“I know it is an election year for you, and a hard time for a decision. But I would like some idea of your strategic conception, whether we can get some heads of agreement that could give us some breathing space—by, first, getting an interim agreement…. Mr. Ambassador, you are in an odd period of tranquility. You have made your own assessment, but the reason for the absence of pressure on you now is because I have not permitted anyone to move. I have told Rabin—you have to be prepared.”

—Henry Kissinger to Ambassador Dinitz1

With the start of the secret discussions between Kissinger and Ismail, Sadat felt that a framework for discussion, aiming toward a peace agreement with Israel, had been created. In Sadat’s view, the military alternative would give momentum toward negotiations if Kissinger and Ismail failed to initiate them. Although Sadat had inaugurated the political channel, progress depended on Kissinger—specifically, his ability to influence Israel. On the other hand, Egypt conducted its military activities independently and unconditionally, directed by the army chiefs with the assistance of Sadat, who intended to induce the Soviet Union to open its arms depots to the Egyptian army; to recruit the aid of additional Arab states, particularly Libya; to persuade the Saudis to activate the oil weapon when the time came; and of course, to coordinate the combined attack with the president of Syria, Hafez al-Assad.

The information accessible to the Israeli intelligence organizations about Egypt’s inclinations was limited to activity in the military channel. Their intelligence sources, including the “superspy” Ashraf Marwan, were able to gain information on military preparations only, while other sources who could have supplied the full political information Meir and Dayan required for a general assessment of the situation chose not to do so. Nor did they update Israeli intelligence on the schedule for progress in the political channel, which Sadat had defined and Ismail had clarified to Kissinger: to reach agreement on principles between Egypt and the United States on full peace between Egypt and Israel by the end of spring and, by autumn, to achieve partial implementation and parallel, direct negotiations with Israel on the details of a comprehensive agreement that would be confirmed by the Israeli public in the October elections. This implied ultimatum, which in fact ended when the Yom Kippur War broke out, was completely concealed from the national intelligence appraisal team in Israel but was well known and obvious to Meir and Dayan. They were the only ones among Israeli decision-makers who knew Sadat’s deadline for reaching an agreement—September 1973. But Dayan and Meir did not realize the significance of that date for Sadat and for the Egyptians—three years since his appointment as president of Egypt and about a month before the Israeli elections. After three years of disillusionment with the reaction to his peace-seeking intentions and continuing delays in beginning negotiations, Sadat was determined to set a political process in motion, tying Egypt’s fate to the support of the United States and returning Sinai to Egyptian sovereignty. He viewed the elections in Israel as a test of the sincerity of Israel’s intentions.

In the summer of 1973, Sadat understood that only the military alternative was left to him in order to bring about negotiations.

Discussions completed, Kissinger began to organize his advisory staff to prepare for expeditious action that would include the Middle East. They expected developments that even the energetic national security advisor would have difficulty managing. As James Reston put it, “All Kissinger needs in this situation is for somebody to invent the 48-hour day.”2 Until such an inventor was found, Kissinger intended to go “off for a couple of weeks to rest and to put his mind to the new tasks the president [had] given him.”3 However, even before leaving for vacation, he had hurried to formulate his plan, which was intended to advance Sadat’s initiative without involving Israel yet. The plan included a schedule of stages:

In this spirit, Kissinger wrote to Ismail on March 9, 1973, that he was making an increased effort to understand the Israeli position in order to formulate an agreement on principles according to the outline Ismail had presented.5 Kissinger received reinforcement for this approach in a report from Eugene Trone, an American intermediary between Kissinger and Ismail who had spoken with Ismail at dinner on February 26 and at the airport on February 27, as Ismail was leaving the United States. Trone’s report included the following:

The key to a compromise, Mr. Ismail said at one point, is the principle of Egyptian sovereignty in Sinai. [He appeared to be studiously avoiding the use of the word territory.] Sovereignty, he said, is solid enough for them to defend to their own people, yet flexible enough to accommodate practical arrangements that may be necessary.6

Rabin was completing his term as Israeli ambassador to the United States and was due to fly back to Israel on Saturday evening, March 10. The day before, he arrived at the White House to take his leave of Kissinger, who complimented him: “You are one of the few people I will genuinely miss. I don’t say this just to be polite.” Rabin, embarrassed at the praise, turned the conversation back to political matters: “If you ask me what I worry about, it is the preparation for the summit.”

“Let me share my thoughts with you,” said Kissinger, but before continuing, he made sure that Rabin understood that the situation required a political process, even asking, “Does she [Meir] understand it?” Rabin confirmed that the prime minister did. “I have briefed you twice,” Kissinger reminded him, and let him look at two pages that one of Ismail’s escorts had prepared during the visit to the United States, in which he had summarized Ismail’s feelings and thoughts. Rabin was impressed by the significant points of the report and communicated this to the prime minister: “The visitor [Ismail] spoke a lot about the new formula which constituted the central aspect of his discussions with Robert [Nixon] and Shaul [Kissinger], sovereignty in return for security. The visitor reflected a great deal on the possibilities implicit in this formula.”

After Rabin had read the document, Kissinger informed him of the action plan he had formulated. It was clear that Rabin understood the importance of his last mission as ambassador. He would be required not only to transmit the details of the plan to Meir but also, and primarily, to report on Kissinger’s desire to implement it. Rabin knew that Meir would not rush to accept the information he would present to her, and that he could expect a difficult discussion. He protested to Kissinger, “To come out publicly with principles, say July or August, will be very unpleasant to the prime minister. That is two or three months before our election.” (Rabin was referring to the appointed time for publicizing the commitment of the United States to Egypt and recognizing its sovereignty over Sinai, according to Kissinger’s plan.) When Kissinger wanted to end discussion of a subject to which his interlocutor objected, he would customarily present the “president’s position.” This time, he answered the argument about Israeli elections by saying that the president was not influenced by elections in Israel; what interested Nixon was that he, Kissinger, should bring about a solution to the conflict in the Middle East.

This is how Rabin explained Kissinger’s plan to Meir:

Shaul [Kissinger] views the Egyptian readiness, still hesitant, to move from a demand to evacuate territory to a demand to recognize Egyptian sovereignty over Egyptian territory as a significantly important change. Moreover, Shaul sees a possibility to respond to Israeli security needs during the period between signing an agreement between the two sides which will create a state of peace, and the ultimate achievement of normalization between the two states by leaving Israeli military forces at critical points in Sinai, but without harming the principle of Egyptian sovereignty over them. In fact, Shaul foresees the creation of three security areas in Sinai at the stage following the peace agreement: one area which Egyptian forces will control, principally the canal sector; a second area in which Israeli forces will be stationed; and a third area, including most of Sinai, which will be a demilitarized zone serving to separate the two sides. The stage between achieving a peace agreement up to full normalization could be long-lasting and might continue for many years. Of course, Egyptian sovereignty will remain in effect for all of Sinai, except perhaps for adjustments to the former international border. Shaul emphasized that, by this, he means minor changes that are certainly not on the order of what we have presented to him.7

Kissinger added an additional and not unimportant element in an attempt to convince Meir: “Shaul repeated that he believed that, with Egypt’s agreement, the proposed Egyptian settlement could be separated from any attention to Jordan and/or Syria.”

Kissinger summarized all of his expectations for concessions from the prime minister in the question he repeated to Rabin: “Would [Israel] be willing to deviate from [its] position of demanding significant border changes in comparison to the international border?”

Rabin promised to return with a prompt answer. The discussion ended on Friday evening at 18:40 Washington time (early Saturday morning in Israel). Rabin waited for a few hours and then called Meir for a telephone discussion. The discussion was long and difficult as Rabin tried, without success, to convince her to accept Kissinger’s plan.

