INTRODUCTION

A NEW APPROACH

Why do campus sexual assaults happen? And what should be done to prevent them? Sexual Citizens offers parents, students, school administrators, policy makers, and the public a new way to understand sexual assault and an approach to prevention that extends far beyond the campus gates. Our perspective is based upon a landmark research project: the Sexual Health Initiative to Foster Transformation, or SHIFT. Along with nearly thirty other researchers, we’ve spent the last five years undertaking one of the most comprehensive studies of campus sex and sexual assault. Sexual Citizens draws upon that research, providing detailed portraits of a wide range of undergraduates’ sexual experiences—from consensual sex to sexual assault—at Columbia University. We’ll hear about men like Austin, whose attentiveness to his girlfriend’s pleasure contrasts starkly with the night he assaulted a woman he barely knew, when both were drunk in her room. We’ll discuss why Adam never talked to his boyfriend about how pushy and forceful he was about sex, even after his boyfriend came home one evening after a long night of drinking and “basically raped” him. We’ll write about Michaela, a queer Black woman, who refused to accept as normal being touched, brushed up against, and grabbed on a dance floor—experiences that heterosexual women (and some heterosexual men) see as an inevitable part of being in those spaces. And we’ll meet women like Luci, who was raped by Scott, a senior, when she was a freshman, and a virgin. As Scott took off Luci’s pants, she exclaimed, “No! Don’t!” His response was, “It’s okay.”

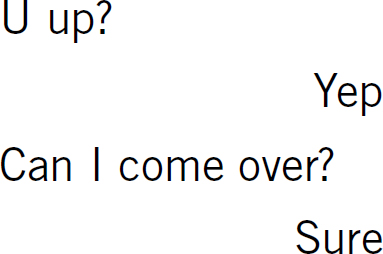

We spoke with many students whose pre-college sex education consisted primarily of instruction about the perils of sex. Once on campus, they had all learned about “affirmative consent”; they dutifully told us that in order for sex to be consensual, both parties have to say “yes,” and be sober enough to know what they’re saying yes to. But over the course of our research we found that the moment of consent frequently looks more like this, often drunken, text exchange:

We have to do better. Sexual Citizens shows how.

Since the fall of 2014, we have been part of SHIFT’s research on campus sexual assault. Jennifer codirected SHIFT with her friend and colleague clinical psychologist Claude Ann Mellins, an expert in adolescent and young adult development, mental health, substance use, and trauma.1 Sexual Citizens primarily draws on the ethnographic component of the SHIFT research, which Jennifer and Shamus led together. Our ethnographic research, conducted between the late summer of 2015 and January of 2017, consisted of over 150 interviews, about two hours each, eliciting young people’s broad accounts of their lives and how sex fit into them. We combined these interviews with talking to students in groups, and having SHIFT research team members spend time with students in dorms, the bus to the athletic fields, fraternity basements, and spaces of worship. SHIFT also included a large survey of over 1,600 undergraduates’ histories, relationships, and experiences with sex and assault, and another that surveyed nearly 500 students daily for 60 days, asking them about stress, sleep, socializing, sex, sexual assault, and substance use in the prior twenty-four hours. (Throughout the book, the term “substance use” includes alcohol, illegal drugs, or legal drugs used outside the supervision of a physician; the primary substance on which we focus is alcohol.) Sexual Citizens builds on the work of others who have conducted research on campus sexual assault using interviews and observations.2 But the design—deep ethnographic engagement, nested within the work of a large research team—has allowed us to contextualize and enrich our findings, yielding fresh insights.

It isn’t just the amount or type of data that makes us different. It’s how we think about the problem. Our focus is on the social roots of sexual assault. This is a starkly different starting point than the two major themes of public discussion. The first directs attention to predators, or toxic masculinity, as the problem. The second is the focus on what to do after assaults occur—how to adjudicate those “he said/she said” moments. Instead of thinking in terms of predators or post-assault procedures, SHIFT examined the social drivers of assault, in order to develop new approaches to making assault a less common feature of college life. We deployed what public health scholars call an “ecological model.”3 This approach situates individuals, along with their problem behaviors, in the broader context of their relationships, their pre-college histories, the organizations they are a part of, and the cultures that influence them.

Thinking about sexual assault as a public health problem expands the focus from individuals and how they interact, to systems. If we know that people are drinking water that is polluted, one solution is to try and educate every person about how to use that water in safe ways. Another is to go upstream and remove the toxins from the water, reducing the need to change individual behavior one person at a time. Effectively, this book asks, “What would the ‘clean water’ approach to sexual assault look like?” The creation of a context that nudges people toward making decisions that are good for themselves and others, or “choice architecture,” a theory for which Richard Thaler won the Nobel Prize in economics, calls attention to how much impact can come from working at the system and community level.4 In her prior work on HIV, Jennifer has argued for prevention approaches that go beyond working “one penis at a time.”5 In the case of sexual assault, in addition to instructing students, “Don’t rape anyone; don’t get raped; don’t let your friends get raped,” what if prevention work did more to address the social context that makes rape and other forms of sexual assault such a predictable element of campus life?

