2

PUT FRONTBENCHERS WHO BRING VOTERS ALONG WITH THEM INTO KEY PORTFOLIOS

We are back in the cave of the anguished election loser. Was it all your fault? Did you get the help you needed from colleagues to attract enough swinging voters to win? Or were you alone out in front of the team, having to do all the heavy lifting? Did you have to recover ground lost through colleagues’ missteps, or fill a vacuum when less skilled or lazy frontbenchers were bested by their opposite numbers? Did you suppress a nagging thought that you could make better use of talented colleagues? Are you short of talented colleagues in the first place?

We don’t expect the captain of a football team to win on their own. A great captain can make an absolute difference, but a great captain alone is not enough. One Australian Football League (AFL) team recently did a real time experiment in this: the Gold Coast Suns whose founding captain Gary Ablett Junior led the newly created team from 2011 to 2016. Ablett was the best player in the league on arrival and continued playing extraordinary football, yet the Suns finished 17th, 17th, 14th, 12th, 16th and 15th on the AFL ladder in those years respectively. A brilliant captain is not enough.

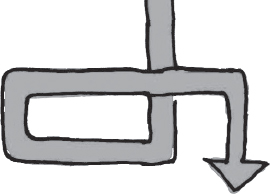

Earlier I expressed a quixotic hope our political parties might manage themselves as well as the best sporting teams. In football,

•a director of football or manager oversees the football department, makes sure the right support staff and resources are in place, and manages the coach;

•a list manager identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the team, and recruits and trades players to make it the strongest and most balanced possible;

•a coach makes sure the right players are in the right positions with the appropriate strategy and tactics to win on the day, over the season and in the grand final at its end; and

•a captain leads the team on the ground in each engagement with an implacable drive to win.

Up and down that line and across the team are continual conversations about what is going right, what can be done better, and how people can be skilled up and motivated to do so. The overall strategy is known, continually communicated and understood. Tactics are crafted inside that strategic framework to deliver on the strategy, in fine tactical detail, right down to optimising individual week-to-week match-ups against the opposing team. What you are eating, how you are exercising, and how you are managing stress, are all vital team business. If your private life gets untidy during the season it could impact your, and therefore the team’s, performance so that’s on the radar for care and attention too.

While the team performs well, the director of football is left to get on with it. If the team isn’t going well, the CEO questions the director of football to find out why and help fix things. If the situation deteriorates further, the board presses the CEO about why that’s happening and what is being done about it. If a team keeps losing, hard decisions are made. The coach may drop players, even marquee ones, if they are not performing – during the season, not just when the grand final is over. The director of football may want to sack the coach. The CEO may sack the director of football. The board may sack the CEO. There are transaction costs. These things are not done lightly, or even often, but a culture of permanent attention to performance and accountability for it, in the context of a lot of practical support and upskilling, makes football the compelling spectacle so many Australians know and love.

In contrast, in politics the leader (captain) has unfettered power over some things and an overwhelming say on the rest, with little to no accountability between elections beyond holding onto their position or not. The Review of Labor’s 2019 Federal Election Campaign by Craig Emerson and Jay Weatherill for the Australian Labor Party National Executive made eight findings on the question, ‘Why did Labor lose?’1 Two of the eight findings concern the lack of a structure through which campaign problems could be identified and dealt with in real time rather than after the election when it was too late.2 Another five concern the problems this lack of structure created. So all but one of the eight findings answering the question, ‘Why did Labor lose?’ were rooted in Labor’s flawed structure and the problems flowing from it.3

‘Culture’ is mentioned once in the ‘Why did Labor lose?’ section, adjacent to the word ‘structure’: ‘Labor’s campaign lacked a culture and structure that encouraged dialogue and challenge, which led to the dismissal of warnings from within the Party about the campaign’s direction.’4 Recall the leadership team ‘groupthink’ problem discussed in the prologue. The point of an effective structure is to create structural opportunities for problems to be raised and addressed, so as not to make this reliant on the existence of a positive culture where such discussions would happen anyway. Leadership team ‘group-think’ strenuously repels these kinds of discussions. That is why structures where such conversations can happen are needed, as well as a culture with accepted processes to ensure the structures actually get used for the purpose designed. If not, they are just meaningless entries on party organisational charts.

