Commercial real estate consists of all nonresidential property types, including: office buildings, shopping centers, research and development parks, warehouses, and buildings designed for medical and other professional services. These are the types of commercial properties professional real estate managers most often manage. Two of the most striking distinctions between managing commercial and residential buildings are (1) the length of the initial lease term and (2) the complexity of rent payments. While it’s true that residents can remain in one apartment for many years, the tenant’s initial commitment is usually one to two years.

This chapter specifically focuses on the realm of office buildings, which is a unique type of commercial property that has special management requirements. Office tenants can expand their leased premises, relocate to a more favorable location within the building, or downsize—which usually doesn’t occur at a residential site unless the number of occupants changes.

Even the property analysis for office buildings is completed according to class of structure. Tenant selection, rent determination, and lease negotiations also require special consideration. Due to their differences from other commercial property, this chapter details the unique management requirements of office buildings.

The concentration of high-rise buildings within a community has come to be known as the central business district (CBD). Some of the largest cities have seen the development of multiple business districts both within the cities and in their surrounding suburbs. The high price of land and increasing congestion of the CBD fueled that development, along with the availability of business services that are concentrated in CBDs.

While skyscrapers may dominate a city’s skyline, numerous smaller buildings also require full-time management. High-rise buildings represent only a fraction of the office buildings that require and deserve professional management.

When a building owner and real estate manager or management firm sign a management agreement, they must examine the property objectively to discern its marketable qualities. The manager must learn how the tenants, prospects, and others in the market perceive the property in terms of desirability. It’s important to be very realistic about the property’s place in the market. For this reason, the integrity of the property should be studied, and the first procedure in this assessment is to examine the building for the purpose of classifying it.

