By 1943, the British had reasons to be optimistic. In October 1942 they had achieved their first land victory over the Germans at the Second Battle of El Alamein, when the Eighth Army forced German Field Marshal Rommel’s elite Afrika Korps out of Egypt.

The victory at El Alamein was followed by the first joint Anglo-American campaign, Operation Torch: a large-scale attack on French Morocco and Algeria. Torch provided invaluable experience in how to organize a large amphibious landing and highlighted some of the problems involved when national armies fought together, such as failures of cooperation and the tendency for top generals to compete with each other. Despite some serious setbacks, the North Africa campaign ended in Allied victory, with the last Axis troops finally surrendering on 13 May 1943.

Credit: Getty images

General Dwight D. Eisenhower addresses paratroopers in England

Though agreement had been reached at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 and at the Washington (Trident) Conference the following May, the British were still nervous about invading German-occupied France, preferring an Italian campaign to follow the action in Sicily. Nevertheless, a team led by Lieutenant General Morgan was already drawing up plans for the French invasion. Presented in July 1943, they identified three Normandy beaches as the best landing sites, rather than Pas-de-Calais (opposite Dover), which would have seemed more obvious. Wherever they chose to land in France, Allied troops would have the challenging task of breaching the massive German coastal defences, known as the Atlantic Wall, which stretched all the way from Norway to Spain.

At the Tehran Conference in December 1943 – the first meeting of Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin – the Soviet leader agreed to an eastern offensive to coincide with the promised Anglo-American western offensive in order to stretch the German resources to the limit. Shortly afterwards, General Eisenhower was appointed Commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Setting up his headquarters in London, Eisenhower selected a team of mostly British senior officers to help him refine General Morgan’s original plan: Air Chief Marshal Tedder became his deputy; General Montgomery was to command the invading land forces; Admiral Ramsay the naval forces; and Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory the air force. Among the changes to the plan were increasing the invasion area to five beaches between Cherbourg and Caen, and changing the date from 1 May to early June to allow more landing craft to be assembled and more time for Allied bombers to destroy German supply links – roads and railways – in northern France.

Significant sites

Significant sites are marked on the map

Imperial War Museum London, London.

Imperial War Museum London, London.

Planning discussions for the invasion (codenamed Operation Overlord) and the amphibious landings (Operation Neptune) were rarely straightforward, and there were major disagreements. Eisenhower threatened to resign unless given full control of all three armed forces, something that RAF Bomber Command, supported by Churchill, tried to resist. Since June 1943 British and American planes had been subjecting German industrial sites and cities to round-the-clock heavy bombing, a strategy that the head of Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, and his US counterpart General Carl Spaatz, believed would ultimately win the war. When Eisenhower, Montgomery and Tedder requested the bombing of French transport systems to prevent rapid deployment of German reinforcements (the Transportation Plan), Harris, Spaatz and Churchill argued against it. In the end, Eisenhower won out and the pre-invasion bombing took place. Although the raids proved effective, they caused substantial civilian casualties.

On 5 March 1944, General Eisenhower moved his headquarters from Grosvenor Square to Bushy Park in southwest London, partly to avoid the “mini-Blitz” that had hit Central London. He continued to shuttle back and forth to liaise with his commanders and Churchill. According to his naval aide Harry C. Butcher, he also visited around twenty divisions, twenty airfields and four US Navy ships in morale-boosting inspections, often accompanied by Churchill.

Churchill and his chief military adviser General Alan Brooke were particularly nervous about opening a second front in France because of the failed Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942, an operation aimed at destroying German defences near the eponymous port in Northern France. It involved around 5000 Canadians – keen to see action – 1000 British, and 50 US Rangers. The ground troops were supported by 237 ships, none larger than a destroyer, and 74 squadrons of aircraft, most of which were fighter planes rather than bombers.

The raid ended in disaster. Reconnaissance had failed to reveal the German gun emplacements on the cliffs and many of the troops never succeeded in getting off the beaches. The Royal Regiment of Canada suffered particularly heavy losses, several tanks got stuck in the shingle, and those that did cross the sea wall made little impact. Some commandos managed to reach their targets but were ultimately forced back; withdrawal began just five hours after the raid had begun. The only positive was that all subsequent amphibious landings were prepared with much greater attention to detail.

American troops had been coming to Britain since 1942, and in the run-up to D-Day numbered around 1.5 million. Most arrived at the port in Liverpool. As well as living in vast camps, many soldiers were billeted in people’s homes and a degree of culture shock was inevitable. GIs were issued with a pamphlet, Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain, with tips such as “Don’t Be a Show Off. The British dislike bragging”. This huge input of US manpower was essential for the success of Overlord; ongoing campaigns in Italy and the Far East meant the British were running low on troops. All soldiers had to be extremely fit – an infantryman might need to carry as much as half his weight in equipment – and they were subjected to a punishing training regime.

In the months before D-Day, several rehearsal exercises for the amphibious landings were organized. Slapton Sands in South Devon was used for the larger of these because of its resemblance to the Normandy beaches. On 28 April, one such exercise, codenamed Tiger, ended in disaster when eight LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) filled with troops heading inland were attacked by nine German E-boats (Motor Torpedo boats) with the loss of around 750 US servicemen. The tragedy, which was hushed up for security reasons, did not prevent the even larger Exercise Fabius taking place one week later at several beaches along the south coast, including Slapton Sands. This was a dress rehearsal for Operation Neptune, which ran a whole week and involved 25,000 troops.

Transporting over 130,000 troops and their equipment – including heavy tanks – across the English Channel, then providing them with sufficient supplies to maintain their effectiveness, was always going to be an enormous challenge. It was a task that many of the best military and scientific brains had been working on for years. Nearly seven thousand ships would be involved, with landing ships and landing craft making up over half of them. Landing craft varied in size according to function – from the enormous LSTs to the smaller British LCAs (Landing Craft, Assault) and the American LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel). The latter two were mostly made from steel-armoured wood with a shallow enough draft to enable them to land 36 troops in a few feet of water. The advantage of the LCVP – which Eisenhower credited with playing a major role in the success of Overlord – was that it could carry vehicles.

The capture of a French or Belgian port was seen as crucial but unlikely to happen quickly, so British engineers came up with the radical idea of building components for harbours, towing them across to France and assembling them there. This would enable the speedy unloading of vital supplies. Codenamed Operation Mulberry, the harbours were created using floating outer breakwaters (bombardons) and static breakwaters made up of blockships (scuttled ships) held in place by a row of airtight concrete breakwaters (Phoenix caissons) which could be sunk and refloated. Within each harbour, piers were built to transport supplies to the shore. Two were constructed, Mulberry “A” to serve Omaha Beach; Mulberry “B” for Gold Beach.

An equally extraordinary engineering project was the construction of oil pipelines under the English Channel that would supply the fuel needed by the Allied armies in France when they moved inland. Because tankers on their own were vulnerable – to bad weather as well as attack – Operation PLUTO (Pipelines Under the Ocean) was developed. The pipes were laid on the Channel floor by unreeling them from a giant drum called a Conundrum, which functioned like a cotton bobbin and was towed by a tug. These were fed by a network of pipelines from all over England culminating in two coastal locations: Shanklin in the Isle of Wight, from where it was pumped along the seabed to Port-en-Bessin, and Dungeness in Kent and then over to Ambleteuse near Boulogne. The operation was shrouded in complete secrecy, with pumping stations disguised as ordinary buildings to reduce the threat of enemy attack.

