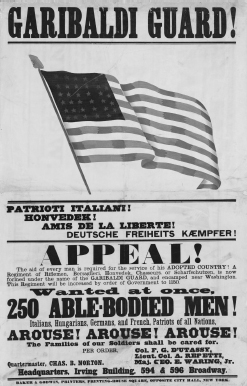

Patrioti Italiani! Honvedek! Amis de la liberté! Deutsche Freiheits Kaempfer! The aid of every man is required for the service of his adopted country! Italians, Hungarians, Germans, and French, Patriots of all Nations. Arouse! Arouse! Arouse!

—GARIBALDI GUARD, NEW YORK 39TH INFANTRY, RECRUITMENT POSTER, APRIL 1861

WHILE FOREIGN POLITICIANS, JOURNALISTS, AND INTELLECTUALS took up their pens and raised their voices to translate the American question for foreign audiences, hundreds of thousands of immigrants and the sons of immigrants took up arms and risked—and often gave—their lives as Union soldiers.

US legations abroad were inundated with volunteers, many of them professional soldiers asking for commissions, others expecting enlistment bounties and free passage to America. During the first summer of war, Romaine Dillon looked out of his office window in the US legation in Turin, Italy, to see a long line of men, many wearing the red shirt emblematic of the Garibaldini. They had come to enlist in America’s Risorgimento.

From Brussels Henry Sanford related the amazing story of George Nanglo. Born in New York and educated in France, he had served as a major in the Crimean War, fought with Garibaldi’s Thousand in Sicily, and then wound up in the Turkish army. Now he was eager to return to his “native land” and raise his sword for the Union, and he needed Sanford’s help to get back home.1

James Quiggle, the Antwerp consul, had sought to flatter Garibaldi by promising that thousands would rush to join him if he came to America. Whatever else Quiggle got wrong that summer, he anticipated one of the most remarkable features of the war. With or without Garibaldi, immigrant soldiers from all parts of Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere would volunteer for the American war. Several thousand fought for the Confederacy, but the lion’s share of immigrant recruits formed the Union’s foreign legions, and without them the Union might never have won.

Those who were recruited abroad during the war joined a much larger number of immigrants who had arrived since the late 1840s, refugees from the famines, repression, and failed revolutions that beset nineteenth-century Europe. By 1860 the United States had more than 4 million foreign-born inhabitants constituting about 13 percent of the population. They concentrated in the free states of the North, drawn by jobs in the urban economy, and they generally avoided the South, some out of moral antipathy toward slavery, others out of a practical preference not to compete with slave labor. In 1860 less than 6 percent (233,000) of the nation’s foreign born lived in states that would join the Confederacy. Significantly, they were concentrated in cities such as New Orleans, Nashville, and Memphis, which fell under Union control before the South could draw on this foreign-born manpower.2

Immigrants and the sons of immigrants constituted well over 40 percent of the Union’s armed forces. Germans and Irish made up nearly two-thirds of the Union’s foreign-born soldiers, followed (in order) by those from Great Britain, Canada, France, Sweden, Norway, Hungary, Poland, Italy, Latin America, and elsewhere. Among the Union dead at Gettysburg was John Tommy, a Chinese immigrant who had been a favorite among his American comrades in arms.3

One night early in the war, General George McClellan was returning to camp when Union pickets challenged him. He could not make himself understood. “I tried English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Indian, a little Russian and Turkish,” all without success. McClellan most likely inflated the communication problem (and his language skills), but the polyglot nature of the army he led was no exaggeration. McClellan had toured Europe during the Crimean War and was quite familiar with the concept of foreign legions serving within national armies. But something new was taking place in the American war.4

The exact numbers and national origins of the foreigners who fought remain uncertain, but this much is clear: they were vital to Union perseverance and their participation underscored the perception of the war as an international struggle. Yet, despite their importance to the war’s outcome, a legacy of bias and language barriers has conspired to leave immigrant soldiers in the shadows of America’s Civil War narrative. During the war they were disparaged by fellow Unionists as well as by Southern detractors, who called them “mercenaries” and “soldiers of fortune,” implying they had no honorable motive to enlist beyond earning a bounty or indulging a youthful spirit of adventure. Critics suggested that foreign recruits lacked patriotic valor and were unwilling to fight and die for a nation not their own.5

After the war immigrant groups answered rising nativist prejudice with a spate of publications celebrating the proud contributions of immigrant soldiers who fought America’s wars. One of the recurring themes in such works portrays immigrants “becoming American” and earning their citizenship through sacrifice and military service. There was some truth to all this, but it is important to understand that many immigrant soldiers saw themselves fighting a war in America but not just about America.

