Poland was liberated, not by the Americans or the British, but by the Soviet Union. For the Poles this was a bitter irony.

Having had to endure the onslaught of the Nazi invasion on 1 September 1939, Poland underwent a second invasion at the hands of the Red Army just sixteen days later. These two events – and the devastating occupation that followed – were to set the scene for Poland’s liberation five years later.

Hitler’s pretext for invading Poland was Germany’s claim to the port of Danzig (modern Gdańsk). In the aftermath of World War I, when Poland re-emerged as an independent nation, the country’s redrawn borders provided access to the Baltic via a “corridor” that separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Danzig stood at the top of this corridor, neither Polish nor German, but a free city under the protection of the League of Nations. Many of its citizens, most of whom were German, resented this arrangement.

Credit: Getty Images

Officials discuss the details of the German–Soviet demarcation line following the invasion of Poland in 1939

Hitler used the corridor dispute to try and force the Polish state to hand over Danzig to Germany, but the Poles refused any territorial concessions. For Hitler this was reason enough to invade. The German assault came from several points simultaneously and employed a new tactic, Blitzkrieg (lightning war), in which attacks were fast, intense and co-ordinated. The Polish Army was outnumbered and its forces spread out, and despite valiant counteroffensives, was only staving off the inevitable. Poland’s military command ordered a retreat to the southwest of the country, at which point the Red Army invaded the country from the East, claiming to be protecting Poland’s Ukrainian and Belorusian minorities. After nearly a month of incessant aerial and artillery bombardment, resulting in around 40,000 civilian deaths, Warsaw, Poland’s capital, finally surrendered to Nazi invasion on 27 September 1939.

Following the two invasions, Poland was divided into three main areas under the terms of the Nazi-Soviet Pact: the west of the country was assimilated into the German Reich, with the ultimate aim of full “Germanization”: the removal of all Slavs, Jews and other “undesirables” and their replacement with German colonists.

The east of the country, known as Kresy to the Poles, was handed over to the Soviets (though Hitler was to renege on his agreement, invading the Soviet Union in June 1941). This included parts of Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, many of whose inhabitants were nationalists who resented rule by Poland, the Soviet Union, or anyone else.

The central territory – the rump of Poland – became a German protectorate, renamed the General Government, with Kraków as its capital. A “dumping ground” for Poles removed from the west of the country, it was to be economically exploited for the benefit of the Reich. It was also where the first death camps were built in the spring of 1942.

Potential opposition was targeted by both invading powers. It is estimated that the Nazis killed a third of all Catholic priests, the same proportion of doctors and around fifty percent of Poland’s lawyers. Similarly, the Soviets imprisoned or executed anyone they thought of as ideological enemies, most infamously thousands of Polish army and police officers who were shot and buried in Katyń forest and other sites.

Many of those killed by the Nazis died in concentration camps, labour camps, or in extermination camps, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau. In addition to enslaving the Poles, the Nazis aimed to annihilate Poland’s entire Jewish population, murdering them in gas chambers and mass shootings, or working them to death. Those who hid Jews were also executed, as were those who failed to report someone doing so. Little wonder that some turned a blind eye to the fate of former neighbours or, worse, colluded in their persecution.

Several Polish politicians and members of the armed forces managed to escape and establish a government-in-exile in London, which had strong links to the underground government and the Resistance, including the Home Army, or Armia Krajowa (AK), in Poland. For the war's duration, Poles made a major contribution to the Allied cause in Europe; in Britain thousands served in all the armed forces.

Five years after the catastrophic events of 1939, it was the Soviets – having suffered a brutal Nazi invasion of their own – who managed to push the mighty German army all the way back to the border with Poland. Polish armies – formed with soldiers released from Soviet jails and camps – supported the Red Army in its final drive against the Nazis.

While the Armia Krajowa did everything they could to liberate the country themselves, in the end their efforts simply assisted the Red Army in their defeat of the Germans in Poland. The Poles were about to replace one occupier with the another, paving the way for 35 years of Soviet domination.

By the end of August 1943, the tide had turned in the Soviets' favour in their fight to repel the Wehrmacht from Russian soil. The Red Army was now on the offensive and it soon became apparent that they, rather than the western Allies, would be the ones to end German occupation in Poland.

On 22 June 1944, two weeks after the Allied landings at Normandy, the Russians launched their own D-Day in Belarus, Operation Bagration. It was made up of several offensives operating concurrently and stretched across a wide front. One of these, the Minsk Offensive, completely destroyed the only major German force left on Soviet soil, Army Group Centre, and was one of the greatest Soviet victories of the war. It was achieved partly by sheer weight of numbers, but also by a deception plan that fooled the Germans into thinking the major attack would happen further south. Minsk was liberated on 3 July, opening the way for the Red Army to enter Poland, and on 18 July an assault was launched on the eastern Polish city of Lublin.

The Lubelskie province, of which Lublin is the capital, was, and still is, one of the richest agricultural areas of Poland. This made it a prime target for German colonization after the Nazi invasion, the aim being to remove both the Polish and Jewish populations. Jews – targeted almost immediately the war began – were initially sent to the Lublin Reservation – a large segregated Jewish “state” populated by Jews deported from across Europe, and used as a forced labour camp.

When the reservation idea proved unworkable, it was replaced by isolating Jews in enclosed ghettos. The Lublin ghetto was set up in March 1941 in the district of Podzamcze on the site of the former Jewish district; it held in excess of 30,000 people in a handful of streets, mostly Jews but with some Roma people. Though cramped and vulnerable to the spread of disease, it was regarded as less dreadful than other ghettos.

The Lublin ghetto was liquidated after about a year as part of Aktion Reinhard, the planned extermination of all Jews within the General Government. This entailed the building of a series of death camps. The first, completed in March 1942, was near the village of Bełżec about halfway between Lublin and Lwów (now Lviv in Ukraine). The second at Sobibór was due east of Lublin and close to the border with Ukraine and Belarus, and the third at Treblinka, midway between Warsaw and Bialystok. In addition, the Majdanek concentration camp on the outskirts of Lublin – originally a labour camp for Soviet POWs – was converted into an extermination centre. It is thought that Aktion Reinhard was responsible for the murder of about 1.7 million Jews, and an unknown number of Poles, Roma and Soviet POWs.

In 1942 a mass deportation of Poles from the Zamość region was carried out: inhabitants of around three hundred villages were removed and replaced by German settlers. This prompted a major uprising spearheaded by the Home Army and other groups, who encouraged villagers to destroy their properties before leaving. Some deportees were screened as potential candidates for Germanization on the basis of background or “Aryan” characteristics. Those that failed the test were sent to Majdanek. As many as 250,000 villagers managed to evade capture, seeking shelter wherever they could, some hiding in forests with the partisans. The Resistance continued to harry German troops and colonists over the next two years, but were eventually defeated with heavy casualties at the Battle of Osuchy in June 1944.

On 18 August 1944, Marshal Rokossovsky’s 1st Belorusian Front (equivalent to a Western army group) launched the Lublin-Brest Offensive. Part of Operation Bagration, five of its armies – including the Soviet-trained Polish First Army led by General Berling – broke through the German Army Group North Ukraine close to Kovel, 160km east of Lublin.

The River Bug – which marked the border with the General Government – was crossed by the Soviets’ Forty-seventh Army and the Eighth Guards Army on 21 July; Chełm was liberated on 22 July. It was here, on the same day, that the Soviet-backed Polish Committee for National Liberation (also known as the Lublin Committee) issued a manifesto, urging support for the Red Army and the Home Army, but at the same time denouncing the London government-in-exile and setting itself up as the new provisional government.

Lublin was entered by the troops of the Second Tank Army the next day. In the fighting, the Army’s commander, Soviet General Bogdanov, was wounded. He was replaced by General Radzievsky, who was immediately ordered by the Stavka (the Soviet High Command) to head north with his troops towards the River Vistula and Warsaw.

The Lublin camp of Majdanek was liberated by Red Army troops, but not before the Germans had tried to destroy it, evacuating or killing the remaining inmates. Only a few hundred were left, mostly hospitalized Soviet POWs. Majdanek had been used as a storage depot for objects stolen from victims; the Red Army found thousands of shoes, spectacles and human hair, along with piles of ash. They also found gas ovens. This was the first evidence of mass killings, and was soon reported to a shocked world by journalists flown over from places like Moscow and New York.

