The case of the Counter-Jihad Movement

Gabriella Lazaridis, Marilou Polymeropoulou and Vasiliki Tsagkroni

Introduction

The central concept of populism is based on the assertion that we should place our trust in the common sense of the ordinary people to find solutions to complicated problems. Mudde (2007) explains populism as

an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, the pure people versus the corrupt elite, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volente general (general will) of the people

(2007: 543)

while for Betz (1998) and Eatwell (2000) the main belief behind populism is the idea of measuring social value in relation to individual social contribution. In other words, populism rejects the established system and supports the idea of the many (people) (see the Introduction chapter).

The definition of populism adopted for the purposes of this chapter is based on Albertazzi and McDonnell’s (2007) approach, where populism is: ‘an ideology which pits a virtuous and homogenous people against a set of elites and dangerous ‘others’ who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sovereign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity and voice’ (2007: 3). The populist discourse captured in this chapter focuses on the discourse of the ‘others’ by inter alia political parties, organisations and individuals (bloggers) that together construct the Counter-Jihad Movement (CJM). More specifically, in the case of the CJM, the ‘people’ is perceived as a homogenous and prominently defined group with ethnic and cultural characteristics, while ‘others’ are Islam and Muslims. In other words, the groups that line up to the CJM are unified by the belief that Islam and Muslims are posing a fundamental threat to the Western world. This is being supported by Huntington’s (1993, 1996) ‘The Clash of Civilizations?’ thesis, which was first published in an article in Foreign Affairs and later as a book. Huntington argued that, after the end of the Cold War, Islam would become the biggest obstacle to the Western domination of the world and that war will result from the irreconcilable nature of cultural tensions.

In order to more extensively understand the construction of the CJM and the reason it has managed to represent such a variety of actors, we turn to Laclau’s (2005a) work on populism and hegemony. In his work Laclau underlines that populism arises from political and social demands, which are addressed by an actor that manages to support and argue in favour of these demands and where ‘the people’ is not just an ‘ideological expression’, but rather a ‘real relation between social agents’ that establishes the unanimity of the group (2005a: 73).

Laclau’s (2005a) research focuses on criss-crossing the link between the ‘universal’ and the ‘particular’, where ‘particular’ refers to the actors/social groups and ‘universal’ is the understanding that the ‘particulars’ constitute more than simply the environment they operate within. ‘Hegemony’ for Laclau (2001) is ‘the type of political relation by which a particularity assumes the representation of an (impossible) universality entirely incommensurable with it’ and therefore the hegemonic link ‘presupposes a constitutive asymmetry between universality and particularity’ (2001: 5). In the case of the CJM, the discourse of the movement demonstrates a populist tendency through the ‘anti-Islamisation’ rhetoric (the ‘othering’ of Muslims) and appeals to the West (‘the people’). As extensively analysed in Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (2005), Laclau underlines that popular discourses divide the social space:

[T]here is no emergence of a popular subjectivity without the creation of an internal frontier. The equivalences are only such in terms of a lack pervading them all, and this requires the identification of the source of social negativity. Equivalential popular discourses divide, in this way, the social into two camps: power and the underdog.

(2005b: 38)

Thus, from simple requests, the demands transform into ‘fighting demands’ (2005b: 38).

Since the late 1980s, Europe has witnessed the rise in popularity of extreme and far right movements, groups and political parties predicated on racism and xenophobia, such as Fremskrittspartiet (Progress Party) in Norway and Denmark, Front National in France and the Defence Leagues around Europe, etc. However, the CJM has been one of the most challenging. The CJM has been referred to in some cases as a new form of fascism, in others as a new and distinctive movement in its own right; it broadly combines concerns regarding the threat of Muslim extremism with various political issues relating to immigration (Archer 2008). It has been noted as hateful and violent, but also a champion of the rights of sexual and religious minorities and a staunch defender of the right to free speech (see Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun 2013; Kudnani 2012).

The CJM consists of a loose collection of political parties, organisations and associated pundits united by their belief that they are witnessing an attempted Islamic takeover of the West. Frequently linked to the far-right anti-Islamic ideology, centring on xenophobia, racism or even as a form of fascism, the discourse of the CJM aims at raising awareness of problems related to integration and multiculturalism in Western societies. Despite the CJM’s heterogeneous form, all the social agents associated with the movement (such as political parties, organisations and bloggers) agree that Islam and Muslim immigration is an ongoing threat to Europe and, to a certain extent, to Western culture. The fear of the loss of cultural identity, associated with insecurity and an increasing number of immigrants/Muslim population, creates an encouraging environment for xenophobic and racist discourse. This strong discourse focusing different dimensions of Islam – e.g. social and cultural, often associated with discourse on terrorism and security – underlines a cultural hegemonic shift of the far right rhetoric of the CJM. Therefore, the hegemonic discourse in the case of the CJM argues in favour of the preservation of Western cultural identity against the Islamic threat – in other words, what we call a hegemony of the ‘West’ (and what it represents in terms of identities and values).

Referring to the description of CJM, Goodwin (2013) suggests that:

[W]ithin an amorphous network of think-tanks, bloggers and activists, the counter-Jihad scene incorporates the ‘defence leagues’ in Australia, Denmark, England, Finland, Norway, Poland, Scotland, Serbia and Sweden, groups such as Pro-Cologne and the Citizens’ Movement Pax Europa in Germany, Generation Identity in France, the ‘Stop the Islamization’ networks in Europe and the United States, the American Freedom Defence Initiative and the International Civil Liberties Alliance.

(Goodwin 2013: 3)

Although overall the CJM is characterised by hate speech and hate crime, it also adheres to a rhetoric on the right to freedom of speech. It operates primarily online and in this way is able to sustain a substantial presence. Feldman (2013), in his work ‘Comparative Lone Wolf Terrorism: Toward a Heuristic Definition’, argues that the emergence of a ‘new far right’ is focused on prejudice against Muslims and that jihadi Islamists have witnessed a perceptible spike online, whereas Titley (2013) and Kundnani (2012) examined the link between the CJM and the Anders Behring Breivik1 case, with Kundnani describing the Counter-Jihad’s narrative as more ‘compatible with terrorist violence than older forms of neo-Nazism’, but also highlighting that the narrative remains, in depth, the same and only characters have changed; the race war of neo-Nazism (white race identity) is now replaced by Muslims (representing multiculturalism) (Kudnani 2012: 5–6). The choice of Muslims as the main focus of the CJM for Betz (2013) is an outcome of political opportunism and the result of a strategic abandonment of anti-Semitic themes. Additionally, the media has played an important role in legitimising anti-Muslim views (Fekete 2001), along with the securitisation of migration and stringent migration policies and immigration controls in recent years (Kundnani 2012).

This chapter aims to emphasise the emergence of this hegemonic phenomenon, by analysing the discourses of online advocates and by providing a network analysis of the CJM. In this chapter, we first synthesise existing understandings of the wider CJM and offer an overview of Counter-Jihad discourse. We argue that online presence is a key characteristic of the CJM, and we enrich the understanding of CJM by looking at multi-spatial manifestations of the CJM, in both digital and physical places. Social Network Analysis (SNA) is employed to visualise and explain the social ties in the CJM-Network (CJM-N), based on data collected from the Counter-Jihad conferences that took place during the period from 2007 to 2013. Furthermore, the online discourse of the CJM is examined by means of data mining on Twitter and the official websites and blogs. We examine ways in which the CJM-N has been developed and the reasons for the level of distribution and decentralisation within it. The emergence and wider embrace of internet technologies has had an impact on the social connections and the social organisation of the CJM, as well as the ways it communicates and distributes information. SNA, in this respect, demonstrates that the claimed ‘equal connectedness’ between the CJM-N participants and the empowering of the internet for the CJM discourse diverges from reality. In fact, there is a strong decentralisation of the CJM and clustering around certain nodes.

The historical and social context of the CJM

Strengthened by the attacks and events following 9/11, a strong anti-Muslim climate began to emerge. According to Kundnani (2012), the events that followed 9/11 circulated a new form of identitarian narrative, a ‘Counter-Jihadist’ narrative, where the idea of the defence of national identity is replaced by the ‘idea of liberal values, seen as civilizational inheritance’ (2012: 6). Including liberal ideas such as women’s rights or human rights, as Garland and Treadwell (2010) notice while examining the EDL’s case, is a tactic that places groups close to the CJM in a moderate status in contrast to Islam, which is tinted with an extremist and negative essence. In this respect, it is Islam that poses a threat to European identity, perceived of as simultaneously an ‘alien culture and an extremist political ideology’ (Kundnani 2012: 6); multiculturalism is perceived of as empowering the danger of the Islamisation of Western societies.

Nevertheless, the CJM narrative has managed to motivate organisations, think tanks, bloggers, street movements, political parties and individuals, creating a global network facilitation. One of the first organisations of the CJM is the 910 Group; this was founded in 2006 and is part of the Centre of Vigilant Freedom (CVF) organisational network, which aims to protect ‘liberties, human rights, and religious and political freedoms [that] are under assault from extremist groups who believe in Islamist supremacy’.2 Self-portrayed as a ‘facilitator of worldwide communication’ and mutual determination against the Islamisation of the West, the network also includes the Counter-Jihad Europa website; its primary content includes papers on Counter-Jihad topics – e.g. human rights and civil liberties, Islamisation, imposition of the Sharia and the International Civil Liberties Alliance – a project of the Center for Vigilant Freedom. The formation of 910 Group was announced by Baron Bodissey (real name Edward S. May)3 on the Gates of Vienna (a principal blog of the CJM since 2004):

The group’s intent is to gather together a lot of the strands of the counter-jihad and anti-PC resistance, in order to form a decentralized ‘network of networks’ with a global reach. No board of directors. No hierarchy of command. It’s simply an affiliation of like-minded people, sharing information and planning proactively to reframe the concept of the current war and rise up to help defend the West.

