Is Lawrence difficult? Certainly not in the same ways that Joyce and Stein are. Although Lawrence thought of his writing as radical, as cultural “surgery” or a “bomb,”1 his formal experimentation has often been underestimated, F. R. Leavis notwithstanding. (Leavis described Lawrence as “so much more truly creative as a technical inventor, an innovator, a master of language, than James Joyce,” an assessment jarringly out of step with the current critical consensus.2) Since the 1960s, most critics who struggle with Lawrence do so on the basis of his politics. However, his idiosyncratic style and iterative, polemical prose have always been puzzling. Scholars have become increasingly interested in the techniques through which Lawrence guides his audience’s response. Anne E. Fernald draws attention to Lawrence’s “coercive language” and “abrasive method.”3 Charles Burack suggests that Lawrence “mortifies” and “assaults” his readers’ sense of language, and that his “textual effects invite and channel potential reader responses.”4 A. S. Byatt, upon rereading Lawrence, admits that she found herself “irritated again by his insistent sawing noise, his making a point over and over” and his “preacherly pulpit-thumping,” but concludes that Lawrence’s near disappearance from U.S. college syllabi is the result of a refusal to engage with difficulty: “What has disappeared is the sense that literature is exacting, diverse, and difficult to read or to describe.”5 As a modernist pedagogue (or preacher), Lawrence is particularly overt, but his lessons have not yet been understood completely, largely because of readers’ resistance to the way he delivers them. As John Worthen observes, “in some ways we are still learning to read” Lawrence.6

One part of Lawrence’s work we are still learning to read is his representation of pleasure. He has a reputation as an innovator of sex writing who at the same time produced increasingly conservative, stereotypical images of masculinity and femininity. The Lawrence of “Tickets Please,” seemingly alarmed about women’s potential power, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, for whom “the bridge to the future is the phallus,”7 is difficult to reconcile with the Lawrence of Women in Love and other work in which he explored the possibility of men and women being equal partners.8 Lawrence’s representations of eroticism are shaped by innovative and derivative impulses, and by originality and repetition; he alternately encourages and prohibits—or, more precisely, dictates—particular kinds of pleasure in his characters and in his readers. These contradictions are exemplified by the way Lawrence handles one best-selling text of pleasure: E. M. Hull’s The Sheik.

In the first part of this chapter, I will examine the remarkable attention Lawrence and critics such as Q. D. Leavis pay to Hull’s novel and the subgenre to which it belongs, desert romance, whose predictable formulas and sensational prose were viewed as epitomizing popular pleasure. The Sheik has a surprisingly prominent place in significant formulations of British modernism precisely because of the efficiency with which Hull manages readerly pleasure. In his effort to revive sexual experience, Lawrence turned to the tropes that he criticized in Hull’s work but used them toward fundamentally different ends. Lawrence’s response to Hull’s writing exposes an important conflict between the modernist ambition for innovation and its reluctant recognition of popular culture’s attractions. It also demonstrates an intrinsic paradox of pleasure: its dependence on both novelty and familiarity. In the second part of this chapter, I will examine how several of the features Lawrence borrows from Hull return in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, his most explicit and radical treatment of eroticism. Here Lawrence writes about sex, not to promote pleasure but rather to discipline and even curtail it.

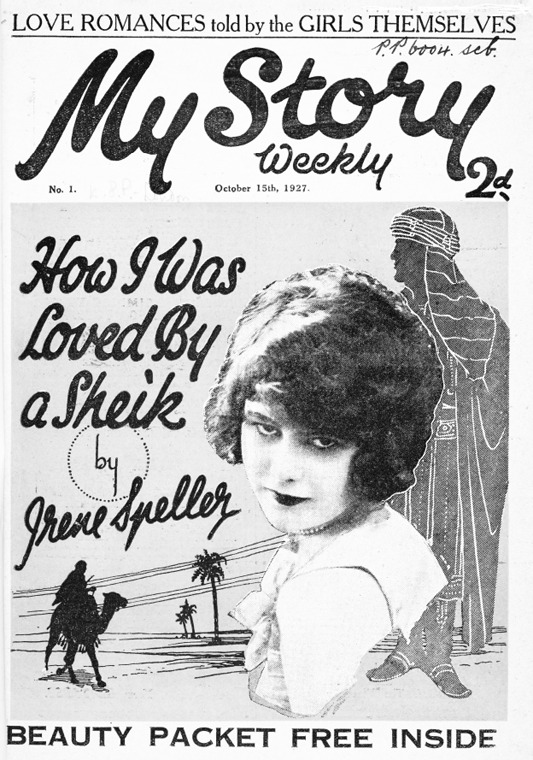

My Story Weekly

P.P.6004.scb, Oct. 1927, cover © The British Library Board

“ARE YOU NOT WOMAN ENOUGH TO KNOW?”

On October 15, 1927, the debut issue of My Story Weekly appeared in London with a cover image calculated to draw an audience: a sleek flapper, glamorous and dreamy, against a background oasis complete with camel, palm tree, and a male figure in a turban and robes. Inside, in a tone that simulates an intimate chat at the local teashop, with frequent addresses to the reader, Irene Speller’s “How I Was Loved By a Sheik!” recounts the author’s trip to Damascus with a British dance troupe. There, “in the East,” Speller confides, she “met with adventure and romance, which make all the sheik stories ever written pale into insignificance.”9 She and her dancer friend Winnie compare their first glimpse of the Saharan sky to images they have seen on “glowing posters … outside the picture palace at Shepherd’s Bush. Haven’t you seen them too,” Speller asks her reader, “outside the picture palace in your neighborhood?” (2). But the East is “not much like Shepherd’s Bush,” Speller and Winnie conclude, especially when a dashing sheik appears one night in the theater in which they are performing and fixes his “amazing dark eyes” on Speller (“dark, flashing eyes that you never see in the men here in England” [3]). The sheik makes his move and invites her to his elegant desert tent. Amid clichés such as “Love knows no boundaries” and “There was something in the air that night,” he woos Speller while other characters repeatedly warn her that he “has got different ideas to the sort of men we know” (3). As Speller obsesses about how the sheik might kidnap her and make her his “desert queen,” it becomes clear that alterity and danger are a central part of the story’s thrill. And yet, as the tale’s hackneyed language and multiple references to “sheik stories” indicate, the appeal of Speller’s adventure is not its novelty, but its reiteration of an excitingly predictable formula with which the author assumes her readers are familiar. The narrative concludes with Speller tearfully leaving the sheik, quoting Rudyard Kipling’s already clichéd “We were East and West, and, of course, it is true now that ‘never the twain shall meet.’”10

My Story Weekly became one of the most popular British women’s magazines, and its editors’ choice of Speller’s story for the inaugural issue is indicative of interwar reading tastes. “How I Was Loved by a Sheik!” is a less violent and sexually explicit imitation of one of the most successful fictions in early twentieth-century British publishing history, E. M. Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik. In this orientalist fantasy, Diana Mayo, an arrogant English aristocrat who rejects marriage and other trappings of womanliness, dares to take a trip into the Algerian Sahara with only Arab guides. She is captured by a handsome sheik and taken to his luxurious caravan in the desert, where he forces himself—along with lavish jewelry and dresses—upon her. After much bosom heaving and bodice ripping, Diana becomes conscious of her love for the “lawless savage,” and she decides to stay with him in their love oasis.11 British readers thrilled to this sadomasochistic fantasy, sending the novel through 108 reprintings in the UK by 1923.12 Two years later, audiences clamored to see Rudolph Valentino, in the title role that made his reputation, kidnap and ravish his way through George Melford’s film adaptation of The Sheik as well as its sequel, also based on a novel written by Hull.

