CHAPTER 58

Cardiac Arrest

Introduction

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart is unable to provide sufficient blood flow to oxygenate the heart and the brain. The heart may or may not have some remaining electrical or mechanical activity, but it is insufficient to produce blood flow or a blood pressure. An awake patient will lose consciousness and stop breathing normally. A cardiac arrest in the perioperative setting is a critical event that will require the coordinated efforts of a team to give the patient the best chance to survive. During a resuscitation, the anesthesia technician must know his or her potential roles on the resuscitation team, what the priorities of the resuscitation are, and what equipment or support the team will require.

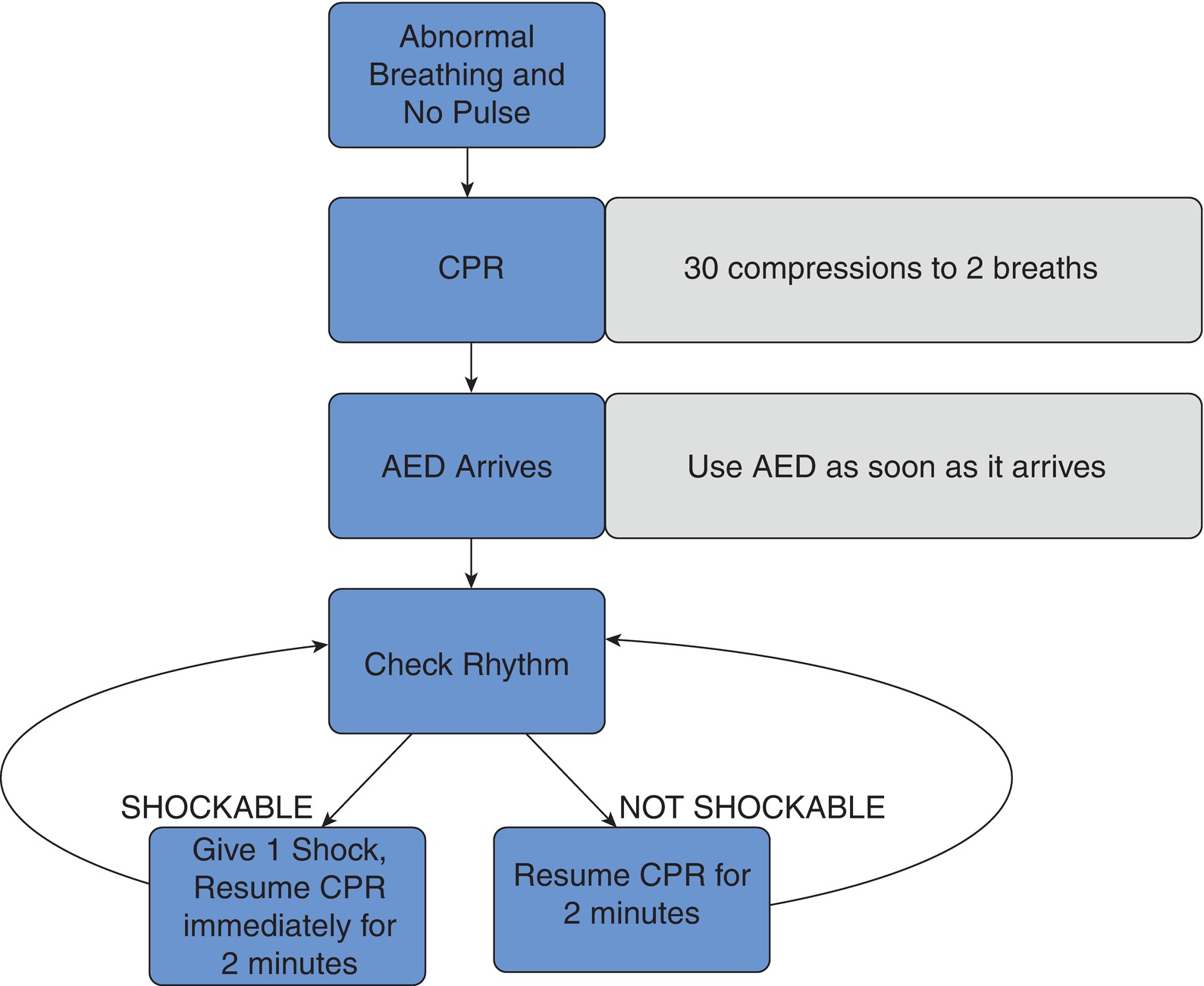

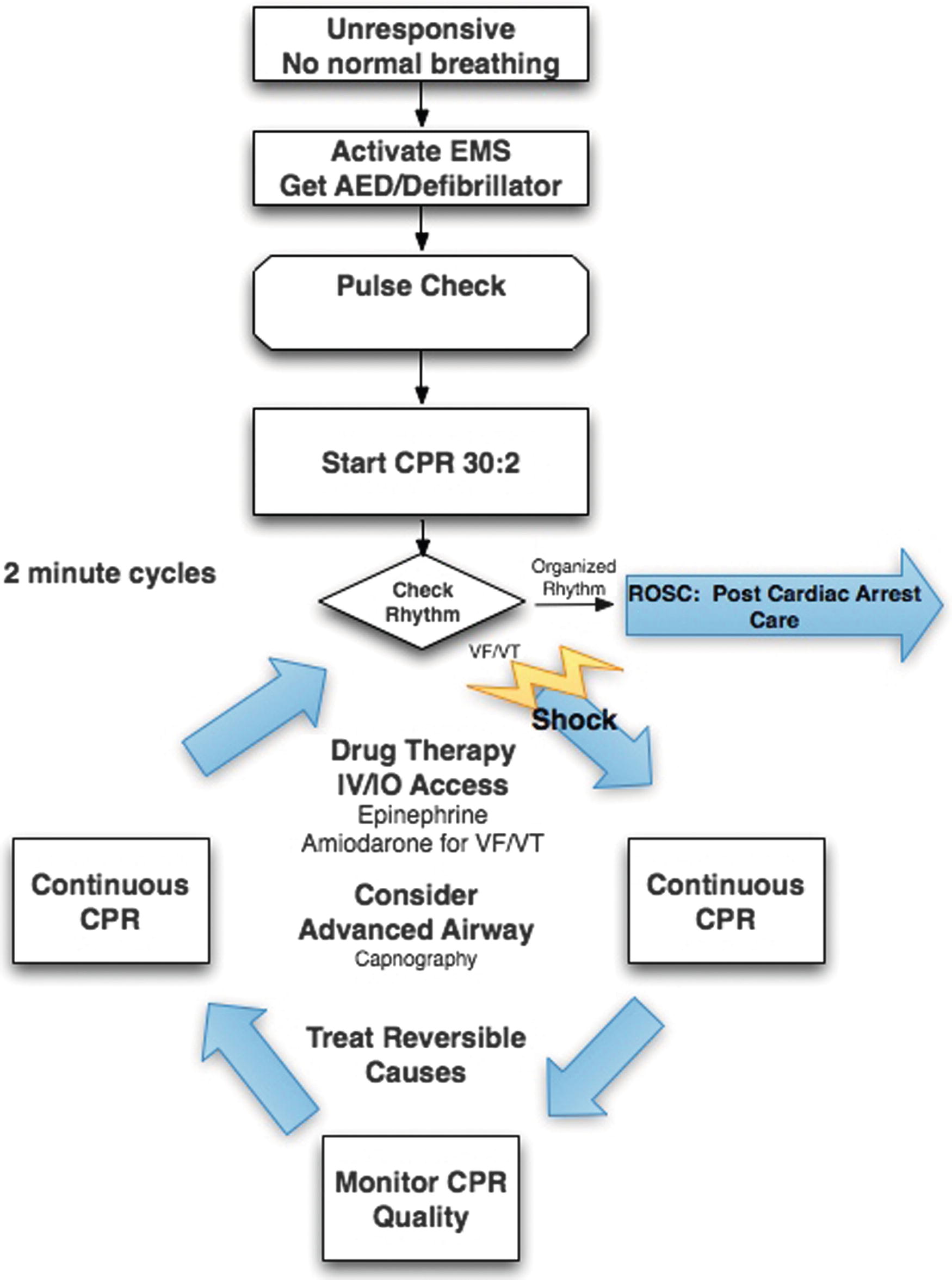

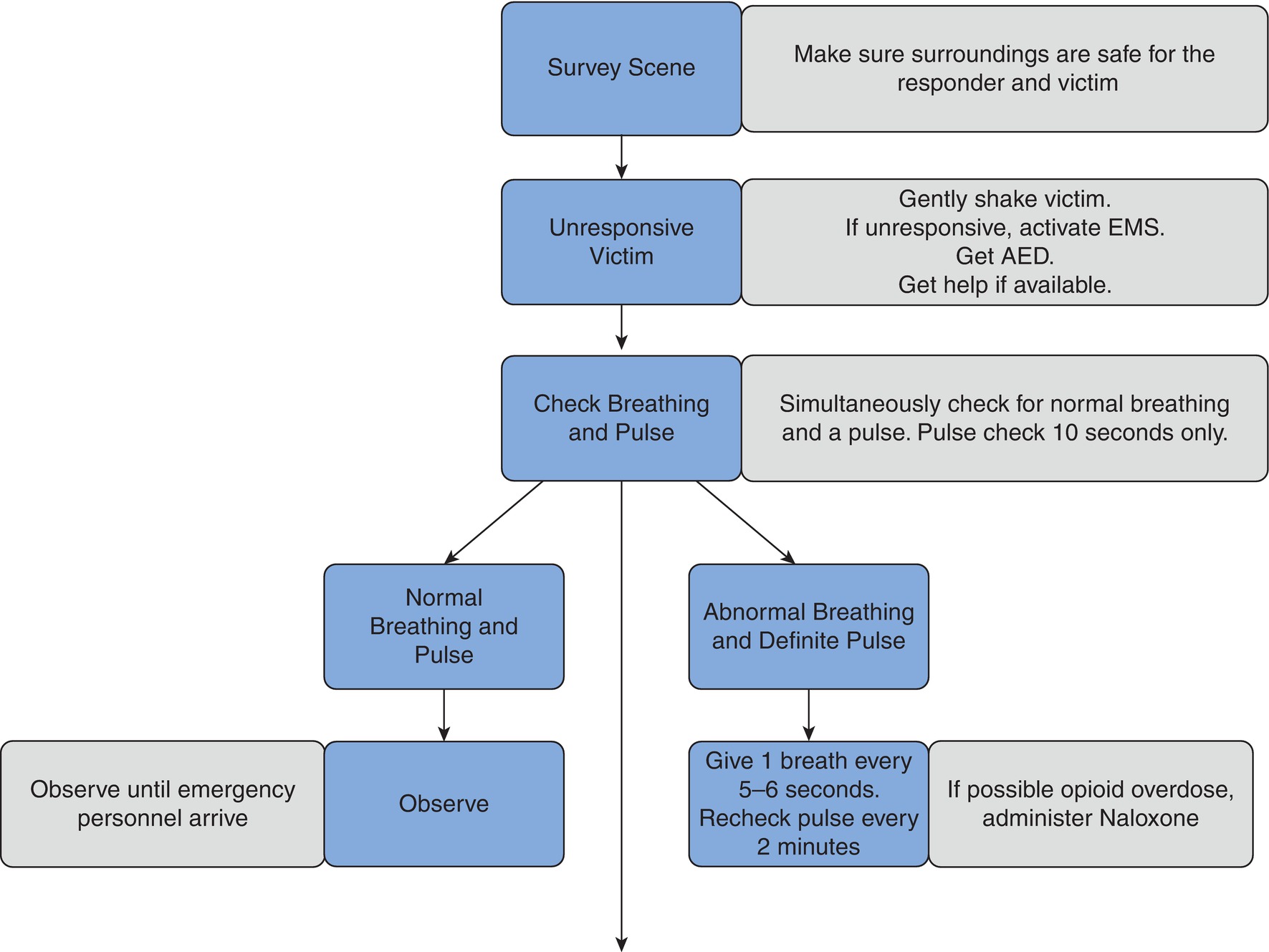

The American Heart Association has produced national guidelines for the care of patients with cardiac arrest. These are developed via extensive literature review, updated every 5 years, and taught via certification in basic life support (BLS) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), which requires renewal every 2 years. BLS covers basic airway management, rescue breathing, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with chest compressions, and use of an automated external