The defeat of France by Nazi Germany in the spring of 1940 was as inexplicable as it was humiliating. Until then, France had been one of the great world powers, apparently safe behind the defences of the Maginot Line.

In a matter of weeks France was overrun, and the combined forces of the French and British armies that were meant to repel Hitler were forced to retreat to Dunkirk for evacuation. Historians still argue whether Germany’s swift victory was due to luck or military superiority, but the result was the same. In May, the French government faced an impossible decision: fight on and risk an even more crushing defeat or sue for peace. The government was split by this choice.

A group of pragmatists and realists – as they thought of themselves – decided to come to terms with Hitler. Both parties to the armistice of 22 June 1940 assumed it would be a temporary arrangement until Britain made its own peace with the Nazis or succumbed to invasion. A sizeable minority in France was always against the armistice, centring on the figure of General Charles de Gaulle. De Gaulle managed to escape to London to rally the French opposition. A government-in-exile was formed, and military personnel who had escaped capture eventually formed the Free French forces that would participate in the liberation of their country.

The invasion of Britain never materialized, and the Germans stayed on in France. The French had to get used to a new way of living. Half their country (the north and west) was occupied by enemy troops; the centre, east and south were controlled by the Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain. Meanwhile, the bulk of the French soldiers, taken prisoner in 1940, were left languishing in German prison camps or put to work in German industry or agriculture.

Credit: Getty Images

German occupation of Paris, June 1940

Occupation meant difficult compromises for almost every French citizen, but it also unleashed the worst of right-wing politics. The authoritarian Vichy regime collaborated closely with the German authorities, aiding the deportation of 76,000 French Jews, of whom only 2500 survived. In November 1942, the Wehrmacht extended the occupation to cover the whole of France. Work began to fortify the west coast against an attempted Allied invasion. A disastrous raid on Dieppe by British and Canadian forces proved how difficult it would be to land an army on the European continent.

German domination also provoked the growth of the French Resistance – a movement of people from divergent political persuasions that became increasingly active as the likelihood of an Allied invasion increased. German reprisals against the partisans were disproportionate and brutal. The invasion of Italy in the summer and autumn of 1943 brought fresh hope to France, especially as it entailed the liberation of Corsica on 4 October 1943, the first French territory to be regained from the occupiers. Unbeknownst to either the Germans or the French – although the Resistance was partially informed – the Allies had set a date of spring 1944 for an invasion of France. This involved meticulous planning and an immense build-up of soldiers and ships. The experience of 1940 was in everyone’s mind: there could only be one chance to liberate occupied France, and its success was never a given. It would depend on many factors, predictable and unforeseeable, far beyond the skill of the military commanders.

Significant sites

Significant sites are marked on the map

Credit: Liberation Route Europe

Caen Memorial Museum

At first light on the morning of 6 June 1944, one of the largest fleets ever assembled appeared in the Baie de la Seine and approached the north coast of Normandy.

Four years after the crushing defeat of France, Belgium and the Netherlands, the Anglo-American Allies finally launched Operation Overlord – the Battle of Normandy. The campaign was kickstarted by Operation Neptune, a massed landing of troops and equipment on the occupied European continent. The invasion would force Nazi Germany to open another front, stretching their resources. In the east, German troops were already locked in battle with the Soviet Union; now they would have to confront an enemy approaching from the west.

Normandy was chosen because of its proximity to the British coast. Allied aircraft would be able to support troops, especially during the landings that would form the initial phase of the assault. Almost as importantly, Britain would be able to supply the Allied armies as they travelled east. German defences along this stretch of coast were also less formidable than on the beaches of Pas de Calais where the Channel was at its narrowest, and where the Germans expected the attack to come.

A fleet of more than 6900 vessels had been assembled to land more than 156,000 men on five Normandy beaches, which were given codenames (from west to east): Utah and Omaha (US), Gold (British), Juno (Canadian) and Sword (British). About 24,000 airborne troops were also deployed to take control of various strategic points and to prevent German attacks on the flanks of the assault forces on shore. D-Day was mostly an Anglo-American effort: British, American and Canadian troops made up most of the numbers, but no fewer than seventeen Allied countries participated on the ground, in the sea and in the air.

Following the abandonment of plans to invade Britain in 1940, the assault on the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the USA’s entrance into the war in December 1941, German strategy in the West changed from the offensive to the defensive. Hitler agreed to the construction of a fortified line along the western coastline of the occupied territories, capable of repulsing any Allied attempt to land on the continent. German propagandists would later claim that the Atlantic Wall “stretched from northern Norway to the Spanish border”, but it really protected the most vulnerable coastlines of the Netherlands, Belgium and France. For Field Marshal von Rundstedt, commanding the western German ground forces, that still meant building defences along almost 5000km of coast.

Construction work of the Atlantic Wall began in March 1942 around the major European ports and in the French region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, with the building of submarine bases, batteries, garrison bunkers and radar stations. The work was carried out under the auspices of the Todt Organization, but was of varying quality – the submarine bases being the best fortified – and by the end of 1943 the objective of 15,000 concrete structures was far from complete, with only eight thousand structures erected.

In January 1944, German Field Marshal Rommel, now in charge of defences in the west, was tasked with inspecting the Atlantic Wall along the French coast. He quickly discovered the system’s shortcomings, and in the space of just a few months Rommel constructed more than 4000 structures and 500,000 assorted obstacles on the beaches and in the interior zones.

Before D-Day in June, 2000 structures, 200,000 obstacles and two million mines were installed along the beaches and inland Normandy. Twenty-three German batteries were operational. Among these, the batteries of Saint-Marcouf, La Pointe du Hoc, Longues-sur-Mer and Merville presented real problems for the Allies.

There has been talk of declaring the remains of the Atlantic Wall a French national monument, but so far nothing has come of this. Some fortifications have been preserved and are open to the public, notably at the Grand Bunker Atlantic Wall Museum on Sword Beach.

Despite unstable weather conditions and fierce resistance from German units, Overlord maintained its element of surprise until the last minute, and the operation was largely successful. On the evening of 6 June 1944, while not all objectives had been achieved, the Allies had gained a foothold on all five beaches: the invaders were established before the German troops could mount a counterattack.

Today, the shore of Calvados department is still called the D-Day coast, and the beaches have retained their codenames. For the most part, the shore consists of innocuous beaches backed by gentle dunes; it is hard to imagine that this small strip of Europe was won at the cost of 10,000 Allied casualties. There are a great number of memorials, monuments, museums and other sites connected to the events of 1944 that can be visited today.

An essential preliminary to the D-Day landings was an airborne assault on the defences of Normandy during the night of 5–6 June 1944. The 82nd and 101st US airborne divisions were tasked with establishing a bridgehead on the western flank of the Allied assault area, behind Utah beach. Under the cover of darkness, 13,348 paratroopers jumped from 821 Douglas C-47 planes, while 4400 more soldiers were transported in gliders. Their mission was to support the American infantry troops when they landed at Utah Beach and to help take Cherbourg as fast as possible.

Credit: Shutterstock

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was a distinguished German commander, charged with improving the fortifications of the “Atlantic Wall” in 1944. In early June, Rommel drove to Germany to celebrate his wife’s birthday; on 6 June, while he was away, the long-awaited Allied invasion was launched. Rommel’s absence from the theatre of war until late in the afternoon on D-Day was an unexpected stroke of good luck for the Allies.

By D-Day, Rommel had come to believe that the war was unwinnable and would lead to the destruction of Germany. He became sympathetic towards the 20 July plot (of the same year) to assassinate Hitler, though his exact role in the events remains uncertain. Three days before the plotters struck, Rommel’s car was touring the front line when it was strafed by a Spitfire. Rommel sustained a head injury in the attack.

Whatever Rommel’s involvement, the 20 July plot failed spectacularly. Convalescing at home in Germany, Rommel was arrested and given the choice of facing trial or committing suicide by cyanide and saving his family honour. He chose the latter, and duly killed himself on 14 October 1944.

The 82nd Division, led by General Matthew B. Ridgway, was tasked with taking Sainte-Mère-Église, a village on the main road linking Caen to Cherbourg – the thoroughfare was deemed a likely route for a German counterattack. The paratroopers also blew up a number of bridges to prevent German reinforcements coming in from the south. Other strategically located bridges were protected for future Allied military operations.