Hull followed The Sheik with The Shadow of the East, The Desert Healer, and The Sons of the Sheik, which joined a plethora of fictions with similarly suggestive titles by other authors: Desert Love, The Hawk of Egypt, The Lure of the Desert, Burning Sands, Harem Love, and so on. The Sheik inspired so many imitators that we can accurately speak of an interwar desert romance genre. The elements were intensely formulaic: a beautiful woman, usually British, leaves the home country for the “Arab East” (including a diversity of locales such as Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco), which is routinely signified by the same images: endless deserts and skies, jasmine-scented nights, ill-tempered camels, and lustful, gorgeous sheiks.13 Above all, the heroine is “swept away” and made more exquisitely feminine (that is, pleasurably passive) by her encounter with a relentlessly masculine sheik. The dominant imagery in desert romance is the cliché of “burning desire” or “consuming passion”: there is no body part of the sheik that does not sear the heroine, and no emotion that is not experienced as a conflagration. While the stories were of varying degrees of sexual frankness, Hull’s novel was the supreme model for “sheik stories” in the interwar period.14

In The Long Week End, Robert Graves and Alan Hodge note that “Tarzan of the Apes was the most popular fictional character among the low-brow [British] public of the Twenties; though the passionate Sheikh of Araby, as portrayed by E. M. Hull and her many imitators, ran him pretty close.” The terms “Sheikh” and “Sheikhy” entered the popular lexicon as synonyms “for the passionately conquering male.”15 Sheet music and gramophone records and a number of “sheik films” capitalized on the appetite for desert romance between the wars; at least two perfumes called “Sheik” were launched in the early 1920s.16 And then in the 1930s the mania for desert romance waned (although the theme lives on in women’s mass market romances, such as Susan Mallery’s Harlequin titles, The Sheik and the Bought Bride, The Sheik and the Christmas Bride, The Sheik and the Pregnant Bride, etc.).17 This was a relatively short shelf life, given the fervor with which British readers consumed “sheik stories.”18 Intriguingly, this genre—a celebration of male power and female submission—reached the pinnacle of its popularity in Britain at a time of vigorous debate about new possibilities for gender roles in the wake of World War I. Moreover, the desert romance, among the most deliberately derivative of popular fiction genres, peaked at the same moment that modernist fiction was pursuing originality and “making it new.”

The broad narrative strokes as well as the linguistic details of The Sheik would become important to Lawrence. As Hull’s novel opens, its heroine, Diana Mayo, seems an unlikely model of sexual adventurism. She appears to have no libido at all, but by the end of the story, this ice-cold androgyne is begging for the love of a “fierce desert man.” The commonplace reading of The Sheik as a taming of the New Woman is not strictly accurate.19 Diana has none of the political concerns of the typical New Woman (although she does have fashionably bobbed hair). Her declaration that “Marriage for a woman means the end of independence” is quickly undercut by her modification, “that is, marriage with a man who is a man, in spite of all that the most modern woman may say” (9). Diana is an orphan who was raised by her brother, Aubrey. “You have brought me up to ignore the restrictions attached to my sex” (24), she reminds him when he tries to curb her freedom. This privilege is more a matter of spoiled will than political consciousness, and Hull clearly intends Diana to seem unnatural.

Hull performs a balancing act as she encourages her reader to identify narcissistically with Diana while colluding against her. As with all romances, physiognomy is destiny. Diana is beautiful, of course, but also haughty, and she must give up her willfulness so that the romance plot can unfold. When she tells Aubrey, “I will never obey any will but my own,” his response—“Then I hope to Heaven that one day you will fall into the hands of a man who will make you obey” (24)—is a desire that Hull develops in the reader too, and it proves to be prognostic. The story of Diana’s abduction, captivity, and rape (of which more later) are told in a breathless manner culminating in victorious debasement: “The girl who had started out so triumphantly from Biskra had become a woman through bitter knowledge and humiliating experience” (102).

Against all warnings, Diana rides out into the desert with an entourage of “natives.” On the second day, the party is ambushed; a turbaned figure on horseback chases Diana across the dunes and lifts her off her horse onto his with one sweep of his powerful arm. He takes her into a tent of magnificent luxury and throws her on a well-appointed divan (sartorial and interior design details feature prominently in The Sheik). Flinging aside his cloak, the sheik stands before her, “tall and broad-shouldered,” with “the handsomest and the cruellest face that she had ever seen.” Nature triumphs over culture as Diana finds herself “dragging the lapels of her riding jacket together over her breast with clutching hands, obeying an impulse that she hardly understood.” In an instant, the sheik undoes Aubrey’s years of cultivating boyishness in Diana, and she reverts to a performance of melodramatic womanhood.

“Who are you?” she gasped hoarsely.

“I am the Sheik Ahmed Ben Hassan. …”

“Why have you brought me here? …”

He repeated her words with a slow smile. “Why have I brought you here? Bon Dieu! Are you not woman enough to know?” (48)

But Hull’s reader is woman enough to know, and this superior knowledge aligns the “womanly” reader with Ahmed and his desires.

Critics routinely describe the first encounters between Diana and Ahmed as extended rape scenarios, which they are, technically, but they are crucially qualified by Hull’s language. Throughout Diana’s struggles with Ahmed, Hull dwells on “the consuming fire” of his “ardent gaze” and his “pulsating body.” Hull’s repetition of and endless variation on “burning desire” has a cumulative effect, indicating desire and physical excitement where there is also violence and moral outrage:

The flaming light of desire burning in his eyes turned her sick and faint. Her body throbbed with the consciousness of a knowledge that appalled her. She understood his purpose with a horror that made each separate nerve in her system shrink against the understanding that had come to her under the consuming fire of his ardent gaze, and in the fierce embrace that was drawing her shaking limbs closer and closer against the man’s own pulsating body. (49)

Without explicitly describing what is happening in this scenario, Hull’s language, focusing on the sensations of pulsating and flaming, indicates somatic pleasure amid Diana’s fear and horror. The body “throbs” independently of her mind, asserting itself over and against her moral response. (Ahmed even carries a smoldering prop around with him: his Turkish cigarettes. Diana comes to associate the “perfume” of his tobacco, confusingly mingled with the “faint, clean smell of shaving-soap,” with his “pulsating body.” The Sheik and Joyce’s Blazes Boylan have these pungent Turkish cigarettes in common: it was, apparently, the choice of lotharios everywhere.) Hull generates an erotic dynamic from the oscillation between knowledge and denial, physical sensation and ethical indignation. Diana struggles to understand the meaning of her corporeal sensations, but the reader, for whom the tension between the body and the mind is spelled out, knows better.

Hull encourages her reader to identify with Diana while hoping, like the sheik himself, for her forced fall into passion.20 In Hull’s forerunners among romance, sensational, gothic, and seduction novels, a direct identification with the heroine is invariably central to the formula. No matter what the heroine’s shortcomings may be, the reader is rarely encouraged to desire, with the male villain or rake, her demise. When Diana is “shaken to the very foundation of her being with the upheaval of her convictions and the ruthless violence done to her cold, sexless temperament” (78), Hull’s construction suggests that her heroine’s sexlessness is preposterous. Through these unorthodox arrangements of sympathy, identification, and sensation in The Sheik, Hull represents pleasure as simultaneously outrage and thrill, and a final surrender to everything Diana initially resisted.

At one point, Diana manages to escape the encampment right after Ahmed has asked her to “choose” whether she will submit to him or not. She says that she will and, disappointed in herself, channels the outraged spirit of a horse she has seen Ahmed tame brutally. However, once she finds herself at liberty in the desert dunes, she relaxes and begins smoking a cigarette, which she gradually realizes is one of the Sheik’s:

She had always been powerfully affected by the influence of smell, which induced recollection with her to an extraordinary degree, and now the uncommon penetrating odour of the Arab’s cigarettes brought back all that she had been trying to put out of her mind. With a groan she flung it away and buried her face in her arms. The past rose up, and rushed, uncontrolled, through her brain. Incidents crowded into her recollection, memories of headlong gallops across the desert riding beside the man who, while she hated him, compelled her admiration, memories of him schooling the horses that he loved, sitting them like a centaur, memories of him amongst his men, memories more intimately connected with herself…. There had even been times when he had interested her despite herself. (105)

The Proustian cigarette elicits memories of Ahmed’s caresses and his “handsome brown face”; Diana, “writhing on the soft sand … struggled with the obsession that held her” (105). As with Joyce, the at-first foul odor of the Sheik’s cigarette induces the tender and “intimate” memories that Diana has not to this point admitted. When Ahmed comes after her and sweeps her up again onto his horse, she is putty in his “long, lean fingers…. Quite suddenly she knew—knew that she loved him, that she had loved him a long time, even when she thought she hated him” (111–112). The metaphoric flames now become a bonfire of passion into which Diana flings herself.

Now she was alive at last, and the heart whose existence she had doubted was burning and throbbing with a passion that was consuming her. Her eyes swept lingeringly around the camp with a very tender light in them. Everything she saw was connected with and bound up in the man who was lord of it all. She was very proud of him, proud of his magnificent physical abilities, proud of his hold over his wild, turbulent followers, proud with the pride of primeval woman in the dominant man ruling his fellow-men by force and fear. (152)

At last the burning and throbbing make sense to Diana: they are the somatic symptoms of the “primeval woman” meeting her match in the “dominant man.”