defibrillator (AED) (Fig. 58.1). ACLS for cardiac arrest includes advanced airway skills, CPR, AEDs and manual defibrillation, heart rhythm diagnosis, and treatment with medications (Fig. 58.2). Your institution may require you, as an anesthesia technician, to be certified in BLS or even ACLS. Use of these evidence-based team approaches ensures that all teams share a common set of expectations and should provide all cardiac arrest patients the highest-quality care.

FIGURE 58.1. 2015 Adult BLS algorithm.

FIGURE 58.2. 2015 Simplified Adult ACLS pulseless arrest algorithm.

Early recognition and structured team intervention in cardiac arrest are critical in helping the patient survive. Monitors in the operating room alert providers instantly to changes but are also problematic: they commonly produce false alarms, such as a surgeon leaning on a blood pressure cuff or cautery interference with the EKG. These false alarms can produce provider “alarm fatigue” in which providers learn to tune out frequent alarms. Less commonly, monitors are falsely reassuring, such as an EKG that continues even though a patient has no blood pressure or pulse or a monitor processing algorithm that permits a pulse oximeter signal and tone to persist several seconds into an asystolic arrest. Bradycardia, hypotension, and hypoxemia are relatively common, even routine, in anesthesia practice; they may respond quickly to noncritical intervention or rapidly evolve into cardiac arrest.

