FOURTEEN

Streams Large and Small

CONTENTS

Hydrologic Cycles and Fish Assemblages:

Importance of a Variable Flow Regime

Flow, Temperature, and Movement Patterns

Hydrologic Cycles and Fish Assemblages:

Dam Removal, Fish Passages, Environmental Flows, and Other Remedial Approaches

Regaining Natural Flow Characteristics

Reconnecting Floodplains and Streams

Restoring Connectivity of Watersheds

Darwinian Debt and Other Issues

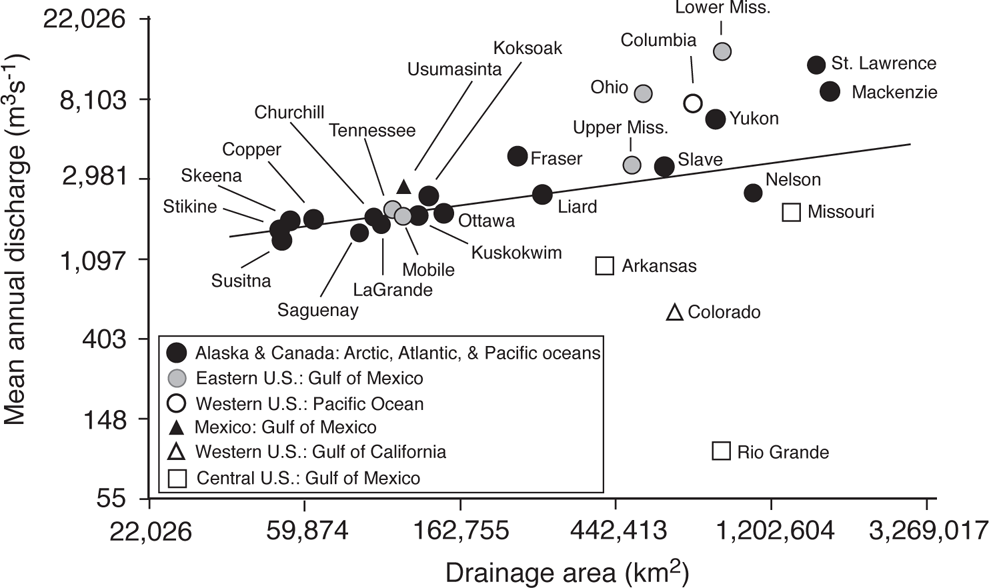

STREAMS AND RIVERS CONSTITUTE a major feature of the North American landscape—indeed, much of North American topography has been shaped by the impacts of flowing water on the erosion and deposition of materials (Leopold et al. 1964; Leopold 1994; Mount 1995). North American streams and rivers collectively discharge approximately 8,200 km3 (580 billion gallons) each year, which is about 17% of the world’s total. Although there is a general relationship between the area of the watershed and the annual mean discharge (Leopold 1994), rivers in arid lands have discharges much lower than would be predicted by watershed area, whereas those in regions with high precipitation have annual discharges that are much greater (Figure 14.1). For instance, of 28 of the largest North American rivers, those with watersheds in Alaska, Canada, the Pacific Northwest, and subtropical Mexico have mean annual virgin discharges (i.e., the estimated discharge prior to human modifications) close to or above the regression line. In contrast, those in the arid central and western United States have discharges much lower than predicted by drainage area, with the most extreme being the Rio Grande, which has the sixth largest area but the lowest discharge among the 28 large rivers. Rivers in arid regions are particularly subject to droughts as well as periodic flooding with concomitant challenges to fishes and other aquatic organisms.

No matter where they occur, large rivers in North America and elsewhere in the world are now highly modified by humans through damming, water diversions, introduction of nonindigenous species, and various forms of water pollution. Over half of the world’s large rivers (i.e., those with virgin mean annual discharge of at least 350 m3s−1) are strongly affected by dams (Nilsson et al. 2005). Of the 74 large North American rivers, 39 (53%) are moderately to strongly affected by impoundments or flow regulation (Dynesius and Nilsson 1994). In North America, rivers that are not strongly impacted by human alterations are disproportionately located in areas of low human-population density—extreme northern areas of Alaska and Canada. In fact, only one of the 35 rivers not strongly affected by human alterations is located in temperate North America—the Pascagoula River located in Mississippi and Alabama (see also Jackson 2012). At the other extreme, the Colorado River is one of the world’s most regulated rivers, with impoundments capable of storing and releasing more than 2.5 times the annual flow (Nilsson et al. 2005). Even in regions of North America where water has long been considered an abundant resource, such as the eastern United States, increasingly rapid human population growth is now exerting stressful demands on the available water (Freeman and Marcinek 2006).

FIGURE 14.1. A log-log plot of the relationship between mean annual virgin discharge and drainage area for 28 large North American rivers. The angled line is a regression fit to a log-log plot (r = 0.31); for clarity the numbers on the x and y axes are shown as untransformed values. Based on data from Benke and Cushing (2005).

The future of aquatic habitats and organisms in North America, as is true elsewhere, is closely linked to patterns of human population growth, and particularly to per capita demands on water use as well as the release of greenhouse gases (Meffe and Carroll 1997). There are a number of threats to aquatic biodiversity, including increasing demands for water and associated corollaries of impoundments and withdrawals, declines in water quality, channelization, levees, the introduction of nonindigenous species, and impacts of global climate change. Although all are important, increasing demands for water and changes to natural flow patterns are certainly major concerns and are the topic of this chapter. Impacts of nonindigenous species are covered in the following chapter.

HYDROLOGIC CYCLES AND FISH ASSEMBLAGES

Natural Patterns

The development of aquatic and riparian ecosystems is closely tied to the hydrologic regime, and daily or seasonal variations in stream discharge can have major impacts on the behavior and ecology of aquatic organisms (Richter et al. 1996; Poff et al. 1997; Bunn and Arthington 2002). Patterns of flow can vary in their timing, magnitude, duration, frequency, and rate of change, and this variation has numerous direct and indirect effects on the integrity of the stream ecosystem (Box 14.1). The magnitude of flow, among other things, controls access to floodplain resources, and in western rivers that are driven by snowmelt, magnitude changes drastically over time. Flow variation can act directly on ecological integrity, or indirectly via primary regulators of ecological integrity, including physical habitat, water quality, primary and secondary productivity, and biotic interactions (Figure 14.2). In spite of its importance to aquatic communities, the extent of short-term variations in stream depth, flow velocity, and water quality (including temperature) often surprise many biologists accustomed to thinking of stream characteristics on a monthly or seasonal basis coincident with fish or invertebrate sampling, especially when dealing with small streams.

FIGURE 14.2. The flow pattern of streams is the master regulator of the ecological integrity of the stream ecosystem. Patterns of flow can act directly on ecological integrity or indirectly through other primary regulators. Based on Poff et al. (1997).

BOX 14.1 • Defining the Master Variable

Knowing basic hydrologic characteristics of a stream is fundamental to an understanding of fish life histories, fish-habitat relationships, and fish assemblage structure and persistence. This “master variable” of stream flow can be described by five main components: magnitude, frequency of occurrence, timing, flashiness, and duration, each of which can include several or more different measurements (Richter et al. 1996; Poff et al. 1997; Lytle and Poff 2004).

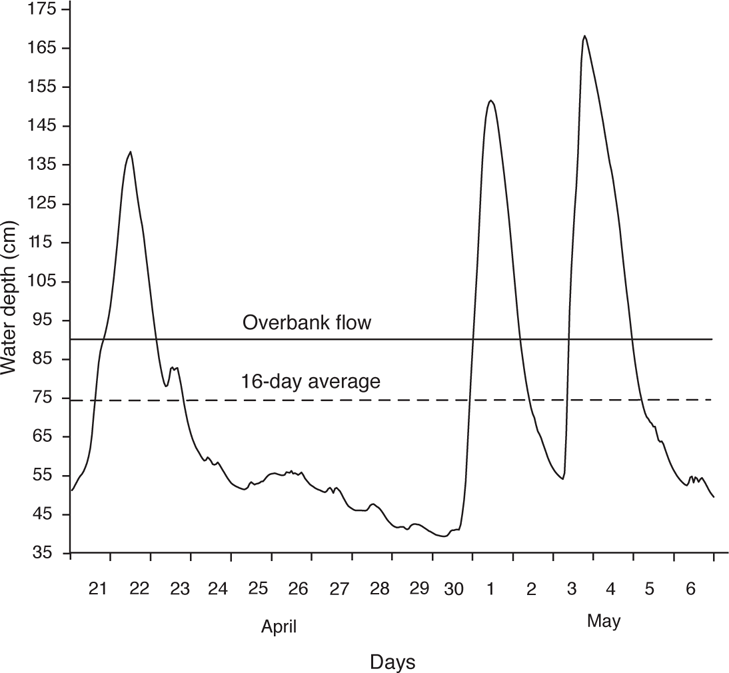

MAGNITUDE A measure of water condition, such as the amount of water moving past a fixed point per unit time (e.g., cubic meters per second), or some other measure of amount, such as water depth or a relative measure such as the amount of water relative to bank-full depth. Magnitude provides a measure of habitat availability and is often given in monthly averages of daily values. In the following figure, magnitude could be expressed as the 16-day mean, or simply by the line showing water depth.

