The opening decades of the twentieth century produced some of the most far-reaching changes to police organisation ever. It was a time of social, economic, technological and industrial upheaval, and was marked and marred by conflict. The key event was World War I, which involved policemen to an extent and in ways that have long gone unnoticed. Just as the war touched the lives of many other Australians, so also it touched the police force and influenced attitudes, ideas, recruiting, duties, workload, and ultimately the direction of policing. The appointment of women police came about partly because of the war, while the advent of the motor car and the formation of a police union were other important innovations. Indeed, the motor car irreversibly altered the nature of police work and police community relations. While these broader events were taking place, the force had four chief commissioners, men whose leadership ranged from exceptional to mediocre. The pressures of war, command changes, unionisation, social conditions and political climate combined to create an environment in which a police strike was possible—and finally came in 1923. Conflict and change were the essence of this age, when policemen fought battles on many fronts, against foes that at times included motorists and motorisation, Germans, politicians and each other.

In 1912 a new mounted police depot was built at the corner of Grant and Dodds streets, South Melbourne. Costing £14 064, the complex was reputed to be the best in the southern hemisphere and included a riding school, horse-breaking yards and stables for seventy-five horses. The men of the force had a long and proud association with horses dating back to the 1830s, but the new stable complex was bigger and better than anything they had known in that time. Mistakenly, it was built in the twilight years of mounted policing, in an age when the automobile was about to take over from the horse. Instead of building stables the police should have been building garages. Motor cars were soon changing streetscapes across Victoria, revolutionising personal transport, and altering the nature of policing and community relations.

The first motor car in Melbourne was built locally in 1897 by the Australasian Horseless Carriage Syndicate and was described as having the appearance of ‘a stylish double-seated dog cart’. It was a time of swift invention and, by 1903, there were sufficient motoring enthusiasts in Victoria to form the Automobile Club of Victoria (ACV). In 1904 these motorists held their first rally and boasted that their ‘chariots race without horses’. In 1905 Dunlop held the first motor-car reliability trial in Australia and, also, the first Victorian motoring fatality occurred when a car collided with a cyclist. New expressions crept into common usage as cyclists and pedestrians spoke of ‘road hogs’ in motor cars, and motorists spoke of ‘police traps’. In only eight years the horseless carriage eclipsed the bicycle as the ideal mechanical hack and sped along the road of public acceptance to challenge the horse.1

Motor cars were generally faster, noisier and often smellier than any horse-drawn vehicle and, at an early stage in their development, displayed a potential in the hands of mere mortals to kill and maim their occupants, pedestrians, cyclists and animals. They also frightened children, horses and others not yet initiated into the new world. It was the motor car’s awesome combination of speed and noise that prompted moves to control its use. The need for controls loomed large in the minds of many people and, in 1905, Sir Samuel Gillott introduced the Motor Car Bill ‘to regulate the use of motor cars’. Gillott’s Bill was modelled on the English Motor Car Act of 1903 and proposed that all motor cars be registered, all drivers licensed, and a maximum speed limit of 20 miles an hour apply to motor cars on public roads throughout the state. Gillott intended that municipal councils would undertake the registration and licensing functions and that council officers would join with police to enforce the speed limits and other regulations. This was the case in England, where county and borough councils had traditionally controlled the use of locomotives, traction engines and motor cars. The ACV argued strongly against the controls proposed by Gillott, and parliamentarians divided for and against the motor car. During debates on the Bill the notion of police checking drivers’ licences was compared to ‘the old digger hunting days at Ballarat that led to Eureka’, and concern was expressed about the possible ‘over-officiousness’ of policemen enforcing speed and licence regulations: ‘Honourable members desired to be assured that the power of restriction in these matters would not be placed wholly in the hands of policemen’. The Gillott Bill did not become law, but it did promote considerable lobbying and debate, thus heightening public awareness about the potential of motor cars.

Opposition to the Motor Car Bill and the proposed police role served as a valuable indicator of things to come. The police in Victoria had always had a part to play in the regulation of horse riders and horse-drawn vehicles and it was a role in which their involvement and authority were rarely ever questioned. Constables kept a watchful eye over cabmen, lorry drivers and bullockies, and under the provisions of the Police Offences Act could prosecute larrikin horsemen and others who rode or drove ‘furiously or negligently’ through any public place. Cabmen, traction engine operators and other paid transport drivers were licensed by municipal authorities, but policemen were not involved there and confined their role to preservation of the public safety. Individuals who rode or drove horses or bicycles for private pleasure or transport did not need a licence, and there were no fixed speed limits. The motor car, however, introduced elements of danger, arbitrariness and class into this scene and from the outset hardened the attitudes of those involved.

A changing streetscape: Elizabeth and Collins streets, Melbourne, in the 1920s

The new standards, embodied in the 1903 English Motor Car Act and proposed in Victoria by Gillott, were not unduly restrictive but they were in some respects arbitrary, and they did impose general legal obligations upon motorists that had never been applied to horsemen. Laws intended to protect all road users might have stood a good chance of early acceptance but for the fact that they struck first and hardest at wealthy and influential people. Although the popularity of motor vehicles was spreading quickly they were an expensive luxury item, costing up to £2000 each when workers’ wages were only several pounds a week. The people who then owned motor cars were not the types usually checked or arrested by the police, and the thought of this occurring because they were motorists was anathema to them. Debates on Gillott’s Bill were punctuated by talk of wealth and class, with proponents of the new laws arguing that ‘the people who drive motor cars are usually well-to-do, and there ought certainly not to be one law for the rich and another for the poor’. Opponents of the Bill objected that ‘no constable should be at liberty to arrest a gentleman straight off the reel’ and that arrest ‘depended, of course, on the position the man occupied’. An indication of the exclusive state of motoring was the time devoted during debates to the question of chauffeurs and their wages, and whether chauffeurs or car owners would be liable for civil action or criminal prosecution under the proposed laws. It was a time when chauffeurs had their own club, and when Tarrants Garage in Melbourne provided a waiting room and a billiard table for chauffeurs waiting at the works while their employers’ cars were being repaired. Had the majority of motorists in 1905 been poor workers, rather than well-to-do gentlemen, there is little doubt that the Motor Car Bill would have had a speedy passage through parliament. However, the spectre of policemen stopping gentlemen and their chauffeurs for licence and registration checks was enough to stall it in its infancy. The prolonged period of estrangement between motorists and policemen had begun even before laws regulating motor traffic were enacted.2

The ACV and other influential motorists managed to defer motor traffic regulations until 1908, when another motor car Bill was brought before parliament, this time by Sir Alexander Peacock, with the introduction ‘that motors are being generally utilised now, not only for pleasure, but also for business … it is essential that there should be some legislation to deal with this new and increasing traffic which takes place throughout the metropolitan area’. In the few years since Gillott’s Bill was shelved, the cost of motor cars had steadily dropped, the number of cars and motorcycles in use had steadily increased and, almost as Peacock spoke, cars were being used in military exercises in Victoria and by the publishers of the Herald to deliver newspapers around Melbourne. The 1908 Motor Car Bill differed markedly from Gillott’s proposals in that it vested responsibility for registration, licensing and enforcement with the police and in its final form did not stipulate a set speed limit, but instead prohibited any person from driving a motor car ‘on a public highway recklessly or negligently or at a speed or in a manner which is dangerous to the public’.

Parliamentary and public discussions on the new Bill were couched in similar terms to those of 1905, but experience had removed some of the obstacles to enactment that had blocked the first Bill. There was still a great deal of debate about wealth, class, police power, speed and danger but all parties appear to have drawn upon the comprehensive finding of a 1906 English royal commission that had studied most aspects of motor-car regulation, including speed limits and police methods. The English experience was that fixed maximum speed limits were not feasible and that their regulation placed the police in open conflict with motorists, diverting valuable police manpower from other duties to traffic work. The English commission recommended that the ‘general speed limit of 20 miles an hour’ be abolished and, principally because of that recommendation, no general speed limit was included in the first Victorian Motor Car Act. When the legislation was being debated, the policing of speed limits was seemingly uppermost in the minds of many people. The practice of timing speeding motorists was described as ‘un-English’ and ‘rather humiliating’—indeed, as something that ‘detracted from the proper and dignified duties of the police’. The manner of enforcing speed limits overseas worried Norman Bayles, MLA for Toorak, motorist and member of the ACV, and he described them in the hope that they would not be adopted in Victoria:

They have a policeman stationed behind a hedge with a signal wire along a measured furlong. The policeman has a stop watch and he signals to a man at the other end of the wire when a car passes, and if a person drives only half-a-mile over the 20-mile limit he is a law breaker.