Prearrest: Initial Response

Health care providers may call for assistance or even call a full code when a patient’s condition is deteriorating. This initiates a formal protocol that rapidly summons resources to the bedside and plans team behavior, even if there is not yet a need for BLS or ACLS. Initial team priorities include the following:

- Bring the code cart (defibrillator, resuscitation drugs, airway equipment).

- Apply defibrillator/pacing pads.

- Provide adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

- Via the endotracheal tube and anesthesia ventilator if in place

- Via face mask or even bag/valve/mask ventilation if not (or supraglottic airway [SGA] if in place)

- Assess for intubation.

- Is this an airway emergency? If so, the AT should assemble airway equipment, including difficult airway cart and cricothyrotomy kit (see Chapter 57, Airway Emergencies).

- Assess for adequate vascular access. If necessary, prepare vascular access equipment.

- Providers may request a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or TTE machine and a skilled TEE operator such as a cardiac anesthesiologist.

- Assess the need for additional help or expertise.

Signs of Cardiac Arrest

The hallmark of cardiac arrest is the loss of a palpable pulse; CPR should start at that point. A pulse oximeter waveform can be a clue to loss of pulse, but is not a substitute for palpation of the pulse, usually at the carotid. An intra-arterial waveform is a better marker but is still subject to artifact: it is very useful, however, to follow during a resuscitation and is often placed in a near-arrest situation or after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Other signs of perfusion that the provider will be looking for are:

- Loss of respiratory efforts and consciousness in a previously conscious patient

- Arrhythmias (very disorganized heartbeats) or very slow or fast heart rates

- Low end-tidal CO2 (this is a sign of very low flow of CO2-containing blood to the lungs)

Cardiac Arrest: Initial Response (Basic Life Support)

Once cardiac arrest is diagnosed, BLS should be initiated (see Fig. 58.1). BLS emphasizes effective chest compressions (“press hard and fast”) and prompt defibrillation. Because there are multiple causes of cardiac arrest in the perioperative setting, the specific equipment and tasks that need to be performed in advanced resuscitation will vary, but the initial goal is to establish effective circulation, maintain ventilation, and shock if necessary. Operating room team priorities will include the following:

- Turn off anesthetics if applicable and administer 100% oxygen. Assess and confirm the airway including attachments of the breathing circuit.

