CHAPTER 63

Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity

Introduction

Local anesthetics (LA) are drugs commonly used in anesthesia for the control of pain and/or as the primary anesthetic for surgical procedures. When taking the proper safety precautions, these drugs are generally very safe. Despite this, adverse events from local anesthetic administration do occur. Local anesthetic toxicity is predominantly encountered in situations where large doses of LA are commonly administered (i.e., regional nerve blocks and epidurals). Toxicity from LA occurs from being improperly dosed at the intended site of administration or from unintentional vascular injection directly into the bloodstream. Symptoms of excessive systemic doses range from mild to life-threatening central nervous system and cardiac disturbance.

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST), albeit rare, can be a devastating complication leading to brain injury and death. Early identification and treatment can significantly reduce the morbidity and mortality of LAST; therefore, it is an emergency that requires multiple team members familiar with its management. The anesthesia technician is a valuable team member who should be able to anticipate, locate, and recognize the special medications and equipment needed to treat LAST. The technician should also be prepared to assist in resuscitation, from the specialized protocols of LAST to the basics of prolonged CPR, in the event of a cardiac arrest.

Preparation and Prevention

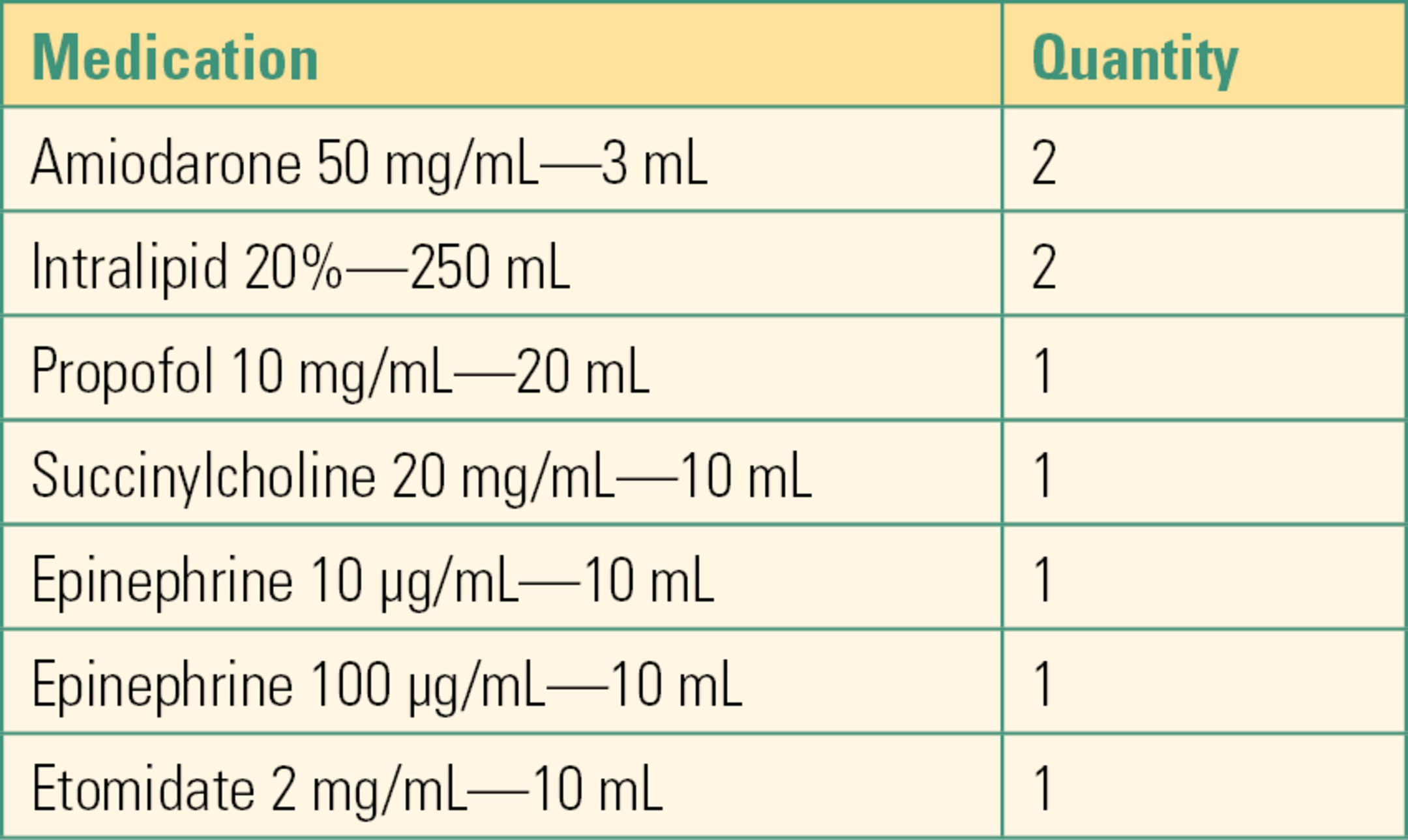

Preparation is tremendously important for managing LAST. Adequate planning includes checking and stocking emergency medications and equipment for airway management and IV access. These items should be readily available in locations (including mobile carts) where LA are commonly administered. A common practice is to assemble a Local Anesthetic Toxicity Kit (Table 63.1) for ease of administration. Regularly checking equipment and replacing expired medications is imperative.

Table 63.1. Sample Contents of Local Anesthetic Toxicity Kit

Primary prevention is critical: many strategies exist. Patients are monitored with American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) standard monitors during and immediately after placement. The lowest dose of local anesthetic needed for anesthesia or pain relief is used. Techniques for careful identification that the needle or catheter is not in a blood vessel may be possible (perhaps nerve stimulation or ultrasound). Incremental injection of 3-5 mL of local anesthetic at a time, with