The future destinies of the Latin race in the Old and New World may be wrought up into a magnificent conclusion, and the two master races, the Latin and the Anglo-Norman, typified by Mexico and the Confederate States in the Western Hemisphere, as by France and England in the Eastern, may be represented as clasping hands and marching breast to breast onward in the great career of civilization and true liberty.

—HENRY HOTZE, CONFEDERATE SPECIAL AGENT, AUGUST 23, 1863

AS FOREIGN OBSERVERS TRANSLATED THE AMERICAN QUESTION according to their political agendas, and immigrant soldiers entered the fight with their own ideas of what America’s war was about, both Union and Confederate strategists adjusted to unfolding circumstances, realigning foreign policy and reformulating their appeals to the public mind abroad. In 1862, as it approached the second summer of war, the Union began maneuvering to the left. It embraced the expectation abroad that the Civil War was indeed Liberty’s war, a war to destroy slavery, but also presented it, in Lincoln’s words, as “a people’s contest” in defense of democratic principles. In the face of hostile or at best neutral European governments, the Union was fashioning a soft-power appeal that summoned the public overseas to defend the republican experiment against its aristocratic enemies.

Nothing helped crystallize the ominous narrative of slavery versus freedom, aristocracy versus democracy, so effectively as the Confederacy’s shift to the right. During 1862 the South devised a new strategy to align its bid for independence with Napoleon III’s Grand Design for a Latin Catholic empire in the Americas. This strategic shift involved new initiatives to get the South’s message before the world through an active and well-funded program of public diplomacy.

By the spring of 1862, in the aftermath of the Trent crisis, Confederates were frustrated by Britain’s refusal to recognize their independence, and they began to focus instead on cultivating support in France. Earlier emphasis on the kindred affinities between the English gentry and the South’s landed elite gave way to appeals to the French as their natural ally. Confederate envoy to Paris John Slidell of Louisiana reminded leaders of the French government that the South was inhabited by the descendants of French Huguenots in South Carolina and Creole French in Louisiana. Henry Hotze emphasized that the French language, the Catholic Church, and the Latin temperament were all comfortably embedded in the South’s “Anglo-Norman race.”1

The South now portrayed itself as the main bulwark in the New World against the aggressive Anglo-Saxon “Puritan fanatics” and anti-Catholic Know-Nothings of the North. Confederate agents also made it known that their government repudiated the Monroe Doctrine, smiled upon French ambitions in Mexico, and welcomed a stable monarchy on their southern border. Without admitting that slavery was the main cause of secession, Confederate agents in 1862 also sought to “enlighten” the foreign public on the beneficent nature of Southern slavery, its suitability to the nature of the African race, and the baleful hypocrisy of sentimental Northern abolitionists.

ON FEBRUARY 22, 1862 (GEORGE WASHINGTON’S BIRTHDAY, NOT coincidentally), Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president under the permanent Confederate government in Richmond, standing beneath a monument to the father of the country. This time he had been elected by the people, though few noticed that an election had even taken place. Confederate leaders loathed divisive party politics, and, by design, Davis ran unopposed. There had been, therefore, no noisy conventions, no nomination fights, no campaigns, no rallies or speeches, no groveling for popular support, and there were very few voters as a result. The scant commentary in the Southern press was devoted mainly to excusing the low turnout as due to so many men being off at war, but none saw the meager participation as problematic. In his inaugural address Davis denounced the “tyranny of an unbridled majority” as “the most odious and least responsible form of despotism.”2

Moreover, rather than lament the South’s frustrated appeal for recognition abroad, Davis fairly boasted about its “unaided exertions” to win its own independence. He nonetheless took the occasion of his inauguration to remind the “world at large” that rich stores of “cotton, sugar, rice, tobacco, provisions, timber, and naval stores will furnish attractive exchanges” for those willing to challenge the Union’s blockade.3

William Yancey, returning from his unsuccessful mission in London about the same time, was far more candid. “There was not a country in Europe which sympathized with us,” Yancey told a crowd in New Orleans. “They looked coldly on the South, because of its slavery institutions.” He sounded a note of wounded pride and resentment that soon rang through debates in Richmond. “We cannot look for any sympathy or help from abroad,” Yancey warned the South. “We must rely on ourselves alone.” In Richmond Yancey proposed legislation to recall Confederate envoys from Europe, an idea that continued to smolder in the minds of disgruntled Confederates until the end of the war.4

Whether Yancey or Davis admitted it, however, Confederate hopes for survival depended more than ever on European intervention. After a year of desultory commitment, fluctuating leadership, and inept envoys, in the spring of 1862 Confederate diplomacy was about to change course. Since June 1861 the secretary of state, Robert M. T. Hunter, had been doing little more than warming the seat vacated by Robert Toombs, whose own tenure had been notable only for its lack of energy and success. Neither Hunter nor Toombs found Davis easy to work with, and each became vociferous critics of the president after leaving office. Southern secessionists disdained political parties as one of the diseases of extreme democracy, but in their place came factionalism, petty jealousies, and malicious backbiting among rivals whose political fortunes did not depend on party loyalty.5

In March 1862 Davis appointed his trusted adviser Judah P. Benjamin as the third secretary of state. Far more diligent than either of his predecessors, Benjamin made it his mission to have the Confederacy recognized among the nations of the world at whatever cost necessary. He had already made himself indispensable as a close counselor to Davis, and he had charmed his way into the good graces of Varina Davis, the president’s wife.

Benjamin brought to the task a combination of intellectual agility and a rare cosmopolitan knowledge of the world. Benjamin had been schooled in the importance of impressing those in power. His ancestors were Sephardic Jews who had prospered in Spain as advisers to the Moorish rulers. When the Inquisition came they fled, first to Portugal, later to Amsterdam, and then to London, where his mother and father met. The parents migrated to St. Croix in the British West Indies, where Judah Patrick Benjamin was born in 1811. Later they moved to Wilmington, North Carolina, and eventually settled in Charleston, South Carolina.

