The terror of the American name is gone, and the Powers of the Old World are flocking to the feast from which the scream of our eagle has hitherto scared them. We are just beginning to suffer the penalties of being a weak and despised Power.

—NEW YORK TIMES, MARCH 30, 1861

THE EUROPEAN DEBATE OVER THE FATE OF THE REPUBLICAN experiment was not restricted to rhetoric in parliamentary speeches or town hall political meetings. As soon as the secession crisis surfaced, the Great Powers of Europe seized the opportunity to reverse the advance of popular government in the Western Hemisphere and more, to take back lost empires and restore the authority of church and crown.

From Paris on March 10, 1861, Malakoff reported for the New York Times that the French and British were “filling out a powerful fleet of war steamers for the United States” and would sail with sealed orders, supposedly as observers of “the struggle which is soon to take place between brothers and friends in the United States.” The “ostensible errand” was to protect English and French subjects abroad, but Malakoff mused that the naval mission “may be intended as a sort of escort of honor for the funeral of the Great Republic.”1

From its nearby base in Cuba, Spain was also busy mobilizing men, ships, and matériel to patrol the Caribbean. It had a more decisive target in mind. Within two weeks of Lincoln’s inaugural, the Spanish launched an invasion and takeover of their former colony the Dominican Republic. Malakoff also reported intriguing rumors circulating in the Tuileries Palace that Louisiana, having “repudiated her allegiance to the Government of the United States,” gave France “the right to reclaim her former Colony.”2

Malakoff’s grim report in the New York Times projected the very foreign menace that Seward alluded to in his April 1 memorandum to Lincoln. Above all, Malakoff’s report from Paris gave proof that some insidious ideas were taking hold abroad, at least in the minds of government leaders: that the Union was dead, further fragmentation would follow, and the entire republican experiment was about to be dealt a fatal blow.

With the new Lincoln administration seized by the secession crisis, several Great Powers of Europe—Spain, France, and Britain, with support from Belgium and Austria—recognized their opportunities to reclaim lost American empires and shore up existing ones. Whatever power the United States previously had to enforce the Monroe Doctrine, it became a dead letter during the Civil War. While Britain nervously guarded its possessions in Canada and the Caribbean, Spain and France set out to conquer feeble Latin American republics.3

Spain seemed enthused by hopes for the return of imperial glory in the Americas, while France vowed to lead the global regeneration of the “Latin race” against the Anglo-Saxon Protestants. What came to be known as Napoleon III’s “Grand Design for the Americas” had been gestating since the 1830s and was unveiled in the 1860s as a bold new program of nationalist aggrandizement impelled by the transnational concept of “Latin” racial and cultural ascendancy.4

France’s Grand Design envisioned a Latin Catholic empire that would, in time, embrace all the failed Spanish American republics and include an alliance with the Empire of Brazil. It was the supreme expression of Napoleon III’s Bonapartisme revival, which in the fullness of its ambition encompassed everything from Baron Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris to the colonization of Algeria, the construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt, colonial expansion in Indochina (Vietnam), and, the grandest of all, the founding of a new Latin American empire radiating from Mexico. Napoleon III’s aim was nothing less than to create in France a major global power that spanned both hemispheres and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Nowhere did his ambitions reach higher, and fail more spectacularly, than in Mexico.5

The Grand Design owed much to Michel Chevalier, one of Napoleon III’s court intellectuals, an ardent French imperialist and devotee of historian Jules Michelet, who viewed Europe as divided into competing Latin Catholic and Teutonic Protestant races. During his travels in the United States and Mexico in the 1830s Chevalier recognized that similar divisions were being reproduced in the Americas, and always with unfortunate results for “Latin America,” a term he helped invent. While Anglo-American Protestants had established a thriving republic in the United States, Latin America, infected by democratic ideas of equality and liberty that were wholly unsuited to its traditions and temperament, had degenerated into what Chevalier described as “an impotent race without a future.” The regeneration of Mexico and all of Latin America would come either by means of an Anglo-American conquest or the beneficent tutelage of France as the ascendant leader of the Latin race. “Without France, without her intelligence, her elevated sentiments and her military power,” Chevalier wrote, Latin nations “would long since have been completely eclipsed.”6

Ideas about France as the redemptive leader of the Latin race and about Mexico as the geopolitical key to control of the Americas and the Pacific Ocean had evolved in answer to America’s doctrine of Manifest Destiny, which prophesied the inevitable spread of democracy and Anglo-Saxon culture. The Latin race was an imagined community of peoples of Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French origin bounded by a common Latinidad (Latinity) that was grounded in their similar language, Catholicism, and opposition to the Teutonic races of northern Europe and North America.7

Suddenly, America’s Civil War opened the way for France to fulfill its own manifest destiny in the Americas and to roll back the expansion of the United States. At its broadest conception, the Grand Design envisioned a Latin Catholic monarchical league dominating the Western Hemisphere from California to the tip of South America, with two powerful monarchies, Mexico and Brazil, forming the main axis and France and other allied European Catholic empires providing protection and guidance.8

More ominous for the United States was the idea that the success of Napoleon’s Grand Design depended on an independent Confederacy to serve as a buffer state between the United States and Mexico. A sensational pamphlet entitled La France, le Mexique et les États Confédérés was published anonymously by Michel Chevalier in 1863 and translated into English for New York Times readers that September. In it Chevalier, obviously with Napoleon III’s approval, blatantly announced that France’s purpose was to help the Confederacy win independence, thwart US expansion, and shield Mexico from US interference.9

The “monarchical projects directed against America do not stop” at Mexico, the New York Times alerted readers as early as February 1862. There were plots “openly talked of in the Continental Courts” to establish monarchies in the Rio de la Plata region encompassing Paraguay, Uruguay, and parts of Argentina and Brazil, as well as in the Central American republics of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and perhaps Guatemala and San Salvador. According to one report in Frankfurt’s Allgemeine Zeitung, several Italian monarchs recently deposed by the Italian Risorgimento were candidates for Latin American crowns. Brazil’s emperor, Dom Pedro II of the Braganza dynasty, was reported to be in full cooperation with these plans for the restoration of monarchy in his troubled Spanish American neighbors.10

