For Victoria Police the closing decades of the twentieth century and the nascent years of the ensuing century were action packed. An era of untold violence, it was also a time of significant industrial and social upheaval. The 1980s witnessed the beginnings of bloodshed of a kind not seen before in Melbourne, as the gangland killings extended into the 1990s and the next century. It was an era when the policeman’s lot became the policewoman’s lot, too; when Victorian forensic scientists led the world with developments in DNA research; when, on many fronts, police leaders were challenged by accusations of systemic racial profiling, underscoring the multicultural and socio-economic mix of the world in which they worked; when rampant rates of domestic violence and crimes against women confronted all Australians, demanding that police do more; and when child pornography and child sexual abuse shocked and disgusted a nation. And when a ubiquitous, toxic drug nicknamed ‘ice’ wasted young lives and was anything but cool. It was also an age when citizens took to the streets in their thousands, reclaiming public space and the city after dark: creating a paradigm shift that heightened community symbiosis and witnessed an unprecedented focus on criminal justice and public policy, notably on the parole system.

Chief Commissioner S. I. ‘Mick’ Miller led the way and was the genesis of much of the police response to this change. Arguably the most influential Australian police commissioner of the twentieth century, he not only consistently set new benchmarks for others to follow but spawned the new centurions. A cadre of Victoria Police officers at the top of their game, they were selected to head police departments in South Australia, Western Australia, Queensland, Vanuatu and Tasmania. Other Victorian police were appointed to senior positions in the Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence (ABCI), NCA, National Police Research Unit, Queensland Criminal Justice Commission and Queensland Police Service.

Always in a state of flux due to workforce attrition at command level, the policing landscape changed frequently. Kel Glare, one of Miller’s acolytes, replaced him as chief commissioner in 1987. Neil Comrie was enticed back from a stint in post-Fitzgerald Queensland to replace Glare in 1993. He in turn was succeeded by New South Wales assistant commissioner Christine Nixon. Appointed in 2001, she was the first woman to head a police service in Australia. And this was a harbinger of things to come. Nixon was succeeded in 2009 by Simon Overland, whom she had initially head-hunted from the Australian Federal Police after a chance meeting in Alice Springs. His short stint in office ended prematurely in a bitter political imbroglio in 2011. In a populist return to the status quo, Overland was succeeded by Ken Lay. Nixon’s former chief of staff and a career member of the force, Lay was a beneficiary of the ‘Bradbury factor’. In a clear indication of the demanding nature of the role of chief commissioner on incumbents and their families, Lay, like Comrie, Nixon and Overland before him, opted to retire early.

Graham Ashton, who had previously served as a deputy commissioner in both the Australian Federal Police and Victoria Police, replaced Lay in 2015. In a first for Australian policing, Ashton’s command team for a time included two female deputy commissioners: Lucinda Nolan and Wendy Steendam. They had previously been appointed assistant commissioners, West and East respectively, by Overland on 11 June 2010. Nolan, the force’s first female deputy commissioner, was appointed deputy commissioner (strategy and organisational development) in 2012. An exemplar of policing in the twenty-first century, she was married to a police officer and was a mother of three children, including a son with Asperger’s syndrome. Nolan served with the Victoria Police for thirty-two years and excelled in every aspect of her career. She held a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) and a Master of Arts from the University of Melbourne, and her string of post-tertiary qualifications included a stint at Harvard University. Dux of her police training squad, she was an accomplished general duties officer and investigator who also duxed her Detective Training School course and in 1989 was adjudged DTS Student of the Year. No mere armchair theorist, in 1991 she was seconded for three years to the Spectrum Task Force. Following the appointment of Ashton, Nolan resigned on 9 November 2015 to take up the ill-fated position of CEO at the Country Fire Authority.1

Prior to leaving the force Nolan was joined briefly by Deputy Commissioner Wendy Steendam, who officially commenced her new role on 7 September 2015. A thirty-year veteran with an eclectic policing background, one of Steendam’s major strengths was her extensive experience in policy development and implementation at both supervisory and senior management levels. She was appointed chief information officer and was involved in the development of the Victoria Police’s violence against women and children strategy. A holder of the cutting-edge Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) degree Executive Master of Public Administration, her initial brief as deputy commissioner was to ‘look at innovative opportunities to enhance the way Victoria Police worked’.

It signalled yet another fresh beginning for the force, which was still watched over with abiding interest by Mick Miller. His sage advice to Christine Nixon on her appointment counselled: ‘You have been given temporary custody of a police organisation which has existed since 1853 and which, during that time, has experienced the highs and lows of its development to what it is today. You are not the first to have been accorded this honour and you will not be the last. Depending upon how [you] address your responsibilities, you could prove to be the best. However, that will be for history to judge’. And in a prescient last word he reminded Simon Overland: ‘Nothing is forever …’

We trained hard—but every time we were beginning to form up into teams, we would be reorganised. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganising, and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralisation.

In the last decade of the twentieth century, the above satirical quotation by ‘Project Arbiter’ was displayed in police offices throughout Victoria. This insubordinate lampooning of mismanagement grew from its initial use by force command as the title for what became a generally unpopular administrative reform project. It was an apt description of the force, which in the years following 1984 underwent tumultuous organisational disruption. The fabric of the force was being rent from within and without, moving Chief Commissioner Kel Glare to express concern at the ‘levels of disquiet’ and plead, ‘Policing has never been easy—there is no job where so much is asked, so consistently, and under such stressful and thankless conditions’. He went on to say, ‘but trying to institute change in a police force is no easier’.2

The force was no stranger to violence, but a series of events during the 1980s surpassed even the Kelly years for wanton bloodshed, and the 1980s remain the bloodiest decade in the history of the Victoria Police. Some of this violence was perpetrated by police and much of it was directed at them. Other atrocities to touch the force were random mass killings committed in public places, where lone gunmen killed and maimed innocent victims; and the perpetration of vicious aggravated burglaries, principally targeting young girls in their own homes.

The worst of the atrocities, which investigators suspected spanned a decade, remain unsolved, and were attributed to a lone offender dubbed ‘Mr Cruel’ by sections of the Melbourne media. Although the first of these callous crimes is believed to have occurred around 1985, it was the criminal abductions of two girls, Nicola Lynas and Karmein Chan, who were taken from their family homes in July 1990 and April 1991 respectively, that shocked the nation. Karmein was murdered. These abductions led to one of the most complex police investigations undertaken in Australia. The Spectrum Task Force, formed in 1991, did not catch Mr Cruel and was disbanded in January 1994, but in the course of its investigations members of the forty-strong task force travelled throughout Australia, analysed more than 10 000 items of information, checked 30 000 homes with possible links to the abductions and murder, examined more than 27 000 persons of interest, and conducted interviews in Britain and the USA. Although the Chan murder remained unsolved, a by-product of Spectrum’s investigations was the prosecution of seventy-four people for offences including rape, incest, blackmail and possession of child pornography.3

The first of the multiple murders occurred on 9 August 1987, when Julian Knight walked along Hoddle Street, Clifton Hill, indiscriminately shooting at passers-by, killing seven people and injuring nineteen others. He was later arrested near the scene, but the horror of his crimes traumatised many police and community members and necessitated an ongoing programme of individual and community counselling. Knight pleaded guilty to the murders and was sentenced to life imprisonment. The Hoddle Street shootings were still affecting the lives of many Melburnians when, on 8 December 1987, Frank Vitkovic entered an Australia Post building in Queen Street and went on a shooting rampage, killing eight people before killing himself by jumping from an upper floor of the building. It remains the worst mass murder in Victoria’s history.

