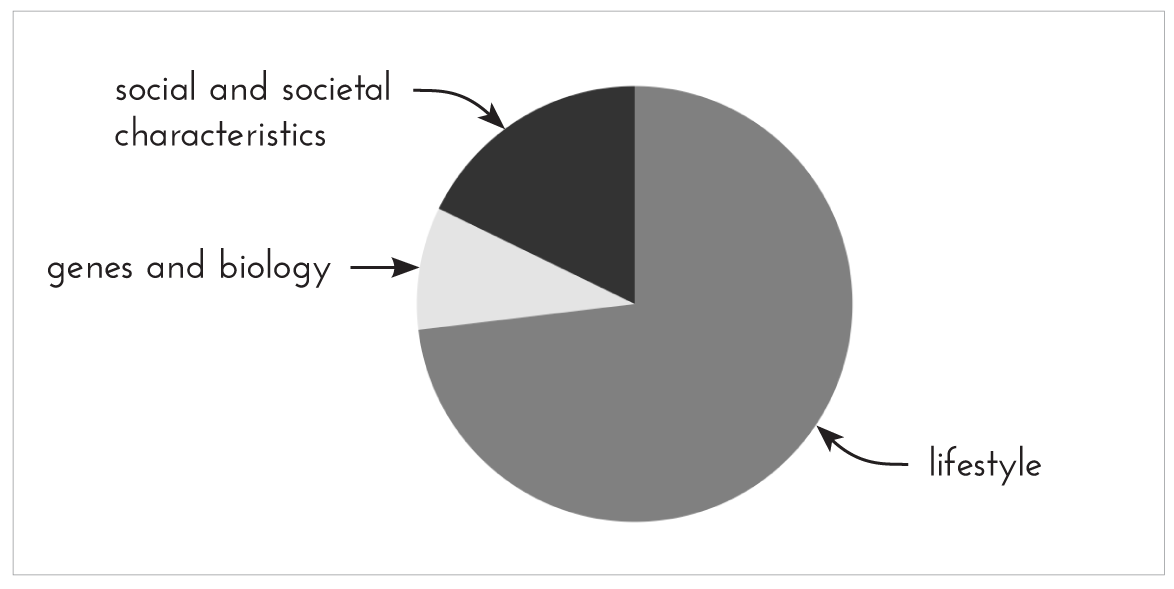

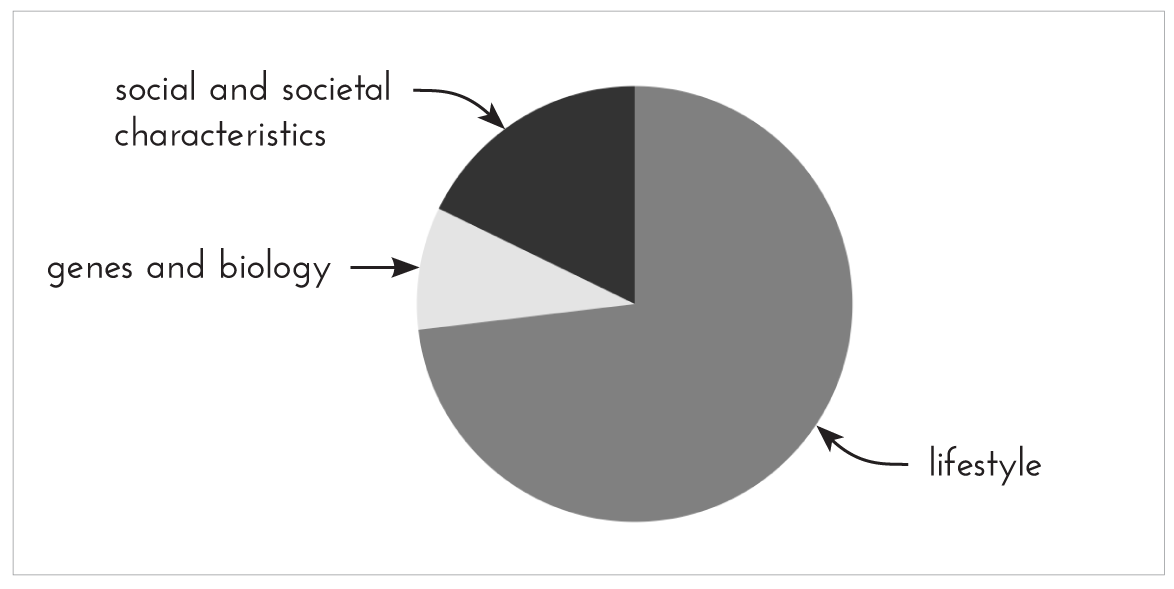

Figure 1. What people think determines population health

‘The causes of the causes are the social determinants of health and they influence not only lifestyle, but stress at work and at home, the environment, housing and transport.”

MICHAEL MARMOT

If I asked you to draw a pie chart showing the different factors that affect our health, how many segments would there be? Which would be the largest?

I sampled one hundred random people on social media and asked them to do just this. Here is the amalgamation of their suggestions:

Figure 1. What people think determines population health

I think this is a pretty accurate representation of what our average person (who hasn’t studied public health) thinks. A heavy emphasis on nutrition and exercise, with not many other factors getting a look in.

