3

WHAT IS CONSCIOUSNESS GOOD FOR?

Why did consciousness evolve? Can some operations be carried out only by a conscious mind? Or is consciousness a mere epiphenomenon, a useless or even illusory feature of our biological makeup? In fact, consciousness supports a number of specific operations that cannot unfold unconsciously. Subliminal information is evanescent, but conscious information is stable—we can hang on to it for as long as we wish. Consciousness also compresses the incoming information, reducing an immense stream of sense data to a small set of carefully selected bite-size symbols. The sampled information can then be routed to another processing stage, allowing us to perform carefully controlled chains of operations, much like a serial computer. This broadcasting function of consciousness is essential. In humans, it is greatly enhanced by language, which lets us distribute our conscious thoughts across the social network.

The particulars of the distribution of consciousness, so far as we know them, point to its being efficacious.

—William James, Principles of Psychology (1890)

In the history of biology, few questions have been debated as heatedly as finalism or teleology—whether it is meaningful to speak of organs as designed or evolved “for” a specific function (a “final cause,” or telos in Greek). In the pre-Darwinian era, finalism was the norm, as the hand of God was seen as a hidden designer of all things. The great French anatomist Georges Cuvier constantly appealed to teleology when interpreting the functions of the body organs: claws were “for” catching prey, lungs were “for” breathing, and such final causes were the very conditions of existence of the organism as an integrated whole.

Charles Darwin radically altered the picture by pointing to natural selection, rather than design, as an undirected force blindly shaping the biosphere. The Darwinian view of nature has no need for divine intention. Evolved organs are not designed “for” their function; they merely grant their possessor a reproductive advantage. In a dramatic reversal of perspective, antievolutionists seized as counterexamples to Darwin what they viewed as obvious examples of nonadvantageous designs. Why does the peacock carry a huge, visually stunning, but clumsy tail? Why did Megaloceros, the extinct Irish elk, carry a gigantic pair of antlers, spanning up to twelve feet, so bulky that it has been blamed for the species’ demise? Darwin retorted by pointing to sexual selection: it is advantageous for males, who compete for female attention, to develop elaborate, costly, and symmetrical displays advertising their fitness. The lesson was clear: biological organs did not come labeled with a function, and even clumsy contraptions, tinkered with by evolution, could bring a competitive edge to their possessors.

During the twentieth century, the synthetic theory of evolution further dissolved the teleological picture. The modern vocabulary of evolution and development (evo-devo) now includes an extended toolkit of concepts that collectively account for sophisticated design without a designer:

- Spontaneous pattern generation: The mathematician Alan Turing first described how chemical reactions may lead to the emergence of organized features such as the zebra’s stripes or the melon’s ribs.1 On some cone shells, sophisticated pigmentation patterns self-organize under an opaque layer, clearly proving their lack of intrinsic utility—they are a mere offshoot of chemical reactions with their own raison d’être.

- Allometric relations: An increase in the overall size of the organism (which may be advantageous in its own right) may lead to a proportionate change in some of its organs (which may not). The Irish elk’s outlandish antlers probably resulted from such an allometric change.2

- Spandrels: The late Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould coined this term to refer to features of the organism that arise as necessary by-products of its architecture but that might later be co-opted (or “exapted”) into another role.3 An example may be the male nipple—an inconsequential but necessary outcome of the organism’s Bauplan for constructing advantageous female breasts.

Bearing these biological concepts in mind, we can no longer assume that any human biological or psychological trait, including consciousness, necessarily plays a positive functional role in our species’ worldwide success. Consciousness could be a happenstance decorative pattern, or the chance outcome of a massive increase in brain size that occurred in our species of the genus Homo, or even a mere spandrel, a consequence of other vital changes. This view matches the intuition of the French writer Alexandre Vialatte, who whimsically stated that “consciousness, like the appendix, serves no role but to make us sick.” In the 1999 movie Being John Malkovich, the puppeteer Craig Schwartz laments the inutility of introspection: “Consciousness is a terrible curse. I think. I feel. I suffer. And all I ask in return is the opportunity to do my work.”

Is consciousness a mere epiphenomenon? Should it be likened to the loud roar of a jet engine—a useless and painful but unavoidable consequence of the brain’s machinery, inescapably arising from its construction? The British psychologist Max Velmans clearly leans toward this pessimistic conclusion. An impressive array of cognitive functions, he argues, are indifferent to awareness—we may be aware of them, but they would continue to run equally well if we were mere zombies.4 The popular Danish science writer Tor Nørretranders coined the term “user illusion” to refer to our feeling of being in control, which may well be fallacious; every one of our decisions, he believes, stems from unconscious sources.5 Many other psychologists agree: consciousness is the proverbial backseat driver, a useless observer of actions that forever lie beyond its control.6

In this book, however, I explore a different road—what philosophers call the “functionalist” view of consciousness. Its thesis is that consciousness is useful. Conscious perception transforms incoming information into an internal code that allows it to be processed in unique ways. Consciousness is an elaborate functional property and as such is likely to have been selected, across millions of years of Darwinian evolution, because it fulfills a particular operational role.

Can we determine what that role is? We cannot rewind evolutionary history, but we can use the minimal contrast between seen and unseen images to characterize the uniqueness of conscious operations. Using psychological experiments, we can probe which operations are feasible without consciousness, and which are uniquely deployed when we report awareness. This chapter will show that, far from blacklisting consciousness as a useless feature, these experiments point to consciousness as being highly efficacious.

Unconscious Statistics, Conscious Sampling

My picture of consciousness implies a natural division of labor. In the basement, an army of unconscious workers does the exhausting work, sifting through piles of data. Meanwhile, at the top, a select board of executives, examining only a brief of the situation, slowly makes conscious decisions.

Chapter 2 laid out the powers of our unconscious mind. A great variety of cognitive operations, from perception to language understanding, decision, action, evaluation, and inhibition can unfold, at least partially, in a subliminal mode. Below the conscious stage, myriad unconscious processors, operating in parallel, constantly strive to extract the most detailed and complete interpretation of our environment. They operate as nearly optimal statisticians who exploit every slightest perceptual hint—a faint movement, a shadow, a splotch of light—to calculate the probability that a given property holds true in the outside world. Much as the weather bureau combines dozens of meteorological observations to infer the chance of rain in the next few days, our unconscious perception uses incoming sense data to compute the probability that colors, shapes, animals, or people are present in our surroundings. Our consciousness, on the other hand, offers us only a glimpse of this probabilistic universe—what statisticians call a “sample” from this unconscious distribution. It cuts through all ambiguities and achieves a simplified view, a summary of the best current interpretation of the world, which can then be passed on to our decision-making system.