Some members of the House could see ‘nothing trappy’ in the police behaviour described by Bayles, and complimented the police for their ‘ingenuity in bringing to justice people who infringe the laws’. However, Bayles and the ACV won the day and, in place of a general speed limit, there was substituted the notion of driving to the common danger, whereby motorists could drive as fast as they liked unless it was proved to be dangerous to the public. This provision was analogous to that of ‘furious riding’, which was the principal and traditional legal control over horsemen who endangered public safety.

Although discussion about general speed limits was an important feature of the 1908–9 Motor Car Bill debates, considerable attention was also devoted to general police powers over motorists and the question of socioeconomic class. Concern was expressed about the move to give policemen full control of all registration, licensing and enforcement duties relevant to motor cars, and a number of people urged that municipal councils should undertake some of the work, as in England. Peacock, however, successfully pushed his proposals through parliament, arguing that a centralised system for recording licence and registration details was the most viable and that the police force was the logical government department to do the work. He also stressed that the police, unlike municipal councils, were ‘under the control of Parliament’ and that ‘administration will cost nothing’. The last facile statement was in reality a euphemism meaning that the cost of administration would be absorbed within the police budget. Sixty years later Colonel Sir Eric St Johnston inspected the force and reported that nowhere else in the world were policemen ‘responsible for the registration of motor vehicles. It is clearly not a police function and should be carried out by a different organization’, but in 1908 the force was a cheap expedient. Two members of parliament sought to raise the question of police manpower and suggested that ‘the proper control of the motor car traffic will require a great addition to the police force’, but the subject lapsed without further debate. It was not a topic that Peacock or his government were prepared to take up, particularly as they were going to administer the Motor Car Act at no cost.

Once the legislators had satisfied themselves about the questions of licensing, registration and speed control, the principal subject of contention was class: how would policemen deal with wealthy motorists? This big obstacle of 1905 was more readily overcome in 1908. John Murray, MLA for Warrnambool, and a man with some sympathy for Labor, argued without being contradicted that ‘far and above the luxuries of the rich man, far above the privileges of caste, is the safety of the general public’, and that ‘no duty is more properly the duty of the police than to protect the lives of the public’. Murray’s line might have met the fate of similar arguments propounded in 1905 except that even the wealthy could now see a need for regulation: ‘motor cars have come to stay’ and ‘cars will come within the reach of the man with moderate means’. There was even talk of cars coming ‘within the means of humbler individuals’, and of a time when ‘every poor person’ could drive a car. The motor car was confusing the class barriers. Rich motorists would need as much police protection from poor motorists as pedestrians would need from chauffeur-driven limousines. The Motor Car Act and Regulations came into operation on 1 March 1910, and the Victoria Police Force became the single statewide authority for licensing drivers, registering motor vehicles and enforcing all the provisions of both the Act and regulations.3

The new motor-car laws added to police work and altered relations between policemen and the steadily increasing motoring section of the community. During the first four months of the Act’s operation the force registered 2645 motor vehicles and licensed 3204 drivers. By the end of 1911 these figures had grown to 4844 vehicles and 5935 drivers; within a decade they had raced to 29 354 and 34 236 respectively. The annual renewal and maintenance of records, and the collection of revenue related to that work, in 1912 prompted the formation of a special group, the Motor Police, who operated a central office in Melbourne and were the genesis of the vast Motor Registration Branch. The Motor Police, however, performed only a small amount of the total registration and licensing work, most of which fell to policemen across the state. During the 1920s attempts were made to transfer responsibility for motor vehicle registration and record keeping from the force to the Treasury and Country Roads Board, because it was ‘a fruitful source of revenue’. However, these moves were successfully resisted by police administrators on the grounds that ‘the closest contact between the police and the registration system’ was essential ‘to ensure as effective a control as possible over traffic offences, burglaries, thefts of cars [and] movements of organised criminal gangs’. The full import of the awesome rise in vehicle and driver registrations is best shown in relation to other factors. The first ten years of operation of the Motor Car Act included the duration of World War I, and in the years from 1910 to 1919 the number of policemen per 10 000 population fell from 12.28 to 11.49. The number of horses actually rose in this time from 442 829 to 523 788, but, while the death rate in horse-drawn vehicle, tram, bicycle and railway accidents remained relatively static, together amounting to less than two a week, fatal motor vehicle accidents rose to an average of one a week, and from 1913 warranted specific mention in the Victorian Year Book. Traffic control, of both horses and motor vehicles, was just one facet of police work and a declining number of policemen still had to cope with special wartime duties and increases in general patrol and crime work.4

Motor traffic control also altered the relationship between police and large numbers of citizens. Horsemen and policemen had long experienced cordial relations. Although fruit vendors and drivers of hansom cabs were at times prosecuted, policemen regulating street traffic were expected to have ‘a knowledge of horses’, to ‘display intelligence, steadiness and discretion’ and to ‘assist the public’, by zeal and attention avoiding prosecutions rather than increasing them. This philosophy was epitomised by pointsmen at the intersection of Swanston and Flinders streets, Melbourne, who were directed to facilitate at all times the unimpeded progress of horse-drawn lorries and who were issued with a shovel and a box of sand, to be used if lumbering Clydesdales’ hooves were slipping on the road. The shovelling of sand was a service happily rendered by policemen, and one gladly received by drivers of struggling horse teams. At the other end of the spectrum, policemen also played a vital role in the stopping of bolting and runaway horses. It was dangerous work, requiring a special brand of strength, skill and courage, but was nevertheless a common feature of police life at the turn of the century. Many policemen were commended for such deeds and eleven of them received valour badges for ‘stopping bolting horses at great personal risk’.

The advent of the motor car gradually altered this picture, and the policeman with sand and shovel was replaced by one with a stopwatch and notebook. Soon after the passing of the Motor Car Act, police methods for regulating motor traffic were described as ‘the veriest moonshine’, and Chief Commissioner O’Callaghan was forced to publicly defend the traffic work of his men, claiming that they were ‘not after scalps’. Although the Motor Car Act did not contain a general speed limit, much of the traffic duty done by policemen centred on the detection of motorists driving at a speed that was considered dangerous to the public, which thrust the force and motorists headlong into conflict. The ACV started a legal defence fund to fight police cases, and there were constant suggestions that police methods were defective, their stopwatches inaccurate and their attitude to motorists jaundiced. Police in Victoria adopted the English system of using stopwatches to check the speed of motor cars over a measured distance, but—as with their later use of speedometers, amphometers, breathalysers and digitectors—they were continually accused of making inaccurate readings or using inaccurate chronographs, and policemen found themselves locked into vitriolic legal arguments with motorists and their solicitors. Heated and difficult court cases were not new to policemen but, whereas they had traditionally been contests between policemen and criminals, they were increasingly becoming disputes between policemen and ordinary motorists. The class element still played a part, and the Prahran Court was the venue of the most public and hard-fought cases, when the bench heard charges against wealthy speedsters, booked while travelling along the road to Toorak. The press found that reports of motor accidents and traffic cases were popular with readers, so they became regular features. So frequent were such reports that indexes to The Argus included special entries on motor prosecutions and accidents. It had not happened in the day of the horse.