- Hold surgery if possible/place patient supine and expose the chest.

- Begin high-quality chest compressions; the quality of chest compressions is critical to a successful outcome. Goals of effective compressions include:

- In adults, a compression rate of 100 compressions/min with a depth of 2 inches, allowing complete chest recoil.

- Rotate person giving CPR every 2 minutes to maintain vigor of compressions.

- Minimize interruptions (<10 seconds between compressors or for pulse checks).

- Lower the operating room bed, and arrange a step stool if necessary for proper positioning.

- Elbows should be straight and the heel of the hand on the sternum, just above the xiphoid.

- Monitor for EtCO2 greater than 20 mm Hg.

- If an arterial line is present, assess arterial waveform for pulsatility; if not, a pulse may be palpable with compressions.

- Bring the code cart (defibrillator, resuscitation drugs, airway equipment).

- Apply the defibrillator pads as soon as possible and deliver a shock, if appropriate. Deliver additional shocks as indicated in the ACLS guidelines (see Fig. 58.2).

- Prepare to initiate ACLS drug therapy, epinephrine +/− amiodarone.

Cardiac Arrest: Secondary Response

Once initial resuscitation steps are underway (BLS and ACLS), the priority will turn to determining the underlying cause of the cardiac arrest and treating appropriately. The possible underlying cause of the cardiac arrest will dictate which procedures or equipment become a priority.

Common to many situations are:

- Advanced vascular access: The patient may need a central line (for central delivery of vasoactive medications), a large-bore introducer, peripheral IV, or rapid infusion device (if the arrest was hypovolemic). Most patients who undergo cardiac arrest, unless it is very brief, will need an arterial line.

- A pressure transducer bag made up.

- Blood gas sampling to assess ventilation, oxygenation, perfusion, acid-base status, electrolyte, and glucose abnormalities.

- Pumps and vasoactive medications.

- Transport. Will the patient need to go to the OR, to the ICU, to the cath lab? What monitors, pumps, and other devices will the patient need for transport? What will the receiving team need to prepare?

Situations to consider include the following:

- Arrhythmia: Patients with a prior history of cardiac rhythm problems can be at an increased risk for arrhythmias during surgery due to the sympathetic stress of surgery, interactions with anesthetic medications, electrolyte imbalances, or the disease condition for which the patient is having surgery. The priorities for treatment will mostly involve treatment recommendations for defibrillation/cardioversion and drug delivery according to the ACLS guidelines. Be prepared to obtain and process arterial or venous blood gas samples to assess for electrolyte or glucose abnormalities, that providers may request infusions of amiodarone, potassium, and insulin and bolus doses of calcium and magnesium, and that patients may need to travel with defibrillators with pacing capability.

- Myocardial Infarction: Insufficient blood flow to even a portion of the heart (myocardial ischemia) can cause myocardial cell death (myocardial infarction). Either myocardial ischemia or infarction can cause a lethal cardiac arrhythmia resulting in cardiac arrest. TEE may be useful in diagnosis for these patients and can show regional wall motion abnormalities or depression of overall heart function. Other clues are ST elevation on the EKG or new-onset chest pain in the awake patient prior to cardiac arrest. The initial treatment for these patients will usually follow the ACLS guidelines. The patient may have to be intubated during the resuscitation. The patient may require vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, or anticoagulants via infusion, and vascular access equipment and infusion equipment should be readily available. They may also require an intra-aortic balloon pump. If a perfusing rhythm can be obtained after the initial steps in ACLS, the next priority will be to restore coronary blood flow. The patient may require immediate transport to the cardiac catheterization laboratory or the cardiac operating room depending upon the circumstances. They are likely to require a defibrillator and possibly active pacing for transport. They may recover dramatically once a coronary artery is opened either with surgery or in the cath lab.

