There is some question about whether Winston Churchill ever described Italy as the “soft underbelly” of Axis Europe, but from the autumn of 1942, he certainly saw the country as the most vulnerable part of the occupied continent.

Churchill was confident that fascist Italy would crumble if a direct and strategic attack was mounted by a well-coordinated army, navy and air force. Not all Allied decision-makers were convinced, however. Many doubted the wisdom of invading Sicily, let alone the possibility of continuing the campaign northwards across mainland Italy. High-ranking US military chiefs preferred to conserve resources for a decisive invasion across the English Channel, scheduled for the spring of 1944.

Several convincing arguments were put forward against invading Italy. A mechanized army would be vulnerable to the challenges of central Italy’s mountainous terrain, expending great energies for little to no gain. Moreover, a successful invasion depended on knocking Italy out of the war, and the Germans deciding their ally was not worth defending at all costs. Even if these gambles paid off, the Allies could only hope to achieve a small reward for their pains. Rome was a minor prize for the anticipated loss of human life and manpower, even if it did contain the highly symbolic Vatican City, the holy heart of Catholicism. In addition, an impoverished and hungry Italian population could become an unsustainable drain on the Allies’ limited supply of imported food and fuel.

Churchill, undeterred, was insistent. He believed it was crucial for the Allies to attack southern Europe in order to take control of the Mediterranean. This would enable military and civilian shipping, maintain the momentum of the war by keeping Allied forces in contact with the enemy and, more urgently, draw German forces away from the Eastern Front to relieve pressure on the Red Army.

Eventually, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt was more willing to listen to the British prime minister than to his own advisors. Allied planners at the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943 eventually assented to an invasion of the island of Sicily as a compromise. Whether or not the campaign would continue on to the Italian mainland was left undecided. US General Eisenhower, they directed, would decide on the best policy after the Germans had been driven out of Sicily.

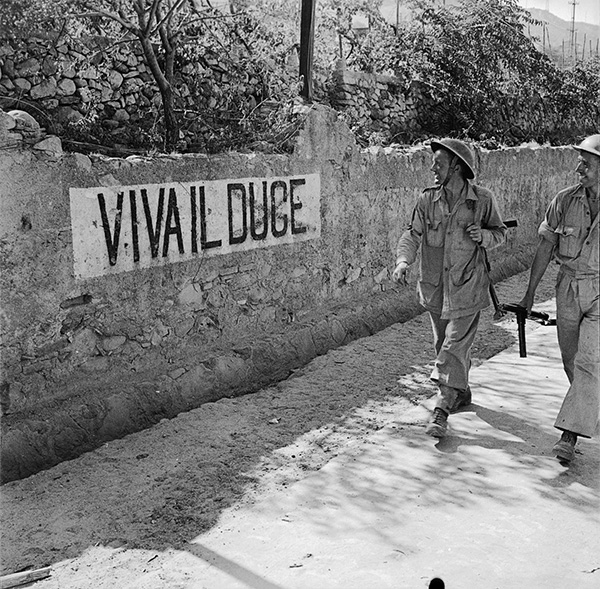

Credit: Getty Images

Italian fascists

In 1943, Italy was ruled by Hitler’s principal ally in Europe, the fellow fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. Mussolini had joined the war only reluctantly halfway through 1940, believing that his country still needed two more years to fully prepare. Nevertheless, Italy’s war aims complemented those of Nazi Germany. Mussolini had pursued a policy of aggressive expansion in southern Europe; without serious opposition, he had occupied the southeast corner of Vichy France, the French island of Corsica, Greece and part of the Balkans. Until his defeat in North Africa in 1943, Mussolini’s goal had been to establish hegemony over the Mediterranean and challenge the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East.

The Italian peninsula and islands were defended not only by the country’s own (large but ill-equipped) army, but also by a great number of German troops. The German troops were under the nominal command of the Italian generals, but in reality they were controlled by German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring from his base in Frascati on the outskirts of Rome.

Although Mussolini had enjoyed absolute power for eleven years, his success was built on his personal charisma, his ruthless use of force and his conquests abroad. By 1943 the Italian leader’s popularity was on the wane, while his political position ultimately depended on retaining the approbation of the king of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III. Hitler himself was unsure whether he could rely on the strength of Mussolini and his Italian allies. As defeat in North Africa approached, Hitler made contingency plans for the defence of Italy in any eventuality. Three new units were created expressly to serve in Italy, and two experienced existing divisions were dispatched from France, some of them crossing the Strait of Messina to reinforce defences in Sicily.

Significant sites

Significant sites are marked on the map

Historical War Museum of the Landings in Sicily 1943, Catania.

Historical War Museum of the Landings in Sicily 1943, Catania.

Preparations for the forthcoming invasion of Sicily, codenamed Husky, had to be swift: maintaining an element of surprise was essential. Given Italy was only one possible military target in the Mediterranean, if the Allies could convince the Germans that their attack was planned elsewhere, they would have the upper hand. An ingenious plan, Operation Mincemeat, was devised to persuade the Germans that even if there were an invasion in Sicily it would be a diversionary campaign, while the main attack would come in Greece or Sardinia. The success of Husky was to be heavily influenced by two factors: how well Sicily was defended, and how well their task forces and armies would perform in the chaos of battle.

The invasion of Sicily in 1943 was, until D-Day eleven months later, the largest amphibious invasion in history.

The ambitious assault on Sicily, codenamed Husky, was the culmination of months of meticulous planning by the leaders of the Allied armies in North Africa. There was much argument about how to go about the task: how many troops would be needed, what their main objectives should be and how air power could best be used in their support.

Eventually it was agreed that a two-pronged offensive would target a number of beaches on Sicily’s southwestern and southeastern coasts. The beaches had been covertly surveyed by submarine teams to make sure they were suitable for the large-scale disembarkation of troops and heavy vehicles. The last great unknowns were how strong the enemy’s defences would prove and how hard the Italians and Germans would fight to retain control of Sicily.

In preparation for the campaign, a massive amount of men and materials had to be assembled, not just for the invasion itself but to sustain a large army in the most impoverished part of Italy for an indefinite period afterwards. Every detail had to be readied, from medals to be awarded in battle to grave markers for the fallen.

Two task forces were assembled in North Africa under the overall command of General Eisenhower. The Western Task Force was essentially the US Seventh Army – commanded by US General George S. Patton – and the Eastern Task Force was the British Eighth Army, including Canadian divisions, led by British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. Each had its respective fleet; altogether around 160,000 men were embarked. Sicily was defended by the Italian Sixth Army, with an estimated strength of over 200,000, supported by around 32,000 German troops.

›› Operation Mincemeat

A successful attack on Sicily depended on keeping German strategists guessing as to where the invasion in the Mediterranean would come. Greece and Sardinia were presumed by German high command to be as likely targets as Italy and Sicily, and Allied planners devised an elaborate deception to disseminate false information. A corpse dressed in the uniform of a Royal Marine major was dropped into the sea and washed up on a beach in Huelva, Spain. Attached to his wrist was a briefcase containing documents that indicated the main attack would be in Greece and Sardinia. Although officially a neutral state in the war, Spain was ruled by the fascist government of General Franco, which was sympathetic to the Axis cause. The Spanish authorities did what they could to authenticate the documents, then shared the information obtained from the “man who never was” with the Germans. It is believed that the incident inspired the young Ian Fleming, then working for British Naval Intelligence, to create stories for his hero, James Bond. The ruse proved successful: the German Abwehr checked the information fed to them by Operation Mincemeat and accepted it as true.

Prior to the invasion, the small Italian islands of Pantelleria, Linosa and Lampedusa were captured without any exchange of fire. Bombing raids were carried out on Sicily’s two main towns, Palermo and Messina, while airborne troops were dropped inland. The operations carried out by these troops, as well as the naval barrage, were highly significant because they marked the start of the European land war.

The main Allied force was transported overnight on 9–10 July 1943 across 150km of open sea between Tunis and Sicily – a journey which takes around ten hours today. The Western and Eastern task forces were assigned different zones of operation: the Americans to the centre of the island and the British and Canadians to the east coast, pushing past Etna to reach Messina.