The estrangement between motorists and policemen, first coming to light in l905, increased in scope and intensity as motor cars became more common. It was a seemingly irreversible trend and one succinctly described by T. A. Critchley when writing of similar events in England:

to a growing number of citizens for whom any dealings with the police would have been exceptional, the policeman of every village and town became a man to be reckoned with … a figure of authority … the town policeman was showing more interest in catching speeding motorists than in his traditional weaknesses for rabbit pie, plump cooks in basement kitchens, and pretty parlourmaids.5

There were other consequences. Thefts of and from motor cars constituted a new and lucrative form of criminal activity and, soon after numbers of motor vehicles appeared on Melbourne streets, advertisements appeared for steering-gear and ignition locks to prevent misuse and loss by theft. Motor vehicles also offered the criminal classes greater mobility, the speed and adaptability of motor vehicles having many advantages over horses, trains and boats—although plans could still be upset. In 1916 William Haines was found shot dead in a hire car at Doncaster, allegedly murdered by Squizzy Taylor in a quarrel after they had rented a Unic open tourer in the city and driven towards Templestowe with the intention of robbing a bank agency.

The same features that attracted criminals to cars also caught the eye of others. Before the outbreak of World War I motor cars were being used in Victoria for commercial and military purposes, and as mail vans and ambulances, but the men who administered the Motor Car Act were slow to utilise motor cars in their own work. In 1904 it was suggested that policemen swap some of their horses for motor cars to ‘lend wings to the feet of the law’, but the proposals were filed without comment. So policemen were motorless in an increasingly motorised society; by bicycle and tram they pursued motor cars. It was a source of derision, and it heightened friction between motorists and policemen, sections of the motoring community regarding non-use of the car as clear evidence of police prejudice against motor vehicles and their drivers. This contrasted sharply with the situation in some overseas police forces, most notably in Paris, where policemen were ‘trained as motor car drivers and specially allocated to supervising motor traffic’. When eventually the Victorian force did use motor vehicles it was at first only for the transport of people and property, and it was some years later (in 1922) that policemen actually used motor vehicles for traffic and patrol work. Yet policemen were among the earlier motoring fatalities: two constables from the police band died in December 1911 at Camperdown, when a Rolls-Royce in which they were passengers lost a wheel and crashed during a band visit to the district. The first fatal accident involving a police patrol vehicle occurred in 1926 when a Lancia car overturned near the Alfred Hospital, killing the wireless operator, Constable Arthur Currie.6

The intensity of the hostility between policemen and motorists abated but never disappeared. Regulation of motor traffic was a new and ongoing duty that increasingly occupied police time and distanced the force from large sections of the community. Many traffic laws were absolute, and people were liable to prosecution and conviction even if they did not know they were doing wrong. Constables had traditionally pursued bushrangers, footpads, vagabonds and others of similar ilk, and few honest people questioned that police role. With the coming of the motor car, constables were also required to pursue the likes of the local magistrate, mayor, bank manager and parson. To the policeman anyone who drove a motor vehicle was a potential lawbreaker, and to the motorist all policemen were potential prosecutors. The rules had changed. Something was lost in police and community relationships when the sand boxes disappeared from busy street corners.

Nationhood and federalism were developments of little direct significance to the Victoria Police Force until World War I, when the police of all states were inextricably caught up in the national war effort. The Great War, like the advent of the motor car, altered the relationships of policemen with large sections of the community and forced policemen to alter their thinking and their methods in order to meet the mixed demands of the domestic policing needs of a state and the pressing federal needs of a nation at war. In a rousing and patriotic oration at the Melbourne Town Hall on 15 August 1914, Chief Commissioner Alfred George Sainsbury plunged the force into the war effort by declaring that ‘we were fighting with the gloves off a deadly and determined enemy, fighting to the death … we were fighting—not for the sake of Jingoism or even patriotism but for our national existence’. The loss of the war, he went on, would mean ‘the establishment of a German Police Force, and in fact the Germanising and controlling of all city and country institutions by the enemy’. Sainsbury advocated the formation of ‘a regiment of one thousand well-disciplined and drilled men, comprising police and police pensioners’; and boasted that ‘if the police had to face the foe they would show that they were as courageous and game as any’. Although Sainsbury offered his services as commander of such a unit, and suggested that ‘the Commonwealth arm us and the State pay us’, it was not a practical proposition: he was in effect pledging more than half of his men to the expeditionary force. The idea was not accepted, but the government did allow policemen to volunteer, and the first to enlist did so within days of the outbreak of a war in which 138 members of the force enrolled for active service, twenty-seven of them either being killed in action or dying of wounds. Military promotion was earned by seventy-nine members, and decorations conferred on some of them included the Distinguished Service Order, Distinguished Conduct Medal, Military Medal and Croix de Guerre.7

The number of policemen who went to war fell well short of Sainsbury’s envisaged regiment, and when the fervour of his oration began to die so too did the level of support given to those men who enlisted—a failure of action to match ardent rhetoric that was not confined to the police. Nevertheless, policemen contemplating enlistment were beset by a confusion of bureaucratic haggling over wages, life insurance premiums, reinstatement rights and other entitlements. Many people, including policemen, were unprepared for the onset of war and in the absence of contingency planning the precedent for decision-making was often the Boer War. So the first policemen to enlist were discharged from the force by compulsory resignation, paid in full, instructed to hand in their kits, requested to pay increased life-insurance premiums in advance and docked as much as 5s 2d a day in wages. Representations were made to the government on behalf of policemen wanting to enlist and, as the war progressed, conditions of enlistment were made clearer and more attractive. In 1915 it was decided that the positions of all policemen who went to war ‘would remain open for them on their return to Victoria’. If, under ordinary circumstances, they would have been granted increased pay during their time in the army, that was granted to them on their return to police duty: they were ‘simply regarded as being on leave’. The government also agreed to maintain the compulsory police life-assurance policies for those who went to war, but this was not matched by insurance companies, who demanded higher premiums paid in advance because policemen were engaged in active service abroad, not just for the defence of Australia. The government refused, when asked, to follow the lead of ‘private firms and banks’ in making up the difference between the 7s 6d a day paid to constables and the five shillings a day they earned as privates in the expeditionary forces. Patriotism had its price: at least one constable returned from service overseas to be refused reinstatement in the force because his pre-war police record was not good. But sometimes patriotism was rewarded: 178 civilians who went to war, and returned home fit and well, were given preferential recruitment into the police force for serving King and Country.

In Sunday at Kooyong Road Brian Lewis suggests that for young boys like him in 1914–18 ‘The police are enemies for they are Irish and the Irish are opposed to the war … The Irish police show a reluctance to change the dark-blue uniform of the State for the khaki of the Commonwealth; the police become more and more Irish as the war goes on’. He is both right and wrong. Only one Irish member of the police force is known to have enlisted in the army during World War I, but of 250 men who joined the police force during that period only six were Irishmen, the only perceptible increase in the Irishness of the force being in the minds of those harbouring prejudices.

For many policemen the most important battle was fought on the home front where a depleted force served both a state and a federal master, with a variety of added wartime responsibilities. The routine work of policemen escaped the notice of many people, including the war historian Ernest Scott who, apart from one favourable passage of seven lines, spares the police only several curt mentions in his 922-page tome, Australia During the War. The essential nature of much police work was not overlooked by everybody, however, and Major General Sir John Gellibrand drew on his military experiences when he wrote, ‘It cannot be too strongly urged that police are in a sense a force on active service in a continuous campaign …’8

The man who headed the force during its ‘continuous campaign’ from 1913 to 1919 was Alfred George Sainsbury, who succeeded Thomas O’Callaghan as chief commissioner on 1 April 1913. O’Callaghan’s retirement, like much of his police career, was topical and public—being debated in parliament and featured in the daily newspapers, The Argus in particular urging his resignation and applauding its acceptance. According to that paper, the force under O’Callaghan was ‘utterly demoralised’, ‘suffering from a kind of moral dry-rot’ and lacking ‘morale and tone’. It is true that police pay and work conditions had deteriorated, fostering discontent throughout the force. This was due more to a lack of government funding than to O’Callaghan’s administration, yet his rigid discipline and brusque manner made him a focal point for disaffection. The moves towards police unionisation that he sparked and extinguished in 1903 were again ignited in 1913. At the age of sixty-seven and after a decade at the top, his administration was stultified, lacking innovation and a sense of direction. He did leave the force in a rundown state and the men in it disenchanted, and he continued his enigmatic ways during retirement: he visited police departments in Europe and North America and, on his return, encroached on Sainsbury’s administration by submitting a report to the government suggesting police reforms of a sort that he should have implemented himself while chief commissioner. He then went on to sit regularly as a justice of the peace at the Melbourne Court of Petty Sessions and became a prominent local historian, serving as president of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria and publishing several articles about early Victorian history. In 1923 he made a searing public statement denouncing the police strikers in Victoria, whose refusal to work was largely rooted in decisions taken under him.9

Sainsbury was a moderate achiever, although generally overlooked by historians. In each of three works touching on Victorian police history, Sainsbury rates a scant paragraph and is generally squashed between O’Callaghan and his successor with comments like ‘Sainsbury’s administration, possibly due to the war, was not particularly distinguished’. On the contrary, because of the war and the social and industrial turmoil of those years, his term of office ranks among the most testing of the pre-1939 era.

