The Liberation Belgium and Luxembourg

After their success in France, the Anglo-American armies swept eastwards across Belgium and Luxembourg in a concerted push towards Germany.

The First US Army crossed the Belgian border on the morning of 2 September 1944, passing through the hamlet of Cendron before liberating the city of Mons the following morning. The British reached Brussels on 3 September and Antwerp the next day; the Americans liberated Liège on 7 and Luxembourg on 10 September. By the middle of the month, both countries were largely free of German troops.

Belgium had been occupied for four years, ever since May 1940 when the German army invaded and encircled the Allied armies via a daring advance through the Ardennes. The official Belgian response to invasion was divided: Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot and his ministers wanted the king and government to move to France; King Léopold III wished to remain in Belgium. To the disgust of the Allies, the king surrendered to the Germans, prompting his ministers to head for France anyway. When France fell, an attempt at reconciliation by Pierlot was rejected by the king, who now viewed his prime minister as a traitor. Léopold hoped to negotiate with Hitler to achieve some form of autonomy for the country, but failed to do so and his status and influence declined as the occupation continued. Shortly before the liberation in June 1944, he was deported to Germany. Meanwhile, Pierlot and his ministers had formed a government-in-exile in London, but their distant relationship with their homeland made them less effective allies than the Poles or the Czechs. However, many Belgian soldiers and airmen fought as part of the British forces.

Credit: Getty Images

Belgian women ride on the hood of a jeep after their country's liberation, September 1944

Belgium was governed by a Wehrmacht military administration, presided over by SS-Gruppenführer Eggert Reeder. Most of the day-to-day running of the country was managed by existing Belgian authorities, with key positions in central and local government going to members of the right-wing Flemish nationalist group, the Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (VNV). Wallonia, the Francophone half of the country, also had its own fascist party, the Rexists. Both had paramilitary wings – the Flemish Legion and the Walloon Legion – which sent units to fight alongside the Germans against the Soviets.

Resistance to the Nazi occupiers was sporadic and disorganized, particularly in the early years. Activities increased with greater Nazi oppression and the realization, after the Normandy landings, that the Germans were likely to be defeated. The biggest resistance group was the Armée Secrète (AS), which had ties to the Pierlot government but remained loyal to Léopold III. They were responsible for acts of sabotage and, in connection with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in London, were part of the organized escape lines for Allied airmen who had bailed out over Belgium. One great motivator for resistance was the German economic exploitation of the country, not just in terms of goods and raw materials, but in the Reich’s insatiable demand for labour. By 1943 more than 500,000 Belgians had been forced to work in Germany or France, and many people went into hiding to avoid deportation.

Belgium’s Jews numbered between 65,000 and 70,000 in 1940, mostly concentrated in Antwerp and Brussels. Many were stateless refugees who had arrived after World War I. Nazi racial laws were applied almost immediately, but with less efficiency or enthusiasm than in other occupied countries. Many Belgians objected to how Jews were treated, including the country’s leading Catholic, Cardinal van Roey, but Belgium’s administrators were willing collaborators, and there were plenty of anti-Semites happy to join in the Nazi persecution. In April 1941, the VNV and others set fire to two Antwerp synagogues, which the fire brigade was prevented from putting out. Many Jews simply failed to register and others went into hiding, but in July 1942 deportations began in earnest when the Dossin Barracks near Mechelen was converted into a transit camp for Jews. Nearly 26,000 left here on trains to Auschwitz-Birkenau and other camps; fewer than two thousand deportees survived the Holocaust.

Significant sites

Significant sites are marked on the map

Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History, Brussels.

Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History, Brussels.

National Memorial Fort Breendonk, Willebroek.

National Memorial Fort Breendonk, Willebroek.

Even as they were driven out of Belgium in September 1944, German troops continued committing barbaric acts, often random and disproportionate retaliation for small gestures of resistance. It was a foretaste of what was to come during the massive counteroffensive, known as the Battle of the Bulge, that was launched by the Nazis later in the year.

Credit: Getty Images

An American soldier plays during a memorial service at Luxembourg American Cemetery

German occupation of Luxembourg

Luxembourg has an area of 2586 sq km, slightly smaller than the US state of Rhode Island and slightly larger than the English county of Dorset. The eastern side of the country borders Germany, with its boundary along the Our and Moselle rivers.

In 1940 Luxembourg had a population of 296,000 but no standing army, making it easy pickings for the Wehrmacht. The invasion took place on 10 May 1940, prompting the reigning monarch, Grand Duchess Charlotte, to leave the country with her ministers. The departure of the government left the state functions of Luxembourg in disarray. For her first two years Charlotte was in Canada and after 1943 in London, from where she broadcast regular morale-boosting messages to her countrymen.

By August the country was under direct German administration, with the Gauleiter of Mosseland, Gustav Simon, put in charge. His role was to assimilate the country into the Reich, a project strongly resisted by a generally hostile population. In October 1941, Simon organized a referendum which posed questions about national identity. Encouraged by the resistance, over ninety percent of citizens declared themselves Luxembourgish, prompting the Nazi regime to become markedly more harsh. All languages apart from German were now banned and citizens were forcibly conscripted into the German armed forces. The following summer a general strike against compulsory national service was only halted after its ringleaders were executed and hundreds of protesters sent to concentration camps. Of those Luxembourgers conscripted, possibly as many as 25,000 died – most shot as deserters.