The landings in Sicily were largely unopposed. On the first day, a 6.5km-deep beachhead was established and four thousand prisoners were captured; several towns were taken in the opening few hours alone. The Germans staged a counterattack against the Americans at Gela, however, and tenaciously held on to the fortifications they had established in the east. Communication failures, errors and incidents of friendly fire also caused much loss of life. In particular, airborne assaults using parachutes and gliders proved ineffective and costly in fatalities.

The campaign to overcome the island’s defenders ran into difficulty at several other points, especially on the east coast. Things were not helped by a tense rivalry between Patton and Montgomery, which hindered cooperation and made it hard to co-ordinate troops. The plain of Catania and the surrounding hills proved a particularly bloody battlefield, and a strong German defensive line was established around the volcano of Etna.

While Montgomery slogged up the east coast, Patton headed north to take Palermo (against light opposition), next turning east to try and reach Messina before the British. Although Patton reached Messina first, his troops were too late to prevent the Germans from evacuating their remaining forces to fight another day.

›› Friendly fire

The inadvertent bombing, shelling and shooting of an army’s own troops was – and still is – a perennial fact of war. Poor planning, bad weather, faulty information, lax identity checks and general human error were the cause of countless catastrophes during World War II, although the number of injuries and fatalities sustained by friendly fire remains unknown.

There were several instances of friendly fire in the Italian campaign. During the invasion of Sicily, panicking American ground forces – believing they were being attacked – shot down 23 of their own planes and killed at least 81 paratroopers dropped in as reinforcements. Later, inland from Anzio, American Warhawk planes closed in on the wrong targets. They strafed and bombed their own soldiers, killed and wounding more than one hundred men. The survivors were then pummelled for an additional ten minutes by their own artillery.

By the time the campaign was completed on 17 August after 39 days of fighting, more than 5500 Allied soldiers and 9000 Axis combatants had lost their lives. The Allies were mostly greeted as liberators rather than invaders, but as the new occupying force of Sicily, they soon found themselves with problems that would be repeated all over a newly liberated Europe. There was the pressing question of how to deal with civilians who had cooperated with the fascist authorities; another issue was getting Allied troops to treat the local populations with respect.

The invasion of Sicily had important consequences in Rome, as its planners would later claim they’d hoped. While bloody battles were being fought in Sicily, a palace coup d’état in Rome forced Mussolini from power. The new government resolved to secretly negotiate a peace with the Allies, and its prime minister, Pietro Badoglio, opened discussions to this effect. After a pause in fighting, the Allies made their first tentative landfall on mainland Italy on the morning of 3 September 1943. The same afternoon saw the fruition of a long series of negotiations, and an armistice was signed between the two sides at a military camp near Cassibile, on Sicily’s east coast.

The US Seventh Army landed three divisions on beaches in the Gulf of Gela: at Scoglitti, Gela and Licata. Some of the first troops sent ashore were Italian-Americans, who proved invaluable during the build-up and implementation of Operation Husky. These men supplemented military intelligence with personal recollections and were able to communicate with the locals and help stabilize the newly liberated Italian territories.

Along the coast today – from Porta Aurea at the Valley of the Temples to the streets of Vittoria, through Licata and Gela – you can see a number of surviving military structures including bunkers, strongholds, trenches and pillboxes. Several sombre plaques record mostly individual deaths of combatants, while there are two war monuments in the town of Gela itself.

The 82nd Airborne Division of the US Army faced determined opposition at Ponte Dirillo on the night of 10 July, where they were heavily outnumbered by the German and Italian troops and their tanks. This monument, a large stone tablet located near Gela on the way to Punta Secca, commemorates the 39 paratroopers who died in battle.

There are three Italian war cemeteries on Sicily. Besides this one in Agrigento, two others are located at Catania and Acireale on the east coast. Between them, they contain the graves of more than four thousand soldiers who died defending the island.

In the prelude to Operation Husky, Sicily’s capital was badly bombed, but to little end. Palermo was a more symbolic than useful prize, and the US Seventh Army, who advanced from its landing beaches to take the city, met minimal opposition. Nevertheless, the assault provided useful publicity and a welcome boost to morale. General Patton occupied the grand Palazzo Reale for a few days while he prepared his advance on Messina.

One of the fiercest battles of the Sicily campaign was fought for control of the small inland town of Troina between 31 July and 6 August 1943. Many inhabitants survived in squalor in the crypt of the cathedral; the scenes of horror and destruction that greeted the US liberators would be repeated in countless towns all the way up the Italian peninsula. The end of the battle marked the breaching of the Etna defensive line, but the Germans managed to make an orderly retreat from Troina before the arrival of the US troops.

The British Eighth Army was assigned a series of beaches on the Gulf of Noto, south of Siracusa. Canadian forces came ashore on the west side of the Pachino peninsula; the rest of the Eighth Army landed on stretches between the tips of the Pachino and Maddelena peninsulas. A few memorials stand sentinel in and around Pachino, and at one beach, Fontane Bianche, there’s a modern holiday resort.

A plaque next to the church in Cassibile records the signing of the Italian armistice in a military camp near town on 3 September 1943, which brought hostilities with the Allies to an end. Preliminary negotiations were undertaken in Lisbon, but the terms were finalized here in Cassibile, with future British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan playing an important role in the process. The document was signed by Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, and Giuseppe Castellano, on behalf of King Victor Emmanuel III and Italian Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio. The armistice and its terms were kept secret for five days as the Italians bought time to prepare for the German backlash. The delay also allowed the Allies to continue planning their invasion of mainland Italy without alerting the Germans to the Italian surrender.

›› Crossing the tracks

Italy changed sides in World War II not for moral reasons but pragmatic ones. It hoped to be siding with the winners, who might do less damage to the country than their erstwhile friends, the Germans. The Allies treated the Italians with a mixture of indifference and distain: the years of fascism and collaboration with Hitler were not easily forgiven or forgotten.

Switching sides mid-war was a risk that had harsh consequences for Italy. Most ordinary Italians thought the September armistice meant peace – that the Germans would take it as a signal to withdraw from their country – but that was not the policy issuing from Berlin. In fact, the Germans expected the Italians to surrender. They had long regarded them as duplicitous allies and had made plans accordingly. Overnight, Italian land north of the shifting front line became occupied. German paratroopers entered Rome at the same time as the king and Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio fled the capital.

Having been given no instructions from its government, the Italian military found itself at the mercy of the Wehrmacht. Soldiers who supported Mussolini and fascism were welcomed into the German ranks; all the others were faced with the choice of resisting attempts to disarm them, deserting to join the partisans or accepting their fate. More than 250,000 Italian soldiers were taken prisoner by the Germans and sent to labour camps in central Europe, along with 50,000 Allied prisoners of war. Huge quantities of weapons and vehicles were impounded, although the Italian navy managed to evade capture. The Italian soldiers who chose to fight back – an estimated 20,000 – were massacred by the same combat forces they had been fighting alongside just days before. Italian troops abroad in Greece and the Balkans were treated even more harshly. Around five thousand of them surrendered to their captors and were executed in cold blood. Only on 13 October 1943, too late to be of much use, did the Italian government declare war on Nazi Germany and join the subsequent battles using what manpower and weaponry remained.

Despite the cost, the change of sides meant Italy could recover some of its national self-respect. The partisan movement that flourished in occupied northern Italy would help lay the foundations for the new Italian republic at the end of the war.

British and Canadian forces made their landings in the southeast corner of the island, between Pachino and Siracusa, now the site of a Commonwealth cemetery. The majority of burials belong to men killed during the landings or in the early stages of the campaign – including members of the airborne units that attempted to land west of the town on the night of 9–10 July, when gale-force winds forced sixty of the 140 gliders into the sea and blew others well wide of their objectives. Altogether there are 1059 graves, 134 of them belonging to unidentified personnel.

Credit: Getty Images

Benito Mussolini, known to his followers as Il Duce (the Leader), was the world’s first fascist dictator. He came to power in Italy in 1922, while his admirer and imitator Adolf Hitler was still building his power base in Bavaria.

Born into a poor family in Romagna in 1883, Mussolini served in World War I (Italy on that occasion being on the side of the Allies) before becoming a journalist. One of his contemporaries described him as an “orator of the pen”, and he naturally understood the power of the media to convey state propaganda.

