CHAPTER 62

Massive Hemorrhage

Introduction

Massive hemorrhage is the loss of a critical amount of blood volume and poses an immediate threat to life. It is among the most serious surgical emergencies and needs to be treated immediately and aggressively in order to avoid severe complications. It is crucial that everyone taking care of the patient perform tasks quickly, communicate clearly, and work as a team toward the common goal of resuscitation. Here, we will discuss how to prepare for massive hemorrhage, the equipment and supplies that are needed for treatment, and the role of the anesthesia technician in the management of massive hemorrhage.

Preparation

There are two basic scenarios in which massive hemorrhage develops. First, it can be anticipated to occur during a regularly scheduled surgery. In this case, all the necessary equipment, intravenous (IV) access, and blood products can be obtained prior to actual blood loss. Hemorrhage can be anticipated with certain types of cases as well as with certain patients. The cases that are most prone to hemorrhage are large vascular cases, like open abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA or “triple A”), resection of large tumors around the internal organs or pelvis, procedures on or around the liver, procedures near the blood vessels of the brain, and all but the most minor surgery in the chest. Patients particularly prone to massive bleeding are those taking anticoagulant medications or those with coagulopathies, platelet dysfunction, or low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), liver disease, or poor nutritional status. While surgical bleeding is usually steady and controlled, there is a high risk of rapid blood loss during these cases.

The second scenario is unanticipated hemorrhage, which is much more difficult to manage because the supplies, IV access, and blood products available may be insufficient for rapid resuscitation. For example, unanticipated hemorrhage may occur from a vascular injury during a surgery in which minimal blood loss was anticipated. Massive hemorrhage may also present in a trauma patient who has just arrived to the operating room (OR) via the emergency department, or in obstetrics. In these cases, the anesthesia provider will immediately need assistance, and the anesthesia technician is a critical member of the team.

Delegation of Responsibilities

The key to a successful resuscitation is to quickly establish adequate IV access, replace the volume that has been lost on the surgical field, and gain control of the hemorrhage. This requires a coordinated team-based approach with clear communication between the surgical and anesthesia team. What type of vascular access is needed, who will perform the procedures, what blood products are available or need to be ordered, how much bleeding will be anticipated, when can control of bleeding be expected, and what are the team priorities? These are all important items to discuss quickly so that everyone, including the anesthesia technician, shares a common set of expectations. These priorities will help the care team assign roles. If the anesthesia team is occupied with managing the airway or anesthetic, the surgical team can be tasked with starting venous access lines or an arterial line. The anesthesia technician should be prepared to help the surgical team members with procedures and equipment as well as the anesthesia team.

Anesthetic Management

Anesthetic care starts with establishing an airway and obtaining IV access. Critically injured trauma patients may arrive in the OR with neither. If an airway is in place, its position and effectiveness will need to be confirmed. The team will need to verify that existing IV access functions properly, or place new lines, so that drugs and fluids can be given. Gaining peripheral access may be difficult in the setting of hemorrhage because the patient will be hypovolemic, hypotensive, and likely cold, all causing peripheral vasoconstriction. The anesthesia technician should be prepared to assist by gathering vascular access supplies: catheters of multiple sizes, tourniquet, tape, gauze, alcohol swabs, IV tubing, and fluid (see Chapter 36, Vascular Access). Larger IVs are preferred because they can be used later for large-volume resuscitation, but smaller IVs may be all that is possible during the initial resuscitation because they are easier to place. Anesthesia technicians may further assist by looking for veins or uncovering and positioning an extremity. If IV access cannot be established, intraosseous access (which requires specialized equipment but is placed quickly) can be obtained. If there is time, additional IV access and an arterial line may be placed before induction of anesthesia. Arterial access can be challenging in the hypovolemic or hypotensive patient and may require additional equipment such as ultrasound or specialized wire–assisted placement. If the patient is already anesthetized when the crisis arises, the anesthesia provider may need to adjust the anesthetic by turning infusions down or off or changing ventilator settings. The anesthesia provider may need infusions of vasopressors to maintain blood pressure. The anesthesia technician should be ready to rapidly retrieve these drugs, along with infusion pumps, advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) drugs, and the code cart in case the situation worsens.

