On the day following his return to Paris, 15 August 1808, Napoleon held the customary audience for the diplomatic corps to receive their good wishes on his birthday. In the absence of a papal nuncio, the diplomats were headed by the handsome and urbane Austrian ambassador Count Metternich, who, in the interests of intelligence-gathering, was having an affair with Napoleon’s sister Caroline, the new queen of Naples, having already consulted several other ladies in the same manner. Napoleon took him to task for over an hour on a quite different matter – that of recent Austrian armaments which had come to his notice. The Emperor Francis was also dragging his feet in recognising Joseph as King of Spain.1

The harsh terms imposed after Austerlitz had left Austria smarting, while anti-French feeling had been growing throughout Germany, stimulated by a wave of nationalist literature and a folkloric revival, as well as French exactions and the arrogance of French officials; even within the Confederation of the Rhine Napoleon’s high-handed treatment of his allies generated resentment. News of Bailén gave heart to all those who longed for revenge, and many felt it was time to rebel against French domination. Austria had been rearming in anticipation of war with France, assuming the rest of Germany would rise up and join it.2

In the circumstances, Napoleon could not afford to denude Germany and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw of troops in order to send them to Spain unless he could cover his back, and the only way of doing that was to call on his ally Russia. Yet her reliability was open to question; his ambassador in St Petersburg, Caulaincourt, warned him that the Tilsit settlement was unpopular in Russia, being associated in the public mind with the defeats of Austerlitz, Eylau and Friedland, and the blockade was having a damaging effect on the economy.

Napoleon’s inability to see things from another’s perspective helped him ignore this and other warnings, as did his tendency to believe he could obtain results by dint of trying. When Alexander’s ambassador was due in Paris after Tilsit, Napoleon bought Murat’s sumptuous residence – pictures, furniture, silver, china, bedding and all – to provide him with a comfortable embassy, and went out of his way to honour him. But the ambassador, Count Tolstoy, remained aloof and barely concealed his dislike of Napoleon. In an attempt to revive Alexander’s enthusiasm for the alliance, Napoleon had earlier that year returned to the subject of a joint expedition against the British in India, with the accompanying promise of an extension of the Russian empire in the east. Caulaincourt and the Russian foreign minister, Count Nikolai Rumiantsev, duly pored over maps, and General Gardanne calculated marching distances through Aleppo, Baghdad, Herat, Kabul and Peshawar. But while Napoleon never ceased dreaming of India, he had no intention of embarking on the venture, as Alexander probably realised.3

Before parting at Tilsit, they had agreed to meet again the following year, and this encounter was to take place at Erfurt in Westphalia at the end of September 1808. Napoleon hoped that by deploying his usual mixture of charm and implied threat he would be able to reassert his ascendancy over the tsar. The meeting would also provide the opportunity to propose a dynastic marriage; such a union would kill two birds with one stone, as it would cement the alliance and at the same time provide Napoleon with an heir, which had become a pressing issue once again. The question had resurfaced when, on 5 May 1807, his nephew and adopted son Napoléon-Charles, the child of Louis and Hortense, died of croup. Now that he knew he could sire a child himself, many in his entourage, including Fouché and Talleyrand, urged him to divorce Josephine and marry a woman of childbearing age.4

One day in November 1807, with the court at Fontainebleau, Fouché had called on Josephine in her apartment and suggested she go before the Senate and request a divorce in the interests of the empire. He even produced a prepared text of the speech she should make. She asked him whether he had been sent by Napoleon, which he denied, so she dismissed him, saying she would do only what her husband asked of her. When she informed him of Fouché’s visit Napoleon made a show of rebuking his minister, though it seems unlikely Fouché would have acted without his knowledge. He also reprimanded him when he read a police report which mentioned that people were discussing the divorce as though it had been agreed. To Josephine it seemed as though it had. ‘What sadness thrones bring!’ she wrote to her son, foreseeing the inevitable.5

Alexander had two unmarried sisters, and Napoleon did not see any reason why he should not embrace the idea if he could put it to him directly. ‘An hour together will suffice, while the negotiations would last several months if it were left to the diplomats,’ he said to Cambacérès as he left Paris. He had ordered Erfurt to be cleaned up, its buildings repainted and its streets lit, and he had sent out tapestries, pictures and china to adorn his apartments there. He had also arranged for the best actors and the prettiest actresses of Paris to be sent out to entertain the company in the evenings, and, if possible, to find their way into Alexander’s bed.6

To impress Alexander and lend weight to their meeting, he had also invited all the rulers of the Confederation of the Rhine and the King of Saxony. He had carefully selected the plays to be performed. According to Talleyrand, by staging heroic scenes he meant to disorient the ancient royals and aristocrats present and ‘transport them in their imagination into other realms, where they would see men who were great by their deeds, exceptional by their actions, creating their own dynasty and drawing their origin from the gods’. The themes of immortality, glory, valour and predestination which recur in the plays he chose were meant to inspire admiration in all who approached him, and Corneille’s Cinna delivered the punchline in the phrase ‘He who succeeds cannot be wrong.’ Voltaire’s Mahomet treats of the need for a new faith and a new master of the world; its protagonist owes everything to his own qualities, and nothing to ancestry. Napoleon did not bring Josephine or a numerous suite, but as Talleyrand had been at Tilsit and was a good courtier who knew everyone in Europe, he brought him along. This turned out to be a mistake.7

