CHAPTER 23

Infectious Diseases

Introduction

We are surrounded by a microscopic world filled with potentially infectious organisms. They live on our countertops, in our soil, and on our skin. Most microbes in the natural environment do not cause illness. Microbes that are capable of producing human disease are known as pathogens. Despite our constant contact with microbes, we are usually able to stay healthy and avoid illness, thanks to our body’s disease-fighting capabilities. We have physical barriers like our unbroken skin, and we have sophisticated immunity cells. When patients are taken to the operating room, these defenses can be challenged, making patients prone to illness. As an anesthesia technician, you should understand pathogens and their associated diseases in order to play your part in preventing and treating infections.

The goal of this chapter is to:

- Identify various pathogens and their classification

- Describe common health care–associated infections

- Describe methods and precautions aimed at preventing infections

- Discuss options to help prevent infection after an infectious exposure has occurred

Pathogens

Pathogens can be classified as bacteria, fungi, parasites, viruses, and prions. Bacteria, fungi, and parasites are cellular. Viruses and prions are acellular but are infectious.

Bacteria

Bacteria are prokaryotes: one-celled organisms without nuclear membranes or membrane-bound organelles (Fig. 23.1). When these organisms begin to reproduce in sterile areas or produce toxins, they can lead to human disease. Bacteria are subdivided as either gram-positive or gram-negative organisms based on their appearance when stained in a microbiology laboratory. Gram-positive cell walls are made of a thick peptidoglycan layer, while gram-negative cell walls are made of a thin peptidoglycan layer surrounded by an outer membrane. Bacteria are also frequently classified by their shape: round (cocci) or thin bars (bacilli). The formations they take also vary; some cluster together, while others remain in chains. Bacteria can be distinguished by their need for oxygen for survival (obligate aerobes) or their ability to thrive without it (anaerobes).

FIGURE 23.1. Artist’s drawing of an example of a one-cell bacteria, in this case “gram-positive” cocci.

The above characteristics do not only help identify bacteria under the microscope, they can also help direct antibiotic therapy. For example, ceftriaxone may be a more effective antibiotic against gram-negative bacteria than cefazolin; metronidazole might be chosen in a clinical infection where anaerobic bacteria are suspected.

Once a person is infected, the type of disease manifested depends on the type of bacteria, the site of infection, and the susceptibility of the host. Invasive infections can include pneumonia, meningitis, cellulitis, abscesses, urinary infections, ear infections, and many more. Many bacterial infections are contracted “in the community” (i.e., outside the hospital); however, some can be acquired in a health care setting, as we will discuss later in the chapter.