For them, it was part of an ongoing struggle that they, or their parents, had fought and lost in the Old World. Many saw themselves fighting for broadly understood principles of liberty, equality, or democracy that transcended any particular nation. Benjamin Gould, the first to chronicle the immigrant soldiers’ role in the war, credited the foreign-born enlistee with a “spirit of sympathy with a republic struggling for the maintenance of free institutions.” More than soldiers of fortune, they were also soldiers of conviction who conflated the American war they fought with the international cause they fought for.6

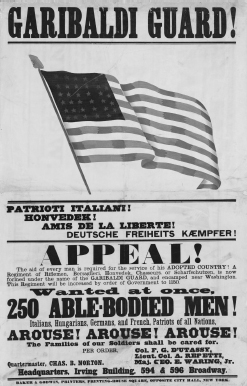

IN THE SUMMER OF 1861, WHEN THE GARIBALDI GUARD, NEW YORK’S 39th Regiment, called for 250 volunteers, it did not matter what language they spoke. Patrioti Italiani! Honvedek! Amis de la liberté! Deutsche Freiheits Kaempfer! (Italian patriots! Hungarians! Friends of liberty! German freedom fighters!), “Arouse! Arouse! Arouse!” Another recruitment broadside called on New York’s German immigrants: Bürger, Euer Land ist in Gefahr! Zu den Waffen! Zu den Waffen! (Citizens, your country is in danger! To arms! To arms!). Patriots of all nations were summoned to arms for “your country.”7

22. Recruitment poster for the Garibaldi Guard. (PERMISSION NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

23. German recruitment poster. (PERMISSION NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

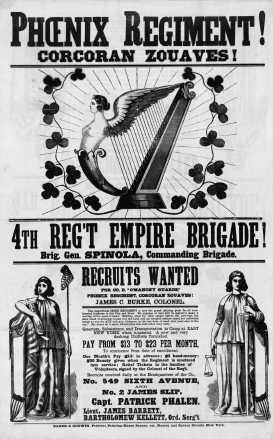

Recruitment posters, broadsides, and speeches at rallies employed an array of languages, often mixing several, and made use of universally recognized iconography to call on immigrant soldiers to fight for their adopted country and for the one they had left behind. In a nation of immigrants, it was understood that patriotism was not always bound to a specific nation-state. It was a transferable sentiment, often a commitment to transcendent, universal principles rather than to one’s place of birth. William Seward answered a controversy over the recruitment of foreign soldiers and officers unable to speak English with a pitch-perfect public declaration welcoming all adopted citizens: “The contest for the Union is regarded, as it ought to be, a battle of the freemen of the world for the institutions of self-government.”8

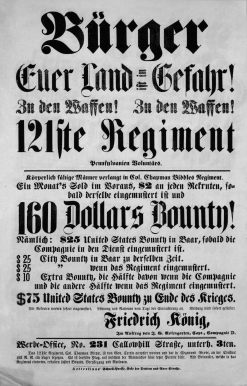

24. Irish recruitment poster. (PERMISSION NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

Vorwärts Marsch!! (Forward march!), one poster for the 1st National Voluntairs of New York commanded its readers. A menacing-looking eagle, which could have as easily signified Germany as America, glared at them, flanked by symbols of commerce and industry. Tretet ein! Lasst euch nicht zwingen! (Come in! Don’t let yourselves be forced!). A poster for Corcoran’s Irish Legion featured a splendid Irish harp and a winged nude female figure, all surrounded by shamrocks and all in brilliant green ink.

Colonel Joseph Smolinski, the son of a celebrated military hero in Poland, invoked his father’s legend to recruit volunteers for the First United States Lancers. The poster featured a cavalier astride a prancing white horse. Sporting long, flowing black hair and a thick mustache, the soldier was flamboyantly fitted out in a fur-trimmed tunic with lacy, puffed sleeves; headgear reminiscent of the Renaissance; buckled shoes; and what appeared to be white tights.

Many recruiting posters portrayed soldiers in dashing military uniforms of vaguely European origin. None were more colorful than the exotic Zouave uniforms, distinguished by their baggy red trousers, bright-colored sash around the waist, short open jacket with embroidered trim, spats or half-gaiters on the lower legs, and a tasseled red fez on top. French forces in northern Africa had borrowed this exotic mode from Berber tribesmen during the invasion of Algeria in the 1830s, and artists depicting French Zouave forces in battle in the Crimea and Italy during the 1850s helped popularize the fashion.

A poster appealing to volunteers for New York’s Empire Zouaves featured a soldier wearing bright-red Zouave trousers and a puffed-sleeve shirt holding an American flag, his sword drawn and his foot on the chest of a fallen foe. In the background on one side were ravaged fields, a village aflame, and distraught women fleeing, while on the other side were a prosperous church, factory, and ships with a Union military unit in formation and a couple embracing beneath the American flag. No one needed to read English, or any other language, to understand what this poster was asking young men to fight for.

Among the international symbols found in the imagery of Civil War propaganda, one of the most ubiquitous was the Phrygian cap, a soft conical, usually red hat that had origins in ancient Rome, where emancipated slaves wore it as a symbol of their liberty. It also had links to the American and French Revolutions, which made the red cap of liberty a modern icon of revolutionary republicanism throughout the Atlantic world.9

The color red—whether in caps, shirts, bandannas, sashes, flags, or banners—became emblematic of the international revolutionary movement. The term red republican grew out of the French Républicain Rouge party that led the Parisian Revolution of 1848, and it was applied disparagingly by conservatives to radical revolutionaries whatever their country. After Napoleon III established his autocratic empire in 1852, he outlawed all displays of the red cap of liberty and even banned the singing of “La Marseillaise,” the anthem of the French Revolution. It should be no surprise that this became a favorite marching song among European volunteers in the American Civil War.