careful aspiration in between each injection looking for blood, and careful observation of the patient to ask about symptoms of local anesthetic toxicity. Epinephrine, which causes an increase in heart rate and blood pressure if injected intravascularly, can be added to the local anesthetic solution. Local anesthetics with lower cardiotoxicity can be used, such as levobupivacaine or ropivacaine.

Detection

Monitors

The proper monitoring modalities are important for the detection of LAST. The recommended monitors consist of the following:

- Standard ASA monitors

- Monitor the patient during and after injection of local anesthetic (toxicity can present as late as 30 minutes post injection)

- Frequent communication with the patient to elicit symptoms of toxicity

Symptoms

Classically, the presenting symptoms of LAST have been described as neurologic, followed by cardiac manifestations. Nonetheless, there is a small portion of patients who present with isolated cardiovascular signs. The typical progression of symptoms is of CNS excitement (agitation, tinnitus, metallic taste, and abrupt psychological change), followed by seizures then CNS depression (coma or respiratory arrest). Cardiovascular toxicity usually manifests later in the continuum. Initially, cardiac toxicity can be hyperdynamic (hypertension, tachycardia, and ventricular arrhythmias) then progress to depression (hypotension, bradycardia, conduction block, and asystole). Simultaneous presentation of CNS and cardiac toxicity can occur, and vigilance for atypical presentations must be practiced. Some LA, notably bupivacaine, are more likely to present with cardiovascular toxicity alone. Midazolam can also blunt the CNS toxicity of LA, so that cardiovascular toxicity may be the presenting sign of LAST.

Timing of symptoms can be variable. They can range from immediate, as expected with direct vascular injection, to delayed (>15 minutes after injection).

Treatment

The treatment of LAST includes airway management, circulatory support, and limiting toxic effects of the local anesthetic. Airway management is of utmost importance, because prevention of hypoxia and acidosis may prevent further progression or even limit the severity of symptoms. These maneuvers include oxygen supplementation, bag-mask ventilation, and/or endotracheal intubation depending on the clinical situation. Seizures should be controlled early because they worsen hypoxia and acidosis. Benzodiazepines are ideal for the treatment of seizures because they have less potential for circulatory depression than other hypnotics (i.e., propofol).

