During the years 1836 to 1852 there was no Victoria Police Force. It was a period of growth and unco-ordinated experimentation, during which the Port Phillip District, later the Colony of Victoria, was policed by an assortment of autonomous police forces, including the Native, Border, Mounted, and Melbourne and County of Bourke police. It was a confusing situation, compounded because the generic title ‘police’ was applied to all these forces, even though they bore little relationship to each other and exhibited differences in their composition, status, duties and uniforms. Drunks, emancipists and men from the working class predominated in the police ranks, their status and pay were low, and there was a high turnover of personnel. Few people aspired to police work and it was just a transient occupation through which many men passed on their way to other, more desirable or higherpaying employment. It also served as a stopover for miners travelling to or from the goldfields. In an effort to provide a more reliable police service, colonial officials offered career opportunities to young men and tried a range of other options, including a cadet system, the use of military pensioners, and the importation of police from London. No single alternative provided the level of security that was wanted and, faced with the dramatic social and economic changes of the gold era, concerned citizens prompted a consolidation of the disparate police forces. Using Irish and English policing models, an endeavour was made to upgrade the general standard of policemen and the service they provided. The result was the statutory formation of the Victoria Police Force in 1853 as the sole police authority in the colony.

Early in the first permanent white settlement in the Port Phillip District the cry was raised for police and protection, the two not necessarily being synonymous in nineteenth-century Australia. Permanent European settlement was established by the Hentys, at Portland Bay in November 1834, without the assistance of police or soldiers, but those who followed were quick to seek the services of police. John Batman and his fellow expeditioners of the Port Phillip Association settled near the present site of Melbourne in 1835. Batman was a trespasser yet it was only a matter of months before he and his colleagues wrote to Sir George Arthur seeking government protection, which was eventually provided in the form of three policemen.1

This action was significant in that it set the pattern of police development in Port Phillip for many years to come, and also began the often unhappy relations between community and police in nineteenth-century Australia. The provision and level of police service was rarely planned but was normally an ad hoc response to requests such as Batman’s. As ‘protection’ the settlers usually gained inefficient men for whom they showed little or no respect and considerable enmity. Nevertheless, requests for police flowed unabated and, taken with the animosity shown towards the police, there evolved the curious anomaly of the community increasing its police services all the while being unfavourably disposed towards those who performed the task.

Police forces in Australia in the 1830s were abysmal, a source of worry to communities wherever they served. The police in Van Diemen’s Land were no exception and, having come from there, Batman would have been aware of their poor reputation in that colony. Still, he and others after him chose to request police protection rather than undertake co-operative efforts at self-protection and regulation, such as the hue and cry. Settlers, squatters and others engaged in commercial pursuits did not have time to devote to co-operative efforts of self-policing, but were more than willing to pay others to do the work for them. It might well have been the better way, for they were securing for the colony what contemporary English experience was convincingly demonstrating: community security through an organised, preventive police.2

Batman’s initial request for protection was turned down and it was almost a year before colonial officials again considered the policing of the Port Phillip District. Meanwhile reports had come of white settlers shooting Aborigines at Western Port and Portland. These incidents, together with the circumstances of Batman’s occupation, prompted Governor Bourke to send a police magistrate and two Sydney policemen to Port Phillip to investigate and report on the situation. The magistrate was George Stewart, of Campbelltown, and he was accompanied by Sergeant John Sheils and Constable Timothy Callaghan.

Stewart arrived in Port Phillip on 25 May 1836 and found a European population of 142 males and 35 females occupying an area of about one hundred square miles. During his visit the residents held a public meeting and prepared a petition to the governor, one section of which requested the permanent appointment of a police magistrate in the settlement. In his report Stewart wrote of the possibility of forming a ‘Police Establishment’ in the settlement and confirmed the general need for government protection.3 As a result, on 14 September 1836, Captain William Lonsdale, of the 4th (or King’s Own) Regiment, was appointed police magistrate for Port Phillip, and Robert Day, James Dwyer and Joseph William Hooson appointed policemen. Lonsdale was then aged thirty-six and had previous experience as an assistant police magistrate and justice of the peace at Port Macquarie. Like many civil servants who followed in his wake as head of the Port Phillip Police, Lonsdale did not have previous experience in administering a civil police force. He, and a number of his successors, had a military background. Indeed, Lonsdale was issued with two sets of instructions, civil and military. The one made him virtually commandant of the settlement, whereas the civil instructions vested him with the authority to oversee land surveys and customs collections, and to administer law and order—and all persons, including Aborigines, were reminded that they were subject to the laws of England.4

Lonsdale was vested with the dual roles of head of the police and the magistracy, and thereby a precedent was set that endured until well after the Colony of Victoria separated from New South Wales in 1851. The same person directed the police in enforcing the law and making arrests, and sat as judge in those same cases. Such a system was not in keeping with the principles of British justice, yet was not seriously questioned in Victoria until 1852. The primitive state of public administration in the early days of the Port Phillip settlement, tempered by the need for economy, no doubt contributed to this anomaly. That the situation was not earlier and vehemently decried probably suggests that Lonsdale handled his dual roles creditably.

Lonsdale commanded civil police and also soldiers, the latter serving as both a military force and a military aid to the civil power, and this did provoke controversy. There were thirty-three soldiers and their policing of a civil population, though no problem for Lonsdale, soon started a longrunning debate in the colony about civil versus military law enforcement. What fulfilled the immediate needs of the settlement in 1836 proved in the long term to be a poor precedent, greatly at variance with contemporary principles of civil policing in England.5

A most salient point emerged at once in making the Aborigines subject to the laws of England. The Aborigines had not asked for police or government protection, and their view of the police was undoubtedly very different from that held by the likes of Batman, so there has never been a single community perspective on what the police symbolise. When Day, Dwyer and Hooson commenced duty in the settlement they represented many things to many people, not the least of whom were these Aborigines suddenly embroiled in a world of police, laws and courts they did not understand or want. The instructions to place Aborigines under English law thus highlight a fundamental aspect of police–community relations. In an abstract sense the police serve one public with one set of laws, but in reality ‘the community’ is a mosaic of interest groups in which the values and wishes of dominant groups have generally prevailed.

Of the three original policemen, Day was appointed police magistrate for Port Phillip, and the other two his assistants, with the rank of constable. They were typical of that period. It has been claimed that all three were former members of the Sydney Police who were dismissed for drunkenness, but there is nothing about that in the available records. According to the only detailed study of the three men, Day was previously licensee of the ‘Highlander’ public house in Sydney and before that he was colour sergeant in the 57th (West Middlesex) Regiment of Foot. Hooson was a native-born New South Welshman of otherwise unknown background, and Dwyer was an Irishman who had served in the Sydney Police for several years—at one time as assistant chief constable—and he was given special permission to bring his wife, a ticket-of-leave holder, with him from Sydney to Port Phillip. There is no evidence that any of them were ever convicts.6

At any rate ‘law and order’ came to Port Phillip when HMS Rattlesnake anchored in Hobsons Bay on 29 September 1836. In support of the three policemen was a bonded convict, Edward Steel, who was retained as the settlement scourger for a shilling a day. The state of gaol and watch-house accommodation in the settlement made Steel a handy expedient. If offenders were not flogged or fined, the only lock-up was a somewhat insecure slab hut with a thatched roof. During the early months of the colony, law-breakers were sentenced to up to fifty lashes for offences such as ‘interfering with a constable in his duty’, and twenty-five lashes for being drunk or behaving riotously, and Steel was kept fairly busy. Other offenders were confined on a bread-and-water diet, imprisoned in irons, detained or fined.7

Melbourne’s first gaol

Along with explorers, pioneers and surveyors, police were to the fore on the frontiers of European settlement in south-eastern Australia. The arrival of Day and his men may not of itself have amounted to much, but they and Lonsdale were the first of the police who, for many years, pierced the vague frontiers, either before or in the immediate wake of explorers and surveyors. The police were not always popular or efficient, but their services were in demand and their ‘front-line’ role added to the complexity of their being at once both friend and foe to the public.