Sainsbury was a native of Heidelberg, Victoria, and after working as a farrier he joined the force as a mounted constable on 17 May 1878 at the age of twenty-four. He worked his way through the ranks, serving in different parts of the state as a detective and in uniform, and along the way he amassed twenty-six commendations, including a famous one for ‘elucidating a north-eastern mystery, in which a baby was murdered and the body was thrown to the pigs to eat’. Unlike O’Callaghan’s record, Sainsbury’s was exemplary; he was never charged with misconduct, nor made the subject of an inquiry. When appointed chief commissioner, he held the rank of inspecting-superintendent and, at fifty-seven, was the oldest man in the force. An unassuming type, he always wore ‘a battered hat’ and ‘spurned the use of cars’, preferring to ride to work in trams. He was the first chief commissioner to have been born in Victoria and, following Chomley and O’Callaghan, the third successive career policeman to be appointed to the senior post. Sainsbury was selected for the position from an initial list of seventeen applicants that included policemen, soldiers and lawyers, but only three serving members of the force.

The decision to appoint Sainsbury ‘was received with marked approbation by practically every member of the force, as it was recognised that the order of seniority was being maintained’. Indeed, not only did most of the force approve of Sainsbury’s promotion, they held meetings prior to his appointment and publicly lobbied on his behalf. In unprecedented fashion, policemen of all ranks were party to the passing of resolutions that ‘the position of Chief Commissioner of Police, in the event of such office becoming vacant, should be filled by the appointment from within the force of the officer next in rank and seniority’.

Chief Commissioner A. G. Sainsbury

It was indicative of the times and the moves towards employee combinations that policemen organised to press home a demand such as this. It was also indicative of the conservative nature of the force, in that rank was their guide, and seniority their yardstick, in seeking to maintain the status quo through all levels of the force. The Argus had strongly urged the appointment of an eminent young administrator from outside the force, but that was not to be. Adherence to the seniority system was good for morale, enhancing promotion prospects and fuelling ambition. However, it did not necessarily secure the best available person to head the force, and a preoccupation with seniority meant that good luck rather than good management made Sainsbury the force’s wartime leader. Luck, however, this time produced an acceptably solid commissioner.10

Against a background of world conflict, Sainsbury experimented with motorcycle patrols, training classes in lifesaving, first aid and ju-jitsu, purchased a motorised prison van, phased out many troop horses and replaced them with bicycles, and supported the introduction of Sunday rest days for police. It was also during his command, but not due to it, that the Victoria Police Association was formed and two women were allowed to join the force. He was also the first chief commissioner to make statements about the inadequacy of some criminal laws and to suggest legal reforms. He criticised the role of juries in criminal trials and commented ‘that what was an excellent thing in the time of King Alfred the Great, possesses no virtue at all at the present time’. Sainsbury, like his immediate two predecessors, was a conservative leader but, unlike Chomley, was not reactionary and, unlike O’Callaghan, was not fractious. He was a cautious man who often, as with the introduction of women into police work, adopted a ‘wait and see’ attitude and watched closely the course of such experiments when they were tried interstate and overseas. He was not destined to be in the vanguard of police reform but neither was his always a rearguard action. Most of Sainsbury’s reforms reflected broader changes in technology and social values within the Australian community, such as motorisation and the suffragette movement, which is true of almost all police reform.

Still, senior police administrators in Victoria had a record of resistance to change, and Sainsbury was in a position to encourage or reject new ideas. It is to his credit that he ventured to accept the changes that he did. His principal errors lay in his rejection of two new policing ideas that later gained almost universal acceptance throughout the police world. He refused to use police dogs because he felt ‘man could beat the dog every time … I do not think their services as a whole would be worth the time, trouble and money’; and he decided not to introduce electric patrol boxes because they ‘might mean undue interference with promotion, for if constables mechanically record their own movements it would be hardly worthwhile keeping Senior Constables to watch them too’.

Mostly, though, Sainsbury recognised the changed needs of the community and the necessity for the force to offer new skills and services. Under his leadership there began a gradual shift in the emphasis of police work. Instead of focusing almost exclusively on brawny beat constables and distant mounted troopers, the operations of the force were adapted and extended, so that police—men and women—applied new skills to traditional roles and became more active in community welfare work. Less emphasis was placed on the physical size and equestrian ability of recruits, and more attention was given to preparing police to deal with twentieth-century problems. After thirty-five years’ experience, and at fifty-seven years of age, Sainsbury coped well with the stresses of war and proved a loyal servant to both the state and Commonwealth governments, for the horizons and loyalties of the force were extended beyond the traditional geographic boundaries of the state and, in some respects, police work on the home front did become a fight for national existence.11

Before the outbreak of war, work undertaken by policemen in Victoria on behalf of the Commonwealth government was limited and passive, deriving principally from the presence of federal parliament in Melbourne. There was no Commonwealth police force, so state policemen provided security at the Federal Treasury, federal Parliament House and other Commonwealth offices. War quickly transformed this picture and, in addition to those Victorian policemen who went overseas on active service, most members of the force at some time found themselves engaged on Commonwealth duties. Ernest Scott described the wartime role of policemen as one in which they worked as ‘useful police allies’ to military authorities. Such a description understates the nature and extent of the role of state police who, rather than being merely ‘useful allies’, were the key front-line element in Commonwealth efforts to safeguard Australia from the ‘enemy within’. It was the scattered presence of ordinary policemen that made the nation’s internal defences operative. The threat from within was often more imagined than real, but counter-espionage work, intelligence work, translating, surveillance, alien registration and internments were some of the duties undertaken by police on behalf of the Commonwealth. In an air of wondrous expectation, police in the remotest corners of the state were alerted to ‘watch for aerials of enemy agents transmitting messages’, and to watch for and report by telegraph the flights of any aircraft. These duties were different, and were seen as important enough to be tinged with excitement; certainly they were national duties done for the people of Australia.12

The main Commonwealth duty that fell to the lot of policemen was the registration of aliens under the War Precautions Act 1914. Police were appointed registration officers, and a proclamation by the governor-general ordered ‘all persons who are subjects of the German Empire and who are resident in the Commonwealth’ to report themselves to their nearest police station, and to notify immediately any change of address. Several days later, Austrian subjects were included. Duties in connection with the registration of aliens meant ‘a large amount of work’ that was ‘greatly increased by the aliens constantly changing their addresses’. By 1917 the number of registered aliens in Victoria was twelve thousand.

