Call the great American Republic. She is, after all, your daughter, risen from your bosom; and . . . is struggling today for the abolition of slavery so generously proclaimed by you. Help her to escape from the terrible strife waged against her by the traders in human flesh. Help her, and then place her by your side at the great assembly of nations—that final work of the human intellect.

—GIUSEPPE GARIBALDI, “To THE ENGLISH NATION,” SEPTEMBER 28, 1862

THE SLAVERY QUESTION WAS AN OBSTACLE TO INTERNATIONAL recognition of the South, but in the summer of 1862 it also burdened popular enthusiasm for the Union overseas. A full year had passed since Giuseppe Garibaldi posed the simple question that still seemed unanswered: why was America waging war against the slaveholders’ rebellion without waging war against slavery?

The long summer of 1862 ended with the most serious threat of foreign intervention during the entire four years of war. The most familiar narrative of this perilous season of war dwells on the Confederate invasion of Maryland being turned back at Antietam, then Lincoln issuing the long-awaited Emancipation Proclamation, which came in the nick of time to upset plans among the European powers to end the war on terms of separation. But the truth is that initially the proclamation made intervention more likely. Because of emancipation, which many leaders feared would ignite racial mayhem and throw the world cotton economy into chaos, some wanted to move quickly to mediate an end to war. It was not Antietam, nor was it Lincoln’s emancipation decree that upset the Great Powers’ plans to intervene. The tide of events was moving in favor of the South that summer and fall of 1862. As the summer wore on, the Union’s Peninsular Campaign to capture Richmond lay in shambles. The Union army, led by General George McClellan, was in retreat, and the Confederate army was advancing northward to surround and capture Washington. Then, unexpectedly, a march on Rome led by Giuseppe Garibaldi and his army of Red Shirts created a public uproar across Europe, ignited huge riots in England, forced a shake-up in Napoleon III’s government, and suddenly left Lord Palmerston’s British cabinet to contemplate the unhappy prospect of facing the United States in war alone. Without ever leaving Italy, the Hero of Two Worlds and his band of Red Shirts inadvertently upended the plans of the Great Powers to intervene in support of the South.1

IN WASHINGTON ALL SUMMER THE LINCOLN ADMINISTRATION HAD been making a deliberate turn toward a war of abolition. During the secession crisis Lincoln had committed to safeguarding slavery in the Southern states in part to delegitimize in the eyes of the world what he and Seward characterized as a rebellion without cause. In the summer of 1862 Lincoln at last concluded that he must act against slavery to legitimize the Union cause, especially in the eyes of liberal foreigners who expected America to fight Liberty’s war. Lincoln was slow to embrace emancipation in part because of constitutional constraints. He also feared that Northern soldiers and civilians simply would not be willing to sacrifice for a war to emancipate black slaves. Already pro-Southern Copperheads in the North were arousing opposition to emancipation and calling for peace and restoration of the “Union as it was.” The voice of democracy was about to be heard in the November congressional elections. Lincoln had framed the war as a defense of democratic principles; ironically, it seemed that democracy might prevent him from using the one weapon he realized could win the war: emancipation.

William Seward had parallel concerns about overseas reactions to an emancipation edict. He was genuinely troubled that an emancipation edict would redound to the benefit of the South. Europeans viewed emancipation as a catastrophic threat to the cotton industry, he was certain, and instead of hailing emancipation as a higher moral cause, the world would see it as the last desperate act of a nation, unable to win on the battlefield, resorting to racial conflagration to save itself.2

One after another of Seward’s diplomats abroad had tried to persuade him otherwise. The foreign public was perplexed as to why an antislavery party was fighting to maintain a union with slaveholders, yet Seward was instructing them to avoid any discussion of the moral principles involved in the war. This had “positively stripped our cause of its peculiar moral force,” Carl Schurz, the frustrated US minister in Spain despaired. Seward’s stance seemed to lend credence to the cynical view of Confederate sympathizers abroad that the war was merely a contest between Southerners who wanted to “be free and independent” and Northerners who “insisted on subjugating and ruling them.”3

Schurz was the first to fully sound the alarm that European popular support depended on the Union placing the war “upon a higher moral basis” than simply defending its right to exist. No Union diplomat was more attuned to liberal Europe than Schurz. As a young student at the University of Bonn, he had been preparing for a quiet career as a history professor when the Revolution of 1848 suddenly changed everything. He joined the armed rebellion against the Prussians, and when it failed he sought asylum in Switzerland and later moved to Paris. After Napoleon III’s autocratic regime expelled him for revolutionary activities, he moved again, this time to London, and in 1852, with his wife, Margarethe, he made his way to America and eventually came to Wisconsin. Schurz completely immersed himself in America’s language, culture, and politics, and he channeled his revolutionary passion into tireless efforts on behalf of the Republican Party.4

