People at a distance have discerned this better than most of us who are in the midst of it. Our Friends abroad see it! John Bright and his glorious band of English Republicans see that we are fighting for Democracy or for liberal institutions. . . . Our enemies too see it in the same light. The Aristocrats and the Despots of the old world see that our quarrel is that of the People against an Aristocracy.

—JOHN MURRAY FORBES, UNION SPECIAL AGENT, SEPTEMBER 8, 1863

BY THE END OF THE FIRST YEAR OF WAR, THE LARGER IDEOLOGICAL debate over the republican experiment that enveloped the American question and the incursions by European powers in the American hemisphere made it clear to all that this was more than just another civil war. Events, and the interpretation of those events, forced diplomats and politicians on both sides to reconsider their message and the audience for that message. Foreign governments would continue to calculate the best course forward in light of their national interests as measured by commercial profits and geopolitical strategy. But for their citizens, the American question had become part of a much bigger debate about forms of government and systems of labor, and about their future.

Though the Union and the Confederacy were not always clear or forthright about what they were fighting for, foreign politicians, journalists, and intellectuals translated the meaning of events for themselves and reached their own conclusions about what was at stake in the distant war in America. The most lucid translations often came from the dissenting voice of the political opposition or the reformers who made the question about America’s future one about their own.

“What principle is involved in the American civil war?” Europeans kept asking George Perkins Marsh, America’s minister to Italy. Government officials were willing to honor a war waged to sustain “constitutional authority” and “established order against causeless rebellion,” Marsh admitted, but the broad public found these matters rather uninspiring. Public support abroad, he warned Seward, depended on the belief that the war “is virtually a contest between the propagandists of domestic slavery and the advocates of emancipation and universal freedom.” If the war proved to be protracted, he added, “I am convinced that our hold upon the sympathy and good will of the governments, and still more of the people of Europe, will depend upon the distinctness with which this issue is kept before them.” If there were any concessions made to Southern demands on slavery, if the Union failed to demonstrate “at least, moral hostility to slavery,” Marsh told Seward as bluntly as he dared, “the dissolution of the Union would be both desired and promoted by a vast majority of those who now hope for its perpetuation.”1

As it moved into its second year, the American Civil War was about to become a pitched battle for public opinion abroad. This contest for public sympathy was fought on mostly uncharted ground, and both sides improvised as they went. Union agents abroad learned a vital lesson early on: they would need to enlist foreign intellectuals, journalists, reformers, and politicians who were eager to tell their people in their own language—and tell Americans—what they thought this war was really about, or ought to be about.

ONE OF THE FIRST FOREIGN INTELLECTUALS TO TAKE AN UNEQUIVOCAL stand in favor of the Union was Count Agénor de Gasparin, whose book Un grand peuple qui se relève appeared in Paris before the war even began. Malakoff alerted his New York Times readers as early as May 1861 that “there is in France one man at least who does not regard the American nation as going so rapidly into a decline.” In Gasparin’s view, instead of committing national suicide, the election of Lincoln heralded an American resurgence. The Americans “have raised themselves up from the barbarism into which the slave power was drifting them, and placed themselves on nobler and more civilized ground.” This was a reveille, a summons to battle, Gasparin announced. La question d’Amérique was a question Europeans must answer. Thanks to reviews in key French journals, Gasparin’s book opened up a public debate on the American question in Europe and just at the time government officials and journalists seemed willing to accept the separation of the South as a fait accompli.2

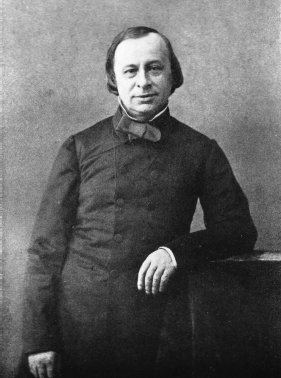

18. Agénor de Gasparin, the first European voice in support of the Union. (PERMISSION OF LA SOCIÉTÉ DE L’HISTOIRE DU PROTESTANTISME FRANÇAIS)

Gasparin was a liberal Protestant politician, intellectual, and reformer from a prominent political family that originated in Corsica. Born in 1810, he had served in the Chamber of Deputies during the “July monarchy” of King Louis Philippe. He wrote prolifically as an advocate of religious freedom, prison reform, and the abolition of slavery. After 1848 Gasparin refused to support Louis-Napoleon and went into self-imposed exile in Switzerland. He became a supporter of the Orléanist faction, those advocating the restoration of Louis Philippe’s grandson the Comte de Paris to the throne.

In September 1861, exactly at the time when Giuseppe Garibaldi was entertaining the invitation to serve the Union army, the Comte de Paris and his brother the Duc de Chartres, known as the Orléans princes, were visiting America with their father, the Prince de Joinville. The Orléans princes actually enlisted in the Union army and were attached to the command of General George McClellan. The Northern press was enthralled by these dashing young foreign princes fighting for the Union. Back in France, however, Louis-Napoleon, now Emperor Napoleon III, was irritated that these liberal pretenders to the throne were garnering such celebrity abroad, and he regarded all the fuss over them as an American insult. The Orléans princes in America and Gasparin from Switzerland were urging liberal France to embrace the Union cause, partly to bedevil their nemesis, Napoleon III, but also to renew the Franco-American bond of friendship.3

“Let us enlist,” Gasparin summoned Europeans. This was Europe’s conflict, too. “One of the gravest conflicts of the age is opening in America.” “It is time for us to take sides.” Now was the time, he wrote, “to sustain our friends when they are in need of us; when their battle, far from being won, is scarcely begun.”4

His was the first European voice to proclaim without equivocation that, whatever Americans said about their war, at the heart of it was the greatest moral issue of the nineteenth century: slavery. How could it be denied? Southern rebels had inscribed slavery into their constitution, and their vice president, Alexander Stephens, had proclaimed slavery la pierre angulaire of their nation.