Lublin was renowned as a Jewish cultural centre before the war, with a population of 40,000, twelve synagogues and two Yeshivas – schools for religious study. The Jewish district was near the castle where the ancient Grodzka Gate marks the divide between the Jewish and Gentile sections of the city. Part of the gate is now used as a study centre and exhibition space dedicated to Lublin’s lost Jewish heritage. It’s run by a drama group, Teatr NN, which also organizes performances, educational events and tours. Both the Old Jewish Cemetery (ul. Kalinowszczyzna) and the New (ul. Walecznych) still survive, despite Nazi desecration. So does the Yeshiva Hahmei Lublin (ul. Lubartowska) and its synagogue. Lublin’s Great Synagogue was used by the Nazis during the liquidation of the ghetto as a collection point for Jews prior to transportation; it was then destroyed.

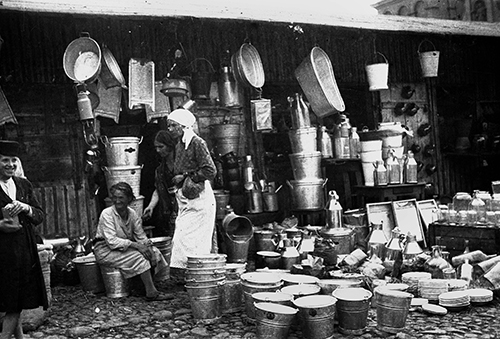

Credit: Getty Images

The Lublin ghetto

Following the fall of France, Poland became Britain’s most important ally. Its government-in-exile, based in London, provided military support and had close links to the resistance Home Army in Poland. But with the Soviet Union’s entry into the war everything changed, not least for the Poles: overnight, an enemy – the co-invader of their country – had become an ally, someone they had to negotiate with. General Sikorski, the Polish prime minister, signed a Polish-Soviet Treaty in July 1941 which resulted in the release of over one million Polish citizens from Soviet jails and the formation of a Polish army in Russia, led by General Anders.

What Sikorski completely failed to do was get an agreement with Stalin about the Polish-Soviet frontier, and relations between the two countries soon soured. The situation worsened with the discovery in 1943 of the remains of some four thousand Polish officers murdered by the Russians. Stalin used the breakdown in relations to reinforce the activities of the Communist Polish Workers’ Party in Poland. When Sikorski was killed in an aircraft accident in July 1943, the new prime minister, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, made a desperate attempt to negotiate with Stalin about the make-up of any postwar Polish government.

By now it was too late. The Red Army had begun to turn back the tide of the invading Germans and was scenting victory. At the Tehran Conference in November 1943 – attended by all the “Big Three” leaders but with the Poles excluded – the Allies decided that the frontier should follow the “Curzon Line” suggested in 1918, in other words the Soviets would retain the territory they seized in 1939 but shift the Polish-German border westwards. By July 1944 Stalin had already established a small group of Polish communists in Poland, known as the Lublin Committee, who issued a Manifesto of the Polish People (despite representing hardly any of them).

Though the Red Army’s progress through Poland was aided by the Home Army, Stalin responded by refusing his troops permission to assist in the Warsaw Uprising and then, in the aftermath, arrested thousands of Home Army members. These people were either imprisoned or shot. The Lublin Committee now became a provisional government; other political parties were marginalized; and the government-in-exile ignored. In July 1945 Stalin’s ruthless fait accompli was reluctantly recognized by Britain and the USA. Poland would remain as a Soviet satellite state until 1989.

Droga Męczenników Majdanka 67, Lublin, ![]() majdanek.eu/en

majdanek.eu/en

Majdanek is just a few kilometres southeast of the city centre. Tens of thousands of Jews and other “undesirables” were brought here, not just from Lublin but from across occupied Europe. Initially it housed Soviet POWs, most dying of cold or disease. Overall 78,000 people are thought to have been killed here, three-quarters of them Jews. After the Soviets liberated the camp, they used it to imprison members of the Polish Resistance, then opened it as a museum in November 1944. A long path runs through the site, with the Fight and Martydom monument at one end and a domed mausoleum containing the ashes of the dead at the other. Quite a few of the original buildings survive, including the gas chambers and crematoria, and the museum contains a range of displays that record and memorialize the horrors that took place here.

ul. Ofiar Obozu Zagłady 4, Bełżec, ![]() belzec.eu/en

belzec.eu/en

Close to the Ukrainian border, some 40km south of Zamość, the Bełżec extermination camp was only fully commemorated 63 years after the Nazis attempted to erase all traces of it. Mass deportations from the ghettos of Lublin and Lwów began in March 1942 and ended in December, when the camp was closed down. In that ten-month period, around 450,000 people, mostly Jews, were murdered. Because little visible evidence remained, the site has been completely transformed into a powerful memorial, which combines architecture and symbolism to striking effect. As visitors walk the sloping path to the wall of remembrance, the walls on either side seem to rise up, creating a feeling of claustrophobia. The museum provides a history of the camp and displays objects found during archeological excavations. Guided tours are available but need to be booked in advance.

About 45km due west of Bełżec is the village of Osuchy, the scene of one of the biggest battles fought by the Polish Resistance. In June 1944, the Germans launched a major anti-partisan offensive, Aktion Sturmwind II, in an attempt to suppress the Zamość Uprising. Much of the fighting took place in the heavily wooded Solska Wilderness. Outnumbered and surrounded, all attempts by the Resistance to break through failed. Around 400 died in the fighting, while the 800 who surrendered were executed or imprisoned. The cemetery contains a memorial and over 300 partisan graves.

Stacja Kolejowa Sobibór 1, Włodawa, ![]() sobibor-memorial.eu/en

sobibor-memorial.eu/en

Like Bełżec, the death camp at Sobibór was located at an isolated spot, close to the Ukrainian and Belarusian borders, about 50km north of Chełm. The second of the Aktion Reinhard camps to be operational, Sobibór was completed in May 1942 when the first transports arrived. The number of deaths is estimated at between 170,000 and 250,000. A revolt in October 1943, in which three hundred prisoners managed to escape, led to the camp being closed and largely destroyed. The remaining inmates were transferred to Treblinka. The site is currently closed while a new memorial museum is constructed.

Many Poles realized that the imminent arrival of the Red Army would jeopardize any chance of re-establishing Poland as an independent democratic nation.

Instead of a general insurrection against the Germans, in 1944 the Home Army launched Operation Tempest, a series of assaults in support of the advancing Red Army. It was hoped that this would establish common cause with the Soviets but, at the same time, show the Polish underground to be a significant political and military force in its own right, capable of taking over the country when the war was over.

Despite military success fighting alongside the Soviet forces, the Poles gained no political advantage. On the contrary, when campaigns were finished, Home Army soldiers were disarmed and given a choice by the NKVD (the Soviet Secret Police) of either joining the Polish First Army of General Berling, or facing arrest and almost certain deportation. In some cases, Home Army soldiers were executed.

The Warsaw Ghetto was established in October 1940 in the Muranów district and enclosed within 3-metre-high walls. It was the largest ghetto in Europe, housing over 400,000 people, many living ten to a room. Malnutrition and disease were widespread, and by summer 1942 had reduced the population by twenty percent.

At this point, the Nazis began a mass deportation of Jews from the ghetto to the extermination camp at Treblinka, murdering around 300,000 people. On 19 April 1943, when Waffen-SS troops arrived to remove the remaining inhabitants, armed resistance broke out organized by the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) led by Mordechai Anielewicz. Despite the lack of adequate weapons, the ghetto uprising was sustained for almost a month, its leaders preferring to commit suicide rather than surrender. The 50,000 still alive when the uprising was suppressed were either executed or deported to death camps.

Having reached Lublin, the 1st Belorusian Front continued west and north with the aim of establishing bridgeheads on the Vistula, the river that runs the length of Poland. By the end of July, the Second Guards Tank Army, commanded by Soviet Major General Radzievsky, had reached Garwolin – 60km southeast of Warsaw – where it engaged with and routed the German 73rd Infantry Division. The right flank of the Second Guards Tank Army was meant to be protected by the Forty-seventh Army, but a series of German counteroffensives to the east and northeast of Warsaw, including a major tank battle at Wołomin, forced a Soviet withdrawal.