Young Judah was a child prodigy. At fourteen, with help from a benefactor in Charleston, he went off to Yale University. Some embarrassing but never explained incident at Yale caused him to return home before graduating. At seventeen he moved to New Orleans and soon launched a lucrative career in law. Marrying into a wealthy Creole family, he acquired a large sugar plantation with 150 slaves. Benjamin also nurtured political ambitions and attached himself to John Slidell’s political machine. In 1852 he was elected as one of Louisiana’s US senators. Benjamin came late to the secession movement, but he rapidly ascended to power in the Confederate government.6

Benjamin became known as the “brains of the Confederacy,” yet Davis was slow to make good use of his gifts. His first cabinet post was attorney general for a nation that had no federal judiciary. Davis then moved him to secretary of war, where he served as nothing more than a front behind which the president himself directed military strategy.7

As secretary of state Benjamin finally found his proper niche. He had command of several languages and was steeped in international law and world history. Far more than Davis, or anyone else in Richmond, Benjamin understood that protracted military struggle would involve politically unsustainable losses and that the quickest path to independence was diplomacy. He also understood that the South could not afford to wait for a cotton famine to bring Europe begging at King Cotton’s throne. Recognition of the Confederacy as a sovereign state would demolish the Union fiction that the war was a mere insurrection. Once the Confederacy was recognized, according to international law, the Union blockade would have to be “effective,” not just an edict on paper banning foreign commerce with the rebels. “Recognition will end the war,” Benjamin wrote to his envoys, “from whatever quarter it may come, and . . . nothing else will.”8

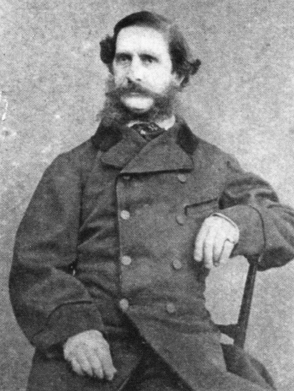

28. Judah P. Benjamin, the third Confederate secretary of state. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

By April 1862, after less than a month on the job, Benjamin had committed more funds, personnel, and imagination to the diplomatic enterprise than any of his predecessors. And he instilled a new sense of urgency in the South’s foreign policy. After a year of inconclusive military struggle, punctuated by recent horrendous losses at Shiloh, the Confederacy had no choice but to introduce a military draft. Concerned that such strain on the civilian population would eventually bring unbearable political pressure on the Confederate leadership, Benjamin realized that the South must win the war abroad or lose it at home.

Though European popular antislavery sentiment frowned upon the Confederate enterprise, the main problem in Benjamin’s view was that the governments of Britain and France had a tacit agreement to act in concert on their American policies. Lord Palmerston and Earl Russell in Britain had good reason to fear that siding with the South would jeopardize Canada and agitate antislavery sentiment at home. Following the Trent affair, during which Britain drew dangerously close to war, Palmerston’s government prudently adopted a wait-and-see posture on the American question, aware that Benjamin Disraeli and his Conservative opposition stood ready to take advantage of the slightest misstep.9

France, it appeared, was the South’s best hope. Napoleon III and his government seemed indifferent to the slavery question and, in any case, less susceptible than the British government to pressure from public opinion on the matter. Furthermore, France’s grand geopolitical strategy in Mexico required Confederate success. Despite the disastrous defeat at Puebla on May 5, 1862, Napoleon had decided to press forward with his Grand Design and conquer Mexico. He committed close to forty thousand troops to the Mexican expedition, including detachments from Belgium and Austria, and made it known he planned to depose Juárez in favor of a Catholic monarchy.10

After Britain withdrew from the tripartite expedition in Mexico, and just before the French disaster at Puebla on May 5, 1862, Benjamin had determined to drive a wedge between France and Britain. His strategy was to offer Napoleon III commercial inducements so lucrative that they could underwrite his venture in Mexico. It could even cover the cost of war against their “common enemy,” the United States, which was likely to ensue should France take sides with the Confederacy.

Benjamin also played an instrumental role in launching a Confederate initiative aimed at “enlightening public opinion” in Europe. The first step came with the enlistment of Henry Hotze, a young Swiss-born journalist from Mobile, Alabama, as head of a new public information campaign in London. Hotze had been sent over by the War Department in the fall of 1861 to expedite arms procurement. Because Benjamin was then serving as secretary of war, Hotze reported to him when he returned in November. Hotze had an exciting new proposal to make. The South, he told Benjamin, must arm itself for a battle of ideas, not just bullets. William Yancey and the Confederate emissaries in London were getting nowhere with Earl Russell, and the South must move around him and get its story before the British people and government.11

Benjamin was impressed with Hotze, his cosmopolitan background, his brilliant mind, and his precocious knowledge of the press and public relations. Hotze persuaded Benjamin that the Union was winning the battle for public sympathy in London and that the Union’s version of things was going unchallenged. What he proposed was a centralized, sustained program of public diplomacy that would use the press to get the South’s version of events before Britain and all of Europe. Benjamin promptly turned the matter over to Robert Hunter, then secretary of state, who found the idea equally persuasive.

