CHAPTER 50

Anesthesia Considerations for Out-of–Operating Room (OOR) Locations

Introduction

An “out-of–operating room” (OOR) anesthetizing location is any area located outside of a hospital’s suite of operating rooms (ORs). Recent expansion in the services provided in OOR locations has resulted in an increased need for anesthesia services in these areas as well. Hospitals and providers use a number of synonyms for the term OOR, including “anesthesia at alternate sites,” “non–operating room anesthesia (NORA),” and “remote location anesthesia.” In this chapter, we will use the terms “out-of–operating room” (OOR) and “out-of–operating room anesthesia” (OORA). Common examples of OOR sites include the following:

- A cardiac catheterization laboratory

- A gastrointestinal endoscopy suite

- A site completely separate from a hospital building with no OR facilities, such as a dental clinic or a radiation therapy unit

Office-based anesthesia also falls within this category but will not be discussed in this chapter. The most significant concern for providers in OOR sites is the challenge of caring for patients, often with significant comorbidities, in an unfamiliar environment far from immediate assistance. This lack of familiarity with equipment, procedures, and staff requires extra vigilance to provide safe care. It is in this high-stakes OOR arena that the skill and expertise of a suitably trained anesthesia technician are perhaps most valuable and the partnership between anesthesiologist and technician is most important.

General Principles

The scope of cases performed in OOR areas is broad, and the patients receiving care often have significant health problems. There are a wide variety of techniques, equipment, and approaches to be considered. Distractions are common and can compromise safety. A simple three-step approach is suggested to avoid missing any important aspects of the patient’s care; when providing anesthesia in an OOR location, always consider each of the following carefully:

- The environment

- The patient

- The procedure

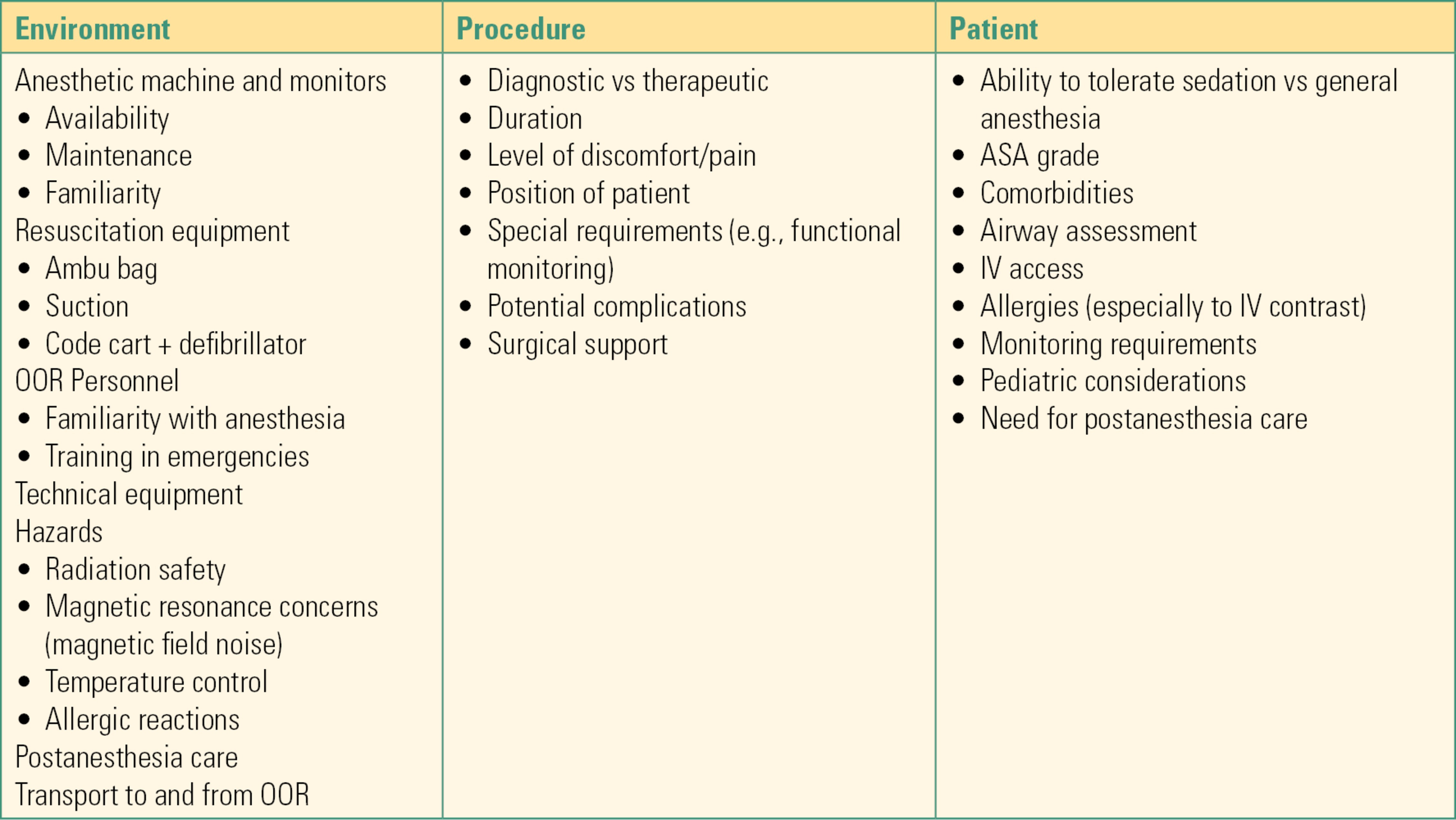

Issues related to these three aspects of OORA are outlined in Table 50.1.

Table 50.1. A Three-Step Approach to Anesthesia in Out-of–Operating Room Locations

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; IV, intravenous.

General considerations will be discussed first followed by the specifics of each category of procedure. Pediatric patients have unique considerations and will be discussed in the final section of the chapter. Chapter 48 discusses pediatric anesthesia in more detail.

The OOR Environment

Considerations include the following:

- The presence of large and complex pieces of diagnostic and therapeutic equipment

- Availability of anesthetic equipment (e.g., advanced airway devices)

- Availability of appropriate anesthesia monitoring, including invasive monitors

- Constraints related to diagnostic and therapeutic imaging techniques

- Unfamiliarity of OOR technical staff with requirements for safe care of sedated or anesthetized patients

- Environmental hazards posed to anesthesia staff, especially ionizing radiation (see Chapter 54)

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Equipment

OOR locations often contain large, heavy, immobile pieces of equipment used for procedures such as fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT). Fluoroscopy is widely used in many OOR locations including interventional radiology, cardiac catheterization, and the gastroenterology suite. Fluoroscopy is an x-ray technique used to obtain moving images of a patient for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. The patient is positioned between an x-ray source and fluoroscopic screen, and by coupling the fluoroscope to an x-ray image intensifier and video camera, the images can be captured and played on a monitor. In some imaging suites, there are two of these image intensifiers, one of which is mobile, to provide biplane imaging. These “C-arms” are moved back and forth around the patient, take up large amounts of space, and are mobile hazards to the patient, personnel, and equipment. CT scanning, which uses x-rays to create two-dimensional image “slices,” can be combined with sophisticated computer software to generate three-dimensional reconstructions of internal structures, allowing for biopsies and interventions in areas of the body that once required open surgical intervention. An anesthesia technician needs to be familiar with the space requirements and hazards associated with these types of equipment, both to protect the patient and to maintain their own safety.