Throughout The Sheik, Hull handles racial stereotype with the same double movement of attraction and repulsion, predictability and exception that she does desire in general. Desert romance inverts the gender positions in conventional orientalism by imagining an eroticized masculine “foreigner” and casting the fantasy from a woman’s perspective, but the terms of that eroticization are just as stereotypical.21 Hull pedantically insists that “the position of a woman in the desert was a very precarious one” because of Arab men’s “pitiless … disregard of the woman subjugated” (78). But this is all in bad faith, as Diana comes to love a version of that subjugation. The moment she realizes her feelings for Ahmed also involves such contradictions and polarizations:

Her heart was given for all time to the fierce desert man who was so different from all other men whom she had met, a lawless savage who had taken her to satisfy a passing fancy and who had treated her with merciless cruelty. He was a brute, but she loved him, loved him for his very brutality and superb animal strength. And he was an Arab! A man of different race and colour, a native; Aubrey would indiscriminately class him as a ‘damned nigger.’ She did not care. It made no difference…. She was deliriously, insanely happy. (112–13)

That Hull emphasizes stereotypes at this turning point suggests that the frisson of alterity and polarity is a central part of the erotics of The Sheik, and it remains so long after Diana “discovers” her feelings for Ahmed and the “embraces she panted for” (123). She continues to imagine Ahmed as a “lawless savage” even after evidence to the contrary appears.

At the end of the novel, Hull springs a surprise on the reader. Ahmed is actually the son of an English earl and a Spanish mother. Hence, it would appear that the sexual compromises of the previous two hundred pages and the scandal of loving an Arab are recuperated with an aristocratic marriage to a white man. This is surely the most clichéd part of Hull’s novel: the ubiquitous marriage denouement. And yet, while the subject of marriage bookends the narrative (Diana rejects marriage at the beginning of the story but marries at the end), in between, there is no attention to marriage whatsoever. As Billie Melman observes, “both the marriage and the discovery, by Diana, of Ahmed’s ‘real’ identity are gratuitous. At no point in the whole story is matrimony presented as a necessary alternative to an unlawful but happy concubinage” (102–103). Despite the conventional frame, The Sheik presents an erotic fantasy almost completely unmediated by proprietary concerns, which may well account not only for the tremendous popularity of Hull’s novel but also for the unusual attention that an unlikely modernist audience gave to The Sheik.

“THE TYPIST’S DAY-DREAM”

The London Times Literary Supplement review of The Sheik focused exclusively on the novel’s plot, without making any judgment about the quality of the writing. It was the last time that Hull would be described so neutrally. “It is a bold novelist who takes his [sic] heroine into the Garden of Allah by the gates of Biskra, as heroes are so hard to find there who comply alike with the requirements of the proper local culture and the conventions of romance as written for Western people.”22 Despite misattributing male authorship, the Times reviewer shows a canny understanding of the dilemma of genre and geography in which Hull finds him/herself. But the Times conclusion is amiss: “If there be a moral here in this simple tale it is one of warning to young European ladies not to ride alone into the Sahara.” The translation of Hull’s fantasy novel into a cautionary tale is the first of many misreadings of The Sheik. Hull not only inaugurated an orientalist psychogeography for women but also initiated a kind of female sexual tourism. In the early twentieth century, solo British female travelers were increasingly common, but, writes Osman Bencherif, it was “E. M. Hull who, with The Sheik, first put the desert on the map as an exotic place of sexual indulgence” (180). In 1924 the Daily Express journalist H. V. Morton wrote a multi-installment column from Biskra, “In the Garden of Allah.” Although his title borrows from Robert Hichens’s 1904 novel, the scene Morton describes is much more Hullian: a city full of British and American women seeking erotic adventure, “English girls, advertising the fact that they are wearing non-stop silk stockings … riding past on camels,” in search of passionate sheiks. Morton himself admits, “I want sheiks. I want the real Edith M. Hull stuff. I want to see how perfectly ordinary people from London, Paris, and New York behave under the influence of the Sahara” (5). Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of Biskra that since the publication of The Garden of Allah and The Sheik, “the town has been filled with frustrated women.”23 These trends suggest that Hull’s novel had a powerful effect on her readers.

In 1919 Hull’s novel may have looked like a “simple tale,” but critics were soon writing about The Sheik as a symptom of cultural decline. Q. D. Leavis’s Fiction and the Reading Public is a key summary of this critical development. Leavis is most concerned with the fact that “what is considered by the critical minority to be the significant works in fiction”—the novels of D. H. Lawrence, Joyce, Woolf, and Forster—are not read by the public or stocked by libraries or booksellers. Leavis argues that The Rainbow, for example, is not read because it moves “in a slow, laboured cycle” (226), and the reading public is not willing to make this kind of commitment. Comparing contemporary best-sellers to the glory days of the eighteenth-century novel, Leavis’s main critique of current fiction—“as distinct from literature”—is that it uses stale language that elicits an equally stale response from its audience.24

The idiom that the general public of the twentieth century possesses is not merely crude and puerile; it is made up of phrases and clichés that imply fixed, or rather stereotyped, habits of thinking and feeling at second-hand taken over from the journalist. … To be understood by the majority [a serious novelist] would have to employ the clichés in which [the general public] are accustomed to think and feel, or rather, to having their thinking and feeling done for them…. The ordinary reader is now unable to brace himself to bear the impact of a serious novel. (255–257)

Authors like Hull, Leavis asserts, descend to the readers’ idioms of banality. Leavis pinpoints as the primary problem with popular fiction “the consistent use of clichés (stock phrases to evoke stock responses)” (243). A “stock response” is inauthentic or ersatz, “interfering with the reader’s spontaneities” (244). A spontaneous response, however, does not mean doing what comes naturally, but rather registering an experience of “shock.” Leavis contrasts “the popular novels of the age” that “actually get in the way of genuine feeling and responsible thinking by creating cheap mechanical responses” (74) to “the exhilarating shock that a novel coming from a first-class fully-aware mind gives” (74). The metaphors Leavis uses to describe stock responses are notably somatic—“Novel-reading now is largely a drug habit” (19), she asserts, a “masturbatory” (165) form of self-indulgence—while the experience of “shock” is more cerebral, with the emphasis more on self-conscious thinking than feeling.

Leavis’s example of the deluded reader is Gerty MacDowell in Ulysses, whose consciousness has been colonized by popular women’s fiction. “For Gerty MacDowell every situation has a prescribed attitude provided by memories of slightly similar situations in cheap fiction; she thinks in terms of clichés drawn from the same source, and is completely out of touch with reality. Such a life is not only crude, impoverished, and narrow, it is dangerous” (245). Such a life is also fiction, but never mind. The example is instructive because Leavis locates in it two kinds of readers and two kinds of author-reader relationships. Gerty’s relationship to popular fiction is one of uncritical identification; the space between the page and the reader has collapsed. However, as discussed in chapter 1, Joyce inscribes an ironic distance between Gerty and the reader of his “serious” novel. This effect of estrangement, for Leavis, allows for the “impact” of modernist fiction’s “shock.”

If Joyce had depicted Gerty as living twenty years later, she would likely be imagining Leopold Bloom through the lens of desert romances, the contemporary equivalents of The Lamplighter and The Princess’s Novelettes. Leavis notes that “ten of the fourteen novelists advertised by the 3d. circulating libraries [in a catalog] specialize in fantasy-spinning” (54). A striking number of the titles are desert romances: The Desert Dreamers, The Lure of the Desert, Sands of Gold, The City of Palms, The Mirage of the Dawn, and East o’ the Sun (54). Leavis argues that reading “novels like The Way of an Eagle, The Sheik, [and] The Blue Lagoon” constitutes “a more detrimental diet than the detective story in so far as a habit of fantasying will lead to maladjustment in actual life” (54–55). Presumably, one could put the methods of detection to use in real life, while “fantasying” lacks such applications and will cause the dreamer to misread real life. Leavis never substantiates this genre- and gender-biased claim. Her argument about the connection between cliché and fantasy-driven readerly pleasure leans most heavily on women’s romance, and The Sheik is one of the central pillars. In a questionnaire about popular fiction that Leavis distributed to sixty authors, The Sheik is one of four titles specified as examples of “great bestseller[s]” (44). One respondent singles out The Sheik as his primary example of “rotten primitive stuff” (46). In demonstrating how low the popular novel has sunk, Leavis suggests that we “Compare Pamela with The Sheik, which in the year of its publication was to be seen in the hands of every typist and may be taken as embodying the typist’s day-dream, and it is obvious that Pamela is only incidentally serving the purpose for which The Sheik exists and even then serving it very indifferently” (138). Rather than providing a “scaffolding for castle-building” (138) and escapism, the eighteenth-century novel, for Leavis, promoted the destruction of illusions and fantasy.