25. Immigrant recruitment poster. (PERMISSION NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

Allons enfants de la Patrie, |

Arise, children of the Fatherland, |

Le jour de gloire est arrivé! |

The day of glory has arrived! |

Contre nous de la tyrannie, |

Against us tyranny’s, |

L’étendard sanglant est levé. |

Bloody banner is raised.10 |

The allegorical figure of Lady Liberty also became commonplace in Civil War recruitment broadsides. With ancient origins as the Roman goddess of liberty, she had become familiar in American iconography as “Columbia,” a feminized symbol of the New World discovered by Christopher Columbus. But in Europe Liberty became recognized as an icon of red republicanism, nowhere more vividly than in artist Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People. Delacroix’s canvas featured a bare-breasted Lady Liberty wearing a red Phrygian cap, the French tricouleur in one hand and a musket in the other, leading armed citizens over the barricades.11

Just before the Civil War, many Americans thought there could be no more fitting symbol of a liberty-loving people than Lady Liberty atop the dome of the new Capitol, still under construction. The secretary of war, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, however, rejected the idea as a rebuke to slavery as well as a foreign symbol of radical revolution. He was right, and it was with exactly these meanings in mind that Union recruitment posters featured Liberty and her red cap.12

PETER WELSH, BORN TO IRISH PARENTS IN CANADA, HAD MOVED WITH his wife to New York City, where he was struggling to make a living as a carpenter in the summer of 1862. While visiting relatives near Boston, he got into a family row and wound up on a long drinking spree that left him bereft of funds. It was to redeem his soiled honor, so he later recounted, that he decided to enlist in the 28th Massachusetts Volunteers.

A year later Private Welsh was writing to his father-in-law back in Ireland, and he had a lot of explaining to do. Written with imperfect grammar and spelling, his letter gave eloquent voice to powerful ideological motivation. It “should seem very very strange that i should volunteerly joine in the bloody strife of the battlefield. . . . Here thousands of the sons and daughters of Irland have come to seek a refuge from tyrany and persecution at home. . . . America is Irlands refuge Irlands last hope. . . . When we are fighting for America we are fighting in the interest of Ireland striking a double blow cutting with a two edged sword.” We do not know how his father-in-law responded, but Welsh reenlisted in January 1864. He died from wounds sustained at Spotsylvania later that year.13

Even a small sample of the letters immigrant soldiers wrote home suggests the war meant more to them than bounties or adventure. August Horstmann was twenty-five and full of patriotic spirit when he wrote to his parents in Germany from the battlefields of Virginia in the first summer of war: “Even if I should die in the fight for freedom and the preservation of the Union of this, my adopted homeland, then you should not be too concerned, for many brave sons of the German fatherland have already died on the field of honor, and more besides me will fall!” “Much the same as it is in Germany, the free and industrious people of the North are fighting against the lazy and haughty Junker spirit of the South. But down with the aristocracy.” Later that year he wrote home again to say, “The freedom of the oppressed and the equality of human rights must first be fought for here!” “To us the war is a war of sacred principles, a war that should deal the fatal blow to slavery and bow down the necks of the southern aristocracy.” His zeal had not dampened by July 1864 when he wrote, “Believe me, this war will be fought to the end, the rebellion will be defeated, slavery abolished, equal rights established in all America, and then finally your Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico owing to Napoleon’s grace, will be sent packing.”14

Magnus Brucker had fled Baden, a small German state, for America after the Revolution of 1848. In September 1864 he wrote to his wife in Indiana from Atlanta to tell her that he did not care if neighbors called him a “Blak Republicaner Abolitionist, Lincolnit or Yankee Vandal.” “I am satisfied with myself and am doing my duty as a citizen of this republic.” He denounced the Copperheads, Confederate sympathizers in the North, as “cowardly traitors.” Were it not for them, “the revolution would have been suppressed a long time ago, and time will tell and history will worship and honor the names of those who bled, fought and died for the Republic.”15

Friedrich Martens “followed the drums when the first call to arms went out through the land” and gave his family back in Germany a cogent summary of why: “I don’t have the space or the time to explain all about the cause, only this much: the states that are rebelling are slave states, and they want slavery to be expanded, but the northern states are against this, and so it is civil war!” Another German recruit gave an equally pithy explanation of the war he was fighting: “It isn’t a war where two powers fight to win a piece of land,” he explained to his family. “Instead it’s about freedom or slavery, and you can well imagine, dear mother, I support the cause of freedom with all my might.”16

One immigrant mother gave poignant testimony to why her seventeen-year-old son was fighting for the Union. “I am from Germany,” Mrs. Chalkstone told the antislavery Women’s Loyal National League convention in New York, “where my brothers all fought against the Government and tried to make us free, but were unsuccessful.” “We foreigners know the preciousness of that great, noble gift a great deal better than you, because you never were in slavery, but we are born in it.”17

THE LEGIONS OF IMMIGRANTS WILLING TO FIGHT AND DIE FOR THE Union were absolutely essential to the final outcome of the war. More would have to be recruited abroad if the Union army was to endure what became a grinding war of attrition—four hard years of massive battles, daily skirmishes, prolonged sieges, and appalling death tolls from combat and disease.

