CHAPTER 31

ASA Standard Monitoring1

1Dr. Andrew Slupe contributed substantial material on cardiovascular monitoring to this chapter.

This chapter covers basic monitors required for patient safety during an anesthetic administration, as defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Standards for Basic Monitoring, and the role of the anesthesia technician in complying with these standards. The ASA standards were first approved in October 1986. The most recent update was completed in October 2015. Each of the five standards is discussed here.

Standard I is a general statement, with standards II through V being specific to the monitoring techniques that should be used to assess a patient’s oxygenation, ventilation, circulation, and body temperature. These monitors are discussed in roughly the same order as the standards they fulfill.

ASA Standard I

“Qualified anesthesia personnel shall be present in the room throughout the conduct of all general anesthetics, regional anesthetics, and monitored anesthesia care.” Of note, emergencies requiring the anesthesiologist’s absence are referred to his or her judgment, and circumstances involving hazard to the anesthesia provider (i.e., radiation) must involve provision for remote observation and monitoring of the patient.

Pulse Oximetry (ASA Standards II and IV)

Pulse oximetry is a noninvasive method used to determine oxygen levels in arterial blood. Similar to some gas analysis techniques, pulse oximetry is based on the principle that hemoglobin absorbs a specific wavelength of light differently whether it is saturated or desaturated with oxygen. Hemoglobin is a protein contained in red blood cells (RBCs). Each hemoglobin molecule is capable of binding four oxygen molecules. Although oxygen dissolves in the blood, binding oxygen to hemoglobin found in RBCs allows the blood to carry 70 times as much oxygen. In arterial blood, about 98.5% of the oxygen is bound to hemoglobin, and only 1.5% is dissolved within the blood. Hemoglobin that has bound oxygen is termed oxyhemoglobin, and hemoglobin that does not have oxygen bound to it is termed deoxyhemoglobin.

Technology

The technology of the pulse oximeter consists of a light-emitting diode (LED) light source and a light detector. The LED and detector are housed apart from one another in either a rigid or flexible support such that a portion of the patient’s tissue can be atraumatically placed between them.

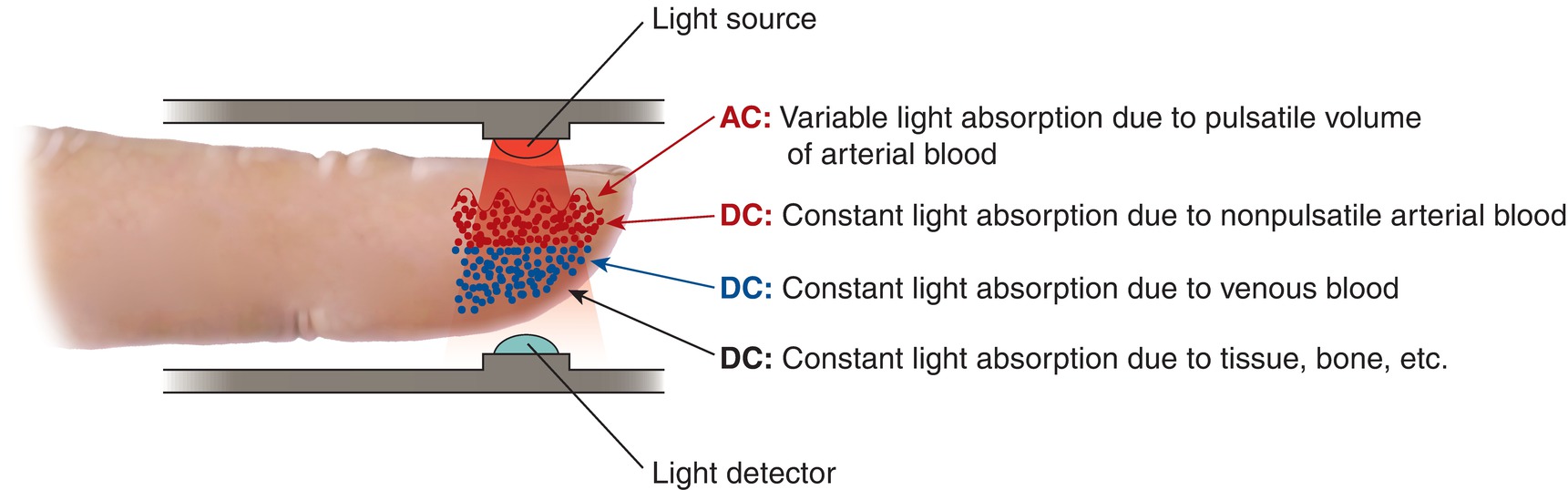

The LED produces light in the red to infrared spectrum at a wavelength of 660 nm. This light passes through the patient’s tissue, and a portion of this light is absorbed by hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying molecule in the blood, flowing through the tissue capillaries. Absorption of light by hemoglobin is dependent on the oxygen-bound state of the molecule. Oxygen-bound hemoglobin absorbs 940-nm wavelength light, whereas oxygen-free hemoglobin absorbs 660-nm wavelength light. This unique biophysical property of hemoglobin allows for determination of the amount of oxygen-bound hemoglobin. This is accomplished by measuring the difference between the light incident on a tissue and that transmitted through the tissue to the detector (Fig. 31.1).

FIGURE 31.1. Pulse oximeter technology.

The light detector is able to quantify the amount of light that is absorbed by oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin as it passes through the patient’s tissue. The amount of light absorbed is proportional to the concentration of oxygen-bound and oxygen-free hemoglobin. The tissue within the pulse oximeter consists of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and venous and arterial blood in the capillary bed, all of which absorb a static amount of the light passing through the tissue. With each heartbeat, a small amount of additional arterial blood enters the capillary. The pulsatile nature of this blood flow produces a time-dependent change in the amount of light absorbed in the tissue. This change is detected by the pulse oximeter.

Using the time-dependent change in light absorption by pulsatile arterial blood and a proprietary algorithm, the pulse oximeter calculates the oxygen saturation (SpO2) (see Chapter 5, Cardiovascular Monitoring, for a reminder on the relationship between oxygen saturation of hemoglobin and the actual amount of oxygen in the blood). The SpO2 is reported as a numerical percentage displayed by the monitor as well as an audible tone, the pitch of which is related to the value of the measured SpO2. The time-dependent tracing of the signal, the waveform, can be displayed as well. In addition to reporting SpO2, pulse oximeters report the frequency of blood pulsatility, which is reflective of the heart rate. An irregular heart rate rhythm is usually noticeable but diagnosis requires ECG.

There are many different types of pulse oximeter probes used in clinical practice. The choice of probe is dependent on the availability of the sites to monitor; this varies with the nature of the surgical procedure, patient-specific factors such as age and size, and anesthetist-specific preferences. Following placement, most pulse oximeter probes will average the data collected over approximately 5 seconds before beginning to report values.

There are two types of pulse oximeter probes: transmission and reflection. Transmission probes were the first to be developed and remain the most common. Transmission probes have the light source on one side, with the detector directly opposite. Light from the source is transmitted through the tissues of interest to the detector, and the amount of light that reaches the detector is used for calculations. Transmission sensors can be placed anywhere near the light source, and the detector can be positioned on opposite sides of a pulsatile blood flow. Care must be taken when placing sensors, as both accuracy and stability depend on the transmitter and detector being directly opposite to each other. This is especially true for co-oximetry probes. Common sensor sites include the fingertip, toe, nose, and earlobe for children and adults and foot and forearm for neonates. Less common sites include the cheek for adults and the penis for neonates.

Reflection probes have both a light source and a detector placed near one another. The amount of light reflected to the sensor is used for calculations. The forehead is the most common site for reflectance sensors.