Latin American conservatives much preferred the protection of France to dethroned Italians. In 1861 Ecuador’s Gabriel García Moreno, styling himself the enemy of “godless liberals,” invited France to protect his country from “the domestic disorder and anarchy . . . dishonoring and impoverishing the country” and against the “destructive torrent of the Anglo-American race.” Paraguay’s Francisco Solano López, assuming his late father’s role as dictator in September 1862, inquired of French officials whether European royals would welcome him as monarch of a López dynasty. That was when he first learned of plans by France, Spain, and Italy to install a single European monarch over the discordant Rio de la Plata region. Ramón Castilla, the republican president of Peru, predicted that Latin America was about to witness a “war of the crowns against the Liberty Caps.”11

THE CROWNS STRUCK THE FIRST BLOW AGAINST THE LIBERTY CAPS IN Santo Domingo in March 1861. Spanish officials in Madrid and Havana had been plotting with conservative forces in the Dominican Republic for months as the secession crisis ripened in the United States. The Dominicans had suffered an unhappy national life. They won independence from Spain in 1821, only to be taken over by their Haitian neighbors, who feared the reintroduction of slavery. Finally, in 1844 the Dominicans pushed the Haitians out and established an independent republic. But its seventeen years of independence had been plagued by foreign debt and wracked by internal strife that followed a familiar Latin American pattern: conservative white landowners, military leaders, and Catholic clergy pitted against liberal republicans in the middle class and peasantry, most of the latter former African slaves.12

Fresh off its conquests in Morocco, Spain was animated by a renewed sense of imperial grandeur. Ever since she ascended to the throne as an infant, Queen Isabella II had been challenged by the ultratraditional Carlists, who had no use for a female monarch and proclaimed Carlos VI as the legitimate heir to the throne. The Carlists waged war against her in the 1830s, again in the 1840s, and in 1860 mounted yet another failed revolt to oust the queen. Isabella II stood between two fires: reactionary Catholic legitimists, on one side, and liberal republicans, on the other.13

Spain’s burst of imperialist enthusiasm, Carl Schurz reported from Madrid in September 1861, was “calculated to tickle national vanity.” Courtiers flattered the queen by calling her the “second Isabel la Católica,” whose destiny it was “to restore the ancient splendors and power of the Spanish Monarchy.” Spain’s resurgence in the Western Hemisphere, Schurz warned Seward, “seems to have been for some time a favorite dream of the dynasty.”14

Spanish officials had long worried that the United States would seize the Dominican Republic and use it as a base of operations for taking over Cuba, the jewel in what was left of Spain’s imperial crown. So did the Dominican Republic’s conservatives, whose leader, the aging president Pedro Santana, had been secretly plotting with Francisco Serrano, the Spanish commander in Havana, to devise a plan to return their country to Spanish rule. According to plan, Santana fomented popular support for the takeover by whipping up fears of invasion, either by the United States or its dreaded Haitian neighbors. “Santo Domingo will be Haitian or Yankee,” Santana exclaimed.15

When Spanish officials in Madrid stalled out of fear that the United States would retaliate, Santana became frantic. On March 18, 1861, he forced the issue by holding a sham plebiscite and proclaiming the “unanimous consent” of Dominicans for a return to the Spanish Empire. The Spanish flag rose above the capitol, and Santana ordered a 101-gun salute. On signal two Spanish warships lurking offshore landed and disembarked soldiers to secure the capital. The island that Columbus had claimed for Isabel la Católica in 1492 was thus reclaimed by Isabella II to the glory of Spain.16

Madrid was stunned by the news and braced for retaliation from the United States. Leopoldo O’Donnell, the Spanish prime minister, worried that Americans might “forget their internal discords” and make war on Spain’s vulnerable American empire. But Gabriel García Tassara, the Spanish ambassador to Washington, assured his government that the Lincoln administration was far too distracted to take action against Spain. Spain’s “grand hour,” Tassara prophesied, “approaches again in America as in Europe.” “The Union is in agony, our mission is not to delay its death for a moment.”17

O’Donnell’s fear of America uniting against foreign incursions was exactly what Seward had in mind in his notorious April 1 memorandum to Lincoln. Though he might be faulted for exaggerating what he supposed to be the remedial effects of foreign war to disunion, Seward clearly grasped the more important truth that Spain’s aggression in Santo Domingo would open the door to more European incursions if it went unanswered. There were already signs of French cooperation with Spain, Seward warned. The next step would be the reinstatement of slavery over the entire island of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo, and Haiti.18

While Lincoln and the United States stood back, the republicans of Santo Domingo, many of them former slaves, took to the jungles to begin a fierce guerrilla war against what their April 1861 manifesto characterized as Santana’s plot to “crush the Dominican people under the colonial yoke.” One Dominican Republic leader, General José-Maria Cabral, sounded the alarm: “Tomorrow we will be slaves!” He enlisted Haitians to join them in a war to the death rather than submit to “slavery” under the Spanish occupation. The Dominicans also sent agents to Washington to urge the United States to stand up for its Monroe Doctrine, all to no avail. Seward refused to receive the desperate Dominican envoys for fear that any show of support might push Spain into the arms of the Confederates.19

The New York Times roundly denounced Spain’s effrontery. “Our domestic dissensions are producing their natural fruits.” Spain, feeling its “new-born power,” would never have dared such a move had it not been for the secession crisis. This was only the first step in that haughty empire’s desire “for resuming her position as a Power on the Western Continent.”20

SEWARD HAD NO IDEA THAT IN MADRID, THE US MINISTER TO SPAIN, William Preston, a Buchanan appointee from Kentucky, was using his last months in office to aid the Confederacy. Preston did all he could to convince the Spanish foreign secretary, Saturnino Calderón Collantes, that Southern secession was legal, justifiable, and an accomplished fact. The secession of the slave states was just the beginning, Preston informed him. Before it was over, all but a few of the northeastern states, those infected by “ultra fanatical” abolitionism, would come under the Confederate constitution, and Washington would soon become the capital of the reconstituted proslavery nation.21