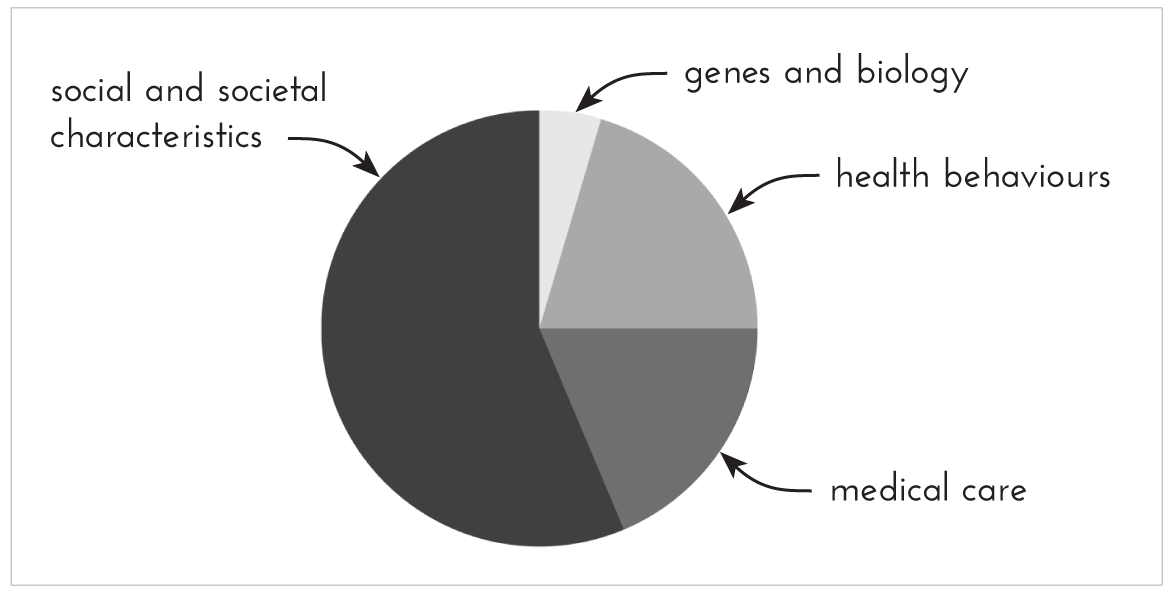

Compare this with the CDC* pie chart, which echoes WHO data.

Figure 2. Actual determinants of population health

Obviously these are estimates, not exact numbers, but they provide an interesting insight. Health behaviours – which would include factors such as nutrition, exercise, smoking, alcohol and so on – account for less than a quarter of the population health. The most significant variable here is socio-economic factors. Even within the ‘health behaviours’ category – the only one we really have significant control over – there are factors beyond nutrition that are important to address, such as sleep.

How much sleep do you get, on average, a night? Is a good night’s sleep a priority for you, or more of a luxury? Hopefully after reading this you’ll realise just how important sleep is for our health.

During sleep, you cycle between periods of REM (rapid eye movement) and non-REM sleep, both of which are incredibly important and needed for good health. A typical sleep cycle takes around ninety minutes, so during a good night’s sleep (seven to nine hours are recommended for adults) you’ll go through around four to six cycles. You generally get more non-REM sleep earlier in the night, and more REM sleep closer to waking. During sleep, you’re not just resting, your body works to restore your immune, nervous, skeletal and muscular systems.

Sleep is vital for our survival. We know this, because of a rare condition called fatal familial insomnia. Sufferers struggle with sleep, until over time they are unable to sleep at all. Life expectancy from that point onwards is a mere matter of months. There is no treatment.

There are two main factors that determine sleep: the circadian rhythm and adenosine. Our bodies have a natural circadian rhythm, which is set to around twenty-four hours. Not exactly twenty-four hours, but in that area. Seeing as a day is exactly twenty-four hours, this means the brain needs anchoring to essentially reset its internal clock back to exactly twenty-four hours each day. The best way to achieve this is through exposure to natural light. Social interactions and regular mealtimes can also help with this.

The brain communicates the cycle of day and night through releasing melatonin. This hormone is released into the bloodstream at night to signal that there is a lack of daylight and therefore it’s time to sleep. It doesn’t cause sleep, but signals to the body to begin the process of sleep and feeling sleepy.

Adenosine is released whenever you’re awake, and builds up over the course of the day, resulting in sleep pressure. In the evenings, melatonin and adenosine are both high, which is why you feel most sleepy then. Adenosine is then broken down while you sleep so you feel refreshed when you wake up – unless you don’t sleep for long enough and the breakdown process isn’t complete. In that case you accumulate a ‘sleep debt’, which will build up until the adenosine is cleared. When you reach for your coffee first thing in the morning to wake you up, the caffeine blocks adenosine receptors so that adenosine can’t bind, meaning your brain perceives there being less adenosine than is actually the case – and you feel less sleepy than you should! Once the caffeine is metabolised, you often experience a ‘caffeine crash’ as you’re hit with all the adenosine that’s been building up and hiding behind a wall of caffeine.

When it comes to food and sleep, it’s recommended not to eat too late as large meals just before bed are linked to reduced sleep quality. Ideally give yourself a good few hours between your last big meal and going to sleep. A small dessert or a snack if you’re hungry won’t have a big impact on your sleep quality; in fact, if you’re hungry it’s better to eat something as hunger will also prevent you from getting to sleep as easily.

Lack of sleep also has an impact on your food intake and food choices. When you’re sleep-deprived (around six hours of sleep or less), your ghrelin levels increase while leptin decreases, so not only do you not get the normal ‘I’m full’ signals from leptin, but the ‘I’m hungry’ signal from ghrelin is amplified.42 This means you’ll feel hungrier than if you’d had a good night’s sleep and are more likely to overeat. You’re also more likely to reach for comfort foods, or more specifically, high-sugar, high-fat foods or salty snacks. Sleep deprivation is sometimes just a fact of life, and the occasional one-off isn’t going to cause you many problems, but if you’re regularly not getting enough sleep it disrupts your body’s normal appetite hormone signalling, which makes it harder for you to be in tune with your body.