During the 1930s, Mussolini pursued an aggressive but pragmatic foreign policy, with the aim of making Italy the dominant power in the Mediterranean. He had some initial success in expanding the Italian empire to include Italian East Africa and Italian North Africa, and gave assistance to Franco’s rebel forces in the Spanish Civil War. Mussolini is said to have had great personal magnetism, and a capacity for getting things done. An oft-cited quote claims that Mussolini “made the trains run on time”, although he frequently used violence to achieve his political objectives.

In 1937, Mussolini allied himself with Germany and Japan, and it was he who coined the term “Axis powers”. But when World War II broke out in 1939, he was reluctant to commit, believing that Italy would not be ready for combat until at least 1942. Nevertheless, on 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on Britain and occupied a corner of the soon-to-be-defeated France.

War meant a struggle to retain Italian possessions in North Africa against an Allied army that landed on the coast of Morocco in November 1942 and fought its way eastwards, finally forcing the Italo-German army – cornered in Tunisia – to surrender. Despite being defeated in North Africa, Mussolini’s position still looked unassailable on 9 July 1943. “I am like the beasts”, he declared, “I smell the weather before it changes. If I submit to my instincts, I never err.”

The invasion of Sicily, however, tested the Italian nationalism he had nurtured for twenty years to breaking point. His grip on power, and the loyalty of the king and the political class, were less sure than he believed. Ultimately, Mussolini’s personal fate was to be decided by the success or failure of the Sicily campaign.

Credit: Alamy

Agira Canadian War Cemetery

Despite its mouthful of a name, this museum does a good job of explaining the Sicily campaign, from the beach landings to the battles that allowed the Allies to take the island. Located near the railway station in Catania, it houses a range of evocative displays in a repurposed industrial building.

Exhibits include uniforms, weapons, photographs, video footage and projections of the island’s devastated towns, in particular Catania, Palermo and Messina. There are also wax statues of Roosevelt, Churchill, King Victor Emmanuel III, Mussolini and Hitler; a reproduction of the tent at Cassibile in which the armistice was signed on 3 September 1943; and a simulator that gives visitors the eerie sensation of living through an air raid.

The museum also functions as a library and research centre, collating books and papers (published and unpublished) about the Sicily campaign, including local resources and eyewitness accounts recorded by Sicilian civilians.

A total of 4561 German military personnel, killed in action in various parts of the island, are buried here. The poignant cemetery is designed like a building, with different rooms representing the different parts of the island where these men fell.

Agira was taken by the 1st Canadian Division on 28 July 1943. The site for this war cemetery was chosen a couple of months later for the burial of all Canadians – a total of 484 – killed in the Sicily campaign. It’s permanently open to visitors who want to pay their respects, although the steeply terraced site makes wheelchair access difficult.

Messina was heavily bombed in the prelude to the invasion of Sicily. The closest island town to the Italian mainland, Messina was a strategic objective for the Allies, who hoped to reach it before the Germans and Italians could evacuate their troops. In the event, the Axis evacuation went ahead virtually unhindered.

Allied hopes were running high after the conquest of Sicily. Italy had been politically destabilized and its government had entered into secret negotiations with the Allies with a view to surrender.

It was assumed that since the Germans had been forced into retreat in Sicily they would not make a determined stand for mainland Italy. Rome was expected to fall within weeks, and the Germans to be driven out of the country with comparative ease. Allied commanders knew they had to press home their advantage and move stealthily northwards. They needed to land sufficient forces on the mainland; keep them on the move; and keep them supplied.

Operation Baytown and the armistice

The invasion of mainland Italy began auspiciously, with a landing (codenamed Baytown) that met almost no opposition. On the morning of 3 September 1943, a contingent of the British Eighth Army crossed the Strait of Messina and landed at Reggio di Calabria. Again, there was little resistance: Italian troops were demoralized by the loss of Sicily and the uncertain political situation after the fall of Mussolini. The German commander Kesselring, meanwhile, had decide not to commit his forces in Calabria in open battle. His strategy would be to slow the Allied advance by blowing bridges and reinforcing established defensive lines further north.

That same afternoon, an armistice was signed between the Allies and the Italian government, a capitulation that was kept secret for the next five days while the Italians prepared for the reaction of Germany and the Allies continued strategizing. Since the fall of Mussolini, the Germans had suspected that the Italians were about to renege on their alliance, even though the new prime minister, Badoglio, assured them that it held firm. On 8 September, the news of the armistice was announced. Hitler had just returned to his headquarters at Rastenburg after his final visit to Russia. He awoke from his afternoon nap to the news that the Italian government had made peace with the Allies.

Credit: Getty Images

Allied troops in Italy in 1943, having embarked as part of Operation Baytown

The armistice had dire consequences for Italy. The broadcasted news spread confusion among the Italian armies, who were not given any firm instructions except to cease hostilities with the Allies. Rome was occupied by German troops and the royal family and government fled east, finally taking refuge in Brindisi.

Operation Avalanche at Salerno

In order to maintain their northern progress, the Allies needed to take Naples. Its port would be crucial for importing the vast quantity of supplies necessary to sustain an army on campaign. In the early morning of 9 September 1943, an Allied invasion fleet landed near Salerno, south of Naples, as part of Operation Avalanche. The invasion force, under the command of US General Mark Clark, comprised the US Fifth Army, the 82nd Airborne Division and the British X Corps.

The landings met unexpectedly fierce resistance from the German army. The Allies managed to land and secure a 55km broad beachfront, but on 12 September the German Tenth Army counterattacked the bridgehead; it was barely held. The German counteroffensive led to heavy casualties and, at points, reached the beaches.

For a few critical days there was talk of halting the operation and evacuating the troops. It was hoped that Field Marshal Montgomery would arrive to ease the situation, but advancing slowly from the south, he was too far away to lend assistance until Operation Avalanche had already tipped in favour of the invaders. The German counterattack ultimately failed – mainly because Hitler refused to allow Kesselring to deploy more troops – and on 16 September the tide of battle turned and the German forces withdrew north.

While the battle of Salerno was being decided, so was the fate of the deposed and imprisoned dictator Benito Mussolini, who was being held in the Hotel Campo Imperatore in the Apennines. He was freed in a daring raid carried out by German paratroopers and commandos on 12 September and flown out of the country. Two days later, German forces were allowed to evacuate the island of Sardinia by the Italian garrison, while a small US force landed to notionally liberate the island.

To maintain some semblance of normality in northern Italy, on 23 September Hitler installed Mussolini as the head of a puppet government, officially the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (Italian Social Republic), but universally known as the Salò Republic, after the town on Lake Garda.

Naples was finally taken on 1 October 1943, giving the Allies a working port. Allied forces continued to press north towards Rome, but their progress was halted by a series of defensive lines established by the Germans. The southernmost of these was the Volturno Line, which ran from Termoli along the Biferno river and through the Apennines to the Volturno river in the west; it was breached on 12 October. The following day, Badoglio’s government formally declared war on its old ally, Nazi Germany.

During Operation Avalanche, the Allied army landed on beaches along the Gulf of Salerno from Maiori on the Sorrento peninsula to Agropoli in the south. Most troops embarked on beaches – distinguished and labelled by colour – along the Sele River plain. The British landed north of the river mouth, near Magazzeno, and the Americans near Paestum, to the south.

In town, the Museum of the Salerno Landings (Museo dello Sbarco, Via General Clark 5, salerno1943-1944.com) tells the story of Operation Avalanche through a variety of displays, including unedited video footage, flags, uniforms and weapons. Outside the museum, more substantial military hardware takes the form of two restored Italian anti-aircraft guns and a Sherman tank.

A Commonwealth cemetery lies on the road from Salerno to Eboli.

Museum of Operation Avalanche (MOA)

Via Sant’Antonio 5, Eboli, ![]() moamuseum.it

moamuseum.it

The central feature of the MOA, housed in a fine 15th-century building, is the “Emotional Room”, which screens two moving projections. One film shows historical footage narrated by three distinguished personalities: photojournalist Robert Capa, novelist and war correspondent John Steinbeck, and Jack Belden, a war correspondent who landed with the troops at Salerno. The second screen projects images onto a 3D topographical map.

Campagna Internment Camp Museum

Via San Bartolomeo, Campagna, ![]() museomemoriapalatucci.it

museomemoriapalatucci.it

The Campagna Internment Camp was created in 1940 by the Mussolini government to house foreign Jews fleeing from persecution in Germany, Austria and Poland, and many others who “threatened” the regime. It was never a concentration camp, and only ever held a small population of inmates, reaching just over two hundred at its maximum. When the Allies invaded southern Italy, locals liberated the camp.