Leavis’s throwaway line about “the typist’s day-dream” reveals how closely associated female audiences and formulaic language are in the modernist critical paradigm of pleasure. In “The Little Shopgirls Go to the Movies,” for example, Siegfried Kracauer argues that “Sensational film hits and life usually correspond to each other because the Little Miss Typists model themselves after the examples they see on the screen.”25 Again, the iconographic typist (for Eliot in The Waste Land, among other modernist fictions; we will meet her again in chapter 6) stands in for a whole demographic of female consumers whose fantasies are transparent and mindlessly imitative. The typist is a figure of repetition rather than originality who absorbs what is put before her rather than producing her own work. Likewise, Leavis imagines fantasy, as both an activity and a literary genre, as a passive and mindless repetition of bromides. (The women who are supposedly trying to find their own sheiks in Biskra represent an intriguingly active response to fantasy texts.) For Leavis, fantasy is divorced from the processes of creativity, distinction, and activity, all of which she associates with modernist fiction. “A habit of reading poor novels,” Leavis argues, “not only destroys the ability to distinguish between literature and trash, it creates a positive taste for a certain kind of writing, if only because it does not demand the effort of a fresh response, as the uneducated ear listens with pleasure only to a tune it is familiar with” (136–137). Here again is the adjuration of the leisure theorists, who urge consumers to develop tastes for more bracing and challenging activities.

Novelty and repetition are important structural issues for pleasure and aesthetic response. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, repetition has a pathological, infantile character. Freud asserts that for adults, “Novelty is always the condition of enjoyment,” whereas “children never tire” of repeating the same game or story (42). The repetition compulsion, of course, challenges this principle, but the way Freud chooses to characterize it (as a compulsion) suggests that it is an aberrant or undisciplined inclination. Stein’s repetition was characterized as infantile on these grounds. By contrast, innovation—the cult of novelty, the shock of the new—signals intelligence, thoughtfulness, and sophistication: “Novelty is better than repetition,” Eliot writes in “Tradition and the Individual Talent.”26 A similar assumption underlies the dismissal of formulaic genres as appealing to uneducated or undiscerning readers. Repetition may occur on the level of plot, as serial or genre fiction conforms to established patterns that have proven successful, or on the level of phrases, as clichés or word combinations are so familiar as to be drained of meaning. Bliss, says Barthes, summing up the view of aesthetic modernism, “may come only with the absolutely new, for only the new disturbs (weakens) consciousness (easy? Not at all: nine times out of ten, the new is only the stereotype of novelty)” (40). The truly new, then, is a special category of innovation that disrupts or “shocks” the reader. “The stereotype is the word repeated without any magic,” and Barthes pronounces it “nauseating” (42–43). “The bastard form of mass culture is humiliated repetition” (41–42).

But how much innovation can an audience absorb? At what point does innovation become disorienting and off-putting? Some degree of linguistic or structural familiarity is a necessary condition of intelligibility. Umberto Eco points out that modernism’s characterization of popular or mass culture as works of “repetition, iteration, obedience to a preestablished schema, and redundancy” that are “pleasurable but non-artistic”27 is unsustainable, for even experimental works necessarily play on schema and formula. By the same token, serial works demonstrate variation as well as repetition, and “even the most banal narrative product allows the reader to become, by an autonomous decision, a critical reader, able to recognize the innovative strategies” (200). One reviewer of the films The Sheik and The Son of the Sheik noted that they appealed as a counterpoint to “the drabness” and “ordinariness of … everyday life,” but complains, “what a pity that the story of both these films is so similar. A little inventiveness would not have come amiss and the later film would have been better for it.”28 Contemporary psychological studies suggest that people are most receptive to experiences that strike a balance of the novel and the familiar.29 Radical invention can be alienating, and rote predictability can be boring, but the right combination is captivating.

Women in great numbers responded to the desert romance, it seems, out of an attraction to a kind of novelty (alterity) combined with an antinovelty (formula). The former includes an exotic locale, a certain explicitness about women’s desire, and the appearance of a kind of man one ordinarily didn’t meet, apparently, if one was a typist; the latter includes formulaic repetitions, clichés of genre, stereotypes, and conventional plots. This has implications for both gender politics and language. The success of Hull’s novel suggests that fantasies of stereotypical gender roles continued to have a hold on the imagination at the same time that women were struggling for political equality. Even as erotic representation is often construed as the realm of transgression and novelty, fantasy and pleasure may also actively resist innovation, favoring stereotypes and cliché scenarios, which makes them antithetical to prevailing modernist tenets of originality.

For Leavis, the antidote to books such as The Sheik is modernist fiction, “in which words are used with fresh meanings and for ends with which [the reader] is unfamiliar”: it delivers “shocks” to its readers. If popular reading is a narcotic, modernism is bracingly therapeutic (257). If only Gerty MacDowell read Ulysses instead of The Lamplighter, and typists read The Rainbow instead of The Sheik, the reading public would be uplifted. This corrective or rehabilitative approach is predicated on an understanding of pleasure as a kind of false consciousness. But modernist shock is a reading experience that runs counter to the reading public’s evident tastes. Fantasy and its most solicitous literary forms, including romance and pornography, imagine pleasures that are, strikingly often, regressive or banal. Although a primary goal of modernism is to train readers to enjoy what is challenging and unfamiliar, there are concessions to less exalted tastes throughout modernist works. Lawrence’s own fiction calls into question the very terms of his criticism of The Sheik in ways that indicate he recognized that repetition, cliché, and stereotype have attractions that can be just as powerful as novelty and innovation.

In “Surgery for the Novel—or a Bomb” (1923) Lawrence begins by making the same generic distinction that Leavis does between “serious” and popular fiction. He sees “On the one hand the pale-faced, high-browed, earnest novel, which you have to take seriously”—“Ulysses and … Miss Dorothy Richardson and M. Marcel Proust”—and “on the other, that smirking, rather plausible hussy, the popular novel”—“the throb of The Sheik and Mr. Zane Grey.”30 However, Lawrence faults Joyce, Proust, Richardson, and Stein for self-absorption, “self-consciousness,” and abstraction that fail to deliver the “new, really new feelings, a whole line of new emotion, which will get us out of the emotional rut” (520). He extends Leavis’s criticism of fantasy fiction—that it is “completely out of touch with reality” and interferes with “spontaneities”—to the serious novel. In a 1928 letter, Lawrence opines that “James Joyce bores me stiff—too terribly would-be and done-on-purpose, utterly without spontaneity or real life.”31

The flip side, the popular novel, is pedestrian and unoriginal: “Always the same sort of baking-powder gas to make you rise” (Phoenix, 519). However, sameness, repetition, does not have the negative connotations for Lawrence that it does for Leavis, and novelty is not a supreme virtue. Lawrence’s own work, as he knew, was highly repetitive. On this count, he responded to critics in his 1919 foreword to Women in Love: “In point of style, fault is often found with the continual, slightly modified repetition. The only answer is that it is natural to the author: and that every natural crisis in emotion or passion or understanding comes from this pulsing, frictional to-and-fro, which works up to culmination.”32 Repetition, then, is “natural” for Lawrence; it is what comes naturally, spontaneously.

Just as Lawrence defended and practiced a certain kind of repetition, he was skeptical of novelty as an aesthetic goal. In “Introduction to These Paintings,” he writes,

A cliché is just a worn-out memory that has no more emotional or intuitional root, and has become a habit. Whereas a novelty is just a new grouping of clichés, a new arrangement of accustomed memories. That is why a novelty is so easily accepted: it gives the little shock or thrill of surprise, but it does not disturb the emotional and intuitive self. It forces you to see nothing new. It is only a novel compound of clichés.33

Blatant novelty is no more desirable than “shock,” as evidenced by the fact that Lawrence yokes the word that Leavis favors with “thrill,” which Lawrence uses to distinguish empty modern sex from more profound erotic experience. For Lawrence, the pursuit of novelty in and of itself produces overly self-conscious, too-deliberate art. The true artist, then, struggles between novelty and cliché. Lawrence perceived this challenge in Cézanne’s attempt to transcend cliché and shallow novelty at the same time: “Cézanne’s early history as a painter is a history of his fight with his own cliché…. His rage with the cliché made him distort the cliché sometimes into parody” (576). This is a fair description of Lawrence’s own writing, which often verges on self-parody.