For most Europeans the legality of secession and the blockade, or even the stress on cotton manufacturing, held little popular interest. This was a moral struggle on the very highest plane of Christian ethics, Gasparin declared. He freely admitted he was viewing it all “from a distance” and that he had never been to America, but insisted that “there are things which are judged better from a distance than near at hand.” The good news, in Gasparin’s view, was that America was about to rise up (se relève) against the slave power. Friends of progress in Europe must stand by their friends. “Let others accuse me of optimism; I willingly agree to it,” he wrote. “We need hope.”5

Americans needed hope too, and they found it in Gasparin’s distant voice telling them that their struggle to preserve the Union mattered greatly to the world. As one admirer put it, “He leaped manfully to the work of setting us right in the sight of Europe.”6

Thanks to Mary Louise Booth, a young New York writer, Gasparin’s message of hope became accessible to American readers during that summer of despair in 1861. As a child growing up in a small town on Long Island, she had devoured books in her father’s ample library. Her maternal grandmother was French and had come over after the French Revolution. But Booth learned most of her French from diligent study of a grammar book and then mastered German by the same sheer determination. She taught at her father’s school in Brooklyn for a while, and at eighteen, with what her biographer described as a gritty “disdain for obstacles,” she moved to Manhattan, rented a small room, and immersed herself in the world of ideas and writing. She became a passionate abolitionist and feminist and took an active part in the woman’s rights movement along with her friend Susan B. Anthony.7

Working by day as a seamstress and later as a secretary for a physician, at night Mary Booth wrote pieces for the New York Times and other publications. She translated French and German technical manuals to help pay the rent. Then in 1859 she published a history of New York City that was a popular success. Her publisher wanted to send her abroad to write similar books for all the European capitals. She was thirty years old and living on her own, and her writing career had suddenly opened an exciting new world of possibilities.8

Then the war came and changed everything. Booth watched her younger brother enlist and for a time she considered serving as a nurse. But when Gasparin’s book appeared that spring, she found her calling; she would serve the Union with her mind and her pen.9

From Paris Malakoff had told New York Times readers about Gasparin’s book and urged that it be translated “in order that the American public may see what an intelligent foreigner, who is our friend, says of us.” It must have been Mary Booth who wrote the laudatory review of this “remarkable French book” for the New York Times in late May, not long after Malakoff’s notice. Booth believed that the book deserved a full translation, which she proposed to do for Charles Scribner, a prominent New York publisher. Scribner was worried that the war would be over soon, and he agreed to publish it under one condition: it would have to be ready for press in a week.10

19. Mary Louise Booth, an industrious translator who gave French pro-Unionists a voice in the English-speaking world. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Gasparin’s book ran more than four hundred pages. Booth took it home to her small apartment, and with her desk lamp burning deep into the night she worked twenty hours each day. At the end of the week, with a few hours to spare, she brought Scribner a slightly abridged English translation ready for publication.

The Uprising of a Great People went to press in June 1861 and quickly gained a large audience. Booth’s translation appeared just as demoralizing news from Europe was pointing toward early recognition of the Confederacy by Britain or France, and not long before London Times correspondent William Howard Russell’s disturbing reports on Union disarray and Southern resolve were appearing in the American press in that miserable summer of First Bull Run. Gasparin’s prophecy of national moral regeneration struck an opposite chord, and none too soon.

Charles Sumner, the Republican leader in the Senate, declared that Gasparin’s book—and Mary Booth’s translation, he might have added—was “worth a whole phalanx in the cause of human freedom.” An anonymous reviewer for the North American Review was ecstatic about this unknown French voice that “comes to us from beyond the ocean.” “We have as yet seen no American publication of any kind which can bear comparison.” A man who had never set foot on American soil had grasped more fully than most Americans the real meaning of their conflict.11

An inexpensive abridged edition of Uprising was published in London in early July. Lest anyone miss Gasparin’s point about slavery being at the heart of the matter, the British publishers added an appendix with extracts from Alexander Stephens’s notorious Cornerstone Speech. A Dutch edition, Een Groot Volk Dat Zich Verheft, appeared later in the year. In the United States a book Charles Scribner had feared would be dated before long went through four editions in 1861 alone; it would go through seven editions in France. The second American edition, published during the Trent affair, appended Gasparin’s special plea for peace, translated from his essay for the Paris Journal de Débats. In early 1862 Booth brought out a “new American edition” in which Gasparin made several small corrections and added a new preface. “I believed then in the uprising of a great people,” Gasparin told his American readers. “Now I am sure of it.”12

Meanwhile, Gasparin was working on a stirring sequel that appeared in Paris in March 1862. Galley proofs of L’Amérique devant l’Europe were sent to Mary Booth for immediate translation, and Scribner brought it to press in the summer of 1862 as America Before Europe: Principles and Interests.13

Gasparin had written to President Lincoln during the Trent affair, urging him to find a way to end the crisis peacefully, and the two men began a correspondence. Mary Booth sent President Lincoln a copy of Gasparin’s second book, to which he responded with a brief note of thanks. But he may not have realized just how indebted the Union was to her for helping Gasparin and other French authors tell the English-speaking world what was at stake in America’s war.14

“There is no such thing as distance today,” Gasparin wrote in his second book. “The solidarity which today unites all peoples is so great, that nowhere can any question be agitated to which we may say that we are strangers.” Gasparin’s main point, as before, was that this was not just an American quarrel over petty local matters. “It is the house of our neighbor that is burning.” “If liberal institutions come out victorious from a tempest where many hoped to see them perish . . . will this be nothing?”15

GASPARIN’S BOOKS ON THE AMERICAN QUESTION REOPENED A European debate that seemed to have closed around the assumption that separation of the South was irreversible, regardless of the moral issues involved. When John Bigelow, Lincoln’s new consul to Paris, arrived in September 1861, he was dismayed to learn that the public sympathy of Europe “at court in the press in the clubs and in general society, was very largely with the insurgents.” In the French Corps législatif, only Jules Favre and his stalwart clique of republicans, Les Cinq (the Five), as they were known, dared oppose the government and raise their voices for the Union. Bigelow’s job was to do all he could to set the public mind in the right direction. Thanks to Gasparin, he found help among a number of France’s liberal politicians and intellectuals.16