Anesthetic Equipment

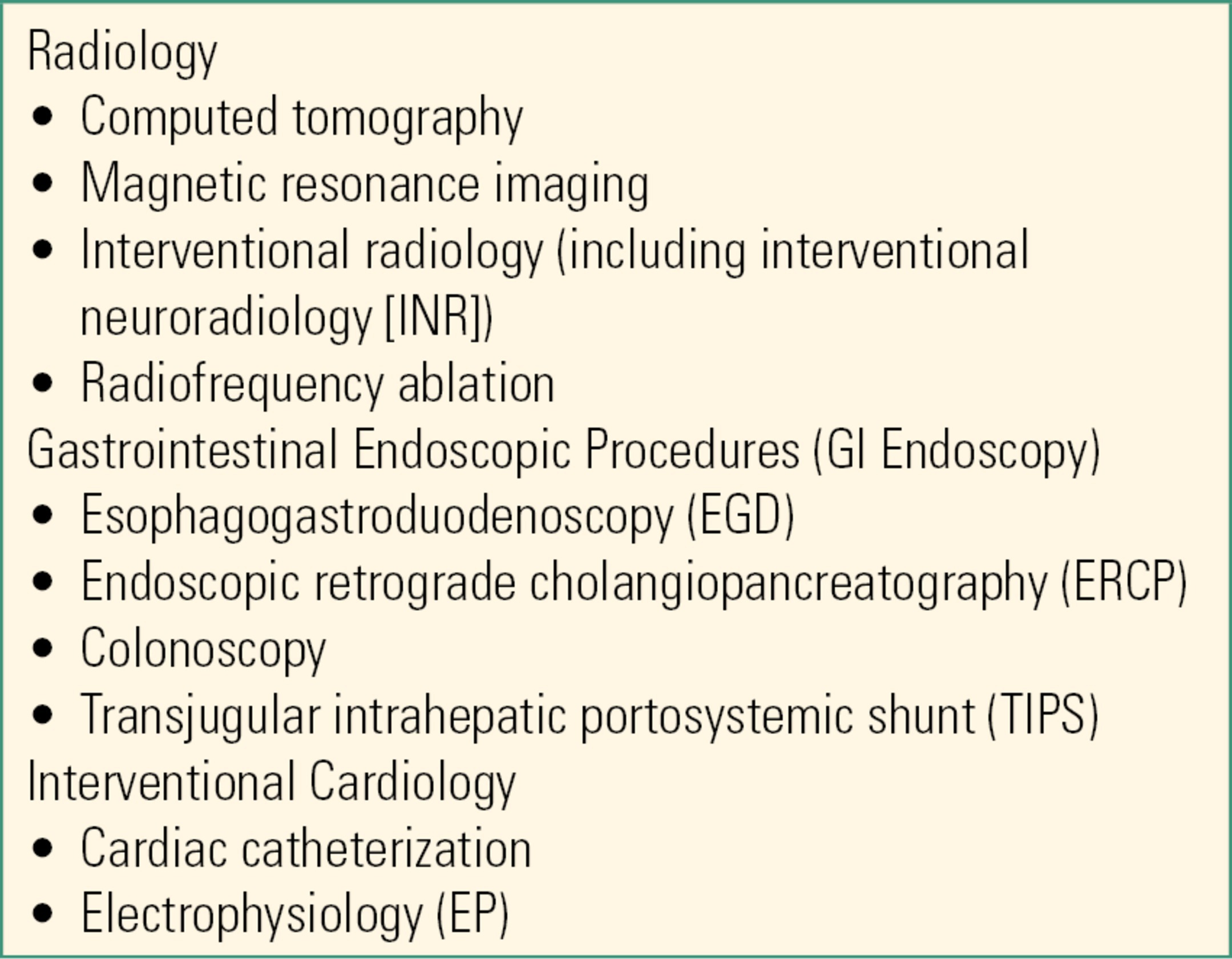

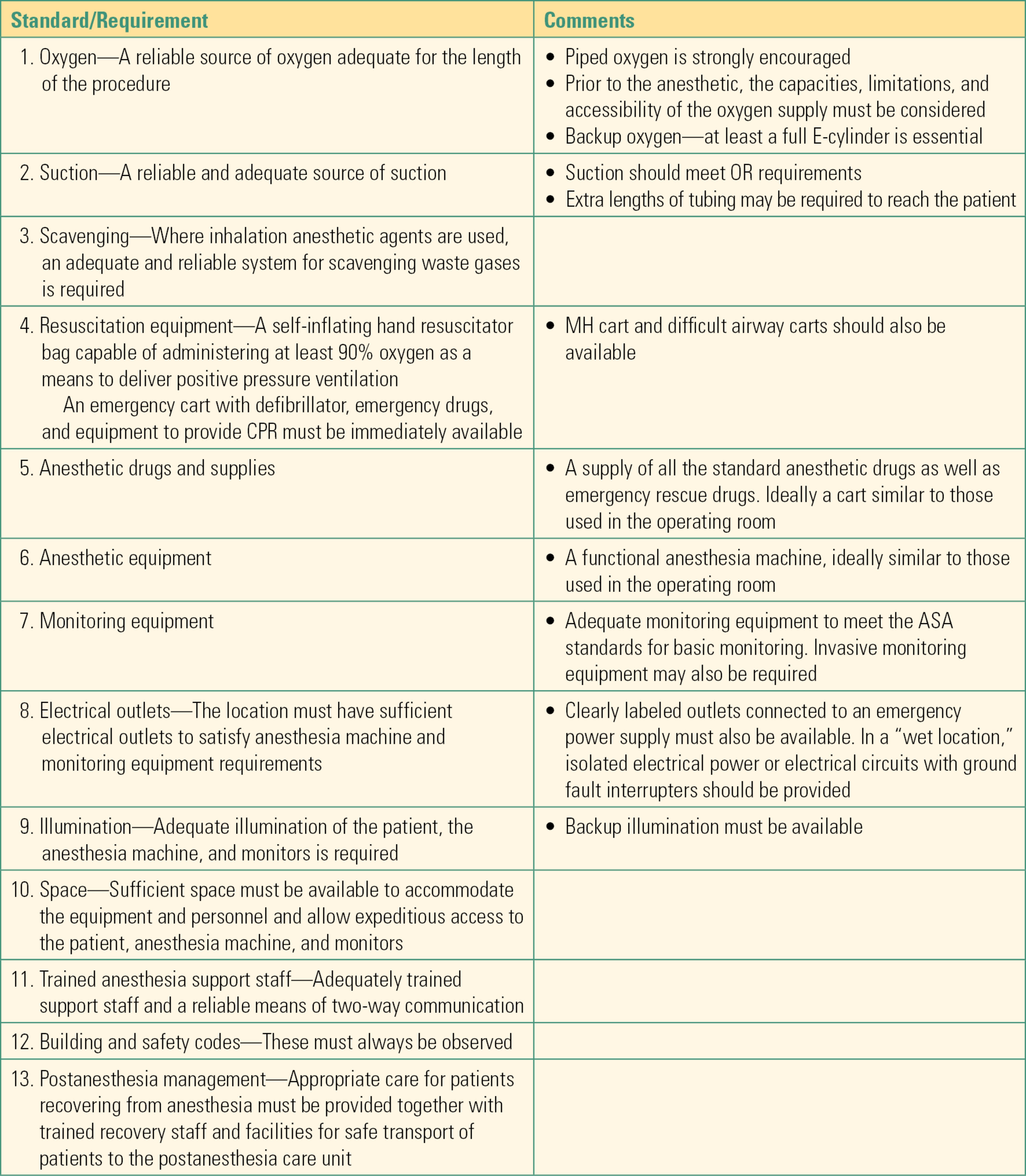

Table 50.2 details equipment standards for all OOR procedures overseen by anesthesiologists published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Standards and Practice Parameters Committee.