The 101st Airborne Division, under General Maxwell D. Taylor, was to secure a safe exit for troops from the landing beaches. Units of this division also conducted raids against inland targets, including the German gun battery in Saint-Martin-de-Varreville and a number of bridges leading to Carentan.

As the transport aircraft closed in on the French coast, scouts marked out six drop zones with beacons and lights. This approach was successful in just one of these sectors: most paratroopers landed outside the designated areas, and chaos ensued as the different units tried to link up. Regardless, the two US airborne divisions accomplished most of their missions; most importantly, Sainte-Mère-Église was liberated in the early hours of 6 June. In the afternoon, the Germans staged a counterattack, but the lightly armed airborne troops held out until the next day when they were reinforced by tanks from nearby Utah Beach.

14 rue Eisenhower, Sainte-Mère-Église, ![]() airborne-museum.org

airborne-museum.org

This museum is essentially dedicated to the memory of American paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st airborne divisions who were dropped over the base of the Cotentin peninsula during the night of 5–6 June 1944. Its vast collection of uniforms, weaponry and other military memorabilia includes an example of the famous troop transportation plane, the Douglas C-47 (also known as “Skytrain”), as well as a Waco glider – the only such specimen surviving in France. A legendary American training and reconnaissance plane known as the Piper Cub has pride of place in the hall of the museum’s extension.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

Displays at the Airborne Museum in Sainte-Mère-Église

D-Day Experience (Dead Man’s Corner Museum)

2 village de l’Amont, Saint-Côme-du-Mont, ![]() dday-experience.com

dday-experience.com

The D-Day Experience is located on a strategic crossroads (Dead Man’s Corner) that was fiercely contested on 6 and 7 June 1944. The “Dead Man” in question is Walter T. Anderson, a tank commander whose lifeless body was exposed for all to see while fighting continued around him.

The 101st Airborne Division landed behind German lines just after midnight on 6 June, making them the first Allied soldiers to step foot on French soil. These men would fight for 33 consecutive days of the coming battle. One of the division’s first missions was taking Carentan, an essential gain so that tanks would be able to move inland from Utah Beach. St-Côme-du-Mont, the last village before Carentan on the N-131 main road, was defended by an entrenched outfit of Luftwaffe paratroopers who had been ordered to hold their position at all cost. When the first American tank reached the St-Côme-du-Mont intersection and turned towards Carentan, it was hit in the turret by a German rocket. The tank was incapacitated, while its commander hung dead from its hatch; he remained like that for several days as the battle raged.

Today’s museum contains a large collection of German and American paratrooper memorabilia.

One of the essential missions of the 82nd Airborne Division was to take the bridges spanning the Merderet river and those of Chef-du-Pont, all located west of Sainte-Mère-Église. Between 6 and 9 June 1944, the area around Merderet – swampy land purposely flooded by the Germans – was the setting of several brutal battles.

Credit: Liberation Route Europe

Utah Beach today

On 6 June, at daybreak, a company belonging to the US 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), along with soldiers from the 507th and 508th regiments, stormed the manor of La Fière and the bridge over the Merderet river. By the end of the afternoon, German forces, though backed up by tanks, had failed to recapture the bridge. Over the following two days German forces counterattacked repeatedly, but in spite of a lack of ammunition, the American soldiers stood their ground. On 9 June, General James Gavin led a bloody assault through the flooded areas to take control of the road and secure it. Supported by tanks from Utah Beach, American paratroopers managed, finally, to take the village of Cauquigny; the victory put an end to the battle of the Merderet river.

A statue was erected in 1961 to pay tribute to the American paratroopers and infantry men who lost their lives here, baptized “Iron Mike”. A similar statue can be seen in Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where the 82nd Airborne Division was – and still is – based.

Utah Beach was the codename for D-Day’s westernmost landing beach, on the east coast of the Cotentin peninsula, which stretches from Sainte-Marie-du-Mont to Quinéville. Here, the US 4th Infantry Division came ashore with the task of establishing a bridgehead at the base of the peninsula, an important assignment in the Allied effort to seize the deep-water port of Cherbourg as quickly as possible. Airborne troops, dropped overnight, cleared the enemy positions that threatened the exits from the beach.

The German strongpoint on the beach at La Madeleine, composed of various shelters and bunkers, a grenade launcher and four cannons designed to withstand tanks, was damaged by the air and naval bombardments of D-Day to such an extent that it offered little resistance to the American assault forces. Although many units landed nearly 2km southeast of their designated areas, creating much confusion, the operation was declared a success by nightfall, with relatively few American casualties.

Utah Beach became especially important after D-Day as a place to land equipment and other supplies. From June to November 1944 an endless stream of men and materials arrived in France via Utah Beach. In total, forty percent of all American troops brought to northwest Europe (836,000 men) came ashore here, along with 223,000 vehicles of all sizes and 725,000 tons of supplies.

Plage de la Madeleine, Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, ![]() utah-beach.com

utah-beach.com

The Utah Beach D-Day Museum stands on the site of the former German strongpoint that was eliminated by the US assault force on 6 June 1944. Today, it displays a wide range of German and American military items related to the landings. The 4th US Infantry Division and its 8th Infantry Regiment – the first men to touch down on the beach – are specially emphasized, but attention is also paid to the US Corps of Engineers that cleared the beach of dangerous obstacles and traps set by the German forces. Space is also reserved for the 101st US Airborne Division, which liberated the area of Sainte-Marie-du-Mont where the museum stands. A real highlight, and the central exhibit of the museum, is a rare Martin B26 G “Marauder”, an American twin-engined medium bomber of which no more than six survive today.

Credit: Utah Beach D-Day Museum

Edwin van Wanrooij

Route des Manoirs, Saint-Marcouf-de-l’Isle, ![]() batterie-marcouf.com

batterie-marcouf.com

During the occupation of France, the German Navy set up a huge battery of 210mm guns in Crisbecq, a small village located in the Saint-Marcouf district. The battery represented a real danger for the ships transporting American troops to the Utah Beach landing areas, and it was bombarded by Allied aircraft in the early days of spring 1944, as well as during the night of 5 June. Suffering little damage, the battery opened fire on the Allied naval forces on the morning of D-Day. In the ensuing artillery exchange the fleet succeeded in knocking out three of the German guns, but the gunners aimed their remaining cannon towards Utah Beach itself. Many American soldiers from the 22nd Infantry Regiment (4th Division) died in a vain attempt to take the German position. The four hundred German soldiers commanded by German Naval Lieutenant Walter Ohmsen stubbornly resisted the American ground troops and paratroopers over the coming days, before finally withdrawing on the night of 11 June.

Credit: Liberation Route Europe

Omaha Beach

The battery museum comprises a number of fortified buildings, typical of the structures of the Atlantic Wall, as well as anti-aircraft guns, machine guns and a kitchen for the use of German personnel. Although the large guns have been removed, visitors can probe a wealth of military paraphernalia, including weapons and uniforms. The battery also gives a good insight into the living conditions of German soldiers before the Allied landings.

Everyday civilian life under German occupation is the main focus of this museum, which has a reconstructed street complete with shops, an Atlantic Wall bunker, a cinema and scenes populated by 75 life-sized wax figures.

D-Day is chiefly remembered for its success, but one beach stands out for its near catastrophic failure. American troops landing on this 6km strip of shore had to contend with German defences that were still virtually intact, and suffered by far the highest losses of D-Day: 4700 killed, wounded or missing. It didn’t take long for the survivors to dub this beach “Bloody Omaha”.

The two US infantry divisions that landed here from 6.30am onwards (the 1st Division on the eastern half of the beach and the 29th division on the western half) both came ashore under heavy fire; the first two assault waves were decimated within a few minutes. Engineer battalions responsible for clearing the beaches of obstacles also suffered heavy losses. Amidst the chaos, small groups were still able to infiltrate between the German fortifications and gain a foothold inland. On the evening of D-Day, however, the situation was still precarious.

Several factors help explain the heavy losses at Omaha. Preparatory bombardments had failed to clear the German defences, which in turn protected higher numbers of German troops than the Allies had anticipated. On D-Day itself, Allied landing craft unloaded their human cargoes too far out; soldiers had to wade unprotected for several hundred metres through water that came up to their waists, while the amphibious tanks that would have offered the infantry at least some protection in the early stages of the assault struggled to get ashore, some sinking completely in the rough seas. With little support and a taxing battle to reach the beach, the Allied invaders made easy targets for the German guns. Inhabiting fifteen strongpoints called Widerstandsnester, the Germans were perfectly placed to fire mercilessly on Omaha. Standing on the hillsides above the beach today, it is easy to understand why the Allied forces faced such devastating odds.

