At nine o’clock on the evening of 26 February 1815 the Inconstant slipped out of Portoferraio followed by six smaller craft. Temporarily becalmed, the flotilla spotted the sails of a British ship and in the course of its onward journey crossed the paths of three French naval vessels, but the soldiers lay down on deck to keep out of sight, and it reached the coast of France without incident, sailing into the Golfe Juan on 1 March.

A few curious locals came to gawp at the unusual number of ships in the bay, but there was little interest even when Napoleon came ashore late that afternoon and made camp on French soil once more. Twenty men sent off to nearby Antibes were arrested. Napoleon had instructed his soldiers not to use their weapons, and it is doubtful they would have even if he had wished; when questioned later they admitted that they were delighted to be back in France, but had no stomach for fighting fellow Frenchmen. In the event, they had no need to. They set off at midnight, along side roads in order to avoid confrontation, attracting little attention as they went. The soldiers had grown unused to long marches, and they had to carry all their equipment as they had brought only a few horses, so the column soon stretched into an untidy string of small groups struggling along as best they could. They bought horses along the way, but these were passed to the lancers, who had been lugging their saddles as well as their arms.1

In two proclamations, from his Guard calling on former comrades to join them and from him to his people, in which he branded Marmont and Augereau as traitors, Napoleon portrayed himself as coming to the rescue of suffering France, whose laments had reached him on Elba, and announced that ‘The eagle bearing the national colours will fly from belfry to belfry all the way to the towers of Notre Dame.’ There was no eagle and no national colours – until in one small town someone produced a gilded wooden bedpost or curtain-rail finial in the shape of one which was attached to a pole and adorned with strips of blue, white and red cloth.2

They met no resistance until they reached Laffrey on 7 March, where they found the road barred by infantry. Napoleon rode forward and addressed the soldiers. He was answered with silence, so he unbuttoned his grey coat and, baring his breast, challenged them to shoot, at which, encouraged by his grenadiers who had stepped forward and started cheering, the royal troops burst into shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’3

A larger force drawn up outside Grenoble would have presented a greater obstacle had it not been for Colonel La Bédoyère leading his regiment over to Napoleon’s side. The royalist commander of Grenoble closed the gates of the city, but they were hacked open by workers, who ushered Napoleon in to a delirious welcome. At Lyon the populace tore down the barricades blocking the bridges and led him into the city in triumph. From then on the eagle did fly on to Paris with astonishing speed. Ney, who had been sent out to capture Napoleon and had solemnly promised Louis XVIII to bring him back in a cage, realised that his troops were wavering and, swayed by the prevailing mood, joined his former master.

By 20 March Napoleon was at Fontainebleau. At Essonnes later that day he was met by Caulaincourt and a multitude of officers and men who had driven out of Paris or from the surrounding area. The previous night Louis XVIII had left the Tuileries and fled for the Belgian frontier. As the news spread, supporters of the emperor came out all over the capital and the tricolour flag was hoisted on the palace and other public buildings. As Napoleon raced on to Paris his former staff and servants took over the Tuileries, so that by the time he arrived at nine o’clock that evening all was ready, and the salons were thronged with members of his erstwhile court. When he alighted, he had difficulty in making his way through the waiting crowd. As he mounted the staircase to repossess the palace, he closed his eyes and a smile lit up his face.4

Within an hour of reaching the Tuileries he was working in his study with Cambacérès and Maret, putting together a new government. He had some difficulty in persuading his old ministers to take up their jobs again, as most of them were feeling their age and were tired out by what they had been through. The memory of the uncertainties of 1814 was still fresh, and when they heard of his landing, some, like Pasquier and Molé, despaired for France, foreseeing more of the same. But most let themselves be swayed by the old charm. Daru, reluctant at first, soon melted. ‘I felt I was back in my world, where my memories and my affections lay,’ he recalled. ‘At no other moment had I felt more affection, more devotion for the emperor.’ But some, like Macdonald, resisted despite repeated efforts by Napoleon.5

Cambacérès agreed to serve as minister of justice, Maret took up again as secretary of state, Caulaincourt (under severe pressure) as foreign minister, Carnot took the ministry of the interior, Davout that of the army, Decrès resumed his old post at the navy, as did Gaudin and Mollien at finance and the treasury respectively. Napoleon appointed Fouché minister of police, with Savary and Réal briefed to keep an eye on him. ‘It was an extraordinary sight to see things put back in their place so quickly,’ reflected Savary. When he called on the evening of the next day, Lavalette felt as though he had gone back ten years in time; it was eleven o’clock at night, Napoleon had just had a hot bath and put on his usual uniform, and was talking to his ministers.6

But the appearances did not hold up for long. When the legislative bodies came to present their addresses of loyalty on 26 March, Miot de Melito, now a member of the Council of State, noticed that ‘the faces were sad, anxiety was etched on every feature, and there was general embarrassment’. The enthusiasm caused by the unexpected and almost miraculous return of Napoleon subsided, as, in the words of Lavalette, ‘it was not so much that people wanted the emperor; it was just that they no longer wanted the Bourbons’. Napoleon realised this. ‘My dear,’ he replied when Mollien congratulated him on his remarkable return to power, ‘don’t bother with compliments; they let me come just as they let the other lot leave.’ Few felt much confidence in the future.7

Taking in hand the administration of the country presented a formidable challenge. Napoleon’s authority did not reach far outside the mairie in many areas, and not even there in the north and west, where royalist sentiment was strong. In the Midi, the king’s nephew the duc d’Angoulême gathered 10,000 troops and national guards and marched on Lyon. He was forced to capitulate by Marshal Grouchy on 8 April and allowed to leave the country, but civil war simmered below the surface. In these circumstances, raising men for the army and funds to equip it would not be easy – Louis XVIII had emptied the coffers, leaving only two and a half million francs in the treasury.

