![]()

MARVIN MILLER’S UNION CONTRACT

Two men transformed postwar baseball: Jackie Robinson (see the 1947 entry) and Marvin Miller. Robinson opened the game to people of talent, regardless of color. Miller enabled that talent to have a say in their destiny—and to profit from their skills.

When someone says, “It’s not about the money,” it’s reasonable to assume that it is. In the case of the baseball players’ union, however, it was not entirely about the money. The players had justified grievances that went much deeper. Specifically, due to the reserve clause, they had no say in where they played, and because of custom, they had almost no say in anything else.

The reserve clause, which dated to 1878 and eventually became a mandatory part of every contract, stated that players were the property of the team that signed them. Forever. Simply by enduring, the clause gained a kind of legitimacy. In congressional hearings in 1951, for example, a number of players, including Jackie Robinson, actually testified in favor of it.1 They had absorbed the idea that baseball would collapse in a heap without it.

There were other concerns, however, including the pension plan and working conditions. In 1954 the players started the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA). This had a few minor successes, but it had only one part-time executive and acted as an interest group rather than a full-blown union.

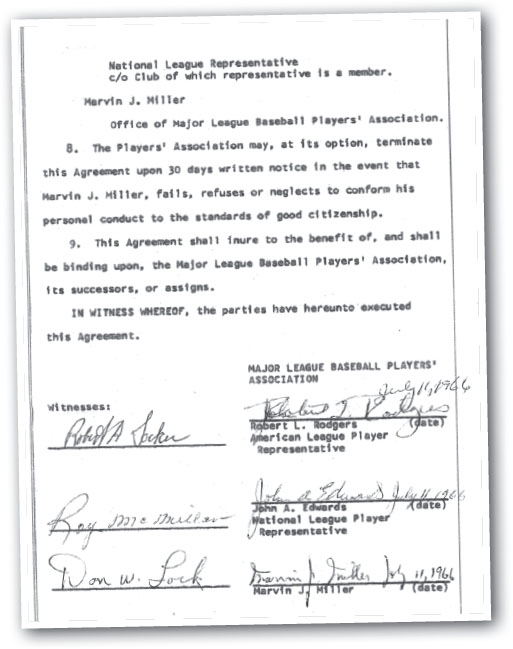

On July 1, 1966, that changed forever, when the MLBPA hired a longtime labor executive, Marvin Miller, as its first paid, full-time executive director. The picture on the following page shows that first contract; his confident signature is on the lower right. Miller had two great advantages. First, he knew labor law cold. Second, he was an outsider. Where baseball people saw practices such as the reserve clause as engraved on horsehide tablets, for example, Miller considered it “the most abominable thing I’d ever seen.”2

He was schooled in the facts of baseball life early on, when the owners summoned him a few weeks after he started, to inform him that they were changing the basis of their pension contributions. No discussion, no negotiation; here’s the deal, thanks for coming. Then it was Miller time. He proceeded to school them in the facts of labor law. You can’t do that, he told them. The MLBPA is a duly empowered collective bargaining agent—and that means you have to talk to me. Round 1 to Miller, by a technical knockout.3

In 1968 he negotiated the first collective bargaining agreement (CBA), winning a substantial increase in the minimum salary (from $7,000 to $10,000)4 and establishing some rules of engagement. It wasn’t easy. The owners, in the words of the MLBPA general counsel, Dick Moss, were both “hostile and patronizing”; they fought tooth and nail over everything, from meal money to baseball card fees.5 In 1970 Miller negotiated another CBA. Although this did not deal directly with the reserve clause, it contained a bomb, hidden in plain sight in the language of Article X, that would later explode the owners’ comfortable superiority. This was the establishment of binding arbitration to resolve player grievances.6

For a time it didn’t seem to matter. Management saw off Curt Flood’s courageous challenge to the system when he opposed his trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia before the 1970 season.7 In June 1972 the Supreme Court rejected Flood’s argument, on antitrust grounds, that he had the right to negotiate with teams other than the one that had signed him once his contract expired. The justices described the sport’s antitrust exemption as an “established aberration” that it was up to Congress to change.8 Between the lines, they advised baseball to play nicer. The owners failed to take the hint.