When Alexander announced his intention of going to Erfurt, most of his entourage expressed fears that he would allow himself to be cajoled by Napoleon into further engagements unfavourable to Russia, and even, given recent events at Bayonne, that he might never come back. In reply to his mother, who had written begging him not to go, he explained that despite the setbacks at Bailén and Vimeiro, Napoleon was still strong enough to defeat any power that defied him. Russia must build up her military potential while pretending to remain his ally. He must go to Erfurt to persuade Napoleon of his goodwill, and his presence there should send a signal to Austria not to try anything rash before time. To his sister Catherine, who had also implored him to have nothing to do with the Corsican ogre, he replied more succinctly: ‘Napoleon thinks that I’m just a fool, but he who laughs last laughs longest.’8

As soon as he heard that Alexander had set out, Napoleon left Paris, arriving at Erfurt on the morning of 27 September, and after dealing with some administrative business he called on the King of Saxony, who had preceded him. At two o’clock, having been alerted to Alexander’s approach, he rode out to meet him outside the town. On seeing him ride up, Alexander alighted from his carriage and the two emperors embraced, after which they mounted up and rode into the town, greeted with full military honours, and spent the rest of the day together, only parting at ten that night.

Napoleon hoped to recreate what he called ‘the spirit of Tilsit’, having his troops parade before Alexander and spending hours in conversation with him on every subject that could flatter his vanity, while displaying his power over the other assembled sovereigns by ordering them about and telling them where to sit at table – ‘King of Bavaria, keep quiet!’ he snapped at one point.9

As Alexander was hard of hearing in one ear, Napoleon had a dais built for the two of them close by the stage at the theatre. This meant that, as Talleyrand remarked, ‘People listened to the actors, but it was him they were looking at.’ During one performance, at the lines ‘To the name of conqueror and triumphant victor, He wishes to join that of pacifier,’ Napoleon made a show of emotion noticed by all. When, during a performance of Voltaire’s tragedy Oedipe, the actor spoke the line ‘The friendship of a great man is a gift from the gods,’ Alexander stood up and took Napoleon’s hand in a gesture meant for the audience.10

Napoleon acted the charming host one moment, running down the stairs to greet Alexander as he arrived for dinner, and putting him in his place the next. He arranged an excursion to the nearby battlefield of Jena, where, as one military man to another, he explained the battle to him, no doubt meaning to remind him of his own military prowess. He invited Alexander to a parade in the course of which he decorated soldiers with the Legion of Honour; since each man called forward had to give an account of his heroic exploit, and these had all taken place at Friedland against the Russians, the tsar was openly humiliated by having to listen to stories of his troops being beaten. Napoleon had even in the course of a discussion resorted to staging one of his rages, throwing his hat on the floor and stamping on it.11

On 6 October there was a hunting party in the forest of Ettersberg, for which stags were driven into a funnel of canvas screens so that by the time they reached the hunters they were disoriented, and so close that even the inexperienced Alexander with his poor eyesight managed to bag one trotting past eight feet from him. The hunt was followed by a dinner, a short concert, a play and a ball. Napoleon did not dance because, as he put it in a letter to Josephine, ‘forty years are forty years’. Instead, he had a two-hour discussion about German literature with the poet Wieland, whom he had invited for the purpose, showing off his knowledge to the surprised and flattered German literary men listening to him. He then walked over to Goethe and had a long conversation with him. One can but admire his stamina, given that all the while he was manipulating the various rulers of the Confederation of the Rhine, each of whom had to be cajoled and bullied by turns, running the government of France, and overseeing operations in Spain, not to mention fighting a severe cold. Goethe, with whom he had a long meeting over breakfast on 1 October, was overwhelmed by the power he sensed in Napoleon’s gaze, and fascinated by his seemingly superhuman qualities.12

One day, when Alexander had forgotten his sword, Napoleon handed him his own, at which Alexander declared, ‘I accept it as a mark of your friendship, and Your Majesty may be quite sure that I shall never draw it against you.’ He did not, as Napoleon had hoped, promise to draw it against Austria if she were to attack while he was occupied in Spain. Alexander adopted an attitude of stubborn neutrality, refusing nothing and promising nothing. Napoleon’s position was identical, since he wanted to oblige Alexander to bind himself further while offering nothing in exchange, except for a vague promise to withdraw French troops from the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Prussia and, in return for the tsar’s acceptance of his doings in Spain, to allow his annexation of Finland. The lack of any mutual interest in their alliance was glaring. Yet it was crucial to Napoleon, not only to keep Austria in check, but also to maintain the blockade against Britain, which was beginning to take effect.13