The Red Army was within striking distance of Warsaw, and Moscow Radio urged the city’s inhabitants to rise up against their oppressors. This posed a terrible dilemma for the Home Army: should it engage with a ruthless enemy vastly superior in arms and numbers, running the risk of defeat and great loss of life, or do nothing and wait for the Russians to arrive, with the likelihood of being branded as Nazi collaborators? The London government-in-exile approved an uprising, and at 5pm on 1 August the Home Army’s commander, General Bór-Komorowski, ordered the go-ahead.

The uprising began with an attack on the German garrison, and for the next 63 days the Home Army and other insurgents attempted to drive the occupying forces from the city. Though they met with some early success, the odds against them were overwhelming. The Germans had brought in reinforcements and began pushing back the Poles street by street, slaughtering any civilians they encountered. The district of Wola was subjected to the most brutal treatment, with an estimated 50,000 people murdered over ten days in August. Throughout the uprising the insurgents used the city’s sewer system as a way of moving from district to district, despite the narrowness of many of the tunnels, and at the end of August the sewers were used to evacuate more than five thousand people from the Old Town to the Zoliborz district.

Credit: Getty Images

Sick and starving people emerge from basements and sewers in Warsaw, two months after the start of the Warsaw Uprising

Although close by, the Red Army failed to assist the uprising. The widely held view is that this was deliberate. Initially Stalin would not even allow American and British supply planes to land in Soviet-held Polish territory. Some Allied air-drops did take place, but they were largely ineffective as much of the material landed in German-occupied areas. Attempts by Berling’s Polish First Army to cross the Vistula proved unsuccessful.

By the end of September, the Home Army was running out of weapons and men, and on 2 October Bór-Komorowski signed the capitulation. He and his remaining troops became prisoners of war; most of the civilian population were transported either to concentration camps or as forced labour to Germany. Hitler then ordered the destruction of Warsaw. One of the most beautiful capitals in Europe was plundered of anything valuable and then systematically dynamited, building by building, by a specialist SS detachment. Three months later, 85 percent of the city had been destroyed, at which point – in January 1945 – the Red Army entered to “liberate” a vast pile of smoking rubble.

For any Poles caught assisting Jews, or even suspected of doing so, the sentence was death for them and their family. This was usually immediate, without any legal process. Despite all of this, many Christian Poles risked their lives helping Jews out of a sense of common humanity and moral outrage; Irena Sendler was one of them. Working with Żegota, the codename for the Council for Aid to Jews (Rada Pomocy Zydom), Sendler, a social worker, helped to smuggle babies and small children out of the Warsaw ghetto, and set up a network of private houses, religious institutions and orphanages that could take in and hide them. Many Catholic clergy and nuns assisted her. It was a highly risky enterprise, which involved giving the children Christian names, teaching them prayers, and coaching them how to behave under Gestapo questioning. Often children needed to be moved from one place to another at regular intervals. Sendler was insistent that the children be reunited with their families after the war and wrote all their names down and hid them in bottles which she buried. Nearly all the parents of those children Żegota saved were killed at Treblinka.

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

ul. Anielewicza 6, Warsaw, ![]() polin.pl/en

polin.pl/en

Housed in a striking new building located on the site of Warsaw’s Jewish quarter (later the ghetto), the POLIN Museum outlines the history of the Jewish presence in Poland from the early Middle Ages to the present day. Its core exhibition is made up of eight galleries displaying a wealth of artefacts and multimedia displays, including a stunning replica of the ornately painted ceiling of the 17th-century Gwoździec Synagogue, destroyed in 1941. The Holocaust has a whole gallery dedicated to it, but the museum as a whole is as much a celebration of the Jewish contribution to Polish history as it is a memorial to its passing.

Standing in front of the POLIN Museum, this monument was erected in 1948 on the fifth anniversary of the ghetto uprising. A large monolithic wall, it has sculptural reliefs on either side, one depicting a line of deportees being taken away, the other a group of ghetto insurgents with a defiant Mordechai Anielewicz clasping a grenade. The monument was constructed from stone imported by the Nazis in anticipation of refashioning Warsaw as a German city.

Beginning at the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, the Path of Remembrance is a memorial route marked by sixteen granite blocks, each one commemorating a significant person or organization in the ghetto’s history. Along the way you pass the bunker of the Jewish Fighters Organization (ŻOB). The route ends at the Umschlagplatz Monument, the assembly point near the train station from where thousands of Warsaw Jews were transported in crowded cattle trucks to the extermination camp at Treblinka.

A few small sections are all that survive of the 3-metre wall built by the Nazis to enclose the Warsaw Ghetto. Two can be accessed via a courtyard at ul. Sienna 55 and ul. Złota 62. Information plaques provide details of life in the ghetto and a map shows the area it occupied.

ul. Grzybowska 79, Warsaw, ![]() 1933.pl/en

1933.pl/en

The aim of this museum is to tell the story of the Home Army and the citizens who supported it in the largest anti-German uprising in occupied Europe. Located in a former power station, the museum contains a wide range of exhibits and experiences, including a recreation of parts of the sewers and a replica B-24 bomber, the plane that took part in the Warsaw airlift. The rooms are arranged chronologically and much of the emphasis is on the activities of ordinary citizens, in the form of audio-visual displays and personal stories. The many photographs by Eugeniusz Lokajski, a commander during the uprising, provide a vivid record of the terrible suffering that Warsaw’s population endured in the face of sustained German brutality.

Credit: Shutterstock

Warsaw Rising Museum

Completed in 1989, this monument was a belated and controversial attempt by the communist regime to acknowledge the heroism displayed in the uprising. It’s made up of two separate bronze sculptural groups: one representing a group of armed insurgents rushing forward from slabs of a collapsing building, the other showing soldiers assisting a mother and baby descend into the sewers, as a priest prays close by.

The Wola massacre ranks as one of the most sadistic and ruthless assaults against civilians of the entire war. Beginning on 5 August, groups of German soldiers moved through the western district systematically killing its inhabitants, irrespective of age, gender or involvement in the uprising. The most notorious unit – led by the sadistic Oskar Dirlewanger – went on a spree of torture, rape and murder. It is estimated that around 50,000 people were killed. The monument to the massacre, dedicated in 2006, represents a fragment of broken wall, on one side of which are the ghostly indentations of ten human figures.

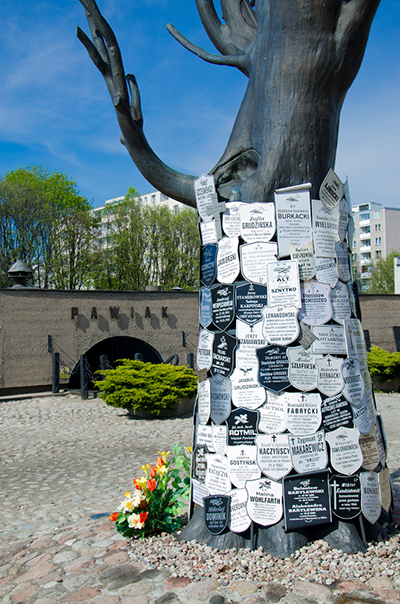

ul. Dzielna 24/26, Warsaw, ![]() muzeum-niepodleglosci.pl/pawiak

muzeum-niepodleglosci.pl/pawiak

A vast, 19th-century Tsarist prison, Pawiak was used by the Gestapo for holding and torturing Polish political prisoners. Over 100,000 people spent time here during the war, of whom around 37,000 were executed within the prison grounds. The Germans dynamited the whole building before retreating in 1944 and now only part of the main gateway and a few cells remain. The museum, housed in a separate building, tells the story of Pawiak and its inmates through photographs of prisoners, their personal effects and some reconstructed cells.

Credit: Shutterstock

Memorial tree at Pawiak Prison Museum

The imposing Ministry of Education building was used as the Gestapo headquarters during the war and now contains a small museum tucked away in a basement (entered through a door in the courtyard). There is only one route through the claustrophobic space, which contains some of the original holding cells and the interrogation room, complete with instruments of torture. The nightmarish atmosphere is heightened by the use of striking visual and sound effects, and some will find the experience distressing. Children under 14 years are not admitted.

ul. Jana Jeziorańskiego 4, Warsaw, ![]() muzeumkatynskie.pl

muzeumkatynskie.pl

During the spring of 1940, in the Katyń forest near Smolensk and at other locations, more than 20,000 Poles, including 10,000 army and police officers, were executed by the NKVD (the Soviet secret police) – a mass execution known collectively as the Katyń Massacre. The first bodies were discovered by the Germans in 1943, but the Russians only admitted culpability in 1990. The museum commemorating the victims has recently been relocated to the Citadel fortress, where it is housed in a newly designed exhibition space that includes a small park. The displays, which use music and a soundscape, outline the events leading up to the massacre from the Nazi-Soviet pact onwards, but it’s the many personal belongings found on the exhumed corpses that have the most powerful impact.

