3 | Myth and History

The tradition concerning the birth of the Yi is intertwined with the myths of origin of Chinese civilization. According to the traditional narrative, the book came into being through the insights of three legendary sages, figures belonging to a liminal space between myth and history. The first author is a fully mythical being, Fuxi, the first emperor, sometimes represented with a serpent body and a human torso. The third one, who is supposed to have carried the work to completion, is a fully historical person, although surrounded by a legendary aura: Confucius, the “master of ten thousand generations.” Between them stands the man who is considered the principal author of the book, a figure straddling history and legend: King Wen, the founder of the Zhou dynasty, which ruled China during most of the first millennium BCE, the time when the Yi actually came into use.

This illustrious genealogy had considerable cultural and political relevance. When the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) engaged in consolidating the empire by culturally unifying the diverse peoples they were ruling, milestones of the imperial policy were the standardization of writing and the ideological unification of the administration by elevating Confucianism to the rank of official doctrine of the empire. An important step of this program was the canonization of five ancient texts, first and foremost among them the Yi, as jing, classics, i.e. basic reference works for the whole culture. These books thereby acquired a status comparable to that of religious scriptures: they were commented upon and elaborated by scholars of later generations, but their authority and their sacred origins were never questioned over the next 2,000 years.

Contrary to the views of modern scholarship, in the traditional account of the origins of the Yi the book developed in a logical progression from trigrams to hexagrams to oracular texts and hermeneutic commentaries. The invention of the trigrams is attributed to Fuxi. The Great Treatise describes this discovery in the following way:

When in early antiquity Baoxi ruled the world, he looked upward and contemplated the images in the heavens; he looked downward and contemplated the forms on earth. He contemplated the patterns on the fur of animals and on the feathers of birds, as well as their adaptation to their habitats. He proceeded directly from himself and indirectly from objects. Thus he invented the eight trigrams in order to enter into connection with the divine light’s actualizing-dao and to classify the nature of the myriad beings.16

Fuxi is not here a mythical being with a serpent body, but the first civilizing hero, the one who introduced culture into the natural world. He is called by his appellative Baoxi, variously interpreted as Hunter, Tamer of animals and Cook, and a bit later in the same text we are told that

he made knotted cords and used them for nets and baskets in hunting and fishing.

Significantly the invention of the trigrams is connected here with “classifying the nature of the myriad beings.” The word “classify,” lei, has both the connotation of distinguishing and subdividing into rational categories (the beginning of the work of reason) and that of establishing connections and correlations between things on different planes. The eight trigrams are therefore fundamental cosmological categories embracing the totality of “heaven and earth”: as we shall see, they define radii in a Universal Compass, a map embracing concepts belonging to entirely different realms, yet mirroring each other through a web of subtle interconnections (see Chapter 4, Correlative Thinking).

The tradition is somewhat ambiguous about whether Fuxi discovered just the eight trigrams or the 64 hexagrams (the old texts often speak inter changeably of both, and the same word, gua, refers to both). But generally the invention of the hexagrams, as well as the authorship of the basic oracular texts, is attributed to King Wen, the founder of the Zhou dynasty. We find two brief allusions to the circumstances of such invention in the Great Treatise:

The Yi came in use in the period of middle antiquity. Those who composed the Yi had great care and sorrow.

The time at which the Yi came to the fore was that in which the house of Yin came to an end and the house of Zhou was rising, that is, the time when King Wen and the tyrant Di Xin were pitted against each other.17

“Those who composed the Yi” are King Wen and his son, the Duke of Zhou. Usually the texts of the Tuan Zhuan (Image of the Situation and main text of the Transforming Lines in the Eranos Yijing) are attributed to King Wen and the texts of the Xiang Zhuan (Patterns of Wisdom and Comments on the Transforming Lines in the Eranos Yijing) to the Duke of Zhou. The “house of Yin” is the Shang dynasty, which ruled over most of China from 1765 to 1123 BCE.

Sima Qian (145–86 BCE), the first historiographer of the empire, attempts a more detailed account of the genealogy of the Yi in his Shiji, Records of the Historian:

The ancients said that Fuxi, who was simple and sincere, built the eight trigrams of the Yi.

When the Count of the West was imprisoned at Youli, he probably developed the eight trigrams into 64 hexagrams.

King Wen, imprisoned at Youli, developed the Zhouyi.

At the end of his life, Confucius, who loved the Yijing, set in order the Tuan, the Xiang, the Xici, the Shuogua and the Wenyen [the first eight Wings].18

King Wen‘s legend is as follows. The Zhou were originally one of the nomadic tribes roaming the Western border areas of the Shang empire, particularly the Shanxi, the passes located on the Bronze Road, connecting China with the steppes of Central Asia (the same way of communication that became many centuries later the Silk Road). Recruited as military allies, they became vassals of the empire and settled in the plains at the foot of Mount Qi, the “Twin-peaked Mountain.” They became sedentary, and their wealth and power gradually increased due to the cultivation of millet, improved husbandry and commerce with the neighboring empire.

Around the middle of the 12th century BCE the fortunes of the Shang dynasty were declining, while the star of the Zhou was steadily ascending. The emperor Di Yi, worried about the growing power of his Western neighbors, tried to bind them to his house by giving in marriage his three daughters to the crownprince of the Zhou, Chang, “the Shining.” Shortly after that, Chang ascended to the throne of the Zhou, and Di Yi was succeeded by his son Di Xin.

Chang’s rule was a model of wisdom, while Di Xin “disobeyed heaven and tortured the beings.”19The luminous example of his Western neighbor was odious to the tyrant, who had Chang arrested and thrown into a walled cave. In the darkness of this confinement, Chang spent seven years meditating on the “great care and sorrow” of the current state of human affairs and on how to bring them back into alignment with “divine actualizing-dao.”

He is the one posterity remembers as King Wen: a meaningful name, which defines him as another fundamental civilizing hero. Indeed wen means both pattern of wood, stone or animal fur and language, civilization, culture, literature, the written symbol as revelation of the intrinsic nature of things. It is a fitting description of the “classification of the nature of the myriad beings” initiated by Fuxi through the eight trigrams and perfected by the “Pattern King” in his dungeon. In his meditations he started from Fuxi’s eight trigrams and developed the system further by pairing them into hexagrams and appending a text to each hexagram as well as to each individual line. These texts, constituting the Tuan, the first two Wings, were later expanded by King Wen’s second son, the Duke of Zhou, who added his own commentary (the Xiang, Third and Fourth Wing) to elucidate his father’s words.