Fungi and Parasites

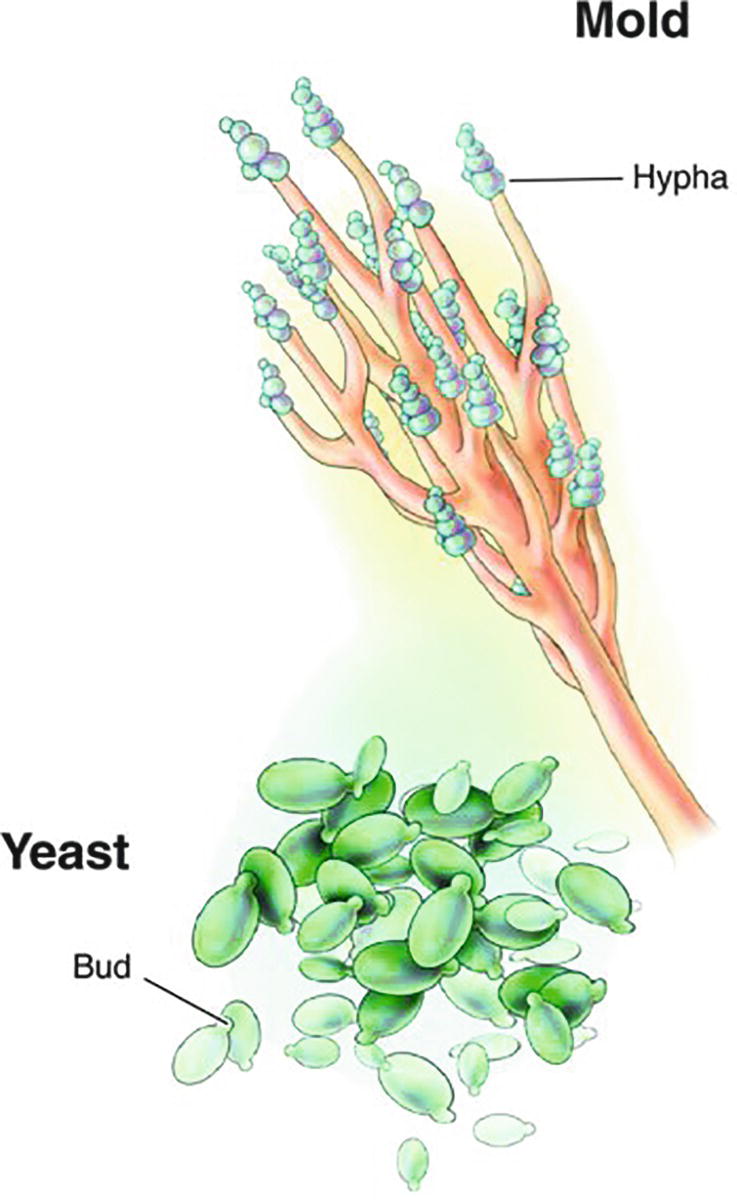

Fungi and parasites are eukaryotes: they are more complex than bacteria and viruses and have nuclei as well as other membrane-bound cell organelles (Fig. 23.2). Fungi can be in two forms: yeast (a unicellular form) or mold (filamentous form). Some fungi can even exist in either form and are known as dimorphic fungi. Candida, one type of yeast, can cause a variety of illnesses including vaginitis, oral thrush, and even invasive diseases such as endocarditis. Candida infections can affect patients with normal immune systems and can be acquired in the hospital. Many fungi are opportunistic, meaning they cause disease (or at least, more severe disease) in patients with weak immune systems (e.g., Aspergillus). Molds can also be classified by areas where they are endemic. As an example, histoplasmosis is more prevalent in areas bordering the Ohio River valley. Fluconazole and other antifungals can be used to successfully treat fungal disease. However, some serious fungal infections require treatment with amphotericin, an antifungal that can be very toxic to the kidneys.

FIGURE 23.2. Artist’s drawing of two varieties of pathogenic fungi: yeasts and molds. (From Ford SM. Roach’s Introductory Clinical Pharmacology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017, with permission.)

Parasites can be either a single-celled protozoa (such as malaria) or multicellular worms (such as hookworms). These infections can be acquired in a variety of ways including mosquitoes or contaminated food and can lead to gastrointestinal, liver, and lung disease and even death. Fortunately, there are antiparasitic medications available; however, many are toxic, and parasites continue to be a cause of worldwide disease outbreaks and mortality.

Viruses and Prions

Viruses are not cells at all (Fig. 23.3). They are typically composed of genetic material, surrounded by a protein shell, with or without a lipid membrane coat. They rely on their host’s cells to provide the machinery they need for replication. Once they have invaded a human’s cells, they can either destroy the cell or integrate their genetic material into the cell, inducing the cell to produce more infectious viral particles. Through this method, some are able to produce chronic infections such as HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), the incurable virus that causes AIDS. Just like other pathogens, viruses can affect a multitude of organs: for example, a virus can cause gastrointestinal disease (viral gastroenteritis) or neurologic disease (West Nile encephalitis). The severity of illness also ranges from the flu (Influenza virus) to viruses associated with very high mortality rates, such as the Ebola virus. Each virus has its own method of transmissibility (examples include through respiratory droplets, through fecal material, through contact, and even through mosquitoes bites). Traditional antibiotics usually do not have any effect on viruses. Often, we rely on the body’s immune system to fight off diseases, which are typically self-limited. For example, patients with the common cold (Rhinovirus) are not given antivirals. With exciting medical advances, however, we are able to cure some viruses with antivirals, such as hepatitis C. While other antivirals may not be curative, they can keep chronic disease well controlled. Antiretroviral drugs for HIV treatment are a good example of this.

FIGURE 23.3. Artist’s drawing of an example of a virus, DNA wrapped in a protein coating. A virus is acellular.

Prions are transmissible infectious agents composed only of protein. Diseases associated with prions include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”). The diseases are neurologic, incurable, and universally fatal. While they are not transmittable from person to person, contaminated instruments and blood products can lead to infections. Because they are neither cellular nor made of DNA, prions do not respond to standard disinfection or sterilization techniques; any possibility of prion disease requires specialized handling on the part of the anesthesia technician (see Chapter 47, Anesthesia Supply and Equipment Contamination, Sanitation, and Waste Management).