FREQUENCY OF OCCURRENCE A measure of the pulsing behavior of flow—that is, how often a flow above or below a given magnitude occurs over a given time interval. In the figure below, there are three pulses above over bank flow within 16 days. Frequency usually shows an inverse relationship with magnitude, indicating the increasing rarity of high magnitude flows.

TIMING The date when the highest and lowest flows (or intermediate flow events) occur; usually expressed on an annual cycle. Over annual cycles, the timing of flow events (either high or low) can occur during the same months (high predictability) or over different months (low predictability).

FLASHINESS A measure referring to the rate of change in flow conditions from one magnitude to another. The example shows a flashy stream, with water depth changing from 39 to 40 cm on the morning of April 30 to a peak of 151 cm by noon the following day. Also, the first two high-flow events have an interval of only nine days.

DURATION A measure of how long specific flow conditions last. Duration can be expressed as the number of days a particular flow is exceeded (such as the number of days per month or year of overbank flow) or as the length of time a particular flow event occurs. In the example figure, the overbank flows lasted from 1 to 1.5 days. On an annual cycle, overbank flows in Beaverdam Creek from 1992 to 1994 averaged 43 hours (Slack 1996).

Short-term flow variation (water depth) in Beaverdam Creek, a small headwater stream in southeastern Mississippi. Based on unpublished data from W. T. Slack and S. T. Ross.

Importance of a Variable Flow Regime

Rises in stream discharge of sufficient magnitude and duration can trigger upstream or downstream movement of fishes, provide potential access to new habitats, rescue stranded populations in cut-off pools, or provide access to refuges during high flood events (Albanese et al. 2004). In addition, seasonally variable flow patterns provide increased food resources in the channel and also provide access to food and habitat resources on river floodplains, those areas that are periodically inundated by lateral overflow of rivers, lakes or reservoirs, by groundwater, or by direct precipitation. Importantly, streams and rivers and their associated floodplains should be considered as functional units and not as separate entities because they are tightly linked in terms of water, sediment, and organic matter exchanges (Junk et al. 1989; Junk and Wantzen 2004).

The river-floodplain system includes the main channel, permanent lakes and ponds on the floodplain, and the periodically inundated floodplain habitats. The temporally variable patterns in magnitude and frequency create pulses of overbank flow. The flood-pulse concept (FPC), proposed by Junk et al. (1989), considers annual flooding events as the principal factor responsible for the “existence, productivity, and interactions of the major biota in river-floodplain systems.” The FPC is a general concept for large river-floodplain systems in temperate as well as tropical habitats, and a major tenet is that much of the primary and secondary production of these systems takes place on the floodplain, with the river channel viewed as a transport mechanism for water and dissolved/suspended matter, a corridor for the movement of aquatic organisms, and as a refuge for aquatic organisms during periods of low flow (Junk and Wantzen 2004).

Flow, Temperature, and Movement Patterns

The timing of life-history events, such as spawning migrations, actual spawning, and embryo, larval, and adult growth and survival, are related to seasonal environmental changes, in particular day length acting in conjunction with changes in water temperature and rising or falling water levels (Leggett 1977; Helfman et al. 2009). For instance, in California’s Sacramento-San Joaquin River system, most Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) time their migration into fresh water with the high flows generated by fall and winter rains, and also take advantage of the associated low water temperatures for spawning. For both Chinook Salmon (O. tshawytscha) and Steelhead in this system, water temperatures have profound impacts on growth and survival, with very narrow temperature tolerances, especially in the embryonic and early juvenile stages. In general, different stocks of Steelhead and Pacific salmon along the Pacific coast are adapted to different water temperature regimes (Myrick and Cech 2004). In the Columbia River, the timing of upstream migration of native Sockeye (O. nerka) and Chinook salmon, as well as the nonindigenous American Shad (Alosa sapidissima), are correlated primarily with water temperature and perhaps secondarily to spring discharge (Quinn and Adams 1996).

In tributaries of the Wabash River, Indiana, nine species of suckers in the genera Carpiodes, Catostomus, Erimyzon, Hypentelium, and Moxostoma show a seasonal progression of occurrence on spawning bars that is related to changes in water temperature and stream discharge (Curry and Spacie 1984). Similarly, the appearance of larvae of Flannelmouth (Catostomus latipinnis), Bluehead (C. discobolus), and Razorback (Xyrauchen texanus) suckers; Colorado Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius); and Speckled Dace (Rhinichthys osculus) in the San Juan River of the Colorado River system occurs progressively during the year in relation to rising water temperatures and a rising and then falling spring hydrograph (Figure 14.3). Of course, actual spawning and hatching dates of fishes predate the occurrence of protolarvae or mesolarvae (the two earliest larval stages) by a matter of days or weeks (Box 14.2). In the case of Razorback Sucker, over a 12-year period, hatching and emergence from gravel spawning bars included periods prior to spring runoff or a portion of the ascending limb of the hydrograph. One-third of the time, hatch dates also extended into the descending limb of spring runoff. In general, the native suckers initiate spawning earlier in the season, usually during a rising hydrograph and rising water temperatures, compared to the native minnows (Speckled Dace and Colorado Pikeminnow), which spawn during a falling hydrograph but still rising water temperatures (Brandenburg and Farrington 2011). Colorado Pikeminnow in the free-flowing Yampa River, Colorado, also spawned as flows were decreasing and as temperatures reached 22–25° C (Tyus 1990).

BOX 14.2 • Larval Occurrence and Spawning or Hatching Dates

Environmental conditions during fish spawning, embryo development, and larval emergence (generally coinciding with hatching followed by first feeding) are highly important in the understanding of fish recruitment patterns and the relationship of spawning and survival to environmental conditions (see also Chapter 9). However, in most instances, the actual dates of spawning, emergence, or hatching are not directly observable. Although the occurrence of eggs or larvae gives an approximation of spawning and hatching dates, egg capture or larval presence can postdate spawning and hatching by days or even weeks, depending on the species and environmental conditions. For instance, Bloater larvae (Coregonus hoyi) in Lake Michigan generally occur in the hypolimnion 10 or fewer days following the initiation of exogenous feeding (which occurs around three days after hatching), but in the epilimnion, some larvae were 55 days beyond the initiation of first feeding (Rice et al. 1987).

Dates of hatching of many fishes, and thus environmental conditions, such as temperature or stream discharge, near the time of spawning and at the time of emergence from spawning areas, can be determined by back-calculations based on the size or age of fishes at known capture dates. The most straightforward approach is to determine the actual age (in days) of fish—which, combined with a known date of capture, readily provides the age at hatching or first feeding. For example, this approach was used in a northern population of Brook Silverside (Labidesthes sicculus) based on the determination of daily growth bands in otoliths of juvenile and adult fish (Powles and Sandeman 2008). In another case, spawning dates for White Sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) in the Kootenai River, Idaho, were back-calculated from the dates of capture of fertilized eggs on spawning mats (White Sturgeon spawn in the water column and have demersal adhesive eggs), determining the developmental stage of the viable eggs and knowing, from other studies, the relationship of embryo stage and developmental time (Paragamian et al. 2002).

In the San Juan River of Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, Razorback Sucker (Xyrauchen texanus) appeared in the ichthyoplankton from May 17 to June 20, 2010 (see Figure 14.3). Larvae hatch 6–7 days after fertilization at 18° C and begin initial feeding nine days after hatching. At 16.5° C, the growth rate of larval Razorback Sucker is around 0.35 mm per day. Consequently, hatching dates can be back-calculated by subtracting the average length of larvae at hatching (8.0 mm TL) from the length at capture, and then dividing by the average growth rate at an appropriate water temperature (i.e., 0.35 mm per day at 16.5° C). Using this approach, in 2010, Razorback Sucker hatching dates ranged from April 28 to June 11. Furthermore, because the larvae hatch 6–7 days postfertilization (Bestgen 2008), actual spawning likely occurred from April 21 to June 4. Because river discharge and temperature during spawning, hatching, and larval occurrence vary considerably, being able to back-calculate more exact dates is important for understanding spawning requirements and success (Brandenburg and Farrington 2011; Howard Brandenburg, Mike Farrington, and Steve Platania, unpublished data 2011).