Credit: Getty Images

Personal belongings and papers of Polish officers killed in the Katyń Massacre

Palmiry National Memorial & Museum

Palmiry, Czosnów, ![]() palmiry.muzeumwarszawy.pl/en

palmiry.muzeumwarszawy.pl/en

Mass executions of Warsaw’s Polish elites were carried out in secret by transporting prisoners to a forest near the village of Palmiry west of the city. The blindfolded prisoners were lined up in front of long ditches which they fell into as they were shot. An estimated two thousand people were murdered here, many buried in the nearby cemetery. There is now a striking museum: its austere exterior of rusted steel is punctured by symbolic bullet holes, while the interior creates a more tranquil environment with a glass wall looking out on to the forest. The display contextualizes the murders but also tells how the forest was used by Polish Resistance forces to train and to hide weapons.

Credit: Shutterstock

Lines of gravestones at Palmiry National Memorial & Museum

Treblinka, Kosów Lacki, Wólka Okrąglik 115, ![]() treblinka-muzeum.eu

treblinka-muzeum.eu

Located about 100km northeast of Warsaw, Treblinka was, after Auschwitz-Birkenau, the extermination camp that saw the greatest number of killings as part of Aktion Reinhard. Around 800,000 Jews were murdered here, along with some 2000 Romani. There were two camps: Treblinka I, built in November 1941, was a forced labour camp for Poles and Jews; Treblinka II, 2km to the east, was added as an extermination centre in April 1942. Most of the Jews deported here came from the ghettos of Warsaw and Radom. In April 1943 Jewish prisoners organized a revolt and three hundred managed to escape, though most were recaptured. The Germans started dismantling Treblinka II shortly afterwards, forcing surviving inmates to exhume and burn corpses. When the Red Army arrived in July 1944, much of the camp had disappeared.

Today the emptiness and isolation of the site is powerfully affecting. A small museum near the car park has a few exhibits, including archive photos and a scale model of the camps. The large stone memorial is surrounded by a field of smaller stones marked with the names of the cities and villages from where the victims came.

The capture of Warsaw ended the Lublin–Brest Offensive and signalled the beginning of the Vistula–Oder Offensive, the final massive Soviet thrust against the Germans through Poland to the River Oder and into Germany.

Stalin had over six million soldiers at his disposal; Hitler had just over two million. Nevertheless, Hitler called the Soviet build-up in the central sector of the Eastern Front “the greatest bluff since Genghis Khan”, and refused to withdraw troops from any territory where they were active, thus increasing the risk of his armies being isolated, cut off and destroyed.

On 12 January 1945, the Vistula-Oder Offensive was launched in the south by Marshal Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front. Two days later Marshal Zhukov, commanding the 1st Belorusian Front, began advancing due west from the centre. The attack in the north, which began on 13 January, was the responsibility of two fronts: the 2nd and 3rd Belorusian Fronts would advance on East Prussia, after which the Second, commanded by Marshal Rokossovsky, would continue on to East Pomerania.

The Polish part of Pomerania had been annexed by Germany since 1939; for the battle-scarred Soviet troops, Pomerania was, as much as Prussia, the Fatherland of the hated enemy, an enemy that had committed barbaric acts against their country. Most would have witnessed the aftermath of terrible atrocities, and in some cases been personally affected by them. Unsurprisingly, thoughts of revenge were uppermost in many soldiers’ minds, and to a large extent were encouraged by Soviet anti-Nazi propaganda. In East Prussia evacuation of civilians was slow in happening, and the inhabitants of many villages and towns were subjected to the full brunt of Soviet carnage, arson and mass rape.

On 1 September 1939, the German battleship SMS Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Military Transit Depot at Westerplatte peninsula at the mouth of the River Vistula. In the face of heavy bombardment and attacks from the air, the small Polish garrison held out for seven days before the hopelessness of their situation forced their commander to surrender.

At the same time, the Polish Post and Telegraph Office in Danzig was attacked by a local SS unit and the police, a force of around two hundred men. The building had been fortified in anticipation of war and some of its workers had received military training. With a handful of others, they managed to put up fierce resistance which lasted around fifteen hours. It was only overcome when the Germans pumped petrol into the basement and ignited it. Those not killed in the attack were tried and sentenced to death as illegal combatants. Both Westerplatte and the Post Office Siege became potent symbols of Polish resistance.

The main strategic aim of the East Pomeranian Offensive was to overcome the German forces in Pomerania so as to eliminate the risk of a counteroffensive against Marshal Zhukov’s advance on Berlin. As each town was overcome, the German Army retreated and many German civilians fled with them. The coastal town of Kolberg (modern Kołobrzeg) experienced a ferocious siege in the first two weeks of March, during which time the Germans evacuated around 70,000 civilians and about 40,000 troops by sea to Germany and Denmark. Many ships carrying thousands of refugees were sunk by Soviet submarines. The other Baltic ports of Gdynia and Danzig (Gdańsk) were no less fiercely defended against the vengeful onslaught of Russian and Polish troops. Apart from a handful of German soldiers on the Hel peninsula who battled on until May, this left Poland free from Nazi occupation. It was a freedom that was shortlived, however, as Nazi subjugation was replaced by Soviet domination.

Credit: iStock

Monument of the Coast Defenders

Erected in 1966 during the communist era, this monument is a tall, chunky Soviet-style structure dedicated to the coastal defenders of World War II in general, rather than the Westerplatte garrison in particular. Nearby exhibition panels explain the modern history of the peninsula. Some of the ruined guardhouse and barracks are still standing and one building is now a small museum telling the story of the events that took place here in the first week of September 1939. Memorials are spread across the peninsula and it takes a couple of hours to see them all. Westerplatte can be reached by bus or boat from Gdańsk.

On the 40th anniversary of the Post Office workers’ defence of their building, a small museum was opened to commemorate the events that occurred here, with a monument erected in the adjacent square. The exhibition contains a wealth of documents and evocative photographs, as well as a copy of the plan of the attack, drawn up in July 1939. Other material, including a reconstruction of the postmaster’s room, outlines the history of the Polish postal service and the wider Polish community in Danzig/Gdańsk.

Museum of the Second World War

pl. Władysława Bartoszewskiego 1, Gdańsk, ![]() muzeum1939.pl

muzeum1939.pl

A spectacular tower, tilting at a seemingly impossible angle, is the dominant feature of this new museum, designed by a local architecture firm. Most of the permanent exhibition is actually located underground (the tower is used as offices). The original concept of the displays sought to place the Polish experience of World War II in a broad international context, with an emphasis on the lives of ordinary citizens, while also looking at current conflicts. Immediately after it opened in 2017, the Minister of Culture criticized the museum as insufficiently patriotic and sacked the director and his deputies. Despite the political controversy, the museum is well worth visiting, with thousands of objects imaginatively displayed. It’s an immersive experience, with recreations of whole streets, organized in three narrative themes: “The Road to War”, “The Terror of War” and “The Long Shadow of War”.

Credit: iStock

Museum of the Second World War

ul. Muzealna 6, Sztutowo, ![]() stutthof.org/english

stutthof.org/english

The day after the German invasion, Stutthof, to the east of Danzig, was established – the first Nazi internment camp outside of Germany. It was used to imprison and then kill Polish professionals and the intelligentsia. Less well known than other Nazi camps, Stutthof grew in five years from a camp housing mainly local Poles to an extermination camp, with 39 sub-camps, containing tens of thousands of prisoners from across Europe. The museum researches and displays archival records and historical artefacts relating to the camp and its administration. Exhibitions, films and photographs provide a haunting insight into the lives of the 110,000 people that were imprisoned here during World War II before its liberation by Red Army troops in May 1945.

ul. Św. Jacka 11/2, Wejherowo, ![]() muzeupiasnickie.pl

muzeupiasnickie.pl

In a forest near the village of Piaśnica, close to the port of Gdynia, between 10,000 and 12,000 people are estimated to have been murdered between September 1939 and April 1940. The perpetrators were the SS, assisted by local German paramilitaries. Those killed included Kashubians (a local ethnic group), Polish intellectuals, Catholic priests, Jews, Czechs and patients from mental hospitals. At the end of the war, as the Red Army approached, the Nazis forced Stutthof prisoners to dig up the corpses and burn them. In the forest, 9km to the north of Wejherowo, there is now a commemorative grave site for the victims, with a monument and a nearby chapel. The Piaśnica Museum in Wejherowo is currently housed in a temporary site while its intended location (the former Gestapo headquarters) undergoes restoration.