Prevention of Health Care–Associated Infections

Many of the above infections are contracted “in the community”; however, some infections are acquired only in the hospital. Health care–associated infections (HAI) are infections patients contract while receiving medical treatment in a health care facility. See Table 23.1 for types of health care–associated infections.

Table 23.1. Description of Various Health Care–Associated Infections (HAI)

Bacteria are the most frequent cause of surgical site infections, a type of HAI. Skin infections related to surgical incision sites are frequently caused by skin-inhabiting gram-positive bacteria (e.g., streptococci, staphylococci). Sterilizing and covering the skin of the patient and operators preoperatively can mitigate risk of infection; this is why there are surgical sterilization protocols. For most procedures, patients also benefit from antibiotics to prevent surgical site infection; these must be given prior to surgical incision in order to achieve maximum benefit. It may not seem urgent to give an antibiotic, but there is strong scientific evidence to show that giving antibiotics before surgical incision makes them most effective. Ensuring that the appropriate preoperative antibiotic is available promptly so that it can be given before surgical incision is an important role of the AT and one which is shown to improve patient outcomes.

Not all surgical infections come from the bacteria on our skin. Particularly when procedures involve nonsterile areas such as the bowel, infections can be secondary to gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes. This explains why perioperative antibiotics (another means of reducing surgical infection risk) vary based on the type of procedure a patient is about to have and the infectious organisms most likely to be encountered.

HAI leading to the severe invasive infections discussed in Table 23.1 are made even more hazardous by their frequent association with drug-resistant organisms. For example, MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) leads to many surgical infections and yet is unable to be killed by many of our standard antibiotics, including cefazolin. It requires specialized antibiotics such as vancomycin. For all of the above reasons, HAI may be deadly and yet are preventable; therefore, infection control strategies are a priority for all health care personnel and organizations. Anesthesia technician play an important role in many protocols for prevention of hospital-acquired infections, especially in the operating room.

Infection Control Precautions

The CDC utilizes important preventative strategies to avoid transmission of infectious agents within health care settings. These safety precautions are meant to be followed uniformly by health care personnel, patients, and their visitors. Safety precautions are two-tiered: standard precautions and transmission-based precautions. Standard precautions should be applied to the care of all patients in a health care setting regardless of their infectious status and/or risk of infection. Transmission-based precautions are specialized and are required in patients who are suspected of being infected or colonized with certain pathogens that necessitate additional measures to control infectivity. These precautions are taken in addition to standard precautions.

Standard precautions are based on the code that all blood, body fluids, secretions, and excretions may contain transmissible infectious agents. Abiding by these precautions demands proper hand hygiene, safe injection practices, and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) if there is an anticipated exposure to bodily fluids. Depending on the situation, PPE may include gloves, gowns, masks, eye protection, and/or face shield. For instance, if a health care provider anticipates potential bodily fluids splashing, a face shield should be worn. Standard precautions also apply to contaminated items in the patient’s environment; gloves should be worn when disposing of equipment that has been soiled by bodily fluid.