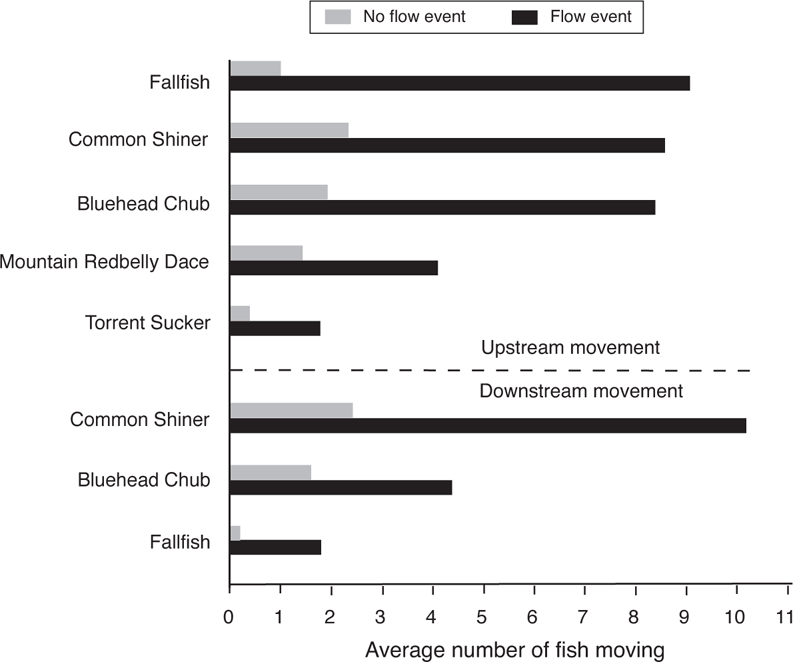

In a study of movement of eight fish species (families Cyprinidae, Catostomidae, Ictaluridae, and Cottidae) in small streams in the James River drainage, Virginia, five species showed increased movement rates in association with high flow events (Figure 14.4) (Albanese et al. 2004). Movement was based on the number of fish moving past bidirectional fish traps (e.g., traps that captured fishes moving both upstream and downstream). Although more species showed upstream movements, downstream movement occurred as well. Voluntary flow-mediated movement within stream channels (in contrast to passive displacement by flood waters or lateral movement onto floodplains) is extremely widespread among North American freshwater fish families, including fishes in the families Acipenseridae, Polyodontidae, Cyprinidae, Catostomidae, Ictaluridae, Salmonidae, Gasterosteidae, and Centrarchidae (Leggett 1977; Schlosser 1995b; Albanese et al. 2004; Heise et al. 2005; Gerken and Paukert 2009).

FIGURE 14.3. River discharge, temperature, and the occurrence of native fish larvae in the San Juan River in 2010. Temperature and discharge data are based on USGS gauge 09379500, near Bluff, Utah. Rectangles show the occurrence of larvae for five native fish species. The light gray bars are sampling trips. RS = Razorback Sucker (Xyrauchen texanus); FS = Flannelmouth Sucker (Catostomus latipinnis); BS = Bluehead Sucker (C. discobolus); SD = Speckled Dace (Rhinichthys osculus); CP = Colorado Pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius). Based on data from Brandenburg and Farrington (2011) and unpublished data from Howard Brandenburg, Mike Farrington, and Steve Platania.

The Pascagoula River, Mississippi, supports a population of Gulf Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi), a large anadromous fish that feeds in coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico and which spawns in coastal rivers along the northern and eastern Gulf of Mexico. The return migration into fresh water occurs over a narrow time period in February and March, with fish reaching their spawning site approximately 250 river km upstream from the Gulf Coast by mid-April (Heise et al. 2004; Ross et al. 2009). Similar patterns of movement occur in other populations of Gulf Sturgeon (Fox et al. 2000). Rising water temperature is no doubt an important cue, but upstream movement is also related to rises in stream discharge (Heise et al. 2004).

Gulf Sturgeon leave fresh water in the fall and the timing of the out-migration is associated with seasonal cues, including shorter day lengths and declining water temperatures, but once these conditions are appropriate, the actual trigger for movement seems to be spikes in river discharge. In a drought year, Gulf Sturgeon out-migration from the Pascagoula River, Mississippi, occurred much later than in years with higher fall flows (Heise et al. 2005). On the Pacific coast, Green Sturgeon (A. medirostris) also move out of fresh water as a function of dropping water temperature and increases in discharge (Erickson et al. 2002).

Upstream spawning migration of the Splittail (Pogonichthys macrolepidotus), a cyprinid endemic to the San Francisco Estuary and associated rivers, is triggered by spikes in river flow during the winter. High flows are also required to attract fish to floodplain habitats that are used for spawning and for nursery areas (see also Chapter 6) (Feyrer et al. 2006). Similarly, upstream spawning migration of Colorado Pikeminnow in the free-flowing Yampa River, Colorado and Utah, is apparently triggered by discharge and perhaps temperature, occurring about a month following the highest spring flows at water temperatures above 9° C (Tyus 1990).

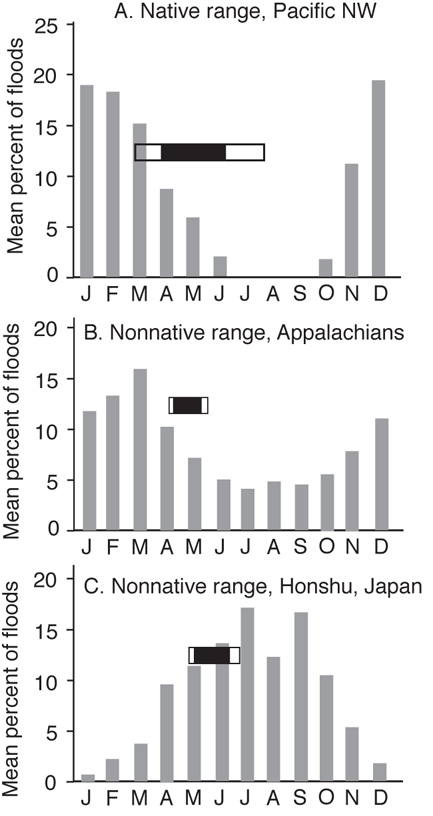

Flow characteristics, especially timing, magnitude, and duration, can have major impacts on the survival of eggs and larvae and thus drive population success or failure (see also Chapter 5). For instance, newly emerged fry of Rainbow Trout (O. mykiss) are highly vulnerable to downstream displacement and mortality caused by flooding. In the Pacific Northwest, their native range, Rainbow Trout spawn in late winter to early spring and the fry emerge from the redds during late spring to early summer. This timing of fry emergence generally follows months with high likelihoods of floods—illustrating the importance of the timing and magnitude of flow on population success (Figure 14.5A) (Fausch et al. 2001). However, Rainbow Trout are one of the most widely transplanted fish species, and their invasion success is often hard to predict (MacCrimmon 1971, 1972). Fausch et al. (2001) compared flow regimes among five Holarctic regions where Rainbow Trout are native or have been introduced, including regions where introductions have been highly successful (Southern Appalachians and Colorado—prior to the whirling disease epidemic), moderately successful (Hokkaido Island, Japan), and unsuccessful (Honshu Island, Japan). The principal hypothesis was that Rainbow Trout invasions would be successful when flow regimes most closely matched those in the native range (i.e., emergence of fry following high flows), and least successful when high flows overlapped with or followed the period of fry emergence. The results supported the hypothesis that invasion success related to the match between the timing of fry emergence and months with low probability of flood disturbance. In the Pacific Northwest and in the southern Appalachians, floods are caused by winter rains and flows drop to base levels by early summer (Figure 14.5A, B). Fry emergence occurs during a period of declining flows. Streams on Honshu Island, where invasion of Rainbow Trout has been unsuccessful, have flooding caused by summer monsoonal rains followed by typhoons in the fall. Consequently, there is a high likelihood of flooding from April through October. Fry emerge in May and June, preceding rather than following months with the highest percentage of flooding (Figure 14.5C). Flooding of Hokkaido streams is a factor of melting snow in late spring and the likelihood of typhoons in early fall. In contrast to the Honshu Island trout, the emergence of fry occurs in a two-month slot after the end of snowmelt and before increased chances of typhoons (Figure 14.5D). Finally, Colorado streams are driven primarily by snowmelt and have highly predictable flows. Rainbow Trout emergence extends from June through late July when the likelihood of flooding is rapidly declining (Figure 14.5E).

FIGURE 14.4. The effect of short-term flow events on the movement of stream fishes in the James River drainage, Virginia. Based on data from Albanese et al. (2004).

FIGURE 14.5. The timing of floods and the successful survival or colonization of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in five Holarctic regions. Open horizontal rectangles show the range of dates for emergence of fry from spawning redds; the closed horizontal rectangles indicate the central 80% of emergence times. Based on Fausch et al. (2001).

Flow and Access to Resources

Although flood events in higher gradient streams can have catastrophic impacts on aquatic and floodplain biota (see Chapter 6), in lowland rivers with fringing floodplains, increases in discharge can cue movement of fishes out of the stream channel and onto the inundated floodplain for purposes of feeding, reproduction, or for refuge from high mainchannel flows. The most extreme examples of such movement occur with tropical freshwater systems, such as the Amazon Basin; however, similar patterns occur, or occurred before levee construction and channelization, in many North American streams (Welcomme 1979; Ross and Baker 1983; Junk et al. 1989).

The importance of access to inundated floodplains by fishes has been recognized by biologists for over 100 years. Stephen Forbes, one of the first presidents of the Ecological Society of America and one of the founding fathers of North American ecology, clearly understood the great importance of floodplains, as is evident from an address given to the American Fisheries Society in 1910, stating, “Nothing can be more dangerous to the continued productiveness of these waters [the Illinois River] than a shutting of the river into its main channel and the drainage of the bottom-land lakes for agricultural purposes” (Schneider 2000). Forbes further emphasized the importance of natural access to fringing floodplains by fishes and other aquatic organisms in his classic paper, “The Lake as a Microcosm” (Forbes 1925). Sadly, in spite of the knowledge and long efforts of Forbes and his colleagues to influence law makers, some of the major habitats on the Illinois River floodplain, including those that had formed the nucleus of their research, were ultimately levied and drained for agricultural purposes (Schneider 2000).

