THIRTEEN

Getting Along

MUTUALISM, FACILITATION, AND COEVOLUTION

CONTENTS

Species Associations and the Potential for Other Forms of Facilitation

Coevolution: Diffuse and Direct

Forms of Coevolution and Eco-Evolution

Longevity of Species Associations

THE PREVIOUS CHAPTERS in Part 4 mainly focused on symmetrical negative interactions like competition or asymmetrical positive/negative interactions such as predation. Indeed, such fully or partially negative interactions have dominated ecological research since Darwin. Much of the earlier literature on competitive interactions, in fact, focused on how different species avoided or reduced spatiotemporal overlap (for instance the concept of resource partitioning). However, interactions that are symmetrically positive or asymmetrically positive and neutral are being increasingly recognized as important in the formation and maintenance of communities (Bruno et al. 2003). This leads to a potential cost-benefit situation of avoiding other species to reduce competition or joining them to reap benefits of group foraging or predator avoidance, and perhaps also to benefit from reduced intraspecific competition (Freeman and Grossman 1992). The occurrence of facilitative interactions among species requires close contact for the various direct interactions treated in the following sections, but less so for indirect interactions.

That different species of North American freshwater fishes frequently occur close together is not at issue. In virtually all aquatic habitats, capturing two or more fish species in a short section of stream or lake shoreline is more common than not. Based on museum records of 291 collections from a variety of aquatic habitats in Minnesota, over 60% of the collections included two or more species, almost a third included three or more, and 9% included five or more species (Mendelson 1975). Similarly, based on 300 museum collections taken over 13 years from a variety of stream and pond habitats in Mississippi, 79% of the collections included two or more species, 66% included three or more, and 54% included five or more (University of Southern Mississippi, Museum of Ichthyology). At the finer scale of individual small seine hauls (ca. 10-m2) in the Canadian River, Oklahoma, 71% included at least two species and 46% included three or more species (Matthews 1977). In a wave-exposed littoral zone of Lake Texoma, a large impoundment on the Texas-Oklahoma border, 86% of seine hauls had at least two minnow species and 60% included three or more minnow species (Matthews 1998). The number of different species likely to be taken in a small area is obviously positively related to regional diversity (see Chapter 4), but these comparisons show that fish species in North American freshwater habitats are commonly in relatively close association with each other.

Statistical tests of fish species’ associations also show the potential for interactions if associations are positive or the lack thereof if associations are negative. Based on fishes captured in individual seine hauls, eight minnow species in a Mississippi blackwater stream showed nine significant associations, of which four were positive—Blacktail Shiner (C. venusta) and Longnose Shiner (N. longirostris), Blacktail Shiner and Longjaw Minnow (Notropis amplamala), Longnose Shiner and Striped Shiner (Luxilus chrysocephalus), and Longnose Shiner and Longjaw Minnow (Baker and Ross 1981). In a study of habitat associations of nine fish taxa in a small Minnesota Lake, there were three positive associations out of a total of 15 significant species associations—Mimic Shiner (Notropis volucellus) and Bluntnose Minnow (Pimephales notatus), Bluntnose Minnow and White Sucker (Catostomus commersonii), and Common Shiner (Luxilus cornutus) and White Sucker (Moyle 1973). Habitat associations were determined by scuba observations of fishes occurring in 1-m2 plots in the littoral zone. Although such examples of mixed species occurrences in localized field samples generally do not yield information on actual interactions among species, they do suggest the potential for interactions among different species of fishes.

The presence of actual mixed species groups provides even stronger support for potential interactions among species. Rosyside Dace (Clinostomus funduloides), other cyprinids, and Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) commonly formed mixed-species groups in two small North Carolina streams (Freeman and Grossman 1992), and minnows in a small Ozark stream often formed mixed shoals that were vertically and horizontally intermixed (McNeely 1987). Such interactions among species could include facilitation of feeding, enhanced awareness of potential predators, or compression of species into habitats offering low predation risk (Gorman 1988a, b; Freeman and Grossman 1992). The nature of these interactions and how tightly species are linked in associations is the topic of the rest of this chapter.

FACILITATION

Facilitation, the situation where one organism makes the local environment more favorable for another, is extremely widespread in nature and can occur at numerous points in an ecosystem with widely varying strengths (Bruno et al. 2003; Nummi and Hahtola 2008). Facilitative relationships can be loose associations as well as tightly coevolved and mutually obligate (Box 13.1) (Bruno et al. 2003), and facilitation in fish assemblages can occur between fishes and other taxa, such as riparian vegetation, wading birds, or with other fish species. For example, evidence supporting the model of predation risk of prey fishes in response to terrestrial and aquatic predators (Chapter 12) involves a facilitative interaction between a wading bird and a piscivore. In a study of a wading bird (Heron, Ardea alba) and Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu) predation on Striped Shiner and Central Stoneroller (Campostoma anomalum), Heron predation forced the smaller size class of the prey fishes into deeper water where they were more vulnerable to the Smallmouth Bass (Steinmetz et al. 2008). The interaction, which was significant for the number of prey consumed, was largely asymmetrical, with Smallmouth Bass being positively affected by the Heron, whereas predation success of Heron remained essentially unchanged in tests with and without the piscivore present.

BOX 13.1 • A Hierarchy of Terms for Positive Ecological Interactions

With few exceptions, ecologists have focused on asymmetrical positive/negative interactions such as predation and competition—the “tooth and claw” sort of interactions where one organism is killing or hurting another. At the same time, interactions where organisms directly or indirectly help each other have been largely ignored until fairly recently, yet life on Earth as we know it is highly dependent upon such interactions (Roughgarden 1998; Stachowicz 2001; Bruno et al. 2003; Molles 2010). Facilitative behaviors among animals, including mutualisms, have been described since the nineteenth century, so it is no surprise that the terminology of interspecific interactions is complex. The following terminology is largely based on Boucher et al. (1982) and Bruno et al. (2003).

FACILITATION Encounters between organisms that benefit at least one of the participants and cause harm to neither (+/0; +/+).

COMMENSALISM Asymmetrical facilitation where one party benefits and the other is not affected (+/0).

MUTUALISM Symmetrical facilitation in which both parties benefit from the interaction (+/+).

DIRECT MUTUALISMS Physical contact between the species.

SYMBIOTIC MUTUALISMS Usually occur between different kingdoms of organisms, such as gut microbes or luminescent bacteria in the skin of some deep-sea fishes.

NONSYMBIOTIC MUTUALISMS There can be direct physical contact, but there are no direct physiological links between partners.

INDIRECT MUTUALISMS Positive effects occur in the absence of direct physical contact.