These crimes profoundly affected the Victorian community and sparked intense public debate on a range of law-and-order issues, in particular the question of gun control and the broader issues of future directions for policing and enabling powers for police. The force, after five years of Labor government, was the most legislatively restricted police service in Australia. It lacked basic powers available to police in most English-speaking countries, such as the power to obtain photographs, fingerprints and biological specimens from criminal suspects. Chief Commissioner Miller had lamented in 1985 that ‘The lack of these enabling powers produces some incredible consequences’. Two years later, in his final annual report, he expressed regret that he had been unsuccessful in obtaining enabling powers ‘available to other Australian police forces’, further observing that civil libertarians had ‘remained strangely silent about the fate of victims of crime’. He thought that this lack of action reflected ‘a preoccupation with philosophical abstraction at the expense of practical reality’.4

Stark evidence of the practical realities of policing during the force’s deadliest decade can be found in the plethora of motor vehicle accidents, shootings and other violent incidents that befell twenty-one members killed on duty in the space of ten years. Despite the publicity surrounding police shootings, the ‘deadliest weapon’ was in fact police motorcycles, which caused Miller to lament that the dangers ‘faced by police motorcyclists every time they took their bikes onto the roads were demonstrable, because as a unit of the force, they incurred a higher fatality rate than any other unit, squad or branch’. In the years from 1950 to 1979 twelve police motorcyclists were killed on duty, followed by a further four in the early 1980s; six of these were on Miller’s watch. This ‘alarming fatality rate’ prompted Miller in 1982 to convene an assembly at the Police Academy of every available police motorcyclist. His ultimatum to them was a threat ‘to abolish the use of motorcycles as a component of the Traffic Operations Group, if there was another accidental police motorcycle fatality in the next six months’. As a call to action Miller’s ultimatum was a masterstroke that served as a catalyst for changes in police motorcycle-rider culture, policy and practice. Not only was his six-month challenge met, but the remaining five years of his commissionership were free of operational police motorcyclist fatalities, the only death being that of Senior Constable Peter Ross Smith in 1987, when on a training ride his motorcycle left the road and struck a tree. Since his death there has not been a police motorcycle fatality in Victoria.

Almost on a par with the rate of police motorcycle-rider deaths was the number of members killed in motor-car accidents. In the 1980s, eight members were killed in car accidents, including the force’s first multiple-vehicle fatality. Constables Walter Hewitt and Shaun Moynihan were killed on 27 November 1981 when, in pursuit of a speeding motorcyclist, their police vehicle collided with a divisional van. A further six members were killed in motor-vehicle accidents in the 1990s, but the most poignant incident occurred in 2000, when senior constables Fiona Robinson and Mark Bateman died in the second multiple police vehicle fatality in the force’s history. At 2.20 a.m. on 20 May 2000, the Northcote divisional van, an older-style Holden Commodore van, was responding to a burglar alarm. Travelling along High Street, Northcote at a relatively slow speed (estimated at 37 km/h), with its emergency lights operating and in the course of overtaking slower traffic, the van clipped another vehicle before rolling and smashing, roof first, into a utility pole. Robinson and Bateman were killed instantly.

The iconic police ‘divvy vans’ had been the ubiquitous front-line workhorses of the force for decades, but were always bedevilled by design shortcomings and inherent operational limitations. Just as the death rate of police motorcyclists led to significant changes in motorcycle usage, the deaths of Robinson and Bateman prompted a force-wide review of police vehicle safety, with a particular focus on the design and safety of divisional vans. An investigation into the accident found that the model of van used by Robinson and Bateman ‘was twice as likely to tip over in a collision as the utilities previously used by the force’. As a result, 148 Commodore vans were recalled and as an interim measure were replaced with a new fleet of modified Ford utilities.

Concomitant with this action was the development of a fleet safety strategy and the production of a custom-built four-door Holden police divisional van that set new national standards for safety, stability and functionality. Built by Holden Australia in consultation with the Monash University Accident Research Centre, prototypes were road-tested by police in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland before the van was launched in Victoria in March 2006. In a tribute to Robinson and Bateman, Northcote was the first police station to receive a new van in an initial roll-out of 140 vans across Victoria. Since then, none of the new-age ‘divvy vans’ have been involved in a fatal collision.5

Although motor-vehicle accidents accounted for most police deaths, fatal incidents involving the use of firearms, whether accidental or felonious, attracted the most public attention and controversy. During the 1980s seven members were shot and killed, including Constable Neil Clinch, who died at Fawkner on 5 April 1987 after being accidently shot in the head by a colleague in the course of restraining an armed offender.

2005 Crewman divisional van

The first police homicide of the decade occurred on 28 January 1982. Senior Constable Stephen Henry was patrolling the Hume Highway between Melbourne and Seymour on solo motorcycle duty when he was shot and mortally wounded at Wandong by Peter Reid, an escapee from a Sydney mental hospital. Henry was attempting to intercept Reid for traffic offences when Reid shot him in the head with a sawn-down .303 rifle. Henry never regained consciousness and died in hospital on 1 March 1982.

The next fatal shooting of a police member was the tragic death of Constable Claire Bourke in the watch-house at the Sunshine police station. On 16 March 1983, she was shot and killed in a ‘joke’ by Dog Squad member Senior Constable Michael Duffy. Mistakenly thinking that his firearm was loaded with a ‘blank’, he pointed the gun at Bourke and pulled the trigger, shooting her through the heart with a live round. Duffy was suspended from duty and charged with manslaughter but was acquitted by a jury.

These fatal shootings, of and by police respectively, were followed in a matter of months by the cold-blooded murder of Senior Constable Lindsay Forsythe, the officer-in-charge of the one-member police station at Maldon. Forsythe’s wife, Gayle, was having an affair with Senior Constable Leigh Lawson of Castlemaine. During the evening of 22 June 1983, Gayle lured her husband to a deserted location by lying to him that ‘an old lady had reported a suspicious light in a farmhouse’. On arriving at the scene, Forsythe was ambushed by Lawson and blasted at point-blank range with a shotgun. Lawson was convicted of the murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, while Gayle was convicted of manslaughter.

On 22 November 1984, Sergeant Ron Fenton was shot in the head at Beaumaris. The gunman, Kai Veli Korhonen, was a psychopath who had earlier murdered an unarmed security guard and was also responsible for shooting a news helicopter, causing $75 000 damage. (Fenton was critically wounded but recovered sufficiently to eventually return to duty.) This was followed on 18 June 1985 by the shooting of Sergeant Brian Stooke and Senior Constable Peter Steele, who were both wounded while questioning a burglary suspect at Cheltenham. A few hours later the same gunman was encountered by Sergeant Ray Kirkwood and Constable Graeme Sayce at Noble Park. Kirkwood was shot and wounded; Sayce, trapped in a police car, narrowly escaped injury when the offender repeatedly shot into it, shattering the headrest of Sayce’s seat and grazing his head with a bullet. The mayhem did not end there. Shortly afterwards, dog-handler Senior Constable Gary Morrell was shot by the same offender and only saved from serious injury by his ballistic vest. The gunman was identified as Max Clarke, alias Pavel Marinoff or ‘Mad Max’, and after an exhaustive manhunt he was killed in a gun battle with police at Wallan on 25 February 1986. Sergeant John Kapetanovski and Senior Constable Rod MacDonald were seriously hurt in the shoot-out and subsequently received valour awards.

The wounding of so many police in such a short space of time was yet another example of the violence that was a hallmark of the 1980s. An unprecedented fifty-five valour awards were presented during this time, a number that was well in excess of that for any other decade since the inception of the award a century earlier. In 1983 Paul Mullett, then a detective senior constable in the Major Crime Squad, became only the third member to receive the award a second time, in circumstances that his superiors described as ‘bravery and professionalism … displaying exceptional courage far beyond the norm’.

Chief Commissioner Miller described the shootings during this period as among ‘the blackest few hours in Victorian police history’, and with sad prescience added, ‘These were not the first Victorian policemen to have become casualties as a result of criminal attack. Nor, regrettably, will they be the last’.

On the Thursday before Easter, on 27 March 1986, a car bomb was exploded outside the Russell Street Police Complex. The blast hurled debris over the ten-storey building, shattering every window up to the seventh floor and causing property damage estimated at $1 million. It also injured twenty-two police and civilians and killed Constable Angela Taylor, who sustained serious burns to most of her body. Taylor was a bright and popular constable who had graduated as dux of her recruit squad little more than a year earlier. In his eulogy the police surgeon, Dr Peter Bush, described her as a ‘symbol of youth, of dedication and loyalty, of efficiency and discipline. She is also a symbol of vulnerability’.