Northern Luxembourg was devastated during the Battle of the Bulge, as Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army bombarded US positions in its December push into Belgium, and then again when the Americans forced the Germans back in January and February 1945. Around 3500 homes were damaged or destroyed, some 45,000 people became refugees, and about one-third of the country’s farmland was unable to be cultivated.

On 2 September 1944, the British Guards Armoured Division (commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Allan Adair) was stationed in northern France when, late in the evening, XXX Corps commander Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks gave the order to march on Brussels.

Allan Adair and his men set off early on 3 September and by evening had entered Brussels by the Avenue de Tervuren, having covered more than 120km in one day. They were greeted by crowds of jubilant Belgians lining the Boulevard de Waterloo.

That same morning, most of the German troops had taken to their heels. In Brussels – as in other cities – their withdrawal was accompanied by much destruction. Before leaving, German soldiers set fire to the Palace of Justice in order to burn the documents still stored there. Despite efforts to extinguish the fire, the copper dome of the building collapsed, although not before thousands of bottles of wine had been removed from the cellars and distributed among the wildly celebrating crowds. Sporadic fighting was still occurring in some parts of the city, including violent clashes between resistance fighters and German soldiers in the Parc du Cinquantenaire.

The next day saw the arrival of the 1st Infantry Brigade of the Free Belgian Forces, better known as the Piron Brigade after its commander Colonel Jean-Baptiste Piron, who had transformed it into a first-rate combat unit after being put in charge in 1942. As part of the British 6th Airborne Division, the brigade was active in Normandy from 8 August 1944, liberating towns and villages eastward along the coast. Brussels’ citizens were pleasantly surprised to discover compatriots among the liberating forces, though some mistook them for French Canadians.

On 8 September, Hubert Pierlot, prime minister of the Belgian government-in-exile in London, returned to Brussels to lead a government of national unity. He was met with almost total indifference by the population. One of the first actions of the new government was to appoint Prince Karel, Count of Flanders, as regent in the absence of his brother, King Léopold III. But faced with the problems of food shortages, controversy over his acrimonious relations with the exiled king, and his failure to pursue collaborators sufficiently vigorously, Pierlot and his government grew increasingly unpopular. Forced to rely on the British military commander, Major General Erskine, to maintain order in the face of communist-led riots and resistance fighters’ refusal to give up their arms, Pierlot’s government eventually fell in February 1945.

›› Hitler’s funeral in the Marolles

The inhabitants of the Marolles district in central Brussels celebrated their city’s liberation with a mock funeral for the Führer. On Sunday 10 September they carried a Hitler lookalike in a coffin through the streets on the back of a horse-drawn cart. Printed cards announcing the “sad news” referred to Hitler as the “Grand Chevalier de L’Espace Vital” ("Grand Knight of Living Space"), a reference to his demands for European living space for German settlers. The mourners listed included “Monsieur General Goering, his confidant”, while the funeral music was to be conducted by the “well-loved Benito Mussolini”. A rag-bag of uniformed followers accompanied the cortege, while the crowd threw an assortment of offerings – flowers, tomatoes, eggs – and occasionally spat at the prone figure. The departure point on the Rue de la Prévoyance from where the procession set off is now marked with a commemorative plaque.