It was impossible to exclude British goods from the Continent entirely. Even while paying lip service, Russia had been contravening the terms of the blockade by allowing some neutral ships into its ports. British merchants had established entrepots at Heligoland, from where small ships could dart into creeks or minor harbours all over northern Europe, and at Malta, to do the same in the Mediterranean. British ships also defied the blockade by putting into the Austrian port of Trieste, from where their merchandise could reach Central Europe. There was plenty of clandestine trade, and there were even cases of French merchants from Bordeaux supplying the British forces in Portugal with wine and brandy. In Hamburg, the city authorities were surprised at a curious rise in the number of funerals, only to discover that coffins were being used to transport smuggled coffee and indigo – from which Bourrienne, now a commissioner there, was taking a cut. Even Napoleon’s family flouted the blockade, Louis in Holland almost blatantly, Jérôme in Westphalia passing on goods, and Josephine buying smuggled silks and brocades. Cambacérès actually ordered the chief administrator of the Grand Duchy of Berg, Jacques-Claude Beugnot, to send him cured hams by clandestine means in order to avoid paying customs duties aimed to back up the blockade. On the march back from Germany following Tilsit, Captain Boulart of the Guard Artillery and his fellow officers and men happily bought quantities of English merchandise in Frankfurt and Hanover which they smuggled into France in their ammunition wagons, which they would not allow the customs officials at Mainz to inspect, arguing that the falling snow would soak the powder.14

Nevertheless, by the first months of 1808 the blockade was having a crippling effect on the British economy, and, crucially, threatened to impinge on the political situation. Imports of much-needed cereals had plummeted by a staggering 93 per cent, and Napoleon calculated that if the pressure could be kept up, the country would not be able to feed itself and there would be bread riots which would force the government to its knees. He was therefore desperate to keep Russia within the system, and with Alexander visibly cooling the surest means of doing that seemed a dynastic alliance. The subject was broached, and the tsar gave all the appropriate signs of delight, but declared he had to obtain the assent of his mother before he could give a definite answer. He had no intention of going along with the idea, as he had already resolved to undermine Napoleon.15

On the day after his arrival at Erfurt, Talleyrand had found a note from Princess Thurn und Taxis, a sister of the queen of Prussia, inviting him to take tea with her. There he met Alexander, who had set up the meeting. The two met there several times over the next few days, having quickly entered into an understanding – Talleyrand told Alexander that he was the only civilised ruler capable of saving Europe and France from Napoleon, and declared himself ready to serve him in this cause. Whether it was mentioned then or not, the service would not come free of charge.16

On his return to Paris, Talleyrand would remain in touch through the secretary of the Russian embassy, Karl von Nesselrode. He was already in secret contact with the Austrian ambassador Metternich, who summed up Talleyrand’s position thus: ‘The interest of France herself demands that the powers capable of standing up to Napoleon must unite to oppose a dyke to his insatiable ambition, that the cause of Napoleon is no longer that of France, that Europe itself can only be saved through the closest possible alliance of Austria and Russia.’17

‘I am very satisfied with Alexander, and he must be with me,’ Napoleon wrote to Josephine on 11 October, convinced that he had seduced the tsar. The following day they signed an agreement reaffirming their alliance, as well as a joint letter to George III professing their wish to make peace and appealing to him to enter into negotiations. Three days later, they rode out of Erfurt together to the spot on which they had met two weeks before, embraced and took their leave of each other. Napoleon then rode back, slowly, into town, apparently deep in thought. He had plenty to reflect on.18

He had come to Erfurt to consolidate the alliance forged at Tilsit, only to see cracks developing in it. He had held court, surrounded by cringing monarchs, but, as he once confessed to his interior minister Chaptal, he felt they all despised him for his low birth and would gladly topple him from his throne. ‘I can only maintain myself on it by force; I can only accustom them to see me as their equal by keeping them under my yoke; my empire is destroyed if I cease to be feared.’ He was aware that the higher he rose the greater his vulnerability. It is tempting to think that the reason he was drawn to Alexander, the most unlikely and inconvenient ally for him, was that he sensed the tsar’s insecurities and did not feel such a parvenu in his company. However much he may have boasted about them, Napoleon lacked faith in the value of his own achievements. ‘Military glory, which lives so long in history, is that which is most quickly forgotten among contemporaries,’ he admitted to one of Josephine’s ladies. He also feared that his state-building and other achievements would not survive. Josephine remonstrated with him, maintaining that his genius gave him his title to greatness, to no avail. He was, according to Rapp, lamentably obsessed with what the aristocratic milieu of the Faubourg Saint-Germain thought of him, and ridiculously susceptible to gossip. It is ironic that while, as Talleyrand had noted, he used the theatre to drive home the message to the mostly idle and ineffectual sovereigns that he stood above them as the man of action, he lacked confidence in his own achievements and felt the need to adorn them with the trappings of royalty. ‘Simplicity does not suit a parvenu soldier such as myself as it does a hereditary sovereign,’ he said to one Polish lady.19