This perspective yields a new language for sexual assault, based on analyzing the ecosystems in which it occurs: the forces that influence young adults’ sexual lives; the relationships people share; the power dynamics between them; how sex fits into students’ lives, and how physical spaces, alcohol, and peers produce opportunities for sex and influence the ways in which sex is subsequently interpreted and defined by those having it. Our approach mines everything from sexual literacy (or more precisely, illiteracy), to underage drinking, social cliques, stress, shame, and the spaces where they sleep. It incorporates earlier feminist writing on sexual assault, emphasizing gender inequality, sexuality, and power. But it expands upon that approach by exploring how race, socioeconomic status, and age, to name just a few intersecting forms of social inequality, are also essential to understanding assault. These factors deeply affect people’s sexual lives. This points to another way in which our approach is unique. While many insist that rape and sex are fundamentally different things, we maintain that understanding what young people are trying to accomplish with sex, why, and the contexts within which sex happens are all essential for a comprehensive analysis of sexual assault.

Better prevention is urgently needed. An analysis of SHIFT survey data led by Claude Mellins found that over one in four women, one in eight men, and more than one out of three gender-nonconforming students said that they’d been assaulted.6 Columbia is like other schools; similar rates of assault have been confirmed time and again by surveys in many different higher education contexts.7 The risk of assault is highest freshman year, but it accumulates over time; among seniors who completed the SHIFT survey, one in three women and almost one in six men had experienced an assault.8 And for many, it’s not just one assault; students who had been assaulted were assaulted, on average, three times. It’s not that college is particularly dangerous, compared to other settings. While the evidence is mixed, some studies suggest that young women in higher education settings are less likely to be assaulted than those of the same age who are not in school; and no study that we know of finds that women in college are more likely to be assaulted.9

The stories that students—and not just women—shared with us made clear the harms of sexual assault, and how parts of that suffering ripple through the whole campus community. If preventing sexual assault’s emotional and social harms is insufficient to justify more attention to prevention, we can also point to sexual assault’s vast economic impact. In 2017 researchers from the Centers for Disease Control estimated that across the population of the United States, the economic cost of rape was over $3 trillion.10

We seek to move readers beyond simply being shocked by these statistics, or saddened by the stories that follow. Our goal is to impel action, but from a position of empathy and understanding, rather than fear.

SEXUAL PROJECTS, SEXUAL CITIZENSHIP, SEXUAL GEOGRAPHIES

We explain students’ experiences—with pleasurable sex, sex that is consensual but not so pleasurable, and sexual assault—through three concepts: sexual projects, sexual citizenship, and sexual geographies. Together, these help us understand why sexual assault is a predictable consequence of how our society is organized, rather than solely a problem of individual bad actors. This sad reality has a hopeful implication: in working to better articulate sexual projects for young people, to cultivate their sexual citizenship, and to rearrange campus sexual geographies, we can make sexual assault far less likely. The conceptual framework that animates our analysis charts the path forward.

A sexual project encompasses the reasons why anyone might seek a particular sexual interaction or experience.11 Pleasure is an obvious project; but a sexual project can also be to develop and maintain a relationship; or it can be a project to not have sex; or to have sex for comfort; or to try to have children; or because sex can advance our position or status within a group, or increase the status of groups to which we belong. A sexual project can also be to have a particular kind of experience, like sex in the library stacks; sex can be the goal rather than a strategy toward another goal. People don’t just have one sexual project. They can have many. Wanting intimacy doesn’t mean not wanting other things, like to hook up from time to time.

Plenty of young people, driven by sexual anxieties, described college as a time to acquire sexual experience. In the words of one young man, he wanted to learn to “give good dick.” Other students’ projects were about their own gender or sexual identity. For those who might be exploring their trans, or queer, or gay identities, sex wasn’t just about who to have sex with. It was a project of coming to understand the person they were, or wanted to be. Still other projects were about status and building relationships with peers, sometimes with an edge of competition. Men and women would ask each other “What’s your number?” meaning, “How many people have you had sex with?” In that question, to be sure, “sex” is a purposefully vague umbrella term, encompassing a range of practices.12 For some students it meant penetrative intercourse, whereas others, particularly LGBTQ students, counted oral or manual stimulation as sex. But regardless of what they count, students strive for numbers high enough to convey expertise, but low enough to dodge being labeled a “fuckboy” or “whore.” Some students are far more interested in finding a relationship within which sex can happen. Others want intimacy but imagine that a partner can take up too much time, and so they satisfy their desire for a sexually intimate connection—or rather, as we show, partially satisfy it—outside of relationships, finding warmth and pleasure that feels otherwise missing in their achievement-oriented lives.

The young people in whose world we were immersed were frequently figuring out their sexual projects through trial and error, to no small degree because no one had spent much time talking to them about what a sexual project might be. Some, ashamed of their desires or their bodies, drink heavily to escape their rational, deliberate, considered state in order to feel comfortable having sex. For others, alcohol silences confusion rather than shame; they’re totally unclear on their projects, unable to answer, for themselves, the question “What is sex for?” Getting drunk is a good way to avoid thinking about it.