Table 50.2. Common Procedures That May Require Anesthesia in Out-of–Operating Room Locations

Health care accrediting bodies generally require that patients undergoing OOR anesthesia or sedation receive the same standard of care as they would in the OR. This means that anesthesia equipment and monitors are of the same standard in both locations, creating a stock and supply challenge in OOR sites, which may only require anesthesia services intermittently. Anesthesia equipment, drugs, and monitors may be stored in the OOR site for use when needed or set up each time an anesthetic is planned. In areas where anesthesia is required on a recurring basis (approximately 3-4 times a week), equipping and maintaining the OOR site with basic anesthesia equipment that can be quickly supplemented with case-specific materials is a reasonable plan. However, problems may occur with this approach. Equipment left in the OOR site may be inadvertently damaged and stocks depleted by nonanesthetic personnel. Anesthesia machines and other equipment need regular maintenance and can easily be overlooked if stored in an area not routinely serviced by anesthesiology technicians. Hospitals may be reluctant to update anesthesia equipment for a site where it is used infrequently, and often, older machines are “retired” to the OOR site. This can create problems of unfamiliarity among anesthesia personnel or no-longer-standard equipment. Additionally, drugs and supplies left in a seldom-visited site may, unnoticed, exceed their expiry date.

The alternative approach is to bring all necessary equipment, drugs, and monitors into the OOR each time an anesthetic is required. Smaller, portable anesthesia machines are commercially available for this purpose; this is perhaps a more sensible approach if anesthesia is performed infrequently. This solution does require extra preparation time; it is all too easy to forget essential equipment requiring multiple trips back to the central anesthesia supply room. These problems can be mitigated by the development of a standard mobile anesthesia cart containing all the necessary equipment that is restocked after every case and by the use of checklists for all the drugs and equipment required for OOR anesthesia. It is also vitally important for anesthesiologist and technician to communicate ahead of time to make sure extra equipment such as special monitors or advanced airway devices are readily available if the case requires them. The provision of anesthesia in the MRI suite is a special circumstance, which is considered in Chapter 52.

Constraints Related to Diagnostic and Therapeutic Imaging Techniques

In a regular OR, the anesthesia workstation is ergonomically oriented so the anesthesiologist has easy access to patient, equipment, and monitors. This is rarely the case in an OOR site. Frequently, diagnostic and therapeutic devices encroach upon the space typically occupied by the anesthesia workspace, limiting access to the patient to a degree that can present challenges during an emergency. Imaging techniques often require that the patient, fluoroscope, or both be moved during image acquisition. This is particularly true of neuroradiologic, CT, and MRI-guided procedures. It is important to make sure the anesthesia breathing circuits, intravenous fluid lines, monitoring cables, and indwelling devices (e.g., urinary catheters, drains) are all of sufficient length to accommodate the patient’s movements during image acquisition. Portable radiation shields, which can provide protection for the OOR staff and patient from unwanted exposure to x-rays, are a further source of potential obstruction.

Out-of–Operating Room Staff

OR staff are generally familiar with the role of the anesthesia team and are available to help in any anesthetic emergency. In OOR sites, technical and nursing staff have different experience and skill sets and may not be as familiar with the conduct of anesthesia or how to help in an emergency. It is vital that the anesthesiologist have experienced anesthesia technical support immediately available to help in emergencies. One area where both the anesthesiology technician and the anesthesiologist can bring additional value to OOR sites is to train staff in team communication and emergency protocols. The entire team should know the location of the code cart, defibrillator, malignant hyperthermia cart, and resuscitation equipment; these items also need to be checked regularly. All OOR staff should be able to provide assistance with emergencies such as cardiac arrest, unanticipated difficult airway, and anaphylaxis. Management of anaphylaxis is particularly important, as systemic reactions to intravenous contrast media used in radiologic procedures are relatively common and can be severe.

Environmental Hazards

The hazards of occupational exposure to ionizing radiation are considered separately, in Chapter 54. In that chapter, you will learn that the three protective factors that reduce radiation exposure are time, distance, and shielding. For the anesthesia technician, one of the important concerns in OOR anesthesia is setting up the anesthetizing environment to protect the anesthesia provider when ionizing radiation is present. This is primarily a concern during fluoroscopic procedures such as neurointerventional procedures and cardiac catheterization procedures. Your setup of these rooms greatly influences the distance that the anesthesia provider maintains from the source of radiation. Configuring the room so that the provider can sit farther away but still see the machine, monitor, and the patient greatly reduces the anesthesia provider’s radiation exposure. Arranging mobile partitions containing shielding to be placed between the anesthesia provider and the source of the fluoroscopic beam also greatly reduces exposure.

Temperature Control

In most OOR sites, the room temperature is cooled to offset heat generated by technical equipment. Anesthetized or sedated patients are susceptible to hypothermia, and care must be taken to ensure patients are adequately insulated and warmed, often requiring both active (typically forced air warming) and passive methods. Conversely, patients undergoing interventional procedures are often covered with drapes, and overheating is a potential risk; in either case, it is important that body temperature be monitored in all patients.

Anaphylactic Reactions

Injectable intravenous dyes known as contrast media are used during many radiologic procedures to enhance the imaging techniques. Radio-opaque materials contain iodine, and similar agents used in MRI contain gadolinium or manganese. Side effects to these agents are relatively common and include nausea and vomiting, urticaria, hoarseness, dyspnea, facial edema, and hypotension. Occasionally, patients develop an acute anaphylactic reaction to contrast media requiring vigorous resuscitation and institution of cardiac arrest protocols if indicated. Chapter 59, Anaphylaxis, covers these protocols.

Patient Concerns in the OOR Environment

Procedures undertaken in OOR sites are frequently less painful than are invasive surgeries, but even painless procedures may require the patient to remain still, often for long periods. Proceduralists may request anesthesia assistance to provide sedation or general anesthesia (GA) to achieve this. Many patients experience anxiety and claustrophobia, particularly when subjected to the enclosed spaces of the CT or MRI scanners, and request some form of sedation to make these experiences more tolerable. The great expansion in therapeutic radiologic procedures has meant that minimally invasive interventions are now being offered to patients who previously would have been considered too fragile to withstand conventional surgical treatment. Thus, many patients who present for OOR procedures have significant comorbidities and need expert anesthesia care and close monitoring.

Procedural Concerns

Table 50.3 lists commonly encountered procedures in the three most common categories of OOR sites. It is important for the anesthesiology team to understand the unique requirements of each procedure needed for optimum imaging and/or for fast and effective therapeutic interventions.

Table 50.3. ASA Guidelines for Minimal Standards of Care for Anesthesiology Personnel Providing Care in Non–operating Room Locations

Radiologic Procedures

Radiologic procedures include noninvasive imaging techniques such as CT, MRI, and interventional radiologic (IR) procedures.

Computed Tomography

CT scanners produce a cross-sectional image of the body in a few seconds, meaning that most adult patients can tolerate CT scanning without anesthesia or sedation. More recently, however, radiologists have begun using the CT scanner to guide invasive procedures such as abscess localization and drainage and radiofrequency tumor ablation in lung, liver, or metastatic cancers. These procedures both take longer and may cause pain, so patients may require sedation or anesthesia to tolerate them. CT is also used for imaging in patients who are severely injured or who are being cared for in the ICU. In both cases, these patients are at risk of becoming acutely unstable in the CT scanner, and the anesthesia team must have the ability to escalate care if necessary. During the scan, very high levels of radiation—up to 1,000 times as much as in a simple x-ray—are generated, placing staff at risk if they remain in the scanner with the patient. Usually, after securing the monitored patient in the scanner, the anesthesia team will retreat to a shielded room where they can observe monitors and see the patient through a glass window or via video link. When planning the anesthetic technique, the team needs to remember that there will be a delay in accessing the patient if an emergency occurs. The airway should be properly secured ahead of time, particularly if there is any suspicion that it may be difficult to do so in an emergency. Sick, unstable patients must receive resuscitation prior to being taken into the scanner, as resuscitation efforts in the CT scanner may be hampered by the confined space.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Because of the high-intensity magnetic fields present at all times near an MRI machine, provision of care presents unique challenges. Please see Chapter 52 for more information about anesthetic care during MRI.

