CHAPTER 51

Patient Transport

Introduction

With more anesthetics being delivered outside the operating room, the frequency in which patients are being transferred from one location to the next before, during, and after an anesthetic is also increasing. It is often the responsibility of the anesthesia provider to accompany these patients and to ensure their continued medical treatment during these critical transfers. Anesthesia technicians are called upon to assist with transfers, which can be quite challenging due to the medical condition of the patient and the amount of equipment that may need to be managed during the transfer.

Monitoring during Transport

Monitoring during an anesthetic includes assessment of the patient’s oxygenation, ventilation, and circulation. It is important to monitor these same physiologic parameters during a transfer. How they are monitored will depend upon the medical condition of the patient.

Many of the monitors used during transport are introduced in Chapter 31. They are briefly reviewed here.

Ventilation and Oxygenation

Patients transferred to and from the operating room may be spontaneously breathing or require manual ventilation. In either case, the delivery of oxygen to the tissues must be continually evaluated. Patients who are awake and alert may require only visual inspection of respiration. Patients who are deeply sedated, or have significant medical problems, are usually monitored with a pulse oximeter. Pulse oximetry continuously measures the percentage of hemoglobin saturated with oxygen (SpO2) in the patient’s blood. It has proven a reliable method and is readily available on all transport monitors; however, it does have some limitations. Pulse oximetry readings can be affected by excessive movement during patient transport and by low-perfusion states. It is important to assess the accuracy of the readings and waveform when abnormal readings are encountered. If the accuracy is in doubt, other assessments of the patient’s ventilation and perfusion should be immediately undertaken. Another limitation of pulse oximetry is that a drop in saturation is often a late sign of problems with ventilation.

Pulse oximetry assesses only the amount of hemoglobin saturated with oxygen, a key component of oxygen delivery to the tissues. End-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) monitoring provides a more complete assessment of the adequacy of ventilation. This is accomplished through the use of capnography, a measurement of exhaled CO2. The majority of CO2 monitors display a continuous graph of exhaled CO2 throughout the respiratory cycle, along with a numeric value for exhaled CO2 levels. Capnography is available on many transport monitors and is an important adjunct to pulse oximetry. The provider can use capnography to adjust ventilation to maintain CO2 at desired levels (e.g., maintain hyperventilation in a patient with increased intracranial pressure), as well as to alert the provider to an endotracheal tube (ETT) dislodgment or breathing circuit disconnect. During the transport of intubated patients, the provider should monitor EtCO2, chest excursion through direct visualization, or continuous auscultation of breath sounds. In spontaneously breathing patients, CO2 monitoring may be important to detect apnea or hypoventilation during transport. Unfortunately, the availability of capnography on transport monitors is highly dependent on the individual institution. In the absence of EtCO2 monitoring, the practitioner must be able to continuously visualize chest excursion or continuously auscultate breath sounds through the use of a precordial stethoscope. Visualization of chest wall movement requires that the provider have a direct line of sight to the chest, and blankets should not obscure the view of the chest. Unfortunately, chest excursion is not always a reliable sign of ventilation. In the case of a completely obstructed airway, the patient may make respiratory efforts that include chest wall movements, but he or she is not able to inhale or exhale. In this case, there will be an absence of exhaled CO2 or absence of breath sounds on auscultation of the upper airway with a precordial stethoscope.

Cardiovascular Monitoring

The monitoring of blood pressure and electrocardiogram (ECG) are simple and reliable methods of assessing circulation during transport. A standard three-lead or five-lead ECG is available on most transport monitors. Most transport monitors are simplified versions of the more comprehensive monitors used in fixed locations and will not have all of the functionality that the fixed monitors have. For example, a transport monitor may only allow a single lead to be displayed on the monitor at any given time. While ECG monitoring is easy to perform during transport, the provider must be aware that the leads are easily displaced and the waveform is subject to artifact with even minimal movement during transport. Because artifact is common, any possible abnormalities on the ECG waveform should be correlated with other monitors, such as pulse oximetry waveform or an arterial waveform to confirm the presence of an arrhythmia.