By January 1862 Hotze would be on his way back across the Atlantic with a commission as special “commercial agent” to London. “You will be diligent and earnest in your efforts to impress upon the public mind abroad the ability of the Confederate States to maintain their independence,” Hunter’s instructions stated, and “convey a just idea of their ample resources and vast military strength and to raise their character and Government in general estimation.” Hotze had a grander vision of his mission than just rehearsing the case for the South’s material and military strength. He aimed to place the South before the world on a strong moral foundation.12

Hotze’s preternatural brilliance and poise made a strong impression on everyone he met. He was only twenty-seven, short in stature, pale of complexion, with weak, nearsighted eyes that were left strained beyond use at the end of each long day. Born in Zurich, in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, he had been educated in Jesuit schools before coming to the United States in 1850 while still in his teens. He settled in Mobile, where John Forsyth, a leading Democrat and newspaper editor who later became US minister to Mexico, took him on as a protégé at his newspaper and introduced him to the world of American politics. Thanks to Forsyth, Hotze also acquired valuable experience in the US diplomatic corps by serving as secretary and then chargé d’affaires with the US legation in Brussels.13

While in Mobile Hotze had become thoroughly immersed in the emerging field of “scientific” race theory. He collaborated with Josiah Nott, leader of the “American School of ethnology,” who had advanced the theory of polygenesis, which argued that whites and blacks were created as separate species. Nott hired Hotze to prepare an American edition of Arthur Gobineau’s Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines (1853), which Hotze translated as The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races: With Particular Reference to Their Respective Influence in the Civil and Political History of Mankind (1856).

Count Gobineau’s theories about the natural superiority of the “Aryan master race” would later inspire Adolf Hitler. Gobineau warned that racial mixing led to the “degeneration” of whites, and that the very capacity of Europeans to conquer and subjugate inferior black and yellow races could lead to white degeneration as a result of imperial expansion. His views on racial hierarchy were also joined to strong prejudice against the leveling effects of democratic reforms at work in Europe and America.

In Gobineau Hotze discovered a wealth of ideas for his defense of the Confederacy in Europe. Gobineau’s powerful critique of egalitarian democracy and liberal philanthropic sentimentality, together with his “scientific” argument for white supremacy, allowed Hotze to present the South not as a rearguard defender of barbaric slavery, but as a scientifically sound model of white supremacy for the new age of imperialism.14

Armed with a sharp mind, a facile pen, and the ability to communicate in English, German, and French, Hotze came fully equipped for his mission in London. By chance he wound up on the same ship that carried James Mason and John Slidell on their second, and less eventful, voyage to Europe. Their arrival at the end of January 1862 marked a new beginning for Confederate diplomacy abroad.

Once in London Hotze immediately set to work. Though operating on a shoestring budget of $750, he managed to make it go a long way. When money ran out he begged contributions from Southern sympathizers in London. While Hotze was not above dispensing gifts of whiskey and cigars to induce British journalists to get the South’s story before the public, he decided to do the job himself. Like other Confederates, he was reaching the conclusion that European journalists were not reliable, especially on matters involving slavery and race.15

Hotze took the extraordinary step of establishing his own newspaper with the innocuous title the Index, A Weekly Journal of Politics, Literature and News. “I have now, after mature deliberation,” he wrote to Benjamin in late April 1862, “concluded to establish a newspaper wholly devoted to our interests, and which will be exclusively under my control.” The paper, he explained, will serve as “a machine for collecting, comparing, and bringing before the public with proper comments the vast amount of important information which is received in Europe through private channels.” “I hope to cause you an agreeable surprise with the first number of the Index.”16

Hotze’s weekly newspaper was soon recognized as the semiofficial voice of the Confederacy abroad. As Hotze had predicted, James Mason was shut out from formal diplomatic communication with Earl Russell, and the Index became an essential conduit for making the South’s case to the government as well as the public. Though its circulation never rose above 2,250, and many copies were distributed gratis to those in the press and government, the Index supplied news to other journals and managed to keep the South’s side of things constantly before readers.17

Everyone understood that the Index was the mouthpiece of the Confederate government, but Hotze strained to make it a reasoned, temperate, and plausible forum for foreigners seeking to understand the American question. He thought it “essential to avoid the great error of American journalism, that of mistaking forcible words for forcible ideas,” and to adopt a “tone of studied moderation.” In revealing instructions to an Italian correspondent, he advised: “Always remember that you have to refute the suspicion of partisanship.” Otherwise, “readers will always be disposed to make allowances for the tendency to represent facts as we wish them to be.” Fortify yourself with facts, he admonished, “dates, names, and quotations,” and avoid giving “undue importance” or “disproportionate prominence” to “isolated expressions of good will in favor of the South.” But this cautious tone did not suit many Southern partisans, who faulted Hotze for “lukewarmness, timidity, or lack of spirit,” and some simply refused to lend their fiery pens to the tepid Index.18

IN LATE FEBRUARY 1862, NOT LONG AFTER HOTZE ARRIVED IN LONDON, a smooth-talking man named Edwin De Leon arrived in Richmond to meet with his friend Jefferson Davis. A sycophant of the first order, De Leon (pronounced “Da-LEE-on”) knew how to appeal to Davis’s vanity and take advantage of his credulity when it came to foreign affairs. Before De Leon was finished, Davis had committed an astounding twenty-five thousand dollars from his own discretionary funds to launch a grandiose program to “educate” the public mind of Europe.

De Leon brought years of experience in journalism and diplomacy and a heavy dose of confidence to the task. Like Benjamin, he was the descendant of Sephardic Jews, whose ancestry traced back to León, Spain. His father had migrated to America and was a physician and successful politician who served as mayor of Columbia, South Carolina. Young Edwin studied law and literature at South Carolina College and later took up his pen in the cause of Young America, a nationalist movement modeled after Mazzini’s Young Italy. By the 1850s De Leon’s bellicose nationalism had found new channels in the emerging Southern rights movement. He moved to Washington and became the editor of a zealous secessionist newspaper.