On Saturday, at 15:15 Washington time, Rabin telephoned the White House to inform Kissinger of Meir’s negative response to his question. The contents of the conversation, as written, may testify somewhat to Rabin’s discussion with Meir.

Rabin: I’ve tried my best to convey … two hours.

Kissinger: One way or the other, this issue is going to get surfaced.

Rabin: Yeah.

Kissinger: Your practical choice is only in what channel.

Rabin: Yeah.

Kissinger: And under whose auspices.

Rabin: I explained that.

Kissinger: And that they should just continue to keep that in mind.

Rabin: I believe that I have tried my best to explain it.8

Rabin reported that Kissinger had warned him during the previous day’s meeting about what would happen if Israel did not cooperate with his plan. In Rabin’s version, Kissinger told him that the president was ready to approve the continued supply of planes to Israel because Kissinger had led him to believe that there would be movement in the political process, but “he would find himself in trouble when, in another month or in three months, he would have to come to Robert and to tell him that he had no solution. He believed that the entire matter would be transferred to the State Department, and then the basis of discussion with the Soviet Union and with Egypt would rest upon the Gromyko Plan.”9

As it later became clear, these warnings did not particularly impress the political echelon in Israel. Mordechai Gazit, who replaced Dinitz as director of the Prime Minister’s Office, wrote to Dinitz, who replaced Rabin as ambassador:

Thanks to the telephone discussion he had with Rabin in accord with the instructions of the prime minister, Shaul [Kissinger] well understands the reservations which became apparent during the first visit. We assume that Shaul will hear Hafez [Ismail]’s reply, respond to it, and throw out some ideas, but that he will emphasize that all of these are ideas for initial investigation and examination and do not obligate the United States, and certainly not Israel. Indeed, Shaul told us that he would not confront us with surprises.10

At the end of the discussion, Kissinger understood that there was no further point to this dialogue and moved on to practical matters. He said that he would wait to see what would happen at his meeting with Ismail in April and explained that Israel’s decision could wait until the last minute, when Israel would be forced to decide. These proceedings would demand coordination, trust, understanding, and mutual alertness based on close personal relations between Kissinger and whoever would be his contact on the Israeli side. Already, in the course of the previous day’s meeting, Kissinger had expressed the fear that Dinitz would not meet these conditions and that Israel would create a different system of contacts in Washington that would bypass the national security advisor. Rabin calmed him, saying: “We have no reason to destroy the only channel of discussion on which we can depend.” Kissinger was not calmed: “Yes, but Dayan, for example, thinks that he could work with anyone.”

Kissinger continued to feel troubled on this point and expressed the hope that Rabin would continue to be involved in decision-making. He asked whether a request from the United States would help to achieve this. During his term as ambassador, Rabin had not hidden his doubts, when he had them, regarding Meir’s political conduct and was aware of her hostility toward anyone who did not agree with her opinions. Meir had also been obliged to hear much praise of Rabin during his time in Washington. Moreover, the success of her visit was in no small measure due to his preparation and his ties in the US government, many of whom admired him greatly. These factors only increased her hostility, which she had difficulty hiding. Ha’aretz reported that “in a briefing to the Israeli press, when she was asked to respond to Nixon’s praise of Rabin, she retorted sourly, ‘That’s one perspective.’”11

Thus, Rabin rejected Kissinger’s generous offer to request Rabin’s continued involvement in negotiations: “Not at the beginning.” Kissinger understood Rabin’s distress and responded with a quote by Admiral Ernest J. King, a World War II navy commander who, when asked for advice after his retirement, responded: “When they get into trouble, they call for the sons of bitches.”

Kissinger did not hide his anger at Meir’s negative reply, but his conduct after her refusal indicates that he agreed to make an effort to delay the political process until after the Israeli elections, in the hope that Meir’s opposition to his initiative would then weaken. The next two tasks Kissinger set for himself regarding the Middle East were, first, to delay the meeting with Ismail set for April 10, and second, to postpone Soviet pressure to discuss developments in the Middle East, at least until the summit meeting in June. This pressure stemmed from the Soviet Union’s desire to prevent the military conflict Sadat was threatening. The Soviet Union, which had cooperated in providing Egypt with military equipment, knew that this threat was real.

Kissinger waited until the last moment to postpone the meeting with Ismail. At this stage, he needed this channel so that he could tell the Soviets, “The Egyptians don’t want you in it. As long as we are talking to the Egyptians, we can’t get into detailed negotiations with you without total confusion.”12

“We have a great friend in the White House,” announced Golda Meir before her return to Israel on March 11. The newspaper headlines of that day had reported that, according to opinion polls, her party would receive fifty-four seats in the Knesset, that Qaddafi had had a nervous breakdown, and that Meir had changed her mind about retiring from politics before the coming elections.13