Finally to Confucius (551–479 BCE) the tradition attributes the authorship of all the remaining commentaries, particularly of the Great Treatise. Thus the authority of the Classic of Classics was solidly founded and firmly meshed with the ideology of the empire; and the Confucian interpretation, occasionally incorporating insights of other schools, became the canonical reading of the Yi.

MODERN VIEWS OF THE ORIGINS OF THE YI

Modern scholarship tells a very different story about the origins of the Yi. In this reconstruction the book does not emerge from the philosophical reflections of a few individual sages, but from the divinatory practices of many generations of shamans. The texts did not come at a later date as elucidation of the patterns of lines, but the other way around: divinatory statements came first, and they were later compiled and classified through a symbolic system (or a number of symbolic systems), which eventually evolved into the patterns of lines of the Yi.

The first discovery of jiaguwen, divinatory inscriptions on tortoise shells and cattle bones, dates from a little over a century ago (1899). It has been described as the most important finding in modern Chinese historiography. These inscriptions are an almost daily record of all kinds of natural and social events of the Shang (1765–1123 BCE) and early Zhou dynasty. They constitute a vast reservoir of information, which is still far from being completely interpreted and classified. In 1995 Wang Dongliang cited 160,000 pieces identified, from which a repertory of 4,500 words had been compiled, not even half of them deciphered.20

The practice which generated these inscriptions was a form of pyromancy, divination by fire. The Shang shamans applied heat through glowing hard wood rods to specific points of animal bones (particularly shoulder blades of bovines) or tortoise shells, and in a state of trance read the patterns of cracks thus produced as messages from the world of gods and spirits. The resulting oracular statements were often recorded in abbreviated form on the bones or shells themselves, and these physical supports were kept for future reference, eventually constituting real divinatory archives.

As far as the Yi is concerned, the essential problem historians are confronted with is how this vast collection of disparate statements having to do with specific times and circumstances evolved into a well-organized book, with a universal system of signs and corresponding oracular texts applicable to all situations. A final answer will have to wait for a more thorough understanding of the available material and maybe also for future discoveries. But the existing evidence is sufficient for tracing at least some hypothetical lines of development.

Léon Vandermeersch has proposed an evolution marked by three stages: cattle bone divination, tortoise divination and yarrow stalk divination.

Originally divination may have been an occasional practice accompanying the offering of sacrifices. Cracks spontaneously produced by fire in the bones of sacrificial victims were read as indications of the acceptance or rejection of the offering by gods and spirits, and therefore of success or failure of specific enter -prises. Human concern about the future eventually brought about a reversal of the roles of the sacrifice and the ensuing divination: from an accessory quest, the pyromantic interrogation of the victim’s bones became the main goal of the process and the sacrifice only a means to that end.

That shift in emphasis brought about the transition from the so-called protoscapulomancy to scapulomancy proper. It was a shift in meaning and in technique. Pyromantic cracks started being understood as images of trans -formation processes in a larger context of universal movements; and shamans no longer confined themselves to simply reading what the sacrificial fire had left for them to read, but started preparing the bones in specific ways in order to obtain clearer pyromantic patterns. With the emergence of the divinatory purpose as primary, a significant attitude change took place, a shift from an original transcendent religious orientation to an immanent “divinatory rationalism”:

The work of fire happening through the diviner’s ember rather than on the priest’s altar favors the representation of an immanent dynamism over the representation of a transcendent divine will. Literally as well as metaphorically, divination moves away from the altar.21

This shift was further emphasized by the tortoise shell replacing the bovine scapula as the medium par excellence of pyromantic divination. This “great progress in divinatory thought,” writes Vandermeersch, went hand in hand with “the development of symbolic thought.” Indeed in China the tortoise is a powerful cosmological symbol, with its round back representing the heavenly vault, its flat square ventral shell the earth and the soft flesh of the animal the human world between heaven and earth. The adoption of the tortoise shell as support for divination therefore mirrored the intent of viewing the single incidents of individual consultations in the context of a larger cosmological frame: divination no longer revealed the will of the gods, but the subtle laws of transformation of the cosmic dynamism.

It was at this stage that divinatory records started being collected in archives of inscribed tortoise shells. And with this development the oracular formulas started taking on a life of their own, increasingly independent from the circum -stances of the original consultation. They gradually assumed a more stereotyped form and were eventually collected in divination manuals, the ultimate example of which is the Yi.

Classic texts talk about yarrow divination and tortoise divination as two parallel techniques, and occasionally discuss how their responses are to be integrated when both are applied to the same query. The archeological evidence is insufficient to definitely decide whether there was filiation of the yarrow technique from the tortoise one. But Vandermeersch claims that there is good reason to think so. One of the arguments in favor of this view is an etymological one: the radical of the character gua, “hexagram” or “trigram,” is the “reclining T” which is thought to depict a tortoise shell crack. And the same is true for the words zhan and zhen, both meaning “to divine” and referring to yarrow divination and to tortoise divination without distinction.

According to tradition, the yarrow stalk consultation procedure was invented by a diviner of the early Zhou dynasty, a historical person about whom we know very little, called Wu Xian, the Conjoining Shaman. His name, once again, is meaningful, since his technique created a bridge between the wild oracular statements of the ancient shamans and the rational philosophy of yin and yang. About this invention Vandermeersch writes:

Ancient Chinese historians did not know that trigrams and hexagrams, as we know them, did not exist under the Shang-Yin; thus they thought that Wu Xian invented a random procedure to select a gua. Now we know that gua are much more recent, and we understand that what Wu Xian invented was a random procedure for the selection of a [standardized] set of tortoise shell cracks.22

In fact, a common pattern in the bone and tortoise shell inscriptions are columns of strange signs, vaguely reminiscent of hexagrams (although the number of lines is not necessarily six). The “line” signs belong to only a few types, which have been identified as numbers written in paleographic form. Some numbers, e.g. 1, 5, 6, 7 and 8, recur with particular frequency. We do not know what these numbers refer to, but a plausible guess is that they are codes for specific types of cracks. Indeed actual cracks were also often vertically aligned (we must remember that in mature scapulomancy shells and bones were prepared so that they would crack at specific points). And these coded crack configurations may well have been associated with standard oracular responses.

Once the tortoise oracle had developed this abstract symbolic form, it was no longer necessary to engage in the cumbersome ritual of pyromancy. Any random procedure to select one of the coded configurations (and the associated divinatory formulas) would do. Very naturally then at this stage the yarrow stalk procedure came into play as a simplified method to achieve the same results as standardized scapulomancy.