Lonsdale soon added to the civil establishment by employing William Buckley as special constable and district interpreter. Buckley, the ‘wild white man’, was an escaped convict who had lived with the Aborigines for thirty-two years. More than any other European in the settlement at that time he understood the native culture and language and thus found himself performing the dual roles of interpreter and policeman for £60 a year. The police establishment then included a runaway convict and bonded scourger. It was not really a matter of setting a thief to catch a thief, for the quintet had little to do with pursuing thieves and were primarily occupied with arresting drunks and petty offenders, only occasionally dealing with more serious cases or runaway convicts from Van Diemen’s Land. Indeed, of the first two arrests recorded in the settlement, one was the arrest by District Constable Day of Scourger Edward Steel for ‘irregularity’. Steel, when supposedly on duty, was found in the tent of a female resident. He could not give a lawful explanation for his presence and was fined the sum of ten days’ pay. In this way the agents of law and order in the settlement were hardly likely to win public respect but did add to their own returns of work.8

Although the police dealt primarily with minor matters, this was not due merely to their ineptness or to the state of crime in the settlement. The fledgling criminal justice system administered by Lonsdale did not have the capacity or authority to hear serious criminal cases. Any such offences prosecuted in Port Phillip were committed for trial to the superior courts in Sydney. When this occurred, the defendant and all witnesses were compelled to travel 600 miles by sea to Sydney to attend court. The cost in both time and money was inordinate, resulting in an almost unanimous reluctance on the part of Port Phillip residents to report any crime that might result in a Sydney court case. Consequently, Day and his men were not put to much test as sleuths, and restricted their activities to matters over which Lonsdale had jurisdiction in Port Phillip.9 During their early period of service the police were not sworn as constables, and this was a source of concern to Lonsdale. Finally, in December 1836, the authorities were furnished with the form of oath to be administered:

You shall well and truly serve our Sovereign Lord the King in the office of constable for the Colony of New South Wales so long as you shall hold that office, without fear or favour and to the best of your skill and knowledge. So help you God.10

Much the same oath has been sworn by Victorian policemen and women in the years since. While Lonsdale was finalising arrangements for an oath, his police began to depart the service. Dwyer was suspended on 31 December 1836 for being repeatedly drunk. He had been a constable in the settlement for barely three months, and in the intervening period was the ‘trusty person’ engaged by Lonsdale, and paid additional money, to complete the first official census of the Port Phillip population. Dwyer set a precedent being the first constable to perform extraneous non-police duties in the settlement, work that escalated rapidly after Dwyer’s small venture, and that proved troublesome and controversial well into the twentieth century.

On 11 January 1837, Dwyer was followed from the service by District Constable Day, also suspended for being repeatedly drunk. Hooson lingered in the police service for some months longer than the other two but was finally dismissed in even greater disrepute. In November 1837 he was found guilty of accepting a bribe from a prisoner to release him from gaol before his sentence was up. So all three original Port Phillip constables were dismissed from the force in disgrace and not again employed in that capacity in the settlement.11

The three men, and the reasons for their dismissal, were typical of the police in Port Phillip and Victoria for many years in the nineteenth century. Often drunkards, often former convicts, they were untrained, issued with no set of instructions, unequipped with staves or arms, and not in uniform. They indicate the thin line that divided members of the public from sworn police in those early days. They were drawn directly from a segment of the society they were intended to serve, and remained laymen rather than policemen. A 1980 newspaper item proclaimed:

State’s first police were drunken, corrupt, and so they were. Nor is it surprising. Police services, both in Australia and England, were at an embryonic stage. Peel’s New Police in London had been in existence barely seven years and it was not an occupation to which people of money or ambition aspired. In Port Phillip the constables were provided with military rations and paid labourers’ wages of 2s 3d a day, when clerks got five shillings a day, tide-waiters 5s 4d a day and customs officers eleven shillings a day. Police pay was not the sort of remuneration to attract men of the Port Phillip Association, who were driven by visions of acquiring huge tracts of land and the creation of villages.12

The experience with Day, Dwyer and Hooson did not weaken the Port Phillip settlers’ desire for police protection or Lonsdale’s efforts to provide it. Soon after Dwyer’s dismissal, another former convict, Constable Matthew Tomkin of the Sydney Police, was appointed to the Port Phillip constabulary. Tomkin has a special place in Victorian police history in that he was the first serving policeman to be killed on duty. He was murdered by musket fire in 1837 at the hands of George Comerford, a bushranger. The inglorious beginnings of the force did not lessen the dangers police faced for a labourer’s pay.

The district constable who replaced Day was Henry Batman, brother of John Batman, and he was quickly elevated to a new rank of chief constable and paid a salary of £100 a year, but neither the rank nor the comparatively high pay was sufficient to place Batman above common temptations. Within a year he was suspended from duty for accepting a bribe from one of his subordinates to alter a rostered turn of duty.13

The likes of Day and Batman proliferated in the settlement and there was a long series of appointments, dismissals and resignations within the ranks of the police. Community patience must have been sorely tried, but Lonsdale persisted in his efforts to bring a modicum of efficiency to the police corps. He was a soldier, not a policeman, and policing was novel even in England and Ireland, so it was a difficult task of trial and error. A lack of fixed ideas as to the nature of policing may, in part, have assisted Lonsdale as he proved himself willing to try new approaches. An example was the appointment of Buckley, and it was followed later by the recruitment of two men in Van Diemen’s Land to be constables for Port Phillip: John Allsworth, a former convict holding a conditional pardon, and James Rogers. Stationed at the principal places of disembarkation, Williamstown and Point Henry, Rogers and Allsworth were both well acquainted with the convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, and their principal duty was the detection of runaway convicts arriving in the mainland settlement.14

Reports on the efficacy of this scheme are scant, but Rogers and Allsworth were replaced after resigning within a year of taking office. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of Port Phillip’s early police establishment was the extremely short tenure of office of the men engaged. Whether they left of their own accord—as did Buckley—or whether they were dismissed, few men persisted in employment as police. It was a poorly paid, low-status occupation that, except in rare cases such as those of Rogers and Allsworth, was not seen to require any special knowledge or skills. It did, however, demand honesty, sobriety, able-bodiedness and a willingness to confront danger. The early history of the Port Phillip District shows clearly that few suitable men were willing to become police; even fewer were able to persist in the role.

No exception to this general trend were those Aborigines and Europeans involved in the next scheme implemented by Lonsdale. In 1837 he sought and gained approval to establish a Native Police Corps in the Port Phillip District. The corps was intended to be a mobile force of Aborigines, equipped as police and led by European officers, to minimise confrontations between Aboriginal residents and European settlers, yet provide a ready force for admonishment should depredations occur. In October 1837 Christian L. J. De Villiers was appointed superintendent of the Native Police on a salary of £200 per annum, with rations, and Constable Edward Freestun was appointed as his assistant. The men engaged the services of a number of Aborigines and a camp was established at Narre Warren about 3 miles from Dandenong. The Aboriginal police were provided with European-style clothing and food, but were not paid as police or included with De Villiers and Freestun in the government returns prepared in Melbourne. A series of administrative troubles beset the unit from its inception and, after a number of leadership wrangles, the corps was finally abandoned early in 1839. The corps under De Villiers is not credited with being effective as an arm of the district constabulary, apart from some success in tracking offenders. Yet the actual formation of the corps was innovative. It was an ambitious scheme, never before tried in Australia, established by Lonsdale only twelve months after his arrival in Port Phillip, and set against a background of abysmal failure in the use of European settlers as police. Lonsdale’s concept was developed more successfully when the Native Police Corps was re-established in 1842 by C. J. La Trobe. This enlarged corps, under the command of H. E. P. Dana, achieved considerable success before disbanding in 1852.15

Notwithstanding his relative lack of success in securing a permanent force of efficient police, Lonsdale persisted and a growing number of settlers added their voices to the call for an extended police service. Few people wanted to be police but many people wanted police protection. Lonsdale’s force was not an unchanging group of skilled and trained men but an ever-changing parade of unskilled workers drawn from the lower classes and, in a bid to make them better known and more accountable to the public, Lonsdale took steps to minimise their anonymity. Dressed in civilian garb and unarmed, they were of little utility as a preventive force. In 1838 he equipped the police with staves, for which they paid two shillings each. He also introduced the first Port Phillip police uniform, a ‘plain blue jacket with round metal buttons, red waistcoat and blue or white trousers according to the season’. Lonsdale wanted his men in uniform to let the constables ‘be at once known as such, but also to ensure some respectability in their appearance’. Staves and red waistcoats began the evolution of a uniformed preventive police in Victoria—a visible ‘law and order’ presence. A year later Lonsdale prepared a set of rules for the guidance of constables. While only at an embryonic stage, the establishment of police as a distinct group and vocation within the community was now headed along a clearer path.16