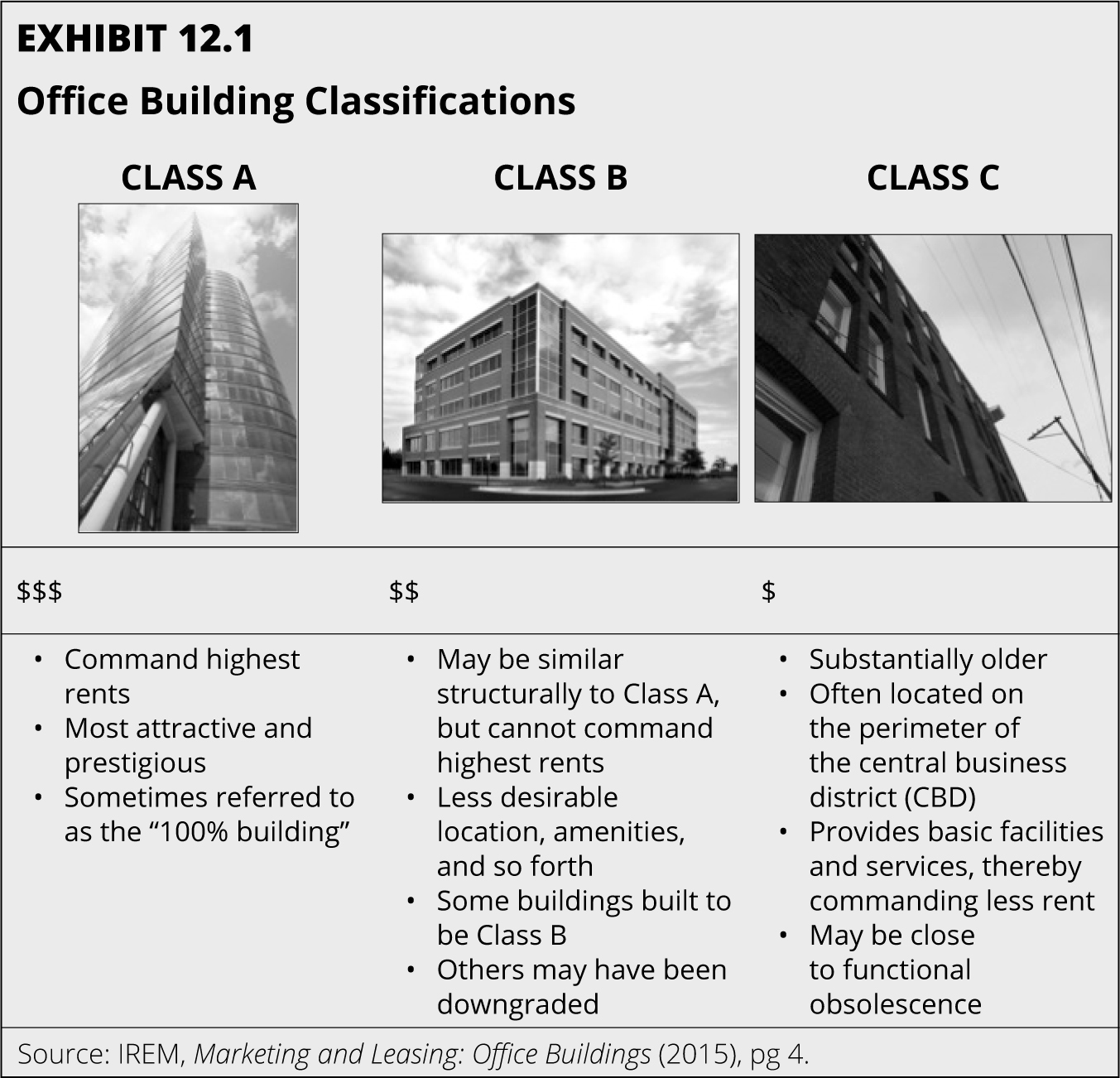

Although no definitive standard defines what constitutes a specific class of office building, many publications and industry experts commonly refer to three classes of office buildings: Class A, Class B, and Class C. Age and obsolescence are the two prevailing issues in building classification. An older building has the potential to be notable and appealing, but only if it can accommodate current business needs. If a building cannot be retrofitted for advanced office systems (e.g., wireless technology) or if the space cannot be configured for efficient use by current standards, the class—and therefore the economic potential—of the building is likely to decline.

Class A. These buildings attract the most prestigious tenants and command the highest rents in their areas. They have outstanding locations and accessibility. They are usually newer structures with the latest high-quality amenities such as conference rooms, concierge services, and fitness centers with state-of-the-art systems. Exceptionally well-renovated older buildings in the best locations are often categorized as Class A as well. A complete-service staff—including full-time maintenance and security personnel—is generally available in Class A buildings.

Class B. These buildings attract the widest variety of tenants because the rents are average for the area. The amenities and finishes are fair to good and the systems are adequate. The rents may be lower for many reasons such as the building being older, the location being less desirable, and the building offering fewer amenities.

Class C. These buildings attract tenants who need functional space, and rents are usually below average for the area. These buildings are older and reasonably well maintained, and they could possibly have been Class A or Class B at one point in time. Their amenities, finishes, and systems may be below current standards and may exhibit some degree of functional obsolescence or deferred maintenance. They may be located on the perimeter of the CBD, and their rents may appeal to those tenants who are most sensitive to price.

The classification of a building is an estimate at best. Visualizing the differences between Class A and Class C buildings is easy, but the distinctions between Class A and Class B buildings can be subtle. Regardless, the building classification can be useful to convey the desirability of the building in general terms.

Not surprisingly, the criteria that influence building classification are those evaluated by prospective tenants as they select office space to lease—current tenants also review these criteria when they consider renewing their leases. Thirteen factors are involved in classifying the types of office buildings; most of the factors are interdependent, but examining them separately illustrates their relationship and importance:

Location. The desirability of an office building is largely measured by its proximity to other business facilities, but it can change over time as one section of a city becomes more popular than other sections. Evidence of this is recorded in the history of most large cities. As the CBD develops, most of the buildings on the two main streets are Class A. With each block that is farther away from the main intersection, the property values and prestige decrease—even though the buildings may still be Class B. Some locations on the perimeter of the CBD may become less desirable because the expansion is in the opposite direction, which is an example of economic obsolescence. What was once a Class B building may now be Class C solely based on the location.

The effects can reverse as well. As growth of the CBD continues, the surrounding areas might become popular because they offer relatively inexpensive land and opportunity for expansion. If so, occupancy rates will increase once the buildings in the area have been rehabilitated or the land has been redeveloped. This will lead to an increase in income and an improved property classification.

Buildings developed outside the CBD can also be Class A. Companies often leave the city because land prices, business taxes, and rents are lower in the suburbs, which generates demand for offices in the outlying regions, resulting in the development of office parks, or business centers, near airports, major highways, malls, and other suburban attractions. Population growth in the outlying suburbs also provides a large pool of workers and customers from the local area. Another factor that influences the desirability of a location is the attractiveness and cleanliness of neighboring sites. If an office building is well constructed and maintained, it could be considered a Class A—especially if its surroundings are attractive and clean.

Besides the attraction of the CBD or a similar suburban location, the presence of a major corporation can influence suppliers and other associated businesses to locate nearby or in the same building. A major bank may attract investment counselors, brokers, and accounting firms to the site. Likewise, a bank that works closely with large businesses may consider proximity to its major customers when choosing a site.

The desirability of a location because of prestige or convenient access can overshadow most other factors. A strategic location near transportation, within walking distance of major business and financial centers, or adjacent to government services can make a 100-year-old building in sound condition as desirable to a prospective office tenant as the newest construction.

Accessibility and Parking. The ease of accessibility to transportation strongly affects building classification because workers must have an efficient and quick way to reach the office. Office buildings served by several transportation alternatives (buses, commuter trains, elevated and subway rapid transit lines, and highways) generally have greater value because employers benefit from the availability of a larger labor pool.