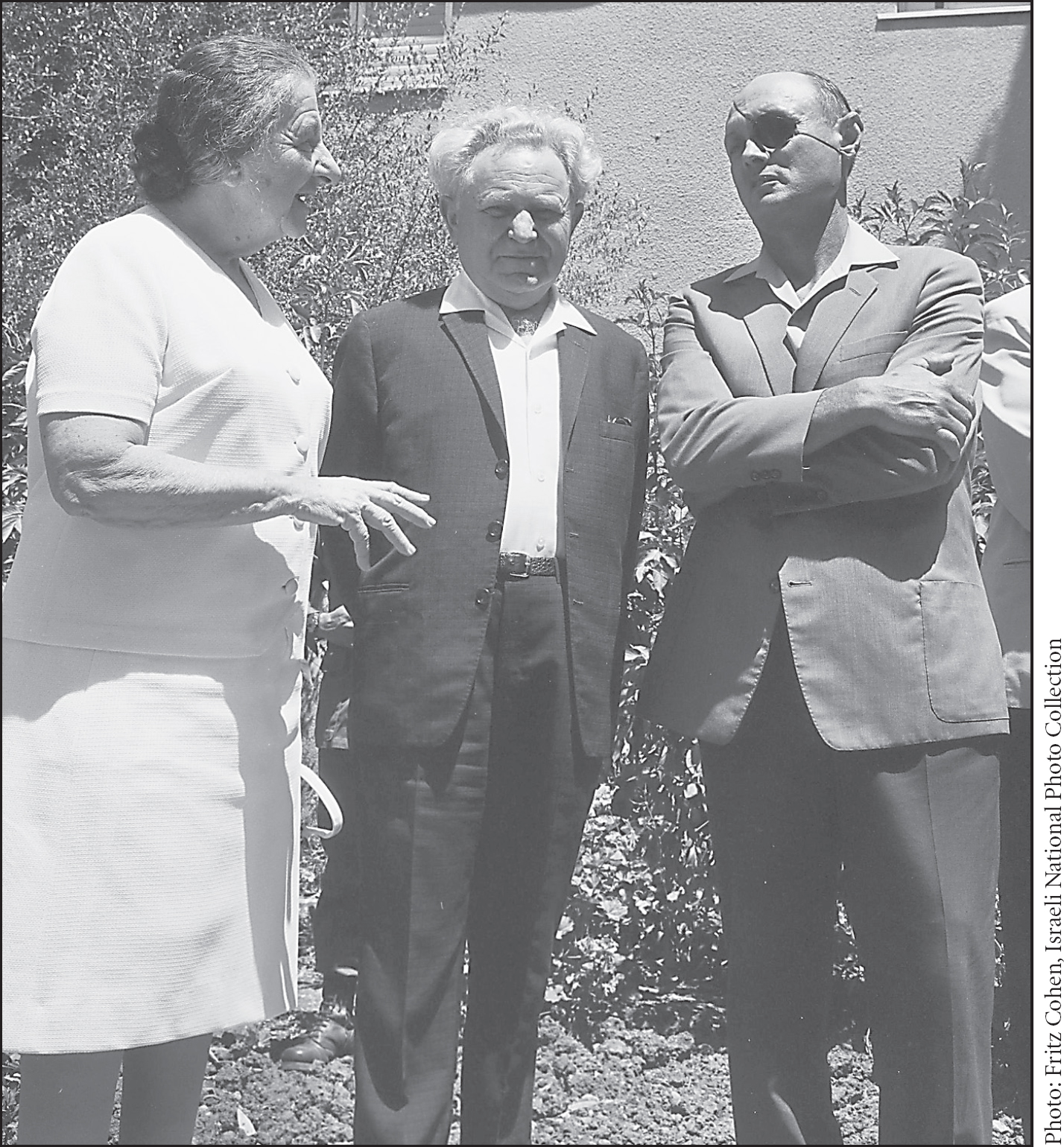

Golda Meir, Yisrael Galili, and Moshe Dayan at Beit Hanassi, May 11, 1970

While still in the United States, she had written to Yigal Allon, who had temporarily replaced her in the government while she was away: “A full report of our discussion with the president is being sent with Zvika [Zamir] who will arrive in Israel on Tuesday. The prime minister wishes that the report be shown to you, [Minister without Portfolio Yisrael] Galili, and Dayan only.”14 Allon’s report to the government regarding the prime minister’s discussion in the United States was very general and was transmitted to the government ministers before Zamir’s report reached him.

Upon her return on March 13, the prime minister invited a small group of ministers for a more detailed report.15 She opened her report with a request:

I would like to make a request from our friends that the information I supply here about the discussion, particularly with the president, if it is leaked, will make it easily possible to achieve one objective—that they will not talk to us at all. I know that Israelis are willing to climb the barricades for anything, but do not leak this. Not at all.

She updated the ministers on the two objectives of her visit. The first was “to check whether there had been any change in the United States’ position, primarily considering the statements that ‘this is Middle East month’ by members of the American government and with the assumption that after Vietnam they will turn their attention to our area as well.” The second was “to clarify actual matters regarding the supply of planes.” Most of the comments and questions by the ministers related to the second subject. Regarding the political matter, she added her determination to what they had already read in the newspapers: “There is nothing in what Hussein and Ismail brought up that would provide a basis for a demand that we or the Americans change our positions.”16 This determination did not match Rabin’s impressions, which he did not make known to the ministers:

Kissinger did not try to hide the fact that Ismail’s statements pleased him and even I could not deny that the senior Egyptian representative had some interesting things to say.17

The return of full Egyptian sovereignty over Sinai could be combined with the possibility of finding a compromise between full Egyptian sovereignty and the security demands of Israel.18

Rabin also testified that Kissinger told him, “I do not hide my opinion that your [Israel’s] territorial demands cannot be achieved in the framework of a political settlement.”19

Regarding the practical conclusions of the visit, Meir’s report reflected reality: “It is clear that [the Americans] will try to be active and to move the sides forward, but there is no demand directed at us. Perhaps Ismail will return to America.” She added:

I was very concerned about what would happen at the summit with Brezhnev, what would happen with Egypt, what the United States’ position would be, and I received a renewed promise that nothing will be done behind our backs. We will know and they will talk to us without previously committing themselves to the Russians or to the Egyptians. That has been promised.20

Yisrael Galili and Shimon Peres asked to confirm this. Meir repeated and emphasized, “There will be no agreement between them and the Russians at our expense without them speaking to us.” There will be no settlement “without our agreement, without our knowledge, behind our backs.”

If there were ministers in Golda Meir’s “kitchen cabinet” who did not agree with this policy, they did not express it. One minister who viewed the political status quo as dangerous was Yigal Allon, who acted without the knowledge of the prime minister in order to remove the danger.21 As noted, in November 1972, he had already caused a commotion in the Israeli government and the Soviet Union by announcing that negotiations with Egypt should be opened in two parallel channels, one aimed at a partial settlement and the other at a comprehensive settlement. Now, on March 1, 1973, even before receiving Zamir’s report about the discussions in Washington—and, actually, even before the meeting between Nixon and Meir—Allon met in Israel with an American representative, expressed his reservations about Israeli policy, and recommended that the Americans take the initiative and appoint an American emissary to advance developments in the Middle East. It appears that he was implying that Kissinger should take on this role. He explained that if such a step was not taken promptly, it would be even harder to achieve peace, because Israel would start to relate to Sinai as part of the Holy Land.

According to his testimony to the Davis Institute, Allon’s position on Sinai was a minimal one regarding areas which Israel would demand to hold onto. He believed that Israel’s security needs would necessitate control of four points:

I schematically visualized four arcs which would be essential: … one arc would include the area of Pithat Rafiah…. The second … embracing Auja, el-Hafir, Kuntilla, el-Kysima … in the area facing Nitzana…. The third arc broadening our hold on Eilat…. And the fourth, Sharm el-Sheikh.

Allon did not see the need for territorial contiguity between these areas: “If this is in the framework of peace, there would be no difficulty about crossing, even without another corridor, and if there is no alternative, the sea may also serve for transportation.”22

The Allon proposal matched Rabin’s position and perhaps had even been coordinated with him. The personal closeness of the two graduates of Kadoorie Agricultural School, which had begun in the Palmach (an underground organization that operated under the auspices of the Jewish settlement organization before the establishment of the State of Israel) and continued through the years, found contemporary expression in similar political positions and cooperation.23 More important—Allon’s general position regarding political progress had a common basis with Sadat’s initiative and with Kissinger’s plan to implement this initiative, which Rabin had heard at their meeting on March 9. However, Allon’s opinions had no impact. The political status of his eternal rival, Dayan, was much higher.

In March, the election atmosphere began to be felt and Israel was, for the most part, busy with its own concerns. Decision-makers considered Sadat’s moves annoyances to be eliminated. They attempted to rid themselves of this political annoyance through Kissinger and Nixon. Their response to the military annoyance—Sadat’s threat of war—was to increase Israel’s acquisition of military equipment, schedule additional training, and expand deterrence.

The Meir government had begun its life as a national unity government, with the War of Attrition at the Suez Canal just beginning. Toward summer 1970, the war was at its height and Israel’s air superiority, which was expressed on a daily basis in attacks on Egypt, led the Soviets to organize and install a system of ground-to-air missiles at the canal front. The Israeli air force had difficulty dealing with this missile system: attack planes were hit, pilots were killed, and others were taken prisoner. After more than 700 Israeli soldiers had been killed (from the outbreak of the war) and thousands more injured, Israelis awaited an accelerated end to the canal war.

Against this backdrop, the United States advanced what is usually called the Rogers Plan: a proposal for a ceasefire between Israel and Egypt and a renewal of talks between Israel, Egypt, and Jordan for a peace agreement on the basis of UN Security Council Resolution 242. The American initiative included a concealed threat to Israel that if it did not reply positively to the proposal, the United States would stop supplying it with planes. Egypt responded positively to the American proposal; in Israel, as well, a large majority of the political system was inclined to lend support to the ceasefire initiative.24 Minister Menachem Begin opposed the initiative and led his political camp to dismantle the national unity government.25

The Meir government, which responded positively to the United States’ proposal on August 7, 1970, ending the War of Attrition, now had to deal with governmental opposition to the political process. In March 1973, half a year before the elections were to take place, this situation greatly affected political discourse in Israel. Considering the political circumstances in 1973, not only did Meir and Dayan refuse to enter a political process, they even chose not to report to the government regarding the possibility of such a process which Sadat’s initiative had opened up to Israel. Any internal debate within the government might have been leaked to the opposition and provided an opportunity to attack.26

In addition to the conflict between Israeli political blocs, there were internal conflicts in the ruling Labor Party on three levels: first, between camps in the party; second, intergenerational conflict around the issue of who would succeed Meir if and when she retired (that is, would leadership pass on to the younger generation—Moshe Dayan, the defense minister; Yigal Allon, the deputy prime minister; Abba Eban, the foreign minister—or to more mature leadership such as Pinhas Sapir, the finance minister); third, personal conflicts among the candidates to succeed Meir.27 In all of these conflicts, Defense Minister Dayan played a central role. Dayan’s power stemmed from the strength and the security of his personal status among the general public. Dayan’s status to a great extent led him to be uncritical of his own conduct; it moderated public criticism of him as well. His threat, open or implicit, that he would act independently in the political system if his opinions were not accepted carried great weight in the considerations of the Labor Party, in the comments of its leaders, and in the determination of its party platform for the elections.