Members of the Native Police Corps formed in 1842

Even so, this development was ad hoc and discordant. Lonsdale, hard pressed to expand his force in Melbourne, was required to satisfy settlers in the Western, Ovens River and Goulburn River districts who petitioned for police protection. So keen were the Western District settlers for protection that their petition contained a pledge to defray the entire cost of maintaining a constabulary force in the area.17 Like the earlier petition from Port Phillip settlers, this request was eventually met and a police office established at Geelong. The initial police strength there comprised District Constable Patrick McKeever, who was paid three shillings a day, and constables Owen Finnegan and Joshua Clark, who were each paid 2s 9d a day. Some time later McKeever was given the extraneous appointment of inspector of slaughterhouses, a move, like that of appointing Constable Dwyer as census collector, that further set the police along the path of extraneous duties. A government inquiry held during the year of McKeever’s appointment as slaughterhouse inspector recommended that police not be given non-police duties, as these impaired their efficiency and were not cost-effective, but this early and far-sighted recommendation went unheeded.18

The Geelong police appointments expanded the constabulary of Port Phillip, not including the Native Police Corps, to twelve men serving a European population of 1265 persons. The Melbourne police by this time were commanded by Chief Constable William Wright, who was appointed to succeed Henry Batman on 5 August 1838. Wright was a most colourful character, known as ‘Tulip’. A former convict, transported to Van Diemen’s Land for poaching, he had served as district constable in Hobart and came highly recommended, being seen by some as a mark of improvement in the standard of the police. He did not wear a uniform but dressed in a manner that has probably not been repeated. A contemporary account describes the appearance of Wright on patrol, and shows why the police chief was known to all as ‘Tulip’:

He was very corpulent, and had a large fat face, keen eyes and aquiline nose. He wore a furry white belltopper hat … Round his neck he wore a large white ‘belcher’ of fine woollen material, ornamented with ‘birdseye’ dottings. His vest, somewhat long, was of red plush; coat, olive-green velveteen, cut away slopingly from the hips, with a tail that reached to the back of his knees; knee breeches, snuff-coloured, with four or five pearl buttons to fasten them; hunting boots, of the best leather, with mahogany or buff-coloured tops. His watch was carried in a fob pocket in his nether garments waistband and the guard was a broad watered silk ribbon, with a key and two massive, old-fashioned, gold seals depending therefrom. In his hand he bore a very stout oaken walking-stick.19

Apart from his resplendent garb, Wright was noted as the first person to hold the office of chief or district constable in Port Phillip and retire unimpeached. He was one of the longest-serving chief constables in pre-separation Victoria and acquired a reputation as an active thief-taker. His eccentric ways did not detract from his efficiency and appear to have been a valuable asset in distracting public attention from the shortcomings of his men.20 Shortly before Wright’s arrival two Aboriginal prisoners had fired the old thatched gaol and escaped. After Wright’s appointment a new gaol and watch-house were erected, ‘in the angle of the market reserve formed by William Street and the lane’. Also during Wright’s term, on 5 November 1838, the Act for Regulating the Police in Towns (the Sydney Police Act), was extended by proclamation from Sydney to Melbourne. This legislation had been requested by Lonsdale to check annoyances such as discharging firearms, using indecent language and working on Sundays. He felt that the rapidly increasing size of Melbourne rendered the police impotent to control such occurrences, unless supported by the Sydney Police Act. With the settlement barely two years old there thus began the perennial clamour by law enforcement officials for increased powers, a clamour that has yet to be sated and that now, as in Lonsdale’s time, is indicative of society’s state of flux and the ever-changing community values and expectations. To Lonsdale’s credit, his suggestion for increased police powers was accompanied by the recommendation that a manual of instructions be prepared for their guidance. In support of this recommendation he attested to the increasing complexity of the duties performed by untrained police, made harder by the frequent changes in personnel.21

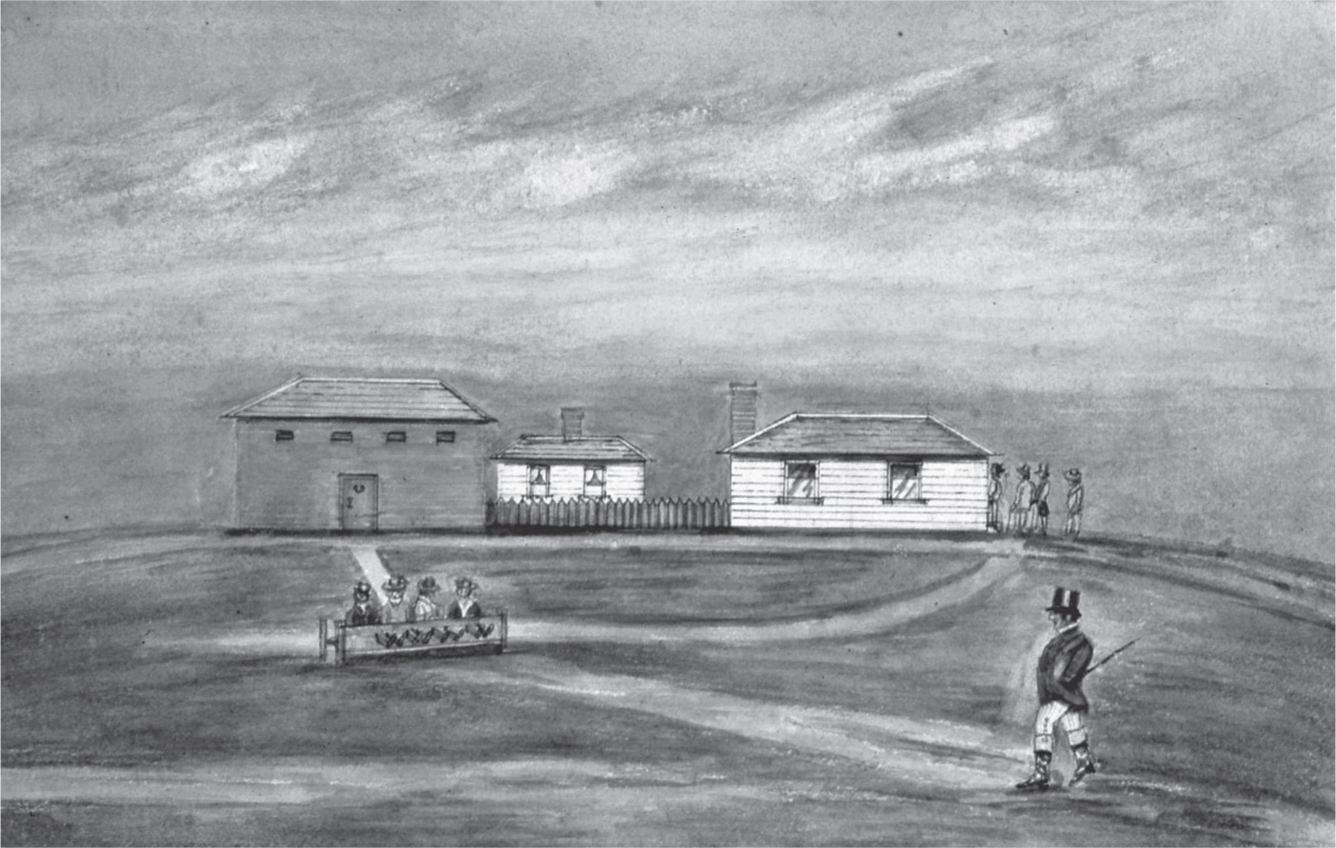

‘Tulip’ Wright in front of the new gaol and watch-house

In 1838 a detachment of mounted police was posted to Port Phillip. Their headquarters were in Sydney, under the command of Major Nunn, and they were in fact soldiers drawn from infantry regiments serving in the colony. Commanded by army officers, they were under military law and drew military pay and rations. Initially, the detachment posted to Melbourne was comprised of a sergeant and six troopers, but within a year mounted police in the District of Port Phillip numbered twenty-nine men, forming the Mounted Police Fifth Division. These troopers were pioneers who established themselves in five parties on the line of route from Port Phillip to the Hume River. Intended to secure the road from Melbourne to Sydney, their camps were located at Geelong, Melbourne, Goulburn River, Broken River and Hume River. At locations such as Broken River the mounted police were the first semblance of permanent European settlement, and they were followed by surveyors and settlers who transformed the police camp and the country around it into towns such as Benalla (Broken River).