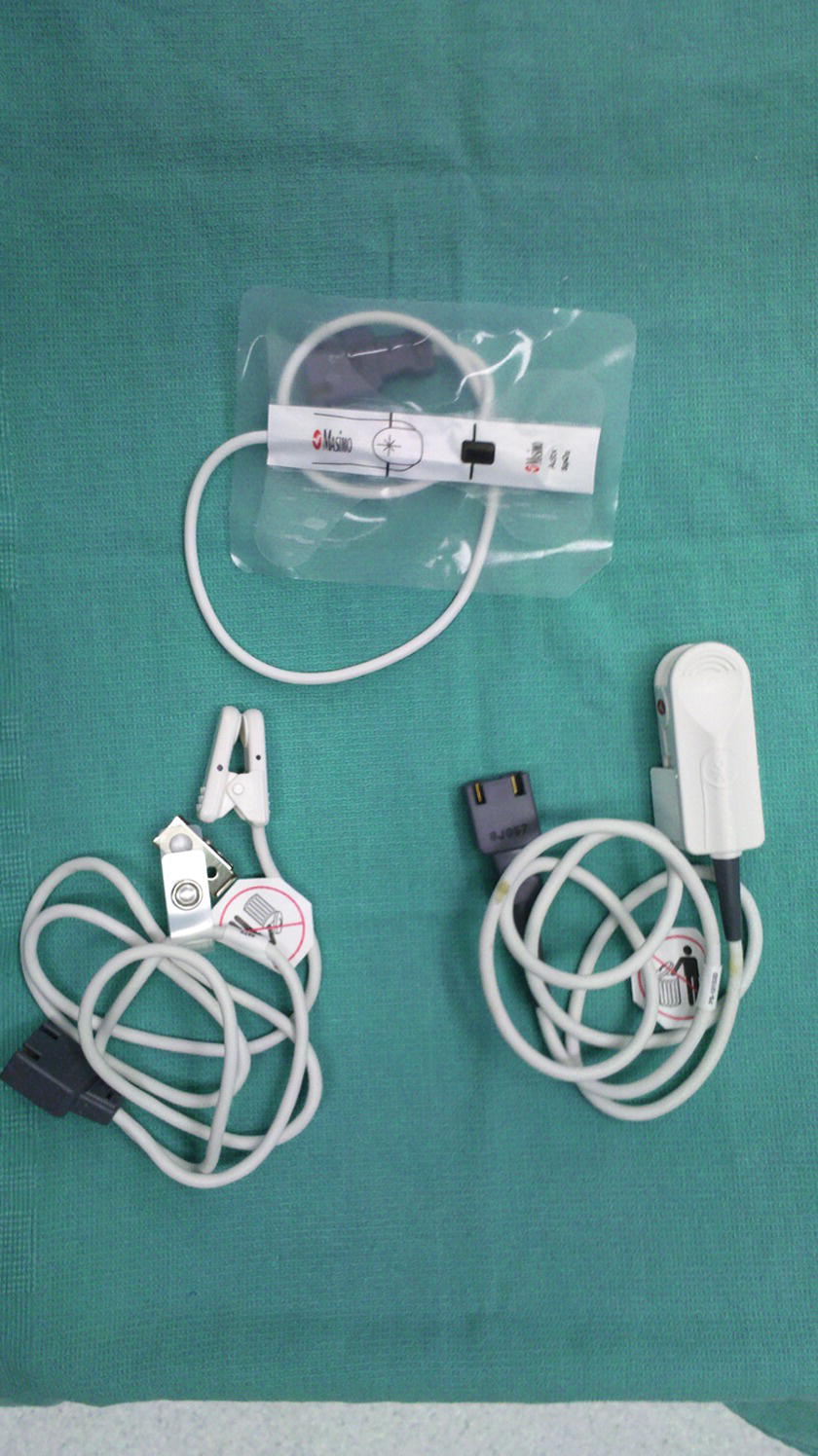

Pulse oximeter probes can be either disposable or reusable (Fig. 31.2). Reusable probes are classified as “noncritical” items for disinfection purposes, and low-level disinfection between patients is suitable as long as the probe is placed over an intact skin or does not become soiled with blood or body fluids. Any reusable probe that does become soiled should be treated with high-level disinfection or sterilization. Regardless of the treatment used, make sure the probe has dried completely before using it on the next patient.

FIGURE 31.2. Reusable and disposable pulse oximetry probes.

Sources of Error

Environmental light can be detected by the pulse oximeter and interfere with accurate measurements of SpO2. Usually this effect is minimal, as it lacks intensity in the critical red spectrum (600-900 nm). High-amplitude infrared light, such as that produced by stereotactic neurosurgical systems, can occasionally cause interference. It may even pass through fabric and require an opaque barrier-like aluminum foil to permit the pulse oximeter to function.

Light-absorbing material, such as dirt or nail polish, on the patient’s body part that the pulse oximeter is on can also be a source of interference. This can be overcome by removing the contaminant, moving the probe, or changing the orientation of the probe side to side, such that the light does not pass through the nail polish. Usually, only blue, purple, black, and metallic nail polishes cause difficulty.

Pulsatile blood flow through tissue capillaries is required for functioning of the pulse oximeter. Conditions that prevent pulsatile blood flow will negate the use of a pulse oximeter to monitor blood-oxygen saturation. Such conditions include continuous mechanical support devices, such as a left ventricular assist device, which ablate pulsatility; lack of adequate pulsatility due to reduced cardiac output; occlusion of the artery upstream of the capillary bed being monitored (most commonly by a blood pressure cuff); or vasoconstriction, which prevents blood flow into peripheral capillaries. Severe shock can cause loss of pulse oximeter signal, and return of the pulse oximeter signal may be the first sign that cardiac output or perfusion is recovering. Conversely, pulse oximeter algorithms are not 100% reliable in bradycardias, and a heart rate signal may not vanish immediately during cardiac arrest.

Several substances alter the ability of Hgb to bind oxygen and affect pulse oximetry readings. Carbon monoxide binds to Hgb 20 times more strongly than oxygen. The presence of carbon monoxide effectively lowers the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood (available amount of Hgb to carry oxygen). In addition, carbon monoxide bound to Hgb (carboxyhemoglobin) absorbs one of the wavelengths of light used by the pulse oximeter and interferes with the calculation of oxygen saturation. Therefore, patients with high carboxyhemoglobin levels may not have enough oxyhemoglobin yet still have high pulse oximetry readings. Other forms of Hgb, including methemoglobin and sulfhemoglobin, also interfere with both the ability of oxygen to bind to Hgb and pulse oximetry readings. Patients with methemoglobinemia typically have pulse oximetry readings of 85% despite severe reductions in oxygen-carrying capacity.

A co-oximeter may be used to overcome some of these limitations of standard pulse oximeters. Co-oximeters use multiple wavelengths of light (as many as eight) and can not only measure oxyhemoglobin but also provide values for other states of Hgb, such as carboxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, and sulfhemoglobin, as well as the total amount of Hgb. Co-oximeters are commonly available with blood gas machines; however, pulse co-oximeters are available for bedside use as well. As an anesthesia technician, you should know the limitations of your pulse oximeter and blood gas machine in the presence of these hemoglobin contaminants.

The algorithm used to calculate SpO2 from the difference in light absorption monitored by the pulse oximeter was developed using healthy volunteers. These healthy volunteers were not subject to low oxygenation states. As such, the reliable range of the detector is for oxygen saturation levels of 100% to approximately 70%. Below this level, the pulse oximeter report of oxygen saturation is not as accurate.

Finally, dislodgement of the pulse oximeter is frequent, particularly during positioning and transport. This causes frequent artifact but also leads to alarm fatigue, as providers may assume that a poor oxygen saturation reading is due to malposition. Pulse oximeters can also injure extremities during transfers.

Capnography (ASA Standard III)

Capnography is the measurement of carbon dioxide gas in the breathing system, with the measurements displayed in both numerical and graphic forms. The basic technology and related troubleshooting have been discussed in Chapter 30, Gas Analyzers. The role of capnography within the ASA standards is to help ensure a patient is adequately ventilated during all anesthetics. Continuous readings of exhaled carbon dioxide (CO2) are consistently validated as the best real-time monitors of ventilation and also contain information about cardiac output, metabolism, airway obstruction, and the anesthesia machine.