- Difficult or Failed Airway: Severe hypoxemia associated with inability to maintain an airway and oxygenate the blood can rapidly lead to cardiac ischemia, arrhythmias, (particularly bradycardia), and cardiac arrest. Respiratory causes of cardiac arrest are particularly common in children, and resuscitation protocols for children differ from adult protocols, in part to reflect this (Fig. 58.3) (see Chapter 48, Pediatric Anesthesia). Although one initial response will be to treat the arrhythmia, resuscitation will not ultimately be successful until an airway is established and the blood can be reoxygenated. Equipment that needs to be immediately available will include additional laryngoscopes and blades, an oral airway, a supraglottic airway (SGA), a flexible bronchoscope and video laryngoscope, and an intubating stylet or bougie (see Chapter 57, Airway Emergencies). If an airway cannot be immediately established, the anesthesia provider may wish to prepare for a surgical airway. It will be necessary to prepare an emergency percutaneous cricothyrotomy kit and/or jet ventilation or equipment for open emergency tracheostomy. Although the necessary equipment may be on the code cart or immediately available, it takes time to set up. It is critical for the anesthesia technician to anticipate what equipment may be necessary and have it ready in case it is asked for. If the patient is in the operating room and a surgeon is available or en route, the circulating nurse and surgical technologist may be involved in setup of the surgical airway equipment while the AT sets up or assists with the anesthesiologist’s emergency equipment.

- Hypovolemia or Hemorrhage: Severe hypovolemia can readily cause a cardiac arrest. Once the initial resuscitation steps are underway, be prepared for obtaining additional vascular access and delivering fluid resuscitation. If hemorrhage is the cause, be prepared to send a sample to the blood bank, to obtain blood or blood products (including emergency O negative or type-specific; see Chapter 22, Blood Transfusion), and to initiate rapid transfusion (see Chapter 62, Massive Hemorrhage). A rapid infuser, such as Belmont or Level 1, should be brought to the room and set up immediately. Cell-saver machine can be used in these cases if there are no contraindications (see Chapter 44, Autotransfusion Devices). Be prepared to have a pressure transducer bag for an arterial line placement. Arterial blood gas (ABG) machine should be ready and with the proper daily calibration. During massive transfusion, patients can quickly become cold; hypothermia will then interfere with blood clotting. Thus, make sure fluid warmers are in place and working appropriately right away. Have additional help available to be able to send multiple ABGs, check blood, retrieve medications, etc.

-

Cardiac Arrest Associated with Regional Anesthesia: Many different kinds of regional anesthesia can result in an unintended high or total spinal block if too much local anesthetic reaches the spinal fluid. Rarely, this can occur with a planned spinal anesthetic. Any other regional procedure with needle placement near the spine (epidural, interscalene, even eye blocks, which are near the cerebrospinal fluid in the front of the brain) can result in unintended injection of the local anesthetic into the spinal fluid. Early signs of high or total spinal may be weakness in the upper extremities, shortness of breath, nausea, and anxiety. This can then progress to difficulty with ventilation, respiratory arrest, bradycardia, hypotension, loss of consciousness, or even cardiac arrest. After the initial resuscitation steps, patients will require intubation, ventilation, and cardiovascular support. Fluids and vasopressors (phenylephrine, epinephrine, vasopressin, etc.) may be needed. A promptly recognized total spinal usually responds easily to supportive care (intubation, ventilation, and vasopressor support) and does not progress to an emergency; an unrecognized one is fatal.

The most serious complication after regional block or epidural anesthesia injected with local anesthetics is cardiac arrest following an unintended intravascular injection (see Chapter 63, Local Anesthetic Toxicity). Cardiac arrest due to local anesthetic toxicity can be particularly hard to treat because it causes dysrhythmias that are less responsive to traditional ACLS maneuvers such as defibrillation and antiarrhythmic drugs. An infusion of lipid (20% lipid emulsion) has been demonstrated to reduce the amount of local anesthetic interfering with cardiac cells. Patients may then be successfully resuscitated even after prolonged performance of CPR. If a cardiac arrest is precipitated by local anesthetic toxicity, the anesthesia technician should immediately locate the lipid infusion. Most institutions maintain this important drug in their regional anesthesia carts. - Anaphylaxis: Major allergic reactions to drugs or other agents can release large amounts of histamine into the circulation and can produce cardiac arrest. Many of these patients will require intubation due to airway swelling, bronchospasm, or cardiovascular collapse. The mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis is epinephrine (see Chapter 59, Anaphylaxis). Epinephrine is the most potent cardiac stimulant, a bronchodilator that can counteract bronchoconstriction and a vasopressor that can counteract the severe vasodilation that occurs with anaphylaxis. Other treatments include antihistamines, fluid administration, steroids, and bronchodilators. Anesthesia technicians encountering anaphylaxis should make epinephrine immediately available, as well as the other treatments. Airway equipment, including advanced airway equipment for patients with difficult airways from swelling, may be required. The AT should be prepared to send relevant labs (such as serum tryptase and histamine) and be prepared to transport these patients to the intensive care unit with monitoring, infusions, and ongoing large-volume fluid resuscitation.