This division of labor, between an army of unconscious statisticians and a single conscious decision maker, may impose itself on any moving organism by that organism’s very necessity of acting upon the world. No one can act on mere probabilities—at some point, a dictatorial process is needed to collapse all uncertainties and decide. Alea jacta est: “the die is cast,” as Caesar famously said after crossing the Rubicon to seize Rome from the hands of Pompey. Any voluntary action requires tipping the scales to a point of no return. Consciousness may be the brain’s scale-tipping device—collapsing all unconscious probabilities into a single conscious sample, so that we can move on to further decisions.

The classical fable of Buridan’s ass hints at the usefulness of quickly breaking through complex decisions. In this imaginary tale, a donkey that is thirsty and hungry is placed exactly midway between a pail of water and a stack of hay. Unable to decide between them, the fabled animal dies of both hunger and thirst. The problem seems ridiculous, yet we are constantly confronted with difficult decisions of a similar kind: the world offers us only unlabeled opportunities with uncertain, probabilistic outcomes. Consciousness resolves the issue by bringing to our attention, at any given time, only one out of the thousands of possible interpretations of the incoming world.

The philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, following in the footsteps of the physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, was among the first to recognize that even our simplest conscious observation results from a bewildering complexity of unconscious probabilistic inferences:

Looking out my window this lovely spring morning I see an azalea in full bloom. No, no! I do not see that; though that is the only way I can describe what I see. That is a proposition, a sentence, a fact; but what I perceive is not proposition, sentence, fact, but only an image, which I make intelligible in part by means of a statement of fact. This statement is abstract; but what I see is concrete. I perform an abduction when I so much as express in a sentence anything I see. The truth is that the whole fabric of our knowledge is one matted felt of pure hypothesis confirmed and refined by induction. Not the smallest advance can be made in knowledge beyond the stage of vacant staring, without making an abduction at every step.7

What Peirce called “abduction” is what a modern cognitive scientist would dub “Bayesian inference,” after the Reverend Thomas Bayes (ca. 1701–61), who first explored this domain of mathematics. Bayesian inference consists in using statistical reasoning in a backward manner to infer the hidden causes behind our observations. In classical probability theory, we are typically told what happens (for instance, “someone draws three cards from a deck of fifty-two”); the theory allows us to assign probabilities to specific outcomes (for instance, “What is the probability that all three cards are aces?”). Bayesian theory, however, lets us reason in the converse direction, from outcomes to their unknown origins (for instance, “If someone draws three aces from a deck of fifty-two cards, what is the likelihood that the deck was rigged and comprised more than four aces?”). This is called “reverse inference” or “Bayesian statistics.” The hypothesis that the brain acts as a Bayesian statistician is one of the hottest and most debated areas of contemporary neuroscience.

Our brain must perform a kind of reverse inference because all our sensations are ambiguous: many remote objects could have caused them. When I manipulate a plate, for instance, its rim appears to be a perfect circle, but it actually projects on my retina as a distorted ellipse, compatible with myriad other interpretations. Infinitely many potato-shaped objects, of countless orientations in space, could have cast the same projection onto my retina. If I see a circle, it is only because my visual brain, unconsciously pondering the endless possible causes for this sensory input, opts for “circle” as the most probable. Thus, although my perception of the plate as a circle seems immediate, it actually arises from a complex inference that weeds out an inconceivably vast array of other explanations for that particular sensation.

Neuroscience offers much evidence that during the intermediate visual stages, the brain ponders a vast number of alternative interpretations for its sensory inputs. A single neuron, for instance, may perceive only a small segment of an ellipse’s overall contour. This information is compatible with a broad variety of shapes and motion patterns. Once visual neurons start talking to one another, however, casting their “votes” for the best percept, the entire population of neurons can converge. When you have eliminated the impossible, Sherlock Holmes famously stated, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