As we map the range of students’ sexual projects, we shy away from judgment about the morality of different projects, about what sex should be for. Our goal is to encourage families and institutions to initiate conversations about what kinds of sexual projects fit with their values. We heard about so many missed opportunities to shape and clarify young people’s values about sex. Many students told us that all their parents did was to hand them a book; at best, children were told, with some degree of discomfort, that they could ask questions later if they had them. The message was that sex was something uncomfortable, something not to be spoken about. Learning that it was best not to talk about sex played out, sometimes with disastrous consequences, in their future sexual experiences. Almost no one related an experience where an adult sat them down and conveyed that sex would be an important and potentially joyful part of their life, and so they should think about what they wanted from sex, and how to realize those desires with other people in a respectful way.

Time and again, we thought of how disappointed we were, not in young people, but in the communities that had raised them. And failed them. Students we spoke with had been bombarded with messages about college and career, but had generally received little guidance for how to think about sexually intimate relationships. Hungry for guidance, young people gleaned lessons from elsewhere: from their peers who are similarly in the dark, or from pornography.13

Crucially, sexual projects are embedded within other projects—like college projects—which together make up people’s life projects.14 A college project can be to learn, to fall in love, to get a job, to get drunk and do drugs, to discover what’s meaningful in life, or to figure out how to live on one’s own, away from one’s family, and in ways one desires. We adopt a “lifecourse perspective,” which acknowledges people’s multiple, emergent aims over the course of their lives, and examines how future aims and past experiences impact their present and future.15

Though forged in communities, sexual projects are intensely personal. And yet how partners fit within one’s sexual project is a critical moral question. Sadly, sexual partners often fit in as objects, rather than fully imagined, self-determining humans. We found that students whose sexual goal is connecting with another person are much more attentive to whether or not their partner wants to have sex than those whose goal is pleasure or status accrual. Treating people like objects doesn’t necessarily mean a student will inadvertently assault someone, but not treating people like objects is a good way to make sure not to.

Our second grounding concept, sexual citizenship, denotes the acknowledgment of one’s own right to sexual self-determination and, importantly, recognizes the equivalent right in others. Sexual citizenship isn’t something some are born with and others are born without. Rather, sexual citizenship is fostered, and institutionally and culturally supported. We do not use the term sexual citizenship as it is sometimes used, to call attention to the state’s designation of people as citizens or noncitizens, allocating rights and benefits dependent on sexual identity. Rather, we mean a socially produced sense of enfranchisement and right to sexual agency.16

Sexual citizenship focuses attention on how some people feel entitled to others’ bodies, and others do not feel entitled to their own bodies. As a social goal, promoting sexual citizenship entails creating conditions that promote the capacity for sexual self-determination in all people, enabling them to feel secure, capable, and entitled to enact their sexual projects; and simultaneously insisting that all recognize others’ right to self-determination. Sexual citizenship is a community project that requires developing individual capacities, social relationships founded in respect for others’ dignity, organizational environments that seek to educate and affirm the citizenship of all people, and a culture of respect. In contrast to sexual projects, where out of respect for diversity and the freedom of self-expression the role of public institutions should be limited, promoting sexual citizenship is a project in which the state has a fundamental role.

All but the most progressive American sex education consistently denies young people’s sexual citizenship—communicating, in the words of one of our mentors, the notion that “sex is a dirty rotten nasty thing that you should only do to someone you love after you are married.” Plenty of young people told us that they had had sex education, but that it was taught by a teacher who was mortified to be teaching it, or whose message was one of fear: of pregnancy, of sexually transmitted infections, of all the terrible things that sex could bring into their lives. Whether from school-based sex education, from their families, or from their religious upbringing, many students we spoke with had absorbed the lesson that sex was potentially terrible and most certainly dangerous. But in the United States today there’s likely more than a full decade between a young person’s first sexual experience and marriage. And that’s if they ever marry, which is decreasingly likely.17 It’s not that people are having sex younger; the average age at first sex, around 17 in the United States, hasn’t changed much for over four decades.18 If anything, young people today are having less sex, overall.19 What has changed significantly, however, is the age at which young people are getting married.20 In 1960 the average age at first marriage was twenty-three for men and twenty for women. Today, men first marry, on average, when they’re thirty, and women when they’re twenty-eight.21

Social policies that communicate that young people are not legitimate sexual citizens date back at least to President Reagan’s “Just Say No” approach, which was not just about drugs; the Adolescent Family Life Act of 1981, otherwise known as the “chastity” program, discouraged premarital sex.22 Abstinence-only programs enacted as part of President Clinton’s 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (known as “welfare reform”) teach “abstinence from sexual activity outside marriage as the expected standard for all school age children.” Federal support for abstinence-only-until-marriage (now rebranded as “sexual risk avoidance”) has ebbed and flowed to some extent with partisan shifts in power. The widespread belief among elected officials seems to be that it would be better if adolescents did not have sex at all; even a Democratically controlled Congress under President Obama maintained some funding for abstinence-only programs.23 Proponents of comprehensive, medically accurate, age-appropriate sex education have sometimes hesitated to directly challenge the framing of young people’s sexual activity as intrinsically bad, preferring a more health-focused middle ground that emphasizes the benefits of comprehensive sex education to prevent pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections.24

Analysis of nationally representative data shows a worsening landscape for sex education, with significant declines in the proportion of adolescent women in America saying that they had received formal instruction about birth control, about saying no to sex, about sexually transmitted diseases, and about HIV/AIDS, and significant declines in young men’s instruction in birth control.25 Fewer and fewer students are receiving sex education that covers topics such as the right to make one’s own reproductive decision, how to resist peer pressure, or how to use condoms.