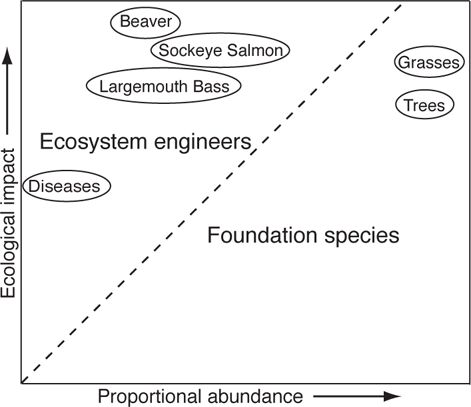

Facilitative interactions among widely different taxa are prevalent with foundation species and ecosystem engineers—species such as trees, grasses, and emergent and submerged aquatic vegetation, or animals such as Beavers (Castor canadensis) that in some way contribute a framework for the entire community by forming and modifying habitats (Jones et al. 1997a; Bruno et al. 2003; Nummi and Hahtola 2008). Although the two terms are sometimes used as synonyms, foundation species (or dominant species) alter the local environment simply by growing, and their effects are roughly in proportion to their abundance (usually expressed as biomass; Figure 13.1) (Power et al. 1996). An example would be the shading of pools in streams by riparian vegetation, resulting in cooler water and a more favorable environment for fishes. Ecosystem engineers (also called keystone modifiers) have impacts on their environment that are much greater than would be predicted by biomass alone (Power et al. 1996). Physical ecosystem engineering involves a process, such as dam building by Beavers, that results in some structural change (an impoundment), which in turn changes the physical environment (impounded versus flowing water), which can result in biotic changes to other species (alteration of invertebrate and fish assemblages) as well as provide feedback to the engineer (reduced risk of predation, etc.) (Jones et al. 1994, 1997a, 1997b, 2010). Although there are concerns about the use of “ecosystem engineer,” because of its being burdened by anthropomorphic overtones and implying purpose, over some more neutral term such as “keystone modifier” (Power 1997; Stachowicz 2001), the term continues to be widely used in ecology (Wright and Jones 2006; Jones et al. 2010).

In a situation closely analogous to trophic cascades, foundation species and ecosystem engineers can generate facilitation cascades. The primary difference from a trophic cascade is that the effect is not initiated by a top carnivore, although herbivores are often involved, especially in marine, rocky intertidal systems (Thomsen et al. 2010).

FIGURE 13.1. Foundation species versus ecosystem engineers. Foundation species have ecological impacts roughly proportional to their abundance and occur to the right of the dashed line of 1:1 equivalence. Ecosystem engineers have impacts that are out of proportion to their abundance and occur to the left of the dashed line. Based on data from Power et al. (1996).

Ecosystem Engineers

Species considered to be ecosystem engineers directly or indirectly control the availability of resources to other organisms by their physical modification, maintenance, or creation of habitats; however, the direct provision of resources by living or dead tissue does not constitute engineering (Jones et al. 1994, 1997a). Autogenic engineers function by transforming the environment through endogenous processes, such as tree growth, and remain part of the altered environment. For instance, caddisfly larvae construct armored cases out of gravel or other materials and also build silk nets to trap suspended particulate materials in streams. These biogenic materials can modify water flow in the boundary layer (see Chapter 7) by increasing stream bottom roughness, which translates into enhanced feeding success of the larvae (Nowell and Jumars 1984; Cardinale et al. 2002; Moore 2006).

Allogenic engineers, in contrast, alter the environment by transforming living or nonliving materials from one physical state to another and are not necessarily part of the modified physical structure. The classic example of an allogenic engineer is the Beaver, which harvests live trees (physical state 1) and converts them into dead trees (physical state 2), which are placed in a dam that creates a pond (Jones et al. 1994). Impacts of allogenic ecosystem engineers are generally of greater importance in streams of low to intermediate energy. In streams with high hydrologic energy, any impacts from ecosystem engineers would likely be overpowered by water energy. Impacts of ecosystem engineers on aquatic habitats are also greater when food webs are heavily subsidized so that the biomass of the engineering species is greater than could be sustained by local productivity, such as occurs with anadromous fishes in streams when their biomass is subsidized by oceanic productivity and, of course, with humans who are highly subsidized energetically and are the only animal to use powerful tools to enhance their impacts on ecosystems (Moore 2006).

Beaver engineering projects act initially by altering stream morphology and hydrology through wood harvesting and dam construction, creating habitat heterogeneity on a large scale by forming patches of lentic habitat in what is otherwise a corridor of lotic habitat. In general, Beaver impoundments are most likely in moderate-sized streams with relatively low gradients (Pollock et al. 2003; Jakes et al. 2007). Their impoundments increase Beaver habitats, expand their food supply, and provide protection from predators. Impoundments also increase retention of inorganic and organic sediments, facilitate groundwater recharge, create and maintain wetlands, alter nutrient cycling, change decomposition dynamics, influence water quality, transform riparian structure and diversity, and affect local plant and animal assemblages. Beaver impoundments flood and kill riparian trees, but following pond abandonment they result in the growth of meadow grasses that are ultimately replaced by shrubs and trees, not necessarily the same trees present before dam construction. A faunal consequence of Beaver engineering is the replacement of running-water invertebrate taxa such as blackflies, Tanytarsini midges, scraping mayflies, and net-spinning caddisflies by pond taxa such as Tanypodinae and Chironomini midges, predaceous dragonflies, tubificid worms, and filtering clams (McDowell and Naiman 1986; Naiman et al. 1988; Snodgrass 1997; Snodgrass and Meffe 1999; Wright 2009).

The sheer magnitude of the historic impact of Beaver on aquatic and riparian ecosystems is difficult to grasp. The North American landscape prior to European contact and colonization was covered by an estimated 25 million Beaver ponds that contained tens to hundreds of billions of cubic meters of sediment. Beaver occurred coast to coast and from the Arctic tundra to deserts of northern Mexico, so that their impacts on stream morphology and hydrology and the aquatic and riparian biota were a common and enduring feature of most North American landscapes (Naiman et al. 1988; Pollock et al. 2003). One consequence of overtrapping from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries was increased sediment evacuation from abandoned ponds, stream entrenchment, and wetland reduction (Butler and Malanson 2005). In addition, fish habitat availability was markedly reduced in low-order streams and many perennial streams likely became intermittent (Pollock et al. 2003).

Not surprisingly, Beaver impoundments have had substantial impacts on the numbers and kinds of fishes, especially in low-order streams; however, the impacts can change as a function of pond age, location within a drainage, and whether ponds are abandoned or maintained. Forty-eight species of North American freshwater fishes are commonly found in Beaver ponds, and at least 80 species have been documented using Beaver ponds (Pollock et al. 2003).

