![]()

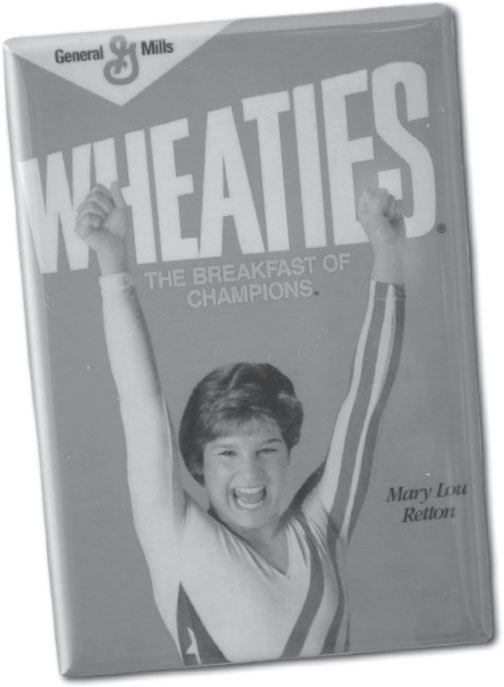

WHEATIES MAGNET WITH MARY LOU RETTON

The moment that American women’s gymnastics went from also-ran to global power can be plotted precisely. It occurred in a New York hotel room in 1981. At the end of a long evening, Bela and Marta Karolyi, Romanians who had discovered the great Nadia Comaneci and coached their country’s team to Olympic gold in 1976 and 1980, decided to stay in the United States. “The rest of the world laughed at American gymnastics before I came,” Bela later said.1 It’s the kind of thing the gregarious and egotistical coach would say—and that made him none too popular with his peers. But there is more than a little truth to the statement.

After their defection, the Karolyis’ first months in the country were difficult. They struggled with the language and took menial jobs as they worked to get their daughter out of Romania. With the help of friends, they were able to open a small gym in Houston in 1982. Before long, their athletes began to make a name for themselves. One competitor who noticed was Mary Lou Retton, who felt she needed more intense training than she could find in her hometown of Fairmont, West Virginia.2 She joined the Karolyis’ gym in early 1983, aged 15.

Over the next year Retton steadily improved, and in the run-up to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, she went on an extraordinary roll, winning major titles in both the United States and overseas. Until, that is, six weeks before the Games, when her knee locked up. After arthroscopic surgery (see 1958 entry) cleared out cartilage, Retton was in the gym the next day.3 There was just enough time to heal before the Olympics.4

Most of the Eastern bloc had stayed away from the Games—tit for tat for the US-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. But the Romanians decided to come; they had high hopes for reigning world champion Ecaterina Szabo, whom the Karolyis had also coached, and who was expected to challenge Retton for gold. Bela was not allowed to go on the gym floor, which was reserved for each team’s national coach. He wangled a floor pass as an equipment mover, which allowed him to flash signals from behind a barrier.5

Women’s gymnastics has four events: balance beam, uneven bars, floor exercise, and vault. The scores of each event are added up to determine the winner. With two events left, Szabo was ahead by .15, in large part due to a perfect 10 on the beam. Retton was a performer as much as an athlete, and she was about to go on the mat for the event that rewarded those qualities the most, the floor exercise. To the strains of “Johnny, My Friend”—a song that the Romanians had been known to use—she killed it, tumbling, smiling, and prancing to a 10. Szabo threw down a 9.9 on the bars and was still ahead by .05 as Retton prepared for her last and best event, the vault. Only a 10 would bring her outright victory.

Although she was no more than 4 foot 10, Retton was no pixie. She had the thighs of a speed skater and the shoulders of a linebacker. Her approach to the vault was decidedly aggressive; she sprinted as if she planned to run through it. Her speed gave her the momentum to sail high. Perfectly aligned, she whirled, twisted, and then stuck the landing. Retton flung her arms up, burst into her perfect, albeit crooked, smile, and flew into her coach’s arms for the first (but not last) Bela bear hug. Szabo hung her head. She knew, as the crowd knew, as the most ignorant television viewer knew, that this was a 10.

The faultless vault made Retton the first American—in fact, the first non-Eastern European—to win the all-around gold. She picked up three more medals in the individual events, and her gym-mate, Julianne McNamara, won gold on the uneven bars. As a whole, the US team came in second, behind the Romanians, its best performance to date.

Retton’s powerful athleticism and bubbly personality made her the breakout star of the 1984 Games. At the end of the year she and fellow Olympian Edwin Moses were named co-Sportspeople of the Year by Sports Illustrated. She also became the first woman to be the face of Wheaties, the “breakfast of champions.”

Retton competed for another year and then retired. By that time, streams of little girls had started gymnastics. Just as Retton had been inspired by Nadia Comaneci in 1976, the coming generation of American women was inspired by her.

In large part due to the Karolyis, US women’s gymnastics improved by leaps and bounds. From 1952 until 1984 the American women had not won a single medal. That dismal streak ended with Retton. Although the team just missed out on a medal in 1988—a controversial penalty cost them a bronze6—it has medaled in every Olympics since, including golds in 1996 and 2012.

Since the early 2000s the less demonstrative (and more popular) Marta Karolyi has played the bigger role on the American national team. The couple also runs a gymnastics camp on their ranch in east Texas; members of the US team train there regularly.7 Marta Karolyi has said she will retire after the Rio Olympics in 2016. When she does, it will be the end of a glorious era that began in that New York hotel room, when a young couple threw the dice on their future.