Seward learned all of this from Horatio J. Perry, the loyal secretary of the legation in Madrid, who had the courage to report his superior’s treachery. Perry was married to Carolina Coronado, a popular Spanish writer and close friend of Queen Isabella II. Her literary salon brought Perry into close contact with Madrid’s intellectual and political leaders, which made him aware of but powerless to counter Preston’s insidious influence.22

“You cannot too quickly change the Legation at this Court,” Perry advised Seward in early May 1861. Preston had been “working on the aristocratical prejudices of Courtiers and army and navy officers against the United States” and cultivating “considerable sympathy for . . . rebels in the name of slavery and aristocratical privileges.” Preston also used his connections to plant a newspaper story, “rejoicing over the idea that the Confederate States have already entered upon the road” toward “a monarchical form of government.” Upon leaving Madrid, Preston took the occasion to deliver a grandiose speech to Queen Isabella II, extolling Spain’s recent triumphs in Africa and Santo Domingo.23

It was only later that Perry discovered Preston had also absconded with all of Seward’s instructions, which left the legation at great disadvantage for weeks. Preston returned home to serve in the Confederate army and later would be appointed Confederate envoy to the Empire of Mexico at Maximilian’s court. But it was in Madrid, while serving as US minister, that Preston performed his greatest service to the rebellion.24

Confederates were enchanted with the idea of alliance with Spain. It was the only European power still sanctioning slavery, and it was a vociferous opponent of America’s Monroe Doctrine. Robert Toombs, the first Confederate secretary of state, saw Spain as a natural ally and instructed Martin Crawford, a member of the Confederate commission in Washington, to meet with Tassara, Spain’s ambassador to the United States, and assure him “of the sincere wish of this Government to cultivate close and friendly relations with Spain.” Tell him, Toombs instructed, “that we are fully sensible of the importance of a great European Power possessing slave holding colonies in our Neighborhood.” Toombs also sent Charles Helm as envoy to Havana to establish friendly relations with local officials. After Helm finally arrived in October 1861, he reported cheerfully, “I find a large majority of the population of Havana zealously advocating our cause, and am informed that the same feeling extends throughout the island.”25

From London William Yancey, head of the first Confederate commission to Europe, urged Richmond to send an envoy to Spain, but it took until late August for Toombs’s successor, Robert Hunter, to authorize Pierre Rost, one of Yancey’s fellow commissioners, to go to Madrid. Spain alone, of all the Great Powers, “is interested through her colonies in the same social system which pervades the Confederate States,” Rost was instructed to point out to the Spanish government. The Confederacy, he added, would never “find any cause for jealousy or regret in the steady growth of the power and resources of Spain,” a delicate allusion to the takeover of Santo Domingo.

As for the South’s prior filibustering expeditions in Cuba, Hunter instructed Rost to explain that the only motivation for it was to maintain “something like a balance of power” with the North in Congress. An independent South would be relieved of all such concerns: “Of all the nations of the earth . . . there is none so deeply interested as Spain in the speedy recognition and permanent maintenance of the independence of the Confederate States of America.” Then Hunter added a menacing threat: Spain had the choice of either assisting what will be “a great friendly power” or facing in the future a “formidable” rival in the Caribbean.26

The capture and detention of Mason and Slidell and the entire Trent crisis forced the Confederacy’s initiative in Madrid to the back burner. Rost decided on his own authority to stay in Paris and did not get to Madrid until March 1862. In his interview with Calderon, the foreign minister, he found it difficult to persuade him that it was the North, not the South, that coveted Cuba. Rost did not help things when he began waxing eloquent about the Confederacy’s hopes for a great tropical empire in league with Spain and Brazil. Together the three nations “would have a monopoly of the system of labor, which alone can make intertropical America” prosper. “Nothing in the past could give an idea of the career of prosperity and power which would thus be opened to us.”27

THE SOUTH WOULD INDEED HAVE TO SHARE ITS DREAMS OF A TROPICAL empire if Europe’s Great Powers had anything to say about it. Spain’s takeover of Santo Domingo was the thin edge of the European imperialist wedge, the full dimensions and purpose of which soon became apparent. Having met with nothing more than feeble protests from a distracted United States, Spanish zeal for a Reconquista gained momentum. Mexico, once the heart of Spain’s American empire, loomed as the next prize.28

During its forty years of independence since 1821, Mexico had undergone fifty changes in government, and the breach between conservative and liberal factions had never closed. Paralleling the rise of the Republican Party in the United States, Mexico’s ascending Liberal Party had gained power in the 1850s. In what was known as la Reforma, the liberals introduced sweeping laws that vastly expanded the rights of citizens, limited the powerful grip of the Catholic Church on land and education, and culminated in the ratification in 1857 of a new constitution that liberals hoped would place Mexico on a firm republican foundation.29

Mexico’s conservatives refused to accept la Reforma, the 1857 republican constitution, and the new liberal government elected under it. Pope Pius IX denounced the reforms, which included confiscation of church lands and secularization of education. The pope compared Mexico’s liberals to Italian revolutionaries Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini, all godless enemies of the church. Mexico’s Catholic priests were instructed to deny absolution for any officeholder who had taken an oath to uphold the 1857 constitution. Conservative military officers defected and fomented a rebellion to oust the Liberals and vest power in the “church party.” In January 1858 Mexico was plunged into a bloody civil war known as la Guerra de Reforma.30

Mexico’s Reform War (1858–1861) foreshadowed the civil war about to break out in the United States. Though set in vastly different cultural contexts, both were instigated by conservatives rebelling against liberal republican electoral victories. After three years of war, Mexico’s republican forces finally routed the enemy army outside Mexico City and resumed power in January 1861, just as Mexico’s republican neighbor to the North was plagued by its own rebellion.