To Schurz’s impassioned plea from Madrid in September 1861 that liberal Europe would support a war against slavery and make it impossible for the aristocratic government leaders to favor the South, Seward had answered with a deflating rebuke that left Schurz in utter despair. “This struggle fills my whole soul,” he wrote mournfully to Seward. “The cause which is at stake is the cause of my life. . . . I feel as if I wasted the rest of my strength and labor when not devoting it to the service of the country at a moment like this under these circumstances.” He wanted out of diplomatic service, which he now realized was a misuse of his talent and experience so long as Seward controlled the message. He had already written to Lincoln asking to be recalled, taking the occasion to express “grave doubts” about the country’s foreign affairs but not daring to say all he thought about Seward’s uninspired leadership.5

Seward grudgingly granted Schurz a leave of absence, but he was not eager to have him back in Washington, filling the president’s ears with his radical ideas. Schurz left Madrid in December as the Trent crisis was coming to its head. He stole across his native Germany by night and made his way to Hamburg, where Margarethe and his children were waiting. They made a rough, storm-tossed crossing and arrived in New York in late January 1862.

Schurz immediately headed straight for Washington, going first to the State Department to report to Seward. Busy with other duties, Seward asked him to wait and meet him later. Schurz promptly went next door to the White House. He was worried that Lincoln might be upset with him for leaving Madrid, a post Lincoln had battled Seward to secure for his German friend, and he was greatly relieved that Lincoln greeted him with the “old cordiality” and invited him to talk in his office.6

Assuming that Seward had not shown Lincoln his September plea for emancipation but feeling it improper to ask whether that was so, Schurz began to summarize its main points when suddenly the door opened and in popped the head of William Seward, who had found time to follow him there. “Excuse me, Seward,” Lincoln said, holding up his hand, “excuse me for a moment. I have something to talk over with this gentleman.” Seward realized that Schurz was going over his head and, no doubt, was troubled by what this radical was about to tell the president. But Lincoln wanted to hear what his German friend had to say. Schurz remembered vividly that Seward “withdrew without saying a word.”7

Schurz resumed his exposition on the European situation while Lincoln “listened to me very intently, even eagerly,” and without interruption. European governments wanted to see democracy fail in America, he told the president, but there was a vast public with liberal instincts waiting eagerly for the Union to place the war on a “higher moral basis” and proclaim emancipation as its goal. As he drew to a close, Lincoln sat “for a minute silently musing.”

According to Schurz, it was as though he had been digesting his thoughts for some time: “You may be right. Probably you are,” he said. “I have been thinking so myself. I cannot imagine that any European power would dare to recognize and aid the Southern Confederacy if it became clear that the Confederacy stands for slavery and the Union for freedom.” These were almost exactly the words Schurz had written to Seward the previous September, and it seemed clear that Lincoln had read Schurz’s plea from Madrid.8

Lincoln told Schurz he accepted the main point that “a distinct anti-slavery policy would remove the foreign danger.” But he feared the American public was not “sufficiently prepared” and that a precipitous move toward an “abolition war” would undermine support. The Union had to defeat the rebellion militarily, Lincoln reasoned. Otherwise, any pronouncement against slavery would “be like the Pope’s bull against the comet,” a metaphor Lincoln used more than once to evoke the futile exercise of power.9

Schurz was among a growing coterie of passionate abolitionists who were exasperated with the administration’s “dilatoriness” on the slavery question. But he came away from his meeting at the White House that day with a new understanding of the president’s values and political instincts. Lincoln was not opposed to emancipation, nor did he scorn its advocates. Instead, he “rather welcomed everything that would prepare the public mind for the approaching development.” Abolitionist critics Charles Sumner and Horace Greeley were, to him, more allies than adversaries. Lincoln typically answered them, sometimes in public letters, by engaging their arguments and posing questions rather than defending fixed ideas.10

The fundamental difference of opinion between Schurz and Seward reflected very different assessments about the way European powers decided foreign policy. Seward viewed European powers as motivated solely by national interests rather than moral sentiment. They calculated commercial or geopolitical advantage rather than the public good. Because monarchies were not as beholden to popular will, he reasoned, public opinion mattered less to European leaders than it did to America’s democracy.