Blood pressure is typically monitored through noninvasive or invasive techniques. Noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) cuffs are readily available on all transport monitors. The NIBP should be set to automatically measure the patient’s blood pressure during transport at least every 3-5 minutes or more frequently depending on the stability of the patient. Inconsistent blood pressure readings may develop during transport due to excessive movement, or compression of any part of the NIBP system. Should an aberrant reading be observed, the NIBP should be recycled immediately, but this can often take a minute before the new reading is complete. During that time, the patient should be assessed for signs of adequate circulation, including the presence of a strong distal pulse. In addition, other monitors should be checked to assess the patient if hypotension is suspected, including the ECG rhythm (may indicate an arrhythmia), pulse oximeter (often fails to work if systolic blood pressure falls below 60 mm Hg), and CO2 waveform if available (CO2 levels will fall with a decrease in cardiac output).

It is important to check if the transport monitors and cables are compatible with the fixed monitors (intensive care unit, operating room, and postanesthesia care unit) in use at your institution. If the cabling systems are compatible, the cables can be unhooked from the fixed system and hooked to the transport monitor without detaching the blood pressure cuff, ECG lead wires, or pulse oximeter from the patient. Be careful to return all cables and monitoring equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuff or pulse oximeter probes) to the proper medical unit after transport.

Many patients require continuous assessment of their blood pressure and will have an invasive arterial line that can be monitored during transport. In preparation for transport, the arterial line transducer cable will be detached from a fixed monitor (e.g., operating room monitor) and reattached to the transport monitor. The vast majority of transport monitors will require “zeroing” once the new cable is attached. The arterial line transducer must be affixed to the bed or stretcher at the level of the right atrium and then zeroed to room air prior to beginning transport. After the transducer has been zeroed, the anesthesia technician should confirm that a waveform is present and the transport monitor is providing numeric values for blood pressure. Even if an arterial line will be used to monitor blood pressure during transport, an NIBP cuff should be attached to the patient and the transport monitor as a backup. It is common during transport for the arterial waveform to be altered due to changes in position of the extremity containing the arterial catheter or due to repeated movement of the bed. Due to these factors, providers must have a high index of suspicion about the accuracy of abnormal arterial line readings. When troubleshooting abnormal arterial line readings during transport, always start by assessing the patient (clinical signs of perfusion, NIBP, etc.). Once it has been determined that the patient has adequate circulation, check the patency of the line beginning with the catheter in the patient and following back to the transducer and the pressure bag to ensure that the catheter is not kinked or occluded, tubing is not kinked and does not contain bubbles, connections are tight, stopcocks are in proper position, the transducer is intact, and the transducer cable has been properly attached to the monitor.

Another important consideration is to check the pressure bag. The majority of transducers have a pressure bag to keep the arterial catheter (or other catheter) patent. If the pressure bag has insufficient pressure, the catheter can become occluded. In addition, pressure bags have a drip chamber that must be checked. In order to function properly, the drip chamber must be in the upright position and some of the air evacuated from the drip chamber when priming. During transport, particularly when transferring the patient from the operating room table to the bed, pressure bags can be placed on their side on the patient bed. This may allow air to enter the line, which will interfere with monitoring by entraining air into the arterial tubing or worse embolize into the patient’s arterial circulation (Fig. 51.1). The pressure bag should be hung on an intravenous (IV) line pole or other post connected to the bed, with the drip chamber in the upright position.

FIGURE 51.1. Drip chamber on its side allowing air to enter the monitoring line.

Additional Monitors

Additional pressure monitors such as intracerebral pressure monitors, central venous pressure monitors, and pulmonary artery catheters may be present but often are not observed continually during transport. The anesthesia technician should communicate directly with the anesthesia provider regarding what monitoring is necessary during transport. If any of these pressures are to be monitored during transport, most of the same issues discussed above regarding arterial lines will apply as well.

Patient Care during Transport

Prevention of Hypothermia

The presence of hypothermia increases the incidence of postoperative wound infection and myocardial ischemia. While it is not common to continually monitor temperature during transport, it is important to limit heat loss and the effects of hypothermia during transport. Anesthetized or critically ill patients cannot regulate their own body temperature. The patients must rely on the clinical staff to limit their loss of body heat through convection and evaporation. The loss of heat can be limited during transport by ensuring that the patient is adequately covered with blankets and being vigilant not to expose excess body surface to the air. For patients who are ventilated, the use of a humidified moisture exchanger (HME) can contribute to retention of heat and water vapor lost during mechanical ventilation.