Benito Juárez, a lawyer from Oaxaca and a full-blooded Zapotec Indian, had played a leading role in la Reforma. He served as head of the supreme court of the first liberal government and then as interim president during the Reform War. Juárez would be called the “Abraham Lincoln of Mexico,” for both men rose from abject poverty, believed deeply in the rule of law, and became leaders of embattled republics against rebellious conservative forces, one trying to secede, the other trying to supplant the republic with a monarchy.31

Mexico’s conservative church party, as it was known, no more accepted the verdict of war than it had the verdict of the ballot box. No one was more zealous in his opposition than José María Gutiérrez de Estrada, who made it his life’s ambition to overthrow the republic and install a European monarch in Mexico. Born to a wealthy Creole Yucatán family in 1800, during the 1830s Gutiérrez de Estrada served briefly as Mexico’s minister to Vienna and became convinced that the only solution to Mexico’s tumultuous republic was an absolutist Catholic monarch on the Hapsburg model. His monarchist views were scorned in Mexico, however, and sometime in the 1840s he went into exile in Europe to begin a career as a self-appointed diplomat. For twenty years he lobbied the Catholic monarchs of Europe, not least Pope Pius IX, to aid his scheme for Mexico’s regeneration under a European prince.

While in Rome during the 1850s, Gutiérrez de Estrada met José Hidalgo, Mexico’s minister to the Papal States and soon converted him to the cause of monarchy for Mexico. After being transferred to Madrid, Hidalgo developed a close personal relationship with the vivacious widow of a Spanish grandee, Madam de Montijo, whose beautiful daughter, Eugénie, had married Napoleon III in 1853. Almost by chance, Hidalgo and Gutiérrez de Estrada had found a path to the inner circle of French power. Empress Eugénie would become an indispensable advocate for restoring Spain’s wayward former colony to glory under a Catholic monarchy.32

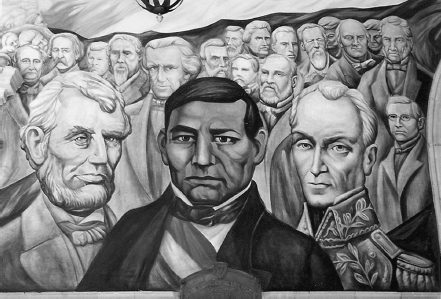

14. Benito Juárez and Abraham Lincoln, portrayed together in a mural by Aarón Piña Mora, Government Palace, Chihuahua, Mexico. (PHOTOGRAPH IN AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Back in Mexico Juárez’s republican regime was besieged by troubles. Though the Reform War had ended, in early 1861 outside Mexico City roving bands of brigands menaced the countryside, disrupted the economy, and obstructed transportation between the capital and the main port in Veracruz. Ravaged by war, deeply in debt to foreign creditors, Mexico would not be able to sustain payments on its international debts. In July 1861 Juárez announced the suspension of interest payments for two years. He was careful not to repudiate the debt itself, but this was all that was needed for the Great Powers of Europe to launch plans for intervention and bring to fruition the royalist plan Gutiérrez de Estrada and Hidalgo had been tirelessly promoting in Europe. With the United States descending into what appeared to be a prolonged internecine war, the door to Mexico was opened.33

AT THE END OF OCTOBER 1861 DIPLOMATS FROM SPAIN, FRANCE, AND Britain gathered in London to form the Tripartite Alliance. “Three States are combining to coerce a fourth [Mexico] into good behavior,” the London Times explained it, “not so much by way of war as by authoritative interference in behalf of order.” The alliance’s professed purpose was the recovery of Mexican debts, many of them owed to cronies of Napoleon III, chief among them the Duc de Morny, his illegitimate half brother. There were also demands of reparations for alleged harms to European citizens in Mexico. But the undeclared design of the French and Spanish governments was to overthrow Juárez’s republican government and install a European monarch in Mexico.34 The British were owed debts from Mexico, too, but they were wary of mad schemes to install a foreign monarch there. Against the advice of his ambassador in Mexico, Earl Russell decided to take part in the alliance, supposedly to check the imperialist plots of Spain and France.

Napoleon III’s plans for Mexico were no secret. In October 1861, days before the Tripartite Alliance meeting, Napoleon instructed his ambassador in London to explain to Palmerston and Russell that his aim was to establish a stable government in Mexico that would block American expansion. “The faction of Juárez will be overthrown, a national assembly will be convoked and a monarchy will be established.” Furthermore, the French emperor revealed to the British, “I have put forward the name of the Archduke Maximilian,” the younger brother to Emperor Franz Joseph of the Austrian Hapsburg dynasty. “A regenerated Mexico would form an insuperable barrier to the encroachments of the Americans of the North,” he noted. He sent a similar letter to Leopold I, king of the Belgians and the uncle and adviser of Queen Victoria.35

The Trent affair conveniently consumed Lincoln’s government during November and December 1861 while the Tripartite Alliance planned its invasion. Spain, with troops ready in Havana, eagerly led the way. Its armada of twenty-six warships steamed into the harbor at Veracruz on December 8, 1861. Six thousand infantry disembarked, while five thousand marines and sailors remained on board.36

General Don Manuel Gasset y Mercader, acting commander of Spanish expeditionary forces in Mexico, addressed his soldiers after they landed at Veracruz. “Soldiers: In every quarter the Spanish army meets with glorious remembrances of its valor and devotion. On these very sands exist the traces of Hernando Cortez, who with but a handful of Spaniards planted side by side with the standard of Castile, the ensign of the Cross and of Civilization, dazzling the world with his wonderful achievements. Today our mission is not less glorious; it is to exact from the Mexican Government satisfaction for insults heaped upon our flag.” Some of the Mexican onlookers may have known that Cortés in 1519 had ordered his ships burned to prevent retreat before leading his army of conquistadores toward the Aztec capital to pillage its treasure and enslave its people. What lay ahead for Mexico, and its invaders, nearly three and one half centuries later, none could yet foresee.37