Policemen were also required to ‘arrest and detain all German Officers or Reservists as prisoners-of-war’, and to effect the internment of enemy subjects. A total of 6890 people were interned in Australia, and in Victoria 889 were allowed on parole under police supervision. These duties drew a mixed reaction to and from policemen, who were often required to investigate or arrest local residents of long standing. It was sensitive work that could easily cause offence and policemen sometimes erred or over-reacted, letting suspicion supplant fact. Generally, however, they trod warily and Scott suggests that:

The cool, good sense of an experienced police sergeant with a knowledge of the people living in his district, saved many a person of German origin from interference, or even from removal to a concentration camp, when reports tinged with hysteria or malice might otherwise have brought discomfort upon him.13

Some policemen worked in sensitive areas on secret work. Constable F. W. Sickerdick and a number of detectives were transferred to the Military Intelligence Section for duties that included translating documents and undercover investigation. Sickerdick proved so adept at this type of work that the Defence Department asked for his retention at an increased rank and higher wages. Another policeman whose services the Commonwealth sought to retain after the war was Detective R. P. Brennan, who was sent to Egypt and London on ‘special duty’. The Egyptian authorities had requested the services of Australian police, and after consultations between the acting prime minister, G. F. Pearce, and the premier of Victoria, Brennan sailed aboard the RMS Malwa on 21 March 1916. He remained in Egypt until July 1916, when he transferred to England, and he did not return to Victoria until 1920. Brennan was selected for work overseas because he had a ‘full knowledge of Victorian criminals’, and most of his time abroad was spent tracing Australians who were wanted for criminal offences committed in Australia or while serving abroad with the AIF. For this duty he was specially mentioned in despatches.

Defence work undertaken by policemen was shrouded in varying degrees of secrecy, but undoubtedly the most clandestine was the part played by policemen in founding the Australian secret service. First formed in 1916, and called the Counter Espionage Bureau (CEB), the secret unit was directed by Major George Steward and staffed by one agent and a detective from Victoria. Steward was then private secretary to the governor-general and the CEB office was reputedly located in Government House, Melbourne. The secret service was established ‘at the request of the Imperial Government’ and was ‘worked in co-operation of [sic] the British Counter Espionage Bureau’ as ‘an important link in the Imperial scheme for countering enemy activities within the Empire’. Sainsbury was made a member of the bureau, and direct communication was established between him and Steward, but not even the superintendent in charge of detectives was told of the bureau’s existence or of the fact that one of his men was a CEB operative. In a secret despatch, W. M. Hughes acknowledged that the success of the bureau ‘must always depend in a very large measure upon the co-operation of the State Commissioners of Police’, and to this end Steward organised a wartime conference of all Australian police commissioners in Melbourne, where an ‘efficient system of interchange of information’ was developed for such matters as:

the control of traffic through the sea-ports of Australia; investigation of cases of espionage; the circulation of warrants and descriptions of suspects; the countering of the activity on the part of hostile Secret Service agents and the tracing and recording of the personal histories of alien enemy agents and suspects.

The CEB was the ‘central point’ for Australian counter-espionage activity, but ordinary policemen were its principal source of intelligence data and served as its eyes and ears in the community. In The Origins of Political Surveillance in Australia, Frank Cain comments, ‘The police forces were essential to the carrying out of surveillance … The police possessed the skilled investigators, they knew how to maintain comprehensive record systems, they had skills in conducting prosecutions and getting convictions … They were important cogs in the machine of the political observation of Australian radicalism’. The integral involvement of policemen with the CEB heightened the national consciousness of disparate state police forces and brought them together on a united front that transcended state boundaries. It also set a precedent that served as the forerunner to the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and state police special branches, taking police clearly into the realm of secret agents, clandestine operations and political surveillance. Early targets of the CEB were politically disaffected individuals and groups such as ‘the Revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World’, and Irish Republican Brotherhood sympathisers.14

The hunt for enemy agents was a secret, exciting but small part of the total police war effort. Policemen performed a wide variety of other federal duties like the investigation and arrest of military deserters (which earned them a bounty of £1 a head for each capture), passport and naturalisation inquiries, amusement and betting tax investigations, questions relating to maternity allowances and soldiers’ allotments to dependants, checking federal electoral rolls, manning federal polling booths, providing money escorts and guarding the prime minister. These extra duties combined with the absence of men overseas to make the force short of manpower, and this difficulty was aggravated by a lack of recruits. Sainsbury was under considerable pressure not to appoint ‘men who will not enlist in the Expeditionary Forces’, and eventually he made a public announcement that such men would ‘have greater chance of getting struck by lightning than of getting into the police force’. It was good stuff to please the State Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, but not even Sainsbury’s patriotic rhetoric could placate the true zealots, who criticised the police retiring age of sixty and argued that it would be better ‘if the policeman could be left at his usual necessary occupation, and that the recruit who seeks his position should go straight into the Expeditionary Force’.

They were difficult times for Sainsbury, who was clearly committed to the war effort while still bound to hold his police force together and maintain peace at home. He closed quiet police stations and transferred men to areas of great need, and actively sought to fill vacancies by recruiting returned soldiers. Yet circumstances were against him. As his shortfall of men moved into the hundreds, those policemen still on duty worked extended hours, and as late as 1920 were owed 1600 days in leave and rest days accrued during the war and armistice periods. Men were refused leave to assist with the harvest on family farms, and police pensioners were employed as guards to release policemen (and soldiers) for other work. At war’s end an influenza epidemic in Melbourne further taxed the force’s resources so that the city ‘was being guarded by a body of men less than one-half of the minimum recognised strength’. In government papers marked ‘strictly secret’, ‘secret’ and ‘urgent’, the under-recruiting and undermanning of the force was described as ‘very grave’, and secret steps were taken to bolster the strength of the force so as not ‘to create any alarm’ and to prevent ‘a very serious outbreak’ of crime. Policemen were indeed fighting a battle.15

The involvement of state police in the national war effort exposed policemen to a kind and degree of federalism that they had never before experienced. Most of their wartime duties were not lasting but, even when W. M. Hughes formed his own token Commonwealth Police Force, the new-found police nationalism did not dissipate. A great deal of what policemen actually thought and did during the war was clouded in secrecy, and somebody’s subsequent culling of the wartime files has added to the density of that cloud. Cryptic index entries tell us that a census was conducted of policemen of enemy birth, but that file is missing, along with many others relevant to the police force at war. Because of the absence of so much important archival material, any account of police activities during the war is impressionistic and sketchy. Nevertheless, sufficient traces have survived to show something of the force during war, certainly enough to show that the 10 per cent of policemen who went to war were a very small part of the police war effort. Duty on the home front did not carry with it the mortality rate of duty abroad, but neither was it a haven for the fearful or indolent. Sainsbury himself shouldered enormous responsibilities, and in the shadow of war few people could have realised the many fronts on which his battles loomed. While the sights of many people were fixed on events in Europe, Sainsbury was fighting at close quarters with elements at home who wanted to unionise the police. It was a legacy inherited from the days of O’Callaghan on the eve of war. Compared with world conflict it was a minor domestic crisis, but to Sainsbury and his force it was a turning point of perhaps greater lasting significance than world war itself.16

… a policeman is not supposed to desire beauty. At all events, he does not get it … Still, he is thankful for small mercies—he obtains free some 20 1b of straw with which he may stuff his mattress. He feels that the Government has not entirely forgotten him when he hears that straw crackle under him at night.

The daily regimen for many hundreds of policemen was a spartan one and, in real terms, their work conditions deteriorated as the first years of the twentieth century advanced. Sainsbury inherited a sub-standard, under-manned and demoralised force that was suffering from years of inadequate government support. Most of the responsibility for this lay with a succession of conservative governments, but Sainsbury’s predecessor was also culpable, in that he was quick to crush signs of agitation in the ranks and slow to seek increased pay and improved working conditions on behalf of his men. O’Callaghan was a loyal servant of the governments that appointed and kept him in office. He labelled press accounts of the standard of the force and its work as ‘newspaper tripe’, and vigorously sought to identify and obtain the resignations of any policemen who publicly complained about their lot. A decade of his style of management left the force the poorest of any in mainland Australia, with the result that immediately preceding and during World War I, Sainsbury was engaged in a constant effort to hold the force together in the face of sub-standard working conditions, employee dissatisfaction and, eventually, police unionisation.17

In 1913, when Sainsbury took command, policemen in Victoria still worked a seven-day week and each day shift was divided into two four-hour reliefs spread over twelve hours. Men who went on duty at 5 a.m. did not go off duty until 5 p.m. There were no rest days or public holidays, and the annual leave of seventeen days could not be taken at Christmas or Easter. Ordinary workers subject to Wages Board determinations were paid double for Sunday work, time-and-a-half for overtime and holiday work, and an allowance for working certain night shifts. None of this was paid to policemen: the starting pay of constables was 7s 6d a day, plus sixpence a day for rent or quarters, and after twenty years’ service constables were paid a total of ten shillings a day. Promotion to the ranks of senior constable and sergeant took twenty-four and twenty-nine years respectively. With little short-term prospect of promotion or incremental pay rise, junior constables were paid less than tram conductors and a sum equivalent to the minimum wage paid to labourers. However, as well as facing the usual living expenses of a labourer, policemen had to buy and maintain a uniform worth about £12 and pay five-pence a day in compulsory police insurance. On top of all, policemen were expected to ‘live in a house better than the house which an ordinary labourer occupies’ and ‘to keep his family respectably’. The paradox of paying policemen as one class and expecting them to live as another was recognised by some members of parliament, who urged that policemen be paid a ‘living wage’. A. A. Farthing, MLA, whose electorate of East Melbourne included the Russell Street barracks, warned of the dangers of ‘placing these men in the greatest temptation’ and pleaded that ‘they should be paid sufficiently well to enable them to act honestly, and live and bring up their families respectably, educating their children as we expect reputable citizens of Victoria to do’.