Large-Bore Intravenous Access

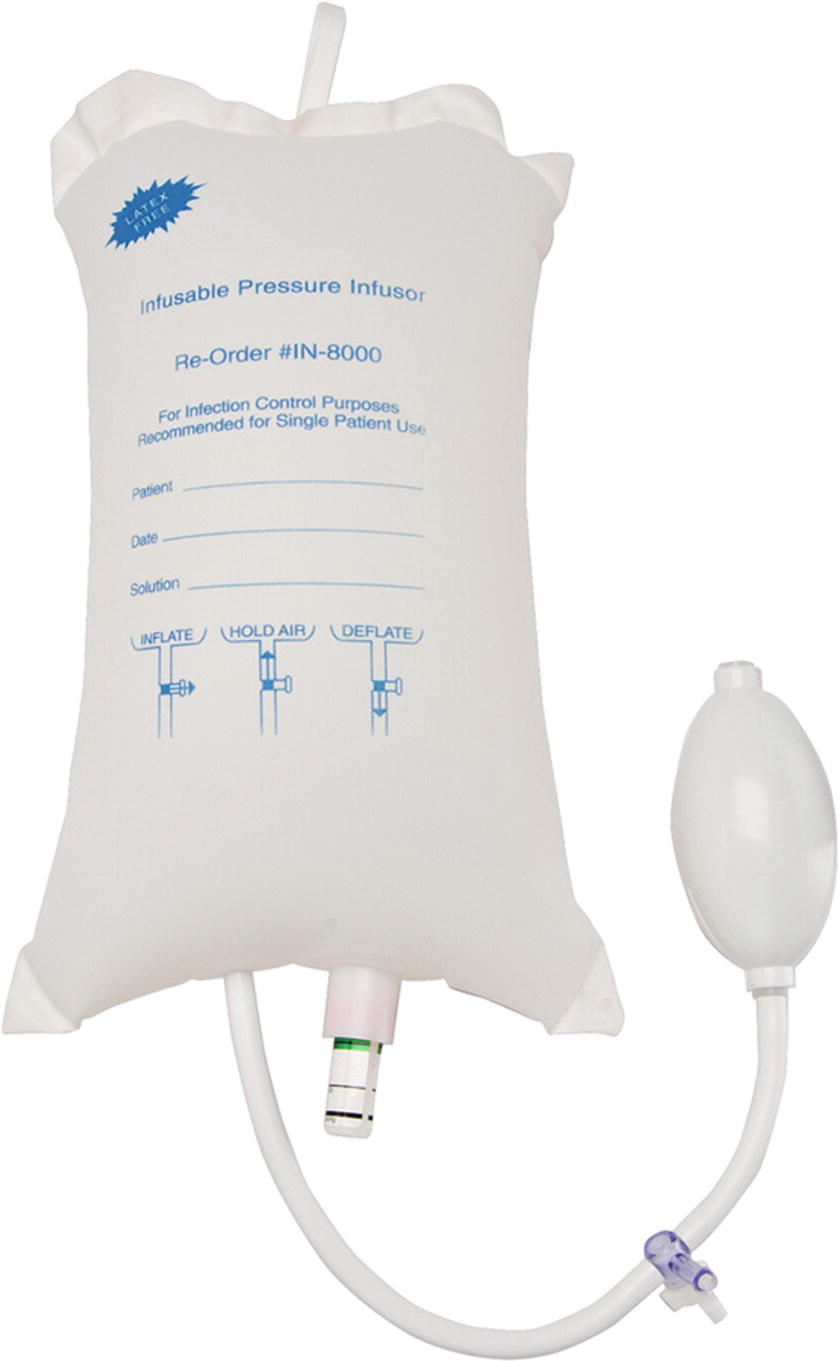

As discussed above, the first priority is to establish initial IV or intraosseous access to induce anesthesia and administer resuscitation drugs. Most patients have at least one working IV, placed either in the field, emergency department, or preoperative area for scheduled cases. These are often small bore, which are adequate for giving drugs, but their size limits the flow rate and the ability to give large-volume fluid resuscitation and blood transfusions. Pressure infusers or “pressure bags” can be used to increase flow through these IVs. A pressure bag system typically consists of a mesh or plastic sleeve with an inflatable nylon bladder (see Fig. 62.1). The fluid bag is placed in the sleeve, and the bladder is inflated with a hand pump so it squeezes the bag. Some models use alternative methods for pressurizing the bladder. Pressurized systems must be constantly supervised. A pressure bag can infuse air intravenously (air embolism), which can be lethal. Any air in the IV bag will be above the fluid level, but once all fluid is forced out, air will be forced into the tubing and make its way to the patient. This must be prevented either by eliminating all air from the bag prior to use or by delegating that someone constantly watch and maintain these devices. Pressurized bags can also infuse fluids, blood, or medication into cannulae that are not intravenous, which can cause tissue damage.

FIGURE 62.1. Inflatable nylon bladder that can be used to pressurize IV bags. IV, intravenous.

Another method to increase the flow rate through an IV is manual compression of the bag. If there is a surplus of people to help, they can squeeze the bags of IV fluid by hand. Alternatively, simply raising the height of the IV fluid bag as high as possible will increase the infusion rate. While not as effective as pressure bags or manual compression, this frees up hands and reduces the risk of air embolism. While these measures alone are not sufficient to treat massive hemorrhage in the long run, these simple maneuvers can greatly increase the rate of fluid administration until adequate access is obtained.

For large-volume fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion, large-bore IV access must be obtained. Large-bore peripheral catheters (14 or 16G) have a large diameter and short length and can often be quickly inserted. They can be placed during surgical-site preparation or during surgery. However, placement of large IVs requires that the patient has adequate peripheral veins, which are often very difficult to cannulate in the setting of hypovolemia. The anesthesiologist also needs access to the extremities, which may be difficult during surgery.