Alcohol, while appearing to help you get to sleep more easily, actually disrupts sleep. Alcohol has a sedative effect, which is a different state to sleep and more like anaesthesia. Alcohol affects sleep in two main ways: it fragments it so that you briefly awaken many times throughout the night (although it’s highly likely you don’t remember any of them) and it suppresses REM sleep.142 This results in you not being as well rested as you’d expect, and having reduced memory function.

Overall, the effects of insufficient sleep are pretty damaging: depressed immune system, disruption of blood sugar levels, reduced concentration, impaired memory and increased risk of cancer, heart disease, stroke, dementia, depression and anxiety. Chronic sleep deprivation is also one of the major contributors to development of type 2 diabetes. In essence, shorter sleep time means a shorter lifespan.143

In the case of many of these diseases, but particularly heart disease, the effect of sleep deprivation is mediated by the fight-or-flight response. Sleep deprivation activates the sympathetic nervous system to the point where it’s in overdrive, as well as increasing your body’s cortisol level, which constricts your blood vessels, raising your blood pressure. Non-REM sleep, on the other hand, calms the sympathetic nervous system. You can really see this on a population level when the clocks change between GMT and BST. In spring, when the clocks move forward an hour, many people lose an hour of sleep and there is a spike in heart attacks the following day. In autumn, when the clocks move back and many people gain an hour of sleep, the opposite effect is observed, and we see a drop in heart attacks.144 And that’s the effect of just one hour of sleep.

I’m not saying all this to scare you, but just to give you that little push to make sleep more of a priority if you haven’t already done so. For some bizarre reason, our society values and encourages sleep deprivation under the guise of being oh so busy and productive and always grinding. But you’re far more likely to be productive, learn more, be healthier and be a nicer human being to those around you if you sleep well.

IN THE LAST WEEK |

YES/NO |

Have you fallen asleep within 5 minutes?

|

|

Did you frequently wake up at night? |

|

Have you slept on average for 6 hours or less per night? |

|

Have you felt like you could fall asleep again before midday? |

|

Could you function relatively normally in the morning without coffee? |

|

The more questions you answered ‘yes’ to, the more likely it is that you’re sleep-deprived. Hopefully I’ve convinced you that you should do something about that.

A quick reminder of the stress response: we respond to stress with a ‘fight or flight’ reaction, with our brains sending signals to our bodies via the HPA axis and the SAM system. The HPA axis increases adrenaline in the body and the SAM system increases cortisol, both hormones, both of which lead to a range of changes in different bodily systems. Acute stress can be beneficial and activate responses in the body that help you get through that stressful situation, whereas prolonged chronic stress leads to wear and tear on the body’s regulatory systems. This can weaken any beneficial responses to stress, weaken the immune system and lead to increased risk of disease. The experience of chronic stress takes a serious toll on someone, both physically and psychologically.

Although we’ve been aware of a link between stress and health for a while, exactly how stress gets ‘under your skin’ and leads to poor health was mostly unknown. This is partly because scientists have only recently developed the necessary tools to look at the biological processes that link experiences of stress with disease.

Now we know that stress is linked to the onset of diseases such as heart disease, cancer and colds, as well as speeding up the process of ageing. We also know it’s shown to aggravate conditions such as asthma, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), arthritis, respiratory diseases, skin disorders and diabetes, and leads to symptoms such as headaches, muscular pain, stomach pain, insomnia and general tiredness.

The inflammatory response is an incredibly primitive mechanism in your body – elements of it existed even before the development of the nervous system. The stress response evolved from and is intricately linked to the inflammatory response, as stress can promote and encourage components of the immune system that are involved in inflammation. This means that stress hormones initiate an inflammatory response in the body. Almost all immune cells have receptors for one or more stress hormones.

Most people think of inflammation as the body’s response to physical injury and infection, so when you get a cut or burn, for example, you’ll notice the area feels warm and raised – it’s slightly inflamed. But inflammation also plays a role in several of the biggest diseases, thereby making inflammation a common link between stress and different conditions.

Stressors can enhance the risk of developing infectious diease, and they can also cause infectious illness episodes to hang around for longer, especially the common cold. I think we can all remember times where we were under stress, and then managed to catch a cold either during or just after a stressful experience. I know from my own experience that every year I would catch a bad cold a day or two after my university exams were finished. That’s no coincidence. That anecdote is backed up by research. A cold that you catch when you’re stressed often forces you to relax and spend some time resting. If you don’t, the cold tends to last a lot longer and is harder to get rid of.

Stress, by activating the sympathetic nervous system and the HPA axis, causes the release of various stress hormones, which cause a higher heart rate and blood pressure, damage to artery wall linings, and an inflammatory response in the arteries. If this stress is repetitive or chronic, it can lead to atherosclerosis – a build-up of material in the arteries, potentially leading to blockage, which can trigger a heart attack or stroke.145 Chronic life stress is now considered to be an important risk factor for heart disease, alongside diet and exercise.

Work-related stress is the most widely studied chronic life stress relative to heart disease. There are several aspects of the work environment that can play a role, one of them being job strain. Jobs with high demand but low autonomy and decision-making are more likely to lead to heart disease and related deaths. When work stress arises as a result of high demand and low reward, the risk of heart disease is high. Having lower job control also means higher risk of a heart attack. Taken together, all this strongly suggests that chronic stress, including work stress, can cause development of atherosclerosis and heart disease.146

This is just one example of a life stress that affects heart disease, but often stresses can cluster together, which further increases the risk of a heart attack or stroke. There is now abundant evidence that atherosclerosis is the end result of a chronic inflammatory process and that approximately 40–50 per cent of patients have no heart disease risk factors, just stress.