By late 1942, the Germans had installed an artillery battery at Pointe du Hoc, a prominent cliff overlooking the English Channel. Composed of six 155mm guns positioned in open concrete gun pits (later under casemates), this battery was able to cover the beaches that had been selected for the landing of American troops: Utah Beach to the west and Omaha Beach to the east. Aware of the threat, the Allies bombed the battery many times before the landing. To ensure its complete destruction, they entrusted the task of scaling the cliff, seizing the fortifications and disabling the guns to the 2nd US Ranger battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder.

On the morning of D-Day, after a perilous ascent with rope ladders and grappling hooks, the US commandos clashed with German gunners; only when they had overcome the defenders did the rangers realize that the gun bunkers were empty and the guns missing. A short search revealed the guns hidden in a sunken road nearby.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

Pointe du Hoc

Since 1979, the conservation of this site, threatened by coastal erosion, has been assigned to the American Battle Monuments Commission. Considerable work has been undertaken to allow the public to visit. Amid the lunar landscape created by bombs and large-calibre shells, one can distinguish several concrete buildings: shelters for staff, anti-aircraft artillery positions, bunkers and cannon and ammunition pits. Above the fortifications, at the cliff edge, an impressive memorial offers a splendid view of the coast.

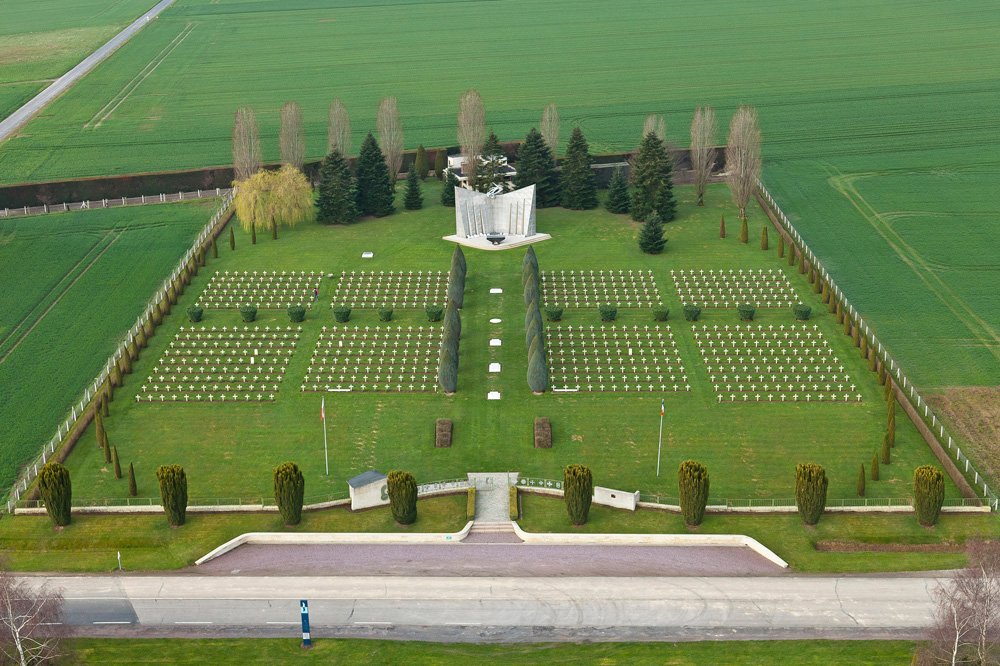

Of the six German military cemeteries in Normandy, La Cambe, with 21,200 graves, is the largest and best known. The other German cemeteries are found at Champigny/Saint-André-de-l’Eure, Mont-de-Huines, Marigny, Orglandes and Saint-Désir-de-Lisieux. In total, the remains of 80,000 German soldiers are buried in Normandy; some died before the Battle of Normandy, others in captivity after it. La Cambe dates from the summer of 1944, when the US Army established two temporary cemeteries on the battlefield near the village of La Cambe, one reserved for US soldiers, the other for German troops. After the war, the American Battle Monuments Commission decided to move the remains of the US soldiers to the cemetery of Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

La Cambe German Military Cemetery

In the 1950s, the administration of German cemeteries was entrusted to the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge, a private humanitarian organization charged by the Federal Republic of Germany with taking care of the German war dead abroad, under the motto “Versöhnung über den Gräbern” or “reconciliation over the graves”. Like other German military cemeteries from World War I and II, La Cambe reflects the status of the defeated. The crosses and headstones are hewn of dark stone, in accordance with a convention that the Treaty of Versailles had already established in 1919 for World War I cemeteries. The bucolic character of the present cemetery urges visitors to remember to live in peace.

Lotissement Omaha Center, Colleville-sur-Mer, ![]() overlordmuseum.com

overlordmuseum.com

Tanks, guns, posters, signs, uniforms, documents, personal items and even a V1 flying bomb are all part of this extraordinary collection. It was gathered together by the late Michel Leloup, who was 15 at the time of D-Day and became fascinated by the history of the liberation of Normandy.

Long lines of white marble Latin crosses and stars of David mark the graves of 9380 US soldiers who died in Normandy, particularly in the savage conflict on nearby Omaha Beach. There are no individual epitaphs, just gold lettering for a few exceptional warriors. A half circle of columns, elaborate statuary and a great reflecting pond combine to make a lasting impression, while a semi-circular wall on the east side of the memorial records the names of 1557 soldiers missing in action, whose bodies were not found, let alone identified. Large maps and commentaries in the loggias explain the Allied operations in Normandy and northwestern Europe; an orientation table shows the strategic movements of troops during the first days of the invasion; and a vantage point offers a sweeping panorama of Omaha Beach. A second American Cemetery in Normandy is situated just outside the town of Saint James.

The central beach of the D-Day invasion, between La Rivière and Le Hamel, was nominated Gold Beach and assigned to the British XXX Corps. Because of differences in the tide, troops landed here nearly an hour after the Americans on the beaches to the west. Soldiers disembarking on Gold had a relatively easy time – certainly compared to Omaha – losing 413 (killed or wounded) of the 25,000 men that made it ashore, aided by tanks equipped with flails which were able to clear a path through the minefields. By evening, the XXX Corps had taken Arromanches and penetrated the suburbs of Bayeux. They were able to join up with the Canadians coming from Juno Beach, but not with the Americans from Omaha – that would take three more days. Gold was particularly important to the Allied invasion planners because it was here that they were to install a floating Mulberry Harbour, an innovation which would prove vital for supplying the armies moving inland.

The German artillery battery at Longues-sur-Mer was perfectly located to oppose the landings of 6 June 1944. Installed slightly back from the edge of a sixty-metre-high cliff, it sat directly opposite the Allied fleet, and right between Omaha and Gold beaches. The battery consisted of four 150mm guns in concrete bunkers, plus one 120mm gun. Still under construction in May 1944, the battery was operational but the firing command post on the edge of the cliff did not yet have all the equipment necessary for calculating effective fire against naval targets.

On D-Day, the Longues-sur-Mer battery engaged in a protracted duel with the Allied fleet, forcing a number of its vessels to retreat. However, the five guns of the battery were gradually silenced, some destroyed by direct hits. Finally, British troops landing at Gold Beach took the battery on 7 June, capturing the survivors of the battery’s 180-strong garrison. Today, the German battery constitutes one of the best-preserved World War II military sites in the country, and is the only one where you can still see some of the original cannons, capable of firing shells weighing 45kg over a staggering 22km. The view from the firing command post, dug into the cliff, offers a vast panorama over the Bay of the Seine.

Place du 6 Juin, Arromanches-les-Bains, ![]() musee-arromanches.fr

musee-arromanches.fr

The first Normandy museum built to commemorate the events of 6 June 1944 (and onwards), the D-Day Museum was funded by the sale of the wrecks that once littered the coastline, and was inaugurated on 5 June 1954. It is located in front of the former artificial port – or Mulberry harbour – that facilitated the landings of two and a half million men and half a million vehicles. A model inside the museum explains how the port facilities were constructed and used, while a film retraces the stages of design, construction and assembly. Vivid photographs evoke the storm of 19–22 June that nearly destroyed the artificial port. Behind the museum and on the beach, visitors can see the metal remains of the harbour’s floating road.