In a study of low-gradient streams (< 2m/km) on the Savannah River Site on the Upper Coastal Plain of South Carolina, Beaver ponds were initially colonized by small-bodied, insectivorous species such as Eastern Mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki), Lined Topminnow (Fundulus lineolatus), Lake Chubsucker (Erimyzon sucetta), Creek Chubsucker (Erimyzon oblongus), Sawcheek Darter (Etheostoma serrifer), Savannah Darter (Etheostoma fricksium), Ironcolor Shiner (Notropis chalybaeus), and Golden Shiner (Notemigonus crysoleucas) (Snodgrass and Meffe 1998). Over time, however, these species declined, primarily in response to colonization of the ponds by larger predators such as Redfin Pickerel (Esox americanus), Chain Pickerel (E. niger), Mud Sunfish (Acantharchus pomotis), Dollar Sunfish (Lepomis marginatus), Redbreast Sunfish (L. auritus), Warmouth (L. gulosus), and Flier (Centrarchus macropterus). Forty species were collected in the study and 17 species comprised ≥ 2% of the fishes collected. Overall, pond-associated fish species were minor elements of the stream fish assemblage. Of the 17 more common species in the study area, 14 had their greatest abundance in active or abandoned ponds and three had their greatest abundance in streams or recovering streams. Actual patterns of abundance among the four general habitat categories varied, with some species such as Yellowfin Shiner (Notropis lutipinnis) and Bluehead Chub (Nocomis leptocephalus) found primarily in streams and others such as Eastern Mosquitofish and Lake Chubsucker primarily, or only, in Beaver Ponds (Figure 13.2). In these low-order, blackwater streams, the effect of Beaver impoundments was to increase species richness in headwater streams. The elimination of Beavers from headwater streams would result in reducing species richness by over half. In fact, the presence of Beaver impoundments increased upstream species richness to the point that the positive relationship between fish species richness and stream order was eliminated (Snodgrass and Meffe 1998, 1999). Indeed, Snodgrass and Meffe (1998) suggested that the normally positive and widespread relationship between stream fish species richness and drainage area may be a recent phenomenon resulting from the extirpation of Beavers from much of their historical range.

Beaver dams, especially in later stages when they are larger, can impede the upstream and downstream movement of fishes. In the low-gradient South Carolina streams, passive downstream movement of age-0 fishes was interrupted by Beaver impoundments, with the fish being retained in the slower current just above the ponds. Further downstream movement was perhaps reduced because of predation risk incurred by traversing the open expanse of water from stream inflow to outflow over the dam (Snodgrass and Meffe 1999). In a small, relatively high gradient (10 m/km) stream in Minnesota, Beaver dams also acted as semi-permeable boundaries to fish movement and the degree of permeability likewise varied with direction (upstream versus downstream) and with factors such as pond age and morphology, and stream discharge (Schlosser 1995b). Permeability of the barrier for downstream movement from the pond to the stream increased as a function of increasing discharge, and declined greatly during low-discharge periods when Beaver seal the dam with mud and vegetation to improve water retention. Upstream boundaries between ponds and streams are more permeable to fish movement but can also decline during times of low discharge, whereas upstream movement from the stream into a pond, although it occurs, is perhaps less likely, especially during low-flow periods (Pollock et al. 2003).

FIGURE 13.2. Examples of frequency distributions of four southeastern fish species in streams and in Beaver impoundments. Overall, more species were most common in impoundments versus streams. Based on data from Snodgrass and Meffe (1998).

In contrast to the low-gradient South Carolina streams studied by Snodgrass and Meffe, Beaver ponds in Minnesota acted as reproductive source areas for fishes (see also Chapter 4 for source/sink terminology) and the adjacent streams appeared to be reproductive sinks, so that there was high overlap of species between the two major habitats (Schlosser 1995a, b). In fact, only one out of 12 commonly occurring species, Creek Chub (Semotilus atromaculatus), actually spawned in the stream. As shown in both the Minnesota and South Carolina studies, newly formed Beaver ponds are organically rich resource patches that are rapidly colonized and exploited by fishes and other organisms, followed by fairly rapid dispersal from the ponds.

Piscine Engineers

Various species of freshwater fishes channel some of their reproductive energy into the building of nest mounds or pits, as shown by various minnows, or circular depressions, as shown by various centrarchids. In addition, species of Pacific salmon (genus Oncorhynchus) excavate large nests in the streambed. In the latter case, the principal engineering effect is the alteration of large areas of the streambed. In the case of nests constructed by minnows and sunfishes, the nests are often used as spawning sites by other species—the nest associates.

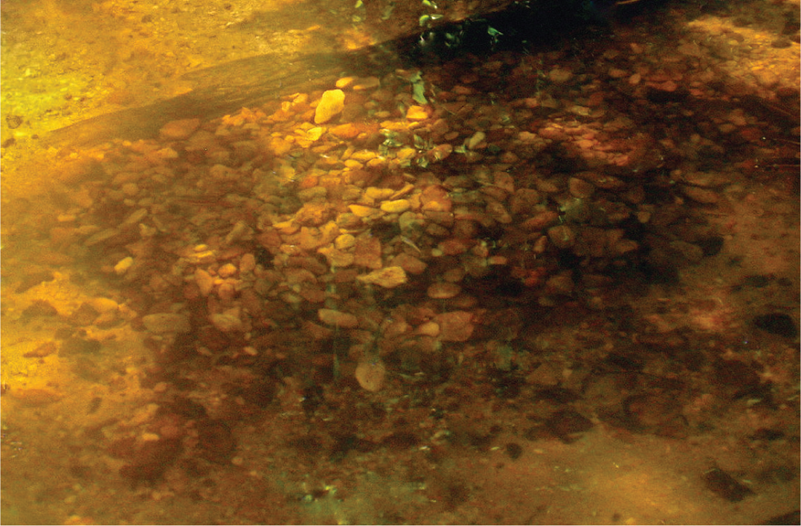

PACIFIC SALMON EXCAVATIONS The creation of large pebble nesting mounds and bioturbation by nest digging, foraging, and movement constitutes another type of allogenic habitat creation. For example, excavation of the large nests by various species of anadromous Pacific salmon can have a major impact in streams, especially given that the biomass of salmon is highly subsidized by marine productivity. Anadromous salmon accumulate > 99% of their lifetime growth in marine ecosystems (Moore and Schindler 2008). A female salmon excavates egg pockets in the streambed by turning on her side and rapidly undulating her large caudal fin (see also Chapter 9). After the eggs are laid and fertilized, the process is repeated, with the female digging additional egg pockets upstream, which also results in protecting the earlier nest site by covering it with additional gravel (Montgomery et al. 1996). In two streams in southwestern Alaska, such spawning behavior by Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) has consistently disturbed more than 5000 m2 of streambed (constituting about 30% of the available streambed) every summer over the last 50 years, and the effect would almost double in the absence of commercial harvesting. Nest digging displaces fine sediments, resulting in a coarser stream bottom in the spawning area, the deposition of fine materials downstream in pools and sandbars, and an increase in the concentration of suspended particulate materials in the water column. The impact of Sockeye Salmon excavations is detrimental to algal and invertebrate biomass. Above a density of 0.1 salmon m−2, algal and benthic invertebrate biomass decreased by an average of 75–85% during the approximately month-long spawning season (Moore and Schindler 2008). Recovery of algal biomass to presalmon levels only occurred in streams with low salmon densities (< 0.1 salmon m−2), and within the same season benthic invertebrate biomass did not recover. Although salmon spawning also increased the availability of nutrients in streams, there was no evidence that salmon positively impacted algal biomass on short-term (same year) or long-term (subsequent year) time frames. Overall, anadromous Pacific Salmon are an important component of stream disturbance regimes, with their impacts roughly similar to erosive flood events (Moore 2006).