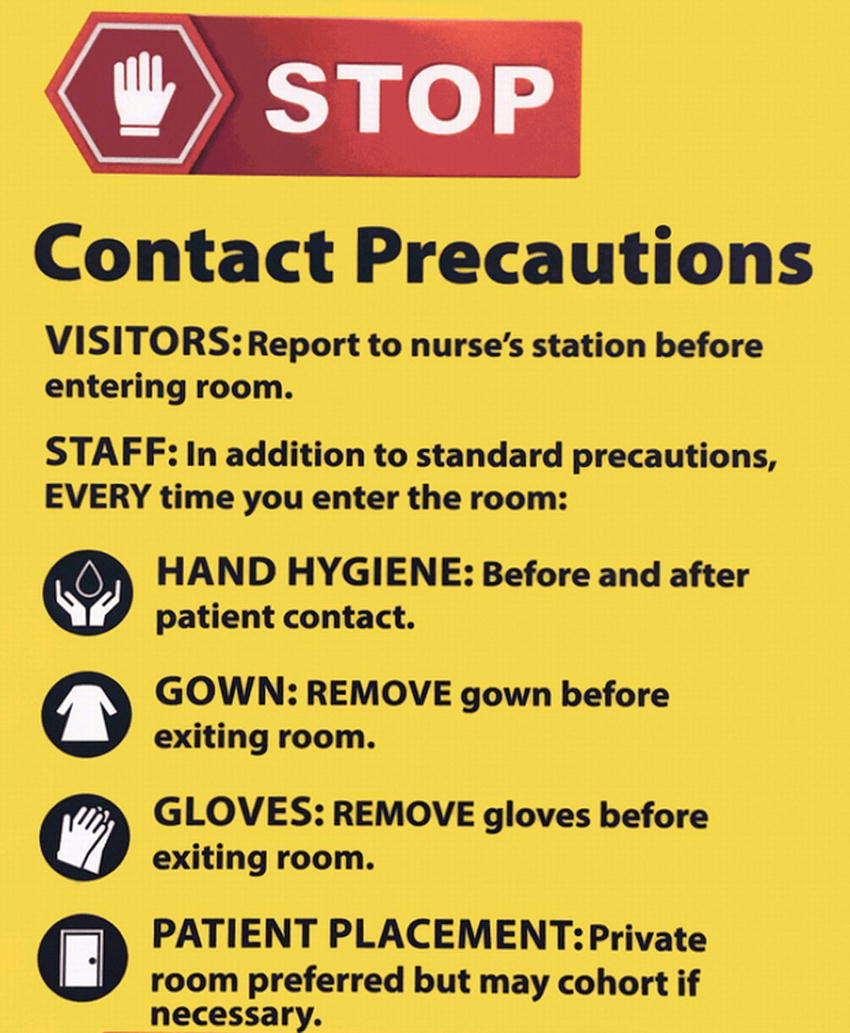

Transmission-based precautions include contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. These precautions can be used individually or in combination with one another. Again, transmission-based precautions are used in addition to standard precautions. The mode of a pathogen’s transmission determines the type of precaution(s) required. Contact precautions help prevent the transmission of pathogens spread through touching. Under these precautions, patients are often isolated into single-patient rooms and health care personnel are required to wear gloves and gowns upon room entry, even if there are no anticipated bodily fluid exposures (Fig. 23.4). Items of PPE must be discarded prior to exiting the patient room to avoid spread to the outside environment. Droplet precautions prevent pathogen spread through respiratory or mucous membrane contact. Rhinovirus is an example of a pathogen communicated in this manner. Under these precautions, single room isolation is again recommended. Masks are required for health care personnel entering the isolation room and for patients who are transported outside of the isolation room. Similarly, airborne precautions also prevent transmission of respiratory pathogens. However, these standards are more rigorous as these pathogens have a tendency to stay in the area over longer distances and are therefore more transmittable. Patients with these types of infections (tuberculosis, measles, chickenpox) are placed into rooms with negative air pressure that helps keep pathogens from spreading outside of the isolation rooms. Specialized N95 masks are used, which provide more protection than the standard masks.

FIGURE 23.4. Example of door sign detailing precautions.

At times, these precautions may seem tedious. However, these precautions, as well as other infection control health care initiatives, are crucial to reducing risks of HAI and risk of patient mortality. For example, the CDC has noted a 50% decrease in central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) between 2008 and 2014, which is thought to be due to the careful infection control practices of health care providers.

Exposure to Infectious Body Fluid

Blood-borne pathogens (HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus) are potentially acquired via contact with certain infectious bodily fluids: blood, semen, vaginal fluids, amniotic fluids, breast milk, cerebrospinal fluid, pericardial fluid, peritoneal fluid, pleural fluid, and synovial fluid pose risks. However, saliva, vomitus, urine, feces, sweat, tears, and respiratory secretions cannot transmit HIV unless the fluid is contaminated enough to be visibly bloody. Risk of transmission is also dependent on the method of fluid exposure. Cutaneous contact with infectious fluids only carries a risk of HIV transmission if there is nonintact skin. While exposed mucous membranes and percutaneous contact are also potential hazards, the risk of infection is greater with percutaneous (through the skin) exposure than with either mucous membrane or cutaneous exposure. Certain risk factors (i.e., involving hollow-bore needles, bloody devices, and/or deep injury) increase the likelihood of transmission.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Once an exposure has occurred, health care personnel must act quickly to minimize the chances of transmission. Upon exposure, one should immediately wash the area with soap and water. If the point of exposure is a mucosal area (such as the mouth or nose), then the area should be copiously flushed with saline. After cleansing, the person exposed should report the incident immediately. Facilities have individualized protocols on which person or facility handles the reports and offers postexposure medical attention (i.e., occupational health, supervisor, emergency room, etc.). Health care personnel should familiarize themselves with these protocols and not delay seeking treatment.

