Omens of destiny were not in short supply. Having reached the furthest outposts, in the early hours of 23 June Napoleon borrowed a Polish lancer’s cap and cloak and rode out, with his staff similarly disguised as a regular patrol, to scout the river Niemen for a good crossing point. A hare started from under his horse’s hooves and he was thrown. Instead of cursing and blaming the horse as he usually did, he remained tight-lipped and remounted without a word. Berthier and Caulaincourt, who were in attendance, took it as a bad omen, and said they should not cross the river.1

Napoleon spent the rest of the day working in his tent, in sombre mood. This contrasted sharply with the elation he normally displayed at the start of a campaign, and his entourage noted it with apprehension. He issued a proclamation to the army which announced the commencement of ‘The Second Polish War’, assuring his men that as well as being ‘glorious for French arms’, it would bring about a lasting peace and ‘put an end to that arrogant influence which Russia has been exerting on the affairs of Europe over the past fifty years’.2

At three on the morning of 24 June he was in the saddle once more, mounting a horse named Friedland, and as the sun came up he could see three pontoon bridges which had been thrown across the river, and one division taking up defensive positions on the other side. He took his place on a knoll overlooking the scene and watched, a telescope in his right hand and his left behind his back. The huge army, dressed as for a parade, was crossing the river, the morning sunshine glinting on the helmets and breastplates of cuirassiers and dragoons, and on every polished cap badge and belt buckle, and lighting up the blue, white, yellow, green, red and brown uniforms of the various allied contingents. He seemed in a good mood, and hummed military marches as he contemplated what one witness described as ‘the most extraordinary, the most grandiose, the most imposing spectacle one could imagine, a sight capable of intoxicating a conqueror’.3

‘Vive l’Empereur! The Rubicon has been crossed,’ noted a captain of grenadiers of the Guard in his diary at a bivouac outside Kowno (Kaunas) on 26 June, adding that some ‘fine pages’ would be added to the annals of the French nation. Four days later Napoleon entered Vilna, which had just been evacuated by the Russians. He was greeted by a municipal delegation, but the inhabitants had not had time to prepare the usual trappings, and his entry into the city was anything but triumphal. And as he bedded down for the night in the former archbishop’s palace, where Alexander had slept the night before, a primeval storm burst on the area to the south and west of the city.4

Men and horses exhausted by lack of food and fodder, as well as by the intense heat of the past weeks, were suddenly drenched by a downpour of cold rain which lasted through the night. The morning sun revealed a landscape littered with dead or dying horses and men, of wagons, guns and gun carriages mired in mud, and those still alive struggling to get free. Some artillery units lost a quarter of their horses, and the cavalry did not fare much better, but it was the supply services which suffered the most; at a conservative estimate the French army lost around 50,000 horses that night.5

The psychological damage was hardly less significant. As the men trudged on through the quagmire that had replaced the dusty roads, they could see dead and dying men and beasts by the roadside, and rumours of grenadiers having been struck by lightning passed from rank to rank. Had they been Greeks or Romans in ancient times they would undoubtedly have turned about and gone home after such an augury, quipped one of Napoleon’s aides.6

Napoleon was baffled by the behaviour of the Russians, who had shown every sign of meaning to defend Vilna, yet decamped at his approach, leaving behind stores accumulated over months. It made no sense, and he instructed his commanders to proceed with caution, expecting a counter-attack. He need not have bothered. Barclay was a fine general, but although he was also minister of war, Alexander had not given him overall command, and hovered at his side limiting his freedom of action. In the absence of any fixed plan, he thought it best to fall back.

On 1 July Napoleon received an envoy from Alexander, General Balashov, who brought a letter proposing negotiations conditional on a French withdrawal. ‘Alexander is making fun of me,’ Napoleon retorted: he had not come all this way in order to negotiate, and since Alexander had refused to do so before, it was time to deal once and for all with the barbarians of the north. ‘They must be thrown back into their icy wastes, so that they do not come and meddle in the affairs of civilised Europe for the next twenty-five years at least.’7