The mounted police provide an excellent example of the nature of police development in those early years. In contrast to Lonsdale’s men, they were well equipped, disciplined and trained and, more importantly, they had the increased status and mobility of being horsemen. In many respects they were akin to the noted Irish Constabulary. Although amenable to military command and law, the mounted police administered the civil law and served the benches of civil magistrates. During a twelve-month period the mounted police in the colony of New South Wales (including Port Phillip) apprehended 322 bushrangers and runaway convicts. They also worked as prisoner escorts, served summonses, executed warrants and undertook routine mounted patrols.22 Nevertheless, the existence of such a force was another example of the disorganised and uncertain state of policing. The Melbourne and Geelong, native and mounted police units each operated independently, without a central command or source of funding. They were a curious mixture of Aborigines, free settlers, former convicts and soldiers, and were characteristic of the early decades when civil and military resources were utilised to provide law and order in the settlement. Given Peel’s aversion to any military associations with his New Police in London, that such a motley assortment of military and civil types were labelled collectively as police in Port Phillip shows the fluid state of the colonies and the ad hoc growth of their police services.

The arrival of the mounted police in Port Phillip was not the final phase in efforts to police the settlement. A less successful and less popular phase began in 1839 when Port Phillip was declared the ninth district for the purpose of restraining the unauthorised occupation of Crown lands and to help meet the cost of yet another autonomous police force: the Border Police. Intended ‘to prevent the aggressions, which in the absence of legal control, have invariably been found to occur between the Aboriginal inhabitants and the Settlers’, the Border Police was a corps of mounted police made up entirely of well-conducted prisoners of the Crown. These men worked primarily in remote and outlying areas under the control of the District Commissioner for Crown Lands. The commissioner responsible for Port Phillip was H. F. Gisborne, and his men—like all Border Police—were unpaid, working only for rations and clothing. Such a system was not designed to attract the most capable and honest of men. Reports of Border Police committing outrages against Aborigines were frequent, and squatter Edward Curr described one case where Border Police shot and killed a fleeing Aborigine who was not an offender but a reluctant police guide. In another instance, three Border Police troopers were tried for murdering two Aborigines. Such behaviour was yet another setback for the police reputation in the Port Phillip District, and the Border Police also added to the confusing array of police authorities and uniforms, so they did little to enhance any image of ‘the police’ as a readily identifiable and solid group.23

Back in Melbourne the metropolitan constabulary continued its halting development. In 1841 ‘Tulip’ Wright resigned from the police, and the office of chief constable was occupied in succession by Edward Falkiner, Charles Brodie and William Sugden.24 Falkiner and Brodie were not noteworthy, but Sugden heralded a new era. He took the ambitious step of appointing the first detectives in Port Phillip. Commanding a force of four sergeants and forty constables, Sugden directed five of this number—a sergeant and four constables—to work as detectives. The English, both at home and abroad, had shown a marked aversion towards any aspect of policing that hinted of spying, continental methods or provocateurs. So it was not until 1842 that a few detectives were appointed in England, amid public fears of police espionage. By contrast, the disorganised state of the colonies appears to have facilitated Sugden’s moves to form a detective force in 1844. Social conditions within the settlement were very different from those in England, and the dispersed population and number of former convicts may well have justified, in many eyes, this early venture. The first detective sergeant was James Ashley, and he defended the appointment of detectives by indicating that their work was demanding and dangerous and produced results. Ashley’s ideal type for detectives were ‘honest, sober men, well acquainted with the town and the people who frequent it’. Sugden praised his detectives by highlighting the fact that although they comprised only 10 per cent of his total force, they were far more productive as thief-takers than the balance of his men combined. Statistical records have not survived to prove this claim, but the institution created by Sugden has, lending some credence to claims of greater efficiency.25

For many years detectives worked without the benefit of scientific aids or training; indeed, often without previous experience as preventive police. Their craft was centred around the mysterious and deceitful world of the informer. It was this aspect of detective work that troubled many people and, notwithstanding all the talk of early successes by the detectives, they proved in subsequent years to be a constant source of controversy and intrigue. At a time when it was deemed desirable to discourage former convicts from becoming policemen, it was police policy to enlist emancipists as detectives, ‘because they were better acquainted with the style and character of the arrivals from Van Diemen’s Land’, a contradiction in attitudes that placed emancipists in the position of working among and fraternising with informers and criminals on a daily basis. Events in later years cast serious doubts on the wisdom of this practice.26

Nevertheless, Chief Constable Sugden formed a detective force and so added a note of interest to an otherwise prosaic period in the development of police services in Port Phillip. He resigned from the police in 1848 to become a publican, and was succeeded by Joseph Bloomfield, under whose command the constabulary remained static. Later convicted of assaulting a constable, Bloomfield is best remembered as landlord of the Merrijig Hotel.

For a long-suffering public and an ailing constabulary the year 1850 was a turning point. Bloomfield was reduced in status to assist E. P. S. Sturt, who was appointed to the newly created office of superintendent of the Melbourne and County of Bourke Police. Sturt, a graduate of the Sandhurst Military College, was then a police magistrate who had worked as a grazier and commissioner of Crown lands since migrating to New South Wales in 1837, and his new position was in fact the dual one of police administrator and police magistrate. Like Lonsdale fourteen years earlier, Sturt was placed in the position of having command of the police and also presiding over the summary prosecutions that they placed before the courts. It was a far cry from the separation of judicial and police powers that emerged in later years.

Sturt only took command of the beleaguered Melbourne and County of Bourke Police (one force), and did not have control over the other autonomous police agencies in the colony. Shortly after assuming office, he wrote to La Trobe bemoaning the inefficient state of the constabulary as he found it. The scattered stations, a paucity of men and the lack of any mounted troopers meant that Sturt’s police were travelling up to 150 miles on foot in pursuit of offenders.27 Those problems were mild, however, compared with events looming on the horizon. The population in pre-gold rush Victoria was 77 345 and these were largely emancipists and free settlers pursuing a fairly orderly and slow expansion of the colony. It was not a lawless society and indeed, given the rundown state of the police, this was at once both fortuitous and fortunate. This all changed drastically in 1851. On 1 July Victoria separated from New South Wales and shortly after a declaration was made announcing the first official discovery of gold in Victoria. The rush to be rich was on and the police of the colony were inextricably caught up in it. One policeman later wrote, ‘Crimes of violence abounded everywhere, from the Murray to the sea; the very scum of all these southern lands poured into Victoria’. It was an exaggeration but one that summarised the mood of many of his contemporaries.28

… the weapon for a gold-country is the baton not the bayonet. We shall try to have police protection; we shall NOT have martial law.

Such were the sentiments in the reeling young colony of Victoria trying to maintain equilibrium against the impact of the gold rushes. In the twelve months immediately following the official discovery of gold, the population of Victoria doubled to a figure above 160 000. The percentage of women in the colony was reduced as men flocked in for gold. Thousands of gold-seekers arrived from Victoria’s traditional source of felonry, Van Diemen’s Land. Although many of the new arrivals were steady, decent and hard-working men, many others were footloose adventurers. Egalitarianism prospered in the frontier conditions of the colony and generated ribaldry, revelry and chaos of a kind never before experienced by the colonial constabulary.

Sturt and his men, ill-equipped to cope with benign 1850, were virtually besieged in 1852. More correctly, Sturt was besieged, his men were off to the diggings! On one day in January 1852 a total of fifty-one men resigned from the City and District Police, an exodus that caused Sturt to lament that ‘the rage for the Gold Fields continues unabated’. Of an authorised force of 139, Sturt managed to retain only seventy-eight, and of these he observed that ‘only the clerks in the office appear in no way disaffected’.29

Even so, Sturt was hard pressed to clothe and equip his men. He complained that ‘There are no police stables, no barracks, no swords, no carbines, and though nearly three months since I ordered saddles, etc., only four are now complete, and those not of the best kind’. The uniform of the Melbourne police at this time was described as:

a long-tailed blue-cloth coat, buttoned from the throat down to the waist with metal buttons. Blue cloth trousers were worn, and the bottoms of these were tucked into boots which were known as ‘half-wellingtons’. The hat or helmet was of the usual glazed leather … For night duty, cloth caps with straight peaks of leather were worn. Overcoats of the ‘long torn’, or coachman, pattern were worn at night. With these overcoats a broad black leather belt was worn and upon that belt the constable suspended his baton, lamp and rattle.