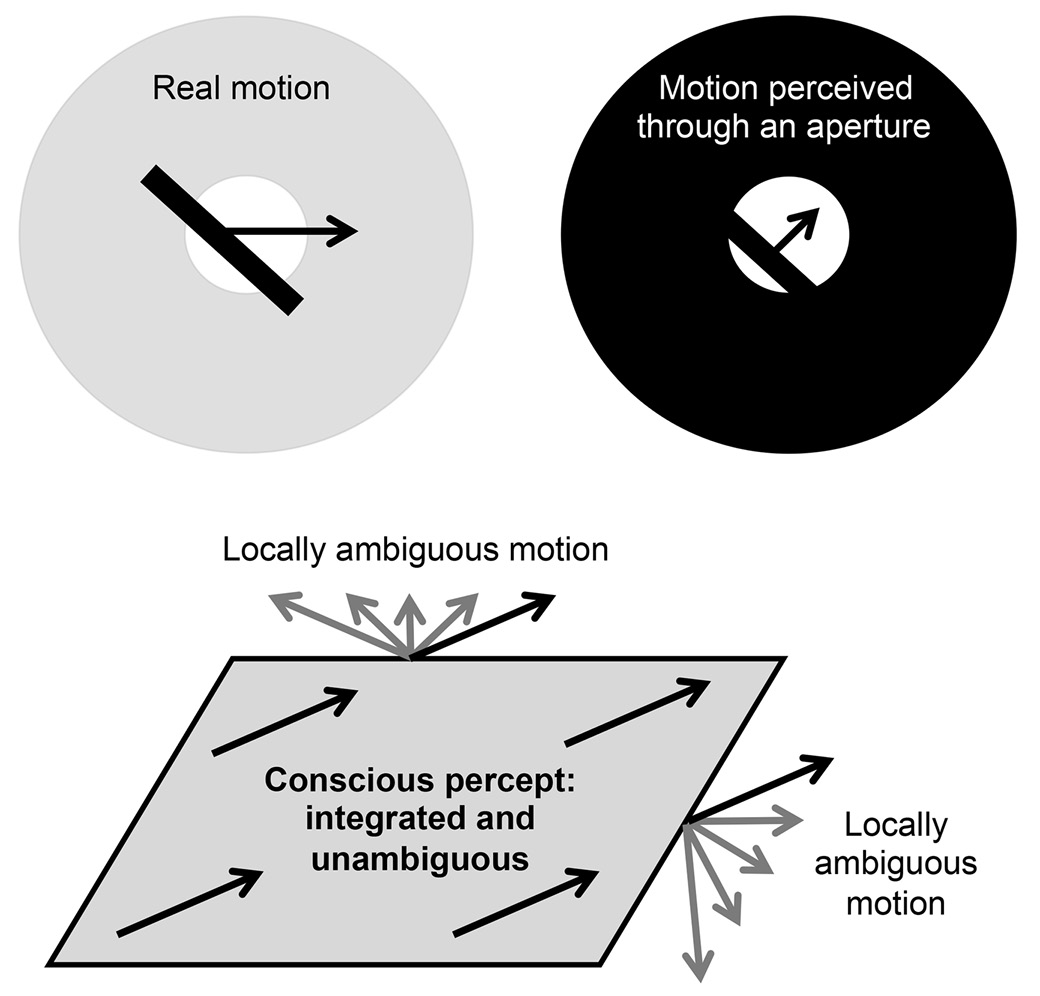

A strict logic governs the brain’s unconscious circuits—they appear ideally organized to perform statistically accurate inferences concerning our sensory inputs. In the middle temporal motion area MT (“area MT”), for instance, neurons perceive the motion of objects only through a narrow peephole (the “receptive field”). At that scale, any motion is ambiguous. If you watch a stick through a peephole, you cannot accurately determine its motion. It could be moving in the direction perpendicular to itself or in countless other directions (figure 14). This basic ambiguity is known as the “aperture problem.” Unconsciously, individual neurons in our area MT suffer from it—but at a conscious level, we don’t. Even under dire circumstances, we perceive no ambiguity. Our brain makes a decision and lets us see what it considers to be the most likely interpretation, with the minimal amount of motion: the stick always appears to move in the direction perpendicular to itself. An unconscious army of neurons evaluates all the possibilities, but consciousness receives only a stripped-down report.

FIGURE 14. Consciousness helps resolve ambiguities. In the region of the cortex that is sensitive to motion, neurons suffer from the “aperture problem.” Each of them receives inputs from only a limited aperture, classically called the “receptive field,” and thus cannot tell whether the motion is oriented horizontally, perpendicular to the bar, or in any of countless other directions. In our conscious awareness, however, no ambiguity exists: our perceptual system makes a decision and always lets us see the minimal amount of motion, perpendicular to the line. When an entire surface is moving, we perceive the global direction of movement by combining the signals from multiple neurons. Neurons in area MT initially encode each local motion, but they quickly converge to a global interpretation that matches what we consciously perceive. This convergence seems to occur only if the observer is conscious.

When we view a more complex moving shape, such as a moving rectangle, the local ambiguities still exist, but now they can be resolved, because the different sides of the rectangle provide distinct motion cues that combine into a unique percept. Only a single direction of motion jointly satisfies the constraints arising from each side (see figure 14). Our visual brain infers it and lets us see the only rigid movement that fits the bill. Neuronal recordings show that this inference takes time: for a full tenth of a second, neurons in area MT “see” only the local motion, and it takes them 120 to 140 milliseconds before they change their mind and encode the global direction.8 Consciousness, however, is oblivious to this complex operation. Subjectively, we see only the end result, a seamlessly moving rectangle, without ever realizing that our initial sensations were ambiguous and that our neuronal circuits had to work hard to make sense of them.

Fascinatingly, the convergence process that leads our neurons to agree on a single interpretation vanishes under anesthesia.9 The loss of consciousness is accompanied by a sudden dysfunction of the neuronal circuits that integrate our senses into a single coherent whole. Consciousness is needed for neurons to exchange signals in both bottom-up and top-down directions until they agree with one another. In its absence, the perceptual inference process stops short of generating a single coherent interpretation of the outside world.

The role of consciousness in resolving perceptual ambiguities is nowhere as evident as when we purposely craft an ambiguous visual stimulus. Suppose we present the brain with two superimposed gratings moving in different directions (figure 15). The brain has no way of telling whether the first grating lies in front of the other, or vice versa. Subjectively, however, we do not perceive this basic ambiguity. We never perceive a blend of two possibilities, but our conscious perception decides and lets us see one of the two gratings in the foreground. The two interpretations alternate: every few seconds, our perception changes and we see the other grating move into the foreground. Alexandre Pouget and his collaborators have shown that, when parameters such as speed and spacing are varied, the time that our conscious vision spends entertaining an interpretation is directly related to its likelihood, given the sensory evidence received.10 What we see, at any time, tends to be the most likely interpretation, but other possibilities occasionally pop up and stay in our conscious vision for a time duration that is proportional to their statistical likelihood. Our unconscious perception works out the probabilities—and then our consciousness samples from them at random.

FIGURE 15. Consciousness lets us see only one of the plausible interpretations of our sensory inputs. A display consisting of two superimposed gratings is ambiguous: either grating can be perceived to lie in front. But at any given moment, we are aware of only one of those possibilities. Our conscious vision alternates between the two percepts, and the proportion of time spent in one state is a direct reflection of the probability that this interpretation is correct. Thus our unconscious vision computes a landscape of probabilities, and our consciousness samples from it.

The existence of this probabilistic law shows that even as we are consciously perceiving an interpretation of an ambiguous scene, our brain is still pondering all the other interpretations and remains ready to change its mind at any moment. Behind the scenes, an unconscious Sherlock endlessly computes with probability distributions: as Peirce inferred, “the whole fabric of our knowledge is one matted felt of pure hypothesis confirmed and refined by induction.” Consciously, however, all we get to see is a single sample. As a result, vision does not feel like a complex exercise in mathematics; we open our eyes, and our conscious brain lets in only a single sight. Paradoxically, the sampling that goes on in our conscious vision makes us forever blind to its inner complexity.