Four men stood trial for the bombing, an act motivated by a hatred of police. The car, packed with about fifty sticks of gelignite, was originally intended to detonate inside the Police Complex quadrangle but was instead detonated at a main door while the offenders waited nearby to observe the result. The miracle was that only one person was killed. The cowardly bombing—and in particular the death of Taylor—shook the force, generating a solidarity born of fear, anger and bitterness and moving even the usually gracious Miller to sourly note that, of hundreds of tributes and expressions of sympathy received from all over Australia, there was ‘not one tribute from any of the civil liberties groups’. Nor would there be.

Within months these same sentiments again swept the force when Senior Constable Maurice Moore was murdered at Maryborough. On 27 September 1986 Moore was returning to the station from his home, where he had gone to get some milk for his night-shift crew, when he encountered two men stealing a motor vehicle. Soon after, Moore was dead—shot five times with his own service revolver. The murderer was a well-known local identity named Robert Nowell, who had a reputation for violence and a hatred of police.

The abhorrent and unprecedented wave of extreme violence was not restricted to murderous attacks on police. On 24 November 1986, the peace in Caroline Street, Toorak was shattered when a car bomb exploded in the car park of the Turkish Consulate, killing Hagop Levonian, one of two terrorists involved in the attack. It was suspected by investigators that the bomb had detonated prematurely. Levon Demirian, a resident of Sydney with links to an Armenian terrorist group, was charged and convicted of murder and conspiracy, but on appeal to the full Supreme Court the murder conviction was quashed. Wayne Rotherham was a detective in the Major Crime Squad who attended at the scene, and he later lamented that the bombing came at a time ‘when the world seemed to be going mad and everything was becoming more complicated’.

The criminal crusade of violence then washing over the force and the community at large did not end with the deaths of Taylor and Moore or the Turkish Consulate bombing, but climaxed on 12 October 1988 when constables Steven Tynan and Damian Eyre were ambushed and murdered in cold blood in Walsh Street, South Yarra. The two young constables were responding to a call to check an unattended suspect vehicle and were blasted at close range with a shotgun in what was generally accepted as an ‘ambush and execution of two police because they were police’.

Four well-known criminals stood trial charged with the murders: Victor Peirce, Anthony Farrell, Peter McEvoy and Trevor Pettingill. All four were controversially acquitted at the Supreme Court in Melbourne on 26 March 1991 when a key witness, Peirce’s de facto wife Wendy, reneged on an undertaking to give vital evidence against the accused men; Wendy was subsequently convicted of perjury. Following the 2002 gangland murder of Victor Peirce, in a belated dénouement in 2005, Wendy Peirce publicly admitted that Victor had organised and participated in the killings of Tynan and Eyre.

There is little doubt that Tynan and Eyre were murdered by members of Melbourne’s criminal underworld as payback killings for the death of convicted armed robber Graeme Jensen, who had been shot and killed by police only thirteen hours before the Walsh Street shootings. A violent career criminal, Jensen had committed his first bank robbery when aged only fifteen. Eight members of the Armed Robbery Squad intercepted him when he was alone and allegedly armed in his car at Narre Warren. All eight detectives were subsequently indicted for murder but only one, Robert Hill, who fired the fatal shot, stood trial for the killing; he was acquitted on 9 August 1995.6

One police death linked inextricably to the death of Jensen and the imbroglio surrounding him was the suicide of Homicide Squad Detective Senior Sergeant John Hill. A highly respected investigator who had joined the force in 1967, Hill investigated the shooting of Jensen, collecting twenty-five exhibits and interviewing 145 people for a 503-page inquest brief. Despite his belief that his investigation was comprehensive, he was ‘torn apart’ at the inquest and subsequently charged on direct presentment by the director of public prosecutions, Bernard Bongiorno, QC, with being an accessory to murder ‘in that he impeded the investigation’. Of this insensitive treatment at the hands of the legal system his wife noted: ‘We had to take the deeds of the house to court so John could make bail. He then had to report to the local police station as part of his bail conditions. It was so humiliating for him’. He never recovered from that ordeal, either personally or professionally, and took his own life in 1993. After the acquittal of Hill on a charge of murder, Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie broke his public silence on the matter and said of Hill’s death, ‘John Hill was regarded as the ultimate Homicide Squad detective. He was the mentor to whom all other Homicide Squad detectives turned for guidance and inspiration. His death was a tragic loss to the force and the community. It will be felt for years to come’. The John Hill Memorial Award for most promising investigator was introduced in his honour in 1999.

Certain of Melbourne’s criminals had expressed fear and loathing of police over a number of fatal police shootings, and there was also considerable community disquiet at the frequency and nature of these shootings: at one point a television documentary described Victoria as the ‘police shootings capital of Australia’. Between 1982 and 1994 a total of thirty-four people were shot and killed by police in Victoria. This compared with fifteen for the rest of Australia, of which seven were in New South Wales. During 1988–89 there were seven fatal shootings by police in Victoria, including those of Jedd Houghton and Gary Abdallah, who were believed by some police to be linked to the deaths of Tynan and Eyre. Houghton, who was killed when Special Operations Group (SOG) police raided a caravan near Bendigo on 17 November 1988, was later described by Magistrate Hugh Adams as ‘an active participant in the Walsh Street murders’. Abdallah, who was never positively linked to the murders of Tynan and Eyre, died on 19 May 1989 after being shot seven times by police in Carlton on 9 April 1989, allegedly after he had threatened them with an imitation pistol. Two detectives, Clifton Lockwood and Dermot Avon, were charged by the director of public prosecutions with the murder of Abdallah, but they were acquitted after a Supreme Court trial in 1994.

Following the police shootings in 1988–89 there were widespread calls for a judicial or public inquiry. Subsequently the state coroner, Hal Hallenstein, conducted a coronial investigation that became known as the Police Shootings Inquiry. Hallenstein investigated seven deaths, including those of Jensen, Houghton and Abdallah, beginning his deliberations in July 1989 and finishing hearing evidence in December 1991. He produced 40 000 pages of evidentiary transcript but did not deliver his first findings—those relating to the death of Gerhard Sader, who was shot by police in 1988—until June 1994. Throughout this period the shootings by police continued, with a further nine people being killed in 1994 alone.

In his findings for the Sader matter, Hallenstein commented in general terms of all seven deaths that they reflected inadequate police training and a ‘police ethic and culture of public duty requiring courage in physical exposure to personal risk’. His unequivocal conclusion was that substantive change was needed to the operational use of firearms by police, a change ‘attainable only by implementing a tight, conservative and restructured firearms policy’.7

For many people the findings were too long in coming and the force was equally slow in developing its own response to stop the killings. In 1992 Father Peter Norden wrote:

There is serious concern in the community about police use of ‘deadly force’. Is it necessary for all police officers to carry firearms at all times? Have the occasions on which police have used their firearms always been justified? Are there any situations where police have killed citizens where it simply has not been necessary? Are there other strategic police responses which could have been implemented to avoid persons being killed in the course of police making arrests?

On 1 June 1989 the force formed the Firearms and Operational Survival Training Unit (FOSTU) to standardise and manage firearms and operational survival training, and also issued long polycarbonate batons to operational members on patrol, to fill the void between the use of bare hands and the use of firearms in dangerous situations. The introduction of FOSTU training and the issue of long batons was in part a belated response to the dual problems of killings of and by police. The emphasis on increased protection for police was symptomatic of the ‘vulnerability’ described by Peter Bush and starkly described by FOSTU in a monthly training bulletin: ‘There is no doubt that the dramatic escalation in violence over the past decade, and in particular the more recent period, has had a profound effect on members of the police force and the community in general. Incidents such as Queen Street, Hoddle Street, Walsh Street, Russell Street [bombing], the Turkish Consulate [bombing] and the Mad Max saga have catapulted the Victoria Police Force into the new decade, with a stark realisation for the need to reassess the way in which we train, prepare and equip our operational police to cope with front-line duties’.