Biography

Winston Churchill

Credit: Getty images

He is widely regarded as Britain’s greatest wartime leader, but for most of the 1930s, Winston Churchill was on the margins of British political life. The prevailing political orthodoxy was appeasement: making concessions to Hitler in order to preserve peace. Churchill was deeply opposed to this; from early on he recognized both Nazism’s barbarity and Hitler’s expansionist ambitions. His wasn’t a lone voice – many in the Labour Party were anti-fascist – but Churchill’s journalism allowed his arguments to be widely heard. When Hitler invaded Poland, having already annexed Austria and occupied Czechoslovakia, Churchill was proved right. His time had come.

Ironically, Churchill became prime minister following Britain’s failed invasion of Norway, which he had largely masterminded. He got the job because his only rival, Lord Halifax, didn’t seem to want it, whereas Churchill felt it was his destiny. Many more military defeats were to follow, but Churchill’s great strength was that he believed wholeheartedly in his cause and had the ability – through charisma and the power of his oratory – to convince most of his colleagues of the same, despite some of them wanting peace with Hitler. The evacuation of Dunkirk, when morale in the country was low and invasion seemed inevitable, prompted his famous “We will fight on the beaches” speech, climaxing with the words “We will never surrender.” The speech galvanized parliament and largely united the nation.

Britain’s lowest point was Churchill’s finest moment. His wit, his affable public face and his trademark “V for Victory” sign came to epitomize the defiant British bulldog spirit. Behind closed doors he was less easy to get along with. He had a prodigious energy for a man in his mid-sixties, in part due to regular afternoon naps, but he could be a bully; he was told off by his wife for being “rough, sarcastic and overbearing” with his staff. He was a better amateur strategist than Hitler, but he still infuriated his generals with his impetuousness and self-belief. The difference was that his generals and colleagues regularly stood up to him.

When the USA entered the war at the end of 1941, Churchill, in his own words, “slept the sleep of the saved and thankful”. The Americans had supported Britain financially since the start, but Churchill was convinced that the added manpower and firepower would tilt the balance of the war. He was right, but by the time of the Normandy landings it was the Americans – General Eisenhower and President Roosevelt – who set the agenda for the Liberation of Europe.

The only British citizens to experience occupation were the residents of the Channel Islands, a self-governing Crown dependency 32km west of Normandy. By the time the islands were demilitarized in June 1940 (after the Fall of France), around 25,000 inhabitants had already been evacuated. Most of the remaining 65,000 lived on the two largest islands, Jersey and Guernsey. A Luftwaffe raid at the end of June killed 44 and wounded 70, but once the Nazis realized the islands were undefended, invasion went ahead without further casualties.

The German administration worked in tandem with the existing civil authorities, who were forced to adopt and enforce any new Nazi laws, such as the confiscation of radios in 1942. Law-abiding residents were treated fairly respectfully, but the idea that this was a benign occupation (as some accounts have suggested) is misleading. Any resistance met with severe punishment; over one thousand islanders were imprisoned, two hundred of whom were deported to camps or prisons in Europe.

Although most Jews had left, the thirty or so that remained were subject to punitive laws, passed with little or no fuss from the authorities. Jews had to register themselves, wear the yellow star and relinquish their businesses. Jews were also deported to the Channel Islands, to work as slave labour, along with forced labour from across Europe. Much of the work took place on the isle of Alderney, which had been transformed into four camps, two of which were concentration camps run with excessive brutality by the SS. Work was mostly on fortifying the islands as part of the Atlantic Wall and many defensive structures are still visible. It is estimated that around one thousand people died on Alderney.

Bypassed by Operation Overlord in 1944, liberation finally occurred on 9 May 1945 when HMS Bulldog arrived at St Peter Port, Guernsey and the Germans surrendered. Many islanders were on the verge of starvation as a result of the Allied blockade. As with all occupied countries, questions over the extent to which people collaborated remain to this day.

The Germans were expecting an attack to occur in northern France sooner or later, but it was vitally important to keep them guessing as to the exact time and place. To create as much confusion as possible, the Allies devised elaborate schemes of misinformation. Operation Fortitude South invented an entirely fictitious 1st US Army Group (FUSAG), supposedly stationed in Kent and Essex, to suggest that the invasion would occur at Pas-de-Calais. Inflatable tanks made of rubber, fake landing craft and other military paraphernalia were manufactured at Shepperton studios, and the whole charade was “commanded” by US General George Patton – a soldier so renowned that the Germans were unlikely to think him wasted on a ploy.

To reinforce the illusion, a network of fictitious agents, believed by the Germans to be working for them – but who had in fact been invented by double-agents including Juan Pujol – was supplying German intelligence with convincing information about FUSAG. At the same time, the RAF was dropping more bombs and sending more reconnaissance flights over Pas-de-Calais than over Normandy. The combined effect, so the Allies hoped, was that the Germans would think that the Normandy landings were a prelude to the main invasion rather than the real thing.

One substantial Allied advantage was the fact that Ultra, the code-breaking project based at Bletchley Park, could decrypt the intercepted communications of the Axis powers and provide vital intelligence about the build-up of German troops and their defences in Normandy. The French Resistance was also active in the run-up to D-Day, supplying information and carrying out acts of sabotage against crucial infrastructure.

On 15 May 1944, the final Overlord briefing was held at St Paul’s School in London, General Montgomery’s headquarters. Eisenhower and all the Allied commanders attended, along with King George VI and Churchill. Montgomery gave the main briefing, exuding quiet confidence and expressing the belief that Caen would be captured within 24 hours. All the big decisions about Overlord had now been made, apart from D-Day (the precise date of the invasion) and H-Hour (the precise hour).

As June arrived, Eisenhower moved his Advance Headquarters to Southwick House near Portsmouth, a major naval centre and key embarkation point. He still had plenty of problems to contend with, not least the 69-year-old Churchill’s insistence that he be allowed to accompany the invasion – it took the King to persuade him otherwise. A bigger problem was the weather. The ideal situation for a mass landing was a low tide, a clear sky, little wind and a calm sea. The invasion date had been set for 5 June, but as the day approached senior meteorological officer James Stagg predicted a storm for that day. Eisenhower postponed, the storm duly arrived, but then new weather reports suggested a temporary lull and the invasion was back on track. On 6 June 1944 the vast Allied armada – the largest amphibious expedition in history – set out.

Every part of the United Kingdom made a contribution to the war effort: shipyards in Belfast and Govan; the coal mines of South Wales; munitions and military vehicle factories in Manchester. The port of Liverpool was especially important as the headquarters of the Western Approaches Command, charged with protecting merchant shipping during the Battle of the Atlantic – the struggle for control of the ocean which lasted the war's duration. Troops were stationed the length and breadth of the country, but in the build-up to Operation Overlord there was an inevitable gravitation towards the south of England because of its closeness to France. In the months before D-Day, the south coast began to resemble one vast military camp.