In addition to the overall declines in delivery of key topics that would help cultivate sexual citizenship, some of the most disadvantaged are getting the least information. Only 6% of LGBTQ youth—those most at risk of assault—report that their sex education included information on LGBTQ topics.26 Young people growing up in poor families and in rural areas in the United States are less likely to receive comprehensive, medically accurate sex education.27 This is part of the normalization of educational inequality in the United States: some students experience K–12 education where they’re lucky to have adequate heat and air conditioning, while others are educated in places bursting with computers, AP classes, and arts options. Some of the students we spoke with revealed stunning ignorance about basic elements of sex and reproduction. One young woman recounted that no one had ever spoken to her about sex, other than to instill fear; as a result, she said, “I didn’t even know where my holes were.” If the goal is ignorance, the policy is a resounding success—but that sexual illiteracy reflects a denial of young people’s sexual citizenship, with a climate of shame and silence that are part of the social context of campus sexual assault.

The final piece of our conceptual framework is sexual geographies. This concept integrates the built environment into our perspective. Yes, we literally mean things like space and furniture, but also a lot more. Sexual geographies encompass the spatial contexts through which people move, and the peer networks that can regulate access to those spaces. Far more than many of us realize—and particularly in college settings—sexual outcomes are intimately tied to the physical spaces where they unfold. Put simply, space is inextricably intertwined with sexuality. It’s not just a backdrop, where certain behaviors are more likely to occur in certain places. Instead, space has a social power that elicits and produces behavior. Within the social sciences there’s an enormous amount of work that points to how space influences actions and interactions.28 Someone in a mosque will probably act differently than they will at their best friend’s house. We tap these insights to think about what might explain sexual assault, and how we could potentially address it.

Think for a moment about two young people flirting at a party. They both want some privacy. They’re not sure what more they want. Let’s say they both have roommates. It’s a pretty big request for one of them to text their roommate asking them to leave the room for an hour at, say, 2 a.m. It’s suddenly more awkward to head to that now-vacated space, chat for a bit, and then just leave. It shouldn’t be that way, but it is. Or, let’s say one of them has a single. In that room is a desk, a chair, a bureau, and a bed. To sit apart would be awkward. But sitting together means sharing a bed.

The physical landscape is a critical player in young people’s futures, and is intertwined with all kinds of inequalities. Think about being “stuck” somewhere more than an hour from home, with public transportation running sporadically and without the money to pay for a cab home, and feeling compelled to spend the night at someone else’s place, despite not wanting to. A wealthy student stranded the same distance from campus can open up a phone, click on an app, and be whisked safely back to the dorm, all because their parents have the capacity to pay that bill for them. Access to and control over space, like so many other things, isn’t equally shared. We refer to “geographies” in the plural, to indicate both the range of spaces that shape sexual interactions and the ways in which a student’s resources and social position affects their experience of the same space.

Space is a central dimension of institutional power, on campus and beyond, and power is central to understanding assault. The presence of roommates, the taken-for-granted idea that more advanced students should get better housing, including single rooms, and national Greek-life policies that ban sororities—women-controlled spaces—from throwing parties that serve alcohol, all are part of the campus sexual geography. These spatial dynamics—control, access, feeling at ease—are major players in sexual assault. To tackle this problem, we need to think about people, the communities they’re a part of, and how these can support sexual projects and citizenship. We also need to think about the landscapes and built environments that augment or moderate power inequalities, that support or deny projects and citizenship, and that remove or pose barriers to satisfying sexual lives.29 Students may arrive on campus clear about their own sexual projects, having grown to young adulthood in families and communities that help them understand themselves as sexual citizens—and yet once at school they navigate sexual geographies that produce vulnerability, and they encounter others who do not recognize their right to sexual self-determination, or for whom they are nothing more than a prop in the quest to realize a sexual project centered on accumulating experience, or prestige, or pleasure.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SEXUAL ASSAULT ACTIVISM, RESEARCH, AND POLICYMAKING

Understanding what to do requires that we recognize where we are, and how we got here—specifically, the interplay of advocacy, research, and policymaking around sexual assault. A complete history is beyond the scope of this book. Nevertheless, some context is essential to situate our work in relation to those shoulders we stand upon and to indicate ways in which our perspective is distinct from other, more common understandings. We also seek to recognize key insights that have slipped from center stage in recent decades.