The activities associated with nest construction by salmon also have a positive role in the formation and maintenance of salmon spawning habitats and on embryo survival. Survival of the developing embryos is dependent on the eggs being buried below the level of bedscour during the period of incubation. In a small stream entering Puget Sound, Washington, and in a stream near Juneau, Alaska, mass spawning activity by Chum Salmon (O. keta) reduced the vulnerability of eggs to bed-scour by removing fine sediments from the spawning area, although the effect of increased coarseness on reducing bed-scour was somewhat lessened by the more loosely packed bed materials. Overall, spawning activity decreases streambed mobility at a time when the developing embryos are most susceptible to displacement by high stream flow and thus may enhance the likelihood of offspring survival (Montgomery et al. 1996).

CYPRINID PITS AND MOUNDS Males of several genera of minnows excavate nest pits surrounded by pebbles and then attract females to spawn. For instance, Bluehead Chub, as well as other Nocomis species, build pebble mounds by excavating a pit in a shallow, gravel-bottomed section of a stream, then creating a mound by picking up stones with their mouths and filling the pit with gravel (Figure 13.3). Mounds can be group projects with 1–5 males involved, and the stones may be transported to the nest from as much as four meters away. When the mound is complete, smaller depressions are dug into the top or upstream edge, which serve as the spawning sites. The mounds are located in flowing water (ca. 11–25 cm s−1) and can be of substantial size, averaging 14,500 stones, 50–69 cm in diameter, and 14–24 cm in height (Wallin 1989; Johnston and Page 1992; Maurakis et al. 1992; Johnston and Kleiner 1994). Nests of the closely related Hornyhead Chub (N. biguttatus) can be up to 90 cm across and 30 cm tall and, in Wisconsin streams, averaged 40 × 50 cm and 6.4 cm above the substratum (Hankinson 1932; Robison and Buchanan 1988; Vives 1990).

FIGURE 13.3. Pebble nest of a Bluehead Chub (Nocomis leptocephalus) from a small stream in Mississippi. The nest is 66 cm × 40 cm. Photo courtesy of Mollie Cashner.

Male Creek Chubs construct a “pit-ridge” nest by initially removing stones with their mouths, or by shoving larger stones with their snouts, to dig a pit in the stream bottom. The stones from the pit are piled immediately upstream and nests are usually located in shallow channels. Males spawn multiple times, both with the same and with different females, and after each spawning event the male extends the pit farther downstream and covers the newly laid eggs with pebbles from the extended pit. Ultimately, the pit is preceded upstream by a longitudinal ridge (which fills in the trench) that may reach lengths of 5.5 m, and averages 69 cm long, 22 cm wide, and 4 cm high (Reighard 1910; M. R. Ross 1977; Maurakis et al. 1990; Johnston and Page 1992).

Male stonerollers (Campostoma spp.) also construct pebble nests by picking up pebbles in their mouths and moving them from the center to the edge of the nest pit. Pebble size is determined primarily by mouth size, although the male may remove larger stones from the nest area by pushing them with his head. This behavior also loosens sand and gravel, which is then carried away by the current. The nests vary in size, but most nest activity is focused in an area 15–30 cm in diameter and nests are generally 7.6 cm or less in depth (R. J. Miller 1962).

SUNFISH AND BASS NESTS Male centrarchids build and defend oval to circular-shaped nests. Most of the nest-building work is done by downward thrusts of the large caudal fin, although sometimes the nest area is cleared by sweeps of the pectoral fin, by carrying stones in the mouth or by pushing stones with the head (Warren 2009). For example, male White Crappie (Pomoxis annularis), occasionally with help from the female, build nests in the shallow water of streams or ponds. The nests average 30 cm in diameter and are somewhat irregular in shape (Hansen 1965; Siefert 1968). Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) males also build their nests in shallow water, usually around a meter deep or less. Nests are generally at least 2 m apart, but sometimes closer if underwater objects shield nests from view by other males (Clugston 1966; Heidinger 1976). During nest construction, the male places his head at the center of the nest and, by undulating the body and sweeping the caudal fin, clears out the area. Because of this activity, the nest diameter is usually equal to twice the body length of the male (M. H. Carr 1942). After spawning, the male bass (and rarely the female as well) cares for the eggs by fanning them day and night and by chasing away potential predators (Kramer and Smith 1960a). Nest guarding continues for several weeks after hatching (M. H. Carr 1942; Heidinger 1976).

Like other sunfish species, Longear Sunfish males fan out a depression in shallow water over areas with a gravel bottom and slow current flow using vigorous motion of the caudal fin. As with Largemouth Bass, the nest diameter is about twice the length of the fish, and nests are often constructed close together so that there are large aggregations of territorial, nesting males (Huck and Gunning 1967; Bietz 1981).

Mutualisms

In addition to asymmetrical (+/0) relationships, facilitative interactions may be symmetrical (mutualistic) when both species benefit from the association (Box 13.1) (Boucher et al. 1982). Mutualisms can be direct or indirect, the latter being the case of no direct contact but both parties benefit from the other’s presence. Direct mutualisms can be further subdivided into symbiotic and nonsymbiotic mutualisms with the distinction between them based on the level of physiological integration. Although exceptions are frequent, symbiotic mutualisms are usually coevolved and obligate with a strong physiological connection. In contrast, nonsymbiotic mutualisms tend to be facultative and not coevolved (Boucher et al. 1982). Much of the earlier literature on species associations treated mutualism as an obligatory response. However, numerous studies indicate that mutualisms are often context dependent and may be obligatory in one area but not another and may even change to antagonistic interactions (Gomulkiewicz et al. 2003; Hay et al. 2004).

Direct Mutualisms

Cleaning behavior is an example of a direct, nonsymbiotic mutualism. Although much more common in tropical fish assemblages, such behavior has been documented in Atlantic drainages of North America for coastal marsh or estuarine species, including the Rainwater Killifish (Lucania parva), Sheepshead Minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus), and Striped Killifish (Fundulus majalis) (Tyler 1963; Able 1976). Along the British Columbia coast, Threespine Stickleback are opportunistic cleaners, removing ectoparasitic copepods from juvenile Pink Salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) (Losos et al. 2010).

Indirect Mutualisms

In addition to direct physical contact, species can benefit each other in a variety of ways even though physical contact does not occur (Boucher et al. 1982). Benefits could occur through structures and other alterations of the physical habitat (ecosystem engineering) or by the importation of nutrients.