Balashov could hardly get a word in as Napoleon paced the room, venting his frustration in a monologue which veered from whining complaints to squalls of anger. He professed his esteem and love for Alexander, and reproached him for surrounding himself with ‘adventurers’. He could not understand why they were fighting, instead of talking as they had at Tilsit and Erfurt. ‘I am already in Wilna, and I still don’t know what we are fighting over,’ he said. He shouted, stamped his foot and, when a small window which he had just closed blew open again, tore it off its hinges and hurled it into the courtyard below. But in the reply to Alexander which he handed to Balashov he professed continuing friendship, peaceful intentions, and a desire to talk, without accepting the precondition of a withdrawal behind the Niemen.8

‘He has rushed into this war which will be his undoing, either because he has been badly advised, or because he is driven by his destiny,’ he declared after Balashov had gone. ‘But I am not angry with him over this war. One more war is one more triumph for me.’ On 11 July he issued a mendacious Bulletin announcing great military successes, achieved at the cost of no more than 130 French casualties.9

On the same day as Napoleon’s interview with Balashov, the Polish patriots of Vilna had held a Te Deum in the cathedral, followed by a ceremony of reunification of Lithuania with Poland. Napoleon had hoped that he would be able to defeat the Russians and reach an agreement with Alexander before he had to confront the Polish question, since that would probably have been part of the deal. But now he was being pressed to commit himself. In an attempt to duck the issue, on 3 July he set up a government for Lithuania, to administer the country, gather supplies and raise troops, and instructed his foreign minister Maret, whom he had brought to Vilna, to string them along.

On 11 July, eight delegates from the national confederation which he had called for in Warsaw arrived in Vilna. The emperor kept them waiting three days, then listened impatiently to their request that he announce the restoration of the kingdom of Poland. ‘In my position, I have many different interests to reconcile,’ he told them, but added that if the Polish nation arose and fought valiantly, Providence might reward it with independence. With this speech, he cooled the ardour of the Poles and robbed himself of what would have been a powerful weapon; the investigation conducted by the Russians after the war revealed that the population of the area in which he was operating was on his side, yet he would not engage its support or even sanction popular initiatives to act behind enemy lines lest it hinder chances of a reconciliation with Alexander.10

In his proclamation launching his ‘Second Polish War’, he had written that he was taking the war into Russia, giving his troops the impression that from the moment they crossed the Niemen they were in enemy territory, and therefore licensed to behave as they liked. ‘All around the city and in the countryside there were extraordinary excesses,’ noted a young noblewoman of Vilna. ‘Churches were plundered, sacred chalices were sullied; even cemeteries were not respected, and women were violated.’ With no fighting to do and no palpable purpose to the campaign, tens of thousands of men had deserted and were roaming the countryside in gangs, attacking manor houses and villages, raping and killing, sometimes in collusion with mutinous peasants. ‘The path of Attila in the age of barbarism cannot have been strewn with more horrible testimonies,’ in the words of one Polish officer. In view of their numbers there was no way of enforcing the law, and those rounded up deserted again at the first opportunity. Officials were not safe, and estafettes were attacked.11

Apart from cooling the ardour of the local patriots, this complicated what was already a challenge. Napoleon was operating with huge army corps at distances that would have presented a problem in well-mapped areas with good roads. Couriers and staff officers struggled to find their way down sandy tracks, through boggy wildernesses and interminable forests. It was difficult for them to locate the commanders they were seeking, as these were themselves on the move, and many of the troops encountered along the way were not familiar enough with the marshals and generals to recognise them, while many could not speak French. Napoleon could not act or react as fast as he was wont to, which frustrated his plans.

He had managed to drive a wedge between Barclay’s First Army and Bagration’s Second, and had sent Davout with two divisions and Grouchy’s cavalry corps to cut Bagration’s line of retreat and crush him against Jérôme’s advancing corps. But Jérôme had got off to a slow start, and failed to pin down Bagration, who was able to swerve south and get clear before the French pincers closed. Napoleon berated him, reprimanded Eugène and insulted Poniatowski, both of whom were under his orders.12

The failure to destroy Bagration was his own fault; it had been his idea to give Jérôme such an important role. He had quickly come into conflict with his corps commanders and his own chief of staff. Napoleon had instructed Davout to oversee the combined operation but had failed to notify Jérôme, so Davout and Jérôme also fell out. Jérôme decided to go home, and, taking with him his royal guards and his only trophy of war, a Polish mistress, on 16 July began his march back to Kassel. ‘You have made me miss the fruit of my cleverest calculations, and the best opportunity that will have presented itself in this war,’ wrote a furious Napoleon. For good measure, he reproved Davout for his handling of the situation.13