What Schurz was trying to explain to Seward and Lincoln was that European monarchies might wish the worst for the American republic and prefer to see it fragmented and weakened. But ideology and moral purpose mattered greatly to the broad European public, and though popular discontent might not be registered at the polls, European rulers still feared what might be unleashed at the barricades. Memories of 1848 still loomed over the crowned heads of the Old World, and the voice of opposition was never far away from the threat of revolution.11

Lincoln’s domestic policy and Seward’s foreign policy began from the same premise the president laid before the world in his first inaugural address: the Union was defending the basic right of a nation to self-preservation in the face of domestic rebellion. Yet long before emancipation was adopted, Lincoln in his public addresses and Seward in his diplomatic instructions were enveloping this narrow goal of national preservation within a loftier idea that the war was a trial of the broad principles of government by the people everywhere on earth. If a disgruntled minority was unwilling to abide by the will of the majority, the idea that people could govern themselves would be an utter failure. The outcome of the American contest would decide nothing less than the fate of democracy.12

Lincoln employed universalizing language to place the American Civil War within the broadest framework possible in space and time. This was “essentially a people’s contest,” he explained in his 1861 Fourth of July message to Congress. “On the side of the Union it is a struggle for maintaining in the world that form and substance of government whose leading object is to elevate the condition of men; to lift artificial weights from all shoulders; to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all; to afford all an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life.” “It presents to the whole family of man, the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy—a government of the people, by the same people—can, or cannot, maintain its territorial integrity, against its own domestic foes.”13

Seward also employed universalizing language in his diplomatic correspondence and referred often to the historic struggle and far-reaching consequences involved in the American conflict. Without endorsing emancipation, he frequently made broad appeals to the cause of human freedom, as in his instructions to Henry Sanford on negotiations with Giuseppe Garibaldi: “Tell him . . . that the fall of the American Union . . . would be a disastrous blow to the cause of Human Freedom equally here, in Europe, and throughout the world.”14

Lincoln’s goal of preserving the American Union was always much more than just an amoral placeholder for emancipation. From the outset, he and Seward had elevated the Union’s right to exist to a higher plane as the defense of the universal republican experiment. While the idea of America’s conflict as a trial of democracy resonated powerfully abroad, the appeal to ideals of liberty and equality rang hollow without emancipation.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1862 LINCOLN LED, AND SEWARD RESISTED, A decisive turn toward an emancipation policy that the president hoped would sharply define the Union’s moral purpose and thwart foreign intervention. Lincoln did not need convincing that slavery was a great moral evil. Lincoln’s moral abhorrence of human slavery never faltered from the time when, as a young man visiting New Orleans, he saw human beings sold at auction like livestock. His condemnation of slavery also drew on a strong republican political ideology. He hated slavery, as he explained in an earlier speech, “because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself,” but also “because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world.” Slavery “enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and . . . forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty.”15

Lincoln’s moral and ideological condemnation of slavery remained firm and steady, but what he thought ought to be done about ending slavery took a crucial turn by the summer of 1862. Though the Constitution did not grant the president the power to end slavery, he came to realize that the war provoked by slaveholders handed him the best remedy to rid the republic of slavery and end the war. It was as commander in chief during a war to defend the republic against insurrection, not as chief executive, that Lincoln would proclaim emancipation.16

Grave political pressures arising from Northern advocates of peace, along with military reverses in the field, hastened Lincoln’s reckoning with slavery. He later described the mood of that perilous summer of 1862: “Things had gone on from bad to worse, until I felt that we had reached the end of our rope. . . . [W]e had about played our last card, and must change our tactics, or lose the game!” Lincoln baldly admitted it was a desperate move motivated by military necessity, but he had been moving in this direction for some time.17

Lincoln and the Republican Party had been advancing piecemeal abolition measures for months. In March 1862 Congress passed legislation forbidding Union officers from returning fugitive slaves to their masters. In April the federal government exercised its local sovereignty to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. In June it outlawed slavery in all federal territories. In July Lincoln signed the Second Confiscation Act, permitting the liberation of slaves of rebel owners. The president also publicly encouraged border states to pass legislation for the gradual emancipation of their slaves and even offered federal support for compensation to owners. The lack of cooperation from the states, however, helped set the stage for a presidential edict as the only viable path toward ending slavery. By midsummer 1862 Lincoln had all but given up on any possibility that the states would lead the way to legislating the end of slavery, even with federal inducements. At the same time, the president felt that a war-weary public, and especially the soldiers, would be more prepared to support abolition if that was what it took to end the war.18

On July 13, 1862, during a carriage ride in Georgetown, Lincoln explained what until now had been his secret emancipation plan for the first time to William Seward and Gideon Welles, the secretary of the navy. According to Welles, who recorded it all in his diary, Seward went along with the president at the time, saying his strategy was “justifiable” and “expedient.” But Seward’s private and diplomatic correspondence shows that he, in fact, remained firmly wedded to the view that emancipation, instead of defusing the “foreign danger,” would inflame it.19

When Lincoln called a cabinet meeting for July 22 to present his plan for emancipation, Seward came fully armed and ready to play his hand. Lincoln’s plan to free the slaves in rebel-controlled territory, by this point, had been linked to an even more controversial plan to enlist free blacks and slaves who made their way to the Union army. In a lengthy, passionate speech, Seward played on the alarming image that foreigners would have of slaves in arms. Foreign powers, some of whom had experienced their own colonial uprisings against whites, he cautioned, would see in this a frightening summons to “servile insurrection,” arming slaves to slay their masters. Furthermore, he said, sudden emancipation and racial upheaval might disrupt cotton production for six decades. Instead of preventing foreign intervention, he warned the cabinet, Lincoln’s emancipation edict would provoke the Great Powers of Europe to rescue the South.20