New estimates indicate that at least 750,000 men died on both sides, and another 470,000 were wounded, many of them maimed for life. The equivalent toll in today’s US population would amount to a staggering 7.5 million deaths. Ultimately, victory in the American Civil War depended on which side could outlast the other. Contending sides had to replenish their armies, and it was here that immigrants gave the Union a decisive advantage.18

Lincoln once pondered the “awful arithmetic” that might allow the Union army, because of its overwhelming manpower advantage, to sustain enormous losses in one battle after another yet still win the war by grinding down the smaller Confederate army and exerting pressure on the South’s civilian population. During four years of war, the Union army enlisted about 2.2 million men, versus approximately 850,000 who fought for the Confederate army. The Confederate estimate is less reliable, but it is clear the North enjoyed a manpower advantage in the field that exceeded 2.5 to 1 over four years.19

Both sides soon realized that it would be a protracted war and that they would require more than short-term volunteers. The Confederacy, with its smaller military-age male population, first resorted to a draft in April 1862, shortly after the massive bloodbath at Shiloh. It began by conscripting white men eighteen to thirty-five years of age and eventually expanded the range to include those between seventeen and fifty. Before it was over, the South would be forced to consider arming its slaves.20

The Union introduced a draft one year later, in April 1863. By then an array of bounties and other inducements at the state and local levels also encouraged enlistments. Another vital source of Union recruits resulted from the North’s invasion of the South, which vastly expanded its pool of fighting men while diminishing that of the enemy. More than 76,000 whites from the Confederate states—mostly from nonslaveholding districts of the upper South, Texas, and captured cities—took up arms for the Union. Many of these were immigrants, especially in the cities that were captured.21

The Union’s manpower advantage was substantial to begin with. The Confederate South had a much smaller population, and one-third of it was enslaved. The “military population” (defined as males eighteen to forty-four years of age) was only 1.06 million among whites in the eleven Confederate states in 1860, as opposed to 4.6 million in the rest of the United States—more than a 4 to 1 advantage. This meant that the South had to enlist virtually all of its eligible white males, while the North called less than half of its military population to arms. The pressure to field armies also exerted dangerous strains on the civilian population, revealed dramatically by the New York City draft riots in July 1863 and by the many desertions from the Confederate army. As the war dragged on, political opposition in the North found expression in the Peace Democrats’ campaign for a return to the Union as it was.22

For the Union, one important means of lessening pressure on the civilian population was the expansion of its military population through the enlistment of 180,000 black men. About half were from the Confederate states, and most were former slaves willing to fight for the freedom of their people. None paid more dearly than the black soldiers who took up arms in the Union army, and a good number of their casualties would be attributed to the merciless slaughter of prisoners by Confederate soldiers who refused to give them quarter.

The ability of the North to attract enlistees from abroad during the war meant that, in striking contrast to the South, the potential expansion of its military population was almost limitless.23 Even basic figures on how many immigrants fought in the Civil War and where they came from remain amazingly murky. Record keeping was not systematized across states and localities. At the outset no one thought it important to know where volunteers came from. It was not until quotas, bounties, and conscription came along that information on birthplace and citizenship became noteworthy.

Most of what is known about the ethnic origin and parentage of Union soldiers can be traced back to a massive tome of data compiled by Benjamin Apthorp Gould with the austere title Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldiers. Gould came from an eminent Boston Brahmin family, had been trained in Europe as an astronomer, and during the war served as the chief statistician for the United States Sanitary Commission, a nongovernmental organization that assumed a major role in tending to wounded Union soldiers. Toward the end of the war, he was charged with the task of compiling “anthropological statistics” on the age, height, weight, and other rather intimate physical measurements, along with information on national origin.24

Gould’s task was complicated by the reluctance of Union officers to acknowledge how heavily they relied on foreign-born recruits. Union officials were embarrassed by repeated charges that their army was filled with foreign mercenaries and hirelings—the “dregs” of Europe, as critics described them. They were fighting a war that Yankee natives would not fight for themselves, so Southern partisans charged. Their embarrassment led to a good number of rationalizations and undoubtedly to underestimates of the immigrant contribution.

Conversely, Southern sympathizers did all they could to exaggerate the role of “foreign mercenaries” in the Union’s army. The London Times correspondent reported in June 1862 that the Yankees “contributed several able generals and other officers to the war,” but the rank and file were largely “Irish and the Germans who form at least two-fifths of the whole number of fighting men” and without whom the war could never be carried on.25

John Slidell, the Confederate envoy in Paris, told Napoleon III that “probably one-half of the [Union] privates were foreigners, principally Germans and Irish.” Ignoring France’s own reliance on its famous foreign legions, Slidell spoke of this as a point of shame. The South’s troops, he told the emperor, “were almost exclusively born on our soil,” which meant that Confederate losses on the battlefield carried “mourning into every Southern family.” In the North, by contrast, “no interest was felt” for the “mercenaries who were fighting their battles,” so long as they could get more of them.26

These distortions by Southern sympathizers complicated Gould’s task. He was aware that old-stock, native-born Yankees tended to discount the contribution of foreigners, yet he also seemed captive to their bias. He included in his report dubious claims by Union army officials that foreign enlistees were slow to volunteer and came forth only when bounties were offered. Gould also lent credence to unproven charges that immigrants were notorious “bounty jumpers”—those who enlisted and collected a bounty, then failed to report for duty or deserted and signed up for another bounty in the next town or state. Such assumptions about bounty jumping played to stubborn suspicions about the patriotism of immigrants, and it led to groundless charges that the actual number of immigrant enlistees was inflated by three or four times.27