As formulaic as the popular novel is, Lawrence concedes that it invariably elicits a strong somatic response: a “throb,” a “rise,” whereas the “serious” novel drives people further into their own minds. The Sheik is the paradigmatic popular novel for Lawrence in “Surgery for the Novel.” He writes that “The mass of the populace ‘find themselves’ in the popular novels. But nowadays it’s a funny sort of self they find. A Sheik with a whip up his sleeve, and a heroine with weals on her back, but adored in the end, adored, the whip out of sight, but the weals still faintly visible…. Sheik heroines, duly whipped, wildly adored” (519). Lawrence’s rhythmic, breathless language here betrays the stylistic resemblance between his writing and Hull’s; his exaggerated paraphrase of The Sheik also indicates how his imagination ran in the same direction as hers. Ahmed strikes an insubordinate servant in one brief scene of The Sheik and a horse in another, but he does not whip Diana. Lawrence’s remarks suggest that he may have conflated the novelistic Sheik with the cinematic one, Valentino, whose sadomasochistic scenes on the screen were legendary.34 Valentino was, as Linda Ruth Williams points out, “the first major male star to be specifically marketed for a female audience”; this is reflected in Lawrence’s portrayal of the star as a confection designed for ravenous women’s appetites.35 In his 1928 essay “Sex Versus Loveliness,” Lawrence writes that “the so-called beauty of Rudolph Valentino … only pleases because it satisfies some ready-made notion of handsomeness,” arguing that such stereotypical sex appeal is inferior to the “greater essential beauty” of “Charlie Chaplin’s odd face.”36 In fact, Valentino’s looks and screen presence represented a challenge to dominant Hollywood conceptions of masculinity as well as ethnicity. At the same time that Lawrence wanted to dismiss Valentino as a cliché, he also recognized the star’s appeal and perhaps even brought it to bear on his own charismatically exotic, brooding leading men. After Valentino’s early death in 1926, Lawrence was more sympathetic; his poem “Film Passion” claims that the female cinema mob killed the star.37

Although Lawrence distances both the popular novel and film from significant fiction like his own, there are episodes of sadomasochistic eroticism in Hull’s novel that seem right out of Lawrence’s own pages. For example, in a highly charged scene, Diana sees Ahmed brutally break a colt, an encounter that is reminiscent of Gudrun and Ursula watching Gerald terrorize a mare in Women in Love.38 Hull pays as much attention to the rhetoric of “will” as Lawrence does, making it a central trope of Ahmed’s dynamic with Diana. Moreover, Ahmed is a man who commands other men, a posture that Lawrence found fascinating. In many ways, then, it is not just the general populace but also Lawrence who “finds himself” in Hull’s novel. Lawrence complains in a 1926 letter to publisher Thomas Seltzer that he has been asked “to come back with a bestseller under my arm. When I have written ‘Sheik II’ or ‘Blondes Prefer Gentlemen,’ I’ll come. Why does anybody look to me for a best seller? I’m the wrong bird.”39 The parodic titles reflect the serial quality of popular novels (yet another dose of baking powder), but the pleasures of popular fiction were not as foreign to Lawrence as he claimed. Indeed, as David Trotter points out, Lawrence “worried about the resemblance between his own radical revaluation of sexuality and the purple passages of the romancers” (English, 188). I will argue that, in a sense, Lawrence did write “The Sheik II” insofar as he adapted many of Hull’s tropes for his own work.

After “Surgery for the Novel—or a Bomb,” Lawrence returned to Hull in “Pornography and Obscenity” (1929), an essay prompted by the censorship of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He maintains that genuine pornography can be recognized “by the insult it offers, invariably, to sex, and to the human spirit. Pornography is the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it”:

The pornography of today, whether it be the pornography of the rubber-goods shop or the pornography of the popular novel, film, and play, is an invariable stimulant to the vice of self-abuse, onanism, masturbation, call it what you will…. And the mass of our popular literature, the bulk of our popular amusements just exists to provoke masturbation. (Phoenix, 178)

Unlike Leavis, Lawrence does not limit this theory of pernicious masturbation to popular literature: “most of our modern literature,” he asserts, shows symptoms of “self-abuse” (180). Building on this premise, Lawrence goes on to draw some unexpected distinctions among a group of diverse texts. Weighing Boccaccio, Rabelais, Richardson, Brontë, Fielding, and Keats against one another, Lawrence now includes Hull: “I’m sure poor Charlotte Brontë, or the authoress of The Sheik, did not have any deliberate intention to stimulate sex feelings in the reader.” This is an odd interpretation, as one only has to read a couple of pages of The Sheik to realize that it is meant precisely to “stimulate sex feelings.” Lawrence continues, “Yet I find Jane Eyre verging towards pornography and Boccaccio seems to me always fresh and wholesome” (174). The distinction is grounded on how the author handles his or her material. Pornographic texts treat sex as furtive and dirty instead of clean and healthy. Jane Eyre’s gothic thrills are more sneaky and manipulative, to Lawrence, than the overt bawdiness of Boccaccio. Lawrence also casts this as a question of audience, of the group versus the individual: “The mass is for ever vulgar, because it can’t distinguish between its own original feeling and feelings which are diddled into existence by the exploiter…. The mob is always obscene, because it is second-hand…. It is up to the individual to ask himself: Is my reaction individual, or am I merely reacting from my mob self?” (172). What accounts for Lawrence’s new reading of The Sheik, rescuing it from the realm of the “rubber-goods shop” and promoting it several notches up the literary genre ladder?

The Sheik is less closely related to Jane Eyre than it is to the anonymous mid-nineteenth-century pornographic classic The Lustful Turk. Emily Barlow, the supposed narrator of this epistolary novel, is a British ingénue traveling in “the East.” She is swept off her horse and captured by Ali, the Dey of Algiers. (“Dey” was the title for governor used before the French conquest in 1830.) The Dey carries Emily to his “sumptuous chambers,” complete with beautiful clothes, attentive maids, and contemporary novels. This gorgeous but barbarous swain immediately assaults Emily’s virginity. Although she puts up a fight, the protest quickly gives way to, as Emily reports, “a sensation it is quite impossible to describe … [a] sudden, new and wild sensation blended with … shame and rage.”40 Emily’s archetypically pornographic awakening—the rape that turns to arousal—is strikingly like Diana Mayo’s, although it takes about a tenth of the time to achieve. Within just a few pages, Emily is utterly in thrall to the Dey and his wicked ways, and in no time she proves to be a gifted libertine. It is only with great reluctance that at the end of the novel she is shipped home to England, her erotic education complete. “I will never marry,” Emily writes, “until I am assured that the chosen [man] possesses sufficient charm and weight not only to erase the Dey’s impression from my heart, but also from a more sensitive part.” The flimsy way marriage is invoked at the end of The Lustful Turk—more as a setup for a coy joke than anything else—is typical of pornography, in the world of which marriage is not just insignificant, but a downright turn-off. Just so, the marriage at the end of The Sheik is gratuitous, and Hull’s main concession to traditional novel conventions is perfectly in keeping with its pornographic progenitor.

As Allison Pease has shown, many modern writers, including Lawrence, “strove to incorporate mass-cultural pornographic representations of the body, sex, and sexuality into their works even as they affirmed the aesthetic value of their appropriations” (xii). Pease contends that the only representations of sexualized bodies available to the modernists were in conventional pornography, but Lawrence knew—and he says as much in “Pornography and Obscenity”—that popular fiction was already representing sex, if not in the explicit fashion of pornography, then in a language that we might call “pornoromance,” the idiom of the desert romance. Indeed, Billie Melman argues that “the desert-passion industry” (104) is “one of the earliest examples of mass, commercialised erotic literature” (104).

Isolated, remote, striving to minimize historical referents and problems except those that are part of the erotic frisson, the setting of desert romance resembles nothing so much as what Steven Marcus has called “pornotopia.”41 The complex double identification that Hull cultivates—the reader’s alignment with Ahmed’s desires against Diana’s prudish arrogance—is uncharacteristic of romance. But in pornography—most notoriously, in a text such as Sade’s Justine—the reader is commonly primed to will the heroine’s chastisement or comeuppance. Just as pornography endlessly recycles a limited vocabulary without, apparently, any inhibition of its pleasurable affect, so Hull (and her readers) never seems to tire of the metaphors of smoldering passion. The episodic pacing of The Sheik is also reminiscent of pornography; the way Diana comes to each encounter with Ahmed as if for the first time, her feelings and his body described with only subtle variations from the last time, resembles the phenomenon of “renewable virginity” in pornography, where each episode presupposes astonishments equal to the last.