Nor did they appear to recognize how the game had changed with regard to the MLBPA. In early 1972 the players went on strike, mostly over pension issues. The owners didn’t believe they would do it, but they did. Then management was sure they would fracture. They didn’t. After 13 days and the loss of 86 regular season games, the owners blinked—and got their first inkling that the union was for real.

Although Flood’s lawsuit had failed, it was a useful failure that told Miller he could not look to the courts for action on the reserve clause. The case also brought the issue to public attention, and many people began to question, like Flood, the decency of a system that looked in all essentials like indentured servitude.

And Miller kept chipping away, improving conditions bit by bit while waiting for the right moment to strike at the reserve clause. One break came in 1974, when Catfish Hunter, the Hall of Fame pitcher, won a grievance against the Oakland A’s owner, Charles Finley, for failing to fund an annuity promised in his contract.9 The game’s independent arbitrator, Peter Seitz—the human form of the arbitration time bomb planted in Article X—ruled that Finley had indeed violated the contract, and that Hunter could sell his services on the open market. This he promptly did, signing with the Yankees for $3.75 million for five years, about seven times what he was making with the A’s. That opened players’ eyes to the reality that their market value—if a market could be established—was much higher than their pay.

With the authority of the arbitrator established, the next step was to figure out how to challenge the reserve clause itself. The language of the standard player contract read that if a player refused to sign, the club could “renew the contract for a period of one year.” Baseball had always interpreted this as one year, year after year, a perpetual renewal machine. Miller thought otherwise. Pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally agreed to play out their contracts and thus provide the basis for a test case.

Again, the case went to Seitz. The owners argued that baseball would descend into chaos and certain ruin without the reserve clause staying exactly the way it was.10 Miller and the MLBPA argued that a year meant 365 days, not forever. Again, Seitz agreed with the union. He had barely finished reading his decision when he was handed a note telling him that baseball no longer needed his services, but the decision stood. Messersmith, who became baseball’s first true free agent, promptly signed for more than double what the Dodgers had been offering.11

In the next CBA, the players and owners worked out a structure to allow players free agency after six years of service. It was a compromise that rewarded clubs for developing talent while allowing players to control part of their professional destiny. In its essentials, this system still exists.12

Settling a framework for free agency did not, of course, herald an era of good feelings. There have been numerous strikes (1980, 1981, 1985, 1994–1995) and lockouts (1973, 1976, and 1990).13 The loss of the entire 1994 postseason disgusted fans and probably killed the Montreal Expos. And while the MLBPA was surely on the right side of history in its first decade, it has not always been so since, such as in its approach to steroids (see the 2007 entry).

Marvin Miller set baseball players free—and set an example for football (free agency in 1992) and basketball (1996). For almost a century, the negotiating position of the owners was “take it or leave it.” Thanks to Miller, players forged a third option. It was the difference, Miller would say, “between dictatorship and democracy.”14

And the money wasn’t bad, either. In 1966, the year the players hired Marvin Miller, the average salary in baseball was $17,664. By 1982, the year he retired, it was $245,000,15 and in 2015, it was $3.4 million.16 The changes Miller provoked also made the owners much richer. In 1973 George Steinbrenner led a consortium that bought the Yankees for $8.7 million.17 In 2015 the market value of the team was estimated at $3.2 billion.18 The least valuable team, the well-run but largely unloved Tampa Bay Rays, was worth $625 million.

Like many prophets, Miller was not honored in his own time. Three times before his death in 2012, he was up for induction into the Hall of Fame. Three times the vote fell short, as did another try in 2014. His lack of a plaque in Cooperstown is almost incomprehensible—until one remembers it was just such stubborn blindness that he fought, and usually conquered.