29. Edwin De Leon, Confederate special agent, headed a well-funded public diplomacy campaign in Europe. (T. C. DE LEON, BELLES, BEAUX AND BRAINS OF THE 60’S)

Some thought it might have been in order to get him and his noisy secessionist views out of town that President Franklin Pierce in 1854 appointed De Leon consul general in Alexandria, Egypt. De Leon traveled widely in Europe during his service in Alexandria, visiting France, England, and Ireland, where he met and married an Irish Catholic woman.19

In Egypt, among the ruins of the earliest recorded civilization, early in 1861 De Leon learned of “the death-knell of the youngest of living nations.” He resigned his post in Alexandria, made his way to Europe in May 1861, and threw his talents into assisting William Yancey and the Confederate commissioners in London and Paris. Operating as an unaccredited agent, De Leon wrote articles for the European press and, by his own self-serving account, vanquished all enemies of the South. From Europe he also took care to rekindle his friendship with Jefferson Davis, whom he knew from his Washington years. Assuming the self-appointed role as the president’s personal envoy, De Leon sent lengthy confidential letters to Davis, advising him of “the exact position of things here” in Europe.20

In early 1862, after Confederate hopes for a diplomatic victory were dashed by the peaceful resolution of the Trent crisis, De Leon decided to return to Richmond, seek an audience with President Davis, and pitch a plan he had been hatching. Before leaving Europe he arranged for a handsome white Arabian horse to be shipped back with him to present as a gift to the president.21

De Leon’s ingratiating approach to Davis stood in sharp contrast to his scurrilous criticism of others in the Confederate high command, which he judged to be infested with old men and old ideas. The Confederate “child was born lusty and vigorous,” De Leon later recalled, but it was being “spoon-fed by ancient politicians” with their “narrow notions.” De Leon had little confidence in Benjamin and less still in Slidell, whom he would grow to resent mightily. Though adept at political wire-pulling in Louisiana, these political hacks, De Leon sniffed, were simply “not the right men” to “advance the Confederate cause abroad.”22

De Leon, of course, thought himself to be the right man for the job, and he seemed to know just how to steer Jefferson Davis’s unworldly mind to the same conclusion. He presented his plan to Davis and Secretary of State Benjamin. Both men were interested in De Leon’s proposal for a well-funded, centrally organized, hard-nosed campaign to “infiltrate the European press with our ideas and our version of the struggle,” as he put it, and appeal “not to sentimental considerations” but to the “substantial interests” of European powers. De Leon also advised that France was disposed to “more friendly feeling towards us than England” and could be induced to aid the South.23

According to De Leon’s retrospective account, he also warned the Confederate leadership that slavery presented the “great stumbling block” to foreign alliance and that antislavery feeling was possibly stronger in France than in Britain. De Leon would later claim that he suggested floating some vague promise of gradual emancipation to answer the cry abroad that this was a war to perpetuate slavery. He blamed the old fogeys of the Confederacy for not taking this sound advice, but there is nothing in De Leon’s correspondence at the time, or in Davis’s and Benjamin’s papers, to lend credence to his claim. The truth was that, far from urging the South along the road to emancipation, De Leon saw his task as instructing foreigners on the benevolent nature of Southern slavery.24

The Confederacy, De Leon told Davis and Benjamin, must reach out to the European public with a vigorous program of education through the press. “Send ambassadors to public opinion in Europe” so that every foreign reader might “imbibe correct information . . . every morning, when he reads his newspaper at breakfast.” Though France was no democracy, he informed Davis, the emperor “will march on with a firmer step, if the ground can thus be made solid beneath his feet.”25

As he took control of the Confederacy’s ill-starred diplomatic campaign in the spring of 1862, Benjamin fully agreed that an aggressive program of public diplomacy abroad was required. He also supported the idea of a strategic shift toward France. But Benjamin instinctively distrusted De Leon and preferred that his Louisiana friend John Slidell be fully in charge. He correctly anticipated that De Leon’s very presence in France would irritate Slidell, who liked to work alone. De Leon convinced Davis, however, that it was essential to keep propaganda operations separate from Slidell’s diplomatic efforts and that, with his experience in journalism, he was made for the job.

For the first time, Davis became directly involved in Confederate diplomacy in Europe by making a major financial commitment to further its success. Though he would report officially to Benjamin, De Leon saw himself as the president’s man, and he would operate largely on his own instructions with little supervision from Benjamin, Slidell, or anyone else, and with sorry result in the end. Nor were De Leon’s operations coordinated with those of Henry Hotze, who had launched the Index in May as the voice of the Confederacy abroad. De Leon arrived in Europe at the end of June with a large purse, an ego larger still, and an irrepressible jealousy toward the two men, Slidell and Hotze, who might have been the most help to his mission as Confederate ambassador to public opinion.26

Whatever his misgivings about De Leon, Benjamin was eager for the Confederacy to get its story before the European public, and he seemed to share De Leon’s and Hotze’s core idea that the message be controlled by Confederate agents and not left to foreign volunteers. “It is not wise to neglect public opinion,” he wrote to his envoys on April 12, 1862, “nor prudent to leave to the voluntary interposition of friends often indiscreet, the duty of vindicating our country and the cause before the tribunal of civilized man.” While Union agents such as John Bigelow were taking a strategic turn toward enlisting native advocates of their cause, the Confederacy turned inward to draw on its own talents and its long-insulated ideas about the morality of slavery.27

Benjamin’s April 1862 instructions to Mason and Slidell explained that the dire situation of the Confederacy required “a more liberal appropriation” of funds for foreign service. “With enemies so active, so unscrupulous and with a system of deception so thoroughly organized as that now established by them abroad, it becomes absolutely essential that no means be spared for the dissemination of truth and for a fair exposition of our condition and policy before foreign nations.” With Hotze’s Index and De Leon’s generous budget, the Confederacy was about to make use of a considerably larger megaphone. The question remained, what “truth” did the South want to broadcast to the world?28