Sampling seems to be a genuine function of conscious access, in the sense that it does not occur in the absence of conscious attention. Consider binocular rivalry, which you might remember from Chapter 1: the unstable perception that results from presenting two distinct images to the two eyes. When we attend to them, the images ceaselessly alternate in our awareness. Although the sensory input is fixed and ambiguous, we perceive it as constantly changing, as we become aware of only one image at a time. Crucially, however, when we orient our attention elsewhere, the rivalry stops.11 Discrete sampling seems to occur only when we consciously attend. As a consequence, unconscious processes are more objective than conscious ones. Our army of unconscious neurons approximates the true probability distribution of the states of the world, while our consciousness shamelessly reduces it to all-or-none samples.

The whole process bears an intriguing analogy to quantum mechanics (although its neural mechanisms most likely involve only classical physics). Quantum physicists tell us that physical reality consists in a superposition of wave functions that determine the probability of finding a particle in a certain state. Whenever we care to measure, however, these probabilities collapse to a fixed all-or-none state. We never observe strange mixtures such as the famed Schrödinger’s cat, half alive and half dead. According to quantum theory, the very act of physical measurement forces the probabilities to collapse into a single discrete measure. In our brain, something similar happens: the very act of consciously attending to an object collapses the probability distribution of its various interpretations and lets us perceive only one of them. Consciousness acts as a discrete measurement device that grants us a single glimpse of the vast underlying sea of unconscious computations.

Still, this seductive analogy may be superficial. Only future research will tell us whether some of the mathematics behind quantum mechanics can be adapted to the cognitive neuroscience of conscious perception. What is certain, though, is that in our brains, such a division of labor is ubiquitous: unconscious processes act as fast and massively parallel statisticians, while consciousness is a slow sampler. We see this not only in vision but also in the domain of language.12 Whenever we perceive an ambiguous word like bank, as we saw in Chapter 2, its two meanings are temporarily primed within our unconscious lexicon, even though we gain conscious awareness of only one of them at a time.13 The same principle underlies our attention. It feels as if we can attend to only a single location at a time, but the unconscious mechanism by which we select an object is actually probabilistic and considers several hypotheses at once.14

An unconscious sleuth even hides in our memory. Try to answer the following question: What percentage of the world’s airports is located in the United States? Please venture a guess, even if it feels difficult. Done? Now discard your first guess and give me a second one. Research shows that even your second guess is not random. Furthermore, if you have to bet, you are better off responding with the average of your two answers than with either guess alone.15 Once again, conscious retrieval acts as an invisible hand that draws at random from a hidden distribution of likelihoods. We can take a first sample, a second, and even a third, without exhausting the power of our unconscious mind.

An analogy may be useful: consciousness is like the spokesperson in a large institution. Vast organizations such as the FBI, with their thousands of employees, always possess considerably more knowledge than any single individual can ever grasp. As the sad episode of September 11, 2001, illustrates, it is not always easy to extract the relevant knowledge from the vast arrays of irrelevant beliefs that every employee entertains. In order to avoid drowning in the bottomless sea of facts, the president relies on short briefs compiled by a pyramidal staff, and he lets a single spokesperson express this “common wisdom.” Such a hierarchical use of resources is generally rational, even if it implies neglecting the subtle hints that could be the crucial signs that a dramatic event is brewing.

As a large-scale institution with a staff of a hundred billion neurons, the brain must rely on a similar briefing mechanism. The function of consciousness may be to simplify perception by drafting a summary of the current environment before voicing it out loud, in a coherent manner, to all other areas involved in memory, decision, and action.

In order to be useful, the brain’s conscious brief must be stable and integrative. During a nationwide crisis, it would be pointless for the FBI to send the president thousands of successive messages, each holding a little bit of truth, and let him figure it out for himself. Similarly, the brain cannot stick to a low-level flux of incoming data: it must assemble the pieces into a coherent story. Like a presidential brief, the brain’s conscious summary must contain an interpretation of the environment written in a “language of thought” that is abstract enough to interface with the mechanisms of intention and decision making.

Lasting Thoughts

The improvements we install in our brain when we learn our languages permit us to review, recall, rehearse, redesign our own activities, turning our brains into echo chambers of sorts, in which otherwise evanescent processes can hang around and become objects in their own right. Those that persist the longest, acquiring influence as they persist, we call our conscious thoughts.

—Daniel Dennett, Kinds of Minds (1996)

Consciousness is then, as it were, the hyphen which joins what has been to what will be, the bridge which spans the past and the future.

—Henri Bergson, Huxley Memorial Lecture (1911)

There may be a very good reason why our consciousness condenses sensory messages into a synthetic code, devoid of gaps and ambiguities: such a code is compact enough to be carried forward in time, entering what we usually call “working memory.” Working memory and consciousness seem to be tightly related. One may even argue, with Daniel Dennett, that a main role of consciousness is to create lasting thoughts. Once a piece of information is conscious, it stays fresh in our mind for as long as we care to attend to it and remember it. The conscious brief must be kept stable enough to inform our decisions, even if they take a few minutes to form. This extended duration, thickening the present moment, is characteristic of our conscious thoughts.

A cellular mechanism of transient memory exists in all mammals, from humans to monkeys, cats, rats, and mice. Its evolutionary advantages are obvious. Organisms that have a memory become detached from pressing environmental contingencies. They are no longer tied to the present but can recall the past and anticipate the future. When an organism’s predator hides behind a rock, remembering its invisible presence is a matter of life and death. Many environmental events recur at unspecified time intervals, over vast expanses of space, and indexed by a diversity of cues. The capacity to synthesize information over time, space, and modalities of knowledge, and to rethink it at any time in the future, is a fundamental component of the conscious mind, one that seems likely to have been positively selected for during evolution.

The component of the mind that psychologists call “working memory” is one of the dominant functions of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the areas that it connects with, thus making these areas strong candidates for the depositories of our conscious knowledge.16 These regions pop up in brain imaging experiments whenever we briefly hold on to a piece of information: a phone number, a color, or the shape of a flashed picture. Prefrontal neurons implement an active memory: long after the picture is gone, they continue to fire throughout the short-term memory task—sometimes as long as dozens of seconds later. And when the prefrontal cortex is impaired or distracted, this memory is lost—it falls into unconscious oblivion.