Interventional Radiology

Fluoroscopy (“video x-ray”) is the mainstay of interventional radiology, and in recent years, the discipline has expanded rapidly. With great skill and expertise, interventional radiologists can place microcatheters into most of the larger blood vessels in the body. This allows the injection of radio-opaque dye for diagnostic imaging and for a large number of therapeutic procedures that previously required invasive surgery or were simply not possible. Common examples of IR procedures include:

- Revascularization of a blocked vessel, such as a carotid artery in a patient at risk of stroke

- Insertion of a stent to maintain the patency of a previously blocked vessel

- Embolization of a vessel or vascular malformation that is bleeding or at risk of rupture such as a cerebral aneurysm

- Embolization of a vessel to a malignant tumor prior to invasive surgery to reduce bleeding during the operation

- Combination of both embolization and stent placement for an arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

While the anatomy and pathology of the diseases treated by these various interventional radiologists differ widely, there are a number of commonalities in all IR procedures.

Common Features of interventional Radiologic Procedures

Vascular access is achieved in most patients via the femoral vessels in the groin. Other large blood vessels, including those in the neck or chest, may be accessed if the femoral vessels are unavailable. Access to the blood vessel is first gained using a small needle and then a thin flexible wire. With the wire in the target blood vessel, the radiologist dilates the opening to the vessel using a wide-bore dilating “sheath.” This technique is known as the “Seldinger” technique and is used widely throughout medicine as a safe way of accessing a blood vessel. The sheath permits a variety of microcatheters to be advanced into the blood vessel(s) of interest using fluoroscopy guidance. The radiologist injects dye along the path of the blood vessels while using continuous x-ray as a guide. The patient is positioned on a moving x-ray table surrounded by the imaging equipment. As the catheter is advanced to the vessels of interest, the patient, camera, or both may move, making it vital to closely watch the anesthesia breathing circuits, monitors, IV tubing, poles, machine, and body parts of patient and anesthesia personnel. In order to make sure the road map matches the path of the microcatheter, it is vital that the patient remain completely still, leading to a preference for general anesthesia in many cases. In some cases, even the movement of the patient’s chest during breathing may interfere with the procedure, and at certain moments, the radiologist will ask the anesthesiologist to “hold the breathing” by briefly turning off the ventilator.

The positioning of monitors—especially ECG electrodes—must be carefully considered. If the ECG leads or electrodes overlie the area being imaged, they can produce radiologic shadows and artifacts that interfere with the procedure. In neuroradiologic procedures, the metallic spring in the pilot balloon of the endotracheal tube may obscure the view of a cerebral vessel. Large amounts of the intravenous contrast dye may be used during an IR procedure. These compounds act as diuretics, making a urinary catheter a requirement for most of these procedures.

Interventional Neuroradiology (INR)

Neuroradiologists have developed techniques for treating various vascular pathologies that were previously within the realm of the neurosurgeons. The major advantage of this approach is the avoidance of intracranial surgery. In addition, patient outcomes following interventional treatment of cerebral aneurysms and AVMs are favorable, and in many cases superior, to surgery. Spinal AVMs may also be successfully treated by INR. Common INR procedures include embolization of cerebral aneurysms, treatment of AVMs, ablation and stenting of an occluded carotid artery, embolization of a tumor prior to surgery to reduce the risk of intraoperative bleeding, and clot extraction for acute stroke. Embolization techniques vary: they can involve deploying tiny detachable platinum coils into the relevant vascular pathology via the microcatheter, or various glues and occlusive particles can be injected into the offending vessel. It is vital that these substances are injected into the correct site; injection into the wrong site may injure healthy brain tissue, causing a stroke. INR procedures require the patient to be completely still. Additionally, patients requiring these types of procedures may be acutely ill, with increased intracranial pressures, altered levels of consciousness, and other manifestations of brain injury. As a result, most patients require general anesthesia, most often with an endotracheal tube. Blood pressure control is vital, as uncontrolled hypertension may result in rupture of an aneurysm and hypotension may cause cerebral ischemia. In many cases, the anesthesiologist will require invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring. Ideally, this will be via a radial artery catheter, although if this is difficult to place, the anesthesiologist may make intermittent intra-arterial blood pressure measurements from the femoral artery sheath. In some cases, due to a need to monitor brain function, sedation may be preferred so that a neurologic exam can determine that certain vital areas of the brain such as the speech and motor centers remain intact. The main complication of neuroradiologic procedures is bleeding into the brain or death of part of the brain—stroke. In the case of acute hemorrhage, one treatment option is to rapidly convert to an open craniotomy. This requires that INR locations be close to the ORs in case of an emergency. In the case of rupture, the patient will need rapid transportation from the OOR location to the OR with full, ongoing resuscitation by the anesthesia team.

Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Procedures (GI Procedures)

Commonly performed procedures include esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and colonoscopy. EGD, ERCP, and colonoscopy are carried out in the GI endoscopy suite, which is usually outside the OR, often in ambulatory surgical centers intended for relatively healthy patients. Flexible fiberoptic scopes (endoscopes) are inserted into the patient and the real-time images observed on a monitor. Fluoroscopy is used to supplement the images and to guide the proceduralist during ERCP. These procedures often cause a degree of discomfort and nearly all patients require some form of sedation. Historically, mild to moderate sedation was provided by trained nurses under the supervision of the proceduralist, and this remains common today. With increasing procedural complexity and patient comorbidities, however, the demand for anesthesiology to care for patients in the GI endoscopy suite will likely increase.

Upper Endoscopy and Its Variants

From the anesthetic perspective, upper endoscopy procedures have many similarities. In EGD, the endoscopist passes a flexible fiberoptic endoscope through the patient’s mouth into the esophagus, through the stomach, and into the upper intestinal tract. Depending on the patient’s anatomy and the preference of the proceduralist, the optimum patient position for the procedure may be supine, lateral, semiprone, or fully prone. A variety of procedures may be carried out including visualization and biopsy of pathology, retrieval of foreign bodies, treatment of esophageal varices, dilation of esophageal strictures, and placement of a percutaneous gastrostomy. Depending on patient comorbidities and the likely invasiveness of the procedure, sedation is usually sufficient, but conditions such as liver failure, ascites, and bleeding esophageal varices may necessitate care by an anesthesia provider.

A variant of EGD is endoscopic ultrasound, EUS, in which a larger endoscope is introduced, usually for diagnostic biopsy of a mass. This procedure often requires deeper levels of sedation, both because of the size of the endoscope and the need for immobility for optimal biopsy; anesthetic care is often requested. In ERCP, the proceduralist accesses the pancreatic and biliary systems. Procedures include taking biopsies, treating obstruction caused by gallstones, and placing stents to bypass strictures both malignant and benign. Anesthetic care with deep sedation facilitates access to the biliary tree as well as patient comfort with what can be a long procedure. Patients with advanced biliary and/or pancreatic disease may be acutely ill or suffering from terminal malignant disease.

Anesthetic considerations include a careful preanesthetic evaluation and development of a plan to optimize care for these patients. A major concern in upper GI endoscopy is the patient’s airway, particularly for long or complex procedures. “Sharing” the airway with the proceduralist’s endoscope may complicate care, as its presence in the pharynx as well as the possible need for prone or semiprone procedural positioning places the patient’s airway at risk of obstruction. In addition, agents commonly used for anesthesia and sedation such as benzodiazepines, opioids, and propofol may cause upper airway obstruction by reducing muscle tone and protective reflexes. Passage of the endoscope into the patient’s pharynx and esophagus requires the powerful gag reflex to be suppressed, which is facilitated by topicalizing with local anesthetic. Suppression of airway reflexes unfortunately also places the patient at risk for aspiration of gastric contents, which should be removed via the endoscope if present. Aspiration is a concern that prompts general anesthesia instead of deep sedation for some patients.