›› The artificial harbour of Arromanches

While planning the invasion of Normandy (Operation Overlord), Allied command considered it absolutely necessary to have deep-water ports – such as Cherbourg – in order to dispatch reinforcements to the continent. The Canadian assault against Dieppe on 19 August 1942 had shown how thoroughly German command had fortified the ports of the Atlantic coast; they could not be captured without significant loss of life and the harbour facilities would be reduced to ruins in the process.

The ingenious solution of the Allied staff was to manufacture the components for two artificial ports in Britain, to be towed across the Channel and assembled on site. One of them was planned off the American landing zone of Omaha Beach (Vierville-sur-Mer), codenamed Mulberry “A”, the second (Mulberry “B”) at Arromanches off Gold Beach, a British landing zone.

The 50th British Infantry Division that landed on Gold Beach on 6 June captured Arromanches that same evening. The next day, construction of Mulberry B began. First, a line of floating outer breakwaters (cruciform metal boxes called bombardons) were deployed; next, a pier was constructed by scuttling redundant freighters on the site. The structure was completed by an alignment of huge concrete caissons, each weighing 1600–6000 tons. The caissons, built in Britain, were towed across the Channel and lain on the seabed. Finally, the surface elements of the harbour were put into position: floating docks and roadways were designed to rise and fall by several metres with the tide.

On 14 June, the first floating road was operational. However, a storm swept through the Channel from 19 to 22 June, damaging the ports. Mulberry A turned out to be completely unusable, though some of its surviving elements were used in repairing Mulberry B, which was less heavily damaged.

In total, the Mulberry harbour at Arromanches functioned for ten months, bringing ashore more than four million tons of supplies. The project was a remarkable technological feat, but with hindsight the endeavour was judged unnecessary and exceedingly costly. The Allies managed to land more men, vehicles and goods by way of a number of small Normandy ports, and even directly onto the beaches. The remains of the floating harbour of Arromanches are still visible today as silent witnesses to this bold gamble and stunning technical achievement.

The stretch of beach from Graye-sur-Mer to Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer (including the towns of Courseulles and Bernières) was assigned to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, led by Major General Rod Keller. Success here was not guaranteed; several issues played out on D-Day morning and the Canadian troops were pitted against determined German opposition. Initial naval bombardment had not been effective, and stormy seas caused delays in landing craft reaching the shore, allowing the Germans, holed up in their bunkers, to organize serious resistance. Many landing craft were hit by gunfire or damaged by underwater obstacles. The Canadian assault units nevertheless succeeded – with tank support – destroying the German positions one by one.

Fighting was particularly heavy at Bernières, and even more so at Courseulles, a small but heavily defended port at the mouth of the Seulles. It was in Saint-Aubin, however, that combat was fiercest. It took a good part of D-Day to neutralize a 50mm gun overlooking the beach, protected by field-fortifications (felled trees) blocking the narrow streets of the village. Saint-Aubin was finally secured during the night of 6 June.

Dogged German resistance led to congestion at the few beach exits. Hampered by the build-up of vehicles, Canadian troops still managed to advance deep inland; they made remarkable progress on D-Day at the cost of 961 casualties (including 319 killed). The following day, their advance was cut short northwest of Caen by the arrival of German armoured reinforcements.

Several VIPs landed on the west beach of Courseulles in the days after D-Day: Winston Churchill on 12 June; General de Gaulle on 14 June, en route to Bayeux; and King George VI, who visited the British troops on 16 June.

Voie des Français Libres, Courseulles-sur-Mer, ![]() junobeach.org

junobeach.org

More than a museum dedicated to the landings on D-Day, the Juno Beach Centre remembers the sacrifice of a nation: it recalls Canada’s contribution to World War II and the Liberation. The modern museum stands opposite the beach in Courseulles-sur-Mer, on the site of a German strongpoint that protected the harbour entrance and which the 3rd Canadian Division successfully neutralized on 6 June 1944.

Canada entered the war alongside the United Kingdom in September 1939 and made a considerable effort to mobilize its economic and human resources. More than one million Canadians fought for the Allied cause and more than 45,000 lost their lives. At the end of World War II, Canada was transformed, but its national unity remained intact.

The Juno Beach Centre provides a comprehensive overview of Canada’s role in the war through six thematic showrooms. An emotive film, entitled “Dans leurs pas” (“They walk with you”), allows visitors to follow the story of an individual Canadian infantryman.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

Juno Beach Centre

The Canadian War Cemetery called Bény-sur-Mer (but actually located in the town area of Reviers) overlooks Juno Beach. It contains the remains of more than two thousand Canadian soldiers who fell during the first weeks of the Battle of Normandy, notably during the bloody confrontation with the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend before the liberation of Caen on 9 July.

A second Canadian cemetery in Normandy is located in Bretteville-sur-Laize, south of Caen. It is the final resting place of 2800 Canadian soldiers killed during the very laborious advancement of the 2nd Canadian Corps towards Falaise between July and August 1944.

Route de Basly, Douvres-la-Délivrande, ![]() musee-radar.fr

musee-radar.fr

The Radar Museum in Douvres was built on the grounds of a former bunker and – as its name suggests – tells the story of radar during World War II. A new and innovative technology, radar was used by both the Allies and the Axis, particularly by their air forces and navies. Exhibitions also detail life in Douvres during the Nazi occupation, the Liberation and local de-mining operations.

In the early hours of D-Day, the British 6th Airborne Division, under Major General Richard Gale, was dropped behind the German coastal defences of Sword Beach. Its mission, known as Operation Tonga, was to protect the left flank of the landings by gaining control of the area between the Orne and Dives rivers. But that night, with thick clouds impairing the visibility of its pilots, a strong easterly wind scattered the paratroopers over an erroneously large area, causing widespread confusion.

The parachutists were to capture two strategic bridges crossing the Orne River and the Caen Canal; these were taken after just minutes of intensive fighting by five glider crews that had landed close by. The division destroyed several more bridges over the Dives river in a bid to prevent or delay a German counterattack, before attempting to neutralize the German artillery battery of Merville, which would threaten British troops landing on Sword Beach at dawn. The battery was disabled only after fierce combat – which witnessed a casualty rate of fifty percent.

Despite the chaos that surrounded the British airborne landings, all the objectives of Operation Tonga had been achieved when day broke on 6 June, but at a high price.

British airborne landings sites

Place du 9ème Batallion, ![]() battery-merville.com

battery-merville.com

Just after midnight on 6 June 1944, a battalion of the 6th British Airborne Division was deployed to destroy the four large guns of the German battery at Merville before they could be used against the landing forces on Sword Beach. Allied intelligence suspected the German battery could greatly hinder the advance of the landing troops as they made their way inland. British Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway and his 9th Parachute Battalion were tasked with carrying out the daring mission to storm the battery, surrounded by barbed wire, land mines and machine gun nests.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

Memorial Pegasus tableau

Of the 750 paratroopers who were dispersed in the air, only 150 managed to assemble on the ground. Despite lacking much of their equipment, they went ahead with the assault, and after a half-hour the battery was theirs. Nearly half of the British paratroopers were killed or wounded; of the 130 German soldiers defending the battery, just one quarter survived. Only when the site was taken did it become clear that the intelligence services had overestimated the calibre of the cannon.

A Franco-British partnership founded the Merville Battery Museum in 1983. One of the four emplacements has been fitted with a 100mm field howitzer, identical to the one deployed in 1944. Inside the museum area, visitors can also admire a Dakota plane used in the airborne assaults on 6 June.

Av du Major Howard, Ranville, ![]() memorial-pegasus.org

memorial-pegasus.org

For the 6th British Airborne Division, the most important mission on 6 June 1944 was to capture the twin bridges that crossed over two parallel stretches of water – the Canal de Caen and the Orne river – intact. This would enable the troops on Sword Beach to proceed rapidly east of the Orne. D-Day preparations were shrouded in secrecy and the element of surprise was key; this mission marked the first Allied action in the British sector.