Napoleon was no longer the man to galvanise the nation. He was forty-five years old and not well; his physical condition had been aggravated by haemorrhoids and perhaps other ailments. He had grown fat and had slowed down. ‘Great tendency to sleep, result of his illness,’ noted Lucien, who had turned up in Paris to support his brother. Napoleon himself admitted to being surprised that he had found the energy to leave Elba at all. ‘I did not find the emperor I had known in the old days,’ noted Miot de Melito after a long interview. ‘He was anxious. That confidence which used to sound in his speech, that tone of authority, that loftiness of thought that was manifest in his words and in his gestures, had vanished; he already seemed to feel the hand of adversity which would soon weigh down on him, and he no longer appeared to believe in his destiny.’ Most noticed the change, and it did not inspire confidence; all they could see was a small, fat, anxious man with an absent look and hesitant gestures.8

His hesitancy was partly a consequence of his not being able to find the right persona to adopt and image to project, as he had so successfully done on his returns from Italy and Egypt, after Tilsit and even following the disaster of 1812. He now had to be all things to all men. He left the Tuileries, which required a large maison and formal etiquette, both of which were expensive and inappropriate; Letizia, Fesch, Joseph, Lucien and Jérôme had all turned up to support the family business, but were given no formal status. He moved into the Élysée Palace, where he was freer to see whom he wished without the complications of a large court. His only regular company was his family, a few of the more faithful ministers, and Bertrand. He saw Hortense frequently, and soon after his return called in Dr Corvisart to enquire about Josephine’s illness and last moments. These less formal surroundings made it easier for him to engage the support of people he had previously disdained. He was more affable than in the past, and, according to Hortense, more open, extending a warm welcome to anyone who wished to see him, even to the extent of receiving Sieyès. He expressed his regret at having alienated Germaine de Staël, in the hope that she might rally to him.9

In the course of his march on Paris, aside from the army and former soldiers, those greeting him with the greatest enthusiasm were those most offended by Bourbon rule. From Lyon, where he paused, he had decreed the abolition of the two legislative chambers set up by the Bourbons, proscribed all émigrés who had returned with them, announced the confiscation of lands recovered by them, and voiced phrases about stringing up nobles and priests from lamp-posts. This won him support among former Jacobins and republicans. But galvanising the revolutionary masses flew in the face of his wish and need to keep on his side the nobles and former émigrés whom he had involved in his ‘fusion’, and it also opened up the prospect of a return to the civil war that had ravaged the country before he came to power in 1799. He felt he must enlist the support of all those moderate republicans and constitutional monarchists he had consistently bullied and pushed aside. In order to achieve that, he must bring in a new constitution.

To this end, he invited his former critic Benjamin Constant, who enjoyed a strong following and a Europe-wide reputation as a moderate liberal. Their collaboration was not an easy one; Constant noted that in conversation Napoleon displayed libertarian instincts, yet when it came to the question of power, he stuck to his old views that the only way of getting anything done was through variants of dictatorship. ‘I do not hate liberty,’ Napoleon told him. ‘I brushed it aside when it got in my way, but I understand it, as I was nourished on it.’ Constant was frustrated by his contradictory instincts and the continual swings they produced; Napoleon was still marked by the influence of Rousseau and his admiration for Robespierre.10

He intended the new constitution to derive from the imperial one, in order to ensure continuity and give it what he considered to be a deeper legitimacy. It therefore took the form of an ‘Additional Act’ to it, passed on 23 April. This was a compromise, which had the unfortunate effect of provoking a public debate (liberty of the press had been restored) that opened up the old animosities he had sought to reconcile since 1799. The elections, held in May, satisfied no one. Turnout was little over 40 per cent, and the new hierarchy Napoleon had sought to create with his fusion did not triumph. No more than 20 per cent voted in the plebiscite to endorse the Additional Act.11

Napoleon attempted to galvanise the nation through a ‘Champ de mai’, a version of the Federation of 1790, held on 1 June on the Champ de Mars in front of the École Militaire where he had been a cadet, watched by some 200,000 spectators. It was a ceremony in the mould of the old revolutionary festivals, with a stand for the dignitaries, graded seating for the members of the two chambers and other bodies of state, and an altar of the fatherland. But in attempting to also associate it with ceremonies of allegiance held by Charlemagne and the Capetian kings, he struck a false note. He arrived in a state coach drawn by eight horses, accompanied by his brothers, who, having no constitutional status, appeared as members of a royal family. He had designed fantastic costumes for them; they were decked out in white velvet tunics with lace frills and velvet bonnets surmounted by plumes (Lucien had protested vociferously before agreeing to wear it). Napoleon himself was encased in a similar costume, pink with gold embroidery, so tight he could hardly walk, and weighed down by an ermine-lined purple cloak.