Viale Giulio Douhet 2/a, Caserta, ![]() reggiadicaserta.beniculturali.it

reggiadicaserta.beniculturali.it

For the greater part of the Italian campaign, the spectacular Royal Palace at Caserta served as headquarters for the Allied armies. The 2nd General Hospital was also located in town from late 1943 until September 1945. Some of the 768 people buried in the cemetery at Caserta died in the hospital, others as prisoners of war before the Allied invasion (there was a POW hospital at Caserta, too).

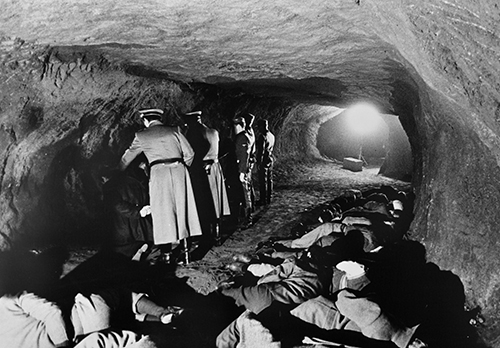

Piazza San Gaetano 68, Naples, ![]() napolisotteranea.org

napolisotteranea.org

The atmospheric complex of tunnels excavated 40m beneath the centre of Naples was begun by the Romans. Many of its passageways were used as air-raid shelters during World War II, and today’s Bourbon Gallery contains a good museum where wartime graffiti can still be seen.

Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line

The US Fifth Army left Naples in early October 1943 and moved steadily north. Its commander, General Mark Clark, was confident that Rome would be taken before the end of the month.

Allied planners in Italy, however, had misread the intentions of Kesselring. They believed that the Germans would put up just token resistance in central Italy, before pulling back to defend its north. Instead, the commander of the German forces fought doggedly, understanding that the mountainous topography of the Italian peninsula favoured the defender. During one battle, the American war correspondent John Gunther observed that “both sides are tired, and whereas we are exposed in the plain, the Germans are high up, with good cover.” This diagnosis could be reliably applied to almost any Italian confrontation between the Allied and Axis forces over the next year and a half. Kesselring’s strategy was to dig in along a series of defensive lines, observing the enemy from altitude and using direct artillery, mortar and machine gun fire to slow the vulnerable attacking troops. In this way, he sought to delay the enemy advance for as long as possible. If his army was forced to retreat, they would simply fall back on the next line of defence. Retreating German troops destroyed bridges and laid mines and booby traps across the roads and paths to hinder the advancing Allies.

The defences along the Volturno river were breached on 12 October. The next defensive line, the Barbara Line, was crossed with relative ease on 2 November, and a month later the US Fifth Army reached the formidable Winter Line that stretched across Italy from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic coast. The Winter Line was a series of three lines, including the Bernhardt Line bulging to the south and the Hitler Line, which arced to the north. The most important part of the Winter Line, however, was the Gustav Line, which stretched for 161km from the River Garigliano in the west to the Sangro in the east. It centred on the ancient Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino.

To approach the Winter Line, fierce battles were fought in December 1943 for possession of San Pietro Infine and Monte Lungo. Crossing the Rapido river proved impossible, and the Allied advance was stalled beneath the formidable abbey of Monte Cassino, standing a lofty 520m above sea level. An initial attempt by the Allies to take possession of the monastery (launched on 17 January and 11 February 1944) was driven back with heavy losses. It was hoped that an amphibious landing at Anzio would unblock the stalemate at Monte Cassino, but this too was unsuccessful. Allied problems were only compounded by the harsh Italian winter.

As early February brought no relief, Allied commanders settled on a radical solution. On 15 February, the abbey was all but obliterated by bombs dropped from US airforce B-17 flying fortresses, killing a large number of civilians sheltering within its walls. The Allies later claimed – and perhaps they really believed – that the Germans were using the abbey as an observation post, but this has been strenuously denied. Another theory is that the Allies were working on faulty intelligence due to the mistranslation of an intercepted radio message. What is certain, however, is that the bombing was counterproductive: the ruins of the abbey provided perfect cover for the German defenders of Monte Cassino when the second frontal assault was launched against them on 16–18 February. A third battle for Monte Cassino was conducted on 15–23 March, again without success for the Allies.

The fourth and final battle for Monte Cassino began on 11 May, codenamed Operation Diadem, reinforced by troops from the British Eighth Army brought in from the Adriatic coast. Finally, the Germans retreated from the Gustav Line on 25 May 1944, and the abbey ruins were overrun by victorious Allied (Polish) troops.

After five months of stalemate, the road to Rome lay open, but the costs were high. It is estimated that the Allies (fielding Australian, Canadian, Free French, Moroccan, Italian, Indian, New Zealand, Polish, South African, British and American troops) suffered around 55,000 casualties; Germany and its ally, the Italian Social Republic, about 20,000.

Credit: iStock

Monte Cassino Abbey today

Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line sites

Via Montecassino, Cassino, ![]() abbaziamontecassino.org

abbaziamontecassino.org

The abbey of Monte Cassino was founded by Saint Benedict around the year 529, from where its monks spread the word as far away as Britain and Scandinavia. At the start of 1944 the monastery was one of the great medieval buildings of Italy, exquisitely decorated and filled with religious treasures.

Between 17 January and 18 May 1944, Monte Cassino was the scene of unrelenting combat. Lying in a protected historic zone, the abbey itself had been left unoccupied by the Germans, although several Allied commanders believed the abbey was being used as an artillery observation point by the German forces. Despite a lack of clear evidence, the monastery was marked for destruction and on 15 February American bombers reduced the abbey and the entire top of Monte Cassino to a smoking mass of rubble. German officers had already transferred some 1400 precious manuscripts, paintings and other items from the abbey to the Vatican, saving them from the blast.

The destruction of the abbey was one of the greatest military blunders of World War II. Around 230 Italian civilians who had sought refuge in the monastery were tragically killed, while the destruction did nothing to alleviate the Allies’ problems. German paratroopers duly occupied the ruins, which provided them with excellent defensive cover.

After the war, the abbey was rebuilt exactly as it was. Today, it’s occupied by a monastic community that welcomes both pilgrims and visitors, as well as housing a small museum and video projection explaining the bombing.

Credit: iStock

Monte Cassino Polish Military Cemetery

Only fully completed in 1963, the Polish Military Cemetery at Monte Cassino was officially inaugurated on 1 September 1945, exactly six years after the German invasion of Poland. It takes the shape of an amphitheatre, with an altar and a large cross in the middle of the lawn. At the entrance, a gatepost bears the inscription “For our freedom and yours, we soldiers of Poland gave our soul to god, our life to the soil of Italy and our hearts to Poland.’’

The cemetery holds the graves of 1052 soldiers of the Polish II Corps who died in the battle of Monte Cassino. After the war, the Corps’ Commander General Władysław Anders, like many of his soldiers, lived in exile from communist Poland. When he died in London in 1970, he was buried in Monte Cassino according to his will. The Corps was predominantly a Polish unit, but also included Belarusians and Ukrainians. The men had various religious affiliations: most were Catholics, others were Jews and some Eastern Orthodox Christians. The men’s religious diversity is reflected on the headstones.

On 18 May 1944, a platoon of the 1st Squadron of the 12th Regiment of the Podolski Lancers were the first troops to enter the ruins of Monte Cassino Abbey. The German defenders were driven from their positions, but at a high cost. The Corps suffered heavy casualties during the Italian campaign: 2301 killed, 8543 wounded and 535 missing.

Palazzo de Utris, Venafro, ![]() winterlinevenafro.it

winterlinevenafro.it

A small museum in Venafro, created by members of the Winter Line association, brings the Winter Line to life with displays of uniforms, weapons, ammunition and photography. The living conditions of both soldiers and civilians are vividly illustrated.

The Battle of Monte Lungo, also called the Battle of San Pietro Infine, took place between 8–16 December 1943. It was the first engagement of the reconstituted Royal Italian Army following Italy’s change of sides in the war.