Stress can also play an important role in other conditions, such as diabetes. When under stress, blood sugar rises in response to cortisol release in order to supply energy for fight or flight – regardless of which one you end up doing, you’re going to need extra energy. Cortisol inhibits insulin production in an attempt to prevent glucose from being stored, so instead it can be used immediately. If the stress is resolved quickly, cortisol drops, insulin goes up, and blood sugar levels go back to normal. But if the stress is chronic and cortisol is chronically high, this produces a state of insulin resistance, where the body’s cells aren’t as responsive to insulin. Over time, this can lead to type 2 diabetes.147

There have been some interesting insights recently that have suggested that stress-induced chronic inflammation may be a contributing factor in up to 15 per cent of all cancer cases.148 The evidence tells us that stress itself doesn’t directly cause cancer, but stressful situations can sometimes lead us to develop unhealthy habits, such as smoking or heavy drinking. We know that these things can lead to cancer (although not always), so in this way stress could indirectly increase cancer risk.

On a slightly less serious note than cancer and diabetes, many people experience some kind of gastrointestinal symptoms when stressed, such as stomach ache, diarrhoea or excess gas. This is because stress hormones slow the release of stomach acid and emptying of the stomach in preparation for fight or flight, and also speed up emptying of the colon – you don’t want to focus on digestion if you’re about to run away from a threat.

Weight stigma, which has been covered in Chapter 2, is a form of social stressor which can impact a person’s health, as is racism or homophobia or any other form of discrimination. LGBTQ+ individuals are known to be at greater risk of mental health issues, and are more likely to seek mental health services compared with heterosexual people.149 Discrimination and harassment also has a huge negative effect on the body image of transgender and non-binary folks.150

Ethnic minority groups that experience racism have higher rates of both mental and physical ill health, including heart disease, diabetes, anxiety and depression. This has been linked to over-activation of the HPA axis and chronic stress due to discrimination.151

Although stress is a strong risk factor for the various conditions mentioned, not everyone who experiences stress gets sick, so there must be individual differences that make some of us more likely to be affected by stress than others. Aside from the obvious genetics, we all have slightly different brains and slightly different neural pathways, and some of us have lower pain thresholds than others. We also have differently strong immune systems, which may play a role too. One important point is that stress is subjective, and affects some people more acutely and intensely than others. Some people have clear coping mechanisms in place or a robust support system that allows them to cope with stress more effectively than others. There is also some evidence that the way we perceive stress influences if, and how negatively, it affects us.

Some stress is good for us and is necessary. Positive stress is also known as eustress. It’s motivating, exciting, manageable, improves performance and, most importantly, it’s short-term. It’s not chronic. A complete lack of stress is great if you’re on holiday relaxing on a beach in the sunshine, but if you’re trying to get a piece of work done, sit an exam or write a book (!), then having a little bit of stress in the form of a deadline, for example, can be highly motivating. A little stress helps focus the mind on the task at hand. But it depends on the person: if you’re sitting in an exam and look up at the clock to see you have fifteen minutes left, you might think ‘Fifteen minutes of focus. I can do this – just a few more things to write,’ which is a positive injection of a little stress; or it could make you panic by causing a large stress response, which is unhelpful. At high levels of stress, performance and ability drops dramatically. We all have a different zone of optimal performance under stress, and knowing where you sit can help you focus better and avoid feeling overwhelmed.

Your mind is pretty damn powerful, and although a lot of the ‘think yourself well’ messages out there are bullshit, there is evidence that your beliefs can have quite a strong influence on your mood. If you believe that you have the ability and resources to handle a stressful situation, then it’s far less likely to affect you negatively; whereas if you believe you can’t handle it you’re more likely to feel hopeless and out of control. This is a good thing, as while your emotions are hard to control and alter, you can change your thought patterns. If you are able to find a way to see your situation in a more positive light, you can alter your mood from negative to positive. This is exactly what I was illustrating in the example above about exams. Managing to cope with a stressful situation also gives us confidence that we can do it again.

If you believe you are able to have an impact and influence on events that affect your life, then you possess high levels of what is known as self-efficacy. This allows you to have a sense of control of stressful situations you encounter, so you’re less likely to experience negative stress feelings. The perception of being in control is what’s important, regardless of whether in reality you are or are not. The opposite is also true, so if you feel you aren’t in control (even if you actually are), you will feel stressed. People may also feel out of control because they don’t possess the appropriate coping skills to adequately cope with the situation.

Coping skills are tools that can be learned and carried around in your personal toolkit, on hand to help you cope with stressful situations. There are several popular approaches to reducing or managing stress that I want to mention, such as distraction techniques, pets, exercise and cognitive training.

Some people find it incredibly helpful to distract their minds from stressful thoughts. Of course, this isn’t possible in an acute stress situation such as an exam, but can be helpful if you’re stressing about something unavoidable that’s happening in the future, or something that you can’t change. Popular distractions include doing chores, going to see friends, baking, watching a movie, games, art or books. It helps if the distraction is interesting and that you can immerse yourself in it, as it makes it easier to focus for long periods of time. In that sense, it is quite an individual thing.

Pets are so much less complicated than humans, and so our relationships with them are far more predictable. We know that if we feed a cat or dog and pay it attention, they will generally show us love in return. That consistency and predictability can be really comforting during a time when it feels like everything in life is spiralling out of control. There is also something satisfying and fulfilling about taking care of another living being, which positively influences our self-worth. Pets can also directly improve our mood, as they help us to feel less lonely and isolated, and therefore less stressed. In particular, walking a dog means going outside and the chance to interact with other people (pretty much everyone loves dogs). Stroking a cat or dog has direct physiological effects such as decreasing blood pressure, lowering heart rate and decreasing muscle tension, all of which helps us to feel less stressed.

As we’ve already discussed in Chapter 8, moving your body is a great stress management tool. It focuses the mind, improves mood and releases endorphins. Yoga is believed to be particularly good for stress management due to its focus on breath work, meditation and the mind–body connection. A number of studies have shown that yoga may help reduce stress, as well as enhance mood and overall sense of well-being.152

Quiz: How stressed are you?