The British and French fleets did not arrive until January 6 and 8, respectively. Britain brought seven hundred marines. The French landed two thousand regular troops, not counting five hundred Zouave soldiers with their dashing uniforms of bright-red trousers and tasseled red fez caps.38

“Ambition grows by what it feeds on,” the New York Times gravely intoned after the invasion began. Success in Mexico, it predicted, would encourage similar operations in other Spanish American republics. The allied powers were attempting “to establish this species of Monarchism on the ruins of the Democratic Governments founded in the Western World,” which would set off “a grand struggle between the votaries of Republicanism and the votaries of Monarchy.”39

THE TURMOIL IN MEXICO AND THE INVASION BY EUROPEAN POWERS created new challenges and opportunities for both the Union and the Confederacy to realign their foreign policies and redefine their messages to the world. For Confederates, hemmed in by the tightening Union blockade, Mexico would provide a vital lifeline to overseas shipments of essential supplies. Matamoros, a small port on the Rio Grande opposite Brownsville, Texas, became a bustling international center of trade. Most of the territory surrounding Matamoros was controlled by José Santiago Vidaurri Valdez, governor of the northern Mexican state of Nuevo León and the strongman who ruled the adjoining states of Coahuila and Tamaulipas. Known as the “Lord of the North,” Vidaurri distrusted Juárez and the republicans and spoke openly of his desire to secede from Mexico and perhaps join the Confederacy.40

The Confederates immediately recognized in Vidaurri an important ally whose protection of Matamoros would be vital to their success and whose secessionist sympathies might open a path to expansion southward. In May 1861 Robert Toombs dispatched José Agustín Quintero as “agent and special messenger” to the Vidaurri government. A Cuban-born intellectual and journalist, Quintero had fled Cuba after falling afoul of Spanish censors and made his way to the United States, where he became active in Democratic Party circles and formed a friendship with Jefferson Davis. Toombs instructed his new envoy to inform the Lord of the North that Southerners “feel a deep sympathy with all people struggling to secure for themselves the blessings of self-government.” Quintero was also authorized to arrange for purchase of arms and supplies through Vidaurri, a profitable reward for the Mexican chief’s loyalty to the rebel South.41

Vidaurri promised Confederates a back door around the blockade, but northern Mexico might also provide a back door for the Union army to invade their vulnerable western borders. Recognizing the vital importance of Mexico in the coming conflict, Lincoln had shrewdly appointed Tom Corwin as US minister there. The Ohio politician and former US senator arrived in Mexico City in June 1861 already something of a hero for his opposition to the war with Mexico and especially his famous 1846 Senate speech warning that Mexico would receive America’s invading armies “with bloody hands and hospitable graves.”42

Juárez and Mexican liberals looked to the United States as their protector against European—and Confederate—aggression. Corwin, reassuming his role as defender of Mexico, warned the Juárez government that the rebel South aimed to spread its empire of slavery southward. If Europe invaded Mexico, he told Seward, it would embolden the Southern rebels and probably “aid them in procuring their recognition by European powers.” Furthermore, European invasion would “so weaken Mexico that a very inconsiderable southern force could conquer in a very short time four or five Mexican States.”43

Corwin proposed to fend off threats to Mexico from Europe or the Confederacy by having the United States pledge a generous loan to Mexico to pay interest on its foreign debt and build up the depleted Mexican army. The “Corwin loan” was to be secured by territories in northern Mexico, which would undoubtedly have led to vast acquisitions of Mexican land by the United States, including the rich mining districts in Sonora. Due to wartime strains on the economy, however, the US Congress was in no position to pour money into Mexico. Besides, Seward feared that siding with Juárez might push France to ally with the Confederacy. Corwin’s gesture of support, nonetheless, benefited US-Mexican relations.44

AS ITS ENVOY TO MEXICO CITY THE CONFEDERACY SENT JOHN T. Pickett, a rough-hewn Virginian who had served the Buchanan administration as US consul to Veracruz and had a shadowy career in Caribbean filibustering adventures before that. He began his Confederate service as secretary to the Confederate commission to Washington in March 1861. He was a favorite of John Forsyth, one of the commissioners and a former US minister to Mexico under Buchanan. “Mexican affairs have suddenly come to be very interesting to the Black Administration,” Forsyth warned Jefferson Davis from Washington that March. Forsyth regarded Corwin as a traitor to his country, but he understood his appeal to Mexican liberals and advised Davis to respond swiftly by sending Pickett to Mexico.45

Forsyth asked Pickett to prepare a memorandum outlining for President Davis a Mexican strategy for the Confederacy. Pickett went to work crafting a policy that recommended by turns the Confederate overthrow of the Juárez regime and the wholesale takeover of the country. “So long as Mexico is governed, or attempted to be governed, by Mexicans alone,” it will never have a stable government. Foreign intervention “in one shape or another” is the only remedy to the corruption, “gross ignorance and superstition of the people (if Mexico may be said to have a ‘people’).” The United States, Pickett advised, would do all it could to “exclude us forever from our natural inheritance in that quarter.” The Union was likely to colonize Veracruz and close off access to the Confederacy in pursuit of its “long cherished design of surrounding African servitude by a cordon of flourishing free States.” The right Confederate special agent, Pickett advised Davis, could “place Yankee meddlesomeness and Puritan bigotry in their true light,” and if the “so-called Liberal party” in Mexico made terms with the United States that were “offensive to our dignity or interest,” the South must take sides with conservative leaders and help restore them to power. The “boundless agricultural and mineral resources” of Mexico and its Isthmus of Tehuantepec, thought to be a vital path between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, must remain open to Confederate expansion, Pickett further explained to Davis. “Southward is our destiny.”46

President Davis apparently liked these ideas and recommended that Toombs send Pickett to Mexico in May 1861. Toombs instructed Pickett to inform the Juárez government that the Confederacy welcomed a friendly alliance with its neighbor. Pickett was also instructed to emphasize the compatibility between the two countries, being “principally engaged in agriculture and mining pursuits” and with similar institutions of slavery and peonage. The instructions also included some blunt advice on bribing Mexicans: “A million or so of money judiciously applied would purchase our recognition by the Government.” Furthermore, “The Mexicans are not overscrupulous, and it is not our mission to mend their morals at this precise period.”47