In early October the highly respected Parisian publication Journal des Débats ran a lengthy essay, “La guerre civile aux États-Unis.” Ostensibly a review of Gasparin’s first book and a book by Louis-Xavier Eyma, the review provided French readers with one of the first critical examinations of France’s position on the American question. The author was Édouard-René Lefèbvre de Laboulaye, a professor at the Collège de France whom Bigelow recognized as France’s leading authority on American history and constitutional law.17

Malakoff was also impressed by Laboulaye’s essay, and he translated key passages for New York Times readers. “There has been nothing published in Europe showing so thorough an intelligence of all the aspects of the question,” he wrote. These views, Malakoff thought, “cannot fail to exercise the most beneficial influence on European opinion.”18

“We are not mere spectators of that civil war,” Laboulaye told Débats readers. “It is not merely our commerce and our industry that are at stake; the grandest problems of politics are up for solution.” What if the South wins independence? he supposed. “That act signalizes the advent into Christendom of a new society that makes Slavery the corner-stone of the structure” (another reference to Alexander Stephens’s infamous speech). And if “the South wishes to reopen the Slave-trade” or “threatens to invade Cuba or Mexico,” what will Europe do? Laboulaye pointedly reminded the French of the friendship forged with the United States during the American Revolution, when they joined in arms against the English and German Hessians. “Since that epoch, so glorious for both countries, France has remained the sister of America. This is a noble heritage, which we must not repudiate.” France must be the “ally of liberty.”19

20. Édouard Laboulaye, professor of history and law at the Collège de France, who spoke out for republicanism in America and France. (JOHN BIGELOW, SOME RECOLLECTIONS OF THE LATE ÉDOUARD LABOULAYE)

Bigelow was greatly impressed by Laboulaye’s “spirit of cordial sympathy with the North,” but “what surprised me more,” he later recalled, was Laboulaye’s “singularly correct appreciation of the matters at issue.” Bigelow understood the French well enough to know they would not welcome Americans trying to “educate” them on the proper view of America’s crisis. What was needed instead were French authors like Laboulaye to make the Union’s cause the cause of France. He immediately wrote to Laboulaye, complimenting him on the essay and asking to meet with him. Laboulaye replied that he would “be happy to serve in any way a cause which is the cause of liberty and justice.”20

Visiting Laboulaye at his home at 34 rue Taitbout in Paris, Bigelow was shown into “rooms crowded with books and numerous tables groaning under all the apparatus and teeming with the confusion of active and prolific authorship.” Bigelow was himself a scholar and felt completely at home with intellectuals such as Laboulaye. He gazed at the “curious and rare engravings” on the walls and dozens of books on American history and government. Soon a middle-aged, diminutive man entered the room, his thin hair smoothed against his head and framing an olive-colored face. He was dressed in what Laboulaye must have imagined to be the style of a common American, with a “high-necked Republican tunic of gray or black, with a thin line of white at the top.” Bigelow later mused that it gave Professor Laboulaye a “slightly clerical appearance.”21

During the 1850s Napoleon III’s repressive censorship had forced Laboulaye to keep a low profile. Historian Jules Michelet, Laboulaye’s colleague, had been fired for offending government censors. Laboulaye had become terrified of lecturing in public on American subjects. For a time he switched to teaching ancient Roman law. But when the crisis came in America in 1860, he returned to teaching his first love.22

Mary Booth described Laboulaye as le plus américain de tous les Français (the most American of all the French). Like Gasparin, he had never visited the United States. For Laboulaye, the Great Republic was an abstract ideal, a counterpoint to despotism and revolutionary tumult in France. In America he saw a successful, functioning model of self-government and an inspiration for France to resume its own republican experiment. He never tired of telling his students that since 1789, France had gone through fourteen constitutions and ten revolutionary changes of government, while America remained peaceful and prosperous under the same constitution—until now, his students must have thought.23

Laboulaye’s lectures began drawing large crowds of students, foreigners, workers, and political reformers. Lines formed outside his lecture hall. “Until now I have lived and spoken in an honorable solitude, and for a small circle of devoted friends,” Professor Laboulaye announced to his students one day. Now France needed “ideas that constitute the grandeur of man,” and he admitted to great joy at being part of this “general reveille.”24

In August 1862 Laboulaye wrote another two-part essay for Débats, a review of Gasparin’s second book, L’Amérique devant l’Europe. Again, he used the occasion to offer an extended critique of French policy on America. Bigelow told Laboulaye that he thought these essays “will place Europe as well as the United States under permanent obligations to their author,” and they “should enjoy a wider circulation.” He asked Laboulaye’s cooperation in preparing the essays as a pamphlet for general distribution at Bigelow’s expense. Laboulaye agreed, saying, “I am completely at your disposal. I shall be charmed to serve a cause which is the cause of all the friends of liberty.”25

Within days Laboulaye delivered an expanded essay running more than seventy printed pages. He ingeniously added appendixes documenting the French-American alliance in 1778 and Napoleon I’s 1803 epistle to the French regarding their traditional enemy across the English Channel. In ceding Louisiana, Napoleon I explained, “I strengthen forever the power of the United States, and give to England a rival upon the sea, which sooner or later shall abase her pride.” It was a clever swipe at Napoleon III, Napoleon le Petit, as Victor Hugo had dubbed the emperor, who blustered about his grand designs for Bonapartisme yet betrayed his uncle’s legacy and France’s historical friendship with America.

Laboulaye’s pamphlet gave what Bigelow called “popular expression and currency” to three key points. First, the South’s aim of “perpetuating and propagating slavery . . . was the true cause of the revolt.” Second, secession was not a lawful constitutional process, and the rebellion had nothing to do with the South’s rights having been violated. But Laboulaye’s third point was most critical: French commercial and geopolitical interests depended on the success of the Union, not the South.26

Bigelow saw to it that the pamphlet, Les États-Unis et la France, was delivered to each member of the Institute of France (a prestigious academic group), the entire membership of the Paris bar, every foreign diplomat residing in Paris, prominent statesmen throughout Europe, and all the leading journals in Europe. “The effect of it was far greater than I had ventured to anticipate,” Bigelow later recounted with satisfaction. “Friends of the Union multiplied and those who had been discouraged and silent before were now emboldened to come forward and confess their sympathy and their hopes.” The Journal de Débats, which had been vacillating on the American question, also changed its editorial policy and gave over its columns on American matters to those who supported the North. An abridged English version of Laboulaye’s essays was made available to American readers by the Boston Daily Advertiser in October 1862. It was a “masterpiece,” Charles Sumner exclaimed. “Nothing better has been produced in Europe or America by the discussion of the war.”27