Although the label that circulates in the policy world—“gender-based violence”—suggests that socially unequal relations between men and women are the primary form of inequality relevant to understanding sexual assault, a core message of Sexual Citizens is that it is only possible to make sense of campus sexual assault by looking at the intersection of gender with other forms of inequality.30 America’s history of organized public action on sexual assault reveals that racial inequality has always been central to understanding both the circumstances in which sexual assaults occur and the meaning of confronting that violence. In the 1860s, brave African American women testified before Congress about a gang rape by a white mob.31 Decades before she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man, Rosa Parks was organizing against sexual violence as a tool for racial domination. In 1931 she helped defend the Scottsboro Boys, nine young African American men accused of raping two white women on an Alabama train. In 1944, as the NAACP’s chief rape investigator, Parks stood by the side of Recy Taylor, who refused to be silent after being raped by six white boys in Alabama.32 Black women’s organized opposition to racialized sexual violence, grounded in an analysis of sexual violence not as a problem of individual pathology but as part of the social organization of society, laid a foundation for the civil rights movement, and for the kind of approach we take in this book.33

That work also paved the way for more public attention to sexual assault in the 1970s.34 In 1975 the term “date rape” first appeared in print, in Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, and the 1970s also saw the emergence of annual “Take Back the Night” marches, calling attention to violence against women in cities and on campuses around the world.35

The history of sexual assault on campus has been written primarily with a focus on women students being assaulted; until recently little attention has been paid to men’s assaults of other men, to say nothing of women’s assaults of men, or the experiences of LGBTQ students. This focus on women’s victimization by men is in part because men commit the vast majority of assaults, and women are overwhelmingly the people being assaulted. Coeducation and campus sexual assault are, for rather obvious reasons, intimately intertwined. By implication, the problem of campus sexual assault is likely far older than many realize. In 1833, Oberlin College was founded as the first coeducational institution of higher education in the United States, and by the end of the nineteenth century, around seventy percent of colleges were coed. We likely have readers in their sixties, seventies, and eighties for whom this book is not just sad, or thought-provoking, but also distinctly discomfiting, as they recall their own college days and reassess long-dormant memories of assault, or realize that they may have assaulted someone. But the ways in which those older readers understood sexual assault at the time they were in college was likely quite different. Writing the history of campus sexual assault includes tracing changing understandings of the very nature of the problem. Research led by Desiree Abu-Odeh, as part of SHIFT, found that when Columbia and Barnard’s campus newspaper, the Columbia Spectator, first began covering the topic in the 1950s, the focus was on a stranger coming from outside the gates.36 In Columbia’s case, student reporters wrote about the Black men in nearby Harlem, as a risk to the innocent white Barnard women. Gradually, other images would be layered onto this racialized view of a stranger lurking in the bushes: the athlete who drags a drunken woman behind a dumpster, the campus as a “hunting ground”; or even, as in the title of Peggy Sanday’s 1990 classic, Fraternity Gang Rape.37

Research recognizing the problem of campus sexual assault began as early as the 1950s. In 1957, the American Sociological Review published “an investigation of sexual aggressiveness in dating-courtship relationships on a university campus.”38 The modern era of campus sexual assault research began in 1985, with Ms. magazine’s publication of pioneering work conducted under the direction of Mary Koss.39 A survey of over 7,000 women students at thirty-five schools showed that one in four women had experienced rape or attempted rape, mostly by friends or intimate partners. What began as just a trickle of papers annually examining sexual assault among college students, mostly written by psychologists, behavioral scientists, and criminologists, became first a steady flow—dozens per year—and then a veritable flood since 2014, the recent period in which campus sexual assault has been a major focus of public discussion.40 The scholars producing this work reflected the core approach of their academic disciplines, concentrating on the individual attitudes, attributes, behaviors, and histories of those who either committed assault, or were themselves assaulted, and issues related to adjudication. We are interested in these individual factors, but our work responds to calls dating back two decades for analysis that examines the broader ecology of sexual assault.41

At least as influential as the scholarship and activism around sexual assault is the legal terrain. Three pieces of federal legislation from the 1970s through the 1990s have fundamentally shaped how we think about sexual assault, what institutions are required to do to address it, and how the federal government can be called upon to act: Title IX (passed in 1972, mandating gender equality in educational institutions); the Clery Act (passed in 1990, mandating reporting about campus crime), and the Violence Against Women Act (passed in 1994, as part of a broader crime bill).42 The federal government paid little attention to lowering the rate of sexual violence; instead, its focus was on the aftermath: adjudication, criminal justice responses, and services for survivors.43 In 2011 the US Department of Education fundamentally transformed the landscape for colleges and universities with a “Dear Colleague” letter. This letter, written to institutions of higher education, suggested that in failing to fully respond to sexual assault, colleges and universities could be violating Title IX. Because women were disproportionately experiencing assault, and assault was known to have significant life impacts, women were not enjoying equal access to educational opportunities.44 While most of the emphasis in that 2011 guidance continued to focus on the aftermath (standards for grievance, investigations, and adjudication, including evidence and representation), that more recent federal guidance included requirements for education and prevention. The impact of the “Dear Colleague” letter upon colleges and universities was profound. In the spring of 2014, the Obama administration released a list of 55 schools under investigation by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights for violations of Title IX related to sexual violence, later expanding that list to 304 investigations at 223 institutions of higher education. In September of 2014 the White House launched the “It’s on Us” campaign against campus sexual assault.45

Activists have seized upon this policy landscape. Students are using federal laws to advance claims that the administrative responses to sexual assault are generating a climate of gender inequality affecting women’s access to and experience of education. Many are demanding swifter justice for the victims of sexual assault, and harsher punishments for the respondents. The stakes are high: schools under federal investigation for potential Title IX violations, Columbia included, risk losing hundreds of millions of dollars in federal support: everything from subsidized loans for students to federal grant money for faculty researchers.