Long after the war, historians echoed these prejudices and discounted the contribution of immigrant soldiers to the Union victory. Nativist prejudice intensified in the late nineteenth century, while, at the same time, the North and the South sought to submerge their differences in a spirit of reconciliation. The prevailing historical narrative in postwar America came to emphasize a “brother’s war” fought by Americans over uniquely American issues that were of consequence only to Americans. The immigrant soldier had no place in this epic American story about “our Civil War.”28

The estimates of foreign involvement in the Union army and navy tell a different story. About 1 in 4 of the roughly 2.2 million men who served in the Union army were born outside the United States. Even Gould’s conservative estimate put the number at 495,000; recent estimates raise the number to more than 543,000. The Union navy was even more cosmopolitan; 43 percent of its 84,000 members were born outside the United States. In addition, based on Gould’s sample of Union soldiers and sailors, another 18 percent were American born but with at least one foreign-born parent. Taken together, immigrants and the sons of immigrants made up about 43 percent of all Union armed forces.29

Today the notion that so many foreign soldiers fought for the Union may strike some as simply another curiosity of the Civil War. But to understand who these immigrant soldiers were and why they fought—and in such numbers—is to understand why, for much of the world, this was so much more than an American civil war.

FAR FROM SHRINKING “FROM THE FIRST TOUCH OF LIBERTY’S WAR,” as one poet wrote of an earlier conflict, American immigrants responded to the call to arms with extraordinary enthusiasm. Even before the rumors that Giuseppe Garibaldi was coming to America, the New York 39th Regiment adopted his name as a surefire way to draw volunteers. Hundreds of fighting men and dozens of wealthy New York sponsors were thrilled to send forth a regiment in the name of the Hero of Two Worlds. More than any unit, the Garibaldi Guard symbolized the cosmopolitanism of the Union’s foreign legions. The regiment’s marching song, modeled after one sung by troops of Napoleon I, captured the international esprit de corps:

Ye come from many a far off clime

And speak in many a tongue

But Freedom’s song will reach the heart

In whatever language sung.30

The regiment was filled in less than a month with four companies of Germans, two of Hungarians, one of French, one of Spanish, one of Italians, and one of Swiss. Also among the ranks of the American Garibaldini were Latin Americans, including several Cubans, along with volunteers from the Netherlands, Russia, Alsace and Lorraine in France, Greece, Austria, Belgium, Scandinavia, and Slovakia. Rounding out the force was an Armenian, a Gypsy, and a free-black American. The mix of Catholics, Protestants, and Jews gave the regimental chaplain a hard day’s work. Most of the volunteers were dockworkers and seamen, but there were also artisans from every conceivable trade, along with a few lawyers, doctors, and businessmen.

Several women served in the Garibaldi Guard as vivandieres, providing food and drink, and doubling as nurses when the time came. Acting in the European tradition of figlia del reggimento (daughter of the regiment), they dressed in blue frock gowns with gold lace, black-laced gaiters, red jackets, and hats with black and red feathers. Some were wives of men in the ranks, but among them were also young women who had run away from their New Jersey homes to serve with the Garibaldi Guard.

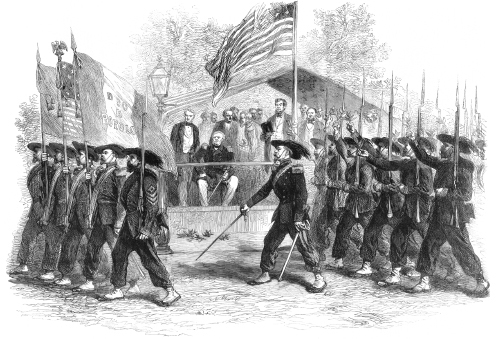

At a flag presentation ceremony held in New York City on May 23, 1861, the regiment pledged allegiance to the Union in no fewer than fourteen languages. Women presented an American flag to the company; then came the flags of Hungary and Italy, the latter emblazoned with Mazzini’s famous slogan, Dio e Popolo (God and People), and said to be the same banner that Garibaldi had fought under during his heroic defense of the Roman Republic in 1849.

26. The Garibaldi Guard Marching in Review, Washington, July 4, 1861. (ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS, AUGUST 3, 1861; AUTHOR’S PRIVATE COLLECTION)

Regimental commander Colonel Frederick George D’Utassy spared none of the money his benefactors donated in fitting out his regiment with the most splendid uniforms the city had ever seen. The rank and file dressed in bright-red flannel shirts, dark-blue jackets and trousers, with republican-red piping. The most dashing feature of the uniform was the round, wide-brim black hat with a cluster of drooping dark-green cock feathers, which were fashioned after the hats of the famed Bersaglieri infantry who had fought gallantly with Garibaldi in Rome.31

The Garibaldi Guard left New York with a spectacular parade down Broadway to the docks. It was “a most moving spectacle,” one witness recorded. “The mass of emotional humanity, waving and cheering and weeping, from housetop and curbstone, formed a great solemn aisle down which the Garibaldi Guard marched (a quick paced trot of the Bersaglieri backed by a fanfare of at least two score trumpets), with floating flags, flowing plumes, glittering gold, and flashing steel, singing La Marseillaise as they went. It was a proud thing to be of the Garibaldi Guard.”32