‘I am very well,’ Napoleon wrote to Marie-Louise that day. ‘Kiss the little one for me. Love me, and never doubt my feelings for you. My affairs are going well.’ They were not. Having himself wasted two weeks at Vilna, he had allowed the Russians to retreat in good order to a previously fortified camp at Drissa. When he got news of this, he decided to sweep round into their rear and trap them in it. But by the time he set off they had changed their plan and abandoned the camp, robbing him of his chance of a battle. On 21 July he nevertheless wrote a triumphant letter to Cambacérès announcing the capture of the camp.14

He resumed his pursuit, and took heart when Murat engaged the Russian rearguard at Ostrovno. ‘We are on the eve of great events,’ he wrote to Maret on 25 July, and sent off a note to Marie-Louise brimming with optimism. Two days later he caught up with Barclay, who was preparing to give battle before Vitebsk. It was midday, and he could have engaged him immediately. Instead he decided to wait for all his troops to catch up, and postponed the attack to the following morning. That evening Barclay received news that Bagration, whom he had been expecting, could not make it, so he decided to strike camp silently in the night and resume his retreat. The French rose early and prepared for battle only to find the Russians had vanished.15

Napoleon was baffled, and spent a day scouting the surrounding area before deciding to pause and give his army a rest. The men had marched under scorching sun, in temperatures recognised only by the veterans of the Egyptian campaign, along dusty roads through swarms of mosquitoes and horseflies, suffering agonies of thirst, since wells were few and far between. Many had wandered off in search of victuals and never been seen again, some had died of heatstroke or dehydration, others had fallen ill from drinking from brackish puddles or even horses’ urine. The cavalry had been concentrated in a great body under Murat, which meant that even when they did find water, the tens of thousands of horses could not all be watered, and as there was no forage, they were lucky to find some old thatch to eat off a cottage roof. Some units were down by a third, and Napoleon had lost as many as 35,000 men without a battle since leaving Vilna.16

He took up quarters in the governor’s residence at Vitebsk, where he spent the next two weeks, undecided as to what to do next. He contemplated stopping there and turning Vitebsk into a fortified outpost. He wrote to his librarian in Paris requesting ‘a selection of amusing books’. It was still extremely hot, and while his troops bathed in the river Dvina he sweated as he worked at tidying up his army. He issued confident-sounding Bulletins, wrote to Maret in Vilna instructing him to publicise non-existent successes, and blustered in front of the men, but in the privacy of his own quarters he was irritable, shouting at people and insulting them. He received news of the treaty between Russia and Turkey, and details of that between Russia and Sweden signed in March. What he did not know was that Russia had also signed a treaty of alliance with Britain on 18 July. But he was cheered by the news of the outbreak of war between Britain and the United States of America.17

He had been greeted in Vitebsk by local Polish patriots, and evaded their questions as to his intentions by heaping abuse on Poniatowski and the alleged cowardice of the Polish troops, which, he claimed, was largely responsible for the failure to catch Bagration. ‘Your prince is nothing but a c—,’ he snapped at one Polish officer. To Maret in Vilna he sent contradictory instructions regarding the Polish question. Many argued that this was the moment to send Poniatowski south into Volhynia. This would have raised an insurrection in what had been Polish Ukraine, which would have yielded men and horses as well as supplies. More important, it would have tied down the Russian forces in the south, under Chichagov and Tormasov. But, as he admitted to Caulaincourt, he was more interested in using Poland as a pawn than in restoring it.18

Unusually for him, Napoleon consulted a number of generals on what to do next. Berthier, Caulaincourt, Duroc and others felt it was time to call a halt. They cited losses, provisioning difficulties and the length of the lines of communication, and expressed the fear that even a victory would cost them dear, on account of the lack of hospitals and medical resources in the area. But Napoleon hankered after a battle to show for his pains, and hoped that now they were on the borders of Russia proper, Barclay would have to fight. ‘He believed in a battle because he wanted one, and he believed that he would win it because that was what he needed to do,’ wrote Caulaincourt. ‘He did not for a moment doubt that Alexander would be forced by his nobility to sue for peace, because that was the whole basis of his calculations.’ Leaping out of his bath at two o’clock one morning he suddenly announced that they must advance at once, only to spend the next two days poring over maps and papers. ‘The very danger of our situation impels us towards Moscow,’ he said to Narbonne. ‘I have exhausted all the objections of the wise. The die is cast.’19