Laboulaye, the quiet, diminutive professor, suddenly discovered a whole new audience for his work, and with it a renewed conviction to be heard. He continued to lend his valuable pen to the American cause, but it was America as a model for French reform that interested him most. The next year he came out with a witty fictional novel, Paris en Amérique, which he published under the pseudonym “Le Docteur René Lefebvre” and added in jest an absurdly long list of bogus international affiliations. The novel featured a Parisian who, in an extended dream, became magically transformed into an American in New England. The astonished Frenchman found himself in a country whose government actually protected freedom of religion and speech. It was Laboulaye’s highly idealized image of America and, of course, a satire on France’s oppressive Second Empire.

Mary Booth translated Laboulaye’s novel for eager American readers as Paris in America, and it soon resonated with audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. The book went through thirty-four editions in French and eight in English. It sold twelve thousand copies by the end of 1863 alone. Accustomed to scholarly writing for a narrow audience, Professor Laboulaye was ecstatic with the success of his fanciful “extravaganza.” “Artisans read my book in a loud voice at their working places,” he gushed to a friend, and it has “done more for my name than twenty-five years of serious study.”28

Laboulaye continued to translate the American question, always underscoring the common ideals France and America shared as champions of liberty, equality, and fraternity. In Laboulaye, John Bigelow discovered a powerful French voice for the Union. And in la question amércaine, Professor Laboulaye found the courage to trumpet a reveille for republicanism in France.29

THE CONFEDERACY WOULD ALSO ENLIST NATIVE AUTHORS, ENCOURAGING those who by conviction favored their cause. But in contrast to the Union, the Confederates generally preferred to control the message and get their own story before the foreign public. Their caution stemmed from a persistent distrust of antislavery sentiment abroad, and it was vindicated in part by their experience with James Spence, the Liverpool businessman who stepped forward entirely on his own and volunteered as Britain’s most vigorous champion of the South.

Spence was in his mid-forties, with good experience in business and government affairs and a gift for polemical writing. Things had gone very badly for him during the panic of 1857, when several American firms that owed him money failed. His motives for favoring the South were both pecuniary and ideological. He had traveled extensively in America, knew it well, and had nurtured a heartfelt scorn toward its wayward democracy. His writings affected a knowing tone of familiarity, but also a certain condescending air of compassion for the errant ways of England’s Anglo-American kindred. It was his professed desire to see Americans become “kinsman whom we can respect” that compelled him to write a scathing treatise on their failures.30

Spence would become active in numerous pro-South organizations and fund-raising activities, but he made his biggest mark with his pen. The American Union first appeared in early November 1861 and quickly went through four editions by March 1862. It was telling of the Confederate diplomatic corps that William Yancey and his fellow Confederate commissioners seemed not to take any notice of Spence’s success. Nor is there any evidence that the State Department in Richmond knew anything about Spence and his book. It was only after James Mason, newly appointed Confederate commissioner to London, arrived that anyone thought to send a copy to Richmond. Even then, Mason admitted that he had “not yet had time to look into it,” but “it is said on all hands to be the ablest vindication of the Southern cause.”31

Much of Spence’s book rehearsed the familiar arguments for the right of secession under the peculiar terms of the US Constitution. Predictably, he explained the growing conflict between the sections as those that naturally arise between agrarian and industrial societies. What made Spence’s American Union so appealing to conservative European audiences, however, was its relentless critique of the evils of “unqualified suffrage” that had overwhelmed the American republic in a “deluge of democracy.” Spence pandered to Britain’s abiding hatred of the French by blaming America’s travails on the early “infection” of French revolutionary ideas in the young republic, spread by Thomas Jefferson and his ilk. The insidious influence of continental radicalism had further perverted the Republic, due to the influx of immigrant rabble polluting Northern cities. Not only did they give the North political majorities over the South in the federal Congress, but the “overgrown foreign element” had also exercised an “injurious influence” on the entire nation. Spence portrayed the South, in contrast, as the valiant defender of the Anglo-Saxon race in America, taking its stand against the foreign hordes that had overrun the North.32

Spence addressed the slavery question with a boldness few Confederate envoys would have dared. In the South, he insisted, slaves received benign treatment, their “animal comforts” comparing favorably to the “suffering and hardship” of “many classes of European labour.” “In Europe a man must work, or starve; there is the compulsion of necessity.” Spence waded without hesitation into current anthropological theory on the inequalities among human races and argued his case for the “radical inferiority” of Negro “mental power.” Armed with Arthur Gobineau’s scientific racial theory, Spence ridiculed the whole notion of equality among human races as weak-minded nonsense propagated by sentimental philanthropists.33

In early 1862 Henry Hotze, who had been sent to Britain to generate favorable press for the Confederacy, arrived in London and immediately recognized the propaganda value of Spence’s American Union. He was ecstatic. It “compares favorably in acuteness of penetration and closeness of reasoning with De Tocqueville’s ‘Democracy,’” he gushed to the home office in late February 1862. “The good effects of this book are everywhere perceptible,” Hotze thought, and it proved that the soil was fertile for whatever “healthy seed” he might plant on his own. “I send a copy of Mr. Spence’s book to the President,” he wrote Richmond the next month, and “another for yourself . . . to multiply the chances of this valuable book reaching the Confederacy.” “I am,” he added with uncontained joy, “for the first time, almost sanguine in my hopes of speedy recognition.”34

Once Mason got around to reading Spence, he too was powerfully impressed. “It has attracted more attention and been more generally read both here and on the Continent than any production of like character,” he wrote to Richmond in May 1862. “Its general purpose was to enlighten the European mind as to the causes which brought about the dissolution of the Union . . . and to put an end at once to all expectation of reunion or reconstruction in any form.” Mason also rhapsodized about Spence’s many labors on behalf of the South, not least as a “constant contributor to the London Times in articles of great ability, vindicating the South against the calumnies from the Northern Government and press and infusing into all classes in England sympathy with us.”35

Meanwhile, Hotze went to elaborate efforts to have Spence’s book translated into French and German for the benefit of continental audiences. Believing Southerners could also learn from Spence, Hotze arranged for a Confederate edition to be published in Richmond in early 1863.36

Astonishingly, neither Hotze, Mason, nor anyone else in the Confederate government seemed to have taken any notice of the heretical denunciation of slavery in Spence’s book. No matter what could be said to justify slavery, Spence baldly acknowledged, “it remains an evil in an economical sense—a wrong to humanity in a moral one.” Slavery, he went on, is “a gross anachronism, a thing of two thousand years ago—the brute force of dark ages obtruding into the midst of the nineteenth century.”