The periodic inundations of forested bottomlands along many low-gradient streams provide fishes with direct access to terrestrial food resources. Beaverdam Creek, a tributary of Black Creek in the Pascagoula River drainage of southeastern Mississippi, provides an excellent example of connectivity between a low-order stream (second order at the study site) and its floodplain. The flow pattern can be highly flashy (see the figure in Box 14.1) and is driven by rainfall events. Periods of overbank flow are of short duration, typically 80 hours or less, and occur primarily in the winter and early spring (November–April), although there is considerable annual variation. Fishes move onto the inundated floodplain quickly even as the water is rising; species occurring in 60% or more of the floods were Striped Shiner (Luxilus chrysocephalus), Tadpole Madtom (Noturus gyrinus), Blackspotted Topminnow (Fundulus olivaceus), Longear Sunfish (Lepomis megalotis), and Pirate Perch (Aphredoderus sayanus) (Slack 1996). Another 14 species occurred in 20–60% of the floods, and 13 species rarely moved out of the stream channel, occurring in < 20% of all floods. However, of the 36 fish species documented from the study site (including both the stream channel and the floodplain), only four, Speckled Darter (Etheostoma stigmaeum), Southern Brook Lamprey (Ichthyomyzon gagei), Spotted Bass (Micropterus punctulatus), and Flagfin Shiner (Pteronotropis signipinnis), were never collected on the floodplain. Not surprisingly, the number of species on the floodplain increased as a function of flood duration, although species composition varied substantially among floods (i.e., species similarity was not related to flood duration). Because of the short duration of inundation and the generally low frequency of duration during the spawning periods for most of the species, fishes were not using the inundated floodplain for spawning but instead to take advantage of a pulse of terrestrial prey items (Slack 1996; S. T. Ross unpublished data). Also, given the short duration of flooding, “the occurrence of fishes on the floodplain represents opportunistic exploitation of additional habitat, and not floodplain habitat, per se” (Slack 1996).

The hypothesis that the floodplain of this low-order stream provides significant food resources was tested using enclosures in the stream channel and on the inundated floodplain, which were stocked with Cherryfin Shiner (Lythrurus roseipinnis), a shoaling, drift-feeding minnow (O’Connell 2003). Of course, enclosures could not be placed in the stream channel during periods of floodplain inundation because of water depth and current speed, so the comparison is between the low-flow stream and the high-flow, inundated floodplain. Overall, there were significantly more items in the drift on the inundated floodplain compared to the stream channel. Cherryfin Shiner, held at natural densities in floodplain enclosures, consumed more than twice the mass of prey compared to those in stream enclosures. Although the actual diversity of prey items did not differ between the two habitats for either availability or presence in fish gut contents, the taxonomic composition of the diet of floodplain fish differed significantly from those in the stream. Most of the difference was due to the high number of terrestrial arthropods, especially Springtails (Collembola) and terrestrial mites that were eaten by fish on the floodplain. The study showed that the inundated floodplain offered more food than the low-water stream, with the mean density of drift items never below eight per m3, whereas the mean densities of drift items in the low-water stream were never more than six per m3, and floodplain drift densities can be 2–3 times higher than the maximum drift density expected for the stream. Consequently, even for this low-order stream, periodic flooding allows fishes access to abundant prey sources, and because there were not differences in drift densities among sampling periods, the inundated floodplain can consistently provide high densities of drift (O’Connell 2003). These results are somewhat counter to predictions of the flood-pulse concept for small streams in that fishes are actively moving onto the inundated floodplain and feeding directly on available resources rather than using resources indirectly as they are washed into the stream channel.

Black Creek, a larger stream in the same Mississippi watershed (annual mean discharge of 6.8 m3s−1), has winter and spring overbank floods of longer duration (although stream discharge or stage were not continually monitored at the site) and the occurrence of fishes moving onto the floodplain, versus those that did not, was more distinct (Ross and Baker 1983). Species moving onto the floodplain, termed flood exploitative, were hypothesized to have increased reproductive success, as shown by population size, because of increased food availability prior to spawning. A second suite, termed flood quiescent, did not venture onto the floodplain and were hypothesized to decline following years with more flooding. A test of the hypothesis with Weed Shiner (Notropis texanus), a flood exploitative species, and Blackbanded Darter (Percina nigrofasciata), a flood quiescent species, showed that Weed Shiner abundance was significantly correlated with high-flow years. In contrast, Blackbanded Darter population size did not increase or decrease in relation to spring discharge prior to spawning (Ross and Baker 1983).

In progressively larger rivers, the importance of periodic inundation of floodplains changes to include spawning and nursery habitat in addition to increased food availability. The Tallahatchie River of Mississippi, a large tributary of the Yazoo River (a major tributary of the Mississippi River), has an average monthly discharge of 1,525 to over 3,600 m3s−1. The Yazoo River floodplain, dominated by agricultural land and associated second-growth hardwood and sparse cypress, is inundated during winter and spring. The floodplain also supports some permanent bodies of water. Based on light-trap sampling, more larval and juvenile fishes were collected in floodplain habitats than in the river channel. From early spring to midsummer, larvae of spring-spawning fishes were dominant in floodplain habitats, suggesting the importance of the floodplain, even though partially modified as agricultural land, as a spawning and nursery ground for riverine fishes (Turner et al. 1994). Numerically abundant taxa included Gizzard Shad (Dorosoma cepedianum), Crappie (Pomoxis spp.), and various darters (Percidae).

The upper Mississippi River watershed includes the states of Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota and, although a highly modified system, has floodplain habitats primarily associated with impounded sections. Fishes associated with littoral zone habitats in the impounded river sections, such as Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) and Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), showed increased growth responses following extreme flooding compared to lower-flow periods. Such results, albeit only shown by certain size classes, are consistent with predictions of the flood-pulse concept for large river-floodplain systems (Gutreuter et al. 1999). Black Crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus), which are less associated with the littoral zone, showed an ambiguous response to flooding, and the even more lotic species, White Bass (Morone chrysops), did not show an immediate growth response to flooding, again consistent with predictions of the flood-pulse concept (Junk et al. 1989; Gutreuter et al. 1999).

Although many North American freshwater fishes do show spawning, hatching, and growth patterns that are related to high river discharge and access to floodplain habitats, there are also species that do not respond to high flow in terms of growth (e.g., White Bass in the upper Mississippi River) or reproduction (e.g., Blackbanded Darter in Black Creek, Mississippi) (Ross and Baker 1983; Gutreuter et al. 1999). Consequently, flow regimes in rivers are not a “one size fits all” situation, especially when freshwater faunas are considered on a worldwide scale (King et al. 2003). Particularly in arid regions of the world where river flows are unpredictable, such as in parts of Australia, at least some groups of native fishes successfully recruit during summer low-flow conditions (King et al. 2003). This life-history pattern fits predictions of the low-flow recruitment hypothesis (LFR) (Humphries et al. 1999). In the low-gradient Brazos River, Texas, where over-bank flooding is highly irregular and unpredictable, oxbow lakes did support higher numbers of juvenile fishes relative to the main channel and were particularly important for equilibrium strategists such as Bluegill and White Crappie (Pomoxis annularis)—species that build nests and defend young. Small species with prolonged reproductive periods, such as Red Shiner (Cyprinella lutrensis), and large, long-lived species, such as Longnose Gar (Lepisosteus osseus), were abundant in the river channel. Fishes with a periodic strategy, such as gar, are able to retain their reproductive potential for long periods in the river channel until high flows allow access to oxbow lakes for spawning. In fact, Longnose Gar was the only species in the Brazos River study showing greater abundances in the wet year. In contrast, the low-flow, dry year favored Red Shiner, Western Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), and Gizzard Shad. Overall, hydrologic connectivity did not increase juvenile production for most species, suggesting that recruitment dynamics of these species were similar to predictions of the LFR (Zeug and Winemiller 2008b).

HYDROLOGIC CYCLES AND FISH ASSEMBLAGES

Altered Patterns

Perhaps one of the oldest of human impacts on aquatic systems is the building of dams (Baxter 1977). Dams have major impacts on riverine ecosystem function by changing downstream flow patterns and sediment supply, altering water temperature, and blocking the upstream and downstream movement of nutrients and organisms (see Chapter 5 and Figure 5.5). Most dams can be categorized into two major functional groups—those built to store water and those built to raise water levels. Storage dams generally have a large storage volume (e.g., some large western impoundments can retain almost four years of average annual runoff), a large hydraulic head, long retention times, and major control over the downstream release of water. Run-of-river dams are characterized by low storage volumes, short hydraulic residence times, a small hydraulic head, and little or no control over water releases. Although they do trap sediment, they tend not to alter downstream water temperatures (Poff and Hart 2002). In addition to blocking passage, specific impacts of dams depend on the type and purpose of the impoundment—storage dams built for flood control are usually emptied as soon as possible following a flood; storage dams built for other purposes retain water during high stream inflow and then gradually release water over time, or retain most water until additional reservoir capacity is needed for the next high flow (Baxter 1977).