He marched out of Vitebsk on 13 August, meaning to cross the Dnieper and take Smolensk from the south before the Russians could prepare a defence, and then use its bridges to recross the river into Barclay’s rear. As a result of confused manoeuvring caused by differences between Barclay and Bagration, who had now joined forces, Smolensk was full of Russian troops. There was no value in taking this thickly-walled fortress, and Napoleon could have recrossed the river further east and forced Barclay to give battle by coming between him and Moscow. He nevertheless decided to storm it. The murderous battle cost him 7,000 casualties and reduced Smolensk to a scorched charnel house strewn with the corpses of the defenders and citizens who had died in the bombardment and fire that engulfed it.

Barclay resumed his retreat, with Ney in pursuit. Napoleon had sent Junot to cross the river further east, and he was in a position to cut the Russian line of retreat, but Junot had a mental blackout and his generals could not get an order out of him, and since Napoleon did not bother to ride out to see what was going on, the manoeuvre came to nothing. Ney, supported by Davout and Murat, fought hard but could not stop the Russians from making good their retreat.

The following morning Napoleon rode out to the scene. ‘The sight of the battlefield was one of the bloodiest the veterans could remember,’ according to a lancer of his escort. The troops paraded on the field of battle, and he awarded the coveted eagle that topped the colours of regiments which had earned it to the 127th of the Line, made up largely of Italians, which had distinguished itself the previous day. ‘This ceremony, imposing in itself, took on a truly epic character in this place,’ in the words of one witness. Napoleon took the eagle from the hands of Berthier and, holding it aloft, told the men, their faces still smeared with blood and blackened by smoke, that it should be their rallying point, and they must swear never to abandon it. When they had sworn the oath, he handed the eagle to the colonel, who passed it to the ensign, who in turn took it to the elite company, while the drummers delivered a deafening roll. Napoleon dismounted and walked over to the front rank. In a loud voice, he asked the men to name those who had distinguished themselves in the fighting. He promoted those who were named and gave the Legion of Honour to others, dubbing them with his sword and giving them the ritual embrace. ‘Like a good father surrounded by his children, he personally bestowed the recompense on those who had been deemed worthy, while their comrades acclaimed them,’ in the words of one officer. ‘Watching this scene,’ wrote another, ‘I understood and experienced that irresistible fascination which Napoleon exerted when he wished to.’ By this means he managed to turn the bloody battlefield into one of glory, consigning those who had died to immortality and caressing those who had survived with words and rewards. But many asked what, if anything, had been achieved by the past four days of bloodletting.20

Napoleon had beaten the Russians and taken a major city, but while he had inflicted heavy losses, he had lost as many as 18,000 men in the two engagements, with nothing to show for it. According to Caulaincourt, over the next few days he behaved like a child who needs reassurance. ‘In abandoning Smolensk, one of their holy cities, the Russian generals have dishonoured their arms in the sight of their own people,’ he claimed. He fantasised about turning it into a base, from which he would attack either Moscow or St Petersburg the following year. But the burnt-out city represented no military value. Yet to retreat now was politically unthinkable. He had walked into a trap from which he could see no viable issue.21

He vented his frustration on anything that came to hand. He blamed the Lithuanians for failing to raise enough troops and supplies, he reprimanded the corps commanders, and when he came across some soldiers looting one day, he attacked them with his riding crop, yelling obscenities. In his desperation to find a way out, he tried to persuade a captured Russian general to write to the tsar. ‘Alexander can see that his generals are making a mess of things and that he is losing territory, but he has fallen into the grip of the English, and the London cabinet is whipping up the nobility and preventing him from coming to terms,’ he lectured Caulaincourt. ‘They have convinced him that I want to take away all his Polish provinces, and that he will only get peace at that price, which he could not accept, as within a year all the Russians who have lands in Poland would strangle him like they did his father. It is wrong of him not to turn to me in confidence, for I wish him no ill: I would even be prepared to make some sacrifices in order to help him out of his difficulty.’22