Although many people could see the point, the problem was compounded by the fact that constables were still drawn from the working classes. Within the public service the force was regarded as ‘the bottom of the ladder’ and educational standards for entry were ‘not so high as for other branches of the Public Service’. Men who had not progressed beyond fourth grade were accepted as policemen because the main prerequisites were physical rather than educational. Similarly, the eight-week induction period focused on drill and physical activity to prepare men for a constant round of foot-slogging on beat duty. Entrance standards and working conditions in the force prompted the view that it was a ‘dumping ground’ and that the rewards ‘were not sufficiently liberal to attract men of high character and ability when such qualities are in so much demand elsewhere’. Society wanted a force of respectable police, but ‘respectable’ men of educated and middle-class backgrounds did not join the police force. Of 250 men who joined the force during the years 1914 to 1918, almost 70 per cent were formerly labourers, or rural workers employed on such chores as shearing, dairying, mining, timber-cutting and farm work. Most of the others came from service industries where they had been employed as storemen, salesmen, gripmen, drivers and clerks. Eleven recruits had been tradesmen, one claimed he was an engineer, two claimed to be schoolteachers and one gave his occupation as ‘foot-runner’.

Although people seeking to determine the appropriate status and pay for policemen compared them with labourers, teachers, railway workers and public servants, none of these comparisons proved useful. Eventually all parties began to view the police as a distinct occupational group and to look at police forces in other states for realistic comparisons. This was a trend that suited policemen but worried the government; notwithstanding the boast of the premier, W. A. Watt, that Victorian policemen could ‘eat the New South Wales men for breakfast, without pepper or salt’, the policemen of his state received the lowest pay and benefits of any in Australia. Per capita expenditure on the police was higher in all the other states, police to population ratios were better, and policemen received more holidays and uniform benefits. Because of its comparable size, similar policing problems and proximity to Victoria, the New South Wales force was the obvious one with which to make comparisons. In New South Wales, policemen received twenty-eight days’ annual leave, were granted a rest day every second Sunday, worked continuous eight-hour shifts, were provided with free uniforms and were paid an average of two shillings a day more. Per capita expenditure on the police in New South Wales was 6s 7d and the police to population ratio was 1:698. In Victoria the equivalent figures were 5s 1d and 1:795. Because per capita expenditure and police ratios are closely linked to population dispersal, and New South Wales was much larger than Victoria, those ‘unfavourable’ comparisons are less significant than they might seem. However, the differences in pay and holidays were very real, and they rankled with policemen south of the border. That they were worth as much as schoolteachers in their own state was debatable; that they were worth less than policemen in New South Wales was untenable.18

For many decades a succession of governments relied upon the conservatism and ‘loyalty’ of policemen for industrial harmony. They did not unionise, strike or affiliate with the Victorian State Service Federation (VSSF), nor were they subject to Wages Board determinations. If policemen wanted increased pay or improved conditions they sent a deputation direct to the government, and if a government wanted to restrict or prevent protests by trade unions they sent in the police. It was an informal but traditional relationship, and government members spoke often of police loyalty. It was reinforced by the hierarchical and disciplined nature of the force and the large body of regulations that governed it. Those policemen who did publicly complain were quickly labelled as ‘agitators’ or put down as ‘younger and more impetuous’. In 1912 an unsuccessful police deputation did approach the government for increased pay and Watt, like many government leaders before him, imposed upon their loyalty when denying their claims, saying in parliament that ‘whilst they would like to get higher pay, they are not adopting a disloyal stand’. Such an understanding could continue only as long as the government was reasonably responsive to police deputations. It was at a time of increased worker unionisation that the Watt Government refused the police pay request, while agreeing to retrospective pay increases for railway workers and a pay rise for teachers, both of which groups had employee unions. A letter published in The Argus warned an ‘obdurate’ government that ‘perhaps the police association about to be formed, will bring about reforms and redress; but on the other hand, it is sure to create a fighting spirit in the ranks’.19

Apart from that letter, and some parliamentary talk about police ‘dissension and revolt’, there is no evidence of policemen attempting to form an association in 1912. The first concrete signs of such a movement occurred on 20 August 1913, when Sergeant Michael O’Loughlin of Albert Park submitted a report requesting permission to convene a meeting of police ‘to consider the questions of approaching the government for an increase of pay and the formation of a Police Association’. O’Loughlin was a seasoned veteran of thirty years’ experience in the force, so he could not be disregarded as ‘younger and more impetuous’. On the contrary, he was qualified for a full police pension and promotion to officer rank, and he put both at risk by seeking to unionise the police. His action, like that of Costelloe and Strickland nearly a decade before, was a bold one, but in 1913 the suggestion was not totally radical and did have precedents in police unions formed in South Australia (1911) and Western Australia (1912).

Even so, Sainsbury was caught unawares by O’Loughlin’s request and, in a letter marked ‘very urgent’, wrote to the commissioner of police in South Australia that he was ‘anxious to learn’ if the Police Association ‘tends to the welfare of members of the Force without clashing with the best interests of the Service’. The South Australian commissioner declared to Sainsbury, ‘Personally I am not very sweet on Police Associations’, and he heartened the Victorian chief commissioner when he reported:

The Association was formed during the regime of the Labor Ministry … immediately a Liberal Ministry came into power the Chief Secretary, our Ministerial Head, intimated he was not in sympathy with the movement, and in fact made it clearly understood the Government did not intend to recognize the Association in any shape or form, and though still in existence I have not since heard much of it. When first formed it rather looked as if the Association was to manage the Department, but now of course all that is a matter of the past.

Sainsbury liked the South Australian Liberal approach to police unions and, in a memo dated 1 September 1913, informed the under-secretary that ‘it would not matter much if a police association existed as long as the government took the view which the South Australian Government has taken’. O’Loughlin’s report, together with the correspondence from South Australia and Sainsbury’s comments, went before state cabinet on 4 September 1913, but if a decision was reached on that day, it was not then made public, nor was the urgency with which Sainsbury and the government treated O’Loughlin’s request intimated to him. Although he submitted additional reports in September and December, he was not given the courtesy of either an acknowledgment or reply. It was not until 10 February 1914, when the subject was raised in the Legislative Assembly by John Lemmon, a staunch Labor man and MLA for Williamstown, that the matter was publicly aired for the first time and O’Loughlin got his reply. The chief secretary, John Murray, told Lemmon that he had considered but not answered the application from O’Loughlin because it ‘was addressed to the Chief Commissioner of Police’, and that in any event he ‘did not think it was advisable to grant the application’.20

The curt and seemingly confident manner in which Murray dispensed with O’Loughlin’s application and Lemmon’s questions belied the trepidation with which the conservative government viewed the formation of a police association. O’Loughlin’s reports had not simply prompted a flurry of urgent activity behind the scenes, followed by intransigent silence, but had provoked the government into doing something. In the months after O’Loughlin submitted his first application, and before Murray gave his answer in parliament, the government sought to defuse the issues behind police moves to unionise by easing two long-standing grievances. On 5 September 1913 Murray announced that ‘members of the force are to be given one Sunday off in every four on full pay’. This announcement was made only four days after O’Loughlin’s report went before cabinet, but the rest-day issue was one that had been under government consideration since 1911, when Murray had said, ‘If we could only persuade the wicked in our midst—and there are not very many—to cease from troubling on Sunday, the police then might have the day off.’ Given that the wicked had not ceased troubling on Sunday, it would seem that Murray was more troubled by O’Loughlin than by evil-doers on the Sabbath. The rest-day scheme started on 1 October 1913 and ended the practice begun in 1836 of policemen being on duty every day of the week. The monthly day of rest fell well short of the weekly rest day granted to policemen in England since 1910, but it was an important concession, a milestone in the quest for improved working conditions. There was still a way to go, however, as the system devised by Murray and Sainsbury was introduced without employing any extra men and at ‘no increase in cost to the State’. It was made workable by those men on Sunday duty who, as well as walking their own beats, patrolled those of men on a rest day.