Indicate how often you feel the way described in each of the following statements.

|

NEVER |

ALMOST NEVER |

SOMETIMES |

FAIRLY OFTEN |

VERY OFTEN |

I constantly feel tired or depleted. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

I find myself over-reacting to little things. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

I worry constantly. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

I’m easily irritable. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

I don’t feel confident in my ability to cope with daily challenges. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

When I’m stressed, I make unhealthy choices for myself. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

My workplace feels like a high-stress environment. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

I struggle to sleep at night because my mind is racing. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

8–18 → low-stress lifestyle

19–27 → moderately stressed

28+ → high-stress lifestyle

When we are stressed, we start to have more ‘catastrophic’ ways of thinking. Cognitive training or professional therapy services such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can help challenge and readdress these thoughts, rather than accepting them as truth. This technique is based not so much on preventing stress but more on changing how we perceive stress and respond to it when it arises so it becomes more manageable.

Several lifestyle factors and environmental factors put us at risk of early death, such as smoking, physical inactivity, lack of sleep and air pollution. However, there is another key factor that is often overlooked, both in public health initiatives and in research, and that is social factors.

In countries like the UK, the quality and quantity of social relationships is decreasing. We have fewer friends than before, and even fewer who we see regularly in person rather than just online. This has been blamed on a number of reasons, including reduced intergenerational living, ease of movement, delayed marriage, larger numbers of single-parent households and more people choosing to live alone. Despite the huge amount of online connection we now have with other people, overall this doesn’t seem to have had a positive effect on our social connections. Perhaps it has made us lazy? It is more common now for people to report feeling lonely despite being surrounded by hundreds or thousands of virtual ‘friends’ and profiles. People are becoming increasingly more socially isolated. Given these trends, it’s vital that we are all aware of the significance of our social relationships and the impact they have on our health.

Living alone and not having regular social contact are all signs of social isolation. Loneliness is a subjective state; it’s the perception of social isolation or the subjective experience of being lonely. But loneliness and social isolation are not the same thing. For instance, someone may be socially isolated but perfectly content with being in that situation, whereas someone else may have frequent contact with friends but still feel lonely as it’s not enough for them.

Data from seventy studies with over three million participants showed that social isolation and loneliness result in higher risk of early death. People who are lonely and socially isolated are around 30 per cent more likely to die earlier.153 It isn’t something limited to elderly people either, but all adults of all ages.

Combining the effects of 148 studies shows that our experiences within social relationships significantly predict mortality. We are 50 per cent more likely to survive any given year if we have good relationships with friends and/or family.154 This is regardless of age, sex and cause of death. This has about the same effect on your life as quitting smoking, and has a greater effect than weight and physical inactivity, so it’s pretty significant overall.

People with active social lives recover faster from illness, are more likely to comply with medication, and have shorter hospital stays.155 They are also less likely to become ill in the first place, with lower risk of heart attack, stroke, dementia and other diseases.

The reasons that social relationships lead to better health overall are complex, as they influence healthy behaviours but also have a more direct effect on health by affecting biochemical changes in our bodies, which then affect disease outcomes. One big example is that there is a strong link between social support and having a stronger, more resilient immune system.154

There is a clear link between social isolation and reduced psychological well-being. Smaller social networks, fewer close relationships and inadequate social support have all been linked to depression.156 But it’s difficult to be sure how much of that comes from social isolation, compared to personality traits such as being an introvert, which mean people don’t want to participate in a lot of social situations and prefer to be alone. Cutting yourself off from friends and family can also occur as a result of depression and not wishing to be a burden on others, even though this tends to make the depression worse.

Having social connections is not just important for psychological and emotional well-being, but also physical health. There are two pathways that are suggested to influence health. One involves behavioural processes such as health behaviours. The idea is that social support promotes health, as it encourages healthier behaviours such as exercise, eating a balanced diet, sleeping well and not smoking. But that is only part of the story, as it’s also possible for social interactions to encourage negative health behaviours such as excessive alcohol consumption or staying up way too late and not getting enough sleep. The other pathway involves psychological processes such as mood and emotions and feelings of control. For example, having social support from friends can make stressful life experiences feel less overwhelming and more manageable. This effect applies to both mental and physical health outcomes.

An example of how this manifests in disease is that being around friends reduces your blood pressure,157 which reduces your risk of heart disease. There is also evidence that social relationships lead to lower adrenaline and cortisol levels – both important stress hormones – which means a stronger immune system that isn’t suppressed by stress. Another important hormone is oxytocin, sometimes known as the love hormone. This is the hormone that is released during breastfeeding, when you give someone a hug, and during sex. It’s an important hormone for human bonding, as it encourages trust and understanding through being able to read people’s emotional facial expressions.

Some researchers look at social bonds from a more evolutionary perspective, suggesting that humans are fundamentally motivated to maintain a social network because of the protection and support that others provide. It allows us to not have to worry about certain things in life as we can delegate them to others we trust. Because of this, cutting social ties can be particularly distressing to us, whether it’s a break-up, loss of a friend, or divorce. Humans have a basic need to belong and to be social; it seems to be ingrained in our evolutionary history and genetic make-up.

This goes some way towards explaining why people who are more socially connected with family and friends are happier, and live longer, healthier lives with fewer physical and mental health problems than people who are less socially connected. Being born into a close family means a child is given the best social start in life, by laying the foundations of feeling loved and valued. It also allows them to learn to build supportive relationships; develop intellectual, social and emotional skills; and develop lifelong healthy habits. Family ties in adulthood, such as having a strong, healthy, loving relationship with a partner, has positive impacts on health and provides us with support to deal with life’s challenges. We know that being part of a social network (in person, not online) gives people meaningful roles that provide self-esteem and give a sense of purpose. That could be something as simple as carrying the responsibility of organising a monthly dinner party, or attending a theatre group where each person has a different role to play. Take that away from someone and it can affect their self-worth and happiness.