Most of his entourage begged him to go no further, but he felt he could not return home without a victory. Moscow was only just over two weeks’ march away, and the Russians would surely make a stand in its defence. ‘The wine has been poured, it has to be drunk,’ he told Rapp. When Berthier nagged him once too often on the subject, he turned on him. ‘Go, then, I do not need you; you’re nothing but a … Go back to France; I do not force anyone,’ he snapped, adding a few lewd remarks about what Berthier was longing to get up to with his mistress in Paris. The horrified Berthier swore he would not dream of abandoning his emperor, but the atmosphere between them remained frosty, and Berthier was not invited to the imperial table for several days.23

While senior officers shook their heads, the younger ones were excited by the prospect of a march on Moscow. ‘The whole army, the French and our foreign auxiliaries, was still full of ardour and confidence,’ according to the twenty-one-year-old Lieutenant de Bourgoing. ‘If we had been ordered to march to conquer the moon, we would have answered: “Forward!”’ recalled Heinrich Brandt of the Legion of the Vistula. ‘Our older colleagues could deride our enthusiasm, call us fanatics or madmen as much as they liked, but we could think only of battles and victories. We only feared one thing – that the Russians might be in too much of a hurry to make peace.’24

As they penetrated Russia proper, the character of the war changed. The retreating Russians adopted a scorched-earth policy, forcing the population out of their homes and burning them, along with standing crops and anything that might provide shelter or provender to the advancing army. ‘At night, the whole horizon was on fire,’ in the words of one soldier. They poisoned wells with dead animals. They felled trees and left overturned carts in the road, and, as their retreat grew less orderly, corpses of men and horses, which rotted in the sweltering heat. Yet the men marched on, confident in what one soldier called ‘the vast genius’ of their ‘father, hero, demi-god’.25

Napoleon was uneasy at the sight of the burning villages, but concealed his feelings by heaping ridicule on the Russians and calling them cowards. ‘He sought to avoid the serious reflections which this terrible measure raised as to the consequences and duration of a war in which the enemy was prepared to make, from the very outset, sacrifices of this magnitude,’ explains Caulaincourt. He nevertheless continued to clutch at every straw; on 28 August he seized an opportunity to write to Barclay, hoping to open up a channel of communication with Alexander.26

Two days later, when he and his entourage stopped for lunch by the roadside, Napoleon walked up and down in front of them, holding forth about the nature of greatness. ‘Real greatness has nothing to do with wearing the purple or a grey coat, it consists in being able to rise above one’s condition,’ he declaimed. ‘I, for instance, have a good position in life. I am emperor, I could live surrounded by the delights of the great capital, and give myself over to the pleasures of life and to idleness. Instead of which I am making war, for the glory of France, for the future happiness of humanity; I am here with you, at a bivouac, in battle, where I can be struck, like any other, by a cannonball … I have risen above my condition …’ But the following day an estafette from Paris brought news that in Spain Marmont had been defeated by Wellington at Salamanca on 22 July. ‘Anxiety was clearly visible on his usually serene brow,’ according to General Roguet, who lunched with him that day.27

The Russians were as desperate as Napoleon for a battle, but the speed of the French advance had prevented Barclay from getting his troops into position. Under pressure from public opinion Alexander replaced him with the popular Mikhail Ilarionovich Kutuzov, a sly, gout-ridden, fat sixty-six-year-old with a talent to rival Napoleon’s for falsifying facts to build up his image. It was not until 3 September that Kutuzov chose a defensive position in which to stand and fight, in front of the village of Borodino.