EVOLUTION OF DIVINATORY TECHNIQUES IN ANCIENT CHINA23

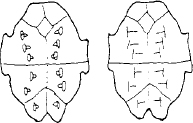

Neolithic proto-scapulomancy

• crude burning of unprepared omoplates (left)

• irregular star-shaped cracks on the other side (right)

Yin epoch scapulomancy

(14th to 11th century BCE)

• use of tortoise ventral plates

• preparation by incision before burning

• standardized “reclining T” cracks on the other side (right)

Proto-achilleomancy

(end of Yin—beginning of Zhou epoch, 11th to 10th century BCE)

• fragment of tortoise shell with numerical hexagrams; the numbers represent canonical types of cracks, selected by a random procedure

Numerical achilleomancy

(middle of the 1st millennium BCE)

• rationalization of the number system used in the numerical hexagrams

Canonical achilleomancy

(end of the 1st millennium BCE)

• algorithmic hexagrams made of odd-valued Yang monograms and even-valued Yin monograms

To obtain the Yijing divination system as we know it, only two more steps were needed:

• reducing the types of lines/cracks to four, coded by the numbers 6, 7, 8 and 9, and associating the even or odd character of the number with the philosophical notions of yin and yang;

• standardizing the number of lines/cracks at six.

Quoting Vandermeersch once again:

We can follow the great developmental phases of Chinese divinatory techniques from Neolithic proto-scapulomancy, based on the crude burning of residual bones of bovine holocausts, to the system of the Yijing. These phases are: first, the remarkable standardization of scapulomantic diagrams; then, the typological classification of these standardized forms; finally, the algorithmic coding of the system in terms of even and odd numbers. Throughout this process the same logic operates: it is a logic of rationalization of the formal structures of the diagrammatic, numerical or algorithmic configurations produced by divinatory techniques, taken as coded representations of the hidden cosmic connections existent between all phenomena in the universe. As Granet noted so well, Chinese thought works according to a logic of correspondences. The history of divination is an admirable illustration of how this logic works . . .24

The Book of Encompassing Versatility

The Yi did not therefore arise as a complete book, but evolved through many centuries. From one of a number of divinatory manuals, it eventually became not only the oracular book par excellence, but the Classic of Change, the ultimate reference of Chinese wisdom, revered by all philosophical schools.

Initially, there were archives of inscribed bones and tortoise shells, kept in order to record key events and to evaluate the accuracy of the corresponding predictions. Eventually these pieces were grouped and classified, and their inscriptions formed the material of the first divinatory manuals.

The simpler yarrow consultation method gradually replaced the pyromantic practices, and the recourse to the tortoise shell was reserved for special occasions and very important people. In the Zhou Li, Rites of the Zhou, the word yi denotes the science of yarrow divination, and three yi manuals are mentioned, all based on eight trigrams and 64 hexagrams, associated with the three mythical/ historical dynasties (Xia, 2207–1766 BCE; Shang, 1765–1123 BCE; Zhou, 1122–256 BCE). The last of these manuals is the Zhouyi, whose title can be translated as “Changes of the Zhou,” but also as “Encompassing Changes,” or “Encompassing Versatility,” since the name of the Zhou dynasty means, among other things, “a complete circle, from all sides, universal, encompassing;” and yi means, beside “change,” “easy, simple, versatile.” We have no idea of what that Zhouyi was like, but it is highly probable that it is the ancestor of the Zhouyi that has come down to us.

In 771 BCE, the Zhou capital moved East to Luoyang. That date marks the end of the Western Zhou and the beginning of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771–256 BCE), which saw a progressive weakening of the central power and a general destabilization of the social system. The emperor remained nominally master of the whole country, but in practice rebellious feudatories exerted their power independently of the central government and set up autonomous states warring with each other everywhere. It was a time of great yi, of great upheavals and insecurity, in which individuals were often at the mercy of unpredictable changes. The Huainanzi, an early Han philosophical treatise, gives an impressive description of the final chaotic phase of the Eastern Zhou, the Warring States period (403–256 BCE):

In the later generations, the Seven States set up clan differences. The feudal lords codified their own laws, and each differed in his practices and customs. The Vertical and Horizontal Alliances divided them, raising armies and attacking one another. When they laid siege to cities, they slaughtered mercilessly . . . They dug up burial mounds and scattered the bones of the dead. They built more powerful war chariots and higher defense ramparts. They dispensed with the principles of war and were conversant with the road of death, clashed with mighty foes and ravaged without measure. Out of a hundred soldiers who advanced, only one would return . . .25

We can imagine that in these circumstances, in which traditional values were overrun by violence, and choice could be a matter of life or death, recourse to the oracle may have often been a key resource. The Huainanzi says that at that time “the tortoise had holes bored in its shell until it had no undershell left, and the divining stalks were cast day after day.”

Already during the first part of the Eastern Zhou epoch, the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BCE), the use of the Yi had moved outside the environment of the courts of high-ranking nobility and had reached a much larger class of consultants, principally consisting of the scholars-officials who were the backbone of the Chinese social system. This shift in users changed the scope of yarrow divination, expanding it beyond the limits of state affairs to include private and existential matters. And with this, also a change in emphasis and interpretation took place, in which ethical concerns acquired a much greater weight. The notion of an ideal user of the book started developing: the junzi, the noble, became the “disciple of wisdom,” the person who in a consultation does not only seek a personal advantage, but the realization of an intrinsic good, the actualization of dao in action.

The following consultation, related in the Zuo Zhuan, a history of the Spring and Autumn Period, is an interesting testimony of this new ethical concern:

In 530 BCE [the feudatory] Nan-kuai plots a rebellion against his ruler. Consulting the Yijing, he obtains the fifth line statement of hexagram 2, Kun, which reads “Yellow skirt, primally auspicious.”26 Greatly encouraged, he shows this to a friend, without mentioning his intentions. The friend replies: “I have studied this. If it is a matter of loyalty and fidelity, then it is possible. If not, it will certainly be defeated . . . If there is some deficiency [regarding these virtues], although the stalkcasting says “auspicious,” it is not.”27 Thus Nan-kuai’s improper purpose renders his whole prog -nostication invalid. His friend’s fundamental assumption is that an act’s moral qualities determine its consequences . . . Only something that is already moral can ever be “auspicious.” Here we see how developments in sixth-century moral-cosmological thinking change not only the interpretation of a particular line statement of the I, but also the very tasks to which the text could be directed. (Nan-kuai, by the way, disregards his friend’s warning, and within a year he is dead.)28

This ethical approach to the Yi was particularly emphasized in the Confucian school. As we have mentioned, the tradition attributes to Confucius (551–479 BCE) all the essential commentaries to the Yi. This claim is almost certainly a fabrication of later Confucian scholars. But Confucius may very well have been deeply interested in the Yi—since he was very interested in the ancient culture in general and his country of Lu was an important repository of the traditions of the Zhou. Many anecdotes are told about his devotion to the Yi. Sima Qian, e.g., says that Confucius so much perused his copy of the Yi that he had to replace the bindings of the bamboo strips three times (books at that time consisted of thin bamboo strips tied together).