During 1988 and 1989 more than two thousand police were assaulted—209 seriously—and police attended 166 incidents in which firearms were used or threatened to be used against them. The incidence of deadly force used against and by police in Victoria during these years was extraordinary, as was the force’s almost total absence of enabling powers. Many police thought that their relative operational vulnerability and impotence was both emboldening criminals and frustrating police, with fatal consequences. The escalation in fatal shootings by police was arguably due in part to their heightened sense of vulnerability and partly to FOSTU-enhanced proficiency in the use of firearms, which was not matched by the development of other conflict resolution skills.

It was not until 1994, amid calls for a royal commission, that the force adopted a range of significant initiatives to tackle the problem. In a flurry of activity, the force complemented its own internal reviews and the work of Hallenstein by initiating four independent reviews by the Australian Institute of Criminology, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the National Police Research Unit. Collectively these reviews, augmented by the findings of relevant coronial inquiries, resulted in 219 recommendations, which were constantly monitored. On 6 April 1994, the chief commissioner wrote to all commissioned officers espousing what was effectively the new force mantra, Safety First: ‘the success of an operation will primarily be judged by the extent to which the use of force is avoided or minimised’.

On 19 September 1994, Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie launched Project Beacon, with the goal to ‘effectively implement the minimal use of force philosophy as a key element in all force operations, whether planned or unplanned’. A high-profile programme initially headed by Assistant Commissioner Ray Shuey, Project Beacon commenced with 8100 police undergoing five days of intensive training on defensive tactics, conflict resolution, dealing with mentally impaired people, and the use of firearms. Comrie observed that Project Beacon ‘resulted in a remarkable cultural shift in the attitude of police which saw a significant decrease in police shootings and a reduction in injuries to police and others involved in critical incidents: in the 19 months to 30 June 1997 there was only one fatal shooting by police’. So successful was Project Beacon that it was embedded into the culture of the force and members were required to attend a two-day operational safety and tactics training course every six months.8

The operational vulnerability felt by the force was traumatic, but in an era of increasing public accountability and rapid reform there was little escape in the familiar surrounds of routine duties and police offices. This was exemplified throughout 1985–86 during the Continental Airlines imbroglio, an entanglement that led to the downfall of the governor of Victoria, Rear Admiral Sir Brian Murray, and the death of airline executive Robert Tanfield, together with the premature retirement of Assistant Commissioner Bob Stewart and the besmirching of almost twenty other police who were never charged with any criminal or disciplinary offences. The investigation centred on the acceptance by police and others of discounted airfares from Continental Airlines, allegedly provided by Tanfield and facilitated by Stewart. It lasted fourteen months, during which time 21 000 documents were examined and 235 people were interviewed. Amid suggestions of political interference and chicanery, details of the investigation, including the names of innocent officers, were leaked to the media, creating a public perception that there was indeed a ‘scandal’. In fact, the publicity, innuendo and accusations of criminal conduct came to nought: the charges against Stewart were never proceeded with, and six police were reprimanded for their indiscretion in accepting discount airfares. It was a testing period for Chief Commissioner Miller and his successor, the man who headed the probe, Assistant Commissioner Kel Glare, and highlighted the degree of organisational integrity sought but not always achieved for the force by these two men. It is debatable whether the sacrifice of innocent others in this process was justifiable. It did, however, set a national benchmark for police accountability in all forces.9

Mick Miller retired from the force on 28 November 1987 after forty years’ service, ten of them as chief commissioner. Although not a tertiary graduate himself, he championed the pursuit of higher education for police and fostered a cadre of influential senior officers who were almost all university educated.10 He tried to give policing a new focus that emphasised professional standards, personal integrity, public accountability, proactive community-based initiatives and sophisticated criminal investigation techniques. Miller was the elder statesman of Australian policing, with a national profile and a measure of influence and public credibility not achieved by any of his predecessors. He often stressed the importance of leaders identifying, fostering and grooming their successors and was confident that he had done so. However, there was a perception in sections of the force that his personal stature was such that his retirement left a worrisome void.11

Miller was succeeded as chief commissioner by Kelvin Glare, who was appointed by the Labor government of John Cain, Jr—the first Labor government appointment of a chief commissioner since Selwyn Porter’s appointment by the Labor ministry of John Cain, Sr in 1955. A career policeman with a degree in law, Glare had joined the force in 1957, qualifying as a fingerprint expert and also serving in the uniform branch and CIB at a number of suburban and rural locations. In the early 1970s he had been in the vanguard of a small group of police who undertook part-time university studies, very often without peer support or study leave and while still carrying a full-time police workload. Together with another police law graduate, Bill Horman, Glare later pioneered the implementation of specialist police prosecutors’ offices to conduct criminal prosecutions in the Magistrates’ Court jurisdiction. This initiative significantly raised the standard of police prosecutions and freed many sub-officers from an onerous task for which they were often not suited.

Before his appointment as chief commissioner, Glare held the positions of assistant commissioner (internal investigations; then operations) and deputy commissioner (operations). Whereas Miller had been a charismatic leader with a high personal profile, Glare was a dour administrator who lacked his predecessor’s commanding presence and gift for oratory. Evidence of this dissimilarity was the disquiet surrounding Glare’s notable absence at the funeral service for Damian Eyre in Shepparton on 14 October 1988. Although Glare might have had good reason, and he did make it to the funeral of Steven Tynan two days later in Melbourne, it would never have done for Miller, and demonstrated very publicly that there had been a change of style at the top. Glare later observed that his decision not to attend the funeral of Eyre was one that he ‘regretted for a long time after’.

The shift from Miller to Glare, with its inherent differences in management style and reform programmes, was accurately described by Glare as ‘one of the most turbulent transitional periods’ in the force’s history. It was exacerbated by government funding constraints and personnel shortages. In August 1985 the Police Service Board granted members of the force a thirty-eight-hour week, which it was agreed would be taken as an additional ten days’ leave each year. No allowance was made in police recruiting to compensate for this reduction in working hours. Initially, police were paid in lieu of their accrued time off, but from 1 January 1987 all 8978 members of the force were required to take their extra ten days’ leave—an effective annual loss of almost 18 000 working weeks or the equivalent of more than three hundred full-time personnel.

Chief Commissioner K. Glare

This diminution in the force’s ability to provide optimum levels of service to the community worsened significantly in 1987, when the Emergency Services Superannuation Act became effective in the form of the Emergency Services Superannuation Scheme (ESSS). The new scheme was created in recognition of ‘the arduous nature of emergency services, and the consequent need to provide operational officers with realistic options for early retirement’. Providing lucrative early retirement and vesting benefits for members, it sparked the most significant exodus of personnel from the force since the police strike in 1923. One of the main differences, however, was that the 1923 losses were almost solely from the constable ranks, whereas the ESSS opened the way for the departure of many mature and experienced officers. Chief Commissioner Miller described it as ‘an extraordinary brain drain’. It left the force with 78 per cent of all members being under the age of forty years. In the four years preceding the ESSS a total of 1318 members left the force, including 102 officers; during the next four years 3132 members departed, of whom 279 were officers, eleven of them commissioners. Although the loss of these people placed enormous pressure on those who remained, Miller expressed confidence that the force was resilient enough to cope. He was right: many members suddenly experienced a steep learning curve, but overall no critical aspect of the force’s operations foundered. Later, Chief Commissioner Glare gave the outcome of this exodus a positive focus, describing the majority of the force as young and articulate, a fresh force emerging into a new era of ‘stability and success’.12

But that was a mixture of prophecy and hope—first, there was more change and pain. The Committee of Inquiry into the Victoria Police Force, known as the Neesham Committee, presented its report containing 220 recommendations for action to the minister, Race Mathews, in 1985. An implementation steering committee chaired by the minister and including the chief commissioner and a joint working party, chaired by the secretary of the ministry and including the Police Association and Public Service Association, were subsequently formed to examine and progressively implement the Neesham Committee recommendations, some of which were as prosaic as a proposal to examine ‘the relative merits of police torches’, but others of which were far-reaching and led to major administrative changes.13

Project Arbiter was the name given to the programme of administrative reform that grew from the Neesham Committee proposals. It was a reorganisation that at times produced confusion and demoralisation, an experience that caused some lamentation in hindsight that the project title was too negative—and too apt. At different points in the Arbiter process, Chief Commissioner Glare lamented that the force was ‘going through a painful era’ and said that he was concerned that it was ‘being undermined by selfishness, rumours, misinformation and gossip’. Resistance to the changes in some sections of the force was openly subversive.