›› The Wolf’s Lair and the July Plot

In the run-up to the 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa), a large military complex was built as Hitler’s principal command base near Rastenburg in East Prussia (now the Polish town of Kętrzyn). Hidden by thick forest, it was known as the Wolfschanze, or Wolf’s Lair. Hitler spent more time here – over 800 days – than at any of his other military bases. In 1944, the living quarters of Hitler and other leading Nazis were replaced with large, heavily reinforced bunkers in anticipation of Allied air attacks.

As it turned out, the attack on Hitler came not from the Allies but from his own side. On 20 July, a staff officer, Lieutenant Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, attended a meeting at the Wolf’s Lair, where he planted a bomb hidden in a briefcase a few feet from where Hitler was sitting. He then left the room and, after the explosion, flew to Berlin in the belief that the Führer was dead. He wasn’t, and shortly afterwards Stauffenberg and the other ringleaders of the plot (code-named Valkyrie) were arrested and summarily executed. The Gestapo then pursued anyone connected, even remotely, to this and earlier plots, and around five thousand people were eventually killed, either by suicide or execution.

The conspirators were motivated by a number of factors. As senior officers, they were appalled at the disastrous way in which the war was progressing, especially on the Eastern Front, which they ascribed to Hitler’s poor military leadership. To some extent, they were also alarmed at the extremes of brutality meted out by the Waffen SS against Jews and Slavs in the latter years of the war. But they were all conservative nationalists, many of whom had supported the Nazi cause for most of their careers, and their plans for a negotiated peace included retaining Austria and the Sudetenland. Unquestionably the plotters were brave – Stauffenberg in particular – but whether their actions were heroic is something that is still debated by historians and Germans alike.

al. Jana Pawła II 1, Gdynia, ![]() muzeummw.pl

muzeummw.pl

Built in Britain and launched in 1936, ORP Błyskawica was the most modern surface ship of the prewar Polish Navy; today, she’s the oldest surviving destroyer in the world. Shortly before the German invasion, she left the Baltic along with two other Polish destroyers and sailed to Britain where she served under the operational control of the Royal Navy. Błyskawica took part in several major operations, including the Allied invasion of Normandy where she provided cover for the landing forces. Now a museum, much of the ship can be explored by visitors, including the engine room, and there are displays about Błyskawica’s service during the war.

About 600,000 Russian soldiers fell as the Red Army advanced through Poland in 1944–1945. Some 3100 are buried in this cemetery, many of whom died in the bitter fighting to win Gdańsk. Each soldier’s grave is marked with a star. Since the fall of communism in 1989, Soviet monuments have become a contentious issue and some of the more political ones have been removed. At the moment Soviet cemeteries continue to be respected, although there have been instances of vandalism.

Credit: Alamy

Visitors to the Wolf’s Lair

The ruins of Hitler’s secret headquarters (see box) are located close to the village of Gierłoż, about 225km east of Gdańsk and close to the border with Kaliningrad. Wandering through the compound, which contains around eighty buildings, is an eerie experience. As the Red Army approached, Hitler ordered its complete destruction by an SS team, a difficult task considering that many of the bunkers had walls over five metres thick. Nature has now invaded the remains, covering much of the site in dense foliage. Only a wall survives of Hitler’s bunker, but that of Goering is almost complete; a plaque marks the location of the failed assassination attempt and there is a small on-site exhibition.

Kraków and southeastern Poland

On 13 July 1944, at the southern section of the Russian front, a major offensive was launched with the aim of driving the German Army Group North Ukraine from western Ukraine and southeastern Poland.

The Lwów–Sandomierz Offensive, as the plan was codenamed, was also partly conceived as a deception to lure enemy troops down from the north, leaving German Army Group Centre even more vulnerable for attack. The operation was assigned to the 1st Ukrainian Front led by Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev. The Germans, commanded by General Josef Harpe, offered strong resistance, but were surrounded and routed near the town of Brody. The Polish Home Army began an uprising in Lwów (Lviv) on 23 July as the Soviets advanced, and the city was liberated three days later. Red Army bridgeheads were established on the Vistula on 28 July near Baranów Sandomierz. The Germans launched a major counterattack in August in an attempt to push the Russians back across the river, but the Soviets held their position. Both sides dug in until January, when Konev’s troops began their advance across southern Poland.

Credit: Getty Images

Soviet soldiers in liberated Kraków

Kraków, rather than Warsaw, had been the capital of the newly formed General Government. It was governed by Hitler’s lawyer, Hans Frank, who had installed himself in the magnificent Wawel Castle, the former residence of Poland’s royalty. On 17 January 1945, as the Soviets approached, Frank and his administration fled, leaving General Wilhelm Koppe to organize the German military defence and withdrawal. Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front approached from the north and Major General Ivan Korovnikov’s Fifty-ninth Army from the northeast. Soviet accounts of the battle for Kraków claim that the speed of Konev’s attack saved it from the destruction suffered by so many Polish cities. In 1987, a statue was raised in Konev’s honour. It was pulled down four years later, and most Polish historians now think there were no plans by the Germans to blow up the city, and regard the story of Konev as Kraków’s saviour as a myth.

›› Kraków’s ghetto and Oskar Schindler

Prior to the 1939 invasion, Kraków had around 70,000 Jewish inhabitants, about a quarter of the population, many of whom lived in the traditional Jewish district of Kazimierz. In March 1941, 16,000 were relocated to a newly created ghetto in the Podgorze district south of the city, housing about five times the number that had lived there previously. Only one non-Jew chose to remain: Tadeusz Pankiewicz, a Catholic Pole who ran a pharmacy, known as the Pharmacy Under the Eagle. As well as providing medical advice and medication to residents – often without charge – Pankiewicz and his three female assistants risked their lives hiding Jews and helping them to escape.

Forced to work in factories both inside and outside the ghetto, after June 1942 many ghetto inmates were sent to the labour camp at nearby Płaszów. Conditions there were harsh and treatment exceptionally brutal, even by SS standards. At the limestone quarry, prisoners were worked to the verge of death, and random beatings and shootings were commonplace – many carried out by Amon Goeth, the camp’s sadistic commandant. The Kraków ghetto was liquidated in 1943. The 8000 prisoners still able to work were transferred to Płaszów, the rest were either shot or sent to the death camps of Bełżec or Auschwitz-Birkenau.

One of the factories was Oskar Schindler’s Emalia Factory, a previously Jewish-owned enamel business purchased by him in 1939. Schindler, who had once been a spy in Czechoslovakia, was a Nazi Party member and a wheeler-dealer businessman who enjoyed the good things in life. Despite his dubious credentials, he viewed the treatment of the Jews with horror, and did his utmost to protect his workers. When the ghetto was liquidated, he used bribery, contacts and charm to make sure that none of the Emalia Jews were deported. When Płaszów became a concentration camp in August 1943 he had his factory designated a sub-camp where the workers could reside. Arrested three times, he always succeeded in getting the charges dropped. In October 1944, when the arrival of the Red Army seemed imminent, the SS removed all Jews from the Emalia Factory to Płaszów, but Schindler somehow managed to get permission to relocate the factory (now producing armaments) to Brünnlitz in Moravia. “Schindler’s List” contained the names of the 1200 workers that he insisted would be needed there – Jews who otherwise would have met their deaths at Auschwitz or Gross-Rosen.

Early in 1940, a former Polish barracks at Oświęcim, around 70km from Kraków, was converted into a concentration camp and given the German name Auschwitz. For the first year of its existence, most of its inmates were Polish political prisoners. Conditions were extremely harsh and the demands for forced labour at local factories meant that the camp was regularly expanded. In October 1941 work started on another camp nearby, Auschwitz-Birkenau, to accommodate Soviet prisoners of war. Around the same time tests for the gassing of “undesirable” prisoners, using Zyklon B, had already begun. Auschwitz III was a large industrial complex, built for I.G. Farben, which used slave labour.