In design the police uniform had changed considerably since first introduced by Lonsdale. The militaristic whites and reds had given way to blue as the police colour, and the stave had been replaced by the baton and the wooden rattle, which was used to sound alarms and summon assistance. Although the ideal Melbourne policeman was a well-accoutred rattler, the reality was that things had not changed much since Lonsdale’s time. It was common for ill-equipped police to patrol in plain clothes, with a baton slung from the belt and a band upon the hat bearing the words ‘Melbourne Police’.30

The police commanded by Sturt were still from the lower classes and their status was little elevated above what it had been in convict days. Serle has suggested that the police ranks in 1852 contained ‘perhaps a majority’ of ex-convicts, but such a proposition is purely speculative as quantifiable evidence does not exist to support or rebut it. In 1852 constables were paid 5s 9d a day, which was less than labourers on the roads earned. Indeed, in assessing the relative worth of constables, Sturt in his correspondence to the colonial secretary equated them with day labourers. No minimum educational or physical standards governed entry into the constabulary, no special training was given upon enlistment, and no comprehensive body of regulations or code of ethics existed to govern police conduct. The community was remarkably tolerant of errant police behaviour, perhaps not so much because it condoned misconduct but because people willing to work as police were scarce. In any event, the day labourers in blue serge were drawn directly from the community they were employed to serve.31

Police drunkenness was a perennial problem, partly because habitual drunkards within the force were not dismissed but briefly gaoled. Drunken police were charged publicly in open court and their prior convictions were read to the court before sentence. Initially, convicted police went into the general prison, but later a special lock-up was maintained at the rear of the police station for police prisoners. Upon serving their sentences and drying out, the besotted constables returned to normal police duties. It was a sorry spectacle but one not restricted to Victoria. Drunkenness among nineteenth-century police was commonplace in the Australian colonies and overseas. Although apparently willing to retain drunkards in the police force, community tolerance did not extend to more serious aberrations such as robbery and perjury, which were not altogether uncommon. In one case, two newly recruited constables, on duty, loitered outside a theatre and robbed a pedestrian of his money. In their defence they protested that since joining the police they had not been paid.

If the community was loath to pay its police for some duties, there were other activities that were encouraged and that paid well. One was dog killing. To the ever-expanding range of extraneous responsibilities vested in the police was added the task of killing unwanted dogs about the towns. To encourage constables in the pursuit of this duty, city aldermen offered rewards of up to £3 3s to the constable ‘who shall during the next three months, kill the greatest number of unregistered dogs, and £2 2s to the destroyer of the second greatest number’. With this bounty scheme in operation, a zealous dog-killing constable could earn—in three months—more than one week’s full wages by slaughtering the dogs of the town. One can only speculate as to how the criminals fared while police were occupied in the work of hunting unregistered dogs.32

Incentive payments were a dangerous practice. The underlying philosophy was simple: pay incentives and thereby ensure a greater level of zeal in enforcing the law. It led, however, to police malfeasance of all kinds, and provides an example of how society can shape the behaviour of its paid police. Sturt’s despatches during the gold rush provide clear evidence that insufficient suitable men from the community were willing to join and remain with the constabulary. He also attests to the low status and low pay of the police, and evidence exists of the drunken state of many of the constables and the fact that often they were destitute because of arrears in pay. It is an unsavoury picture, only made worse by the fact that those same police were paid a half-share of the fines for many of the cases they prosecuted, such as obscene language, selling liquor without a licence (sly-grogging), and mining without a licence.33 At a time when police were paid only 6s 9d a day, they could earn four times that amount by securing the conviction of one person for using obscene language. The incentive system really encouraged the suppression of victimless crimes and revenue offences, for which the penalties tended to be fines, rather than more serious offences against persons and property, which were usually punished by much more than a fine. Consequently, there were rarely complainants, civilian witnesses or physical evidence to corroborate police who laid such charges, the evidence being merely the word of a constable who stood to make money if he secured a conviction. In one published case, two constables were sentenced to a term of imprisonment for conspiring together to secure the conviction of a woman on a charge of obscene language, in order to obtain a share of the fine. Sturt spoke ill of the fine-sharing scheme, The Argus criticised it regularly, and La Trobe in correspondence with Sir John Pakington hinted at the monstrous system they had created, observing in relation to illicit liquor sales:

I regret to say that the very inducement held out to the Constable by our recent Act of Council to exert himself in the suppression of this particular offence, necessary and judicious as it might appear to be, would seem to carry with it the disadvantage of inducing the Police to neglect, in the diligent prosecution of this branch of their duty, other functions equally important but less remunerative.

One contemporary but uncorroborated account suggests that some police on the goldfields, pursuing offences for which they received a half-share of the fines, could amass £1000 in just six months. Although that figure would seem exaggerated, there is little doubt that some police did profiteer from the incentive system. Sturt experienced difficulty getting police to work in localities or at duties where the opportunity for shares of fines was limited, and the Mounted Police Corps had trouble retaining men on gold escort duty because they mostly wanted to patrol the goldfields, where they could share in the proceeds from ‘seizures of sly grog shops, and the fines for working [mining] without a licence’. Mounted troopers on the goldfields were known to earn up to £30 a week from their share of fines, at a time when gold itself was bringing only £3 5s an ounce. In addition to the potential for perjury and corruption that the incentive system spawned, it caused jealousy among police and further unsettled the harried constabulary.34

Another scheme used to disburse incentive payments was the Police Reward Fund, established in 1849 by statute as a central account to which a half-share of certain fines could be paid for later distribution to police. Under this scheme there was no direct payment of fines to individual policemen, but lump sums of money were paid from the fund at the discretion of senior officers. During 1851 thirty policemen received payments ranging from £2 to £10 each, but the total amount disbursed for the second half-year was only £125 and fell well below the incentives offered under the other fine-sharing scheme. Because the reward fund was not lucrative it did not receive full police support, but it did serve as a forerunner to police superannuation and workers’ compensation schemes, in that money was paid to constables not only as an incentive but also as compensation for injuries received on duty and excessive hours worked.

Much has been written about the conflicts between police and miners. It is unfortunate that little has been said about conditions of police service and the incentive system that prevailed at the time. Police drawn from the labouring classes, untrained, poorly paid and including many former convicts and drunks, were presented by the authorities with an opportunity to zealously and substantially increase their incomes by collecting half-shares of fines. No better example of a community getting the police it deserves could be found than the incentive system that operated in nineteenth-century Victoria.35

Notwithstanding speculation that half-shares of fines could earn policemen £1000 in six months, colonial officials were hard pressed to recruit and retain men in the constabulary. Sturt complained of the young men who joined his force: ‘They enter the force as a temporary convenience, the inducements of the Goldfields unsettle their minds, they take no interest in learning their duties, are impatient of any control, having the diggings to fall back on’. The vast majority of able-bodied men preferred to try their luck as diggers rather than as bluebottles, and one of the major drawbacks for the police was that ‘really active, energetic characters’ shunned the police service, often leaving only the most indolent and dissolute to join it. Such reluctance served to further depress the standard of the depleted ranks and fuelled the perennial debate over civil versus military law enforcement. The Argus was a vociferous opponent of the use of soldiers to preserve law and order. However, it and others were forced to succumb in the face of increasing lawlessness and a shortage of police. From all quarters of the colony could be heard cries for assistance from a public beset by crime, cries accompanied by talk of lynch law, or the formation of a national guard, a yeomanry corps, a special constabulary, a Committee of Safety or other vigilante groups like the Mutual Protection Association.36 In a desperate bid to bolster the ailing constabulary and as a means of forestalling widespread vigilante action, colonial officials in Melbourne commissioned Samuel Barrow to recruit military pensioners from Van Diemen’s Land. On 19 February 1852 there arrived in Melbourne 130 pensioners ‘to maintain good order and enforce respect to the laws’. These men were mostly aged or invalids and were unsuited to almost any kind of responsible work. Attired in a gaudy, red-striped, military-style uniform, they added further to the inefficiency and denigration of the police force, and to its reputation for insobriety. An Argus editorial described them as being ‘half-horse half-alligator’, while Sturt more precisely called them ‘the most drunken set of men I have ever met with; and totally unfit to be put to any useful purposes of Police’. After a year the military pensioners were returned to Van Diemen’s Land.37

Pensioners on guard at Forest Creek

Colonial officials had also requested that a substantial military force and one or two ships of war be sent to Victoria, and in 1852 there arrived the first large military force in the colony, 560 soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel T. J. Valiant. Reviled throughout the gold districts as ‘lobsters’ and ‘redcoats’, the soldiers were paid only one shilling a day and were generally regarded as being less efficient and more repressive than the regular constabulary. Few men could countenance odious laws administered at the point of a bayonet or the barrel of a gun. The Argus propounded its theme that ‘we want thief-catchers not soldiers’, and made some prophetic predictions about the practice of using soldiers to police civilians. The large body of soldiers served as a bulwark not only against rebellion but also reform. It undoubtedly hindered the development of a proper police force. For some colonial officials the military was a ready, armed and inexpensive alternative to civil police.38

Sturt was not content to see the civil police role usurped by military authorities, and other community groups, including the public press and the Committee of Victorian Colonists, agreed with him. Certain thieves gave a sudden impetus to efforts to improve the thief-catching abilities of the police. During the night of 1 April 1852, a gang of more than twenty armed men pirated the barque Nelson, which was anchored in Hobsons Bay, and stole 8183 ounces of gold stored in the lazarette. It was the most daring robbery committed in the colony up to that point, and yielded the robbers tens of thousands of pounds when £6 was the price of a prestigious suburban building allotment. The scale of this crime alarmed an already reeling community and realised everyone’s worst fears as to the extent of crime. Reports of the robbery filled the Melbourne press, and public apprehension increased during the many weeks before arrests were made. The police acquitted themselves well in apprehending twelve of the robbers and recovering an amount of gold, but this was not enough. The magnitude and daring of such piracy within view of Melbourne had disturbed the public imagination. Support was raised for the Australasian League—a group pledged to work for the abolition of transportation to Van Diemen’s Land—and even the most sceptical of critics felt the need for an efficient, preventive civil police.39

Aided by the Nelson affair, Sturt could be more venturesome, and came up with the novel scheme of recruiting educated young men—not boys—from the upper classes into the constabulary as cadets. His idea was not totally dissimilar to the Irish cadet system, but it was a radical departure from the previous recruiting policies of colonial officials and stands as a landmark in the development of policing as a vocation in Australia. In September 1852 Sturt’s first batch of twelve cadets were selected on the basis of their general standing and education, and were intended to provide the nucleus of a corps from which future officers could be selected. According to John Sadleir, who was one of them, the cadets were made up of men from a wide range of callings, including military officers, lawyers, bankers and students. They were equipped as mounted police and drilled at the police camp on the corner of Punt Road and Wellington Parade. The cadets initially performed mounted duty in teams of seven and patrolled throughout the city and suburbs between seven o’clock in the evening and midnight. As their numbers increased they were gradually spread throughout the colony and worked as both foot and mounted police. The scheme operated for only three years, 1852–54, by which time 244 young men had joined. Many of them served only brief periods, but forty-six were ultimately promoted to officers. The cadet corps was, in fact, quite a popular choice of vocation, and it was this that eventually led to its disbandment. Intended to be a small, select group, the corps was too popular; so many young men were allowed to join that promotion opportunities were curtailed, and many of them became disillusioned. By this time, however, in many respects the scheme had served its purpose and W. H. F. Mitchell wrote:

the Cadet Corps was found beneficial as a Constabulary Force from the higher tone of the young men, and their being above the temptation to accept bribes, to commit breaches of duty. They have been highly advantageous both for duty and as setting an example of discipline and good order to the ordinary police.

They numbered in their ranks such later luminaries as Hussey Malone Chomley and Edmund Walcott Fosbery. Chomley served with the Victoria Police for fifty years, from 1852 to 1902, and rose through every rank to become chief commissioner, the first career policeman to be appointed to that position. Edmund Fosbery became inspector-general of police in New South Wales, and headed that force longer than any other person in its history. As a tribute to Sturt’s recruiting, the two largest police forces in Australasia entered the twentieth century under the command of men who’d begun their careers over four decades earlier as Victorian police cadets.

Nevertheless, Sturt’s cadet scheme had inherent limitations. The promotion wrangles and accompanying disillusionment marred the scheme, and its immediate impact was limited. It was, however, an important phase in the evolution of police services and partly answered the plea of an Argus editorial:

We want thief-catchers, not soldiers … Brains, brains, brains, we repeat, are what we want, and not mere firearms and muscle.40

Leading members of the Victorian community, alarmed at the rise in crime and the sorry state of the police, moved to recruit trained police from the United Kingdom and to establish a government inquiry to suggest ways of improving the local police. Both moves now stand as milestones in the development of police services in Victoria.

The importation of trained police from the United Kingdom was a popular idea during the gold rushes, and was seen as a means of bolstering the depleted local ranks with professional policemen from a respected overseas constabulary. Much misinformation has gathered about the circumstances surrounding the proposal, and the credit for it is often attributed to the wrong quarter. Those most often credited with suggesting the scheme are E. P. S. Sturt, W. H. F. Mitchell and the Snodgrass Committee. Although all three wholeheartedly supported the concept, none can lay claim to its conception. A committee of colonists from Victoria, acting independently, initiated the idea early in 1852. Four men, led by Captain Stanley Carr, approached the secretary of state for the colonies, Sir John Pakington, in London during May 1852, and told him about the condition of the colony and their desire for a better police force. Shortly afterwards, the committee petitioned Pakington in writing to send fifty men from the Irish Constabulary to serve in Melbourne, for three years, at the rate of ten shillings a day. Considerable correspondence passed between the colonists and Whitehall before it was agreed that fifty volunteers from the London Metropolitan Police, instead, would be sent to Melbourne. They were a very different type of policeman from those in the Irish Constabulary. The latter, formed by Robert Peel in l814, was a paramilitary force of mounted and foot police, dressed in rifle-green uniforms, armed with flint-lock carbines and stationed in barracks commanded by inspector-generals. It was a repressive force, used to suppress internal disorders and dissent, the very antithesis of his later creation, the New Police of Metropolitan London, who were unarmed and at great pains to shun militarism. The contrast between the two forces was striking and suggests that someone at Whitehall envisaged the problems that might have ensued from unleashing a body of armed and mounted Irish police among the goldfields population of Victoria, which included a large number of Irish expatriates. The official reason given for not providing Irish police was that no such men could be spared, and no evidence exists to cast doubt on this explanation. However, large numbers of former Irish policemen later came to Victoria as migrants and joined the force, giving it a strong Irish identity.

The ‘London Fifty’, as the English foot police came to be known, were a valuable acquisition and over time significantly altered the style of policing in Victoria. The London men—who actually numbered fifty-four—consisted of three sergeants and fifty constables, led by Inspector Samuel Freeman, a 46-year-old career policeman who had served with the Metropolitan Police for fourteen years. John Sadleir wrote of Freeman’s contribution to policing in Australasia:

Freeman … furnished an object lesson in police methods, and in high ideals of duty unthought of before … The reputation of the service soon spread far and wide, so that the authorities in New South Wales, New Zealand and Queensland were glad to get from Victoria officers and men qualified for the work of building up the police service in the several States.41

Although arrangements to recruit police in the United Kingdom were begun in May 1852, officials in Victoria were not advised of these until after 30 October 1852. The London Fifty did not arrive in Victoria until May 1853.

During the intervening period other colonists, particularly members of the Legislative Council, were taking steps to improve the efficiency of the police. On 7 July 1852 Peter Snodgrass, MLC, successfully moved a motion ‘That a Select Committee of this House be formed, to consist of six Members together with the proposer, to take into consideration and report’ upon the state of the police in Victoria. A committee of seven, chaired by Snodgrass and including the attorney-general, commenced sitting on 9 July 1852. It was the first inquiry touching upon police in the colony since the 1839 New South Wales Report on Police and Gaols, and it produced substantial changes in police organisation. It also created a precedent for the regular public inquiries, judicial and otherwise, that have served ever since as a valuable medium for the community to participate in shaping and directing the development of the force—even though at times they have been painfully searching and vitriolic.