Interestingly, having a few close friends is important to all adults, but having close family ties is more important to men than women for their well-being.158

Healthcare professionals, teachers, the media and the general public all take smoking, nutrition and exercise seriously, but often neglect social relationships. We need to take social health into account as well as physical and mental health, if we want to get an overall picture of someone.

Quiz: How lonely are you?

Indicate how often you feel the way described in each of the following statements.

|

NEVER |

RARELY |

SOMETIMES |

OFTEN |

I feel in tune with the people around me. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

I lack companionship. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

There is no one I can turn to. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

I do not feel alone. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

I feel part of a group of friends. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

I have a lot in common with the people around me. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

I am no longer close to anyone. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

My interests and ideas are not shared by those around me. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

I am an outgoing person. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

There are people I feel close to. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

I feel left out. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

My social relationships are superficial. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

No one really knows me well. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

I feel isolated from others. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

I can find companionship when I want it. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

There are people who really understand me. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

I am unhappy being so withdrawn. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

People are around me but not with me. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

There are people I can talk to. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

There are people I can turn to. |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

The higher the score, the more lonely it seems you are.

It probably goes without saying that access to healthcare usually means better health. Equal access to healthcare has been a central focus in the NHS since its inception in 1948. In theory, there shouldn’t be discrepancies in access to healthcare, as the NHS is free to patients at the point of use, but that isn’t the case. Health needs will not be the same across different areas of the country and will vary according to the socio-economic characteristics of an area. There are a few reasons why there are variations from region to region when it comes to access to healthcare: some health services may not be available to certain population groups – for example, child and adolescent mental health services, or IVF clinics. The quality of services may also vary, as different practitioners will have varying degrees of expertise and interests. Equal access doesn’t necessarily mean equal treatment. There may also be discrepancies in patients’ awareness about the services available, and there can be additional costs, such as for prescriptions.159

When a medical appointment is booked, a patient generally has to physically get to the clinic or facility (with the exception of phone consultations, for example). Geography, local support and access to transport all influence how easily someone can attend an appointment. The cost of transport and distance to the GP surgery can also be a factor. Almost 40 per cent of people living in rural areas do not have a GP within 2 km, compared with only 1 per cent in urban areas. Older people are particularly susceptible to these factors, as are people with families, since family commitments can take priority, which affects whether a patient is free to attend an appointment or be brought to an appointment by another person. People working regular daytime hours may not be able to take time off work for appointments, and working parents may not be able to take time off to take their children to an appointment. Extended opening hours in some GP surgeries have definitely helped with this, but only up to a point.

Access to mental healthcare is a particularly large problem, with waiting times steadily increasing, and patients sometimes having to be sent across the country – sometimes from Oxford all the way to Scotland – for intensive psychiatric care. It probably goes without saying that this can have a huge effect on recovery if patients are unable to see family as often, and places an extra time and cost burden on family and friends to afford travel.

Although health in urban areas in general is usually worse than in rural areas, countryside living does come with the disadvantage of more difficult access to GP and hospital care.160 As an example, if you needed joint surgery, the probability of getting it depends on who you are and where you live. In particular, older people, women, and those living in deprived areas seemed to be disadvantaged.161 That’s not equal access.

Of course, the UK is very fortunate to have a healthcare system that is free at the point of access. In countries without a national health service, such as the US, insurance policies determine access to and affordability of healthcare, and lack of insurance is an additional risk. The US healthcare system is not a universally accessible system – it is a publicly and privately funded mixture of systems and programmes. Insured Americans are covered by both public and private health insurance, with the majority covered by insurance plans through their employers. Government-funded programmes, such as Medicaid and Medicare, also provide healthcare coverage to some vulnerable population groups. The US has excellent healthcare facilities, but not everyone, especially those who are uninsured, can afford to access these. The primary reason Americans give for problems accessing healthcare is the prohibitively high cost. In fact, for a patient who has no insurance, a medical bill can lead to lifelong debt.

In Australia, for example, all permanent Australian residents have access to Medicare, the state healthcare provider, and this is paid for through taxes. While most of the time an Australian will never see the bill for their medical care, sometimes they’ll have to pay and then claim back the money, which can put someone in financial difficulty. The government is also trying to persuade anyone who earns enough to take out private policies on top of their state coverage to relieve pressure on the public system. On the one hand, this makes sense, as it leaves the public system more available to those who can’t afford private insurance; but it also creates a divide between those who have private healthcare and those who don’t, with differences in accessibility to health services. For example, if you have private insurance you can be treated at both public and private hospitals – more choice – whereas if you don’t you can only be treated at public hospitals.

Because of the vastly different healthcare systems around the world, the notion of the word ‘access’ is dependent on context. In the US, access usually means whether the individual is insured, and if so, to what degree. In Europe, however, access is more likely to mean how easy it is for a patient to secure particular services, at a certain level of quality, and whether there are any personal inconveniences such as waiting times or distances to travel.

If I asked you ‘What causes poor health and disease?’, you might say poor diet and lack of exercise. And you’d be right, to an extent. But what causes poor diet? What is the cause of the cause? These are the very sources of the problems of health we face in society, and they are the social determinants of health.

Social determinants of health refer to the social, cultural, political, economic, commercial and environmental factors that shape the conditions in which we are born, live and work. They are also sometimes referred to as the wider determinants of health, or socio-economic factors.