The ceremony opened with a mass, with too many priests, after which Napoleon made a speech in which he hinted that he would recover France’s ‘natural frontiers’, and assured his people that his honour, glory and happiness were synonymous with those of France, enjoining them to make the greatest efforts for the good of the motherland. He then swore to abide by the constitution. A Te Deum was sung, after which he proceeded to distribute eagles to the regiments, and the ceremony ended with a parade, the only part the spectators enjoyed. He had failed to galvanise anyone. ‘It was no longer the Bonaparte of Egypt and Italy, the Napoleon of Austerlitz or even of Moscow!’ noted one observer. ‘His faith in himself had died.’ So had that of the crowd: for every ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ there were ten ‘Vive la Garde Imperiale!’12

On his return to Paris, Napoleon had written to all the monarchs of Europe announcing that he was by the will of the people the new ruler of France, that he accepted the frontiers fixed by the Treaty of Paris of 1814, that he renounced any claims he might have previously made, and that all he wanted was to live in peace. He followed this up with personal letters to Alexander and Francis, and to Marie-Louise, asking her to join him. Hortense, who had been befriended by the tsar when he was in Paris in 1814, also wrote to Alexander supporting Napoleon. Caulaincourt wrote to Metternich assuring him of France’s peaceful intentions. In an attempt to endear himself to the British, Napoleon abolished the slave trade.13

The news of his escape from Elba had sown astonishment and terror among the representatives of the Great Powers gathered at the congress in Vienna. With less than a thousand soldiers, he should have been no match for Louis XVIII’s army of 150,000. But within hours of hearing the news they began mustering their forces: 50,000 Austrians in Italy; 200,000 Austrians, Bavarians, Badenese and Württembergers on the upper Rhine; 150,000 Prussians further north; 100,000 Anglo-Dutch in Belgium; and, on the march from Poland, up to 200,000 Russians. The reappearance of Napoleon had re-established a solidarity which had been fraying in the course of the congress.14

Talleyrand, now foreign minister of Louis XVIII representing France in Vienna, was quick to realise that if Napoleon were to reach Paris and become ruler of France, there would be no legal basis for the Powers to do anything about it, unless he were to make a hostile move. If the allies were to accept this new status quo, Talleyrand’s career would be over. He therefore prepared the text of a declaration which he proposed the plenipotentiaries of the Powers should make, according to which by leaving Elba Napoleon had broken his only legal right to exist, and was therefore an outlaw and fair game for anyone to kill. Metternich and others protested at such a drastic step, but after much heated argument, an amended text was adopted. While it stopped short of sanctioning his murder, it did declare Napoleon to be outside the law, and closed the door to any negotiations.15

Fouché was also a worried man. He had hedged his bets while serving Louis XVIII by setting up a conspiracy among the military to bring Napoleon back from Elba. He had hoped Napoleon would make him foreign minister but accepted the ministry of police, which he would exploit to his own ends. Using his contacts in England, he sounded out the chances of the British cabinet agreeing to leave Napoleon in power, at the same time negotiating asylum for himself were he to need it. He also persuaded his old Jacobin friend Pierre Louis Guingené, now living in Geneva and in close contact with Alexander’s old tutor the philosopher César de la Harpe, to write to the tsar. Guingené had been purged from the Tribunate by Napoleon, but like many like-minded colleagues, he now saw in Napoleon the only hope for France. ‘Oppressed, humiliated, debased by the Bourbons, France has greeted Napoleon as a liberator,’ he wrote to Alexander. ‘Only he can pull it out of the abyss. What other name could one put in place of his? May those of the allies who are most capable of it reflect on this and attempt to address this question in good faith.’16

Fouché had been approached by an agent of a Viennese banking house at the behest of Metternich, who had been growing increasingly alarmed at Russian interference in European affairs and the lack of a reliable ally on the Continent to stand up to it – he had always sought one in France. He did not like war, and was not happy at the prospect of a huge Russian army marching through Central Europe while Austrian forces were engaged in Italy and France. He also knew that Alexander, who had never liked the Bourbons and had grown to despise them, might wish to take the opportunity to replace Napoleon with someone of his own choosing.

The invitation for both sides to meet at an inn in Basel was intercepted, and Napoleon substituted his own agent for Fouché’s. What transpired from this and subsequent meetings was that Austria and Russia might be prepared to treat with Napoleon on condition he abdicate in favour of his son. It might not have been what Napoleon wanted, although it was an opportunity to retrieve something from a venture that was beginning to appear doomed. But Napoleon had learned nothing from his experiences; in this tiny ray of hope he saw great promise, reading into Metternich’s tentative offer a sign of weakness. If the allies were split and no longer felt sure of themselves, then he would not step down and accept humiliating terms, he would play for higher stakes. He therefore cut short the negotiations and resolved to stand firm.17

‘I have been too fond of war, I will fight no more,’ Napoleon said to Pontécoulant on his return from Elba, but the man who had helped launch him on his military career believed he had not changed, and that ‘war was still his dominant passion’. Part of him undoubtedly would have preferred to be left in peace, and he made similar pacific statements to others. He admitted to Benjamin Constant that he had been lured by ambition, but said he now only wanted to lift France from her state of oppression. But war loomed, whether he liked it or not.18

France faced invasion by a formidable array of enemies, which suggested two possible courses of action for Napoleon: either assuming dictatorial powers and using them to regiment the country into an efficient military machine, or harking back to 1792 and calling out the nation in arms. That was something he recoiled from. He trusted in his army, which he liked to believe was as good as ever and burning to fight. This was true of subaltern officers and the older men of the lower ranks, but not at the top. The marshals had not opposed him because they could not be bothered to fight for the Bourbons (only Marmont, Victor and Macdonald followed Louis XVIII into exile). That did not mean they could be bothered to fight for him, particularly in what looked like a lost cause. Typical was Masséna, commanding the region of Marseille, who had not lifted a finger to stop Napoleon but was living in a state of semi-retirement and just wanted to be left in peace. Most of them tried to avoid service, on either side. Much the same was true among the generals and senior officers, who were not wholly committed to Napoleon and merely went with the flow. Even where there was enthusiasm and devotion to Napoleon, there was no longer the dash of youth to support it.19