(Bodissey 2006a)

The ‘Stop the Islamisation’ network began in Denmark in 2005 by Anders Gravers and Michael Jensen and soon expanded in other countries across the world. Stop Islamisation of Europe (SIOE) was launched at the UK and Scandinavia Counter-Jihad summit, as ‘an action group determined to prevent and reverse the implementation of sharia law in Europe’4 that brings together people from all across Europe aiming to avert Islam from gaining leading political power in Europe. Branches of the network have been launched in Russia, England, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, Poland, Romania, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Faroe Islands, Italy, Serbia and Sweden and similar ones have been founded in the USA and Australia.5 In 2012, the umbrella organisation of Stop Islamisation of Nations (SION) was brought together, led by Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer. Since then, SION has participated and organised conferences and events along with allied groups of CJM across the world and has become one of the leading organisations in CJM.

International Free Press Society (IFPS) is another umbrella organisation for the network of ‘Free Press Societies’ at the international level. The initiative, like in the case of SIO, originated in Denmark, where in 2009 the Danish Free Press Society was first presented and its main purpose has been to defend the right to free speech. Similar to the case of SIO, the IFPS Board of Directors includes popular names within the CJM, such as Bat Ye’Or, Barron Bodissey (Gates of Vienna), Robert Spencer (Jihad Watch), Mark Steys, Paul Weston (Liberty GB) and Paul Beliën (The Brussels Journal), among others.6

The International Defence Leagues, offshoots of the English Defence League launched in 2009, is a network of street movements opposing the Islamisation of Western societies and campaigning against Sharia law. The Defence League groups participate in demonstrations across Europe and representatives of the groups can be found among the participants of the Counter-Jihad conferences (2007–2013) and events – e.g. demonstrations organised by the CJM.

What becomes clear when looking at the organisation of these networks is a familiarity with the people participating in key roles, such as Robert Spencer, Baron Bodissey, Jean-Michel Clement, Geert Wilders, Tommy Robinson and Elisabeth Sabaditsch-Wolff. Most of them are active in the blogging community – e.g. Gates of Vienna – and their work is often being hosted on the CJM organisations’ websites and online platforms – e.g. The Brussels Journal, which is a project: ‘set up by European journalists and writers to restore three values that are so lacking in the so-called “consensus-culture” of contemporary Europe: Freedom, the quest for Knowledge, and the Truth’.7 When looking at the data from the Counter-Jihad conferences (2007–2013), many of these key people appear in the list of participants. Having said that, as shown in the analysis that follows, there is a significant change over the years amongst the people participating, although the majority remain active in the CJM.

In June 2009, an entry on the Gates of Vienna blog suggested an application of a distributed network to safeguard and guarantee the growth and prosperity of the CJM. More specifically, Baron Bodissey, in the entry entitled: ‘Building a Distributed Counterjihad Network’, addressed the need for networking with people of the CJM and the way it could contribute to the creation of an international Western resistance to the Islamisation of Western societies (see Bodissey 2009a). In essence, the participants/members in the CJM want to be presented as a distributed network of inter alia political parties, organisations, movements, think tanks, bloggers and experts driven by the belief that an attempted Islamic takeover of the West is taking place and is using the Internet in order to organise and conjoin its multi-national anti-Islamic movement. Websites8 such as Gates of Vienna and The Counter Jihad Report, bloggers such as Pamela Geller, Robert Spencer and Aeneas, groups such as the 910 Group (later named the Centre for Vigilant Freedom), but also think tanks such as the International Free Press Society and the David Horowotz Freedom Centre are all members of the CJM. Over the last few years, certain international ‘umbrella organisations’ such as Stop Islamisation of Nations (SION) have been launched, which, among others, include defence leagues – e.g. EDL – but also their ‘allies’ in the US (Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun 2013: 3).

The links that construct the CJM have become more apparent after a series of meetings, at which members of the CJM and other groups have made joint appearances, such as the first Worldwide Counter-Jihad Initiative, the First Annual Global Counter-Jihad Rally in Stockholm on August 2012, in which representatives from inter alia Stop Islamisation of Nations (SION), Stop Islamisation of Europe (SIOE), English Defence League (EDL), Norwegian Defence League (NDL), Q Society Australia and numerous allied groups participated (see Geller 2012). As Pamela Geller stated, the conference

… heralds the launch of a worldwide counter jihad alliance. Freedom fighters from Europe and America, as well as India, Israel, and other areas threatened by jihad, will at last be working together and forming a common defence of freedom and human rights.

(Geller 2012)

Even before this, in 2007 in Brussels, The Centre for Vigilant Freedom organised a conference aiming to gather together writers, academics, activists and politicians working on Counter-Jihad initiatives across Europe. The purpose of the conference was to create a ‘European network of activists from 14 nations to resist the increasing Islamisation of their countries’.9 Similar conferences took place over the following years: in Vienna in 2008, Copenhagen in 2009 and Zurich in 2010.

In 2006, the 910 Group (later to become Center for Vigilant Freedom) argued that the blogosphere has the power to affect government decisions and policies. Baron Bodissey – a key personality in the CJM, the Center for Vigilant Freedom and who runs the blog Gates of Vienna – in his post ‘The Emperor is Naked’ in 2006 suggested that in order to develop and promote the policies of the CJM, it requires a web-based anti-Islam activist group with a physical and digital presence. Physical, meaning organising annual conferences and events, and digital, meaning through activity on blogs, such as publishing articles and engaging in social media – e.g. Twitter and other online platforms that were used for the benefit of the CJM.

I’ve said repeatedly that, if we want to win this war, we need to take back the culture. In order for that to happen, the organs of mass communication will have to change. The new media – of which this blog is a micro-scopic piece – will eventually supplant the old ones.

(Bodissey 2006b)

Discourses of the CJM and the threat of Islamisation

In a document entitled ‘The Counterjihad Manifesto’, published on the Gates of Vienna, the editor, Baron Bodissey, described Islam as:

above all a totalitarian political ideology, sugar-coated with the trappings of a primitive desert religion to help veil its true nature. The publicly stated goal of Islamic theology and political ideology is to impose the rule of Islam over the entire world, and make it part of Dar al-Islam, the ‘House of Submission’.

(Bodissey 2009c)

In the same document, Baron Bodissey presented the goals of CJM to be:

- 1 To resist further Islamisation of Western countries by eliminating Muslim immigration, refusing any special accommodations for Islam in our public spaces and institutions, and forbidding intrusive public displays of Islamic practices.

- 2 To contain Islam within the borders of existing Muslim-majority nations, deporting all Muslim criminals and those who are unable or unwilling to assimilate completely into the cultures of their adopted countries.

- 3 To end all foreign aid and other forms of subsidy to the economies of Muslim nations.

- 4 To develop a grassroots network that will replace the existing political class in our countries and eliminate the reigning multicultural ideology, which enables Islamization and will cause the destruction of Western Civilization if left in place.

And he added:

We are a loose international association of like-minded individuals and private organisations. We all share the overriding goals described above. We are non-partisan, and welcome members from any political parties who share those same goals, and who also demonstrate a strong commitment to the humane democratic values of the West.

We are Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs, Baha’is, ex-Muslims, agnostics, and atheists.

We live in Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA.

We are the Counterjihad.

(Bodissey 2009c)

As mentioned in the previous section, Kundnani (2012) argued that academic interest in the CJM has emerged after Anders Behring Breivik’s attacks in 2011, which resulted in the death of seventy-seven people. In Breivik’s lengthy manifesto, entitled 2083: A European Declaration of Independence, the author defines his goal as to ‘free indigenous peoples of Europe and to fight against the ongoing European Jihad’ (2011: 1436). What is noticeable in Breivik’s manifesto is that there is a significant number of quotes taken from bloggers and members of the CJM – e.g. the Free Congress Foundation, Robert Spencer and Bat Ye’Or – all of which develop arguments and theories on the threat of Islamisation in Europe (Kundnani 2012). Characteristically, Breivik describes multiculturalism as the ‘root cause’ of the ongoing Islamisation of Europe and states that there is time pressure to prevent Western societies being overwhelmed demographically by Muslims.

Ensuring the successful distribution of this compendium to as many Europeans as humanly possible will significantly contribute to our success. It may be the only way to avoid our present and future dhimmitude (enslavement) under Islamic majority rule in our own countries.

(Breivik 2011: 8)

Rejecting multiculturalism is essential in the CJM. Fjordman (real name Peder Are Nøstvold Jensen), in a post entitled A European Declaration of Independence (a title Breivik borrowed for his manifesto), in 2007 commented:

Multiculturalism has never been about tolerance. It is an anti-Western hate ideology championed as an instrument for unilaterally dismantling European culture. As such, it is an evil ideology bent on an entire culture’s eradication, and we, the peoples of Europe, have not just a right, but a duty to resist it and an obligation to pass on our heritage to future generations.