A company of the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, commanded by Major Howard and reinforced by sappers, was deployed at 12.20am near the two bridges. One of the six gliders landed a dozen kilometres from the objective, but the other five accurately deployed their assault detachments. At the bridge over the Canal de Caen, the better guarded of the two crossings, Allied troops surprised the small garrison and emerged victorious after a brief but vicious engagement. The bridge over the Orne river, guarded by two German sentries, was taken without a shot being fired. Reinforced by further parachutists during the night, Howard’s men were joined in the early hours of the afternoon by the commandos of the 1st Special Service Brigade, who had landed at dawn on Sword Beach.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

Canadian Memorial at Juno Beach

Replaced in 1994 to accommodate river traffic, the original bridge (nicknamed Pegasus Bridge) is the focus of the Memorial Pegasus museum. Inside the vaguely glider-shaped building, informative boards explain the attack in detail, accompanied by the expected array of helmets, goggles and medals, as well as photographs and models used to plan the assault. A life-size replica of an Airspeed Horsa glider is also exhibited.

Sword was the codename for the easternmost of the five landing beaches, from Langrune to Ouistreham. The objective at Sword was ambitious: troops coming ashore were to protect the left flank of the Allied bridgehead in Normandy – in liaison with the 6th Airborne Division which had landed overnight between the Orne and Dives rivers – and to seize the strategically important city of Caen, 15km inland.

The assault on Sword was led by the 3rd British Infantry Division, reinforced by the commandos of the 1st and 4th Special Service Brigades and supported by specially adapted tanks. The commandos neutralized the German strongpoints by attacking them from two sides. After clearing Ouistreham of hostile units, the 1st Special Service Brigade was able to join up with the paratroopers at Bénouville and take up position on the east bank of the Orne. In contrast, the commandos due to connect with the Canadians from Juno Beach failed to make their rendezvous; they were attacked by the 21st German Panzer Division, which lost fifty tanks in the resultant battle.

Congestion on Sword Beach, and determined resistance by several German strongpoints further inland, prevented the British from capturing Caen on 6 June as they had hoped. More than a month of fighting would ensue before the liberation of Caen, which finally fell to the Allies on 9 July 1944.

Grand Bunker Atlantic Wall Museum

Av du 6 Juin, Ouistreham, ![]() museegrandbunker.com

museegrandbunker.com

Housed in a lofty bunker, the Atlantic Wall Museum was headquarters to several German batteries, controlling the entrance to the Orne river and the canal connecting Caen to the sea. It fell to Allied forces on 9 June 1944. The 17-metre-high concrete tower has since been fully restored to its D-Day appearance.

Only rarely does a military unit assume the name of its commander, but the Commando Kieffer owes its name to Philippe Kieffer, a New York City banker of French nationality. In 1939, at the age of 40, he volunteered as an officer in the Free French Naval Forces, serving at Dunkirk. After the Fall of France in 1940, Kieffer became bored with his administrative duties in London, and was inspired by the British commandos to set up a similar elite French force. Kieffer commanded the only French unit to take part in D-Day, landing on Sword Beach. He was wounded and evacuated to England on 8 June, but returned to take part in the Battle of Normandy, and was one of the first French soldiers to enter liberated Paris. In a tragic twist of fate, at almost the exact same time, Kieffer’s eighteen-year-old son, fighting with the resistance, was killed in action near the French capital.

The six floors of the Grand Bunker have been recreated to show what the living quarters would have been like, with newspapers, cutlery and cigarette packets adding a human touch to the explanations of the generators, gas filters and radio room. Other rooms to explore include the dormitory, medical store, sick bay, armoury and arsenal; there’s also an observation post equipped with a powerful range-finder. The top floor offers a fabulous 360-degree panorama across Sword Beach and the Bay of the Seine.

Atmospheric photographs, historic documents and weathered items explain the construction of the Atlantic Wall; its artillery and the beach defences are also covered, as are the tactics used by specially trained shock troops who had to find a way through the Wall.

By nightfall on 6 June 1944, the Allied forces had established a foothold on all five landing beaches. Some troops had even advanced a little way inland, but they had not yet completed the objectives set by their commanders.

At the end of D-Day, the Allied situation was still critical. Forces continued to work on establishing a continuous 80km beachhead along the coast, which was vital for moving further into Normandy. The Allies had underestimated the task, however, and for days the Allied territory in France was unstable and uneven along its coast.

The Allied and Axis forces found themselves locked into a deadly race of strategy and logistics. The battle for possession of Normandy, France and ultimately the European continent was still far from decided. For the Allies, the task was simple: to land sufficient men and weaponry quickly enough to fend off the inevitable German counterattack.

The challenge for the Germans was more complex. In the early days of the invasion, they had more personnel and firepower than the Allies, but this didn’t always translate onto the battlefield. Failing to comprehend the gravity of the situation, the German forces were still concentrated in Pas de Calais, where they expected the “real” Allied invasion to come – where the English Channel was at its narrowest. Two further Panzer divisions were in reserve near Paris and could not be moved without express orders from Hitler’s headquarters. The delay in releasing these crucial reinforcements gave the Allies valuable time to even the odds.

The Allied advance was propelled by the construction of a huge artificial harbour at Arromanches, a provisional arrangement which allowed them to disembark troops and equipment. Capturing the deep-water port of Cherbourg was still important, as was taking the city of Caen, which was of prime strategic value – but which would prove difficult and bloody to liberate.

Fighting in early July 1944 in the Normandy bocage – a fragmented countryside of small fields and orchards divided by leafy hedges and sunken lanes – saw heavy Allied losses. The terrain favoured the German army, being ideal for defensive guerrilla tactics and the operation of snipers. German troops, firmly dug-in, were difficult to see and could pick off Allied soldiers at point-blank range. The high hedges, boggy earth and enclosed fields all caused problems for a modern land army, and rendered the Allied tanks almost useless. The improvisation of front-mounted blades to cut through the hedges eventually paid off, but the Battle of Normandy was an often exhausting process of foot soldiers engaged in close-quarters combat, advancing field by field, orchard by orchard.

Famous for its extraordinary tapestry showing the conquest of England, the town of Bayeux, 10km from the coast, was the first French city to be liberated on 7 June 1944. Taken so quickly that it escaped serious damage, it briefly became capital of Free France.

The real prize, however, was the deep-water port of Cherbourg, located in the American sector at the end of the Cotentin peninsula. For the Allies, this was a vital gateway to Europe, indispensable for supplying their campaign as it progressed towards Germany. Commandeering the port would enable Allied ships to unload directly in mainland Europe.

After US troops landed on Utah Beach, the Germans blocked the road to Cherbourg. Montebourg was conquered after a bitter offensive, but was almost completely destroyed in the process. On 18 June 1944, American forces reached Barneville, on the west coast of the Cotentin, leaving 40,000 Germans trapped on the peninsula to the north. Some of them surrendered, but the majority retreated around Cherbourg. The Americans rushed towards the city, where they met heavy resistance.

Mass bombings by Allied aircraft and warships weakened the German defences at Cherbourg, and on 26 June the Americans managed to seize Fort du Roule, an imposing citadel clinging to a hillside overlooking the harbour. On the same day, German General von Schlieben, commander of Cherbourg, surrendered to US General Collins. The city was almost intact, but the port facilities had been completely destroyed by the Germans; extensive emergency repairs were started, and the first American ships graced the harbour in late July.

Credit: Getty Images

American troops landing in Normandy

Caen, capital of Calvados department and the largest city in the proximity of the D-Day beaches, was completely devastated during the fighting of 1944. As an essential road hub, strategically straddling the Orne river and Caen Canal, the city was the main objective for the British 3rd Infantry Division that landed on Sword Beach.

Firmly positioned to the north and west of the city, two Panzer Divisions prevented the Allies from capturing the city in the first two days. General Bernard Montgomery attempted to take Caen by pincer movement, attacking the city from the northeast and southwest. On 13 June the offensive was stalled in Villers-Bocage by German Tiger tanks. A further attack was planned using the British 8th Corps. Operation Epsom brought together 60,000 men who tried to outflank the defenders of Caen by crossing the Odon river, but within a few days the offensive was stopped at the foot of what was dubbed Hill 112.

A few weeks later, Montgomery decided to capture Caen in a frontal attack codenamed Charnwood. On 7 July, the city was bombarded by 450 bombers of the Royal Air Force; a total of 2600 tons of bombs were dropped, resulting in the tragic deaths of 300 civilians. On the morning of 8 July, 115,000 men and 500 tanks of the British 1st Corps attacked. British and Canadian troops reached the bridges of the Orne on 9 July. The left bank of the river was liberated, together with the Ilot Sanitaire, an emergency hospital and refuge, which sheltered some 20,000 civilians.