In the spring of 1942, transports of Jews began to arrive at Auschwitz as part of the Nazis' “Final Solution”. As the numbers of Jews from across Europe increased, so the machinery of murder became more efficient. Some prisoners were also selected for cruel and deadly pseudo-medical experiments conducted by camp doctors. An estimated total of 1.3 million people (Poles, Jews, Roma, Soviet POWs and others) were sent to Auschwitz, of whom 1.1 million were killed; of these, 960,000 were Jews.

The Red Army liberated Auschwitz on 27 January 1945. Before they arrived, the Germans scrambled to destroy all evidence of their crimes, killing thousands of prisoners and taking 60,000 others on a forced march westwards. Around 15,000 died, either shot because they couldn’t keep up, or simply succumbing to malnutrition, disease and the freezing winter weather.

Kraków and southeastern Poland sites

ul. Wita Stwosza 12, Kraków, ![]() muzeum-ak.pl/english

muzeum-ak.pl/english

Housed in an austere red-brick former Austrian barracks, and slightly off the beaten track, this is the only museum entirely dedicated to Poland’s underground government and resistance army. The many objects on display range from personal memorabilia and photographs to weaponry, including the reconstruction of a V2 rocket. You enter through a large, light-filled courtyard, but most of the collection is displayed in the dimly lit basement with only a limited amount of explanation in English. With this in mind, it’s well worth taking a guided tour of the museum, which requires advanced booking.

Pomorska Street (Gestapo Museum)

ul. Pomorska 2, Kraków, ![]() mhk.pl/branches/pomorska-street

mhk.pl/branches/pomorska-street

The Dom Śląski (Silesian House) was a hostel for Silesian students before it became Kraków’s Gestapo headquarters in 1939. It is now a museum with a permanent exhibition entitled “People of Kraków in Times of Terror 1939-1945-1956”, which tells of the suffering endured by Kraków’s citizens under both the Nazi regime and during the postwar Stalinist tyranny. The emphasis is on the human cost of institutionalized cruelty: a wall of faces lines the entrance corridor – official mugshots of concentration camp inmates – and in the basement the cell walls are covered with the scratched names of those held and tortured here.

Kazimierz is now one of the most vibrant districts of Kraków, as it was in the prewar years as the city’s historic Jewish quarter and one of the great centres of European Jewry. The Nazis displaced and then murdered its inhabitants, but left most of Kazimierz’s buildings standing, although they plundered or destroyed nearly all its treasures. Wandering the streets gives some sense of what was prewar life was like. Of its seven synagogues, two now serve the city’s small Jewish community, while the grandest, the Old Synagogue, is a fine Renaissance building, heavily damaged by the Nazis, but restored in the 1950s and now a museum.

Credit: Liberation Route Europe

The haunting entrance to Auschwitz-Birkenau

ul. Dajwór 18, Kraków, ![]() galiciajewishmuseum.org/en

galiciajewishmuseum.org/en

This museum, housed in a former warehouse, was founded in 2004 by British photographer Chris Schwarz to commemorate the lost Jewish world of Galicia, a Habsburg Empire province and former kingdom that stretched from Oświęcim in the west to Ternopil (now part of western Ukraine) in the east. The main exhibition, “Traces of Memory”, displays Schwartz’s poignant photographs, with text by Jonathan Webber, and records the residue of Jewish life – synagogues and cemeteries, some abandoned and decaying – from across this once ethnically diverse region.

Just across the river – now conveniently linked by the Father Bernatek Footbridge – is the district of Podgórze, where the Kraków ghetto was crammed into a handful of streets. Fragments of the ghetto wall (built in the shape of tombstones) still exist: a small stretch is visible at ul. Lwowska 25–29 and a longer section at ul. Limanowskiego 60/62. The only surviving synagogue from the ghetto area, the Zucher Synagogue, is now an art gallery. Plac Zgody, the main square of the ghetto, is now named Plac Bohaterów Getta (Ghetto Heroes Square), and is where a recent memorial has been erected in the form of rows of metal chairs – a reference to the Nazi practice of throwing furniture into the square as people were deported from their homes.

pl. Bohaterów Getta 18, Kraków, ![]() mhk.pl/branches/eagle-pharmacy

mhk.pl/branches/eagle-pharmacy

This museum is located in the original pharmacy building and was inspired by Tadeusz Pankiewicz’s memoir, The Kraków Ghetto Pharmacy. The interior has been recreated as closely as possible to how it was (based on old photographs) and much of the information is displayed in wooden cabinets and drawers. There are a total of five rooms, each themed slightly differently, covering such topics as Pankiewicz’s own story, the history of Kraków’s Jews, what life was like in the ghetto, and the role the pharmacy played in helping people survive.

Credit: Getty Images

Colourful bottles inside the Pharmacy Under the Eagle

Oskar Schindler’s Emalia Factory

ul. Lipowa 4, Kraków, ![]() mhk.pl/branches/oskar-schindlers-factory

mhk.pl/branches/oskar-schindlers-factory

The Schindler Factory – a ten-minute walk from the Pharmacy Under the Eagle – is now a museum with a permanent exhibition on the life of the city during the war. Called “Kraków During Nazi Occupation 1939–1945”, as with many of Poland’s museums about the occupation, it focuses on the individuals caught up in those nightmarish times, using recorded testimonies as well as documents and artefacts. Schindler and his workers are part of the story, but by no means the main emphasis. The museum is extremely popular and it is essential to book tickets in advance to avoid disappointment. Schindler’s now dilapidated villa is close by at Tadeusza Romanowicza 9, but is not open to the public.

Close to Podgórze and the ghetto, Płaszów is the site of the concentration camp where many Jews worked and where many lost their lives. Most of the camp was razed to the ground after the war, and the area is now a wild and overgrown wedge of land between ul. Kamieńskiego and ul. Wielicka. There are plans for a museum, and there are boards explaining Płaszów history, but the area is not yet geared for tourists and feels rather neglected. For the intrepid, however, there is still much to see, including the villa, known as the Grey House, which was once the offices of the Płaszów SS and Amon Goeth.

A vast granite monument commemorating the “martyrs murdered by the Nazi perpetrators of genocide” looms over the site. The camp was built on a former Jewish cemetery and recently a single gravestone has been restored.

ul. Stanisławy Leszczyńskiej 11, Oświęcim, ![]() auschwitz.org/en

auschwitz.org/en

The entrance to the original camp is through the infamous main gate bearing the message Arbeit Macht Frei (“Work Makes You Free”). The camp itself is made up of a series of barrack buildings divided into blocks, many showing exhibits relating to specific countries, peoples or themes. Several displays show masses of a single object – suitcases, children’s shoes, human hair – bringing home in a particularly graphic way the sheer enormity of the Nazis’ crimes. Block 11 is where the first tests of Zyklon B took place and where the Polish priest Maximilian Kolbe was starved to death, having taken the place of another prisoner. Outside is the wall where thousands of prisoners were shot by the SS.

Birkenau, about 3km northwest of Auschwitz, is more austere and regimented, with a vast area where the grid of prisoner blocks once stood – by 1944 the camp held as many as 100,000 inmates. Just a few of the huts still stand, allowing visitors to see the cramped and dehumanizing conditions. The railway line ran straight down the middle of Birkenau, ending close to the gas chambers. As the Red Army approached, the Nazis tried to destroy all evidence of what had been happening, but what remains bears powerful testimony to the terrible suffering experienced here. Both camps receive thousands of visitors each year and it is worth booking before you make the journey to Oświęcim.

The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II

37–120 Markowa 1487, ![]() muzeumulmow.pl/en

muzeumulmow.pl/en

Opened in 2016 and located in the mountainous Podkarpackie region some 190km east of Kraków, this museum is dedicated to those Poles who risked, and often lost, their lives attempting to protect Jews from Nazi persecution. It’s named after Jósef and Wiktoria Ulma, who cared for eight Jews at their farm before being betrayed by a neighbour in March 1944. The Ulmas, their six children and those they sheltered were all shot. The museum has been criticized by some for having a nationalist agenda, but there is little evidence of this in the sensitive and balanced displays which make it clear that such principled acts of bravery were the exception rather than the rule.

After the liberation of Kraków and Auschwitz, the 1st Ukrainian Front continued its march westward through Lower Silesia, which today is part of Poland, but in 1945 was predominantly German.