The only explicit reference to the Yi in the works of Confucius is a quotation of the third line of hexagram 32, Persevering:

The Master said: “The people of the South have a saying: he who does not persevere cannot be a diviner nor a physician. How well said! He who does not persevere in virtue receives embarrassment and shame.”29The Master said: “Nevertheless, I do not practice divination.”30

These words possibly hint at what may have been Confucius’ real contribution to Yi scholarship: a reading of the texts valuing their ethical and educational function over the oracular aspect. This is well in accord with a note contained in the so-called yi shu, “lost texts,” of the Mawangdui silk manuscript (see p. 48, The Mawangdui manuscript):

Confucius loved the Yi in his old age. At home, he had it on his bedside table; while traveling, he had it in his bag. Zi Gong asked him: “Master, do you also believe in yarrow divination?” Confucius answered: “It is the word of the ancients: I am not interested in its use, I enjoy its texts . . . I observe the ethical meaning . . . Between the divining scribes and me, it is the same path, but traveled to different destinations.”31

If such is indeed the case, then Confucius must have contributed to shape the new approach to the Yi which fully emerged a few centuries later, under the Han, when the Yi became a book to be read and pondered, rather than consulted; from a manual of divination it turned into a summa of the wisdom of the ancients and a general map of the cosmos.

The feudal strife of the Eastern Zhou period came to an end in the last decades of the third century BCE, when the Qin dynasty (221–207 BCE) rose to power and brought the whole country under a single unified administration, building “a centralized state wielding unprecedented power, controlling vast resources and displaying a magnificence which inspired both awe and dread among its subjects.”32

The rule of the Qin was short lived, but marked a great turning point in Chinese history. When it collapsed, it left to the Han (206 BCE – 220 CE) an important legacy: the idea of empire and the governmental structure to embody it. “For almost four centuries under the Han the implications of this great fact were to work their way out in all aspects of Chinese life . . . [a process that] in several fundamental respects shaped the intellectual tradition of China until modern times, and not of China only but of Korea and Japan as well.”33

The Han worked gradually to rebuild the great web of central government that had disintegrated with the fall of the Qin, unifying, organizing and standardizing the vast area and the diverse peoples under their control. A central aspect of this unification was the establishment of a common Chinese cultural identity, which in its general outlines was to last for the next 2,000 years.

An important step was the standardization of the written language. Even today in China a variety of local dialects are spoken, in which words have widely differing sounds (beside that, the same sound in Chinese corresponds to many different words). People belonging to faraway regions do not necessarily under -stand each other when they speak. But they do understand each other when they write. The ideographic language creates a bridge between them and allows them to recognize each other as belonging to a common cultural mold.

Confucian thought played a leading part in the Han unification of culture. Parallel with the expanding function of government, there was a broadening of intellectual interest and a growing concern with questions of cosmology and the natural order. It was the conviction of Han philosophers that when the government was in tune with the laws of Heaven prosperity resulted, while strife and famine prevailed if that was not the case. Equally important, in an agricultural society, was the attunement to the concerns of the Earth (irrigation, land usage, flood control and so on); and so the notion of a necessary harmony between Heaven, Earth and Man became a pivotal idea in Chinese thought.

The great Han design of organizing all knowledge into a coherent whole including the natural world and human society was therefore, beside an intellectual pursuit, an important political task. Confucianism, with its emphasis on traditional wisdom and its focus on perfecting human nature through rites, music and literature, was ideally suited to this task. The final product of the Confucian education was the scholar/sage, the learned man endowed with a refined moral sense, whose natural field of action was in government service. During the Han this class of scholarly officials grew to a position of dominance over the entire social system, replacing the feudal aristocracy of former times. Public service was based on a system of competitive examinations which, in times of peace at least, assured the dominant position of the scholars in the bureaucracy.

A central endeavor in this process of cultural unification was the canonization of the books which were to constitute the base of all learning and particularly of the public examination system. To this effect two great gatherings of Confucian scholars were held at the presence of the emperor himself, the last one in 79 CE in a hall of the imperial palace in Luoyang called “the White Tiger Hall.” The results were compiled and published in a book called Baihu Tong, Discussions in the White Tiger Hall, establishing the orthodox interpretation of the five jing, the classics, and setting the base of a vast system of correlative thinking (see Chapter 4, Correlative Thinking).

The Yijing, or Book of Changes, complete with its Ten Wings, was the first of the classics, and was taken as a description of the metaphysical structure of the whole of “heaven and earth.” The other four classics were: the Shujing, Book of Documents, recording the experience and wisdom of the “earlier kings,” model for all later rulers; the Shijing, Book of Songs, repository of a tradition of folk songs and ceremonial hymns; the Liji, Book of Rites, the ultimate authority in matters of procedure and etiquette; and the Lüshi Chunqiu, the Spring and Autumn Annals, a collection of moral and political lessons in the guise of historical narrative.

From this time onward, the influence of the Yijing on Chinese culture kept growing. As the first of the classics, it was no longer just a book of divination: it was a tool for structuring thought in all fields, a standard reference for any theory claiming authority. Its influence extended into philosophy, ethics, politics, medicine and esthetics. And, since the openness of its texts allowed many different interpretations, the concise and cryptic oracular core of the book became enveloped in a body of scholarly commentaries.

Philosophical and oracular tradition

The philosophical reflection on the Book of Yi culminated in the vast and elaborate exegetic work of the Neo-Confucian school during the Sung dynasty (960–1279). But meanwhile the divinatory use of the book was never lost. And with it survived an oracular tradition much closer to the shamanic origins of the Yi. This approach surfaced in a particularly clear form with the 16th-century philosopher Lai Zhide.

Lai claimed that the Neo-Confucian school, by focusing exclusively on the discursive meaning of the texts and on their implications for “moral principle,” had lost sight of the images, which were the true soul of the book. The Book of Yi, said Lai, consists essentially of pre-verbal symbols, its texts are verbalizations of intuitively perceived images. And it can reproduce the natural order of things because it has been generated spontaneously, just like natural phenomena. “The sages,” Lai wrote, “did not apply their minds to set it forth.”

Therefore these texts, unlike those of the other classics, have no concrete referents. They do not point to any fact or principle, and they cannot be taken as a “definitive outline” of moral action. They acquire a specific meaning only when they answer a specific question, in a concrete life situation.