The Blitz killed thousands and drove millions of Londoners to leave the city, but ministers and the various departments of state stayed put, despite being located within the relatively small area of Westminster and Whitehall.

A near miss at No.10 Downing Street meant that Churchill was forced to move to a ground-floor flat in the New Public Office building (NPO), known as the “No. 10 Annexe”. In the basement of NPO were the Cabinet War Rooms (now the Churchill War Rooms), an underground complex that formed the nerve centre of Britain’s wartime strategy and policy-making.

The initial military planning for Operation Overlord took place at Norfolk House in St James’s Square, but when Eisenhower became Supreme Allied Commander he established his personal headquarters in Grosvenor Square and transferred many of the Norfolk House personnel. Norfolk House continued as a planning centre for Overlord’s naval commander Admiral Ramsay and the RAF commander Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory. In the run-up to D-Day, SHAEF headquarters was moved to a US Air Base in Bushy Park in the southwest of London.

Credit: IWM

Churchill’s bedroom at the Churchill War Rooms

London was also the temporary home to several governments-in-exile: the Poles at 39 Buckingham Palace Road; the Free French at 4 Carlton Gardens; the Norwegians at Kingston House North, Princes Gate; the Dutch at Stratton House in Piccadilly; and the Belgians at 105 Eaton Square.

Lambeth Rd, ![]() iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-london

iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-london

Established during World War I, the Imperial War Museum (IWM) contains a vast collection of objects and documents that show how war has impacted those living in Britain and the Commonwealth. It covers the period from 1914 to the present day, with one of its five floors entirely dedicated to World War II with a separate section on the Holocaust. There is plenty of military hardware on display, but the emphasis is as much on the experiences of civilians and what they had to endure. The IWM also administers the Churchill War Rooms and HMS Belfast, and two other museums.

Clive Steps, King Charles St, ![]() iwm.org.uk/visits/churchill-war-rooms

iwm.org.uk/visits/churchill-war-rooms

Built as a bunker in expectation of aerial bombardment, the Cabinet War Rooms were completed shortly before war was declared. As the main command headquarters of the war, space was at a premium and extra rooms were constantly added: Churchill was given a combined bedroom and office, with his hot-line to the US President disguised as a toilet. The War Cabinet met there 115 times, usually when air raids seemed imminent. The most significant space was the Map Room, a military information hub functioning around the clock, which produced daily intelligence summaries for the King, Churchill and the chiefs of staff. A museum since 1984, the rooms provide a unique insight into the pressurized lives of those who worked there. A separate section dedicated to the life and career of Churchill was added in 2003.

During World War II, most of the prominent figures in politics and the armed forces were men, and it is easy to get the impression that women were relegated to secondary roles in the war effort. Gender inequality in the 1930s and 40s was widespread, but the war demanded a fully mobilized workforce. Countless women made an invaluable contribution to the Allied campaign both at home and abroad.

In Britain, more than 640,000 women were active in the armed forces, most of them working in the Women’s Royal Naval Services (WRNS), the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). Many more drove ambulances, ferried aircraft between airfields (nicknamed “ATA-girls”) and served as nurses. In the USA, 350,000 women were employed in the organizations of their American counterparts. The Soviet Union – founded on communist ideals which saw men and women as equal – fielded around 800,000 women in the Red Army. More than half of them served as regular troops, but others starred as snipers, fighter pilots and tank commanders.

Women played an integral part in the resistance overseas, too. In Britain, just under one third of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was made up of women. Female special agents and ordinary members of the resistance risked their lives to help the Allied cause in the occupied territories. Gender stereotypes meant women were frequently treated with less suspicion than men, and became excellent couriers, spies, radio operators and saboteurs.

On the Allied homefront, millions of women were employed in war work, taking jobs that were previously reserved for men. More than two million women in Britain, and more than six million women in the USA, joined the domestic war effort. Their jobs were primarily in industry, but women also worked in agriculture, engineering and the auxiliary services. Naturally, many of the jobs in Britain were based in London. In the USA, “Rosie the Riveter” and “Wanda the Welder” became popular characters in propaganda. The increase of women in the workforce did lead to greater opportunity (at least temporarily), but women were consistently paid less than their male counterparts.

In Germany, Nazi ideology preached inequality and women were regarded as mothers and homemakers. Despite this, thousands of German women were employed in industry, primarily in the Nazi munition factories. Women also played an important part in defending Germany’s skies, and Hanna Reitsch and Countess von Stauffenberg were two of the Luftwaffe’s most prized test pilots.

Biography

General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Credit: Getty images

Having finally agreed to launch a second front in Normandy, scheduled for May 1944, the Allies were very slow to appoint the hugely important role of supreme commander. The obvious senior generals – the American George C. Marshall or the British Alan Brooke – were considered, but passed over in favour of Marshall’s protégé, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

This was the culmination of a meteoric rise for a soldier who had gone from being a mere colonel in March 1941 to commanding the American and Allied forces in North Africa in November 1942 and in Sicily during the summer of 1943. He almost certainly got the job because President Roosevelt realized that as well as being a brilliant administrator, Eisenhower possessed the kind of political acumen that was needed to keep the main Allied powers of Britain, the US and the Soviet Union working together, as well as US public opinion on board.

“Ike”, as he was popularly known, also possessed great personal charm, with a smile that one of his subordinates famously said was “worth an army corps in any campaign”. His calm demeanour and unifying presence enabled him to mould an excellent Anglo-American planning team in the build-up to D-Day and it won the affection, if not always the respect, of his more egotistical generals.

His own lack of direct battlefield experience meant that some seasoned generals were often withering in their criticism of him. The most regular clashes occurred with leading British general, Bernard Law Montgomery, whose talents as a military commander were matched by his tactlessness and conceit. Montgomery thought that Eisenhower’s insistence on a broad front strategy for the Allied drive across Europe was nonsense, feeling – after Normandy – that the quickest way to a German defeat was a single massed attack in the north with preferably himself (or, failing that, the American General Bradley) in command. Eisenhower rejected this, largely for political reasons. The Allies were a coalition of forces and he didn’t want one side (or general) taking the credit for victory.

While Eisenhower’s management was largely by consensus (which many found frustrating), he was more than capable of making tough strategic decisions when he had to. A good example was his absolute insistence, prior to D-Day, that the bombing campaign of the Allied air forces be diverted from targets in Germany to destroying the infrastructure of northern France. He was also capable of mistakes, but on the whole most of his decisions seemed to have been the right ones, and resulted, finally, in the overwhelming defeat of the Wehrmacht in western Europe.

The Queens Walk, ![]() iwm.org.uk/visits/hms-belfast

iwm.org.uk/visits/hms-belfast

The light cruiser HMS Belfast was built for the Royal Navy at Belfast in 1938. Belfast’s role on D-Day was as the flagship of Bombardment Force E, opening fire on the German gun battery of La Marefontaine in support of troops landing at Gold and Juno beaches. She remained in action in Normandy for over a month. Decommissioned in the 1960s, HMS Belfast is now a museum moored on the Thames and one of only a handful of surviving Royal Navy ships that served in World War II. Visitors can access all nine decks and visit a variety of rooms including the bridge, the operations room, the galley and the huge boiler rooms.