WHEN PICKETT ARRIVED IN MEXICO CITY IN JULY 1861, HE ENCOUNTERED few friends. Corwin’s popularity in Mexico had, it seemed, closed off Confederate approaches to the Juárez government, and, in any case, Pickett soon managed to alienate all sides entirely on his own. His violent temper and ethnic bigotry, together with a weakness for strong drink, were a dangerous combination in a diplomat. Irritated by Corwin’s favorable reception in Mexico, Pickett lashed out in what he thought was private correspondence, hurling racist slurs against the Mexican people, their political instability, and their military incompetence. One especially intemperate dispatch threatened that the South would invade and imprison Mexicans, who would “find themselves for the first time in their lives, usefully employed . . . hoeing corn and picking cotton.”48

In another dispatch Pickett confided that he was purposefully deceiving Mexicans into thinking that an independent South would have no need to expand. He even let it be known that the Confederacy might consider a retrocession of territory stolen from Mexico in 1848 by the “late United States.” This, Pickett assured the home office in Richmond, was all a ruse aimed at neutralizing Mexico and confounding the Union. If Mexico persisted in favoring the Union, however, it would present “a golden opportunity” for Confederates to fulfill the “inevitable destiny which impels them Southward.”49

It never occurred to Pickett that the government he was insulting as inept might be intercepting his messages. Instead, when his dispatches went unanswered for weeks, he blamed it all on the incompetence of Mexican couriers, made copies of all his correspondence, and sent the copies by special courier through an agent in New Orleans. The agent, it turned out, was a Union spy. The entire packet was promptly forwarded to Seward in Washington.50

Pickett was, to say the least, in bad odor with the Juárez government, yet by late 1861 he hoped that the plans of the Tripartite Alliance to invade Mexico were about to tilt the game in his favor. “I little thought a few years ago ever to counsel a Spanish alliance,” he wrote to Richmond in November 1861, “but revolutions bring us into strange company.” The “Spaniards are now become our natural allies, and jointly with them we may own the Gulf of Mexico and effect the partition of this magnificent country.”51

Acting as usual on his own authority, Pickett decided to abruptly sever relations with the Juárez government and realign the Confederacy with Mexico’s church party and its European allies. In late November he swaggered into the office of an American named John Bennett and berated him for some alleged offense to the honor of a Confederate cabinet member’s wife. Then he assaulted Bennett, striking him with his fists and kicking him as he lay writhing on the floor. Mexican authorities threw Pickett in jail. He protested diplomatic immunity; they released him and then arrested him twice again. He finally fled to Veracruz. Only Pickett would have the gall to claim this was all a deliberate diplomatic tactic, but indeed that is what he reported to his astonished superiors in Richmond.52

In early 1862 Pickett was in Veracruz, the bay full of warships and the troops of Spain, Britain, and France. Here they were, Pickett jubilantly reported to a friend in Richmond in February, “like buzzards on the house top, over the defunct carcass of the Mexican Nation.” “The Monroe Doctrine, where is it?” At Veracruz he spoke with the French minister to Mexico, assuring him that the Confederacy welcomed any measures the European invaders might take that “would tend to give us a better neighbor and effectually exclude the Puritans from ever flanking us in this quarter.”53

IF PICKETT AND THE CONFEDERATE HIGH COMMAND WERE COUNTING on Spain as their “natural ally” and new southern neighbor, their hopes were soon disappointed. Spain had sent General Juan Prim as commandeer of Spanish troops in the allied invasion of Mexico. Prim had served with distinction in the Morocco campaign in 1859 and was a popular political figure, especially among the liberal Progressista party in Spain. The conservatives, Carl Schurz thought, were trying to “get rid of a very dangerous man,” and some even thought he might assume some leadership role in Mexico, perhaps as its new monarch. Prim was married to a wealthy Mexican woman whose uncle was Juárez’s finance minister. But Prim was a thoroughgoing republican who thought the church, not the liberal government, should be blamed for most of the country’s troubles and that it was absurd to impose a monarchy on the Mexican people whose traditions were strongly republican.54

Once Spain’s allies landed at Veracruz in early January 1861, a five-man commission representing the three countries, with Prim as chair, issued a lofty proclamation that denied any intention of conquest and promised that the allied powers “shall preside impassibly over the glorious spectacle of your regeneration, guaranteed through order and liberty.” It was when the commissioners tried to specify the terms of repaying the debt that the divisions among them appeared. The French insisted on demanding the full amount claimed, including many false and embellished claims made by French citizens. Prim and the British commissioners objected, and weeks of acrimonious wrangling ensued while the troops in Veracruz were wracked by illness, not least the vomito (yellow fever) that plagued the coast during the sickly season. The allied expedition had come four thousand miles, and its commissioners were now unable to agree on their objectives.

What ought to have been clear from the outset was that the French wanted to impose demands that would be impossible to satisfy and then provoke war with Mexico, march on the capital, bring Mexico’s republic to its knees, and prepare the way for a European monarchy. France’s allies were not prepared to go along with this, and when the French sent for more troops to Mexico and openly sided with the Mexican conservative leadership in early April 1862, Britain and Spain immediately withdrew from the alliance and pulled their troops out of Mexico.55

Now France faced Mexico alone. On the very day Britain and Spain withdrew from the alliance, April 9, 1862, the French notified Mexico that hostilities would begin. French forces, now augmented by reinforcements under the command of General Charles Latrille de Lorencez prepared to march on Puebla, the gateway to Mexico City. Acting as the political voice of the French Empire, the French minister to Mexico, Count Alphonso Dubois de Saligny, issued a proclamation that assured Mexico of France’s benign intentions toward the “sound part” of the nation whom they sought to rescue from the tyranny and anarchy of the Juárez regime. Speaking as one who knew the country and its people, Saligny confidently promised General Lorencez that the Mexicans would welcome their “regenerators” with flowers and that the priests of Puebla would celebrate their arrival with a Te Deum, the Catholic hymn of praise to God.56