The introduction of a monthly rest day was met with general approval from politicians, policemen and the press, and it allayed some of the dissension within the force. O’Loughlin, however, was not silenced by a day off each month, and his reports of 19 September and 7 December pressed for a pay increase. Perhaps Murray and the government were influenced by O’Loughlin’s doggedness; at any rate, on 5 February 1914, Murray announced a police pay increase of 6d a day. Then five days later, on 10 February, he announced that he was not prepared to agree to O’Loughlin’s application for permission to form an association. As with the rest-day announcement, Murray’s moves of February 1914 were a timely piece of political work, clearly designed to stifle police unionisation. By partly satisfying the immediate needs of many policemen, Murray sought to remove O’Loughlin’s basis of support and to shore up the eroding, tacit understanding that policemen would be looked after.21

Still the efforts to unionise policemen did not stop. In April 1914 the annual conference of the Political Labor Council resolved to ‘take steps to form the police into an industrial union’, but members of the force were unanimous ‘that, while a union similar to the Public Service Association would be welcomed, any affiliation with the Trades Hall or other political body would be in every way inimical to the police and the public generally’. Policemen were wary about an alliance with the labour movement because they feared it would jeopardise their role ‘in preserving order’ at industrial disputes, and they were also concerned at the prospect of being called to strike in sympathy with trade unions. It was not an unexpected response from an occupational group as loyal and conservative as the police, but it was one that might well have troubled many thinking labour leaders. Policemen—those brawny toilers drawn from the working classes, and whose work conditions lagged well behind those of the general labouring community—were ready when on duty to intervene on behalf of capital in dispute with labour but unwilling off duty to join with other workers in trying to improve work conditions. In the early years it was a stance voluntarily adopted and maintained by policemen, but since the police strike of 1923 it has been a position reinforced by law. Either way, the division between policemen and the labour movement has proved enduring.

Although policemen resisted efforts to align them with industrial unions, they still wanted a union of their own. Later in 1914 a proposed meeting of policemen ‘to consider matters in their own interest’ was prohibited by Sainsbury because ‘practically it was for a political purpose’. This last movement to convene a meeting had barely gathered momentum when war was declared, inducing a pause in agitation as policemen threw their energies behind Sainsbury and the war effort. Apart from the two concessions granted at the time of O’Loughlin’s stirrings, the government had done nothing to improve conditions for policemen, so that even after the outbreak of war there was an undercurrent of dissatisfaction. National expectations of loyalty and personal sacrifice during the war rendered open agitation by policemen imprudent, but during 1915 city policemen interested in improved work conditions held secret meetings to plan the formation of an association. To avoid infiltration by ‘the other side’, notice of these meetings was spread by word of mouth and the meeting place was frequently changed. Usually they met in a hotel, but on at least one occasion their meeting was ‘held in a timber yard in South Melbourne at nearly midnight’. To this day the identity of the activists has remained secret, but the clandestine gatherings ended on 13 July 1916 when over two hundred policemen openly attended a meeting in the Guild Hall, Swanston Street, Melbourne. They elected Constable F. C. Murphy, of the Little Bourke Street police station, as secretary of a movement to press ‘for permission to form an association for the general improvement of the Service’.

Details of the Guild Hall meeting were reported in The Argus, and Sainsbury immediately ordered an investigation to ascertain ‘who called and authorized this meeting and who were the speakers at it’. Officers interviewed both O’Loughlin and Murphy as suspected organisers but, in a style befitting the classic coterie of conspirators, not one of the policemen who attended the meeting admitted knowing anything of its organisation. Using a statement obtained from the caretaker of the hall, Sainsbury’s investigators advised him that an unidentified ‘tall dark man engaged the hall and paid for it … He said he required the hall for a meeting of the Police Union’.

Although those men who attended at the Guild Hall were tight-mouthed about the original organisers, they went boldly into subsequent action. On 13 July 1916 Murphy wrote to the chief commissioner, asking him to receive a deputation ‘of the Members of the Force with a view to forming a Police Association … Such association to be non-political’. Sainsbury refused this request and Murphy wrote again on 7 August, appealing to the chief secretary to receive a deputation because ‘the police have always been a loyal body and are not now endeavouring to show any disloyalty’. Murphy pointed out that the penal warders and state school teachers had their association, and the police wanted one ‘for their own mutual improvement and defence’. Murphy’s second request was approved, with the proviso that ‘only members of the force will be heard’—a clause no doubt intended to exclude former policemen, politicians, the VSSF and other union organisers.

Policemen filled the Guild Hall on 21 August to elect the members of their deputation, and a conference with the chief secretary, Donald McLeod, was held two days later. McLeod viewed the prospect of a police union with the same disdain as had his predecessors and, after raising spurious objections to the police proposals, agreed only to ‘consider the matter of allowing the Police to form a Club for their own “Social Improvement and Mutual Benefit”’. Not surprisingly, Murphy and his colleagues were unhappy with such a response; then, just as their movement began to falter, they were given new and added impetus. On 28 December 1916 the Constitution Act was amended to give all public servants, including policemen, the right to ‘take part in the political affairs of the State of Victoria’. Generally termed the Political Rights Bill, the amendment was ‘highly prized by the service’ and, in giving policemen ‘full citizens rights’, promoted a surge of interest in state, political and union matters. This legislation enabled policemen to be far more open in political and industrial matters, and soon the VSSF joined with a Police Executive Committee to agitate for the right to form a police association.

By 1917 the force was the only sizeable section of government employees without an association, and Gordon Carter, general secretary of the VSSF, acted on behalf of policemen as ‘Honorary Special Representative’ to press for parity. Under his guidance the police committee lobbied with renewed vigour and framed a model constitution and rules for their proposed association. On 3 April 1917 perseverance was rewarded when McLeod agreed ‘to permit of a social club being formed, and to assist it as far as possible’. Some men spoke of a union, some of an association and the government of a social club; but that was all semantics. What policemen had attained was the right to form an employee organisation to protect their interests. On 10 May Sainsbury presided over a general meeting of six hundred men who ‘decided by a unanimous vote that an Association be formed’, and on 27 June an executive committee was elected.

One man who no doubt derived a great deal of personal pleasure from the events of 1917 was Michael O’Loughlin. He was prominent in all police agitation from 1913 to 1917 and, after being promoted to officer in 1917, was elected president of the association on 31 January 1918.