I really like the ‘rainbow’ model of the determinants of health, as it illustrates this in the form of multiple layers of influence, one on top of the other. At the centre we have our own individual actions, and on top of that are layered influences of family, friends, community and neighbourhoods. On top of that are the social and economic structures such as employment and housing, and finally on top of that there are national policies on welfare as well as cultural influences, such as the role of women. Each layer is influenced and affected by the layer above it.

We see weight as purely dictated by lifestyle choices, primarily diet and exercise, but what about factors that are beyond our control? What always gets left out of the conversation on the ‘war on obesity’ is the huge disparity between high- and low-income families.

For starters, the life expectancy difference between the most and the least deprived areas is nine years for males and seven years for females. The UK is a wealthy society, yet a baby girl born in Richmond upon Thames can expect to live seven years longer, and live seventeen more years in good health, compared with a baby girl born in Manchester. There’s a reason we call it the North–South divide. In general, the lower an individual’s social position, the poorer their health is likely to be.162

These social determinants, or causes of causes, can influence our health in many ways, including through our health behaviours such as food choice and exercise. But our own individual control over these behaviours is often limited, as any unhealthy behaviours are usually not the definitive cause of poor health, but are at the end point of a long chain of cause and effect in people’s lives. If you’re struggling with this concept I’d like to gently remind you of a great quote I’ve seen online: ‘If you don’t have to think about it, it’s a privilege.’ Saying someone has privilege is not a moral judgement. Becoming aware of your privilege shouldn’t be a source of guilt, although it’s natural for the thought to come with defensive feelings, but should be seen as an opportunity to learn. For example, I recognise that I have white privilege, thin privilege, educational privilege and financial privilege as I grew up in a middle-class family. Acknowledging this is the first step to understanding that someone else might not have had the same experiences in life. Having a higher income comes with a great deal of privilege, and can lead us to believe that all our health behaviours, particularly our food choices, are perfectly within our control, because we have no financial barriers that prevent us from eating the way we want to. If you don’t struggle to afford eating a varied balanced diet, if you have no financial barrier, no education barrier, no time barrier, then you are in an incredibly privileged position. That’s not a criticism, but something to think about as you read the rest of this section.

There are several of these ‘causes of causes’ that I want to highlight: education, employment, housing, our surroundings, and money/income.

Level of education is strongly linked with health. The more educated someone is, the less likely they are to suffer from chronic conditions, suffer from mental health issues such as depression or anxiety, or consider themselves to be in poor health.163 Education impacts on many areas in life such as quality of work, future income, involvement in crime and risk of premature death. A good education can help access to good work, problem-solving, feeling valued and empowered, and supportive social connections. These all help people to live longer, healthier lives by increasing opportunities and limiting exposure to some of life’s challenges.

Education is also affected by income. In 2015 to 2016, 14 per cent of children in England were eligible for free school meals, which are only available to those who come from low-income households. These children were significantly less likely to reach a good level of physical, personal, social and emotional development than children not eligible for free school meals. This means that children from more deprived areas are less likely to receive a good education, which means they are more at risk of long-term health conditions and less likely to be able to live long, healthy lives.

Employment is one of the most important determinants of health, as it is closely related to income. Being unemployed puts someone at greater risk of poor health and early death. Young people in particular who are not in employment, education or training are at greater risk of poor physical and mental health, as well as being more likely to have lower quality jobs later, with lower income.164

The effect of unemployment goes beyond just the individual. Children growing up in households where both parents are unemployed are almost twice as likely to fail at all stages of education compared with children growing up in families where at least one parent is working.

As with education, there is a clear social gradient when it comes to unemployment. Unemployment in the most deprived areas is considerably higher than in the least deprived areas. So how does this affect health? Good working conditions, working in a safe environment, practices that protect employees’ well-being, good pay… These factors all create an environment where employees are more supported, have opportunities to grow and progress, and feel a sense of autonomy over their work. Being in that kind of environment will be much less taxing on stress and mental health in particular than a working environment with poor conditions, chance of injury or contact with harmful toxic substances.165 Lower-paid employment is more likely to have higher risk of injury and low levels of job control – which can include monotony, no sick pay and only being allowed breaks at highly specific times. Good work provides people with the opportunity to afford basic living standards, to be able to participate in the community and have a social life, as well as feel a sense of identity, self-esteem and purpose.

Our mental well-being is particularly affected by unemployment. Loss of income is the obvious culprit, but there are more nuanced factors at play. For many people, their job is what gets them out of bed in the morning, adds structure to their day and makes them feel like they have a sense of purpose and self-worth. A job is where they make connections and friends, and feel a sense of achievement. All this is taken away with unemployment.

In the longer term, unemployment, poverty and psychological issues can become a vicious circle. Being unemployed and poor can lead to poorer health outcomes, which in turn hinders someone’s attempts to escape unemployment and poverty. Unemployment often happens in repeated spells: once one job is lost, the next is often less secure.166

A house is more than just a roof over our heads: it’s our home, where we grow up or grow old, where we are supposed to feel safe and comfortable and warm.

Fuel poverty is described as being when a household cannot afford to keep adequately warm at a reasonable cost, which again relates back to income. Children living in cold homes are more than twice as likely to suffer from respiratory problems as children living in warm homes.167 Living conditions that are damp and mouldy also increase the likelihood of health problems including wheeze and other respiratory problems, aches and pains, diarrhoea, headaches and fever.

Overcrowding is another issue, as this has particularly negative effects on mental health, as well as being thought to increase vulnerability to airborne infections, diarrhoea and coughs.168

Our health is influenced by our surroundings – how they make us feel and the opportunities they provide. This can include the public transport systems that allow us to get to work, being near shops and schools to make it easier to walk to them, and having green spaces for play. The latter is particularly important, as having well-maintained and easy-to-reach green spaces makes it easier for people to be physically active.169 Public open spaces in higher socio-economic areas are more likely to have trees, ponds, walking and cycling paths and picnic tables. These are all features that encourage being outdoors and promote physical activity for both children and adults.170 Green spaces in general, regardless of their facilities, are more available to higher income neighbourhoods. Plus there are issues of crime and traffic, neither of which make it easier for children to play outside.

