Tell me, also, if this agitation is regarding the emancipation of the Negroes or not.

—GIUSEPPE GARIBALDI, ITALIAN GENERAL, JUNE 27, 1861

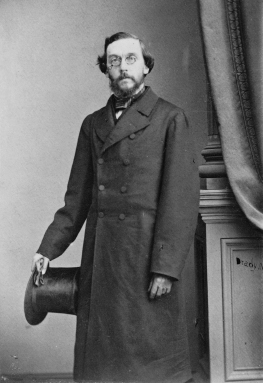

ON A HOT SEPTEMBER DAY IN 1861, HENRY SHELTON SANFORD, wearing a suit and small wire-rim spectacles perched on his nose, walked along a narrow path across a small, windswept island named Caprera, located off the northern tip of Sardinia in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. He was thirty-eight, a career diplomat, officially serving as US minister to Belgium, but it was in his unofficial capacity as head of Union secret service operations in Europe that he had traveled to Caprera to offer a command in the Union army to the most celebrated hero of the day.

After walking nearly a mile beneath a relentless sun, he arrived at a rustic house built like a South American hacienda, with whitewashed buildings and walls enclosing a rough dirt courtyard full of dogs, chickens, and a donkey. Inside the house Sanford waited amid barrels, saddles, and crude furnishings. Then he entered: Giuseppe Garibaldi, the “Hero of Two Worlds.”

Garibaldi was among that rare company of global idols—like George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, or more recently John F. Kennedy and Nelson Mandela—who transcend local fame and come to symbolize whatever ideals an admiring world attaches to them. In 1861 Garibaldi personified the Italian unification movement known as the Risorgimento (Resurgence), which had fascinated the international press and public for years. During the 1830s Garibaldi had been implicated in a revolutionary plot in Genoa and fled to South America with a price on his head. In southern Brazil he and a band of Italian exiles took up arms in the War of the Farroupilhas (Ragged Ones), a republican rebellion to secede from the slave-based Empire of Brazil. In the 1840s Garibaldi and his Brazilian wife, Anita, moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, where he led his Italian Legion against Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas. For makeshift uniforms, they donned the red smocks of slaughterhouse workers. The Red Shirt would become the emblem of the Garibaldini.1

The 1848 revolutions erupting across Europe called Garibaldi and his men back to Italy. He led the heroic defense of the Republic of Rome against French forces sent by Napoleon III to restore Pope Pius IX to his throne. Rome was forced to surrender, but not before Garibaldi led a desperate retreat across the Italian mountains with the armies of Catholic Europe (France, Austria, Naples, and Spain) in dogged pursuit. Near the Adriatic, Anita, pregnant and ill with malaria, died in his arms as enemy troops closed around them. Garibaldi escaped, fled Italy, and eventually sought asylum in America.

After exile in New York and travels in South America and the Pacific, Garibaldi returned to Italy to make a home on Caprera, and he lived there quietly until 1860. That year he stunned the world by leading a daring invasion of the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. With nothing more than a ragtag army of volunteers known as the Thousand, Garibaldi landed in Marsala, pushed back a royal Bourbon army several times larger, swept across Sicily, marched up the peninsula, and entered Naples to cheering crowds, all within four months. Dozens of international reporters and illustrators followed the Thousand during the campaign. As they moved across the Mezzogiorno, as the Italian South was known, the Garibaldini would raise their arms, point with one finger to signify one Italy, and shout l’Italia unitá!

No wonder Unionists in America were so enthused about the idea of his coming to raise his sword for l’America unitá. Everyone in Europe and the Americas knew who Garibaldi was, why he was famous, and what he looked like. His image, with his bright-red shirt and his mesmerizing gaze, was published in a steady stream of books and magazines catering to admiring fans. Women everywhere adored him. The Garibaldi fashion, featuring red blouses with puffed sleeves and short military-style jackets, had become the rage in Europe and America. His visit to London in 1864 would arouse such enormous demonstrations of public affection that conservative leaders feared he might ignite revolutionary unrest. English Protestants revered Garibaldi all the more because he was the nemesis of Pope Pius IX, who denounced him as an enemy of the Catholic Church. Garibaldi, in turn, denounced the pope as the enemy of human freedom, and he promised to make Rome the capital of a united Italy. Garibaldi named his donkey at Caprera Pio Nono in irreverent honor of His Holiness. Though a solitary and private man, Garibaldi, one Union diplomat noted, “is at this moment in and of himself one of the great Powers of the world.”2

All during the summer of 1861, while America prepared for war, the press at home and abroad had been alive with rumors that the champion of Italian reunification was about to lead the reunification of the United States. “Garibaldi Coming to America!” one headline announced. “Bully for Garibaldi!” “Garibaldi Not Coming,” another announced with equal certainty a few days later. Beginning in June and continuing through October, a series of contradictory reports, denials, and stony silence from US and Italian government officials left the world in suspense.