-

Other Conditions Often Associated with Cardiac Arrest: There are several other conditions that may contribute to a cardiac arrest, including drug toxicity, severe electrolyte imbalances, pulmonary emboli (gas, thrombus, debris, fat), tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade, anesthetic overdose, etc.

The key for the anesthesia technician in all of these situations is to help perform the initial resuscitation, anticipate needed equipment, and keep eyes and ears open. By paying close attention, the anesthesia technician should understand what the cause of the cardiac arrest might have been. This will help the technician to better anticipate what might be needed during the resuscitation. One essential resource that may be needed is additional personnel, as multiple tasks may need to be done at once: leave the room for additional equipment, assist with procedures, perform point of care laboratory testing, and rapidly set up specialized technology such as bronchoscopes, ultrasound, or monitoring devices. Whether experienced or junior, the wise AT will actively recruit all available colleagues in this critical situation (“all hands on deck”) rather than attempt to perform all tasks alone. Nursing, surgical, anesthesia, and even intensivist or other visiting teams are likely also to be performing simultaneous tasks, though one team leader should be directing clear communication (see Chapter 56, Simulation and Crisis Resource Management).

FIGURE 58.3. 2015 Pediatric Advanced Cardiac Life support algorithm (PALS).

Postresuscitation Care

Once there is return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), the postresuscitation phase begins. The patient will need to be prepared for transport to the ICU once the medical condition allows. Care should be taken to make sure that the transition to the ICU goes as swiftly and smoothly as possible (see Chapter 51, Patient Transport). Anticipate that post cardiac arrest, patients may need ventilation and monitoring during transport; avoid disruption of lines or infusions. They may need a defibrillator or even an intra-aortic balloon pump or rapid infusion device. Make sure that obstacles from the OR to the ICU are cleared and that an elevator is ready to receive the patient. In the ICU, after safe handoff from the operating room team, the immediate goals of postresuscitation care are to maintain ventilation and oxygenation, to optimize cardiovascular function to provide blood flow to organ systems critically vulnerable to ischemia (heart, brain, kidneys), and to protect the patient’s neurologic function. Once in the ICU, it is likely that blood will need to be drawn for various lab studies including chemistries, blood gas analysis, complete blood cell count, etc. Radiology studies may also be necessary upon arrival in the ICU for diagnostic purposes or line placement. In addition to treating the medical conditions that caused the cardiac arrest, special therapies may need to be applied, including therapeutic cooling for some patients.

Summary

In summary, responding to a cardiac arrest requires a team approach. The anesthesia technician plays an important role, anything from performing high-quality chest compressions to assisting with a difficult intubation to anticipating the need for equipment and supplies. The more you know about the priorities in the assessment and treatment of cardiac arrest, the better you will be at meeting the needs of anesthesia providers, other resuscitation team members, and, most importantly, the patient. The initial phase of a resuscitation will focus on the performance of BLS and ACLS. Subsequent therapies will be guided by an assessment of the cause of the cardiac arrest.

Review Questions

1. What should an anesthesia tech do during a cardiac arrest?

A) Know his or her scope of practice as defined by accrediting agencies, AHA certification, and local institutional policy.

B) Try to think about what the cause of the arrest might be.

C) Anticipate equipment needs.