The Project Arbiter team, led by Assistant Commissioner (Research and Development) W. H. ‘Bill’ Robertson, began work in August 1988, and the restructure was implemented by the Operations Department on 4 March 1990. The first phase focused on the Operations Department because it was the largest component of the Victoria Police, containing 7090 personnel, or 68 per cent of the force. The changes included a reduction of police districts from twenty-three to seventeen, and a reduction of police divisions from ninety-two to thirty-four. This process abolished ninety-five police positions (forty-nine of them chief inspector or inspector positions), releasing those people for redeployment. In essence the entire profile of the Operations Department was altered: boundary, position, rank, office, code and staff configurations were all changed on a scale that was rare in the history of the force. It upset the lives of many police families: senior members with clear career paths and goals, many of them settled with their families in country locations, found their idyll shattered overnight by management decree.

Glare described the year as a ‘watershed’, and it was. Arbiter was a necessary and bold reform process that could have been better marketed and executed. The demoralisation generated by it was behind much of the organisational disquiet that concerned Glare. He acknowledged that command had ‘failed to communicate effectively’ and pledged to hire ‘a marketing consultant as a matter of urgency’. That the force needed to resort to a marketer to rectify internal problems created by management was itself a reflection of the ineptitude with which the change process was undertaken, and perhaps of some of those vested with its implementation. The force did learn from the pain of Arbiter Phase One; and subsequent phases of the restructure, which focused on other departments within the force, were managed and marketed more deftly. The reform process was, however, an ongoing one, made easier by the relative malleability of the force’s increasingly youthful workforce.14

A younger workforce also proved to be an asset as the force moved inexorably to adopt computerisation. In 1971 Mick Miller, who was then an assistant commissioner, had gone on patrol with the chief secretary, Rupert Hamer, accompanied by Maxwell Beggs, the officer-in-charge of the nascent Information Systems Division (ISD). With the assistance of Burroughs computers and the Communications Section (D.24), Beggs, who was described by his superiors as ‘highly intelligent’, demonstrated how stolen-car checks could be conducted in real time from a police vehicle. Over a four-week trial period during October and November 1971, the recovery of stolen cars increased by 241 per cent. As a result, the government approved the expenditure of $250 000 for the purchase of a computer and, in October 1973, a Computer Systems Division (CSD) under the command of Brevet Inspector Beggs was established within the Services Department. Tasked with developing a computer-based information system for the force, the work of Beggs and his small team came to fruition on 17 September 1975 when the premier of Victoria, Rupert Hamer, officially opened the Victoria Police Computer Centre.

The operating system implemented by the CSD was code-named PATROL, standing for ‘Police Access To Records On-Line’, and with its launch a new and enduring acronym entered the police lexicon. It provided police with rapid access to records of stolen and wanted motor vehicles through computer terminals installed in D.24, the Stolen Motor Vehicle Squad and the Motor Registration Branch. The response time for an inquiry was less than one second, and when it first went online PATROL generated a 350 per cent increase in inquiries over the manual system that had preceded it.

The evolution of computer systems within the force proceeded exponentially, culminating in the establishment of the Law Enforcement Assistance Program (LEAP) on 1 March 1993. A computer-based crime information system, LEAP was designed to process crime, traffic and patrol activity information. With its launch, elements of PATROL were integrated, providing improved community service and officer safety by supplying practical and timely information about crime, offenders, wanted persons, field contacts and stolen property. LEAP also offered comprehensive information to assist decision-making and resource management. Described by Superintendent Dave Smith of the LEAP Implementation Team as ‘a first for Australia’, it was promoted as a ‘dynamic’ or ‘smart’ computer-based crime information system, ‘designed with the needs of operational police as its first priority’.

Initially at the leading edge of such developments internationally, the base platform was still in use over twenty years later. Enhancements and updates were progressively made, and after a decade the force had computer access to more than three million names, the details of four million incidents, and the records of one million vehicles, three million locations, five million items of property and 70 000 offenders. Other more contemporary inclusions were 130 000 offender photographs, 720 000 photographs of firearms licence holders and a LEAP Forensic Identification Module to facilitate the management of fingerprint and DNA matches.

Despite such enhancements, the system in a number of material respects failed to keep pace with the rapidly changing world of information management and technology. It also suffered from misuse and mismanagement. In 1996 a review of LEAP was conducted by the Victorian auditor-general, and a subsequent high-level task force was established to address concerns about inappropriate use of the LEAP data system by Victoria Police employees. In 2005 the Office of Police Integrity (OPI) conducted an extensive investigation into the force’s management of LEAP and found that in addition to LEAP there were ‘at least 200 separate intelligence databases and a reported fifty different roster systems’. The OPI also proffered the view that it was ‘an opportunity for Victoria Police to wipe the slate clean’, and recommended ‘the replacement of LEAP with a Force-wide computer-based information system’. The then chief commissioner, Christine Nixon, conceded that ‘the technology surrounding LEAP was outdated’, but also pointed out that substantial funding was required to remedy that major failing and that it was ‘for the government to determine what would be appropriate to commit to the enhancement or replacement of LEAP’.15

It was during this era, too, that one of the most apparent developments within the organisation was the enhancement of the profile of women within the force. At one point the director of personnel, the media director and the assistant commissioner (internal investigations) were all female, while women filled a wide variety of other key and specialist positions. Bernice Masterson was the first female assistant commissioner in Australian police history, and her appointment in 1989 highlighted the new opportunities for policewomen. Some areas were slower to change than others: the proportion of women to men in country districts was 1:11 compared with 1:5 in the metropolitan area, and there were no women in the SOG or Dog Squad. In 1992 the force had the highest proportion of women—14.4 per cent—of any police service in Australia, and the Victorian rate was significantly higher than that of most forces in the UK and USA. Over 60 per cent of all non-police personnel (public servants) were female. Men, however, still dominated physically. One study found that only 33 per cent of female applicants passed the physical agility course compared with a rate of 88 per cent for men, and that both sexes preferred having a male partner during a violent confrontation.

The gender shift necessitated changes in procedure and philosophy. An Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Unit was formed and a broad range of EEO activities were initiated, including an evaluation of gender equality in the workforce, EEO training, the development of gender-neutral questions for force applicants, and a pilot study into the viability of positions for part-time police. It was also necessary to take action against a number of policemen for sexual harassment in the workplace, including physical harassment and lewd comments to female staff. A force-wide newsletter item warned: ‘Here’s a shock for some people—the days of patting backsides, sexist or crude remarks to trainees “in fun”, or jobs for the “boys” (or girls) are over’.16

Other shocks were in store for many police as unacceptable past practices and procedures were abandoned or changed. Drink-driving and alcohol-related road deaths involving police came under scrutiny when twenty-one police (twelve off-duty and nine on-duty) were killed in five years, prompting Chief Commissioner Glare to warn that ‘the days of badge-flashing’ were over. Between March 1988 and June 1990 thirty-eight police were charged with drink-driving offences, fourteen of them driving police vehicles. Assistant Commissioner (Traffic) Frank Green dryly noted: ‘Five were over 0.2; one refused a breath test; four of the top five readings were female; eleven were detectives (eight of them in police cars); and they were all ranks (recruit to inspector)’.

Police also fell prey to the much-maligned traffic cameras. From 1991 to 1993, 2157 police vehicles were caught speeding by traffic cameras. There was, however, a legislative exemption for police drivers in certain circumstances, and police seeking that exemption produced some of the most inventive excuses known to modern motoring. An alarming number of them were photographed while allegedly pursuing suspects of one sort or another, most of whom miraculously escaped detection by both the speeding police drivers and the traffic cameras. Some police did not even attempt to provide an explanation but arrogantly argued that they were entitled to speed because they were police. Few were fined or lost their licences: only 203 infringement notices were issued, amounting to less than 10 per cent of all police vehicles caught. This compared to a figure of 70 per cent for the rest of the community.