Seward was just beginning. He continued by pointing out to the president before the cabinet that emancipation, coming in the wake of the disastrous Peninsular Campaign in Virginia, would be viewed abroad as “the last measure of an exhausted government, a cry for help; the government stretching forth its hands to Ethiopia [the slaves], instead of Ethiopia stretching forth her hands to the government.”21

Lincoln had made it clear to members of the cabinet at the beginning of the meeting that they were not there to debate the emancipation policy; his mind was made up. Seward shrewdly, if disingenuously, professed to approve of the policy in principle, but he insisted that now was not the time. The Union must wait for a decisive military victory. Pulling out the stops, Seward urged they wait until “the eagle of victory takes his flight,” allowing the government to “hang your proclamation about his neck” in national triumph instead of desperation. Of course, Seward realized that a decisive military victory would render an emancipation decree less urgent.22

Lincoln remained determined to move forward on emancipation, and while Seward’s dire predictions of Haitian-style racial conflagration did not change his mind, the president was concerned about the timing of his policy. As to Seward’s prophecy of foreign outrage and intervention, it appears that by this time the president was more impressed with Carl Schurz’s view that the foreign public would rally in support of emancipation. Lincoln understood fully that emancipation was a diplomatic as well as military necessity.23

THE LONG WAIT FOR UNION MILITARY VICTORY THAT SUMMER OF 1862 seemed endless. At the end of July Robert E. Lee’s Confederate forces inflicted a second humiliating defeat on the Union at Bull Run. Emboldened by success, Lee decided to take the war into Maryland, humble the Union on its own soil, and surround the capital at Washington. This would demonstrate to the Great Powers of Europe that the South was capable not only of defending itself but also of capturing the very capital of the enemy. Lee ordered his troops to sing “Maryland, My Maryland,” the defiant anti-Union anthem, as they advanced north on September 4, crossing the Potomac River no more than twenty-five miles northwest of Washington. On September 17 Lee’s army joined battle with Union forces at Antietam Creek in western Maryland. It was the bloodiest single day of the entire war, indeed in all American history, and it ended in stalemate. The next day, however, Lee decided to withdraw his forces, and two days later they crossed back over the Potomac River into Virginia.24

Lincoln could make a plausible claim to victory at Antietam. With a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation in his hand, he opened the cabinet meeting on September 22 by saying he had “made a promise to myself and,” he hesitated slightly, “to my Maker” that if the rebel army was driven out of Maryland, he would free the slaves. Then he read the lengthy and rather arid proclamation to a somber cabinet. Seward made no protest this time, and the next day he countersigned the final document.

Significantly, as soon as it was signed, Lincoln instructed his secretary of state to publish the proclamation as an official State Department circular and to send it immediately to all US legations and consulates around the world. Seward’s cover letter for the circular employed cautious language. Given “a choice between the dissolution of this . . . beneficent government or a relinquishment of the protection of slavery, it is the Union, and not slavery, that must be maintained and preserved.” But Seward’s private correspondence indicates that he was still doubtful about the timing and international repercussions of the proclamation, and he was preparing to say, “I told you so.”25

ALL THAT SUMMER SEWARD HAD WATCHED EVENTS UNFOLD WITH growing apprehension. Far from softening his hard-power policy in the face of Union reverses in Virginia, Seward had issued one of his most strongly worded threats to Britain a few days after Lincoln’s July 22 cabinet meeting on emancipation. He instructed Adams to remind the British government that the Union army was growing with “new ranks of volunteers . . . daily increased by immigration.” “Neither the country nor the government has been exhausted.” In case anyone missed the point, he added: if “respect of our sovereignty by foreign powers” was violated, “this civil war will . . . become a war of continents—a war of the world.”26

Seward feared the worst, that Britain and France were about to intervene and settle the war on terms of separation. He was right. In London when news of McClellan’s reverses in Virginia first arrived in July, Lord Palmerston and Earl Russell quietly set in motion a plan for intervention. They planned to act in concert with France and Russia, perhaps Austria as well, in hopes of presenting the North with a united coalition of Great Powers that would simply overwhelm Seward and all his blustering about a “war of the world.”