Beginning at Trafalgar Square, Whitehall is the street that becomes Parliament Street, which leads to the Houses of Parliament. With its adjacent side roads, Whitehall has long been the location of government offices and departments; some of these were relocated in the war, but most remained. Heading down from Trafalgar Square takes you past several key buildings, including the Admiralty, the War Office (now a hotel), the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Downing Street, with the prime minister’s residence at No.10, is halfway along Whitehall, a short distance from the Cabinet War Rooms in one direction and Parliament in the other.

Whitehall also contains a large number of World War II statues and memorials. In Parliament Square, Winston Churchill defiantly faces Parliament, while both Montgomery and Alan Brooke stand outside the MOD. There are memorials to the Women of World War II in Whitehall, and the Royal Tank Regiment in Whitehall Court. Those to the RAF and the Royal Navy Air Service and Fleet Air Arm are both behind the MOD on the Embankment.

Credit: iStock

HMS Belfast

Grosvenor Square in Mayfair is about a half-hour walk from Whitehall. During World War II so many official US buildings were located here that the square was nicknamed “Eisenhower Platz”. General Eisenhower’s headquarters were at No.20, the US Navy was next door at No.18, the Embassy at No.1, the US Lend-Lease Mission at No.3, and the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS) – a US intelligence agency – at No.70. A statue of President Roosevelt was erected on the northeast corner of the square in 1948; it was joined by one of a uniformed Eisenhower in 1989.

Kent and its neighbouring county, Sussex, make up the southeastern corner of Great Britain, the closest part of the mainland to France. Both counties were important embarkation points for Operation Overlord.

Their proximity to continental Europe also meant that Kent and Sussex were bombed throughout the war – from sea, air and German batteries in France. Coastal towns in particular were under constant attack: Dover and Folkestone in Kent were so badly bombed that the stretch of coastline near them became known as “Hellfire Corner”.

A few kilometres down the coast from Folkestone is Romney Marsh, an area near the Kent-Sussex border bounded by the Royal Military Canal on one side and the sea on the other. The Romney, Hythe & Dymchurch Railway runs the length of the marsh’s coastline. The area has a long association with military defence and was a key point in Hitler’s planned invasion of Britain. Several surviving World War II pillboxes are visible along the canal, and four Advanced Landing Grounds (ALGs) – small temporary airstrips built to support D-Day – were sited in the area. Dungeness, the headland of Romney Marsh, was an assembly point for one of the Mulberry harbours built for the Normandy landings, and was also the point from where one of the PLUTO undersea pipelines started. A little further up the coast at Littlestone-on-Sea there’s an abandoned Phoenix caisson that’s visible at low tide.

Credit: iStock

Dover Castle

Castle Hill Rd, Dover, ![]() english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle

english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle

As the closest point to mainland Europe, Dover and its famous white cliffs became a potent symbol of British resilience in World War II. Dover Castle sits high above the harbour, a major defence against invaders for centuries. During the war its array of tunnels had many uses: Casement Tunnel was Admiral Ramsay’s naval headquarters, from where he planned the evacuation from Dunkirk; Annex was a military hospital; and Dumpy was built in 1943 as a regional government centre in case of nuclear attack. Other tunnels were used as air-raid shelters. The castle was also one of the sites of the fictitious 1st US Army Group, created to fool the Germans into thinking the invasion would land at Pas-de-Calais. Even after D-Day, Hitler was convinced that the real invasion would be launched from Dover. As a result, the town became the target for some of the heaviest German shelling since the beginning of the war. Remains of Dover’s wartime defences can be seen along the cliffs between Dover and Folkestone.

Credit: Getty Images

A group shelters in the Ramsgate Tunnels during an air raid

Marina Esplanade, Ramsgate, ![]() ramsgatetunnels.org

ramsgatetunnels.org

Ramsgate was another vulnerable Kent town. Before the war started, its farsighted mayor nagged central government to allow him to build Deep Shelter Tunnels as protection against air raids. Four kilometres were eventually built (in addition to the existing railway tunnel). Many people evacuated the town when the heavy bombing started, the remainder sought refuge in the tunnels, which had entry points around the town. Entire families lived there almost permanently, and a whole underground community grew up with shops, street signs, a hospital and even a concert hall. Some of these tunnels can now be visited.

The brainchild of two racing-car enthusiasts, this miniature railway (one-third normal size) has been running along the coast between Hythe and Dungeness since 1928. In World War II the line was requisitioned by the War Office and used to transport material for the building of PLUTO, the undersea oil pipeline. Twenty-one kilometres long, the railway has five other stations between Hythe and Dungeness (some of which are request stops) where other wartime sites can be visited.

A bleak, windswept expanse of shingle right at the tip of Romney Marsh, Dungeness was one of two sites chosen from where oil pipes were laid under the English Channel to France. PLUTO was a complex engineering project conducted in total secrecy shortly after Operation Overlord was launched. Pluto Cottage, a pumping house built to resemble a small house, still exists at Dungeness and five more disguised installations can be seen at Greatstone-on-Sea, six kilometres up the coast. Fifteen kilometres inland from Dungeness at Brenzett is a small museum, the Romney Marsh Wartime Collection, which details the area’s wartime connections.

The county of Hampshire, which lies in the middle of England’s south coast, has long historical ties to the navy.

Portsmouth, the home of the Royal Navy, sits almost directly opposite the Cotentin peninsula, and was a major D-Day embarkation point. In June 1940, General Eisenhower moved his headquarters to Southwick House just north of the city. To the west of Portsmouth, the town of Gosport, and to the east Hayling Island, were both important sites in the building of the Mulberry harbour components that were towed across to Normandy. Portsmouth was heavily bombed throughout the war, as was the nearby port of Southampton. In 1940, the Spitfire factory in the Southampton suburb of Woolston, where the plane had been developed, was targeted and completely destroyed by the Luftwaffe.

The New Forest, a unique mixture of heathland, woodland and river valleys, was an ideal area for training in the build-up to D-Day, and many exercises took place there. Three kilometres across a strait of the Channel known as the Solent is the Isle of Wight, one of the sites chosen for Operation PLUTO. The pipeline joined the island at Thorness Bay before connecting to Shanklin and Sandown on the island’s southeast coast. From here, fuel was carried under the Channel to Port-en-Bessin, close to Omaha beach.

Clarence Esplanade, Portsmouth, ![]() theddaystory.com

theddaystory.com

Located on the seafront close to Southsea Castle, the D-Day Story Portsmouth is a museum entirely dedicated to Operation Overlord, both the events leading up to the invasion and the day itself. It’s a large and varied collection, with many personal artefacts – letters, paintings, photographs and maps – as well as military hardware. There is plenty of child-friendly interactive and audio material that helps bring the events to life, and the museum’s excellent website is crammed with a wealth of detailed historical information. The Overlord Tapestry, 34 embroidered panels depicting the unfolding events of D-Day, provides a vivid and colourful climax to the displays.