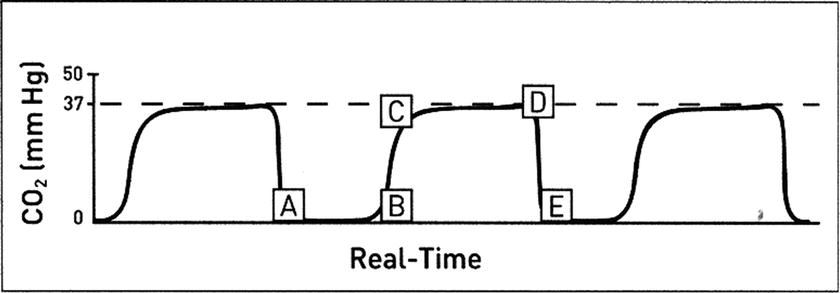

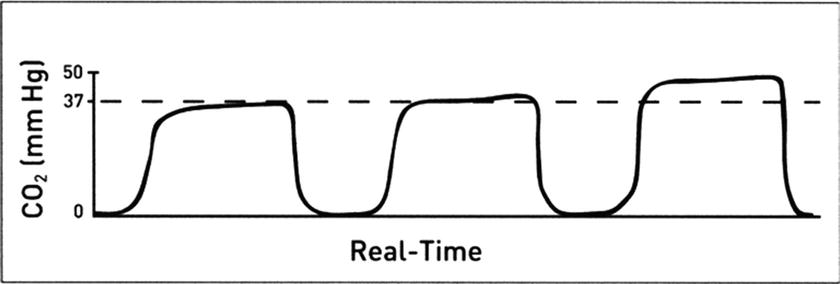

The “normal” capnogram in closed-circuit ventilation of a patient under general anesthesia is a waveform that represents the varying CO2 level throughout the breath cycle over time (Fig. 31.3A-E).

FIGURE 31.3. Normal capnogram. A, B: Baseline represents continued inhalation (value should be zero) or lack of gas movement. B, C: Expiratory upstroke (sharp rise from baseline represents the beginning of exhalation and consists of a mixture of air and alveolar gas. C, D: Expiratory plateau (continued exhalation of alveolar gas should be straight or nearly straight). D: End-tidal concentration (value at the end of exhalation). D, E: Inspiration begins (sharp downstroke as fresh gas is inspired). (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

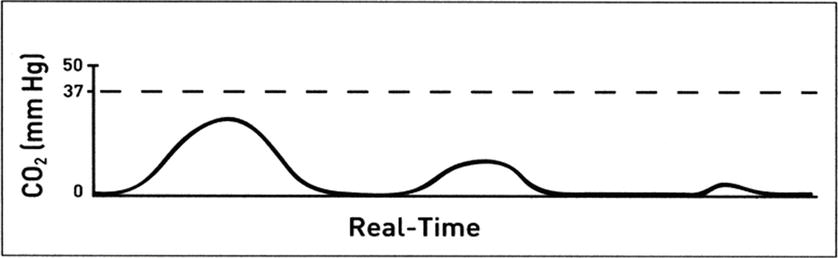

Measured exhaled CO2 is a function of CO2 production by the body, delivery of the CO2-containing blood to the lungs, gas exchange in the alveoli, and ventilation of the lungs to pick up CO2 from the alveoli and eliminate it outside the body. One of the most important functions of CO2 monitoring is to confirm the placement of an endotracheal tube into the trachea. If the tube is placed in the trachea and the patient is ventilated, and there is gas exchange between the blood and the alveoli, and there is cardiac output to deliver CO2 to the lungs, the CO2 monitor will register CO2. If the endotracheal tube is placed in the esophagus, the CO2 monitor will not register sustained CO2 (Fig. 31.4). Although there may be some carbon dioxide in the esophagus and stomach, the concentration is normally low and will rapidly be depleted within a few breaths of ventilation of the stomach. A capnograph is very reliable in detecting esophageal intubation; an esophageal intubation that is unrecognized can be fatal. Thus, it is essential that every anesthetic begin with a working capnograph.

FIGURE 31.4. ETCO2 levels rapidly diminish or are not present with an esophageal intubation. (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

Below is a discussion of the differential diagnosis of changes in measured CO2 values or waveforms. The shape of the waveform during a general anesthetic yields diagnostic information about how a patient is being ventilated.

Increased CO 2 : An increase in the level of end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) from previous levels can result from either an increase in the patient’s production of CO2 or a decrease in ventilation (Fig. 31.5):

FIGURE 31.5. Rising ETCO2 levels as detected on a capnogram. (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

- Increased metabolic rate (rising body temperature from blankets or external warming devices, thyrotoxicosis, malignant hyperthermia, etc.)

- Increased cardiac output

- Chemicals or metabolic products that have been administered to the patient that are converted to CO2 (bicarbonate, lactate, increased CO2 from laparoscopy [normal], CO2 from pathologic gas embolus, etc.)

- Decreased respiratory rate or tidal volume

- Impaired CO2 gas exchange (pulmonary failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], bronchospasm, etc.)

- Machine problems leading to decreased ventilation (leaks, obstructions, depleted CO2 absorber, etc.)

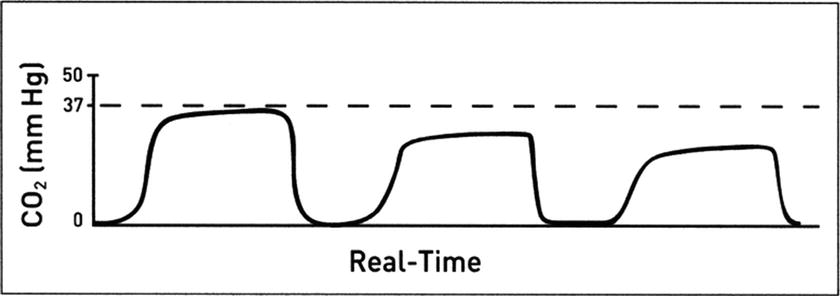

Decreased CO 2 : A decrease in the level of ETCO2 from previous levels can result from a change in the body’s production of CO2 (rare), the delivery of CO2 to the lungs, or an increase in ventilation (Fig. 31.6):

FIGURE 31.6. Diminishing ETCO2 levels as detected on a capnogram. (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

- Decreased metabolic rate or decreased core body temperature

- Decreased cardiac output

- Decreased pulmonary blood flow (pulmonary embolus)

- Increased tidal volume or respiratory rate

- Partial disconnect or crack in CO2-monitoring tubing

No CO 2 : A numerical reading of 0 or a flat waveform at 0 can indicate that CO2 is not being delivered to the monitor or a monitor malfunction. CO2 may not be delivered to the monitor/sensor under the following critical conditions:

- Circuit disconnect or sample line disconnect

- Apnea

- Cardiac arrest

- Total obstruction of the endotracheal tube, airway, or breathing circuit

- Total obstruction of gas sampling (sample port, sample line, water trap)

- Monitor malfunction

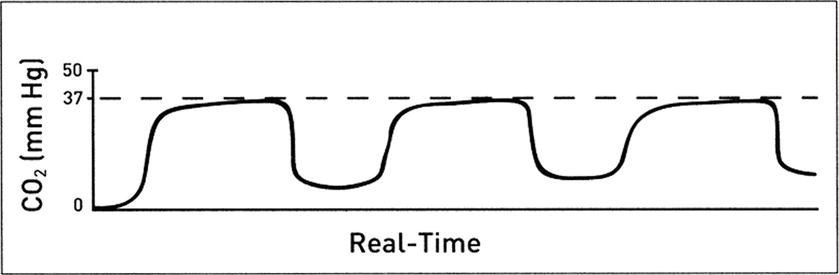

Abnormal baseline CO 2: Mechanical or anesthesia machine problems can often be a source of abnormal baseline CO2 readings (Fig. 31.7). Elevation of the baseline indicates rebreathing of CO2, which may also result in an increase in ETCO2. Possible causes include:

FIGURE 31.7. Elevated baseline CO2 levels as detected on a capnogram typical of rebreathing. (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