In 1991 the deputy commissioner (operations), John Frame, expressed concern at ‘the practice of police using their identification certificates to gain access to nightclubs and other venues’, reverting to an old police truism to warn that ‘there is no such thing as a free lunch’. There was general concern among the commissioners about police ethics, prompting Frame to observe: ‘There are signs that our standards, attitudes and professionalism are slipping’. He subsequently visited all police districts, giving a ‘coach’s address’ on professional standards, and in a homily that was apt for the times urged all members to ‘Remember that leadership and management are not necessarily the same’. The force also produced a booklet, Ethics and Professional Standards, and the code of ethics was required to be displayed prominently as a poster in police stations. Although there was concern about police ethics, the force drew some solace from the fact that of 3.5 million police–public contacts annually, there were only 1128 formal public complaints.17

Less than two decades earlier, the force had prided itself on being the ‘only organisation in society that will answer any call for help—anywhere, any time’. The ideal of community service was not then restricted by economic considerations. In a bid to balance the traditional notion of personal police attendance against the perceived need to manage the force along modern business lines, there was a significant rationalisation of ‘non-police’ duties, and fees were charged for many police services.

It was an era of paradox, when the force constantly emphasised the need for public support and turned increasingly to co-operative, community-based initiatives to combat crime while having to work with government policies driven by economic rationalism and fiscal constraint. The latter policies promoted a shift to impersonal policing, such as speed cameras, crime screening, user pays, corporate sponsorship and private-sector management models, which required sections of the force to operate competitively and on a commercial basis with private companies. At the same time, the force began to accept outside corporate sponsorship for such things as police computers and vehicles and to increase the dollar value of crimes screened from CIB attendance in recognition of resource problems. General calls for police service were also screened to assess ‘whether calls are being received which other government departments and organisations could handle more appropriately, for example wandering cows’.

Although Miller was the first commissioner to embrace community policing, his successor also saw the benefits in such strategies and, upon his return from a world tour in 1988, Glare embarked upon what he considered the ‘greatest achievement’ of his time as chief commissioner. During his overseas travels he had come across a number of ‘police in schools’ programmes, which in Victoria became known as the Police Schools Involvement Program, or PSIP; he ‘freely acknowledges that the original idea’ was not his. He succinctly described the object of the PSIP as ‘trying to have school children understand that they not only had rights but they also had corresponding obligations and responsibilities and that it was essential that they consider the consequences of their actions before doing something wrong rather than afterwards’.

Glare’s nascent scheme met with considerable resistance from the ranks, but by 1991 he had seventy-two school resource officers (SROs) servicing 720 schools. From these beginnings the PSIP successfully grew exponentially, and in 2004 the scheme was, for the first time in sixteen years, subjected to a commissioned review. In 2005 the PSIP numbered seventy-five SROs who reached about 5 per cent of the state’s total school population, and the review found that ‘modification of the original PSIP approach was timely’. Consequently the Youth Resource Officer Project was established by the force to ‘improve and refocus its school program and widen its reach to a range of young people’. The new model took into account the various ways police came into contact with young people, including ‘as victims, offenders, reporting crime, domestic violence and mental health issues’.

Years later, in his retirement, Glare suggested that one of his successors, Christine Nixon, had abolished the PSIP ‘as a matter of trying to control expenditure and because the program was not being well managed internally’, adding that both aspects were a commentary on ‘her inability to control and manage effectively and competently’. In a rapidly changing world, some observers might regard such comments as gratuitous, and the demise of the original PSIP as something to be expected in a police service seeking to keep in step with ever-changing community expectations and values.

Two related schemes that were also actively promoted by Glare were the establishment of Police Community Consultative Committees (PCCCs) and the development of ‘an integrated anti-crime strategy’ badged ‘VicSafe’. PCCCs were first developed in Victoria in 1991 with the aim of harnessing community resources to increase collective and personal safety. Members of PCCCs were drawn from a wide section of the community, including municipal councils, local businesses, Neighbourhood Watch groups, and residents. Similarly, VicSafe sought to consolidate anti-crime measures in a partnership model that embraced diverse business, community and government agencies. Like the PSIP, the PCCCs and VicSafe eventually wound down and were replaced by more contemporary community policing strategies and styles. However, the work of commissioners Miller and Glare in this regard left an enduring legacy that ensured that community policing remained a key element in the policing landscape.

The introduction of traffic cameras began in Victoria in 1982 with the installation of fixed red-light cameras. This was followed several years later with the first use of speed cameras in Australia. Introduced in March 1986, they were not extensively used until a statewide speed-camera programme was implemented in December 1989. By 1992 the camera systems were checking the speed of almost 20 million vehicles annually, resulting over a three-year period in the issue of 1 502 202 infringement notices totalling $130 million in fines. They also produced a decrease in the number of speeding vehicles and were a significant factor in reducing Victorian motor-vehicle collision injury levels to among the lowest in the world. Many motorists, nevertheless, were unhappy with the traffic cameras and their mode of operation—police sitting kerbside in unmarked cars fitted with cameras—particularly as infringement notices often arrived unexpectedly, weeks later, in the mail. So sensitive was the force to accusations that it was ‘revenue raising’ that even the police annual reports omitted the details of traffic camera revenue. Speed-camera duty was also disliked by many Traffic Operations Group members, who found the time spent sitting roadside operating the cameras to be ‘boring’ and ‘mechanical’. Specialists in such duties as highway patrol work, they missed the personal contact with drivers and felt that camera duty was a misuse of their time. During 1995 trials were conducted using civilian speed-camera operators, after which Assistant Commissioner (Traffic) Graham Sinclair announced, ‘during the trial there [were] fewer errors made during the loading and unloading of film by the new civilian unit’, adding that ‘while TOG members had previously performed their tasks with care, the civilian members had performed better’.18

The overseer of most of this change was Chief Commissioner Glare, who for much of his commissionership headed a force that was enigmatically progressive, respected and disenchanted. The stature of the force in police and government circles was such that four deputy commissioners, W. J. ‘Bill’ Horman, Noel Newnham, Bob Falconer and Mal Hyde were chosen respectively to head police departments in Tasmania, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia. Other Victorian officers were appointed to senior positions with the National Crime Authority, Queensland Criminal Justice Commission and Queensland Police Service. The recruitment of Victorian officers for senior executive positions interstate, particularly to post-Fitzgerald Queensland, was in part testament to the success of the push for systemic integrity by Miller and Glare. While other forces recruited some of his most talented officers, Glare battled locally with political obfuscation and fluctuating force morale. In his last Police Annual Report he wrote of the difficulty he experienced working in a ‘very turbulent operating environment, characterised by substantial funding constraints, increasing public accountability and the rapid pace of change’. A decade of working under Labor governments had left the force hamstrung operationally, and under-resourced. Whereas Miller, with his operational focus, was critical of inadequate enabling powers, Glare, with a more administrative focus, often expressed concern at the ongoing ‘erosion of the force’s resource base’. It was this erosion, coupled with economic rationalism, that led to the introduction of crime-screening and user-pays policies.19

Many of the force’s technological and management innovations, like speed cameras, produced positive benefits for the force and the community. There was, however, always an inherent danger that the ethos of community service might be lost in the mire of economic rationalism. The force, and the community it served, were yet to determine acceptable limits for a fiscal doctrine that saw the force shedding some of its traditional duties and responding to others on the basis of cost-effectiveness. In that regard the words of retired chief commissioner Miller have a timeless importance: ‘the reality is that the true measure of police effectiveness is qualitative not quantitative … We need to remember we are in the people business’.20

An indication of the malaise afflicting the force surfaced publicly in 1992 following the retirement of Chief Commissioner Glare, who officially left the service on 28 November. The Labor government led by Joan Kirner selected Deputy Commissioner John Frame to replace Glare as chief commissioner. Frame was an accomplished police administrator who had served as a staff officer and assistant commissioner under Miller and worked as an assistant and deputy commissioner under Glare. Despite lobbying by a number of groups, including the Age newspaper, for the appointment of an ‘outsider’ as chief commissioner, Frame was generally expected to get the job. Politics interposed, however, and the Kirner Government was voted from office on 3 October 1992 before the selection of Frame as chief commissioner became effective. The new conservative government, led by Jeffrey Kennett, and the minister responsible for police, Patrick McNamara, started the chief commissioner selection process afresh. After weeks of advertising and searching, with Frame acting as chief commissioner, the Kennett Government announced the surprise selection of Queensland assistant commissioner Murray Neil Comrie. It was generally touted within the force that Frame’s principal disqualifying factor was his previous selection by the Kirner Government. However, the Kennett Government had amended the Police Regulation Act to establish an independent police board ‘to advise the Minister and the Chief Commissioner principally upon ways in which the administration of the Police Force might be improved’. Frame reportedly indicated a disinclination to work with such a board. Comrie had no such reservations and was the police member on the board when it met for the first time on 7 January 1993.