According to this plan, a multilateral commission would extend its good offices to mediate a peace and on terms that would recognize the South’s separation. This mediation offer would be presented as a humanitarian intervention to bring to an end the terrible carnage of the war and to alleviate the suffering of distressed cotton mill workers across Europe. International law specified that outside parties affected by prolonged wars could, with good cause, offer to mediate peace. When one side rejected peacemaking efforts, as everyone fully expected the Union would do, intervention in favor of the willing side became more justifiable. In any case, such an offer of humanitarian intervention, some thought, would help assuage public opinion if it came to war with America.27

All during the summer of 1862, Palmerston seemed to be signaling to the United States that Britain was preparing to abandon neutrality. In June he picked an unnecessary fight with Charles Francis Adams by writing a personal letter denouncing Benjamin Butler’s “woman’s order” in New Orleans. Butler’s order was controversial, but such matters were not the usual concern of foreign governments. “Palmerston wants a quarrel!” Adams realized.28

Also in June Lord Lyons, Britain’s ambassador to the United States, left Washington for London, supposedly on personal leave to escape the oppressive heat, but some read his departure as a portentous sign. Confederate agents in Europe certainly did. John Slidell wrote to James Mason in London, “There is every reason to believe that the event you so thoroughly desire and which we talked about when I had the pleasure of seeing you in Paris is very close at hand.” “Lord Lyons returns to America on Oct 15th. Is it not possible that he may announce it?” His cryptic message, of course, was referring to the announcement of Confederate recognition by Britain and France, and it probably drew on secret information from his spy, Pierre Cintrat, inside the French foreign office.29

Another ominous sign of British bias came in July 1862, when, despite persistent protests from Union officials, the British government, either by subterfuge or by negligence, allowed a warship secretly built for the Confederate navy to launch from Liverpool in utter disregard of its own declaration of neutrality. The CSS Alabama would terrorize the Union merchant marine for the next two years; more ships were under way, according to reports.30

On July 18 MP William Lindsay, a stalwart of the “southern lobby,” stood in Parliament to move that Britain extend its good offices to mediate peace and, in effect, recognize the South’s independence. News of the Confederate victory in the Seven Days Battles had just reached London, and false reports that McClellan had surrendered the whole Union army circulated with stunning effect. Lindsay made his motion before a packed session of Parliament while members both jeered and cheered his resolution. James Mason sat nervously in the gallery, listening to the debate and chewing tobacco.

Palmerston slumped on the front bench and appeared to be snoozing while the MPs argued into the night. It was one thirty in the morning before old Pam finally rose from his seat as the members hushed. In a mildly scolding manner, he informed the MPs that discussion of this kind was fraught with great danger and that it was a matter best left to his cabinet to decide behind closed doors. Mason appeared sullen and dejected as the Parliament adjourned, but what he did not know was that Palmerston, though irritated by Lindsay’s presumption, fully intended to intervene. Had it all gone as Palmerston and Russell planned, the South would soon have its long-sought independence.31

From the US legation in London, Adams wrote Seward that he had been informed that Britain and France were quietly conspiring “to get up a congress for the disposal of our affairs.” He suspected Lord Palmerston to be the main instigator, but it was Earl Russell who actually took the more aggressive part in the turn toward intervention. Adams was already convinced that emancipation was “a positive necessity,” and he told his diary that July that the ultimate purpose of the entire conflict must be “to topple the edifice of slavery.” In late September Adams received a disturbing message from Seward, warning that recognition of the South was imminent. “The suspense is becoming more and more painful,” Adams told his diary. “I do not think since the beginning of the war I have felt so profoundly anxious for the safety of the country.”32

Like Lincoln in Washington, Lord Palmerston was waiting that September for military events to decide his course of action. On September 14 he made the first decisive move toward intervention after receiving news of Second Bull Run. He wrote almost gleefully to Russell, who was attending the queen while she was visiting her relatives in Gotha, Germany: “My Dear Russell,” the Federals “got a very complete smashing,” and it appeared “that still greater disasters await them,” including the possible surrender of Washington or Baltimore. If all this should happen, Palmerston proposed, is it not time for England and France to “recommend an arrangement upon the basis of separation?”33

Russell answered three days later with equal alacrity, as though it all had been rehearsed for some time. “Whether the Federal army is destroyed or not, it is clear that it is driven back to Washington, and has made no progress in subduing the insurgent states.” Russell readily agreed with Palmerston that “the time is come for offering mediation to the United States Government,” and he added, “with a view to the recognition of the independence of the Confederates.” Russell was not interested in simply ending the American war; he wanted to ensure the South’s independence. If the North rejected mediation, he spelled it out to Palmerston, “we ought ourselves to recognize the Southern States as an independent State.” Taking “so important a step,” he advised the prime minister, required a cabinet meeting; October 23 or 30 would suit him.34

Palmerston was virtually rubbing his hands together as he replied to Russell on September 23. “Your plan . . . seems to be excellent,” but the meeting should not be delayed. “France, we know, is quite ready and only waiting for our concurrence,” and “events may be taking place which might render it desirable that the offer be made before the middle of October.” What Palmerston had in mind, obviously, was exerting pressure on Lincoln and the Republicans before the congressional elections in early November. He also anticipated news of Union disasters in Maryland. If the Federals were defeated on their own soil, he told Russell, they would be “at once ready for mediation” before they lost more territory; “the iron should be struck while hot.”35