A new Italian brigade, the First Motorized Group, was attached to the US Fifth Army. Highly spirited but poorly armed, the unit bore the heavy responsibility of redeeming the military honour of the Italian Army. Its troops were ordered to conquer Monte Lungo during the Allied offensive in San Pietro Valley, a mountain occupied by the German 15th Panzer Grenadier Division and blocking the Allies’ path. On 8 December 1943, the Italian brigade advanced, together with units of the US II Corps, under cover of the morning mist. As soon as the mist lifted, however, the advancing soldiers were exposed, and the Germans had a clear field of fire. The Italians suffered heavy casualties and the attack was repulsed. A repeat attack on 16 December was better prepared, supported by heavy artillery bombardments, and the peak was conquered by the US and Italian forces.

The current military shrine contains the graves of 974 Italian soldiers killed in battle. Opposite the cemetery, a fine museum exhibits objects related to the role played by the Italian troops in the liberation of their country.

In late 1943, the village of San Pietro Infine was completely destroyed by fighting between the advancing US forces – who sought to break the Winter Line – and the defending German troops. The Historical Memory Park, a designated national monument, contains the ruins of the village as they stood at the end of the war. It’s an atmospheric place, a ghost town which provided the backdrop for several scenes in Mario Monicelli’s 1959 film The Great War. A new village was built 3km from the original site.

To break the stalemate at Monte Cassino on the Gustav Line, Allied commanders decided to open a second front behind the German positions. Operation Shingle was to be an amphibious landing at Anzio, 62km south of Rome.

If the offensive at Anzio went well, the German defenders of the Gustav Line would be outflanked and forced to retreat, the US Fifth Army would be able to break through the Gustav Line, and Rome would quickly fall.

The invasion force of Operation Shingle consisted of 40,000 soldiers and 5000 vehicles under the command of US Major General John P. Lucas. His army landed at three locations: the British Force 9.7km north of Anzio (Peter Beach), the Northwestern US Force at the port of Anzio (Yellow Beach) and the Southwestern US Force attacked near Nettuno, almost 10km east of Anzio (X-Ray Beach). The initial landing on 22 January 1944 met little resistance, but Lucas delayed moving inland immediately to prevent his forces being overextended. Instead, he consolidated his position, but in doing so allowed the German forces to organize their defence. Scattered among the surrounding hills, German artillery units had a clear view of every Allied position.

Credit: iStock

Statue of brothers in arms at Sicily-Rome American Cemetery

For many weeks, a rain of shells fell on the Allied bridgehead and the harbour of Anzio. Far from relieving Monte Cassino, the invasion force was pinned down, and became in need of relief itself. A frustrated Churchill commented, “I had hoped we were hurling a wildcat into the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale.”

On 22 February Lucas was replaced by General Truscott, and both sides reinforced their armies; Italian troops still loyal to the Axis were deployed by the German army. Despite spirited efforts, the Axis forces were unable to push the Allies back into the sea, but neither did the Allies manage to penetrate inland. The stalemate at Anzio ended on 18 May when the Allies broke through the German line at Monte Cassino.

Inevitably, Anzio – and its surrounding area – is a place of cemeteries. The Sicily-Rome American Cemetery at Nettuno (abmc.gov) is one of only two US cemeteries in Italy. The majority of the soldiers buried here died in the liberation of Sicily; in the landings at Salerno and the fighting as the Fifth Army made its way northward; and in the landings at Anzio Beach and the expansion of the beachhead. Further graves contain airmen and sailors. The wider complex includes a cenotaph, memorial, map room, pool, peristyle and a chapel with the names of 3095 men declared missing in action. The on-site visitor centre tells the personal stories of combatants as well as showing films, photographs and a number of interesting interactive displays.

Credit: Getty Images

Piana delle Orme Historical Museum

At Anzio itself there are two Commonwealth cemeteries. The larger is the Beach Head Cemetery, north of Anzio town, which contains 2316 graves, 291 of unknown soldiers. It is a place awash with colour: roses, pansies and impatiens grow in front of the tombstones and arbours of wisteria and jasmine flank the pathways.

Via di Villa Adele, Anzio, ![]() sbarcodianzio.it

sbarcodianzio.it

Opened in 1994 for the 50th anniversary of the landing, Anzio Beachhead Museum is invaluable for understanding what happened at Anzio. It comprises four sections, divided into American, British, German and Italian sectors. Displays feature authentic uniforms, badges, documents, pictures and other artefacts donated by veterans' organizations.

Piana delle Orme Historical Museum

Via Migliara 43, Latina, ![]() pianadelleorme.com

pianadelleorme.com

Two pavilions at the Piana delle Orme Historical Museum are entirely devoted to the display of military vehicles from World War II. Dioramas depict how Italy became involved in the war, the course of the North African campaigns, the amphibious landing of the Allied troops near Anzio and the battle for Monte Cassino.

After the Anzio campaign, US General Mark Clark had two options. His superior, British General Harold Alexander, ordered him to capture as many Germans retreating from the Gustav Line as possible. But Clark had his sights on Rome.

Clark’s decision to turn directly towards the capital, rather than to strike a crippling blow to the Germans, is as controversial today as it was then. Did he pass up an opportunity to shorten the Italian campaign in order to win a blaze of glory for himself? Or was he driven by Roosevelt’s intimation that Rome must be conquered by American troops? Regardless of his motivations, by moving on Rome, Clark allowed the German Tenth Army to escape and continue its defence of northern Italy.

On 4 June 1944, Rome became the first capital to be liberated from Nazi Germany. It had already been declared an open city and was captured without any loss of life – a welcome relief after the heavy-fought campaign of Cassino. Italian forces fighting alongside the Allied armies were sent to the Adriatic front, meaning they could not participate in the liberation of their capital.

During the 1930s, Pope Pius XI devised a policy intended to condemn the barbarous acts of fascism without exposing the Catholic clergy to danger. This did not always work. In a number of countries, in particular Poland, many priests were brutally murdered by the Nazis.

Throughout the war the Church tried to exercise its spiritual authority without the temporal power to back it up. The Vatican City was treated as a neutral state by both Axis and Allied commanders, and the Nazis deliberately avoided it when they occupied the rest of Rome. But the German occupation, from September 1943, brought the Holocaust closer to home. Italian Jews were deported en masse to concentration camps, even if some were given sanctuary in the monasteries and convents of Rome.

Pope Pius XII, Pius XI’s successor, emerged from the Liberation as a figure of national Italian unity – in contrast to the king who was tainted by his collaboration with Mussolini. Since the war, critics have accused the Pope of not doing enough to prevent the evils of the Holocaust, but even they concede that the Vatican’s room for manoeuvre was limited. What the Pope failed to publicly denounce was balanced by private acts of admirable religious leadership.

Rome was psychologically and symbolically important to the Allies. Aside from being of tremendous propaganda value, it was hoped that taking the city might draw German troops away from France and the impending D-Day landings – an event that would overshadow the conquest of Rome just two days later.

Historical Museum of the Liberation

Via Tasso 145, ![]() museoliberazione.it

museoliberazione.it

During the Nazi occupation of Rome (11 September 1943–4 June 1944), this museum building functioned as an SS police station under the overall command of Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Kappler. Innumerable unfortunates were brought, many without cause, to be interrogated, detained and tortured. From the station, the only onward destination was Regina Coeli prison; extended captivity in Germany; deportation to another country; or execution at Fort Bravetta. It is estimated that at least 1500 men and more than 350 women passed through during the occupation, some of them partisans, others ordinary citizens. The museum brings together relics, documents and photographs, as well as thoughtful works of art. It has a particularly good collection of underground posters and flyers printed surreptitiously during the occupation.

Credit: iStock

Villa Torlonia

Rome War Cemetery lies on Via Nicola Zabaglia, within the Aurelian Walls of the ancient city of Rome. It is reached from the Piazza Venezia, the centre of Rome, by taking the Via dei Fori Imperiali down past the Colosseum and along the Viale Aventino as far as the Porta San Paolo. It lies next to the Protestant Cemetery in which Keats and Shelley are buried.

The war cemetery contains 426 graves, mainly those of the occupying garrison; a few belong to the dead brought in from the surrounding countryside. Some soldiers and airmen who died as prisoners of war in Rome are also buried here.