Spence knew his audience. He was playing to British antislavery sympathies with a clever argument designed to confound abolitionists. It would become the party line among Southern supporters abroad: an independent South that was no longer menaced by incendiary Northern abolitionists would bring slavery to an orderly end far sooner and with more humane effect than the greedy, hypocritical North. Spence wanted to isolate the Southern cause of independence from the defense of slavery, and it was a smart strategy in a country that took such pride in its stance against slavery around the world. But Spence’s heresy on slavery would vex Hotze and the Southern cause in Europe once Lincoln proclaimed emancipation as the Union’s goal in the autumn of 1862.37

FOR BRITISH REFORMERS, THE AMERICAN QUESTION MESHED conveniently with their movements for democratizing suffrage and workers’ rights. The Trent crisis inspired defenders of the Union to summon their countrymen to stand by the American “branch” of English civilization in its hour of peril. At the same time the Radicals, those who advocated universal suffrage, began to lacerate aristocratic politicians and journalists who rejoiced over America’s troubles. The American question thus joined the British question on democratization.

The Union had dozens of vocal advocates across Great Britain and Ireland, but none more powerful than John Bright, the leading proponent in Parliament for suffrage reform. A successful cotton mill owner in Lancashire, Bright had inherited the business from his father and grew up in the comfort of a large country estate. Given his business interests and especially his dependence on cotton imports, Bright might have been expected to put his magnificent oratorical talents to work warning Britain of the coming “cotton famine” and urging recognition of the South. Instead, he became a champion of the Union cause. More than that, Bright told the British that at stake in the American contest was the universal emancipation of labor and the fate of democracy on both sides of the Atlantic.38

The Brights were Quakers, and from an early age John Bright had learned to follow an inner light. Throughout his long career in politics, he stood apart from any party organization and kept an arm’s length from the upper classes. Quakers and other dissenters, in any case, were excluded from Oxford and Cambridge and from aristocratic social circles in general, which only made it easier for Bright to advocate democracy and rail against privilege.

As a young man Bright joined forces with free-trade liberal leader Richard Cobden in organizing the Anti–Corn Law League, a grassroots reform movement to end the protective tariff on wheat and make food more affordable for the British poor. Bright entered Parliament in the 1840s and soon rose as the leading voice for American-style “universal suffrage.” But as a free-trade liberal, Bright despised the protectionist Morrill Tariff that America’s Republican Congress had passed in March 1861. He also found little to inspire him in Lincoln’s inaugural pronouncements guaranteeing slavery in the Southern states. He wondered if it might be better for the North to rid itself of slavery and the South to rid itself of the tariff. In this “American confusion,” as he referred to it, Bright saw nothing but trouble for Britain.39

Bright came out for the Union in a speech on August 1, 1861, just before news of the Battle of Bull Run arrived in England. But he made the case for British support of the Union primarily on the conservative argument that any nation had the right to suppress rebellion. “Do you suppose,” he mischievously asked, “that, if Lancashire and Yorkshire thought that they would break off from the United Kingdom,” the British press “would advise the government in London to allow these two counties to set up a special government for themselves?” And what would they say to Irish secession? He closed with a swipe at “those who wish to build up a great empire on the perpetual bondage of millions of their fellow-men.”40

Bright was not certain that the United States would survive after the embarrassing defeat at Bull Run. Conservative adversaries were cheering for what they regarded as the “gallant little South,” and Bright despaired to his friend Cobden that the North would have to recognize the South’s independence. The Union seemed a lost cause.41

But in December 1861 with the Trent crisis looming over Britain, Bright’s public stance on the American question changed radically. Bright’s Quaker pacifism joined his democratic ideological convictions to produce a bold new construction of the American question. With the drumbeats for war sounding ever more loudly, Bright scheduled a public speech for December 4 in his hometown, Rochdale, in the heart of the Lancashire cotton mill district. It was the speech of his lifetime. The public hall was packed with 250 men who had gathered for a banquet; the galleries were filled mostly with women.42

Bright was extraordinary as an orator. A man of fifty, his round, cherubic face was framed by a high forehead, wavy graying hair, and bushy muttonchop sideburns. His voice had a “bell-like clearness,” his biographer George Macaulay Trevelyan recalled. Even in the largest hall, “he never strained, and scarcely seemed to raise it.” Bright spoke with zeal but always with a notable “absence of gesture.” “There he stood foursquare and sometimes half raised his arm,” Trevelyan described it, yet “he awed his listeners by the calm of his passion.” Bright always struck a democratic chord, identifying with the people in opposition to the privileged classes who governed them, but he never stooped to demagoguery or personal vilification of the privileged. His appeal was to his fellow citizens, urging them to maintain the path of peace and freedom when political leaders seemed intent on leading them astray.43

At Rochdale that December, as war fever reached its peak in Britain, Bright gave a full-throated defense of the Union as the American branch of what he declared to be a “transatlantic English nation.” This was not just America’s civil war, he told the crowd; this was a conflict of global significance. Furthermore, Britain had played an ancient and shameful role in creating the conflagration by its role in introducing slavery into the American colonies. Within America’s Christian democracy what began as a comparatively small evil had fomented an “irrepressible conflict.” The “crisis to which we have arrived,—I say ‘we,’ for after all, we are nearly as much interested as if I was making this speech in the city of Boston or the city of New York,—the crisis, I say, which has now arrived, was inevitable.”44