The focus isn’t just on what schools should do. Increasingly, both states and schools are creating policies to more precisely define how people must act for sex to be consensual. The most common of these policies is “affirmative consent,” which requires ongoing and explicit consent as a sexual interaction proceeds. Developed by student activists at Antioch College in the early 1990s, the idea was initially mocked, even in a 1993 Saturday Night Live skit, but its broader influence has been profound; hundreds of schools across the country now have affirmative consent policies, and it is enshrined in law for all people, on and off campus, in four states (New York, California, Illinois, and Connecticut).46 Frequently through online pre-orientation courses, college students today are taught that the absence of “no” does not mean that sex is consensual, and that the only way it can be is if both parties explicitly say “yes.” But as we’ll show, promoting affirmative consent is insufficient to prevent sexual assault.

While feminists have dominated activism around sexual assault, and psychologists have had the most influence upon scholarship, legal voices have weighed most heavily on the policymaking terrain. By implication, the questions asked center around law, legal procedure, and legal remedies. How should we investigate these cases? And how should we punish people? This focus reflects the power of feminist lawyers such as Catharine MacKinnon in mapping out sexual harassment, and by extension, campus sexual assault, as forms of discrimination, creating an institutional responsibility for redress that provides an alternative to engagement with the criminal justice system.47 And yet there is something of the 1980s and 1990s approach to criminal justice, with its emphasis on adjudication and punishment rather than prevention, and in the focus on an adversarial legal approach rather than a community-oriented one. The characterization of those who commit assault as sociopathic perpetrators and the portrayal of the greatest risk as coming from serial predators echo the 1990s “superpredator” conversation.48 Both are built on a sometimes racialized imagination about a predatory other. Our work stands in striking contrast to this, by suggesting that questions about race and campus sexual assault should focus on racial inequality and differences in power and status in specific campus contexts.

Unquestionably, there are “bad guys” out there who intentionally and violently seek to harm others through sex, both within the student body and outside of it.49 But thinking of men as predators and women as prey misses so much. It flattens women into passive victims in need of protection, renders invisible the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) students, who experience far higher rates of assault than their heterosexual peers, and provides little in the way of conceptual tools to understand, or even recognize, instances in which men are assaulted by women.50

FROM FEAR TO EMPATHY AND HOPE

Our analysis of the social dimensions of campus sexual assault suggests that in addition to focusing on predators, we need also to focus on ourselves. Until we look at how our society raises children, organizes our schools, and structures the transition to adulthood, we’re not going to make much headway. But if we are part of the problem, we can also be part of the solution.

The focus on fear—the old dangers of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, combined with the newly recognized dangers of campus sexual assault—reflects an underlying refusal to acknowledge young people’s sexual citizenship. It’s magical thinking to believe that young people can learn to put their bodies close to other bodies, safely and without anyone getting hurt, when for most kids the only message that they get from their parents is “not under my roof.”51 Most parents whose children want to learn to drive spend a great deal of time teaching them—talking about the rules of the road, how to drive defensively, how to protect pedestrians and cyclists. They don’t sit kids down, awkwardly explain the role of spark plugs in the internal combustion engine, and consider the job done. And with much younger children, parents and caregivers expend enormous energy helping them to move safely in the street. Don’t cross against the red, and walk facing traffic. On a bike, always wear a helmet, and ride single file, moving with traffic. It takes a lot of work to teach kids to move their bodies safely through the world. We know this about everything except, it seems, sex.52

This may be why there has been so little progress in actually reducing campus assault. No research that we have seen documents a substantial campus or population-level decline in rates of sexual assault, although several prevention interventions have demonstrated some level of efficacy.53 The lack of progress reflects, in part, a failure of imagination. What if, instead of scaring young people, we helped them grow into people who have satisfying intimate lives? With some states banning gender-neutral restrooms and others mandating LGBTQ-inclusive sex ed, there is substantial disagreement across the United States about the sexual citizenship of queer youth. The antipathy toward birth control, abortion services, and even the vaccine that prevents sexual transmission of the cancer-causing human papillomavirus, makes it clear that some people believe that it is morally necessary for unmarried heterosexual sex to have dire consequences. But who wishes a future of sexual misery on their children, or any child? It may seem foolish to argue that rather than taking on sexual assault prevention, a challenge at which society has largely failed, we should take on the much bigger task of promoting young people’s sexual citizenship. But that is exactly what we must do. And that means expanding the focus beyond adjudication, which has kept all eyes on that tiny proportion of assaults formally reported to institutions of higher education.54

OUR UNIQUE PERSPECTIVE

We are experts in overlapping and complementary fields. Jennifer is an anthropologist and professor at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. She’s spent her academic career studying gender, sex, intimacy, and health.55 She also has two sons whose time in high school and college coincided with her work on SHIFT, and so she thinks and writes with a very personal concern regarding the world that young men and women are growing up in. Shamus is a sociologist at Columbia University who has spent his career studying American elite communities, gender, inequality, and adolescence.56 Before we began this project we were not experts in sexual assault research; our prior research had been about the social production of gender and sexuality, rather than social pathology. We have brought a different perspective to an old problem, grounded in the research we have done on related topics, in our shared interest in gender and sexuality, and our expertise in ethnographic research. This book draws on all these aspects of our background, training, interests, and perspectives.