Credit: Portsmouth City Council

D-Day Story Portsmouth exhibit

A half-hour walk northeast from the D-Day Story museum takes you to Quay House on Broad Street. This handsome Art Deco building was used as offices in the 1930s, but in the preparations for D-Day it became the Embarkation Area Headquarters for the Portsmouth sector. Military personnel at Quay House played a vital role in ensuring the campaign ran efficiently, organizing the launches of the Allied troops from four areas across Portsmouth. Recently converted into flats, it can only be viewed from outside.

Eight kilometres north of Portsmouth near the village of Southwick is Southwick House, the final command post of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Admiral Ramsay and General Montgomery moved here from London at the end of April 1944, General Eisenhower on 1 June. A large plywood map of the English south coast and the French coastline from Calais to Brest still adorns the Map Room, where meetings were held and plans finalized. It was at Southwick House that James Stagg presented the weather report which delayed D-Day by one day. Eisenhower’s personal headquarters – an office tent and a trailer for sleeping in – was hidden from sight in nearby woods. Visiting the house can only be done by prior appointment; contact the Defence School of Policing and Guarding at DSPG-HQ-Information@mod.uk.

Credit: Getty Images

Southwick House

Haslar Jetty Road, Gosport, ![]() nmrn.org.uk/submarine-museum

nmrn.org.uk/submarine-museum

The highlight of the Royal Navy Submarine Museum is undoubtedly HMS Alliance, an Amphion-class attack submarine of the type used in World War II, although this one wasn’t launched until July 1945. A tour of the submarine takes you through several areas, including the control room, accommodation space and the galley. The museum itself is also worth visiting, especially for its two midget submarines, one of them a British X-Craft similar to those used for surveillance of the Normandy beaches in January 1944, and in guiding landing craft onto Juno and Sword beaches during D-Day.

Credit: iStock

Royal Navy Hospital Haslar

Haslar, Gosport, ![]() haslarheritagegroup.co.uk

haslarheritagegroup.co.uk

The Royal Naval Hospital at Haslar on the Gosport peninsula was founded in 1753 to treat British servicemen. During D-Day and its aftermath it was a key treatment centre for soldiers injured in action. Around 1347 casualties arrived here within three months of the first Normandy landings. Run by the US Military during 1944 and 1945, staff treated both Allied soldiers and German prisoners of war before transferring them to other hospitals around Britain. In 2013 the Ministry of Defence sold the 25-hectare site to a private developer, but there are occasional tours organized by the Haslar Heritage Group. The nearby Haslar Royal Naval Cemetery (entrance in Clayhall Road) is where many of the wounded from D-Day who did not recover are buried.

Hayling Island, along the shoreline of Langstone Harbour, was one of the places where Mulberry harbours were constructed. A wrecked Phoenix caisson, almost broken in half, can be seen just north of the entrance to the harbour. The island is also where Combined Operations Assault Pilotage Parties (COPP) was based. This top-secret unit carried out clandestine reconnaissance missions investigating the beaches and in-shore waters of both Sicily and Normandy. Canoeists and frogmen set out from boats or submarines to gather vital information that would help in the planning of the amphibious landings. A World War II Heritage Trail, beginning near Hayling Island ferry landing, highlights the island’s most important World War II sites, including the recently erected COPP memorial.

The New Forest was a hive of activity throughout the war and in the run-up to the Liberation. Ashley Walk, a remote northern part of the forest, was the site of a major bombing range where most Allied bombs, including the famous Dambusters bouncing bomb, were tested. The forest was also home to several clandestine bases, some of which, like the Hydrographic Survey, were located at requisitioned houses along the Beaulieu River. Members of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) received their final training at the Beaulieu Estate before deployment as secret agents in Europe, while the nearby estate village of Buckler’s Hard was where motor torpedo boats were built, as well as dummy landing craft used to deceive the Germans about Allied landing plans. Lepe Beach, close to the mouth of the Beaulieu River, was a construction site for Mulberry harbours and the point from which the PLUTO pipeline left the mainland to connect with the Isle of Wight. Many remains of the workings lie scattered along the shoreline. Balmer Lawn Hotel at Brockenhurst was used as an Army Staff College before becoming the divisional headquarters of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and an occasional meeting place for key Allied commanders. There were twelve airfields in the New Forest, including four Advanced Landing Grounds, temporary sites built specifically to support troops in Normandy. A memorial to the airfields can be found at the former site of one of them, Holmsley South.

Credit: Alamy

Rainbow over the New Forest

Dorset is the coastal county west of Hampshire. Many American troops were stationed here prior to D-Day, with training and exercises taking place across the whole county. This often involved using live ammunition and sometimes required the evacuation of local residents.

Poole, Weymouth and the Isle of Portland were all key D-Day embarkation points, and hundreds of thousands of US military personnel left from these three ports alone. A memorial on Weymouth Esplanade and another in Portland’s Victoria Gardens commemorate their departure for Normandy. Two well-preserved Phoenix caissons, towed back from France after the war, stand in Portland Harbour. In 2018, six life-sized sculptures, representing four servicemen and two Portland dockyard workers, were placed on top of them. RAF Tarrant Rushton (now private farmland) was the departure point on 5 June 1944 for six Horsa gliders, each towed by a Halifax bomber, carrying men from the British 6th Airborne Division on a mission to capture the Pegasus bridge at Caen.

Bovington, ![]() tankmuseum.org

tankmuseum.org

One of the largest collections of armoured vehicles in the world, the Tank Museum outlines the development of the tank from its beginnings to the present day. There are six large halls, one of which is entirely devoted to World War II and contains tanks from several of the combatant nations, including the feared German Tigers, and some examples of “Hobart’s Funnies” (see box). Several of the tanks are still in working order. Visitors can go behind the scenes to see vehicles being restored, and there are regular talks, events and exhibitions.

Credit: Shutterstock

American M26 Tank at Bovington's Tank Museum

Studland Bay, ![]() nationaltrust.org.uk/studland-bay

nationaltrust.org.uk/studland-bay

Studland Beach was the site of a major D-Day rehearsal, Exercise Smash, that took place on 18 April 1944. King George VI, Winston Churchill and General Eisenhower witnessed the action from the safety of a nearby concrete bunker, Fort Henry. Live ammunition was used and the exercise was an opportunity to try out the new floating tank (see box). Tragically, several of the tanks sank, resulting in the drowning of six men. The area is now part of a National Trust walk on which various World War II defences can be seen, including Fort Henry where a memorial plaque commemorates those who died.

In December 1943 the last inhabitants of picturesque Tyneham left their homes, relinquishing their village to the army as a part of a wider area used for military exercises. The villagers were promised that they could return when the war was over, but it never happened. Tyneham was compulsorily purchased and, despite years of lobbying by villagers and others, the Ministry of Defence refused to relinquish it. All the buildings are now in ruins except for the church, a poignant memorial to a lost way of life. Public access is permitted on most weekends and a few other times; dates and details can be found on the website.