Via Nomentana 70, ![]() museivillatorlonia.it

museivillatorlonia.it

Mussolini’s former residence, Villa Torlonia, is now a complex of three buildings. The main one, the Casino Nobile, has a bomb- and gas-proof shelter built on the orders of Il Duce. A film recounts the history of the villa, including Mussolini’s time spent here before his dramatic arrest in July 1943.

Credit: Getty Images

Nazis carry out the Fosse Ardeatine massacre

The Monte Mario French cemetery is located on Via dei Casali di Santo Spirito on the highest hill of the city (but not one of the legendary hills), rising above the right bank of the Tiber. It contains 1709 tombs of men from the French Expeditionary Corps killed between Rome and Sienna. Most of the graves – of which there are 1142 – belong to Muslim soldiers who served in the French army.

Via Ardeatina 174, ![]() mausoleofosseardeatine.it

mausoleofosseardeatine.it

On 23 March 1944, Italian partisans placed a bomb on Via Rasella, on the route taken by a column of Italian policemen who had volunteered to serve with the SS. German Colonel Kappler, chief of police in Rome, requested permission from his superiors to carry out a reprisal for the attack; this was authorized by Adolf Hitler himself, who stipulated that ten civilians must be killed for each dead policeman within 24 hours. Kappler secretly emptied the jails of men, both condemned and detained, adding Jewish and Italian civilians to reach the required number of 335 – a figure hiked up by a mistake in counting. The men were taken to the tunnels of an old quarry and made to kneel beside the growing pile of corpses. Each was shot in the back of the head to conserve bullets. After the massacre, the Germans blew up the entrance of the Ardeatine quarry to cover their tracks, and most families were told nothing about the fate of their loved ones. It was only after the liberation of Rome that the massacre was discovered; the tragedy is now commemorated by a national mausoleum and museum.

Hotel Relais 6, Via Tolmino 6, ![]() 2museumrome.eu/4

2museumrome.eu/4

This private museum in the Hotel Relais 6 (relais6.com) boasts a good collection of memorabilia connected with the liberation of Rome, including a jeep, motorbike, uniforms and a great many everyday military and civilian items from 1944.

From Salerno, Bernard Montgomery’s three British Eighth Army divisions crossed the country to the eastern, Adriatic coast to join up with troops that had landed at the port of Taranto on 9 September 1943.

The first task of Montgomery’s men was to capture the airfields of Foggia, which would provide important forward bases for bombing raids into northern Europe. A successful amphibious raid liberated Termoli at the end of the Volturno defensive line on 3 October, allowing Montgomery’s forces to continue up the Adriatic coast. His aim was to take Pescara, enabling his troops to traverse the country from east to west via Avezzano to approach Rome. This plan proved over-optimistic.

After crossing the Sangro river with relative ease, Montgomery’s advance was halted before Ortona at the Moro river, where Canadian troops were sent into action, with great loss of life trying to cross the final ravine. Ortona itself was only taken after two days of house-to-house fighting – the Germans eventually pulled out and the town was captured on 28 December 1943.

Montgomery’s progress was not helped by a surprise German bombing raid on the port of Bari on 2 December, which disabled the port for almost three months. Among the ships sunk was one loaded with mustard gas bombs that the Allies had brought to Italy in case the Germans resorted to chemical warfare. In late December, Montgomery called a halt to the campaign, to be resumed in spring. He flew back to Britain to participate in preparations for D-Day and was replaced by Lieutenant General Oliver Leese.

Credit: Getty Images

Allied soldiers in Italy

Credit: Alamy

Canadian infantrymen preparing an attack near Ortona, 1943

After the passing of winter, the Eighth Army’s advance continued up the Adriatic coast. It was weakened by the transfer of troops and materials to Cassino and to the new offensive in France. However, the port of Ancona was taken after three days of battle (16–18 June 1944) by Polish II Corps. Further north, the British came to the eastern end of the Gothic Line, which was stormed under Operation Olive on 17–21 September, during which Rimini was captured. At the end of the year, in December 1944, Ravenna also fell to the Eighth Army before it paused to overwinter at Faenza.

Ortona was almost completely destroyed in the battle that took place here between 21 and 28 December 1943.

Anyone interested in Canada’s role in the Italian campaign should visit the Museum of the Battle of Ortona on Corso Garibaldi. Its informative exhibits display memorabilia, photos and war relics, including personal effects of the soldiers. To the south of the town is the Moro River Canadian Cemetery, which contains 1615 graves of men who died during the fighting at Moro river and Ortona – and during the weeks of action that preceded and followed it. In December 1943 alone, the 1st Canadian Division suffered more than five hundred casualties.

Montecchio village, near the eastern end of the Gothic Line, was practically razed to the ground during the war and the surrounding countryside was badly damaged. One of the line’s anti-tank ditches ran through the valley immediately below Montecchio cemetery. The site, which contains 582 plots, was selected by the Canadian Corps for burials during the fighting to break through the Gothic Line in the autumn of 1944.

Via S Aquilina 58, Rimini, ![]() museoaviazione.com

museoaviazione.com

This indoor and outdoor museum located southwest of Rimini explores the history of military aviation, with an emphasis on World War II. A number of planes are displayed, along with anti-aircraft weapons and other flying equipment.

Despite the overshadowing events of D-Day, once Rome was secured the US Fifth Army made its way northwards towards Tuscany.

Two days after the liberation of Rome, Allied commanders delivered their coup de grâce: a massive landing of forces on the beaches of France that would open a western front in Europe. This reduced the Italian campaign to secondary importance in Allied strategy. From D-Day onwards, the Italian battlefields were mostly seen as a way to lure German forces away from France and the Eastern Front, weakening opposition to the main campaign from Normandy to Berlin. Germany was expected to cede the rest of the Italian peninsula without much fight. The US Fifth Army travelled northwards up the west of Italy through Tuscany, while the British Eighth Army was committed in Italy’s centre and eastern, Adriatic coast.

The Germans made their first stand after being driven north from Rome at Bolsena. To the east of Lake Bolsena, a tank battle was fought in June 1944 between the 6th South African Armoured Division and the Hermann Goering Panzer Division. The next line of German defences centred on Lake Trasimene, adjacent to Perugia (which was liberated on 20 June). Cortona, north of the lake, was entered on 6 July, the day after Siena (Sienna) had been liberated by Free French forces.

A further German stand at Arezzo in early July 1944 resulted in a dogged struggle before the town was taken on 16 July by the 6th Armoured Division, with the aid of the 2nd New Zealand Division.

Credit: Getty Images

M7 Priest selfpropelled gun on the Gothic Line in 1944

On the coast, the port of Livorno (once known as Leghorn in English) was liberated on 19 July 1944, but not before the departing Germans had blown up its ancient lighthouse. Pisa was liberated on 2 September by the Fifth Army, and Lucca on 5 September. Florence (Firenze), meanwhile, was attained and liberated on 11 August. Behind the German lines, Italian partisans were increasingly active, incurring great risk to themselves and their communities. Members of the Resistance and the wider civilian population were frequently subject to gruesome reprisals.

The Allied advance was checked by the formidable defences of the Gothic Line, renamed as the less grandiose Green Line in June 1944 to allay Hitler’s fear that the Allies, if they broke through, would use its name to accent their glories. The Gothic Line was a row of fortifications that ran through the hills north of Florence from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic. When it prevented the Allied advance in October 1944, a strategy of “offensive defence” was adopted – the Allies would pause to overwinter until the weather cleared and a spring offensive could be organized. This strategy was disrupted in December, when a last offensive was launched by the German army and troops of Mussolini’s Italian Social Republic. The Battle of Garfagnana (officially Operation Winter Storm or Unternehmen Wintergewitter) took place near Massa and Lucca; Barga was briefly captured by the Germans but as quickly lost again. The episode nevertheless provided a morale boost for Italian soldiers fighting with the Germans, and was promptly utilized for propaganda purposes.

Credit: Liberation Route Europe

History enthusiasts visit remains of the Gothic Line

On 18 June 1944, nine German soldiers entered the recreational club of the village of Civitella, where they were challenged by local partisans. Two Germans were killed in the ensuing confrontation. The villagers pleaded with the German authorities against reprisals, but on 29 June a detachment of paratroopers from the Hermann Goering division – young men, many trained by the Hitler Youth movement – was dispatched to Civitella to exact revenge. The local priest offered his life if others could be spared, but the paratroopers dragged all the men of the village out of their houses and shot them. In total, 149 people were killed, including two priests; the Germans then set fire to Civitella. Massacres were also carried out in fourteen nearby villages.