The availability of parking is also a consideration of accessibility. In general, buildings in CBDs cannot offer as many parking options as those in outlying regions; however, buildings centrally located in large cities usually do not require as much parking as those in suburban locations because of the availability of public transportation. If land in CBDs is available, parking areas are generally located underground or even above the office building itself since land is at a premium. More and more employers are offering incentives for employees to use public transportation or other eco-friendly alternatives to single occupancy vehicles.

Management. The quality of a building’s management is invaluable. Business people are aware of the influence management has on the appeal of a property and the efficiency of its services. Most office buildings have on-site management personnel, while smaller properties may have management based at another location.

The level of maintenance is a direct indicator of the professional dedication to the property. A well-maintained building with quality wood, polished floors, clean washrooms, dust-free cornices, and general tidiness is more attractive to current and prospective tenants. A prospect that discovers anything less will select a property that is better maintained. Upkeep of mechanical systems and the extent of building security are also indicators of management quality. The overall effectiveness of management influences demand for space in the building and contributes to the reputations of the firms whose offices are located there.

Prestige and Amenities. Image and reputation are important factors in business, and location can enhance prestige. For instance, an ambitious lawyer may want an office in the same building as the city’s leading law firms or at least in the same area. The directors of a financial institution will want it to be in the most desirable building in the financial district or as close as possible to such a center. Therefore, the building with a prestigious address and reputation ranks high on the scale of desirability.

Although much of the prestige may stem from location alone, the building’s ownership, reputation, management standards, and customer service can enhance its status. Building size contributes significantly to prestige. A building that is prominent in the city’s skyline may command higher rent because it offers the most prestigious views of the city. A large building can also include extensive and state-of-the art amenities that further enhance the site’s prestige.

Appearance. Two main physical attributes affect an office building’s desirability: (1) architectural design and (2) exterior appeal. Multistoried office buildings are often uniformly cubical or rectangular masses of glass, steel, and stone that lack distinguishing external features, but architectural creativity can give newer buildings distinctive visual appeal. Attractive older buildings may be retrofitted so they can support today’s high-technology uses. Buildings designed by famous architects like Frank Lloyd Wright or Frank Gehry most definitely add to the prestige and overall appearance of the structure.

Exterior maintenance contributes to the building’s overall impression and attraction. Fresh exterior flower displays, polished entrance doors and signage, and sparkling windows add visual appeal and welcome tenants, prospective tenants, and other visitors. The general curb appeal contributes greatly to property class. But class does not apply only to the physical appearance, it also includes the overall cleanliness.

Lobby. The appearance, floor plan, lighting, pleasant smell, and overall mood of a building’s lobby help establish the general character of the building. The entrance to any building is part of the setting in which each tenant’s business is conducted. A lobby that appears outdated, worn, or neglected detracts from an otherwise attractive building. It’s important to pay attention to the primary services that the tenants, employees, and visitors expect from a lobby as well. An updated, well-maintained building directory and unobstructed access to elevators or stairs are essential.

Elevators. In multistory office buildings, elevators are vital—each additional story increases the demand for efficient and rapid service. Several factors influence the perception of elevator quality—location is one of the most important. The desirability of space in the building will decrease if tenants, employees, and visitors have to walk a long distance from the main entrance to the elevators and then walk an equally long distance to their destinations after they arrive on the appropriate floor. Such inconvenience and perceived inefficient use of space create negative impressions of the building and its accessibility.

The appearance of elevator entrances and interiors can also affect the perception of the office building as a whole. Passengers expect adequate lighting, proper ventilation, understandable controls, and well-maintained floor coverings in an elevator. To create the illusion of a larger space, a mirror or other reflective surface on the back wall of the cab is sometimes helpful. Any lessening of aesthetic and maintenance standards in the elevator can raise doubts about the quality of the building’s tenancy and may even provoke questions about safety in the minds of the elevator passengers.

The two most important standards of elevator service are (1) safety and (2) speed; however, for passengers, speed includes more than travel time in feet per minute. They judge the amount of time their elevator trip takes from the moment they press the call button to the moment they arrive at their destination. The time spent waiting for the elevator to arrive and the number of stops it makes en route usually influence the perception of quality more than the actual rate of movement. Sometimes, depending on the character of the building, background music can offer a pleasant mood, while other buildings showcase their modern status by installing voice indicators for floor stops.

Corridors. The general decoration and details throughout the corridors should fit the occupants of each particular floor, while also maintaining a subtle, pleasant, and clean appearance. It’s important for certain floors and specific companies to have the freedom to express their company image and logo. For example, a design firm would most likely incorporate modern and updated colors in their corridors, while a law firm would display more neutral tones and subtle décor. Most important, staff must diligently maintain corridors in immaculate condition, and up-to-date signage should be clear, yet discrete and consistent in appearance throughout the building. Although allowing full-floor tenants to have some license in designing their elevator lobby area, it is important on multi-tenant floors to have a consistent look and quality from the ground floor lobby up through the upper-floor corridors.