Management of Ventilation

The management of ventilation is a crucial aspect of patient transport. For those patients who will be transported with an ETT in place, the verification of proper placement of the ETT should take place prior to transport. The assessment should include auscultation of bilateral breath sounds and EtCO2 readings. Once proper placement is confirmed, airway equipment for the transport should be checked (oxygen tank with sufficient oxygen, bag-valve-mask or other device for manual ventilation, face mask for possible manual ventilation, etc.). If the patient is transferred from one bed to another, the ETT position should be reconfirmed once the bed transfer is complete.

Intubated patients will require manual ventilation during transport. Some facilities have transport ventilators, but this is the exception rather than the rule. The most common method of ventilating patients during transport is through the use of a manual breathing circuit such as a bag-valve-mask system. Manual breathing circuits consist of a ventilation bag, input for high-flow oxygen, a pop-off valve to prevent the overinflation of the patient’s lungs during ventilation, and some have an adjustable positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) valve. This type of breathing circuit may be used with either spontaneously breathing or ventilator-dependent patients. They do not allow for the delivery of mixed gases or of inhaled anesthetics. Patient transport can be a complicated process and requires coordination to push the bed, manage lines, and manage ventilation. The anesthesia technician may frequently be called upon to “squeeze the bag” and ventilate the patient during transport. The anesthesia technician should discuss the rate and depth of respirations to be delivered or EtCO2 goals during transport with the anesthesia provider.

In some cases, the patient may be on advanced ventilator settings due to severe pulmonary disease, which would preclude the patient from being disconnected from the mechanical ventilator during transport. In these situations, the patient will be transported on a portable ventilator with the goal of preventing an interruption to the ventilatory support. There are many similarities between anesthesia machine ventilators and transport ventilators. They each have an O2 source, delivery tubing, and a control panel. They both are able to deliver high amounts of PEEP in a variety of ventilation modes; however, transport ventilators do not have the capability to deliver anesthetic gases. In addition, transport ventilators generally rely on the oxygen source to drive the bellows of the ventilator as well as deliver oxygen into the circuit. This is important because transport ventilators will use more oxygen than manual ventilation circuits. During transport, you may not have additional oxygen tanks should you exhaust the initial oxygen tank. Verification of a full supply of oxygen and an adequate amount of battery life should be performed prior to transport (Fig. 51.2).

FIGURE 51.2. Transport ventilator that can be operated with tank oxygen.

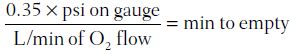

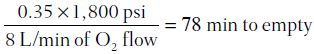

Oxygen supply and the availability of other necessary equipment should be communicated with the provider prior to transport. In the case of oxygen use, the anesthesia technician should have an understanding of how long a given supply of O2 will last. A typical e-cylinder of oxygen at capacity will hold 1,900 psi (660 L of O2). At a flow rate of 8 L/min, a full e-cylinder of oxygen will last about 78 minutes (660 L divided by 8 L/min). The following formula can be used to calculate the remaining number of minutes of oxygen in a given e-cylinder:

For example, if you have a fixed flow rate of 8 L/min to supply your bag-valve-mask during transport and the O2 gauge is reading 1,800 psi,

You will have approximately 78 minutes until the tank is empty. As mentioned above, if you are using a transport ventilator, the oxygen flow requirements can be much greater.

Transfer to and from the Transport Bed

Transferring the patient to and from the transport bed is a critical task that should not be taken lightly. It is important to ensure that all lines are properly prepared prior to any patient movement. The anesthesia technician should ensure that all lines are free and clear and have sufficient slack to allow the patient to be moved. ETTs, urinary catheters, IV lines, chest tubes, and arterial lines have all been pulled out when moving a patient from one bed to another. In addition, patients have sustained injuries during transfers because extremities or the head and neck were not properly supported during the transfer. The anesthesia provider should always verify necessary precautions, such as cervical spine precautions, are in place prior to moving patients. Proper communication between all team members is essential to ensure a smooth transfer. The anesthesia provider has the final say as to when the patient is ready to be moved.