(Fjordman 2007)

By recognising this as ‘a duty’, Fjordman perceives of it as part of a deontology rather than an ideology and therefore addresses multiculturalism on ethical grounds. Additionally, when Bodissey underlined that ‘we’ are people of different religions and this is our ‘common’ background, then these deontologies become more coloured with religious beliefs and, therefore, morals. Having said that, what becomes clear from this observation is the thin red line in the hegemonic discourse of the CJM between what is ethical and what is moral (deontology versus morality), with an argument based on discourse related to Muslims versus other religions and primitivism versus Western culture. Said (1978) stressed Orientalism as an understated and tenacious Eurocentric prejudice against Arab–Islamic peoples and their culture, in which ‘us’ versus ‘them’ is often used to describe the cultural differences between the West and the East. About contemporary Orientalist stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims, Said (1980) said:

So far as the United States seems to be concerned, it is only a slight overstatement to say that Moslems and Arabs are essentially seen as either oil suppliers or potential terrorists. Very little of the detail, the human density, the passion of Arab–Moslem life has entered the awareness of even those people whose profession it is to report the Arab world. What we have, instead, is a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world, presented in such a way as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression.

Islam and, by extension, Muslims, in the case of the CJM, become a dangerous threat; and ‘the other’ becomes ‘the other other’, which raises issues of security and safety for European and Western societies. Therefore, the populist rhetoric that is adopted relegates the ‘other other’ to ‘the category of cultural and even racial infrahumanity’ (Aradau and Van Munster 2009: 73–83).

Nation and national identity along with an ethnic and religious homogeneity are seen as in need of protection from any threat that challenges the ‘imagined’ cultural homogeneity of Western societies. This perception points to a form of cultural nationalism, where ethnicity is defined in terms of inter alia a shared culture, language and history, and in which the European and Western culture in general should be protected by encouraging and promoting policies and measures that would control immigration from Muslim countries, but also empower policies geared towards wiping out Islamic extremism. By supporting the ban on mosque construction and campaigning in favour of prohibiting Muslim immigrants from entering Europe, both of which are signs of xenophobic, racist and authoritarian attitudes, the CJM could be described as a far-right cultural nationalist movement fomenting concerns about Islamic extremism (Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun 2013).

In this cultural war, ‘we’ share the same cultural values and ‘they’ represent a homogenised and hostile ‘against us’ Muslim world, determined to triumph over the West; ‘Europe’ represents values such as tolerance, equity and freedom of speech and ‘Islam’ is Europe’s opposite. In this sense, the cultural differences highlight a point of ‘superiority or inferiority, modernity or backwardness’ (Carr 2006: 14), and the only way for Muslims to be accepted is if they cast-off ‘their’ Islamic culture and convert to ‘our’ values (Kundnani 2012). Similar to prominent views in the far right family, for the CJM, Muslims appear to be the scapegoats that pose a threat to our national and cultural identity.

In the conspiracy theory surrounding the Counter-Jihad narrative, Islamisation, in essence, is perceived as ‘the process by which the supremacy of Islam is taking place by whatever means Muslims and their allies use’.10 Muslim immigrants pretend to be moderate by hiding their key purpose, which is the imposition of Sharia law, and suppress the free speech and all of this with the aid of their allies, the corrupted and established political elites (Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun 2013: 41–43), who allow them to launch Mosques and cultural centres that Ye’Or (2005: 36) comprehends as influencing the political life of host nations. Some aspects of this conspiracy theory is presented in the extended report of HopenotHate, written by Mullhall and Lowles in 2015 and entitled ‘The Counter-jihad Movement; Anti-Muslim Hatred from the Margins to the Mainstream’. In the report, it is underlined that under this ‘conspiratorial mindset’, evidence is ignored and events are generalised into an ‘epidemic’ – e.g. the theory that purchasing halal meat provides funds to terrorist groups, an argument used by Counter-Jihad groups, such as Liberty GB in the UK (Mullhall and Lowles 2015: 28). A similar argument that is put forward is that, in the process of Islamisation of Western societies, there is the perception of imposition of Islamic traditions and the creation of Islamic no-go places, along with the removal of Christian and Jewish symbols from the public sphere (see Sennels 2011). In this view, Europe is portrayed powerless and helpless, facing ‘cultural extinction’ under the threat of an instant ‘campaign of Islamisation’, which will lead to a so-called ‘Eurabia’ – an Islamicised oppressed Europe to the Arab world (Carr 2006). A critical perception towards Islam and Islamic extremists was also addressed by Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, who highlighted in her work The Rage and the Pride the tolerance of Europe towards Islam and noted that Europe is no longer Europe but ‘Eurabia’:

It is ‘Eurabia’, a colony of Islam, where the Islamic invasion does not proceed only in a physical sense, but also in a mental and cultural sense. Servility to the invaders has poisoned democracy, with obvious consequences for the freedom of thought, and for the concept itself of liberty.

(Varadaraja 2005)

The term ‘Eurabia’ was broadly introduced by Bat Ye’Or (real name Gisell Litmann),11 an Egyptian-born British citizen and key figure in the CJM living in Switzerland in her book Eurabia: the Euro-Arab Axis, published in 2005. Ye’Or (2005) describes jihad as a political force that dominates and, even in some cases, extinguishes the once powerful Judeo-Christian centres around the world; she argues that evidence of such a claim could be detected in the 9/11 and 3/11 attacks and the disclosure of an established jihad terrorist network that shares a culture of hatred and aversion toward ‘infidels’ and runs a ‘continuous religious war’ (Ye’Or 2005: 30–34). In Ye’Or’s (2005: 265) analysis, European civilisation evolved from a Judeo-Christian civilisation to a ‘civilisation of dhimmitude’. Originated from the Arabic word ‘dhimmi’, dhimmitude addresses dominated, non-Muslim individuals that ‘accept the restrictive and humiliating subordination to an ascendant Islamic power to avoid enslavement or death’ (Ye’Or 2005: 9), where countries obedient to Muslim rulers are characterised by ‘passive submission to intellectual censorship, insecurity, internal violence, and even terrorism’ (Ye’Or 2005: 265).

Ye’Or’s Eurabia theory has seemingly gained a foothold amongst Counter-Jihad activists and has been expressively referenced by Anders Behring Breivik (Norwegian far right terrorist), Melanie Phillips (journalist and columnist for The Times), Mark Steyn (Canadian political commentator and author) and Niall Ferguson (British historian), among others (Fekete 2012). Niall Ferguson, for instance, mentioned that ‘a youthful Muslim society to the south and east of the Mediterranean is poised to colonise – the term is not too strong – a senescent Europe’, whereas Mark Steyn highlighted that ‘immigration and high birth-rates could mean that Muslims will make up 40 percent of Europe’s population by 2025’ (Underhill 2009). However, despite the fact that Europe’s Islamic population appears to have increased over the last few decades, there is little evidence to prove that Europe is becoming primarily Muslim or that there is any intention from the Muslim communities to spread beyond their margins, evidence that strengthens the argument that Eurabia is, and will remain, a conspiracy theory without fertile grounds.

Visualising the CJM network

Baron Bodissey (2009a), in his article ‘Building a Distributed Counterjihad Network’ published online on the blog Gates of Vienna, has argued for a decentralised, distributed network (see also Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun 2013: 22). The term ‘network’ appears to be employed to characterise the CJM for various reasons. Baron Bodissey, who appears to portray himself as a philosophical and yet authoritative figure within the CJM, asserts that the CJM functions as a network where power is distributed and not expressed by individuals or smaller groups, but rather by all network agents. This definition assumes a sense of equality in social relations.

As stated above in this chapter, the primary characteristic of the CJM-N is the common anti-Islam ideology that extrapolates the destruction of multiculturalism and the promotion of Western values and, by extension, culture. In the CJM-N, homophily – the similarities that allow connections between network agents – is concentrated primarily in the aforementioned common ideology. In terms of locality, the network is geographically dispersed. This dispersion is enabled by the use of the internet as a non-geographically localised locality that affords connections between network agents that reside in various countries worldwide.

In general, accounting for network agents is a challenging task, particularly because networks are dynamic and may change at any given moment. In the case of internet-supported networks, network participation does not require direct action. For example, a network participant may choose to be a ‘lurker’ of online discussions and just read the messages without interacting (see Bishop 2012). Similarly, the extent of the action can be different. Certain network agents may be posting original Tweets, whereas others may choose to re-Tweet others’ messages.

The CJM-N has digital and physical presence. Its online presence can be first observed in blogs that are collectively written by various network agents. Second, it is observed in social media. There seems to be a preference towards Twitter as the primary social sharing platform that the CJM-N agents use. For example, the Twitter account of the Gates of Vienna (@gatesofvienna, user #84324670) features 13,145 Tweets since its launch in 22 October 2009, has 5,320 followers and posts updates on a daily basis (results collected via Twittonomy on 15 December 2015). In comparison, the equivalent page on Facebook (Gates.of.Vienna) has 2,270 likes, but has not been updated since 30 May 2015. Finally, in recent years more websites have emerged, especially from organisations close to the CJM’s values – e.g. ACT! for Canada and ACT! for America, both organisations promoting national security and defeating terrorism. The CJM-N has organised various events and conferences across its networked countries. There have been seven annual conferences (Brussels, Vienna, Copenhagen, Zurich, London, Brussels and Warsaw) and also other events, such as: demonstrations like the one in 2007 by the Pro Köln group in Cologne against a mosque or in 2009 in London by SIOE outside Harrow Mosque and the Patriotic Europeans Against Islamisation of the West in 2014 in Dresden; meetings like the Vigilant Freedom Britannia Meeting in 2008 by Aeneas and the Center for Vigilant Freedom; and also other conferences, such as the Facing Jihad conference in Jerusalem in 2008, the Defeat Jihad Summit 2015 by the Center for Security Policy in Washington in the US and the ACT! for America national conference also in Washington.