The question being asked in those days was whether the Labor Party, most of whose members were willing to make wide-ranging concessions for peace agreements, would dare to come out with a “dovish” platform, considering that public opinion was toughening and seemed to be moving toward a position of “not even one inch.”28 In the past, Dayan had submissively and secretly accepted the prime minister’s opposition to his proposal to withdraw Israeli forces from the Suez Canal and allow it to be opened. In March 1973, against the backdrop of his party’s internal organization for the elections, Dayan became more extreme in his public remarks, demanding that the Labor Party define its settlement map and thus express its position regarding the permanent borders of Israel. In actuality, he forced his opinion on the party, saying, “I prefer the existing situation over a complete or almost complete withdrawal to the previous lines.” He added, “By the end of the present decade we will be able to overcome the Arabs if they try to renew the war.”29

Meir at first opposed Dayan’s moves to anchor a map of the future to binding decisions. At a meeting of the Labor Party Secretariat, she stated that the results of her visit to the United States had convinced her that there was no need at present to decide the dispute about the future of the territories vis-à-vis public opinion. She maintained that it was unnecessary to be drawn into a “Jewish war.” In this manner, she redirected the internal struggle in the Labor Party between Dayan and his opponents, most prominently Allon, Sapir, Eban, and Lyova Eliav. But Dayan’s position overcame the opposition and Minister Galili was given the task of writing a document that bore his own name but included Dayan’s demands.30

Following the meeting between Kissinger and Ismail, during which they agreed to meet again on April 10 to formulate the agreement in principle between the United States and Egypt by May, Sadat continued to operate in two channels, the political and the military. He had to strengthen his status in public opinion to be convincing in his preparation for a military move and, no less important, to use these preparations as an argument to consolidate national forces and freeze activity against the government.

Egypt was not (and still is not) an easy state to lead. Poverty is widespread and the high rate of natural population increase intensifies it. A growing number of students and educated people have difficulty finding suitable employment for their level of education, but know how to demand political freedoms and find outlets for their frustrations. In addition, Sadat had to deal the Muslim Brotherhood movement, a focal point of opposition. He suppressed mass student demonstrations and eliminated a political conspiracy to remove him from power.31 More than anything, Egypt’s stinging defeat by Israel in the Six-Day War and the loss of Sinai in that war hovered in the atmosphere.

On February 27, when Ismail was still in the United States, Sadat had assembled an unusual gathering in Cairo. He invited about 150 senior media figures and opinion-makers in Egypt to a three-hour meeting. Official reports were short and uninformative. At the meeting, Sadat provided a summary of his future activity for 1973. The list of those present and the wording of the report indicate that it was meant for internal consumption.32 After he had explained to his listeners that the choice was between capitulation and battle, he elaborated about the military track: “I am not the right man for capitulation. The decision therefore has been made and it is something which is unavoidable…. We will defeat the Zionists in a third war.” However, Sadat, who was disappointed that Kissinger had not presented the United States’ position on his initiative to Ismail, also spoke of the political track:

During his discussion with Ismail, President Nixon hinted that he wanted to take the initiative in the direction of peace. We will wait for a time to see what results his statement will bring. I do not wish to predict or to draw conclusions. What interests us is our approach to the battle, and this approach has already been implemented—anyone who does not believe that will be able to see it in the near future.33

He summarized his speech by presenting two levels of action:

Simultaneous to this meeting, Sadat sent the Egyptian minister of war, General Ahmad Ismail Ali, to Moscow for a visit that received wide media coverage. “Ali’s job now was to keep the military out of politics,” wrote Kissinger to Nixon, updating him on the visit.35 His explanation was anchored in reality: the military leaders were deeply involved in preparations for battle and were completely excluded from political developments.36

Nixon received a report of Ali’s visit to Moscow from the Soviets as well.37 The Soviets understood the significance of Egypt’s and Syria’s requests for equipment well. Brezhnev again warned Nixon that in the absence of progress, Egypt was preparing itself for another round of fighting in an attempt to maintain its status in the Middle East. The Soviets were cooperating with the military preparations, but at the same time, feared their implementation.38

On March 26, Sadat gave a speech in Cairo that repeated publicly what he had said a month earlier in the closed forum of media representatives. This time, however, he added a very significant practical step: he changed the composition of his government and chose himself to stand at its head.39

After a detailed examination of the speech’s content, Kissinger interpreted Sadat’s words to President Nixon as statements made to satisfy internal needs with regard to internal agitation against Sadat, which had reached its peak in January, as well as a reaction to criticism in the Arab world for his contacts with the United States while the US continued to supply arms to Israel.40 Regarding the double meaning in Sadat’s words, Kissinger summarized:

Sadat has been giving considerable thought to what Ismail was told in Washington. He remains skeptical, but appears realistic about what he can expect from the US. Finally, he seems to be considering the idea that the concept of restoring Egyptian sovereignty might allow for some arrangements that address Israel’s security concerns. It would seem premature to judge that he has rejected the possibilities inherent in this concept.41

“I will be talking intensively with the Israelis in an effort to develop an understanding of their position as it might relate to possible heads of agreement in the plan you outlined,” Kissinger updated Ismail. It was March 9. Kissinger had met with Rabin earlier that day and had not as yet received Meir’s negative reply to his proposal.42 In his letter to Ismail, Kissinger also referred to the murder of the American diplomats in Khartoum at the beginning of the month and protested against the use of terror for political purposes. Three weeks later, Kissinger would make use of this murder as a pretext to postpone his meeting with Ismail.

In his reply of March 20, Ismail protested Kissinger’s use of the special communications channel between them for issues unrelated to political negotiations.43 Regarding the political process itself, he wrote, “We have taken note that Dr. Kissinger has started talks with the Israelis and that he intends to conduct further talks with them.” At the same time, he added that he expected to exchange ideas that would enable quick progress at the coming meeting. Ismail objected to the public revelation that the United States had decided to continue supplying Israel with equipment; he pointed out that this course of action had, in the past, led to the failure of talks. In addition, he emphasized that Egypt understood that it was again expected to make concessions, with the assumption that these would perhaps lead Israel to cooperate in the political process.

Having accepted Israel’s opposition to advancing the process, and with the Israeli ambassador (who could offer him direct contact with Meir) absent from Washington, Kissinger determined to delay the negotiations and to use the communications channel with Ismail as a means of lessening Soviet pressure to make progress toward a settlement and preventing Egyptian military moves for as long as discussions were going on.