Credit: Getty Images

British soldiers in Normandy, 1944

Montgomery launched Operation Goodwood to capture the right bank of the river, and at dawn on 18 July, 6000 tons of bombs were dropped over eastern Caen. Operation Atlantic, a simultaneous mission entrusted to the Canadians, helped liberate the town entirely on 19 July 1944. Allied planners, who had believed the city could be taken in one day, had been bitterly ambitious. It was a Pyrrhic victory, with a devastating toll: 30,000 British and Canadian soldiers dead; eighty percent of the city destroyed; and three thousand of its inhabitants killed.

The Allied breakout of late July

Control of Cherbourg and Caen meant that the Allies could now contemplate extending their operations to the rest of Normandy. Having established superiority over both land and air, the Allied plan was to outflank the German army to the south before swinging east to advance across northern France. Saint-Lô was captured by the US Army on 19 July after a bitter struggle. The campaign – suspended for the next week because of bad weather – resumed with Operation Cobra on 25 July, which successfully broke through the German lines. Coutances and Granville were liberated and on 31 July, the reactivated US Third Army under General Patton took the vital centre of Avranches, giving the Allies access to Brittany and the rest of western France. An unsuccessful German counterattack failed to cut the Third Army off from its supply lines as they’d hoped, and the Wehrmacht was forced to retreat east, regrouping to plan another defensive against the Allied advance.

In mid-August 1944, Hitler ordered his Seventh Army to mount a stand. It did so in the historic town of Falaise in central Normandy, with disastrous consequences. Falaise was almost entirely destroyed, while the engagement became known as the Falaise Pocket because the German armies were almost completely encircled by the Allies. Hesitation by the Allied command delayed the final closure of the “pocket” until 19 August, when elements of the 1st Polish Armoured Division met the 90th US Infantry Division coming from the north at Chambois. Surrounded and shelled by Allied artillery, the Germans tried to make their way out of the trap by force, launching desperate attacks on the slopes of Mont-Ormel where they encountered Polish detachments. Both sides suffered heavy losses, but the few hundred Polish soldiers on Mont-Ormel held their positions.

The Battle of Normandy ended with the surrender of part of the German Seventh Army at Tournai-sur-Dive. German losses at Falaise were huge: about 10,000 killed and 40,000–50,000 captured. Despite winning the battle, the Allied victory was mitigated by the great number of German soldiers who escaped the trap – with their vehicles and weapons intact – to continue their retreat eastwards. Even so, the way was now clear to cross the Seine and enter Paris.

Place Guillaume le Conquérant, Falaise, ![]() memorial-falaise.com

memorial-falaise.com

Civilians rather than soldiers are the subjects of this Normandy museum, which looks at the lives of ordinary French people during World War II. On the ground floor, an immersive film of French, British and German archive footage – projected over the ruins of a real bombed house – transports you to the world of an air raid. The museum’s other floors deal with the occupation and Liberation.

Les Hayettes, Montormel, ![]() memorial-montormel.org

memorial-montormel.org

This memorial-museum stands on the high ground of the battlefield of Falaise, giving a fine view over the Vallée de la Dive. It tells the story of the Falaise-Chambois Pocket or “Corridor of Death”, beginning with the course of the Battle of Normandy and then covering the climactic events themselves. A meditation room allows for quiet reflection on the universal themes of war, life and death.

Fort du Roule, Cherbourg, ![]() ville-cherbourg.fr

ville-cherbourg.fr

Cherbourg, as the collection here explains, was exploited by the Germans as an Atlantic port, which made it a prime objective for the Allies following D-Day. Situated 117m above sea level, its Liberation Museum affords a stunning view of the harbour.

The largest British World War II cemetery in France holds the remains of 4000 British and 181 Canadian soldiers, as well as a number of Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Poles, Russians, French, Czechs, Italians and Germans. Many combatants buried here died in field hospitals to the southwest of town. British tradition prescribes that soldiers are buried with their comrades-in-arms close to where they died, which explains the wide dispersal of British military graves. In the department of Calvados alone, there are nineteen military cemeteries and nearly one hundred monuments. A memorial on the other side of the road bears the names of 1801 Commonwealth soldiers who died during the Battle of Normandy, and those whose remains could not be found or identified. A poignant inscription on the monument recalls William the Conqueror, the duke of Normandy who became king of England in 1066: “Nos a Gulielmo victi victoris patriam liberavimus” (“We, once conquered by William, have now set free the conqueror’s native land”).

Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy

Boulevard Fabian Ware, Bayeux, ![]() bayeuxmuseum.com

bayeuxmuseum.com

Right next to the British military cemetery, this museum relates the bloody ten-week Normandy campaign from the D-Day landings to the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht beyond the River Seine. Covering military strategy as well as what everyday life was like for soldiers and civilians, informative exhibits include mannequins, pictures and weaponry. In addition to the examples of armour outside the museum, a vast hall houses military vehicles and pieces of ordnance, as well as a diorama evoking the decisive struggle in the Falaise Pocket. An archive film recounts the battle in both French and English. The permanent exhibition also deals with aspects of military campaigns that are often ignored: feeding the troops, care for the wounded, logistics, communication and so on. The significant role played by the Allied air forces is remembered, too.

Bayeux was the first French city to be liberated – meriting a visit from Charles de Gaulle himself on 14 June 1944, a highly symbolic event recalled in the museum. His enthusiastic reception led the Allies – and especially US President Roosevelt – to recognize de Gaulle as the only legitimate leader of a free France. A pedestrian path connects to Bayeux’s other museums and to its magnificent cathedral, the first home of the Bayeux Tapestry.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

Flags fluttering outside the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy

Credit: Alamy

Polish Cemetery at Urville-Langannerie

Esplanade Général Eisenhower, ![]() memorial-caen.com

memorial-caen.com

Just north of Caen, the excellent, high-tech Caen Memorial Museum stands on a plateau named after General Eisenhower on a clifftop beneath which the Germans had their headquarters in June and July 1944. The German command post – 70m long and 5m wide – has since been restored.

Originally a “museum for peace”, the brief has been expanded to cover history since the Great War. It sets out to explain what happened in Normandy in 1944; to illustrate the scale of World War II, which ultimately led to the death of fifty million people (half of whom were civilians); and to place the war in context, from the end of World War I to its lingering consequences today. One of a kind in France, the museum asks pertinent questions about the nature of warfare, peace, remembrance and human rights.

A large space is dedicated to the varied individual experiences of men and women confronted with war: rationing, occupation, contribution to the war effort, life under aerial attack and direct combat. As the city of Caen knows intimately, violence against ordinary civilians is a grim reality of war, from urban bombing campaigns to reprisal massacres and horrific genocides.

The only Polish cemetery in the region contains 696 graves, mostly those of soldiers who died during the capture of Caen and in the battle to close the Falaise Pocket.

One of only six surviving Tiger Type E tanks in the world sits on the roadside outside Vimoutiers (on the road to Gacé). It was abandoned or broke down on 19 August 1944 – after which time it was rescued by a military enthusiast and given to Vimoutiers town council.

The iconic French capital was not a strategic target for the Allies, and US General Eisenhower considered it a distraction in his plans. He was thinking of bypassing it altogether as his Allied armies set out in pursuit of the Germans as they retreated eastwards across France.

Eisenhower was sensible to approach Paris with caution. If the city was defended with determination it might be destroyed for all-but symbolic gain, and the already overstretched Allies would have to feed a huge population of displaced people.

On 19 August 1944, the fate of Paris was decided by an uprising of Parisians and resistance fighters bent on liberating their city for themselves. The German garrison fought back to suppress the rebellion and the precarious situation could easily have degenerated into an uncontrolled guerrilla war of liberation and political feuding – one that risked spreading across the whole of France. Eisenhower couldn’t afford anarchy behind his lines or disruption to his carefully orchestrated military campaign.

The French also had a say in the matter. It was imperative they were seen to be taking an active part in liberating their capital. With a sense of historic prescience, de Gaulle disembarked at Cherbourg on 20 August, just as the last German troops in Normandy were surrendering to the Allies. Four days later, at dusk on 24 August, an outreach detachment of General Philippe Leclerc’s Free French 2nd Armoured Division drove into southern Paris virtually unopposed. The next morning his entire division entered the city.