- Faulty expiratory valve on ventilator or anesthesia machine

- Inadequate inspiratory flow

- Exhausted CO2 absorbent

- Partial rebreathing

- Insufficient expiratory time

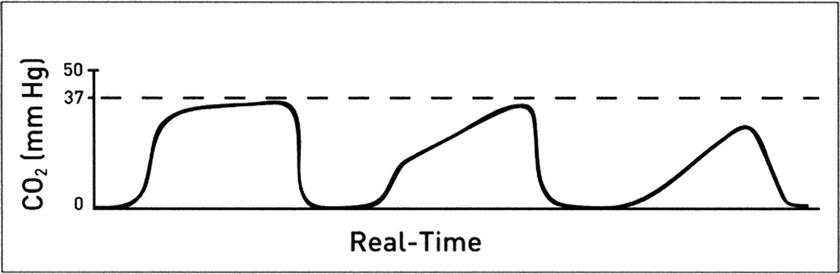

Changes in the shape of the CO 2 waveform: An obstruction to expiratory gas flow or differential emptying of obstructed small airways can present as a change in the slope of the expiratory upstroke of the capnogram (Fig. 31.8). The obstruction can be so severe that the CO2 wave never reaches a flat plateau before inhalation begins. Diagnoses to consider include:

FIGURE 31.8. ETCO2 waveform does not reach a plateau typical of bronchospasm or small airway obstruction. Electrocardiogram lead color codes. (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

- Obstruction in the expiratory limb of the breathing circuit

- Presence of a foreign body in the upper airway

- Partially kinked or occluded endotracheal tube or supraglottic airway

- Bronchospasm

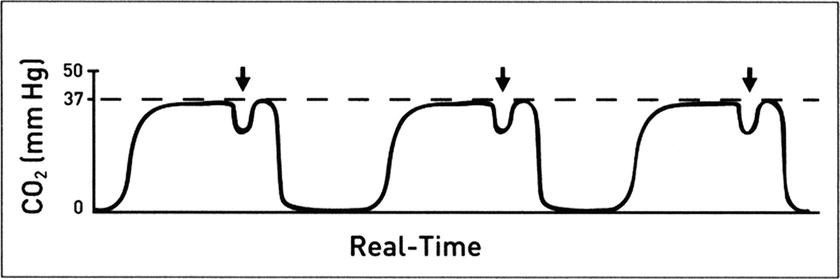

The “curare cleft” is seen in the plateau portion of the waveform. It is a small initiation of inspiratory flow during expiration and an indication that muscle relaxants are wearing off and the patient is making efforts to return to spontaneous ventilation (Fig. 31.9).

FIGURE 31.9. A “cleft” in the ETCO2 plateau. (Adapted from Capnography Self-Study Guide. Rev. 1. Smiths Medical; 2008, used with permission.)

During all administration of anesthetics, even regional anesthesia or local anesthesia, patients must be monitored with ongoing observation of ventilation. Capnography has been shown repeatedly to be better than observation alone as a monitor of ventilation in sedated patients. As of 2011, capnography is required by ASA standards during monitored anesthesia care for moderate or deep sedation, just as it is during general anesthesia. The same sidestream gas analyzer is used for measurement, though smaller portable versions may be more convenient, particularly in out-of-OR settings where an anesthesia machine is not otherwise needed. Monitoring is done via aspiration of gas from a simple face mask or a nasal cannula, many of which are now designed for this purpose.

Finally, ventilation with a mechanical ventilator must also be monitored with disconnect alarms, which are part of the design of all anesthesia machines.

Electrocardiogram (ASA Standard IV—Circulation)

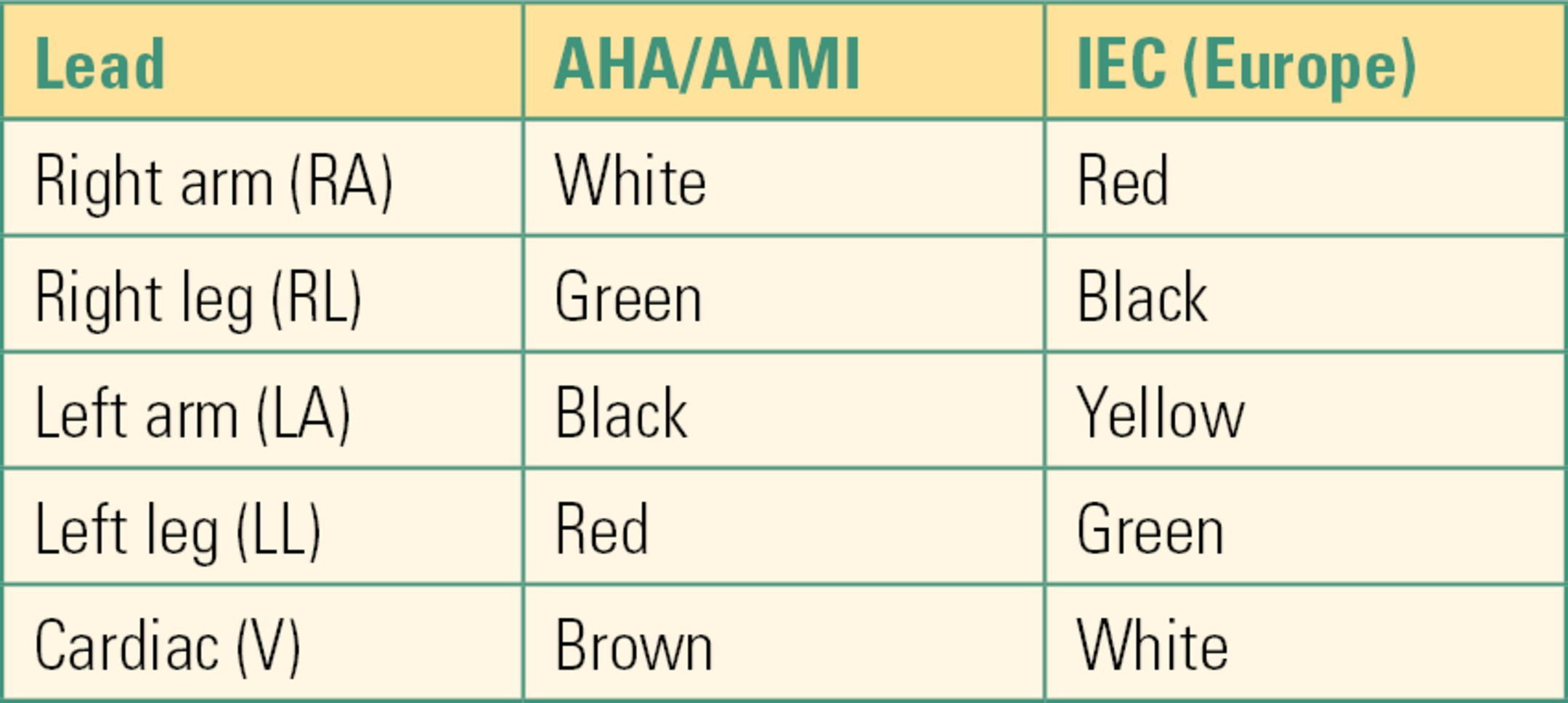

The electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) is a record of the electrical activity of the heart over time. Its physiology is summarized in Chapter 5, Cardiovascular Monitoring. Although a “12-lead” ECG is traditionally used for diagnostic purposes, most anesthesia and critical care monitoring is accomplished using either a three-wire harness or a five-wire harness. The term ECG lead can mean different things to different people, often with confusing results. When people mention an ECG lead, it could mean the specific tracing, a specific wire on the ECG harness, or the adhesive electrode that attaches to the skin. To avoid confusion, we use the term leads to mean the specific tracings, lead wires to refer to the harness that connects from the monitor to the adhesive pads, and electrodes to refer to the adhesive pads that attach the lead wires to the skin. ECG lead wires are placed on patients in standard patterns. There are two primary color-coding systems used throughout the world: American Hospital Association/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AHA/AAMI) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). The AHA/AAMI colors are used in North America, while IEC colors are used throughout Europe. Other countries around the world vary in which standard they follow. Standard nomenclature is as follows: RA for right arm, RL for right leg, LA for left arm, LL for left leg, and V for any of the six cardiac lead positions. The standards are compared in Table 31.1.