JOHN SLIDELL AND JAMES MASON HAD ARRIVED IN EUROPE AT THE end of January 1862, nearly three months after their ill-fated voyage on the Trent began. The two men proved to be more helpful to the South as captives, inflaming the British sense of honor, than they were after their release. The British press and public displayed a cool indifference toward the Confederate envoys in London, and newspapers did little more than announce their arrival. Henry Hotze, who had come over with them, was disconcerted to learn that the London Times had recently scolded Mason and Slidell for being “persistent enemies and assailants of Great Britain and her interests throughout their public lives.” Hotze blamed it all on Seward’s special agent Thurlow Weed, “who is said to have at his disposal a large secret service fund for that purpose.”29

If Confederate fortunes depended on the reputation and charm of its diplomatic messengers, the choice of James Mason for London could not have been worse. Descended from Virginia aristocrats, he was the grandson of George Mason, who was hailed as the father of the Bill of Rights. James Mason instead was best known as the author of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. British readers of Uncle Tom’s Cabin would recognize this odious law as the one that would have forced the fictional Ohio senator and his wife to return the runaway Eliza and her baby back across the icy Ohio River to slavery.

Although he enjoyed long service as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Mason had no diplomatic experience, and it showed. He detested the “extreme democracy” that had overtaken America and made a point of telling his British acquaintances that he felt completely at home among their aristocracy.

The admiration was not mutual. Even ardent friends of the South in London described Mason as slovenly in dress and manners. One uncharitable observer described him as he sat in the gallery of the British House of Commons, appearing “coarse, gross, ponderous, vulgar looking,” and “badly dressed.” He chewed tobacco “furiously,” and his spit “covered the carpet.” Mason’s tobacco habit also drew rebuke at a private party one evening when the host, though a fervent supporter, had to ask him to stop spitting in his home.30

Soon after his arrival, Mason managed to arrange a private interview with Foreign Secretary Earl Russell on February 10, 1862. As usual, Russell kept it unofficial by meeting at his private home on Chesham Place. Russell was as cold as ice, and he let Mason do most of the talking. As instructed, Mason explained that the blockade was ineffective and that Britain, therefore, had no obligation to honor it. This was coming from a man who had been abducted at sea and whose dispatches to and from Richmond would be routinely delayed for months or intercepted by the Union navy. If Russell was amused by the irony, his cold demeanor gave no hint of it. He promptly closed the meeting by saying they “must await events” and wishing Mason an “agreeable” stay in London. “On the whole,” Mason summarized the meeting for Benjamin, “it was manifest enough that his personal sympathies were not with us.”31

30. James Murray Mason, Confederate envoy to Britain. (MATHEW BRADY PHOTOGRAPH, NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

MEANWHILE, JOHN SLIDELL’S WELCOME TO PARIS AT THE END OF January 1862 was far more auspicious. Paris was teeming with Southern expatriates, many of them Louisiana Creoles, nos freres de Louisiana (our Louisiana brothers), as they were known in the Tuileries Palace. A group of ebullient students, many from New Orleans, met Slidell at the Paris railway station and burst into song: Bienvenu, notre grand Slidell, Au coeur loyale et l’âme fidèle, euphoniously welcoming “our great Slidell, of loyal heart and faithful soul.”32

Paris seemed captivated by Southerners, who often felt more comfortable among the French than among Londoners with their antislavery prejudices. Thomas Evans, an American expatriate who had won fame as the dentist to Europe’s royalty, was gravely concerned about the influence of Southerners in Napoleon III’s court. As Evans later recorded in his memoirs, “A very considerable part of the territory of the Confederacy once belonged to France,” and many still regarded New Orleans as “a city of their own people.” “Southern ladies, who formed a brilliant and influential society” in Paris, Dr. Evans lamented, “vied with each other in their endeavors to enlist in support of their cause everyone connected with the Imperial Court.”33

One evening two weeks later, Slidell attended the Théatre Bouffes-Parisiens with Mathilde, his Creole wife, and his secretary, George Eustis. Southern partisans in the audience began applauding as they took their seats. Slidell rose and bowed graciously once and then again as the ovation continued. A little while later, when William Dayton, the US minister, entered the theater, some in the crowd began hissing loudly. Two gendarmes rushed to quell what they feared might become an unruly demonstration.34

This demonstration of Southern support may have been staged by parties unknown for the benefit of Emperor Napoleon III, who witnessed the entire affair from his box. At the intermission the emperor went backstage to pay his respects to the star performer known as Sophie Bricard, a femme fatale from New Orleans and a fiery partisan of the South. Mademoiselle Bricard seized the opportunity to introduce the emperor to Slidell as “the representative of my suffering country” (Voilà, Sire, voilà le représentant de mon pays souffrant!) “The South is fighting for freedom,” she implored the startled emperor. “On my knees, I supplicate your Majesty. Give us the friendship of France!” Napoleon III stepped back, somewhat startled, and then turned and shook hands with Slidell without saying a word before making a hasty exit from this diplomatic faux pas.35

John Slidell could be arrogant and temperamental, sometimes for effect, but he was by far the savviest member of the Confederate diplomatic corps. Schooled in the cunning world of Louisiana politics, he was also a seasoned diplomat with experience as special agent to Mexico in the 1840s. Born in New York in 1793, Slidell attended Columbia University, went into business, and then moved to the bustling frontier city of New Orleans to make his fortune. He married Maria Mathilde Deslonde, heiress of a wealthy French Creole family, and soon emerged as a major figure in Louisiana politics. Slidell was fully equipped to navigate the labyrinth of European courts with a savoir faire no other Confederate agent came close to commanding.36

31. John Slidell, Confederate envoy to France. (MATHEW BRADY PHOTOGRAPH, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Not least of Slidell’s assets in France were Mathilde and their two beautiful daughters, Marie Rosine and Marguerite Mathilde, whose marriages to European aristocrats and bankers would soon become the toast of Parisian society. With his leonine mane of gray hair and his distinguished bearing, Slidell cut an impressive figure in Paris. He spoke French with fluency and seemed completely at ease among the aristocrats at court, enjoying the camaraderie of gentlemen over card games at the casino or at horse races at the elite Jockey Club. Despite his unofficial diplomatic status, Slidell and his wife were invited to court receptions, where they managed to endear themselves to Empress Eugénie, whose sway over her vacillating husband made her a valuable asset.