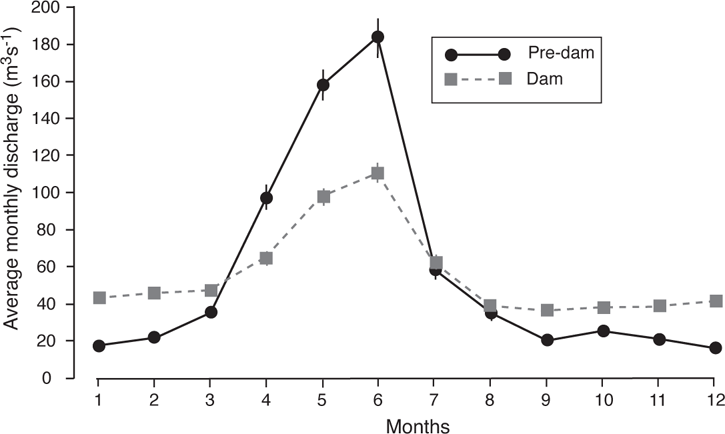

What is retained by the dam (water, sediment, nutrients, and heat) is typically lost to the stream. Typical impacts of large to medium-sized dams on flow patterns include creating a lag in peak flows and reducing the overall magnitude of flows, and either increasing low-flow discharge (in dams associated with hydropower generation or in response to downstream irrigation needs), or totally drying downstream channels (Baxter 1977; Mount 1995). For instance, Navajo Dam, which impounded the San Juan River in 1962, reduced the magnitude and duration of spring flows while increasing low-water discharge (Figure 14.6). However, generalizing on the specific hydrological impacts of dams, especially dams on smaller watersheds, is challenging because variation caused by dam operations are superimposed on the already great variation in flow patterns caused by geographical and climatic regions, land use patterns, and position in the stream network (Poff et al. 2006).

In a broad-based study of the effects of dams on small watersheds (< 282 km2) within the United States, dams reduced peak flows while elevating low flows, similar to effects of large dams. Dams on small watersheds also caused increases in flow duration, except for those in the southeastern United States, which did not show any differences from pre-dam conditions. Finally, small dams, as with large dams, tended to reduce flow variability, with the exception of hydropower dams whose flow characteristics are often driven by distant electrical demands (Poff et al. 2006).

In addition to altering flow and associated sediment dynamics, dams can also have a major impact on water temperatures at certain times of the year, especially summer and fall. Dams, and especially those with discharges originating below the thermocline (hypolimnial discharge), gain heat in the epilimnion during the summer as solar radiation on the impounded water is converted to thermal energy. Because this has little effect on the cold hypolimnion, hypolimnial discharges are colder compared to pre-dam conditions. When reservoir stratification breaks down in late fall and winter, some of the stored heat can enter a hypolimnial outflow, warming downstream water relative to pre-dam conditions (Baxter 1977). In a detailed study of the effects of four dams in the Pacific Northwest, summer water releases were cooler compared to temperatures before the dams were built, and generally were warmer in the fall and winter. However, even though two of the dams released water from the hypolimnion, one released water from the epilimnion, and one released water from various levels, all four had similar effects on water temperatures. Two dams were located in the Willamette River drainage, Oregon, one on the Cowlitz River in Washington and one on the Rogue River in southern Oregon (Angilletta et al. 2008).

FIGURE 14.6. The effects of dams on river hydrology, based on discharge of the San Juan River downstream of the Navajo Dam. Data are means and 95% confidence intervals of monthly flows during pre-dam (1942–1961) and dam conditions (1962–1991). Discharge data are from the USGS Gauge 09368000 in Shiprock, New Mexico.

Chinook Salmon used all four of the dammed streams studied by Angilletta et al., and numerous aspects of salmon biology are keyed to temperature (Brett 1971). Spawning of Pacific salmon species, the emergence of fry, and the migration of smolts all are related to appropriate thermal cues in natal lakes and streams (Brett 1971; Angilletta et al. 2008). For instance, downstream migration of Chinook Salmon smolts begins at water temperatures above 10° C and reaches a maximum between 12.5 and 15° C; higher average spring temperatures result in earlier emigration (Roper and Scarnecchia 1999). Because dams maintain higher stream temperatures into fall and winter, they should impact late spawners more than early spawners. Consequently, there is a very real possibility that dams and other anthropogenic changes can result in mismatches between life histories and environmental conditions or increased mortality because of temperature stress. Elevated water temperatures increase the rate of embryonic development and thus accelerate the timing of emergence of alevin from the redd. The early emergence can potentially expose young fish to peak flows, higher predation rates, or lowered resource abundance (Angilletta et al. 2008).

One of the more obvious effects of dams is that of blocked passage caused by large dams as well as by numerous smaller obstacles such as low dams and culverts. In the Columbia River basin, the largest river basin in the Pacific Northwest, large, impassable dams are responsible for the loss of one-third of the historical Pacific salmon and Steelhead habitats, including 87% of mainstem Columbia River spawning habitat for Chinook Salmon (Sheer and Steel 2006). In addition, almost one-half of the historical populations of Sockeye Salmon are extinct (Waples et al. 2011).

There is no doubt that large dams have had profound impacts on aquatic systems in the Columbia River basin, in particular on migratory fishes. However, quite often the declines in migratory species are due to multiple causes rather than a single factor. An excellent example of this point is the case of the Snake River-Redfish Lake population of anadromous Sockeye Salmon. The Salmon River, named for the abundance of Pacific salmon it used to support, and Redfish Lake, named for the large numbers of Sockeye Salmon that formerly spawned in the lake tributaries (redfish is a local name for anadromous Sockeye Salmon), historically supported large numbers of Sockeye Salmon that were a significant component of the overall Columbia River salmon production (Bjornn et al. 1968). Redfish Lake, and other nearby lakes in the Sawtooth Valley, Idaho, represent the farthest upstream spawning sites known for Sockeye Salmon—the distance from Redfish Lake to the mouth of the Columbia River is some 1400 km and represents an elevation gain of almost 2000 m. Fish reach Redfish Lake from the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia, Snake, and Salmon rivers, with a final ascent up Redfish Lake Creek (Figure 14.7). Spawning of Chinook Salmon, anadromous Sockeye Salmon, and Kokanee (nonmigratory form of O. nerka) in these lakes was documented by fisheries scientists from 1894 to 1896 (Evermann and Meek 1898). However, the complex genetic structure of O. nerka populations in Redfish Lake has only been understood much more recently. Both resident (Kokanee) and anadromous Sockeye Salmon in Redfish Lake are more similar to each other than to Sockeye Salmon populations in the upper Columbia River, and Kokanee from Redfish Lake and other lakes in the Sawtooth Valley are genetically distinct from other Columbia River populations. Furthermore, Redfish Lake populations of Kokanee and anadromous Sockeye Salmon are also distinct, but with an additional level of complexity. There are two quite distinct gene pools of O. nerka in Redfish Lake, one being the resident Kokanee and the other comprising the anadromous Sockeye Salmon plus a generally nonmigratory or “residual” form that matures at a smaller body size than the anadromous form (Waples et al. 2011). Given the amazingly long migration route of the Snake River-Redfish Lake anadromous Sockeye Salmon, perhaps the “residual” form represents a type of “bet-hedging” to survive times when migration is less successful or unsuccessful, much as variation in age at maturity does for populations of Chinook Salmon (Waples et al. 2010).

The natural harvest of Columbia River salmon has occurred for around 10,000 years, although population-altering levels of fishing pressure did not occur until large-scale commercial harvests began in the 1860s, resulting in obvious declines in all salmon species. Even though extensive declines of Pacific salmon were occurring before the added impact of blocked river passage by dams, declines of the Snake River salmon were accentuated by the construction in 1913 of the Sunbeam Dam, located on the main channel of the Salmon River about 32 km downstream from the mouth of Redfish Lake Creek (Figure 14.7). The dam was essentially a complete barrier to fish passage until it was partially removed in 1934, although recent genetic evidence indicates that the original anadromous plus “residual” Sockeye Salmon population was not extirpated (Bjornn et al. 1968; Waples et al. 2011). The 1930s also saw the start of major development of downstream hydroelectric dams and the continued addition of main-channel dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers into the 1970s (Selbie et al. 2007; Waples et al. 2007). At present, only about 5% of the historical spawning habitat for Sockeye Salmon remains accessible in the Columbia River basin and the number of Snake River Sockeye Salmon returning to lakes in central Idaho has dropped by over 99% (Selbie et al. 2007). The Snake River Sockeye Salmon was listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 1991 and there are major efforts to restore the stock, although it still remains near the brink of extinction (Selbie et al. 2007; Keefer et al. 2008a).

FIGURE 14.7. Major rivers and associated dams in the Columbia River basin that are referred to in the text. Light gray shading indicates upstream reaches blocked to migratory salmonids by impassable dams. Based on Bjornn et al. (1968), Selbie et al. (2007), and Waples et al. (2007, 2011).