To Chaptal, he complained that it was only ancient dynasties that could count on unconditional popular support, and while a hereditary monarch could lie around being dissolute, he could not afford to, as ‘there is not one general who does not believe he has the same right to the throne as me’, which was patently not true. Mollien was struck by ‘his insatiable need to be the centre of everything’, which he believed to be dictated by ‘the fear lest any particle of power escape him’. He also noticed in Napoleon an obsessive need ‘to represent himself as the only essential man, to establish in the public perception an exclusive superiority, to belittle anything that might threaten to share it’, and he was convinced this was the result not of calculation, but of a kind of instinctive reaction – which suggests deep psychological insecurities. ‘Don’t you see,’ Napoleon used to say to members of his family, ‘that I was not born on the throne, that I have to maintain myself on it in the same way I ascended to it, with glory, that it has to keep growing, that an individual who becomes a sovereign, like me, cannot stop, that he has to keep climbing, and that he is lost if he remains still.’ He could certainly not afford to remain still now.20

The day following his arrival at Erfurt, he had received a special envoy from the Emperor Francis, General de Vincent. Although the audience had been courteous, with declarations of goodwill on both sides, it was obvious from Vincent’s tone and the Austrian armaments that Vienna was preparing for war. Napoleon could not conceive that Francis would be foolish enough to make war on his own, and this led him to suspect the existence of a secret agreement between him and Alexander.21

This made it all the more imperative to pacify Spain as quickly as possible. He was back at Saint-Cloud at eleven o’clock on the night of 18 October. On 22 October he visited the Salon (the painters who wished to submit had been given to understand that it would be desirable to show Napoleon visiting the battlefield of Eylau and casting a ‘consoling eye’ over it which would ‘soften the horror of death’; the winner, Antoine Gros, evidently achieved this, having managed to ‘give Napoleon an aura of kindness and majestic splendour’). In the course of the next few days he opened the session of the Legislative, held receptions, inspected public works, orphanages and hospices before leaving on 29 October. Travelling day and night, stopping only to dine briefly and meet officials along the way, sometimes taking to his horse, by 3 November he was at Bayonne, where in a letter to Joseph he admitted that he was ‘a little tired’. That did not stop him sitting up all night with Berthier dictating orders. By the evening of the next day he was in Tolosa, where he delivered a tirade to a group of monks, telling them that if they meddled in politics he would cut their ears off, which, not knowing French they could only judge the gist of by his tone. Much the same was true when, at Vitoria two days later, Joseph presented his ministers to him; he harangued them in a mixture of Italian and French, accusing them of incompetence and their clergy of being in the pay of the British, and poured scorn on the Spanish army. He declared that he would pacify the whole country in the space of two months and treat it like conquered territory.22

He took command of the Army of Spain, consisting of some 200,000 men spread across the country. While Marshal Soult on his right wing pushed back a British force of 40,000 under Sir John Moore, and on his left Lannes drove General Castaños back to Saragossa, Napoleon made for Madrid. On 12 November he reached Burgos, which had just been captured and was being put to the sack. One of his aides, Ségur, had been sent ahead, and selected the residence of the archbishop as the most suitable for his quarters. He was closely followed by Napoleon, accompanied only by Savary and Roustam. They went off in search of food and drink while Ségur lit a fire. Napoleon told him to open a window, and when Ségur pulled back the heavy curtains he was confronted by three Spanish soldiers, still fully armed, who had taken refuge there and now pleaded for their lives. Napoleon laughed at the danger he had run.23

He spent ten days in Burgos inspecting troops and then pressed on, forcing strong Spanish positions at the pass of Somosierra on 30 November, and arrived before Madrid two days later. He ordered the attack for the next day, and on 4 December the city surrendered. Napoleon took up residence in a country house at Chamartin outside the city, leaving that to his brother to repossess. From the moment he had joined Joseph at Vitoria he had ignored him, and Joseph was reduced to following in the wake of the army. He complained, with some reason, that this undermined his authority in a country which was difficult enough to rule as it was, and on 8 December wrote to Napoleon renouncing his rights to the throne of Spain.24

Napoleon did not reply for ten days, when he sent him a short note concerning finances, and a few days later a flurry of instructions through Berthier. He found time to write to Josephine frequently, mainly short affectionate notes assuring her that he was well, that his affairs were going splendidly and that she should not worry. In one, he discussed the wisdom of Hortense dismissing members of her domestic staff. He wrote to Fouché saying the Spaniards were not ‘wicked’ and the British only a minor irritant. He had a young virgin procured for himself, but according to his valet Constant she wore too much scent for his keen sense of smell, so he sent her away untouched – having paid her.25

He issued decrees and orders for the administration of the kingdom as though Joseph did not exist, abolishing feudalism and the Inquisition, closing down convents and confiscating as much property as he could to pay for his campaign. He also attended to the administration of the empire, going into details and checking figures, and specifying, for instance, what quantities of quinine should be distributed to the health services of each of the empire’s forty-two major cities.26

He reviewed the main body of his army, and on 22 December set off to confront Moore, hoping to at last have an opportunity of fighting his British enemy in the field. ‘The weather is fine, my health is perfect, do not fret,’ he wrote to Josephine before leaving. The weather changed dramatically not long after he set off, and his march over the Sierra de Guadarrama in sleet and snow proved an ordeal for the troops, which not only grumbled but in some cases actually showed their feelings by shooting at him as he passed. He thought it best to ignore the incidents and pressed on, hoping that a battle would restore morale.27

Moore retreated, making for the port of La Coruña, where the Royal Navy could evacuate his force, with Napoleon in pursuit. But on the evening of 1 January 1809, halfway between Benavente and Astorga, Napoleon was informed that an estafette from Paris was trying to reach him, so he stopped and waited by the roadside until it arrived. When he had read the despatches, his mood grew sombre and he proceeded to Astorga in silence. Those around him noted with surprise that the urge to catch up with Moore at all costs had left him. After spending a day at Astorga and handing over command to Soult, he went back to Benavente and thence to Valladolid. The despatches confirmed that Austrian rearmament was proceeding fast, but that was not what troubled him.