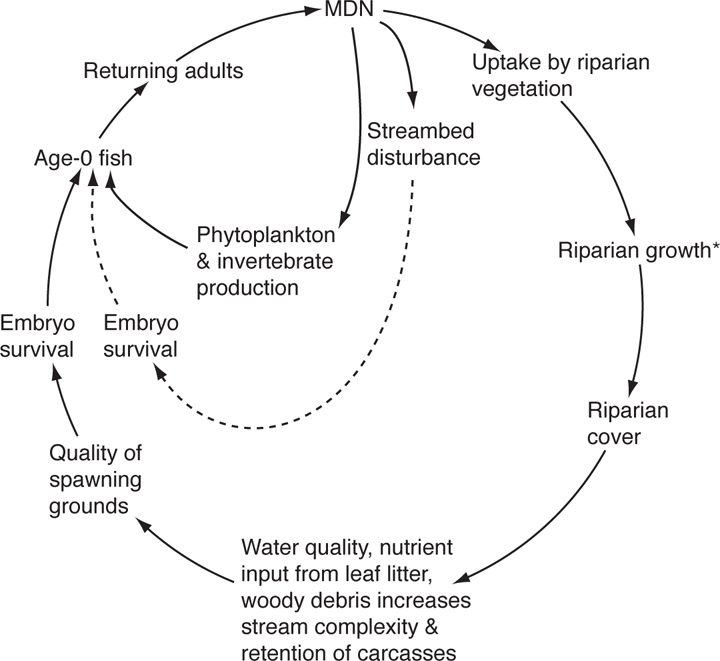

PACIFIC SALMON MIGRATIONS AND MARINEDERIVED NUTRIENTS Historically, the annual migrations of Pacific salmon from the ocean into freshwater streams and lakes, where they spawn and die, constituted the largest crossecosystem movement of biomass in the North Pacific region (Hocking and Reynolds 2011). Although the degree of ecosystem effects are dependent on the salmon species and the environmental context, the annual migrations of species of Pacific salmon can influence virtually all ecosystem components, from primary producers, invertebrates, and fishes in lakes and streams, to bears, eagles, and old-growth spruce trees (Piccolo et al. 2009). Nutrient subsidies to riparian ecosystems are greater for salmonid species that spawn in dense aggregations, such as Chum Salmon, Pink Salmon, and Sockeye Salmon, rather than at low densities, such as anadromous Rainbow Trout (Steelhead) and Coho Salmon (O. kisutch) (Figure 13.4) (Bilby et al. 2003).

An intriguing example of a potential indirect mutualism is the linkage between Pacific salmon and the forests surrounding their natal streams (Hay et al. 2004). The basic tenets are first that forested streams result in greater survival of embryos and newly emerged salmon, and thus support greater densities of young fish when compared with nonforested streams. This effect occurs through the input of nutrients from leaf litter and increased habitat complexity resulting from instream wood. Second, spawning runs of adult salmon import large quantities of marine-derived nutrients (nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus) into headwater streams and thus subsidize the growth of riparian trees. By their instream carcasses they also benefit benthic invertebrates that are preyed on by juvenile salmon, as well as directly benefiting juvenile salmon who feed on the adult carcasses (Figure 13.5) (Helfield and Naiman 2001; Piccolo et al. 2009). Instream nutrient subsidies by salmon are, however, somewhat counteracted by their physical disturbance of the streambed (Moore and Schindler 2008; Hocking and Reynolds 2011).

FIGURE 13.4. Pacific salmon migrations import large quantities of marine-derived nutrients into freshwater ecosystems. Picture shows decomposing head of a Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) along the shore of the Skokomish River, Washington. Photograph courtesy of Peter Bisson.

The positive effect of salmon on the riparian forest is further supported by a study using salmon carcasses placed in the floodplain and another study using a nitrogen tracer released in the riparian zone of a salmon spawning river (Drake et al. 2006; Gende et al. 2007). The study using salmon carcasses showed that they were providing nitrogen to soils adjacent to carcasses over the course of several months at concentrations capable of influencing plant growth (Gende et al. 2007). The tracer study showed that nitrogen amounts equivalent to those derived from salmon carcasses are taken up in the fall by the roots of riparian trees, especially Western Red Cedar, and allocated to leaves and stems the following spring (Drake et al. 2006).

The high densities of predators and scavengers that are attracted to salmon rivers for a few months each year provide a vector for moving the salmon-derived nutrients and energy upslope. In portions of Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington, primary movement of carcasses to the riparian zone occurs mainly by Brown Bears (Ursus arctos), Black Bears (U. americanus), and Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus); in more altered landscapes, such as the wine country of central California, domestic animals (dogs and cats) and also Raccoons (Procyon lotor), Opossums (Didelphis virginiana), and Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) play a similar role (Merz and Moyle 2006; Gende et al. 2007).

FIGURE 13.5. A possible indirect mutualism between Pacific salmon and components of the aquatic and riparian systems. Solid arrows show positive effects or increases; the dashed arrows show negative effects. *Some types of riparian vegetation do respond to marinederived nutrients (MDN) by showing increased growth but other species do not. Based on data from Drake et al. (2006) and Piccolo et al. (2009).

Although it is established that marinederived nutrients from Pacific salmon species can subsidize riparian vegetation, the importance of the subsidies in fostering plant growth and/or species composition is both species and site dependent (Wipfli and Baxter 2010). Where an effect occurs, it generally results in shifts in plant species composition away from those typical of nutrient-poor habitats to those typical of nutrient-rich habitats, with a concomitant reduction in species richness. However, the influence of salmon is always associated with other factors, including the canopy plant community, the size of the watershed, and the slope of the site. The greatest effects from salmon on riparian vegetation occur in small drainages having generally lower productivity (Hocking and Reynolds 2011). Impacts of salmon on watersheds where nitrogen and phosphorus are not limiting are no doubt less than in those where these nutrients are limiting. In addition, stream gradient and geomorphology can affect flushing rates, and increased flushing could reduce the residency time of salmon-derived nutrients. Because of their lower flushing rates, lakes may show a much longer response time over which marine-derived nutrients can be incorporated into the ecosystem (Piccolo et al. 2009).

The available information suggests that, at least in some instances, the fitness of Pacific salmon species is increased by a mutualistic feedback from riparian growth on stream habitat quality. In addition, the previously mentioned studies make it clear that conservation management of salmon species provides benefits that extend way beyond a catchable harvest for anglers (Merz and Moyle 2006).

MINNOW AND SUNFISH NESTS AND NEST ASSOCIATES Even though minnow and sunfish engineers are not subsidized by resources outside of their immediate ecosystem as is the case with salmon, their engineering products can be substantial. Occupied nests can be used as spawning sites by other species of fishes, especially minnows, and in fact, may be a requirement for the successful reproduction of many species (Wallin 1989). In addition, a single nest may be used by several or more associate species at the same time. Within the family Cyprinidae, at least 35 species are known to be nest associates (Johnston and Page 1992; Wisenden 1999).

Nest associates can gain improved reproductive success by spawning over host nests. Depending on the host species, eggs/larvae of nest associates benefit by being in the clean gravel afforded by the constructed nests, by protection against predation if the host guards the nest, and by possible aeration of the eggs by the host (Johnston and Page 1992; Johnston 1994a). Associates respond both to the nest and the presence of the host. In an experiment that consisted of constructing in two streams artificial gravel-mound nests that mimicked the actual nests of Bluehead Chub and Green Sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus), the artificial nests were not used by any of the numerous minnow species (including Central Stoneroller; Rosyside Dace; and Greenhead Shiner, Notropis chlorocephalus) that were observed spawning over nearby natural nests. In fact, once a host nest is constructed, it seems that the parental care by the host and not the physical environment of the nest is the major benefit to nest associates (Johnston 1994a).