Patients who suffer from lesions of the prefrontal cortex also exhibit major deficiencies in planning the future. Their remarkable cluster of symptoms suggests a lack of foresight and a stubborn adherence to the present. They seem unable to inhibit unwanted actions and may automatically seize and use tools (utilization behavior) or irrepressibly mimic others (imitation behavior). Their capacities for conscious inhibition, long-term thinking, and planning may be drastically deteriorated. In the most severe cases, apathy and a variety of other symptoms indicate a glaring gap in the quality and contents of mental life. The disorders that relate directly to consciousness include hemineglect (perturbed awareness of one half of space, usually the left), abulia (incapacity to generate voluntary actions), akinetic mutism (inability to generate spontaneous verbal reports, though repetition may be intact), anosognosia (unawareness of a major deficit, including paralysis), and impaired autonoetic memory (incapacity to recall and analyze one’s own thoughts). Tampering with the prefrontal cortex can even interfere with abilities as basic as perceiving and reflecting upon a brief visual display.17

To summarize, the prefrontal cortex seems to play a key role in our ability to maintain information over time, to reflect upon it, and to integrate it into our unfolding plans. Is there more direct evidence that such temporally extended reflection necessarily involves consciousness? The cognitive scientists Robert Clark and Larry Squire conducted a wonderfully simple test of temporal synthesis: time-lapse conditioning of the eyelid reflex.18 At a precisely timed moment, a pneumatic machine puffs air toward the eye. The reaction is instantaneous: in rabbits and humans alike, the protective membrane of the eyelid immediately closes. Now precede the delivery of air with a brief warning tone. The outcome is called Pavlovian conditioning (in memory of the Russian physiologist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, who first conditioned dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell, in anticipation of food). After a short training, the eye blinks to the sound itself, in anticipation of the air puff. After a while, an occasional presentation of the isolated tone suffices to induce the “eyes wide shut” response.

The eye-closure reflex is fast, but is it conscious or unconscious? The answer, surprisingly, depends on the presence of a temporal gap. In one version of the test, usually termed “delayed conditioning,” the tone lasts until the puff arrives. Thus the two stimuli briefly coincide in the animal’s brain, making the learning a simple matter of coincidence detection. In the other, called “trace conditioning,” the tone is brief, separated from the subsequent air puff by an empty gap. This version, although minimally different, is clearly more challenging. The organism must keep an active memory trace of the past tone in order to discover its systematic relation to the subsequent air puff. To avoid any confusion, I will call the first version “coincidence-based conditioning” (the first stimulus lasts long enough to coincide with the second, thus removing any need for memory) and the second “memory-trace conditioning” (the subject must keep in mind a memory trace of the sound in order to bridge the temporal gap between it and the obnoxious air puff).

The experimental results are clear: coincidence-based conditioning occurs unconsciously, while for memory-trace conditioning, a conscious mind is required.19 In fact, coincidence-based conditioning does not require any cortex at all. A decerebrate rabbit, without any cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, limbic system, thalamus, and hypothalamus, still shows eyelid conditioning when the sound and the puff overlap in time. In memory-trace conditioning, however, no learning occurs unless the hippocampus and its connected structures (which include the prefrontal cortex) are intact. In human subjects, memory-trace learning seems to occur if and only if the person reports being aware of the systematic predictive link between the tone and the air puff. Elderly people, amnesiacs, and people who were simply too distracted to notice the temporal relationship show no conditioning at all (whereas these manipulations have no effect whatsoever on coincidence-based conditioning). Brain imaging shows that the subjects who gain awareness are precisely those who activate their prefrontal cortex and hippocampus during the learning.

Overall, the conditioning paradigm suggests that consciousness has a specific evolutionary role: learning over time, rather than simply living in the instant. The system formed by the prefrontal cortex and its interconnected areas, including the hippocampus, may serve the essential role of bridging temporal gaps. Consciousness provides us with a “remembered present,” in the words of Gerald Edelman:20 Thanks to it, a selected subset of our past experiences can be projected into the future and cross-linked with the present sensory data.

What is particularly interesting about the memory-trace conditioning test is that it is simple enough to be administered to all sorts of organisms, from infants to monkeys, rabbits, and mice. When mice take the test, they activate anterior brain regions that are homologous to the human prefrontal cortex.21 The test may thus be tapping one of the most basic functions of consciousness, an operation so essential that it may also be present in many other species.

If a temporally extended working memory requires consciousness, is it impossible to stretch our unconscious thoughts across time? Empirical measures of the duration of subliminal activity suggest that it is—subliminal thoughts last only for an instant.22 The lifetime of a subliminal stimulus can be estimated by measuring how long one has to wait before its effect decays to zero. The result is very clear: a visible image may have a long-lasting effect, but an invisible one exerts only a short-lived influence on our thoughts. Whenever we render an image invisible by masking, it nevertheless activates visual, orthographic, lexical, or even semantic representations in the brain, but only for a brief duration. After a second or so, the unconscious activation generally decays to an undetectable level.

Many experiments show that subliminal stimuli undergo a rapid exponential decay in the brain. Summarizing these findings, my colleague Lionel Naccache concluded (contradicting the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan) that “the unconscious is not structured as a language but as a decaying exponential.”23 With effort, we may keep subliminal information alive for a slightly longer period—but the quality of this memory is so degraded that our recall, after a few seconds’ delay, barely exceeds the level of chance.24 Only consciousness allows us to entertain lasting thoughts.

The Human Turing Machine

Once information is “in mind,” protected from temporal decay, can it enter into specific operations? Do some cognitive operations require consciousness and lie beyond the scope of our unconscious thought processes? The answer seems to be positive: in humans at least, consciousness gives us the power of a sophisticated serial computer.

For instance, try to compute 12 times 13 in your head.

Finished?