Table 31.1. ECG Lead Wire Color Codes

A three-wire harness is the most basic of ECG monitoring systems. The ECG display is limited to leads I, II, and III. Rhythm monitoring is excellent. ST-segment monitoring for cardiac ischemia can be done but is limited without a V lead. Thus, the three-lead harness is typically used in situations where risk of cardiac ischemia is low. The standard three-lead harness consists of RA, LA, and LL, although some monitors may use RA, LA, and RL.

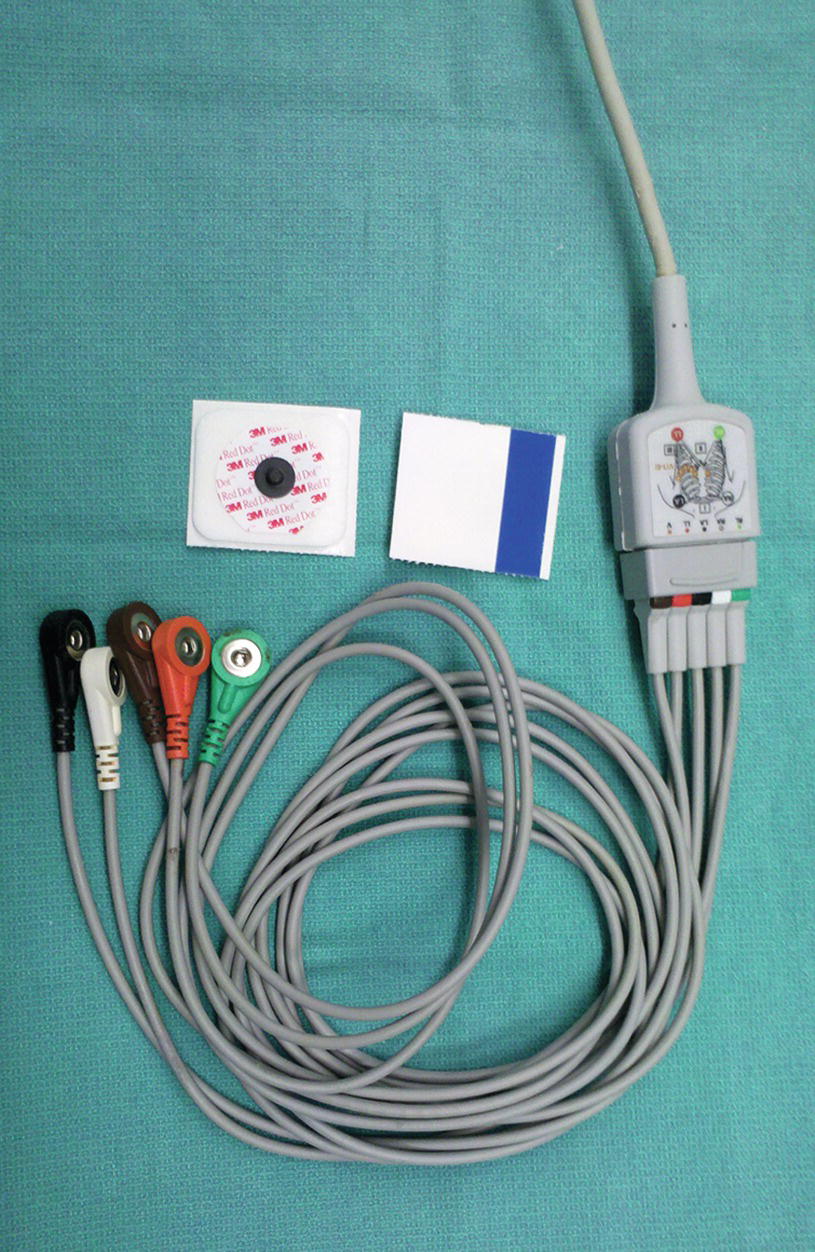

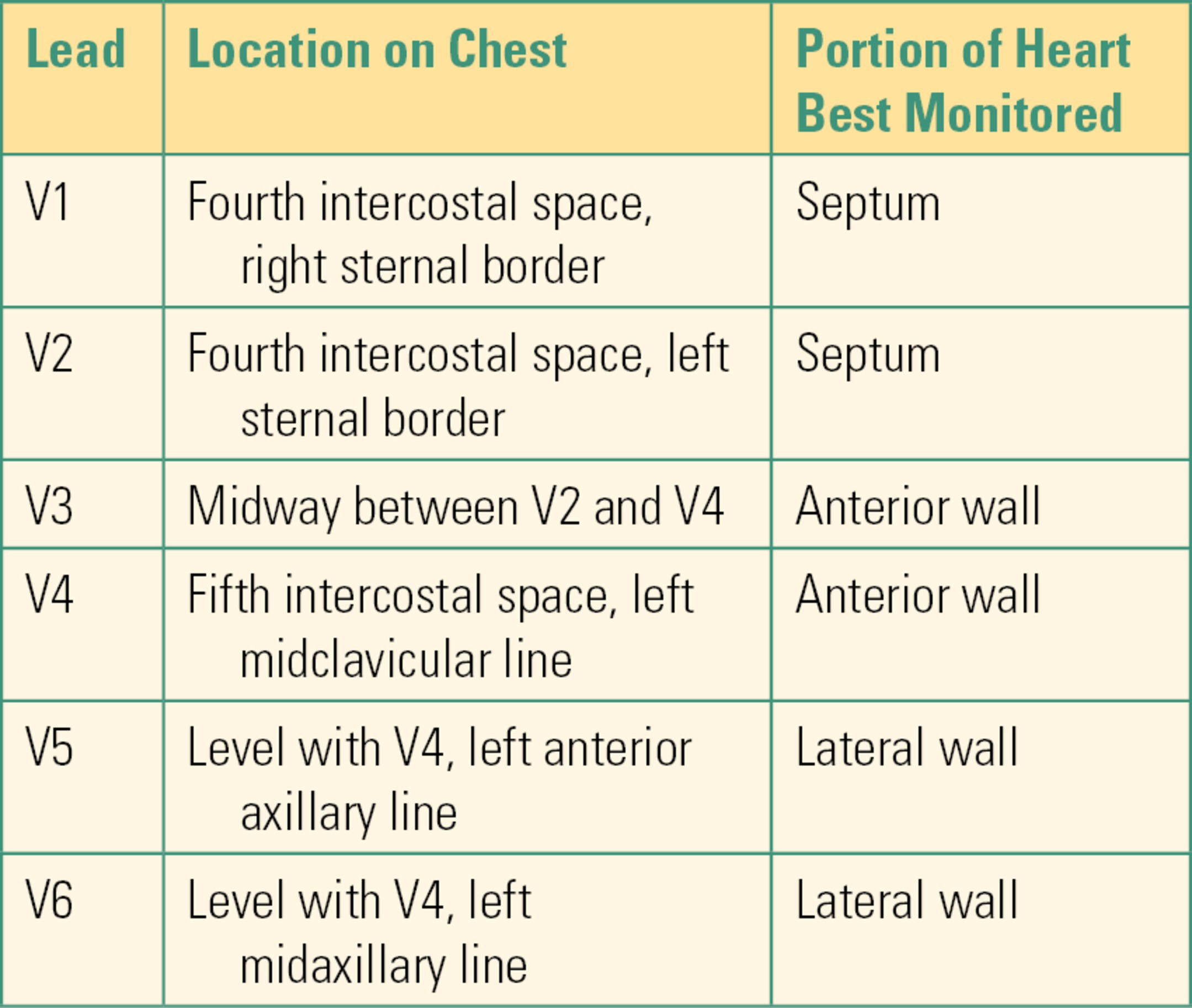

A five-wire harness provides significant improvement in monitoring and diagnostic capabilities (Fig. 31.10). The addition of a ground lead (RL) and the cardiac leads (V1-V6) allows most modern monitors to display and print up to eight leads simultaneously. ST-segment and arrhythmia analysis is also improved with the additional leads. When placing the V lead wire on a patient, it can be in any one of six positions, V1-V6 (Table 31.2).

FIGURE 31.10. Five-lead wire system with harness and electrodes.