Office Interiors. Office suites are usually configured initially or reconfigured later to accommodate new tenants’ needs and aesthetic choices. Desirability depends less on existing interior design than on alternative floor plans and the efficiency of the usable space—discussed later in this chapter. Numerous factors can limit possibilities for changes.

The size and number of windows in a given space and their relative locations often determine the size of the offices. In newer buildings that have expansive windows, the spacing of the mullions—vertical bars that separate the panes of glass—usually determines the placement of the walls. Sometimes it’s evident that interior walls are formed in line with the mullions and not directly in the middle of a pane of glass.

Other factors that can limit changes are the existing lighting, the depth of the space from the corridor to the outside wall, the width of the space between supporting columns, and even the view. Older buildings have more load-bearing columns that limit the efficiency of use and the flexibility of the space. Newer office buildings with sophisticated engineering usually have wider column spacing or even lack of visible supporting columns, which permits numerous alternative configurations and more efficient use of space.

In addition to layout, the perception of interior quality depends on decoration, wall finish, light fixtures, illumination, and ceiling height. Prospective tenants will judge all of these on their conformity or lack of conformity to the office interior that is available in the most prestigious building or space in the market. As with any other property, rental value of office space is ultimately based on what else is available in the market and what might better suit a tenant’s needs. In fact, some offices may be leased as-is, which affects the price and desirability. In other offices, each new tenant has the option of overhauling the interior to their own specifications, and in that case, the condition of the suite may not have any effect on price desirability. On the other hand, needing to spend less money might influence the tenant’s desire to lease the space.

Building Services. Prospective tenants judge an office building by the quality and variety of the available services included in the rent. Most important among these are custodial or janitorial services, security, prompt response to service requests by on-site maintenance personnel, after-hours access to the building, availability of after-hours HVAC, and HVAC maintenance.

Some office buildings provide special amenities for tenant use, such as conference rooms with extensive audiovisual equipment and exercise facilities. The presence in the building of retailers, such as stock brokerage firms, restaurants, banks, drugstores, and newsstands that serve the needs of employees, are also an asset. In some parts of the United States, office buildings may include a concierge or even daycare services, which could possibly be services provided by other building tenants. The selective tenant who is shopping for office space or simply considering a move takes note of these amenities and their direct or indirect costs, but for the most part, the availability of amenities frequently influences the prospect’s decision.

Mechanical Systems. Advances in office technology have increased demands on electrical wiring and HVAC systems. The mechanical systems are often a crucial consideration in a prospective tenant’s search for space to lease. Tenants increasingly request more power and bandwidth to support the growing use of video conferencing and other bandwidth-intensive applications. To keep pace with this demand, buildings continue to acquire smarter information systems that require more room for ducting and wiring. Newer buildings usually have state-of-the-art systems that can keep pace with user demands. They incorporate computer controls into the electrical and HVAC networks to monitor and regulate energy usage, and they include advanced wireless telecommunications systems.

Owners and managers may consider buildings that do not meet the infrastructure demands of new technology for retrofitting. However, many buildings—even relatively new ones—cannot easily be retrofitted to accommodate the many technological advances. In some cases, the costs of retrofitting may be prohibitive. In other circumstances, the design of the building may preclude an efficient or cost-effective retrofit. In fact, some buildings cannot be retrofitted at all. This functional obsolescence is one reason Class A buildings become Class B or Class C despite good locations and high management standards.

Tenant Mix. Image and reputation are crucial elements in business, and fellow tenants in an office building can enhance (or detract from) these qualities. For this reason, both the prospective tenant and the real estate manager of the property closely examine the tenant mix in an office building. A prospective tenant guards against other tenants who might not contribute positively to their reputation, or they avoid locations near direct competitors.

The principal tenant in the building usually governs the overall tenant mix. For example, if the major tenant is a bank, other financial enterprises—investment and mortgage bankers, brokerage firms, and accounting services—will seek space in the building because of that tenant’s reputation in its industry. The name of a major tenant is often applied to the building, and that can further encourage a particular type of tenant to lease space or discourage a major competitor.

Tenant mix is more vital to retail properties, but it’s important to be wary of prospects whose businesses may detract from the property’s image and reputation. Such a tenant may have a negative effect on the businesses of other tenants, which can result in a decline in the property’s reputation and income.

Sustainability. In today’s age of efficiency, it’s not just building owners and real estate managers who are focused on conservation. The Better Buildings Initiative was developed specifically for commercial properties because they use about 20 percent of the energy consumed in the United States. In this incentives-based program, national housing and real estate associations have supported the government’s plan to provide more generous tax credits and more incentives for owners who undertake costly retrofits on existing properties. Many programs exist for improving the building’s performance, but the two major organizations are (1) the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), which offers a LEED Certification, and (2) ENERGY STAR, which is a joint program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Dept of Energy (DOE).