The 1st Ukrainian Front’s progress was swift, though they were still faced with sporadic opposition from Army Group “A” (formerly Army Group North Ukraine), now under a new commander, the fanatical General Ferdinand Schoerner. Hitler was being encouraged by his generals to withdraw and redeploy his troops, but he continued to advocate a “stand or die” policy, designating certain cities as Festung – fortresses to be defended at all costs.

Credit: Alamy

Rusting Nazi equipment left behind in a tunnel in Lower Silesia

The Sandomierz–Silesian Offensive was the final push westwards by Marshal Konev’s troops towards Breslau (modern Wrocław) and the Oder river, part of the co-ordinated Vistula–Oder Offensive that was operating along the whole of the Eastern Front. As the 1st Ukrainian Front began besieging Breslau on 13 February 1945, General Chuikov’s Eighth Guards Army was engaged in the month-long Battle of Poznań 170km to the north. Poznań was captured on 23 February, opening up a direct route to Berlin. Breslau would take rather longer to overcome.

Góry Sowie (the Owl Mountains) lie along the Czech-Polish border 80km southwest of Wrocław. Their inaccessibility made this an ideal site for a mysterious, top-secret project ordered by Hitler in 1943 as the war started to turn against him. Using prisoners as slave labour from a Gross-Rosen satellite camp, an estimated 213,000 cubic metres of bomb-proof tunnels and halls were dug out from within the mountains. The project was codenamed Riese, meaning “giant”.

It remains unclear what this underground complex was used for. The retreating Germans and then the Soviets removed all machinery, few documents seem to have survived, and most of the workers involved perished from the terrible working conditions or were killed by the guards. Armaments were almost certainly produced here, but suggestions that a “wonder weapon” was being developed have never been verified. It may also have been used to store some of the art works and cultural treasures looted by the Nazis, and there is a popular rumour of a hidden train containing Nazi gold. Organization Todt, the Nazi engineering group who worked on the tunnels, had its headquarters at nearby Książ Castle, and it’s possible that that castle was intended as the final redoubt of Hitler and his staff.

On the orders of Silesia’s Gauleiter, Karl Franke, Breslau was declared a Festung (“fortress”) to be defended to the utmost by its garrison of 50,000 troops. The street-to-street fighting that ensued was extremely fierce and lasted almost three months, during which most of the city was destroyed. Civilian casualties were huge, possibly as many as 40,000, largely because Franke had been slow to evacuate non-combatants. When he started to do so, after heavy aerial bombardment in January, thousands had to flee on foot in freezing conditions because of a shortage of trains, and many were left behind. Those refugees that headed for Dresden were killed when the city was bombed. Breslau finally capitulated on 6 May 1945, the last major German city to do so. As in Pomerania, Red Army troops then went on a brutal rampage of rape and murder against the remaining German inhabitants. This unofficial policy of “retribution” devastated the surrounding lands, making them virtually uninhabitable.

Borders, deportations and repopulation

As early as 1943, Stalin was insisting to his western allies that the Soviet Union be allowed to retain the Polish territory it had invaded in 1939, an area that the Poles called Kresy, and which now makes up of parts of Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. After prolonged discussions (which largely excluded the Poles), the partition was agreed and ratified by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference in August 1945. To compensate for this huge loss of territory, Poland was to be given Danzig (now called Gdańsk), part of East Prussia and all the land east of the River Oder and its tributary the River Neisse. It still amounted to an overall loss of nearly 74,000 square kilometres.

Credit: Shutterstock

Lomnica Palace

What then followed was the removal, often forcibly, of huge numbers of people from their homes – Poles from Kresy, Germans from Silesia and Western Pomerania. The expulsion of German refugees into an already devastated Germany was carried out precipitously and often brutally by the Polish authorities and caused major problems for Allied administrators. In the east it was no less painful and confusing: Ukrainians, Belorusians and Lithuanians living in Poland were transferred east; Poles in Kresy – about 1.5 million – were “repatriated” west. Breslau (now Wrocław) was largely repopulated with families from Lwów (Ukrainian Lviv), nearly 600km away. For many people this displacement, on top of everything else they had suffered, was profoundly traumatic.

Wrocław and Lower Silesia sites

ul. Grabiszyńska 184, Wrocław, ![]() zajezdnia.org

zajezdnia.org

Occupying an old bus depot (zajezdnia is the Polish for “depot”), this enthralling museum charts the story of the reborn city’s inhabitants in a permanent exhibition, “Wrocław 1945–2016”. The mass movement of entire populations that took place after the war’s end is communicated clearly and sympathetically, albeit from a largely Polish point of view. The multimedia displays focus on the lives of ordinary people, using evocative everyday objects and personal testimonies.

ul. Karpnicka 3, Łomnica, ![]() palac-lomnica.pl/en

palac-lomnica.pl/en

Lomnica (formerly Lomnitz) Palace, near the town of Jelenia Góra 95km southwest of Wrocław, is part of a historic estate dating back to the 14th century. From 1835 it was owned by the German von Küster family, but after their enforced departure in 1945 their home was nationalized and used for various different purposes. Abandoned and slowly falling into ruin, it was bought back by the von Küsters in 1991. The Great Palace and its English-style gardens have now been beautifully restored as a museum and cultural centre, a symbol of reconciliation after the horrors of the postwar deportations. The smaller manor house is now run as a luxury hotel.

Podziemne Miasto Osówka (Riese site)

ul. Swierkowa 29d, Sierpnica, ![]() osowka.pl

osowka.pl

The site, in woodland close to the villages of Sierpnica and Kolce, is the largest of the three Riese tunnel complexes open to the public. Four tours are offered at different prices: the longest is three hours, the shortest one hour. Always book in advance and check when tours in English are available; alternatively, there is an English audioguide. It can get quite cold and slippery, so it’s advisable to wear warm clothing and sturdy shoes. It’s also worth working out how to get here in advance, as it’s rather off the beaten track, with Głuszyca the nearest town.

ul. Szarych Szeregów 9, Rogoźnica, ![]() en.gross-rosen.eu

en.gross-rosen.eu

In the summer of 1940, the Germans built a concentration camp about 65km southwest of Wrocław, near the village of Gross-Rosen (now Rogoźnica). Its location was close to an SS-owned granite quarry where the prisoners were made to work twelve hours a day while on minimal rations. The camp eventually became the largest in Lower Silesia, with around one hundred sub-camps. The one at Brünnlitz (Brněnec in the Czech Republic) belonged to Oskar Schindler, who had his Kraków factory relocated here in 1944, where he managed to keep the 1200 workers alive. The 70th Motorized Infantry Brigade of the Red Army liberated the Gross-Rosen camps in mid-February 1945, but not before the SS had evacuated about 40,000 remaining prisoners to camps in Germany.

Smaller and not so well resourced as other camp museums, Gross-Rosen is still a fascinating but chilling place to visit, rarely as crowded as the better-known camps. Not many of the buildings remain, but their positions are clearly indicated. One building still standing is the SS Canteen, which now houses the camp’s main exhibition, “KL Gross-Rosen 1941–45”, outlining the history of the camp. Labelling is in Polish but there is a booklet in English and the helpful staff will answer any questions. Along the road to the right of the main entrance is the quarry where many prisoners were worked to death.

ul. Lotników Alianckich 6, Żagań, ![]() muzeum.zagan.pl/en

muzeum.zagan.pl/en

A pine forest 4km to the southwest of Żagań (German Sagan) is the site of two prisoner of war camps. Stalag VIIIC, built in 1939, held over 40,000 prisoners, including many Polish soldiers captured at the start of the war. Conditions were excessively squalid, and the regime was brutal. Stalag Luft III, a separate camp built in 1942 for Allied airmen, was far less primitive. This camp became famous for its many escape attempts. The best known involved digging three tunnels, nicknamed “Tom, Dick and Harry”, with the last used for a breakout of 76 men in March 1944. All but three escapees were eventually recaptured, and of these fifty were shot. Paul Brickhill, a former prisoner, later wrote up the story as The Great Escape, which was filmed by Hollywood in 1963. The museum site contains a reconstructed hut, a scale model of Stalag Luft III and several memorials to those who died at the camps. Bear in mind that the actual site of the camp is back towards Żagań. For clear directions, ask at the museum.

Hatred of the Jews was a central strand of Nazi ideology, the Holocaust its genocidal conclusion.