Our methodology (which is described in greater detail in the methodological appendix) involves talking to people, spending time with them in places that are meaningful to them, and observing them as they go about their day-to-day lives. For SHIFT’s ethnographic component, we led a team that conducted multiple-hour interviews with 151 undergraduates, describing their experiences before coming to college, their relationships with family and friends, their experiences with drugs and alcohol, and, most of all, their experiences with sex and sexual assault. As is typical with on-campus research, students were compensated for participation in ethnographic interviews and focus groups, as they were for the survey components of the SHIFT research.

We asked students why they pursued sex, what they wanted from it, how it fit into their lives, and what their sexual experiences were actually like. And rather than study every possible dimension of sexual misconduct, we focused intensively on sexual assault. By assault, we mean unwanted nonconsensual sexual contact; this includes rape and attempted rape, but also unwanted nonconsensual sexual touching. In this book we use the word “rape” to refer specifically to penetrative oral or genital assault. Rape is a legal term that we did not use in our data collection, for a variety of methodological reasons. But we use it in this book because it’s more direct than “nonconsensual penetrative sexual contact.” One of the lessons of our project is that assault is not one thing, it’s many different kinds of experiences, and “rape” clearly delineates one such kind of experience.

Across the interviews we heard many stories of sexual violence, stories that, for twenty-five of the students, took up to three two-hour interview sessions to tell. We look back on the students who talked to us and marvel at their extraordinary courage in sharing funny stories about the first time; tender ones about exploring their sexuality; terrifying accounts of rape; and heartbreaking stories of racial and queer victimization and abuse.

In addition to talking with individual students, we wanted to know how students talked about sex and sexual violence with one another. To do so, we ran seventeen focus groups of between eight and fourteen students. Some groups were all women, others were all athletes. We ran an LGBTQ group, a group of students of color, and a group of freshmen. These focus group discussions explored students’ shared ways of talking about sex, sexual assault, and consent. We observed that students were already educated about the importance of consent, but the rote answers they so expertly reproduced about the importance of “yes” bore little resemblance to the ambiguous realities of sex as they actually described it unfolding in their lives.

What people say is never the full story; what truly sets our work apart methodologically is the hundreds of hours of in-depth participant observation, conducted while students were socializing with one another—in their rooms, at parties, at the clubs and organizations that were so important to them.57 It’s not just our ages and bedtimes that precluded us from doing that part of the research: as faculty members at Columbia, socializing with our students would be awkward, intrusive, and unlikely to produce good data. As we learned from one attempt at bar-based participant observation that ended up misrepresented on page six of the New York Post, the best way to avoid misunderstandings was to draw a bright line.58 We attended public events like homecoming and basketball games, and spent time in public spaces, for example eating in the dining hall with students. But we didn’t go to places that were, or that students considered, “private.”

To gather data in such spaces, we hired five younger researchers with graduate training in anthropology, public health, and social work. Always identifying themselves as researchers and securing students’ permission, they spent hundreds of hours at fraternity parties, on athletics team buses, with religious student organizations, socializing at the cafeteria and at bars, in dorm rooms, and around the city with students as they lived their day-to-day lives.

We have taken many steps to protect the identities of students who participated in the research. This includes changing students’ names, hometowns, and identifying details, as well as some of their physical descriptions. If information is analytically important, we don’t change it. For example, when we talk about the unique experience of Black men navigating consent, all our examples are from Black men. Sexuality and gender identification are never changed. But we change other details to prevent classmates of those we interviewed, and students’ families and friends, from recognizing them. Importantly, all the stories of assault remain true to the experiences of students. Demographic and personal information might be purposefully inaccurate, but the description of the physical interaction adheres to what we were told.

The stories we recount are one-sided. With a few exceptions, we only know what one person told us about an encounter. If we were trying to figure out who was responsible, that would matter. But we’re not. We’re instead interested in how people experience their lives.

Part of that experience is the development of an identity. Our research included students with a wide range of sexual and gender identities. These gender identities included “male,” “female,” “queer,” “genderqueer,” “cisgender,” and “transgender,” and the sexual identities encompassed “gay,” “straight,” “bisexual,” “queer,” “polyamorous,” “asexual,” etcetera. Some readers may be confused by what all of these identities mean. What is the difference between queer and genderqueer? It is difficult to provide a precise definition because students used the same identity label in different ways. “Queer,” for example, is both a gender identity and a sexual identity. There were many students we spoke with who do not use the traditional gender pronouns of “he”/“him”/“his” or “she”/“her”/“hers,” instead preferring “they”/“them”/“theirs.” Throughout Sexual Citizens, we employ the pronouns, gender, and sexual identity terms that research subjects used for themselves.

In addition to using people’s own words to describe their identities, the ethnographic method favors rich detail over representativeness. To balance this, we triangulate our findings with two other sources of information. First and foremost is the SHIFT survey, led by Claude Ann Mellins, and developed by a faculty research team that included both of us, as well as Louisa Gilbert, John Santelli, Melanie Wall, Kate Walsh, and Patrick Wilson. The SHIFT survey, which was drawn from a random sample of the student body and which had one of the highest response rates of any campus sexual assault survey—over 66%—enabled us to situate ethnographic findings in relation to the more representative student experience.59 We also refer to the broader literature on sexual assault, which helped us see how our case of Columbia University compared with other campus contexts.

