![]()

YELLOW BLAZER FROM MONDAY NIGHT FOOTBALL

Being a loser can be liberating, and in the late 1960s ABC was the biggest loser on American TV. The advantage of that position, though, was that it could take more risks. And it got the chance of a generation when NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle (see 1960 entry) pitched the idea of a regularly scheduled prime-time game.

It was not an easy sell. Since the end of the Friday night fights in 1959,1 sports had only occasionally been seen after dinner; Rozelle had managed to shoehorn in a handful of prime-time games on a one-off basis, with middling results.2 He was sure there was a market. Under the terms of the NFL’s antitrust agreement with Congress, the league could not show games on Friday night. Saturday was for college; Sunday was already full of games, and midweek was out because players needed to recover. That left Monday.

CBS wasn’t interested. “What?” cried one aghast executive. “Pre-empt Doris Day?”3 NBC had a good thing going with Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In; also, Johnny Carson had not been amused when his show was delayed by a game that ran long.4 NBC was not going to mess with Johnny.

That left ABC. Its president of sports, Roone Arledge, saw all kinds of possibilities. Other executives saw only problems. Women wouldn’t watch; the affiliates wouldn’t like their evening newscasts interrupted; most fans wouldn’t have a rooting interest; and so forth. Fine, Rozelle said, Howard Hughes’s new sports network would take it. That got ABC’s attention, and with great reluctance, it paid $8.6 million for Monday night rights for the 1970 season.5

With that, Arledge took charge. He saw, before anyone else, that sports were not just about the game, but also about the people who played it and those who watched it. He wanted to show emotions as well as the score, and he wanted to bring a less reverent sensibility. “Sport is a business, not a religion, and there is no sacred way things must be done,” he said.6 “The games aren’t played in Westminster Abbey.”7

With Monday Night Football (MNF), Arledge had a template to test his vision. Again, ABC’s low status was helpful. Because it didn’t have any other football games, it could put all its energy into this one. ABC threw everything at it: slow motion, split screens, instant replay, handheld cameras, sideline mikes, closeups, and graphics.8 The network deployed nine cameras, compared to the more typical four or five, and two production units, one exclusively for replays.

Arledge wanted MNF to be interesting, and that meant the people calling the games had to be. With that in mind, he hired Howard Cosell, who was already known as one of the more provocative voices in sports. To provide contrast, he hired Don Meredith, the former Dallas Cowboys quarterback (see 1967 entry on the Ice Bowl), who did a nice line in cornpone. Veteran sportscaster Keith Jackson would do the play-by-play. It was the first time there had been three announcers in the booth.

Jackson was a capable professional, but it was the Cosell-Meredith dynamic that defined the show. Cosell was pedantic; Meredith punctured him with down-home darts. Cosell was ponderous; Meredith was funny. Referring to a receiver with the fabulous name of Fair Hooker, Meredith mused, “Fair Hooker—I haven’t met one yet.”

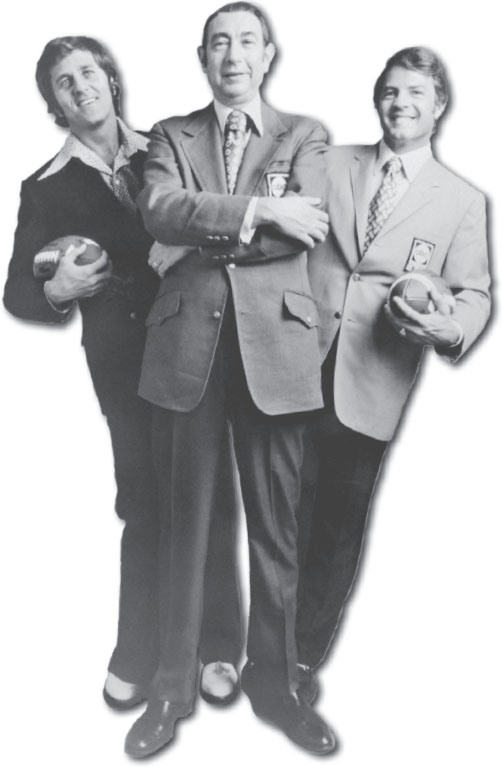

Right from the beginning, it worked. The first game, on September 21, 1970, between the Jets and the Cleveland Browns earned a stellar 34 percent share.9 Meredith won an Emmy for his work. The following year, Frank Gifford (right) replaced Jackson; he, Cosell, and Meredith, made MNF a national phenomenon. Movie theaters reported that sales slumped on Monday nights; bars began to offer customers a chance to throw bricks at a television featuring Cosell’s face.10

Football was already America’s favorite sport when MNF debuted, but the show helped to bring it to a new level, expanding the football audience. The show also proved that the appetite for sports was much bigger than anyone had thought and not as rigidly defined by traditional schedules. The year after MNF debuted, the World Series had its first prime-time game, and the National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball tournament followed a year later. Between 1975 and 1981 network sports coverage increased by a third, and new cable stations added many more hours.11 In 1979 ESPN launched; it was by no means certain there was a market for 24-hour sports at the time, but given the post–MNF sports boomlet, the idea was credible enough to attract backers.

Even when the personnel changed, MNF kept going. Meredith left in 1973 for NBC, then came back for a four-year stint in 1977. Cosell left in 1983. Arledge began devoting more of his time to ABC News in 1977, where he also made important contributions, including starting Nightline. Even so, Arledge, who died in 2002, seven years after Cosell, is best remembered as the most important person in the development of television sports (sorry, Howard). As for Monday Night Football, the voices in the booth keep changing, but the games go on and on. And the money gets bigger and bigger. The most recent deal, signed with ESPN in 2011, called for about $15.2 billion over eight years.12