He was aware that there was much discontent in France. At Bayonne in June he had been notified of an inept conspiracy involving a General Malet which had been uncovered and the plotters imprisoned. Bailén had emboldened his critics in the Senate and the Legislative, but he knew he only had to crack the whip to silence them. A slip made by Josephine while receiving a delegation of the Legislative, addressing them as the representatives of the nation, had annoyed him, but it had also given him his cue; he gave instructions for Le Moniteur to carry a notice explaining that her speech must have been wrongly reported, since she was too well-versed not to know that ‘In the order of our constitutional hierarchy, the prime representative of the nation is the emperor, and the ministers, who are organs of his decisions.’ Now he was informed of what looked like an altogether more sinister machination – by two of his closest associates.28

During a reception given by Talleyrand on 20 December, just as the guests had assembled, the usher announced the minister of police. It was no secret that Talleyrand and Fouché loathed each other and were seen under the same roof only when official functions required it, yet here was Talleyrand eagerly hobbling forward to greet the new arrival and then taking him, arm in arm, through the reception rooms for all to see, deep in conversation. News that two of the most consummate practitioners of the political pirouette had combined flew round Paris, and reached the emperor at Astorga.29

What also reached him, thanks to postal intercepts by Lavalette, was an idea of what they were up to. With alarming reports of the exceptionally savage nature of the war in Spain reaching Paris, the possibility of Napoleon being killed had resurfaced, and this had drawn together the two men most concerned at the possible consequences for themselves. Both had for some time been in close touch with his sister Caroline, and were now preparing a contingency plan to put Murat on the throne if Napoleon were killed. Lavalette had passed the incriminating letters from Murat on to Napoleon.30

His exasperation showed. When he heard soldiers of the Old Guard grumbling about conditions in Spain, he made a scene on parade, accusing them of laziness and of just wanting to get back to their whores in Paris. All officers passing through the town were obliged to call on him, and when one day General Legendre, who had been Dupont’s chief of staff and signed the capitulation of Bailén, presented himself, he vented his fury on the man. He accused him of cowardice, of having defiled the honour of France, called the capitulation a crime as well as a crass show of ineptitude, and said the hand with which he had signed it should have withered. In a letter to Josephine on 9 January he urged her not to fret, but to be prepared to see him appear unexpectedly at any moment. A week later he raced back to Paris, at one stage covering 120 kilometres on horseback in five hours.31

He reached Paris at eight o’clock on the morning of 23 January. That afternoon he visited the works on the Louvre and the rue de Rivoli, over the following days he received the diplomatic corps, went to the opera and, on 27 January, wrote to Talleyrand instructing him to hand his key of grand chamberlain over to Duroc. Talleyrand complied, and wrote Napoleon a letter brimming with sweetness and submission, expressing the extreme pain with which he had done so: ‘My only consolation is to remain tied to Your Majesty by two sentiments which no amount of pain could overcome or weaken, by a feeling of gratitude and of devotion which will end only with my life.’32

29 January was a Sunday, and after the usual parade, Napoleon held a privy council attended by Cambacérès, Lebrun, Gaudin, Fouché, Admiral Decrès and Talleyrand. Towards the end of the meeting he suddenly grew agitated and, turning to Talleyrand, who was leaning against a console, unleashed his fury. ‘You’re a thief, a coward, a faithless, godless creature; you have throughout your life failed in all your duties, you have deceived and betrayed everyone; nothing is sacred to you; you would sell your own father,’ he ranted, pacing the room while Talleyrand remained perfectly still in his nonchalant pose, ‘pale as death’ according to one witness, his eyes half-closed. ‘You, sir, are nothing but a pile of shit in silk stockings!’ Napoleon concluded. Although he remained superciliously calm as he left the room, Talleyrand said quietly to grand master of ceremonies Ségur, who was just entering, ‘There are some things one can never forgive.’ And later he added, ‘What a shame that such a great man should be so ill-bred.’ He informed Metternich that he now felt free to act in the common cause. No doubt not wishing to give the impression of instability, Napoleon left Talleyrand with his rank of vice-grand elector. He did not penalise Fouché, whom he still needed, particularly as it was by now certain that he would have to go to war.33