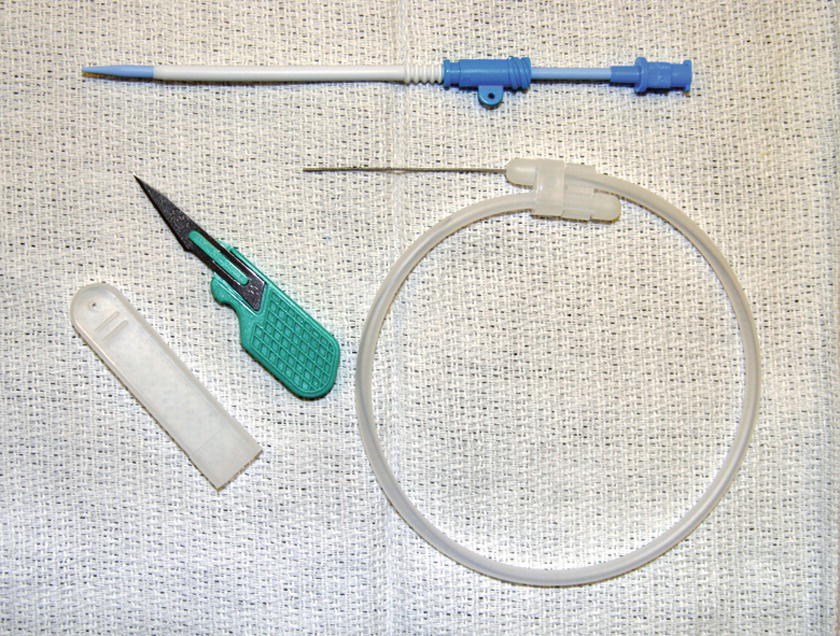

Another option for large bore peripheral venous access is the rapid infusion catheter (RIC) (see Fig. 62.2). Known also as a trauma line, the RIC is a large catheter (7.0 or 8.5 Fr) that is placed under sterile conditions, typically in the antecubital fossa (see Chapter 36, Vascular Access). RIC lines can be used to infuse up to 500 mL per minute when used with a rapid infusion system (see below) and under pressure. Disadvantages of RICs are that placement requires a few additional steps (kit preparation, sterile skin prep, guide wire, and skin nick) compared to regular peripheral IVs. Since they are most often placed in the antecubital fossa, they can easily become kinked and occluded if the elbow is bent.

FIGURE 62.2. Rapid infusion catheter setup.

Peripheral lines all have the disadvantage that they are more prone to failure. These catheters are shorter and may be dislodged from the vein. The veins into which they are placed are small and can be damaged with cannulation. These veins may not be large enough to handle the high flow rates of rapid infusion. Venous drainage of the extremities can be impaired, which will decrease the infusion rate. Peripheral lines can also infiltrate, which means the infusion is going into the tissue around the vein. If these problems go undetected (particularly a risk if the line is pressurized rather than run to gravity) and the line is still used, the limb can be significantly damaged. Also any fluid, blood products, and drugs that are given through an infiltrated line will be ineffective. To overcome these limitations, central venous access may be necessary.

Central venous access may be placed for administration of fluids, infusion of vasoactive drugs, and also for monitoring purposes. There are several locations for central line placement. Those veins most frequently used are the internal jugular (IJ), femoral, and subclavian (SC) veins. The IJ vein remains a favorite among most anesthesiologists because of improved safety with ultrasound guidance and ease of access in most patients. Regardless of the location, however, the equipment, setup, and line placement procedure are largely the same. The anesthesia technician should prepare sterile gowns, sterile gloves, caps, masks, skin prep solutions, IV sets and fluids (usually a blood administration set), flush solutions, central venous catheter insertion kits, and an ultrasound machine. Always have additional drapes and insertion kits available in the event of faulty equipment or if sterility is broken. The anesthesia technician should ask the anesthesia provider how they would like the patient and bed positioned for line placement. This may include moving the breathing circuit tubing to one side of the patient, turning the patient’s head (being careful not to extubate the patient), placing the patient in Trendelenburg (head down tilt), raising the height of the bed, and positioning the ultrasound machine. In the setting of massive hemorrhage, the main priority is usually delivery of a large volume of fluid and blood products, so a Cordis-type introducer kit will often be utilized to maximize infusion capacity. It may be necessary to place a second central line at the same site (“double-stick” technique).

Intravenous Fluids, Blood Products, and Infusion Devices

It may seem strange, but in some bleeding patients, the first priority may NOT be replacement of blood and fluids, or raising the blood pressure. Trauma teams may focus on controlling the source of bleeding, protecting lungs, warming patients, and preventing the later intensive care unit (ICU) complications that ultimately cause these patients’ death, like sepsis, injured lungs, and blood clotting problems. Thus, often the trauma team or even an elective surgery team will determine that the most important goal is to stop bleeding, in which case the patient’s blood volume and pressure may be low for a period of time while the source of bleeding is identified and repaired. Once this happens, patients can be aggressively resuscitated. Another focus of this approach may be instituting antibiotics and/or tranexamic acid (“TXA”, an antifibrinolytic drug that helps prevent blood clotting abnormalities), which the anesthesia technician may be asked to obtain promptly.