The rest of this chapter will look at how ideologies are associated with, and expressed, through the CJM-N. To do so, seven datasets were compiled and used. These datasets depict the delegates of the annual CJM conferences in the period from 2007 to 2013. The reason for this selection is that there is a clear representation of both the physical and digital presence of the CJM. The delegates are directly associated with various online resources (be it blogs or webpages of organisations) and also their participation at the conferences accurately evidences the offline presence of CJM-N (which would otherwise be difficult to prove unless one had conducted interviews with them; we were unable to do that, because they all declined to be interviewed).

Seven figures of the CJM-N in each conference year have been produced and analysed using social network analysis. A network is dependent on nodes and connections between them, the edges. The produced CJM-N figures are one-mode networks where agents are a set of nodes that are similar to each other and the edges represent their relations. Conference delegates represent the nodes and the connections were deemed to exist based on the role and, therefore, assigned category of every network participant. The primary categories that have been taken into consideration are: (a) bloggers, (b) politicians, (c) organisations, (d) authors, (e) activists and (f) journalists. A category that requires further explanation is that of the organisations. This includes organisations, but also think tanks that focus their work against the threat of Islamisation, such as the Stop Islamisation Network or the International Free Press Society. Several agents have various roles in the CJM-N – for example, Baron Bodissey is a blogger and Director of the Center for Vigilant Freedom; Tommy Robinson is a politician and activist; and Jean-Michel Clément is an activist and founder of L’Alliance FFL – and these multiple identities produce cross-categorical connections between nodes and reveal associations between the CJM-N.

For the visualisation of the CJM-N, Gephi (v. 0.8.2 beta) – the free/open source visualisation software tool – was employed, due to its simplicity for such kinds of one-mode networks. Gephi offers a range of statistical tools employed for SNA, such as node ranking by various parameters and built-in layout algorithms. The force-based algorithm ForceAtlas2 was used for the layout of the CJM-N. ForceAtlas2 supports a ‘spring-electric’ layout using the repulsion formula of electrically charged particles (Fr = k/d2), where Fr is the repulsion force, k is a constant and d is the distance, and the attraction formula of springs (Fa = –k∙d) involving a constant k and the geometric distance d between two nodes (Jacomy et al. 2012). In this layout, distance between nodes is relative and depends on forces of attraction and repulsion between the nodes. In ForceAtlas2 the developers’ idea was to bring nodes with less edges closer to very connected nodes (Jacomy et al. 2012) and to prevent disconnected clusters from drifting away from the network using the attribute of gravity, which attracts nodes to the centre of the spatialisation space (Jacomy et al. 2012).

The current research analyses two characteristics of each in the CJM-N: (a) betweenness centrality – i.e. how often a node falls along the shortest path when the connection of two other nodes act as a hub/how influential this node is to the network; and (b) modularity, a community tracking algorithm that identifies communities (clusters) in a network. In the case of closed networks where all nodes are connected, closeness (average distance from a node to all other nodes in the network) has been calculated to trace the significance of a node. Node ranking (size of nodes) represents each node’s betweenness centrality. The shades of grey depict the various formed communities within each network.

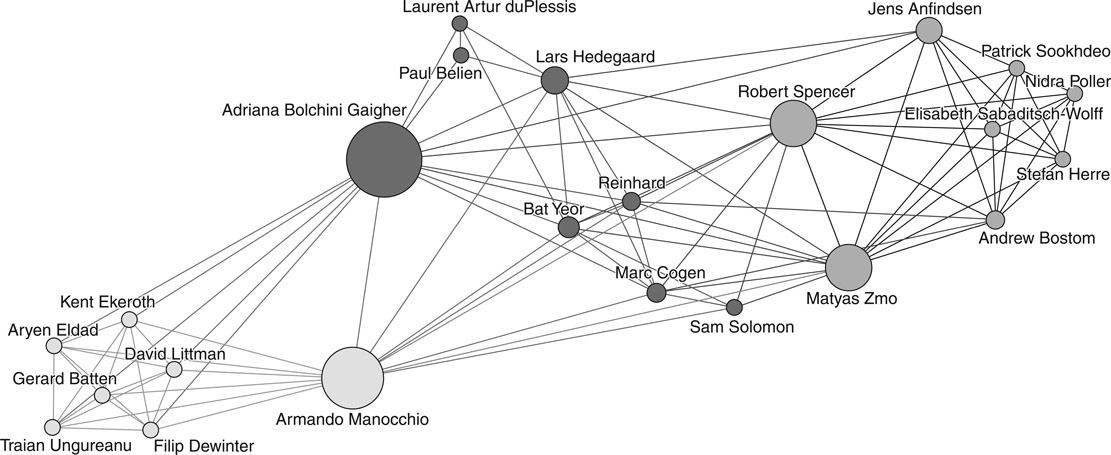

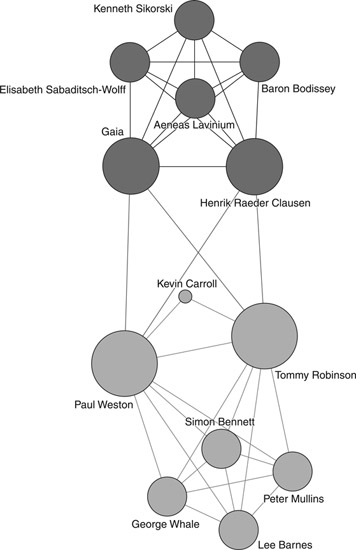

CJM-N Brussels 2007 (23 nodes, 96 edges)

The CJM conference in Brussels brought together seventy organisations and individuals in order to ‘create a European network of activists from fourteen nations to resist the increasing Islamisation of their countries’.12 Among the keynote speakers and participants was author Bat Ye’Or, blogger and author Robert Spencer, Director of the Institute for the Study of Islam and Christianity Patrick Sookhdeo, but also politicians like Gerard Batten from UKIP, Kent Ekeroth from Sweden Democrats, organisation representatives like author, journalist and President of the Free Press Society Lars Hedegaard and journalist and President of Observatory of Italian and International Law and director of the online magazine Lisistrata and member of PSI Adriana Bolchini Gaigher and bloggers like Elisabeth Sabaditsch-Wolff and Andrew Bostom.

The modularity algorithm has distinguished three communities (Figure 5.1; modularity: 0.36) with two primary hubs (Adriana Bolchini Gaigher and Armando Manocchio). Additionally, there are 2 equal nodes in the third community (Robert Spencer and Matyas Zmo). While looking at how the network is distributed in the case of the Brussels 2007 conference, some questions emerge: were these people significant at the time? What did they do in the CJM? Is there a node that was supposed to be more significant, but is not shown as such in the network? Andriana Bolchini Gaigher, Robert Spencer and Lars Hedegaard are well known and significantly active members in the CJM-N, promoting the ideas against Islamisation not only via their personal contributions – e.g. blogs and organisations – but also participating and collaborating at an international level. Armando Manocchio’s and Matyas Zmo’s presence centre it more towards a national level, with no further noteworthy participation in the CJM-N. What is worth noticing is that Baron Bodissey did not participate actively in the conference and that explains his absence from the network, despite his strong presence online and the fact that the Center for Vigilant Freedom organised and sponsored the whole event. Nevertheless, the data from CJM Brussels 2007 presents a very well-connected network – a closed network where all edges are connected at least once, with a substantial level of distribution among the participants. This is also explained by the variety of backgrounds of the attendances – e.g. country and affiliation and the high number of participants and popularity of the event.

CJM-N Vienna 2008 (10 nodes, 12 edges)

Table 5.1 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Adriana Bolchini Gaigher |

Italy |

58.263 |

| 2 |

Armando Manocchio |

Italy |

28.83 |

| 3 |

Matyas Zmo |

Czech Republic |

29.468 |

| 4 |

Robert Spencer |

US |

29.468 |

| 5 |

Lars Hedegaard |

Denmark |

11.591 |

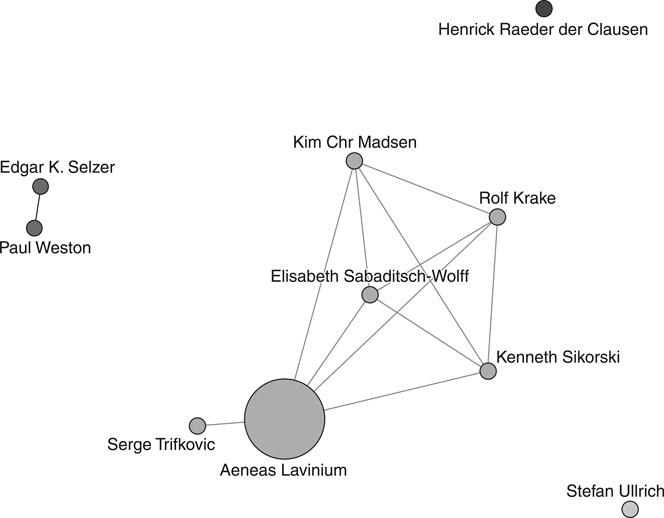

The Counter-Jihad conference in 2008 was held in Vienna, with author of anti-jihad books Serge Trifkovic as the keynote speaker. Other participants included bloggers, authors and activists from several European countries. The conference’s

form was more like a working meeting focusing on ‘Defending Civil Liberties in Europe’ and aiming to ‘move the center of gravity for our activities out of the United States and into Europe itself, among the people who will bear the brunt of Eurabia and who thus have the greatest incentive to resist it’ (Bodissey 2008). Aeneas is the primary hub and belongs to the community of bloggers. The analysis shows that the rest of the numbers do not matter, as they are zero and point to a not well-connected network.