Credit: Alamy

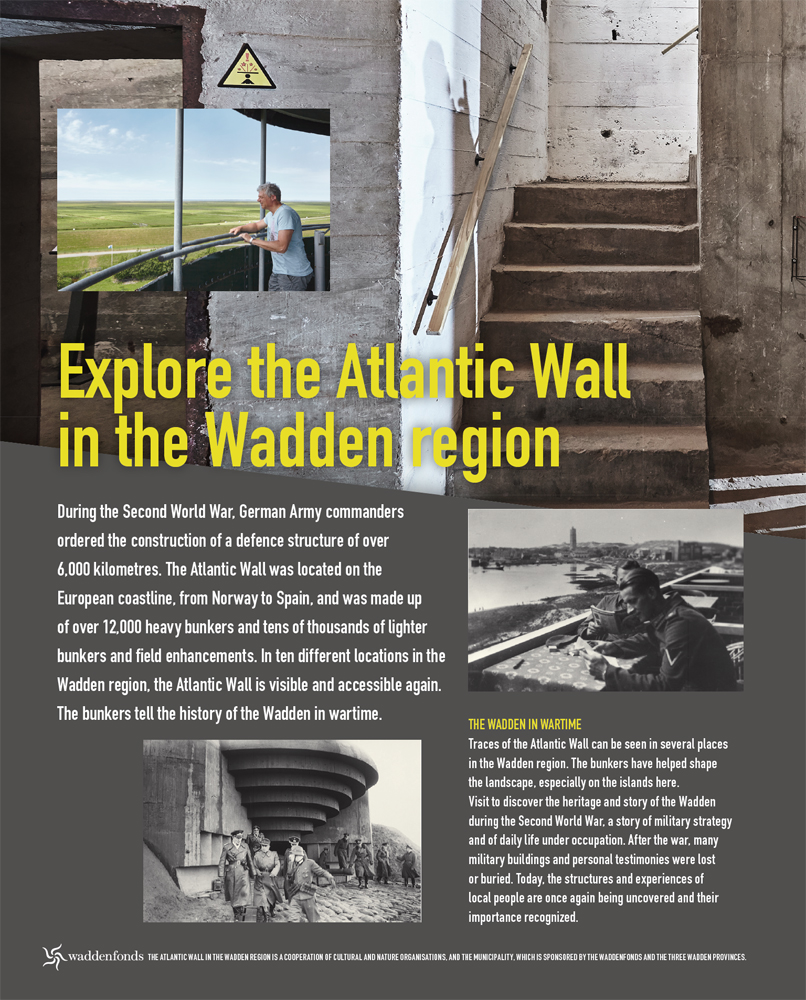

Radios at the Atlantikwall Museum

Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and of Military History

Jubelpark 3, Brussels, ![]() klm-mra.be

klm-mra.be

Located in Brussels’ Parc du Cinquantenaire, or Jubelpark, this museum traces the history of the Belgian army from the late 18th century to the present day by means of a vast hoard of weapons, armaments and uniforms. The magnificent Bordiau Gallery (named after the architect of the park and its buildings) is dedicated to the major conflicts of the 20th century. New displays for the World War II material are currently being constructed, and will cover four main topics: the German occupation of Belgium (1940–44), the Liberation (1944–45), the ideology and race policy of the Nazis (1933–45) and the war in the Pacific (1937–45).

Nieuwpoortsesteenweg 636, Ostend, ![]() raversyde.be/en/atlantikwall-0

raversyde.be/en/atlantikwall-0

The Atlantic Wall was a line of German fortifications and gun batteries built to protect the northern European coastline from Allied invasion. Much of it still exists, including a well-preserved section along the Belgian coastline, 8km from Ostend. Here among the dunes can be found sixty bunkers (some from World War I), connected by lines of trenches and tunnels. The area was part of an estate owned by the Regent, Prince Karel, who was active in the preservation of the defences. The site is not suitable for those with disabilities or wheelchair users.

The taking of such a large and well-equipped port as Antwerp was a hugely significant capture for the Allies, as those ports already liberated in northern Europe were either too small or too badly damaged to solve the Allies’ supply needs.

The British 11th Armoured Division, part of the Second Army, rolled into Antwerp at midday on Monday 4 September. By the evening, German forces in the centre of town were routed, the docks saved from destruction by the Belgian resistance, and six thousand POWs locked up in the cages of Antwerp Zoo. Fighting continued, however, and attempts by the division to create a bridgehead across the Albert Canal, a recently completed waterway linking the rivers Scheldt and Meuse (or Maas), were fiercely resisted and resulted in failure.

Having supply lines this far east would now make it that much easier for the Allies to strike into Germany. But for this to happen effectively, the vast estuary at the mouth of the River Scheldt (part of the Netherlands) would need to be under Allied control. Unfortunately, Montgomery delayed clearing the estuary, instead giving priority to Operation Market Garden (see box). This gave the Germans time to reinforce the estuary island of Walcheren and the Beveland Isthmus on the Scheldt’s north shore, thus preventing Allied shipping from reaching Antwerp. Many historians regard Montgomery’s oversight as one of the Allies’ gravest strategic errors of the entire war.

When Montgomery finally realized just how important clearing the Scheldt was (having had the point emphasized by Eisenhower), he decided to assign the formidable task to the First Canadian Army under the temporary command of Lieutenant General Guy Simonds. The ensuing Battle of the Scheldt was won on 8 November, but it was another three weeks before the estuary was finally made safe after a major mine-sweeping operation. The first Allied shipping arrived in Antwerp on 28 November 1944 and by mid-December 23,000 tons of goods per day were being unloaded.

›› Operation Market Garden – Montgomery’s daring plan

Having liberated Belgium, Allied commanders were now at odds about the best way to progress. Patton favoured an advance into Germany from the south; Montgomery wanted a concentrated attack through the Netherlands in the north. As their boss, Eisenhower was adamant that a broad front should be preserved (rather than concentrating the bulk of his troops at a single point), but he was intrigued by Montgomery’s plan and in the end gave it the green light.

Montgomery’s idea was for a two-part operation (codenamed Market Garden) that would entail three airborne divisions landing in the Netherlands and capturing bridges and territory at Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem, thus creating a corridor for the British XXX Corps to advance along. The furthest bridge at Arnhem was over the Lower Rhine which, once secured, would open a gateway into the Ruhr – Germany’s industrial heartland – that would bypass the massive German Westwall defences.

The starting point for the ground troops in Belgium was at Bridge Number 9 across the Bocholt-Herentals Canal at Neerpelt, which was captured by a unit of the Irish Guards in a surprise attack on 10 September 1944. Thereafter it was named Joe’s Bridge in honour of the unit’s commander, J.O.E. Vandeleur. The XXX Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Horrocks, set off from Joe’s Bridge on the afternoon of 17 September.

While the Germans were able to thwart the use of Antwerp as a working port for almost two months after its liberation, they also instigated a ruthless bombing campaign. Even before the port was up and running, V2 rockets and V1 flying bombs were pointed at the city. A V2 hit the busy central square of Teniersplaats on 27 November 1944 killing 159 people; another landed on the Rex Cinema in the Avenue de Keyser on 15 December. A total of 567 people were killed, over half of them Allied servicemen, and many more were injured. Although the Allied anti-aircraft teams grew adept at hitting the V1s, the silent V2 – which had a maximum speed of 5760km per hour – could not be defended against and caused massive amounts of damage. As much as two-thirds of Antwerp’s houses were destroyed in raids that lasted from October 1944 until March 1945.