Florence American Cemetery and Memorial

Tavarnuzze, ![]() Abmc.gov

Abmc.gov

The Florence American Cemetery, located about 7.5km from Florence near Tavarnuzze, is one of only two American cemeteries in Italy (the other being at Anzio), covering 28 hectares of wooded hills. A bridge leads from the entrance to the main cemetery area, where 4399 headstones are arranged in symmetrically curving rows on the hillside. Most men buried here died in fighting between Rome and the Alps from June 1944 onwards, especially in the Apennines. Above the graves, on the uppermost of the three broad terraces, a memorial is crowned by a large sculptured figure. The memorial’s two open atria (courtyards) are connected by the Tablets of the Missing, which carry 1409 names. On the southern court is a chapel decorated with fine marble and mosaics; the northern atrium has operations maps (also in marble) showing the movements of the American armed forces in Tuscany and northern Italy. There is also a Commonwealth cemetery near Florence.

Sant’Anna di Stazzema, ![]() santannadistazzema.org

santannadistazzema.org

On 12 August 1944, troops of the Waffen-SS, assisted by Italian fascists of the Black Brigades, killed 560 people in this Tuscan hill village to punish the civilian population for supporting the Resistance. The massacre is remembered as one of the defining events in the Italian struggle for liberation. In fact, it helped set the political tone of Italy after the war; the new republic would be founded on the struggles of the partisan movement and the German attempts to suppress it. The village now has a national peace park, founded in 2000, while the restored church can also be visited.

The Gothic Line ran just south of this village, some 20km north of Lucca, where you’ll find multiple examples of excellently preserved military fortifications. Visible bunkers, tank walls and trenches all remain (almost) intact. The town’s handsome medieval bridge also survived the war and can be admired still.

Via di Cantagallo 250, Prato, ![]() museodelladeportazione.it

museodelladeportazione.it

The workers of Prato who were deported to Mauthausen and Ebensee concentration camps in Austria are honoured in this museum, where the exhibits prove that even the most everyday objects can be significant: clothes, posters and photographs speak of life, survival and death in the camps. Prato’s labourers – arrested following a general strike in March 1944 – joined Jews, homosexuals, Roma, the disabled and political opponents of the Nazis at the camps. Some were killed on arrival, others were literally worked to death.

Futa Pass, ![]() voksbund.de

voksbund.de

The largest German war cemetery in Italy stands near a pass on the Apennines on what was once the Gothic Line. It contains a staggering 30,683 graves.

The Allies had hoped to take Bologna before the end of 1944, but the Germans were able to hold the Italian front stable over winter in the Apennines, along the Gothic Line. It was only in the spring of 1945 that the Allies were able to resume their campaign.

To both sides, the outcome of an Allied victory in Italy seemed inevitable – it was just a question of time, and how many soldiers and civilians would die, before peace was declared. By early 1945, General Heinrich von Vietinghoff realized that German defeat was imminent. His troop losses were too great and he was no longer receiving supplies of arms and ammunition from Germany. Vietinghoff began to think of how the war in Italy might be concluded in as favourable way as possible for himself and his armies. In February, on his behalf, SS Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff began secret negotiations with US diplomat Allen Dulles with a view to arranging an armistice. This contravened the terms agreed at Casablanca – that only an unconditional surrender by German forces would be acceptable – and risked offending Stalin, who was not included in the talks or even consulted.

Credit: Getty Images

Massed American M10 tanks fire at a German position near Bologna

While negotiations were still underway, Operation Grapeshot, the final offensive of the war in Italy, was launched on 6 April 1945. Bologna was heavily bombed in preparation for the Allied ground forces, who approached the city from the south and east. US and Italian troops entered Bologna on 21 April, forcing the German army to retreat northwards, where its route was cut off by the Po river. The Allies had destroyed the bridge crossings and the German troops were compelled to improvise ways across, leaving their vehicles and heavy weapons behind.

›› The Italian Civil War and the partisan republics

While World War II was drawing slowly towards its conclusion in 1944–5, a war within a war was being waged in Italy. Bands of partisans (partigani) fought bravely against Italian fascists (the notorious Brigate Nere or Black Brigades) and the German army.

The partisans were organized into autonomous groups, armed with whatever weapons they could find. Among them were communists, socialists, anarchists, liberals, fugitives from the Italian army and sundry foreigners on the run from the authorities. Others simply described themselves as patriots hoping to build a better Italy after the war. All they had in common was their battle-song, Bella Ciao, which has since come to represent resistance to all forms of oppression in international popular culture.

The partisans' guerrilla tactics made it hard for the security forces of the German army and the Salò Republic to engage them, so they often chose to punish sabotage by massacring ad hoc groups of civilians instead. This did not prevent the resistance movements of northern Italy from proclaiming a succession of transitory mini-states, called partisan republics. None of the twenty states established was bigger than a valley or a district. They tended to last between a couple of days and a few months before the German occupying forces systematically destroyed them.

Italy’s partisans took the initiative to declare 25 April 1945 a day of general insurrection, and this date is still celebrated as Italy’s Day of National Liberation. The cities of northern Italy quickly fell, taken either by Allied forces or liberated “internally” by partisans, some a mixture of the two. Genova (Genoa) was liberated on 25 April; Turin (Torino) and Verona on 26 April; and Milan (Milano) on 28 April. Mussolini and his mistress were captured on 27 April, spelling the end of the Italian Social Republic, and were executed the following day.

By now, the war was being lost on all fronts, and Berlin was close to surrender. German high command was determined to conclude a single peace with the Allies, but Vietinghoff defied instructions and flew south to the Royal Palace of Caserta, where he signed an unconditional instrument of capitulation with the Allied victors. The war in Italy ended at 2pm on 2 May 1945, when almost one million German and Italian troops officially surrendered to Field Marshal Harold Alexander.

Bologna and northern Italy sites

Via Sant’Isaia 20, Bologna, ![]() museodellaresistenzadibologna.it

museodellaresistenzadibologna.it

This excellent museum explores the aims and methods of the diverse Italian partisan movements (see above), which played a vital role in attacking the occupying Germans behind their lines. Resistance fighters used underground passageways to move around the city of Bologna; the tunnels can be visited by guided tour.

Memorial Museum for Liberty Bologna

Via G. Dozza 24, Bologna, ![]() museomemoriale.com

museomemoriale.com

A narrative route through five scenes leads visitors through the events of the latter part of the Italian campaign, beginning with the round-up of civilians to build the fortifications of the Gothic Line. The bombings and daily lives of civilians are both explained, and exhibits include tanks, trucks, jeeps and a chilling railway wagon used for deporting Jews.

Marzabotto, ![]() montesole.org

montesole.org

During the summer of 1944, tension among the German occupiers of Italy increased. The Allies were advancing slowly from the south and incessant attacks were initiated by partisans hiding in the woods and mountains of the Apennines and the Apuan Alps. Units of the Waffen-SS took revenge on the civilian population in order to discourage the Resistance. The largest single massacre carried out by the Waffen-SS in western Europe took place in Marzabotto on 29 September 1944. The specific number of victims is disputed, but the generally accepted figure is 770 casualties, 150 of them children. The site is now a memorial park with a chapel.

›› The fate of Mussolini

Benito Mussolini was immediately arrested by the Italian government after his fall from power in July 1943. He was freed from captivity in a bold raid by German paratroopers shortly after the armistice, and established as the leader of a fascist government in German-occupied northern Italy, known as the Salò Republic. As the Allies advanced northwards, Mussolini’s authority waned. On 27 April 1945, he and his mistress Claretta Petacci were captured by Italian partisans while trying to escape to Switzerland; they were executed the next day outside a villa near the shores of Lake Como. Their corpses were taken to Milan where they were defiled by the mob and hung above the forecourt of a petrol station. Adolf Hitler was gravely affected by the way in which Mussolini had been humiliated after his death, and resolved to take his own life and have his body destroyed.

Museum of the Second World War and the River Po

Piazza Municipio, Felonica, ![]() museofelonica.it

museofelonica.it

Unlike most war museums in Italy, this one tells a story not of battle, but of ignominious retreat. As German and Italian Social Republic troops withdrew northwards from the Apennines and Emilia Romagna, their way was blocked by the broad sweep of the mighty River Po.