Whether Lincoln, or his secretary of state, William Seward, had given much thought as to how an aging Italian general who did not speak English, was severely crippled by recurring bouts of arthritis (he hobbled on crutches to greet Sanford), and had a proven record for insubordination would actually serve as commander of Union forces is unknown. Still, to have Garibaldi take command of a Union army would have been a brilliant public diplomacy coup. No foreign power would dare take sides with Southern slaveholders against the Hero of Two Worlds.3

Only later would it become known that the proposal to invite Garibaldi to lead the Union army had been his idea all along. Most of the rumors coursing through the international press could be traced back to Caprera. Candido Vecchi, the general’s secretary, later admitted to planting the idea with Henry Tuckerman, an American journalist who had written a laudatory article for the North American Review on Garibaldi as “the hero of the century.” Garibaldi himself wrote to several old friends in America recalling his “happy sojourn in your great country” and lamenting that while Italy was nearly reunited, it pained his heart to see America fragmenting. “If I can aid you in any way,” he added in one letter, “my agent in New York . . . is instructed to take and execute your orders.” When Garibaldi met that July with George Fogg, a US diplomat, he took the occasion to tell him, “If your war is for freedom, I am with you with 20,000 men.” The story flashed through the international press like lightning.4

2. Henry Shelton Sanford, US minister to Belgium and unofficial head of Union secret service operations in Europe. (MATHEW BRADY PHOTOGRAPH, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

While Garibaldi and his supporters fomented rumors of his coming to America, Seward and the diplomatic corps kept silent lest it appear they were soliciting foreign aid and violating neutrality laws by recruiting on foreign soil. Besides, any offer to such a famous foreign general was sure to stir jealousy among Union officers at home.

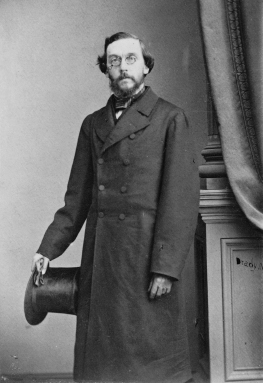

3. Giuseppe Garibaldi, known as the Hero of Two Worlds for his exploits in South America and Europe. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

But in June 1861, unbeknownst to any US official, James W. Quiggle, a holdover from President James Buchanan’s administration serving in an obscure post as US consul to Antwerp, Belgium, took it upon himself to write to Garibaldi. Quiggle had been following the Garibaldi story all summer, and, according to Henry Sanford, he and his “exceedingly pretty” young wife, Cordelia, decided to reach for glory before Lincoln’s new appointee to Antwerp arrived. Quiggle must have met Garibaldi previously and purported to “know him personally.” He used this, in any case, as the pretext for his self-appointed diplomatic initiative.5

“The papers report that you are going to the United States to join the Army of the North in the conflict of my country,” Quiggle wrote Garibaldi on June 8, 1861. “If you do, the name of La Fayette will not surpass yours. There are thousands of Italians and Hungarians who will rush to join your ranks and there are thousands and tens of thousands of Americans who will glory to be under the command of ‘the Washington of Italy.’” Quiggle took the occasion to offer his own sword to Garibaldi’s campaign in America.6

From his island retreat on Caprera, Garibaldi responded warmly, addressing Quiggle as Mio caro amico (My dear friend) and gallantly adding, “I kiss devotedly the hand of your lady.” “I should be very happy,” he told Quiggle, “to be your companion in a war in which I would take part by duty as well as sympathy.” The newspaper reports of him coming to America, he confessed to Quiggle, had not been “exact,” but he quickly added that if the US government would find his services of “some use, I would go to America, if I do not find myself occupied in the defense of my country.”

