walked among the campfires around which the troops huddled against the bitter cold. The supply train had, as usual, failed to keep up with the army, and they had little food. They had been read a proclamation in which he assured them that he would be directing the battle throughout, and would, if needed, be among them to face the danger. Victory on the morrow would mean a speedy return home and a peace worthy of them and him. As he walked through the bivouac, some soldiers lit his way with torches, and were soon joined by others with twists of straw or flaming branches, so that soon a torchlight procession snaked through the camp, to shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ ‘It was magnificent, magical,’ recalled one chasseur of what was now the Imperial Guard. The following morning seemed no less so.24

It happened to be the anniversary of Napoleon’s coronation. The troops were roused long before daybreak, and formed up in the thick mist of a wintry morning which muffled all sound. They stood to for some time in eerie silence. The sun rose, burning off the mist and temporarily blinding them before its rays glinted on the rows of bayonets and lance-tips facing them, giving the signal for the artillery to open up. The ‘soleil d’Austerlitz’ would go down in legend.25

Napoleon’s 73,000 men were outnumbered by the combined Russian and Austrian force of 86,000 facing them, and seriously outgunned with 139 pieces of artillery to their opponents’ 270. But having surveyed the ground and taken up what appeared to be defensive positions, he had anticipated the direction in which they would be tempted to attack, and laid his plans accordingly. He instructed Davout on his right wing to fall back when the Russian left challenged him and to draw them on, off the high ground, in order to make their eventual retreat more difficult. The Russians responded as expected, and when they had overextended themselves, Napoleon launched a vigorous attack on the now exposed enemy’s centre, while his left wing outflanked their right and forced it back, widening the gap at the centre. The manoeuvre worked as he had intended, and the enemy were thrown into confusion, with some units having to face about and others to fall back into the path of their advancing colleagues. But the Russians in particular fought doggedly, and there was a moment when a counter-attack by the Russian Guard threatened the outcome. It was countered by a vigorous cavalry charge led by Bessières and Rapp. The allied army crumpled, and while individual units stood their ground the majority took flight, with a humiliated Alexander galloping away from the field of battle.26

‘The battle of Austerlitz is the finest of all those I have fought,’ Napoleon wrote to Josephine on 5 December; ‘more than twenty thousand dead, a horrible sight!’ As usual, he exaggerated the enemy losses and diminished his own, but it had been a triumph. The French army had taken forty-five enemy standards, 186 guns and 19,600 prisoners, and although the number of dead was considerably smaller than 20,000, the allied army had been diminished by at least one-third and its morale shattered. ‘I had already seen some battles lost,’ wrote the French émigré Louis Langeron, a general in Russian service, ‘but I could never have imagined a defeat on this scale.’27

The victorious troops lay down and slept around miserable smoking fires among the dead and dying, with nothing to eat except the odd crust they carried with them. Flurries of snow had made everything damp, and in the evening it began to rain. It was not until the following night that Napoleon himself slept in a bed for the first time in over a week, in a country house in the nearby village of Austerlitz, after which he named the victory. In his address to the troops he stressed that it had been entirely their work, and announced that he would adopt the children of all the French dead.28

He only slept for a couple of hours. The Austrians had requested a ceasefire, and the following day he met the emperor, in the open at a prearranged place. Francis drove up in a carriage, from which Napoleon handed him down, and they spoke for over an hour as their aides watched. Francis conceded that the British were merchants in human flesh, and abandoned the coalition. Napoleon agreed to an armistice, on condition he expelled the Russians from his dominions. It was signed on 6 December.29

Napoleon admitted to his secretary Méneval that he had made a mistake in agreeing to the meeting with Francis. ‘It is not in the aftermath of a battle that one should have a conference,’ he said. ‘Today I should only be a soldier, and as such I should pursue victory, not listen to words of peace.’ He was right. Davout, who had been in pursuit of the retreating Russians, had cornered them and was on the point of taking Alexander himself prisoner when he was informed by a note from the tsar that an armistice had been signed which included the Russians – which it did not. Davout retired and let them pass. On 5 December Napoleon had written to the elector of Württemberg, who was Alexander’s brother-in-law, to use his good offices to persuade the tsar to lay down his arms and negotiate. But Alexander felt, according to one contemporary, ‘even more thoroughly defeated than his army’, and longed only for a chance to redeem his honour; he would fight on.30

On 12 December Napoleon was back at Schönbrunn. Three days later, on the very day by which it was supposed to have joined the anti-French coalition, he signed a treaty of alliance with Prussia, sanctioning its annexation of the British king’s fief of Hanover and thereby stealing one of Britain’s potential allies on the Continent.

Talleyrand had been trying to persuade Napoleon to be generous to Austria and turn her into his principal European ally, which would give France tranquillity in Italy and the Mediterranean, a bulwark against Russia as well as a counterbalance to Prussian influence in Germany. But while Napoleon agreed with him that the only alternative, an alliance with Russia, was a poor prospect, qualifying the Russians as ‘Asiatics’, he had lost respect for Austria. He took no precautions as he moved about Vienna and its environs, and his soldiers noted that while the population was reserved, they treated them as tourists rather than enemies. On 17 December Napoleon had treated an assembly of Austrian generals and representatives of the estates to a two-hour admonition containing, according to the prince de Ligne, ‘a little greatness, a little nobility, a little sublimity, a little mediocrity, a little triviality, a little Charlemagne, a little Mahomet and a little Cagliostro …’ Napoleon did not consider them worthy allies.31

True to his threat, he spent Christmas in Vienna. By the Treaty of Pressburg, dated 27 December, Austria ceded the Tyrol and Vorarlberg to Bavaria, other territories in Germany to Napoleon’s allies Württemberg and Baden, and Venetia, Dalmatia, Friuli and Istria, gained by the Treaty of Campo Formio, to France. As well as losing Francis a sixth of his twenty-four million subjects, it destroyed what was left of the Holy Roman Empire. By the same treaty, Francis recognised Napoleon as King of Italy, the rulers of Bavaria and Württemberg were elevated to royal status, while that of Baden became a grand duke. Finally, Austria had to pay a huge indemnity to France to cover the cost of the campaign.

Napoleon could not afford to waste time in Vienna, as he had a country to rule, and he left the next day. On 31 December he was in Munich, where on 6 January he enjoyed a performance of Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito with the newly-minted King of Bavaria, who was only too happy to give away his daughter Augusta in marriage to Eugène a week later. Josephine, who had come from Paris for the occasion, was ‘at the height of happiness’ according to Caulaincourt. The next stop was Stuttgart, where the new King of Württemberg, a man of legendary girth, laid on entertainments which included operas and a hunt. Wherever he went in southern Germany Napoleon was greeted with genuine enthusiasm. But he could not linger.32

From the frantic letters of Joseph and Cambacérès it was clear that the French financial crisis had not subsided. News of Austerlitz eased the tension, but Cambacérès urged Napoleon to return as soon as possible, as there was ‘a torrent of bankruptcies’ undermining confidence in the government. People had come to identify stability and order so much with the person of Napoleon that his absence was in itself cause for anxiety. He was back at the Tuileries at ten o’clock on the evening of 26 January. Before retiring for the night he summoned the Council of State and a number of ministers to meet in the morning.33