Palmerston proposed that they invite Russia to join with Britain and France. This would make the offer of mediation more difficult for the North to spurn, but he also worried that Russia might be “too favourable to the North” if it actually came to mediation. Russell, in turn, let Palmerston know that the queen was favorable to the whole idea, but she urged them to bring Austria in on it as well to ensure broader European support for intervention. Whoever joined their plan, Britain was taking the lead to end America’s war by separating the warring parties forever.36

News of the Emancipation Proclamation did not reach Europe until October 6 and 7, precisely as Palmerston’s cabinet was preparing to meet to discuss plans for intervention. Seward’s prediction that European governments would recoil in horror at what they would view as a call for servile insurrection and Carl Schurz’s rival prophecy that the public would rally behind a Union war for liberty were about to be put to the test.37

If Earl Russell was any indication of Europe’s reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation, Seward had been spot-on. Russell called the cabinet to its meeting with a circular dated October 13 that characterized the war as a regrettable stalemate between “military forces equally balanced, and battles equally sanguinary and undecisive.” As for Lincoln’s emancipation edict, Russell thought animosities between North and South would be “aggravated instead of being softened” by what he sarcastically referred to as the “large and benevolent scheme of freedom for four millions of the human race.” It was nothing more than an incendiary device aimed at “exciting the passions of the slave to aid the destructive progress of armies.”38

The question before them, Russell explained in his circular, was to decide if it was not Europe’s duty “to ask both parties, in the most friendly and conciliatory terms, to agree to a suspension of arms for the purpose of weighing calmly the advantages of peace against the contingent gain of further bloodshed, and the protraction of so calamitous a war.” In a private letter to William Gladstone, a key cabinet member brought into the plan, Russell spelled it out frankly: Britain, France, and possibly Russia would extend their good offices to both sides “and in the case of refusal by the North” would then propose that the South be treated “on the basis of separation and recognition.”39

IN FRANCE WILLIAM DAYTON HAD RECEIVED THE SAME INSTRUCTIONS Seward sent to Adams: brace for mediation proposals and threaten war if there is even a hint of recognizing the South. Napoleon III, having met with John Slidell in Vichy on July 16 to plot possible alliance with the Confederacy, was eager for Britain to give the signal for some form of joint intervention by the Great Powers. Three days after the Vichy meeting, Napoleon had sent a telegram to his foreign minister, Édouard Thouvenel, who was in London: “Ask the English government if they don’t think the time has come to recognize the South.”40

Napoleon III “is hovering over us, like the carrion crow over the body of the sinking traveler,” John Bigelow, US consul in Paris, wrote to Seward that summer, “waiting until we are too weak to resist his predatory instincts.” By this time France’s Mexican adventure was deeply entangled with French policy on the American question, and France needed an independent Confederacy for the Grand Design to succeed.41

Meanwhile, at the Quai d’Orsay, Thouvenel had been poring over maps of North America, trying to delineate a boundary that might allow some peaceful coexistence of what he envisioned as two “federated confederacies.” He had also come up with what he called a “possibly absurd ideas” for two republics that would govern their domestic affairs independently but act as one nation in foreign affairs and commercial policy. The United States of America would become a customs union, in other words. His office staff had been working on it since June, and Henri Mercier, the French ambassador to Washington, had proposed a similar plan to Confederate leaders in Richmond. Thouvenel thought that somehow the North and South had to learn to accept some form of peaceful coexistence.42

Thouvenel invited Dayton to meet with him on September 12 to assure him that, although there was no official change in French policy, he wanted to share his “personal views” as a friend of the United States. “I think that the undertaking of conquering the South is almost superhuman,” he told Dayton bluntly. The South is so vast, “you can not hold it down if you conquered it.” This may have seemed odd advice from an empire with occupying armies in Africa, Mexico, and Indochina, but Thouvenel’s point was that “it is not the nature of a democratic republic like yours to hold so many hostile people in subjection.”43

Dayton was only vaguely aware of Palmerston’s plans for joint intervention when he met with Thouvenel again on October 2. This time he came armed with a discourse on the natural geopolitical unity of the United States and the Union’s unswerving determination to maintain “one country” under one federal government. This was a life-or-death struggle for national existence, he explained earnestly to Thouvenel. The French minister allowed that Europeans such as he did not understand all that sustained America’s concept of national unity, but as a practical matter, he told Dayton, “I must say I no longer believe you can conquer the South.” Nor did any reasonable statesman in Europe believe the Union could succeed, he added.44