Slidell cultivated other friends in high places. The Duc de Morny, the emperor’s half brother, enjoyed Slidell’s company at the casino and openly favored the South and promoted its recognition inside the court. The Duc de Persigny, Napoleon III’s zealous minister of the interior who was responsible for press censorship, among other duties, also befriended Slidell and did all he could to help the Southern cause.37

Slidell operated with unusual advantage insofar as he learned everything that was going on inside the Quai d’Orsay, home of the French Foreign Ministry, thanks to an informant by the name of Pierre Cintrat. “I have a friend holding a high position in the foreign office and on the most confidential terms with Thouvenel,” the French foreign secretary, Slidell discreetly reported to Richmond. As director of the foreign office archives, Cintrat saw everything, all the incoming and outgoing diplomatic correspondence, and he even knew how to decipher the encrypted messages. There is no hint that Cintrat received any inducement from Slidell, and he may even have been operating on instructions from the emperor. In any case, Slidell’s mole at the Quai d’Orsay was guiding his every move.38

It did not take a spy inside the foreign office for Slidell to learn, as he reported dolefully to Richmond, that the French “regret that slavery exists amongst us” and hope for “its ultimate but gradual extinction.” Slidell’s usual response was to divert the conversation to “more agreeable topics.” “I make it a rule to enter into no discussion on the subject,” he wrote to Richmond, for many of “our best friends” “have theoretical views on the subject which in general it is not worth while to combat.”39

Slidell would appeal to French national interest, not public sentiment. Immediately after arriving, he set up an unofficial meeting with Édouard Thouvenel, the French foreign secretary. He reported to James Mason afterward that “the Emperor’s sympathies are with us” and “that he would immediately raise the blockade and very soon recognize us, if England would only make the first step, however small, in that direction.”40

Not long after Slidell arrived, the Tripartite Alliance between France, Britain, and Spain fell apart in Mexico in early April. As France prepared to take on Mexico alone, it became clear that for the Grand Design to succeed, the South must also succeed. The Civil War would need to be continued while the French conquered Mexico, and beyond that Napoleon III wanted an independent Confederacy to serve as a buffer state between a powerful Anglo-Saxon republic to the North and a Latin monarchy in Mexico. In turn, if the Confederacy needed French support in its struggle, it would be forced to concede any ambitions of its own to take over Mexico or western sections of the United States.41

Precisely as the French took on their “civilizing” mission in Mexico in April 1862, in Richmond the new secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, was laying out the Confederacy’s new French strategy. His instructions to Slidell began by gingerly pointing out that French and British interests were “distinct, if not conflicting.” Slidell was to widen that distinction by offering what can only be described as a magnificent bribe to France.

The bribe involved a highly lucrative, long-term, and exclusive commercial treaty between France and the Confederacy. By this commercial “convention,” Benjamin explained, France would be allowed to export its products “into this country free of duty for a certain defined period,” but France would have to break the blockade to deliver its goods. French imports, including arms and powder, Benjamin estimated, would sell in the South at between two and five times what they cost to produce in Europe, which alone promised enormous profits to French merchants.

To sweeten the offer, and cover costs of a French naval escort to protect the merchant ships, Benjamin offered gratis one hundred thousand bales of cotton, worth approximately 63 million francs (more than $12.5 million) as a “subsidy for defraying the expenses of such expeditions.” Together with the profits on European goods brought to the South, Benjamin estimated the total gain would “scarcely fall short of 100,000,000 francs” (about $20 million). “Such a sum,” Benjamin spelled out, “would maintain afloat a considerable fleet for a length of time quite sufficient to open the Atlantic and Gulf ports to the commerce of France.” The Confederacy was, in effect, offering to pay whatever it cost to hire the French navy to break the Union blockade.42

Alas, Benjamin’s April 1862 instructions did not reach Slidell’s hands until early July—underscoring how effective the blockade had in fact become. Fortuitously for the Confederates, news of their stunning victories against Union general George McClellan’s abortive Peninsular Campaign to seize Richmond arrived at the same time. Slidell was ebullient, and he wasted no time in getting the offer before Napoleon III. Slidell’s friend the Duc de Persigny helped arrange a private interview for him with the emperor on July 16 at the latter’s private vacation home in Vichy, far from the prying eyes of the press. Aside from their brief backstage encounter in February, this would be the first meeting between the two men.

The emperor, Slidell recounted later for Benjamin, “received me with great kindness,” “saying that he was very happy to see me and regretted that circumstances had prevented his sooner doing so.” He “invited me to be seated,” which was always taken as a good sign in the nuanced world of diplomacy. Napoleon III immediately confided in Slidell that, though he was officially neutral and valued the role of the United States as contrepoids (counterweight) to Britain, he personally favored the South because it was “struggling for the principle of self-government.” More than once the emperor expressed irritation with Britain for failing to answer his repeated calls to recognize the South, mediate a peace, or otherwise intervene in the American war. What could be done, he wanted to know from Slidell, to bring the war to an end?43

This was the perfect entrée for Slidell to unveil Benjamin’s proposal for a special relationship between their two countries and to lay out the terms of the cotton bribe. Knowing that Napoleon enjoyed speaking English, Slidell requested permission to proceed in “my own tongue.” He then took command of the conversation while the emperor nodded in ascent and asked occasional questions. Slidell explained the terms of the exclusive commercial alliance and its handsome “subsidy” of one hundred thousand cotton bales. This “did not seem disagreeable” to Napoleon, Slidell reported.