Did you feel each of the arithmetic operations churning in your brain, one after the other? Can you faithfully report the successive steps that you took, and the intermediate results that they returned? The answer is usually yes; we are aware of the serial strategies that we deploy to multiply. Personally, I first remembered that 12² is 144, then added another 12. Others may multiply the digits one after the other according to the classical multiplication recipe. The point is this: whatever strategy we use, we can consciously report it. And our report is accurate: it can be cross-validated by behavioral measures of response time and eye movements.25 Such accurate introspection is unusual in psychology. Most mental operations are opaque to the mind’s eye; we have no insight into the operations that allow us to recognize a face, plan a step, add two digits, or name a word. Somehow multidigit arithmetic is different: it seems to consist of a series of introspectable steps. I propose that there is a simple reason for it. Complex strategies, formed by stringing together several elementary steps—what computer scientists call “algorithms”—are another of consciousness’s uniquely evolved functions.

Would you be able to calculate 12 times 13 unconsciously if the problem was presented to you in a subliminal flash? No, never.26 A slow dispatching system seems necessary to store intermediate results and pass them on to the next step. The brain must contain a “router” that allows it to flexibly broadcast information to and from its internal routines.27 This seems to be a major function of consciousness: to collect the information from various processors, synthesize it, and then broadcast the result—a conscious symbol—to other, arbitrarily selected processors. These processors, in turn, apply their unconscious skills to this symbol, and the entire cycle may repeat a number of times. The outcome is a hybrid serial-parallel machine, in which stages of massively parallel computation are interleaved with a serial stage of conscious decision making and information routing.

Together with the physicists Mariano Sigman and Ariel Zylberberg, I have begun to explore the computational properties that such a device would possess.28 It closely resembles what computer scientists call a “production system,” a type of program introduced in the 1960s to implement artificial intelligence tasks. A production system comprises a database, also called “working memory,” and a vast array of if-then production rules (e.g., if there is an A in working memory, then change it to the sequence BC). At each step, the system examines whether a rule matches the current state of its working memory. If multiple rules match, then they compete under the aegis of a stochastic prioritizing system. Finally, the winning rule “ignites” and is allowed to change the contents of working memory before the entire process resumes. Thus this sequence of steps amounts to serial cycles of unconscious competition, conscious ignition, and broadcasting.

Remarkably, production systems, although very simple, have the capacity to implement any effective procedure—any thinkable computation. Their power is equivalent to that of the Turing machine, a theoretical device that was invented by the British mathematician Alan Turing in 1936 and that lies at the foundation of the digital computer.29 Thus our proposal is tantamount to saying that, with its flexible routing capacity, the conscious brain operates as a biological Turing machine. It allows us to slowly churn out series of computations. These computations are very slow because, at each step, the intermediate result must be transiently maintained in consciousness before being passed on to the next stage.

There is an interesting historical twist to this argument. When Alan Turing invented his machine, he was trying to address a challenge posed by the mathematician David Hilbert in 1928: Could a mechanical procedure ever replace the mathematician and, by purely symbolic manipulation, decide whether a given statement of mathematics follows logically from a set of axioms? Turing deliberately designed his machine to mimic “a man in the process of computing a real number” (as he wrote in his seminal 1936 paper). He was not a psychologist, however, and could rely only on his introspection. This is why, I contend, his machine captures only a fraction of the mathematician’s mental processes, those that are consciously accessible. The serial and symbolic operations that are captured by a serial Turing machine constitute a reasonably good model of the operations accessible to a conscious human mind.

Don’t get me wrong—I do not intend to revive the cliché of the brain as a classical computer. With its massively parallel, self-modifiable organization, capable of computing over entire probability distributions rather than discrete symbols, the human brain departs radically from contemporary computers. Neuroscience, indeed, has long rejected the computer metaphor. But the brain’s behavior, when it engages in long calculations, is roughly captured by a serial production system or a Turing machine.30 For instance, the time that it takes us to compute a long addition such as 235 + 457 is the sum of the durations of each elementary operation (5 + 7; carry; 3 + 5 + 1; and finally 2 + 4)—as would be expected from the sequential execution of each successive step.31

The Turing model is idealized. When we zoom in on human behavior, we see deviations from its predictions. Instead of being neatly separate in time, successive stages slightly overlap and create an undesired cross-talk among operations.32 During mental arithmetic, the second operation can start before the first one is fully finished. Jérôme Sackur and I studied one of the simplest possible algorithms: take a number n, add 2 to it (n + 2), and then decide if the result is larger or smaller than 5 (n + 2 > 5?). We observed interference: unconsciously, participants started to compare the initial number n with 5, even before they had obtained the intermediate result n + 2.33 In a computer, such a silly error would never occur; a master clock controls each step, and digital routing ensures that each bit always reaches its intended destination. The brain, however, never evolved for complex arithmetic. Its architecture, selected for survival in a probabilistic world, explains why we make so many errors during mental calculation. We painfully “recycle” our brain networks for serial calculations, using conscious control to exchange information in a slow and serial manner.34

If one of the functions of consciousness is to serve as a lingua franca of the brain, a medium for the flexible routing of information across otherwise specialized processors, then a simple prediction ensues: a single routinized operation may unfold unconsciously, but unless the information is conscious, it will be impossible to string together several such steps. In the domain of arithmetic, for instance, our brain might well compute 3 + 2 unconsciously, but not (3 + 2)², (3 + 2) – 1, or 1/(3 + 2). Multistep calculations will always require a conscious effort.35

Sackur and I set out to test this idea experimentally.36 We flashed a target digit n and masked it, so that our participants could see it only half the time. We then asked them to perform a variety of operations with it. In three different blocks of trials, they attempted to name it, to add 2 to it (the n + 2 task), and to compare it with 5 (the n > 5 task). A fourth block required a two-step calculation: add 2, then compare the result with 5 (the n + 2 > 5 task). On the first three tasks, people did much better than chance. Even when they swore they hadn’t seen anything, we asked them to venture an answer, and they were surprised to discover the extent of their unconscious knowledge. They could name the unseen digit much better than chance alone would predict: nearly half of their verbal responses were correct, whereas with four digits, guessing performance should have been 25 percent. They could even add 2 to it, or decide, above chance level, whether the digit was larger than 5. All these operations, of course, are familiar routines. As we saw in Chapter 2, there is a lot of evidence that they can be partially launched without consciousness. Crucially, however, during the unconscious two-step task (n + 2 > 5?), the participants failed: they responded at random. This is strange, because if they had just thought of naming the digit, and used the name to perform the task, they would have reached a very high level of success! Subliminal information was demonstrably present in their brains, since they correctly uttered the hidden number about half of the time—but without consciousness, it could not be channeled through a series of two successive stages.