This was a war for which neither Napoleon nor France had any appetite. It also elicited little enthusiasm outside Austria, which was getting nowhere in its search for allies. Russia was opposed to it and Prussia fearful, as were most of the German states, however much they may have resented French dominance. Even Britain was only prepared to come up with a meagre subsidy. But Austria was eager to wipe out its humiliations of Ulm and Austerlitz. And despite the lack of interest in Germany, for the first time in its history the Habsburg monarchy was going to play the German national card. A powerful influence was the Emperor Francis’s third wife, Maria Ludovica, a German nationalist with a hatred of all things French, whom he had married in January 1808. Another was the chief minister, Count Johann Philipp Stadion, who encouraged nationalist propaganda through the press and government-sponsored pamphlets, in which the coming war was represented as one of liberation and parallels were drawn with that raging in Spain.34

The thirty-seven-year-old Archduke Charles had been reorganising the army, introducing conscription and giving it a more national character. In March 1809 he appointed the nationalist writer Friedrich Schlegel as his military secretary. His brother Archduke John also struck a national note, declaring himself to be ‘German, heart and soul’. By the spring of 1809 Austria had mustered around 300,000 men. A force of 30,000 was deployed in Galicia under Archduke Ferdinand to check the Polish forces in the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and deter the Russians from supporting their French allies. Another 50,000 under Archduke John were poised to stop a French move out of Italy. The main army of nearly 200,000 under Archduke Charles invaded France’s ally Bavaria on 10 April and entered Munich. This coincided with a planned insurrection in the Tyrol led by the partisan Andreas Hofer which forced the French and Bavarian troops stationed there to capitulate. The Austrian advance was accompanied by an appeal to the people of Germany to rise. It was answered by a Prussian officer, Major Schill, who led his regiment out to attack Westphalia, and by the Hessian Colonel Dornberg, an officer in Westphalian service who sallied forth at the head of 6,000 men to raise a general rebellion. With his main forces tied down in Spain, Napoleon could only muster 100,000 French troops, along with a total of 150,000 less reliable and certainly less motivated men supplied by his various allies. As soon as news came on the telegraph that the Austrians had invaded Bavaria, he went into action.35

Although he still moved fast, travelling at all hours of the day and night, Napoleon had introduced a modicum of comfort into his campaigning, as his age no longer permitted subjecting himself to the rigours of sleeping out in all weathers and going without food. His travelling carriage was equipped with every comfort, and he kept adding resources. He loved nécessaires of one sort or another, cases containing every conceivable utensil required for their purpose, be it washing or writing. He was followed or preceded by fourteen wagons and a train of mules bearing a set of five tents of blue-and-white-striped ticking – two of them, his bedroom and study, private; the other three also used by his staff. The wagons also carried everything else he might need, from spare uniforms and linen to dining silver and a supply of Chambertin. Closer to hand, one of his pages carried a telescope and another maps, which Napoleon would spread out on a table, or sometimes on the ground, and lie down on it, pincushion in hand, then stand up, surveying the picture and dictating orders briskly. His Mameluke was always in attendance, as was a small group of orderlies, officiers d’ordonnance, some of them civilians, dressed originally in green and later pale-blue uniforms. Not far behind was a supply of spare horses, mostly Arabs. He was always escorted by a couple of dozen mounted chasseurs or chevau-légers of the Guard, while Berthier and the general staff were escorted by his own guards from his principality of Neuchâtel, uniformed in bright Serin yellow. Napoleon always seemed at his happiest when on campaign, spending much of the day in the saddle, surrounded by his staff and cheered by his troops, whom he would stop and talk to. The exercise invigorated him, and his high spirits were contagious. When he paused for something to eat, a picnic would be deftly spread out by his maison militaire and all would share. ‘It was really a party for all of us,’ recalled his prefect of the palace Bausset.36

In a series of three engagements between 19 and 21 April he tried to encircle part of the Austrian army, eventually scoring successes at Eckmühl and Ratisbon (Regensburg). He would later claim that Eckmühl was one of his finest manoeuvres, but these were not the victories he had been used to. The Austrians had learned to move and fight well, and retreated in good order. Riding over the battlefields, Napoleon was unpleasantly struck by the carnage involved in achieving victory. He had himself been lightly wounded in the foot by a spent musketball at Ratisbon. In his proclamation issued after the battle, he praised his troops for having once more demonstrated ‘the contrast between the soldiers of Caesar and the rabble of Xerxes’, and listed fictitious numbers of guns, standards and prisoners taken. To Cambacérès he wrote that it had been a finer victory than Jena. Few were fooled. Cambacérès replied that everyone was delighted by the news of the victories. ‘Yet, Sire, in the middle of the general happiness your people are greatly alarmed at the dangers to which you expose yourself,’ he wrote on 3 May.37

Napoleon’s attempts to outflank and cut off the retreating Archduke Charles came to nothing, and although he reached Vienna on 11 May and took up residence at Schönbrunn once more, he had little to rejoice over. His army had been bloodied and it had underperformed, largely because his seasoned troops and some of his best commanders, such as Ney and Soult, were in Spain, while Murat was in Naples. This time he had had to make a show of bombarding the city before Vienna opened its gates; the inhabitants nevertheless showed their admiration for him by cheering as he rode up to the walls. Archduke Charles had regrouped on the north bank of the Danube, and getting the French army across was not going to be easy.