The Sheik gives insight into many of Lawrence’s preoccupations: female consciousness, sexuality, and pleasure. Hull achieves a strong readerly response that Lawrence valued highly; she connects with the reader in a way Lawrence knew was important, even though he disagreed with the direction Hull takes this alliance. The relationship between the desert romance author and her readers is as intimate as the pornographer’s with his audience, reflecting a confidence that the same scenario, told again and again from a slightly different angle or with a slightly different set of props, is sure to incite arousal. Although in Women in Love, Birkin tells Hermione that she is incapable of being “a spontaneous, passionate woman … with real sensuality,” and that she wants only “pornography—looking at yourself in mirrors” (42), nowhere are clichés so effective, and readerly affect so unmediated, as in pornography. In the realm of pornography, the stock response is the ideal response, as the reader feels pleasure in tandem with the characters. As Pease describes it, pornography “invites readers to indulge their own sensations through a mimetic imaginative practice” (8). Although Hull never explicitly mentions body parts or acts, she expertly marshals euphemism so that the reader has no doubt when the sheik is aroused and when he and Diana are “intimately connected.”

There is a suggestive correlation between pornography’s arousing function and Lawrence’s desire to wrest the reader out of passivity and into spontaneity, reviving the libidinalized body from the stranglehold of consciousness. Lawrence’s reclassification of The Sheik in “Pornography and Obscenity” indicates that he understood the attractions of these pleasurable genres even as he tried to turn them toward another ideological and affectual purpose. Most tellingly, in the period between “Surgery for the Novel” and “Pornography and Obscenity,” Lawrence’s own fiction took a decidedly Hullian turn.

BECOMING WOMAN

As several critics have noted, Lawrence’s story “The Woman Who Rode Away” (1924) and, even more explicitly, his novel The Plumed Serpent (1926), reference and rewrite The Sheik.42 In both, an aloof modern heroine (American in one case, British in the other) goes to Mexico and falls in thrall to swarthy “Indian” men whose ideology is founded on Aztec cosmology, human sacrifice, and male dominance. But while critics concur that Lawrence was “adapting the clichés of the desert romance” (Horsley, 114) and “at once invoking and denigrating” popular romance (Trotter, English Novel, 188) in these works, the broader motivation for his turn to The Sheik—as a means of directing reading and erotic pleasure together in a way that lays the groundwork for his most well-known novel on contemporary sexuality, Lady Chatterley’s Lover—has not yet been recognized.

“The Woman Who Rode Away” and The Plumed Serpent are variations on the common interwar theme of leaving a troubled Britain for another, less apparently complicated country. Lawrence had an unusually literal understanding of this theme, as he enacted this flight himself, to Australia, Italy, New Mexico, and other locales that seemed to offer alternatives to a moribund interwar Britain. Unlike Hull, who once praised “the really fine work that the French Government has done” in Algeria,43 Lawrence was critical of imperialism, and his fictions support the autonomy of native cultures. Mexico, like Algeria, offered racial, religious, and linguistic otherness, a foreign landscape, and a “primitive” culture that seemed free of the gender upheavals of Britain. Finally, neither Algeria nor Mexico has a history of British imperialism (but rather French and Spanish), so the exoticism is less fettered by political complications.

“The Woman Who Rode Away” presents many of the themes that are explored in The Plumed Serpent, but in a different tone. The unnamed American female protagonist lives in Mexico with her children and her husband, who “admired his wife to extinction…. Like any sheikh, he kept her guarded.” Her husband is only a sheikh in his possessiveness; he has been unable to master her in the ways that matter to Lawrence.

At thirty-three she really was still the girl from Berkeley, in all but physique. Her conscious development had stopped mysteriously with her marriage, completely arrested. Her husband had never become real to her, neither mentally nor physically. In spite of his late sort of passion for her, he never meant anything to her, physically. Only morally he swayed her, downed her, kept her in an invincible slavery.44

Like Diana Mayo, she is not yet a “real” woman; the ritual that was supposed to launch her into womanhood, marriage, has been ineffective except as a spiritual suppressant. She hears about a local tribe of Indians who are the “descendants of Montezuma and the old Aztec or Totonac kings” (550), and the next time her husband is traveling, she ventures out by horseback into the hills alone, where a group of “darkfaced,” “strongly-built” Indian men surround her. In a less dramatic version of Hull’s kidnapping scene, one of the men seizes the reins of the woman’s horse and they lead her to their village, where they drug her and keep her captive. This is no sexual utopia; there is “nothing sensual or sexual” (560) in the way the men regard the woman. One man is assigned as her guard. They are alone together constantly, but to the woman,

He seemed to have no sex, as he sat there so still and gentle and apparently submissive with his head bent a little forward, and the river of glistening black hair streaming maidenly over his shoulders.

Yet when she looked again, she saw his shoulders broad and powerful, his eyebrows black and level, the short, curved, obstinate black lashes over his lowered eyes, the small, fur-like line of moustache above his blackish, heavy lips, and the strong chin, and she knew that in some other mysterious way he was darkly and powerfully male. (567)

The fault, Lawrence implies, is hers: she is so sexless that she is unable to recognize the allure of her “darkly and powerfully male” captor. Even Diana Mayo at her most resistant is aware of “the Sheik’s vivid masculinity.” In Lawrence’s story, instead of treating the woman like a sexual being, the men subject her to earnest lectures about how the white man has stolen the Aztec sun and moon, and how only the sacrifice of a white woman will return the cosmos to its proper order. As a result of her immersion into the rhythms and cycles of nature, the woman

seemed at last to feel her own death; her own obliteration. As if she were to be obliterated from the field of life again…. Her kind of womanhood, intensely personal and individual, was to be obliterated again, and the great primeval symbols were to tower once more over the fallen individual independence of woman. The sharpness and the quivering nervous consciousness of the highly-bred white woman was to be destroyed again, womanhood was to be cast once more into the great stream of impersonal sex and impersonal passion. (569)

To be cast into “impersonal sex” and “impersonal passion” is not to be made sexually passionate, but rather to find one’s symbolic place in the cosmos. Diana Mayo’s being “made to feel acutely that she was a woman, forced to submit to everything to which her womanhood exposed her” is the prelude to ardor. Lawrence’s modern woman, by contrast, is obliterated and acquiesces to the ancient order. In the final scene of the story, the woman is taken into an ice cave, fumigated, stripped naked, and laid on a table, and the story ends with the men gathered around her, watching the sun’s rays creeping into the cave and waiting for a priest to plunge a knife into her. The scene could have been a ceremonial orgy, as the woman is surrounded by naked men “in the prime of life”; instead, it becomes a deathly punctuation, a numbness. It is the anti-Sheik, in which the woman is not metaphorically destroyed, as Diana is by Ahmed in order to be reborn, but is poised to be literally killed. Unlike The Sheik, which highlights Diana’s every physical sensation, Lawrence’s woman, drugged and disoriented, feels almost nothing. There is a tension throughout the story between its erotic potential and the frigid effect (matching the chill in the ice cave) of the men’s and the narrator’s solemn, stilted sermons. This is no Story of O or Philosophy in the Bedroom, where lectures give the characters and readers time to rest up for the next sexual escapade, but rather a droning soundtrack that attempts to diminish the story’s titillating elements and a prurient response from the reader. Lawrence takes up Hull’s thrilling fantasy of escape and submission but tries to prevent his reader from having the same kind of erotic pleasure by literally lowering the temperature and shifting to a story of negation in the service of a lesson on “great primeval” culture.