National Memorial Fort Breendonk

Brandstraat 57, Willebroek, ![]() breendonk.be

breendonk.be

Built in the early 20th century as one of a line of forts for the defence of Antwerp, Fort Breendonk is located 20km south of Antwerp. From September 1940 until Belgium’s liberation it functioned as a Nazi concentration camp, and about 3500 prisoners were interned here, staying an average of three months before being deported to camps in Germany, Austria or Poland. Jews made up half the number in the first year of the occupation, before Dossin Barracks (see below) was established as a Jewish transit camp in 1942. An austere and forbidding place, surrounded by a huge moat, the fort is one of the best-preserved Nazi camps and is now a memorial and education centre dedicated to all those who suffered here. An audio guide is available for non-French or Flemish speakers, which focuses on the harrowing personal testimonies of individual prisoners. The site is not suitable for young children.

Goswin de Stassartstraat 153, Mechelen, ![]() kazernedossin.eu

kazernedossin.eu

Ten kilometres southeast from Fort Breendonk is Kazerne Dossin (Dossin Barracks), a former Austrian military base used as a Jewish transit camp. From here, 25,484 Jews and 352 Roma and Sinti were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and other camps. Less than five percent of them survived.

Previously housed in part of the barracks, in 2011 a new building was opened nearby as a “Memorial, Museum and Documentation Center on Holocaust and Human Rights”. As the name suggests, the focus is not just on the Nazi victimization of Belgium’s minorities – the centre places those experiences within the wider and continuing story of persecution and human rights abuses across the world. It’s a less raw experience than Fort Breendonk, as the new building relies on interpretation and symbolism to connect you to the horrors of past and present, but the displays are thoughtfully and clearly presented.

The Ardennes is a rugged, forested wilderness that stretches across southern Belgium and into northern Luxembourg, but also includes parts of Germany and France. It played a crucial role during World War II on two separate occasions.

In 1940 the German army launched a surprise attack through the Ardennes which led to their occupation of western Europe. In the winter of 1944–45, the Germans tried to repeat their earlier success with a similar attack. By this point of the war, however, the balance of power had shifted in favour of the Allies, and the German offensive – known as the Ardennes Offensive (and by the Allies as the Battle of the Bulge) – proved not just unsuccessful but a disastrous setback from which the Wehrmacht never recovered.

Codenamed “Wacht am Rhein” (Watch on the Rhine), the Ardennes Offensive was almost entirely the brainchild of Hitler himself. A highly ambitious operation, its aim was to sweep through the Ardennes, seize the bridges over the Meuse River and recapture the key supply port of Antwerp. This would halt the Allied advance into Germany and allow the Nazis to encircle and destroy four Allied armies. Hitler hoped it might even succeed in driving the Allies back to the English Channel and force them to negotiate a peace treaty in the Axis’ favour.

Hitler’s senior generals were highly dubious about the scale of the plan. General Guderian, for one, felt that stalling the Soviet advance on the Eastern Front was of far greater importance and that a big push in the Ardennes would squander vital men and resources. Model and von Rundstedt, meanwhile, believed that aiming for Antwerp was simply too ambitious.

The Allied lines stretched from Antwerp in the north to southern France, but the Ardennes was undermanned, largely because both Bradley and Montgomery had told Eisenhower that a German attack was highly unlikely, especially in such difficult terrain. When the offensive was launched on 16 December 1944, it therefore had the advantage of surprise. The mist and fog that had descended also benefited the German troops, rendering the vastly superior Allied air power initially ineffective.

The main German force comprised three armies: General Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army in the north; General von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army in the centre; and a back-up force of General Brandenberger’s Seventh Army in the south, tasked with protecting the flank. They would find themselves up against mostly American troops: the US First Army and US Ninth Army (both part of Bradley’s 12th Army Group). To maximize American confusion, the Germans formed a brigade of English-speaking soldiers dressed in US uniforms that was sent ahead to infiltrate the US lines – a move which contravened the rules of war and succeeded in generating rumour and paranoia among the Allied troops.

Leading the German attack was the Sixth Panzer Army, commanded by SS- Oberstgruppenführer Sepp Dietrich. It was spearheaded by the 1st SS Panzer Regiment, a combat group (Kampfgruppe) led by Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) Joachim Peiper, a young SS officer known for his ruthlessness. His task was to reach the River Meuse and secure the bridges at Huy. Under his command were nearly six thousand troops and seventy tanks, including the powerful and heavily armoured Tiger II. Roads that were little more than tracks meant that progress was slower than Peiper expected, and US troops – though unprepared for the assault and struggling to find adequate defensive positions – managed to slow his progress. Many US troops were killed or captured in the fighting, including 86 massacred near Malmédy after surrendering.