GERMAN IMMIGRANT SOLDIERS MAY NOT HAVE BEEN AS FLAMBOYANT or cosmopolitan as the New York Garibaldini, but they contributed the largest numbers of any foreign-born ethnic group to the Union army. They answered the call to arms well above their quota of the military population and earned the often grudging respect of military men on both sides. Legend tells of Confederate general Robert E. Lee grumbling that if it were not for the “damned Dutch” (a common term for Germans), he could easily have whipped the Yankees. “The Germans, trained to war by the military system of their own little kingdoms and duchies, seem to sniff the carnage from afar,” Confederate envoy Ambrose Dudley Mann wrote from Brussels. “They come over . . . ready material for the rough work of war, in which they receive more than double the pay of soldiers of Europe.” Together with the Irish, Mann complained, they supply the Union with “at least two-fifths of the whole number of fighting men.” These Germans “hang on the enemy” like bulldogs, one admiring Union officer observed.33

Gould estimated that there were 177,000 German-born soldiers in the Union army, but this is probably a significant undercount. Long after the war, Wilhelm Kaufmann, a German American journalist, mounted an elaborate case to prove that more than 215,000 Germans fought for the Union. The best current estimates are that 190,000 German-born, plus another 53,000 American-born sons of German immigrants, took up arms for the Union.34

Many of the Germans came to America with valuable military training and experience not found among other immigrant groups. Compulsory military service had been introduced in Prussia and other German states during the Napoleonic Wars. Dozens of German soldiers and officers arrived in the United States as seasoned veterans from the Revolution of 1848. Among them were the Salomon brothers of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, who furnished two generals and a private to the Union army, while a fourth brother served as governor of Wisconsin during the Civil War. For the Salomons and many Forty-Eighters, America’s Civil War offered a second chance to fight—and this time to win.35

THE IRISH CLAIMED THE LARGEST SHARE OF FOREIGN IMMIGRANTS IN America, but they fell slightly behind the Germans in the numbers who served in the Union army. Political loyalties conditioned their enlistment to some degree. Mostly loyal Democrats, the Irish were naturally suspicious of a war sponsored by the Republican Party, which many associated with the nativist, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing movement of the 1850s. Republicans, many Irish suspected, wanted them to fight to free blacks who would then compete with them for jobs at the bottom of the American economy.

There was also a historic antipathy between the Catholic Church and republicanism that was rooted in ideological rather than ethnic antagonism. Anti-Catholics viewed the church, and Pope Pius IX in particular, as allies of reactionary monarchism opposed to secular ideals of individual liberty and religious pluralism. The main elements of anti-Catholicism were ingrained in American politics and culture well before the Irish arrived en masse after 1845. Some Protestants interpreted the Irish diaspora to America as part of a sinister Catholic plot to undermine the American republic. Scandalous and often fabricated exposés featuring sexually depraved priests and nuns sequestered behind convent walls inflamed Protestant fears. The “savage Irish” were disparaged for their ignorance, their proclivity for alcohol and violence, and their slavish obedience to the church and the Democratic Party. All but the most strident nativists might be willing to excuse the Irish as “ignorant and unfortunate” victims of their history and religion, but many continued to see the Catholic Church as the enemy of American republicanism.36

The Civil War at once eroded and confirmed ethnic and religious prejudices toward the Irish. Some hailed their willingness to serve the Union and praised their bravery and sacrifice in battle. For their part, many Irish took up the sword in America to prepare for the struggle against the British waiting to be waged back in Ireland. For the Fenian Brotherhood, a group of Irish nationalists formed among Union soldiers, America’s war would be their training tour.37

One of the most prominent Irish nationalists, Thomas Francis Meagher (pronounced “Mahr”) was a man with a sensational background. The attack on Fort Sumter left him “carried away by a torrent” of public opinion. He put aside his Democratic and pro-South sympathies and quickly emerged as a powerful Irish voice for the Union and an energetic recruiter for the famed Irish Brigade of New York. “The Republic, that gave us an asylum and . . . is the mainstay of human freedom the world over,” Meagher told his fellow Irishmen, “is threatened with disruption.” It was now the duty of Irishmen who aspired to freedom “in our native land” to defend it. “It is not only our duty to America but also to Ireland.” Besides, he added, an Irish free republic could never come to be “without the moral and material aid of the liberty loving citizens of these United States.”38

Meagher was born in 1823 to a wealthy and influential Catholic family in Waterford, Ireland. He honed his oratorical gifts at elite schools but held fast to his strong Irish brogue. He came of age enthralled by Daniel O’Connell, leader of a popular movement to liberate Ireland from British rule. Later he became caught up in the Young Ireland movement, one of the revolutionary republican movements inspired by Giuseppe Mazzini, with whom Meagher had become enamored during his travels on the Continent. In 1846 he vaulted to fame after a stunning speech in Dublin in which he renounced O’Connell’s conciliatory policy by refusing to, as he put it, “abhor the sword.”