Once resuscitation is under way, and large-bore IV access has been obtained, especially if bleeding is ongoing, the patient may need blood volume replaced quickly. If blood products are not immediately available, isotonic saline solutions may be used for intravascular volume expansion until blood is available. Whichever fluid is preferred at your institution (e.g., normal saline or lactated Ringer solution), have plenty of it on hand as it may still be used even after the blood products arrive. Anesthesia providers will vary in choice of fluids (crystalloids, albumin, fresh frozen plasma [FFP], red blood cells) during resuscitation once massive bleeding is under way, guided by lab results and the clinical situation; the optimal combination of resuscitation fluids and blood products continues to be studies and debated. There will also be institutional variability with respect to blood banking and transfusion protocols (see Chapter 22, Blood Transfusion). Become familiar with your institution’s protocol. Most institutions now have a “Massive Transfusion Protocol” which provides for activation of the appropriate resources to obtain pre-determined amounts of blood products quickly, whether for a trauma, OR, or obstetric case. Variables in blood banking may include, but are not limited to, site of blood storage, amount of blood immediately available, quantity of blood available for emergency transfusion (uncross-matched blood or O-negative blood), citywide supply, and time to obtain additional blood products (Red Cross). Every institution should have a protocol in place to ensure that the blood transfused is matched specifically for the patient receiving the blood product. Checking to make sure that the blood has been designated for the correct patient will reduce the likelihood of a patient receiving the incorrect blood type, which is the most common transfusion-related error. You should be properly certified by your institution in blood handling.

In addition to packed red blood cells (PRBCs), other blood components are also depleted during a massive hemorrhage. These components can be diluted from resuscitation IV fluids or PRBCs given, or they can be consumed by the body as clots are formed. Fresh frozen plasma is typically transfused during a massive hemorrhage. FFP contains clotting factors, which are proteins in the plasma that allow the blood to clot. As the name indicates, this product is frozen for storage. Before it can be transfused it must be thawed, which takes 30 minutes. Therefore, it must be ordered at least 30 minutes before it can be given. Many institutions will transfuse FFP at a ratio of 1:1 with PRBCs; some (especially before bleeding is massive) may give a unit of FFP after three or units of PRBCs have been given. Get to know your massive transfusion protocol.

Platelets are another blood product needed in massive hemorrhage. Like clotting factors, they are essential components for the formation of a strong clot, and without them, the bleeding cannot stop. Those in the body are lost in the hemorrhage, diluted with IV fluid given, and consumed as clots form. Platelets are fragile and are permanently deactivated by cool temperatures, so they are stored at room temperature. They should never be put in a cooler with ice. They should never be given with rapid infusers because the shear forces created by pressure and high flow rates break up and inactivate platelets. Remember that increasing the height of the bag can increase the infusion rate.

If the hemorrhage is severe enough, these products will need to be given as fast as possible; this can be accomplished with the use of rapid infusion devices. The anesthesia technician should be able to rapidly prepare and operate common rapid infusers including the Belmont Rapid Infuser (Fig. 62.3) and the Level 1®. These devices perform two functions. First, they warm the fluid being infused. Second, they infuse the fluid under high pressure (the Level 1) or at a set rate (between 2.5 and 750 mL per minute), which can be set by the anesthesia provider (e.g., the Belmont). It is essential that you become familiar with the setup of this equipment before it is needed (see Chapter 36, Vascular Access). In some cases, personnel dedicated to the management of massive hemorrhage may be assigned with this sole responsibility. Working in concert with the anesthesia team, they will operate the rapid transfusion system, order and prepare blood products, and often check labs that guide the continued resuscitation and transfusion.

FIGURE 62.3. Belmont Rapid Infuser System. Reservoir with 3 L capacity and flows up to 1,000 mL/min of warmed fluid, with air alarms. Limitations include both adequate vascular access and adequate personnel support to obtain, check, and hang blood products. (Photograph used from Belmont Instrument Corporation, Billerica, MA, with permission.)

Autologous blood recovery, whereby the patient gets transfused with his or her own blood, is another option to treat massive hemorrhage (see Chapter 44, Autotransfusion Devices). Using suction catheters, blood is aspirated from the surgical field as it is lost and transferred to a blood salvage device, or “cell saver,” where it is washed and spun to extract the red blood cells. These cells are warmed and transfused back to the patient. Only blood initially collected into the cell saver can be salvaged, so the cell saver must be brought in when hemorrhage begins; blood already in canisters cannot be recovered. Autologous blood recovery has contraindications, notably contamination with debris of various kinds.