The Allies had destroyed the bridges across the river, limiting the German escape routes, while the overwhelming supremacy of Anglo-American aviation forced the retreating troops to move almost exclusively at night, hiding in woods and buildings during the day. Numerous fires and high columns of smoke rose above the southern bank of the River Po between 20 and 24 April 1945. Lucky soldiers were transported to the opposite bank on the few ferries and boats available; others swam or made use of anything that would float: air chambers extracted from the wheels of vehicles, water tanks and barrels, wooden planks and even laundry tubs. Heavy weapons and equipment that could not be carried across had to be abandoned or destroyed. All this and more is explained using a variety of fascinating photographs and objects.

Museum of the Montefiorino Republic and of the Italian Resistance Movement

Via Rocca 1, Montefiorino, ![]() resistenzamontefiorino.it

resistenzamontefiorino.it

Italy’s resistance movements went further than carrying out acts of sabotage: a scattering of mini-states were set up by partisan groups in liberated corners of northern Italy. There were twenty “partisan republics”, which existed for brief periods from two days to a few months before the Wehrmacht arrived to reincorporate them into Mussolini’s puppet state, the Italian Social Republic. The Republic of Montefiorino, whose story is told in this medieval castle using documents, photographs and objects, survived for just 45 days from June to August 1944.

International Primo Levi Studies Centre

Via del Carmine 13, Turin, ![]() primolevi.it

primolevi.it

Jewish writer and chemist Primo Levi’s moving personal account of the Holocaust and the Liberation, If This is a Man, was published in 1947. Levi formed a partisan group in 1943 but was captured and sent by cattle wagon to Auschwitz. Of the 650 people in his group of deportees, he was one of only thirty who survived the war. This centre is dedicated not only to his memories but also to his thoughtful reflections on war, peace and human behaviour.

›› Trieste

The Adriatic port-city of Trieste became part of the Salò Republic in September 1943, but was directly controlled by the Germans who installed a concentration camp with a crematorium here, the Risiera di San Sabba (now a museum; risierasansabba.it). During the Liberation, Trieste became a potential flashpoint of east-west confrontation. Marshal Tito’s Yugoslav partisans occupied the city from 1 May to 12 June 1945, during which time anti-communist Italians and Slovenian refugees were murdered – some of them simply disappearing. Eventually, Tito reached an agreement with British Field Marshal Harold Alexander, Supreme Commander of Allied forces in the Mediterranean. Trieste and its hinterland were temporarily partitioned into two zones of influence: one under Allied control in the west and the other under Yugoslav jurisdiction in the east. The 1947 Treaty of Paris created the Free Territory of Trieste, but the city was later returned to Italy and the eastern zone incorporated into Yugoslavia (and subsequently divided between Slovenia and Croatia).

Central Railway Station, Milan, ![]() memorialeshoah.it

memorialeshoah.it

The word “indifferenza” (“indifference”) is spelled out in huge letters along a wall of Milan’s memorial to the Holocaust, a stark reminder of fascism’s greatest ally. Twenty trains of livestock cars pulled out of Milan station between 1943 and 1945 loaded with Jews and other “undesirables”, few of whom were ever to return. Some of the rolling stock used in the transports is on display today.

For anyone living in a modern democracy in the 21st century, it is hard to imagine what life was like under foreign occupation in the 1940s.

Occupation can seem inconceivable to citizens of countries like Britain, the USA and Australia, who have never shared a land border with an aggressive and dominant neighbouring state. Even for most of continental Europe in the late 1930s, the idea that their autonomous nations could be overrun by the armies of Nazi Germany and administered from Berlin seemed unthinkable. Some countries were convinced that they would be protected by their longstanding declarations of neutrality – a strategy that worked for Switzerland and Sweden but not for Norway, Denmark or the Low Countries. Other nations – notably France – felt safe because of the size and power of their armies, and the presumed strength of their frontier defences.

Credit: Getty Images

French café life under Nazi occupation

The map of Europe changed rapidly between 1939 and 1940, in the space of just a year. Territorial expansion was central to the ideologies of both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. They extended their borders by means of stealth and manipulation, or – more commonly – by force. As a result, the once autonomous nations of Albania, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway and Poland all had to adapt to life under indefinite occupation.

France was occupied by both Germany and Italy, the latter seizing the southeastern corner of Provence. The Channel Islands, dependencies of the British Crown off the coast of Normandy, also fell to, and were administered by, the Nazis. The Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia had a more complicated experience, being occupied initially by the Soviet Union, which also invaded eastern Poland in 1939. In late 1943, Italy went from being an occupying country to an occupied one. Having changed sides in October, Italy was unable to prevent its north from coming under German control.

German occupation took many forms, and its severity depended on how the Nazis regarded the country in question. The Nazis saw the Slavs as an inferior people, and the occupation of Poland was harsher than that of France – a country they admired for its sophisticated culture.

Some territories were regarded in Nazi ideology as rightful parts of Germany to be reincorporated into the Reich, rather than foreign lands to be seized. Austria, Alsace and German-speaking parts of Belgium, Poland and Czechoslovakia were simply being “freed” to rejoin the Fatherland to which they linguistically and culturally belonged. Their experience of “occupation” was therefore less severe – or even almost non-existent – although their young men were conscripted into the Wehrmacht. In “freed” areas of Poland, ethnic Poles were murdered, brutally expelled or ruthlessly Germanized.

In all cases, occupation was dictated on the conqueror’s terms. Its essence in the German military mindset was vae victis or “woe to the conquered”. Nazi rule was not cooperative or consultative; the strong dictated their terms to the weak and defeated, and they were non-negotiable. Occupation was ultimately directed by Hitler’s military needs, and resources from Germany’s acquired territories were exploited to pay for the war effort and the cost of occupation.

Credit: Getty Images

Refugees walking in the street

Occupation was particularly disastrous for the Jews – as well as several other targeted minorities. Many Jews had escaped from Germany only to find themselves subject to anti-Jewish policies in Nazi-occupied territories such as the Netherlands or Belgium. Under occupation, local authorities and police were expected to round up Jews and dispatch them to the death camps. In Poland, ninety percent of the prewar Jewish population (three million people) was herded into ghettos and camps – and later killed.

Rather than administering conquered territories directly from Berlin, Nazi Germany generally favoured installing puppet regimes. The Vichy government under Marshal Pétain controlled the majority of France, while the Salò Republic was Mussolini’s nominal government of northern Italy after the Allied invasion. Regions that were deemed of vital strategic importance – such as the coasts of France and the Low Countries – were placed under the direct jurisdiction of the Wehrmacht.

Defence apart, the main objective of the occupiers was to keep a territory functioning. Agricultural and industrial production were to meet the needs of the German war machine, the railways had to facilitate troop movements, and the subject population must remain compliant in defeat.

In certain regions of occupied Europe, life went on much as before, altered by a number of moderate inconveniences and hardships. For others, life was unrecognizably different.

Poland suffered in a way that people in the west were spared. Subject to enforced work programmes and Germanization, the Slavs were regarded as expendable slave labour. Six million Poles – half of them Polish Jews – died as a result of the war, a staggering twenty percent of the population.

A defining experience of all defeated populations was a feeling of powerlessness. The conquered people of Europe were expected to follow Nazi orders. Punishment for disobedience was summary and disproportionate: those who resisted Nazi will were branded criminals and terrorists. The same charge was applied to anyone assisting the resistance or providing safe houses for fugitive Allied airmen. The jails of the Gestapo became overcrowded and executions were carried out as a warning to anyone who dared to defy the occupation authorities.

People faced with life under occupation responded in a number of ways. Some – politicians like de Gaulle and many Polish soldiers and airmen – went into exile to continue the fight from outside the country. Others, typically direct victims of Nazi persecution (Jews, Roma, homosexuals and so on), were forced to go into hiding; this was the decision of Anne Frank and her family. Many more chose to resist. An assortment of people helped collect intelligence for the Allies, provide food and shelter for those in hiding and organize strikes and acts of sabotage. Others took to the woods and hills to fight the Germans using whatever weapons they could obtain.

Credit: Getty Images

Nazi police confiscate goods from the house of a Polish Jew