Help should be called for as soon as possible, and preparations should be made to provide Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) should cardiac arrest ensue. Effective chest compressions are critical as these patients are often in a nonperfusing rhythm, and the arrhythmias associated with LAST can be resistant to standard ACLS treatment. Rescuers should rotate so that compressions remain effective. Resuscitation that is not responsive to standard treatment should include cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), just as is initiated in preparation for heart surgery. It is a bridging therapy until the local anesthetic has had time to clear. CPB can take significant time to initiate, so it is reasonable to alert the closest facility capable of providing CPB as early as possible.

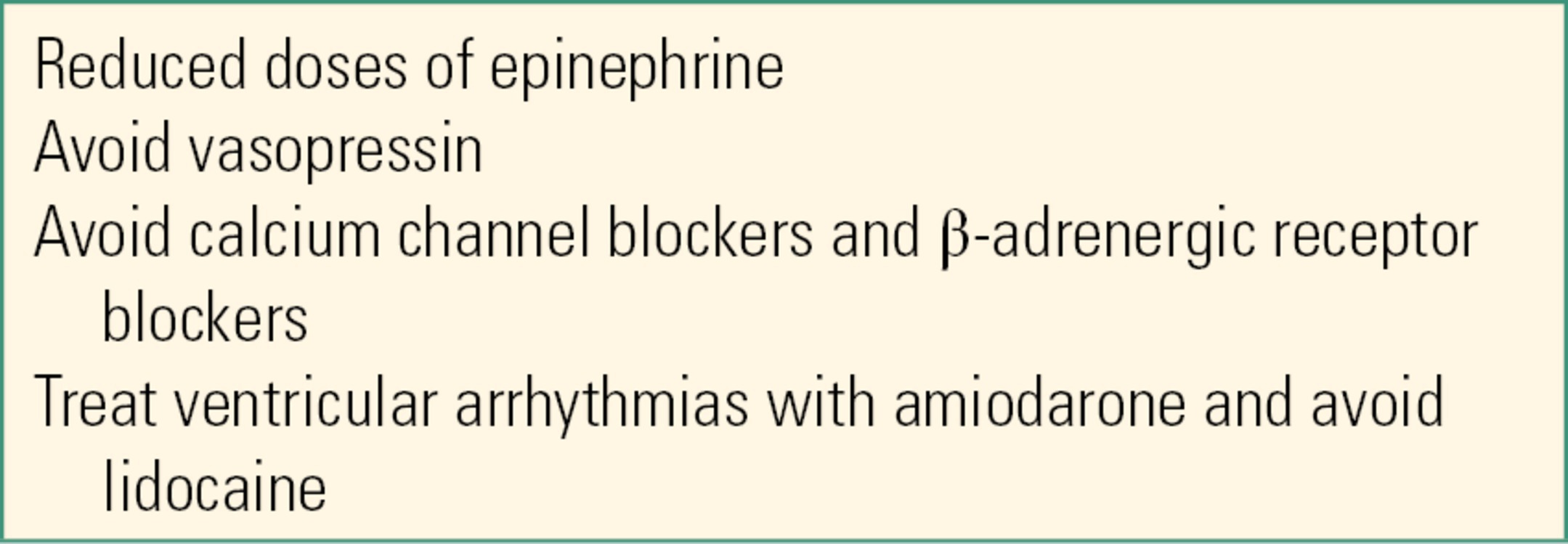

In the event of cardiac arrest, it is important to recall that ACLS is modified in LAST. ACLS (see Chapter 58, Cardiac Arrest) is a broad protocol for any cause of cardiac arrest, primarily researched in the out of hospital setting. In LAST, the cause of the cardiac arrest is known, and rapid, cause-specific treatment should start right away; treatments known to be harmful in this setting should be withheld. For example, lidocaine (a local anesthetic) is a treatment for arrest caused by cardiac ischemia and is a part of standard ACLS—it would be the wrong treatment for someone whose arrhythmia was caused by too much local anesthetic! (Table 63.2). The administration of lipid emulsion is also essential to successful ACLS in LAST and should be considered at the first symptoms of LAST after airway management has occurred.