What followed in the next few hours was to curiously echo the events of the summer of 1940, when the French and Germans decided against reducing the City of Lights to rubble. In August 1944, however, Hitler unequivocally ordered the German military commander of Paris, Lieutenant General Dietrich von Choltitz, to crush the insurrection and raze the city, as happened in Warsaw. If the Allies took Paris, it should be transformed into a prize not worth the effort of taking.

Choltitz chose to disobey his orders, refusing to destroy one of the great cities of European civilization. Instead, he yielded Paris intact, and on 25 August, US divisions crossed the Seine and joined Leclerc’s troops in clearing the last German pockets of resistance. The opposition was sporadic and ineffectual – mainly provided by Germans and collaborators who didn’t want to fall into Allied hands.

The city’s eastern suburbs were bombed, but otherwise Paris survived the war. Choltitz signed an instrument of capitulation and ordered his troops to surrender; the following day, de Gaulle led a victory parade down the Champs-Elysées from the Arc de Triomphe. Paris hadn’t been scarred by the Liberation, but there was still little light, heat and running water. Gradually normal life resumed, and the city became an administrative centre for the Allies, as well as a pleasure dome for soldiers on leave.

Army Museum and Historial Charles de Gaulle

Hôtel des Invalides, 129 rue de Grenelle, ![]() musee-armee.fr

musee-armee.fr

France’s Army Museum in the Hôtel des Invalides tells the story of the war and Liberation using memorabilia and stirring contemporary newsreels. In the basement, the “Historial de Gaulle” section plays a high-tech audiovisual tribute to the resistance leader and, later, president. A series of rooms are also devoted to the generals of the Free French forces: Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, Alphonse Juin and Jean de Lattre de Tassigny.

General Leclerc and Liberation of Paris Museum and Jean Moulin Museum

Place Denfert-Rochereau, ![]() museesleclercmoulin.paris.fr

museesleclercmoulin.paris.fr

Two essential figures of French history are celebrated at this museum, which recently relocated to new premises. On 25 August 1944 General Leclerc, commander of the 2nd French Armoured Division, drove into Paris, set up his command post in Montparnasse Station and organized the surrender of the city’s German garrison. Jean Moulin was the head of the National Council of Resistance. Arrested, tortured and killed in 1943, Moulin died without the knowledge that Paris would later be liberated.

17 rue Geoffroy l’Asnier, ![]() memorialdelashoah.org

memorialdelashoah.org

Since 1956 this memorial has occupied a sombre crypt containing a large black marble Star of David, with a candle at its centre. In 2005 President Chirac opened a new museum here and unveiled a Wall of Names: four giant slabs of marble engraved with the names of the 76,000 French Jews sent to death camps from 1942 to 1944.

The museum gives an absorbing and moving account of the history of Jews in France, especially Paris, during the German occupation. There are last letters from deportees to their families, videotaped testimony from survivors, numerous ID cards and photos. The museum ends with the Children’s Memorial, a collection of photos, almost unbearable to look at, of 2500 French children, each with the date of their birth and the date of deportation.

Credit: Shutterstock

Shoah Memorial

Credit: Getty Images

Charles de Gaulle served in World War I under Marshal Pétain, where he was wounded, taken prisoner at Verdun and decorated for his bravery. In the interwar years de Gaulle became an advocate for mobile, mechanized warfare and urged his government to rearm with tanks and planes. When the Germans invaded France in 1940 he was charged with an armoured division, but his talent for strategy was recognized and he was promoted to under-secretary of war.

De Gaulle stubbornly refused to accept the armistice that would lead to the creation of the Vichy government, led by his old commander, Pétain, and insisted that France should fight on, whatever the consequences. Keeping his intentions a close-guarded secret, de Gaulle chose exile over surrender, and flew to London – without any money or resources – to form a government-in-exile. While he was branded a traitor and officially sentenced to death in his absence, on 18 June 1940 he made a stirring radio broadcast, urging the French people not to lose hope. Courageous and single-minded, de Gaulle identified himself with the destiny of France, and obstinately defended his country’s interests in the face of Allied politicians and commanders who thought of France as defeated, weak and impotent. De Gaulle had a particularly conflicted relationship with the British; he needed their help to liberate his country but resented having to rely on it.

From London, de Gaulle instigated the formation of the Free French Forces (a rebuilt version of the French army) and the French Resistance (later renamed the French Forces of the Interior). On 20 August 1944 he landed at Cherbourg in time to reach Paris just after its liberation. Here he spoke to the French again, stressing the role of the Free French and all but ignoring the contribution of France’s allies. De Gaulle became the acting president of a unified government when the Vichy administration fled to Germany. He insisted on France taking an active part in both the conquest of Germany and the arrangement of the ensuing peace.

Following his instrumental role in World War II, de Gaulle was to become the dominating figure in French postwar politics, eventually becoming French president in 1959. He remained a military man, and although de Gaulle associated himself with the liberation of France, he took a somewhat authoritarian attitude towards democracy.

110–112 av Jean-Jaurès, Drancy, ![]() drancy.memorialdelashoah.org

drancy.memorialdelashoah.org

The Shoah Memorial in Drancy, a suburb of Paris, stands opposite the Cité de la Muette about 10km from the city centre. During World War II, the Cité de la Muette served as an internment camp for the Jews of France before their deportation towards extermination camps. Almost 63,000 people passed through Drancy on their way, principally, to Auschwitz–Birkenau. The memorial here traces the history and function of the camp, as well as the harsh daily lives of the interned.

Museum of the Order of the Liberation

Hôtel des Invalides complex, Boulevard de La Tour-Maubourg 51, ![]() ordredelaliberation.fr

ordredelaliberation.fr

In 1940, Charles de Gaulle created an award for people who participated in the liberation of France. Second only to the better-known Légion d’Honneur, the Order of Liberation was bestowed on fewer than 1500 people for their heroic deeds during World War II. The Hôtel des Invalides complex displays the collections of the Companions of the Order of the Liberation: two thousand objects and documents relate to the Liberation, the deportation of French citizens by the Nazis and the activities of the French Resistance.

228 rue de Rivoli, ![]() dorchestercollection.com

dorchestercollection.com

This no-holds-barred luxury hotel opposite the Tuileries was one of the key locations in the liberation of Paris. In August 1944 it functioned as the headquarters of Dietrich von Choltitz, the German military governor the city. Hitler is said to have phoned him here to make sure his order to destroy the city was being carried out. “Is Paris burning?” he demanded of Choltitz, who had decided that the preservation of the city was more important than the Führer’s command. When the Americans replaced the Germans, this and three hundred other hotels were used to accommodate their officers and offices.

88 av Max Dormoy, Champigny-sur-Marne, ![]() cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr

cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr

Almost every department of France has its own Resistance archive and centre of interpretation. This museum, in the southeast suburbs of Paris, attempts to present a coherent picture at national level from the inception of the resistance movement to the Liberation. Interesting displays include assorted photographs, documents, paintings and other wartime objects.

On 14 June 1940, German troops marched from the Arc de Triomphe down the-Elysées – then as now among the most famous streets in the world – to emphasize their unqualified victory after the Fall of France. On 26 August 1944 it was the turn of de Gaulle and the Free French Army, unperturbed by a lone, unidentified sniper firing on the crowd. De Gaulle delivered a rousing speech, praising his countrymen and women for freeing themselves of their Nazi oppressors, but barely acknowledging the contributions of his allies.

Winston Churchill and the British were bitterly opposed to an American plan to land an army on the French Riviera; they considered Operation Dragoon unnecessary and unlikely to yield worthwhile results.

The British believed an attack on Provence would sap vital resources from Italy. Men and equipment would both need diverting, putting an end to Churchill’s aspirations to invade Germany from the south. Moreover, if Dragoon succeeded, US troops would dominate the western European theatre of war. Invading Germany via Italy or the Balkans, Churchill argued, would disrupt German oil supplies and help to limit Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. As World War II drew to a conclusion, Churchill saw that military decisions like this would impact British, American and Soviet spheres of influence in postwar Europe.