Lai saw this openness of the Yijing texts as closely connected with the all-encompassing nature of the oracle. The Xici claims that the Yi embraces the totality of heaven and earth. But, if each line in the book corresponded to a single occurrence, 384 lines would account for only 384 occurrences. How then, Lai argued, could the Yi “be the one and all of heaven and earth”?34

The oracular and the commentary texts of the Ten Wings were finally collected in a canonical form in the Palace Edition of the Yijing by the emperor Kangxi in 1715. That edition became the standard reference for all later Chinese publications, and is the text on which the present translation is based.

In 1973 silk manuscripts, including a version of the Yi and one of the Laozi, were found in a Han tomb dated 168 BCE. It was a crucial discovery, affording insights into the evolution of those great works at a date far antecedent to anything available up to that point.

The Mawangdui text of the Yi differs from the canonical one (the Palace Edition) in a number of interesting ways.

First of all, the graphic representation of the hexagrams is different, having ![]() and

and ![]() in place of the whole and the opened line. These are variations on the paleographic form of the numbers seven and eight—and at the same time they are remarkably similar to the final form (

in place of the whole and the opened line. These are variations on the paleographic form of the numbers seven and eight—and at the same time they are remarkably similar to the final form ( ![]() and

and ![]() ) of the whole

) of the whole

and the opened line. Therefore we can regard the Mawangdui hexagrams as a bridge, a kind of “missing link,” between the numeric “proto-hexagrams” recorded on tortoise shells and oracle bones and the canonical hexagrams.

Second, the names of 35 out of 64 hexagrams are different, in spite of the fact that overall the oracular texts are remarkably similar to the canonical version.

Third, the order of the hexagrams is different. The Mawangdui order is a systematic sequence obtained by keeping the upper trigram fixed and varying the lower trigram according to a regular rotation. In this way it resembles much more the order of a hexagram table than that of the canonical book. Wang Dongliang35interprets this fact as an indication that, at the time of the Mawangdui manuscript, divination was still the prevailing use of the Yi and philosophical speculation was not yet the dominant mode. The canonical sequence is “philosophical” in the sense of reflecting a developmental process in which the principles of the cosmos and of the human world are derived from each other according to an internal logic not directly connected with the structure of the signs. The Mawangdui sequence, on the other hand, with its logical arrangement based on the structure of the signs, seems to have the eminently pragmatic purpose of facilitating the search for a given hexagram, i.e. it seems to be tailored to the needs of yarrow stalk consultation.

Finally, the Mawangdui text consists basically of only two sections, corresponding to the Tuan (i.e. the Image of the Situation and the main text of the Transforming Lines) and to the Xici, the Additional Texts. Therefore the classic organization of the book in Ten Wings must not have been yet in existence at that time. Instead of the remaining eight Wings, the Mawangdui manuscript includes an assortment of commentaries in the form of dialogues between Confucius and his disciples (conventionally called yishu, “lost texts.”).

The first glimpses of the Yijing reached the West by way of Jesuit missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries. Some of these missionaries had a keen interest in the spirit of the Chinese people they had come to convert, deeply studied their culture and tried to approach them on their philosophical terms, frequently incurring the wrath of the Vatican. One of them, Matteo Ricci, is still remembered in the name of an outstanding contemporary sinological institute.

The early Jesuit missionaries brought to Europe fragments of the Classic of Classics; complete translations came only in the 19th century. And it was still a missionary, the German Richard Wilhelm, who finally introduced the Yijing to the West in a way that won the minds and souls of intellectuals, and eventually also those of a large public of readers and users.

Wilhelm‘s translation was published in Jena in 1923. It stands out from all previous ones for a radically different attitude toward the Yijing. Wilhelm regarded it as a book of spiritual guidance of universal value. He wrote in his preface:

After the Chinese revolution [of 1911], when Tsingtao became the residence of a number of the most eminent scholars of the old school, I met among them my honored teacher Lao Nai-hsüan. I am indebted to him . . . also because he first opened my mind to the wonders of the Book of Changes.36

Wilhelm not only steeped himself in Neo-Confucian philosophy, but took it on as a personal spiritual path; and, having first traveled to the East as a missionary of Western religion, eventually he came back to the West as a missionary of Eastern wisdom. His translation moves from this committed and participatory stance. He endeavored to make the ancient book accessible to the Western mind by translating it as a discursive text in a Neo-Confucian philosophical perspective. His translation is remarkably readable, poetic and profound.

Carl Gustav Jung was deeply struck by the “formidable psychological system” the book embodied, and he wrote a foreword for it, which no doubt contributed considerably to its popularity. He also asked Cary F. Baynes, an American student of analytical psychology in Zurich, to undertake an English rendering of Wilhelm’s German translation. The English translation took quite some time to complete (meanwhile Richard Wilhelm had died in 1930). When the Wilhelm– Baynes translation was published in the Bollingen Series in 1950, it rapidly caught the attention of a large audience.

Since then the Yijing has become popular in the West, and numerous translations and commentaries have been published, at all levels of quality and depth (see Bibliography). Many of the works by Westerners are translations of previous translations, quite a few of them of Wilhelm’s classic translation.

The present translation originates from the lifelong work of Rudolf Ritsema and from the experiences of the Eranos circle, an East–West research center founded in 1933 in Ascona, Switzerland, by an extraordinarily energetic and intuitive Dutch woman, Olga Froebe-Kapteyn (1881–1962).

Olga Froebe née Kapteyn was born in 1881 in London to Dutch parents. Her mother was a feminist, an anarchist and a friend of prince Kropotkin. Her father, Albert Kapteyn, was the only one in his family doing poorly at school: one of his brothers became a famous astronomer, another a mathematician. Albert was destined to become an apprentice in the village bicycle repair shop. But he managed to convince his father to send him to the Zurich Institute of Technology (ETH) and eventually became an engineer and inventor. He patented a braking system for trains and became director of the British Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company.

A strong and independent woman, Olga was intensely interested in Eastern spirituality and in the 1920s joined the circle of remarkable people that had gathered around Count Hermann Keyserling’s School of Wisdom in Darmstadt, Germany. The School of Wisdom intended to promote a planetary culture, beyond nationalism and cultural ethnocentrism, recognizing the equal value of non-Western cultures and philosophies. It counted among its members C. G. Jung, Richard Wilhelm, Rabindranath Tagore, and Hermann Hesse.

Jung, Wilhelm, and the theologian Rudolf Otto particularly influenced Olga’s development. From Otto, Olga learned to conceive religion as a universal drive of the human soul, independent from any institutional form and centered on the sense of an invisible order underlying the apparent randomness of life events. In Jung’s notion of “archetype” she found a way to articulate her spiritual intuitions in psychological language. And in the Yijing, which in 1923 Richard Wilhelm presented to the School of Wisdom in his German translation shortly before publication, she found a bridge connecting the transpersonal archetypal dimension with daily life.