In a startling dénouement, Assistant Commissioner (Internal Investigations) Bernice Masterson publicly criticised the selection of Comrie as chief commissioner, describing it as ‘a dreadful mistake’. Masterson had earlier been ‘outed’ in the media as being a lesbian and had received ‘instant and unequivocal support’ from Frame. She resigned shortly after Comrie’s appointment and did not serve under him. That the one commissioner personally responsible for police discipline could make such an undisciplined outburst was seen by many as evidence that some aspects of the force’s senior administration were sadly awry. Frame retired on 2 January 1993 and was followed some weeks later by Jean Gordon, the force’s first civilian director of personnel and the first woman to have held such a position in the force.

The unexpected announcement of Comrie’s appointment was clouded in controversy, including constant references to him being an ‘outsider’. Such criticisms were without foundation: Comrie was the third generation of his family to serve in the force. His grandfather, Angus Comrie, served from 1899 to 1934, and his father, Murray Comrie, served from 1934 to 1972. (His son, Heath Comrie, joined the force in 2001.)

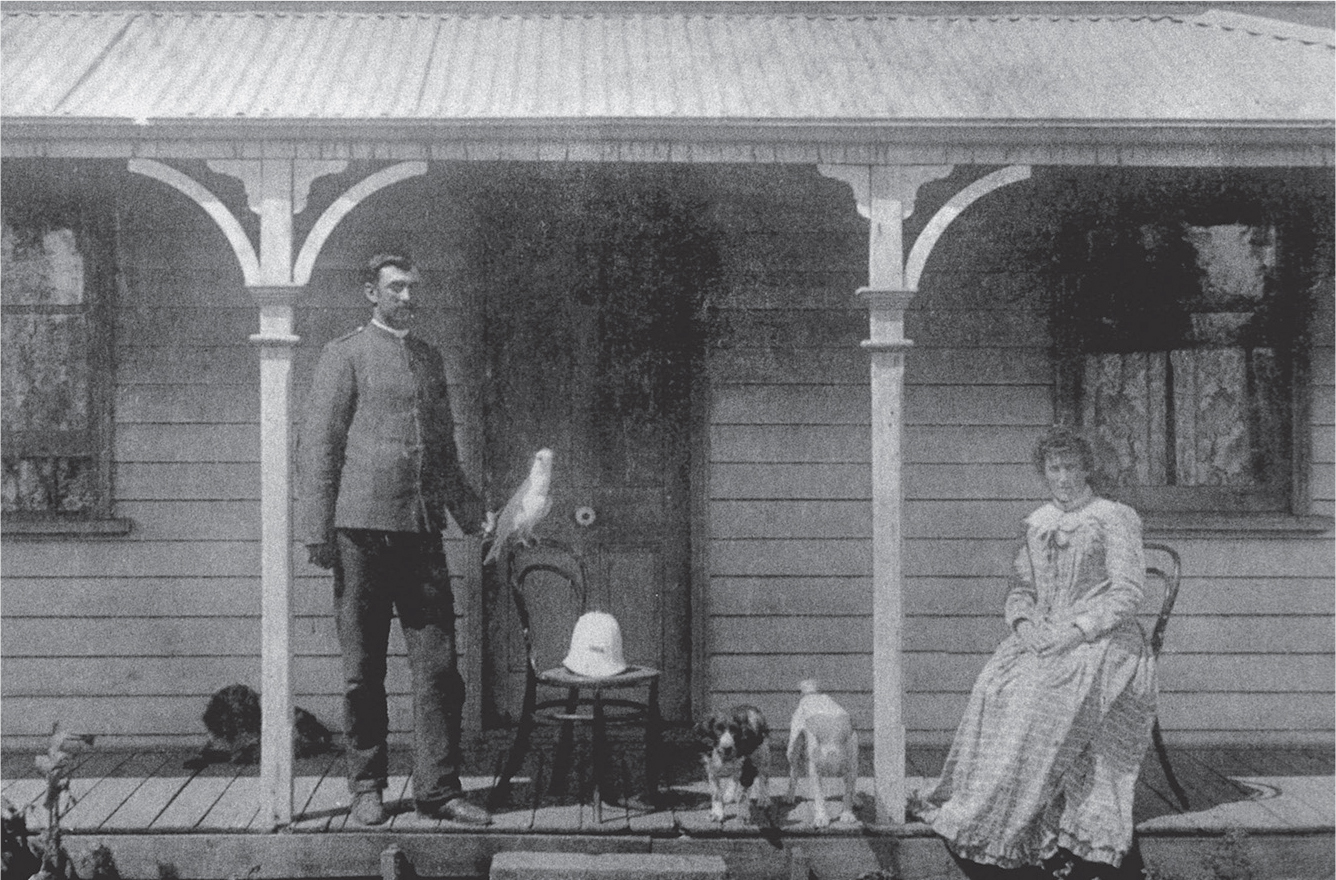

Angus Malcolm Comrie and Mary Ellen Comrie, grandparents of Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie at the Murtoa police station, 1900

Chief Commissioner N. M. Comrie

Neil Comrie commenced his police career in 1967 and worked in a variety of positions in the operations, traffic, crime, research and vice areas over a period of twenty-three years before resigning at the rank of superintendent to move to Queensland. He had a strong operational and investigative background and was noted in Victoria for his work in the suppression of child sexual exploitation, particularly when he headed the Delta Task Force. In Queensland, Comrie was part of the post-Fitzgerald Inquiry reformation. He held the position of assistant commissioner (task force command) and also acted as commissioner and deputy commissioner.21

Comrie took up his appointment as chief commissioner on 4 January 1993 on a five-year contract that included performance requirements and provision for a performance bonus. He was unhappy about the bonus clause, and it was later removed at his request. He was also made a member of the State Coordination and Management Council (SCMC). Chaired by the secretary of the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, it included all eight government department heads and the public service commissioner. The Kennett Government was elected at a time of severe financial crisis. Having undertaken to restore the state’s AAA credit rating, Kennett introduced a wide range of efficiency and cost-cutting measures across all government sectors. Referred to as ‘efficiency dividends’, these cuts comprised around 3 per cent of the force’s annual budget. In a competitive process with other Department of Justice business units, the force was required to bid for funding before the government’s Budget Expenditure Review Committee.

Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie with students from the Belfield Primary School, West Ivanhoe

In many respects it was a new frontier for the force. At the time of his appointment, Comrie expressed concern about the efficacy of the discipline system and was of the view that the police service and discipline boards ‘usurped the authority of the chief commissioner’. He felt that this system restricted his capacity to maintain the integrity of the force. And despite vigorous opposition from the Police Association, he sought and achieved major amendments to the Police Regulation Act, resulting in the removal of both boards in favour of a new discipline system based on administrative rather than criminal law.

In what Comrie described as ‘a major cultural change’, the Police Regulation (Discipline) Act came into effect in August 1993. At the time Comrie noted: ‘the force is now able to deal with internal discipline problems in a manner which is more satisfactory for members and the public we serve. Like other professional organisations, the Force will now be able to deal with its own disciplinary matters, but with an independent review process’. With an emphasis on personal development rather than punishment, the system provided a number of levels for disciplinary action, starting with a base level of counselling, and rising through cautioning and admonishments to charges. The most controversial provisions were those giving the chief commissioner or his delegate the power to dismiss members and to exclude lawyers during matters before the hearing officer. Provision was made in the Act for the Police Discipline Board and the Police Service Board to continue to exist until all matters before them were finalised; the Service Board concluded its last appeal matter on 15 March 1995. The new Police Review Commission was headed by John Giuliano, with two deputies. A former member of the Police Service Board, Giuliano had also worked with the Public Service Appeals Tribunal. The dire prophecies of the Police Association did not come to pass, and in time Chief Commissioner Comrie considered it ‘worthy of note, that in the five years prior to my appointment not one member was dismissed from the Force. In the first five years after my appointment eighty-five were dismissed’.