Transport Checklist

The availability and necessity of additional equipment and pharmacologic therapy during transport will vary according to the patient’s condition, but its selection should be based on the need to continue medical therapies and manage potential complication while en route (Fig. 51.3). Because transportation of patients is a critical time in their care and is fraught with pitfalls, the transport team should consider the following items:

FIGURE 51.3. Patient being transferred with multiple lines and infusion pumps demonstrating the logistical difficulty in transporting complicated patients. (Image courtesy of OHSU.)

- There should always be a manual ventilation bag with a face mask present.

- Oxygen supply should be checked, and there should be sufficient oxygen for transport.

- In many cases, a laryngoscope and spare ETT for possible emergency intubation or reintubation should be transported with the patient.

- Will infusion pumps to deliver medications (vasopressors, sedatives, etc.) be necessary for the trip? If so, check the battery supply for all pumps prior to transport (Fig. 51.3).

- Check with the anesthesia provider that all required medications are available for transport (vasopressors, muscle relaxants, sedatives, etc).

- If the transport bed is motorized, check that the bed has sufficient battery power prior to transferring the patient onto the bed.

- Is sufficient help available to manage the transport (manage the bed, manage ventilation, manage lines and infusion pumps)?

- Monitors are set up and operational (ECG, pulse oximetry, capnography), and the monitor has sufficient battery power.

- Pressure lines are connected securely and operational. The pressure bag drip chamber is in an upright position. All lines have been zeroed, have good waveforms, and numeric readings are visible to the provider. The transducer is at the appropriate level.

- IV access is readily available and patent. Are there sufficient amounts of fluids available to deliver medications and give fluid boluses en route if needed?

- The patient is properly padded and secured to the transport bed with all bed rails up, locked, and secured.

- The patient is covered to prevent heat loss and to maintain privacy and dignity.

- If an elevator is needed, arrange for its availability in advance.

- Has the destination team been notified that the patient is ready for transport (intensive care unit, radiology suite, etc.)?

Summary

The transfer of a patient from one bed to another, or from one location to another, is a critical time during the patient’s care. Great care must be taken during all transfers between beds to avoid injury to the patient or dislodgment of lines, drains, or tubes. During the actual transport between locations, the transport team must be able to properly monitor the patient’s condition as well as deliver medical therapies like ventilation or infusion of drugs. Attention to preparation for transport and clear communication between the anesthesia technician and the anesthesia provider has the potential to make this a safe and efficient process.

Review Questions

1. What is a problem that is unique to monitoring with a pulse oximeter?

A) Readings may be affected by excessive movement.

B) Low readings are a late sign of ventilation problems.

C) Readings may be affected by high-perfusion states (high cardiac output or vasodilation).

D) Readings may be affected by patient shivering.

E) They may not be readily available on all transport monitors.

Answer: B

Pulse oximeters continuously measure the percentage of hemoglobin saturated with oxygen (SpO2) in the patient’s blood and are found on all transport monitors. Although pulse oximetry readings are affected by excessive movement and shivering, this is not a problem that is unique to the pulse oximeter: these also affect ECG lead and NIBP cuffs. Pulse oximetry readings are also affected by low (not high)-perfusion states.

2. Which of these would NOT be an initial step when an unusual NIBP reading is obtained during transport?

A) The NIBP should be immediately recycled to get a new reading.

B) The patient should be checked for the presence of a radial or carotid pulse.

C) Vasopressor infusions and IV infusion rates should immediately be increased.

D) The pulse oximeter should be checked for a pulsatile waveform.

Answer: C

Since the NIBP may give unusual readings due to excessive movement, shivering, or compression of any part of the system, the NIBP should be immediately recycled when the monitor displays an unusual reading. It may take a minute to receive a new reading, so during this time, the patient should be assessed for adequate circulation and other monitors should be checked for possible hypotension: ECG (may show arrhythmia), pulse oximeter (often fails to work if systolic BP is <60 mm Hg), and CO2 waveform (will fall with decrease in cardiac output). Vasopressor infusions and IV infusions should be checked rather than reflexively increased. It is very easy to make an error either in monitoring or in vasopressor and IV infusion rates and changes should be made carefully during transport after confirmation.