Garibaldi then posed the question to which Quiggle, Sanford, Seward, and Lincoln could not give satisfactory answer in the summer of 1861: “Tell me, also, if this agitation is regarding the emancipation of the Negroes or not.”7

Still operating entirely on his own authority, and without bothering to notify Henry Sanford, his superior in Brussels, Quiggle answered Garibaldi on July 4 to explain US policy on the matter of slavery. “You propound the question,—whether the present war in the United States is to emancipate the Negroes from slavery?” To his credit Quiggle explained Union policy honestly and accurately: the government’s sole aim was to “maintain its power and dignity . . . and restore to the Government her ancient prowess at home and throughout the world.” It would be a “dreadful calamity,” he informed Garibaldi, again in harmony with official Union policy, “to throw at once upon that country in looseness, four millions of slaves.” “But if this war be prosecuted with the bitterness with which it has commenced,” Quiggle presciently added, “I would not be surprised if it result in the extinction of slavery in the United States.”8

The next day Quiggle sent copies of all the correspondence to Seward in Washington. Mail from Antwerp to Washington usually took about twelve days by steamship. If Quiggle sent the packet on July 4, it should have arrived at the State Department by July 17, but it was not marked “received” until July 27.

These were hellish days for the Lincoln administration, and if correspondence from a minor consulate in Belgium went unnoticed, it was understandable. On July 21 the first major engagement of the war took place outside Washington. The Battle of Bull Run was a humiliating Union defeat marked by inept leadership and a panicked (some said cowardly) retreat back to the capital. Quite apart from its devastating effect on Union military and civilian morale, the international repercussions were ominous. Seward was terrified that Britain and France would use this sensational Rebel victory as a pretext for recognizing the Confederacy. With the enemy at the gates of Washington, it was now the viability of the United States as a nation that was in doubt.9

Quiggle’s dispatch might have been dismissed as the harebrained scheme of an overreaching minor official, but Bull Run put everything in a new light. On July 27 (the same day Quiggle’s dispatch was marked received), after consulting with Lincoln, Seward sent instructions to Henry Sanford, in his role as unofficial head of secret service operations in Europe:

I wish you to proceed at once and enter into communication with the distinguished Soldier of Freedom. Say to him that this government believes his services in the present contest for the unity and liberty of the American People would be exceedingly useful, and that, therefore they are earnestly desired and invited. Tell him that this government believes he will if possible accept this call, because it is too certain that the fall of the American Union . . . would be a disastrous blow to the cause of Human Freedom equally here, in Europe, and throughout the world.

It was Seward at his best, deftly elevating the Union cause above the mere subjugation of rebellion and cleverly enveloping the slavery issue within the universal cause of “Human Freedom.” Seward must have been among the New York dignitaries who met Garibaldi during his American exile more than ten years earlier, for he added, “General Garibaldi will recognize in me, not merely an organ of the government but an old and sincere personal friend.”10

Sanford had received Seward’s instructions on August 10 and for the first time learned what Quiggle had been doing under his very nose. What infuriated Sanford was not just Quiggle’s secrecy and insubordination, for enclosed with Seward’s instructions he found a gushing letter of commendation from Seward thanking Quiggle on behalf of President Lincoln for his service to his country and promising him a commission in Garibaldi’s Union army.

Sanford minced no words in his reply to Seward, characterizing Quiggle as “a low, besotted Pennsylvania politician with a single eye to money making and political capital.” When he met with Quiggle a few days later, Sanford impressed upon him the absolute necessity of “profound secrecy and great discretion.” Little good it would do. Sanford warned Seward he would probably soon be reading an account of this “with a flaming biography of G’s patron, the illustrious Quiggle.” They would never hear the end of Quiggle’s and Garibaldi’s names “joined in euphonious partnership.” Sanford, however, was an ambitious, young career diplomat who valued Seward’s confidence in him, and he was not about to allow his irritation with Quiggle to spoil what might be his own moment of glory.11

SANFORD’S MISSION TO CAPRERA HAD NOT REMAINED SECRET FOR long. On August 11 the New York Daily Tribune ran a story (possibly leaked by Seward or someone privy to the plan) that an official offer had already been tendered and accepted. “Garibaldi Coming: He Offers to Fight for the Nation,” the headline announced. The same story reached Europe on August 20, just as Sanford arrived in Turin, Italy’s capital at the time. There he met with the US minister to Italy, George Perkins Marsh, who brought him up to date on the political winds whirling about Garibaldi in Italy.12

Both men were savvy enough to realize that the famed Italian general might be trying to use an American offer to force King Victor Emmanuel II’s hand. Garibaldi wanted to complete the Risorgimento by marching on Rome and Venice, still in the hands of the pope and the Austrians. But even if he was bluffing, Garibaldi might have to come to America if only to save face, Sanford reasoned. Concerned with avoiding public embarrassment should Garibaldi turn him down, Sanford and Marsh decided to send a secret messenger ahead to Caprera with careful instructions to float an unofficial offer and learn if the Italian general was inclined to accept.13

Giuseppe Artoni, Marsh’s personal secretary, an Italian immigrant from Philadelphia. was given clear instructions to deliver a written message that Sanford and Marsh had crafted to dodge any specific offer of rank and avoid committing the Union to emancipation. It invited Garibaldi “to take part in the contest for preserving the unity and liberty of the American people and the institutions of Freedom and Self Government.”14

Sanford and Marsh had no way of knowing that the irrepressible Quiggle had, in the meantime, taken it upon himself to send a copy of Seward’s letter of commendation to Garibaldi. “From this you will see,” Quiggle crowed, “that the President has thanked me for my letter to you.” He then informed Garibaldi that Sanford was on his way with “an invitation to go to the United States, and offering to you the highest Army Commission which it is in the power of the President to confer.” Again, Quiggle assured Garibaldi that “thousands of your countrymen, thousands of Hungarians, and tens of thousands of my countrymen will rush to your arms upon your very landing at New York.”15

When Artoni arrived at Caprera, no doubt exhausted by his travels, he found himself flustered in the presence of the Italian hero, who peppered him with questions about the military rank on offer and his powers to decree emancipation. Artoni was a mere messenger with no authority to negotiate, but in the presence of Garibaldi’s charisma he apparently told him whatever he wanted to hear. Garibaldi, satisfied that all his conditions had been met, sent Artoni back with a message in French, apparently to lend diplomatic gravitas, telling Sanford that he would “be very happy to serve a country for which I have so much affection and of which I am an adoptive citizen.” But he added an ambiguous proviso: “Provided that the conditions upon which the American government intends to accept me are those which your representative (Mandataire) has verbally indicated to me, you will have me immediately at your disposal.”16

Garibaldi’s letter to Sanford also asked for time to consult King Victor Emmanuel II. Just as Sanford suspected, Garibaldi would try to arouse popular pressure among Italians by threatening to leave for America, what he called his second country, unless the king marched on Rome. King Victor Emmanuel II was irritated by Garibaldi’s gambit, particularly by his impertinent demand that the king answer within twenty-four hours. He called Garibaldi’s bluff, delayed his answer, told him he was free to go to America, and then turned the tables by urging him to remember that Italy was his first country.17

Once Sanford learned of the king’s reply, he felt confident that Garibaldi would have to accept the American offer. On September 7 he hastened to Genoa to secure passage to Caprera and wrote to Seward that Garibaldi leaving for America would cause an “immense sensation here.” September 7, as it happened, was the first anniversary of Garibaldi’s entry into Naples, and Sanford described the amazing scene in Genoa that night: the streets were full of people shouting Viva Garibaldi! “and in the principal square a wax figure of him is mounted on a kind of altar surrounded by flags at which people are bringing candles by the hundreds to burn, as you have seen in the churches of patron saints.” Using an assumed name, Sanford chartered a small steamboat and sailed into the night to Sardinia, where he arrived the next day, took a small boat to Caprera, and then made his way by foot to Garibaldi’s rustic island home.18

At last Garibaldi and Sanford were face-to-face, and the two men talked late into the evening as the sun set on Caprera. Garibaldi was dismayed to learn that, despite Quiggle’s and Artoni’s assurances, he was being invited to serve as major general in command of only one army, not as commander in chief of all Union armed forces. Sanford tried to explain to the Italian general that the president was the sole commander in chief and that a major general would have “the command of a large corps d’armée to conduct in his own way within certain limits in the prosecution of the war.” Garibaldi was either being stubborn or looking for some face-saving excuse to back away from the American invitation.19

The difference over military rank might have arisen from an honest misunderstanding, given the myriad languages involved and the misleading promises of Artoni and Quiggle. But Garibaldi’s question about emancipation exposed genuine moral confusion over just what the Union was fighting for. Sanford could only offer feeble official excuses about the legal limits of federal power to interfere with slavery. Garibaldi was incredulous. Could slavery not be abolished? If the war was not being prosecuted to emancipate the slaves, he put it bluntly, the whole conflict was nothing more than an “intestine war” over territory and sovereignty, “like any civil war in which the world at large could have little interest or sympathy.”20

Sanford went to sleep at Garibaldi’s house thinking he might salvage something from his mission to Caprera, for late that night Garibaldi had broached the idea of visiting the United States to view the situation for himself. Sanford felt that the public diplomacy value of a visit from Garibaldi, whose every utterance would be reported to the international press, might prove a great deal less risky than having the headstrong Italian actually command an army.21

The next morning Garibaldi backed away from the plan to visit America, explaining that he could not bear to watch his adopted country “engaged in a struggle for the salvation of Republican institutions” without throwing himself into battle. The two men spoke for hours that morning, and Sanford realized he had no satisfactory answers for Garibaldi and the questions the Italian hero was raising about emancipation could only embarrass the Union. Sanford left Caprera at noon to begin the long journey back to Turin to confer with Marsh and then return to his post in Brussels.22

It had been nearly a month since Sanford left Brussels. After Caprera he crafted a story that made Garibaldi’s insistence on military rank—not slavery—the main point of disagreement. He collaborated with Marsh and Nelson M. Beckwith, an American confidant in Paris who had accompanied him at least as far as Turin. Beckwith, in his role as private citizen, helped spin the story as a dispute over rank. Marsh, for his part, knew better. He wrote Seward a few days later to explain that Garibaldi would not lend his name to the Union cause unless he was convinced that it was fighting to abolish slavery.23

Whatever else Garibaldi was bluffing about that summer, he was sincere in his commitment to emancipation. A Scottish friend who had lived in America warned him he would be despised if he allowed himself to be deceived by the Americans. “You may be sure,” Garibaldi answered, “that had I accepted to draw my sword for the cause of the United States, it would have been for the abolition of Slavery, full, unconditional.”24

In Garibaldi’s mind emancipation was a hemispheric mission. That summer, in after-dinner conversation with his comrades at Caprera, he envisioned a general war of emancipation that would sweep from the American South to Brazil. “The battle will be brief,” he predicted. “The enemy is weakened [infrollito] by his vices and disarmed by his conscience.” After vanquishing the Southern slaveholders, “next, we will free the Antilles [Caribbean], so that miserable slaves will lift their heads and be free citizens, breaking those presidential seats, source of jealousies, quarrels, intestine wars, and public harm. And when, coming to the Plata River, we will have freed 42 million slaves.” Garibaldi, it seemed, was contemplating a Pan-American campaign of universal emancipation extending well beyond enslaved Africans.25

Even as Sanford made his way back from Caprera, dodging the press at every step, Garibaldi took care not to air his differences with the Union over slavery and to see that the door to America was left ajar. He wrote to Quiggle, whose reliable indiscretion would ensure publicity, promising that if the war continued, he would “hasten to the defense of a people who are so dear to me.”26

From Antwerp Quiggle was fully prepared to shift all blame for the failed mission to Caprera onto Sanford. Had secrecy been maintained, he had the gall to write Seward, “Garibaldi would now be on his way to the United States.” Overreaching as always, Quiggle asked Seward for a private interview with President Lincoln “at the earliest moment practicable” after he returned to the United States.27 Quiggle never got his audience at the White House, nor did he and Cordelia win the fame they had dreamed of in Antwerp. The Garibaldi affair eventually faded from the news and from America’s memory of the war, revisited occasionally only as a bizarre curiosity.28

But it was more than that. Garibaldi’s flirtation with the Union that first summer of war demonstrated the enormous power the press and public opinion were about to play in foreign relations and the vital importance their management would have in the diplomatic duel that was soon to unfold. Moreover, Garibaldi had raised a fundamental question about the purpose and meaning of the war that left the Union diplomatic corps confounded by its own uninspired message to the world that it sought only to preserve the Union as it was. The question was never whether Garibaldi was willing to fight for America; he wanted to know, what would he be fighting for?

Was this, Garibaldi asked, “like any civil war,” just another internecine conflict over territory and sovereignty “in which the world at large could have little interest or sympathy”? The Union would have to find answers, and soon.