Percy “Hobo” Hobart was an irascible Major General and an expert in armoured vehicles who managed to irritate so many people at the War Office that in 1940 he was retired early. He might have spent the rest of the war as a corporal in the Chipping Camden Home Guard had not Churchill intervened, bringing him back and putting him in charge of the 11th Armoured Division. Mutterings and resentment were still directed against him, but in 1943 he was given command of the 79th Armoured Division, with clear instructions to devise specialized armoured vehicles to combat the Atlantic Wall defences during the Normandy landings.

Hobart and his team came up with a number of frequently outlandish but effective ways in which tanks could be modified. These were collectively known as “Hobart’s Funnies”, and included an amphibious Sherman tank complete with propellers and an inflatable canvas float screen; the Churchill “Bobbin” tank that could lay reinforced matting on ground too soft to support armoured vehicles; the “Crab”, which was a Sherman with a flail at the front for clearing mines; the flame-throwing “Crocodile”; and the AVRE which instead of a gun had a mortar capable of destroying concrete obstacles. When used correctly, these proved invaluable during Operation Overlord and later campaigns.

East Anglia, the bulge sticking out of the east side of England, is made up of the counties of Suffolk, Norfolk and parts of Cambridgeshire and Essex. Its proximity to the European mainland – the Netherlands is about 225 kilometres across the North Sea – and the flatness of the landscape made the area ideal for airfields in World War II.

Over one hundred airfields were built in East Anglia for both the RAF and the USAAF. Airmen from the US began arriving in 1942 and by 1943 there were about 100,000 of them stationed in Britain. Many were based in East Anglia, including all of the Eighth Air Force and some of the Ninth. Nearly all of the airfields are commemorated in some way, and memorials to individual airmen or aircrews can often be found near where their planes crashed, but the largest resting place for US air personnel is the magnificent American Cemetery near Cambridge.

Credit: Shutterstock

IWM Duxford

A handful of airfields are still functioning, but most have been returned to farmland or have been built on. Some stray buildings and bits of runway can also be found, and a few of these have been turned into small museums, such as the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum near former RAF Bungay, and the Parham Airfield Museum on the site of RAF Thorpe Abbotts. On a much larger scale is the Imperial War Museum at Duxford, the former site of RAF Duxford.

Duxford, Cambridgeshire, ![]() iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-duxford

iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-duxford

From April 1943, RAF Duxford was home to the US 78th Fighter Group, which escorted bombers on raids across Europe and later supported ground troops in Normandy. The airfield closed as an RAF base in 1961 and is now part of the Imperial War Museum as well as home to the American Air Museum; it is still an active airfield and there are regular air shows. There is a wide range of objects on display, but the emphasis is on aviation, with an outstanding collection of planes, many exhibited in the airfield’s original hangars. Of the permanent displays, The Battle of Britain and the 1940s Operation Room relate specifically to World War II, while the Normandy landings feature in the Land Warfare Exhibition, with Montgomery’s wartime caravan among the exhibits. The American Air Museum displays eighteen planes, including a B-17 Flying Fortress, the famed bomber that took part in many missions across Germany.

Coton, Cambridgeshire, ![]() abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials

abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials

A few kilometres northwest of Cambridge is the only permanent World War II American cemetery in Britain, containing the graves of over 3800 servicemen and women, among them many who served in the airfields of East Anglia. Burials began here in 1943, but it only became an officially dedicated site in 1956. The 12-hectare grounds, donated by Cambridge University, are beautifully landscaped and the surrounding woodland adds to the tranquil atmosphere. A dignified memorial hall of pristine Portland Stone contains a chapel at one end and a large marble map at the other showing the main US areas of action in Europe and the Atlantic. A separate visitor centre provides further historical context through a permanent exhibition containing personal stories, photographs and interactive displays.

Birds Lane, Horning, Norfolk, ![]() radarmuseum.co.uk

radarmuseum.co.uk

Radar was an important piece of military technology in World War II, which enabled those on the ground and in the air to detect the approach of enemy aircraft. This small museum occupies the 1942 radar operations block that was once part of RAF Neatishead. It tells the story of radar’s defensive use from the 1930s to the Cold War, with many fascinating exhibits, including much of the original equipment. It is well worth attending the talks by enthusiastic volunteers, many of whom worked here when the site was operational and highly secret.

Credit: Getty Images

Gravestones at Cambridge American Cemetery

Combined Military Services Museum

Station Rd, Heybridge, Maldon, Essex, ![]() cmsm.co.uk

cmsm.co.uk

Tucked away in a former warehouse, this museum displays an eclectic and extremely impressive collection of militaria from medieval times to the present day. There’s a good selection of material relating to World War II, with an emphasis on spying and secret operations, including the equipment used by wartime secret agents such as booby traps and sabotage gear. There’s also a display about Operation Frankton, the raid in 1942 by ten commandos (the “Cockleshell Heroes”) who planted mines on German ships docked at Bordeaux. The material includes one of the original Cockle Mk II canoes used in the raid.

Memorials and museums about World War II can be found throughout the British Isles, from Penzance in Cornwall to the Shetland Isles.

The following sites relate to events and operations directly connected with preparing for the Liberation of Europe, most of which took place in the southern half of the UK.

International Bomber Command Centre

Canwick Hill, Lincoln, ![]() internationalbcc.co.uk

internationalbcc.co.uk

The role of Bomber Command and its commander-in-chief Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris remain among the most controversial issues of World War II, and recognition of the bomber crews’ bravery and their contribution to the Allied victory was slow in coming. The RAF Bomber Command Memorial in London’s Green Park was only erected in 2012. The International Bomber Command Centre (IBCC) was conceived around that time and opened in Lincolnshire in 2018 – in the county where around a third of all Bomber Command stations were based during the war. The IBCC is both a memorial ground and an education centre. A huge spire – the length of a Lancaster bomber’s wingspan – towers over the site, flanked by curved steel walls bearing the names of the 57,871 men and women who died in the command’s service. In the nearby Chadwick Centre, personal stories of bombers and air-raid victims are told through film, audios and interactive displays.

Halifax Way, Elvington, York, ![]() yorkshireairmuseum.org

yorkshireairmuseum.org

The museum occupies the site of former RAF Elvington, which from 1942 to 1944 housed 77 Squadron RAF Bomber Command, and thereafter was home to two French squadrons – the only exclusively French airbase in the country. It is now a sizeable aviation museum with an outstanding collection of planes, ranging from the earliest days of flight to recent times. Among several World War II aircraft are the Halifax bomber, a Douglas Dakota and the troop-carrying glider, the Waco Hadrian, that could be towed behind it. The museum also acts as the Allied Air Forces Memorial.

Invented by Arthur Scherbius, the Enigma was an encryption machine that converted plain text into apparent gibberish via three rotors, each wired to scramble the letters every time a key was pressed. The recipient then unscrambled the message by using the same setting on his or her Enigma machine.

Adopted by the German armed forces and intelligence services in the 1920s, Enigma was considered to be an unbreakable system. In fact, Polish mathematicians – including the brilliant Marian Rejewski – had broken the ciphers as early as 1932, using electro-mechanical machines known as “bombes” to search for solutions. The Poles shared their discoveries with the British, enabling them to develop their own version of the bombe. In 1941, Alan Turing succeeded in breaking the German naval Enigma.