He also robbed himself of a major asset in not calling on Murat, who had washed up in the south of France at the end of May. Fearing that the allies at the congress in Vienna were going to depose him, Murat had seized the opportunity offered by Napoleon’s escape from Elba to march out and proclaim his intention of uniting Italy, calling on all Italian patriots to join him. Few did, and he was defeated by the Austrians at the beginning of April. He fled to France while Caroline took refuge on a British ship in the bay of Naples, from whose deck she listened to the crowds acclaiming the Bourbons returning from Sicily. Murat had betrayed Napoleon more than once, but at this stage he could do no damage, and his presence on the battlefield would have been a considerable asset.

According to Maret, Napoleon considered two possible plans. ‘One consisted in remaining on the defensive, that is to say letting the enemy invade France and to manoeuvre in such a way as to take advantage of his mistakes. The other was to take the offensive [against the allied armies concentrating] in Belgium and then act as circumstances suggested.’ Maret claimed that Napoleon wanted to adopt the first, but all the civilians invited to express an opinion were opposed to this, warning that the Chamber of Representatives would not support him in it.20

It seems extraordinary that Napoleon should have given way to such pressures, as the first option was clearly the best: by the beginning of June he had over half a million men under arms around the country including the National Guard, and by keeping them close together in a central position he could have brought shattering force to bear on individual armies venturing into France, as he had done in his Italian campaign. There were also weighty political implications to the first option: if the allied invasion of ancient French territory could be represented in the same terms as that of 1792, it might elicit the same patriotic élan, with similar results. Napoleon never tired of representing himself as the beloved of the people. ‘The people, or if you wish the masses, want only me,’ he boasted to Benjamin Constant. ‘I am not only, as has been said, the emperor of the soldiers, I am the emperor of the peasants, the plebeians of France … That is why despite the past, you can see the people gather to me. There is a bond between us.’ This was largely true, certainly of Paris and of central and north-western France.21

It is also possible that, faced with an entirely pacific Napoleon and the prospect of invading a country at peace, the allies might have paused for thought. Their own troops were tired after years of war, and the desire to have a go at the French had been assuaged in the previous year. And if, as some suggested, the people had been called to arms, visions of 1792 might have haunted them too; they were only too aware of the smouldering embers of revolution in France and Europe.

But so was Napoleon, and his memories of 1792 had never left him. He bowed to reasonable counsel. ‘The sensible middle course is never the right one in a crisis,’ remarked General Rumigny, who believed a national call to arms would have revived a revolutionary fervour that would have saved the day. But the mood in the upper echelons of society was not one to build hopes on. After dining at Savary’s house and later calling at Caulaincourt’s on 15 June, Benjamin Constant noted ‘discouragement and a wish for compromise’ wherever he went. ‘Anxiety, fear and discontent were the predominant sentiments; there was no attachment or affection for the government in evidence,’ noted Miot de Melito, adding that only the poorer quarters of the city were firmly behind Napoleon.22

Whether or not he was just putting on a brave face, as Hortense believed, Napoleon was merrier than usual on the day of his departure to join the army, talking of literature during dinner with Letizia, Hortense and his siblings, and saying as he took his leave of General Bertrand’s wife, ‘Well, Madame Bertrand, let’s hope we don’t live to regret the island of Elba!’ Lavalette was also struck by his apparent optimism. ‘I left him at midnight,’ he recalled. ‘He was suffering from severe chest pains, but as he climbed into his carriage he showed a gaiety that suggested he was confident of success.’ But the strategy he had chosen, to take the war to the enemy, doomed him in the long run, as France would not be able to stand up to the vastly superior allied forces in a prolonged war.23