“Meagher of the Sword,” as he became known, then took a leading role in the Revolution of 1848. He rushed to Paris to witness the successful overthrow of Louis Philippe and returned to Ireland to take part in an unsuccessful uprising there. Meagher and several other republicans were arrested, convicted of sedition, and sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Cautious British officials feared making a martyr of him and chose instead to deport him to the end of the earth, Van Diemen’s Land, a British penal colony south of Australia, now known as Tasmania. Meagher somehow managed to escape the penal colony and by 1852 made his way to New York City, where he launched a prosperous career as a journalist and public speaker on Irish independence. In 1861, still only thirty-eight, he was the leading voice of Irish nationalism in America.39

Their Catholicism, their identity with the Democratic Party, and their instinctive distrust of a Republican abolitionist war all militated against the Irish embracing the Union cause. But there was also a centuries-old tradition of Irish volunteers fighting the wars of other nations. The legendary “Wild Geese” had fled British rule to fight in continental wars, usually for Catholic nations. The slogan emblazoned on the flag of the Union’s Irish Brigade, “Remember Ireland and Fontenoy,” celebrated the famed bayonet charge of the Irish volunteers who saved the day for France against English forces in 1745.40

Whether they fought for Ireland or America, or some transcendent notion of republicanism, before the Civil War was over, more than 144,000 Irish-born soldiers, according to Gould’s conservative count, fought for the Union. Another nearly 90,000 American-born Union soldiers claimed at least one Irish-born parent. The Irish and sons of Irish constituted almost 12 percent of the Union army and by this measure were its most numerous ethnic group.41

THE VITAL STREAM OF IMMIGRATION TO AMERICA SUDDENLY SLOWED to a trickle during the first half of the war. During the 1850s an average of 500,000 immigrants arrived each year in the United States, all but a small fraction settling in the free states of the North. Immigration had slackened by the late 1850s, but when the war came it plummeted to below 92,000 and stayed there for two years. Immigrants had supplied much-needed labor as well as military recruits. They had always been disproportionately young and male; fully one-third of immigrants during the previous decade had been males of military age (compared to one-fifth of the general US population).42

It may have been fear of being dragooned into war or concern that jobs would not be waiting for them that led many Europeans to shun emigration to the United States in 1861 and 1862. But many others wanted to come over because of the war. Volunteers were banging on the doors of the US legation in Berlin. “I am in receipt of hundreds of letters and personal calls seeking positions in the American army, and asking for a means of conveyance to our shores,” one harried diplomat there wrote to Seward. He finally resorted to posting a sign on the legation’s front door: “This is the legation of the United States, and not a recruiting office.” In Paris William Dayton begged for instructions on what to tell all the volunteers asking for a commission and passage. The legation in London had an intermittent stream of volunteers dropping in, among them not a few charlatans asking for commission far beyond their qualifications. From Hamburg the US consul reported daily crowds of men wishing to enlist in the Federal army and suggested paying their passage or deducting the cost from their bounties.43

The Union could not risk appearing to be recruiting a mercenary army to fight a war it had presented to the world as a defense of national integrity. Active recruitment abroad would also violate laws on neutrality and could redound to the benefit of the South. How could the United States protest foreign aid of the Confederacy when it was seeking recruits on foreign shores?44

The laws of neutrality, however, did not preclude normal commercial exchange or international migration. It was through this loophole that Seward and his diplomatic corps launched a remarkable campaign to replenish the Union army and score a clever public diplomacy coup in the bargain. In May 1862 Congress passed the Homestead Act, which promised 160 acres of virtually free western land to any settler willing to build a home and improve the land.45

The Homestead Act had been a campaign promise of Republicans for years, and it played a central role in their vision of a free-soil West for ambitious, poor farmers. But it was Seward’s ingenious idea to transform a domestic policy designed to encourage settlement of the West into a powerful device for recruitment abroad. On August 8, 1862, Seward issued Circular 19 to all diplomatic posts. It instructed agents abroad to make known the generous terms of the Homestead Act and the abundant opportunities for immigrants in America generally. Far from discouraging immigration, Seward wanted it known that the war had created an “enhanced price for labor” due to the absorption of workers in the military. “Nowhere else can the industrious laboring man and artisan expect so liberal a recompense for his services.” Seward authorized his agents abroad “to make these truths known in any quarter and in any way which may lead to the migration of such persons to this country.” He added, with a nod to neutrality laws, that “the government has no legal authority to offer any pecuniary inducements to the advent of industrious foreigners.”46

Seward unabashedly informed his diplomats that this offer of free land “deserves to be regarded as one of the most important steps ever taken by any government toward a practical recognition of the universal brotherhood of nations.” Here was virtually free land being offered to anyone “irrespective of his nationality or his political or religious opinions.”47

In Paris US consul John Bigelow understood immediately the public diplomacy value of Circular 19, and he knew enough not to ask for advance authorization as to how to make use of it. He quickly arranged for Seward’s generous summons to America to be published in all the leading journals on the Continent. The French government at first tried to block Bigelow’s publicity campaign, but it could not find any legal basis for banning a nation from recruiting labor abroad, and it relented. He reported jubilantly to Seward, “Nothing has been published here since the commencement of the war better calculated to reveal to the French people their true interests in our unhappy controversy.” With an almost palpable wink, Bigelow added that there seemed also to be a great demand for information on bounties for enlistments, given the “numerous applications from persons desiring to emigrate and also to take service in the army.”48

The effect of Circular 19 was magical and immediate. Malakoff reported to New York Times readers that “not only do European officers continue to flock to the American Legation in this city to obtain engagements in the army of the United States, but also workmen of the better class, who demand to be enlisted as common soldiers.” He described them coming furtively “in squads” to the legation and sending in “only one of their number as spokesman, while the rest disperse” to avoid police, who were patrolling the street. Dayton confirmed the sudden rush to the legation and suggested to Seward that far more would come if the government could “induce” shipowners to lower passenger fares.49