Hitler had envisaged a swift Blitzkrieg-style offensive (as in the previous Ardennes assault), but this time the weather, the terrain and shortage of fuel were working against him. More importantly, once the Americans realized what was happening, they put up formidable resistance. On the northern shoulder of the German advance, the Sixth Panzer Army was effectively halted by the 99th and 2nd Infantry Divisions of V Corps (part of the US First Army). The bitter and often confused fighting lasted around ten days. Initially centred on the twin villages of Krinkelt and Rocherath, the Americans withdrew to nearby Elsenborn Ridge on 19 December. From here, a war of attrition ensued with heavy casualties on both sides, but the Americans were well enough dug in to repel almost everything that the Sixth Panzer Army could throw at them.

The Germans had greater success in the centre, where US troops were outnumbered and gradually overwhelmed by the Fifth Panzer Army. Manteuffel’s immediate aim was to capture the towns of St Vith and Bastogne, both important road and rail junctions which would facilitate German progress towards Antwerp. Blocking his route was the recently arrived US 106th Division which was defending a wide front in the rugged and hilly Schnee Eifel on the Belgium-German border. The American soldiers were inexperienced and poorly trained, however, hindered by strategic errors in the command chain as well as bad weather, which thwarted Allied air support. Due to a miscommunication, Major General Jones, the divisions’ commander, held fast rather than pulling his troops back, with the result that two regiments were encircled and about seven thousand men were forced to surrender on 19 December.

Two days later, American troops withdrew from St Vith and the town fell to the Germans. For Hitler, this seemed like an enormous success, but he had repeatedly ignored Manteuffel’s advice to return to the Siegfrield Line in order to continue the attack. American resistance had put the Ardennes Offensive well behind schedule, allowing the Allies to regroup and plan a counterattack.

Eisenhower was already sending reinforcements along the Ardennes front, with a total of around 240,000 men deployed during the last ten days of December. Because the German advance had split the troops of Bradley’s 12th Army Group to the north and south of the “bulge”, Eisenhower temporarily assigned the American First and Ninth Army from the 12th to Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in the north (much to Bradley’s annoyance). Montgomery immediately sent four British divisions towards the Meuse to protect the river crossings at Givet, Dinant and Namur.

On 19 December 1944, Brigadier General McAuliffe and the 101st Airborne Division arrived in Bastogne, a few hours ahead of three divisions of the Fifth Panzer Army – 18,000 Americans pitted against 45,000 Germans. By 21 December German troops had encircled the town; McAuliffe, his troops and around three thousand civilians were completely enclosed and ammunition and medical equipment were running low. The following day General von Lüttwitz, commander of the XLVII Panzer Corps, issued an ultimatum to the besieged Americans: “There is only one possibility to save the encircled U.S.A. troops from total annihilation: that is the honourable surrender of the encircled town.” McAuliffe’s official typed reply read as follows: “To the German Commander. NUTS! The American Commander”. More days of fierce fighting followed, but McAuliffe and his men held fast, despite suffering heavy casualties. A large consignment of supplies was air dropped to them on 23 December and the weather had improved sufficiently for squadrons of Thunderbolts to attack the enemy’s armoured troops.

On 17 December 1944, 140 US soldiers left Malmédy heading south when they ran in to the Peiper Kampfgruppe at the crossroads of Baugnez. After an exchange of fire, the Americans surrendered and around 113 of them, with arms raised, were herded into a snow-covered field. Peiper was apparently not present when, at 2.15pm, the Germans opened fire on the prisoners and then wandered the field shooting them individually at close range. Amazingly, around sixty survived, having played dead until they could make their escape.

The reasons for the shooting remain unclear. Was it a premeditated or a spontaneous act? Had the prisoners attempted to escape, ostensibly justifying the shooting? Was Peiper reluctant to have his progress slowed by having to deal with POWs? One possible clue is that the massacre was not an isolated incident but part of a series of war crimes committed by the same unit throughout the Ardennes Offensive. Other incidents were reported at Bande, Noville, Stavelot, Bourcy, Houffalize, Cheneux, La Gleize, Stoumont, in the region between Stavelot and Trois-Ponts, and in Lutrebois and Petit Their.

In 1946, those accused of the massacre were brought before the Military Tribunal at Dachau. The “Malmédy massacre trial” covered all the war crimes charged to Kampfgruppe Peiper during the Battle of the Bulge, with over seventy people put on trial. Forty-three of the accused were sentenced to death but for various legal reasons nobody was executed; instead, 22 were given life sentences. Peiper, in prison the longest, was released in 1956. After a career in the motor industry, he ended up living in France where one day he was recognized by a former communist resistance fighter and publicly denounced. On the night before Bastille Day 1976, Peiper’s house was firebombed. His burnt remains were discovered the next day.

Meanwhile, three divisions of Patton’s Third Army were heading up from the south, having managed the remarkable feat of turning 90 degrees from their eastward course and pushing north along a 40km front. Unfortunately, Patton’s radio security was poor, allowing the Germans to track the divisions’ movements and slow them down. On Christmas Eve 1944, German bombers began the first of two raids on Bastogne, but by Boxing Day the first of Patton’s troops, the 37th Tank Battalion, finally entered the town.

To the west, the Germans had reached as close to the River Meuse as they would get, capturing the village of Celles, just 9km away from Dinant, on Christmas Eve. Forced back by a combination of the US 2nd Armored Division and VII Corps, the 2nd Panzer Division was dangerously low on fuel, prompting von Manteuffel to order his troops to abandon their vehicles and retreat on foot. Further to the north, Peiper’s Panzer Regiment was in the same predicament and had to turn back towards the German lines with 135 armoured vehicles left behind. Of Peiper’s original elite force of 5800 men, only about eight hundred remained.