Credit: Liberation Route Europe

Memorial of the Landing in Provence

The US commanders already held the balance of power, however, and Dragoon went ahead. Eisenhower was insistent that the Allies needed another port. Cherbourg had been captured but its harbour facilities needed rebuilding; Antwerp was so far unavailable; Marseilles, therefore, was the obvious place for Liberty ships to unload supplies for the American armies in eastern France and Germany.

The landings in Provence had initially been planned to coincide with Operation Overlord in Normandy, in order to stretch the Germans across two French fronts. The demands of launching two major invasions simultaneously were unmeetable, however, and Dragoon was rescheduled for 15 August 1944. The selected beaches – located between Hyères and Cannes – afforded many advantages to the Allies. Their ground troops were supported in the air and by members of the French Resistance, who, emboldened by the Normandy landings, carried out daring sabotage missions directed against General Johannes Blaskowitz and the German Army Group G, charged with the defence of Provence.

The thrust of the invasion was assigned to three divisions of the US VI Corps under Major General Lucian Truscott (part of the US Seventh Army, under Patch) supported by French Army B, led by General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny (usually referred to as de Lattre).

The landings met none of the problems encountered at Salerno or Normandy – only on the right flank was there any serious opposition – and 66,000 men were landed at the cost of less than one hundred fatalities. The French took the task of liberating Toulon and Marseille, which fell to the Allies on 26 and 28 August respectively.

With the whole of southern France now liberated, the Franco–US forces pushed northwards. They proceeded quickly up the Rhone valley in pursuit of the retreating Germans, stopped briefly and bloodily at Montélimar. This was the only pause in an advance that covered 650km of France in under six weeks. On the way, Lyon was liberated on 3 September and Besançon on the 7th. Three days later, patrols from the US Seventh Army coming from Provence met patrols from the US Third Army advancing from Normandy. The progress of Operation Dragoon was only checked by the Vosges mountains of Alsace, where all Allied advancement towards Germany ground to a halt in the autumn of 1944.

The official memorial to the landing in Provence was inaugurated in 1964 by General de Gaulle during his presidency. It pays tribute to the soldiers of the French and American armies who participated in the landings and subsequent Allied attacks. The story of the events of August 1944 as they unfolded is told through a range of audiovisual presentations, archives, models and other exhibits. The role played by troops recruited in France’s African colonies is particularly emphasized.

40 Chemin de la Badesse, Aix-en-Provence, ![]() campdesmilles.org

campdesmilles.org

Located southwest of Aix, this imposing building in the grounds of Camp des Milles serves as both a museum and a memorial. It was built in 1939, initially to intern Germans and Austrians living in France. The Germans later used it as a transit camp for Jews. The memorial adopts an educational approach with a view to reinforcing the vigilance and responsibility of citizens to combat racism, anti-Semitism and all forms of fanaticism.

National Necropolis of Boulouris

Saint-Raphaël, ![]() cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/en/saint-raphael-boulouris

cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/en/saint-raphael-boulouris

This national cemetery contains the graves of 464 combatants – of various nationalities and denominations – belonging to the First French Army who were killed during the landings in Provence.

Rhône American Cemetery and Memorial

553 Boulevard John Kennedy, Draguignan, ![]() abmc.gov

abmc.gov

This site near Draguignan was chosen to bury the men who were killed on the route of the US Seventh Army’s drive up the Rhône Valley. The cemetery contains the graves of 858 American soldiers who fell during the course of Operation Dragoon.

The Luynes necropolis, which lies a few kilometres south of Aix-en-Provence near Les Milles, was completed in 1969. Buried here are 11,424 soldiers who fell during both world wars, including 3077 who died in the wake of the landing on the French Riviera in 1944.

British General Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army group was responsible for liberating most of northeastern France in the autumn of 1944.

After the Battle of Normandy, US General Eisenhower directed Montgomery’s 21st Army Group – consisting of the British Second Army and First Canadian Army – to move north into Belgium, with the objective of taking Antwerp and the River Scheldt. On the way, the two armies had to clear northeastern France, including the Channel coast. Dieppe, site of a military debacle for the Allies in 1942, was captured on 1 September 1944 after the German garrison had withdrawn.

A far more important port, Le Havre at the mouth of the Seine, proved a far greater challenge. It was liberated on 12 September after a massive RAF bombing campaign, described as “a storm of iron and fire.” The Allies refused to evacuate the town, killing an estimated two thousand people. Le Havre was near-destroyed.

Further north, Montgomery’s troops dealt with resistance in the Pas de Calais region, the strip of coast nearest to England. In 1940, Hitler had dreamt of launching an invasion across the English Channel to finish off his last enemy, but “Operation Sea Lion” never took place. Instead, Pas de Calais was heavily fortified, both to deter an inbound invasion and as a base from which to bombard London with Hitler’s new long-range weapons, the V1 and V2.

In the early autumn of 1944, British and Canadian troops liberated the Channel ports of Boulogne (22 September) and Calais (1 October). On 15 January 1945, the first civilian train for five years ran from London to Paris via the ferry to Calais. Dunkirk – its name still resonating in British ears for its connotations of defeat and military resurrection – held out until the end of the war.

Atlantic Wall Museum (Batterie Todt 39/45)

Audinghen, Cap Gris Nez (between Calais and Boulogne), ![]() batterietodt.com

batterietodt.com

One of the Third Reich’s seven biggest constructions, this fortified gun battery still looks across the Channel at the enemy coast. Originally it had four 380mm guns concealed in casemates, each capable of firing projectiles to a distance of 42km – easily reaching the coast of England. A crew of eighteen men and four officers was needed to operate each gun.

The battery was bombed by the RAF and then stormed by Nova Scotia Highlanders on 29 September 1944. No.2 gun fired a last wild shot at Dover before the assembly was surrendered at 10.30am. Today, the battery is a war museum on three levels. Unique in Europe, a 280mm railway gun is stationed outside, a monstrous 35m in length.

Rue André Clabaux, Wizernes, ![]() lacoupole-france.com

lacoupole-france.com

In 1943, Adolf Hitler decided to destroy London using new weapons. To this end, he ordered five “special constructions” in the Pas de Calais, but all of them were bombed before they could be put into use. The largest of the lot is La Coupole of Helfaut, which has a concrete dome 72m in diameter and 5m thick over what was to be the largest V2 rocket launch pad ever constructed.

Of all the World War II museums in northern France, La Coupole is one of the best, with a labyrinth of 7km of galleries to explore. As you walk around the site of the intended V2 launch pad, individual, multilingual headphones tell you the story of the occupation of northern France, about the use of prisoners as slave labour, and the technology and ethics of the first liquid-fuelled rocket – advanced by Hitler and later developed for the space race by the Soviets, French and Americans. Among the exhibits are an authentic V1 and V2 (restored by a local company). Four excellent films cover all aspects of La Coupole.

Rue de Sartes, Eperlecques, ![]() leblockhaus.com

leblockhaus.com

Another of the “special constructions” that was built in the Pas de Calais, Eperlecques was planned as a launch site for V2 flying bombs, but never came into operation. Today, visitors are guided around the exhibits – including an authentic V1 launch pad – by a number of talking “sound points”.

Between Landrethun-le-Nord and Leubringhen, ![]() mimoyecques.fr

mimoyecques.fr

From spring 1943 until the late summer of 1944, the Germans used forced labour to build this secret base for deploying their “supergun”, usually referred to as the V3 or the “canon de Londres”. Had it been completed, the guns at Mimoyecques would have been collectively capable of firing 1500 shells a day across the English Channel. On 6 July the fortress was hit by lethal Tallboy bombs dropped by the RAF. It was stormed and taken by the Canadians on 5 September, before it was operational.

Credit: Alamy

Tunnel at Mimoyecques Fortress

Margival, ![]() ravinduloup2.wixsite.com/asw2/w2

ravinduloup2.wixsite.com/asw2/w2

After the abortive Dieppe raid, Hitler ordered the construction of a western command post from which to co-ordinate the defence of France in the event of an invasion. Much of this complex of 475 bunkers is still intact, but can only be visited on a guided tour lead by enthusiasts of the Association de Sauvegarde du W2. Shortly after D-Day Hitler visited Wolfsschlucht II, the first time he had come to France since 1940. When a malfunctioning V1 flying bomb landed not far from Margival, he cut his visit short and hurried back to Germany.

Western, southwestern and central France

The breakthrough at Avranches in late July 1944 meant the Allies could move freely in France.