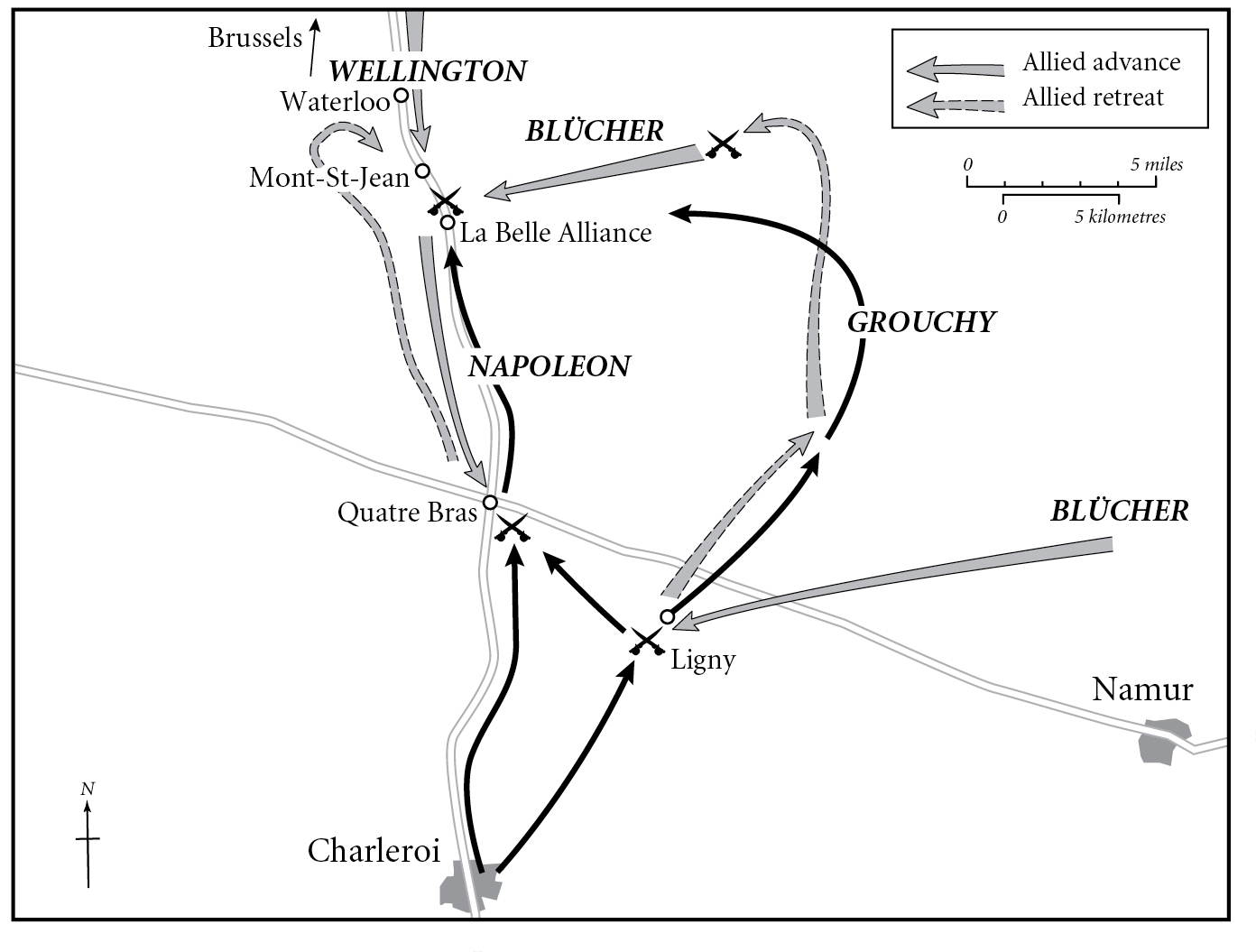

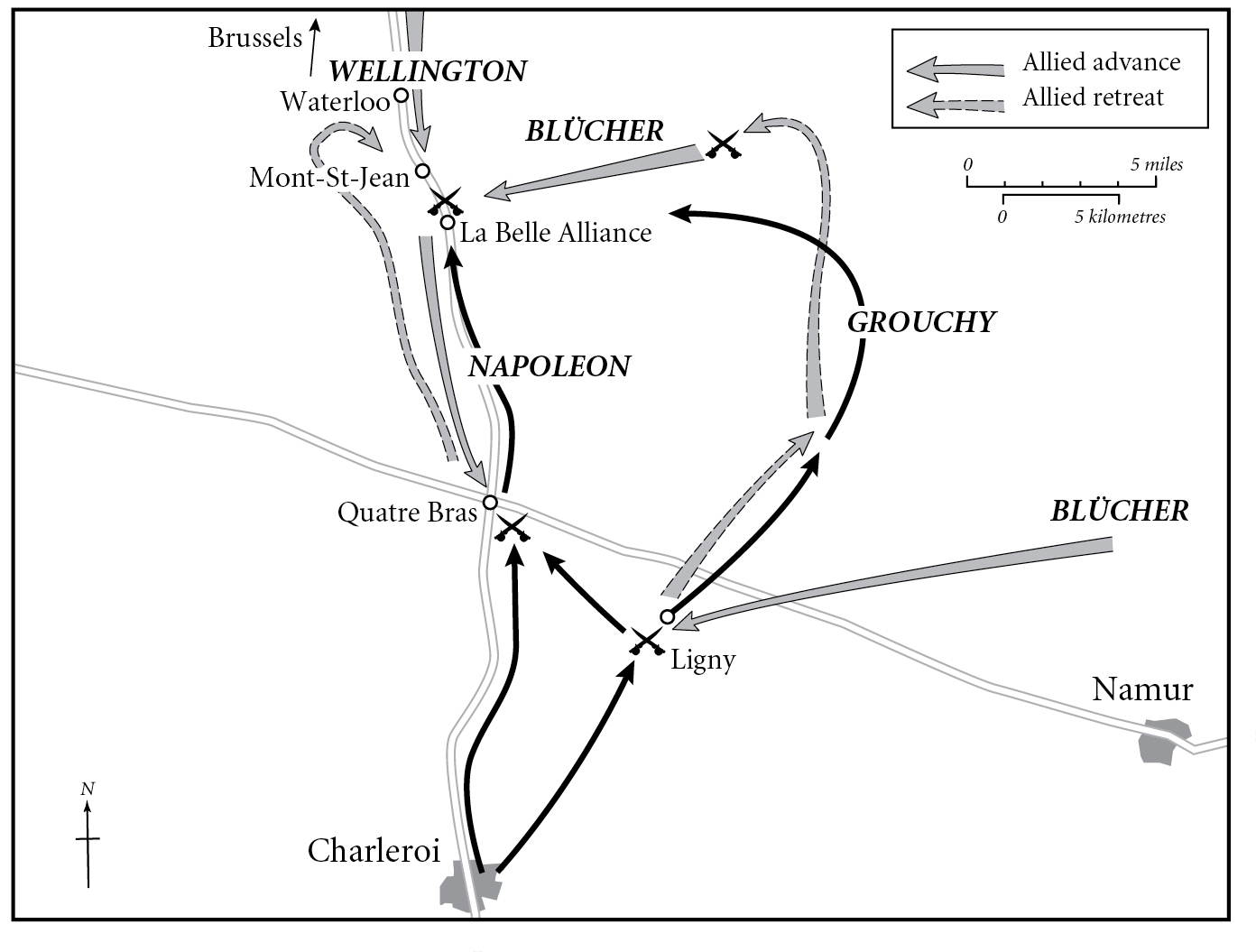

The campaign opened well. Napoleon had some 120,000 men, with which he intended to defeat Blücher with his 125,000 Prussians and Wellington with an Anglo-Dutch force of 100,000 before they could join up and outnumber him. ‘Our regiments are fine and animated by the best spirit,’ Colonel Fantin des Odoards of the 70th Infantry of the Line, a veteran of many campaigns and a survivor of the retreat from Moscow, noted in his diary on 11 June. ‘The Emperor will lead us, so let us hope that we will take a worthy revenge. Forward then, and may God protect France!’24

Napoleon went for Blücher first, and dealt him a heavy blow at Ligny on 16 June. It would have been a rout if General Drouet d’Erlon had acted as Napoleon intended – not the first instance where the absence of Berthier to oversee and check orders were carried out made itself felt. Soult, who was acting as chief of staff, had neither the aptitude nor the authority required. The battle might also have eliminated the Prussians from the scene had it not been for the courtesy of some French cuirassiers who, returning from a charge which had swept over him, found Blücher himself lying helpless, pinned down by his dead horse, which his aide was unable to shift on his own. With soldierly gallantry they refrained from killing him or taking him prisoner.25

Napoleon detached Marshal Grouchy with over 30,000 men to pursue Blücher and make sure he did not veer west to join Wellington. He himself marched north along the road to Brussels, on which, on the next day, Wellington took up position on a slight rise just south of the village of Waterloo, anchored to two heavily fortified farms at Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte. Heavy rain had turned the roads to mud and it took a long time for the French forces to come up. They spent a cheerless, cold night, and on the morning of 18 June the ground was so sodden that it was not possible to go into action, so Napoleon waited till noon for it to dry out.

The younger Napoleon would have tied Wellington down frontally and outflanked him, pinning him in a trap of his own making. But he had long since abandoned such manoeuvres in favour of frontal confrontation and heavy fire. With his forces reduced by detaching Grouchy to around 75,000 men and about 250 guns, he did not have much to spare, and little time, as superior Prussian forces might appear on his right flank at any moment. He meant to pin down the British forces in their strong points of Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte, and to deliver a strong blow at Wellington’s centre. He was unwell and somnolent, and, as at Borodino, did not direct operations actively.