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Certification. The USGBC, a nonprofit organization, offers a LEED certification—an internationally recognized green building certification system. This certification provides building owners and real estate managers the understanding needed to implement practical, environmentally friendly building design, construction, operations, and maintenance solutions. It leads real estate managers and owners to examine their building lifecycle patterns and even to go beyond the building into the neighborhood and local communities. The LEED certification is a performance-based system—designed to be comprehensive in its scope and simple in its operation—that offers earnable credits. There are four rating levels, including: Certified, Silver, Gold, and Platinum. These levels indicate a varying level of utility resource efficiency, using less energy and water, but also resulting in reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Tenants often seek out LEED-rated buildings to satisfy customer or client demands, fulfill a corporate goal, or simply to be on the forefront of ecofriendly efforts. Gaining this certification involves an elaborate process, but its overall goal is to increase the importance of sustainable development and its practice nationwide.

ENERGY STAR. The ENERGY STAR program was created to help the public save money while protecting the environment through energy-efficient products and practices. In its early initiatives, ENERGY STAR focused on creating specific products (such as dishwashers, refrigerators, and washing machines) that reduced greenhouse gas emissions, but it then expanded to cover the development of commercial and industrial buildings. This program functions much like the LEED Certification, where a rating system is in place that scores the building’s overall energy usage and performance. With the highest rating of 100, a building must score at least a 75 to be eligible to display the ENERGY STAR label. In earning and displaying the ENERGY STAR label, the real estate manager is highlighting the building’s achievements to the public by showing current and prospective tenants that the building has met strict energy efficiency guidelines.

IREM Certified Sustainable Property (CSP). The IREM (CSP) certification is an attainable, affordable, and meaningful recognition program for all commercial properties. The certification gains recognition for properties not covered by the previously mentioned programs, while extending sustainability across the real estate manager’s portfolio. This certification is a good way to start a sustainability initiative from scratch, if necessary. The following lists the prerequisites for office buildings:

The CSP allows real estate managers to train their staff on sustainability and resource efficiency, while also marketing the property’s sustainability success.

Just as an office tenant anticipates being in a building for several years, the real estate manager should seek tenants who can and will commit to a long-term relationship. The following lists four major criteria to consider for the prospect’s type of business and company reputation:

The value of an office building is based partly on the business reputations of its tenants. The prospect’s business should be compatible with the mix of tenants already in the building, and its reputation should enhance or at least reinforce the reputation of the building as a whole.

Investigating the credit of prospective tenants is often easier compared to checking residential prospects because the basic information about the tenant’s financial stability is usually public information. Ultimately, the property owner is responsible for reviewing and accepting or rejecting the financial condition of a tenant, but it’s the real estate manager or leasing agent who gathers the information. A prospective tenant should complete an application that lists the following basic items:

Financial statements, such as the Dun & Bradstreet credit rating (a leading source for commercial credit rates), local chamber of commerce or business organization, and the prospect’s bankers and suppliers are good sources of credit and financial information.

When determining the long-term profitability of the prospective tenant, it’s important to gather information on the company’s history. Consider the number of years in business, along with the company’s financial success. Requesting a prospective tenant’s business plan is not an odd request—especially if it’s a relatively new business venture. In fact, large multinational firms can potentially face bankruptcy just as suddenly as smaller firms.

Regardless of the company’s size or reputation, every potential tenant should be closely examined on a consistent basis. Investigate how the business is constituted as a legal entity by requesting articles of incorporation. In addition, confirm the authority of the person who will be executing the lease and that he or she is authorized to do so. When appropriate, seek legal advice for the necessary procedures for checking the Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons (SDN) List as provided by the U.S. Department of Treasury.1

One of the most complex issues of tenant selection is deciding whether the building has adequate space for a specific prospect. Efficient use of space is crucial, and some prospects may not qualify as tenants simply because the available space cannot be designed to comply with their requirements. The following three factors must be considered in determining whether the available space is suited to a particular prospect:

Space needs and office configurations change as technology fosters in-house teamwork. Some companies encourage employees to work at home, which often requires less overall work space. With fewer staff members working in the office, space can be allocated for shared use by workers who come in periodically—referred to as hoteling—or for groups to work together on projects. Those who work in the field or at home use temporary work spaces where they can plug into the network and use the phone and other office equipment. They may also use their inside time to attend meetings, give reports, or interact with other staff members, while other times they might telecommute. These and other technology-supported strategies have affected how much space is allocated for individual employees and work functions, which is sometimes less or sometimes more.

