I can't understand why some people see Bourne shell quoting as a scary, mysterious set of many rules. Quoting on Bourne-type shells is simple. (C shell quoting is slightly more complicated. See Section 27.13.)

The overall idea is this:

quoting turns off (disables) the special meaning of

characters. There are three quoting characters: single quote

('), double quote ("), and backslash (\). Note that a backquote (`)

is not a quoting character — it does command substitution (

Section 28.14).

Listed below are the characters that are special to the Bourne shell. You've probably already used some of them. Quoting these characters turns off their special meaning. (Yes, the last three characters are quoting characters. You can quote quoting characters; more on that later.)

# & * ? [ ] ( ) = | ^ ; < > ` $ " ' \

Space,

tab, and newline also have special

meaning as argument separators. A slash (/) has special meaning to Unix itself, but not

to the shell, so quoting doesn't change the meaning of slashes.

Newer shells have a few other special characters. For instance, bash has !

for history

substitution (Section

30.8). It's similar to the C shell

! (Section 27.13)

except that, in bash, ! loses its special meaning inside single

quotes. To find particular differences in your Bourne-type shell, see the

quoting section of its manual page. In general, though, the rules below

apply to all Bourne-type shells.

Table 27-1 summarizes the rules; you might want to look back at it while you read the examples.

Table 27-1. Bourne shell quoting characters

|

Quoting character |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

' |

Disable all special characters in

|

|

" |

Disable all special characters in

|

|

\ |

Disable the special meaning of character

|

To understand which characters will be quoted, imagine this: the Bourne shell reads what you type at a prompt, or the lines in a shell script, character by character from first to last. (It's actually more complicated than that, but not for the purposes of quoting.)

When the shell reads one of the three quoting characters, it does the following:

Strips away that quoting character

Turns off (disables) the special meaning of some or all other character(s) until the end of the quoted section, by the rules in Table 27-1

You also need to know how many characters will be quoted. The next few sections have examples to demonstrate those rules. Try typing the examples at a Bourne shell prompt, if you'd like. (Don't use C shell; it's different (Section 27.13).) If you need to start a Bourne-type shell, type sh; type exit when you're done.

A backslash (

\) turns off the special meaning (if any) of the next character. For example,\*is a literal asterisk, not a filename wildcard (Section 1.13). So, the first expr (Section 36.21) command gets the three arguments79 * 45and multiplies those two numbers:$

expr 79 \* 453555 $expr 79 * 45expr: syntax errorIn the second example, without the backslash, the shell expanded

*into a list of filenames — which confused expr. (If you want to see what I mean, repeat those two examples using echo (Section 27.5) instead of expr.)A single quote (

') turns off the special meaning of all characters until the next single quote is found. So, in the command line below, the words between the two single quotes are quoted. The quotes themselves are removed by the shell. Although this mess is probably not what you want, it's a good demonstration of what quoting does:$

echo Hey! What's next? Mike's #1 friend has $$.Hey! Whats next? MikesLet's take a close look at what happened. Spaces outside the quotes are treated as argument separators; the shell ignores the multiple spaces. echo prints a single space between each argument it gets. Spaces inside the quotes are passed on to echo literally. The question mark (

?) is quoted; it's given to echo as is, not used as a wildcard.So, echo printed its first argument

Hey!and a single space. The second argument to echo isWhats next? Mikes; it's all a single argument because the single quotes surrounded the spaces (notice that echo prints the two spaces after the question mark:?). The next argument,#1, starts with a hash mark, which is a comment character (Section 35.1). That means the shell will ignore the rest of the string; it isn't passed to echo.(zsh users: The

#isn't treated as a comment character at a shell prompt unless you've runsetopt interactive_commentsfirst.)Double quotes (") work almost like single quotes. The difference is that double quoting allows the characters

$(dollar sign),'(backquote), and\(backslash) to keep their special meanings. That lets you do variable substitution ( Section 35.9, Section 35.3) and command substitution ( Section 28.14) inside double quotes — and also stop that substitution where you need to.For now, let's repeat the example above. This time, put double quotes around the single quotes (actually, around the whole string):

$

echo "Hey! What's next? Mike's #1 friend has $$."Hey! What's next? Mike's #1 friend has 18437.The opening double quote isn't matched until the end of the string. So, all the spaces between the double quotes lose their special meaning, and the shell passes the whole string to echo as one argument. The single quotes also lose their special meaning because double quotes turn off the special meaning of single quotes! Thus, the single quotes aren't stripped off as they were in the previous example; echo prints them.