Then Thouvenel startled Dayton by nonchalantly asking, “Have you heard from Adams lately?” Dayton looked puzzled and said he had not. It appeared, Thouvenel informed the worried American, that “it will not be long before Great Britain will recognize the South.” Dayton was visibly stunned, but far from speechless. He quickly responded, and according to Seward’s script: if Britain recognized the South, Dayton warned, the United States would prepare for the “ultimate consequence.” Union naval forces, he reminded Thouvenel, were “untouched” by the war and would be “better prepared than at any past period in our history.” The Union would defend itself and its interests “to our last extremity,” Dayton assured him.45

Thouvenel understood the threat was intended for France every bit as much as for Britain. He wrote to Mercier later that day, belittling Dayton’s menacing remarks, obviously made at Seward’s direction and with his boss’s same overblown confidence. Dayton’s “worried look betrayed his blustering language,” Thouvenel wrote.

Then, as though thinking while he wrote, Thouvenel began to consider the consequences of French action and about the mighty naval force and ironclad ships the Union was building. Joint intervention would force the French to “do our share of the fighting along with England,” he wrote, and “I admit to you that I would think a long while before doing it.” Mexico, America, and Rome were “really too much all at once.”

Dayton’s warnings had more of an impact on Thouvenel than he knew, but he had found the whole conversation positively “alarming.” That day he wrote to Seward to warn that France, with British cooperation, was about to make a move toward recognition of the South.46

WHAT NO ONE IN PARIS OR LONDON FORESAW THAT SUMMER OF 1862 was that Giuseppe Garibaldi and his band of Red Shirts in Italy were about to upset the mighty plans of Europe’s Great Powers. Their actions in the remote south of Italy would create a crisis in the French government that would force Thouvenel from office and dash plans for joint intervention in the American war. Britain and France were about to receive a firm reminder of Palmerston’s famous adage: “Opinions are stronger than armies.”47

All during the summer Garibaldi had been rallying Italians to march on Rome and make it the capital of the new united Italy. French troops had been defending Pope Pius IX as pontiff of the Papal States since 1849. In Turin King Victor Emmanuel II publicly condemned Garibaldi’s call to arms out of fear it would lead to war with France. Still, he and his government did little to silence Garibaldi that summer as he staged enormous public gatherings across Italy, issued bombastic speeches and militant statements to the press, organized citizen rifle clubs, and summoned Italians to fulfill their national destiny in Rome. There were rumors that the Italian government was secretly encouraging Garibaldi to arouse popular pressure to force Napoleon III to abandon Rome. Some said Garibaldi carried a sealed metal box with a signed letter from the king, authorizing his actions.48

Reenacting his spectacular invasion of Sicily two years earlier, Garibaldi sailed to Sicily late in June, and before an immense and enthusiastic crowd at Marsala he vowed, “Rome or Death!” Roma o Morte! the crowd chanted in response. Roma o Morte! It became the new slogan of the Italian Risorgimento.49

“Death if they like,” Napoleon’s devout Catholic wife, Empress Eugénie, replied, “but Rome never!” Napoleon III was less resolute than his wife. He was undergoing one of his common spells of indecision. The inglorious defeat of French forces at Puebla the previous May had inflamed opposition to his Mexican venture among the French public. Given his mounting problems at home, he might have been willing to let the pope fend for himself against the Garibaldini but for the fury it would set off among European Catholics—to say nothing of Eugénie. More than that, a humiliating retreat in the face of Garibaldi’s red republican army would inflict incalculable damage to his prestige.50

In late August Garibaldi and his Red Shirts left Sicily, crossing the Straits of Messina to begin their march up the Italian peninsula toward Rome. The king, acting his part, dispatched units of the Italian regular army to stop them. The two armies met in southern Italy at Aspromonte (sour mountain) on August 29. When the Italian officers ordered them to surrender and lay down their arms, Garibaldi told his men only to hold their fire. In a dramatic moment that must have seemed endless, the great general, beloved by soldiers on both sides, stood in front of his men as they all cried out, Viva l’Italia!

Garibaldi expected the king’s soldiers to come over, to join the march on Rome. Some said he was still shouting Viva l’Italia as two bullets, possibly ricocheting off nearby boulders, struck him, one in his ankle and another in his thigh. He was taken beneath a tree to lie down, and soldiers from both sides gathered around him, some openly weeping over the fallen hero. They took him down the mountain on a stretcher and then imprisoned him at Varignano, an Italian fortress near Spezia. The Italian prime minister, Urbano Rattazzi, was eager to maintain order and to appease France, and many feared that Garibaldi and his officers would be prosecuted for high treason and sentenced to death.51

The tremors from Aspromonte moved with alarming force across Europe that September, precisely as British and French leaders were planning to intervene in favor of the South. In Washington Lincoln was still waiting to proclaim a war of emancipation when news of Aspromonte arrived in mid-September. The wounded Italian hero, from his prison cell in Varignano, was about to play a crucial role in rescuing the Union.