Jérôme, commanding the left wing, wasted time and lives on trying to capture Hougoumont instead of merely neutralising the British forces there. The main attack on the British centre petered out. With some urgency, since Prussian troops were approaching, Napoleon mounted a second assault on Wellington’s positions, to be driven home by a massive cavalry charge. But the attack faltered and the cavalry went into action prematurely, allowing the British infantry to form squares and repel it.

Grouchy had been negligent in his pursuit of Blücher and lost touch with him when the Prussian changed course and moved westward to join Wellington. Instead of marching on the sound of the guns, as some of his generals pleaded with him to do, he carried on, moving away from the battlefield. As a result, Blücher appeared on Napoleon’s right flank and rear in the late afternoon. In a last desperate attempt to break Wellington’s line, Napoleon sent in the Guard, but this was poorly directed and strayed off its prescribed course. Coming under fire from front and flank, it wavered and some units fell back, shaking the morale of the rest of the army, which began a retreat that quickly turned into rout under pressure from swarming Prussian cavalry. As a moonless night fell, the chaos and fear only increased. It was not just a military defeat; it was a morale-shattering humiliation, with standards, guns, supplies and even Napoleon’s famous dormeuse abandoned in the flight.

The roads were so clogged with fleeing troops that he had to make his escape on horseback, riding all night and only stopping the next morning at an inn at Philippeville, where he dictated two letters to Joseph, one for public consumption, the other more honest, and two long Bulletins, one on Ligny, the other on what he called the battle of Mont-Saint-Jean, which made out that it had been hard-fought and was to all intents and purposes won when a moment of panic caused by the retreat of a single unit of the Guard caused a general retreat. It ended with the words: ‘That was the result of the battle of Mont-Saint-Jean, glorious for French arms, yet so fatal.’ He was utterly exhausted, and tears ran down his face, but he tried to sound optimistic. ‘Everything is not lost,’ he wrote to Joseph, since he had received reports that Jérôme and Soult had managed to rally some of the fleeing troops, while Grouchy was retreating in good order to join them, and he urged him to ‘above all, show courage and firmness’.26

He himself was in a state of shock. It had been a bloody encounter – he had lost up to 30,000 men and the allies little short of 25,000. He had also left most of his artillery and a huge number of prisoners on the field and during the flight. The losses were one thing, but the blow to his reputation as a general and to his amour-propre and that of the French army was what really felled him.