What else lost its special meaning? The hash mark (

#) did; notice that the rest of the string was passed to echo this time because it wasn't "commented out." But the dollar sign ($) didn't lose its meaning; the$$was expanded into the shell's process ID number (Section 24.3) (in this shell,18437).

In the previous example, what would happen if you put the $ inside the single quotes? (Single quotes

turn off the meaning of $, remember.)

Would the shell still expand $$ to its

value? Yes, it would: the single quotes have lost their special meaning, so

they don't affect any characters between them:

$ echo "What's next? How many $$ did Mike's friend bring?"

What's next? How many 18437 did Mike's friend bring?How can you make both the $$ and the

single quotes print literally? The easiest way is with a backslash, which

still works inside double quotes:

$ echo "What's next? How many \$\$ did Mike's friend bring?"

What's next? How many $$ did Mike's friend bring?Here's another way to solve the problem. A careful look at this will show a lot about shell quoting:

$ echo "What's next? How many "'$$'" did Mike's friend bring?"

What's next? How many $$ did Mike's friend bring?To read that example, remember that a double quote quotes characters until

the next double quote is found. The same is true for single quotes. So, the

string What's next? How many (including

the space at the end) is inside a pair of double quotes. The $$ is inside a pair of single quotes. The rest

of the line is inside another pair of double quotes. Both of the

double-quoted strings contain a single quote; the double quotes turn off its

special meaning and the single quote is printed literally.

You can't put single quotes inside single quotes. A single quote turns off all special meaning until the next single quote. Use double quotes and backslashes.

Once you type a single quote or double quote, everything is quoted. The quoting can stretch across many lines. (The C shell doesn't work this way.)

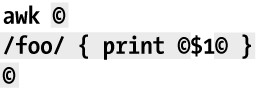

For example, in the short script shown in Figure 27-1, you might think that the

$1 is inside quotes, but it

isn't.

Actually, all argument text except

$1 is in quotes. The gray shaded area

shows the quoted parts. So $1 is expanded

by the Bourne shell, not by awk.

Here's another example. Let's store a shell

variable (

Section 35.9) with a multiline

message, the kind that might be used in a shell program. A shell variable

must be stored as a single argument; any argument separators (spaces, etc.)

must be quoted. Inside double quotes, $

and ' are interpreted

(before the variable is stored, by the way). The

opening double quote isn't closed by the end of the first line; the Bourne

shell

prints secondary prompts (Section 28.12) (>) until

all quotes are closed:

$greeting="Hi, $USER.> The date and time now> are: `date`."$echo "$greeting"Hi, jerry. The date and time now are: Fri Sep 1 13:48:12 EDT 2000. $echo $greetingHi, jerry. The date and time now are: Fri Sep 1 13:48:12 EDT 2000. $

The first echo command line uses double

quotes, so the shell variable is expanded, but the shell doesn't use the

spaces and newlines in the variable as argument separators. (Look at the

extra spaces after the word are:.) The

second echo doesn't use double quotes.

The spaces and newlines are treated as argument separators; the shell passes

14 arguments to echo, which prints them

with single spaces between.

A backslash has a quirk you

should know about. If you use it outside quotes, at the end of a line (just

before the newline), the newline will be deleted.

Inside single quotes, though, a backslash at the end of a line is copied as

is. Here are examples. I've numbered the prompts (1$, 2$, and so on):

1$echo "a long long long long long long>line or two"a long long long long long long line or two 2$echo a long long long long long long\>linea long long long long long longline 3$echo a long long long long long long \>linea long long long long long long line 4$echo "a long long long long long long\>line"a long long long long long longline 5$echo 'a long long long long long long\>line'a long long long long long long\ line

You've seen an example like example 1 before. The newline is in quotes, so

it isn't an argument separator; echo

prints it with the rest of the (single, two-line) argument. In example 2,

the backslash before the newline tells the shell to delete the newline; the

words long and line are passed to echo as

one argument. Example 3 is usually what you want when you're typing long

lists of command-line arguments: Type a space (an argument separator) before

the backslash and newline. In example 4, the backslash inside the double

quotes is ignored (compare to example 1). Inside single quotes, as in

example 5, the backslash has no special meaning; it's passed on to

echo.

— JP