The Germans attempted to regain the front foot by launching Operation Bodenplatte on 1 January 1945 – an attack by the Luftwaffe on sixteen Allied air bases in Belgium, France and the Netherlands that was intended to wrest control of the skies from the RAF and USAAF. Though plenty of Allied planes were destroyed, they were replaced in little more than a week, whereas the German losses, both planes and personnel, badly damaged the Luftwaffe – this would turn out to be its last major operation.

It was now the Allies’ turn to take the offensive and finally eradicate the salient (or “bulge”) in their lines. Troops from Patton’s Third Army advanced northwards from the south, while the US First Army headed southwards from the north, the two forces converging on 16 January at Houffalize, or rather what was left of it. Allied bombers had completely destroyed the town, which had been a strategic crossroads on the highway from Bastogne to Liège. St Vith was recaptured on 23 January after which the battle ground to a halt.

Out of a US fighting force of 600,000, around 19,000 men had lost their lives and approximately the same number were taken prisoner. German casualties are disputed, but may have been as high as 120,000 men killed or wounded and about seven hundred tanks destroyed – very significant losses which did lasting damage to the Wehrmacht.

Credit: Edwin van Wanrooij

101st Airborne Museum

Rue de la-roche 40, Bastogne, ![]() klm-mra.be/D7t

klm-mra.be/D7t

Opened as a museum in 2010, the barracks (just outside Bastogne) were the headquarters of the US 101st Airborne Division during the Ardennes Offensive, and the place from where General McAuliffe sent his famous “NUTS” riposte to General von Lüttwitz. A two-hour tour takes in the operational rooms, in which uniformed mannequins and original wartime equipment create something of the atmosphere of this key command centre. There is also a great collection of military vehicles, including Tiger and Sherman tanks, many of them in full working order. In the centre of Bastogne, the main square is named after McAuliffe and contains a memorial bust of the general.

The Mardasson Memorial was inaugurated in 1950 and commemorates the US servicemen who risked or lost their lives on Belgian soil in World War II. A temple-like structure, designed by Belgian architect Georges Dedoyard, it takes the form of a huge five-point star supported by tall columns, with the story of the battle engraved in gold on the walls of the open gallery. A walkway on the roof of the memorial provides visitors with a panoramic view of the defensive positions held during the siege of the town. The crypt contains a Catholic, Protestant and Jewish altar, each one decorated with a mosaic by the French artist Fernand Léger.

Colline du Mardasson 5, Bastogne, ![]() bastognewarmuseum.be

bastognewarmuseum.be

Opposite the Mardasson Memorial is the new Bastogne War Museum, which covers the whole Belgium experience of World War II, rather than just the Battle of the Bulge. The concept of the displays is very high-tech, with a series of “experiences”, including one scene set in the Ardennes forest and another set in a café – with the sounds of war all around. The audioguide, provided as part of the entrance fee, continues the multi-sensory, narrative approach by providing the perspectives of a fictional group of people, including a Belgian child and a German soldier. There are plenty of objects on display, but this museum is more about immersive excitement than quiet contemplation.

Av de la gare 11, Bastogne, ![]() 101airbornemuseumbastogne.com

101airbornemuseumbastogne.com

The 101st Airborne Museum is located in the former officers' mess of the Belgian army in Bastogne, in a historic building that was later used as a hospital by the Red Cross. The museum’s focus is the Battle of the Bulge, and the exhibition centres on a number of lifelike tableaux. There’s also a recreated bomb shelter, complete with sound and visual effects to help visitors imagine what it was like to be caught up in a raid.

Le Bois Jacques (Jack’s Wood), close to the village of Foy, is where the men of “E” (known as Easy) Company of the 101st Airborne Division dug themselves in on 19 December as part of the defence of Bastogne. Despite being outnumbered, enduring constant bombardment, and with night-time temperatures as low as –28ºC, they managed to hold the enemy at bay. Foy changed hands several times, but was captured by the Americans on 13 January 1945. The “foxholes” and cavities that the soldiers dug in the wood as protection from hostile fire are still visible, and a monument to their courage was unveiled here in 2004.

In the hamlet of Recogne, close to Foy, is a German war cemetery containing the graves of more than 6800 German soldiers between the ages of 17 and 52. About half were killed during the Ardennes Offensive; the rest were brought here from other battle sites in Belgium and Luxembourg. A simple red-bricked chapel marks the entrance to the cemetery. Over 2500 American troops were also buried at Recogne but were subsequently transferred to the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial at Plombières.

With several unique pieces relating to the Malmédy massacre, this modern museum evokes the Battle of the Bulge through historic photographs and film footage, military material and vehicles, and fifteen tableaux depicting the life of an ordinary soldier.

December 44 Historical Museum La Gleize

Rue de l’église, La Gleize, ![]() december44.com

december44.com

Sixty kilometres north of Bastogne is the village of La Gleize, where the SS combat group led by Joachim Peiper was halted and forced to abandon its vehicles before retreating through the US lines. One of the group’s tanks, a King Tiger, now stands outside a small museum founded in 1989 by local resident, Philippe Gillain, who had been scouring the neighbourhood for wartime remains since he was a teenager. Dedicated to the Ardennes Offensive, the museum has a wealth of military hardware and uniforms on show, many displayed with mannequins set against dioramas.

Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial

Rue du Mémorial Américain 159, Plombières, ![]() abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials

abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials

At the edge of the Belgian Ardennes, about 30km east of Liège and close to the German border, this 25-hectare US war cemetery contains nearly eight thousand American servicemen who died at the Battle of the Bulge and in Germany. The graves are laid out in gently curving lines on either side of a central pathway.

The memorial itself is a rectangle of pale stone bearing a vast relief sculpture of an eagle with wings outstretched on its front and the insignia of all the divisions that served in Belgium on its back. At the eastern end of the cemetery is a colonnade that, with the chapel and map room, overlooks the burial area. The piers of the colonnade bear the names of 463 soldiers missing in action.

On 9 September 1944, forces from the US 5th Armored Division crossed the border from France and entered the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg near Pétange.

The next day, on 10 September, the division reached Luxembourg City and the rest of the country was liberated shortly afterwards. It had endured just over four years of occupation, during which time more than five thousand Luxembourgers were killed, around two thousand of whom were Jewish.

Rue Grande-Duchesse Charlotte/Bastnicherstrooss, Wiltz, ![]() nlm.lu

nlm.lu

During the Battle of the Bulge, Schumann’s Eck was a strategically important crossroads. Many American and German soldiers lost their lives here; a monument was erected in their honour on the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Luxembourg. Today’s memorial includes several plaques explaining the actions of US units during the battle.

National Museum of Military History

Bamertal 10, Diekirch, ![]() mnhm.net

mnhm.net

One of the better World War II museums in the region, providing a good historical survey of the Battle of the Bulge with an emphasis on the troops that liberated Diekirch. There’s plenty of miltary equipment, but the main draw are the photographs showing both sets of troops. A display entitled “Veiner Miliz” details the activities of the resistance movement based in Vianden, and there’s a room devoted to Tambow, a Soviet camp where many Luxembourgers who had worked as Nazi forced labour at the Eastern Front were incarcerated.

50 Val du Scheid, Hamm, ![]() abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials

abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials

Located at Hamm, about 6km east of Luxembourg City and the same distance south from the airport, the US cemetery contains the graves of some five thousand American servicemen, including General Patton, who died on 21 December 1945 following a car accident 12 days earlier. Most of those buried here lost their lives in the Battle of the Bulge or in the advance to the River Rhine. It follows the usual pattern of America’s European cemeteries, with the pristine white gravestones laid out in curved lines on manicured lawns surrounded by woodland.

The German burial ground at Sandweiler is a 20-minute walk from the US cemetery. It too is set in woodland, but it’s smaller and less grandiose, with the crosses that mark the graves made from a sombre grey granite. Nearly 11,000 German servicemen are buried here, about half of them interred by the Americans. It’s a melancholy and moving place, with most gravestones carrying the names of two, or sometimes three, combatants.

The Liberation of Europe in 1943–45 was the bloodiest phase of the bloodiest conflict on earth.

It is impossible to give exact figures for how many people were injured and killed during World War II. Some countries kept accurate records of those killed in battle, but failed to record the men and women who died in related circumstances. People disappeared in large numbers, including peasants and civilians whose identities were not documented in the first place; those who never officially existed could not be named in death.

Credit: Getty Images

A Belgian AMC-35 tank engulfed in flames

There have been many attempts to arrive at reliable estimates to express the scale of the casualties. It is likely that fifty million people were killed directly by World War II worldwide. This number can be increased to 70–85 million if “war-related deaths” (a vague term) are added, which would mean that three percent of the global prewar population died in the war. The Soviet Union alone lost between 24 and 26 million soldiers and civilians to the war; Germany lost 6–7 million. An incalculably higher number of men, women and children were left scarred by World War II – physically, mentally and emotionally.

An estimated twelve million people were murdered, not only in concentration camps but in atrocities elsewhere, including almost six million Jews (around fifty percent of Europe’s prewar population). Up to one million people died as a result of bombing.

These figures are astronomical. Statistics like these, while shocking, can frequently feel removed and clinical – a treatment of suffering as a general condition rather than something that affected individuals in highly personal ways. To truly understand the scale of the catastrophe that was World War II, it is necessary to relate these horrifying figures to particular human stories.

Death in wartime is of a chaotic and unpredictable nature, and the soldiers and civilians of World War II could only do so much to improve their odds for survival.

For many front-line infantrymen and bomber crews, the question wasn’t whether or not they would be hit, but where and how. The most prized quality in combat was not patriotism or bravery, but stoicism: to willingly continue in conditions that could not be improved. Many personal accounts of the war discuss the senseless way in which one man would die an unspeakable death while his comrade next to him survived unscathed.

In World War II, protective apparel was rudimentary and inadequate. Soldiers had helmets, but rarely any form of body armour; lightweight bullet-proof materials were not yet invented. Soldiers could keep their heads down and avoid risks, but that was no protection from stepping on a landmine, being strafed by enemy aircraft or being overwhelmed or ambushed by the enemy. Planes were often thin skinned and easily penetrated by flak and shrapnel. Tanks – while armoured against light assault by foot soldiers – could be knocked out by anti-tank guns or specialized hand-held weapons. Additionally, if a tank caught fire, it quickly became a death trap.