Overfishing and blocked passage are not the only factors involved in the decline of Snake River Sockeye Salmon. There have also been major changes in the ecology of its natal streams and lakes, particularly Redfish Lake. Fish introductions were common in Redfish Lake beginning in 1921. Even though the lake supported an apparently native population of Kokanee Salmon, juvenile Kokanee were introduced from multiple sources, as well as Rainbow Trout and millions of Sockeye Salmon eggs, again from unknown sources in the United States and Canada. Overall, the introductions increased predation pressure on zooplankton because Kokanee Salmon remained planktivorous and remained in the lake throughout their life cycle. Consequently, juvenile anadromous Sockeye Salmon were competing directly for zooplankton resources with juvenile and adult Kokanee. The change in predation pressure resulted in the loss of large zooplankton (i.e., Daphnia), which were replaced by smaller, less nutritious forms (see also Chapter 13). In addition, nutrient enrichment began in the 1950s, perhaps due to enhanced atmospheric nitrogen deposition as well as purposeful fertilization with the goal of enhancing the forage base for Sockeye Salmon, but with the unintended consequences of further altering the phytoplankton and zooplankton composition of the lake (Selbie et al. 2007). The Snake River Sockeye Salmon are also the most southerly of all Sockeye Salmon populations, and the currently high mortality of migrating fish is due in part to water temperatures near their upper tolerance levels (21–24° C) (Keefer et al. 2008a).

Fishes with complex life-history patterns, such as migratory fishes traversing a variety of habitats, can have a life-history pattern that is no longer optimal or even possible given current environmental conditions (see Chapter 9). The overall low productivity of the rearing system, the extraordinary migration demands on juvenile and adult fish even under natural conditions, their current problems with blocked passage, their sensitivity to regional climate warming, and currently high parasite loads, all suggest that Snake River Sockeye Salmon may be naturally vulnerable to the novel environmental stresses of twentieth century (Selbie et al. 2007; Keefer et al. 2008a).

Smaller dams and diversions have also contributed to declines of Pacific salmon in the Columbia River basin. The Willamette and Lower Columbia river basins include all Columbia River tributaries downstream of the Dalles Dam, located 308 river km inland from the river mouth (Figure 14.7). Within this region there are at least 1,491 anthropogenic barriers to fish passage resulting in the blocked access to 14,931 km of streams (a 42% loss). This includes a loss of 10,142 km of prime Steelhead habitat, based on river gradient, and an 8,380 km loss of prime Chinook Salmon habitat. Habitat loss disproportionately includes high-quality streams characterized by intact coniferous forests that provide greater shading, more woody debris, and cooler water temperatures. It is not surprising that the loss of large amounts of habitat is significantly correlated with the decline in salmon populations (Sheer and Steel 2006).

As is obvious from the Columbia River, in many instances a single river has been impacted by multiple dams—the Colorado River has 12 major reservoirs for purposes of water supply, flood control, and hydropower, and the upper Mississippi River, between Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Cairo, Illinois, has 27 low-head navigation dams (Christensen et al. 2004; Zigler et al. 2004). Effects of high dams on the Colorado River, including blocked fish passage and altered flow and sediment regimes, are related to the severe population declines of Colorado Pikeminnow, Humpback Chub (Gila cypha), Bonytail Chub (G. elegans), and Razorback Sucker, all of which have evolved long-distance migration patterns as part of their life histories (Minckley et al. 2003). Low-head navigation dams on the upper Mississippi River can act as semipermeable barriers to fish movement. Paddlefish (Polyodon spathula) have evolved long-distance migrations for access to prime growth areas, such as oxbow lakes, which differ from suitable spawning areas generally characterized by clean gravel substrata in flowing water (Purkett 1963; Jennings and Zigler 2009). Based on a radio-tagging study, Paddlefish populations in the upper Mississippi River are generally fragmented in an upstream direction. Because gates of navigation dams are raised off the bottom as river flow increases, the best opportunity for upstream passage is during high flows when the gates are raised out of the water resulting in open river conditions. Overall, upstream passage is more affected than downstream passage (Zigler et al. 2004).

The Fox River, a sixth-order tributary of the Illinois River draining parts of Wisconsin and Illinois, has a 171 km reach that is fragmented by 15 low-head dams. The dams are all run-of-river structures that are less than 15 m high, with surface spillways and small, shallow impoundments (Santucci et al. 2005). The distributions of at least 30 fish species are affected by the dams, either by having upstream movements blocked or reduced or by having fragmented populations. For instance, the 15 species limited in their upstream distributions by dams dropped out sequentially in an upstream progression, with only five passing the first dam in the series and only four passing the second. Two species, Gizzard Shad and River Redhorse (Moxostoma carinatum), made it past the third, fourth, and fifth dams, and River Redhorse passed the sixth dam in the series before being blocked by the seventh. The 15 species with truncated distributions occurred in the upper and lower river, but usually not in the more central, urbanized area that also had a high density of dams (eight dams in 22 river km) compared to other parts of the river (dams every 15.3 km). Limiting factors likely included low water quality in the impoundments as well as effects of barriers; for instance, species richness, abundance, and measures of biotic integrity were all reduced in impoundments versus the free-flowing sections of the river. Overall, the study shows the strong impact that even low-head dams have on fishes and other aquatic organisms.

In eastern North America, including the southeastern United States but especially in the northeastern United States, mill ponds and other low-head dams are or were common and appeared in large numbers beginning in the seventeenth century and extending into the early twentieth century (Walter and Merritts 2008). Mill ponds essentially replaced Beaver ponds, except that they represented much more of a barrier to fishes. In these regions, most small to medium streams (first–third order) were impacted, often by multiple dam sites. Milldams (usually 2.5–3.7 m high) were the primary power source for industry, especially in the nineteenth century, and as early as 1840 there were more than 65,000 water-powered mills in the eastern United States. Not surprisingly, impacts on fish populations were noticed early on. For instance, a milldam on the Conestoga River, Pennsylvania, was torn down in 1731 because it was damaging the local fishing industry, and a 1763 petition concerning the same river cited milldams as responsible for destroying shad, salmon, rockfish (Striped Bass), and trout fisheries (Walter and Merritts 2008).

Although many milldams are now breached (a much reduced zone of impoundment and with spillway open or with other damage to dam) or relict (free-flowing; evidence of dam often reduced to bank-side structures), intact and even breached dams continue to have impacts on fish assemblages. Currently there are more than 10,000 low-head dams, including milldams, in Alabama. In a study of 20 streams, nine having intact dams, six with breached dams, and five with relict dams, fish species richness in the flowing stream above the impoundment was lower in streams with intact or breached dams compared to assemblages immediately downstream of the dams. Overall, the fish fauna comprised 88 species in 12 families, with minnows (55%), darters (20%) and sunfishes (14%) being the most abundant groups. Recovery of fish assemblages, once effects of the barrier were largely removed (relict dams), was evidenced by no differences between upstream and downstream reaches (Helms et al. 2011).

In species-rich, small upland streams of the southeastern United States, movements of fishes are associated with feeding, reproduction, and recolonization of areas that might be periodically dewatered and are important for maintenance of viable populations (Chapter 5). In these small streams with rich faunas of relatively small-bodied fishes, barriers to movement need not be large dams or even low-head dams such as mill ponds. For instance, road crossings on national forest streams can act as potential barriers to fish movement. In a study in the Ouachita National Forest, Arkansas, on small tributaries of the Ouachita River, the potential of road crossings as barriers to fish movement was studied on nine crossings on seven streams (Warren and Pardew 1998). Four types of crossings, fords, open-box, culvert, and slab, were compared in terms of fish passage to natural reaches. Ford crossings were submerged roadbeds with a compacted gravel substratum; open-box crossings had 1–3 bays, each 3–4 m wide and 24–30 m long, topped with a concrete roadbed and with a concrete or gravel substratum; culvert crossings were two to four 1 m–diameter pipes placed on a concrete pad and covered by a concrete or earth/gravel roadbed and with a concrete apron extending downstream for 3–4 m; concrete slab crossings were low dams with a 25 cm vertical drop off the downstream edge to the pool below (Warren and Pardew 1998).

Both culvert and slab crossings reduced fish movement overall, and had a lower diversity of fishes moving through them compared to natural reaches. Current velocity through the crossing was closely related to the degree a crossing acted as a barrier—culverts had the highest water velocity and the lowest passage, whereas open box crossings had the lowest velocities and the highest level of fish passage. A key point from this study is that it doesn’t require a dam tens of meters tall to act as a barrier to small fishes—relative size matters. Small-stream fishes need to have water velocities through crossings that are much lower than maximum velocities suggested for migratory fishes such as salmonids (Warren and Pardew 1998).

DAM REMOVAL, FISH PASSAGES, ENVIRONMENTAL FLOWS, AND OTHER REMEDIAL APPROACHES

Given the previously mentioned examples and the various ways in which the behavior and life cycles of fishes and other aquatic organisms are closely tied to patterns of flow and water temperature, it stands to reason that even apparently minor changes in these characteristics can have wide-ranging impacts (Poff et al. 1997). As shown previously, fishes whose movements are strongly related to flow events may be more vulnerable to extirpation when faced with reduced flow patterns or be blocked from movement by dams, including small structures (Albanese et al. 2004). Successful spawning of native fishes can be reduced if high reservoir releases coincide with larval emergence, or nonindigenous fishes can be favored if release patterns favor their survival (Harvey 1987; Fausch et al. 2001). Based on currently available knowledge, protecting or restoring natural flow regimes is one of the most prudent approaches for promoting the colonization and persistence of fish populations (Bain et al. 1988; Poff et al. 1997, 2003; Baron et al. 2002; Albanese et al. 2004; Poff and Zimmerman 2010).