The review underlined the need for a forum for ‘formulating an effective strategy (and) for receiving reports evaluating progress against the strategy’.5 In a world of Darwinian leadership competition, the danger is that adverse reports could be leaked from it by rivals to undermine a leader with a view to replacing them. However, the party rules of both Labor and the Liberals now make changing leaders between elections extremely difficult, so this argument (at the moment) is a weak one. In any case, the price of faulty political strategy is so high that the risk of unflattering leaks is worth running because the alternative – losing – is worse, as Labor’s unnecessary 2019 election loss showed.

The Liberal Party and its coalition partner, the National Party, do not differ much from Labor in all this. They have suffered their own shock losses, notably the 1993 election when Paul Keating defeated John Hewson in the so-called ‘unloseable election’, learning lessons they have not yet forgotten. The truth is that Australian football teams have better operational structures and performance-oriented accountabilities than Australian political parties. While you are winning, it doesn’t matter. When you’re losing, it matters an awful lot.

Media is also an issue. The football media also does a better job of reporting the performance of football teams than Australia’s political media generally does of reporting political parties. Tune into one of the mid-week AFL chat shows and you’ll hear an exhaustive analysis and discussion of each team’s ruck, midfield, forwards and backline performance in the context of the team’s current and historical strategy, tactics, overall performance, injury rate and key match-ups against the opposing team. Tune into the weekend political chat shows, however, and there is little discussion of the parties’ frontbench team performance, how the match-ups are going in various portfolios, whether the right politicians are playing in the appropriate position, and how well they are doing. The focus is overwhelmingly on the leaders, contentious issues of the week, and how just two metrics – the party vote and leader popularity – are moving.

Yet how key ministers and shadow ministers perform in their portfolios is vital to winning elections. Economic management capacity, for example, is crucial to electability. How did the match-up of Liberal treasurers Scott Morrison (2016–2018) and Josh Frydenberg (2018–) go against Labor shadow treasurer Chris Bowen? You cannot tell from Labor’s election review, in which Bowen is mentioned on just three pages compared to Shorten’s 28 pages.6

Treasurers and shadow treasurers are like the ruck in AFL whose job is to tap the ball to their own team’s players at the bounce, denying their competitors possession of the ball. A lot flows from this. If your team keeps losing the bounce on economic policy, it’s very difficult to win a game let alone make and win a grand final. Your opponent already has the ball and can try to kick goals in other policy areas, having secured the economic management ground. There was never a sense Bowen was winning the centre bounce. Rather Labor had a ceaseless struggle to explain complicated policy initiatives. Despite emulating some aspects of Paul Keating’s political style, Bowen did not develop the cut-through persuasiveness nor the brilliant analogical reasoning that made Keating so successful as treasurer in the Hawke Government.

After the election Bowen’s surprise at the poor response to his leadership candidacy – he withdrew from the contest after just one day, realising he had no chance – suggests qualitative research on how he was perceived was either not done or not shared with him between the 2016 and 2019 elections.7 Worries about Shorten’s media persona among those concerned that defeat lay ahead were accompanied by worries about Bowen’s somewhat haughty media style. Shorten and Bowen lacked self-awareness about how they came across in the media. In Bowen’s case it crystallised in his extraordinary statement in relation to one element of Labor’s platform, that ‘if people very strongly feel that they don’t want this to happen they are perfectly entitled to vote against us’.8 The absence of self-awareness continued. Announcing his candidacy for the leadership after the election, for example, he argued correctly that Labor was not ‘talking the right language’ to working people but used words like ‘redistributive’ and ‘recalibrate’ to make his point and simultaneously embody the problem.9

Bowen’s issues were not just presentational. He made the strategic error of ‘fighting the last war’. The Labor election review notes Bowen’s ‘searing’ experience during the 2016 election campaign of finding mid-campaign that Labor’s short-term budget bottom line was weaker than that of the government. In 2018 he committed Labor to ‘bigger budget surpluses over the four-year forward estimates and substantially bigger surpluses over ten years’ to avoid this at the next election.10 Labor’s election review did not go on to explain that this made Bowen’s own task at the 2019 election so much harder, having to find bigger revenue initiatives to fund Labor’s spending promises than he would have had to otherwise.