Table 31.2. Possible Locations of V Lead

The most common V lead wire positions used in critical care units are V1 and V2. The most common V lead wire position used by anesthesia technician is V5. Remember that the position of the lead wires is used to measure electrical forces from particular regions of the heart. No matter which ECG monitoring harness is used, it is critical to place the lead wires in the proper position. Improper positioning of the leads can lead to abnormal ECG signals and errors in interpretation.

Interference in the ECG signal usually stems from three primary sources: motion artifact, inadequate preparation and placement of the electrodes, and electronic interference. Movement of the lead wires can cause faulty electronic signals. Care should be taken that the lead wires are not being moved or in contact with moving or vibrating equipment. Even the respiratory movements of the chest can affect the ECG signal. Electronic interference is usually either 60 cycles (from faulty wiring) or excessive radio frequency (from electrocautery units). Options for minimizing electrical interference include changing the circuit the monitor is plugged into or adjusting the ECG filter on the monitor (although this can reduce diagnostic quality). Make sure cables and lead wires do not have breaks in insulating materials. Extreme instances may require the use of a power conditioner.

Correct skin preparation and lead placement are the key to obtaining quality ECG tracings. The signals received through the electrodes are relatively weak and can easily be obscured by impulses from other sources. In order to enhance the ECG signal quality and reduce artifact:

- Make sure the electrode gel has not dried out.

- Shave or clip any excess hair.

- Gently abrade the skin where the electrode will be placed (many electrodes have an abrasive area on the cover).

- Wipe the area with an alcohol pad to remove skin oils.

- Any EKG lead wire that needs to be relocated probably needs to have a fresh electrode pad placed to ensure proper contact.

- A functional printer is a critical component of ECG monitoring. Many dysrhythmias can only be diagnosed with careful measurements of intervals, which cannot be done on a monitor screen as it scrolls past. Printed strips are also necessary for subsequent management of intra-anesthetic rhythm problems.

Noninvasive Blood Pressure (ASA Standard IV)

The arterial walls are muscular and elastic in the absence of vascular disease. Blood flows through the arteries in a pulsatile fashion at a measurable pressure (see Chapters 4 and 5, Cardiovascular Anatomy and Physiology and Cardiovascular Monitoring). This flow pattern causes the arteries to alternately expand and contract, resulting in the pulse that we can feel with our fingertips.

Blood pressure is not constant throughout the arterial system. In general, systolic pressure increases and diastolic pressure decreases the further blood moves from the heart. This is due to increasing resistance (friction) that the blood encounters as it is forced through progressively narrower arteries. Changes in peripheral vascular resistance (vasoconstriction or vasodilation) can further alter these pressures. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) is not affected to the same degree, with a normal variation of only 1-2 mm Hg.

Several noninvasive technologies have been developed to measure these pulsations and translate them into the blood pressure readings we are familiar with. The most commonly used methods in the operating room are pulse detection, auscultation, and oscillation.

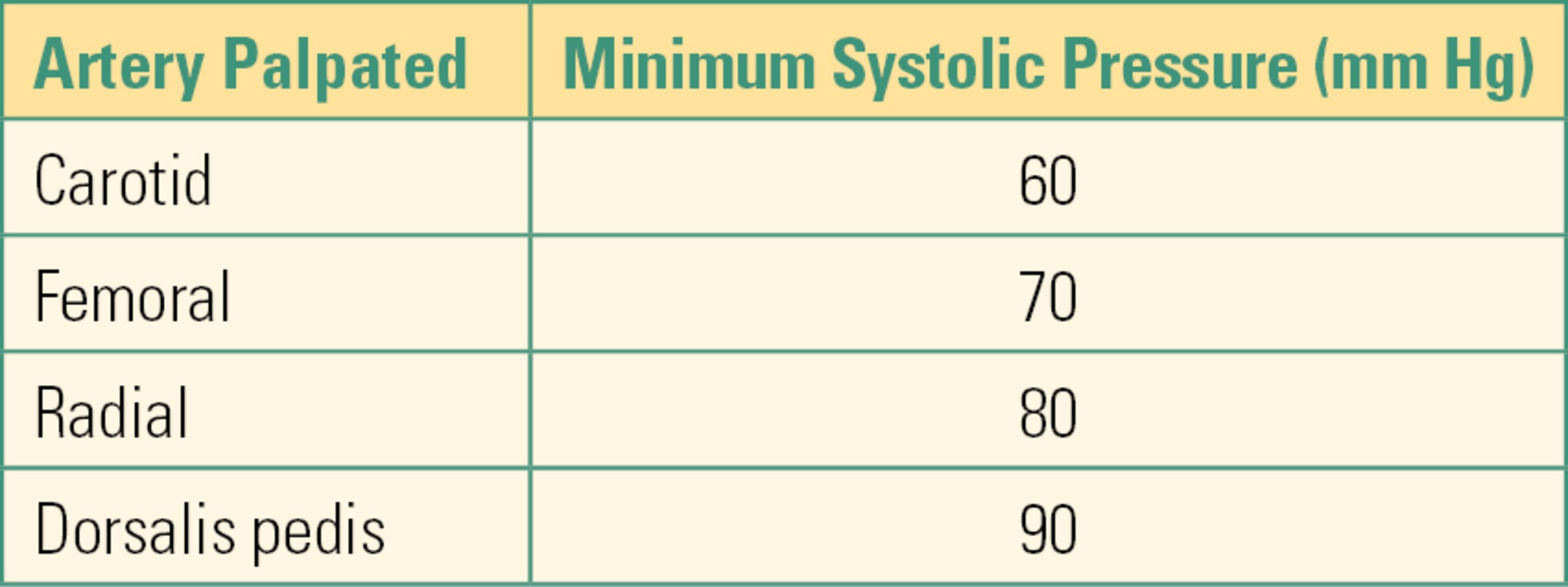

While awaiting a cuff or manometer reading, systolic pressure can be estimated by the location at which a pulse can be palpated, as shown in Table 31.3. For example, if you can only obtain a carotid pulse, then the systolic pressure is at least 60 mm Hg. Similarly, a radial pulse usually begins to be palpable at about 80 mm Hg. Whenever you are palpating a pulse, make sure to use only the tips of your index and middle fingers: the artery in your thumb is large enough that you can mistake your own pulse for that of the patient. Unfortunately, palpation of pulses to estimate blood pressure is unreliable even when performed by experienced providers.

Table 31.3. Systolic Pressure Estimates

Auscultation, or “listening,” adds a stethoscope to the cuff and manometer and is the most common manual method of blood pressure determination. Dr. Nikolai Korotkoff developed this technique and described five distinct sounds that can be heard as a cuff is deflated over an occluded artery. These sounds result from the turbulent return of blood flow in the artery. The limitation of this method is dependence on proper technique and the differences in audio and visual acuity among clinicians. Despite these limitations, a cuff, manometer, and stethoscope should be readily available as a backup for automated systems. As an anesthesia technician, you may need to obtain this backup equipment promptly should a monitor fail.