Colonoscopy

In colonoscopy, airway considerations are obviously less of a concern. Distension of the colon (like the sensation of “gas”) can be painful, however. Moderate sedation is usually sufficient unless the patient has particular comorbidities—for example, morbid obesity or a difficult airway—that would make sedation risky.

Interventional Cardiology

The range of procedures performed by cardiologists on increasingly sick patients is growing. There are two main areas where interventional cardiology procedures are performed: the cardiac catheterization laboratory (CCL) and electrophysiology laboratory (EPL). While much of the work in these sites may be performed either without sedation or with very light sedation, there is an increasing requirement for anesthesiology to be involved.

The same general considerations that have been discussed above apply to interventional cardiology cases; both EPL and CCL contain large amounts of technical monitoring and imaging equipment. Fluoroscopy is used for imaging the heart, the coronary blood vessels, and the major veins entering and arteries leaving the chest.

Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory

Interventional procedures performed in the CCL are all percutaneous: coronary interventions (PCI), insertion of ventricular assist devices (VADs), closure of septal defects, and heart valve repair/replacement. PCI involves the insertion of a microcatheter into the coronary blood vessels to revascularize a blocked vessel. Some patients may present as outpatients for elective procedures, while others may present with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or myocardial infarction (MI). For these emergency patients, the vessel blockage must be quickly relieved in order to limit the amount of cardiac tissue damaged by deprivation of oxygen. In most cases, PCI procedures do not need the services of the anesthesiology team.

Percutaneous VAD, closure of septal defects, and valvular repair/replacement are performed on some of the sickest patients in the hospital. VADs are used in patients who are in cardiogenic shock: their heart disease is acutely depriving their other organs of oxygen. VADs may also be used in patients with chronic heart failure to support them while awaiting heart transplantation. Percutaneous valve repair is increasingly being used with very successful outcomes in elderly patients who are too sick to tolerate open heart surgery. These patients are usually cared for by cardiac anesthesiologists with expert anesthesia technical support. The conduct of the anesthetic requires careful planning: invasive monitoring and a carefully titrated GA are the preferred techniques, although some centers are now using sedation with favorable results.

Electrophysiology Laboratory

The main procedures performed in the EPL are ablations of cardiac conducting tissue responsible for arrhythmias and insertion of implantable cardiac pacemakers.

Catheter Ablation

This is an invasive procedure performed to remove a faulty (“aberrant”) electrical pathway in patients with cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), and Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. A flexible catheter is advanced from a large vein into the heart, and electrical impulses are used to induce the arrhythmia while mapping the internal surface of the heart. Once the aberrant part of the cardiac conduction pathway has been identified, a different catheter can be used to heat (ablate) and damage that specific area with the intention of interrupting the pathway and thus preventing the abnormal rhythm. These procedures are extremely long, lasting on average 6-8 hours, but have high success rates. Apart from having to lie still for many hours, patients generally tolerate these procedures well with sedation. Minimal sedation may be provided by the EPL team, although in certain circumstances, anesthesiology will need to be involved, usually for patients who have significant comorbidities such as congestive cardiac failure or airway concerns. In some cases, cardiac arrhythmias induced during the procedure require cardioversion for termination; when this happens, sedation needs to be deepened so that the patient can tolerate the unpleasant sensation of receiving a direct current (DC) shock via the defibrillator. The anesthesiology team needs to be aware of the progress of the procedure to be able to anticipate the need for changing the level of sedation; communication with the cardiac team is paramount.

Cardiac Pacemakers

Cardiac pacemakers and internal cardioverter-defibrillators are covered in Chapter 46. Patients receiving these devices may have significant cardiac pathology. These patients may be extremely sensitive to the cardiac depressant effects of even small doses of anesthetic drugs and will often require the services of an experienced cardiac anesthesiologist and anesthesia technician. A secure airway and provision of invasive cardiac monitoring may be required. Insertion of ICDs and other pacemaker devices takes place in the EPL, and mild to moderate sedation is often sufficient for most of the procedures. If an ICD is placed, it will need to be tested, at which point the patient will require deeper sedation or general anesthesia, as induced ventricular fibrillation and defibrillation are very unpleasant for an awake patient. When these patients are prepared for anesthesia or sedation, they must have external defibrillator pads applied for immediate defibrillation if the implanted device fails during testing.

All procedures carried out in the EPL and CCL carry significant risks. The heart may be injured or perforated, which can cause blood to enter the pericardium (a stiff, fibrous sac around the heart). This can become so full of blood that it prevents the heart from filling, a condition called cardiac tamponade, which causes cardiogenic shock. The risk of this kind of injury is highest when established pacemaker leads need to be taken out: for this reason, leads are rarely removed, and when they are, this is usually done in an OR. Other possible complications include MI, stroke, and pneumothorax. The need for rapid transport to the cardiac OR is a real consideration, and the equipment necessary to facilitate the transfer of an acutely unstable patient must be readily available at all times. Pediatric patients undergo interventional cardiac procedures mostly for congenital heart defects and again are often extremely sick.

Anesthesia Concerns in OOR Sites

Choice of anesthetic technique in OOR locations depends on a large number of issues including the following:

- Constraints of the environment

- The particular requirements of procedure and proceduralist

- Patient preferences and associated comorbidities

Important considerations in preparing for the anesthetic include suitability of general anesthesia vs sedation, airway assessment, adequacy of intravenous access, and the provision of adequate postanesthesia care.

Constraints of OOR Environments

Unlike an OR, the out-of-OR environment may be defined by its constraints. Environments for the provision of anesthesia must meet regulatory requirements and ASA standards. Many OOR environments were not originally designed as anesthetizing locations. They may not have wall suction or oxygen, and these may be brought in as portable supplies. They may have wall suction and oxygen, but not air. Anesthesia gas use is not feasible if scavenging via wall suction is not available: TIVA (total intravenous anesthesia) will need to be the planned anesthetic. Unplanned laboratory, medication, or additional personnel resources may or may not be readily available. Space may be cramped. Hospital care may be available only by ambulance.

General Anesthesia vs Sedation

Sedation is covered in detail in Chapter 15. Unlike surgical procedures in an OR, many procedures in an OOR location typically do not require a general anesthetic due to surgical pain; patients usually go to the OR to be cut into with a knife. Local anesthetic can be used generously in the OOR setting for percutaneous procedures like pacemaker pocket placement and groin access; 30 years ago, interventional radiology, gastroenterology, and cardiac catheterization were often performed with minimal to no sedation. Procedures now are more complex but most (with notable exception such as cardioversion and RF ablation of cancers) are not painful. This has several implications for anesthesia care. The decision to perform a general anesthetic is often not absolute. For many procedures, such as interventional radiology and ablation of atrial fibrillation, patients must be absolutely immobile. In these situations, and many others involving difficult, multistep procedures, very sick patients, or procedures in which complications are likely, general anesthesia may be preferred. However, proceduralists, anesthesiologists, and centers vary in their preferences for modes of anesthesia, with one center advocating light to moderate sedation in a cooperative adult (“it’s really important to hold still right now”) and another advocating general anesthesia for the same procedure. Truly uncooperative patients are likely to require general anesthesia rather than sedation to maximize the chance of a successful outcome. Very ill patients, conversely, may do best with light sedation and a skilled anesthesiologist at the ready prepared for emergencies, along with an anesthesia technician prepared to assist urgently with advanced technologies in an unfamiliar and faraway environment. For example, all patients awaiting heart transplant, including those with left VADs, need screening colonoscopy first.