French forces marched on Puebla where, early on the morning of May 5, General Lorencez ordered his Zouaves to assault Mexican troops entrenched on the hill outside the city. They met ferocious resistance from the republican army under the command of General Ignacio Zaragoza. The French were widely regarded as the finest infantry in the world, and Lorencez was not about to back down from what he considered an inferior army of Mexicans. After a bloody day of battle, the French were repulsed, and the screams of wounded soldiers filled the night as Lorencez led his army in retreat.57

Cinco de Mayo became a celebrated national holiday for Mexicans. Tragically, soon after his stunning victory General Zaragoza, the hero of the day, died of typhoid fever. His funeral procession in Mexico City drew massive crowds of admirers who cheered and threw flowers on the coffin, as it passed before them, raised on a catafalque drawn by a handsome team of black horses. The French flag was thrown contemptuously at the foot of the coffin, while above it flew a banner proclaiming Zaragoza el conquistador de los conquistadores.

An army of Mexicans, most of them mestizos, had defeated what was purported to be the most formidable armed force in Europe. The Mexican victory at Puebla did not turn back the French, but it delayed their conquest for one crucial year. It was an unspeakable humiliation for Napoleon III, and his government censored details about the battle in the press. But the cries from Puebla that terrible night in May echoed all the way to Paris.58

Napoleon III was undeterred. He decided to teach the Mexicans a lesson in French military superiority. He reinforced the French army in Mexico to more than thirty thousand troops and sent one of his most trusted commanders, General Elie Frédéric Forey, to lead them. In a secret letter to General Forey, Napoleon III carefully instructed him on how to carry out the subjugation of Mexico. Forey was to conquer the capital and then set up an Assembly of Notables from among the clergy and wealthy conservatives of the church party who supported the French mission. He was to empower this assembly to choose the form of Mexico’s future government and suggest to them, should they choose monarchy, that Archduke Maximilian of Austria was available. “You must be master in Mexico without seeming to be,” Napoleon III advised his general.59

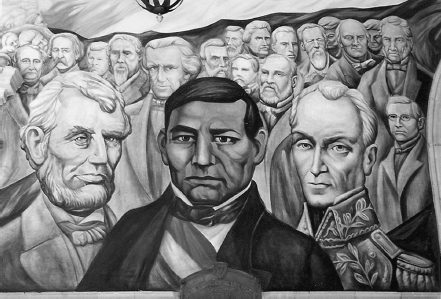

15. Cinco de Mayo, 1862, by Antonio González Orozco, Museo Nacional de Historia, Chapultepec Castle. (PHOTOGRAPH BY AUTHOR)

All pretense surrounding the Mexican debt and other alleged injuries and losses suffered by French inhabitants of Mexico was forgotten. France’s purpose, Napoleon explained bluntly to Forey, was to thwart the expansion and influence of the United States in Latin America. Mexico would become an “insuperable barrier” against US aggression and protect the possessions of “ungrateful Spain” in the Caribbean. Our “influence will radiate northward as well as southward” and create immense markets for French commerce and materials for its industry. “We shall have given back to the Latin race on the other side of the ocean its force and its prestige.”60

A little more than one year after their inglorious defeat at Puebla, the French made their triumphal entry into Mexico City in early June 1863 as Juárez and his republican forces retreated. Forey had no trouble filling the Assembly of Notables with reliable generals, Catholic clergy, and landowners. On July 10, 1863, with near unanimity and all according to script, the assembly declared Mexico a monarchy and elected to offer the crown to Maximilian. In case Maximilian refused, they agreed to let Napoleon III choose another prince to fill Mexico’s throne. The notables also decided to send a delegation to present the offer to Maximilian in Austria.61

Mexico’s conservatives embarked on their monarchical experiment in July 1863 just as their Confederate counterparts to the north met with stunning defeats at Vicksburg and Gettysburg. Juárez and his embattled republican followers hoped that the Union’s eventual victory might yet rescue them, if only they could hold out long enough against the Mexican monarchists and their French protectors.

It seemed incongruous to choose an Austrian prince to lead the regeneration of the Latin race in Mexico, but in the cunning mind of Napoleon III this played perfectly into his design for French dominance in Europe. He had adopted Italy as something like a client state during its Risorgimento. Since 1849 French garrisons had defended Rome and the Papal States, and Napoleon III could not risk the furor of Catholics by abandoning the pope to the likes of Garibaldi. But he also needed to placate Italian nationalists who wanted to complete the Risorgimento and make Rome the capital of a united Italy. In 1859 Napoleon III deployed French forces to northern Italy to help oust the Austrians from Lombardy, which had been governed not incidentally by Archduke Maximilian. That left Venice still in the hands of the Austrians, and Napoleon III expected growing pressure from Italy to go to war with Austria again.

Archduke Maximilian had proved himself an able administrator of Lombardy. By Napoleon’s calculation, having the younger brother of Hapsburg emperor Franz Joseph on one’s side in Mexico might make it easier to acquire Venice without another war. “I have thought it in good taste,” Napoleon III coyly put it in a letter of instruction to his ambassador in England, to propose “a prince belonging to a dynasty with which I was recently at war.” There were other calculations in play as well. Maximilian’s wife, Charlotte, was the daughter of Leopold I, king of the Belgians and confidant of Queen Victoria. Besides, the Hapsburg dynasty was Catholic and among the most prestigious in Europe. The Mexican monarchists, notably Gutiérrez de Estrada and José Hidalgo, had already vetted and approved Maximilian. As Napoleon III saw it, in one stroke Maximilian would bring in multilateral support from France, Austria, Belgium, Britain, and not least Mexico.62