In 1920 Olga’s father bought Casa Gabriella, an old house surrounded by a garden in Ascona, in the Canton Ticino, the Italian speaking part of Switzerland, and gave it to his daughter.37The house was wonderfully situated on the shore of Lago Maggiore, combining the mild climate of the lake with the austere beauty of the surrounding Alps; and Ascona had been, since the beginning of the century, a cauldron of innovative existential, artistic and political movements arising at the meeting point of Central European culture with the Mediterranean world.

In 1928, following a still rather undefined hunch, Olga had a meeting hall, later to be known as the Eranos Sala, built at the Western end of the Casa Gabriella grounds. Gradually she conceived the idea of turning her house into a center for the spiritual meeting of East and West.

In 1932 Olga sought Otto’s support for her project. He was too ill at the time to get personally involved, but he suggested the name “Eranos” for the project, a Greek word denoting a feast to which each participant brings a contribution. Richard Wilhelm had died two years earlier, so of her three mentors only Jung was left. But Jung made himself available and became a crucial formative influence in Olga’s project. For two decades he gave a great personal and intellectual contribution to Eranos, regularly sojourning there every year and presenting many of his crucial ideas at the “work in progress” stage. His notion of archetypes provided an overarching conceptual frame for the interdisciplinary conversations that developed at Eranos among scholars in the fields of science, religion, psychology, esoteric traditions and symbolism.

Both Jung and Olga were deeply involved in the practice of the Yijing. From the beginning Olga wished to introduce the experiential dimension of Yijing consultation in the Eranos sessions. Her vision for Eranos was that of an experiential laboratory for spiritual growth, and in fact the titles of the first Eranos sessions reveal her preoccupation with spiritual practice and personal develop -ment: Yoga and Meditation in East and West (1933), Eastern and Western Symbolism and Spiritual Guidance (1934), Spiritual Guidance in West and East (1935). In 1934 she suggested to Jung to include the work with the Yijing in the Eranos sessions. But Jung felt that the time was not ripe for such an “unsavory” personal exposure, even within the intimate circle of Eranos. It was much better, he suggested, to focus on the scientific study of archetypal images and of the religious phenomenon in the sense of Rudolf Otto.38

Thus the Yijing remained an underground thread throughout the develop -ment of Eranos over the next 50 years. Sharing a strong involvement in that thread sparked an immediate sense of recognition between Olga and Rudolf Ritsema when they first met in 1948.

Rudolf Ritsema was born in Velp, the Netherlands, in 1918. His mother, Frances Johanna Van der Berg, had a deep and natural religiosity and was involved in theosophy and Indian philosophy. From her Rudolf inherited a sense of “being carried by God in life.” His father, Ipo Christiaan Ritsema, was a chemist, a lover of nature and the arts, and a very rational man. From him Rudolf got his interest in nature, biology and history.

The marriage of Ipo and Frances Johanna was not a happy one, and the constant conflicts in the home had a devastating effect on Rudolf, who was a sensitive, nervous child. Therefore at the age of 11, on the advice of a psychologist, he was sent to the Odenwaldschule, an avant-garde boarding school in Heppenheim, in the German Odenwald, to be away from the turmoil at home. The Odenwaldschule turned out to be his salvation, and gradually helped him to develop his self-assurance and social skills.

The school had been created in 1910 by a visionary couple, Paul and Edith Geheeb, based on the principles of “progressive education,” a pedagogic philosophy emphasizing experiential learning, critical thinking, group cooperation, social responsibility, co-education of the sexes and curricula tailored to the students’ personal goals. In 1934, with the ascent of Nazism, the Geheebs emigrated to Switzerland and re-founded the school with the name Ecole d’Humanité, first in Versoix, in the Canton Geneva, later in Lac Noir, in the Canton Freiburg. The school still exists and is located in Hasliberg, in the Berner Oberland.

In Versoix Rudolf met Catherine Gris, a young music teacher from Geneva. After receiving his baccalaureate he moved to Geneva and a strong bond developed between the two young people. They got married in 1945, and Catherine remained Rudolf’s faithful companion until his death in 2006.

Catherine and Rudolf shared a strong devotion to the Geheebs, and in March 1944 they rode their bicycles from Geneva to Lac Noir to visit them. There they re-encountered Alwina von Keller, whom they had met years before when she was an English literature teacher at the Odenwaldschule. In the intervening years Alwina von Keller had been in analysis first with Ernst Bernhard and then with Jung, and had become a Jungian analyst herself. At the time of Catherine and Rudolf’s visit she was in Lac Noir to do therapy with her friend Edith Geheeb, who was deeply affected by the distressing situation of the school. The financial difficulties brought about by the war had forced the school to downsize to a mountain hut, where the students, many of them traumatized Jewish children coming from Gurs and other concentration camps in France, lived in cramped quarters in very anguished conditions.

When Rudolf and Catherine arrived in Lac Noir, Edith Geheeb told Rudolf: “Go see Alwina, she has something you will find interesting.” The “something” was the Yijing in Wilhelm’s translation. Alwina described to Rudolf the use of the oracle as an introspective tool and as a complement to dreamwork. At that time Rudolf was in total darkness about the direction to give to his life. So he asked the oracle a very broad and fundamental question: “Who am I?”

Many years later, working with the Yijing at Eranos, I learned from Rudolf the importance of asking focused, practical and emotionally significant questions, rather than large, general and philosophical questions. Now, Rudolf’s first Yijing consultation certainly did not match that criterion. Still the answer he got was highly significant for him. The answer was hexagram 16, “Enthusiasm” in Wilhelm’s translation, with three moving lines, leading to hexagram 46, “Pushing Upward.” Rudolf immediately felt a strong resonance with this answer and recognized in it the excitement of the discovery that was happening for him.

Other aspects of that first answer gradually fell into place for him later, when he started studying classical Chinese to get into a more intimate contact with the oracular texts and his knowledge of the Yijing deepened. For example, he found that the Chinese characters in the second line of hexagram 16 suggest a “cuirass tending towards petrification.” He recognized in that image the defenses and the rigidity he had built up in his young years to protect his sensitivity. And the duke of Zhou’s commentary on that line, referring to a “correct use of the center,” felt to him like an invitation to rely on a protection more solid than an armor, having its source in the contact with the center of his being. But perhaps the most significant discovery was finding that a key meaning of the term Wilhelm translates as “enthusiasm” is “providing:” the Yijing provided him with a way to contact his inner guidance, and providing others with the same opportunity became Rudolf’s mission in life.