Bigelow amplified the immigration campaign the next spring with his own publication, Les États-Unis d’Amérique en 1863, a five-hundred-page compendium brimming with statistics and information for prospective immigrants. He distributed it to governments, journals, and leading friends of America across Europe and Britain. By showing what the Union had accomplished, he wrote Seward, we “reveal the loss the world would sustain from Disunion.”50

The stream of immigration across the Atlantic began to swell as the Union’s surreptitious recruitment campaign had its effect. Arrivals in US ports nearly doubled in 1863 to more than 176,000 and continued rising to 248,000 by 1865. Tens of thousands also came across the border from Canada, according to Benjamin Gould, “animated by a kindred interest” in the Union cause.51

CONFEDERATES ANSWERED THE UNION’S OVERSEAS RECRUITMENT campaign by charging that Union agents were luring immigrants with deceptive practices ranging from false promises of civilian jobs to drugging and even kidnapping unsuspecting victims. Bounty brokers in Europe were accused of inducing immigrants to enlist in the army, often under the influence of strong drink at dockside taverns. A notorious crowd of “runners” was alleged to be working on the receiving end in US ports, greeting bewildered newcomers with fast talk and charm, alcohol, even stupefying drugs. There were stories of drunken immigrants being escorted to recruiting stations and waking up the next morning, astonished to find themselves in uniform. Though some of these charges were apocryphal, profiteering from immigrant recruits proved to be a lucrative commerce rife with chicanery all around.52

A government investigation involving a group of immigrants brought to Boston in 1864 provided a revealing glimpse into the operations of this murky commerce. They had been recruited by Julian Allen, described as “a well-known citizen of New York.” Allen was hired by a group of Boston investors, who insisted they were responding patriotically to a call from President Lincoln. In his 1864 annual message to Congress, Lincoln had hailed immigration as “one of the principal replenishing streams which are appointed by Providence to repair the ravages of internal war.” Americans, the president urged, ought to do “all that is necessary to secure the flow of that stream in its present fullness.” These civic-minded Bostonians may also have been facing the draft and seeking cheap substitutes to take their place.53

The investors supplied Allen with funds to pay sixty-four dollars in passage and a bounty of one hundred dollars for each of about two hundred immigrants, the “first experiment” in a program expected to bring about one thousand immigrants to Boston. Among the brokers Allen worked with in Europe was Louis A. Dochez of Brussels, who styled himself “agent for emigration to the United States.” Dochez sent out circulars to the “burgomasters” of Belgium and posted advertisements calling for 800 “able-bodied unmarried men between the ages of twenty-one and forty.” The advertisements made it blatantly clear that they would serve for three years in the US military in exchange for passage, one hundred dollars’ bounty, twelve dollars per month in pay, and food and clothing during their service.

More than 900 men volunteered, and the first boatful with 213 recruits left Hamburg in April 1864. Before leaving each of the men signed, many with an X, a contract that was carefully worded to avoid any charge of illegal enlistment. “We hereby . . . bind ourselves and agree, on our arrival in the United States of America,” the contract read, “to enter into any engagement, for a period not exceeding three years, with Julian Allen.”54

It was after they sailed for America that trouble began. They took a circuitous passage to Hull, then Liverpool, crossing the Atlantic to Portland, Maine, and from there traveled by rail to Boston. Along the way “avaricious influences” in the form of bounty brokers, runners, and even Confederate agents harassed the frightened immigrants, offering inducements to renege on their contracts and enlist for more bounty with another unit or with the Confederacy. By the time they got to Boston, the number had dwindled to 60.

One of the recruits, a well-educated military officer named Jean Barbier Jr. was outraged to learn that he would be treated as an ordinary substitute and be enlisted as a private. Barbier and a few others filed formal complaints, and this forced a full investigation.

Confederate sympathizers in Europe seized upon the story with relish. An article in the Courier des États-Unis compared Dochez’s enticement of unwitting immigrants to a “dealer in human flesh” who led his prey “to the shambles like a herd of slaves.” Dochez answered what he characterized as a “Bonapartist pro-slavery” journal with an exculpatory account testifying that the men were fully aware they were going to America to enlist as soldiers. Union officials in Boston testified that all those who enlisted sang and cheered after taking the oath of allegiance. The only protests came from those who feared they might be rejected, and Barbier’s only complaint was that he was being enlisted as a private and not an officer.

The investigation concluded that there had been no deception or illegal actions, and the sponsors of the Boston immigration program were encouraged to continue. Meanwhile, three more ships brought over more than 900 fresh foreign volunteers before the investigation was even concluded.55

SEWARD COULD HONESTLY STATE THAT THE GOVERNMENT PLAYED NO direct role in enlisting soldiers abroad, but he took pardonable pride in the extraordinary success of Circular 19. Without it, and without the foreign legions that had come before, the Union would have had to rely much more heavily upon its native-born population at grave cost to the political capital of Lincoln and the Republicans. Bigelow also looked back upon the success of Circular 19 with obvious satisfaction: “This circular deserves a place in this record if for no other reason than the light it throws upon the mysterious repletion of our army during the four years of war, while it was notoriously being so fearfully depleted by firearms, disease and desertion.” Apart from its practical benefits in replenishing the army, the Union’s overseas recruitment campaign was a triumph of public diplomacy. Nothing demonstrated quite so clearly the powerful appeal of the Union’s cause than the lines outside US legations abroad and the ships full of immigrants, whether laborers or soldiers, who willingly became part of the “replenishing stream” that sustained Liberty’s war.56