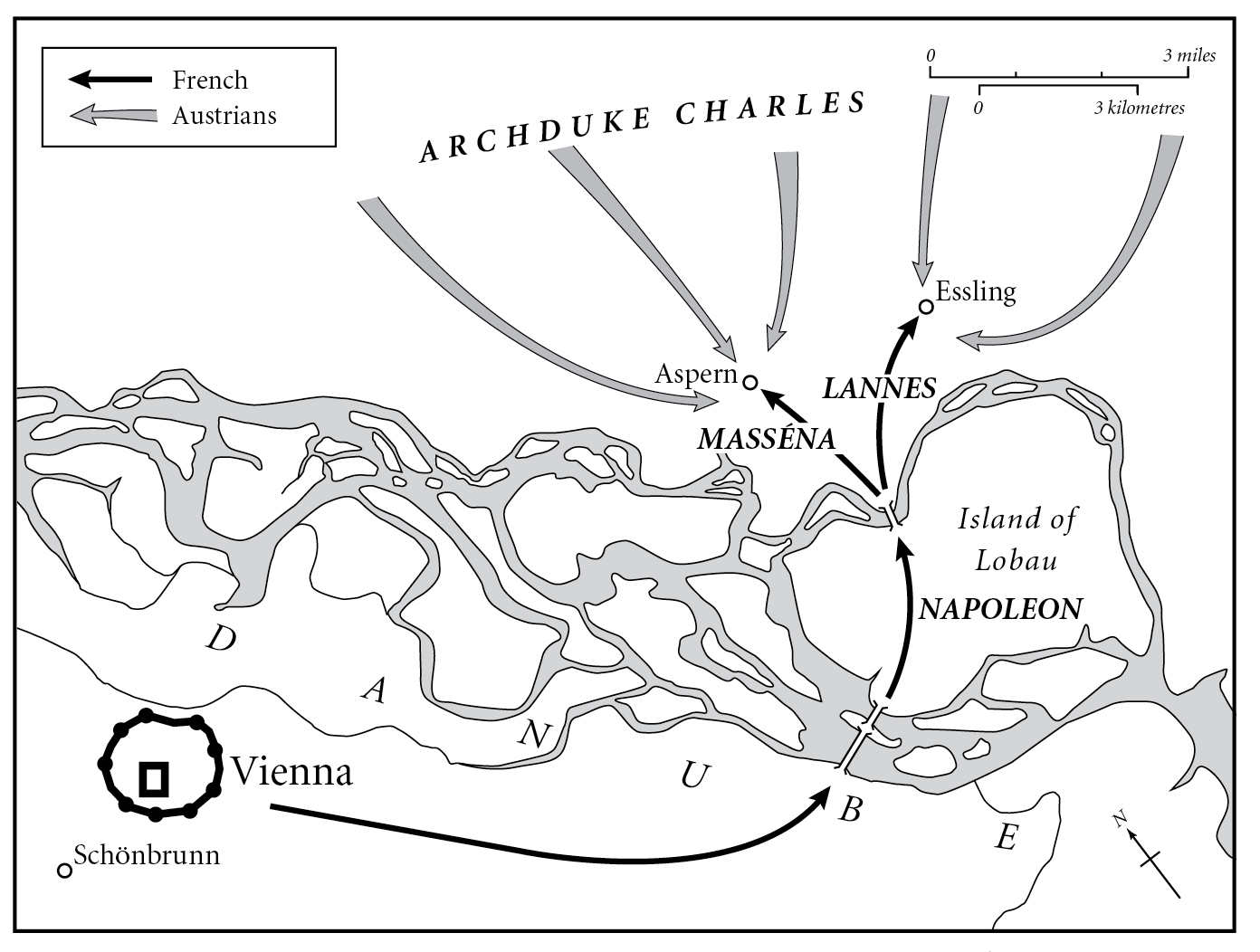

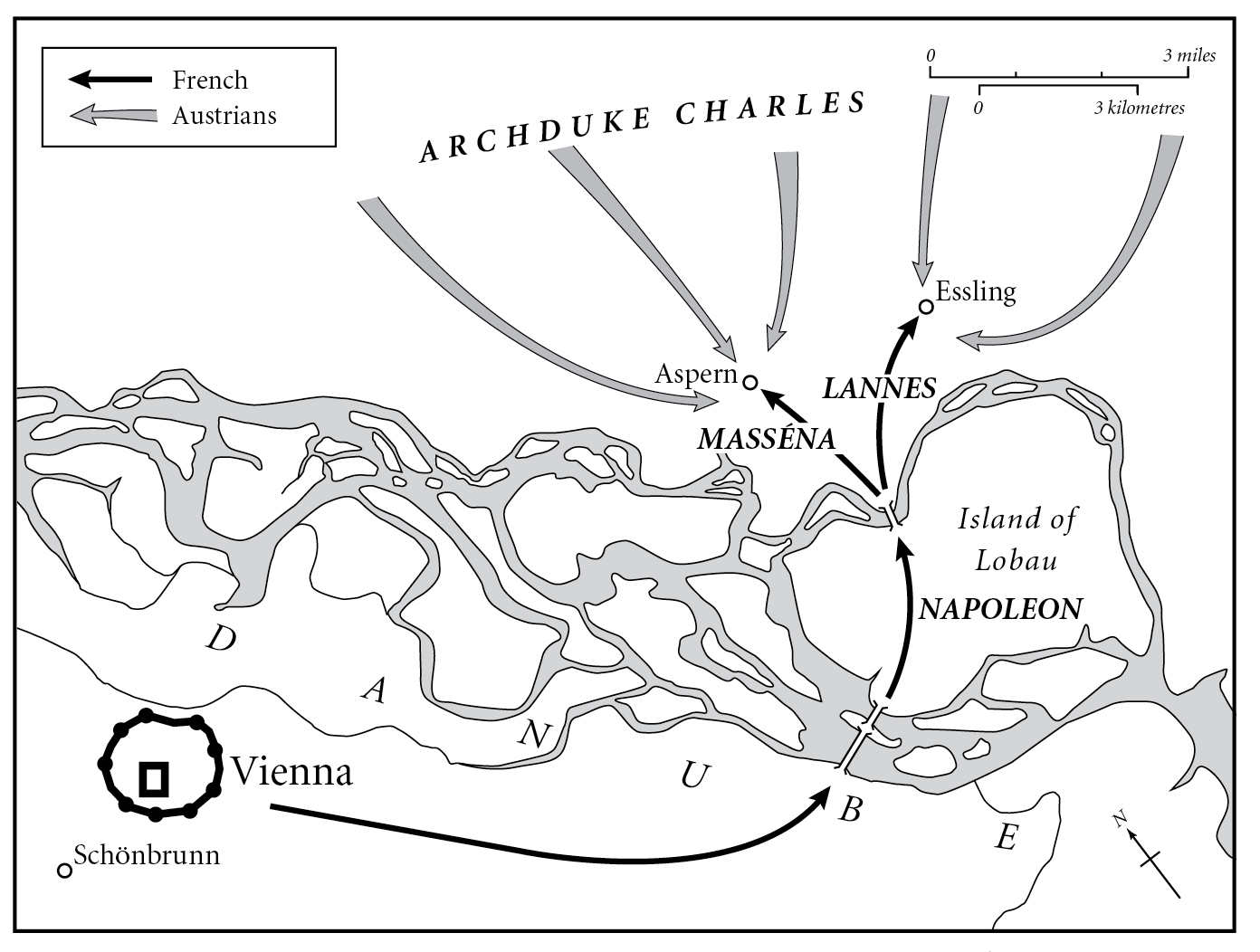

Napoleon chose the stretch where the Danube divides into two narrower streams around the large island of Lobau, and on 19 May his engineers began building pontoon bridges. The following afternoon he was on Lobau, and began moving his troops across the second branch of the river. By the morning of 21 May some 25,000 to 30,000 had made it across and taken up positions in the villages of Aspern and Essling, facing about 90,000 Austrians. At this point the Austrians destroyed his bridges by floating heavily loaded barges down the river, which was in spate. The engineers struggled to repair them, but with more heavy objects being floated downriver Napoleon’s army was stranded in three places, while Archduke Charles seized his chance and opened up on the French positions with heavy artillery. Fierce fighting developed as he tried to get between Masséna’s corps at Aspern and the river, while Napoleon himself clung on at Essling. With the bridges repaired more men got across, bringing French numbers up to around 60,000 on the morning of 22 May. Napoleon launched an attack which was returned, and the two villages changed hands several times. Although the French had held their ground, the bridges at his back had been set alight by incendiary barges, preventing reinforcements from coming up, so at nightfall Napoleon pulled all his forces back onto the island. Both sides claimed victory, the Austrians naming it Aspern and the French Essling, but there was little to celebrate on either side. Losses had been heavy – more than 20,000 Austrians and upwards of 15,000 French.38