Lawrence gives more attention to the erotic content of Hull’s novel in The Plumed Serpent, the third of his so-called leadership novels, where antidemocratic politics are combined with male domination. The first two leadership novels (Aaron’s Rod and Kangaroo) feature a British male protagonist who is disillusioned with postwar democracy and searches for a political “master” abroad, but can never bring himself to fully submit.45 In The Plumed Serpent, the submission of Kate Leslie, a middle-aged woman, is achieved through a heavy narrative reliance on The Sheik. In Mexico City, Kate hears about a growing underground movement calling for the return of the gods of antiquity, the Aztecs’ plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl, the god of culture, and Tlaloc, the god of fertility. When she meets the powerfully charismatic general Cipriano, who, with Don Ramon, is leading the Quetzalcoatl movement, Kate has a strongly imaginative response: “There was something undeveloped and intense in him, the intensity and the crudity of the semi-savage…. Something smooth, undeveloped, yet vital in this man suggested the heavy-ebbing blood of reptiles in his veins” (67). This is the first of many reptilian metaphors that prove aphrodisiac to Kate. When she contemplates returning to America, the thought of Cipriano’s body slithering around hers makes her hesitate: “She felt like a bird round whose body a snake has coiled itself. Mexico was the snake” (72). The discourse of colonialism and imperial conquest are reversed in this embrace: the “conquering” race finds itself squeezed by the potent “semi-savages” of Mexico—and is aroused. Throughout the novel, Lawrence’s idioms of eroticism—the virile and animalistic Quetzalcoatl men, the conflict between Kate’s “modern” ideas and the allure of gender regression—strongly resemble Hull’s. At one point, for example, Diana imagines the sheik’s arms around her as “the coils of a great serpent closing round its victim” (96). Even in the transposition of the setting to Mexico, Hull’s desert romance tropes creep in. Kate thinks of the Quetzalcoatl women as “harem type[s]” with “harem tricks” (397). Western influences have not diminished Cipriano’s primitive virility: his Oxford education “lay like a film of white oil on the black lake of his barbarian consciousness” (82). Similarly, Hull’s Ahmed manages to keep his nails pared and his robes spotless, but these Western conventions do not ruin his primitive appeal. As Hull’s Diana is able to dominate British and American men but meets her match with Ahmed, so the Quetzalcoatl men display a kind of masculinity Kate has never seen before. Lawrence’s attention to the men’s bodies, like Hull’s to Ahmed’s firm limbs and his revolver “thrust” in his waistband, leaves no doubt about where the source of their power is: “He had a secret, important to himself, on which he was sitting tight”; “on his thighs the thin linen seemed to reveal him almost more than his own dark nakedness revealed him. She understood why the cotton pantaloons were forbidden on the plaza. The living flesh seemed to emanate through them” (81; 183–184).

As with Hull’s tale, Kate must undergo a stripping away of her values, an unknowing, in order to discover what is important.

“Ah!” she said to herself. “Let me close my eyes to him, and open only my soul. Let me close my prying, seeing eyes, and sit in dark stillness along with these two men. They have got more than I, they have a richness that I haven’t got. They have got rid of that itching of the eye, and the desire that works through the eye. The itching, prurient, knowing, imagining eye, I am cursed with it, I am hampered up in it. It is my curse of curses, the curse of Eve. The curse of Eve is upon me, my eyes are like hooks, my knowledge is like a fish-hook through my gills, pulling me in spasmodic desire. Oh, who will free me from the grappling of my eyes, from the impurity of sharp sight! Daughter of Eve, of greedy vision, why don’t these men save me from the sharpness of my own eyes!” (184)

Kate’s “itching, prurient, knowing” eye and her “spasmodic desire” evoke original sin, for which she blames Eve’s lustful, restless vision. In an odd adaptation of Genesis, Kate asserts that the Quetzalcoatl men have managed to shed the curse of questing for knowledge as well as the tyranny of the sense of sight. Released from “spasmodic desire” and shame, content to be in a pre-edenic darkness, they have attained a more primal kind of knowledge that leads into political primitivism. Antidemocratic and anti-Marxist, the Quetzalcoatl movement wants to reinstate the Aztec religion and racial and gender hierarchy. Ramón declares himself “the First Man of Quetzalcoatl,” and Cipriano is named the “First Man of Huizilopochtli” (261), the god of war and sacrifice. When Cipriano asks Kate to marry him and become “First Woman of Itzpapoltl,” she initially resists, wondering “how could she marry Cipriano, and give her body to this death?” (248). But

she felt herself submitting, succumbing. He was once more the old dominant male [and] she was swooned prone beneath, perfect in her proneness.

It was the ancient phallic mystery…. Ah! and what a mystery of prone submission, on her part, this huge erection would imply! … Ah! what a marriage! How terrible! and how complete! … She could conceive now her marriage with Cipriano; the supreme passivity, like the earth below the twilight, consummate in living lifelessness, the sheer solid mystery of passivity. (311)

Lawrence echoes Hull’s panting, swooning language glorifying erotic surrender. As with Hull, acquiescence comes with an acceptance of unknowing; however, there is an important difference between Kate’s “prone submission” and Diana’s. At the beginning of The Plumed Serpent, Kate’s libidinal drive is a crucial part of her attraction to the Quetzalcoatl men, and this is where the desert romance formula is most powerful for Lawrence. However, by the end of the novel, with Kate’s marriage to Cipriano, this changes. One of many conditions Cipriano imposes upon her is that they must maintain emotional and sexual distance, and this includes control of her orgasm.

He made her aware of her own desire for frictional, irritant sensation … and the spasms of frictional voluptuousness.

Cipriano … refus[ed] to share any of this with her… When, in their love, it came back on her, the seething electric female ecstasy, which knows such spasms of delirium, he recoiled from her…. And succeeding the first moment of disappointment, when this sort of “satisfaction” was denied her, came the knowledge that she did not really want it, that it was really nauseous to her. (421)

Critics have generally understood this passage as Cipriano demanding that Kate give up clitoral “spasms of frictional voluptuousness” for more “potent” (and presumably, less labor-intensive for Cipriano) vaginal orgasms. This request that she adjust her orgasm to suit him—to renounce her “seething electric female ecstasy”—is a stark example of Lawrence’s disciplinary approach to pleasure. Banning “frictional, irritant sensation” and “voluptuousness,” he demands distance and self-conscious unconsciousness (no easy feat) in its place. Lawrence never loses sight of the somatic, but he expands the physical description to include more abstract spiritual and moral rhetoric. More than that, though, the language here signals a quashing of conventional pleasure not just in Kate but also in the reader. Words like “disappointment” and “nauseous” are incongruous in what could be erotic scenes, particularly in a narrative that echoes the arousing tropes of desert romance and pornography. While such counterintuitive language might, in the hands of Joyce, serve a perversely libidinous function, Lawrence qualifies “ecstasy” and “spasms” as frantic and unsatisfying (“seething,” “delirium”), and the passage seeks to diminish rather than cultivate aphrodisiac effects.

A central difference between Hull and Lawrence is illustrated by a comparison of the “knowledge” Kate gains (that certain forms of sexual “satisfaction” are “really nauseous to her”) and Diana Mayo’s erotic enlightenment. As euphemistic as Hull’s narrative is, there is no question that Diana’s captivity is an erotic experience, whereas, as Marianna Torgovnick argues of The Plumed Serpent, “Kate’s attraction to Mexican men is clearly sexual, but—she insists and Lawrence insists—sex is not the point, is not more than a metaphor, a means to an end, an expression of larger, cosmic unities.”46 Sex is not exactly not the point; rather, what is at stake in this scene is the modification of sexual pleasure. Kate’s conclusion emphasizes this “sex suppression”: “Without Cipriano to touch me and limit me and submerge my will, I shall become a horrible, elderly female. I ought to want to be limited” (439). Falling into line with the primal order of Queztalcoatl means relinquishing her instinctual pleasures, which Lawrence codes as modern and false, and adopting prescribed ecstasies that are ostensibly more rewarding. In these scenes and others where his didacticism comes to the fore, Lawrence exerts the same attempted modification of pleasure over his reader that he does over his heroine.

Hull strives to isolate the fantasy of The Sheik from the “here and now” (as the hasty race change and marriage indicate), while Lawrence seeks to deploy fantasy toward an antierotic end. He adapts Hull’s narrative of female eroticism to achieve an embrace of Queztalcoatl authoritarianism and a concomitant “limiting” of women’s—and his reader’s—pleasure. Several central features of The Plumed Serpent—female submission, gender primitivism, orgasmic discipline, and readerly discipline—return in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence’s most explicit treatment of sexuality, in which pleasure is even more tightly controlled.

LADY CHATTERLEY: THE WOMAN WHO RODE BACK HOME

After several novels in which he searched for spiritual rejuvenation abroad, Lawrence turned back to England. In Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he relocates the struggle to the heartland. In this novel, more than any other, Lawrence challenges his modern characters and, by extension, his readers to adopt the right kind of pleasure and, specifically, the right kind of orgasm. Mellors’s hut, deep in the primeval forest, is the nerve center of this operation. Pornotopia is recast as a locale of spiritual resurrection effected through belabored pleasure and orgasmic discipline.