He reached Paris around eight o’clock on the morning of 21 June and drove straight to the Elysée, where he was met by Caulaincourt, who was distressed that he had come back, believing he should have stayed with the army; without it, in Paris, he was politically vulnerable. Napoleon ordered a hot bath and summoned his ministers. The first to arrive, while he was still in it, were his paymaster Peyrusse, from whom he wanted to find out how much money was available, and Davout, whom he questioned about troop numbers. Davout assured him that all was not lost if he acted with determination and took the field as soon as possible with a fresh army. But Napoleon was in a state of shock. ‘What a disaster!’ he had exclaimed to Davout. ‘Oh! My God!’ he cried out with ‘an epileptic laugh’ as he greeted Lavalette.27

At ten o’clock he sat down to a meeting with his ministers. He told them that to defend the country from invasion he needed dictatorial powers, but wished to be invested with them by the Chamber of Representatives and the Senate. He had already been informed by the president of the first and by his brothers Joseph and Lucien that news of the disaster at Waterloo had spread, and the mood in the Chamber was defeatist and strongly against him; Lafayette was calling for him to be deposed. Cambacérès, Caulaincourt and Maret urged him to confront the Chambers and make his case, but he bridled at this. Regnaud expressed the opinion that he should immediately abdicate in favour of his son. Davout, Carnot and Lucien advised him strongly to prorogue the Chambers, seize dictatorial powers and declare ‘la patrie en danger’, the battle cry that had galvanised France in 1792. Fouché said there was no need for that, as, he assured them, the Chambers would be only too happy to support him. Decrès stared in astonishment; he, and Savary, knew that to be nonsense, and could see that Fouché was trying to mislead Napoleon. Before giving him the job, Napoleon had told Fouché that he should have had him hanged long ago, but he seemed blind to what his minister of police was up to.28

Formerly so alive to any threat and so quick to see how to snatch a winning card from an unpromising deal, Napoleon appeared curiously detached and incapable of reaction. He would not concentrate on the matter in hand, going over the available troop numbers and the possibility of calling out the levée en masse one moment, asking for reports on the mood of the country the next, blaming people and events, speculating on possible manoeuvres, and confusing his own predicament with an apparently sincere conviction that he was the only person who could save France. ‘It is not a question of myself,’ he said to Benjamin Constant, ‘it is a question of France’; if he were to retire from the scene, France would be lost.29

By midday, Davout felt he had missed his chance and there was no hope left, but the emperor remained calm. ‘Whatever they do, I shall always be the idol of the people and the army,’ he declared on being told the Chambers were now preparing to force him to abdicate or to depose him. ‘I only need to say a word, and they would all be crushed.’ He was right, but he would not say the word. A crowd of workers and soldiers had gathered outside the Élysée, calling for arms, and Napoleon only had to lead them across to the Palais-Bourbon, where Fouché was working for his demise in the Chamber, and the representatives would have been scampering quicker than on 19 Brumaire.30

When various family members called on him that evening, along with Caulaincourt and Maret, they advised him to abdicate. Only Lucien still begged him to act. ‘Where is your firmness?’ he urged him. ‘Cast aside this irresolution. You know the cost of not daring.’ ‘I have dared only too much,’ replied Napoleon, truthfully for once. ‘Too much or too little,’ snapped back Lucien. ‘Dare one last time.’ But he could not overcome his reluctance to unleash civil unrest. ‘I did not come back from Elba in order to flood Paris with blood,’ he said to Benjamin Constant. He continued to dither, and with every hour that passed his chances of saving anything from the debacle diminished. Savary advised him to leave and make a dash for the United States; Napoleon had already summoned the banker Ouvrard to ask him whether he could make sufficient funds available for him in America against a promissory note issued in France. He may also have tried to commit suicide that night; the evidence is patchy, but he was certainly out of sorts when he got up at nine o’clock on the morning of 22 June.31

He had still not made up his mind how to proceed, but by that time a council of ministers and delegates of the two Chambers which had convened that night under the direction of Cambacérès had decided to send a deputation to allied headquarters, effectively sidelining him. Buoyed by news of the numbers of troops Jérôme and Soult had been able to rally and the good spirits of other units around the country, Napoleon started considering various military options. But at eleven o’clock a deputation from the Chamber demanded his abdication. When it had left, he erupted into a rage and declared he would not abdicate, but Regnaud observed that in doing so he might be able to obtain the succession of his son. His advice was endorsed by all the other ministers present except for Carnot and Lucien, who both strongly urged him to seize power, reminding him of Brumaire. But Napoleon no longer had it in him. He dictated to Lucien a ‘Declaration to the people of France’, in which he stated that he had meant to ensure the nation’s independence, counting on the support of all classes, but since the allies had vowed hatred to his person and pledged that they would not harm France, he was willing to sacrifice himself for his country. ‘My political life is finished, and I proclaim my son Emperor of the French, under the name of Napoleon II,’ he declared, going on to delegate powers to his ministers. Carnot wept, Fouché glowed.32

The declaration was delivered to the Chamber of Representatives shortly after midday, and although it was clear that nobody would accept the succession of his son, it was debated at length; Fouché and others still feared that, pushed too far, Napoleon might yet rouse himself and stage a coup. He influenced the choice of the delegates to negotiate with the allies, which alarmed those closest to him, who began to fear for his life; those chosen would not resist handing him over to the enemy as a mark of good faith. It became clear that he must get away to America as quickly as possible.