Airway Assessment

As discussed, patients in OOR locations may not be immediately accessible to the anesthesiologist; thus, careful airway evaluation ahead of the procedure is vital. If the airway appears potentially difficult and if there is any possibility of the airway being “lost” (e.g., due to unintentional oversedation) during the procedure, it may be safer to intubate the patient ahead of time to ensure a secure, protected airway throughout. This is highly preferable to being forced to interrupt the procedure to rescue the airway, which may not be immediately possible, particularly in the MRI scanner or radiotherapy suite.

Similar concerns apply to the adequacy of intravenous access—it is wise to establish reliable, large-bore, and free-flowing IV access prior to embarking on any OOR procedure whether under sedation or general anesthesia.

Postanesthesia Care and Patient Transport

Any patient who has received general anesthesia or sedation must be recovered in a properly staffed postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Most OOR locations do not have a dedicated PACU with appropriately trained nursing staff, so patients need to be transported from the OOR location to the PACU. Patient transport is covered in Chapter 51.

Anytime a patient is being considered for transport between care locations (either within or between hospitals), a number of important conditions need to be satisfied:

1. Patient stability

Except in an emergency situation, patients should not be transported if they are unstable from the airway, respiratory, or cardiovascular perspective.

2. Oxygen and emergency equipment must accompany the patient

When transporting a patient, a full cylinder of oxygen should accompany the patient as well as suction equipment and emergency resuscitation and airway equipment. This is particularly important when transporting intubated and ventilated patients; spontaneously breathing patients should receive supplemental oxygen via an appropriate delivery device during transport.

3. Full monitoring

During transfer of sedated patients, the same minimum standards of ASA monitoring apply, that is, continuous pulse oximetry, ECG, and noninvasive blood pressure. In intubated patients, capnography and more invasive monitoring may be required.

4. Team communication

Open and clear channels of communication between transporting and receiving providers are essential to facilitate safe and expedient patient transfer. When transporting from an OOR location to PACU, the anesthesia team should confirm that there is space and trained staff available before moving the patient. On arrival, a full handover of care to PACU staff should occur; use of checklists may reduce relevant omissions during handover and improve safety.

Pediatric OOR

Children are subject to an ever-increasing variety and complexity of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and investigations. Many of these are the same as those performed in adults at the OOR locations already described, and similar location-specific (e.g., MRI) generic considerations and concerns apply. However, due to a multitude of behavioral characteristics including fear, separation anxiety, incomprehension, noncooperation, and intolerance of procedural pain, children require general anesthesia in many more of these cases than do adults. In addition, there are other OOR locations (e.g., radiation therapy) where general anesthesia is used almost exclusively for children. Medically complex and extremely sick children are often cared for in these challenging environments out of necessity.

Historically, many OOR cases performed on children were attempted under sedation with varying degrees of success. The benefits of such an approach included ease of administration (typically oral medication), low cost (frequently overseen by an appropriately trained nurse), speedier recovery/discharge postprocedure, and avoidance of the risks of OOR anesthesia. Disadvantages include a relatively high failure rate (patients either undersedated or dangerously oversedated), unpredictable on/offset of orally administered sedative medications resulting in scheduling difficulties, and suboptimal procedural pain management. The increasingly unacceptable (to families, hospitals, and providers) failure rate associated with this approach has led many centers to adopt a care model incorporating general anesthesia as the default choice for children. However, safely anesthetizing small and often medically complex children in these varied environments requires careful planning and preparation. This is best performed by a suitably trained anesthesiologist and requires the expert assistance of a well-trained anesthesia technician.

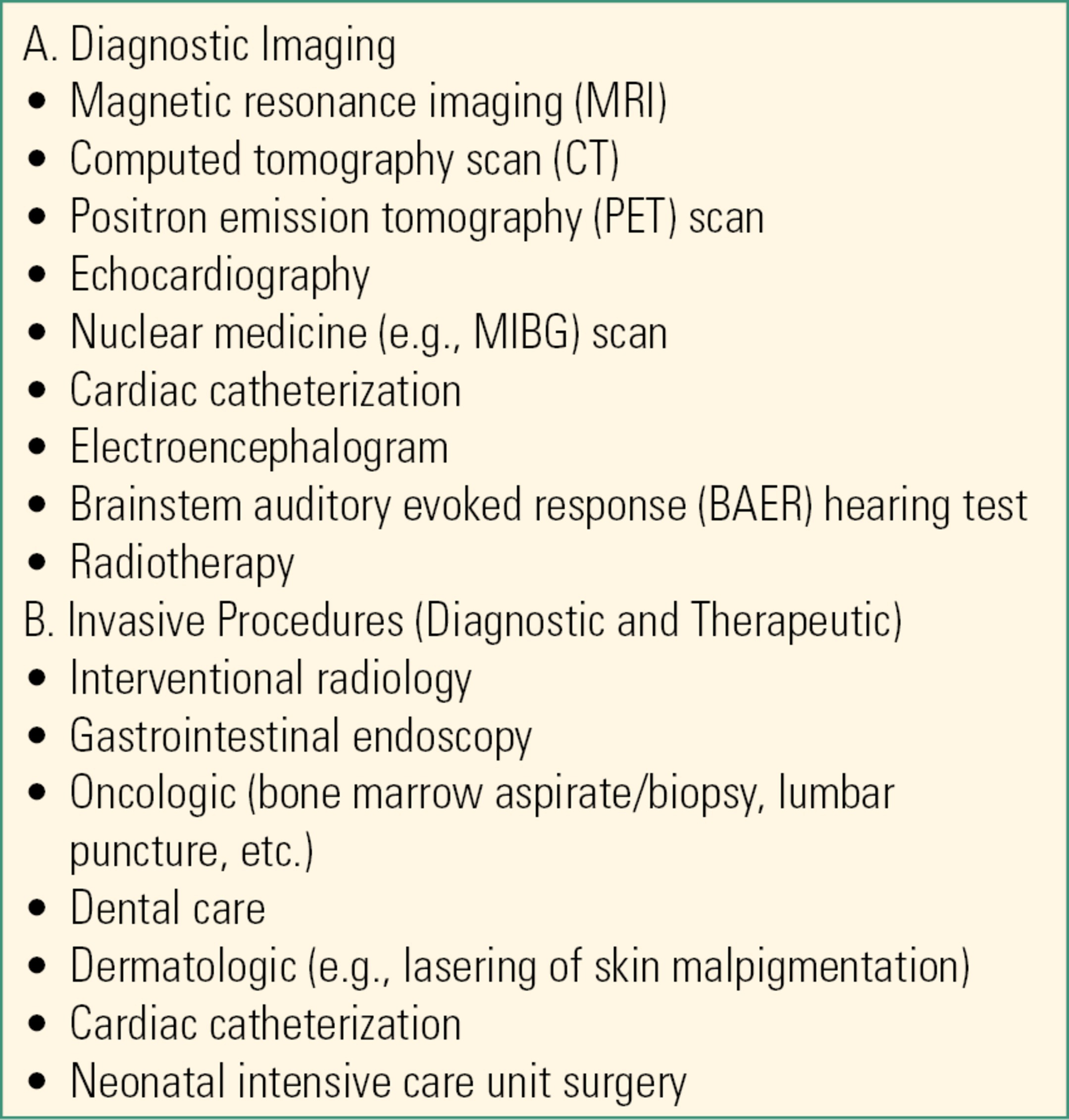

Scope of Practice for Pediatric OORA

Pediatric OORA can be divided into two categories: those in which imaging is the primary outcome and those in which some procedure is to be performed. Procedures can be further subdivided into those which are predominantly painless (noninvasive) and those in which some pain is expected (invasive). There is some overlap between groups, for example, cardiac catheterization, which is often primarily an imaging study, necessarily involves some pain during groin vessel access, and may also involve painful intracardiac manipulation of the catheter.