Prospective tenants always need special services to be able to conduct their business, and those requirements should be thoroughly considered in the qualification process. The following provide situations that require extra research:

If such factors are not given proper consideration, the building may operate at a loss because of a particular prospect’s tenancy. Before rejecting a prospect outright, analyze the actual costs and the cost-benefit ratio over the long term. Deciding who will pay for the proposed accommodation (tenant/capital improvements) is one of the lease terms to be negotiated. For example, a prospect may require extensive wireless access capabilities and may be seeking an office building that has a state-of-the-art wireless system. Meeting these requirements may necessitate a large investment, and retrofitting a building for wireless technology cannot always be done successfully. However, evaluation of an accommodation is warranted for the following reasons:

New office space is commonly leased as shell space—enclosed by outside walls and a roof, with a concrete slab floor and utilities in place. The plumbing and electrical installations are unfinished, and the space has no partitioning walls, ceiling tiles, wall coverings, or flooring. Office users generally have unique requirements for the space they lease, and it is easier to design and build out an unfinished space. Construction of tenant improvements may be done according to the incoming tenant’s specifications. Even a previously rented space may be gutted and rebuilt for succeeding tenants. Similar to shell space, vanilla shell space refers to spaces that usually have an American Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant restroom, walls ready for paint, floor ready for floor coverings, and ceiling tiles and lighting in place.

Rent is usually charged on a per-square-foot basis. It may include repayment of some or all of the monies advanced to finance tenant improvements to the leased space. Some property operating expenses—real estate taxes, insurance, common area utilities, and maintenance—may be included in the rent or charged separately on a pro rata basis. Tenants’ electricity or other utilities may be metered individually, and the utility company may bill the tenant directly. Submeters may also be installed on shared utilities that determine the exact usage for a particular tenant and billed accordingly.

Accurate measurement of the space is crucial to maximize rental income and the market value of the property. Three concepts are central to the measurement of office space (Exhibit 12.2):

In order to establish profitable rental rates, know how much space in the building generates revenue (rentable area) and how much of that space can actually be occupied (usable area). Accurate measurement of the rentable area is extremely important. In a building that has 100,000 sq. ft. of rentable area, a one percent error would amount to 1,000 sq. ft. If the average rent were $30 per sq. ft. per year, that one percent error would result in a loss of $30,000 in rental income each year. The resale value of the property would likewise be reduced; at a capitalization rate of 10 percent, the $30,000 shortfall would lower the property value by $300,000.

Usable Space. The usable area of a tenant’s leased office space is the area bounded by its demising walls—the partitions that separate one tenant’s space from another—the interior of the corridor wall, and the interior of the exterior wall. The usable area is available for the tenant’s exclusive use. This area may occupy a portion of a floor, an entire floor, or a series of floors. Although the usable area is the amount of space in the tenant’s sole possession, rent is usually quoted on the rentable area.

Rentable Space. The rentable area of a tenant’s leased office space usually includes certain common areas in addition to its usable area. In a multistory office building, the tenants on each floor pay additional rent, or common area charges, for those spaces on the respective floors. Each tenant’s pro rata share of the common area of the floor is the percentage represented by the ratio of the tenant’s usable area to the usable area of the entire floor—the sum of all defined usable areas on that floor. In addition, all tenants in an office building pay rent for their proportionate share of building common areas—the ground-floor lobby and any other common areas, including conference rooms, mailrooms, building core, visitor or shared restrooms, and service areas that mutually benefit all tenants.

Standardized Measurement. To avoid discrepancies, the standardized method used by the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International2 is usually adopted. The Office Building: Standard Methods of Measurement (ANSI/BOMA Z65.1 2010), which can be obtained from BOMA, includes definitions, illustrations, and calculations. This standard, commonly referred to as Method B, discusses the single load factor method, which is an updated calculation applied to the occupant area of each floor to determine the rentable area and is the same for all floor levels of a building.

The International Property Measurement Standards (IPMS) is an international standard for measuring office space that is globally accepted in the industry.3 The recommendation for all measurements are supported by CAD (computer-aided design) drawings or BIM (building information modeling) data. There are three basic area definitions used:

The standard method computes a tenant’s rentable area by multiplying the tenant’s usable area by an R/U ratio, which is the rentable area of a floor divided by the usable area of that same floor. A pro rata share of the building’s common areas is then added to the basic rentable area to arrive at the tenant’s total rentable sq. ft. The larger the R/U ratio, the greater the rent paid for the common areas. Prospects are usually more inclined to choose rental space that has the lowest R/U ratio. Older buildings usually have high R/U ratios, which is another characteristic used to classify buildings—similar to classes A, B, and C that are previously described in this chapter.

In some markets, an add-on factor (or load factor) may be used to account for the proration of the common areas among individual tenants. This may or may not be equal to the ratio between the rentable and usable areas. Some markets may establish a standard or accepted add-on factor. In other words, the R/U ratios of buildings in the CBD may range from 10 to 13 percent, but a standard add-on of 11 or 12 percent might be applied to all usable area rents in the market. This can effectively eliminate one point of negotiation on a market-wide basis. (Exhibit 12.3 is an example of an add-on factor based on the R/U ratio.)