Bright closed with an impassioned call for solidarity with England’s “brethren beyond the Atlantic.” He was trying to defuse the Trent crisis, but in doing so he made ominous allusions to future conflicts with America. Whether the South won or not, the United States would again rival Britain. “When that time comes,” he told the citizens of Rochdale, “I pray that it may not be said amongst them, that, in the darkest hour of their country’s trials, England, the land of their fathers, looked on with icy coldness and saw unmoved the perils and calamities of their children.”45

The Rochdale speech was the first and clearest bugle call that any prominent British political leader had sounded for the Union. It lasted a full hour and forty minutes, and if the reports of the cheers and applause are any indication, it left the crowd in a frenzy of enthusiasm for Anglo-American solidarity. The impact of the Rochdale speech rippled through Britain and across the Atlantic. New York publisher G. P. Putnam, always ready to give voice to European supporters of the Union, issued the full text as A Liberal Voice from England.46

John Lothrop Motley, the US minister in Vienna, wrote to Bright, praising “the breadth and accuracy of view, the thorough grasp of the subject and the lucid flow of argument by which your speech was characterized.” That it was delivered during the bellicose madness of the Trent crisis, Motley added, made “it impossible for me to express my emotions in any other way than in one honest burst of gratitude to the speaker—Thank God!” Motley agreed heartily that British conservatives favored the South as a rebuke to democracy. “The real secret of the exultation which manifests itself in the Times and other organs over our troubles and disasters,” he told Bright, “is their hatred not to America so much as to democracy in England.”47

The day after his speech in Rochdale, Bright sat down to fuel the cause of transatlantic peace by writing his old friend Charles Sumner, who had spent considerable time in Britain before the war. Though the British decry the violence of the democratic mob in America, Bright mused, “our Government is often driven along by the force of the genteel and aristocratic mob.” England is “arrogant and seeking a quarrel,” he told Sumner bluntly, but your “great country” represents “the hope of freedom and humanity.”48

Bright’s letter made its mark. Lincoln invited Sumner to the cabinet meeting held on Christmas Day 1861 that would decide the fate of war between the United States and Britain. There Sumner read the letter from Bright and another from Cobden, both pleading for a peaceful solution. Bright opened up a path of direct communication with the president as well. Lincoln, for his part, so admired Bright that he had a large photograph of him in his office, a reminder that friends across the Atlantic stood by America.49

Bright continued to castigate the privileged governing classes for their hostility toward America and for their sympathy with the slaveholders of the South. But he also reached out to the working classes of England to enlist their support in what he viewed as an international struggle for democracy and emancipation of labor.

The war brought great hardship to mill workers, and as the Union blockade tightened its hold on the South, the prospect of a “cotton famine” became real. It is no wonder that cotton mill workers joined in voicing concern over the war or that some supported the South’s bid for independence, just as Cobden and other free-trade liberals thought first of aligning with the South. The ultimate impact of the American crisis, however, was to unify workers across ideological and generational divides and form bridges between labor and middle-class reformers in opposition to slavery and in support of the Union. W. E. Adams, a veteran of the Chartist movement that advocated democratic reform during the 1830s, saw in the American war “the greatest question of the centuries. It was greater than the Great Rebellion, greater than the French Revolution, greater than the war of Independence . . . as great as any that has been fought out since history began.” Support for the Union came to be regarded as a test of commitment among Radicals, who denounced opponents as Southern sympathizers. They even stormed some “Southerner” meetings and transformed them into spontaneous demonstrations for the Union.50

British popular support for the Union would eventually be galvanized by Lincoln’s emancipation policy, once it was enacted in January 1863. By that time Bright and Radical labor leaders had already nurtured the idea of a shared interest in Union victory. Had Britain, instead, helped sustain a nation dedicated to slavery, one historian later speculated, “the example would have spread like the plague in a world ever susceptible to such infection.” “John Bright saw it then, when the wise were blind; and he made half of England see.”51

ANOTHER, AND FAR MORE UNEXPECTED, VOICE FOR THE UNION CAME from Karl Marx, an advocate of capitalism’s demise. Living in exile in London, Marx spent most of his days at the British Library, researching his magnum opus, Das Kapital (1867). Marx shared little of Bright’s concern for the salvation of bourgeois democracy or national unity. For him, the American war was the vanguard of the class struggle.

During the first volatile year of war and diplomacy, a large segment of the reading public in America and Europe learned about the war through this German-born communist revolutionary. Marx had been hired ten years earlier as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune, the largest newspaper in the United States and perhaps the world, with an estimated readership exceeding 1 million. Horace Greeley, the publisher, introduced his new European correspondent by saying Marx had “very decided opinions of his own,” but he was “one of the most instructive sources of information on the great questions of current European politics.” Greeley was a liberal reformer, an advocate of antislavery and the rights of workers and women. He and his managing editor, Charles Dana, were also deeply interested in the radical political movements that had stirred Europe during the Revolution of 1848. Dana had met Marx during the revolution, when he hired him to write for the Tribune.52

Accustomed to airing his views among small cliques of fellow revolutionary exiles over warm beer in a London pub, Marx welcomed the opportunity to reach such a vast American audience. He privately loathed Greeley as a bourgeois protectionist and white-haired armchair philosopher, but Marx was desperate for money, even five dollars per article, which was about his only income while he struggled to keep his family housed and fed.53

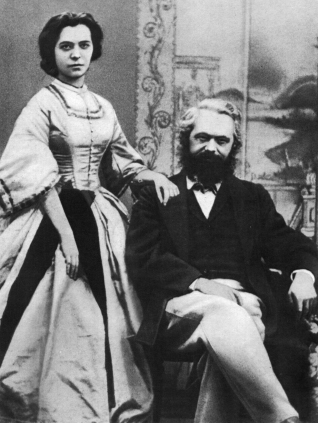

Marx had grown up in a prosperous middle-class Jewish family in Prussia. As a young law student in Bonn, he appeared to be more fond of beer than scholarship. His father made him transfer to the University of Berlin, where he met and eventually married a wealthy Gentile baroness, Jenny von Westphalen. It was also in Berlin that he got caught up with a political group known as the Young Hegelians and became thoroughly immersed in the world of radical political ideology. He lived by turns in Paris, Brussels, and Cologne.54