Table 5.2 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Aeneas Lavinium |

UK |

4 |

| 2 |

Edgar K. Selzer |

Austria |

0 |

The modularity algorithm in this case shows four communities, most of them isolated (Figure 5.2; modularity: 0.153). Aeneas’ node can be explained due to his presence in the CJM-N as one of the key people in the blogging community. The cluster of the network of this conference, especially in comparison to the one held in Brussels the previous year (2007), could be explained due to low participation and also the lack of variety in participants and the fact that a significant number of the participants in 2007 did not participate in 2008. Additionally, it appears that the conference in 2008 did not manage to attract the attention of the audience and raised questions and concerns on how a distributed network could be planned and where it would be most effective (see Bodissey 2008).

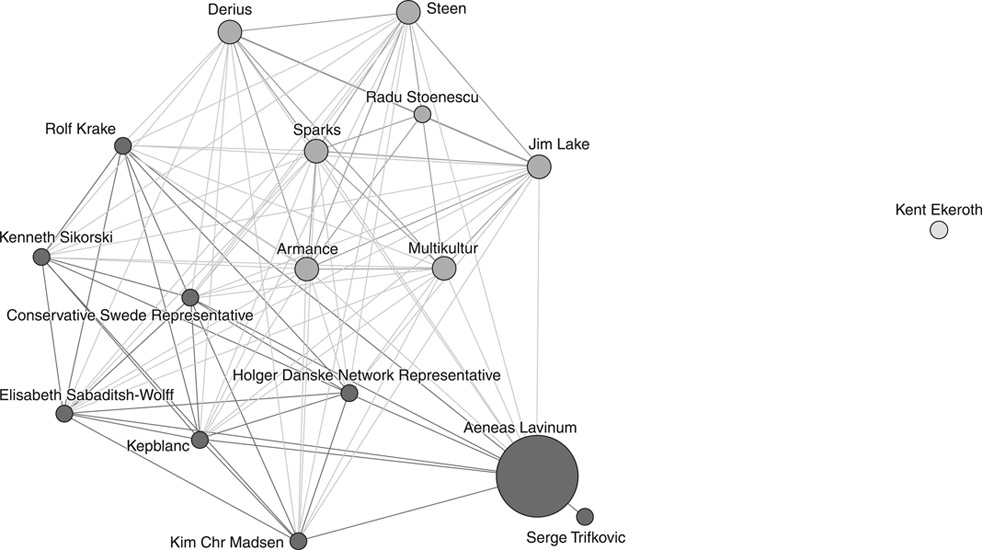

CJM-N Copenhagen 2009 (17 nodes, 98 edges)

Following the conference in Vienna the previous year, the CJM conference took place in Copenhagen in 2009, focusing on ways to support and develop the network of the CJM. Formed again as a working meeting, the presentations and key speakers emphasised various aspects of organising the CJM network in Europe and North America, but also discussed actions to be taken in order to make the CJM more effective, including demonstrations, raise awareness efforts and legislative initiatives. Additionally, Baron Bodissey announced that CVF had been merged into the International Civil Liberties Alliance (ICLA), which identified as ‘network facilitators’; he argued that: ‘our goal is to bring different groups and sub-networks into contact with one another, enhancing communication and improving the overall coordination of Counterjihad activities’ (see Bodissey 2009b). The conference was deliberated as a success, able to form a decentralised network of individuals and organisations to come together and collaborate in an international effort under a common goal. Similarly to Table 5.3, the first node is a primary hub, Aeneas, and the rest of the nodes (2–5) have the same betweenness centrality, something that does not place them in a hierarchical scale.

In the case of Copenhagen 2009, there are three communities (Figure 5.3), with Kent Ekeroth as the only politician participating and therefore a standalone node/community (modularity: 0.007). The participation and variety of this conference is considerably different from the one in Vienna in 2008. There appears to be less consistency regarding participants than in the previous years, such as Aeneas, Serge Trifkovic, but also Elisabeth Sabaditsch-Wolff and Rolf Krake, along with several country representations in the summit. More specifically, Aeneas, a key blogger at Gates of Vienna and also Director of CVF (later known as ICLA), appears as an established and important figure of CJM-N in UK and Europe.

Table 5.3 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Aeneas Lavinium |

UK |

14 |

| 2 |

Jim Lake |

UK |

1.5 |

| 3 |

Steen |

Denmark |

1.5 |

| 4 |

Sparks |

Hungary |

1.5 |

| 5 |

Multikultur |

Germany |

1.5 |

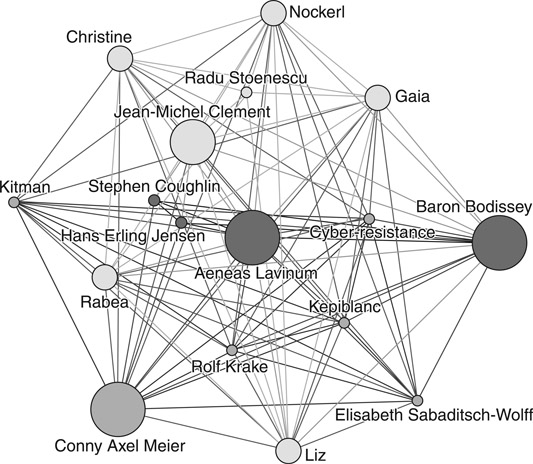

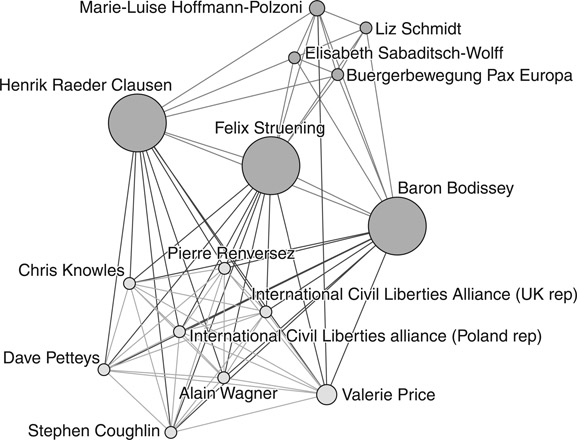

CJM-N Zurich 2010 (17 nodes, 101 edges)

Following the working meeting format, the CJM conference in Zurich in 2010 numbered several representatives across Europe. Elisabeth Sabaditsch-Wolff, a regular at the CJM conferences, along with Aeneas and Jean-Michel Clement were among the participants, as well as several activists and journalists attending the event. What appears to be rather interesting in the case of Zurich’s conference is the high level of pseudonyms used in the official participants list, rather than the real names of the attendees. The focus of the conference was a level of separation from the political regime and the continuing efforts to raise the awareness about the dangers and threat of Islamisation.

Table 5.4 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Conny Axel Meier |

Germany |

6.458 |

| 2 |

Aeneas Lavinium |

UK |

6.458 |

| 3 |

Baron Bodissey |

US |

6.458 |

| 4 |

Jean-Michel Clement |

France |

5 |

| 5 |

Gaia |

UK |

2.125 |

The modularity algorithm has disclosed a closed network – i.e. all nodes are connected, with three communities (Figure 5.4; modularity: 0.053) and a rather dispersed betweenness centrality, but there is certainly a top three of nodes/hubs. This closed network is informative regarding the relations between nodes. When looking into closeness centrality, we found that Baron Bodissey, Aeneas and also Conny Axel Meier share the same data and all have the same degree (fifteen edges each), closeness centrality (1.062) and betweenness centrality. This tells us that these are rather powerful nodes in the network, in the sense that they can influence and affect it with the information they share (as they are well-connected) – a rather interesting perspective while examining the CJM network.

CJM-N London 2011 (13 nodes, 36 edges)

The London conference of CJM in 2011 was rather different from those held so far. Among the participants were a number of people associated with ICLA – e.g. Paul Weston, Aeneas and Elisabeth Sabaditsch-Wolff, but also journalists from Europe News and numerous activists from several European countries. Among the participants were Tommy Robinson from EDL and George Whale, co-founder of Liberty UK, along with other politicians and bloggers, the majority of whom originated from the UK. The main focus of the discussion concentrated on the current (at the time) situation in the UK and, more specifically, the ‘unprecedented repression directed at the EDL and other dissidents demonstrates that the authorities are frightened by mass opposition to Islamisation and sharia, and are determined to use any means to suppress dissent’ (Bodissey 2011).