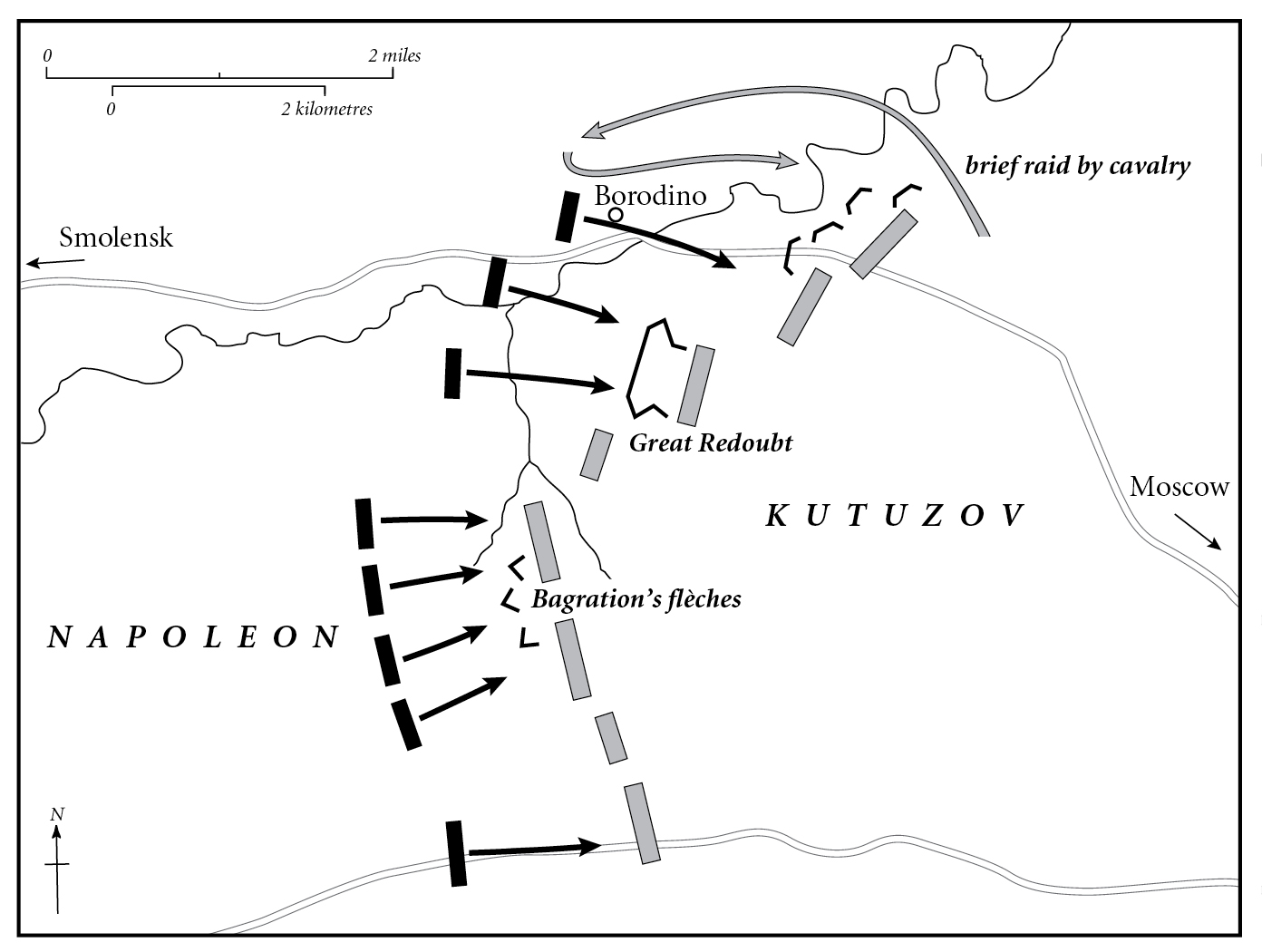

Napoleon reached the scene two days later. He ordered an exposed Russian redoubt to be captured, then spent a day reconnoitring and preparing for battle. Kutuzov had built a formidable earthwork redoubt on a slight rise at the centre of his line, covered on his left with three flèches, earthworks in the shape of chevrons. Napoleon decided to deliver a frontal assault on the redoubt while Ney, Davout and Junot took the flèches and penetrated into the Russian rear, and Poniatowski made a deeper flanking movement in support. Davout suggested that his corps be added to the Polish one so as to drive deeper into the Russian rear, but Napoleon feared engaging such a large force too deep. He had between 125,000 and 130,000 men, so he was outnumbered by the Russians with their 155,000 (about 30,000 of whom were poorly trained militia), and he was outgunned, in calibre as well as in numbers, by the 640 Russian guns to his 584.28