Table 63.2. ACLS Modifications for Treatment of LAST

Lipid Emulsion Therapy

A 20% lipid infusion is an intravenous lipid emulsion that has been demonstrated to be effective in restoring circulation after LAST has occurred. Lipid emulsion is a critical intervention for LAST and an essential modification to standard ACLS and should be given as early as possible. It’s mechanism is thought to scavenge local anesthetic from high blood flow organs, increases cardiac performance and act as a cardioprotective agent. Lipid emulsion is a low-risk treatment for LAST and should be readily available where local anesthetics are regularly administered (i.e., OR, regional or obstetric anesthesia carts). Propofol contains a small amount of lipid compared to 20% lipid emulsion therapy and therefore cannot serve as a substitute. Lipid emulsion therapy should be continued despite the restoration of circulation because cardiovascular depression can persist or recur after treatment.

Summary

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity treatment is an uncommon but serious emergency. The key to management includes appropriate preparation. The role of the anesthesia technician is therefore critical in saving lives of otherwise low-risk patients for routine, often ambulatory procedures. Preparing the anesthetizing areas with the correct drugs and equipment can make the difference between life and death. When LAST occurs, prompt treatment relies on symptom detection with the proper monitors, and the prompt availability of an intralipid and resuscitation kit. The presentation can vary based on dose and route of administration as well as patient factors. The symptoms range from neurologic to cardiovascular effects with variable severity. Treatment must follow quickly, which involves airway management, control of seizures, and cardiac support. In the event of cardiac arrest, ACLS protocols must be modified, and lipid emulsion infusions can be lifesaving. The anesthesia technician must be intimately familiar with the management of LAST in order to effectively participate as a member of the resuscitative team.