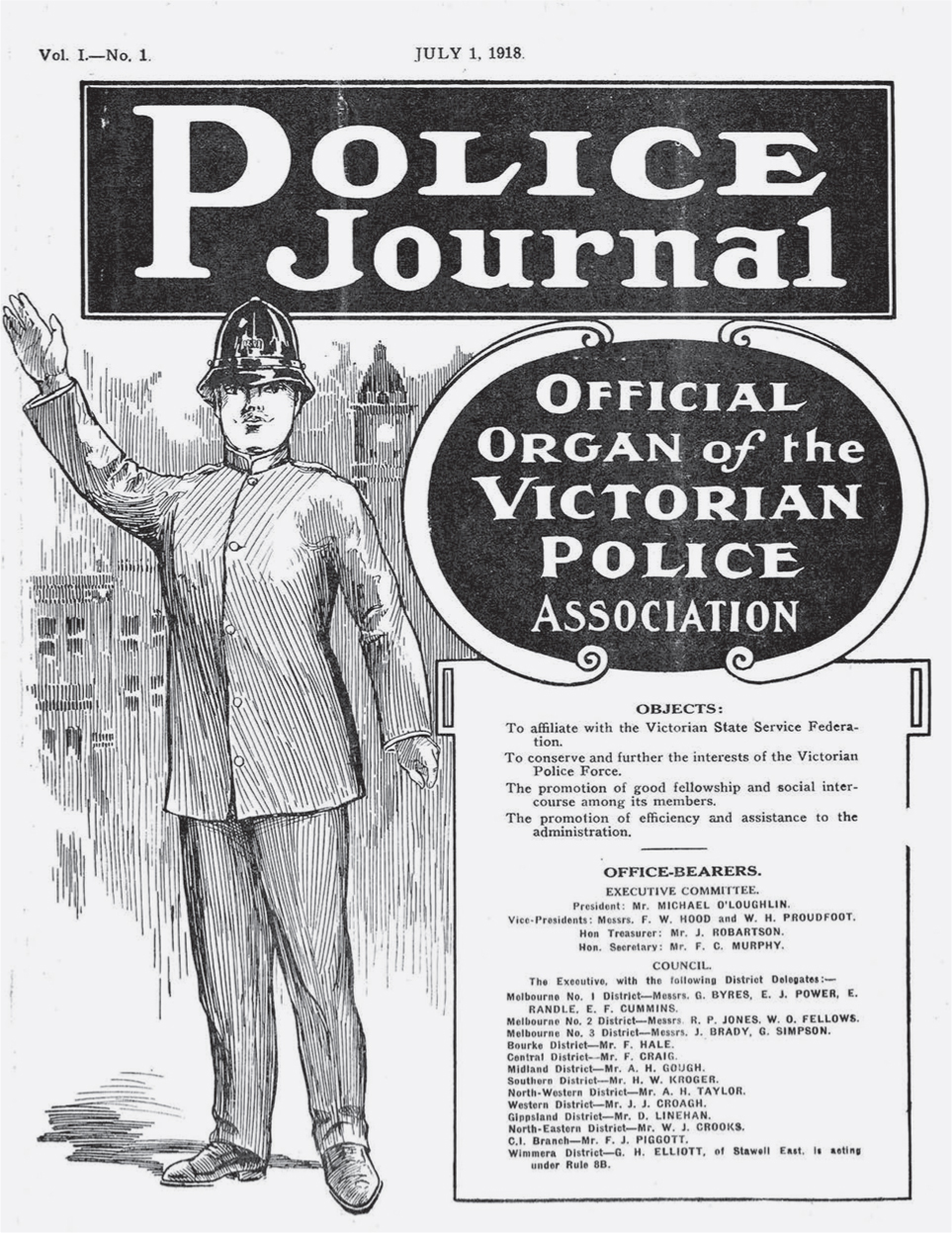

The objects of the association at the time of its formation were: to affiliate with the VSSF; to conserve and further the interests of the Victoria Police Force; the promotion of good fellowship and social intercourse among its members; and the promotion of efficiency and assistance to the administration. They were benevolent objectives suggesting that the government was successful in restricting the role of the association to one of a benign social club. It was a false impression. Behind the façade of smoke nights and billiards was an active and growing police union. Within months the association, supported by Sainsbury, was successful in obtaining government approval for policemen to work continuous eight-hour shifts and, from 14 January 1918, police hours of duty were 6 a.m. to 2 p.m., 2 p.m. to 10 p.m. and 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. This change removed a long-standing grievance of metropolitan policemen and brought their hours of work into line with those of policemen interstate and overseas. Some months later the association added to this success with a surprising coup, when the government responded to its wage deputation by granting all policemen ‘an increase in pay of sixpence per day and an allowance of another sixpence per day for uniform’. At a time of national austerity, and with war still raging in Europe, these were considerable achievements. Other matters dealt with included travelling and mountain-station allowances, extra leave, pensions, a khaki uniform for summer wear and the individual grievances of policemen regarding transfers, sick pay and legal expenses. The prospect of paying legal fees was a source of concern to most policemen, and the association was active in seeking compensation on their behalf. A typical case in 1917 was that of Constable Matthew Burke, who was charged by the Kew Council with misconduct ‘in not removing disorderly persons from a referendum meeting as instructed by the Mayor’. At a cost of £20 Burke engaged a solicitor to act on his behalf, and the board of inquiry that subsequently heard his case dismissed the charge and found that Burke had acted with ‘tact and forbearance’. Though he was innocent of an allegation that arose directly from his duties, the government adhered to normal policy in not providing Burke with legal counsel and refused to pay his legal costs of £20 because ‘he could have conducted his own defence’. Burke’s expenses in this case were equivalent to almost two months’ pay, and highlighted the injustices that existed, in spite of the presence of a concerned union.22

Although the association was much more than a social club, it was not a militant union and did pay heed to its stated objects of promoting efficiency and providing assistance to the administration. In this regard the association was instrumental in having a board appointed ‘to investigate the alteration of ages of members of the force’. It was an issue peculiar to police, and involved men who gave false birth details to gain admission to the force and then, at the other end of their service, tried to have those details corrected to improve their retirement prospects. The board devised a satisfactory solution and reported that the alteration of ages was due in large measure to ‘the connivance of those who had to choose the future members of the Force’, and who ‘winked at’ incorrect statements of age ‘in order that they might not have to reject the best material offering’. The board’s findings highlighted an irregularity in police recruiting methods dating back to the mid-nineteenth century, and in the light of these findings the system was changed. The decisions reached by the board were in the best interests of the force and met with approval from the association, even though some individual policemen lost retirement advantages. It was an early indication of the potential of the association to influence the administration of the force.

Another important action taken by the association was the monthly publication of the Police Journal. A modest publication of sixteen pages, it quickly became established as essential reading for all policemen and, as well as association news, it included law notes and items of general interest. The journal was particularly aimed at men who were ‘remote from a friendly comrade’, and articles on police topics of current interest reached the ‘back-block constable’ and filled an important need that had never been met by the department. After receiving his first issue, Constable F. A. Rawlings, stationed in the mountains at Walhalla, wrote to express his appreciation and approval. In doing so he articulated a common sentiment and gave a hint of how the force had unwittingly isolated many of its members by failing to provide them with police news and comradeship. Rawlings wrote: ‘we in the back parts seldom meet the city men. As for myself, I seldom come in contact with adjoining stations. My nearest neighbour is some 26 miles distant, through bad roads and hilly country’.

More than social intercourse: the Victorian Police Association journal in 1918

The gratitude felt by Rawlings for the association was not shared by his chief commissioner. At the association’s first annual meeting a letter from Sainsbury was read, in which he put the view ‘that what was intended was bringing into existence of a social club only, and not a body formed to work together towards securing justice for itself’. His lament was, however, too late and although he and the chief secretary tried to restrict the association’s activities by censoring its business papers, it continued to gain strength. Years of government neglect had left policemen ripe for unionisation, and the substantial early gains made when they did combine served to increase their enthusiasm. The association ended its first year of existence with an ‘optimistic outlook’ and 1346 financial members, who had attained better hours, increased pay and a uniform allowance: ‘There were only 70 to 100 members of the whole police force who had not thrown in their lot with the majority.’23 Not included in this minority were two new additions to the force who might have joined the association if they could, but were not eligible. They were women. While O’Loughlin fought officialdom and Sainsbury fought unionisation, the Trades Hall Council was among those groups that had successfully supported the entry of women into the police force.

In his early resistance to police unionisation, Sainsbury displayed a real fear of having his power and authority usurped by an association that wanted to ‘manage the Department’. It was a fear that proved groundless, as did his fear that, if women were appointed to the force, ‘trouble could be expected and the question of deciding who is “the boss” might soon have to be determined’.