The continuation of the communications between Kissinger and Ismail must be examined on the basis of what Kissinger told Ambassador Dinitz at their first meeting:

Regarding Egypt, as we know, an additional meeting with Hafez Ismail was set to take place on April 10. In the interim, there was Khartoum, and Shaul [Kissinger] announced to the Egyptians that, considering what had happened, it was impossible to continue developments as planned…. In any case, the ball is now in Egypt’s court. Shaul is certain that they will request another meeting, and he will agree, but in the meanwhile, another few weeks will go by and the summit [between Brezhnev and Nixon, which was planned for the middle of June] will be approaching and so it seems that we will get through the summer without any unnecessary pressures. However, he thinks that the moment will come when we must relate to the practical problems and thus we must prepare…. He will not set any practical discussion on issues involving us without full coordination with us and agreement on our part. He does not at the moment expect any quick political progress but, in his opinion, we [Israel] must be ready for the possibility of political negotiations if and when they are renewed. He, on his part, of course, will continue with his foot-dragging and will not speed up the pace of developments.44

From Kissinger’s answer to Ismail on March 22, it becomes clear that, indeed, he transferred the ball into Ismail’s court.45 Kissinger wrote that he was still waiting to receive a detailed reply from Egypt regarding the issues which had been brought up at the first meeting, as well as the suggestion of a suitable date for the next meeting. After Sadat’s speech on March 26, Kissinger saw fit to send an additional letter.46 Alongside his report to the prime minister, Dinitz added, “Again Shaul is the initiator.” It appears that Kissinger understood that the Egyptians were suspicious of his intentions and wanted to regain their trust by writing a placatory letter.

Ismail’s reply arrived about a week later, on April 7.47 Even though, at that stage, the preparations for war had reached an advanced point, the letter indicates an effort to return the channel to practical matters. Ismail ended with a request that Kissinger propose a date for a meeting between them that month, April, in a neutral country. In the meantime, Sadat had decided to recruit the Saudis to his effort to urge Kissinger on. He informed them of the secret channel that had been initiated. They immediately took action and warned the United States of the possibility of a renewal of fire between Egypt and Israel.48

Kissinger responded to Ismail’s letter on April 11.49 His reply criticized Egypt for revealing the secret channel’s existence to the Saudis and threatened to cease his involvement in it if the rules of secrecy were not maintained as had been determined. But he also gave a detailed reply that included the United States’ desire to conclude an agreement on principles (Kissinger used Ismail’s term, “heads of agreement”) based on UN Security Council Resolution 242. He also suggested a date for a meeting—May 9, a postponement of a month from the original date which had been set.

Dinitz reported on this letter to Meir’s office, which replied that “this matter is not clear to us.” They knew that Kissinger had postponed the planned meeting using the excuse of the events in Khartoum. “Have the Egyptians applied to him since then?”

“The application is new,” affirmed Dinitz.50

By the end of March, about a month after the meetings between Ismail and Kissinger, Sadat understood that the meeting set for April 10 would not take place and the weight of the military option increased. The message was transmitted by the senior editor of Newsweek, Arnaud de Borchgrave, who had been waiting in Cairo for three weeks to conduct an interview with Sadat.51 The headline of the interview that followed read: “The Battle Is Now Inevitable.” In the interview, Sadat expressed complete disappointment with the reaction of the United States to his initiative. “If Hafez [Ismail] had conducted discussions with Golda Meir, the results would have been less ridiculous,” said Sadat, referring to the United States’ mediation, and added, “Yes, I want a final peace agreement with Israel, but there was no response from the US or Israel except to supply Israel with more Phantoms.”

“The time has come for a shock,” Sadat said to the reporter, who added his own impression that the Egyptian president “did not close the door on a diplomatic settlement but insisted that unless there was peace based on justice, there will be nightmares, and everybody will lose.” The president repeated his distinction between an agreement on Sharm el-Sheikh, which would grant Israel the security it desired, and returning Egyptian sovereignty to Sinai. “We must remind the world that Israel still occupies our country and we are prepared to die by the thousands for national liberation,” he said.

About a week after this interview, the Newsweek reporter arrived in Israel and asked to meet with the prime minister to update her on what he had heard from Sadat that was not meant for publication. He was politely refused.52 Immediately after Newsweek published the interview, Sadat left for a two-day visit to Libyan president Moammar Qaddafi, his neighbor in Tripoli. Qaddafi had prevented the transfer to Egypt of Mirage planes and parts purchased from France, claiming that Sadat was not serious in his intention to do battle with Israel. Sadat’s visit was meant to convince Qaddafi of the seriousness of his intentions.53 During the visit, an official source in Cairo reported that Egypt would not initiate a wide-scale action against Israel and that it would continue to conduct a dialogue with the United States despite the narrowing possibilities for a settlement.54

Upon his return from Libya, Sadat assembled his government, requested approval for a military action against Israel, and received it by a majority. Sadat told the government he now headed that there was no other way except for battle and that “even though the United States has the power to lead to a solution of the dispute, it does not want to.”55 He added, “This stage of the general conflict means taking up arms to defend our rights and to return our land, and it requires general mobilization for the campaign by everyone in our homeland.” The same week, Ha’aretz published reports about his visits to Egyptian army units at the canal. However, Sadat simultaneously took a very meaningful step in order to strengthen Egypt’s link with the United States when he appointed Hafez Ismail, his partner in the secret political moves, as director of the Prime Minister’s Office, in addition to his services as national security advisor.

The headline of the article by Zeev Schiff, military correspondent for Ha’aretz, referred to Sadat’s actions: “Sadat Threatens: Israel Has the Ability to Establish Facts Across the Canal.” The article continued: “The reactions of authorities [in Israel] can be summarized as follows: There is no reason to get excited. These declarations are no different than previous ones and they are meant, first and foremost, for internal consumption and to put pressure on the superpowers.” In contrast, the correspondent of the Sunday Times reported from Cairo that “Sadat will gamble on a limited attack to break the ice in the Middle East.”56

At the height of the increasing Egyptian threats, one of the most complex and successful Israeli commando raids reached its practical stage. Agents of the Mossad began preparations for an operation in Beirut, Lebanon, that later became known as Operation Spring of Youth.57 During the early hours of the morning of April 10, after landing from the sea on the Beirut coast, the Israelis attacked a number of points in the heart of the city.

In an exclusive neighborhood in the northwest of the city, Ramlat al-Baida, three PLO leaders were surprised and killed: Muhammad Abu Yusuf Najjar, a leader of the Black September Organization (BSO) and one of the planners of the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics; Kamal Adwan, the BSO’s head of special operations; and Kamal Nasser, Arafat’s spokesman. Sayeret Matkal, an elite special operations force, was entrusted with carrying out the mission, while the commander of the force, Ehud Brog (Barak), and two of his fighters, Amiram Levine and Loni Rafaeli, participated dressed as women. Another force of paratroopers, led by Amnon Lipkin, blew up the building where the commander of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) was staying. In addition, two other targets in Beirut and another north of Sidon were attacked by the paratroopers and Flotilla 13, the navy commando unit. Dozens of terrorists (in the Israeli view, or combatants, as viewed by the Palestinians), from a number of organizations, were killed. Intelligence material taken from the terrorists’ apartments and at other points enabled the arrest of terrorists from areas under Israel control. Hagi Ma’ayan and Avida Shor, members of the elite paratrooper unit who had participated in the force that blew up the PFLP headquarters, were killed in the daring operation in the heart of Beirut. The Egyptians reacted to the operation by stating that its aim had been “to implant the feeling in the hearts of the Arabs that Israel was the region’s ruling power.”58

Indeed, the sense of power was intoxicating for the Israeli general public and for its leaders. The day the commanders and the force returned from Beirut to the port of Haifa, Defense Minister Dayan proclaimed from the peak of Masada, “We will establish a new Israel, with wide borders, not like in 1948.”59 At the beginning of April, at an assembly of paratroopers in Jerusalem, Dayan had stated, “It seems to me that we are at the opening of a peak phase in the ‘return to Zion.’” At Masada he went a step further in his appraisal: “At this time we are blessed with conditions which I doubt that our nation has ever seen in the past, certainly not in the ‘return to Zion’ period.”60

Six years later, on April 16, 1979 (twenty days after signing the peace treaty with Egypt), Dayan would proclaim:

Perhaps in the Golan, as well, Israel will face the same question which it faced regarding Sharm el-Sheikh: that is, whether to keep Sharm or whether to prefer peace without Sharm. Perhaps such a question will arise regarding the Golan and we will have to decide what Israel prefers—the Golan Heights without peace with Syria, or peace with Syria without the settlements in the Golan Heights.