In his 1925 book Mein Kampf, Hitler blamed Jews for all the perceived “evils” besetting not just Germany but the world – from the threat of international Bolshevism to the inequalities caused by unbridled capitalism. Above all, he believed that Jews were sullying the “purity” of the German race. The party propaganda machine, run proficiently by Dr Joseph Goebbels, promoted and reinforced these ideas, which were embraced by many Germans.

Credit: Getty Images

Pedestrians survey the broken windows of a Jewish-owned shop in Berlin after Kristallnacht, November 1938

After 1933, Hitler began introducing punitive legislation against Germany’s 500,000 Jews – less than one percent of the population – restricting access to certain professions. The Nuremberg Laws of September 1935 deprived Jews of their German citizenship and forbade them marrying Germans or having sexual relations with them. Jews were defined not by religion but by race: a person with three Jewish grandparents qualified, those with one or two grandparents were classified as Mischling (“mixed-blood”) and subject to less severe restrictions.

Nazi persecution extended to many other groups. Roma, Slavs and black people were also regarded as untermenschen, or “sub-human”, while those with mental and physical disabilities were designated Lebensunwertes Leben – unworthy of life. Homosexuals were victimized as sexual deviants and Jehovah’s Witnesses for their allegiance to God rather than Hitler. Known communists and trade unionists were also seen as legitimate targets. It’s estimated that more than ten million people were killed overall by the Nazis for failing to conform to, or for opposing, their narrow and perverted world view. Six million of these were Jews.

Random acts of violence against Jews were carried out by Hitler’s thuggish paramilitary bodyguards, the SA (or “brownshirts”), on a regular basis. Such violence reached a climax on 9–10 November 1938 when a wave of anti-Jewish attacks took place across Germany, Austria and the recently annexed Sudetenland. Instigated by Goebbels, this event was known as Kristallnacht, or “Night of Broken Glass”, because of the thousands of shattered windows of destroyed synagogues, shops and homes.

With the invasion of Poland in September 1939, persecution intensified. Stutthof in Pomerania was one of the first Nazi concentration camps built on foreign soil. Initially such camps were used to imprison political opponents (real or imagined) of the Nazi regime, but these increasingly included Jews. Labour camps were also built to exploit the manpower of Jews and other “undesirables” for the benefit of the Reich. From 1941, all Jews in Reich territories had to wear a badge bearing a yellow star of David so that they were easier to identify.

Various “solutions” to what the Nazis thought of as “the Jewish question” or “problem” were aired. A “territorial solution” was briefly considered, which involved the planned deportation of Jews to the East African island and French colony of Madagascar. The plan was only abandoned because the coastal waters around the island were controlled by the British.

As the war progressed, the segregation of Jews from society increased. It was mainly achieved by creating ghettos, enclosed areas of cities or towns where Jews were effectively imprisoned and excluded from the outside world. Before being expelled from their homes, they were stripped of almost all their possessions, including any property. Ghettos were nominally self-governing, but in reality they were under strict Nazi control, with their inhabitants exploited as slave labour. Conditions were appalling: overcrowding and malnourishment increased the likelihood of disease, and mortality rates were extremely high.

Credit: Getty Images

Jewish men being transported from the Warsaw Ghetto to work at other sites

In the minds of some senior Nazis, the inevitable next step was the total eradication of all the Jews of Europe. The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 provided a pretext for putting this genocidal policy into practice. In the wake of the German advance, mobile killing units, called Einsatzgruppen, targeted anyone seen as enemies. This included the entire Jewish and Roma populations – men, women and children were executed, either by gassing in special customized trucks, or by shooting. One of the single biggest massacres took place in Ukraine, at Babi Yar in September 1941 when more than 33,000 Jews from Kiev were shot over the course of a couple of days.

At the same time, a project was conceived to build new camps in Poland (and adapt existing ones) for the purpose of murdering large numbers of Jews as quickly and efficiently as possible. The order came from Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer of the SS and chief architect of the Holocaust. The ghettos would be emptied and their inhabitants transported to labour camps or the new death camps. Gas was the favoured killing method – either carbon monoxide or the cyanide-based pesticide, Zyklon B. Gas chambers, usually disguised as shower units, were installed at the new camps of Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka, and at Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau. The official stamp of approval for the mass killing programme, euphemistically called “the Final Solution”, was given at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin in January 1942.

All camps were built close to railway lines to facilitate transportation from across the Reich. Cattle wagons were used, with people packed in so tightly that many died during the journey. On arrival at a camp, a selection process would occur: those deemed fit to work would be identified, the remainder – small children, the old and the sick – would be made to strip off and taken to the gas chambers. At Auschwitz, some children were selected for gruesome medical experiments carried out by camp doctors. Anything that victims had with them – clothes, luggage, jewellery – was utilized. After a killing session, bodies were disposed of by mass burial or cremation, but only after hair and gold from teeth had been removed.

Credit: Getty Images

The arrival of Hungarian Jews in Auschwitz-Birkenau

Prisoners selected for work at the extermination camps rarely lived more than a few months. Conditions were appalling, food was minimal and of poor quality, and diseases such as typhus, pneumonia, dysentery and tuberculosis were widespread. Prisoners were subjected to petty rules with brutally disproportionate punishments, often applied at the whim of a guard. Work was exhausting and, in combination with all the other privations, could have fatal consequences.

Some prisoners were eligible for “privileges” because of the type of work they did. Kapos were prisoners promoted to the role of a functionary, who supervised the work of fellow inmates. They were often former criminals and could be even crueller than the guards. Sonderkommandos were Jewish prisoners forced to assist in the killing process by clearing bodies from the gas chambers and then burning them. Some women were allocated to the camp brothel. But none of these activities meant that a person was more likely to live; those who did survive relied on a mixture of guile, opportunism, luck and sometimes the help of others. Possessing a valued skill was an advantage – at Auschwitz most of the members of the all-female Jewish orchestra managed to stay alive.

Although what was happening inside the camps was communicated to the outside world, many people found the news too extreme to believe. Polish resistance fighters had infiltrated ghettos and concentration camps, and one of their agents, Jan Karski, travelled to Britain and the USA with detailed accounts of mass extermination. Debate still continues about the Allied reaction. Could bomber aircraft have destroyed parts of the camps or, at least, bombed the railway lines that led to them – as requested by Jewish organizations?

There was resistance from Jews themselves, not just by partisans or in the ghettos, but also in the camps, most notably at Treblinka, Sobibór and Auschwitz-Birkenau. The revolt at Sobibór in October 1943 involved the murder of eleven SS officers before a mass breakout of about three hundred prisoners. Though most were either killed while escaping or on recapture, around 58 prisoners got away, including Alexander Pechersky, the Jewish-Soviet POW who led the uprising. Shortly afterwards, Himmler ordered the camp to be closed down and destroyed.

With the approach of the Red Army, the Germans made a desperate attempt to remove evidence of their crimes. Some surviving prisoners were executed in the last months of the war, while many at the larger camps were evacuated, forced into long arduous “death marches” further behind German lines. In January 1945, in the depth of winter, about 60,000 prisoners made the 53km journey from Auschwitz to Wodzisław on foot, just ten days before Soviet troops liberated the camp. Many died en route, shot by guards for failing to keep up. From Wodzisław the remainder were taken to camps across a disintegrating Germany.

Liberation, when it arrived, could be a traumatic experience for both soldiers and prisoners. When British troops got to Bergen-Belsen in Lower Saxony they found a camp that was vastly overcrowded, having been used as a collection point for thousands of evacuated prisoners from elsewhere. Many of the 60,000 prisoners still alive seemed barely recognizable as human beings, and thousands of skeletal corpses lay piled up around the camp. Over 13,000 more would die in the next few weeks. Feelings of compassion were mixed with shock and, in some cases, fear and disgust.

For the prisoners that lived, the nightmare may have been over, but they still had much to endure. On top of the institutionalized degradation that they had been through – with the prospect of death a constant fear – they had no homes to go to and most had lost loved ones, or even witnessed their deaths. Not surprisingly, a huge psychological barrier existed between the prisoners and their liberators. This was exacerbated by the fact that nearly all surviving Jews remained behind barbed wire for months, sometimes years, in Displaced Persons camps run by the Allies. The task of rebuilding their lives seemed almost insurmountable.

Credit: Getty Images

Young prisoners interned at Dachau cheer the liberating American troops

Credit: Getty Images