Mexico’s republicans worked frantically to arouse world opinion against the French intervention. Matías Romero, Juárez’s ambassador to the United States, proved unusually adept in appealing to the American public. He was only twenty-three when he began diplomatic service in Washington. After the 1860 election determined Lincoln’s victory, he rushed to Springfield to urge the president-elect never to allow Europe to build a monarchy next door. At the end of 1861, when the allied invasion began, the young diplomat grew impatient with the Lincoln administration’s unwillingness to defend Mexico and stand behind the Monroe Doctrine, and he began working outside normal channels of diplomacy, making direct appeals to the American public. A true master of public diplomacy, with limited resources Romero performed the work of dozens, writing thousands of letters, and launching Spanish-language newspapers. In addition, he organized a vast network of Mexico clubs through which he raised money to send arms to Juárez and publish pamphlets alerting Americans of events in the imperiled republic to their south.63

Romero also staged well-publicized banquets with celebrity guests, then published the proceedings and sent them out to US congressmen and other influential figures. Some were staged at Delmonico’s, the famous New York City restaurant. Romero hired a band that played lively Mexican tunes interspersed with “Yankee Doodle” and “Hail Columbia.” Elaborate eight-course dinners were punctuated by dozens of spirited toasts and speeches denouncing the French and saluting the heroic struggle of Juárez and the republicans.64

There were two rebellions in North America, Romero relentlessly reminded Americans, and both were rooted in the same antipathy toward democratic ideals. The church party in Mexico and the slaveholders in America both called upon the monarchical empires of the Old World to sustain their cause. The French invasion and the Southern rebellion were both “parts of one grand conspiracy” in which the sponsors of absolutism and slavery “make common cause and strike a united blow against republican liberty on the American continent.” The enemies of republicanism, Romero warned, must be defeated in Mexico and America before either republic would be safe.65

16. Matías Romero, the Republic of Mexico’s ambassador to Washington. (NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

MAXIMILIAN WAS POOR MATERIAL FOR THE HARD BUSINESS OF RULING Mexico. He viewed himself as an enlightened aristocrat, an advocate of progress who disdained reactionary absolutists, whom he referred to as “Mandarins.” As a boy of fifteen, he witnessed with undisguised horror the violence of the Revolution of 1848, which forced his father to abdicate and brought his older brother to the throne. The memory of those days left him convinced that monarchs must win the loyalty of their subjects out of respect, even love, not fear. As one of his conditions for accepting the throne in Mexico, Maximilian insisted upon some popular ratification of the Assembly of Notables’ choice. The French complied early in 1864 by organizing a sham plebiscite in which leading citizens in every village were compelled to sign a petition endorsing the election of Emperor Maximilian. He came to Mexico naively believing he was the people’s choice.66

Maximilian finally decided to accept the throne, and in April 1864 a Mexican delegation officially offered the crown to him at his magnificent Miramar Castle, overlooking the sea near Trieste. According to some, it was Princess Charlotte who wanted nothing more than to be a queen and led her husband to accept the doomed “cactus throne” in Mexico. They were a couple starring in a romantic tragedy. She was not yet twenty-four, and he was only thirty-one years old that spring of 1864. He was tall, with deep-blue eyes that some described as dreamy. His thinning light-brown hair was parted in the middle, as was his flourishing beard. The day the Mexican delegation arrived, he dressed in his splendid blue Austrian admiral’s uniform, while Charlotte wore a pink dress with a brilliant diamond tiara adorning her dark-brown hair. The head of the Mexican delegation, addressing them in French, offered the throne of Mexico to Maximilian, who accepted in his well-practiced Spanish. ¡Viva Maximiliano, Emperador de Mexico! the delegation cheered; ¡Viva Carlota de Mexico! Outside, the flag of Mexico was raised above Miramar and canons on the Austrian warship docked in the Trieste harbor fired a twenty-one-gun salute.67

The US minister to Austria, John Lothrop Motley, wrote to a friend that Archduke Maximilian “firmly believes that he is going forth to Mexico to establish an American empire and that it is his divine mission to destroy the dragon of democracy and re-establish the true Church the Right Divine. . . . Poor young man!”68

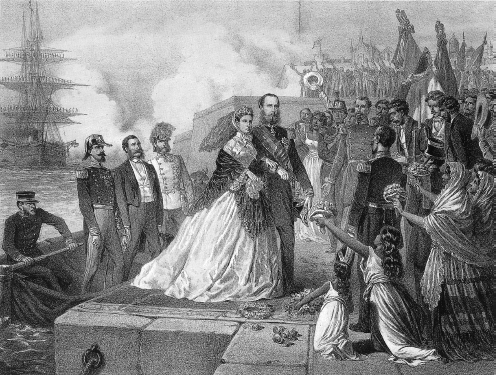

On their way to Mexico, Maximilian and Charlotte stopped at Rome for the blessing of Pope Pius IX. Then they sailed across the Atlantic in the Austrian ship Novara, arriving in Veracruz at the end of May 1864.

Meanwhile, Matías Romero had helped persuade Republicans in Congress to officially denounce “the deplorable events now passing in Mexico” and declare in April 1864 that the United States would never “acknowledge any monarchical government, erected on the ruins of any republican government in America, under the auspices of any European power.” In France Napoleon III’s government had done all it could to keep the French public from learning about US antagonism toward his Grand Design. From Paris Malakoff reported that news of the congressional condemnation fell “like a bomb in time of peace.”69

Maximiliano and Carlota, as they would be known in Mexico, were welcomed in Veracruz by a lavish official reception, but the streets were empty and the few Mexicans they encountered maintained a stony silence as they passed. Before the royal couple came through Orizaba, Juárez supporters had distributed small sheets of paper exclaiming, “Long live the Republic, long live Independence, death to the Emperor.” When they arrived in Mexico City, however, French troops saw to it that the streets were lined with cheering crowds. Mexico’s monarchical experiment had begun.70

17. The Arrival of Maximiliano and Carlota in Veracruz, 1864, as imagined by Vienna artist V. H. Gerhart. (COURTESY ERIKA PANI)