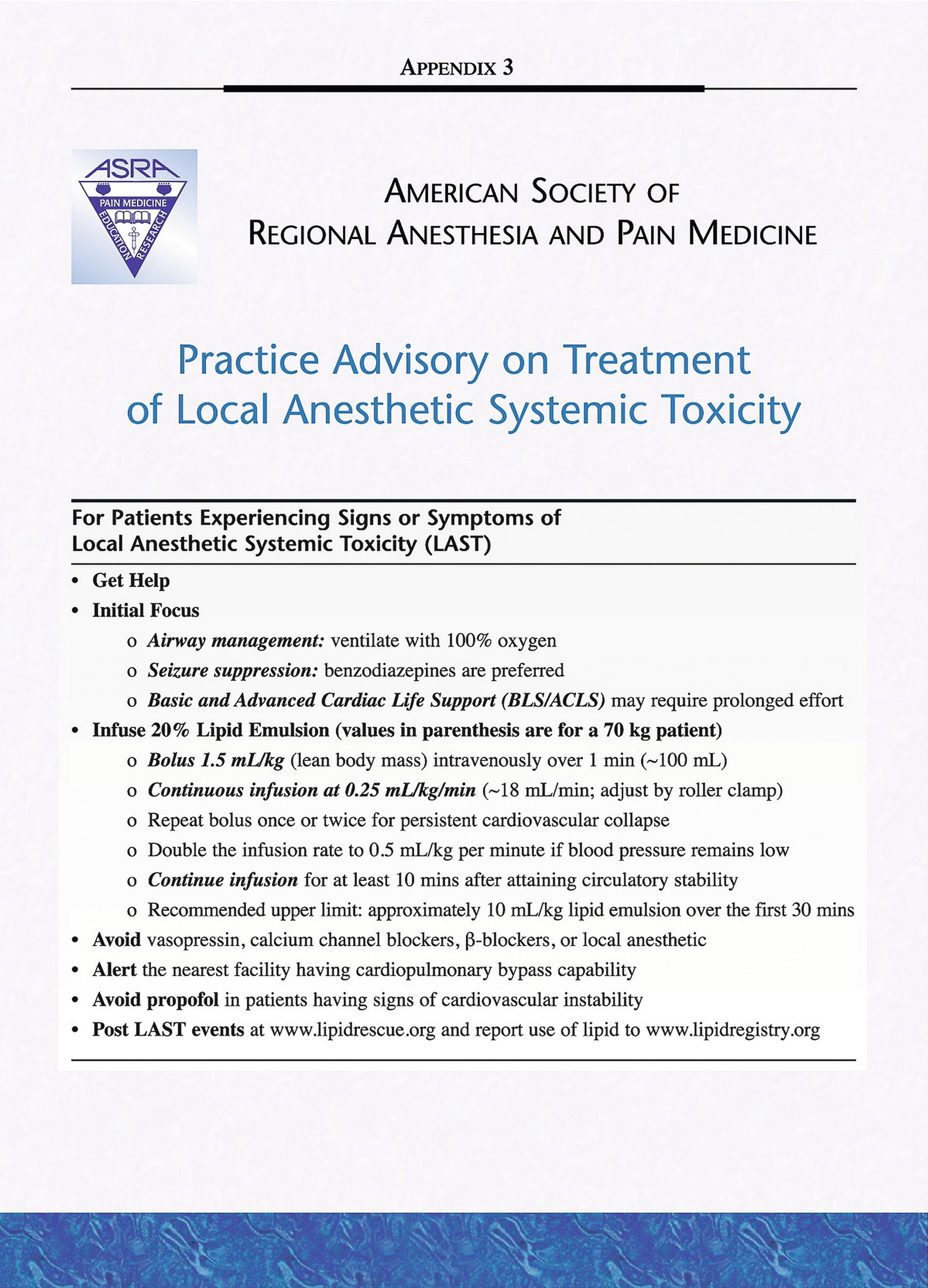

In 2008, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) convened its second practice advisory panel on LAST. The 2010 executive summary of that panel’s findings can be downloaded for free from the ASRA Web site (www.asra.com). A key component of the ASRA practice advisory was the creation of a treatment checklist (Fig. 63.1), a copy of which can also be obtained from the ASRA Web site.

FIGURE 63.1. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Practice Advisory for Local Anesthetic and Regional Toxicity. Copyright 2010 ASRA/LWW. (From Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Fettiplace MR, et al. The Third American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Practice Advisory on Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: Executive Summary 2017. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(2): 113–123. Copyright © 2018 American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.)

Review Questions

1. Which of the following are strategies that the anesthesia technician must employ to properly prepare for a LAST event?

A) Prepare emergency airway equipment (i.e., oxygen source, bag-valve-mask ventilation system, oral airways, laryngoscopes, and endotracheal tubes) in a readily available location.

B) Be aware of crash cart location.

C) Be prepared to assist with cardiac resuscitation.

D) Regularly check and restock medications used in LAST management (i.e., lipid emulsion and ACLS drugs).

E) All of the above.

Answer: E

2. Which of these drugs should NOT be in a local anesthetic toxicity kit?

A) Amiodarone

B) Intralipid

C) Vasopressin

D) Epinephrine

E) Succinylcholine

Answer: C

The local anesthetic toxicity kit should include amiodarone, intralipid, propofol, succinylcholine, ephedrine, and epinephrine. Vasopressin should be avoided in cases of local anesthetic toxicity.

3. It is unnecessary to have 20% lipid emulsion on hand in a procedural area if only epidurals are performed there.

A) True

B) False

Answer: B

It is likely to encounter LAST in situations where large doses of local anesthetics are given, for example, while performing epidural blocks or regional blocks.

4. The presenting symptoms of LAST can vary from one patient to another. However, identify the most typical progression of symptoms, as described in this text.