“How am I to get the cotton?” the emperor inquired with apparent innocence. Slidell answered bluntly that France would have to send a naval fleet, break the blockade, and be prepared for war with the United States. He hastened to point out that this fitted nicely with France’s plans to reinforce the Mexican expedition, which would, in any case, require “a fleet in the neighborhood of our coast strong enough to keep it clear of every Federal cruiser.” The French navy, Slidell promised, would easily rout the fleet of “second-class” ships the Union had cobbled together. The emperor seemed quite flattered.

But Napoleon III was very concerned that his Mexican venture would provoke a clash with the United States, and he told Slidell as much. Going beyond Benjamin’s instructions, Slidell took the opportunity to suggest something more than mere commercial alliance. Once Napoleon recognized the Confederacy, the South would be in a position to “make common cause with him against the common enemy” by supporting Napoleon’s Grand Design for a monarchy in Mexico. The Confederacy had no Monroe Doctrine, Slidell made clear. It wanted nothing more than “a respectable, responsible, and stable government established” on its southern border and “will feel quite indifferent as to its form.”44

When the emperor raised doubts about the wisdom of recognition at this hour, Slidell drew on the humanitarian plea Benjamin had rehearsed for him. Slidell implored Napoleon, as one who had “exercised so potent an influence over the destinies of the world,” to act in the “interests of humanity” and help end the senseless strife that was ravaging both belligerents and threatening great harm to Europe’s cotton industry. Britain, Slidell added shrewdly, “seemed to have abdicated the great part which she had been accustomed to play in the affairs of the world” and had adopted a “selfish” policy of national interest alone.

Warming to the task, Slidell played his Louisiana French card and with apparent magic effect on the emperor. “Your Majesty has now an opportunity of securing a faithful ally, bound to you not only by the ties of gratitude,” but also of “common interest and congenial habits.” “Yes,” the emperor responded proudly, “you have many families of French descent in Louisiana who yet preserve their habits and languages.” Slidell assured him (ironically still in English) that in his family, “French was habitually spoken,” as it was in much of Louisiana.

The interview had gone on for an impressive seventy minutes, as Slidell carefully reported to Richmond. When he rose to leave, the emperor shook his hand. “I mention this fact, which would appear trivial to persons not familiar with European usages and manner,” he informed Benjamin, “because it affords additional evidence of the kindly feeling manifested in his conversation.”45

Slidell returned from Vichy thinking that, thanks to Benjamin’s cotton offer and Napoleon’s campaign in Mexico, he had suddenly opened the path to Confederate diplomatic victory. “While I do not wish to create or indulge false expectations,” he told Benjamin, “I will venture to say that I am more hopeful than I have been at any moment since my arrival in Europe.”46

WHILE SLIDELL WORKED HIS WAY INTO THE INNER CIRCLE OF FRENCH power, the Confederacy’s continental public relations campaign was still awaiting direction from Edwin De Leon. The Southern ambassador to public opinion had been detained in Nassau, apparently by the blockade that was supposed to be so ineffective, and did not arrive in London until the end of June 1862. He stayed in London meddling in Mason’s and Hotze’s affairs; writing pieces for the London press; collaborating with James Spence, the South’s advocate from Liverpool; and arranging a private interview with Lord Palmerston. De Leon quickly came to view Hotze’s Index as utterly useless, since it was transparently an organ of the Confederate government, but he also seemed annoyed that Hotze had his own well-oiled, intelligent propaganda operation in place.47

In any case, De Leon was convinced that the Confederacy’s fortunes lay in France, not England. He left for Paris in July 1862, quickly set up offices, spent money freely, and soon enlisted a large corps of French journalists and editors willing to hire out their pens to the South. Convinced that it was a waste of money to try to influence readers in Paris, where liberal opinion ran strong, De Leon concentrated on the provincial press, which he thought more important in bringing popular pressure to bear on Napoleon III’s government. Within a short time he had well over two hundred French journalists on the Confederate payroll.48

While De Leon’s “bought opinions,” as he called them, were doing what they could to build public support for the Confederacy, he decided the French also needed to hear “the truth” from a native son of the South. He prepared a thirty-two-page pamphlet, La vérité sur les États Confédérés d’Amérique, for publication in Paris in August 1862. It came on the heels of Slidell’s cotton bribe as well as welcome news from the front that Confederate forces were advancing into Maryland.49

De Leon’s “truth” about the South offered French readers the perspective of a knowing witness to its valiant struggle for independence. He dismissed recent Union victories, including the capture of New Orleans, with the clever argument that these incursions would only inflame the South, “which battles for its homes and lands, for its liberty and the honor of its women.” New Orleans was naturally of great interest to the French, and this last reference was one of several pointed reminders of Union general Benjamin Butler’s infamous “woman’s order,” in which he warned that any woman caught insulting Union soldiers was “liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation,” meaning she would be treated as a prostitute. Southern sympathizers abroad interpreted it as license to rape Southern women.50