Potential nest-building hosts can provide different services and risks to the associates, depending on the species. Minnow hosts do not defend the nest site once they are through spawning but also are not a predatory threat to the spawning associates. Even sunfish (Lepomis) hosts are generally not large enough to be a major threat to the associate species and also provide defense of the nest site for several weeks (Katula and Page 1998; Warren 2009). In contrast, nest associates of large piscivores such as Black Basses (Micropterus) and Bowfin (Amia calva) balance the apparent gain in defense of the nest by the host against the very real chance of being eaten by the host. For instance, Golden Shiner are apparently facultative nest associates of Bowfin, a large predator that routinely feeds on small fishes, including Golden Shiner, but which also offers aggressive and extended (ca. 9 days) defense of the nest site (Reighard 1903; Katula and Page 1998). In addition, at least three species of minnows, Golden Shiner, Common Shiner, and Taillight Shiner (Notropis maculatus), are known to spawn over nests of bass and would clearly be susceptible to bass predation but also gain extended protection of the nest by the host (Kramer and Smith 1960b; Johnston and Page 1992; Katula and Page 1998). Finally, there is an example of a large piscivore, Longnose Gar (Lepisosteus osseus), laying eggs over the nests of another piscivore, Smallmouth Bass, most likely during the night when the bass was inactive (Goff 1984). The gar eggs and larvae were vigorously defended by the resident Smallmouth Bass and young of both species seemed to have higher survival when together rather than alone. Thus nest associates and hosts represent a wide range of relative sizes, potential benefits, and potential risks to the spawning associates by the host species. Apparently no studies have rigorously examined the gain in offspring survival of the associates against the risk of predation by the host.

In some cases the relationship between associate and host is facultative. For instance, Topeka Shiner (Notropis topeka) is a nest associate with sunfish, including Green Sunfish and Orangespotted Sunfish (L. humilis). However, it will also spawn in the absence of sunfish nests, as shown by males selecting and defending spawning sites over sand substrata (Witte et al. 2009). In other cases the relationship between host and associate is obligate—Yellowfin Shiner do not reproduce in the absence of Bluehead Chub nests (Wallin 1989, 1992).

The relationship between host and associate is generally thought to be mutualistic, with a few exceptions where it is perhaps parasitic (Wisenden 1999). However, very few interactions have been adequately tested for benefits (or costs) to both hosts and associates. In one of the few studies to do this, Carol Johnston (1994a, b) first looked at the survival of the larvae of nest associates spawning over host nests, using Striped Shiner, which are nest associates of Hornyhead Chub, and Redfin Shiner (Lythrurus umbratilis), which are nest associates of Green Sunfish. The results clearly showed increased brood survivorship for both associates when in the presence of the host fish. Next, using a replicated mesocosm experiment, she tested the potential benefit that the host might gain from the associate, using the host Green Sunfish, the nest-associate Redfin Shiner, and an egg/larval predator (Longear Sunfish, Lepomis megalotis) (Figure 13.6). Somewhat surprisingly, the mean number of surviving Green Sunfish larvae in treatments with the host, associate, and predator did not differ from treatments with the host alone or with the host and associate. However, the number of surviving Green Sunfish larvae was reduced by 80% in experimental treatments of the host and the egg/larval predator in the absence of the associate. Hosts with associates had significantly higher reproductive success than those without associates, providing convincing support for a mutualistic relationship. The proposed mechanism for protection against predation was the selfish herd effect (see Chapter 12), the dilution of the host eggs by those of the associate. In fact, the number of host eggs was diluted 15% by eggs of the associate.

FIGURE 13.6. The benefit of a nest associate (A; Redfin Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis) to its host (H; Green Sunfish, Lepomis cyanellus), as shown by mean larval survival of Green Sunfish in the presence of an egg/larval predator (P; Longear Sunfish, L. megalotis). Vertical lines are 95% confidence intervals. Based on data from Johnston (1994b).

A possible example of a parasitic relationship between nest associate and host occurs with Dusky Shiner (Notropis cummingsae) and Redbreast Sunfish (Fletcher 1993). Dusky Shiners spawn over nests of Redbreast Sunfish, which can form large nesting colonies and actively defend their nests against intrusion by large schools of Dusky Shiner. Dusky Shiner schools generally entered a nest when the host was absent and tended to be near the edges of the sunfish colony where the likelihood of finding an unguarded nest was greater compared to nests in the middle of the colony. Dusky Shiner readily consumed eggs and larvae of Redbreast Sunfish, and an examination of gut contents of Dusky Shiner taken from over nests showed that almost all identifiable larvae were sunfish. Based on the usual school size and the number of larvae consumed by a single Dusky Shiner, there could be approximately 1000 sunfish larvae removed from the nest during one feeding episode. Dusky Shiner most likely were feeding opportunistically and may have selected sunfish larvae because of their larger size. Although the apparent decrease in reproductive success of the host due to Dusky Shiner predation on eggs and larvae strongly suggest a parasitic relationship, actual parasitism cannot be definitively shown until the overall reproductive cost to the host is determined. Although unlikely, the decreased survival of sunfish eggs/larvae from shiner predation could be compensated for by the presence of the associate, perhaps via the selfish herd effect.

Species Associations and the Potential for Other Forms of Facilitation

Proposed benefits from interspecific aggregation include increased foraging efficiency and enhanced detection and avoidance of predators. Early warning benefits in mixed groups are well known in some organisms such as birds (Boucher et al. 1982; Thompson and Thompson 1985) and also fishes (Chapter 12). Fishes in monospecific shoals are able to quickly transmit information about a predator. In an experiment with European Minnows (Phoxinus phoxinus), one group of minnows (the transmitter minnows) was exposed to a model of a Northern Pike (Esox lucius) while a second group of minnows (the receiver minnows) could only see the transmitter minnows but not the predator. When the transmitter minnows were exposed to the predator model, fish in the receiver group responded by hiding and/or reduced activity—behaviors associated with predator avoidance (Magurran and Higham 1988). For early warning to be effective in mixed-species shoals, the information must also be transmitted rapidly (Godin et al. 1988), something that may be less likely among different species. However, by joining mixed-species groups, fishes could reap the benefits of being a member of a larger group (increased vigilance and reduced probability of predation) yet reduce the cost of intra-specific competition to less than it would be in an equally large group of conspecifics, assuming that predator evasion maneuvers would not be impeded by heterospecifics during an actual predator attack (Allan 1986; Pitcher 1986). Also, rare species might persist by virtue of hiding within schools of more abundant heterospecifics (Moyle and Li 1979). Based on studies done in an artificial stream, three sympatric European cyprinids that frequently associate in shoals, Dace (Leuciscus leuciscus), European Minnow, and Gudgeon (Gobio gobio), showed a balance between avoiding identical resources while remaining close enough to the other species to gain antipredation benefits from the appearance of a large shoal (Allan 1986). If all species in a mixed-species shoal would benefit to some degree, the interaction could be termed facultatively mutualistic; however, such fitness benefits have not yet been shown.