Napoleon requested Decrès to provide two frigates at Rochefort, and his librarian began preparing cases of books for him to read on the voyage and to help him in the writing of his memoirs. He went through his private papers, burning many, but, curiously, collecting together his youthful writings, including Clisson et Eugénie and the description of his first sexual encounter, in a box which he entrusted to Fesch. He seemed in no hurry to get away. ‘He speaks of his circumstances with surprising calm,’ noted Benjamin Constant, who also came to see him on 24 June. ‘Why should I not stay here?’ he kept saying. ‘What can the foreigners do to an unarmed man? I shall go to Malmaison, where I shall live in retirement, with a few friends who will certainly only come to see me for myself.’ He nevertheless repeated his request to Decrès that a couple of frigates be made ready to take him to America.33

On 25 June he left for Malmaison, going out by a side entrance to avoid the crowd that had been keeping a vigil in front of the Élysée. He would stay there four days, waiting for news that the ships were ready. Decrès replied that he required authorisation from the Commission of Ministers, effectively the provisional government. Under the influence of Fouché this sent General Becker with a contingent of troops to guard Napoleon at Malmaison, where he had been joined by Letizia, Hortense, Lucien and Joseph, Bertrand, Savary, General Lallemand, his aides Montholon and Planat de la Faye, the councillor Las Cases and Caulaincourt. He received visits from old friends, and saw his son by Éléonore de la Plaigne, whom he said he would bring over to America once he was established there. He admitted to Hortense to have been deeply moved by the child.34

The allied armies had paused, checked by smaller but still battle-worthy French forces. Confused informal negotiations were going on between Fouché and Louis XVIII, who was still in Belgium, and between Talleyrand, who had joined him there, and various of his contacts in Paris. The allies were also discussing among themselves whether to reinstate Louis XVIII or install another ruler. Units in various parts of the country continued to fight. Some officers planned to kidnap Napoleon from Malmaison and rally the army to him in order to fight on – there were still 150,000 men under arms around the country, and others would have joined them.35

On 29 June, when he heard that the allied armies were on the move once more, Napoleon offered his services to the provisional government, promising to retire into exile once victory had been achieved. Fouché dismissed the idea, as it had become clear that one of the preconditions of any negotiation was that Napoleon was to be handed over. Not wishing to provoke any violent moves on his part or that of his entourage, the provisional government sent Decrès to Malmaison to inform Napoleon that two frigates were waiting at Rochefort. That same day, after taking his leave of Hortense and others, and pausing for a while in the room in which Josephine had died, he left Malmaison for Rochefort, escorted by Becker and his men.36

The two frigates were ready, but the port was blockaded by the Royal Navy, so there was no possibility of their sailing without a safe-conduct, which Napoleon was assured would be obtained by the government negotiators, a blatant lie; Fouché had let him reach Rochefort, where he was cut off from any support he might have found in Paris, and once he had boarded one of the frigates he was trapped. As he vainly waited for the safe-conduct, he was allowed to visit the island of Aix, next to which his vessel was anchored, and inspect the works he had commissioned; he was cheered by the troops stationed there, but that could not alter the fact that he was effectively a prisoner.

The allies had entered Paris on 7 July, and Napoleon did not relish the idea of being dragged back there as a captive, so the next day he sent Savary and his chamberlain Las Cases over to the British man-of-war blockading the port, HMS Bellerophon. At the same time, a number of plans were discussed for his escape. Joseph found a merchantman which would take him to America incognito, but Napoleon refused this subterfuge, judging it undignified. Captain Maitland, the commander of the Bellerophon, had given Savary and Las Cases to understand that Napoleon would be offered asylum in England, which seemed a more fitting solution. Napoleon wrote the Prince Regent a letter declaring that, trusting in his magnanimity and that of his subjects, he wished, ‘like Themistocles, to come and sit by the fireside of the British people’.37

In the early hours of 15 July he put on his campaign uniform of colonel of the Chasseurs of the Old Guard, and at four o’clock in the morning boarded the French brig l’Épervier, which took him out to within a cannon-shot of HMS Bellerophon and dropped anchor. To Becker, who had suggested escorting him, he replied, ‘No, General Becker, it must not ever be said that France delivered me to the English.’ He drank a cup of coffee and conversed calmly about the technicalities of shipbuilding while a launch came over from the British ship. Madame Bertrand acted as interpreter during the exchange that then took place with the British naval officer, and Napoleon ordered his party to get into the launch. He got in last and sat down. As it pulled away, the crew of the Épervier shouted ‘Vive l’Empereur!’, at which Napoleon scooped up some seawater in his hand and blessed them with it.38

It was 137 days since he had landed in the Golfe Juan, but supporters of the returning Louis XVIII tried to belittle the interlude by referring to the 110 that had elapsed between the king’s evacuation of the Tuileries in March and his return at the beginning of July as a mere ‘hundred days’. As with so much else in his extraordinary life, Napoleonic propaganda turned this into ‘The Hundred Days’, a tragic-glorious chapter in the emperor’s march through history.

He was piped aboard the Bellerophon, and declared to Captain Maitland that he had come to throw himself on the protection of the Prince Regent and the laws of England. The British naval officers had doffed their hats and addressed him as ‘Sire’, as did Admiral Hotham, who sailed up in HMS Superb that day and invited Napoleon to dinner. He felt respected and, ironically, safe as he returned to the Bellerophon, which set sail for England the same day. His Hundred Days in France were over.

As the Bellerophon rounded Ushant on 23 July, Napoleon looked on the land of France for the last time, not yet knowing that Louis XVIII had resumed his place on the throne with a ministry under Fouché and Talleyrand. What he would never know was that on hearing the news Marie-Louise wrote to her father saying that it had caused her great relief, as it put paid to ‘various silly rumours that had been circulating’ – that her son might be made emperor of the French.39