Yet, at the time of his first encounter with the oracle, hexagram 16 was still for him just “enthusiasm.” And his enthusiasm was so fiery that he wanted to immerse himself immediately in the study of the book. Edith Geheeb had a copy of it, and since the Yijing was at that time, in Switzerland, during the war, very difficult to find, Rudolf asked her to lend it to him. Edith consulted Alwina, who was a bit frightened by Rudolf’s exuberant enthusiasm. Alwina suggested a compromise: Edith could lend him the first volume for a week only.39

Rudolf returned to Geneva with the book and spent the whole week sitting at his typewriter day and night, typing it down. When later Alwina came to know about this, she realized that Rudolf’s enthusiasm was not a flash in the pan, and let him borrow the entire book for a longer time to complete his copying job.

The meeting in Lac Noir was for Rudolf the beginning of a lifelong love affair with the Yijing. He studied classical Chinese and had the good fortune to find in an antique shop the 1884 Samuel Wells Williams’ Chinese dictionary, which Catherine gave to him as a New Year’s gift in January 1945. In the University of Geneva library Rudolf could consult the French translation of the Yijing by Paul-Louis-Félix Philastre, which reproduces most of the original Chinese text. By studying it with the help of his new dictionary, he realized that the Chinese text has many more facets than those conveyed by Wilhelm’s neo-Confucian interpretation.

After the Lac Noir encounter, Rudolf and Catherine entered into analysis with Alwina. On May 8th, 1945, they got married. They had not planned any celebration, because during the war Rudolf had lost all contacts with his family in Holland and was very worried about them. But the celebration happened anyway, and on a large scale: that day Germany’s surrender was signed and the whole city of Geneva descended onto the streets to celebrate.

In April 1946 Catherine and Rudolf moved to Holland, where Rudolf found a job in the antiquarian department of the scholarly E.J. Brill bookshop and publishing house in Leyden. His job provided him with the exceptional opportunity to acquire rare sinological texts, and in fact in 1949, a few months before the fall of Beijing to Mao Zedong, he managed to obtain a copy of the canonical edition of the Yijing, the precious Palace Edition published by the emperor Kangxi in 1715, which Richard Wilhelm had vainly sought in China for years, before finding it in a friend’s library in Germany.

At the end of the summer of 1947 an unexpected event loaded with consequences took place in Rudolf’s life: he suffered an attack of poliomyelitis that paralyzed him up to the diaphragm and brought him to the brink of death. Fortunately his heart was not affected, but for months he was unable to walk, and Catherine, so much smaller and thinner than him, had to move him around. A neurologist prescribed he should spend the coldest part of the winter in a milder climate. He and Catherine decided to use that opportunity to visit Alwina in Switzerland and devote that time to their therapy.

Alwina lived now in Casa Shanti, a house Olga Froebe-Kapteyn had built at the eastern end of her property. She found Rudolf and Catherine a lodging and introduced the young couple to Olga. During the stay in Ascona Rudolf gradually recovered the use of his legs and at the end of the month he was able to walk on the road along the lakeshore for quite a distance, with frequent stops to rest.

Before leaving Ascona Catherine gave a concert for friends and neighbors. Olga, who was very much a music lover, was invited. At the end of the concert, remarking that the stairs of the house where they stayed were very difficult for Rudolf, she said: “Next year this poor young man, who walks with so much difficulty, can stay in the Casa Eranos apartment.” This was an apartment above the Eranos Sala that Olga had built for her guests, and it had been used first by Jung, then by Erich Neumann.

From that year on, every winter Catherine and Rudolf spent a month as Olga’s guests at Eranos. Every night they had dinner with Olga, and between the three a warm intimacy developed. The love of music connected Olga and Catherine, the shared deep interest in the Yijing created a strong bond between Olga and Rudolf. In those years Rudolf kept deepening his Yijing studies and started writing commentaries on the Yijing texts for Olga, for Edith and her students, and for Alwina and her patients. Thus he honed his skill in interpreting the oracular images as dreamlike images, bringing to light aspects of a situation that would normally elude conscious perception.

Olga repeatedly invited Rudolf to come to the Eranos meetings. But only in 1957 was he able to take an extra week off from his job to go to Eranos in the summer. In the following years he regularly attended the Tagungen (as the Eranos meetings were called) and, together with Olga and with the biologist Adolf Portmann, participated in the daily planning of the events.

Olga died in the spring of 1962. A few months before she had nominated Adolf Portmann and the Ritsemas as her successors in carrying on the work of Eranos. The Eranos Foundation was created, and Adolf Portmann became its first president. But he kept his chair at the University of Basel and kept living there. The day-to-day management of Eranos fell entirely on the shoulders of the Ritsemas.

Over the next 25 years they poured a great amount of energy and creativity into Eranos, just as Olga had done. The Eranos Tagungen continued along the lines developed by Olga and Jung, centered on fundamental archetypal research, and after the death of Adolf Portmann in 1982 Rudolf assumed the presidency of the Eranos Foundation.

The Eranos Round Table Sessions

Even though his Eranos duties absorbed him most of the time, Rudolf never really abandoned his Yijing studies. His research reached a turning point around 1970, when he grew dissatisfied with writing critical commentaries on the Wilhelm translation and conceived the idea of an entirely new translation—a translation that would avoid as much as possible any a priori interpretation and would allow the questioner a direct personal contact with the archetypal images.

This vast project took 20 years to complete. Various people helped in the beginning, particularly the Jungian analysts James Hillman and Robert Hinshaw. Toward the end of the 1980s the American writer Stephen Karcher helped Rudolf to carry the job to completion. Together they produced a first provisional version of what later came to be known as “the Eranos Yijing,” with the title Chou Yi: The Oracle of Encompassing Versatility.

Meanwhile, Eranos underwent an identity crisis. Rudolf felt that the old lecture format had become dry and academic and had lost touch with Olga’s original intention that Eranos should be a place of personal and spiritual transformation, not merely of intellectual debate. Due to Eranos’ glorious past, presenting at Eranos had become a showcase of academic prestige rather than a place of personal evolution.

Rudolf decided that a radical change of course was needed. At the Tagung of 1988 he announced that the phase of the work of Eranos that had begun in 1933 with Olga Froebe-Kapteyn and Jung had come to an end. In order to fulfill the spiritual function originally envisioned by its founder, Eranos had to enter a new phase. The new phase would put the I Ching at the center of the work of Eranos and introduce consulting the oracle in the Eranos sessions as a tool for personal transformation.

This announcement fell like a bomb among the Eranos speakers. A number of them refused to go along with the new format, and a few even started a separate branch of Eranos. But the Eranos sessions went on and took up an entirely new format.

Three or four small conferences per year (each with a maximum of 20–30 participants) replaced the traditional big conference held once a year in August. The work now took place around a large round table placed in the Eranos Sala, which gave these meetings the name of Eranos Round Table Sessions. Speakers and participants all sat around the table. Mornings were devoted to lectures and discussion (another innovation: the old lecture format did not include discussion) and the afternoons to Yijing consultations by both lecturers and participants.

In 1990 Rudolf, wanting to devote himself completely to the additional Eranos Yijing translations he had in mind, passed on the management of Eranos practical matters to Christa Robinson, a Jungian analyst from Zurich whose father had been Jung’s personal physician. In 1994 he also asked Christa to take over the presidency of the Eranos Foundation, a post she occupied until 2001.

The experience of the first Round Table Sessions in the early 1990s suggested various improvements to the provisional translation of the Chou Yi, leading to a revised version published by Element Books in 1994 under the title I Ching: The Classic Chinese Oracle of Change.40

In the same year I arrived at Eranos and started collaborating with Rudolf to create an Italian version of the Eranos Yijing, sponsored by the publishing house, Red Edizioni, from Como. Initially I assumed that my task would be simply to translate the existent Ritsema–Karcher English translation into Italian. But Rudolf promptly disabused me. He was adamant that all trans lations of the Yijing must be conducted on the original Chinese text. (In fact, in the following years two translations from the Element edition were done without his consent: one— paradoxically!—into his native Dutch, and one into Spanish. He always disowned those and considered them “fake.”) The Italian translation project then obviously took up a much larger dimension.

I felt attracted to the challenge of this translation, but quite naturally I consulted the Yijing about it. I got hexagram 39, called “Limping” in the Eranos Yijing (“Obstruction” in the Wilhelm translation). That sounded awful. Not to mention the fact that in Italian a “limping translation” is an idiomatic phrase for an inadequate translation . . . I called Rudolf to share with him the bad news: I thought we should cancel the project. But he was of a radically different opinion. He pointed out that hexagram 39 describes a situation “in which progress is hampered by obstacles and difficulties, and it is possible to proceed only haltingly”—but it is still possible to proceed! So proceed we must, in spite of the difficulties. What did I expect, that this translation would be a leisurely stroll? Well, no, we would limp through it, here we have our warning, but onward we must go. That was typically him. On his desk he had a quote of William of Orange, also known as William the Taciturn: ‘Point n’est besoin d’espérer pour entreprendre, ni de réussir pour persévérer.’41And his personal Chinese seal consisted of four characters: “not/fearing/long-term/enterprises.”

Thus in the summer of 1994 I moved to Eranos and Rudolf and I embarked on our “long-term enterprise.” For the next couple of years I spent most of my time there. The Ritsemas lived in the apartment above the Eranos Sala, the same they had occupied in their winter sojourns at Olga’s. I lived on the library floor of Casa Gabriella, above the apartment that was once Olga’s and was now occupied by Christa Robinson. I shared most meals with the Ritsemas, and a warm friendship developed with both of them. Gradually I started to regard Eranos as my home.

Rudolf and I spent every morning in our “Yijing studio” in the mansard of Casa Gabriella. It was a small space densely packed with books, dictionaries and piles of articles and notes. The most important working tool (after the precious Palace Edition of the Yijing and the much more modern, but equally fun -damental, Harvard–Yenching Concordance to the Yijing) was Rudolf’s “rolodeck,” an accordion-like contraption holding a large number of cards. Each card contained all the key information about a character occurring in the book. Because, remarkably, Rudolf’s painstaking analysis of each single character of the text had begun before the Information Age, and still carried the imprint of its time.

The rolodeck and its accessory card system allowed us to find all the recurrences of each Chinese character in the book and its entries in various Chinese-English and Chinese-French dictionaries. Taking into account the definitions of the character in those dictionaries and the Yijing contexts in which the character occurred, we looked for the most appropriate Italian core-word for it. After choosing the core-word, we would create a list of “associated meanings” enlarging the semantic field of the Italian term to embrace all the principal meanings of the Chinese character. It was a truly Carthusian job, but it was enlivened by the pleasure we had in working together. Even though Rudolf was by temperament a formal old-fashioned gentleman, in the Yijing mansard he would transform, and we would become kids playing together. We delighted in jokes, and the hours went by fast.

The Italian translation was published in 1996 under the title Eranos I Ching. Il libro della versatilità.42In the meantime I had started being involved in running the Round Table Sessions. At the Round Table, typically Rudolf, Christa and I would sit at the vertices of an equilateral triangle. The circle itself was like an alchemical cauldron for the change catalyzed by the oracle’s dreamlike images, and it was often touching to witness peoples’ process as they, as the Chinese would say, “rolled the oracle’s words in their heart.”

I remained at Eranos after the completion of the Italian translation. Rudolf and Catherine had become my family. In the following years, unfortunately, their health started deteriorating, but Rudolf did not give up his work on the Yijing. In 1997 the Swiss linguist Hansjakob Schneider joined him to produce a German translation, which was published in 2000 by Barth, Munich, under the title, Eranos Yi Jing. Das Buch der Wandlungen.43Then the French Jungian analyst Imelda Gaudissart and her husband Pierre, working under Rudolf’s supervision, completed a French version of the Eranos Yijing, published in 2003 by Encre, Paris, under the title, Le Yi Jing Eranos.44

The last step in Rudolf’s “work of a lifetime” consisted in revising the English translation of 1994. The work we had done together on the Italian translation had brought about many new insights that had been incorporated into the German and the French translation. It seemed natural to include those changes, together with the experience of a decade of Eranos Round Table Sessions, in a new English version of the Eranos Yijing. Most significantly, the spirit itself of the divinatory process had evolved from a future-oriented and more directive attitude to a present-oriented, non-directive, introspective and psychological approach, which was well reflected in the title Rudolf and I had adopted for our last Yijing seminars: Mirror of the Present. Therefore we prepared an English translation embodying this new spirit. The new English Eranos Yijing was published by Watkins, London, in 2005 under the title, The Original I Ching Oracle.45This, dear reader, is essentially the book you are holding in your hands, except, of course, for this new Introduction and a few textual corrections.

Rudolf died on May 8th, 2006, on the sixty-first anniversary of his wedding with Catherine, having well accomplished the task he had set himself after that first “Providing” hexagram obtained in 1944. Catherine followed him a year and a half later.

The vast sinological library of Rudolf Ritsema, which he bequeathed to me, is presently the Ritsema Fund,46housed in the Museo delle Culture of Lugano, Switzerland. The Fund includes the precious Palace Edition of the Yijing and such memorabilia as Rudolf’s rolodeck and his typed version of Wilhelm’s Yijing. The works are available for consultation to interested scholars,47and the Fund includes an interactive guide to Rudolf Ritsema’s life and work.