How far this statement is from the speech he made at Masada about the new Israel and its wider borders!61

Apart from the practical difficulties between Egypt and the United States, the secret channel also suffered from other disturbances. At the beginning of April, with the publication of Sadat’s Newsweek interview and following the discussions with the Saudis, Joseph Greene, the principal officer of the United States Interests Section in Egypt, who was operating as a representative of the State Department, had discovered that there was a parallel channel of communication between the White House and Sadat via the CIA.62 “Hence I am perplexed about what to say to whom in the government of Egypt, and, for that matter, how to report and analyze for the US government what is or is not going on in Egypt,” he wrote to the State Department.63 Greene completed his scathing telegram with the question, “How I can perform that function when the government of Egypt clearly knows that I am unaware of both the form and content of a parallel channel through my own establishment?”

By prior agreement between the president and Kissinger, the secret channel between Kissinger and Sadat via Ismail had been kept hidden from Secretary of State Rogers and from the State Department. Now the president was forced to patch up the rift.64 At a joint meeting with Kissinger and Sisco, Nixon explained to the State Department representative his role in a double game—to create the appearance of an open channel and to enable Kissinger to conduct negotiations through a secret channel. “We all know the Israelis are just impossible,” said Nixon, explaining the use of these tactics. “We’re getting closer to their election, too, Mr. President,” Sisco said, trying to defend Israel. The president reacted: “Well, yeah, but they’re always close to an election. Then they’ll be closer to ours. See, that’s always the excuse they’ve taken.”65

Following the State Department clarification, and possibly as a result, Abba Eban, the Israeli foreign minister, also tried to deal with the matter. He turned to the American ambassador in Israel with a request to receive “additional and tangible clarifications” about these political developments, about which he too had known nothing. The request was passed on to the State Department, which transmitted it to Kissinger. Dinitz reported that Kissinger responded by telling him that such requests “endanger his [Kissinger’s] handling of the matter” and requesting that the prime minister “let the matter drop.”66

The prime minister promptly took care of the difficulty. Mordechai Gazit, the director-general of the Prime Minister’s Office, wrote a personal letter to Dinitz:

Dear Simcha,

A few comments for organizing communication: The prime minister is inclined to leave the distribution of Shaul’s [Kissinger’s] material as it has been…. The prime minister will talk to the foreign minister and explain the decision to him.67

However, from then on, Kissinger had to include the State Department in his communications with Ismail, and Sisco coordinated replies to Greene in Cairo and to the ambassador in Tel Aviv regarding the Middle East with Kissinger. In his book Years of Upheaval, Kissinger explained the limitations of his ability to maneuver as stemming from the exposure of the secret channel. However, there is no doubt that during this period, Kissinger was the only person deciding the foreign policy of the United States, even in matters of the Middle East. Although the Secretary of State submitted his letter of resignation only four months later, he was already on his way out in April. Kissinger acted to achieve this move and Israel was happy to assist.

If Kissinger did not already have enough problems in his difficulties with the State Department, he also had to deal with the wariness of Meir, who expressed doubt about the credibility of his updates regarding his contacts with Ismail. “Henry, the Israelis will give you a very hard time on that one,” Sisco said to Kissinger when they spoke on the telephone about the leaked details.68 Indeed, Meir expressed her suspicions harshly in her reaction to news of the continuing contacts between Ismail and Kissinger.

Kissinger’s and Dinitz’s awareness of Meir’s suspicions was already evident in their April 11 discussion in the White House, most of which was devoted to exchanging messages with Ismail. Part of the discussion took place privately. Forty minutes after it ended, Dinitz reported to Meir regarding, at least, everything related to the letter to Ismail. He wrote in a placating tone by telegram: “Shaul showed us the documents…. An additional meeting will take place between Shaul and Hafez in Europe around May 10. Shaul still must reply to Hafez’s last request and we will probably meet tomorrow for him to show me his answer.”69

Dinitz was meeting with Kissinger secretly. The need for an intermediary between the White House and the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem with regard to the secret channel made it necessary for Kissinger to summon Dinitz even before he had been sworn in as ambassador and before, as was accepted procedure, he had met with the secretary of state. Dinitz would arrive at the eastern entrance of the East Wing of the White House, which was used by maintenance and service people, not by diplomats and visitors; this side entrance led directly to the wings, far from the eyes of the media. He was accompanied to the Map Room by Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s assistant as head of the National Security Council, where they waited for Kissinger. This practice continued for several months, until Kissinger’s appointment as secretary of state in September 1973.70

The April 11 meeting was only the second working meeting of the two. The two men had not yet developed a personal relationship, and Kissinger was careful to be businesslike in his conversations. He told Dinitz what he had already emphasized to Rabin—his wishes, his plan, and his schedule for advancing the plan, on the basis of what he had heard from Ismail and in consideration of Israel’s difficulty in publicly discussing a comprehensive peace agreement before the elections. “I must draw your attention to the fact that it does not mean that this [postponement] can be done indefinitely. I have been stringing along the Russians for 18 months and the Egyptians for 10 months,” he informed Dinitz.71 He warned that if, during his next meeting with Ismail, there was no progress, “the Egyptians would open fire, even though it was clear to them that they could not achieve any advantage by doing it, and at the same time, they would focus on pressure using the oil issue.”72 They would take this step even if their military inferiority was clear to them.

He clarified that Israel must not err in thinking that, because of the Watergate affair, which was gaining momentum, the president would not be able to put pressure on Israel and warned that the United States was liable to pressure Israel to accept its political dictates even if there was no change in the Egyptian position, as Israel expected.

Kissinger saw fit to repeat his warnings again and again and, as a consequence, to request credit for his program:

I know it is an election year for you, and a hard time for a decision. But I would like some idea of your strategic conception, whether we can get some heads of agreement that could give us some breathing space—by, first, getting an interim agreement…. Mr. Ambassador, you are in an odd period of tranquility. You have made your own assessment, but the reason for the absence of pressure on you now is because I have not permitted anyone to move. I have told Rabin—you have to be prepared.73

Kissinger presented Dinitz with his evaluations, speaking as an advisor to Israel and as someone who was concerned about its interests. In retrospect, it ultimately became clear, of course, that Kissinger was right in his appraisals and in the need to act according to them. However, first and foremost, Kissinger was at this time acting in accord with American interests—as the United States could be the only superpower to lead to a breakthrough in the Middle East, thus avoiding a war that could renew Egypt’s dependence on the Soviet Union and return Soviet influence to the region. It also did not hurt that the line of action Kissinger had chosen suited the promotion of his personal status in the internal government power structure.

In his discussion with Dinitz, Kissinger was extremely focused and asked for Israel’s approach on three points: first, the Israeli idea of how to begin the political process; second, how Israel thought it should continue; and third, an interim solution that would break through the current deadlock. Kissinger, in a formulation Dinitz chose to transmit to the prime minister, “would ascribe great importance to receiving from us a number of general principles for his coming meeting with Hafez in May…. The only thing that he requests is that we give him ammunition in order to continue to delay the matter, as he has done up to now, both before the summit and afterward.”