Baron Bodissey’s significance is minimal in this network. It is because the actors with higher betweenness centrality and degree are involved in roles that he is not. For example, this network is monopolised by politicians and activists. In this respect, his argument for a distributed network is somehow accurate – in the past, he was a more significant agent in a network, but in this case he is not. However, it should be noted that there is still centralised power in the network, which is mediated through the aforementioned agents.

This is another closed network with two communities (Figure 5.5; modularity: 0.387), with 2 major nodes (politicians and activists Paul Weston and Tommy Robinson). What appears to be the case in London’s conference is that the communities are tied down to location and it appears that most conference delegates were based in the UK, something that has affected the specific network.

Table 5.5 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Paul Weston |

UK |

17 |

| 2 |

Tommy Robinson |

UK |

17 |

| 3 |

Gaia |

UK |

14 |

| 4 |

Henrik Raeder Clausen |

Denmark |

14 |

| 5 |

Peter Mullins |

UK |

0 |

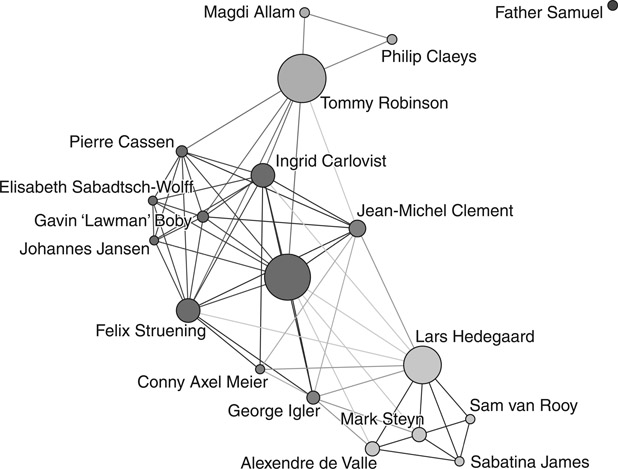

CJM-N Brussels 2012 (19 nodes, 63 edges)

Five years after the first Counter-Jihad conference in Brussels in 2007, members and leaders of the movement held a conference in the EU Parliament in 2012, sponsored by ICLA, launched as the International Conference for Free Speech and Human Rights. The focus of the conference was a so-called ‘re-branding’ of Brussels, a project launching a Brussels Declaration, ‘a resolution designed to stand in contrast to the 1990 Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam’ to present:

our politicians and their media cheerleaders with the stark facts – that Islamic law violates the central precepts of both individual liberty and human rights as the West understands them – we intend to shine a light on the betrayal of our nations by the elites who govern them.

(Bodissey 2012)

Additionally, the agenda of the conference included the expansion of repression in Western societies against critics of Sharia law and Islamisation, the launching of new initiatives, political and legislative, focusing on the issues of Sharia and Islamisation and the issue of coordinating the network of CJM-N. Among the participants were members of political parties – e.g. Philip Claeys of Vlaams Belang and Magdi Allam of UDC – activists and bloggers known to CJM-N – e.g. Jean-Michel Clément, Elisabeth Sabaditsch-Wolff and Felix Strüning – authors – e.g. Sabatina James, Sam van Rooy and also Tommy Robinson and Lars Hedeggard, key figures in CJM and regular participants of the conferences.

In total, there are five communities (Figure 5.6; modularity: 0.249). Basically, this figure shows that in 2012 the most influential actor was Tommy Robinson, which can be explained due to his extended and principal presence and activity in CJM-N. It is obvious that Father Samuel, a priest, will have the smallest community, because he had no connection to any other agent. What begins to become rather clear is the distinguishing level of polarisation of the network, pointing to the fact that there is very strong clustering among the agents.

CJM-N Warsaw 2013 (15 nodes, 74 edges)

Table 5.6 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Tommy Robinson |

UK |

30 |

| 2 |

Christian Jung |

Germany |

28.833 |

| 3 |

Lars Hedegaard |

Denmark |

21.6 |

| 4 |

Felix Struening |

Germany |

10.767 |

| 5 |

Ingrid Carlqvist |

Sweden |

10.767 |

The seventh and last Counter-Jihad conference was held in Warsaw and was convened with the OSCE Human Dimension Implementation Meeting that was taking place at the same time in Poland. The conference was attended by representatives from twelve countries, including Canada and the USA. The conference addressed the issue of the isolation of Counter-Jihad groups and anti-Sharia organisations and ways of developing the network and collaborations among these groups even further. Additionally, the agenda included the issues of the increase in violence from Muslim immigrants in Western Europe, the growing Islamisation of public institutions – e.g. schools and building of mosques – and the increasing number of immigrants and the need for further policies in order to address the issue (see Bodissey 2013). Participants included Baron Bodissey, Elisabeth Sabaditch-Wolff and Felix Struening from the blogging community, but also several representatives of ICLA – e.g. Alain Wagner and Pierre Renversez – and newer members in CJM – e.g. Valerie Price from ACT! for Canada and Dave Petteys from ACT! for America.

Table 5.7 Betweenness centrality ‘top five’

| Rank position |

Name |

Country |

Betweenness centrality |

|

| 1 |

Baron Bodissey |

US |

9.5 |

| 2 |

Felix Struening |

Germany |

9.5 |

| 3 |

Henrik Raeder Clausen |

Denmark |

9.5 |

| 4 |

Valerie Price |

Canada |

1.75 |

| 5 |

Marie-Luise Hoffmann-Polzoni |

Germany |

0.75 |

For this conference, there were two communities (Figure 5.7; modularity: 0.158) with Baron Bodissey and Felix Struening re-appearing among the stronger hubs. In this network, similar to the previous cases since 2011, a polarisation between the two different clusters is vibrant.

As Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun (2013) have highlighted, the indirect implication is that the CJM-N will exist without an apparent internal structure and/or a leader. However, when examining the CJM network at different times in its history, some distribution is observed (particularly in European countries), but in certain cases, there are some key social agents that emerge as nodes–hubs. First, these hubs suggest higher activity; and second, they act as facilitators connecting other nodes together.

The Internet works as enabling platform for CJM to share information, views and thoughts, but also promote their agenda and organise events. By choosing an electronic communication, according to Bodissey (2009a), the risk of legal actions by ‘repressive governments’ against people sharing the CJM’s opinions is minimised, along with the unofficial repression originating from left groups and parties and the danger of attacks by Muslims. As seen above, Bodissey additionally has pointed out that in a distributed network, regardless of the lack of a decentralised organisational structure, the decision-making process still lingers. Additionally, the structure of the movement offers flexibility when it comes to sharing information through the network, but nonetheless the possibility of losing interest among the users is high and redundancy is essential (see Bodissey 2013). Kundnani (2012) has underlined the key role of the Internet in the CJM and uses as an example the ‘2083 – A European Declaration of Independence’ of Breivik (2011), where numerous quotes from webpages and blogs of the CJM have been included – e.g. Political Correctness, Jihad Watch, Bat Ye’Or, Gates of Vienna, Fjordman and Robert Spencer, among others.

SNA of CJM has showed that for the first years of the conference the generated figures were rather closed networks with strong connections between the agents. However, since 2011 and onwards, a polarisation in the network is observed presenting a distinguished level of separation between the communities. This could be explained in terms of the level and variety of participation and the affiliation of the attendees – e.g. Baron Bodissey is a blogger, but he also represents an organisation and a sense of hierarchical order of the CJM. Throughout the years, several distinguished names appear, who are key figures and well-known active members of CJM – e.g. Baron Bodissey, Aeneas Lavinium, Lars Hedegaard and Elisabeth Sabaditch-Wolff – with high levels of contribution and presence online on individual/personal blogs, but also on major blogs of the CJM, such as the Gates of Vienna and Jihad Watch. Regarding the organisations, the networks that were mentioned above – including the International Free Press Society, Stop Islamisation and International Civil Liberties Alliance – have regular representatives from numerous countries at the conferences. The Defence League also has a strong presence, and political parties’ representatives from far right parties – e.g. Vlaams Belang and the Sweden Democrats – also have a solid role. Nevertheless, the structure of the network presented above failed to reach the expectations and goals of the CJM as proposed by Bodissey, since it has not managed to become either distributed or decentralised; something acknowledged by the CJM, since the subject of the network and ways and alternatives of achieving a certain level of development are placed at the top of the agenda in the majority of the conferences.

Since 2013, Counter-Jihad conferences have stopped being organised in Europe, something that points to a decline in European CJM-N, despite the fact that sporadic actions still take place – e.g. the Patriotic Europeans against Islamisation of the West (Pegida) protest in Dresden 2014. Nevertheless, the USA seems to be rather active online, especially on Twitter (see Twitter analysis below) and blogging communities, and through SIOA and ACT! for America several events have been organised in the USA – e.g. the National Conference and Legislative Briefing in Washington in September 2015 and the Defeat Jihad Summit, which was sponsored by the Center for Security Policy in Washington, again earlier in 2015. Nevertheless, despite all the efforts of the CJM-N, its network still appears to be vulnerable towards criticism, due to the high level of Islamophobia in its narrative. Within the CJM-N, it appears that a strong hierarchy has been formed, particularly around agents who are based in Europe. As Twitter analysis will show below, this is contrasted by the activity in the USA. However, it is still unclear whether the CJM-N is a stable network that can influence its peer sub-networks, which are formed by CJM-N agents who simply form other social networks in their lives.