A harrowing personal loss for Napoleon was that of Marshal Lannes, who had both legs crushed by a cannonball. Larrey amputated in an attempt to save his life, and the physicians struggled to keep him alive. Napoleon visited him every evening, but Lannes had been badly concussed. ‘My friend, don’t you recognise me?’ Napoleon allegedly asked. ‘It’s your friend Bonaparte.’ He died on 31 May. On hearing the news Napoleon hurried over and embraced the lifeless body. He was in tears, and had to be dragged away by Duroc. Lannes had been one of his closest and, according to Fouché, the only one of Napoleon’s friends who was still able to tell him the truth. He ordered the body to be embalmed and taken back to France.39

Napoleon was cheered by the news from the south, where Eugène had forced the Austrians out of Italy, and General Étienne Macdonald had ousted them from Dalmatia. He turned the island of Lobau into a fortress and a launchpad for his next offensive, and spent most of June bringing up reinforcements. He would go there nearly every day and often, donning a soldier’s overcoat and carrying a musket, venture out to observe enemy positions. On 14 June Eugène and Macdonald defeated Archduke John at Raab and joined forces with Napoleon, giving him a comfortable superiority over Archduke Charles. On the night of 4 July, in a violent thunderstorm Napoleon began crossing to the north bank of the Danube.