Currently, OOR accounts for approximately one-third of all general anesthetics given per year in this author’s busy tertiary children’s hospital in the United States. Table 50.4 summarizes common OOR procedures performed in pediatric patients. As with adults, children require general anesthesia in a large number of disparate sites, all of which must conform to ASA minimum standards for anesthetizing locations, for example, equipment, gas supply, vacuum, etc. (see Table 50.2). In addition to the OOR sites already described for adults, children require general anesthesia for procedures in two other locations, which will be considered separately: radiation oncology and hematologic oncology units.

Table 50.4. Common Out-of–Operating Room Procedures Performed on Pediatric Patients

Radiation Oncology

External beam radiation therapy (XRT) is a frequently used modality in the treatment of malignancies. The radiation beam is aimed very precisely to minimize harming adjacent healthy tissue, and although not painful, it requires the recipient to remain absolutely still. In some cases, the prone position is necessary for treatment, and as a result, general anesthesia is the method of choice for young or uncooperative children. There are typically two phases of treatment: first, single “simulation” encounter in the CT scanner and subsequent treatment visits in the XRT vault. “Simulation” is an opportunity to take detailed CT-derived measurements of the tumor to plan therapy and also to make personalized face masks and/or body molds to ensure uniformity of positioning during subsequent treatments. Masks of a thermosetting mesh are molded directly onto the anesthetized child’s face and maintain both airway patency and head position. Ideally, this is achieved without the use of airway adjuncts (e.g., oropharyngeal airway) because once used, all future treatments will also require their use to ensure uniformity. Treatment visits must, uniquely, occur within a radiation-shielded vault to protect staff. The anesthesiologist must remain outside of the vault observing the child remotely on a linked monitor and closed-circuit television whenever the radiation beam is on and can only enter the treatment room when the beam is off; this has obvious implications for timely response to an emergency. Treatments are typically brief and the anesthetic technique should allow for rapid induction and emergence. The preferred anesthetic technique at our institution is by propofol infusion with spontaneous breathing and supplemental oxygen provided by nasal cannula. The vast majority of children presenting for XRT already have a tunneled central line in situ, which makes a TIVA technique suitable. Proton beam therapy is a newer treatment modality with similar anesthesia considerations.

Hematologic Oncology

These units care for children with life-threatening illnesses such as leukemia and lymphoma, which are characterized by prolonged courses of recurrent painful interventions, for example, lumbar puncture, bone marrow aspiration, and biopsy. Many units have a dedicated procedure room to allow coordination of care between different providers in the familiar setting of the unit. Unlike XRT, these procedures are usually very brief but painful, requiring the addition of short-acting potent opioids (e.g., alfentanil) to a planned propofol TIVA technique. Again, tunneled central lines are the norm: these facilitate the induction process and should be accessed with the utmost sterility as central line infections can be very serious and interfere with planned cancer treatment.

Practical Considerations

Ideally, general anesthesia should be induced with the child either in or adjacent to the procedure room. Parental presence may facilitate a less stressful induction for the child. In some cases, judicious use of an oral, intravenous, or intramuscular premedication may also be necessary (e.g., for autistic children with behavioral problems). General anesthesia is preferably induced via either the intravenous or (if unavailable) inhaled route after which airway management is instituted. This may involve intubation with an endotracheal tube, placement of a size-appropriate laryngeal mask airway (LMA), or placing nasal cannula to deliver low-flow oxygen (typically 2 L/min) with or without an oropharyngeal airway in situ. General anesthesia may be maintained with either inhaled volatile agents or by titrated continuous infusion of hypnotic agent. Commonly used intravenous agents include propofol at rates of 200-400 μg/kg/min supplemented with small boluses of short-acting opioids. For longer, painful procedures, opioid infusions may be used. A spontaneous breathing technique is often preferred as it avoids the need for frequent adjustment of ventilatory parameters, which may be awkward from the remote vantage point of radiotherapy, and is arguably safer should a disconnection or extubation occur. Capnography is mandatory. Children undergoing MRI will also need ear protection provided by disposable wax earplugs.

Complications during Pediatric OORA

The two most commonly encountered problems are sudden, unexpected movement by the child and airway or breathing insufficiency. The latter may be heralded by either decreased oxygen saturation or changing or absent capnography tracing, especially in an unintubated child. These two problems often occur simultaneously and may indicate a plane of anesthesia too “light” for the prevailing stimulation. Unexpected “lightening” of anesthesia may be due to remote equipment failure (e.g., infusion pump). The solution is often to rapidly deepen anesthesia with small incremental boluses of medication, but if the problem persists or worsens, it may be necessary to urgently extract the child from their OOR location and initiate rescue interventions. In the case of MRI, this may require emergently removing the child from the magnet to a safe nearby location.

Recovery from General Anesthesia

As with adults, children undergoing OOR will usually need to be transported from or between remote locations and to the PACU at the conclusion of their procedure. The decision whether to wake the child in the OOR location before transport depends upon many factors including characteristics of the current OOR location, child’s baseline condition, anesthetic technique employed, procedural factors, and distance/staffing of the PACU in question. It may be preferable to allow the child to wake in the relatively controlled environment of the OOR location rather than during transport to a distant PACU. If the child is to be transported relatively long distances, it may be safer to continue administration of anesthetic agents if possible during the journey. This strategy requires that the same monitoring, ventilation/oxygen, fluids, thermoregulation, and emergency supplies that were available in the OOR location be available for the entire journey.

Future Trends in Pediatric OOR Anesthesia

The debate over who should ideally provide procedural sedation or anesthesia for children continues around the developed world. Undoubtedly, increasing numbers of providers from a variety of medical and nursing specialties (emergency medicine, intensive care, etc.) other than anesthesiology are offering their services as sedation providers. Ultimately, a critical future role for anesthesiology providers may be in the training, credentialing, and support of such providers to ensure the safest possible care for pediatric patients.

Summary

Out-of-OR anesthesia presents a unique challenge to the anesthesia provider but also to the anesthesia technician. Environments for care are often not designed for anesthesia care and may have adverse layouts, environmental hazards, absent infrastructure, and staff unaccustomed to assisting with anesthesia. Equipment may be located far away or missing. A well-informed, prepared, and forward-thinking anesthesia technician can make up for many of these deficiencies with standardized procedures for stocking and setup of OOR areas, thoughtful preparation when cases are booked, provision of appropriate equipment, and understanding the needs of providers during each type of case, so that care can be provided safely. Out-of-OR anesthesia is one of the places where good anesthesia technician support makes the biggest difference to anesthesia providers and to patient safety.

Review Questions

1. Which of the following statements concerning administration of anesthesia in an OOR location is not true?

A) Monitoring standards for patients being anesthetized in OOR locations are identical to the ASA standards used in the OR.

B) Anesthetic equipment left in OOR sites may be missing essential items and should be checked thoroughly before every case.

C) OOR technical staff may be less familiar with anesthetic procedures than are main OR personnel.

D) Code carts are not required as codes rarely occur.

E) Neither wall suction nor wall oxygen is necessary for a room to be an anesthetizing location.

Answer: D

Codes are uncommon in OOR locations; however, they may occur and a code cart must be present within the OOR location. All staff must know where the code cart is and be familiar with resuscitation protocols. ASA standards for the administration of anesthesia are the same everywhere regardless of the target level of anesthesia or sedation. Suction and oxygen are both required to provide anesthesia, but both can be supplied portably.

2. Concerning MRI scanners, which of the following is true?

A) In the case of an emergency during anesthesia for a patient undergoing MRI, the magnetic field should be shut down to allow the anesthesia team rapid access to the patient.

B) All staff must wear dosimeters to keep track of their exposure to harmful magnetic radiation.

C) Modern anesthetic equipment is designed to be safely used in an MRI scanner.

D) Most MRI scans are of brief duration, and patients rarely require sedation.

E) Patients with any implantable device must be assessed by an MRI technologist for safety before entering the MRI scanner.