Another far-reaching change forming part of the Kennett Government’s reform package took place on 10 November 1996, when the government shifted its industrial relations powers to the Commonwealth. Creating a single industrial relations system for Victoria, this decision, taken pursuant to the Commonwealth Powers (Industrial Relations) Act 1996, rendered obsolete the role of the Police Service Board in determining police salaries and working conditions. Supplanting the board with a system of enterprise bargaining, it effectively made the chief commissioner the ‘employer’ and required him to negotiate directly with the Victoria Police Association over salaries and working conditions. It was a move that introduced a level of estrangement between the police union and the chief commissioner that hitherto had been absent from their relationship, and it worsened over time, fostering levels of acrimony and police militancy not seen since the mass rally to protest the findings of the Beach Inquiry at Festival Hall on 18 October 1976.

While Comrie initially had ‘a positive working relationship with the Police Association, occasionally going toe-to-toe with its secretary Danny Walsh’, that relationship deteriorated. The displacement of Walsh by Paul Mullett as secretary in 2001 ‘led to a serious decline in the relationship between Force Command and the Association, culminating in the resignation of all members of police command from the Association’. The enmity that existed between Comrie and Mullett was palpable, and no one, including the police minister, seemed capable of brokering a truce.

It was a time when 94 per cent of the force budget was committed to staff salaries and related flow-on costs, and Comrie had very little discretionary funding in areas such as computers and new technology. Although the Kennett Government eviscerated the public sector and fifteen thousand public servants lost their jobs, the police force was spared much of this political savagery and Comrie was left to joust with the Police Association over wages and work conditions. In one reportedly myopic moment Mullett is said to have quipped: ‘Computers don’t lock up crooks, police do’. The police union mantra across the decades had largely constituted a perennial push for increased police numbers, much to the detriment of spending on critical support technology such as computers, radio networks, and forensic and other technological resources. Comrie was dismayed at the inefficient stand-alone data management system he had inherited, which was costly to maintain and totally inadequate for a modern police service.

The Kennett Government push for increased financial accountability and its concomitant emphasis on human resource management and technological change signalled clearly to Comrie that the days of omnipotent ‘gifted amateurs’ in the higher echelons of the organisation were fast drawing to a close. It had been accepted practice for almost 150 years for all senior positions in the force to be filled by police, who frequently lacked any tertiary qualifications or particular expertise in the portfolios that they filled. Typical of this conservative cadre was Deputy Commissioner Graham Sinclair, who was known to boast that his formal education had ended in ‘Year 10 at Box Hill Tech’. They were respected and adroit investigators of the ‘old school’, who lacked the benefits of higher education and specialist management skills. In stark contrast and representative of the ‘new breed’ was Deputy Commissioner Mal Hyde. A qualified lawyer with an MBA from the University of Melbourne, he left the force in 1997 to take up the position of commissioner of police in South Australia.

Based on his Queensland experience and subsequent return to Victoria, Comrie formed a view that ‘many senior officers had little experience outside of the Victoria Police and were therefore quite introspective and lacked the capacity to be innovative and flexible’. In a bid to counter this insularity, Comrie implemented an exchange program with the Strathclyde Police in Scotland and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Noel Ashby was the first Victorian to go to Strathclyde, and Peter Nancarrow went to Canada. Comrie also provided the opportunity for members of command ‘to travel overseas and undertake a study tour of appropriate forces to examine contemporary policing techniques and strategies’.

To meet the significant changes and challenges wrought largely by the Kennett Government, especially in the portfolios of financial management, technological change and human resource management, Comrie appointed three senior public servants to his command team. In April 1997 Ken Latta, MBA, who had an extensive background in the TAFE sector, was the first civilian appointed at deputy commissioner level to executive command, as director (corporate services). Two earlier appointments equivalent to assistant commissioner level were Geoff Cliffe and Peter Breadmore. Cliffe had an MBA and was a clinical psychologist, and his diverse career background included working on the Very Fast Train project; he was appointed director of corporate resources in 1994. Peter Breadmore was appointed director of personnel in May 1993. A former pentathlete, parachutist, mountain climber and Arctic expedition leader, his eclectic background included tertiary studies in education, service in the British Army, and extensive service in the public sector in Victoria.22

Much of Comrie’s initial focus was the politically driven ‘new managerialism’ of the Kennett Government. During the first two years of his commissionership he was also compelled to deal with the fallout from a spate of operational crises that embroiled the force in intense public criticism and debate.

The first of these was a public order incident on 13 December 1993 that saw police involved in a baton charge at the former Richmond Secondary College site. As part of the government’s educational restructuring programme, it decided to close the Richmond Secondary College and establish the new Melbourne Girls’ College on the site. This proposal was opposed by a number of interested parties, notably the Friends of Richmond Secondary College Occupation Committee, which enrolled students for the 1993 school year and proposed using volunteer teachers to run the school. In a non-violent protest, the committee illegally occupied the college premises for 360 days between 13 December 1992 and 7 December 1993, when the sheriff, without the use of force, evicted the occupiers and secured the building.

Throughout the occupation local police had provided a low-key police presence and had a cordial working relationship with the protesters. Following their eviction on 7 December, the demonstrators established a tent campsite in close proximity to the work site and the police presence was increased significantly, including the deployment of the newly formed Force Response Unit (FRU) and the Protective Security Group (PSG).

When the school site was cleared of protesters, the Department of School Education moved to accelerate work on the project and a police operation was planned to provide contractors with secure access to their workplace. On the morning of Monday 13 December 1993, police tried unsuccessfully to negotiate with the picketers in a bid to facilitate unhindered site access for contractors and tradespeople. Picketers were warned that they would be removed by force and charged with besetting premises if they did not comply. When that warning went unheeded and violence was looming, police, in accordance with their operation order, implemented a ‘level four’ operation and with the use of batons cleared picketers from the entrance. Police brandishing long batons and aggressively chanting ‘move’ in unison struck protesters about the head and body. They later explained that their tactics were a response to earlier demonstrations where, unprepared for violence, police had been injured in the fray. After reviewing those earlier demonstrations, police tactics had been changed and specialist units had been formed to deal with the threats posed by such events.

In the days following this operation, numerous members of the public complained to Dr Barry Perry, the deputy ombudsman dealing with police complaints, that the level of force used by police was ‘disproportionate to the action that was being taken by the demonstrators’. After a lengthy investigation Perry found that police had used ‘unreasonable actions and excessive force’ and recommended that the force adopt ‘a formal risk management process to identify, evaluate and control risks in light of the objectives to be achieved’.

The police field commander at Richmond later said that he was ‘unaware of Victoria Police ever drawing long batons and advancing as they did’, and the senior sergeant responsible for FRU tactical training explained that the militaristic tactics used at the school site ‘had never been used before in Victoria’.

It wasn’t long after this incident that another ‘first’ in Victorian police tactics aroused the ire of many Victorians and the interest of Dr Perry. On 10 February 1994, anti-logging protesters blockading the offices of the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources in Victoria Parade, East Melbourne were moved by police using ‘pain compliance pressure point control techniques’.

Seventy demonstrators with their arms linked formed a single line across the front of the building, blocking both pedestrian and vehicular access. Police equipped with long batons established a single cordon between the building and the line of demonstrators. Initially, police removed demonstrators from the driveway using the generally accepted ‘lift and carry’ method, but this proved ineffective when demonstrators repeatedly moved back into the blockade and elected to sit on the driveway. As a result, members of the PSG, wearing fatigues and surgical gloves, forcibly removed demonstrators by using pain compliance techniques. Demonstrators claimed that this involved the ‘rotating of arms, wrists and fingers against the normal direction of movement, applying pressure to nerve points to the side of the neck, nose and cranium; eyes were gouged, and ears and hair pulled, all causing considerable pain’.