On the next day, Dinitz returned to the White House so that Peter Rodman, Kissinger’s assistant, could, as promised, show him the letter Kissinger meant to send to Ismail.74 In accord with Meir’s directions, Dinitz asked Rodman to delay sending the letter so that Meir could transmit her comments. He followed the instructions he had received from the Prime Minister’s Office stating that “when Shaul [Kissinger] shows you the wording of his answer to Hafez, tell him that you want to transmit it to the prime minister, and for her eyes only prepare an outline of the intermediate reply so that she can make her comments on that basis.”75 Kissinger lost his patience and reacted angrily that it had been “an arrangement of a meeting, and that was all…. You must know that, following your request to enable the prime minister to make her comments, I ordered our intermediary in Cairo to delay the draft until this morning. It will just be lying there until then, but it cannot be delayed further.” The reason for the urgency in transmitting the reply testifies to the military tension Sadat had raised in order to press for political progress. Kissinger estimated to Dinitz that the chances of Sadat opening fire were fifty-fifty. He said that if Egypt began a military action, “we can say that we did everything we could and we will not be responsible if the ceasefire is breached or if it collapses.” Dinitz relayed this in a telephone conversation to the Prime Minister’s Office late that night.76 Gazit, who wrote down the contents of the conversation, added in the margin, “At one point in the conversation, Simcha [Dinitz] said that he had the feeling that Shaul and his friends were more worried than we were at the possibility that Egypt would take hostile action.”

Meir’s reply arrived the following morning: “As Shaul’s letter is already waiting in Cairo and he is of the opinion that the matter is urgent, the prime minister does not see fit to enter into an argument about the wording of the letter.” Its tone was both worried—“We too have received information about Egyptian preparations to open fire in the near future”—and practical—“The prime minister requests to ask Shaul whether this information has also reached them.”77 This wording replaced a different draft version in which Meir complained that she had not been given an opportunity to consider and react to the correspondence between Kissinger and Ismail. That draft still expressed an attempt to dictate to Kissinger his reply to Ismail.

After two days, Gazit updated Dinitz about Israeli suspicions regarding Kissinger and about the line of action Meir wished to adopt:

Her opinion is that despite the legitimate questions which I present here, she considers that Shaul has proven himself “above and beyond” and we should not now reproach him. She is also of the opinion that, at the beginning, you should earn his trust and thus we should avoid quibbling with him, If, heaven forbid, it becomes clear to us that we have no alternative but to have a confrontation with him, we will not recoil from doing so.78

In accord with Meir’s demands, Kissinger’s answering letter to Ismail, in which he proposed a date for a meeting, was delayed in Cairo. The designated date for the meeting, April 10, had passed without an alternative date being set. Sadat adopted the quickest means to expedite the matter—spreading a war alert rumor79—while aiming at another milestone in the process, the summit meeting in June. Ashraf Marwan reported quickly to his contacts and, on April 11, transmitted detailed information to Israel that the Egyptians were planning to open fire in May.80 The Israelis also received intelligence reports from other sources that did not correlate with the actual preparations for war in Egypt. Apparently, only two weeks later, Sadat met with Assad to begin coordinating plans that would be ready toward autumn.

Military intelligence chief Eli Zeira later used this fact in his argument that Marwan was actually a double agent who knowingly misled Israel. Zeira raised the possibility that this warning served Sadat as a trial balloon to test Israel’s reaction to an approaching war threat and determine how it would prepare for such an eventuality.81

Israel had to react to targeted threats of a war that could break out as early as the following month. Israeli decision-makers reacted with gravity to Egypt’s acquisition of armament but agreed, at this stage at least, that Sadat’s moves were made “to improve his cards and his chances to put political pressure on Israel and on the United States, and at the same time, to improve his internal status…. We do not distinguish any special activity in the region of the canal.”82 The Israelis knew that Egypt was still far from completing its rearmament.83 Defense Minister Dayan’s appraisal was most important:

In my estimation, Egypt is on track toward a return to war, whether this is being done consciously or unconsciously. I think that at least until the discussion in the Security Council and the summit meeting between Nixon and Brezhnev, the Egyptians will only threaten.84

Ismail finally received the message containing Kissinger’s suggested time for the meeting on April 12. In reply, he confirmed May 9 as the date the two would meet.85 Simultaneous to this determination, the immediate threat of military action evaporated. But in Israel, a small group of decision-makers would need to have a comprehensive discussion about expected military developments as quickly as possible.

Meir, Dayan, and Galili were the only ministerial participants in an informal discussion on April 18 at Meir’s home.86 They determined that Israel preferred to accept a coming war with Egypt, apparently in the near future, over a political agreement with Egypt mediated by the United States. This agreement, as noted, would have stipulated that Israel retreat to the international border between Israel and Egypt; in order to ensure its security, it would be permitted to maintain a presence at key points in Sinai (including Sharm el-Sheikh).

From the protocol of the discussion, it is clear that the three ministers decided without sharing information about these political developments, the details of the alternatives, and the significant security implications of each alternative with the heads of the intelligence and defense establishments. Despite Galili’s reservations, they decided not to share this information with the other members of the government or not to conduct the discussion this would have required.

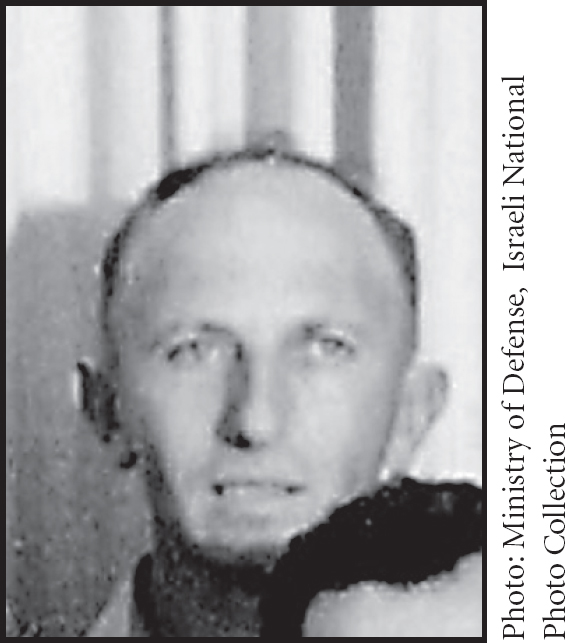

Zvi Zamir in IDF senior staff photo, January 1961

When they made this decision, the three ministers knew that the war would take place in the coming months, at a time determined by the Egyptians. They also had good reason to believe that Israel would not act in advance of Egyptian moves by carrying out a preventive attack or by calling up an increased number of reservists to heighten tension before war broke out. Kissinger’s words—“You will have to wait more than two hours”—were engraved in their consciousness. It is possible that Minister Galili only found out after the war about this informal obligation to the United States government, the price for its agreement not to force Israel into an agreement and to continue to supply it with planes.87

On Monday, September 12, 2011, I held a discussion with Zvi Zamir. The cameras and microphones of the Israeli television network Channel One recorded our conversation for the program Mabat Sheni (Second Look), which reexamined the Yom Kippur War. Itay Landsberg, the program’s editor, sat with us and participated in the discussion from time to time. Zamir’s book, With Open Eyes, which he had written with all his heart, was about to be published. I had already read it and knew that his discussion of 1973 focused on intelligence aspects. Zamir gave his answer as to “why it had happened” by discussing the failure of military intelligence appraisals regarding the likelihood that war would break out, as well as the fact that the military and political systems had blindly followed military intelligence evaluations. But I wanted to clarify the important question to which Zamir had not referred, not even in his book: Why had a war broken out? I knew that the answer to this question could not come from a discussion of the intelligence and the military realms.

I opened the discussion by saying:

You were there, in “Golda’s kitchen,” in the most intimate circle of decision-making. To a certain extent, you were there as an observer from the sidelines. The role of the Mossad, which you headed for five years, was limited “only” to special projects and to assembling information and data, not to research and evaluation. You were there because of your personality and due to the great respect Golda Meir had for you, and not just because it was required by your job description.88

I asked that we try to look together at the political developments of 1973: he as someone who had seen and experienced them at close range and in real time and I as a historian researching the period.