Warming is a critical step. Hypothermia causes the functional proteins in the body not to work, including the proteins that maintain normal functioning of all organs, including maintenance of blood pressure and clot formation. It is a major contributor to mortality in patients with trauma. A bag of blood fresh out of the cooler at 4°C transfused into a patient is like adding a bag of ice to the patient’s blood stream. Take the extra moment to set up the warmer before giving blood.

Additional Considerations

During massive hemorrhage and resuscitation efforts, the patient can develop a myriad of additional problems, such as coagulopathies, metabolic and electrolyte derangements, and acid-base imbalance. (See Chapter 22, Blood Transfusion.) The anesthesia provider will frequently need labs to guide management; these labs include arterial blood gases, complete blood cell count (CBC), blood chemistry, and coagulation panel. When needed, the anesthesia technician should collect and analyze these samples quickly. The unstable hemodynamics that accompany massive hemorrhage can also result in end-organ dysfunction, such as renal failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, nonperfusing arrhythmias, or cardiac arrest. The code cart, which has supplies for ACLS, should be immediately available.

The patient will remain in the OR until the hemorrhage is controlled and the patient is adequately resuscitated. Following this, they will most likely remain intubated and be taken to the ICU either because of the initial cause for hemorrhage or due to complications resulting from the hemorrhage and resuscitation. All the equipment for patient transport will need to be gathered; this is reviewed in Chapter 51, Patient Transport. These transports can be particularly challenging because the patient will likely have multiple IVs and an arterial line, need mechanical ventilation, and be receiving multiple infusions of vasopressors or sedation as well as additional blood products. With blunt trauma, the patient may require spinal precautions, making transfers from table to bed more difficult as well.

Massive hemorrhage carries with it a high mortality rate; you may be involved in the care of a patient who dies. Whether the resuscitation is successful or not, it is emotionally exhausting for everyone involved. After the case, it is important to have a debriefing session with those involved to discuss the technical aspects of management; what went well, and what needs improvement. These sessions can also help all team members manage the emotional toll that accompanies cases like these.

Equipment for Massive Hemorrhage

In accordance with the priorities outlined above, the following equipment may be necessary during a case of massive hemorrhage:

- Airway equipment

- IV access supplies (catheters, tape, skin prep, tourniquet)

- Specialty access kits (intraosseous, RIC, central line)

- Blood administration Y-type tubing (multiple), blood filters

- IV fluids (most often normal saline)

- Pressure bags

- Central line supplies (multiple kits of different varieties, gowns, gloves, prep, drapes, ultrasound machine)

- Rapid infuser, and priming

- Cell saver, and priming

- Arterial line supplies (kits, multiple catheters, gloves, prep, tape, wires, and ultrasound)

- Multiple transducer setups with pressure tubing and flush system

- Blood gas and lab draw tubes

- Infusion pumps

- Vasopressors (several syringes or bags for infusion of each)

- ACLS drugs, code cart

- Transport equipment

Review Questions

1. Which of these surgical cases is NOT high risk for developing massive hemorrhage?

A) Cases in the chest

B) Vascular cases involving large blood vessels

C) Procedures involving the liver

D) Patients taking anticoagulants

E) All of the above

Answer: E

The chest is a “high real estate” area. The working space tends to be very crowded, and the surgeons are working right next to the largest vessels in the body. An injury to the inferior/superior vena cava, or worse, the aorta, can lead to massive blood loss within seconds. With large vascular cases, there is always the possibility of significant blood loss because the surgeons are intentionally violating the largest vessels in the body. The liver is a very vascular organ; it has a large blood supply, and it also contains a large amount of blood within it. A cut surface of liver will bleed profusely, and stopping the bleeding can be difficult because there is not a single bleeding site but rather the entire cut surface will bleed. Patients undergoing liver surgery also very likely have some degree of liver dysfunction. This often results in a coagulopathy, which compounds the extent of bleeding.