Urban areas in general, particularly big cities, have lower air quality than rural areas, which affects health. People living in the most income-deprived neighbourhoods may be most exposed to air pollution, which affects risk of respiratory diseases as well as early death.171

In 2014, Transport for London adopted an action plan to improve air quality, reduce congestion and create healthy surroundings for people to live, work, travel and play. A healthy street is one that has things to do, places to rest, shelter and clean air. It has to feel safe and not be too noisy. It’s an environment where people are happy to live and to walk around. All these things make for positive surroundings that positively affect our health.

This is the big one! A lot of the previous aspects of socio-economics come back to money/income. There is a strong association between income and health, and many aspects of health improve as income increases. Beyond that, income also has an effect on others – for example, your parents’ income will have affected your early development, your education, and therefore your employment and income.

In simple terms, not having enough income can lead to poor health because it makes it more difficult to avoid stress, it fosters a feeling of being out of control, you don’t have a financial safety net, and certain resources and experiences will be out of reach. Money can enable people to access the support and services they need to participate fully in society. Limited income or access to fresh fruits and vegetables can make it more difficult for people to adopt healthier lifestyle choices.172 Time is money, and having more money usually means having more time – time for things like chopping vegetables, making soup, slow-cooking and food shopping. A tired working parent who arrives home in the evening to hungry children may have neither the energy nor the time to spend half an hour preparing a meal. Having a higher income also means that trying new recipes and ingredients carries fewer risks, especially with children, as if they don’t like it and won’t eat it you can just make or buy something else instead.

There are two explanations for why money and income are linked to health. The first is that living on very little income is stressful, and as we have seen, stress has huge, far-reaching impacts on health. The second is that people feel of lower status in society compared with others, because of the lack of income, and that causes distress. These negative feelings and sensations can cause real biochemical changes in the body, which over time can wear down the immune system and other bodily functions. It’s also important to point out that these negative feelings and distress lead to mental health problems being more prevalent among disadvantaged groups. The stress of experiencing racism or homophobia regularly, the stress of weight stigma, and the stress of constantly having to worry about money can all lead to mental health issues such as depression or anxiety. Some people may use unhealthy behaviours such as smoking or drinking alcohol as a method of coping with the stress they are under. Healthy behaviours can be expensive – for example, joining a gym or taking part in school sports clubs. It’s also important to note that these stresses may mean someone focuses more on the present at the expense of the future, because the future is uncertain; and so someone might be less concerned with the long-term, health-damaging effects of behaviours that bring them pleasure or stress relief in the present moment.

Sometimes the simple arguments make sense – for example, that low income leads to lower quality diet, which has negative health consequences. But it’s also a little bit more complicated than that. There is a web of complex factors that link socio-economic factors to health. For example, low income can lead to stress, which leads to depression, which discourages exercise, which can lead to poorer health. Or low income can lead someone to pick up an extra job with low autonomy, which is stressful, which causes negative emotions and distress, which over time affects the immune system and cardiovascular system and increases risk of infection and heart disease. It’s complex.

Having a higher income generally means being able to afford to live in a more affluent area, which comes with better air quality, better facilities, better access to healthcare, higher density of exercise studios (the more middle class an area is, the more yoga studios pop up) and better schools. All these things carry health benefits.

Money and income affect so many different aspects of health, and affect us throughout our lives, from birth to childhood education, to employment, and into retirement. Income from employment is affected by education, which in turn is affected by childhood health and parental income.173 This means that the relationship between money and health is intergenerational and bidirectional: for example, parents’ income influences their children’s health, and children’s health influences their later earning capacity and their future income.

Hopefully, it’s now clear that all these factors are interlinked, and money is a key part of that. Although people are living longer now than ever before, it still remains that those in socially disadvantaged groups are more likely to face conditions that lead to poorer health and an earlier death. These health inequalities don’t just exist between the very rich and the very poor in society – they span the entire population.

Bringing this back to weight and health for a moment, research investigating socio-economic disparities in weight have shown that factors outside our immediate control – such as income, neighbourhood, ethnicity, gender and level of education – all influence weight. Individuals who are marginalised either through low socio-economic status and/or non-white ethnicity are more likely to be in larger bodies, due to stress and these social determinants of health.174 Looking at weight through a larger intersectional lens, those who are most disadvantaged – particularly if in more than one area (e.g. low income and ethnic minority group) – are more likely to be fat, and there is a gradient across the spectrum of wealth rather than simply a rich–poor divide. While those in the best socio-economic position tend to have the best health and those in the worst circumstances the poorest health, for those in between, small changes in income or other socio-economic factors can have an impact on health risk, as each slight improvement in position improves health. For example, there seems to be a lower risk of early death among people who have higher degrees compared with standard degrees175, which suggests a continuous gradient in health rather than a large step up between groups. Income often displays a continuous gradient with health. At some point there may no longer be any health gains from more income, but for the vast majority of people it really does make a difference.

What do I want you to take away from this? First, hopefully this has shown you that health is so much more than just what we eat, and there are real and distinct barriers that prevent people from having control over their health. What we eat and how we move our body isn’t purely down to individual choice; we only tend to think that way if we’ve never experienced those barriers for ourselves. But they are there, and we need to acknowledge them, and use them to remind ourselves that we can’t judge and shouldn’t shame ourselves or other people for the food choices they make. It’s not that simple. We need compassion and understanding to improve population health, not stigma and stress.

* Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.