After reporting the incident, both the person exposed and the individual whose fluid was involved will be tested for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. If the risk of HIV transmission is significant, antiretroviral medications can be given immediately to the exposed personnel (postexposure prophylaxis). These medications can substantially reduce the chances of HIV transmission. However, they are more effective the sooner they are given, so it is critical to report any exposure to your institution’s occupational health practice as soon as possible.

Summary

There are several different types of pathogens that can cause infections in patients and health care personnel. These infections can occur both in the community and in health care settings. Understanding pathogens and their methods of transmissibility can help health care personnel prevent these infections. Following infection prevention, protocols will reduce the risk of transmission. If an exposure does occur, it is important to report this and seek further medical attention immediately.

Review Questions

1. Which type of pathogen is most often implicated in health care–associated infections?

A) Bacteria

B) Fungi

C) Virus

D) Prion

Answer: A

Bacteria are the most likely cause of HAI.

2. Wearing gloves when picking up a urine-soiled sheet is required under which type of precaution?

A) Standard

B) Contact

C) Airborne

D) Droplet

Answer: A

Standard precautions require that handling of soiled materials should always be performed with gloves. Standard precautions are practiced in all patients: other precautions may be added to standard precautions in the presence of certain infections.

3. Which of the following is not a health care–associated infection (HAI)?

A) Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI)

B) Influenza

C) Central line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI)

D) Surgical site infection (SSI)

E) Ventilator-associated pneumonia

Answer: B

Influenza is not normally considered an HAI. All the others are, by definition, health care–associated infections.

4. Which of the following diseases is not caused by a virus?

A) West Nile encephalitis

B) Ebola

C) HIV/AIDS

D) Cellulitis

E) The common cold

Answer: D

Cellulitis infections are generally bacterial.

5. Which of the following is true:

A) Gram-positive bacteria have a thin peptidoglycan wall and an outer membrane.

B) Some antibiotics are more effective against either gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria.

C) Gram-positive bacteria are the only cause of bloodstream infections.

D) Gram-positive bacteria are common causes of surgical site infections.

Answer: B

Antibiotics can be more selective against either gram-positive or gram-negative organisms depending on the antibiotic. For example, vancomycin is more effective against gram-positive organisms. Multiple bacteria and even nonbacterial pathogens can lead to bloodstream and surgical site infections. Gram-negative bacteria have a thin peptidoglycan wall and an outer membrane.

6. Rank in order the risk of HIV transmission in the following scenarios:

A) Needlestick from a large-bore needle used on an HIV-positive patient

B) Medium volume of HIV-positive patient’s nonbloody saliva in a health care personnel’s eye

C) Small amount of an HIV-status unknown patient’s blood splashing into a health care personnel’s eye

Answer: A, C, BNeedlestick exposure has a greater risk of transmission than mucosal exposure. Nonbloody saliva is unlikely to lead to HIV transmission.

7. Which lethal pathogen cannot be disinfected with standard methods?

A) Fungi, because they exist in multiple forms

B) Viruses, because they can be airborne

C) Gram-positive bacteria, because they have a thick cell wall

D) Prions, because they are not cells and do not contain DNA

Answer: D

Prions are unique transmissible infectious agents composed only of protein. They cause incurable, fatal neurologic diseases. Because they are neither cellular nor made of DNA, prions do not respond to standard disinfection or even sterilization techniques. Contaminated instruments and blood products can lead to infections. Even the possibility of prion disease requires specialized handling of all instruments and everything in the environment of the patient.

SUGGESTED READINGS

CDC. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/isolation/Isolation2007.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2016.

CDC. Health Care Associated Infections. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/infectionTypes.html. Accessed September 10, 2016.

Gupta PK. Microbiology Cell Physiology and Biotechnology. Meerut, India: Rastogi Publications; 2008.

Murray PR, Rosenthal K, Pfaller M. Medical Microbiology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

USCF Clinical Consultation Center. PEP Quick Guide for Occupational Exposures. Available from: http://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/pep-resources/pep-quick-guide/. Accessed September 10, 2016.