Regaining Natural Flow Characteristics

Historically, management of riverine ecosystems, including efforts of water allocation to sustain ecosystems and meet human demands, has not favored environmental flow protection. This is particularly true for the protection of high-discharge events that are necessary for ecological purposes such as channel maintenance and the maintenance and creation of floodplain habitats (Poff et al. 2003; Richter 2010). In addition, even where environmental flow protection that mimics natural flow variability has been agreed upon, the actual implementation has proven difficult for a variety of reasons, including natural changes (i.e., droughts and floods), political will, other societal demands, and hydrological engineering (Poff et al. 2003; Richter 2010).

Although seeming to make good ecological sense, ecological impacts of environmental flows from dams, achieved through modifying dam operation or dam structure, are rarely evaluated (Souchon et al. 2008; Bradford et al. 2011). One of the few long-term studies focused on the Bridge River, a tributary of the Fraser River in British Columbia, which was dammed in 1960 for hydropower production (see also Chapter 6). The dam is located 41 km upstream from the confluence with the Fraser River. Because flow was diverted into another watershed, a 3 km stretch of the river immediately below the dam was dewatered. Below this reach, five small tributaries and groundwater provide low but continuous stream flow, although the inflow from tributaries is < 1% of the preimpoundment flow. The Bridge River receives an unregulated tributary 15 km downstream from the dam (Bradford et al. 2011). Consequently, there were three different dam-altered habitats downstream from the dam: 3 km of dry channel, 12 km of consistent but greatly reduced flow, and 30 km of flow augmented by an unregulated tributary, albeit still with flows much less than during pre-dam conditions (Bradford et al. 2011).

A 13-year experiment of flow releases from the Bridge River dam was designed to test the efficacy of environmental flows to increase salmonid production (primarily Rainbow Trout; Coho Salmon, O. kisutch; and Chinook Salmon). The environmental flow has been equivalent to a mean annual discharge of 3 m3s−1 and is varied seasonally to provide a summertime peak and improved winter flow. Even though the environmental flow is < 1% of the pre-dam flow (approximately 100 m3s−1), greater flows were not possible given hydropower demands and because much of the prime salmonid habitat was located in the now-impounded area above the dam—the first section of the river below the dam was likely most important for fish passage to those upstream habitats. The monetary cost of providing the environmental flow, in terms of lost hydropower revenue, is approximately $5–8 million Canadian dollars (Bradford et al. 2011).

The total number of juvenile salmonids did increase significantly following implementation of the environmental flow, with most of the increase as a result of repopulation of the formerly dry 3 km section immediately below the dam. In the next two reaches of river that were already flowing, although at much reduced levels prior to the environmental release, there was not a detectable change in total salmonid abundance. Consequently, the overarching hypothesis that fish production in all three sections would increase as a consequence of increased discharge (or more water equals more fish) was not supported by the results outside of the section that was dry before managed flows resumed (Bradford et al. 2011). Importantly, another lesson from the Bridge River study is that impacts of environmental flows are extremely context dependent—the outcomes being driven by the amount and quality of downstream habitats. Although the restored flow only averaged 3 m3s−1, it was managed to reflect the snowmelt-driven flow pattern of the natural river. One result of this was the restoration of a narrow riparian zone that included young cottonwood trees (Hall et al. 2009). In fact, because it is often not possible to regain the magnitude of natural flows present prior to dam construction, the concept of river downsizing becomes an important alternative. By creating flows that follow a natural progression, even though much less in magnitude, much of the natural function of at least some rivers can be restored (Trush et al. 2000).

As with the Bridge River system, managed flows are often designed for particular species, especially in the northwestern United States and western Canada, where species diversity is low and a major emphasis is on the recovery of migratory salmonids. The Skagit River, in northwestern Washington, includes prime spawning and rearing habitat for anadromous salmonids. However, the survival of eggs and fry was compromised by operation of the Skagit hydroelectric project, which was initiated in the early 1900s with additional dams added into the 1960s and which supplies electricity to Seattle. As with other hydroelectric facilities, discharge varied with power demands and created significant problems of egg and fry mortality, especially for Pink (O. gorbuscha), Chum (O. keta), and Chinook salmon (Graybill et al. 1978). Beginning in 1991, discharges from the Skagit project were changed to improve habitat quality for the three salmon species by reducing mean and maximum flows during the period of snowmelt and increasing minimum and mean flows during the fall and winter. Rate changes were also modified because the rapid declines in flow (downramping) during the day had caused considerable stranding mortality of fry. Under the managed flows, downramping was reduced and daytime downramping nearly eliminated. Overall compliance with the flow recommendations has been 99% (Connor and Pflug 2004).

Studies during the period of managed released (1991–2001) compared to preagreement conditions show that the environmental flow measures resulted in substantially increased Pink and Chum salmon abundances and in a sustainable healthy population of Chinook Salmon in the upper Skagit River. The study area now supports the greatest percentage of spawning adults of the three salmon species in the Skagit River basin, and the Skagit River basin has the largest runs of Pink and Chum salmon in the contiguous United States (Connor and Pflug 2004).

Determining appropriate releases from dams can be more challenging in species-rich eastern and southeastern U.S. streams, especially when the magnitude of a pre-dam hydrograph cannot be attained. As with the Bridge River study, substantial benefits can sometimes be obtained by changing releases to guarantee a small minimum flow (fish really do need water). Thurlow Dam, a hydroelectric facility, was constructed on the Tallapoosa River, Alabama, in 1930. Water was released from the dam based on power demands—averaging 230 m3s−1 when generating electricity or no release when there was no power generation. Not surprisingly, fishes were affected by the rapidly pulsating release pattern, with those typified as fluvial specialists absent or rare in the sampling area below the dam but gradually recovering in abundance farther downstream where other tributaries resulted in a more normal hydrograph (Kinsolving and Bain 1993).

Starting in February 1991, a minimum flow of at least 34 m3s−1 was established as part of a relicensing agreement, although the high flows still occurred during power generation—so the overall change was from a highly pulsating flow regime that dropped to zero discharge between the peaks, to a highly pulsating flow regime that maintained a continuous base flow. Before the establishment of a base flow, the shoreline fish abundance and diversity 3 km below the dam was low and dominated by generalist species, such as Emerald Shiner (Notropis atherinoides), Weed Shiner, Blacktail Shiner (Cyprinella venusta), Redbreast Sunfish (Lepomis auritus), Longear Sunfish, Redear Sunfish (L. microlophus), Spotted Bass, and Largemouth Bass (Travnichek et al. 1995). Approximately one year after the initiation of a minimum low flow, species richness more than doubled to 19 and included a majority of fluvial specialists, such as Speckled Chub (Macrhybopsis sp. cf. M. aestivalis), Fluvial Shiner (N. edwardraneyi), Skygazer Shiner (N. uranoscopus), Bronze Darter (Percina palmaris), Speckled Darter, and Banded Sculpin (Cottus carolinae).

Reduced stream discharge, as a consequence of impoundments, is one of the major factors in breaking the connection between fringing floodplains and the river (Poff et al. 2010). The other is the construction of levees to block a river from access to its historic floodplains, generally for the development of agriculture on the rich floodplain soils. Levees, however, also isolate a river from its natural reservoir (its floodplain) so that the intensity of otherwise smaller floods is increased (Belt 1975). For instance, although the annual discharge of the Mississippi River at Vicksburg has not changed appreciably in 170 years, the Mississippi River and its major tributaries now have extensive development of lateral levees, with continuous levees along both banks south of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the channel of the Mississippi River has lost about one-third of its volume since 1873 (Belt 1975; Turner and Rabalais 2003).

Reconnecting Floodplains and Streams

Because of the known importance of floodplain habitats as spawning and/or nursery areas for many native fish species, the restoration or creation of floodplains is often a major goal of recovery efforts (Poff et al. 2010). Such restoration requires hydrological connectivity between the floodplain and river, a flow regime that has sufficient variability, and a magnitude of scale that is adequate for biological processes to occur and for the restoration to have meaningful ecological benefits. In addition, floods need to occur for sufficient duration and season to coincide with life-history patterns of floodplain associated organisms (Opperman et al. 2010). The Sacramento-San Joaquin river system in California’s Central Valley has undergone extensive modification from its natural state through dam building, water extraction, channelization, bank armoring, channel incision, and levee construction, all of which have resulted in major negative impacts on the aquatic and riparian biota (Opperman et al. 2010). Two case studies show the importance of floodplain restoration at differing scales—one affecting 0.4 km2 and providing benefits at a local level (Cosumnes River), and the other affecting 240 km2 and providing benefits at the population level (Yolo Bypass).