Developing the building standard for finish elements throughout the building is a task shared between the real estate manager and the property owner because it defines the quantity and quality of construction involved. Some of the finish elements may include materials for partition walls near corridors and regular interior walls, as well as some of the following components that must be considered in making decisions:

The building standard should also address electrical wiring, switches, electrical and telephone outlets, and supply-and-return air vents for HVAC, while specifying compliance with applicable codes.

The dollar amount for the tenant improvement (TI) allowance is also discussed with the property owner when establishing these building standards. Since this allowance is a negotiable item, it can be based on the use of building standard materials—the tenant may be responsible for any cost overruns. If materials other than the building standard are used, the tenant will most likely be responsible for the difference in cost.

Since market quality standards evolve as new materials and new technology become available, the building standards should be periodically reviewed and updated. Building codes and other relevant regulations also change from time to time. All these factors can affect building standards. For instance, the accessibility requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) affect both building rehabilitation and new construction, and should be a consideration in planning TIs as well.

The rental rate for a building depends on local practice and market conditions. Rent for office space is commonly quoted per square foot, either per month or per year. To determine the rent, first establish the lowest acceptable dollar amount per square foot that will offset debt service, operating expenses, and vacancy loss—and yield the owner’s desired return on the investment.

If the calculated rental rate is greater than the market will bear, the real estate manager will have to examine alternatives for reducing expenses in order to lower the rent to be competitive. Otherwise, the owner may have to accept a lower return on the investment. In ideal circumstances, market conditions will allow rents to be higher than the calculated rate. The marketplace will also dictate whether and which operating expenses the owner can include in the rent or charge directly to tenants on a pro rata basis.

As with any other property, the rent that an office building earns depends on its condition and location. In most markets, higher floors and better views command higher rental rates. In terms of height, both extremes of the building will need to examined. The anticipation of high income from upper floors must often be tempered with lower expectations for office space closer to the ground. Although a high-rise office building will most likely generate a considerable amount of income from its upper floors, that amount may not be sufficient to yield a high income for the building overall.

For example, a desired average rental rate of $30.00 per sq. ft. might be calculated per year for a 50-story, class A office building. A spectacular view in this structure creates high demand for space on the upper floors, most of which can easily be leased at rates between $40.00 and $45.00 per sq. ft. per year. However, the lower floors cannot expect to command such a high rent, so space might have to be leased on those floors for rates that are at or below $30.00 per sq. ft. per year. Ideally, the income the upper floors produce should offset the lower rates achieved from the lower floors.

In CBDs, leasing ground-floor space to retailers may be possible, and that can yield additional rent. Retailers may pay higher rates for the space. Sometimes the rents for ground-floor retail space are just as high as, or higher than, the rents for the top floors.

A business that is seeking office space will always be concerned about the comfort of their employees and the efficient use of the space they lease. During the space planning process, prospective tenants require the real estate manager’s assistance when determining the optimum square footage they will need. If a tenant pays for unused space, they are essentially wasting money. On the other hand, crowding too many employees into an office can easily waste the same amount of money through inefficiency.

Space planning truly incorporates the prospect’s square footage requirements, organizational structure, aesthetic preferences, equipment needs, and financial limitations into the design of a specific floor plan that indicates how office equipment, rooms, and hallways will be placed in the rental space to optimize work flow. In some cases, a space planner, designer, or architect prepares preliminary drawings. Computer-aided design (CAD) equipment can quickly and economically create different space arrangements for visual purposes (Exhibit 12.4). After the lease negotiations are completed and confirmed, detailed plans are then prepared and later implemented.

A significant point of negotiation between the real estate manager, prospective tenant, and the owner is the payment of the cost of constructing (building out) the tenant’s space. Usually a tenant improvement (TI) allowance covers standard items that will be installed at no cost to the tenant. For example, installing one phone jack for every 125 sq. ft. leased, or including one door for every 300 sq. ft. If such a quantitative approach is not used, the allowance may be stated as an amount of money the owner will provide per square foot of leased space.

Whether the owner or the tenant pays for construction costs that exceed the standard TI allowance depends on the market conditions and occupancy level in the building. One of four options is possible:

While a loan paid back via rent is common, the tenant can also seek financing from other sources or pay for the construction outright. TIs are more frequently used as an incentive in a renter’s market than in an owner’s market. Because a commercial lease is usually a long-term contract, sacrifices early in the term may have lasting rewards for both tenant and owner. However, incentives that are too liberal may attract prospective tenants who are less than ideal candidates for the space, and that can burden the property with excessive expenses for many years.