The Lorenz, a twelve-rotor machine, was even more sophisticated, becoming the machine of choice for top-secret Nazi communications. Without access to an actual machine, Bill Tutte, another Bletchley mathematician, discovered how it worked from signal traffic.

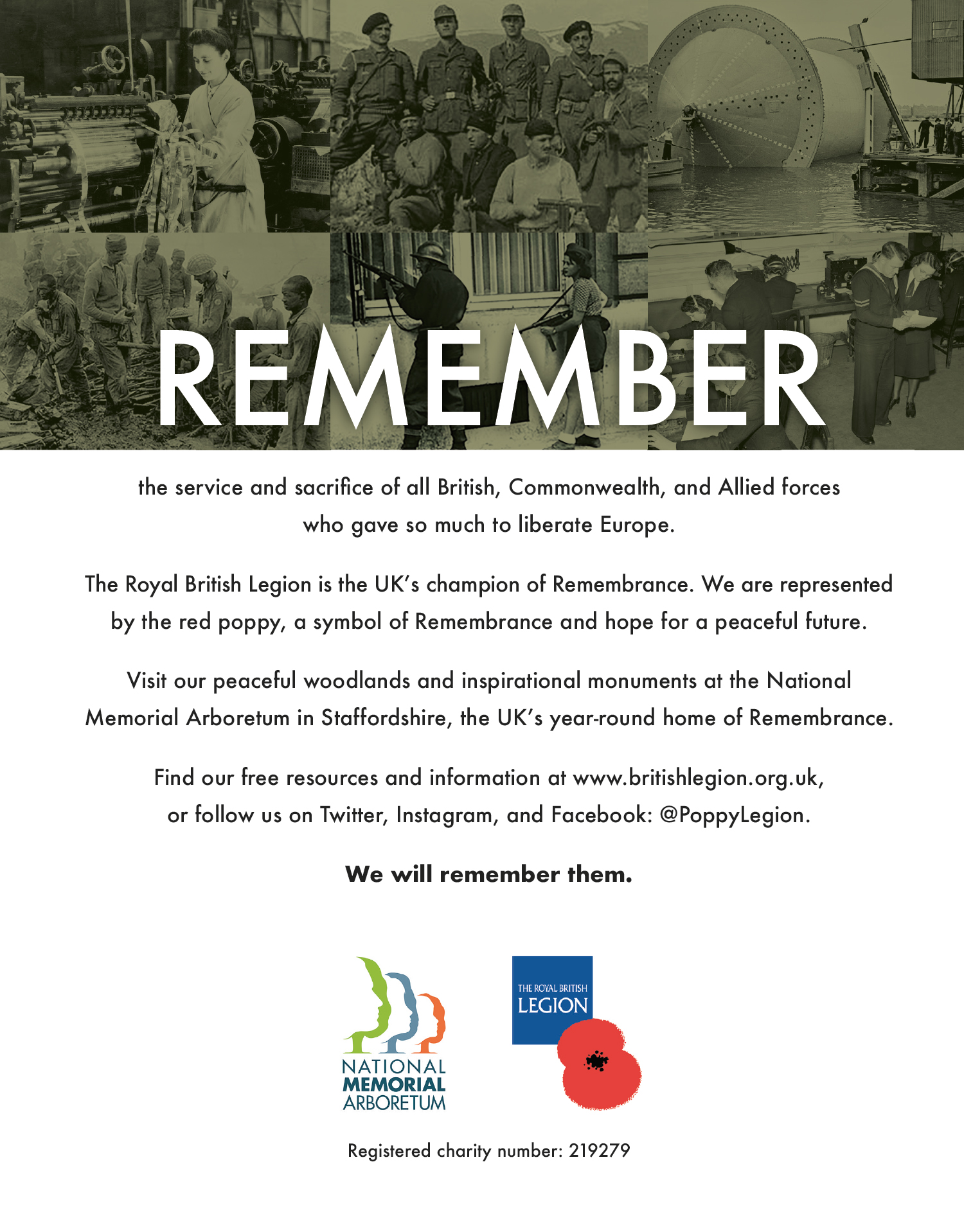

Croxall Road, Alrewas, Staffordshire, ![]() thenma.org.uk

thenma.org.uk

The National Memorial Arboretum is a place of remembrance containing 350 memorials and over 30,000 trees. In 2014 the Normandy Campaign Memorial was erected to mark the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings, with a design based on the view of the undulating Normandy coastline as seen by the approaching Allied troops in June 1944. Covering some 60 hectares, the arboretum is not a cemetery but a living monument to those who have served Britain, the Empire and Commonwealth, not just in the armed forces but also in such civil organizations as the merchant navy, the police and the ambulance service.

Trafford Wharf Rd, Manchester, ![]() iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-north

iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-north

The IWM North is located in Trafford Park, a former industrial site where Lancaster bombers were manufactured during the war, making it a prime target for the Luftwaffe during the Manchester Blitz. The arresting building is by Daniel Libeskind, an architect who specializes in memorials and war museums. The design divides the building into three sections representing war on land, sea and air, and is deliberately disconcerting: some floors tilt, there is no grand entrance to the museum, and the emphasis is on the impact of war more than on military hardware. It’s a different approach from IWM London, with more space for contemplation.

1–3 Rumford Street, Liverpool, ![]() liverpoolwarmuseum.co.uk

liverpoolwarmuseum.co.uk

A bomb-proof bunker was built into the basement of the 1930s Liverpool Exchange Building, and from 1941 this became the headquarters of the Western Approaches Command. It has now been restored and turned into a fascinating museum. The maze of rooms includes the Map Room, the nerve centre of the Battle of the Atlantic, where Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) and Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) personnel worked 24 hours a day monitoring convoy routes, and the Cypher Room where decrypted messages were exchanged with Bletchley Park (see below). Other exhibits include the original Gaumont projector on which Churchill – a regular visitor – watched top-secret footage, and a recreated 1940s street.

Bletchley, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, ![]() bletchleypark.org.uk

bletchleypark.org.uk

Bletchley Park is another wartime operation commemorated only recently, in this case because of the highly secretive work that was done there at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS). The place where thousands of code-breakers repeatedly cracked encrypted German messages is now a fascinating museum. The original Victorian mansion has temporary and permanent displays, and some of the huts and blocks have been restored. Alan Turing’s office is in Hut 8, while the exhibition in Block B contains a large collection of Enigma machines.

Resistance organizations across Europe made an enormous contribution to the Allied war effort and the ultimate Liberation.

In the popular imagination, the resistance movements of Europe tend to be seen in one of two ways. They are either mythologized as heroic but hopeless struggles of amateurs, or are marginalized, credited with performing only minor ancillary actions that did not have a decisive impact on the final victory.

Credit: Getty Images

Two French spies deny charges of acting as informers for the Nazi Gestapo

The resistance in any given country amounted to a war within a war. Its members carried out activities, usually on a local scale, that are often overlooked when set against the great, decisive battles of the liberating armies. No pan-European resistance movements emerged during the war, partly because totalitarianism proved highly successful at preventing its enemies from uniting. Instead, each country developed its own home-grown opposition to the occupier. These varied according to a number of regional factors, but most shared some common features.