Enter the franking credit policy.11 Bowen publicly drew comfort from the Labor election review noting, in Finding 39, that voters most likely to be affected by the franking credit policy swung to Labor, while poorer Australians not directly affected by it swung strongly against it.12 The latter was put down to ‘scare campaigns’ fanning ‘fears about the effect of Labor’s expensive agenda on the economy’ among poor and less educated voters.13 That the franking credit policy was an element in the scare campaign deterring poor and less-educated voters voting Labor was fudged in the review. Nor was the fact that Bowen’s extreme toughening of Labor’s fiscal position in 2018, likely related to memories of adverse budget bottom line revelations in the 2016 campaign, made big money-saving initiatives like the franking credit policy necessary.

Most poignant of all is that this toughening of fiscal policy was done just as the economic cycle suggested a loosening was in order, as the Australian economy slowed. Bowen was not just poor at winning the ruck against Morrison when he was treasurer and later Frydenberg, he didn’t read the bounce of the ball after it was in play either.

None of this is to suggest Chris Bowen is a terrible person, just that he was playing in the wrong position and, like the rest of humanity, has things to learn – the learning costs of which, like Shorten’s, have been externalised onto Labor’s supporters through the election loss. Nor is this unique to Bowen and Shorten. Many variations on this theme have played out over the last several elections, hence the need for this book: to find a way of stopping different heads banging on the same brick walls election after election.

The career of another Labor frontbencher perceived as an unsuccessful economic spokesperson – John Kerin, treasurer at the end of the Hawke Government for six months after Keating went to the backbench – is instructive. Kerin did not cut it as treasurer for various reasons, but was a brilliant primary industry minister for eight years and in doing so strengthened Labor’s vote in rural and regional seats, helping it win and stay in government.14 He was of that world, accepted and liked in it, and developed quality policy that was understood and appreciated in that realm, consistent with the Hawke Government’s philosophical and policy framework.

Jenny Macklin, Labor’s first female deputy-leader and an outstanding minister in the Rudd and Gillard governments, is another example of the right player in the appropriate position performing strongly and contributing vitally to collective political success. Recognised in her own right as one of Australia’s leading social policy experts, Macklin was widely liked and respected in her field for combining brains, heart and economic responsibility to make good, sustainable policy for her portfolio constituencies, consistent with Labor values.

Neither Kerin nor Macklin were flashy politicians and encomiums are not being written on their careers, as deserved as they would be. Have enough Kerin- and Macklin-style successes across a range of portfolios, however, and the frontbench can really lift a party’s performance, making the chance of even an average leader winning that much more likely.

Shorten and Bowen playing captain and ruck for Labor had a lot in common with John Hewson and Peter Reith in the same positions at the ‘unloseable’ 1993 election the Liberals lost. They had the same ‘groupthink’ and lack of perspective on each other’s shortcomings because those shortcomings were so similar, and experienced the same surprise election loss.

Let’s imagine, though, that Shorten did realise a different shadow treasurer was needed to maximise his chance of winning. Bowen is leader of Labor’s New South Wales right faction and as such has his own power base. Shorten perceived his hold on the leadership to be fragile. Unless he could persuade Bowen of the merits of shifting to a different portfolio, moving him could have destabilised Shorten’s leadership, increasing the chance of a leadership rival making a move.

This kind of calculus is human, but self-defeating. Is the strategy to win the election or hold onto the leadership? If the price of holding onto the leadership is losing the election, with the prize at best being another miserable term as opposition leader, why not go for broke and try to replace underperforming frontbenchers, even powerful ones? Bill Hayden replaced Ralph Willis as shadow treasurer with Paul Keating just before losing the leadership to Bob Hawke; had he done it sooner he may have survived to lead Labor to the 1983 election. I can’t think of a single football captain who would put keeping hold of the captaincy ahead of winning a flag: the team’s fortunes are paramount. This is why football clubs put a lot of time, money and effort into valorising the team and its history ahead of even its most legendary players. This is something political parties wishing to maximise their election prospects need to emulate.