Discernments of the West and Islam: the populist discourse of the CJM

As with any forming of political ideology or cultural phenomenon, the actors identified with counter-jihad are heterogeneous. There are differences and even conflicts between the many characters involved. Overall, however, they all agree that Islam as an ideology is a threat to non-Muslims and to Western culture.

(Archer 2008)

In order to have a clear perception of the CJM-N apart from the developed network, we will briefly examine its populist discourse. In order to do so, a critical frame analysis is adopted. Framing analysis is a process by which we may observe and analyse the way in which the sender of a message uses image framework, which is usually emotional, in order to lead the receiver to specific conclusions. The idea of framing analysis can be found in Entman’s (1993) work, where he argues that to

… frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation.

(Entman 1993: 52)

Discourse is essential in order to identify the language that members of the CJM choose to use. According to Foucault, who we are, what we think, what we know and what we talk about are all produced by the various discourses we encounter and use. They provide us with our thoughts and our knowledge and, therefore, can be said to be behind or to direct any actions we choose to take (Jones 2003: 145). By adopting frame analysis as a methodological approach, we aim ‘to identify, within a text, institutionally supported and culturally influenced interpretive and conceptual schemas that produce particular understandings/meanings of issues and events’ (Bacchi 2005: 199).

The CJM, as mentioned above, is based on a shared ideology that focuses on the presence of Muslim communities and groups in the West working on a plan of Islamisation of Western societies. Therefore, Muslims are portrayed as a major ongoing threat to the security and cultural identity of the West: ‘At the siege of Vienna in 1683 Islam seemed poised to overrun Christian Europe. We are in a new phase of a very old war’ (Bodissey 2004). In this narrative hosted on the Gates of Vienna, the mass – which in this specific case is the Christian population of Europe – is under threat from a hostile ‘other’: Islam. For Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun (2013: 54), a key question to be addressed is the essentialist interpretation of Islam – in other words, is the presence of non-extremist Muslims acknowledged and to what extent is this an effort to avoid public criticism? They similarly voice additional concerns over the extent to which these distinctions filter down to other members of the movement – in particular, those participating through street actions and online comment sections.

Nevertheless, the focus of the analysis in this part is the expression and context of populism, with a clear distinction between the mass, the other and the established elite that characterises this style of discourse. Identity, in the case of the CJM, adopts an extensive sense, in the name of which the CJM acts, in order to defend it – that is, not limited to a single country, but is constructed at a global level and not identified as a single ethnic group, but is rather widely conceptualised: ‘The West’. For example, Fjordman often refers to the West, which according to him ‘suffers from lack of cultural confidence’ and whose ‘creed of multiculturalism’ is taken as a sign of weakness by Muslim immigrants and suggests the creation of an environment where the practice of Islam would be limited and Muslims should be forced ‘to either accept our secular ways or leave if they desire sharia’ (Fjordman 2006). Putting emphasis on the threat of Islamisation of the Western world, Muslims are represented in violent acts and crime – e.g. rapes and imprisonment statistics. As Srdja Trifkovic (2006), the author of Defeating Jihad, underlines there is a demonstrable correlation between the percentage of Muslims in a country and the increase of terrorist violence in that country. The CJM in its narrative often accuses the press of being biased and favouring multiculturalism, by distorting the reality in which incidents of racism and xenophobia occur. For Gerald Batten (2007), in a speech he gave at the Brussels Counter-Jihad conference of 2007, ‘the prevailing and corrosive doctrines of political correctness and multiculturalism have infected every public body and institution. Anyone who dares to question or criticise Islam risks being labelled a racist or Islamophobic or an official sanction of some kind’. This issue has been addressed at the Counter-Jihad conferences mentioned above, with the CJM challenging the depth of freedom of speech in Western societies, as members of the CJM have been accused of Islamophobia, racism and hate speech on several occasions. In order to maintain a politically correct status, the political elite, along with the media, suppress the right of freedom of speech that safeguards democracy, according to the CJM narratives.

After Breivik’s violent acts in Oslo 2011, many assumed that Islam extremists were behind the attacks. As Pamela Geller indicated just after the attacks:

Jihad is not the problem. New York’s 9/11, London’s 7/7, Madrid’s 3/11, Bali, Mumbai, Beslan, Moscow […] is not the problem. ‘Islamophobia’ is the problem. Repeat after me as you bury the dead, ‘Islamophobia is the problem, Islamophobia is the problem’.

(Geller 2011)

Notoriously, the Gates of Vienna has published and hosts opinions calling for a Muslim Holocaust.

If violence does erupt in European countries between natives and Muslims, I consider it highly likely that people who had never done anything more violent than beat eggs will prove incapable of managing the psychological transition to controlled violence and start killing anything that looks remotely Muslim. Our unspoken conviction that we, in 21st-century Europe, have moved beyond such savagery will be shown to be an arrogance founded on a few decades of fragile peace and prosperity, taken for granted and allowed to slip through our fingers for no reason at all.

(El Inglés 2008)

Beyond Muslims and Islam, the CJM also has been critical towards the established political elites and accuses – in particular, the EU – of being biased in favour of Islam against Christianity:

To the EU elites, criticism of or negative statements about Islam is considered a form of ‘hatred’ that is unacceptable and should perhaps be legally prosecuted. Criticism of or even outright hatred directed against Christianity, Europe’s traditional majority religion, however, is considered acceptable. The EU thus awards Islam a special status, elevated above Christianity. This policy coincidentally overlaps with sharia, Islamic religious law.

(Fjordman 2015)

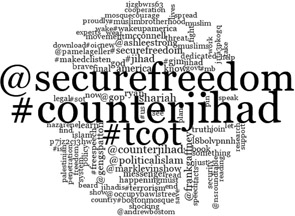

In order to examine the discourse of the CJM in a different aspect, we conducted discourse analysis by selecting Tweets that included the Counter-Jihad. Due to the limitations of Twitter, which means the user is only able to capture limited days of activity, the analysis focuses on activity from 14 to 21 December 2015. The analysis included 1,156 Tweets and the results were rather enlightening.

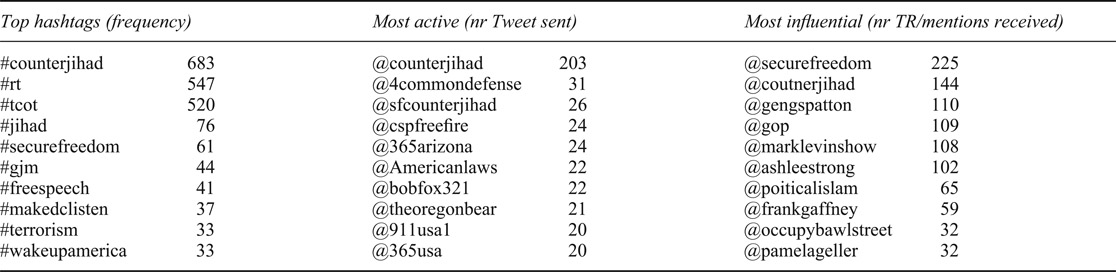

While running a word frequency test on NVivo, the output demonstrated a cluster including most frequently mentioned words in the Tweets. As seen in the tables, the more commonly used hashtags include references directly linked to the CJM’s narrative – e.g. #freespeech, #terrorism and #jihad – but also references to organisations linked to the CJM – e.g. #securefreedom or #tcot (top conservatives on Twitter, a term used as reference to a significant group of so-called top conservatives). Additionally, @counterjihad user is the basic hub in both most active users and in the most influential ones, followed by @securefreedom account of think tank The Center for Security Policy. Other influential users include Pamela Geller and the founder and president of the Center for Security Policy, Frank Gaffney. Finally, when examining the interaction between the users, there are distinguished clusters and regular users that re-Tweet repeatedly – e.g. @gengspatton and @marklevinshow.

Table 5.8 Word frequency ‘top ten’

| Rank position |

Word |

Count |

Weighted percentage (%) |

|

| 1 |

#counterjihad |

1,552 |

5.97 |

| 2 |

@securefreedom |

1,403 |

5.40 |

| 3 |

#tcot |

1,183 |

4.55 |

| 4 |

@counterjihad |

203 |

0.78 |

| 5 |

shariah |

191 |

0.73 |

| 6 |

@politicalislam |

168 |

0.65 |

| 7 |

@frankgaffney |

162 |

0.62 |

| 8 |

#jihad |

158 |

0.61 |

| 9 |

#securefreedom |

144 |

0.55 |

| 10 |

America |

136 |

0.52 |

The discursive patterns that emerge can be divided into three categories. First, in terms of sentiment, there is a clear negative narrative (including words on terrorism, help and penetration). Second, there is a sense of geographical belonging, with direct mentions to, for example, America and Palestine. Third, awareness appears to be a strong discourse in these Tweets – e.g. ‘wakeup-america’ and ‘makedclisten’. Looking at the content of the Twitter data, the narrative follows the general discourse that characterises the CJM, focusing on the threat of Islamisation of the Western world. The users often share videos and articles aiming to inform the public on the rising securitisation issue. What is interestingly recognisable is the fact that the location of the users are based mainly in the USA, with minor activity being noticed in Europe and the rest of the world.