After the Revolution of 1848 failed, Marx and his wife fled to London and began a life of desperate poverty in the slums of Soho. Three of their six offspring died in childhood. With their surviving children, they moved from their squalid Soho hovel to a more spacious apartment in suburban Kentish Town. The rent absorbed most of his meager income from freelance writing, which left Marx begging money from friends, usually Frederick Engels, a fellow revolutionary, whose family owned a factory in the north of England. His letters to Engels were filled with financial and health woes. “A ghastly carbuncle has broken out again on my left hip, near the inexpressible part of the body,” Marx shared with Engels in one such letter. Marx also successfully badgered Dana to raise his pay from five to ten dollars per article. But when the Civil War came, the Tribune decided to cut back on its coverage of overseas correspondents in order to focus more attention on the conflict at home. Dana directed Marx to write on European, particularly British, opinion regarding the American crisis.55

Frederick Engels was the coauthor, editor, and unpaid ghost writer of some of the weekly essays Marx published on the American Civil War with the Tribune. Marx was brilliant and well read, but his English was dreadful and his handwriting illegible. He depended on Engels to make sense of what he was trying to say and on Jenny to put it in legible form before sending the copy to New York.56

The Tribune articles, however, were only a fraction of what the two men wrote about the American war during the next four years. They became increasingly obsessed with the American war and constantly wrote letters to one another, sharing news from America. Maps of the United States covered the Marx family’s dining room table, and newspapers were stacked high in every corner. Joseph Weydemeyer, a German immigrant who ran a journal in New York, sent Marx and Engels newspapers and kept them abreast of American affairs in lengthy letters. Engels considered himself to be an expert on military matters, while Marx took special interest in the economic factors underlying war and diplomacy. In addition to the Tribune articles, they coauthored a series of thirty-five essays published by Die Presse, an important German-language newspaper in Vienna. Together they worked out an unusually penetrating analysis of the American war and its meaning for the world.57

21. Karl Marx with his wife, Jenny. (COURTESY MARXIST INTERNET ARCHIVES)

Their fascination with the war had much to do with the surprising contradictions it presented to their theories of class conflict and historical change. In their famous Communist Manifesto, published in 1848, Marx and Engels had asserted that the real conflict of the age was not between republicanism and aristocracy. Forms of government were but political superstructures underneath which were deeper structures configured according to the means of economic production. All of human history was the history of class struggles, which in turn were determined by the changing means of production, the Manifesto explained. Just as the capitalist class, arising out of modern forms of international commerce and industrialization, had supplanted the old landed aristocracy of feudalism, the next and final stage of history, they prophesied, would witness the triumph of the industrial working class. Marx and Engels had little sympathy for sentimental patriotism and nationalist allegiances, which they saw as manipulative devices employed by the ruling classes to distract workers from the class struggle.

What they saw in America, thought to be a land born free of Old World feudalism, was the last vestige of a feudal, landed, slaveholding class staging a counterrevolution against the industrial and mercantile bourgeoisie who championed free labor capitalism. “The present struggle between the South and North is . . . a struggle between two social systems, the system of slavery and the system of free labour,” Marx wrote in October 1861. “It can only be ended by the victory of one system or the other.” At stake was not only the death of slavery in America, but also the emancipation of labor everywhere.

Marx realized that slavery lay at the heart of the matter, regardless of what Lincoln declared to be the Union’s policy on emancipation. The question was not “whether the slaves within the existing slave states should be emancipated outright or not, but whether the twenty million free men of the North should submit any longer to an oligarchy of three hundred thousand slaveholders.” Nor was the question limited to the fate of the United States, for the slave oligarchy sought the “armed spreading of slavery in Mexico, Central and South America.” In the American war Marx and Engels sided with the bourgeois North. They called for a revolutionary war against the South that would herald the general emancipation of labor and prepare the way for America to serve as the vanguard for the next stage of history.58

“The first grand war of contemporaneous history is the American war,” Marx announced to Tribune readers in September 1861. The “highest form of popular self-government till now realized is giving battle to the meanest and most shameless form of man’s enslaving recorded in the annals of history.”59

Marx was determined to educate readers on the fundamental harmony of interests and values between the South and counterrevolutionary forces in Europe. He drew special attention to the intrigues of the British, Spanish, and French governments against the Juárez regime in the Republic of Mexico. The Tripartite Alliance’s invasion of Mexico he judged to be “one of the most monstrous enterprises ever chronicled in the annals of international history,” marked by “an insanity of purpose and imbecility of the means employed.” He blamed the Mexican venture largely on Spain, whose “never over-strong head” had been turned by “cheap successes in Morocco and St. Domingo.”60

During the stormy Trent crisis, Marx took special pleasure in exposing the venal hypocrisy of the British government and press. You may be sure, he warned Tribune readers, that Palmerston wanted “a legal pretext for a war with the United States.” He excoriated the “yellow plushes” of the British press for their hysterical warmongering and posturing in defense of British honor. The whole affair, Marx insinuated, was stirred up by speculators who wanted to fleece unsuspecting investors in the stock exchange.61

Marx was especially scornful of France, “bankrupt, paralyzed at home, beset with difficulty abroad,” and now pouncing upon the prospect of Anglo-American war as a “real godsend.” France’s “tender care for the ‘honor of England,’” its fierce diatribes urging England to “revenge the outrage on the Union Jack,” and its “vile denunciations of everything American” were as ridiculous as they were appalling.62

His very cynicism about the designs of British and French rulers during the Trent crisis led Marx to counsel peace to Americans, lest they “do the work of the secessionists in embroiling the United States in a war with England.” Such a war, he cautioned, would be a “godsend” to Napoleon III, given “his present difficulties,” and it would ignite popular support for him in France. Marx also took delight in lampooning William Yancey and the Confederate commission, which “exhausts its horse-powers of foul language in appeals to the working classes” to support a war with America.63