Credit: Getty Images

Nurses preparing for an influx of wounded soldiers

Medical treatment for wounded soldiers varied considerably. Some armies had better medical support than others, while the response of medics was also impacted by the terrain of the battlefield. A soldier evacuated from the field by stretcher was taken first to an emergency first-aid post: an improvised facility in a tent or requisitioned house that had to be ready to move in the event of an advance or retreat. Patients who couldn’t be patched up and returned to the front were sorted – passing through a series of more permanent medical clearing stations until the most serious cases were sent to hospitals back home.

Ironically, the war also stimulated medical research into saving and improving lives. During World War II, a number of important breakthroughs were made that helped reduce casualties. In 1943, penicillin became available as a way of controlling the infection of wounds. Anaesthetics also improved, as did techniques of blood transfusion: plasma was introduced as a substitute for whole blood since it was easier to transport and store.

Battlefield injuries, however, were just one cause of death on the front line. Not all military casualties were caused by weapons. Avoidable accidents were common, and disease was rife in the unhygienic and crowded conditions of makeshift medical facilities. The hospitals were filled with men suffering from malaria in Italy, dysentery triggered by a poor diet and contaminated water, trench foot brought on by the northern European winter and frostbite induced by freezing temperatures. Venereal diseases caught by soldiers on leave also posed a serious challenge.

All armies in World War II and the Liberation did their best to patch up the bodies of wounded soldiers. It was in their interest to keep as many trained men on the battlefield as possible, but they were at a loss when it came to treating the men’s injured minds. During World War I, “shell shock” had been observed but often disbelieved. Sufferers were commonly seen as soldiers who were reluctant to return to the front, and the military hierarchy was opposed to giving what they saw as cowardice and malingering a medical name. By World War II, shell shock was beginning to be accepted, though the term was not yet widely used. General Patton almost ended his military career by slapping two soldiers in Sicily because they had no physical injuries but had still been assigned hospital beds.

Credit: Getty Images

Exhausted German soldiers resting by the roadside on the Eastern Front, 1941

Most commanders realized that prolonged exposure to life-or-death decisions could unhinge a person’s mind. While there was no recognized medical term for war-provoked mental illness, neither was there a definitive set of symptoms. For convenience, the condition became known as “battle fatigue”. For the army, the most pressing issue surrounding mental illness was its effect on others. A soldier with battle fatigue was unreliable and a threat to morale. The treatment for anyone in the front line who was unable to do his job due to uncontrollable shaking, relentless moral questioning or acute emotional distress was a period of sedated rest. Once he’d “recovered”, the soldier would be returned to the front line – until he was killed or incapacitated with the same condition.

One of the unspoken causes of injury in World War II was self-harm. A soldier injuring himself in order to be removed from the battlefield was in serious breach of army regulations, but it could be hard to prove. In the Battle of the Bulge, the brutality of combat coupled with the intense cold drove some soldiers to the belief that being wounded out of service was preferable to remaining on the front. A soldier would go into the woods – ostensibly to urinate – and stagger back with a bullet to the hand, arm or leg, claiming there had been a surprise ambush from which he had been lucky to escape alive.

While injuries were complex, death was more straightforward. Wherever an army went on active service, soldiers died in high numbers – whether on the battlefield, in lonely plane crashes or on hospital operating tables. Their corpses had to be dealt with.

Ceasefires were occasionally arranged in the midst of battle – such as at Arnhem – to collect the wounded and the dead, but these were exceptional truces that didn’t last long. Mostly, a battle had to reach a final outcome before its dead could be buried. On some occasions it could take months before it was safe to gather the casualties, as at Monte Cassino in Italy. When the time came, the dead were collected, identified (where possible) and buried nearby, sometimes temporarily – until they could be moved to permanent cemeteries.

In some places, as at Anzio, soldiers could see the cemeteries being laid out even as they went into battle. Most of those who died in World War II were buried near where they fell – although there were exceptions. American families were often given the choice of having the bodies of their young men repatriated.

It has become an accepted practice for official agencies to maintain the cemeteries of the men who perished in World War I and World War II. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (cwgc.org) performs this function for all cemeteries containing British and Commonwealth personnel. US cemeteries are maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission (abmc.gov), while the German war dead are cared for by the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (volksbund.de).

In parts of Europe, being a civilian during the Liberation was even more hazardous than being a soldier. Civilians were killed in their thousands, both deliberately and as an unfortunate side effect of the military campaigns. Whereas each battle death was recorded and mostly included under the banner of sacrifice and duty, civilians often died inconspicuously with no glory or honour. Entire families were wiped out with no one to mourn them.

Civilians also suffered in a great many ignominious and sordid ways: they were injured, robbed, raped and killed by marauding soldiers on both sides. The hospitals that had survived in war-ravaged nations were overwhelmed by demand. Ordinary, ununiformed victims of war seldom received the same medical or psychiatric treatment as service personnel. Most were forced to cope on their own.

Credit: Getty Images

A girl cries over her wounded sister during the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939

Credit: Getty Images