3. Which of these is not a monitor of a patient’s ventilation?

A) Pulse oximetry

B) Visualization of chest excursions

C) Capnography

D) Auscultation of breath sounds

Answer: A

EtCO2 monitoring (capnography) provides the most complete assessment of the adequacy of ventilation by capnography (measurements of exhaled CO2). Still, EtCO2 monitoring for transport may not be available on every monitor, and in these situations, the provider must have unobstructed and continuous visualization of chest wall movements or continuously auscultate breath sounds. Pulse oximetry is used regardless of whether EtCO2 monitoring is available. However, pulse oximetry monitors oxygenation, not ventilation: a drop in oxygenation can be a late development after a patient has stopped breathing for several minutes.

4. Why is it important that pressure bags be placed with the drip chambers in the upright position?

A) Air might otherwise entrain into the arterial tubing or embolize in the patient.

B) The pressure bag will not function if it is not in the upright patient, so the provider will be unable to assess the patient’s circulation.

C) The pressure bag will not function as well if it is not in the upright position, causing increased risk of postoperative wound infection and myocardial ischemia.

D) The pressure bag will depressurize if it is not in the upright position, causing inaccurate readings.

Answer: A

Pressure bags should always be hung on an IV line pole or other post connected to the bed, with the drip chamber in the upright position. When the bag is upright, air cannot enter the arterial tubing (which exits at the bottom). Air in the arterial tubing can cause inaccurate readings or, worse, can embolize in the patient, causing ischemia in the hand or even stroke. The pressure bag may give abnormal readings if it is not upright (since air bubbles may enter the tubing), but it will not stop functioning if it is in an improper position.

5. An e-cylinder of oxygen has a pressure reading of 1,200 psi prior to transport. How long will this oxygen supply last with O2 flows of 8 L/min?

A) 42 minutes

B) 52 minutes

C) 57 minutes

D) 62 minutes

E) 67 minutes

Answer: B

A full cylinder holds 1,900 psi = 660 L. To find the number of liters of oxygen in 1,200 psi, set up the equation 660 L/1,900 psi = x/1,200 psi and solve for x (multiply 1,200 by 0.35 = 420 L of O2). Divide 420 by 8 (liter flow of O2 during transport) = 52 minutes remaining of oxygen.

6. Identify the true statement:

A) Intubated patients should have mechanical ventilators for transport.

B) Anesthetized and critically ill patients cannot regulate their own body temperature, leaving them at risk for hyperthermia.

C) ETTs, urinary catheters, IV lines, chest tubes, and arterial lines are at risk for being pulled out when moving a patient from one bed to another.

D) Transport ventilators typically consume about the same amount of oxygen as manual ventilation.

E) Invasive arterial line to continuously monitor a patient’s blood pressure is typically used only for critically ill patients.

Answer: C

Transferring a patient from the operating room table to the bed is one of the most hazardous moments in transport. It is imperative that ETTs, urinary catheters, IV lines, chest tubes, arterial lines, and any other monitors, lines, or drains are each accounted for and protected before a patient is transferred. Any can be accidentally pulled out, causing significant harm to the patient. With the exception of some patients with severe pulmonary disease, most intubated patients will be manually ventilated during transport. Although it is true that anesthetized and critically ill patients cannot regulate their own body temperature, they are at risk for hypothermia (decreased body temperature) rather than hyperthermia (increased body temperature). Transport ventilators may use oxygen both for ventilation of the patient and as a driving gas for ventilation bellows, resulting in higher oxygen demands than manual ventilation and possibly requiring an additional tank for transport. Arterial lines are commonly used to monitor surgical patients’ blood pressure (not just the critically ill).

SUGGESTED READINGS

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Standards for basic anesthetic monitoring; last affirmed October 28, 2015. Available from: http://www.asahq.org/quality-and-practice-management/standards-and-guidelines. Accessed May 31, 2017.

Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, et al. Clinical Anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015.

Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Arbous MS, Kuiper SG, De Jonge E. A comprehensive method to develop a checklist to increase safety of intra-hospital transport of critically ill patients. Critical Care. 2015;19:2014.

Frank SM, Fleisher LA, Breslow EJ, et al. Perioperative maintenance of normothermia reduces the incidence of morbid cardiac events: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1997;277:1127.

Kurz A, Sessler DJ, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1209.

Nagelhout JJ, Plaus KL. Nurse Anesthesia. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO; Elsevier Saunders; 2014.