Marx praised the British working classes for their “sound attitude,” all the more so for the striking contrast between them and the “hypocritical bullying, cowardly, and stupid conduct of the official and well-to-do John Bull.” America must never forget, he insisted, that “at least the working classes of England” had “never forsaken them.” They never held a public war meeting, even when “peace trembled in the balance” during the Trent crisis. This was due, he felt certain, to the “natural sympathy the popular classes all over the world ought to feel for the only popular government in the world.”64

These tributes to transatlantic solidarity came from the last of Marx’s articles published by the New York Daily Tribune in January 1862. Greeley wanted to give more space to military matters at home, and he was no doubt distressed by Marx’s caustic tone and radical ideology. Though his direct conduit to American readers ended, Marx continued to interpret the American war for Die Presse throughout 1862.65

Later, in 1864, on behalf of the International Workingmen’s Association, Marx hailed Lincoln’s reelection victory at the polls. Slavery, a major obstacle to the emancipation of all labor, “has been swept off by the red sea of civil war.” For this, he thanked Lincoln, “the single-minded son of the working class,” who led “his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world.”66

OTTILIE ASSING (PRONOUNCED “AH-SING“) TRANSLATED THE AMERICAN Civil War for European audiences at the side of one of the most important African American voices of the time. She grew up in Hamburg, where her Jewish father and Christian mother had defied convention by marrying. Her father converted to Christianity, changed his name, and had young Ottilie baptized after her birth in 1819. The family was nonetheless exposed to cruel anti-Semitism and scorned as Halbjüdinnen (half-Jews). Her German childhood imprinted in young Ottilie a defiant scorn toward prejudice of all kinds. After the untimely death of their parents, Ottilie and her sister moved in with relatives and later had a bitter falling-out with one another.

It was as much to escape family problems as political oppression in Germany after the failed Revolution of 1848 that in 1852 Ottilie, at thirty-three, single, skilled in several languages, and determined to make her way in the world, sailed alone to make a new life in New York. She was a passionate feminist and freethinking radical reformer who learned to live by her pen. She began writing about American culture and society for Berlin journals and then turned to the subject that consumed much of her life, the problem of race and prejudice.67

Assing became determined to translate for Europeans the authentic voice of the African American experience. After a false start with several essays on a black religious leader, she decided in the summer of 1856 to travel to Rochester, New York, to meet Frederick Douglass. What began with her translating his autobiography into German soon evolved into an intense intellectual and apparently romantic liaison between the married black abolitionist and the passionate German émigré intellectual that endured nearly three decades.

During the 1840s Douglass’s autobiography and impressive oratorical skills had made him the leading African American voice of antislavery. Fearing that his fame might tempt his former master to try to abduct him, during the 1840s Douglass spent two years abroad in Ireland and Britain. He witnessed the suffering of the Irish during the potato famine and returned home with a more cosmopolitan view of social problems and with a broadened conception of emancipation as something that must be extended to all human beings, including women. He became involved in the woman’s rights movement and spoke eloquently for woman suffrage at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. In Ottilie Assing, a half-Jewish, German radical feminist, Douglass discovered an extraordinary partner. They attended meetings and traveled together, read one another’s work, and thought and wrote in tandem.68

In April 1861 Douglass and Assing were planning to move to Haiti to pursue what Douglass described vaguely as “a purpose, long meditated.” He held little hope for the newly elected president, whom he believed was already bending his knees to slavery. American blacks might have to consider another means of exodus from slavery, and Haiti might be their New Canaan. For Ottilie Assing, the cosmopolitan milieu of Haiti offered a place where she and Douglass could live openly together.69

News of the attack on Fort Sumter came on the eve of their departure, and they immediately postponed their travel plans. Both of them threw their full energies into channeling the conflict over secession into a revolutionary war on slavery and a war fought by black men for their own emancipation. Assing wrote for European audiences, primarily through Morgenblatt für gebildete Leser (Morning journal for educated readers), a prestigious Berlin journal, while Douglass issued commentary through his own antislavery journal, Douglass’ Monthly. They addressed parallel topics and issued similar arguments, at times borrowing heavily from one another’s writings.70

Assing immediately interpreted the war as something much greater than a local conflict over secession or even the future of slavery in America. She told her German readers it was nothing less than the fulfillment of “the great revolution” that had failed in 1848 and was now about to sweep before it all forms of human inequality, oppression, and prejudice. “We have been at war for several months, but the great mass of the people have not yet understood that we are not fighting against a so-called rebellion.” The war was “a revolution whose seeds were present at the founding of the republic and whose eventual outcome will determine the fate of the country and the nation.” It is “quite simply and irreducibly the eternal war between slavery and freedom that has been repressed and postponed by halfway measures and compromises for more than seventy years and has now erupted with all the more force.” Like Douglass, throughout the war Assing despaired at the efforts of Lincoln administration officials to “mislead themselves and the rest of the world” from what everyone understood to be the heart of the conflict.71

Ottilie Assing translated the meaning of Frederick Douglass and the American Civil War for German-speaking audiences, and at the same time helped interpret for Douglass the cosmopolitan context of the struggle that engulfed them. Meanwhile, against all odds, she sought to live out her ideal of love across the color line, which she viewed as the ultimate rebuke to the racial prejudice that lay at the heart of slavery. Emancipation, Assing hoped, might permit her to realize her desire to live as Douglass’s “natural” wife. Douglass, however, remained bound to his actual wife until her death in 1882. He and Assing had parted ways in the meanwhile. Ottilie Assing was traveling in Europe and facing terminal breast cancer when she learned, sometime in early 1884, that Frederick Douglass had remarried. One morning in Paris, dressed elegantly as always, she walked to the Bois de Boulogne, sat on a bench, and swallowed a vial of potassium cyanide.72

EACH OF THESE EUROPEAN TRANSLATORS OF THE AMERICAN QUESTION came from different ideological positions: Gasparin was a constitutional monarchist, Laboulaye a French republican, Spence a conservative critic of democracy, Bright a Quaker reformer, Marx a revolutionary socialist, and Assing a radical freethinker. Each coupled the American crisis to current political debates within their own milieu. That none (save Spence and Assing) had ever visited America hardly mattered. For them, America was something more than a particular nation or people, and the Civil War was something more than a struggle over territory and sovereignty. They and many other foreign observers were translating the meaning of the war for the world at large—and for Americans.