A) CNS excitement → CNS depression → seizures → hyperdynamic cardiac manifestations → cardiac depression

B) CNS excitement → seizures → CNS depression → hyperdynamic cardiac manifestations → cardiac depression

C) Seizures → CNS excitement → CNS depression → hyperdynamic cardiac manifestations → cardiac depression

D) Seizures → cardiac depression → hyperdynamic cardiac manifestations → CNS excitement → CNS depression

E) CNS excitement → seizures → CNS depression → cardiac depression → hyperdynamic cardiac manifestations

Answer: B

The most stereotypical progression of symptom presentation is CNS excitement (e.g., agitation, tinnitus, metallic taste, and abrupt psychological changes), followed by seizures, CNS depression (e.g., coma or respiratory arrest), hyperdynamic cardiac manifestations (e.g., hypertension, tachycardia, and ventricular arrhythmias), and cardiac depression (e.g., hypotension, bradycardia, conduction block, and asystole). However, it is important to realize that not every patient will show every symptom, and symptoms may progress differently from one patient to another. You should be prepared for cardiac and neurologic symptoms appearing concurrently and for other abnormal presentation of symptoms.

5. You have assisted in the performance of a nerve block in the operating room. If the patient were to develop symptoms of LAST, when would you expect them to present?

A) Immediately

B) Within 5 minutes

C) Within 30 minutes

D) Any of the above

E) None of the above

Answer: D

The symptoms of LAST can range from immediately to half an hour later. It depends on the rate in which the bloodstream acquires the local anesthetic.

6. Which of these is not a treatment that would be used for a patient with LAST?

A) Benzodiazepines

B) Cardiopulmonary bypass

C) Bag-mask ventilation

D) Propofol

E) Calcium channel blockers

Answer: E

Calcium channel blockers should be avoided when treating LAST. In the event of LAST, the patient may receive oxygen supplementation, bag-mask ventilation, and/or endotracheal intubation, depending on the clinical situation. Benzodiazepines are used to control seizures, and in the event of persistent seizures, a small dose of short-acting neuromuscular blocker, such as succinylcholine, should be used. Propofol is NOT used as a substitute for intralipid, and it is contraindicated for intubation in the hemodynamically unstable patient. It is kept in the LAST kit for two reasons: it may be used to terminate seizures if midazolam fails or to facilitate intubation in a stable and semiconscious patient. Succinylcholine is also used in the seizing semiconscious patient to facilitate intubation. Cardiopulmonary bypass is a bridging therapy that gives the local anesthetic time to clear. An essential treatment not listed here is lipid emulsion therapy.

7. Neurologic manifestations are always seen before cardiac symptoms develop in LAST.

A) True

B) False

Answer: B

A small portion of patients present with isolated cardiovascular signs.

8. In LAST, when should cardiopulmonary bypass be undertaken?

A) After resuscitation efforts with standard treatment have failed

B) After the patient has suffered multiple seizures

C) After lipid emulsion therapy has proven unsuccessful

D) As soon as the patient starts presenting symptoms of LAST

E) None of the above

Answer: A

Cardiopulmonary bypass is a bridging therapy that gives time for the local anesthetic to clear. Efforts for cardiopulmonary bypass should be initiated immediately if the patient is unresponsive to resuscitation attempts with standard treatment. Facilitating CPB can be lengthy, therefore early deployment is important.

9. Which of the following is NOT a symptom of local anesthetic toxicity?

A) Headache

B) Tinnitus

C) Seizure

D) Agitation

E) Cardiac arrhythmias

Answer: A

Local anesthetic systemic toxicity typically presents first with neurologic symptoms, which includes agitation, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), metallic taste, and abrupt psychological changes, and is followed by seizures and cardiac symptoms. Headaches are not a symptom of LAST.

10. During cardiac arrest due to local anesthetic toxicity, the anesthesia technician should do the following, EXCEPT:

A) Call for help

B) Be prepared to begin high-quality chest compressions

C) Bring lipid infusion

D) Bring rapid transfusion device(s)

Answer: D

LAST is not associated with the need for rapid transfusion unless there is a concurrent source of blood loss.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Neal J, et al. ASRA practice advisory on local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:152-161.

Weinberg G. Treatment of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;35:188-193.