In Chapter 2, we saw that the brain has no difficulty in unconsciously accumulating information: several successive arrows,37 digits,38 and even cues toward buying a car39 can be added together, and the total evidence can guide our unconscious decisions. Is this a contradiction? No—because the accumulation of multiple pieces of evidence is a single operation for the brain. Once a neuronal accumulator is open, any information, whether conscious or unconscious, can bias it one way or the other. The only step that our unconscious decision-making process does not seem to achieve is a clear decision that can be passed on to the next stage. Although biased by unconscious information, our central accumulator never seems to reach the threshold beyond which it commits to a decision and moves on to the next step. As a consequence, in a complex calculation strategy, our unconscious remains stuck at the level of accumulating evidence for the first operation and never goes on to the second.

A more general consequence is that we cannot reason strategically on an unconscious hunch. Subliminal information cannot enter into our strategic deliberations. This point seems circular, but it isn’t. Strategies are, after all, just another type of brain process—so it isn’t so trivial that this process cannot be deployed without consciousness. Furthermore, it has genuine empirical consequences. Remember the arrows task, where one views five successive arrows pointing right or left and has to decide where the majority of them point? Any conscious mind quickly realizes that there is a winning strategy: once we have seen three arrows pointing to the same side, the game is over, as no amount of additional information can change the final answer. Participants readily exploit this strategy to get more quickly through the task. However, once again, they can do so only if the information is conscious, not if it is subliminal.40 When the arrows are masked below the threshold for awareness, all they do is add them up—they cannot unconsciously make the strategic move to the next step.

All together, then, these experiments point to a crucial role for consciousness. We need to be conscious in order to rationally think through a problem. The mighty unconscious generates sophisticated hunches, but only a conscious mind can follow a rational strategy, step after step. By acting as a router, feeding information through any arbitrary string of successive processes, consciousness seems to give us access to a whole new mode of operation—the brain’s Turing machine.

A Social Sharing Device

Consciousness is properly only a connecting network between man and man; it is only as such that it has had to develop: the recluse and wild-beast species of men would not have needed it.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (1882)

In Homo sapiens, conscious information does not propagate solely within one individual’s head. Thanks to language, it can also jump from mind to mind. During human evolution, social information sharing may have been one of the essential functions of consciousness. Nietzsche’s “wild-beast species” probably relied on consciousness as a nonverbal buffer and router for millions of years—but only in the genus Homo did a sophisticated capacity to communicate those conscious states emerge. Thanks to human language, as well as to nonverbal pointing and gesturing, the conscious synthesis that emerges in one mind can be rapidly transferred to others. This active social transmission of a conscious symbol offers new computational abilities. Humans can create “multicore” social algorithms that do not draw solely on the knowledge available to a single mind but rather allow the confrontation of multiple points of view, variable levels of expertise, and a diversity of sources of knowledge.

It is no accident that verbal reportability—the capacity to put a thought into words—is considered a key criterion for conscious perception. We do not usually conclude that someone is aware of a piece of information unless he or she can, at least in part, formulate it with language (assuming, of course, that he is not paralyzed, aphasic, or too young to speak). In humans, the “verbal formulator” that allows us to express the contents of our mind is an essential component that can be deployed only when we are conscious.41

I do not mean, of course, that we can always accurately express our conscious thoughts with Proustian accuracy. Consciousness overflows language: we perceive vastly more than we can describe. The fullness of our experience of a Caravaggio painting, a gorgeous sunset over the Grand Canyon, or the changing expressions on a baby’s face eludes exhaustive verbal description—which probably contributes in no small part to the fascination they exert. Nevertheless, and virtually by definition, whatever we are aware of can be at least partially framed in a linguistic format. Language provides a categorical and syntactic formulation of conscious thoughts that jointly lets us structure our mental world and share it with other human minds.

Sharing information with others is a second reason our brain finds it advantageous to abstract from the details of our present sensations and create a conscious “brief.” Words and gestures provide us with only a slow communication channel—only 40 to 60 bits per second,42 or about 300 times slower than the (now antiquated) 14,400-baud faxes that revolutionized our offices in the 1990s. Hence our brain drastically compresses the information to a condensed set of symbols that are assembled into short strings, which are then sent over the social network. It would actually be pointless to transmit to others a precise mental image of what I see from my own point of view; what others want is not a detailed description of the world as I see it, but a summary of the aspects that are likely to also be true from my interlocutor’s viewpoint: a multisensory, viewer-invariant, and durable synthesis of the environment. In humans, at least, consciousness seems to condense information into exactly the kind of précis that other minds are likely to find useful.

The reader may object that language often serves trivial goals, such as exchanging the latest gossip about which Hollywood actress slept with whom. According to the Oxford anthropologist Robin Dunbar, close to two-thirds of our conversations may concern such social topics; he even proposed the “grooming and gossip” theory of language evolution, according to which language emerged solely as a bonding device.43

Can we prove that our conversations are more than tabloids? Can we show that they pass on to others precisely the sort of condensed information that is needed to make collective decisions? The Iranian psychologist Bahador Bahrami recently proved this idea using a clever experiment.44 He had pairs of subjects perform a simple perceptual task. They were shown two displays, and their goal was to decide, on each trial, whether the first or the second contained a near-threshold target image. The two participants were first asked to give independent responses. The computer then revealed their choices, and if they disagreed, the subjects were asked to resolve the conflict through a brief discussion.

What is particularly smart about this experiment is that, in the end, on each trial, the pair of subjects behaved as a single participant: they always provided a single answer, whose accuracy could be gauged using exactly the same good old methods of psychophysics that are classically used to evaluate a single person’s behavior. And the results were clear: as long as the two participants’ abilities were reasonably similar, pairing them yielded a significant improvement in accuracy. The group systematically outperformed the best of its individual members—giving substance to the familiar saying “Two heads are better than one.”

A great advantage of Bahrami’s setup is that it can be modeled mathematically. Assuming that each person perceives the world with his or her personal noise level, it is easy to compute how their sensations should be combined: the strength of the signals that each player perceived on a given trial should be inversely weighted by the player’s average noise level, then averaged together to yield a single compound sensation. This optimal rule for multibrain decisions is, in fact, exactly identical to the law governing multisensory integration within a single brain. It can be approximated by a very simple rule of thumb: in most cases, people need to communicate not the nuances of what they saw (which would be impossible) but simply a categorical answer (in this case, the first or the second display) accompanied by a judgment of confidence (or lack thereof).