Unlike Slidell, who preferred to divert arguments about slavery to more “agreeable subjects,” De Leon set out to educate the French about the South’s special brand of slavery. His pamphlet ridiculed “Madam Stowe’s novel,” which “represents the slave’s goal to . . . massacre one’s master.” Instead, he emphasized the loyalty of the slaves who “have contributed greatly to the South’s strength” by their resistance to such “false friends” from the North. “The negro knows very well by experience that the Yankee has no real sympathy for its race.” Blacks were despised and segregated in the Northern cities, he told the French, and far from being liberated by the invading Union army, De Leon claimed, they were being forced to carry out hard labor as “contraband” of war. The pamphlet appeared not long before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation would transform many of these contraband laborers into Union soldiers.51

De Leon went on to draw a flattering portrait of Jefferson Davis, comparing him to the universally admired George Washington in his military valor and statesmanlike character. Readers of De Leon’s booklet were also treated to an engraved portrait of Jefferson Davis that made him look noble, robustly healthy, and about twenty years younger. When meeting foreign dignitaries, De Leon made it a practice to hand them copies of the portrait, never failing to contrast the aristocratic bearing of the Southern leader with the homely, rustic visage of Abraham Lincoln.52

The most novel aspect of De Leon’s booklet was his claim that the South was Latin, the same idea that Slidell had aired with some success at Vichy. Northerners, De Leon explained, descended largely from “the races of Anglo-Saxon origin,” but “the South was principally populated by a Latin race.” Those Anglo-Saxons who remain in the South, in any case, trace their origin to the royalist Cavaliers who defended England’s King Charles against the overzealous Puritans.53

Thus, General Butler, the “descendant of the Puritans,” now “applies himself in making war against women” in New Orleans, the bastion of French culture in the South. The Puritan North had built its army “in large part of foreign mercenaries” made up of “the refuse of the old world.” Chief among these dregs of European society were “the famished revolutionaries and malcontents of Germany, all the Red republicans, and almost all the Irish emigrants to sustain its army.” The South offered a bulwark against the tide of Northern Puritanism and the pollution of its immigrant hordes. “The seeds of discord” were of long standing, he added, and “France and England have never been as divided as the North and South have been in the past twenty years.”54

De Leon was immensely satisfied with his effort to educate the French, and he wrote to Judah P. Benjamin in October 1862, eager to burnish his achievement. To counteract the pernicious efforts of the North in “the manufacture of public opinion,” he explained, “I have been compelled to use extraordinary exertions, which I am happy to say, have wrought great results within the last two months.” De Leon said he was surprised to find that the slavery question, which had “been dropped in England,” was “made the great bugbear in France” and that friends of the South were “shuddering at the epithet esclavagiste [supporter of slavery], with which the partisans of the North were pelting them.” He attributed this strange feeling for “the supposed sufferings of that race” to “the sentimental side of the French character.” De Leon may not have noticed that among educated Parisians, especially the young, blacks enjoyed a level of acceptance unknown in America.55

If the French did not always take his lessons to heart, De Leon nonetheless felt confident that his pamphlet would serve as a “text book for our friends in the press.” He summarized the most brilliant points of his argument for Benjamin: “The South is able to vindicate her independence without foreign assistance, and is rapidly doing so,” and “has nothing to apologize for in her peculiar institution but has ever been the best friend of the black race.”56

Even some of his fellow Confederates may have thought that the best thing that could be said for De Leon’s tone-deaf pamphlet was that it went largely unnoticed by the French public. Paul Pecquet du Bellet, a Louisiana Creole who had lived in Paris for years, was sympathetic to the Southern cause but found De Leon utterly self-deluded. He was also annoyed that De Leon had not consulted him before going to print, for he had established good connections with French journalists while publishing his own pieces in support of the South. With one exception, French journals maintained a “disdainful silence” on De Leon’s polemical pamphlet. As Pecquet du Bellet put it gingerly, De Leon was not quite au fait with the current state of conversation on the American question. Malakoff, the New York Times correspondent in Paris, remarked in a similar vein that De Leon, though pretending to offer a rare eyewitness account of the South, seemed unaware of how trite his arguments had become and what little effect they had on European opinion. Then there was the “peculiar style” of De Leon’s French, which editors told Pecquet du Bellet was a bit too “Americanized” for French tastes, and was described by one editor as “broken” and indecipherable.57

The problem went much deeper than language and style, in any case. The French knew that slavery, not supposed cultural differences between a Latin South and Puritan North, lay at the heart of the American conflict. De Leon’s effort to “enlighten” the public as to the “true” nature and benevolence of the South’s brand of slavery was of little help to the Confederate cause.58

Though certainly no friend of the North, Pecquet du Bellet was immensely impressed with how its agents skillfully managed the French press on the slavery question. He credited Seward and Dayton (he apparently did not know of Bigelow’s key role) for the skill with which the Union by late 1862 began to align its cause with the red republican cry for Emancipation, Liberté, Fraternité, Egalité. Eventually, he recalled sarcastically, newspaper editors “trembled at the mere idea of defending those ‘Southern Cannibals’ who breakfasted every morning upon a new born infant negro.”59

Henry Hotze was also frustrated by the “sentimentality” and obstinacy of the French on the slavery question. Outside the emperor and his close circle of advisers, who he thought accepted the South’s defense of white supremacy and slavery, “all the intelligence, the science, the social respectability, is leagued with the ignorance and the radicalism in a deep-rooted antipathy” against the South. In contrast to the French, Hotze found the English, “accustomed to a hierarchy of classes at home and to a haughty dominion abroad,” and therefore able to grasp the “hierarchy of races.” But the French, “the apostles of universal equality,” are embarrassed by such ideas. The emperor dares not “offend so universal a feeling” and therefore could not act in the best interests of his country. That, Hotze summarized, was the problem the South faced in France. Financial interest, European rivalries, and the manifest destiny of Napoleon III’s Grand Design all pointed toward a common cause with the South. The problem was the stubborn mind of the French people who would not accept the South’s version of la vérité.60