2. During massive hemorrhage, peripheral IVs are of little or no use.

A) True

B) False

Answer: B

Large-bore peripheral IVs (14G, 16G) and RICs can be used to infuse blood products at very high rates. In fact, they will flow at rates much higher than many central lines, with the exception of the Cordis introducer. Remember that the flow rate is increased by a large inner diameter but slowed by the greater length of the catheter. Most central lines have lumens that are both narrower and much longer than peripheral IVs. Peripheral lines can also be placed much more quickly than central lines, so if the hemorrhage was unanticipated, the speed with which peripheral lines can be placed is vitally important.

3. Which of the following fluids and blood products are needed to resuscitate a patient with massive blood loss?

A) PRBCs

B) FFP

C) Platelets

D) Crystalloids (normal saline, lactated Ringer solution)

E) All of the above

Answer: E

Red blood cells carry oxygen, which is the single most important function of the blood. If blood lost were replaced only with crystalloid and other blood products, there would be a very low concentration of red blood cells (hematocrit), and the blood’s ability to carry oxygen would be severely impaired. Both FFP and platelets are needed during resuscitation because clotting factors (contained in FFP) and platelets are both consumed and lost during massive bleeding. Without replacing them, the blood will not be able to form a strong clot to prevent continued bleeding. While crystalloids are the fluid of choice for replacing minor blood loss, once the amount of bleeding is high enough (this amount is different for every patient, but roughly half a blood volume for a healthy adult), blood products become the priority.

4. During a massive hemorrhage, if a fluid warmer is not working properly, replacing it is not a high priority, since warming fluid does not have a proven benefit.

A) True

B) False

Answer: B

During resuscitation efforts, it is very important to maintain the patient’s body temperature at 36°C-37°C. Blood products are stored either on ice (red blood cell, FFP) or at room temperature (platelets), both of which are very cold relative to body temperature. Warming fluid cannot significantly warm a patient, but the rapid infusion of cold fluids can drop the body temperature rapidly and significantly, which will impair the blood’s ability to clot and can lead to metabolic disturbances, electrolyte and acid-base derangements, and even cardiac arrest. If a fluid warmer is not warming properly, it needs to be replaced immediately. Methods for actively warming the patient include the use of forced air heating blankets and increasing the temperature of the OR.

5. Which of the following should not be given through a rapid infuser?

A) Platelets

B) FFP

C) Red blood cells

D) Cell saver blood

E) Normal saline

Answer: A

Platelets are vulnerable to shear forces and should be given at room temperature and via gravity, not warmed or under pressure. Other blood components, and crystalloid, can be given through the rapid infuser.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Cotton BA, Au BK, Nunez TC, et al. Predefined massive transfusion protocols are associated with a reduction in organ failure and postinjury complications. J Trauma. 2009;66:41.

Johansson PI, Stensballe J. Hemostatic resuscitation for massive bleeding: the paradigm of plasma and platelets—a review of the current literature. Transfusion. 2010;50:701.

Lier H, Krep H, Schroeder S, et al. Preconditions of hemostasis in trauma: a review. The influence of acidosis, hypocalcemia, anemia, and hypothermia on functional hemostasis in trauma. J Trauma. 2008;65:951.

Lundsgaard-Hansen P. Treatment of acute blood loss. Vox Sang. 1992;63:241.

Mannucci PM, Federici AB, Sirchia G. Hemostasis testing during massive blood replacement: a study of 172 cases. Vox Sang. 1982;42:113.

Mohan D, Milbrandt EB, Alarcon LH. Black Hawk Down: the evolution of resuscitation strategies in massive traumatic hemorrhage. Crit Care. 2008;12:305.

Yuan S, Ziman A, Anthony MA, et al. How do we provide blood products to trauma patients? Transfusion. 2009;49:1045.