Suggestions of potentially facilitative or mutualistic interactions among mixed species of freshwater fishes are not new. Often observing fishes with field glasses while sitting on a railroad trestle over a stream, Jacob Reighard (1920) provided careful descriptions of feeding interactions between minnows and both the Northern Hogsucker (Hypentelium nigricans) and White Sucker. He also commented that he had observed White Sucker to be much less easily startled when accompanied by a group of Logperch (Percina caprodes). Although based only on visual observations, Reighard suggested enhanced feeding and safety as benefits from mixed-species groupings. Reighard’s observations have since been extended by underwater observations of Blacktail Shiners and Northern Hog Sucker in a clear upland stream in Mississippi. Blacktail Shiners commonly followed closely behind large Northern Hog Suckers, and were observed feeding on invertebrates suspended by benthic disturbance caused by feeding actions of the Northern Hog Sucker (Baker and Foster 1994). In this relationship, the larger, benthic feeding sucker might also benefit by receiving early warnings of a threat if the smaller shiners responded to a potential predator. If it turns out that the interaction is beneficial to both participants, then the sucker-minnow tandem could represent a true mutualism.

Similar feeding associations have been observed among pairs of minnows and also darters. For instance, Bigeye Shiners (Notropis boops) swim above schools of benthic-foraging Ozark Minnows (N. nubilus), apparently feeding on items that are suspended in the water column by the benthic forager. The same pattern occurs with Hornyhead Chubs following the benthic algivore, Central Stoneroller (Gorman 1988a). Similarly, Gilt Darter (Percina evides) commonly follow two other darters, Logperch and Blotchside Logperch (P. burtoni), feeding on items exposed when the logperches flip over stones (Greenberg 1991). Overall, mixed feeding groups of fishes are apparently common. Various minnow species frequently form mixed schools, with individuals of one species following and responding to individuals of another species (Mendelson 1975; Copes 1983). Shoals of mixed species are also known among centrarchids, including species that can also interact as predator and prey as the size differential between them increases. In Florida canals, Largemouth Bass ≤ 30 cm TL and similarly sized Bluegill form mixed-species foraging groups of around five individuals that interact in hunting small poeciliids and cichlids (Annett 1998).

COEVOLUTION: DIFFUSE AND DIRECT

Thus far, this chapter has covered forms of facilitation, mutually positive or positive-neutral interactions among species. The topic of this section relates to a set of mechanisms, coevolution, potentially responsible for the interactions. Coevolution is not synonymous with mutualisms, species interactions, or symbiosis (Janzen 1980). Most basically, it constitutes “an evolutionary change in a trait of the individuals in one population in response to a trait of the individuals of a second population, followed by an evolutionary response by the second population to the change in the first” (Janzen 1980). As such, coevolutionary responses are widespread in evolution and potentially could include various forms of facilitation as well as resource divergence between species and predator-prey (including parasite-host) interactions; however, such interactions cannot be assumed due to coevolution (Janzen 1980; Thompson 2005, 2009). In fact, coevolution is difficult to prove and, even if interactions among species are coevolutionary responses, they could be a consequence of coevolution with organisms no longer present in their habitat (recall the disparate ages of major groups of North American freshwater fishes; Chapter 2) (Janzen 1980).

Forms of Coevolution and Eco-Evolution

Coevolutionary interactions can occur between tightly coupled species pairs (i.e., pairwise coevolution), where the evolution of a given trait in one species produces a subsequent evolution of a trait in the other, resulting in selective pressure producing further modification of the trait in the first species, and so on (Ehrlich and Raven 1964). Coevolution occurring in multispecies interactions was termed diffuse coevolution by Daniel Janzen (1980), and the fact that communities can evolve by virtue of overall contacts among species, without involving reciprocal evolutionary steps by all species, is presently considered an important aspect of coevolution (Inouye and Stinchcombe 2001; Thompson 2009).

The understanding that most species are collections of genetically distinct populations, that levels of selection often vary among the populations, and that consequently, the type and strengths of interactions among species should also be expected to vary, has led to the development of the geographic mosaic theory of coevolution (Thompson 1994, 1999a, 1999b, 2005, 2009; Gomulkiewicz et al. 2000; Nuismer et al. 2003). This much more realistic appreciation of species’ populations leads to the view that interactions coevolve as geographic mosaics and that such interactions are continually modified across ecosystems (Thompson 2009). Because of this, one population within a species might be coevolved with another species, yet other populations of the same species would not necessarily show the same relationship.

It is well understood that natural selection resulting from ecological changes affects evolutionary changes in organisms over long and short time scales (Gould 2002; Schoener 2011). It is also well documented that evolutionary changes over long time periods (i.e., evolutionary time scale) have important consequences for ecological communities (Schoener 2011). However, studies of community ecology, such as resource separation among species (Chapter 11) or food web interactions (Chapter 12), typically consider species as static units that are not composed of locally evolving populations. The appreciation that evolutionary dynamics are affecting communities in “ecological time” is much more recent and has occurred because of the understanding that evolution can occur over ecological time scales. The interaction between ecology and evolution within an ecological time frame is referred to as eco-evolutionary dynamics, with the major precept that both directions of effect, ecology to evolution and evolution to ecology, are substantial (Johnson et al. 2009; Schoener 2011). The recognition of the interplay of short- and long-term evolutionary processes with a matrix of ecological interactions among species is currently leading to an exciting link between community ecology and evolutionary biology, although few studies as yet have documented the strength of the evolution to ecology pathway (Johnson and Stinchcombe 2007; Schoener 2011).

Obviously, one important requirement for such interaction to occur is that there is rapid evolution—evolutionary change that occurs on an ecological time scale (Schoener 2011). Other things being equal, rates of evolutionary change should increase as a function of shorter generation time. For instance, some livebearing fishes such as Least Killifish (Heterandria formosa) and Western Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) can produce several generations per year, and Red Shiner (Cyprinella lutrensis), as well as various other small cyprinids, can reproduce in their first summer of life, resulting in two generations per year (Henrich 1988; Haynes and Cashner 1995; Marsh-Matthews et al. 2002). Many other small-bodied fishes (minnows, topminnows, and some sunfish) reproduce when they are a year old (Ross 2001). Another set of requirements for eco-evolutionary interactions to occur is that a population shows genetic variation in traits, that traits respond to directional selection, and that the selection has an effect on a community variable (Johnson et al. 2009). As an example of rapid genetic change to directional selection, Red Shiner populations near cold-water releases from dams showed increased heterozygosity compared to populations in unaltered environments within a span of 50 years (Zimmerman and Richmond 1981). Mosquitofishes (Gambusia spp.), introduced to Hawaii in 1905, showed heritable differences in life-history traits in populations from thermally stable versus thermally variable reservoirs over a span of 70 years and approximately 140 generations (Stearns 1983). In a small northern California stream, individuals from an anadromous population of Rainbow Trout (Steelhead) were transplanted by humans above a waterfall some 100 years ago. The population above the falls shows a strong tendency for a resident life-history pattern and has diverged genetically from the source population below the waterfall to the extent of showing reproductive isolation from the source population (Pearse et al. 2009).