This analysis on Twitter addresses, again, the issue of the distribution and decentralisation of the network that was examined thoroughly above. Despite the limited sample, the research shows that the CJM-N has not managed to develop and grow systematically in Western societies and, more significantly, in Europe, under a universal structure, hierarchy and organisation.

Conclusion

As mentioned above, Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun (2013), in their report by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, have argued that in the case of the CJM the purpose is to protect the shared culture and history of Western societies and that for this reason the CJM could be examined as a far right extremist movement which emerged to respond to the rising threat of Islam and Muslims in Western societies. Nevertheless, along

with Goodwin (2013), Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun (2013) distinguish the CJM from traditional anti-immigrant and ethnic nationalist groups on the grounds that they do not attempt to develop a wider ideological programme and instead focus only on their opposition to Islam and a hegemony of the West. Yet, scholars have argued that, first, the traditional far-right narratives were replaced by anti-Islamic issues (Zúquete 2008) and, second, as seen above, the ‘race war’ of the conventional neo-Nazism doctrine is replaced by a cultural one (Kundnani 2012: 5). However, as Goodwin highlights, the CJM is ‘embryonic’ (2013: 4) and the extent to which the movement either develops its own political parties or is able to influence others – in particular, those who currently occupy the far right spectrum – remains to be seen. In other words, despite the similarities with the far right rhetoric opposing multiculturalism and the links of the CJM with street movements such as the Defence Leagues, small political parties like Liberty GB or the personal links of CJM individuals with political parties in national scenes – e.g. Breivik and the Fremskrittspartiet – the CJM appears to remain in this ‘embryonic’ stage without achieving an influential status.

The CJM argues that the CJM-N is a well-connected and balanced network where all participants can be equally powerful. This rhetoric is rational, provided that there is no external source of power – for example, someone who manages the network. However, networks tend to develop a sense of internal order (Caldarelli and Catanzaro 2012), despite the lack of external power. As shown from the SNA, the CJM-N demonstrate clear hubs and clusters of power. In certain cases, these are formed by the same participants. This negates the rhetoric of equality presented by the CJM. Further research into the CJM-N would be particularly insightful in observing the phenomenon, aiming to identify certain ‘power nodes’ across various temporal and, perhaps, spatial dimensions.

As Meleagrou-Hitchens and Brun (2013) conclude, the CJM has managed to attract the attention of people from the far right scene, but the movement’s variety has also contributed to a richer understanding of groups, organisations and general participants that construct its network. Despite the CJM’s increasing organisational capacity, and the alliances that have been shaped and strengthened (e.g. from American representatives like Robert Spencer, especially after 2007), the movement with its hegemonic discourse has yet to prove and establish itself, especially in an environment where the narrative regarding the threat of Islamisation is adopted by mainstream political parties in an ongoing migration crisis.

Notes

References

Aradau, C. and Van Munster, R. (2009) ‘Poststructuralism, Continental Philosophy, and the Remaking of Security Studies’, in V. Mauer and M. Dunn Cavelty (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Security Studies, 73–83. London: Routledge.

Archer, T. (2008) ‘Countering the “Counter-jihad”’, RUSI Monitor. www.rusi.org/publications/monitor/articles/keywords:counter-jihad/ref:A48A5851376CB9/.

Bacchi, L. C. (2005) ‘Discourse, Discourse Everywhere: Subject “Agency” in Feminist Discourse Methodology’, Nordic Journal of Women Studies 13(3): 198–209.

Bangstad, S. (2014) Anders Breivik and the Rise of Islamophobia. London: Zed Books.

Baron Bodissey (2004) ‘The Newest Phase of a Very Old War’, Gates of Vienna, 9 October 2004. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.gr/2004/10/newest-phase-of-very-old-war.html.

Baron Bodissey (2006a) ‘Synergy and Synchronicity’, Gates of Vienna, 8 October 2006. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.co.uk/2006/10/synergy-and-synchronicity.html.

Baron Bodissey (2006b) ‘The Emperor is Naked’, Gates of Vienna, 26 September 2006. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.se/2006_09_01_archive.htm.

Baron Bodissey (2008) ‘Slouching Towards Vienna’, Gates of Vienna, 16 May 2008. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.gr/2008/05/slouching-towards-vienna.html.

Baron Bodissey (2009a) ‘Building a Distributed Counterjihad Network’, Gates of Vienna, 1 June 2009. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.co.uk/2009/06/building-distributed-counterjihad.html.

Baron Bodissey (2009b) ‘Slouching Towards Copenhagen’, Gates of Vienna, 23 May 2009. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.gr/2009/05/slouching-towards-copenhagen.html.

Baron Bodissey (2009c) ‘The Counterjihad Manifesto’, Gates of Vienna, 30 November 2009. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/counterjihad-manifesto.html.

Baron Bodissey (2011) ‘Slouching Towards London’, Gates of Vienna, 2 October 2011. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.gr/2011/10/slouching-towards-london.html.

Baron Bodissey (2012) ‘Slouching Towards Brussels’, Gates of Vienna, 15 July 2012. http://gatesofvienna.net/2012/07/slouching-towards-brussels-redux/.

Baron Bodissey (2013) ‘Slouching Towards Warsaw’, Gates of Vienna, 6 October 2013. http://gatesofvienna.net/2013/10/slouching-towards-warsaw/.

Batten, G. (2007) ‘Speech to CounterJihad Conference Brussels’, Countering the Counter-Jihad, 17 October. http://countering-the-counter-jihad.blogspot.co.uk/2007/10/gerard-batten-speech-given-to.html.

Betz, H. G. (1998) ‘Introduction’, in H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds), The Politics of the Right. Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies, 1–10. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Betz, H. (2013) ‘Mosques, Minarets, Burqas and Other Essential Threats: The Populist Right’s Campaign against Islam in Western Europe’, in R. Wodak, M. KhosraviNik and B. Mral (eds), Right Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse, 71–88. London: Bloomsbury.

Bishop, J. (2012) ‘The Psychology of Trolling and Lurking: The Role of Defriending and Gamification for Increasing Participation in Online Communities using Seductive Narratives’, in H. Li (ed.), Virtual Community Participation and Motivation: Cross-disciplinary Theories, 160–176. Herschey: IGI Global.

Breivik, A. B. (2011) ‘2083 – A European Declaration of Independence’. https://fas.org/programs/tap/_docs/2083_-_A_European_Declaration_of_Independence.pdf.

Caldarelli, G. and Catanzaro, M. (2012) Networks: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Carr, M. (2006) ‘You Are Now Entering Eurabia’, Race & Class 48(1): 1–22.

El Inglés (2008) ‘Surrender, Genocide… or What?’, Gates of Vienna, 24 April 2008. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.gr/2008/04/surrender-genocide-or-what.html#readfurther.

Entman, R. M. (1993) ‘Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm’, Journal of Communication 43: 51–58.

Fekete, L. (2001) ‘Race and Class’, Institute of Race Relations 43(2): 23–40.

Fekete, L. (2012) ‘The Muslim Conspiracy Theory and the Oslo Massacre’, Race & Class 53(3): 30–47.

Feldman, M. (2013) ‘Comparative Lone Wolf Terrorism: Toward a Heuristic Definition’, Democracy and Security 9(3): 270–286.

Fjordman (2006) ‘Recommendations for the West’, Gates of Vienna, 10 October 2006. http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.gr/2006/10/recommendations-for-west.html.

Fjordman (2007) ‘Native Revolt: A European Declaration of Independence’, The Brussels Journal, 16 March 2007. www.brusselsjournal.com/node/1980.

Fjordman (2015) ‘The EU Elites’ Positive View of Islam’, Gates of Vienna, 14 October 2015. http://gatesofvienna.net/2015/10/the-eu-elites-positive-view-of-islam/.

Garland, J. and Treadwell, J. (2010) ‘No Surrender to the Taliban: Football Hooliganism, Islamophobia and the Rise of the English Defence League’, Papers from the British Criminology Conference 10: 19–35.

Geller, P. (2011) ‘Oslo Bombed, Dead, Injured at Government HQ UPDATE: Multiple Attacks, Blasts and Gun Attacks, 16 Dead, Hundreds Hurt’, 22 July 2011. http://pamelageller.com/2011/07/jihad-in-norway-oslo-bombed.html/#sthash.793c9zrq.dpuf.

Geller, P. (2012) ‘Counter Jihad Front SION: September 11, 2012 Freedom Congress, UN Plaza’. http://pamelageller.com/2012/09/video-tommy-robinson-edl-leader-at-sion-911-international-freedom-of-speech-congress.html/#sthash.JAPGDTnT.dpuf.

Goodwin, M. (2013) ‘The Roots of Extremism: The English Defence League and the Counter-Jihad Challenge’, Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/public/Research/Europe/0313bp_goodwin.pdf.

Huntington, S. P. (1993) ‘The Clash of Civilizations?’, Foreign Affairs 72(3): 22–49.

Huntington, S. P. (1996) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Jacomy, M., Heymann, S., Venturini, T. and Bastian, M. (2012) ‘ForceAtlas2, a Figure Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization’, Sciences Po. 44. www.medialab.sciences-po.fr/publications/Jacomy_Heymann_Venturini-Force_Atlas2.pdf.