Answer: E

The magnetic field can interfere with devices like pacemakers and can cause them to malfunction; it can also cause older ferromagnetic implantable devices like aneurysm clips, or newer devices like epidural catheters, to move or heat up. The MRI magnetic field remains on at all times, and patients need to be removed from the scanner if an emergency occurs; immediate shutdown is not possible, and rapid shutdown (“quench”) can cause its own emergency (see Chapter 52, MRI Safety). Dosimeters are used to monitor radiation exposure; the MRI scanner does not produce radiation. Only specially designed anesthetic equipment is compatible with the magnetic field. Most MRI scan sequences last at least 45 minutes and often longer.

3. Procedures carried out outside of the operating room include all of the below except

A) Percutaneous insertion of a left ventricular assist device

B) Insertion of an automatic cardiac defibrillator

C) Removal of a pacemaker lead

D) Insertion of a carotid artery stent

E) Repair of a stenosed mitral valve

Answer: C

Pacemaker leads are removed in the operating room because of the high risk of injury to the heart. All the others are performed in the out-of-OR setting.

4. Concerning sedation, which of the following is correct?

A) Sedation describes a number of clearly defined and discrete states between the fully awake state and full unconsciousness.

B) Airway obstruction is not a concern with moderate sedation.

C) Drugs used to provide sedation are different from the ones used to induce anesthesia.

D) Pediatric patients always require GA in OOR sites.

E) Respiratory depression is a side effect of the majority of agents used for sedation.

Answer: E

The majority of sedative agents produce respiratory depression. Sedation is described as a continuum between the awake state and GA. Patients may move variably in and out of different levels of sedation depending on the type of stimulation and the drugs administered. The airway may be compromised at any level of sedation. Many of the drugs used for sedation are also used as part of an anesthetic. Pediatric patients may be successfully managed with sedation or with general anesthesia in OOR sites.

5. You are in an OOR location and the patient has been given radiopaque materials to enhance the images when the patient starts to complain of feeling sick. Which of these symptoms would be most concerning?

A) Nausea and vomiting

B) Tachycardia

C) Flushing

D) Sweating

Answer: B

Contrast reactions are relatively common: symptoms include nausea and vomiting, urticaria, hoarseness, dyspnea, facial edema, wheezing, tachycardia, and hypotension. Tachycardia (especially in combination with hypotension, facial edema, or wheezing) may be a sign of an anaphylactic reaction. Facial edema is concerning as it can be a sign of edema of the airway as well. Wheezing and dyspnea are signs of bronchospasm but can also be signs of threatened upper airway closure.

6. Which of these is not true for interventional radiologic procedures?

A) The Seldinger technique is used as a way to access a blood vessel without initial use of a large needle.

B) The patient may be on a moving x-ray table surrounded by moving imaging equipment, so it is important to be aware of all tubing and monitors during this time.

C) Monitors can produce artifacts that interfere with the procedure and must be properly placed.

D) Because these are often minimally invasive procedures, the anesthesia provider will usually prefer minimal anesthesia and sedation.

E) All of these are true.

Answer: D

Since it is vital that the patients remain completely still during these procedures, anesthesia and interventional radiology providers may prefer general anesthesia. The Seldinger technique involves dilating a vessel that has been accessed with a smaller needle and is widely used throughout medicine. Since monitors can produce artifacts that interfere with the procedure, and since the patient is often on a moving x-ray table surrounded by moving imaging equipment, it is vital to be aware of the location and placement of all anesthesia equipment.

7. Correctly match the action with the possible consequence for interventional neuroradiology procedures.

A) Glues and occlusive particles injected into the wrong vessel → stroke

B) Hypertension → stroke

C) Hypotension → aneurysm rupture

D) A + B

E) B + C

F) A+ B + C

Answer: A

If glues and occlusive particles are injected into the wrong vessel during an INR procedure, it may lead to stroke. Hypertension can result in the rupture of an aneurysm and hypotension can lead to cerebral ischemia. The main complication of neuroradiologic procedures is cerebral hemorrhage and stroke; acute hemorrhage may require rapid conversion to open craniotomy, and so the location carrying out this procedure should be located close to an operating room.

8. Which of the following would not be performed in the cardiac catheterization lab?

A) Insertion of percutaneous VAD

B) Closure of septal defects

C) Catheter ablation

D) Heart valve repair

E) Heart valve replacement

Answer: C

Insertion of percutaneous VAD, closure of septal defects, and heart valve repair/replacement are regularly performed in the cardiac catheterization lab. Catheter ablation is typically performed in the electrophysiology lab.

9. Which of these are true regarding catheter ablation procedures?

A) Patients are required to be completely still, so anesthesia providers usually opt for general anesthesia.

B) During this procedure, the cardiologist will attempt to use electrical impulses to convert the patient to normal rhythm.

C) This procedure is relatively short, lasting about 2-3 hours.

D) A catheter is used to damage the part of the conduction pathway responsible for the abnormal rhythm, usually with heat.

Answer: D

During catheter ablation, the cardiologist will identify the part of the heart responsible for the abnormal rhythm and will use a catheter to heat and damage this area, thus interrupting the pathway and preventing abnormal rhythm. Patients are typically able to handle this procedure with sedation, although some patients may struggle with the length of the procedure (highly variable but possibly up to 8 hours). The cardiologist may induce arrhythmias to identify the aberrant part of the heart. Cardiac ablation is performed in the electrophysiology lab.

10. There are many factors that may determine whether a child should be awakened in the OOR location or the PACU following general anesthesia. However, which of the following is not one of the factors mentioned in this text as something that should usually be considered?

A) Child’s baseline condition

B) Anesthetic technique used

C) Distance to PACU

D) Parent request to be present when child emerges

E) Procedural factors

Answer: D

When deciding whether to wake the child in the OOR location or the PACU, you should consider the child’s baseline condition, the anesthetic technique used, procedural factors, and distance to the PACU. Parents are often present at the induction of anesthesia at the discretion of the anesthesia provider (see Chapter 48, Pediatric Anesthesia) and typically rejoin children after emergence is complete.

SUGGESTED READINGS

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Statement on nonoperating room anesthetizing locations. Available from: http://www.asahq.org/~/media/sites/asahq/files/public/resources/standards-guidelines/statement-on-nonoperating-room-anesthetizing-locations.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2016.

Bell C, Sequeira PM. Nonoperating room anesthesia for children. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2005;18(3):271-276. doi:10.1097/01.aco.0000169234.06433.48.

Coté CJ. Round and round we go: sedation—what is it, who does it, and have we made things safer for children? Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18(1):3-8. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02403.x.

Coté CJ, Wilson S; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: an update. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2587-2602. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2780.

Goulson DT, Fragneto RY. Anesthesia for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Anesthesiol Clin. 2009;27(1):71-85. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2008.10.004.

Harris EA. Sedation and anesthesia options for pediatric patients in the radiation oncology suite. Int J Pediatr. 2010;2010:870921. doi:10.1155/2010/870921.

Miller DL, Vañó E, Bartal G, et al. Occupational radiation protection in interventional radiology: a joint guideline of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe and the Society of Interventional Radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33(2): 230-239. doi:10.1007/s00270-009-9756-7.

Myr NP, Michel J, Bleiziffer S, et al. Sedation or general anesthesia for transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(9):1518-1526. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.08.21.

Schleelein LE, Vincent AM, Jawad AF, et al. Pediatric perioperative adverse events requiring rapid response: a retrospective case-control study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016;26(7):734-741. doi:10.1111/pan.12922.

Shook DC, Savage RM. Anesthesia in the cardiac catheterization laboratory and electrophysiology laboratory. Anesthesiol Clin. 2009;27(1):47-56. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2008.10.011.

Veenith T, Coles JP. Anaesthesia for magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24(4):451-458. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e328347e373.