The Cosumnes River is unique among streams in the region in that it lacks mainstream dams and still has a fairly normal hydrograph. However, it does have levees along most of the lower reaches, denying juvenile Chinook Salmon and other fishes access to fringing floodplains (Moyle et al. 2007). The Nature Conservancy (TNC) acquired land along the lower Cosumnes River in 1984 and began restoring native vegetation. In 1985, a levee broke around an agricultural field, and although soon repaired, the freshly deposited sediment on the field soon was colonized by native cottonwoods and willows. When the farm property was acquired by TNC in 1987, the success of the accidental breach in fostering rapid growth of riparian vegetation led to the ultimate intentional breeching of levees starting in 1995 (Swenson et al. 2003).

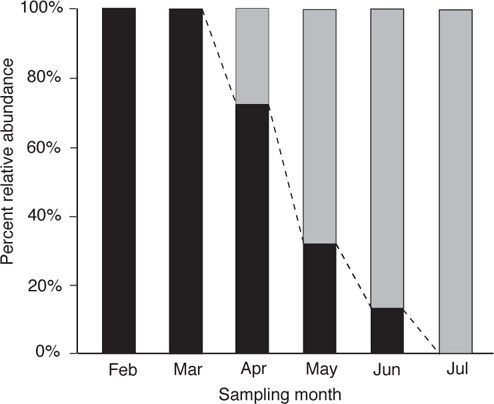

A study of larval fishes showed that the inundated floodplain was used early in the season by native fishes such as Splittail, Sacramento Blackfish (Orthodon microlepis), and Chinook Salmon, as a feeding, spawning, and rearing area and also by the nonindigenous Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) as a spawning and rearing area. By summer, only nonindigenous fishes, especially Mississippi Silverside (Menidia audens), Mosquitofishes (Gambusia spp.), and centrarchids were present (Crain et al. 2004; Moyle et al. 2007). Studies of floodplain use by native and nonindigenous fishes show that management of flows can favor native fishes by having extensive, early season flooding, followed by complete dewatering of the floodplain by the end of the flooding season (Figure 14.8) (Moyle et al. 2007).

The restored floodplain is also important for growth and retention of juvenile Chinook Salmon. Based on a series of replicated channel and floodplain enclosures stocked with young Chinook Salmon, the off-channel floodplain habitats provided a significantly better rearing habitat because of higher temperatures and productivity compared to the river (Jeffres et al. 2008). Interestingly, the increases of native fish retention and growth have been achieved while still retaining almost 90% of the preserve in active agricultural production, including grazing, rice farming, and other annual crops (Swenson et al. 2003).

The Yolo Bypass is a large, constructed wetland on the lower Sacramento River that has been in continuous use since the 1930s. Although originally engineered strictly to let floodwater from the Sacramento Valley overflow onto a broad floodplain, it is also important as wildlife and fish habitat. Among fishes, it is particularly important as a nursery area for Chinook Salmon and as a spawning, nursery, and feeding area for Splittail (Sommer et al. 2001). Splittail are endemic to the upper San Francisco estuary and its lower watershed, and have annual spawning migrations from the brackish estuary to upstream floodplains and tributaries. Larval and juvenile Splittail remain in floodplain habitats, until the high spring flows recede and the floodplain begins to dry, before moving back into the estuary. Splittail show increased growth and spawning success in wet years that are significantly related to the magnitude and duration of inundation of the constructed floodplain during their spawning and juvenile rearing periods. Winter flood pulses are also important to initiate upstream spawning migrations and to attract fish onto the floodplain (Feyrer et al. 2006).

FIGURE 14.8. The progression of numerically dominant native and nonindigenous fishes from the onset of floodplain access to the end of the flooding season in the restored floodplain of the Cosumnes River, California. Black bars indicate native species; gray bars show nonindigenous species; the dashed line shows the division between native and nonindigenous species. Based on Moyle et al. (2007).

Restoring Connectivity of Watersheds

One of the most obvious impacts of dams is the break in connectivity of aquatic ecosystems, and especially the loss of upstream habitat to migratory fishes. In fact, the need to maintain connectivity by using fish passages was recognized as early as the twelfth century during the reign of King Richard I in England with a statute instructing that “English rivers be kept free of obstructions so that a well-fed three-year-old pig could stand sideways in the stream without touching either side,” which was referred to as the King’s gap (Montgomery 2003). Although fish passages have a long history of use, studies of the efficiency of different types of passages for various species of fishes have only recently become common. In a broad review of research assessing the success of fish passages for the years 1965 to 2008, including 50 North American studies, three-fourths of the studies were published from 1999 to 2008. Although North American studies more often included postpassage effects compared to studies in other countries, the number of such studies was still only 11. Postpassage studies often showed serious negative impacts on fishes that successfully traversed a fish ladder, including delayed mortality or failure to reach spawning sites (Roscoe and Hinch 2010). Because of downstream effects of dams, and issues of upstream and downstream passage of fishes and other organisms, dams have contributed to significant declines in anadromous salmon, as well as other migratory species, throughout North America (Cooke et al. 2005; Roscoe et al. 2010).

Passages around low-head dams can be achieved by a relatively natural flow of water around the structure (termed nature-like passages). These passages typically have low gradients and mimic natural side channels. In contrast, fish ladders around large dams are highly engineered structures—generally a step-like series of compartments containing downstream-flowing water, requiring a fish to swim against the current and then jump to the next compartment (Volpato et al. 2009; Roscoe and Hinch 2010). The success of fish ladders is varied, especially when success is measured by the passage of multiple species of fishes rather than a single target group, such as anadromous salmonids.

Most of the attention on fish passage problems has been on economically valuable species, such as migratory shad or salmonids. However, other important components of native fish assemblages are also migratory (see Chapter 5). For instance, many catostomids show upstream spawning migrations, and the removal of migration barriers, either by the construction of fish passages or by actual physical removal. would benefit numerous species of North American catostomids (Cooke et al. 2005). As a case in point, a weir approximately 1 m high was constructed in 1971 to divert water to a power generating station, but which blocked upstream passage of fishes in the San Juan River, near Farmington, New Mexico, except during high flows. Construction of a nature-like fish passage in 2003 around the weir has successfully provided upstream access for native suckers, including the endangered Razorback Sucker, as well as Flannelmouth and Bluehead suckers. The passage has also been used by the endangered Colorado Pikeminnow. Because a grate holds the fish in an enclosure after they ascend the passage, nonindigenous fishes, such as Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and Common Carp, can be removed from the system. In 2010, 28,292 native fishes moved through the passage and 785 nonindigenous fishes were removed from the system (Figure 14.9) (Morel 2011; J. Morel, pers. comm., 2012).

Landsburg Dam, on the Cedar River, near Seattle, Washington, provides water to Seattle but had blocked fish passage for 103 years. In 2003, the installation of a fish passage facility allowed migratory and resident fishes the opportunity to regain access to upstream habitats. Once the fish passage became operational, the recolonization above the dam by adult salmonids, including Chinook Salmon, Steelhead, and Coho Salmon, was rapid and shows that the barrier bypass was successful in allowing migratory species to reestablish populations, leading to range expansion and potentially increasing population sizes (Kiffney et al. 2009).

Bonneville Dam, on the lower Columbia River (Figure 14.7), has the most complex passage facilities of the Columbia River dams, with two powerhouses, a spillway, and four lower-gradient passages that service two fish ladders (Keefer et al. 2008b). Based on radio-tagged adult fishes, passage efficiencies ranged from 92.1% for fall Chinook Salmon, 98.5% for spring-summer Chinook Salmon, 97.7% for Steelhead, and 98.8% for Sockeye salmon. Long passage times can be a source of stress to migrating salmonids. Median passage times were shortest for Sockeye Salmon (15 h), intermediate for Steelhead (17–24 h), and longest for spring-summer Chinook salmon (19–41 h). Overall, passage times were fairly similar for other large dams on the Columbia River (Keefer et al. 2008b).

FIGURE 14.9. The nature-like passage stream around a weir on the San Juan River near Farmington, New Mexico. Photo courtesy of James Morel.

In the Seton River, a tributary of the Fraser River of southwest British Columbia, after traveling 320 km from the mouth of the Fraser River, Sockeye Salmon must get around a 7.2 m diversion dam via a fish ladder to travel the final 55 or so km to their spawning grounds. The fish ladder is 107 m long, with 32 pools and a grade of 6.9%. Eighty-seven fish that had successfully ascended the fish ladder were radio-tagged and, using blood samples, assayed for indications of stress before being released either above the fish passage (28 fish) or below the dam (59 fish). Of those released downstream of the dam, 85% successfully returned to the tailrace below the dam, 44 entered the fish way, and 41 successfully ascended the fish ladder for the second time, for an overall success rate of 80% once fish entered the tailrace area. Postpassage mortality differed significantly between the fish initially released above the fish ladder and those forced to ascend the ladder a second time. Survival to the spawning grounds was only 73% for the second climbers and 93% for the fish that only ascended the fish ladder once. Although there could be positive (the test fish had found the fish ladder once already) and negative (some of the fish had to climb the fish ladder a second time, although physiological studies showed little indication of stress or exhaustion) biases by using fish that had successfully found and ascended the fish ladder, the important points from the study are that success in finding the fish ladder is no more than 85% and perhaps even less, and second, that some level of postpassage mortality likely occurs (Roscoe et al. 2010).