Napoleon was unwell. He was suffering from an attack of dysuria, an affliction of the bladder which made it almost impossible for him to urinate, and when he did only a few dark drops came out, heavy with sediment. He may also have had a fever, as he was coughing, shivering and breathing with difficulty. His spirits were lifted by the arrival of Bausset with a case containing a portrait of the King of Rome just painted by Gérard, which he immediately had unpacked. ‘I cannot express the pleasure which the sight gave him,’ noted Bausset. The proud father had the picture displayed outside his tent so his generals and soldiers could come up and admire it, and wrote a tender note to Marie-Louise thanking her for it.29

A less welcome arrival was Colonel Fabvier, who had come from Spain with details of Wellington’s victory over Marmont at Salamanca and of the worsening military position of the French in the Peninsula. News of the French defeat would give heart to all Napoleon’s enemies – not just those facing him, but, more alarmingly, those at his back. He slept badly, waking several times. At three in the morning he got up and drank a glass of punch with Rapp, who was on duty and had spent the night in his tent. ‘Fortune is a fickle courtesan,’ Napoleon suddenly said. ‘I have always said so and now I am beginning to feel it.’ After a while he added, sighing, ‘Poor army, it is much reduced, but what is left is good, and my Guard is intact.’ He then rode out to show himself to the troops.30

The army had spent the previous day buffing up, and some said it looked as fine as on a parade before the Tuileries. The men were read a proclamation which exhorted them to fight and assured them that victory would lead to a prompt return home. It contained a reference to Austerlitz, which was not out of place, since that was the last time the Grande Armée had faced Kutuzov, and when the sun came up Napoleon exclaimed, ‘Voilà le soleil d’Austerlitz!’ He then rode up to a vantage point from which he could see almost the whole field of battle, where a tent had been pitched for him, surrounded by his Guard in formation. He took the folding chair that had been set out for him, turned it back to front and sat down heavily, his arms on its back.31

At six o’clock the French guns opened up and the attack began. Assault followed assault as the Russian positions fell, only to be retaken in fierce hand-to hand fighting. The flèches were murderous traps for the troops who took them, as their only escape was forward, into the next Russian line of defence. Napoleon listened impassively as officers rode up to report. He refused all offers of food, only taking a glass of punch at around ten o’clock. He watched two assaults on the great redoubt at the centre, but failed to reinforce the successful one, while his cavalry stood idle. ‘We were all surprised not to see the active man of Marengo, Austerlitz, etc.,’ noted Louis Lejeune, an officer on Berthier’s staff. Napoleon appeared curiously remote.32

His state of health undoubtedly played a part, but so did his state of mind; unsettled by an unexpected sortie by Russian cavalry on his left wing and afraid of playing his last card so far from home, he would not commit the Guard when Davout reported that the way was open for it to sweep into the rear of the Russian army and destroy it completely. He hesitated for a couple of hours before ordering the general assault. When he did, his cavalry, which was being gradually shot to pieces by the Russian guns, surged forward and, charging up the hill, swarmed into the great redoubt, and the Russian line crumpled. Napoleon then rode over the battlefield, which presented what one of his generals describes as ‘the most disgusting sight’ he had ever seen. Russian casualties were around 45,000, including twenty-nine generals, the French 28,000 and forty-eight generals. The bodies of nearly 40,000 horses littered the ground.33

The French victory was complete; Russian losses were such that most of the units had ceased to be operational, and nothing stood between the French and Moscow. But there had been no trace of Napoleonic genius in evidence in what had been little more than a slogging match. The Russians did not flee, and there was no pursuit, as the French cavalry was exhausted. At dinner that evening with Berthier and Davout Napoleon said little and ate less. He did not sleep that night.

Kutuzov badly needed to get the remnants of his army out of the path of the French and to fall back to the south, where he could be fed and resupplied. Instead of doing so directly, he cleverly retreated to Moscow and out the other side, guessing that the city would act as a ‘sponge’ which would absorb the French and permit him to get away. He was right. Napoleon followed, and on the afternoon of 14 September from the Poklonnaia Hill he surveyed his prize – a huge and beautiful city glittering with its many gilded onion-shaped domes. But it was empty, and no delegation came out to submit to him. ‘The barbarians,’ he exclaimed. ‘They really mean to abandon all this? It is not possible.’34