It turned out that the successful pairs of participants spontaneously adopted this strategy. They talked about their confidence level using words such as certain, very unsure, or just guessing. Some of them even designed a numerical scale to precisely gauge their degree of certainty. Using such confidence-sharing schemes, their paired performance shot up to a very high level, essentially indistinguishable from the theoretical optimum.

Bahrami’s experiment readily explains why judgments of confidence occupy such a central location in our conscious minds. In order to be useful to us and to others, each of our conscious thoughts must be earmarked with a confidence label. Not only do we know that we know, or that we don’t, but whenever we are conscious of a piece of information, we can ascribe to it a precise degree of certainty or uncertainty. Furthermore, socially, we constantly endeavor to monitor the reliability of our sources, keeping in mind who said what to whom, and whether they were right or wrong (which is precisely what makes gossip a central feature of our conversations). These evolutions, largely unique to the human brain, point to the evaluation of uncertainty as an indispensable component of our social decision-making algorithm.

Bayesian decision theory tells us that the very same decision-making rules should apply to our own thoughts and to those that we receive from others. In both cases, optimal decision making demands that each source of information, whether internal or external, should be weighted, as accurately as possible, by an estimate of its reliability, before all the information is brought together into a single decision space. Prior to hominization, the primate prefrontal cortex already provided a workspace where past and present sources of information, duly weighted by their reliability, could be compiled to guide decisions. From there, a key evolutionary step, perhaps unique to humans, seems to have opened this workspace to social inputs from other minds. The development of this social interface allowed us to reap the benefits of a collective decision-making algorithm: by comparing our knowledge with that of others, we achieve better decisions.

Thanks to brain imaging, we are beginning to elucidate which brain networks support information sharing and reliability estimation. Whenever we deploy our social competence, the most anterior sectors of the prefrontal cortex, in the frontal pole and along the midline of the brain (within the ventromedial prefrontal cortex), are systematically activated. Posterior activations often occur as well, in a region lying at the junction of the temporal and parietal lobes, as well as along the brain’s midline (the precuneus). These distributed areas form a brain-scale network, tightly interconnected by powerful long-distance fiber tracks, involving the prefrontal cortex as a central node. This network figures prominently among the circuits that turn on during rest, whenever we have a few seconds to ourselves: we spontaneously return to this “default mode” system of social tracking in our free time.45

Most remarkably, as would be expected from the social decision-making hypothesis, many of these regions activate both when we think about ourselves—for instance, when we introspect about our level of confidence in our own decisions46—and when we reflect upon the thoughts of others.47 The frontal pole and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, in particular, show very similar response profiles during judgments about ourselves and about others48—to such an extent that thinking hard about one may prime the other.49 Thus this network appears ideally suited to evaluate the reliability of our own knowledge and compare it with the information we receive from others.

In brief, within the human brain lies a set of neural structures uniquely adapted to the representation of our social knowledge. We use the same database to encode our self-knowledge and to accumulate information about others. These brain networks build a mental image of our own self as a peculiar character sitting next to others in a mental database of our social acquaintances. Each of us represents “oneself as another,” as the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur puts it.50

If this view of the self is correct, then the neural underpinnings of our own identity are built up in a rather indirect manner. We spend our life monitoring our behavior as well as that of others, and our statistical brain constantly draws inferences about what it observes, literally “making up its mind” as it proceeds.51 Learning who we are is a statistical deduction from observation. Having spent a lifetime with ourselves, we reach a view of our own character, knowledge, and confidence that is only a bit more refined than our view of other people’s personalities. Furthermore, our brain does enjoy privileged access to some of its inner workings.52 Introspection makes our conscious motives and strategies transparent to us, while we have no sure means of deciphering them in others. Yet we never genuinely know our true selves. We remain largely ignorant of the actual unconscious determinants of our behavior, and therefore we cannot accurately predict what our behavior will be in circumstances beyond the safety zone of our past experience. The Greek motto “Know thyself,” when applied to the minute details of our behavior, remains an inaccessible ideal. Our “self” is just a database that gets filled in through our social experiences, in the same format with which we attempt to understand other minds, and therefore it is just as likely to include glaring gaps, misunderstandings, and delusions.

Needless to say, these limits of the human condition have not escaped novelists. In his introspective novel Thinks . . . , the British contemporary writer David Lodge depicts his two main characters, the English teacher Helen and the artificial intelligence mogul Ralph, exchanging thoughtful reflections upon the self, while lightly flirting at night in an outdoor Jacuzzi:

Helen: I suppose it must have a thermostat. Does that make it con-scious?

Ralph: Not self-conscious. It doesn’t know it’s having a good time–unlike you and me.

Helen: I thought there was no such thing as the self.

Ralph: No such thing, no, if you mean a fixed discrete entity. But of course there are selves. We make them up all the time. Like you make up stories.

Helen: Are you saying our lives are just fictions?

Ralph: In a way. It’s one of the things we do with our spare brain capacity. We make up stories about ourselves.

Partially deluding ourselves may be the price we pay for a uniquely human evolution of consciousness: the ability to communicate our conscious knowledge with others, in rudimentary form, but with exactly the sort of confidence evaluation that is mathematically needed to reach a useful collective decision. Imperfect as it is, our human ability for introspecting and social sharing has created alphabets, cathedrals, jet planes, and lobster Thermidor. For the first time in evolution, it has also allowed us to voluntarily create fictive worlds: we can tweak the social decision-making algorithm to our advantage by faking, forging, counterfeiting, fibbing, lying, perjuring, denying, forswearing, arguing, refuting, and rebuffing. Vladimir Nabokov, in his Lectures on Literature (1980), saw it all:

Literature was not born the day when a boy crying “wolf, wolf” came running out of the Neanderthal valley with a big gray wolf at his heels; literature was born on the day when a boy came crying “wolf, wolf” and there was no wolf behind him.

Consciousness is the mind’s virtual-reality simulator. But how does the brain make up the mind?