Although we refer to our field site as “Columbia,” the students in our research came from four distinct undergraduate institutions: Columbia College, Columbia School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, School of General Studies, and Barnard College. Columbia College is a coeducational liberal arts college. The School of Engineering and Applied Sciences teaches engineering and other applied scientific fields. General Studies matriculates joint-degree, nontraditional, and sometimes older students, from ballet dancers to veterans (in 2016 Columbia had 375 veterans enrolled as undergraduate students, far more than any other Ivy League school; Harvard, by comparison, had four).60 Barnard, just across the street on the west side of Broadway, is an entirely independent women’s college, with its own faculty, administration, policies, buildings, students, dorms, endowment, and campus culture. Each of these four institutions have distinct institutional cultures and other differences, which we do not discuss or use within our analysis. Students from all four schools all take classes together, and for traditional-aged college students the social life of the four schools is more or less integrated. The three coeducational colleges have nearly equal gender ratios, but because Barnard is all women, the gender ratio of the student body of the four schools taken together is closer to 60% women, 40% men.61 As women today make up more than 56% of all college and university undergraduates, this aspect of the campus landscape is not that unusual.62

The context of a private, highly selective, research-intensive, urban university is unquestionably very particular. Most US college students do not attend residential institutions, and most American institutions of higher education lack multi-billion-dollar endowments, accept far more than half their applicants, and have student populations that are, on average, far less wealthy. Still, the questions we ask and the ideas that shape our analysis can guide thinking much more generally. The overall dynamics we are interested in—the search to achieve one’s goals and connect with others—are a central challenge in everyone’s transition to adulthood. In a community college, boarding school, summer camp, or military institution, the same questions apply: how do the spaces to which people have access shape their interactions? How do people’s underlying objectives, and their capacity for empathy, shape the way that they interact?

We wrote Sexual Citizens to shed new light on how those interactions, and the underlying objectives and context, lead to campus sexual assault—and so, not surprisingly, this book is mostly about assault. We don’t say much about students’ academic experiences, internships, or research with faculty. Nor do we spend much time talking about students who don’t have sex, or students who are only having satisfying and consensual sexual interactions. Analysis of the SHIFT diary survey research, led by Patrick Wilson, suggests that there is a great deal of campus sex that students experience as enjoyable and consensual.63 Even if more than one in three women and nearly one in six men are assaulted by the time they leave college, that still means the majority of students do not experience assault. And the students who are assaulted can also have pleasurable and consensual sex. We tell some of these stories, yet our focus is primarily on the types of interactions we seek to prevent.

Victims’ rights activists, seeking to emphasize that assault is not normal, and that we should not tolerate it, often exclaim, “Rape is not sex!” And we agree—rape is not sex. Yet for three reasons it is vital to study assault in concert with sex. The first is that comparison aids understanding. Sometimes revealing the fundamental properties of something is easiest when we also look at what that thing is not. Comparing assault to sex helps us better understand both phenomena.

The second reason is more important. Notwithstanding the rare instances of a stranger jumping out from behind a bush to drag a victim away, or the “roofieing scenario” of being drugged at a bar, most campus sexual assaults begin as sexual interactions. Many involve sexual situations that are consensual, until they are not. Sometimes the whole interaction takes place with one person still thinking that it is sex, not assault. That’s what, “he said/she said” is often all about. In most cases we saw these to be sincerely held positions, even if we also found that there were plenty of signs that one person wasn’t okay with what was happening. Unquestionably, assaults happen that involve violence and physical force (analysis of SHIFT survey data found that among those who were assaulted, 35% of women students’ experiences and 13% of men’s involved physical force).64 But most assaults don’t involve force. And in order to create a context in which young people have sex without harming each other, it’s crucial to understand those pivotal moments when encounters change from being sex, to being assault.

The third reason is that by looking at sex and not just assault, we also see the times assaults didn’t happen. In students’ stories, there were plenty of situations in which one person conveyed that they wanted to stop—either changing their mind, or clearly expressing a limit that had previously not been spoken—and the sex stopped. We need to study these cases in order to understand what’s different about those evenings where heavy making out leads to a friendly goodbye—or even to an awkward goodbye—and those where it culminates in an assault. Why is it that sometimes people look at a sexual partner, see that they don’t seem okay, and stop and talk about it, rather than just pushing ahead?

Our framework of sexual projects, sexual citizenship, and sexual geographies provides insight into what is happening and serves as a guide for what to do about it. We’ve written Sexual Citizens primarily for parents—both those with young children and those with high school–aged ones headed off to college—and for young people themselves, who are about to go to college or are already there. We’ve also written it for policymakers, who we hope will look at assault in a new way, and work with their communities to create policies and programs based in empathy and hope, rather than judgment and fear. We hope that our conceptual framework will become part of a new vernacular for understanding both sexuality and sexual assault, one that can be used to improve the lives of young people for generations to come.