However, as I tried to share with him the account that had become apparent to me during my research, it became clear that the former head of the Mossad had only known about it in the most general terms. He had not been privy to the details of what had taken place in the channel between Kissinger and Ismail, nor those of the most secret channel between Kissinger and Meir via Rabin and Dinitz.89 The first to distinguish this, with its full import, was Landsberg, looking on from the sidelines. Time after time, he asked Zamir whether he was acquainted with the documents and if he had known the political consequences that could be concluded from them. Again and again Zamir answered in the negative. This was not because his memory had betrayed him. His memory was excellent. Nor did he answer like a court witness, exempting himself with an “I don’t know.” That was not Zamir’s character.90

Conducting research is prolonged in nature and is developed step by step. It is rare that the picture becomes clear in a flash of merging sources. This time, though, it had happened. Zamir’s answers completely correlated to what retired general Eli Zeira, who had been chief of military intelligence in 1973, had told me. He too had not been acquainted with the documents I had shown him, nor had he known of their content. In addition, as far as can be ascertained, David “Dado” Elazar, who had been chief of general staff, also received the most general report of these political developments.91 I now integrated his testimony and the picture I had already received with a document whose importance has already been known to researchers of the period. The protocols of the meeting mentioned above, on April 18, 1973, in “Golda’s kitchen,” now completed a clear and solidly based description that was astounding in its significance.

For this dramatic meeting, in addition to Dayan and Galili, the prime minister had invited Elazar and his office director Avner Shalev, Zamir, and Zeira. Also present at the meeting was the director-general of Meir’s office, Mordechai Gazit. A stenographer took notes of everything that was said. Those present were well acquainted with the targeted warnings Israel had received from a number of sources, foremost of which was the information Ashraf Marwan transmitted, which cited the middle of May as the time planned for war. Several dates had been mentioned, but May 15 was the most prominent among them. All of those present also were aware of the accelerated armament in Egypt.

At the beginning of the meeting, Dayan asked the three intelligence and defense representatives to present their appraisals regarding the possibility of Egypt initiating war. Each of the three replied at length. “There were no fundamental differences among them,” determined the Agranat Commission, which comprehensively investigated their evaluations.92 After they had finished, Meir and Dayan related their own reports.

Following this part of the meeting the ministers continued the discussion; Dado, Zamir, and Zeira remained in the room as listeners but did not take part in the discussion, as Zamir and Zeira testified and as the protocol noted. Meir, Dayan, and Galili did not reveal the details of what was transpiring in the Kissinger-Ismail channel or the Kissinger to Dinitz and Rabin to Meir channel. They already knew that the second meeting between Kissinger and Ismail, which was supposed to have taken place originally on April 10, had been postponed and would possibly take place on May 9. (In reality, it was again delayed and took place on May 20). Meir certainly knew that, in accord with her demand, Kissinger intended to continue to procrastinate in dealing with Sadat’s initiative.93

What Galili said at that meeting speaks for itself:

This whole system [Egypt’s preparations and threats of war] stems from the fact that we don’t agree to withdraw to the former line. In theory, if we accept what Hafez [Ismail] said…. The point of departure starts with this, that they are ready for peace and for a series of agreements and international guarantees and so on—all that on the condition that we make a full withdrawal to the former line.94

He proposed bringing the matter up for discussion in the government “because I feel that this requires a new mandate—that on our side, there is no agreement about returning to the former line and beginning negotiations on the basis of our response to a demand to return to the former line.” Government debate was necessary so that there would not be, in his words, “complaints in case [war] should take place.”

Dayan and Meir agreed with Galili when he suggested “a new mandate from the government, that on our side, there was no agreement to return to the former lines on any of the borders, but certainly not on the border between us and the Egyptians.” But they disagreed when he added, “It would also be possible to avoid this whole calamity if we are ready to enter into a series of discussions on the basis of a return to the former border.”

Dayan’s reservations were clear. He was ready to inform the cabinet ministers about the likelihood of war (“in very minor tones,” in his words), but he opposed any discussion of examining the political alternative:

But really, in very minor tones … we have to say that there is a possibility [of war]. The newspapers are all writing about it, the Egyptians are saying it, and the Americans are saying it, and Zvika [Zamir] says that the Arabs are now taking it more seriously. Yisrael [Galili], I would not suggest that it should be raised in the government in this context, whether we are ready even to go to war in order to avoid having to return to the Green Line. I don’t think that question is being raised at the moment…. I understand that we may go to war and that we are concerned about that, and it’s impossible for the government not to know something about that…. If it develops into a discussion like that, so be it, but in my opinion, we must raise it in the government as information. No one will guarantee us that the Egyptians won’t proceed to that.95

Meir added her support to Dayan’s opinion with regard to how to portray the military situation to the members of the government. She said nothing about presenting a political alternative: “We cannot enter into war if the government isn’t in the picture.” She added, “The government has to know, and if it doesn’t, why do we need a government at all?” To that, Dayan responded sarcastically, “That’s a good question, in and of itself. That’s a matter which is worth discussing.”

From the discussion between Meir, Dayan, and Galili, it is clear that it was not at all completely self-evident that the government had to be informed of the military situation and of the worry that war was about to break out in the near future. They finally decided to inform the ministers, although Dayan demurred and said that it should be done ambiguously. Galili thought that members of the government should be informed that a proposal for a political move to prevent the war also existed and thus wanted to involve them in the responsibility for rejecting such a move. Dayan disagreed. The prime minister ignored this point.

Meir referred to another aspect, stating that it would be advisable to ask the United States to try to prevent a war, but at the same time added, “What is important, whatever happens, is not to create the impression that we have become alarmed, and so they understand that that is not the point. We are quite sure of ourselves, but we do not want it to happen.”

Dayan was firmer: “We should not request their guarantee that it will not happen … because you know our friends there. They will make sure, first of all, that it is at our expense.” He was referring to the fear that the Americans would take advantage of Israeli concern in order to advance their own political developments.

Meir, as in many other cases, aligned herself with Dayan: “I propose that we tell them everything: There is information about it. On the ground there is still nothing. We are quite strong. We will remain in contact with them.”

Throughout the discussion, Galili was the one asking the difficult questions, which sometimes left the impression that the whole discussion, which seemed to be an annoyance to Meir and Dayan, was being held because Galili had requested it. This time he raised the forbidden question: Do we want war? He chose to present it in this way: “When Dado was speaking, he made a very significant statement. He said, ‘If it [war] happens, let it happen.’ But in his opinion, this necessitates that our behavior lead to a ‘meaningful resolution.’ Those are very intriguing words.”

Here Meir decided to use the censor’s scissors: “In all these serial novels, at this moment, we are stopping the tape.” But Galili insisted on receiving an answer. “If so, I say, just before stopping the tape, that we need an authorized explanation to decipher this thing.” Meir agreed to reveal her position more fully, while presenting it as derived from the conduct of the chief of staff, who no one would think was acting on his own: “He [Dado] said that they [the General Staff] are planning and preparing things. For the protocol, I announce that I do not want war. That will certainly surprise you.” Dayan sounded amused: “I have suspected you of that for a long time.”

Meir, who made a clear distinction between what would be accomplished but not appear in the protocol and what would appear, added what the stenographer wrote down:

On Friday I visited the Shor family [whose son Avida had been killed a week earlier in Operation Spring of Youth]…. His mother is all broken up about it and she told me, “I always said that I wasn’t at all worried. I didn’t fear for his life because he was holy…. I was sure that nothing could harm him.”96

The prime minister spoke sincerely; she almost certainly did not want a war. She spoke from the depths of her heart, but her eyes were wide shut and she consistently and decisively refused to take the necessary steps to avoid one.