It is hard to garner an accurate picture of resistance movements because of their intrinsically secretive nature. Directly after the Liberation, few reporters or photographers took an interest in resistance activities – most kept their focus on the front line, broadcasting to a readership less moved by the skirmishes of provincial backwaters than the glamour of battle. Activists themselves deliberately kept few written records for reasons of personal safety. After the war, the members of the resistance who survived were able to set down their own versions of events – sometimes with no one left to challenge them.

The resistance was multifarious and variegated in almost all senses. Most groups took the form of unofficial, ad-hoc, grass-roots movements that defied the conventions of military organization. Resistance fighters were volunteers, motivated by a range of political or pragmatic reasons. They received little training, working in a small band in which comradeship might matter more than discipline. There was often nothing in the way of hierarchy, with no generals or government department to rule on its operations. Notable exceptions exist, of course. The Polish Home Army, for instance, was a large and coordinated force run strictly along military lines.

The resistance was frequently a murky, messy affair in which difficult compromises had to be made. Paramilitary activities shaded into organized crime – which supplied the resistance with black-market weapons and forged documents.

For these reasons, it was a challenge for British and American commanders at the time, and has been for historians ever since, to make sense of the resistance in any uniform fashion. Many of the facts related to the resistance are vague or questionable. Even the simplest information – such as how many members an organization had – could be disputed, frustrated by what actually constituted being a member of the resistance. Above all, and in the majority of cases, national resistance movements were small and non-hierarchical. The opposite of static military armies, the resistance was mobile and agile. As the war progressed and new developments unfolded, many of these grass-roots movements changed their aims, targets and strategy.

Organization of the resistance

Resistance typically began with small, isolated and personal acts of defiance and dissent intended to frustrate the Germans. Passive resistance – strikes and rail go-slows – continued throughout the war. Other individuals decided that, although their governments had collaborated or fled into exile and their regular armies had surrendered, the war must be carried on by other means. These brave men and women were driven by a variety of motives, sometimes solely united by their conviction that something had to be done.

Credit: Getty Images

Yugoslav resistance in Italy

Several resistance groups operated within each country, founded on different philosophies. At the heart of many resistance groups were radical political activists, notably communists – who had to initially defy the party line from Moscow that sought to honour the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact. People of numerous religious denominations, predominantly Protestants and Catholics, also aided the resistance, fostering a moral duty not to give in to evil.

Women were well represented in resistance movements everywhere, especially when men had been taken as prisoners of war or were forced to migrate for work. When the Nazis introduced measures to send young men to German factories as forced labourers midway through the war, membership of the resistance soared: many people went into hiding to avoid being sent abroad.

Although resistance movements are often categorized in relation to country – the French Resistance, for instance – in practice, they were often multinational. Jews, political refugees and deserters from the Allied armies were welcomed to boost numbers. In France, many Republicans from Spain, defeated in their civil war, joined the Resistance, believing Franco could be toppled after the Nazis were overcome. These fighters brought with them valuable combat experience.

The resistance undertook a variety of functions simultaneously. Espionage and gathering intelligence were incredibly important. Members of the resistance collected what information they could, transmitting their findings back to London to help inform military operations.

Nazi occupation depended on functioning infrastructure, which was therefore targeted by the resistance through acts of sabotage. Repairs to bridges and railway lines interfered with the Nazi deployment of both troops and supplies, whilst also tying up valuable manpower.

Credit: Getty Images

Four Italian resistance fighters wait in ambush in the Apennines in May 1944

There are numerous examples of resistance movements engaging the enemy troops, too. Once the Liberation was underway, it was easy for the resistance to emerge from the woodwork, but it was always risky for a unit to draw attention to itself. As well as staging major urban uprisings and carrying out a number of high-profile assassinations, the resistance was also responsible for the deaths of many German officers. These courageous acts were often met with brutal reprisals. For the Allied military, the resistance also operated escape routes – especially for airmen who had been shot down in the occupied territories. One of the most famous of these routes ran from Belgium to Spain across the Pyrenees.

A final, vital and unspectacular role performed by the resistance was maintaining morale. Undercover organizations across Europe operated clandestine printing presses and distributed anti-German propaganda so that a forbidden “free” politics continued even in the face of Nazi repression. While there was an active resistance, there was still hope to the end of occupation. Intellectual resistance may not have saved any lives, but it preserved the values of a country until they could be revived in peacetime. The resistance also reminded the weak-willed that after the war there would be recriminations against those who had collaborated.

To become a member of a resistance organization was seldom an easy choice. It meant living a new and dangerous life. Activists had to decide whether to remain in society incognito, or to take refuge in the forests or hills. In France, the latter approach was taken by the so-called Maquis; in the flat and densely populated Netherlands, however, it was nearly impossible to survive in the wild.

Successful members of the resistance were excellent listeners and observers, good judges of character and fluid liars – extemporizing according to need. None of these qualities was of any use without a large dose of luck. However many precautions were taken, the risks remained high. The resistance was, on many occasions, betrayed by informers from within their midst. Double agents, driven by greed for Nazi money and power, or by fear for their families, sent many experienced fighters to the torture chambers and prisons of the Gestapo.

The recompense for too many members of the resistance was incarceration and execution. The German authorities saw them as common criminals and terrorists fighting an irritating but futile war. If the Nazis couldn’t identify the instigator of an action against them, the punishment was collective and brutal: a number of hostages were rounded up and executed en masse as an example to the rest of the population. One of the largest reprisals was undertaken in the Ardeatine caves in Rome in March 1944.

The effect of Nazi reprisal, however, was never enough to deny the resistance the support they relied on from ordinary people. In this respect, the resistance was undeniably successful: the occupying troops never felt safe. Any normal civilian could be an operative in disguise, concealing a lethal weapon.

In Germany, the Nazis managed to quash almost all resistance by rounding up their opponents and deporting them to the concentration camps. They cowed the rest of the population with diatribes conflating the ideology of the regime with patriotism. In Poland, Czechoslovakia and Belgium, that was impossible. A police state is never a stable, safe and comfortable country – even for the police.

World War II historians still argue over the impact of the resistance in one country or another. The resistance undeniably supported the armies of the Liberation – for example cutting phone lines and blowing bridges before D-Day – but was their contribution vital or just helpful?

The impact of the resistance must be understood on a local scale. Its effect was regional, but significant. Occupied Europe was too large for the great armies to be everywhere at once, and often – as in much of France – it was the resistance that carried out the final liberation. In some places, its members waited for the German garrison to decamp before moving in, to ensure a smooth transition from occupation to a new normality. The resistance was also part of the peace process – which sometimes involved summary executions of local fascists and (alleged) collaborators – but also included a restoration of civic power. Most of all, a country’s history of resistance is its own, not an adjunct to the history of a dominant power overseas.

Credit: Getty Images

Members of the Maquis, the French Resistance

Brave acts of resistance – the Warsaw and Prague uprisings, the partisan republics of northern Italy or the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in Prague – provided moments of pride and achievement in what is mostly a dark period of human history.

Credit: Getty Images