It is important to note that a significant investment in TIs by the building owner at the beginning of the lease will take many years to recover—either with an amortized payback by the tenant or in higher rents. Should the tenant fail and vacate early in their tenancy, the owner may not realize any ROI, depending upon the outcome of any collection activities or negotiated termination settlement. Property owners should be cautious when investing large sums in TIs for start-up firms or firms in less than stable industries. In those instances, owners may negotiate lower rents for tenants that provide their own TIs, reducing the initial outlay of cash from the owner and reducing the risk of loss.

No matter how payment is arranged, the real estate manager and property owner will retain final authority on all construction in the office building. A construction firm is usually contracted to complete the build-out of a multitenant office building by the owner or the real estate manager working on the owner’s behalf. The supervision of construction ensures that the integrity of the property’s image will be maintained, which is a nice benefit for the tenant because it ensures high-quality workmanship at the lowest cost. Another benefit is that the owner’s preferred contractor is usually more familiar with the building and its systems, which reduces the overall costs of construction and provides knowledgeable, realistic estimates and timing of the work so that move-in is on schedule.

In special cases, the owner (or the manager on the owner’s behalf) can allow the tenant to contract for the construction. This may be the case in offices in flex spaces, which are single-story structures designed to facilitate different configurations that accommodate both large and small space users, as well as some non-office uses, such as lab assembly or light manufacturing. When dealing with flex spaces, the tenant must meet strict conditions, such as the owner’s preapproval of plans, use of approved licensed, bonded contractors and subcontractors, and requirements for specific insurance coverages and lien releases after construction is completed.

A less common agreement involves office condominiums, which offer ownership of the office space as an alternative to leasing. They appeal to medical and dental practitioners, real estate firms, financial planners, entrepreneurs, and small companies that need 1,000 to 10,000 sq. ft. of space.

Not only do owners acquire equity in the property, but they are also able to project and control their costs of occupancy. Office condominiums do not offer much flexibility to expand or contract as businesses need change. Like residential condominiums, office condominiums offer different challenges for real estate managers. In certain situations, the real estate managers might serve as an association manager, which is common for condo association management.

For many years, well-located medical office buildings (MOBs) have been considered very stable commercial real estate investments. MOBs, whose space is leased primarily to medical and dental professionals, must be modified to meet those tenants’ needs for additional—sometimes specialized—plumbing and electrical wiring. Since the nature of their clients are patients who are ill, there is more exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other hazards; therefore, the services MOBs provide mandate special care in cleaning and waste disposal, and the lease must address those issues. Entrances and other common areas—including parking—must accommodate disabled and ailing individuals, and may require larger doorways for stretchers and/or unique entrances for ambulances or other specialized cars. In addition to doctors and dentists, other possible tenants within MOBs include pharmacies, biomedical laboratories, physical therapists, optical services, pain management clinics, and health maintenance organizations. For new and repositioned MOBs, excellent facility and asset management services are essential, along with specialized marketing and leasing, repositioning strategies, sales and acquisitions, and even design and development services.

For the most part, MOBs are costly to develop—TIs cost two to four times those of standard office buildings. Therefore, the TIs are amortized over longer periods, and leases typically have 10-year terms instead of the standard three- to five-year term for regular office leases. However, a benefit of working with MOBs is that tenant turnover is extremely low, especially when they reach a stable occupancy. More detailed information on MOBs and clinical facilities management can be found in the IREM publication, Managing and Leasing Commercial Properties, Second Edition (2016).

Office buildings are a unique kind of commercial property since they are often in the CBDs of cities and suburbs. Whether a building is 100 years old or the newest 100-story skyscraper, the value of its rental space to tenants depends on its location, structural components, proximity to transportation, prestige, tenant services, management standards, and tenant mix. As office buildings continue to evolve, many current trends in office space design are the result of technological advances and environmental policies, as well as tenant needs. Long lease terms, complex rents, and tenants’ desires to maximize the ability of their businesses to prosper in the spaces they rent make lease negotiations crucial to the successful management of office buildings.

1. The SDN is a list of individuals and companies owned or controlled by, or acting for or on behalf of, targeted countries. It also lists individuals, groups, and entities, such as terrorists and narcotics traffickers, designated under programs that are not country specific. The assets of these individuals are blocked and U.S. persons are prohibited from dealing with them.

2. BOMA is a trade association that serves the commercial real estate building industry.

3. The IPMS standard for office buildings does not replace existing methods of space measurement. Rather, it supplements and interprets them so that people are speaking the same language when sharing measurements—they are considered an overlay to local measurement standards

4. The eight components are as follows: (1) vertical penetrations (stairs, elevator shafts); (2) structural elements (walls, columns); (3) technical services (maintenance rooms, elevator motor rooms); (4) hygiene areas (toilet facilities, shower rooms); (5) circulation areas (horizontal circulation areas); (6) amenities (cafeterias, daycare facilities, fitness areas); (7) workspace (furniture, equipment for office purposes); (8) other areas (balconies, internal car parking, storage rooms). Source: https://ipmsc.org/standards/office.