Although Lawrence cautioned against tendentious fiction, memorably remarking that “If you try to nail anything down, in the novel, either it kills the novel, or the novel gets up and walks away with the nail,”47 his own work, particularly near the end of his life, could be jarringly didactic. Lawrence’s interest in education and pedagogy, expressed both in his nonfiction and in pivotal scenes in his fiction, is also reflected in his rhetoric of sexuality. For many readers, it is this element of didacticism that is Lady Chatterley’s Lover’s flaw, rather than its language or subject matter. F. R. Leavis, for example, pronounced that Lawrence was “too possessed by his passionate didactic purposes” in his final major novel to achieve artistic greatness.48 The three separate versions of the novel that Lawrence produced indicate that this was a deliberate effect. Michael Squires, Ian Gregor, John Worthen, and other critics concur that Lady Chatterley’s Lover became more didactic and polemical as Lawrence revised it. “The final version,” Worthen notes, “is crisper, utterly unsympathetic, more economical, more useful to the novel’s polemic. For the final Chatterley is a crusading novel.”49

Lawrence set himself a number of narrative challenges in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He wanted to unite the body and the mind, but only in a very particular, “unconscious” way. He wanted to bring men and women together in a balancing act of union and separateness. He wanted to depict sexuality as it had never been done before, but he did not want his writing to have a pornographic effect on his audience. His high-minded purpose must always be evident, even though he claimed to be trying to wrest people out of their too conscious approach to sex. Lawrence left himself almost no margin for error. He wanted to use words like “fuck” and “cunt” in a way that was “clean” rather than obscene. He wanted his readers to understand and feel the quality of Connie’s pleasure, but their sexual investment could not be dirty, secretive, or masturbatory. Lawrence wanted a strong, invested engagement from his audience, but not the close readerly alliance between Hull and her audience. The sex scenes in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, then, steer a narrow pathway between arousal and restriction, intimacy and distance, pleasure and its extinction. Significantly, just when Lawrence was, in his own estimation, most ambitious and daring in reinventing the lexicon of sexual representation, he produced writing that feels both most like Hull’s and most determinedly opposed to it.

In “A Propos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” Lawrence again blames modern technologies of pleasure for the “counterfeit” and “false” feelings people have about love and sex. “The radio and the film are mere counterfeit emotion all the time, the current press and literature the same. People wallow in emotion: counterfeit emotion. They lap it up” (312). As much as Lawrence wanted to set Lady Chatterley’s Lover against the tropes of popular pleasure, Connie’s sexual awakening and key scenes of eroticism in the novel strongly echo Hull’s. Connie and Mellors both evoke, without exactly conforming to, the character types of desert romances. She is an unfulfilled, unrealized postwar woman married to a man who has been wrecked by the war. Mellors is a sort of sheik figure, a self-defined outsider whose identity is mysterious and contradictory. His first appearance in Lady Chatterley’s Lover unsettles Connie in a way that is similar to Ahmed’s debut in The Sheik. “A man with a gun strode swiftly, softly out after the dog, facing their way, as if about to attack them. … He seemed to emerge with such a swift menace. That is how she had seen him, like a sudden rush of a threat out of nowhere” (46). Lawrence qualifies this image: Mellors hardly sweeps Connie off her feet; he has softness and is “rather frail, really” (47). However, Connie consistently perceives him as “aloof, apart” and different from the modern men who surround her (except for Tommy Dukes, Lawrence’s surrogate in the novel, with whom Mellors shares a tendency to preach), and he never loses this liminal quality. Like Ahmed’s combination of “Western” and “Eastern” traits, Mellors’s aristocratic dignity and working-class earthiness allow him to be both familiar and foreign. “He had a natural distinction, but he had not the cut-to-pattern look of her class. … He had a native breeding” (274). His oscillation in and out of dialect is one sign of Mellors’s protean social identity; his brash pronouncements (“What is cunt but machine-fucking!” [217]) and often charmless approach (“‘Lie down!’ he said. ‘Lie down! Let me come!’ He was in a hurry now” [210]) keep the reader from seeing him as a conventional romantic figure. Most importantly, he holds himself apart from Connie. When they meet, Mellors “stared into Connie’s eyes with a perfectly fearless, impersonal look, as if he wanted to see what she was like. He made her feel shy” (46). Lawrence describes Mellors’s gaze as “impersonal” several times: he appraises Connie with “a curious, cool wonder: impersonally wanting to see what she looked like. And she saw in his blue, impersonal eyes a look of suffering and detachment, yet a certain warmth” (47). This is an indication of Mellors’s style of lovemaking and the language Lawrence will use to describe it: attenuated, rhythmic, and insistent, but also withholding and distant, putting space between itself and the reader.

Sex, for Lawrence, needs to be handled in a similarly defamiliarizing way. Throughout Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence treats sexual pleasure as analogous to textuality. When they are young, Connie and her sister glibly regard “the sex thing” as an experience that “marked the end of a chapter. It had a thrill of its own too: a queer vibrating thrill inside the body, a final spasm of self-assertion, like the last word, exciting, and very like the row of asterisks that can be put to show the end of a paragraph, and a break in the theme” (8). This is the way readers consume pornography, according to Lawrence: they obtain a quick fix instead of having an expansive, profound experience. They are one with the text, in a masturbatory sense, and then they move on. Unlike a text such as Hull’s, in which the prose is a transparent medium for exciting content, Lawrence’s novel continually draws the reader’s attention to its language through conspicuous repetition, authorial intrusions, and other techniques that impose distance between the acts on the page and the reader’s body. Lawrence wants his reader to pay attention to textuality itself rather than indulge in mimetic pleasure.

In “Apropos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” Lawrence casts postwar sexuality as a predicament of repetition. “The act tends to be mechanical, dull,” he asserts, a “wearying repetition over and over, without a corresponding thought, a corresponding realisation. Now our business is to realise sex” (308). This enervating iteration structurally resembles Lawrence’s own writing, with its “continual, slightly modified repetition.” Although Lawrence uses the language of orgasm to describe his own style—“this pulsing, frictional, to-and-fro, which works up to culmination”50—he specifies that this rhythm, like bodies moving against each other, is desirable only because its “culmination” or “crisis” is characterized by illumination or “understanding.” To be meaningful, it must be accompanied by “realization.” Lawrence tries to effect this through didactic explanation, an imposed rhetorical disparity between the acts described and the narrator’s exposition of their significance.

The sexual interludes in Lady Chatterley’s Lover model different kinds of erotic and readerly response. Early on in the novel, sex is regarded by the characters as “a cocktail—they both lasted about as long, had the same effect, and amounted to about the same thing” (64). Clifford is mechanical in his attitude, hoping that he and Connie can “arrange this sex thing as we arrange going to the dentist” (44). Lawrence describes Connie’s sex with the writer Michaelis in an explicit but perfunctory way, as a “thrill” that is over the moment the scene ends. (The case of Michaelis demonstrates it is not just women’s orgasm that concerns Lawrence.) Disappointed because Michaelis comes too quickly, Connie figures out how to keep him inside her afterward, “while she was active, wildly, passionately active, coming to her own crisis” (29). Lawrence signals to the reader that this too is false pleasure: selfish, deliberate, and isolated. “She still wanted the physical, sexual thrill she could get with him, by her own activity, his little orgasm being over. … It was an almost mechanical confidence in her own prowess” (29–30). Notably, Lawrence does not describe the orgasm, but only reports that it is achieved, like a task checked off a list. There is no “realization” or insight.

Connie’s orgasm with Michaelis approaches, but is not nearly as dreadful as, Bertha Coutts’s diabolical desire and her beakish, castrating anatomy that Mellors describes later in the novel. His lengthy, angry tirade emphasizes that it was Bertha’s orgasmic etiquette that tore them apart: “She’d try to lie still and let me work the business. She’d try. But it was no good. She got no feeling off it, from my working. She had to work the thing herself, grind her own coffee” (202). Such mechanical pleasure, for Lawrence, is one of the great ills of modernity. Strikingly and repeatedly in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence focuses on orgasm itself as the locus of spiritual and sexual dysfunction. Just as Cipriano demands that Kate alter her means of attaining ecstasy, the sex scenes in Lady Chatterley’s Lover present Connie and the reader with a sequence of orgasmic instruction.

The first two times Mellors and Connie have sex, it is unremarkable. Like the woman who rode away, Connie is passive, “in a sort of sleep, in a sort of dream”; Mellors enters her and “She lay still, in a kind of sleep, always in a kind of sleep. The activity, the orgasm was his, all his” (116). Connie does not struggle to achieve her own orgasm, but she is not open to Mellors either, so she is unsatisfied. After he comes, she lies beside the “panting” man debating her predicament: “Her tormented modern woman’s brain still had no rest. Was it real?—And she knew, if she gave herself to the man, it was real. But if she kept herself for herself, it was nothing” (117). The next time she is with Mellors, she is drawn out of this “sex in the head.” “Her will had left her. A strange weight was on her limbs. She was giving way. She was giving up” (133). This surrender results in their simultaneous orgasms (“Then as he began to move in the sudden helpless orgasm, there awoke in her new strange thrills rippling inside her, rippling, rippling, like a flapping overlapping of soft flames” [133]) and Connie’s palpitating release: