CHAPTER 39

Airway Devices

Introduction

Airway management is a crucial component of safe anesthesia practice. Patients under anesthesia commonly need assisted ventilation and oxygenation. This textbook has covered the anatomy of the airway (in Chapter 7), principles of airway management (in Chapter 18), and the approach to emergency airway management (in Chapter 57). One of the most critical features of airway management emphasized throughout this text is the need for rapid responsiveness and flexibility in changing and urgent situations. Airway plans can change instantly, and every member of the anesthesia team must have detailed, on-the-spot knowledge of the full spectrum of possible outcomes, plans, and equipment in order to care for patient safely.

Manufacturers have responded by producing a tremendous variety of devices and tools designed to address common and uncommon issues arising from the inherent complexity of airway management. The topic of airway equipment will be your area of expertise. It is so broad that the editors, for this textbook, have chosen to divide it into airway devices, that is, things that remain in the airway to assist with oxygenation or ventilation (most of which are disposable), and airway tools (covered in the next chapter), that is, things that are used to visualize, open, or place devices in the airway (most of which are reusable).

Airway devices can be broadly classified into invasive and noninvasive devices capable of delivering oxygen, maintaining airway patency, and assisting with ventilation tailored to each patient’s specific needs. This chapter offers an overview of different devices and a brief introduction to common indications for use, maintenance, troubleshooting, and alternatives.

Nasal Prongs—Passive Oxygenation

Nasal Cannulas

Nasal cannulas are designed to deliver oxygen to the nasopharynx. A nasal cannula apparatus consists of a long plastic tube with dual 0.5 to 1-cm prongs, one for each nostril (Fig. 39.1). Nasal cannulas are designed to function with an oxygen flow ranging from 2 to 4 L/min. Higher flows may cause discomfort and nasal irritation. Unlike face masks, nasal cannulas do not have their own reservoir, although the nasopharynx itself can act as a reservoir and gather a small amount of oxygen while the patient is not actively breathing in. The fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2) delivered is variable, as there is mixing with room air; it also depends on the pattern of breathing between the mouth and the nose. Nasal cannulas work very well for patients who primarily breathe through the nose, but even patients who breathe through their mouths will generate oxygen flow, as the air inhaled through the mouth pulls oxygen down through the nasopharynx. FiO2 is anywhere from 0.30 to 0.40.

FIGURE 39.1. Simple nasal cannula.

Many nasal cannulas now have modifications allowing monitoring of end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) by sampling exhaled gases usually through the second nasal prong. Nasal cannulas with EtCO2 monitoring (Fig. 39.2) are useful for procedures performed under sedation and provide real-time information including respiratory rate and an estimate of EtCO2. Recall from Chapter 31 that EtCO2 monitoring, either via the nasal cannula or the face mask, is now an ASA standard for monitored anesthesia care.

FIGURE 39.2. Nasal cannula with end-tidal CO2 monitoring.

Face masks—Passive Oxygenation

Standard Face Mask

A standard face mask delivers supplemental oxygen from a source (a tank or pipeline) to both the patient’s mouth and nose (Fig. 39.3). Face masks hold an average volume of approximately 200 cc. Because patients receiving oxygen from a face mask often rely on the supplemental oxygen, adequate flow must be checked by looking at the flowmeter for pipelines or the pressure if using a tank. An E-cylinder O2 tank has a capacity of up to 2,200 psi of pressure, which corresponds to approximately 660 L of oxygen. The pressure in the tank is directly proportional to the amount of oxygen in liters. If the tank reads 1/3 of the pressure, it will have 1/3 of the amount of oxygen in liters or approximately 220 L, enough for 22 minutes of oxygen delivery with a flow of 10 L/min.

FIGURE 39.3. Simple face mask.

Standard face masks deliver an FiO2 between 0.30 and 0.50 when connected to oxygen sources delivering O2 flow between 6 and 10 L/min. One important disadvantage of standard face masks is the mixing that occurs with room air and the rebreathing of exhaled gases that impose a limit to the FiO2 standard face masks are able to deliver. An adequate seal and higher flow rates minimize this mixing to some degree, increasing the amount of fresh gas available for each breath. Additionally, at flows lower than 6 L/min, rebreathing of exhaled CO2 begins to become a concern.

Nonrebreather Face Mask

Standard face masks deliver oxygen that mixes with exhaled gases, resulting in rebreathing of CO2 and limiting the maximum FiO2 that may be delivered. Nonrebreather masks are designed to minimize the dilution of the delivered oxygen using one-way valves, one opening from the reservoir on inhalation and two valves on each port opening during exhalation and closing during inhalation (Fig. 39.4). Nonrebreather masks can deliver an FiO2 ranging from 0.70 to 0.80. Good fitting of the mask is essential for an adequate FiO2 and minimal rebreathing of CO2.

FIGURE 39.4. Nonrebreather face mask.

Venturi Mask

Venturi masks have a mechanism designed to adjust the concentration of inspired oxygen by adjusting the flow of supplemental O2 (Fig. 39.5). The adjustable mechanism consists of a Venturi device indicating the flow required to deliver the FiO2 desired. Venturi devices are commonly color coded for different flow rates and FiO2. Venturi masks are more consistent and reliable in regard to the FiO2 when compared to standard face masks. The amount of oxygen delivered is dependent on the size of the adaptor.

FIGURE 39.5. Venturi face mask.

Tracheostomy Mask

Tracheostomy masks deliver oxygen around a tracheostomy or stoma site located on the patient’s neck (Fig. 39.6). It rests on top of the tracheostomy site and is typically held in place by a strap. The oxygen delivered should be humidified for anything other than brief use. Recall from Chapter 7, Respiratory Anatomy and Physiology, that one of the important functions of the nose and mouth is to humidify and warm gases before they reach the large airways. Without the nose, cold dry gas delivery results in dry secretions, mucus plugging, and airway obstruction. Additionally, the lower airways are more friable and susceptible to bleeding due to irritation exacerbated by dry, cold air.

FIGURE 39.6. Tracheostomy mask.

Face Tent or Shovel Mask

Face tent masks deliver oxygen by resting on the patient’s chin and delivering oxygen flows between 8 and 10 L/min (Fig. 39.7). The FiO2 provided by this type of mask is difficult to control due to the significant amount of mixing that occurs with room air. It is often used for patients who may not tolerate a standard face mask, such as delirious patients emerging from anesthesia that may constantly pull at a tight face mask. It can also be convenient when providing humidification with oxygen. Some disadvantages include unpredictable FiO2 and difficulty maintaining the mask in place, especially in patients with nasogastric or orogastric tubes.

FIGURE 39.7. Shovel mask.

Face masks—Positive Pressure Masks

Basic Anesthesia Masks for Positive Pressure Ventilation

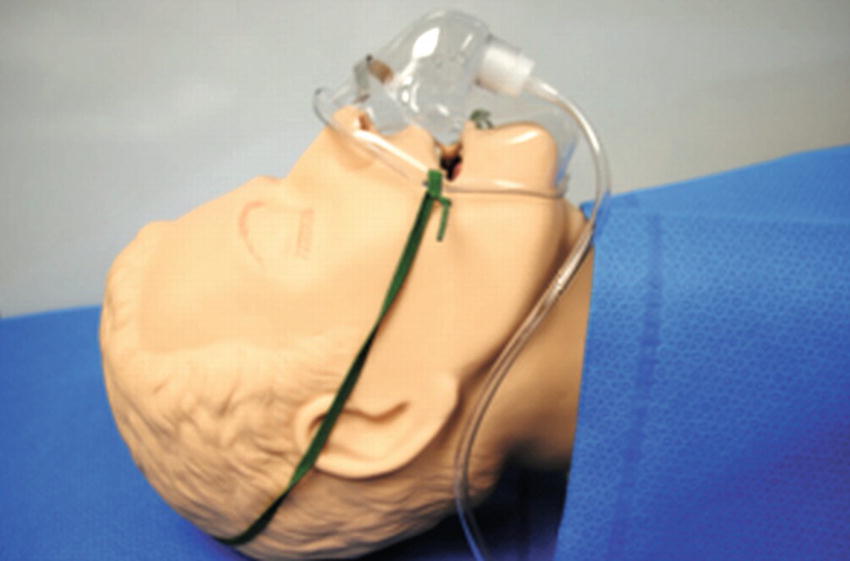

Masks designed to deliver positive pressure ventilation achieve this by forming a seal around the nose and mouth of the patient. The seal is created primarily by a low-pressure inflatable cuff around the edges that may be adjusted by adding or removing air within the cuff with a syringe.

Newer masks are made out of clear plastic (typically nonlatex) and are designed for single use only (Fig. 39.8). Older masks were made out of black, reusable latex rubber. These were eventually replaced due to the cost of resterilization and the inability to see condensation with gas exchange, secretions, or even vomit if present. Other features present in these newer clear plastic masks include a ring with four prongs to attach a head strap to the patient’s face. Some anesthesia circuits are packaged including a uniform size of these single-use masks as well. The ring containing prongs may be color-coded to easily indicate the size of the mask. The mount, the opening to which the anesthesia circuit is connected, is a 22-mm female inlet that commonly attaches to an angle piece or directly to the circuit. Adult masks are commonly available in three sizes: small, medium, and large. The medium size fits the majority of adults and one should be available in preparation of every anesthetic.

FIGURE 39.8. Positive pressure mask.

BiPAP/CPAP Masks

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) masks are modes of noninvasive ventilation used for a variety of indications. They are increasingly used for patients in phase I recovery and the intensive care unit. CPAP and BiPAP masks form a tight seal to optimize the delivery of gas and flow ensuring the delivery of specific airway pressures as set by the technician. There are many variations to the design of these masks including total face masks (Fig. 39.9), oral masks, nasal masks, and high-flow nasal cannulas (Fig. 39.10), which provide a small amount of positive pressure.

FIGURE 39.9. CPAP BiPAP face mask.

FIGURE 39.10. High-flow nasal cannula.

Endoscopy Masks

Endoscopy masks are positive pressure masks modified to accommodate an endoscope with minimal disruption to ventilation (Fig. 39.11). Endoscopy masks contain an opening through which the endoscope is inserted and ventilation may continue from a seal developed around the inserted scope.

FIGURE 39.11. Endoscopy mask.

Nasopharyngeal Airways

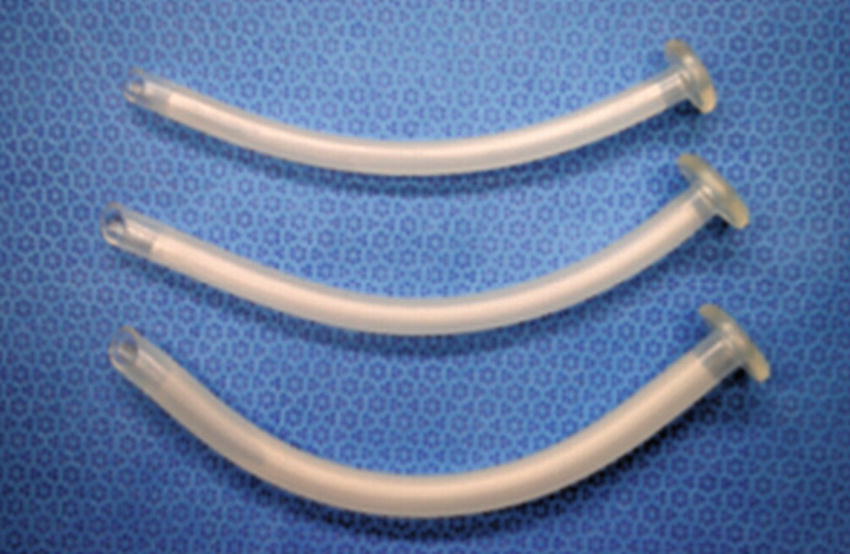

Nasopharyngeal airways (NPAs) or nasal trumpets are soft, long devices designed to relieve the obstruction to flow of oxygen or air caused by the soft tissue leading to the glottic opening (Fig. 39.12). The NPA is commonly used to bypass the tongue and soft palate, and the distal end should sit just at the opening of the epiglottis. Similar to the OPA, NPAs come in different sizes, and every anesthesia provider should have access to various sizes during each procedure. In contrast to the oropharynx, the nasopharynx is friable and prone to bleeding with traumatic insertion of an NPA; they are often avoided in patients who are anticoagulated or who have recent trauma to the nose. Lubrication must be available as it is often necessary prior to insertion to help minimize nasal mucosal trauma and nosebleeds, a common complication of NPA usage. Patients at lighter planes of sedation, however, generally tolerate NPAs; a patient who is snoring, but still has an intact gag reflex, will often tolerate a nasal airway after emergence from anesthesia or during a MAC anesthetic.

FIGURE 39.12. Nasopharyngeal airways (NPAs) in various sizes.

Oropharyngeal Airways

An oropharyngeal airway (OPA) consists of a plastic, semirigid, single-use device built for the purpose of stenting open the airway and relieving obstruction to flow from the tongue and soft tissue in the sedated, anesthetized, or obtunded patient. It is often used after induction of general anesthesia when mask ventilation is challenging, when patients are deeply sedated during monitored anesthesia care, or immediately following extubation. The ability to tolerate an OPA suggests compromise of the gag reflexes at the base of the tongue. OPAs are made in different sizes, and standardized sizes are commonly represented by different colors. Pediatric sizes as small as 40 mm and large adult sizes as large as 110 mm in length are available to allow for adequate flow of oxygen or air when breathing spontaneously or used to optimize mask ventilation.

A commonly used oral airway is the Guedel oral airway (Fig. 39.13). A Berman OPA is a variation of the Guedel OPA with grooves on each side providing an unobstructed path for air or oxygen flow (Fig. 39.14). The selection of an appropriate size prior to placement of an OPA is important, and every member of the anesthesia team should have access to different sizes for every patient prior to the delivery of each anesthetic.

FIGURE 39.13. Guedel oropharyngeal airways in various sizes.

FIGURE 39.14. Berman oropharyngeal airway.

Laryngeal Mask

A laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is conceptually a combination of a mask (can be used to provide positive pressure for ventilation) and an oral airway (it is designed to relieve and bypass any obstruction that may occur in the oropharynx). The LMA is positioned in the larynx on the back of the throat just outside the airway opening above the vocal cords and is attached to a ventilation tube designed to connect to a standard breathing circuit or ventilation bag (Fig. 39.15). While older LMAs were reusable, most modern LMAs are available as single-use devices intended to enhance ventilation by forming a more reliable seal close to the glottis. It is easily inserted through the mouth without the need for additional instruments. The tube delivers the flow from the ventilator, and the base forms a seal with the inflatable cuff containing up to 20 cc of air. Some LMAs have protective slits to prevent the epiglottis from obstructing the distal opening of the device. These LMAs are not designed for intubation and do not allow the passage of an endotracheal tube (ETT). LMAs are available in many different sizes, fitting a wide range of patients from small neonates to large adults. Manufacturers typically recommend a size based on the patient’s weight, and ultimately the size might need to be increased due to a large air leak or decreased in case of a small mouth opening preventing easy insertion.

FIGURE 39.15. Laryngeal mask airway.

LMAs have been widely used since the late 1980s and are an essential component of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) difficult airway algorithm as a valuable rescue tool. LMAs are important for the safe practice of anesthesia and must be immediately available for all anesthetizing locations as part of an airway emergency kit and setup. LMAs are produced by a variety of manufacturers that have responded by creating devices with variations designed to enhance the LMA basic function.

iGels

iGels are similar to laryngeal masks (LMAs) in regard to function, indications, and insertion technique. In contrast to a traditional LMA, iGels do not have an inflatable cuff. The soft plastic and elastic polymer are designed to optimize a seal when exposed to the patient’s body temperature in the supraglottic tissue.

Intubating Laryngeal Masks

Intubating LMAs are designed specifically to be used to aid in the placement of an ETT in situations in which conventional intubation with direct laryngoscopy might not be easily achieved (such as with a patient that needs to be intubated unexpectedly while in the lateral position) or after direct laryngoscopy has already proven unexpectedly difficult and an ETT was unable to be successfully placed. There are many different types of intubating LMAs. These have been altered from the standard more commonly used LMA in various ways. This may include larger internal diameters to accommodate larger ETTs, more rigid design/material, accessories such as stylets to help push an ETT through the shaft, and the removal of fenestrations/ridges often found at the end of ETTs to prevent obstruction by the epiglottis. Cookgas and LMA™ North America/LMA™ International produce two of the most popular and commonly available intubating LMAs.

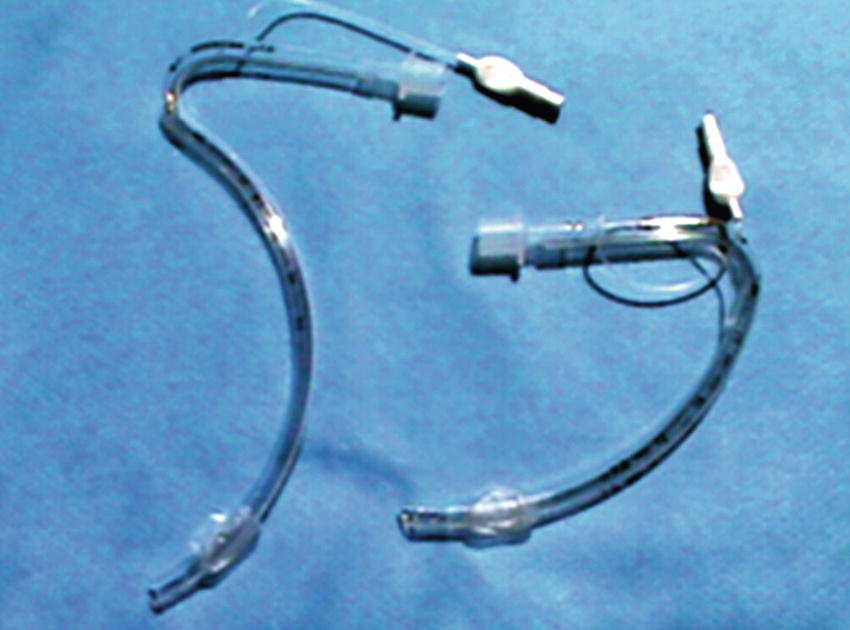

- Air-Q (Cookgas): The Air-Q intubating LMA is designed to overcome some of the limitations of the classic LMA. Air-Q LMAs have a short shaft and an acute curve without protective slits at the distal opening to allow for the passage of an ETT (Fig. 39.16). Placement of an ETT through an Air-Q LMA is commonly performed with a fiberoptic bronchoscope using the Air-Q as a conduit but may be accomplished blindly. Removal of the Air-Q LMA after intubation is done using a specially designed stylet to stabilize the ETT as the LMA is removed; the risk of dislodging the ETT during this maneuver is not zero. The anesthesia provider may choose instead to leave the Air-Q LMA in place after intubation if securing the airway was particularly difficult.

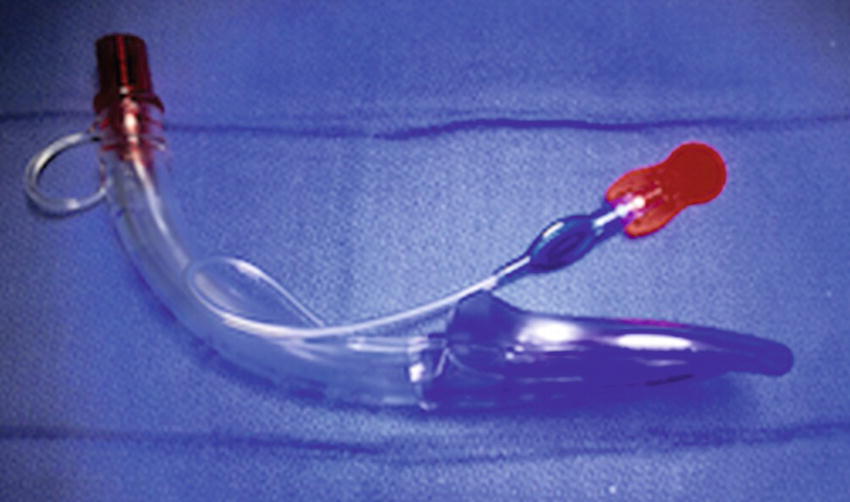

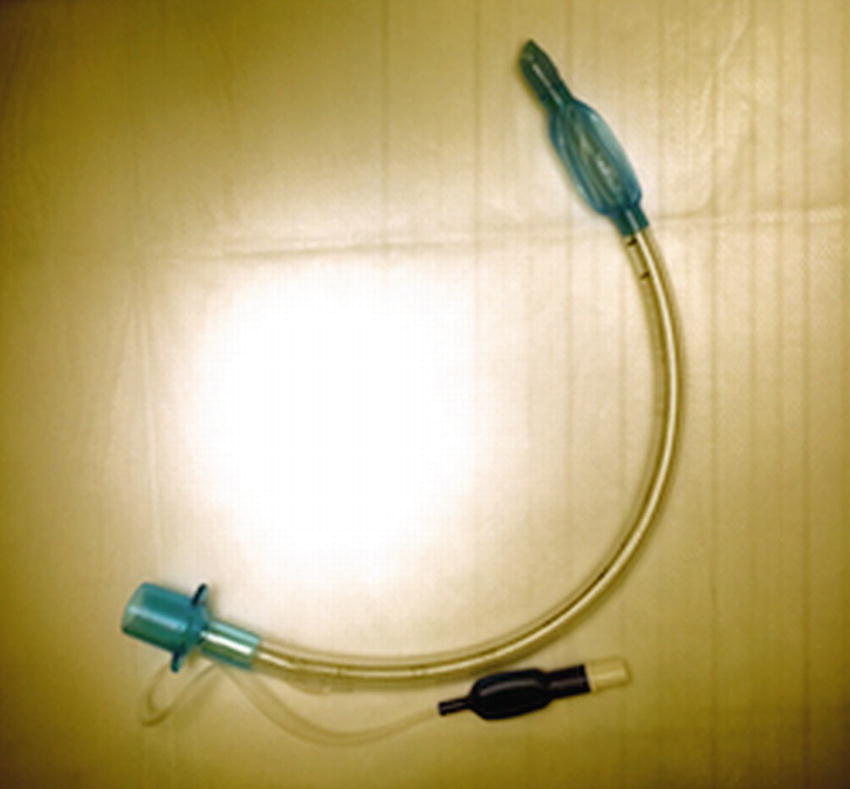

- LMA Fastrach™: The LMA Fastrach™ illustrated in Figure 39.17 has three components, the LMA, an obturator with a rigid handle, and a flexible ETT with an adaptor. The assembled device is inserted blindly, and adequate ventilation is confirmed with chest rise and EtCO2 prior to insertion of an ETT. ETT placement can be achieved blindly or performed with a bronchoscope, at which point the intubating LMA may be removed or left in place. The device is most commonly used in difficult airway scenarios.

FIGURE 39.16. Air-Q intubating laryngeal mask airway.

FIGURE 39.17. LMA Fastrach intubating laryngeal mask airway.

Combitube and Laryngeal Tubes

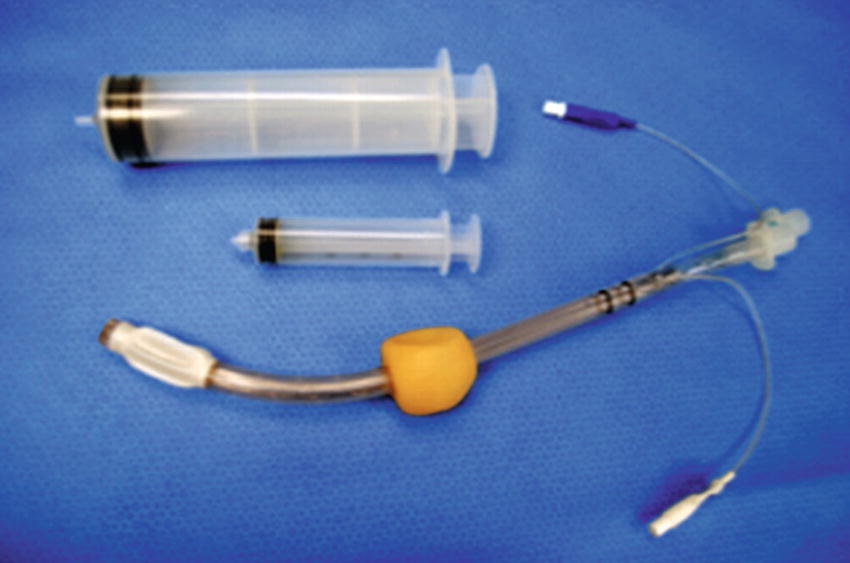

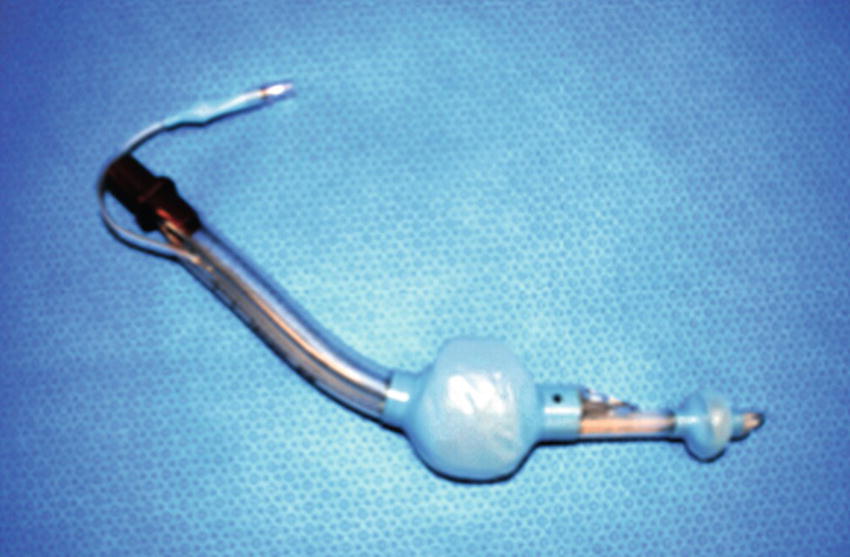

The Combitube and the laryngeal tube are two types of emergency airway devices (Figs. 39.18 and 39.19). These devices are sometimes utilized by emergency personnel outside the OR environment in situations where intubation or mask ventilation is challenging. Anesthesiologists in controlled settings do not routinely use the Combitube or the laryngeal tube but may be called upon to intubate patients being ventilated with these devices in the emergency room.

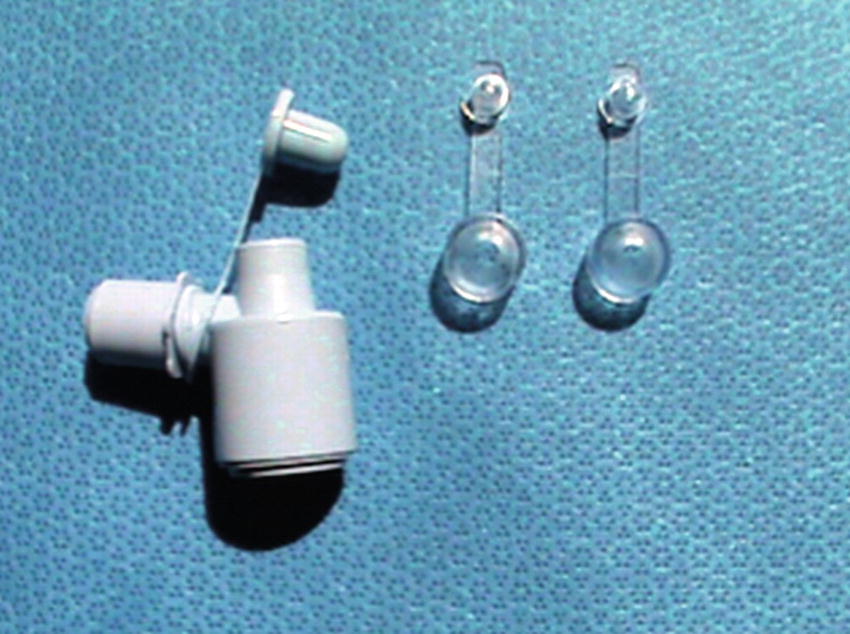

FIGURE 39.18. Combitube with syringes for each balloon.

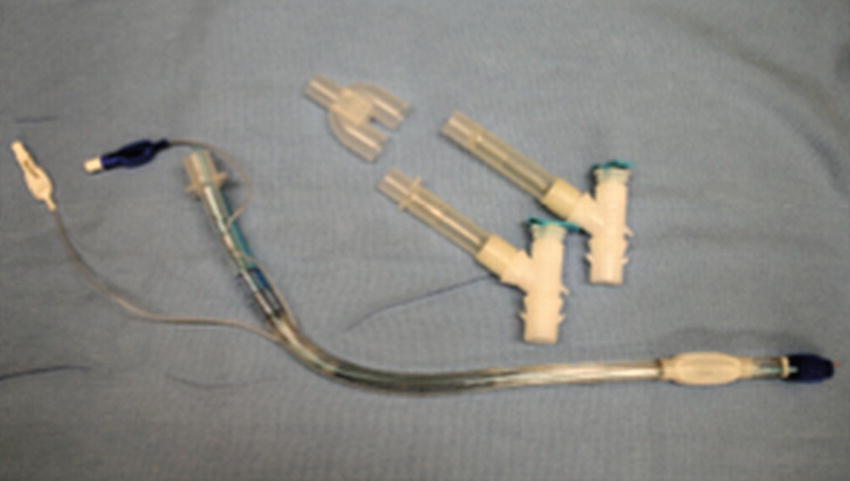

FIGURE 39.19. King laryngeal tube.

Both devices consist of a large tube with two separate cuffs and two inflation ports, one for the distal and a second for the proximal cuff. The devices are designed to enter the oropharynx and pass behind the larynx all the way into the esophagus, resulting in obstruction of the esophagus. With the esophagus obstructed, the air then moves through the other pharyngeal lumen along the path of least resistance through the larynx and into the lungs. When using a Combitube/laryngeal tube, lubrication must be available as well as two syringes for each port. These devices are designed to be for temporary use and are available in a limited number of adult sizes, commonly available in 37 Fr and 41 Fr. The size is determined by the patient’s height. The use of the Combitube is limited by its availability, complications associated with its use (failed intubation, aspiration, laryngeal trauma), and the high cost per unit compared to other devices and techniques available for securing the airway.

Endotracheal Tubes

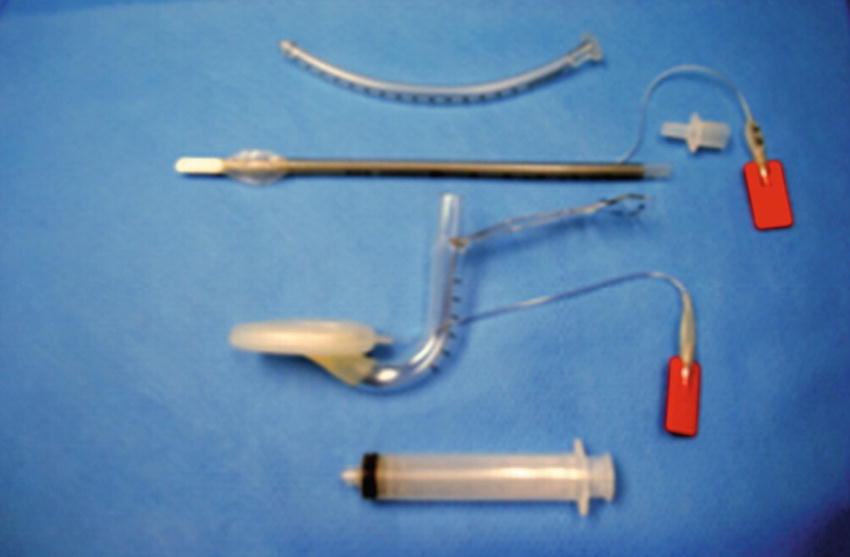

Endotracheal intubation with an ETT is considered to be the most secure method for airway management. ETTs protect the airway from gastric secretions and allow for positive pressure ventilation with virtually no risk of gastric inflation when properly sized and cuffed. Proper placement of an ETT can be confirmed by detection of end-tidal CO2, auscultation of bilateral breath sounds, or in some instances bronchoscopy, which is the most reliable method to confirm correct placement of an ETT. In addition, ETTs allow for more precise titration of tidal volumes and pressure and prevent the leakage of anesthetic gases into the operating room environment that may occur from other devices such as a face mask and LMAs, even when properly sized. ETTs are broadly classified as cuffed or uncuffed and are available in sizes ranging from 2.5 to 10.5 mm. Cuffed tubes have a pilot balloon to inflate the distal cuff designed to accommodate a large volume of air (up to 6-8 cc), which results in lower overall pressures against the tracheal wall (Fig. 39.20). Larger volume cuffs with lower pressures decrease the incidence of some of the complications associated with ETT placement.

FIGURE 39.20. Cuffed endotracheal tube with distal cuff and proximal pilot balloon.

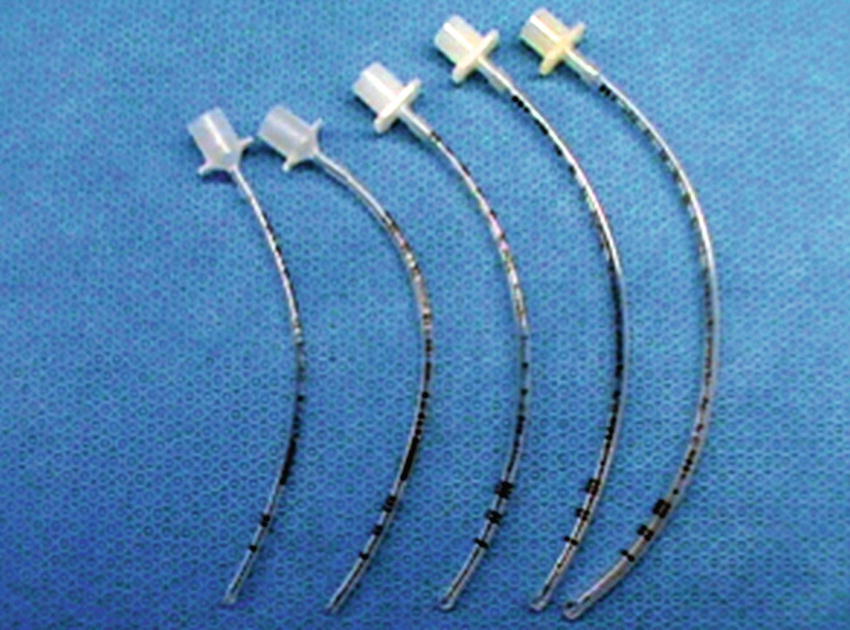

Uncuffed tubes have been used in children (younger than 8 years old typically) due to the anatomical airway differences compared to adults (Fig. 39.21). In children, the narrowest part of the airway is the cricoid cartilage, and the use of an uncuffed tube may already provide an adequate seal at the cricoid cartilage while not needing to apply much pressure to the tracheal tissues below.