D) Be prepared to participate as a member of the team during resuscitation.

E) All of the above.

F) A, C, and D only.

Answer: E

Understanding the cause of the cardiac arrest will help the AT anticipate what equipment and help might be needed. An airway event will need different therapy and equipment than a massive hemorrhage, and while making a diagnosis is not within the scope of practice of the AT, situational awareness, observation of events described in this chapter (e.g., cardiac arrest in a patient who has just had a regional block), and attention to the statements of the team leader should prompt the AT to think about what might be happening, so that he or she can prioritize actions appropriately (e.g., asking “should I get the lipid infusion” and calling for another AT to help prepare equipment for intubation).

2. Which of the following is NOT a common cause of cardiac arrest in perioperative settings?

A) Malignant hyperthermia

B) Massive hemorrhage

C) Anaphylaxis

D) Failed or difficult airway

E) Arrhythmia

Answer: A

Although all of the above are potential causes of cardiac arrest in the perioperative setting, malignant hyperthermia is very uncommon and occurs on the order of 1:10,000 to 1:100,000 patients having surgery (see Chapter 60, Malignant Hyperthermia). The anesthesia technician is much more likely to encounter a myocardial infarction or failed airway in the perioperative setting than malignant hyperthermia.

3. A code is called in the OR in a patient who is semiconscious and gasping for breath. Your most important role is to

A) Go to the OR hallway and get the code cart.

B) Prepare to begin chest compressions.

C) Assist the anesthesia provider as requested in assembling equipment for mask ventilation and intubation.

D) Assemble additional vascular access equipment which you anticipate will be needed.

Answer: C

A patient who is gasping for breath is not yet in cardiac arrest: this is a prearrest situation. All OR team members should be prepared to assist with BLS skills like chest compressions or bringing the code cart, and the OR will soon fill with additional people. Only you, however, as the AT, are familiar with the intubation equipment and able to assist the anesthesia provider, who is preparing to intubate prior to arrest and asking for help. This is not the time to leave to assemble additional equipment for the advanced stages of resuscitation, though it may well be needed soon.

4. During cardiac arrest due to local anesthesia toxicity or unintended intravascular injection of local anesthetics, the treatment of choice is:

A) Lipid infusion

B) Vasopressin

C) Amiodarone

D) Epinephrine

E) Defibrillation alone

Answer: A

Lipid emulsions have been demonstrated to reduce the amount of local anesthetic interfering with cardiac cells and are a common emergency drug found on regional block carts.

5. When cardiac arrest is due to hypovolemia or hemorrhage, which of the following is least likely to be used by the anesthesia provider?

A) Fluids

B) Blood products

C) Forced-air warmer

D) Rapid transfusion device(s)

E) Defibrillator

Answer: E

Arrhythmia requiring defibrillation is not often caused by hypovolemia—the cardiac arrest of hypovolemia or massive hemorrhage happens initially because the heart is beating or functioning normally but it has little or nothing to pump out: it is sometimes called “pulseless electrical activity” and a defibrillator will not help as the heart rhythm is normal. Fluids and blood via a rapid infusion device and large IV access are the treatment of choice. These, however, can cool the patient too much, so that a forced-air warmer is needed.

6. Which of the following is a critical element of basic life support (BLS)?

A) IV access

B) Chest compressions that are hard, fast, and effective

C) Intubation

D) Epinephrine

E) Intermittent pulse checks

Answer: B

All of the above can be important to resuscitation. An essential component to BLS, however, is maintenance of circulation with effective chest compressions that are hard, fast, effective, and not interrupted. The others are maintaining an open airway, providing ventilation, and early defibrillation. Inserting an advanced airway and IV access and administering epinephrine, all important, are part of ACLS. Basic life support provides oxygen to the brain while these things are happening. Intermittent pulse checks are done between compressions but should not interrupt compressions for greater than 10 seconds.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Ellis A, Day J. Diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. CMAJ. 2003;164:307-312.

Neumar RW, Link MS, Otto CW, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support—2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(suppl 3):S729-S767.

Weinberg G. Treatment of local anesthetic systemic toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35:188-193.