The Snodgrass Committee received evidence in nineteen sittings from sixteen witnesses, including policemen, aldermen, court officials and settlers. The main witness was E. P. S. Sturt, whose basic suggestions and sentiments were supported by the others. The Argus carried daily reports of serious violent crime and police ineptitude. Read in isolation, these accounts appear sensational and exaggerated, but they accorded with those given by witnesses to the Snodgrass Committee. At the time of the hearings no fewer than seven autonomous bodies of police had jurisdiction in Victoria, including the City Police (headed by Sturt), Geelong Police, Gold Fields Police, Water Police, Rural Bench Constabulary, Mounted Police and Gold Escort. These forces were funded and operated separately, without co-operation or even regular communication with each other. Such a system was not unusual. It also operated in New South Wales, Western Australia, Queensland and England, so parochialism and duplication of police functions were the rules of the day. This splintered organisation might have endured in Victoria, as it did in many other localities, but for the gold rushes. Victoria was a distant colony, much larger than England, with a rapidly increasing population that included a disproportionate number of males and a significant proportion of emancipists, who were scattered throughout the colony and who shifted population centres as new fields were opened. Against the background provided by these social conditions, the Snodgrass Committee heard evidence about the high incidence of crime and the insufficiency and inefficiency of police. Evidence was also given about police filling the dual roles of thief-catcher and judge, the evils of the Police Reward Fund and the incentive system of sharing fines, the need for a police superannuation scheme, and the desirability of obtaining police from the United Kingdom.42

One of the most important themes to wend its way through the committee hearings related to police conditions of service—until then they had never been an issue. Wage rates had dominated recruiting efforts, but little regard had been given to work and living conditions, uniform standards, occupational status or benefits such as superannuation. With the Snodgrass hearings much of this changed, when the committee heard of the unattractive and often deplorable conditions under which police lived and worked. Many people outside the police service also worked under sub-standard conditions, but the Snodgrass Committee had the task of devising new initiatives to induce suitable men to join and remain with the constabulary, and there was a general consensus that the immediate need was for a locally recruited and properly constituted civil police—‘redcoats’, ‘alligators’ and United Kingdom imports were interim measures, not long-term panaceas. Consequently, ideas emerged about such things as proper police barracks, a superannuation fund, the issue of adequate rations and clothing (including the suggestion of ‘a showy uniform’), and improved promotional opportunities. The majority of police forces in England and Wales did not have pension schemes and it was not until 1875 that a select committee was established in England to investigate police superannuation, so on issues like that the Snodgrass Committee was acting in advance of its time; but on others it lagged behind. Recruiting and training standards were not investigated but, given the reluctance of men to join the police, it is not surprising that the committee avoided those subjects. Its task was to bolster and maintain the police numbers, which were objectives not readily met if men were to be lost because they failed to meet arbitrary standards.43

The Snodgrass Committee report was tabled in September 1852 and the opening paragraphs criticised the state of policing in Victoria, concluding with the observation that the existing forces were ‘insufficient in numerical strength, deficient in organization and arrangement—and utterly inadequate to meet the present requirements of the country’. The committee recommended the formation of a single force of no fewer than 800 men, the organisation, superintendence and control of which was to be entrusted to one man to be called the Inspector-General of Police. The substance of this recommendation was implemented and the amalgamation of small, autonomous forces into a single unit was a first for Australia, and came before many similar moves in Europe and North America. Victoria preceded its parent colony, New South Wales, by a decade in the consolidation of its police groups. The status of the Victoria Police as a vanguard force in the immediate post-separation era highlights the role of the gold rushes in forcing social change through this period. The low status of the police, and events such as Eureka, have served to cloud achievements in police reform at that time. Development and reforms were at an early stage but, when compared with events in neighbouring colonies and overseas, placed the Victorian constabulary to the fore as a progressive force. Critics of the police can indicate many facts to the contrary, and in some respects they are right. Viewed in isolation the Victoria Police Force of the 1850s does not appear outstanding; instances of corruption, brutality, inefficiency and maladministration abound. Yet, when seen comparatively and in its own times, it appears as a leading force, guided towards increasing efficiency by the likes of Carr, Sturt, Freeman and Snodgrass.

In addition to the recommendation that the colony’s police be organised as a unified force, the Snodgrass Committee suggested changes to wages, rank structures, uniforms and rations, and recommended that policemen be provided with comfortable, free barrack accommodation and a superannuation scheme as ‘an inducement not merely to enter, but to continue in the service’. The committee hoped its work would ‘lead to the speedy formation of a force, sufficient in number and effective in organization and discipline, to carry the laws into execution and afford protection and security to Life and Property’, a somewhat optimistic hope, but not an impossibility.44

Within a matter of weeks a Police Regulation Bill was the subject of legislative debate and public speculation. Modelled on the London Metropolitan Police Act, it avoided the quasi-military Irish model and provided for a civil force, using civil ranks and terminology. This contrasted with some other forces, notably the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which was later founded upon the Irish model and adopted many military procedures and titles. In practice, however, there was some confusion of these models in Victoria, and considerable paramilitary behaviour was evident at times, particularly when the police were used as agents of social repression (or the rule of law?) during goldfields uprisings and outbreaks of bushranging. This was partly because the Irish model served more readily when repression was thought to be necessary, and also because its mounted aspect was better adapted to rural policing away from the towns. The essence of the London model was foot patrols in an urban environment, and although this worked well in Melbourne and the larger towns, it did not work in the wide and sparsely settled Victorian countryside.45

The Police Regulation Act was assented to on 8 January 1853. It repealed earlier New South Wales legislation and provided for a chief commissioner of police to take charge of all police in Victoria and combine them into one force. The title of chief commissioner was unique to the Victoria Police and, although the reasons for adopting it were not publicly stated, it coincided with the titles accorded other civil officials of the period, such as goldfield and Crown land commissioners. In keeping with the tone of the Victorian Act, it was less militaristic than the proposed title of inspector-general, which was used in the Irish Constabulary and later adopted in New South Wales.

The new Police Act established six ranks: inspector, sub-inspector, chief constable, sergeant, cadet and constable. No provision was made for a structured promotional system, whereby men could expect to rise through the ranks according to a pattern based on seniority or experience. Instead, the patronage system operated and it was open to the lieutenant-governor to make all personnel changes and promotions for ranks above constable ‘as he shall think fit’. The chief commissioner was empowered to appoint or dismiss any constable. The lieutenant-governor and the chief commissioner were somewhat restricted in the exercise of their discretion to make appointments by laws that, for the first time in Victoria, specified the qualifications required by men joining the force. However, surviving records show the appointment of men who were beyond the maximum age, and, as men already serving were retained, the nucleus of the Victoria Police Force was comprised of men who in many cases were not what they were supposed to be:

of a sound constitution, able-bodied, and under the age of forty-five years, of a good character for honesty, fidelity, and activity, and unless circumstances shall render it necessary to dispense with this qualification in any case, he shall be required to read and write, and no person shall be appointed to be such Constable, who shall have been convicted of any felony or who shall be a Bailiff, Sheriffs Bailiff, or Parish Clerk, or who shall be a hired servant in the employment of any person whomsoever, or who shall keep a house for the sale of beer, wine or spirituous liquors by retail.

In comparison with present standards such qualifications were low, but they were a substantial advance on the unregulated recruitment of illiterates, alcoholics and transported felons, and were not markedly different from those laid down for Peel’s New Police. The most notable differences were that Peel’s standards specified that applicants were to be under thirty-five years of age, at least 5 ft 7 in in height, and men who ‘had not the rank, habits or station of gentlemen’. An urgent need to recruit police, and the values of a gold society, might have accounted for the disinclination of Victorian officials to turn away 36-year-old ‘gentlemen’, 5 ft 6 in tall, who wanted to join the force.

The 1853 legislation also laid down some police duties and created a number of statutory offences to cover police misconduct, such as accepting a bribe, conniving at the escape of a prisoner, desertion, and assaulting a superior officer. It was made an offence for any member of the public to impersonate a policeman or possess police equipment, and for any person to induce a policeman to forgo his duty or offer him a bribe. These provisions contributed further to the establishment of policing as a distinct occupation within the community, and the penalties attaching to them indicated a relative increase in the level of public expectation and occupational responsibility attaching to the office of constable. The maximum penalty for a member of the public trying to bribe a policeman was a fine of £50. The maximum penalty for any policeman accepting a bribe was set at twelve months imprisonment with hard labour. The rationale, apparently, was not as much to discourage members of the public offering bribes as it was to discourage policemen from accepting them.

The underlying principle of occupational responsibility served to secure for the police some compensatory benefits. A feature of the 1852 Act was that it established a pension fund expressly for police. Known as the Police Superannuation Fund, it was financed by deducting 4 per cent from the salary of each policeman, which was then credited to a central, interest-bearing fund that paid benefits to police who retired on account of age, ill health or injury. Benefits were also payable to widows of policemen. The sums of superannuation provided for were quite liberal, and ranged up to the annual payment to a superannuee of the amount equivalent to the whole of his salary as it was at the time of his retirement, provided he had served in the constabulary for more than twenty-five years and had reached the age of fifty-five. Provisions such as these were innovative and indicative of the generous inducements deemed necessary to recruit and retain suitable men. The scheme was so novel, however, that some recruits objected to the 4 per cent deduction as something not experienced in other lines of work, and those complaints, together with administrative complications, eventually caused it to be abandoned.