FIGURE 39.21. Uncuffed endotracheal tubes.

Cuffed tubes are needed in adults, however, to form an adequate seal. The cuff consists of a small inflatable balloon connected with a pilot balloon proximally. The pilot balloon can be felt and used as a guide to approximate the volume or pressure being applied by the distal balloon to the patient’s tissues. A more precise measurement of the pressure in the cuff is possible with an ETT manometer. ETTs have been manufactured with a myriad of variations of its basic design to optimize intubation with different techniques.

- Parker tube: Parker ETTs have a flexible centered, downward facing, and tapered tip (Fig. 39.22). It is used in cases where standard ETT insertion is anticipated to be more difficult or a less traumatic insertion is desired, for example, when an ETT is inserted over a bronchoscope.

- Nasal or Oral RAE tubes (named after its inventors Ring, Adair, and Elwyn) are manufactured with a premade curve; useful in cases where bending a standard ETT would likely result in kinking and the connection to the circuit would interfere in the surgical field. Nasal RAEs may be inserted using a Magill forceps (Fig. 39.23). A fiberoptic bronchoscope for initial placement and verification of position may also be used. Nasal RAE tubes, illustrated in Figure 39.24, are routine and usually necessary for nasal intubation. Many anesthetists will soften the nasal RAE in a bottle of warm saline prior to placement to minimize trauma to the nose. The usual operating room indication for nasal intubation is surgery in the mouth: a nasal RAE is longer to accommodate the larger distance of the nasopharynx, and its shape directs the ETT away from the mouth, whereas a standard ETT directs the stiff connector facing toward and obstructing access to the mouth.

- Wire-reinforced tubes contain a metal coil embedded in the body or plastic of the tube, which can help protect the tube from kinking as it bends (Fig. 39.25). The wire reinforcement is permanently built into the ETT and is not detachable. Wire-reinforced tubes are generally more flexible and are more likely to need a stylet for intubation. A particular disadvantage of wire-reinforced tubes is their “memory.” If significant amounts of pressure are applied to the wires (such as a patient biting down on the ETT), the tube can become occluded or bent, and the metal permanently retains this shape leading to occlusion that becomes difficult to overcome and ventilate through. Having a bite block available is highly recommended. It is also important to remember that these ETTs, unlike most standard ETTs, are not MRI compatible.

- Laser-safe ETTs are used in laser surgery where the risk of an airway fire is significant. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a plastic material commonly used in the manufacture of ETTs, readily absorbs heat and may catch fire when exposed to operating room lasers, resulting in the devastating and possibly fatal consequence of fire in the airway. Specially designed polymer laser-resistant tubes (Fig. 39.26), as well as flexible metal ETTs made of flexible stainless steel, provide laser-resistant ETTs that can be used for ventilation during CO2 and KTP laser surgeries (see Chapter 55, Laser Safety).

FIGURE 39.22. Parker endotracheal tube with curved distal tip.

FIGURE 39.23. Magill forceps.

FIGURE 39.24. RAE nasal (left) and oral (right) endotracheal tubes.

FIGURE 39.25. Wire-reinforced endotracheal tube.

FIGURE 39.26. Laser-safe polymer tube.

ETT Adapters

ETT adapters connect on one end to the proximal end of the ETT (at a standardized universal gauge) that connects on the other end to an anesthesia machine breathing circuit, ventilation bag, or suction device. ETT adapters are commonly attached to elbow devices designed to help offset the strain on the ETT from the weight of the breathing circuit, decreasing the likelihood of kinking, shifting of ETT position, or inadvertent patient extubation. Elbow adapters are included in most breathing circuit replacement kits.

There are several variations to ETT adapters. The most notable include extender adaptors to lengthen the circuit after the “Y” connector (Fig. 39.27), heat and moisture exchange (HME) adaptors to prevent excessive heat and moisture loss from the patient (Fig. 39.28), medication adaptors to administer aerosolized medications such as albuterol, flexible “accordion” adaptors, and bronchoscope adaptors that allow insertion of a fiberoptic bronchoscope with minimal circuit leak (Fig. 39.29). Most ETT adapters are ISO compliant devices (ISO 5356-1), which consist of a connection measuring 15 mm I.D. with a 22-mm O.D.

FIGURE 39.27. Endotracheal tube extension adapter.

FIGURE 39.28. Heat and moisture exchange adapter.

FIGURE 39.29. Fiberoptic bronchoscope adapter.

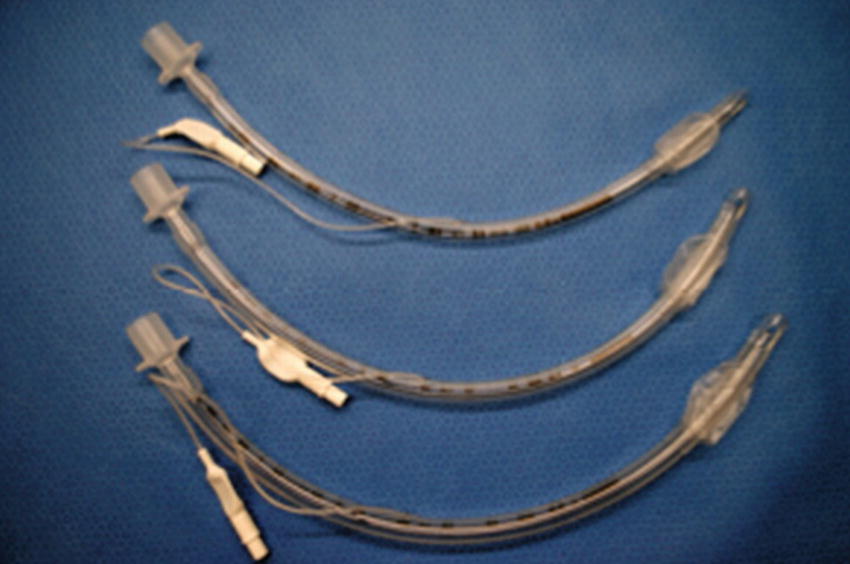

Double-Lumen Endotracheal Tubes

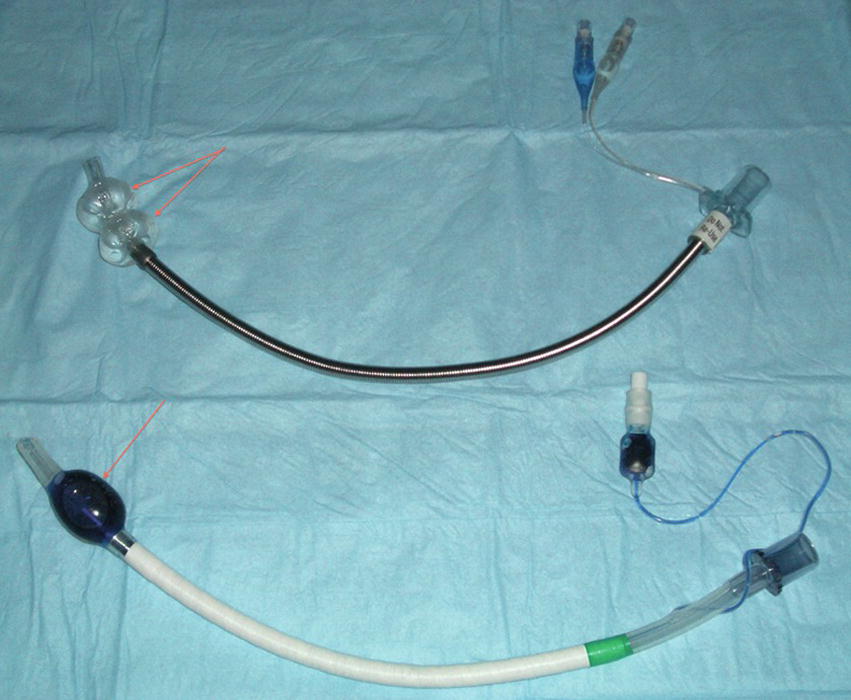

Double-lumen endotracheal tubes (DLTs) are primarily designed for procedures in which one-lung ventilation, lung isolation, or differential ventilation of both lungs is indicated.

Appropriate placement of a DLT is crucial for successful intubation for one-lung ventilation (OLV) or lung isolation. Although auscultation can be used to assess placement, it is common practice to verify correct placement with fiberoptic bronchoscopy. After confirmation of placement, changes in position of either the tube, the patient, or the surgical field commonly lead to displacement of the tube, and a fiberoptic bronchoscope should be available throughout the entire case in the event repositioning or evaluation is necessary. This is particularly the case for right-sided double-lumen tubes, as the right lung has more lobar bronchi than the left (see Chapter 7, Respiratory Anatomy and Physiology) and is thus more challenging for positioning.

Placement of a DLT is considered to be technically challenging due to its rigidity, length, and width, more so than intubation with a single-lumen ETT. If using a standard laryngoscope for intubation with a DLT, a Mac 3 blade may be used to facilitate insertion by providing maximum space for visualization of the glottic opening while the tube is inserted, typically done with the distal angle facing up. A video laryngoscope can also be used.

DLTs are significantly larger and more of a challenge for the patient’s larynx and trachea to accommodate than a single-lumen tube. They come in a variety of sizes (Fig. 39.30). Anesthetists have different preferences regarding the subtleties of sizing for patients. A too-large tube will not pass easily and may injure the larynx or trachea if forced: a too-small tube will require overinflation of the bronchial cuff, causing pressure injury at the carina, and may slip down too far, causing injury deeper in the airway. A 35F tube is clearly most appropriate for a small woman and a 41F best for a very large man. Between these extremes are the 37F and 39F; the anesthetist judges for an individual patient. Height, gender, age, body habitus, and ease of insertion are all important considerations when choosing an appropriate size for a DLT. It is important to have several sizes available at the time of placement.

FIGURE 39.30. Double-lumen endotracheal tube.

- Right DLTs are specifically designed to insert into the right bronchus and are notoriously challenging for placement when compared to the left DLT due to the more complex anatomy of the right lung. Right DLT may be used in instances in which there are significant changes to the anatomy of the left main bronchus or when the tube may directly interfere with the surgical approach, such as during a left pneumonectomy in which the entire left lung and left mainstem bronchus will be removed. Your department, depending on its volume of thoracic surgery, may not stock R double-lumen tubes in all sizes; this is important to know.

- Left DLTs are the most commonly used type of DLT. Both right- and left-sided DLTs achieve lung isolation when properly placed and verified. In contrast to right DLTs, left-sided DLTs are technically easier to place due to the anatomy of the left mainstem bronchus compared to the right.

Endobronchial Tubes

Endobronchial tubes are special ETTs that are designed to be placed deep into the trachea and down into just one lung, typically the left lung due to anatomical restrictions of a shorter and more complicated opening to the right lung (Fig. 39.31). They have some advantages to DLTs in that they are smaller in diameter and more flexible, making them easier to place than the larger, more rigid double-lumen tubes. These tubes also have a smaller, higher pressure distal cuff that needs significantly less air inflation to make a good seal.

FIGURE 39.31. Single-lumen tube specifically designed for endobronchial use, with small distal cuff and blunt distal opening.

Endobronchial Blockers

Endobronchial blockers (EBs) are useful when selective collapse of a lung or lobe is desired. EBs consist of a long, thin tube with a cuff at the distal end that can be inflated to obstruct airflow to a specific lung. An EB is used through a standard single-lumen tube. This provides several major advantages. In some cases, the large, stiff double-lumen tube can be difficult to place, particularly if patient anatomy is abnormal. If the patient is already intubated with a standard single-lumen tube, or if the patient will be left intubated at the end of the procedure, the single-lumen tube does not have to be changed. Bronchial blockers can also occasionally be used to isolate specific lobes of a lung rather than produce complete unilateral lung collapse.

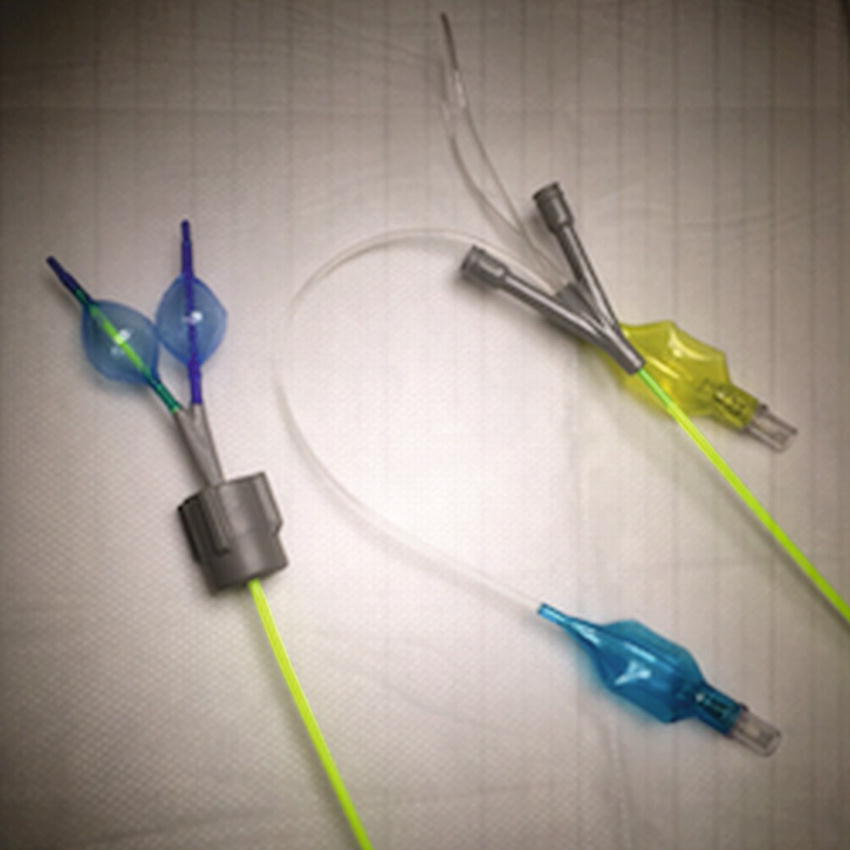

The biggest challenge with EBs is that they can be difficult to place in the correct spot. The use of bronchial blockers still requires a fiberoptic scope to confirm its proper placement for one-lung ventilation. Different manufactures have responded by adding variations to the basic design that may facilitate placement or make it more secure. There are at least four varieties of endobronchial blockers with some unique features.

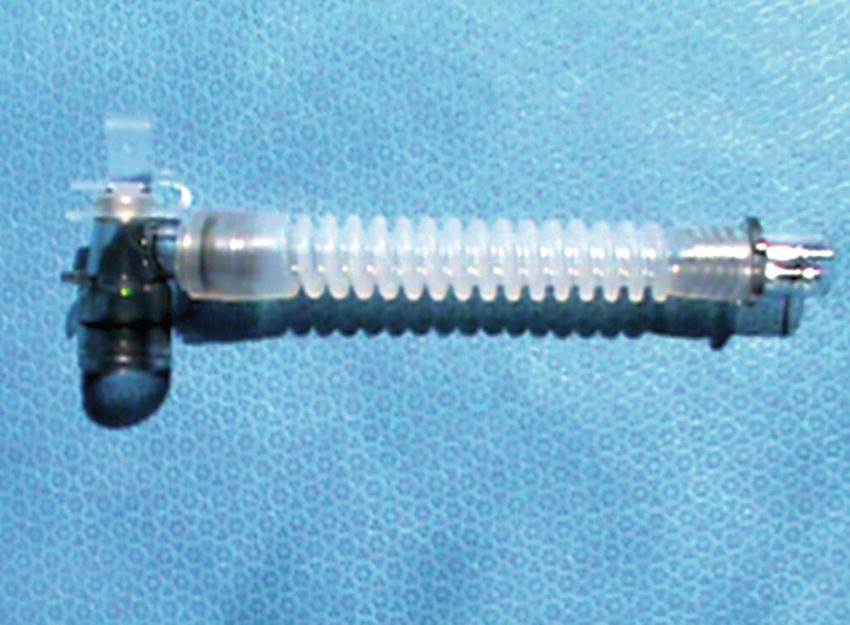

- EZ blocker: Y-shaped bronchial blocker with two distal extensions with a balloon to be placed in each mainstem bronchi (Fig. 39.32).

- Cohen: A catheter with a flexible tip with an angle of up to 90 degrees used to guide the device into the target bronchus.

- Coopdech: This has an angle at the distal end to aid in the appropriate placement of the balloon.

- Univent tube: An ETT with a second lumen through which an endobronchial blocker can be inserted and placed with the assistance of flexible bronchoscopy.

FIGURE 39.32. EZ-Blocker endobronchial blocker with distal inflated balloons (left) and proximal end with pilot balloons (right).

Review Questions

1. True or False: Nasal cannulas are only useful for patients who breathe through their nose.

A) True

B) False

Answer: B. False.Nasal cannulas are useful even in patients who breathe through their mouths. The air inhaled through the mouth may create a vacuum in the nasopharynx that enhances flow of oxygen through the nasal cannula into the airway. The mixing of oxygen from the nasal cannula and room air increases the FiO2 of the inspired gas.

2. Nasal cannulas and face masks can deliver equal amounts of FiO2.

A) True

B) False

Answer: B. False.Nasal cannulas are able to reach FiO2 in the range of 0.30-0.40. The FiO2 becomes less reliable at the high and low ends of the range. The FiO2 is limited by the significant mixing with room air that occurs from an open source of O2. Standard face masks can deliver FiO2 of 0.30-0.50. Compared to nasal cannulas, standard face masks have less mixing with room air and rebreathing.

3. In which scenario would a face tent or shovel mask would be most appropriate?

A) In a patient with a significant amount of airway secretions

B) In a patient in need of positive pressure ventilation

C) In a patient with a known airway obstruction

D) In a delirious/confused patient

Answer: D

A standard face mask would be more reliable for oxygen delivery. Compared to a face mask, which can cause some level of discomfort around the nose and mouth, a shovel mask would be more likely to be better tolerated by a delirious patient. Of the options listed, a shovel mask would provide supplemental oxygen with minimal discomfort around the face including the nose and mouth.

4. In which of the following situations should an endobronchial blocker be selected in lieu of a double-lumen endotracheal tube?

A) Differential ventilation of both lungs is needed.

B) Isolation of small lung segments is needed.

C) Only one lung needs ventilation.

D) There are significant changes to the anatomy of the left main bronchus.

Answer: B

Double-lumen endotracheal tubes are often used when differential ventilation of both lungs is needed, when only one lung needs ventilation, and when there are significant changes to the anatomy of the left main bronchus (in which case, a right DLT may be used). Isolation of smaller lung segments is the only scenario in which an endobronchial blocker placement is most appropriate, as double-lumen endotracheal tubes are unable to reliably isolate individual lung segments.

5. Which device is not used for lung isolation in anesthesia?

A) Double-lumen endotracheal tubes

B) Endotracheal adapters

C) Endobronchial tubes

D) Bronchial blockers

Answer: B

The endotracheal adapter is the only device listed unable to be used for lung isolation.

6. What are some differences between regular LMAs and intubating LMAs?

Discussion: Intubating LMAs are different than standard LMAs in that they are designed to optimize intubation in patients in which an LMA would be important to provide ventilation in the process of securing the airway with an endotracheal tube.

7. You are setting up for a facial surgery in which the anesthesiologist has requested a wire-reinforced endotracheal tube. Which of the following is not also important in your setup?

A) I don’t need to check to see if there is laser equipment present in the room; this tube is laser safe.

B) I don’t need to put out warm saline to soften this tube: although it is wire, it is not stiff.

C) I don’t need to put a stylet out: this tube’s wire will give its curve “memory” and allow shaping to help it reach the larynx.

D) I don’t need to put out a bite block: this tube is reinforced and cannot kink.

Answer: B

This tube is wire reinforced throughout, and the coils of the wire keep the lumen open. Neither its plastic nor wire gives it stiffness, and it is “floppy” along its length. It bends like a “slinky” and does not hold the standard shaped curve that a PVC tube does. It requires a stylet for placement. Although it will not kink under normal conditions, it can develop a permanent pinch under intense occlusive pressure, like biting, and requires a bite block. It is not laser or MRI safe.

8. Of the devices listed below, which device is designed to deliver a more predictable FiO2?

A) Nasal cannula

B) Face mask

C) Shovel mask

D) Venturi mask

Answer: D

Venturi masks are capable of delivering a more reliable FiO2 determined by the adapter utilized and the flow delivered from the oxygen source.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Baldini G, Hosur S, Butteworth JF, et al. Airway management. In: Butterworth JF, Mackey DC, Wasnick JD, eds. Morgan & Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2013:309-342.

Klock, PA, Andreson J, Hernandez M. Airway management. In: Longnecker DE, ed. Anesthesiology. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2018:498-532.

Newmark JL, Warren SS. Supraglottic airway devices. In: Sandberg W, Urman R, Ehrenfeld J, eds. The MGH Textbook of Anesthetic Equipment. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011

Waldau T, Larsen VH, Bonde J. Evaluation of five oxygen delivery devices in spontaneously breathing subjects by oxygraphy. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:256-263.