Whether or not the suggested mutualisms treated earlier in this chapter or in previous chapters have been shaped by coevolution or are simply fortuitous interactions is difficult to discern. The well-studied divergence of benthic and limnetic forms of Pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) and Threespine Sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) (see Chapter 11) provides an example of pairwise coevolution via resource competition (Robinson et al. 1993; Schluter 2010). However, resource differences among species in many systems, especially in small streams, is likely due more to phylogeny or to environmental disturbances such as droughts and floods than by closely evolved interactions among species (Grossman and Freeman 1987; Grossman and Ratajczak 1998).

As yet, surprisingly little is understood about the importance of coevolution in shaping how ecosystems function. In a landmark study using Trinidadian populations of Giant Rivulus (Aplocheilidae: Rivulus hartii; mean body mass 0.75 g) and Guppy (Poeciliidae: Poecilia reticulata; mean body mass 0.15 g), Palkovacs et al. (2009) compared the effects of Guppy introduction, Guppy evolution (using populations that evolved with low and high predation risks), and Giant Rivulus-Guppy coevolution on food webs, including invertebrate biomass. Locally coevolved populations were more efficient at exploiting invertebrates compared to populations of Giant Rivulus and Guppy that were not coevolved. This was perhaps due to selection for enhanced competitive ability in the coevolved populations for exploitation of a shared resource. The results from this study show that coevolution of local populations may play a critical role in shaping ecological processes over contemporary time scales.

Longevity of Species Associations

Material in Part 1 would indicate that species composing local assemblages are often of widely different evolutionary ages and origins and that fish assemblages have gained and lost species over evolutionary time scales. Consequently, the probability of a suite of species remaining together over long periods of time (i.e., thousands of years) is no doubt low, a conclusion also supported by others (Matthews 1998, Chapter 9). Especially for pairwise coevolution to occur, the interacting species need to remain associated for a substantial period of time, should have high encounter rates, and have strong interspecific interactions (Thompson 1982; Futuyma and Slatkin 1983; Price 1984; Farrell and Mitter 1993; Brown 1995). Of course, what constitutes a substantial period of time, a strong interaction, or a physically close association likely varies widely among taxa. Habitat availability would seem an important factor in fostering close association of species. Certain habitats, like deep pools or lakes, can be critical to the stability of a fish community (Schlosser 1987; Fausch and Bramblett 1991; Lohr and Fausch 1997). Whether fishes congregate consistently in a particular kind of habitat because of past coevolution of traits or because of independently acquired traits, the likelihood of future trait modification by coevolutionary interactions is increased if they now co-occur in regular, direct contact. What is generally absent in discussions of coevolution is actual evidence on how long (months, years, or millennia) patterns of direct contact among mobile species in real-world communities must persist to provide a consistent template within which interspecific genetic adjustments of traits, hence local coevolution, can occur (Ross and Matthews, in press). Among other plant and animal taxa, certain coevolved relationships are thought to be quite old or to have developed over millions of years of intimate contact, as in the case of the obligate, mutualistic relationship between fungus-growing ants and the cultivated fungus (McNaughton 1984; Currie et al. 2003). However, other studies indicate that coevolutionary interactions among species can develop over much shorter time periods (e.g., decades) (Thompson 2005). Consequently, observations of persistent contacts among fish species within an ecological time scale can be pertinent to evolutionary processes for species and communities (Chapter 6, Persistence stability of local associations).

SUMMARY

Species interactions that are mutually positive, or asymmetrically positive and neutral, are important in fish assemblages and aquatic ecosystems in general. Close associations of fish species in various kinds of habitats suggest the potential for such interactions to develop, although our understanding of how common positive or positive/neutral associations occur is still limited.

Facilitative interactions can occur through the presence of foundation species or through the activity of ecosystem engineers, although activities of ecosystem engineers can benefit some species more than others. Beavers represent important ecosystem engineers responsible for creating extensive lentic habitat patches in upland streams. The decline of Beavers as a consequence of trapping, likely had major impacts on fish habitats and the occurrence of fish species in low-order streams. Fish species that construct various types of gravel or pebble nests are also ecosystem engineers, and their nests provide nesting habitat for nest associates. Some nest hosts also contribute to the survival of young of the nest associates through nest guarding.

Mutualisms occur at various levels in fish assemblages and aquatic systems. Pacific salmon import huge quantities of marine-derived nutrients into streams, and such nutrients can benefit instream productivity and also riparian vegetation. A mutualistic response occurs if increased riparian vegetation improves stream conditions for the Pacific salmon. Interactions of nest associates and hosts also can be mutualistic if the associates increase the fitness of the hosts. One mechanism would be that the young of the associates dilute the impact of predation on the young of the hosts. Mixed associations of fishes can also be mutualistic, such as when the collective group vigilance increases the time available for foraging by individual members rather than sacrificing feeding time to vigilance.

The understanding that evolutionary changes in local fish populations can occur on an ecological time scale has contributed to the development of eco-evolutionary dynamics, as has the geographic mosaic theory of coevolution. Especially in populations with short generation times and thus high turnover, rapid evolutionary responses are likely and could lead to shifts in behaviors with consequent impacts on aquatic ecosystems.

SUPPLEMENTAL READING

Boucher, D. H., S. James, and K. H. Keeler. 1982. The ecology of mutualism. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 13: 315–47. A historical account of mutualism with suggestions for appropriate use of terms.

Johnston, C. E. 1994. Nest association in fishes: evidence for mutualism. Behavioral Ecology 35:379–83. One of the few studies to clearly demonstrate the benefit of nest associates to the nest-building host species.

Palkovacs, E. P., M. C. Marshall, B. A. Lamphere, B. R. Lynch, D. J. Weese, D. F. Fraser, D. N. Reznick, C. M. Pringle, and M. T. Kinnison. 2009. Experimental evaluation of evolution and coevolution as agents of ecosystem change in Trinidadian streams. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 364:1617–28. A landmark paper, based on years of supportive research, that shows how locally coevolved populations have different impacts on ecosystems than noncoevolved populations of the same species.

Pollock, M. M., M. Heim, and D. Werner. 2003. Hydrologic and geomorphic effects of Beaver dams and their influence on fishes, 213–33. In The ecology and management of wood in world rivers. S. Gregory, K. Boyer, and A. Gurnell (eds.). American Fisheries Society Symposium 37, Bethesda, Maryland. An excellent review of the past and present impacts of Beaver dams, and their widespread removal.

Power, M. E., D. Tilman, J. A. Estes, B. A. Menge, W. J. Bond, L. S. Mills, G. Daily, J. C. Castilla, J. Lubchenco, and R. Paine. 1996. Challenges in the quest for keystones. BioScience 46:609–20. An important paper clarifying the relationship between foundation species (or dominant species) and ecosystem engineers (or keystone species).

Schoener, T. W. 2011. The newest synthesis: Understanding the interplay of evolutionary and ecological dynamics. Science 331:426–29. A current synopsis of the eco-evolutionary interactions.

Wipfli, M. S., and C. V. Baxter. 2010. Linking ecosystems, food webs, and fish production: subsidies in salmonid watersheds. Fisheries 35:373–87. A broad look at food sources, including marine-derived nutrients, and food webs in streams.