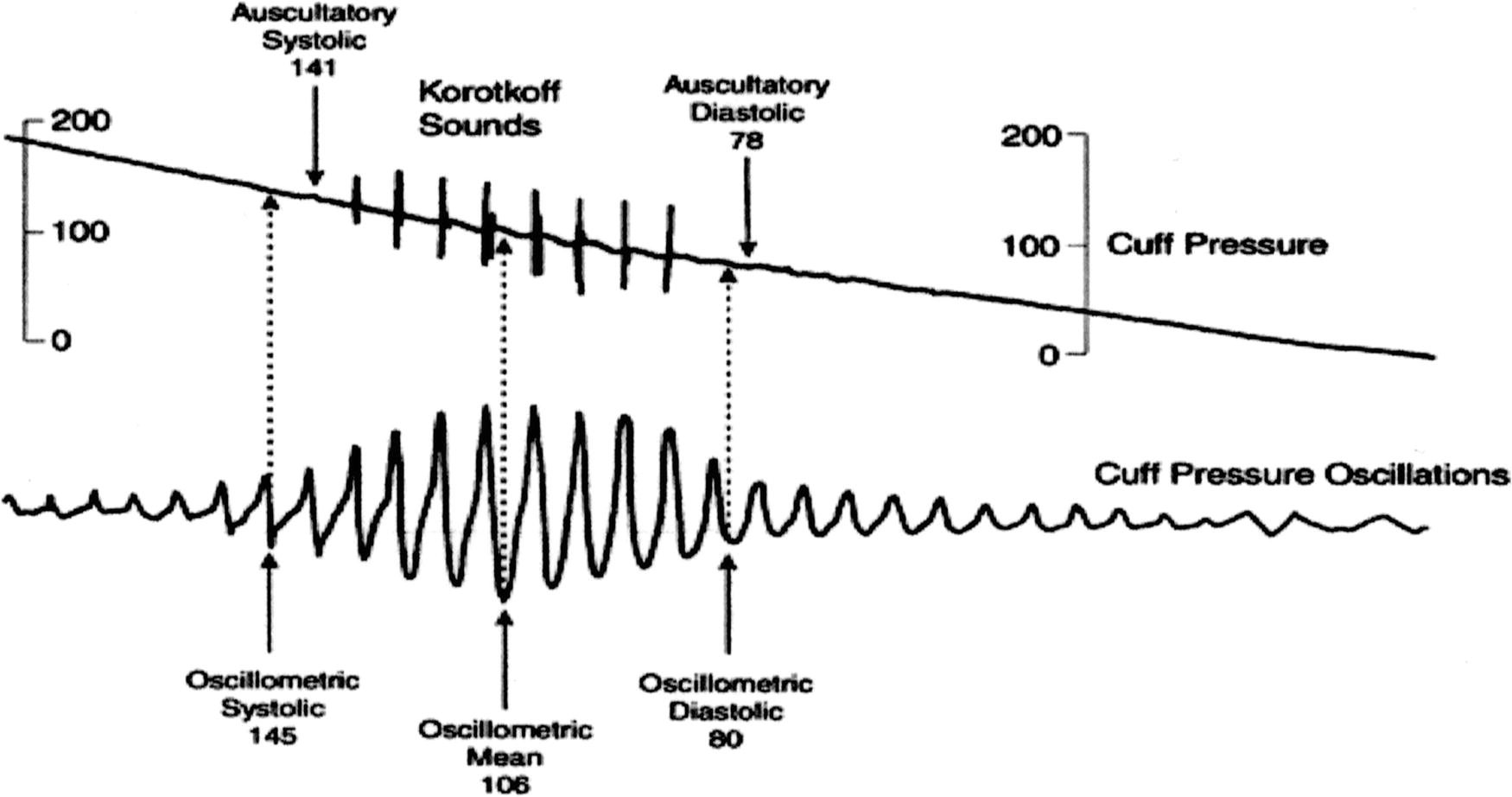

The oscillatory technique is used by the majority of anesthesia and critical care automatic blood pressure monitors. Although oscillometers still rely on the turbulent flow resulting from partial cuff compression, the form of energy measured (pressure vs sound) differs from auscultation. Arterial pulsations create pressure variations (oscillations) that are transferred from the cuff to pressure transducers inside the monitor. These pressure fluctuations, along with their amplitude, are used to calculate the pressures displayed. Although there is variation among manufacturers, systolic pressures are normally derived from the first significant oscillation detected, while diastolic pressures are calculated from the last. MAP is measured at the peak amplitude measured. Unlike auscultation techniques, oscillometers may have difficulty providing accurate readings in patients with arrhythmias, pulsus paradoxus, or extreme bradycardia.

Most automatic oscillometers include a rapid determination, or STAT mode. These modes cycle the monitor continuously to provide frequent readings but sacrifice accuracy in the process. Despite manufacturers’ claims, when in STAT mode, you should only accept MAP readings (as a trend rather than as an absolute figure) after the first few minutes, as vascular congestion caused by continual, repeated cuff inflation makes systolic and diastolic readings less reliable. STAT modes should be reserved for emergent situations and used for the shortest possible amount of time.

ASA guidelines recommend that the time interval between repeated measurements be no longer than 5 minutes while the delivery of anesthesia or sedation occurs. Some providers prefer a shorter interval such as 3 minutes. In general, should the interval need to be less than 3 minutes for a prolonged period of time, continuous blood pressure measurement through placement use of invasive blood pressure monitoring is indicated.

The difference between auscultation and oscillation measurements is demonstrated in Figure 31.11.

FIGURE 31.11. Simultaneous display of blood pressure cuff oscillations and auscultated blood pressure sounds.