The year 1852 was important for police in Victoria. Crime was increasing, immigrant ships arrived almost daily and the search for gold and land dictated the rate and spread of development. The sense of urgency created by these conditions proved conducive to reform. Sturt established his cadet corps, Freeman and his men were despatched from London, and the Snodgrass inquiry provided a valuable forum for debate on the police and brought about the enactment of vanguard legislation to organise a unified police force.46

The reforms of 1852 and the passing of the Police Regulation Act were mere formalities compared with the task that confronted William Mitchell upon his appointment as chief commissioner of the Victoria Police Force. Provisionally appointed to the post on 3 January 1853, the 42-year-old Mitchell was the first person to hold the office. An Englishman, he had lived at Barford station near Kyneton since 1842 and before that had held a number of administrative positions in Van Diemen’s Land, including that of writer in the Office of the Executive Council. Mitchell’s appointment set a precedent that lasted for forty-six years, during which no career policeman was appointed to head the police in Victoria. Instead, the practice was to appoint prominent public figures who had not served in the ranks, which was in many respects justified by a lack of suitable men within the force.

Mitchell did not seek the position and before accepting it insisted that it be offered to Sturt, because he believed Sturt was better qualified. Sturt, however, declined the offer and accepted the lesser post of chief inspector, which he left after a short time to resume his career as a magistrate. Mitchell successfully argued for autonomy from the police magistrates and the colonial secretary, and was allowed direct access to the lieutenant-governor on police matters. In doing so he elevated the administrative status of the police and saved them from subservience to the magistracy.47

In support of Mitchell the government appointed twenty-six officers, many of whom were permitted to operate private businesses outside the force in recognition of their ‘gentleman’ status and as a condition of their entering the service. In addition to Sturt, they comprised one paymaster, one stud master, four inspectors, four acting inspectors and fifteen sub-inspectors. Two of the ‘new’ men, paymaster William Mair and acting inspector William Dana, were experienced police with a good knowledge of the colony. Mair was a colonial identity who as a career soldier had arrived in Australia during 1842 as part of a military detachment escorting convicts to Van Diemen’s Land. He remained in the colonies, serving as adjutant with a mounted police force in New South Wales, and gained prominence when he commanded a detachment of mounted troopers sent to quell sectarian riots in Melbourne. After the riots Mair held a number of positions, including that of police magistrate, before joining the Victoria Police Force. As paymaster Mair was third in command, behind Mitchell and Sturt. Dana arrived in the colony in 1843 and joined the Native Police Corps, serving as third officer under the command of his older brother until the corps was disbanded. He was then employed hiring men and purchasing horses and equipment for the mounted police. Due to his expertise in this field he was a key witness before the Snodgrass Committee and that led to his commission as an officer with the Victoria Police.

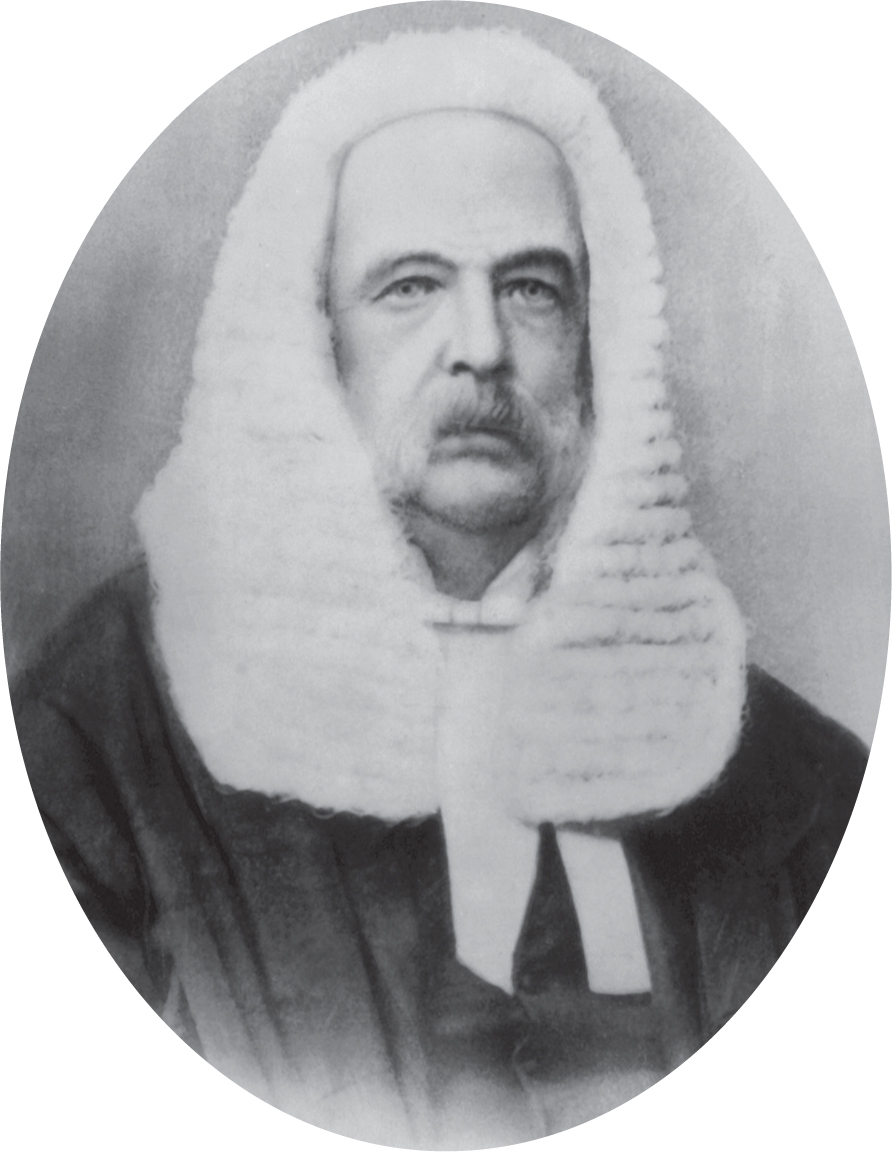

Chief Commissioner W. H. F. Mitchell

Not all Mitchell’s officers had previous colonial experience. New arrivals too had their place in the young force and one of these was Captain Charles MacMahon, late of the Dublin Militia. MacMahon, who eventually succeeded Mitchell as chief commissioner, arrived in Victoria during October 1852 with the intention of establishing his own mining company. He was, however, a former riding-master and veterinary surgeon in the British Army and instead of mining he applied for the sinecure of police stud master. Mitchell thought him better qualified for other work and persuaded him to take the position of inspector of police for Melbourne, which was the most demanding officer position in the colony.48

On 1 January 1853 the force, including the twenty-six officers, numbered 875 men, who were classified by Mitchell as: 26 officers, 106 non-commissioned officers, 471 foot constables, 223 mounted constables and 49 cadets. The population was marginally above 168 000 and, based on these figures, Victoria had an estimated police to population ratio of 1:198—a figure Mitchell described as still being ‘inadequate to the wants of the Colony’. Within six months of taking office he had increased the force by 82 per cent, giving him a total of 1589 men and an estimated police to population ratio of 1:100. This ratio was far better than those of later years and the force in 1853 was larger than it was early in the twentieth century, when it served more than a million people. The high number of men commanded by Mitchell might indicate an effort to use numbers to compensate for police inefficiency. It might indicate that the unusual conditions of the gold rushes—particularly gold escorts and mining licence checks—demanded more police than has since been the case, or it might have been that the police growth was an unplanned, unwarranted deployment of excessive numbers of men. It was Mitchell’s opinion that too many policemen were deployed on guard duty, a task he felt ‘would be far better performed, and at much less expense by soldiers’. Mitchell also had under his command a detachment of fifty soldiers ‘trained at very considerable expense to act as mounted troopers’.49

The strength of the force exceeded the figure authorised in the estimates by 520 and Mitchell advised the lieutenant-governor that even this figure was not enough and that for the year 1854 he would need 2000 men. The lieutenant-governor had agreed to Mitchell’s initial expansion of the force, and when asking for the further increase Mitchell advised him that more men were needed because ‘A large portion of the country is still very inadequately protected, and as new diggings break out, they must at once be provided with ample police while it is impracticable to diminish the numbers now employed at any one station’. Mitchell’s constant recruiting was accompanied by the complaint that he could not properly clothe and equip the force, nor could he provide sufficient barrack accommodation or horses. He never made the complaint of earlier chief constables that he could not recruit enough men and, aided by peak migration levels and a downturn in gold production, adopted a policy of recruiting at all costs. He did not, however, match his recruiting efforts with provisioning for his force. While the well-dressed chief bemoaned a lack of equipment, The Argus described his men: