WE WILL WRAP THE WORLD IN FLAMES

If any European Power provokes a war we shall not shrink from it. A contest between Great Britain and the United States would wrap the world in fire, and at the end it would not be the United States which would have to lament the results of the conflict.

—WILLIAM HENRY SEWARD, UNION SECRETARY OF STATE, JULY 4, 1861

BEFORE ABRAHAM LINCOLN HAD EVEN TAKEN OFFICE, THE Confederacy had already issued its claim to nationhood in February 1861 and set about explaining itself to the world. The new president and his secretary of state, William Seward, found themselves having to answer the Confederacy on its terms. To the Southern claim that secession was a legitimate path to nationhood, Lincoln and Seward would tell the world this was nothing more than treasonous rebellion. To charges that Republicans intended to abolish slavery and ignite racial conflagration, Lincoln answered that he had neither the constitutional power nor the intention to interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed. As for the South’s appeal to the right to self-government, Lincoln repeatedly charged that the South was violating the most sacred principles of democracy: the sovereignty of the people and majority rule. Against the South’s right to secede, Seward would advance the fundamental principle of international law: the right to national self-preservation in the face of domestic insurrection.1

When the South threatened to deprive Europe of cotton unless Europe recognized its sovereignty, Seward answered with a far more ominous threat: any nation that dared to aid the rebellion would face the United States in war. “We will wrap the whole world in flames!” he told journalists and diplomats without hesitation. “No power is so remote that she will not feel the fire of our battle and be burned by our conflagration.” He instructed his diplomats abroad to carry the same message: if the Great Powers dared to interfere on behalf of this rebellion, this civil war would “become a war of continents—a war of the world.”2

In his March 4 inaugural address, however, Lincoln adopted a temperate, conciliatory tone. His speech would lay down the basic principles underlying domestic and foreign policy, and he used the occasion to place both on the firm foundation of national and international law. Above all, Lincoln knew he must avoid lending credence to hysterical claims that his party, once in power, planned to menace the South and violate the states’ prerogatives regarding slavery.

The presidential inaugural represented the essence of democracy—the peaceful transition of power between champions of rival parties. It had been faithfully observed since 1800, when Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams, a result that, at the time, met with shrieks of alarm among conservative Federalists. In elections ever since, the party in power had yielded peacefully to the loyal opposition. It was bracing testament to what Lincoln viewed as the most fundamental principle of popular government: leaders are chosen in free and fair elections by the will of the majority, and the losing party accepts the verdict of the ballot—until the next election.

That principle was the very opposite of the revolutionary idea behind secession, and without it democratic government simply could not work. The new president had a lesson to teach on March 4 about popular government and the rule of law.

LINCOLN ARRIVED IN WASHINGTON MORE THAN A WEEK BEFORE HIS inauguration and took rooms at Willard’s Hotel, not far from the White House. Willard’s grand lobby was swarming with office seekers and reporters. Their cigars filled the air with smoke, and spit from chewing tobacco fouled the walls and carpets. Lincoln’s young secretary John Hay described the president-elect sitting serenely in his rooms at Willard’s receiving “moist delegations of bores” whose ardent demands failed to upset the “imperturbability of his temperament.” That imperturbable temperament was about to be tested mightily.3

On March 4, 1861, the sound of drums and fife filled the streets of Washington. According to custom, the outgoing president, James Buchanan, called on the president-elect at Willard’s to escort him in an open carriage to the Capitol. An estimated forty thousand people turned out for the procession. They lined Pennsylvania Avenue, some climbing trees and street poles to catch a glimpse of the new president.

Along with delegations of somber officials from the Supreme Court, the military, and the diplomatic corps was a gaily decorated carriage filled with thirty-four young girls personifying the states of the Union—including the seceding slave states. Military bands filled the air with music as the procession moved along Pennsylvania Avenue.

Yet this was no ordinary presidential inauguration. One reporter noted that the “usual applause was lacking” and that “an ugly murmur punctuated by some abusive remarks” could be heard. Poet Walt Whitman recalled that Lincoln’s convoy was surrounded “by a dense mass of armed cavalrymen eight deep, with drawn sabres,” with “sharp shooters stationed at every corner on the route.” The parade made its way to the Capitol, whose unfinished dome stood high against the sun with unsightly scaffolding jutting above graceful neoclassical arches.4

James Buchanan looked “pale, sad, nervous,” according to the New York Times. He rode next to Lincoln in silence except to complain about how much he longed to go home to Pennsylvania. As Lincoln took the oath of office, Buchanan “sighed audibly and frequently” and throughout the inaugural speech appeared “sleepy and tired” and “sat looking as straight as he could at the toe of his right boot.”5

During four interminable months between Lincoln’s election and inauguration, Buchanan, by sheer inaction and virtual abdication of power, had given the rebellion incalculable advantage. In his annual message to Congress in December, the outgoing president blamed the whole crisis on antislavery agitators and their “long-continued and intemperate interference” in the slavery question. Overseas, several of Buchanan’s appointees, still at their diplomatic posts, used their treacherous influence to encourage foreign governments to believe, as Buchanan maintained, that the federal government was powerless to stop secession and that the fragmentation of the republic was irreversible.6

6. The Outbreak of the Rebellion in the United States in 1861, by Christopher Kimmel, depicts Liberty flanked by Justice, glaring at Jefferson Davis, while President Buchanan sleeps and Abraham Lincoln appeals to generous Northern supporters. (ALFRED WHITAL STERN COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Unlike Jefferson Davis, who had given an inaugural speech two weeks earlier that was hastily prepared and consisted mostly of party-line secessionist platitudes, Lincoln labored over his address for weeks, crafting every phrase, revising and practicing until the speech conveyed exactly what he wanted to say to an anxious nation—and world. Lincoln invited advice from his secretary of state, William Seward, who leaped at the opportunity and responded with six pages of line-by-line commentary. Seward had a well-earned reputation as a pugnacious adversary of the South, but at this tense moment his editorial suggestions all aimed at softening the language and soothing Southern nerves.7

Seward viewed the secessionists as an impulsive extremist fringe, and he wanted nothing in the speech that would lend credence to their claims that Republicans were about to abolish slavery or stir unrest among the slaves. He saw himself as a mentor to the president, who, except for one term in Congress a dozen years earlier, was a newcomer to Washington and a stranger to international affairs. Seward had been Lincoln’s rival for the Republican nomination the previous summer, and the new president wanted him on the inside of the tent. Lincoln was also wise enough to recognize his own shortcomings and humble enough to seek advice. He instinctively trusted Seward and relied on his savvy grasp of politics and diplomacy. It was the beginning of a remarkable collaboration between two men who, working together, became masters of statecraft at home and abroad.8

When he took the podium on March 4, Lincoln appeared awkward, fumbling for a moment to find a place to set his top hat. Democratic senator Stephen Douglas, one of Lincoln’s rivals in the recent election, made a gracious gesture of respect by offering to hold the president’s hat. After putting on his reading glasses, Lincoln reached in his coat pocket and pulled out several sheets of paper, unfolded them on the lectern, and then unceremoniously placed his cane on the papers to hold them flat. Then, with remarkable poise, he “commenced in a clear, ringing voice,” the New York Times reported, to tell Americans what their new president was going to do about the crisis engulfing the nation.9

What people heard that afternoon depended on what they were willing to hear. Douglas heard a conciliatory promise of “no coercion.” Confederate telegrams to Montgomery fairly screamed that it was a virtual declaration of war. The significance of the speech lay in the ideological framework it provided for domestic and foreign policy. Most remarkable was that, with a few deft phrases, Lincoln managed to elevate the US debacle from a mere civil war to a crisis of momentous global significance.10

It was the underlying principle of international law, Lincoln declared, that all nations had a moral obligation to their citizens to preserve and perfect their nature as civil associations. Nations cannot set limits on their future. “I hold that in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual,” he affirmed. “Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments.” Secession, he insisted, made government practically unworkable and amounted to national suicide. No government provided “for its own termination.” Why, he asked mischievously, might not the states of some “new confederacy” decide to “secede again,” once the principle was granted? (Confederates in Montgomery, he may have known, had secretly debated provisions for secession and nullification in their own constitution and summarily rejected both as impractical.) The “central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy,” Lincoln insisted. Majority rule was the “only true sovereign of a free people,” and those who reject it must “fly to anarchy or to despotism.”11

Next the president turned to slavery. Having argued that secession was implicitly unconstitutional, he had to reconcile this point with the sacrosanct American principle of the revolutionary right of people to overthrow governments that abused the natural rights of the people. He also had to lay to rest any reasonable just cause for revolution by insisting that the new Republican administration would not interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed. He cited the Republican platform that affirmed “the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions.” Then Lincoln quoted from one of his own speeches: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

That the president had no constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in the Southern states was undisputed, but his denial of any inclination to end slavery in those states demoralized friends of freedom around the world. Lincoln then took it further by alluding to motions in Congress for a constitutional amendment banning federal abolition of slavery. On the very day of the inaugural, Congress had approved what would have been the Thirteenth Amendment. It was cosponsored by Seward in the Senate, and it would have guaranteed slavery within the United States forever. The price for perpetual Union would have been perpetual slavery. No wonder so many would question the moral purpose of the war—and of the Union, for that matter.12

SEWARD’S INITIAL FOREIGN POLICY MESSAGE TO THE WORLD ESSENTIALLY echoed Lincoln’s inaugural address. The Union was fighting for national self-preservation against a treasonous rebellion, and a rebellion without cause, for abolition was not contemplated. However, his foreign policy also contained a firm warning. According to the rules of international law, any foreign gesture of support for a domestic insurrection would be considered an act of war. On March 9 Seward issued a circular to all US diplomats abroad, instructing them to exercise the greatest diligence in counteracting any designs for “foreign intervention to embarrass or overthrow the republic.”

With this circular Seward also enclosed a copy of the president’s inaugural address, which, he explained, “sets forth clearly the errors of the misguided partisans who are seeking to dismember the Union.” He then laid out an oblique threat that discord and anarchy in such a well-established and widely respected government as America’s could infect “other parts of the world, and arrest that progress of improvement and civilization which marks the era in which we live.” Seward seemed to be issuing a cautionary advisory to foreign powers that America’s troubles might become their own if they dared give encouragement to rebellion.13

Seward also busied himself in March and April advising Lincoln on appointments to dozens of diplomatic posts around the world. Once the disloyal appointees of previous administrations were replaced, the Union would enjoy a great advantage in the impending diplomatic duel because of its vast network of legations and consulates, a reliable system of intercontinental communication, and a corps of experienced civil servants as secretaries in all the main legations abroad. Seward and Lincoln understood that the men they appointed to these diplomatic posts would be the eyes and ears, as well as the voices, of America abroad. Seward firmly believed that listening would prove more valuable than “propagandizing,” and he instructed all his diplomats to report on the press and public sentiment abroad as well as official government communications.

There was no time to waste. Eight years of pro-Southern Democratic presidents had left the diplomatic corps infested with Confederate sympathizers, several of whom were actively promoting the idea that secession was constitutional and irreversible. George Dallas, a Pennsylvania Democrat serving as US minister in London, did nothing to actively betray the Union, but his secretary Benjamin Moran recorded in his diary that “Dallas has some of the secession virus in him and he is clearly strong on the States Rights folly.”14

Charles Faulkner, a Southern sympathizer from Virginia serving as the US minister to France, refused to relinquish his post until after his replacement arrived and was suspected of using his office to convince the French government that Southern secession was irrevocable. Seward quickly sent Henry Sanford, his most trusted man in Europe, ahead to Paris to control the damage. He authorized Sanford to speak directly with the French government and explain the Union side of things, but Faulkner used his position to delay Sanford’s meeting with the French foreign minister. Thanks to Faulkner and his ilk, Sanford complained to Seward, it was now generally accepted in Paris that “the ‘Secession’ of the ‘Confederate States’ is complete.” Upon his return to the United States, Faulkner was arrested on suspicion of procuring arms for the Confederacy while in Europe. The charges were not sustained, and Faulkner was released. He later served in the Confederate army as Stonewall Jackson’s assistant.15

Eduard Maco Hudson, secretary to the US legation in Berlin, turned his talents to issuing a German-language pamphlet describing the Southern rebellion as the “second war of independence in America.” An English edition was later published in London. The outgoing minister to Madrid, William Preston of Kentucky, put his remaining time to use nurturing friendly relations between Spain and the Confederacy and returned home to serve the Confederacy as brigadier general and later as envoy to Mexico. Henry Sanford was outraged to discover that the wife of Elisha Fair, his predecessor as US minister to Belgium, had stolen the legation seal and was using it on letters she sent out to encourage European support of the secessionist cause. She “is excelled by no secession agent abroad” in this ugly business, Sanford wrote to Seward. If the Union had “one half the amount of sharp activity the Secessionists have shown,” instead of the betrayal or stony silence demonstrated by “those who profess to represent us,” the South would never have made such headway convincing Europe that secession was fact.16

MEANWHILE, IN WASHINGTON, LINCOLN MOVED QUICKLY TO FILL key diplomatic posts with his own loyal men. Ministers to the Great Powers of Europe were handsomely paid, and the posts came with enviable status and perquisites. Lincoln was no different from other presidents in treating diplomatic appointments as political rewards for supporters. Remarkably little attention was paid to even such basic qualifications as prior experience abroad, knowledge of international law, familiarity with the host country’s history, or even comprehension of its language. If America’s diplomats “talk abroad as they do at home,” John Bigelow, future envoy to France, once wryly observed, “the fewer languages at their command the better.”17

More than the candidates’ qualifications, what often mattered was what state they were from, the political faction they represented, and how their appointment might help the party in the next election. Politics trumped diplomacy, but if diplomacy sometimes suffered, there would also be benefits to having men practiced in the arts of democratic politics and public persuasion ready for the contest of public diplomacy that was about to unfold overseas.18

One week after taking office, on March 11, Lincoln sent Seward a memo suggesting how he might fill what they anticipated correctly to be four key diplomatic posts. Britain and France were the most critical. These were the two leading naval powers in the world, and both were heavily dependent on cotton from the South for their textile industries. Spain was a feeble imperial power, but its colonies, Cuba and Puerto Rico, remained dependent on slave labor, and that made Spain a dangerous potential ally of the South. Mexico was crucial because of its seaports on the Gulf and its long border with Texas, which would provide a vital supply route, circumventing the Union blockade Lincoln was about to impose. “We need to have these points guarded as strongly and quickly as possible,” Lincoln told Seward.19

For London, clearly the most critical post, Lincoln proposed William Dayton of New Jersey, an old Whig and the Republican candidate for vice president four years earlier. Dayton was an amiable if not always diligent man who had no diplomatic experience or any discernible knowledge of Europe to recommend him. For Paris, Lincoln wanted John C. Frémont, who ran for president on the Republican ticket with Dayton in 1856. He was the son of a French immigrant and was wildly popular with European liberals for his antislavery views. Cassius Clay, a colorful antislavery Republican from Kentucky known to pack pistols and a bowie knife, Lincoln thought fit to serve as ambassador at court in Madrid. For Mexico City, he wanted his old friend Ohio congressman Thomas Corwin, whose opposition to the US war with Mexico in 1846 made him hugely popular among Mexican liberals.

Seward concurred on Corwin, who would be heartily welcomed in Mexico by Benito Juárez, the newly elected president of a republic that had just emerged from its own civil war and still faced intransigent opposition from conservative monarchists and Catholics. For London, however, Seward persuaded Lincoln to appoint Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts. He had a well-tempered mind, and politics and diplomacy ran in the Adams family blood; his grandfather, John Adams, and father, John Quincy Adams, had served as distinguished diplomats as well as presidents. Besides, Seward noted, a New England appointee would help Republicans in the next election. Seward had little use for Frémont because of his radical antislavery views, and instead he got behind Dayton for the Paris post, despite his utter lack of qualifications. Cassius Clay met the need for a border-state nominee, and they decided to send him to St. Petersburg, Russia.

Lincoln wanted to reward “our German friends” who had helped deliver the Midwestern immigrant vote to the Republicans. Carl Schurz, a radical who fled Germany for Wisconsin after the failed Revolution of 1848, had been a loyal campaigner, and he wanted the appointment to Italy. Seward distrusted Schurz, and the entire radical wing of the Republican Party for that matter. He argued that such an appointment would offend a conservative Catholic country, and he even tried to impose a general rule against the appointment of any foreign-born ministers to diplomatic posts. Lincoln relented and filled the Italian post with George Perkins Marsh, a Vermont Republican with a cultivated mind, a command of several languages, and years of successful diplomatic experience in Istanbul. But Lincoln insisted on sending Schurz to Madrid, a far more conservative Catholic nation than Italy.

Thus, politics and diplomacy commingled from the start, and not always with good results. Most of Lincoln’s appointees, like those of the Confederacy, would begin as amateurs, learning the art of statecraft on the job. They were plunging into an uncharted world of public diplomacy, where their political instincts would often serve them well.20

In a democracy with a new party and president coming to power, everyone was learning on the job, not least Abraham Lincoln. William Howard Russell, the London Times correspondent, recorded a comical vignette of Lincoln and Seward at their diplomatic debut a few days after the inauguration in March 1861. Italy, following the annexations of Sicily along with several other small kingdoms and duchies, was applying anew for recognition as the Kingdom of Italy. Russell described Italy’s dashing emissary to Washington, Giuseppe Bertinatti, who arrived at the White House dressed in full diplomatic regalia, with a “cocked hat, white gloves, diplomatic suit of blue and silver lace, sword, sash, and ribbon of the cross of Savoy.” A tall, handsome, slim man, the Italian ambassador walked into the White House beside Seward, whose hair and clothes were, as usual, slightly rumpled.

Russell watched as Old World pomp encountered American rusticity. Seward and Bertinatti stood side by side at the center of the room as President Lincoln entered. Russell described a “tall, lank, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms, terminating in hands of extraordinary dimensions, which however were far exceeded in proportion by his feet.” He was dressed in “an ill-fitting, wrinkled suit of black, which put one in mind of an undertaker’s uniform at a funeral.” His “strange quaint face” was topped by a “thatch of wild republican hair.”

Lincoln walked across the room, greeting everyone with a smile, and then “was suddenly brought up by the staid deportment of Mr. Seward” and “the profound diplomatic bows of the Chevalier Bertinatti.” Lincoln “suddenly jerked himself back, and stood in front of the two ministers, with his body slightly drooped forward and his hands behind his back, his knees touching, and his feet apart.” Seward made his formal presentation, “whereupon the President made a prodigiously violent demonstration of his body in a bow,” which Bertinatti answered with another bow and then read the message from his king, asking to be received in Mr. Lincoln’s court. This ritual of recognition so readily accorded the newly constituted Kingdom of Italy was exactly what Confederate envoys longed for abroad.21

IT IS EASY TO UNDERSTAND HOW SEWARD SAW HIMSELF TUTORING Lincoln in the ways of Washington, the rituals of office, the strange pomp of diplomacy, for that was exactly what he was doing. In truth, Seward and Lincoln quickly formed an exceptional working relationship and learned from each other. Though not always in harmony, they came to embody complementary foreign and domestic policies, and the Union’s eventual success at home and abroad owed much to the close understanding that developed between these two men.22

There is no denying that Seward was at first jealous and condescending toward the prairie lawyer who occupied the office for which Seward had been preparing all his life. “Disappointment!” he lashed out at one startled congressman that first spring. You speak of disappointment “to me, who was justly entitled to the Republican nomination for the presidency” and “had to stand aside and see it given to a little Illinois lawyer! You speak to me of disappointment!” But Seward soon came to admire Lincoln’s gifts while flattering himself to think the president could not manage without him. “The president is the best of us,” he wrote his wife, Frances, in early June 1861, “but he needs constant and assiduous cooperation.”23

The president was willing to defer to Seward on the execution of foreign policy. “I don’t know anything about diplomacy,” he told one astonished foreign diplomat. “I will be very apt to make blunders.” He also told Seward at the outset, “There is one part of my work that I shall have to leave largely to you. I shall have to depend upon you for taking care of these matters of foreign affairs, of which I know so little, and with which I reckon you are familiar.”24

Lincoln reckoned correctly. Seward enjoyed years of experience on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and he had traveled extensively in Europe. He was conversant in French and well read on world affairs. An ardent nationalist, Seward foresaw America’s future as a major world power. He was keenly aware that European monarchists harbored deep jealousy and resentment toward the United States, its democracy, and its success. At sixty years of age, with years of service before him, Seward was eager to assume an indispensable role as consigliere to the neophyte president, the knowing guide to the inner mysteries of Washington politics and to the peculiar world of diplomacy.

But Seward also earned a reputation for presuming too much authority over the new president, acting as though he were a prime minister and mistaking Lincoln’s inexperience with an incapacity to manage the presidency. In a bizarre memorandum dated April 1, 1861, Seward took it upon himself to set forth “some thoughts for the President’s consideration.” The April 1 memo opened with an unfortunate tone of impatience, complaining that after a month, the administration was “yet without a policy either domestic or foreign.” Seward quickly laid out his solution, numbering and underlining its main points. “My system is built upon this idea as a ruling one, namely that we must Change the question before the Public from one upon Slavery, or about slavery for a question upon Union or Disunion.”25

The secretary of state proposed that Fort Sumter be abandoned because in the public mind, it had become closely associated with the slavery question. The issue he wanted Americans to focus on was the menace of Spain in the Caribbean. Only two days earlier, news had arrived that Spain had launched an invasion of its former colony, Santo Domingo, and proclaimed its reannexation. Rumors were flying that the French were cooperating and poised to take over their former colony in neighboring Haiti. “I would demand explanation from Spain and France, categorically, at once,” Seward advised the president. “I would seek explanations from Great Britain and Russia, and send agents into Canada, Mexico and Central America, to rouse a vigorous continental spirit of independence on this continent against European intervention.” Then he came to the point: “If satisfactory explanations are not received from Spain and France,” Lincoln should “convene Congress and declare war against them.”26

Seward was possessed by an idea—a patriotic fantasy, in truth—that historians would later call his “foreign war panacea.” Faced with a foreign enemy menacing America, Unionists in the North and South would reunite and rally around the flag. The “hills of South Carolina would pour forth their population to the rescue of New York,” Seward told a home-state audience the previous December.27

During a dinner party at the home of British ambassador Lord Lyons not long before his April memo, Seward, cigar in hand and speaking loudly, told Lyons, Henri Mercier, the French ambassador, and Eduard Stoeckl, Russia’s envoy, that “the best thing that could happen to America right now would be for Europe to get involved in some way in her affairs.” It would create international upheaval, and “not a government in Europe would remain standing.” Mercier thought he must have had too much to drink, but as he warned the home office in Paris: in vino veritas. Lyons also worried that Seward was itching for war. Among Northerners, he wrote to London, “a Foreign war finds favour, as a remedy for intestine divisions.”28

It was never clear to foreign diplomats and reporters whether Seward was just blustering or if he actually thought he could resolve the domestic crisis by creating an international crisis. He was deliberately trying to frighten European powers from intervention in America’s crisis by suggesting that he welcomed rather than feared war with them. If he was sometimes intemperate with language and drink, it seemed to serve his purpose of intimidation all the better. More than one foreign diplomat and head of state feared Seward precisely because they thought he was half-mad.29

There was no doubt that in his April 1 memorandum, Seward questioned Lincoln’s command of the situation. He advised that, because the president was preoccupied with other matters, an experienced cabinet member might take charge of formulating clear domestic and foreign policies. “I seek neither to evade nor assume responsibility,” he closed rather disingenuously.

Lincoln probably spoke with Seward about the memo, but for the record he also wrote out a careful reply that gave no hint of irritation yet explained firmly that his inaugural address had already delineated the administration’s domestic policy. He saw no good reason to surrender Sumter. As for foreign policy, until now Seward’s own policy had been conciliatory. Spain’s Santo Domingo invasion was new, Lincoln admitted, but he saw no advantage in fomenting war over this incident. He added that while he valued advice from all cabinet members, whatever “must be done, I must do it.”30

The story of Seward’s “April Fool’s Day memorandum,” as his detractors would later call it, is usually told as an internal challenge to a novice president answered by Lincoln’s bold assertion of command. But there was a good deal more to it. Seward and his confidant Thurlow Weed, a savvy New York political operator and newspaper publisher, had an elaborate plan to leak the memo to the New York Times and other newspapers and to launch a barrage of editorials and news stories that would incite public outrage against Spain and France. It was a revealing example of Seward’s conflation of diplomacy and domestic politics, and it demonstrated his readiness to use the press as a tool of diplomacy. The episode also reveals Seward deliberately making use of loose talk, bluster, and brinksmanship to intimidate foreign adversaries as much as to arouse patriotic sentiment at home.31

Weed had come down to Washington several days earlier to help work out the plan with Seward. On March 31 Henry J. Raymond, editor of the New York Times and a stalwart Republican, joined them, arriving by train at midnight. James Swain, the Washington correspondent for the New York Times, brought Raymond to Seward’s residence and then waited at his own house. Raymond instructed him to keep the telegraph lines open for a “marvelous revelation to the readers of the Times.” At four in the morning on April 1, Raymond finally showed up at Swain’s house and asked for a drink. It was not until the second bottle, Swain remembered, that his boss revealed what was in the works.32

The plan was to publish Seward’s memorandum to Lincoln, along with the president’s reply, on the front page of the New York Times later that day. Seward and Weed both assured Raymond that the president “could not fail to be in accord with the suggestion of the Secretary.” Meanwhile, Raymond was to return to New York, whip up a “vigorous editorial endorsement of the programme,” and issue “an unmistakable pronunciamento that Seward alone” could carry it out. It sounded like Seward and his cronies were plotting a palace coup. Of course, Lincoln’s cool response to Seward’s April 1 memo forced a change of plans.33

On April 1 the New York Times contained no “marvelous revelation” of Seward’s ascendancy, but it ran a robust editorial denouncing plans for predatory foreign intervention in the American hemisphere. Alluding to the alarming reports from Malakoff, the newspaper’s Paris correspondent, that Britain, France, and Spain were preparing to send fleets of warships, supposedly “for observation” of America’s coasts, the editorial painted a dark picture of the American republic besieged by its Old World nemeses.

French fleets in American waters—Spanish cruisers hovering in our Gulf—English men-of-war along our coasts;—significant rumors from France of her assuming new relations with her old province of Louisiana—burning, secret sympathies of England with her enslaved black “men and brothers”—menacing attitude of the Spanish Government, . . . which now, in our time of trouble, taunts and defies us by stationing ten thousand troops within fifty miles of our shores, to keep eye upon us, and possibly, in the domestic melee she hopes for, to repossess herself of the splendid provinces which, as Florida, Texas, etc., we now call sovereign States of the Union.

The editorial closed with a rousing call for domestic unity in the face of foreign enemies, but if this was the fuse for Seward’s scheme of a foreign war that would reunite North and South, it failed to light.34

SEWARD’S APRIL I SCHEME MAY NOT HAVE GONE ACCORDING TO PLAN, and his ambitions to become virtual prime minister were curbed, but the more important point is that Lincoln supported Seward’s underlying foreign policy strategy. The main issue before the public was already “Union or Disunion,” not slavery or abolition. In his April 1 memorandum, Seward proposed an aggressive, hard-power foreign policy whose cardinal feature was the blatant threat of foreign war, and to that Lincoln had no objection.

The next day, April 2, Seward began implementing his strategy by sending a menacing warning to the Spanish ambassador, Gabriel García Tassara, in which he promised a “prompt, persistent and, if possible, effective resistance” to Spain’s aggression in the New World. At the same time, he wrote to the French ambassador in Washington, Henri Mercier, and to Lord Lyons, Britain’s ambassador, to inform them of his protest against Spain and, by implication, to warn them against any cooperation or aggression on the part of their governments.35

Seward then put his mind to writing instructions to each of his newly appointed emissaries abroad. These were lengthy, complicated expositions tailored to the circumstances of each foreign country. They were meant to inform the ministers of the official policy of the US government and provide debate points for defending those policies. Underlying each of the sometimes rambling and philosophical letters of instruction were the core principles of Seward’s foreign policy: First, the conflict was an American domestic insurrection taking place within one permanent and inviolable nation. Second, this was a rebellion without cause, pretext, or any defensible goal; the Union was focused upon “national self-preservation” and not abolition. Third, any nation recognizing or aiding the rebellion would risk war with the United States.

Seward’s April 10 instructions to Charles Francis Adams went out more than a month before Adams would even get to London (he was home in Massachusetts attending his son’s wedding). “You will not consent to draw into debate before the British government any opposing moral principles which may be supposed to lie at the foundation of the controversy between those States and the federal Union.” (Ironically, this was essentially the same warning Toombs gave his Confederate European commissioners.) Adams was instructed to remind Britain of the dire consequences of recognizing the “so-called Confederate States.” Should the rebellion succeed, there would be “perpetual war” within North America, because the “new confederacy” would, “like any other new state, seek to expand itself northward, westward, and southward.” No part of North America or the Caribbean, he warned the British who had possessions in both places, could expect to remain at peace.36

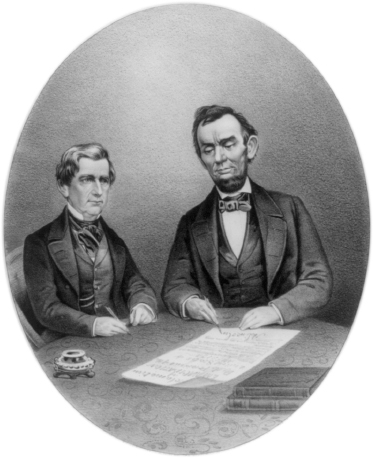

7. William Seward and Abraham Lincoln, Currier and Ives. (ALFRED WHITAL STERN COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

It was April 22 before he sent instructions to William Dayton in Paris. Seward advised him also to “refrain from any observation whatever concerning the morality or the immorality, the economy or the waste, the social or the unsocial aspects of slavery.” He was emphatic in making the French understand that slavery and abolition were not at issue. “Whether the revolution shall succeed or shall fail,” he wanted Dayton to explain, “the condition of slavery in the several States will remain just the same.”

Dayton was to tell the French that the goal of the South’s revolution was “the overthrow of the government of the United States,” whose establishment “was the most auspicious political event that has happened in the whole progress of history.” Seward, apparently oblivious to the French Second Empire’s antipathy toward republicanism, took this further by instructing Dayton to communicate that America’s “fall must be deemed not merely a national calamity . . . but a misfortune to the human race.” He then applauded France’s valiant role in emancipating the American colonies from British tyranny and then, inexplicably, called upon Napoleon III’s decidedly undemocratic regime to help defend their common principles of “universal suffrage” and “free popular government.” It was a clumsy appeal to republican ideals the French government detested.37

By instructing extreme caution on the subject of emancipation, Seward clearly wanted to soothe anxieties among government leaders and business interests abroad that his government might plunge the nation into social conflagration, and throw world cotton markets into chaos, by some reckless edict to abolish slavery. But more was involved here. Seward’s own deep reservations about radical abolitionist programs guided his foreign policy.

FEW KNEW THAT SEWARD CAME FROM A FAMILY OF SLAVE OWNERS AND grew up surrounded by the peculiar institution in New York, where slavery survived until 1827. His memoirs recalled with fondness the many hours he spent in the family kitchen listening to the family’s slaves, enthralled by their astonishing tales of the supernatural. Yet he was equally impressed by the desire of slaves to be free. He never forgot Zeno, a slave owned by another family, who was among his childhood playmates. Zeno had run away after being “severely whipped” and was brought back with an iron collar fastened on his neck. He later stole away again, this time for good. Then one of the Seward family’s slaves fled soon after Zeno left. “Something was wrong,” Seward recorded in his memoirs, “and I determined, at an early age, to be an abolitionist.” Seward’s moral objections to slavery were genuine, but he steadfastly favored the New York model of gradual emancipation and consistently warned of the dangers of sudden abolition.38

As an aspiring politician, Seward became the protégé of Thurlow Weed, the savvy New York newspaper publisher and political operator who managed Seward’s early rise from state senator to governor and then to the US Senate in 1848. That was the year Lincoln and Seward first met at a political rally in Boston. They wound up sharing a hotel room the next night in Worcester and talked deep into the night about politics and the slavery question. Seward told Lincoln that he had come to realize the time was right to speak out against the expansion of slavery. By Seward’s account, his roommate was far more cautious. Seward continued talking that night in Worcester, until Lincoln finally conceded the point—whether out of conviction or exhaustion, it was never clear. That year Lincoln left Congress and retreated into the relative obscurity of Illinois politics for a decade. Seward, meanwhile, became the leader of the antislavery “conscience Whigs” and the voice of the rising Republican Party, on his way, so it seemed, to becoming its first president.39

In part to restore his health, but also to absent himself from the American press before the 1860 election and prepare for office, Seward embarked on an extended tour of Europe and the Middle East in May 1859. He was greeted abroad as the president-in-waiting. In December he returned to a troubled nation in time to prepare for the coming election. The best-laid plans of mice, men, and politicians sometimes go awry, and they did for Seward at the Republican nominating convention, held in Chicago in the summer of 1860.

Significantly, several key Republicans thought he was too radical on the slavery question; his recent speech on the “irrepressible conflict” between North and South and his earlier appeal to a “higher law” than the Constitution haunted his prospects for the nomination. Eager to win moderates and bring in disaffected Democrats, Republicans chose Lincoln over Seward, not because of any fundamental disagreements on the slavery issue (their sentiments and policies were not far apart) but precisely because Lincoln was less well known. For Seward, it was a severe blow. He was not going to let the slavery issue wreck his new career as secretary of state and adviser to the president.40

Seward and Lincoln were as one on the basic message that the Union was waging war only to preserve the Union and not to abolish slavery. In addition to delegitimizing the South’s justification for rebellion, this policy accorded with both men’s view that, whatever their moral revulsion toward human slavery, the institution was protected by the Constitution and vital to both the American and world economies. An “abolition war,” they feared, would endanger support for the Union at home and abroad.

SEWARD’S MESSAGE ON SLAVERY AIMED AT REASSURING GOVERNMENT and business leaders, but his diplomatic corps abroad soon warned him that more liberal elements in the European public expected the Great Republic to seize the opportunity to destroy the cause of the rebellion and advance the cause of liberty. Europeans were genuinely puzzled by the Union’s conservative, legalistic position and lack of moral purpose in waging war. Seward’s ministers, whom he had instructed to report on public opinion, warned him that if the conflict was viewed only as an American quarrel over secession and territory, the world would just as soon see the Union dismembered.

“You must make up your mind to commense an anti slavery crusade in England,” Henry Sanford, unofficial chief of public diplomacy operations in Europe, wrote Seward in May 1861. “Send over some good speakers, spend a little money and we can carry the country with us.” Europeans, he told Seward, supposed the war was being waged for “the Extinction of Slavery,” and they held no interest in local political contests or legal squabbles over the right to secession. The public, if not the governments and the press, Sanford assured him, would be with them once it was made clear that the Union was on the side of liberty.41

None of Seward’s ministers was more prescient than Carl Schurz, writing from Madrid in September 1861. The Union, he advised Seward, must “place the war against the rebellious slave States upon a higher moral basis and thereby give us the control of public opinion in Europe.” Conservative monarchies in Europe saw America’s war as the “final and conclusive failure of democratic institutions,” and they would find in this catastrophe “an inexhaustible source of argument in their favor.”

The Union was forfeiting its most appealing moral assets, Schurz bluntly told Seward. Friends of liberty in Europe assumed that the war would “be nothing less than a grand uprising of the popular conscience in favor of a great humanitarian principle.” Yet Union envoys were being sent abroad with instructions not to even mention slavery as “the cause or origin” of the war. Why, Schurz asked sarcastically, should Europeans support the North if its only goal was “the privilege of being re-associated with the imperious and troublesome Slave States”?

Confederate agents in Europe had learned to make their appeal in the liberal language the European public admired, Schurz noted. They, too, “carefully abstain from alluding to the rights of slavery,” but they made alluring offers “of free-trade and cotton to the merchant and the manufacturer, and of the right of self-government to the liberal.” The rebels were beating the Union at its own game by appealing to freedom. “It is my profound conviction,” Schurz concluded his plea from Madrid, “that, as soon as the war becomes distinctly one for and against slavery, public opinion will be so strongly, so overwhelmingly in our favor, that in spite of commercial interests or secret spites no European Government will dare to place itself, by declaration or act, upon the side of a universally condemned institution. Our enemies know that well, and we may learn from them.”42

These admonitions from Henry Sanford and Carl Schurz were the first of many coming back to Seward and Lincoln from abroad. These were not what the secretary of state wanted to hear. Though Union agents had been instructed to glean what they could about the foreign press and public opinion, their counsel was not always welcome when it contradicted Seward’s stubborn conviction that Europe’s governing classes feared an abolition war that would disrupt the cotton markets. Seward also instinctively distrusted radicals like Schurz, whom he accused of meddling in domestic and military policies that were not his concern.

Seward answered Schurz’s impassioned tour de force from Madrid with a terse, icy message that essentially told him to mind his diplomatic business in Spain. In it the secretary of state feigned indifference to foreign opinion and blustered foolishly about the Union’s capacity to take on all enemies. “I entertain no fears that we shall not be able to maintain ourselves against all who shall combine against us,” he wrote. “This confidence is not built on enthusiasm, but on knowledge of the true state of the conflict, and on exercise of calm and dispassionate reflection.” Schurz, Seward implied, ought to exercise his own dispassionate reflection.43

Seward was not as pigheaded as he sounded in his scolding letter to Schurz; nor was he indifferent to public opinion abroad. Even as he wrote it, that October he was busy launching a pioneering program in public diplomacy. The idea of employing unofficial agents to manage the press, lobby politicians, and persuade the foreign public was nothing new in the history of war and diplomacy. Efforts to shape diplomacy by influencing public sentiment had many precedents. Benjamin Franklin in Paris during the Revolution may have been the most famous of such ambassadors to public opinion, but he was neither the first nor the last.44

8. Carl Schurz, appointed US minister to Spain, later served as major general in the Union army. (CARL SCHURZ, REMINISCENCES)

America’s Civil War, however, witnessed the first organized, sustained government programs in which each side fielded special agents whose sole aim was to mold the public mind and, thereby, affect the foreign policy of other governments. It was a prolonged conflict, and each side had time to develop campaigns abroad. More important, the war took place at a time when mass-circulation newspapers and magazines flourished on both sides of the Atlantic. The vast expansion of print culture was accelerated by robust rivalry among political parties, each with its own journal, and aided by new communications technology—steam-driven printing presses, telegraphs, and steamships—that allowed rapid transmission of foreign news.

Large metropolitan newspapers hired foreign correspondents in major capitals, or they sent over traveling reporters and war correspondents. Malakoff and Monadnock (pseudonyms for New York Times reporters), William Howard Russell, Karl Marx, Ottilie Assing, and a host of other journalists were all part of a new phenomenon, the international press. These developments both created and served a vastly expanded readership and provided a powerful instrument by which foreign governments could at once take the pulse of public opinion and get their stories before readers. None understood the power of the modern press better than regimes such as Napoleon III’s France, where articles were scrupulously censored and publishers fined for infractions.45

The rivalry between Union and Confederate agents abroad fueled the growth of public diplomacy campaigns. Agents on both sides warned their home offices that the enemy was beating them in the contest to manage the press and win public sympathy abroad. They implored their governments to send more money and men to counter the success of their rivals, and—without exactly knowing how to measure their own success—the commitment to swaying public opinion abroad grew apace.

Not all of their efforts were aboveground. Seward had given Henry Sanford a sizable purse for secret service operations throughout Europe. Much of his time and resources went toward building an extensive espionage program to gather intelligence on rebel procurement of arms and supplies, but he was also engaged in managing public information and launching the Union’s public diplomacy campaign abroad. Soon after he arrived in Europe in April 1861, Sanford wrote to Seward, urging a covert public diplomacy program whose aim would be to “correct the public mind through the Press and refute the errors of fact or opinion so prevalent.” From Paris he sounded an early warning that the “Southern (Creole) element here . . . has the power of influencing greatly the public press,” which was “full of erroneous statements calculated to prejudice public opinion against the cause of the Union.” Some of these press misstatements were the result of ignorance, Sanford allowed, but others were the product of “considerations” (bribes) issued by pro-Southern interests.46

Sanford wanted to offer his own “considerations” to willing foreign journalists. He hired A. Malespine, a Paris journalist for the liberal Opinion Nationale. A devoted republican who had spent time in the United States and was fully in sympathy with the Union, Malespine was not above receiving a monthly stipend of five hundred francs for lending his pen to the cause. The “best way to discredit the South,” Malespine advised Sanford, is “to prove that slavery is the cause of the war, and that the South fights only for the maintenance of that institution.” In addition to his columns in the Opinion Nationale, Malespine published several pamphlets informing French readers about the war.47

Sanford was the first to sound the alarm that US diplomatic posts abroad were swarming with “men of doubtful loyalty,” mostly Buchanan appointees. It was an early lesson in public diplomacy, for several of the disloyal diplomats had used their positions to persuade foreign officials and the press that the US Constitution actually permitted secession and that separation was inevitable in any case. That message of inevitability proved especially stubborn, and Sanford worked assiduously to counter it by working the press, hiring sympathetic authors, subsidizing influential journals, and seeing that erroneous views of the situation were promptly corrected by letters to the editor. But it would not be enough to simply “correct the public mind” on the errors implanted by rebel sympathizers. Union agents abroad still needed an appealing message to tell the world why they fought and why this was something more than just an American civil war.

BACK IN WASHINGTON, SEWARD ACCELERATED THE UNION’S COMMITMENT to courting favor among the European public after the embarrassing disaster at Bull Run in late July 1861. Seward was terrified that this humiliating Confederate victory would prompt European powers to recognize the Confederacy, and he desperately sought ways to arouse opposition among the European public. That was when he sent Sanford to Caprera on his ill-fated mission to enlist Garibaldi. In August Seward appointed John Bigelow, a well-traveled, savvy New York newspaper publisher and seasoned political operative, to assist Sanford and Dayton in France and Europe generally. Officially, Bigelow would serve as consul general to Paris, but off the record he was there to back up Dayton, Lincoln’s choice for the post and one whose ignorance of the French language and politics worried Seward. Dayton knew his limitations, and to give him credit, it was his idea to bring over someone “accustomed to the use of the pen” and with good connections to leading men in the European press and government circles. “If a little money were judiciously expended here,” Dayton wrote to Seward in late May 1861, “it would go far to put the public sentiment right in certain quarters.” Bigelow was one of Seward’s most brilliant appointees, and he soon became a pioneering master of the arts of public diplomacy in Europe.48

9. John Bigelow, US consul to Paris and unofficial chief of public diplomacy in France. (MATHEW BRADY PHOTOGRAPH, BRADY-HANDY COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

When Seward learned in September 1861 that the Confederates were sending James Mason and John Slidell to Europe, he stepped up efforts in public diplomacy to counteract their influence. In October he organized the first of a procession of private citizens sent over as spokesmen for the Union cause. Seward’s special agents were religious leaders, literary figures, financiers, businessmen, and politicians whose job it was to address the foreign public as well as meet with government officials, and in every way to “enlighten” the public mind about the “true nature” of the conflict in America.

Henry Adams marveled at the men Seward sent over. He “had a chance to see them all, bankers or bishops, who did their work quietly and well.” To the outsider, he wrote, “the work seemed wasted and the ‘influential classes’ more indurated with prejudice than ever.” But this was misleading: “The waste was only apparent; the work all told in the end.”

Not least among Seward’s public diplomacy innovations was his decision in late 1861 to launch the annual publication of the State Department’s diplomatic correspondence with the president’s annual message to Congress. Although carefully selected and edited, the publication of these dispatches created an extraordinary image of a government whose foreign policy aims were transparent to the world.

At the same time, Seward deployed numerous clandestine special agents whose job it was to shape the public mind overseas. Later, during the impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868, Seward acknowledged to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he had secretly paid for the services of twenty-two special agents (including Garibaldi, it turned out), for a grand sum of $41,193. Had the Union sent to England and France at the beginning of 1861 the men it sent later, Seward told the senators, the machinations by which the rebels gained belligerent rights might have been defeated. In retrospect, Seward testified, “the national life might have been lost” but for the services of these men.49

Seward’s first public diplomatic mission of this sort included two religious leaders: Archbishop John Hughes, an immensely popular New York Catholic of Irish origin, and Bishop Charles McIlvaine, an Ohio Episcopalian who was well known in Europe and a former chaplain to the US Senate. Thurlow Weed, Seward’s trusted confidant, came along at the insistence of his friend Archbishop Hughes, or so the story was told. Actually, Seward had a more important role in mind for Weed. Their mission, as Seward dexterously explained in his letter of introduction to Charles Francis Adams in London, was “to counteract the machinations of the agents of treason against the United States” and to do so “in a way and to a degree which we could not reasonably expect from you.” At the last minute, this unlikely band of clergy and politicos was joined by General Winfield Scott, the venerable commander of the Union army and hero of the Mexican War, recently retired and on his way to meet his family in Paris. Scott had his own unofficial diplomatic mission in mind: he confided to Seward that he planned to meet “in private circles” with European leaders to thwart “those arch-traitors Slidell and Mason.”50

Seward’s troupe of public diplomatists sailed out of New York on November 9, and after a rough fifteen days at sea they arrived at Le Havre, France, on November 24. It was three days later that news of the Trent affair reached them in Europe. The explosion of indignation from Britain suddenly cast a grave shadow over their entire mission.

US diplomats in Europe still had no official explanation from Washington, which left Adams and the whole legation in London paralyzed as the British press raged against their country. Adams confided to his diary that war was inevitable. He even pondered withdrawing from London, perhaps staying on the Continent until matters were clarified. The “policy of Lord Palmerston is to terrify America into such terms as he will dictate,” Adams wrote. “He may be successful.” The mood at the US legation “would have gorged a glutton of gloom,” Adams’s son Henry remembered. All of them felt “as though they were a military outpost waiting orders to quit an abandoned position.”51

In Paris friends of the Union were equally demoralized by the prospect of war with Britain, while Confederate partisans were rejoicing over l’affaire du Trent. John Bigelow instinctively recognized it as a problem to be addressed through public diplomacy. On December 2, 1861, days after the Trent news arrived, he sought the wise counsel of Louis-Antoine Garnier-Pages, a stalwart member of the French republican opposition who stood by the Union and believed that “the future of republicanism in Europe depended upon the success of republicanism in America.” Bigelow found his friend utterly despondent over the crisis, and he tried to ease his mind. As Bigelow explained, the Trent affair was probably nothing more than an ambitious naval officer acting on his own authority and not meant as an insult by the US government and certainly not a provocation of war. Garnier-Pages was visibly relieved; he urged Bigelow to sit down immediately and write up what he had just told him, and they would submit it to the newspapers the next day.

Bigelow told his French friend that in his official status, he could not sign such a letter, but he knew just the man who could. He hurried over to the Hotel de Europe and implored Thurlow Weed, who had just arrived, to persuade General Winfield Scott to sign a public letter that Bigelow would compose. “Old Fuss and Feathers,” as General Scott was affectionately known, could be prickly, but on the voyage over Weed had bonded with the old man, and he assured Bigelow he would try working his charm. Weed found Scott holed up in his rooms at the Hotel Westminster, suffering a painful bout of rheumatic gout, a hand and leg badly swollen. Scott was in despair that America was about to be pulled into war with Britain and was already preparing to return to New York City to advise on preparing harbor defenses in the event of British attack. He told Weed he would sign the letter.

Meanwhile, Bigelow was back at his office, furiously drafting the letter. It was framed as an informal message from Scott to a fictitious friend, assuring him that there was no reason for concern that Britain and the United States might go to war. After scoring a few gently lodged blows against British transgressions on the high seas prior to the War of 1812, Bigelow’s letter made a deft turn toward conciliation: “I am sure the President and people of the United States would be but too happy to let these men go free, unnatural and unpardonable as their offences have been, if by it they could emancipate the commerce of the world.” Bigelow hurried the draft over to Scott’s hotel room, and, to his enormous relief, the old warrior signed it with no changes.

The Bigelow-Scott letter was published the next day, December 3, appearing simultaneously in all the leading Paris and London journals. Miraculously, the letter met with an immediate calming effect, as though providing an excuse to avoid war with the Americans. As Weed later noted with obvious satisfaction, “It was accepted abroad and at home as an able and well-timed appeal to the judgment, reason, and good sense of both countries.” Édouard Thouvenel, the French foreign minister, noted the dramatic shift in public mood: “There is a pacific current in the air,” and both the British and the Americans “will think twice before fighting.”52

Encouraged by these early signs of success but still in crisis mode, Bigelow and Henry Sanford huddled with Weed, Archbishop Hughes, and Dayton to work out how best to deploy Hughes as unofficial emissary from the Catholic Church. Napoleon III was sensitive to Catholic opinion in France, and his Spanish wife, Empress Eugénie, was an especially devout defender of the faith. It was decided Hughes should seek an interview with the emperor.

After getting the cold shoulder from a cordon of French officials, Hughes finally took it upon himself to write a private note directly to the emperor. It worked. On December 24, with the Trent crisis still unsettled, he met with Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, who took “great interest, and no small part” in the discussion, Hughes noted. He urged Napoleon to offer his good offices to arbitrate peace between England and America. The emperor begged off, saying the dispute involved non-negotiable matters of honor. After more than an hour Hughes left, uncertain as to which side France might take in America’s dispute with Britain and in its war with the South.53

“If I am not deceived,” the archbishop wrote Seward from Paris, “the feelings of what we would call ‘the people’” were not ill-disposed toward the United States, but “the tone of the papers here does not indicate any warm national friendship.” Lincoln, he pointedly told Seward, “is winning golden opinions for his calm, unostentatious, mild, but firm and energetic administrative talents.”

Hughes let it be known in Paris that he was planning an extended tour of Catholic Europe, which apparently worried Thouvenel, for the foreign minister pressed Dayton to reveal details of the archbishop’s travels and intentions. He was worried that Hughes might arouse Catholic interest in the American question and, of course, in the Union’s favor. Hughes went about his tour, spending several weeks in Rome visiting the pope and other Catholic officials, which at least gave the appearance of a welcomed visit from an unofficial spokesman for Catholic America. On his return journey to the United States the next summer, he came through London and then Dublin, where he was hailed as a returning Irish hero. The archbishop was helping to draw the Irish, and Catholic Europe generally, toward the cause of the Union.54

MEANWHILE, ON DECEMBER 5, THURLOW WEED, WITH SEVERAL COPIES of the Bigelow-Scott letter in his pocket, left Paris for London to try to calm Britain’s war fever. Weed’s reputation as Seward’s close confidant gave him access to the inner circles of power in England, and it also invested what he had to say with unusual, albeit unofficial, authority. He was also a consummate manager of politicians and the press, full of confidence of a sort that left young Henry Adams in absolute awe. Once Weed took into his hands “the threads of management,” Adams recalled, he did “quietly and smoothly all that was to be done.” Weed began by writing a soothing letter to the London Times and then deftly arranged meetings with the inner circle of the Palmerston government. He was invited to a dinner party with a group of military and political leaders at the home of Sir James Emerson Tennent. Weed likened it to “a war party of gentlemen.” One was a colonel about to leave for Canada with British troops who gave a lengthy toast dwelling “upon the duty of Englishmen to resent the insults to their flag.”55

10. Thurlow Weed, political mentor to William Seward who sent him and two clergymen on an unofficial public goodwill mission to Europe. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Returning to his hotel on Hanover Square, Weed found a friend waiting to tell him that a private audience with Earl Russell had been arranged for the next morning at the foreign secretary’s country estate, Pembroke Lodge. Weed took an early train and arrived before lunch at the foreign secretary’s country home. As usual, Earl Russell was frosty and led off the conversation with his view of things from what Weed described as a decidedly “ultra English standpoint.” Weed answered by delicately referring to the many instances of Americans being apprehended at sea before they resorted to war in 1812. He then smoothly turned the conversation toward the earl’s illustrious career in advancing the great Anglo-American Whig tradition, which they both had championed.56

Russell’s indignation seemed to moderate. He made it patently clear that he wanted to avoid war. He feared that Seward’s belligerence was such that he might actually welcome a foreign war. A story was circulating about Seward at a dinner party in Albany a year earlier, at which he allegedly told the Duke of Newcastle he looked forward to threatening Britain with war in order to rally political support for the Union at home. Seward denied any such comment, but the story corresponded with tales of his April 1 memo calling for war, and it offered further proof, if the British needed any, of the dangers of democratic mob rule. Russell understood that war with America would be a very dangerous business that would put at risk all of Britain’s possessions in North America and perhaps the Caribbean. It might also topple the Palmerston government.57

Russell proposed to Weed that Mason and Slidell be set free. Weed allowed that their arrest on board the Trent may have been ill-considered, but he explained how exasperated Americans were with these men who had resigned their seats in the Senate to “inaugurate and lead a rebellion.” “English noblemen had gone from the Tower to the block for offenses less grave than those which Messrs. Mason and Slidell had committed,” Weed observed drolly. Russell had no retort. Weed then suggested an arrangement by which Britain would demand “in a friendly spirit” the release of the prisoners, the United States would comply, honor would be served, and the drums of war would be silenced.

This came at the end of a tense hour that, to Weed’s mind, concluded with more sympathy than it began. The two men were called to lunch, and after the meal Weed saw Russell take his wife aside for a moment of private conversation. Then she invited Weed for a stroll in their garden. On their walk Weed asked about an unusual mound of about two or three feet. She told him to stand on top of it while she related a story: “You are now standing precisely where Henry VIII stood watching for a signal from the dome of St. Paul’s church, announcing the execution of Anne Boleyn” (the king’s second wife, who was beheaded in 1536 for high treason).

Resuming their walk, they passed a “mimic fortification” the children had built. Lady Russell paused, turned to Weed, and said: “Ladies, you know, are not supposed to have any knowledge of public affairs. But we have eyes and ears, and sometimes use them. In these troubles about the taking of some men from under the protection of our flag, it may be some encouragement to you to know that the Queen is distressed at what she hears, and is deeply anxious for an amicable settlement.” It was one of those cryptic, entirely unofficial, but no less important communications in the game of diplomacy that Weed took as a comforting signal. He left Lady and Earl Russell’s country home that day knowing that, for all the bluster in the press and over dinner tables in London, Britain was not going to war if the queen had anything to say about it.58

Queen Victoria, in truth, despised America and its democracy; it was her beloved husband, Prince Albert, who helped subdue the dogs of war that winter. Gravely ill with typhoid fever, he rose from his deathbed to soften the language of the demand Earl Russell was about to send to Washington. Albert died a short time later, on December 14, and the queen was stricken with inconsolable grief. There were still a few in the press beating the drums for war, but a somber spirit of mourning subdued Britain’s war fever that winter.59

It was not until January 2 that news of Lincoln’s Christmas Day decision to release Mason and Slidell finally reached London. The city was jubilant; the stock market soared. Everyone “but the confederates and the war party,” Charles Francis Adams wrote in his diary, “seemed to be relieved.”60

John Stuart Mill, a leading voice of liberal England, characterized the passing crisis poignantly: a cloud that had “hung gloomily over the civilized world” for a month had passed. Had America gone to war, it would have been “reckless persistency in wrong,” he wrote, but for Britain, “it would have been a war in alliance with, and, to practical purposes, in defence and propagation of, slavery.”61

THE TRENT CRISIS BROUGHT THE UNION TO THE BRINK OF WAR AND exposed the risks involved in Seward’s hard-power strategy. At the same time, it revealed the dangers of letting one’s enemies control the public narrative abroad. It also taught some timely lessons on the vital importance of the press and public opinion and on the urgency of having special agents, skilled in dealing with the press, on the ground and ready to put out fires. Bigelow’s and Weed’s adroit maneuvers at a time of peril proved critical in defusing the crisis. Archbishop Hughes’s and Bishop McIlvaine’s speaking tours also pointed the way toward a promising new path in semiofficial public diplomacy.

But the contest to win popular sympathy abroad would turn not on which side could spend more money, hire more pens, and otherwise control the public forum. What mattered more was what the Union had to tell the world about why it was fighting. After nearly a year of crisis, the questions Garibaldi posed the previous summer about the purpose of the war still loomed: Was the Union fighting only for its national survival, for territory and power? Or was there something more at issue, something that might matter to the world at large? If Americans would not address these questions forthrightly, there were foreigners who would.