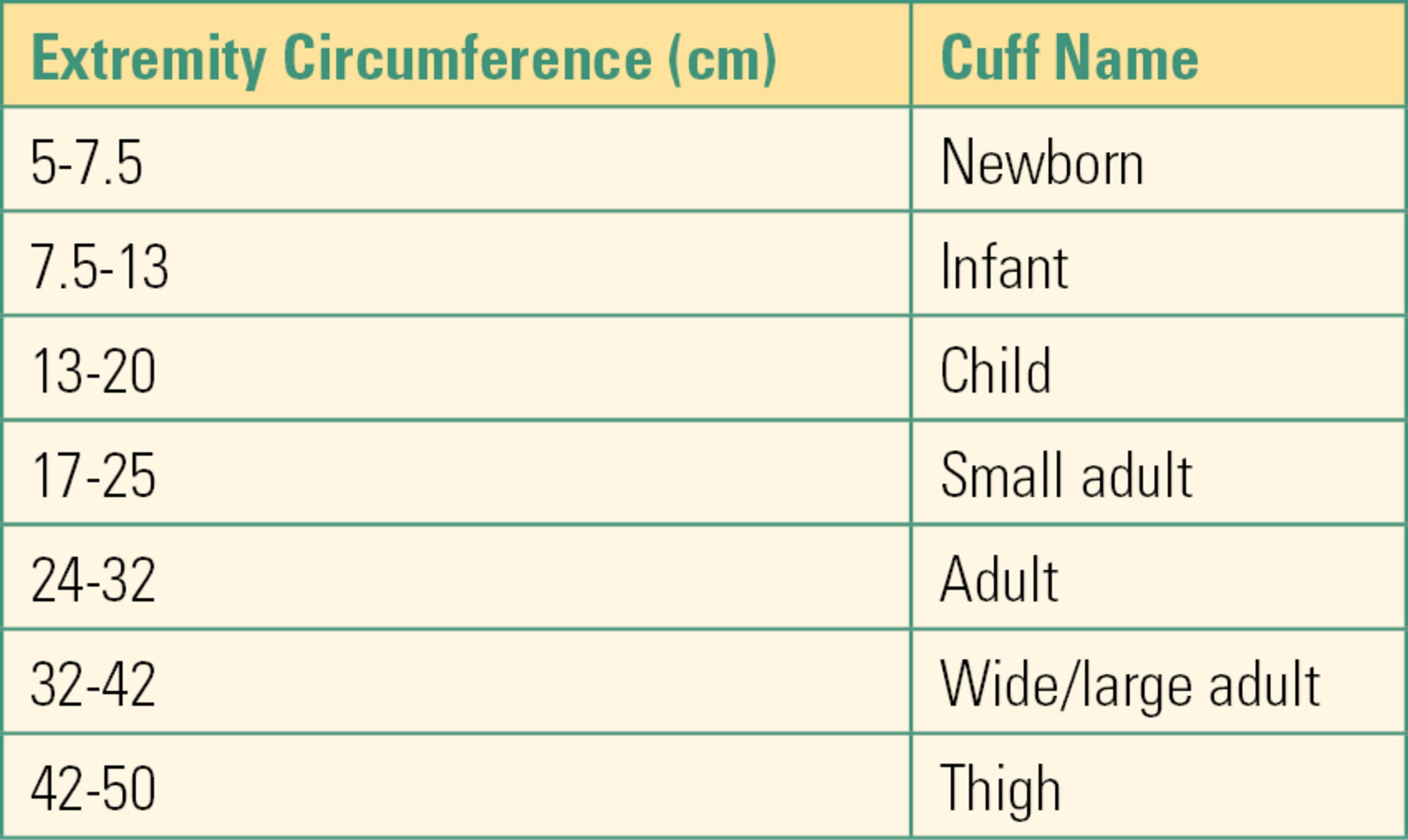

These technologies all rely on the use of a blood pressure cuff. A blood pressure cuff is basically an inflatable bladder encased in a sleeve that is wrapped circumferentially around an arm or leg. The accuracy of readings obtained is dependent on the selection of the correct cuff size. An appropriately sized cuff should have a bladder width approximately 40% the circumference of the limb being measured. The American Heart Association (AHA) size guidelines are summarized in Table 31.4. It is critical to note that cuff sizes are designated based on the size of the internal bladder, not the external sleeve, and that appropriate sizing is based on width, not length. A cuff that is labeled “long” is not the same as one labeled “large.” A long cuff has extra sleeve material to wrap around the limb, but the bladder dimensions remain the same as a regular cuff of the same size. Using the correct cuff size is essential for accurate readings. A cuff that is too small will result in false high readings, and one that is too large will result in false low readings. Most manufacturers include a printed index range on the sleeve as a visual confirmation of cuff size, making it easier to avoid size errors. Proper cuff placement is also critical for accurate readings. In general, proper placement is approximately 1 inch above the elbow for an arm cuff, 5 inch below the elbow when using the forearm, and just below the groin fold for a thigh cuff. Most manufacturers include an “artery” marker in the center of the bladder. Placing this marker directly over the artery to be occluded results in even compression of the artery and helps limit artifact.

Table 31.4. AHA Blood Pressure Cuff Size Recommendations

Blood pressure cuffs can be either disposable or reusable. Reusable cuffs are classified as “noncritical” items for disinfection purposes, and low-level disinfection between patients is suitable as long as the cuff is placed over an intact skin or does not become soiled with blood or body fluids. Any reusable cuff that does become soiled should be treated with high-level disinfection or sterilization. Regardless of the treatment used, make sure the cuff has dried completely before using it on the next patient.

Problems will usually present as an inability to obtain a reading. The basic troubleshooting questions to answer are as follows:

- Is the cuff the correct size?

- Is the cuff placed correctly?

- Are all connections tight?

- Is a member of the surgical team leaning against the cuff?

- Does the patient have excess muscle movement?

If this sequence does not solve the problem, consider replacing the blood pressure cuff first. If replacing the cuff does not solve the problem, replace the tubing that connects the cuff to the monitor. If you are still unable to obtain a pressure, the problem may be internal to the monitor or related to the physical status of the patient. Consider a different cuff location, monitor, or technique. The brachial artery in the upper arm is the most common site of blood pressure measurement. However, the femoral or popliteal arteries of the lower limb or the radial artery of the forearm can also be used, with an appropriate size cuff.

Temperature (ASA Standard V)

Temperature monitoring is key to the concept of temperature management. Consequences of unintended hypothermia can include increased oxygen demand, myocardial ischemia, platelet dysfunction, impaired renal function, delayed wound healing, and increased infection and mortality rates. Unintended hyperthermia can result in multiorgan failure. Temperature management is covered fully in Chapter 33. Temperature is normally expressed in degrees Celsius (C) rather than Fahrenheit (F) in anesthesia and critical care settings. Most monitors allow temperature to be displayed in either format, but the following formulas can be used to covert from one format to another: C = F − 32 × 5/9 and F = C × 9/5 + 32.

Like arterial blood pressure, temperature is not constant throughout the body. For example, a core temperature of 36°C can result in temperature site readings of oral 35.8°C, rectal 36.5°C, axillary 34.5°C, and skin surface 33°C. Because of this, monitors should be labeled with temperature site whenever possible. Common monitoring sites for anesthesia include nasopharyngeal, esophageal, rectal, bladder, tympanic membrane, pulmonary artery (PA) catheter, and skin. Less common sites are oral, axillary, and vaginal. The most reliable site for monitoring core temperature is via the PA catheter.

Most temperature monitoring is achieved using electronic and liquid crystal technologies. Electronic methods rely on either a thermistor “400-series” probe or a thermocouple “700-series” probe. Thermocouple probes are more accurate, but more expensive, so they are usually purchased when a reusable probe is used. Thermistor probes are less accurate, but significantly less expensive, and are normally purchased when disposable probes are used. Although most modern patient monitors are designed to work with either 400-series or 700-series probes, you may encounter some that only work with one or the other. Monitors that work with either series will have a switch that is used to select the correct type. Liquid crystal technology is used for disposable skin sensors. Skin temperature is a poor surrogate for core temperature, and these have limited applications.

Temperature probes can be either disposable or reusable. Reusable probes are classified as “semicritical” items for disinfection purposes, and high-level disinfection between patients is suitable as long as the probe does not become soiled with blood or body fluids. Any reusable probe that does become soiled should be treated with high-level disinfection or sterilization. Regardless of the treatment used, make sure the probe has dried completely before using it on the next patient.

Troubleshooting for temperature monitors is usually straightforward. If you have either no reading or an erratic reading, check the following to solve the problem:

- Is the monitor correctly set for the series of probe being used? (400 or 700?)

- Are all connections tight?

- Is there an electronic short or frayed wiring?

If checking these does not solve the problem, replace the probe/sensor. If replacing the sensor does not resolve the issue, replace the cable that connects the probe to the monitor. If that does not resolve the problem, consider an internal fault in the monitor. A spare module or stand-alone temperature monitor should be readily available for these needs.

Summary

The standard statement closes by noting that the anesthesiologist may waive required standard monitors under extenuating circumstances. The ASA notes that the anesthesiologist may even need to leave the room, in an emergency, weighing carefully how to best care for the needs of every patient. The ASA recommends, however, that if any ASA standard monitoring is not done, it should be documented, with the reasons, in the medical record. The anesthesia technician should understand the importance of each of the standard monitors, their implementation, and their troubleshooting, so that every patient receives optimal care.

Review Questions

1. You are called into the operating room (OR) and told that the pulse oximeter is broken. You look at the monitor and see that the reading is lower than expected with little, if any, waveform present. Which of the following is unlikely to be causing the problem?

A) Cold body part

B) Vasospasm

C) Reduced cardiac output

D) Broken pulse oximeter

E) Overinflation of blood pressure cuff proximal to pulse oximeter

Answer: D

A broken pulse oximeter, or one which has fallen off, is a frequent problem, but other problems must be ruled out as well. Alarm fatigue is a frequent problem with pulse oximetry. A pulse oximeter which needs to be replaced is an unlikely cause of a poor, nonpulsatile waveform. Poor perfusion to the extremity is the most likely cause of a poor, nonpulsatile waveform. All these could be causes of poor perfusion.

2. An elevation in the baseline of a CO2 monitor can be due to any of the following except

A) A faulty expiration valve on the ventilator

B) Cardiac arrest

C) Exhausted CO2 absorbent

D) Insufficient expiratory time

E) Inadequate fresh gas flow

Answer: B

All of the above can cause an elevation in the CO2 baseline with the exception of cardiac arrest, which results in a fall in ETCO2.

3. A three-lead EKG harness commonly consists of

A) RA (white), LA (black), V (brown)

B) RA (white), RL (green), LL (red)

C) RA (white), LA (black), LL (red)

D) RA (white), RL (green), V (brown)

E) None of the above

Answer: C

The RA, LA, and LL make up the common three-lead harness. The RL and V leads are added to make up the common five-lead harness.

4. Using a blood pressure cuff that is too small for the patient can result in false high readings.

A) True

B) False

Answer: A

Conversely, a blood pressure cuff that is too large for the patient can result in false low readings.

5. The most reliable site for monitoring core temperature is

A) Esophageal

B) Skin

C) Oral

D) PA

E) Nasopharyngeal

Answer: D

When measuring core temperature, the most reliable site is via the PA catheter.

SUGGESTED READINGS

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Standards for Basic Anesthesia Monitoring 2015. Available from: http://www.asahq.org/quality-and-practice-management/practice-guidance-resource-documents/standards-for-basic-anesthetic-monitoring. Accessed October 10, 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities; 2008. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/disinfection-guidelines.pdf

Dorsch JA, Dorsch SE. Understanding Anesthesia Equipment. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:776-795.

Geddes LA. Cardiovascular Devices and Their Applications. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1984.