Coverage of Garibaldi’s debacle at Aspromonte was sensational. Rumors ran through the international press that Garibaldi had died, was about to be executed, or was being tormented in prison. Photographic and engraved images of the wounded hero were published widely. The press reported that thousands of admirers were sending letters, money, food, and gifts to Varignano and that hundreds of well-wishers were flocking there to visit the wounded hero or stand vigil outside the fortress walls.

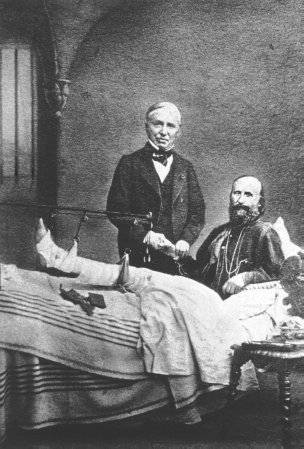

Public interest began to fixate on the wounded ankle. Blood-soaked bandages became precious relics, and when the wound failed to heal some likened it to Christ’s stigmata. An Italian cartoon portrayed Garibaldi nailed to the cross surrounded by his tormenters—duplicitous politicians and malevolent priests—while Pope Pius IX and Napoleon III danced merrily in the background. Eminent physicians from England, Russia, France, and Italy arrived at Garibaldi’s bedside to inspect the wound. The distinguished French surgeon Auguste Nélaton became a hero in his own right after discovering that the bullet was still inside the ankle and providing his special probes for its extraction to save the foot from amputation.52

32. Giuseppe Garibaldi with Dr. Nélaton, the renowned French surgeon who saved Garibaldi’s wounded foot. (COURTESY OF US NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE, HISTORY OF MEDICINE DIVISION)

For George Marsh, the US minister in Turin, Garibaldi suddenly presented another ticklish diplomatic predicament. Rumors swirled through the Italian court that an American ship had conveyed men and munitions to the insurgents in Sicily, and the US consul to Ancona, one Mr. Mighari, was implicated. Marsh warned Seward of the “extreme jealousy” of the Italian government toward any “manifestations of sympathy” with what officials in Turin were characterizing as a red republican rebellion. No one knew what direction the growing uproar over the events at Aspromonte might take. Marsh moved with extreme discretion, communicating with Italian government officials through a trusted intermediary to negotiate amnesty for Garibaldi and his men and offer asylum in America. This, Marsh proposed, might provide the Italian government with a “convenient way of disposing of them,” and they “would be willingly received” in the Union military.53

The invitation to Garibaldi of the previous year to lead a Union army was about to be renewed, and with equal sensation in the international press. Bowing to enormous public pressure, the Italian government finally granted amnesty to Garibaldi and his men in early October. Garibaldi immediately wrote to Marsh: “I am ill and shall remain so for some months; but I think continually of the disastrous war in America, my second country, to which I would gladly be of some use when recovered. I will go thither with my friends; and we will make an appeal to all the democrats of Europe to join us in fighting this holy battle.”54

THE EUROPEAN UPROAR OVER GARIBALDI MIGHT HAVE REMAINED nothing more than a distraction from the American question, had it not been for an obscure American consul in Vienna named Heinrich Theodore Canisius. Borrowing from the memorable example of James Quiggle, the US consul in Antwerp who initiated the first invitation to Garibaldi one year earlier, Canisius took it upon himself to write to the heroic prisoner of Varignano.

Canisius was a German Forty-Eighter, a young doctor who had fled to America after the Revolution of 1848 failed. He published a German-language newspaper known as the Freie Presse in Alton, Illinois, and during the 1860 election struck a deal with Abraham Lincoln, who bankrolled the newspaper to help garner German votes. The newspaper later failed, and Lincoln felt he owed Dr. Canisius a favor. Though Canisius had no diplomatic experience, as Lincoln rationalized it to Seward, the Vienna consulship seemed to be a just reward: “The place is but $1,000, and not much sought, and I must relieve myself of the Dr.” Now, a year later, from his humble post in Vienna, Canisius, with a wife and children, was hard up and complaining to Seward about his low salary and high rent. It may have been hope for pecuniary gain as much as ideological zeal that motivated Canisius to write to Garibaldi. Consul Canisius, in any case, was about to astonish the world and help upend the secret plans of the Great Powers of Europe to end America’s Civil War and recognize the Confederate South.55

“General!” the Vienna consul wrote to the imprisoned Garibaldi on September 1, three days after the incident at Aspromonte. “As you have failed for the present to accomplish the great and patriotic work you lately undertook in the interest of your beloved father land, I take the liberty to address myself to you, to ascertain whether it would not be against your present plans to lend us a helping hand in our present struggle to preserve the liberty and unity of our great Republic. The battle we fight is one which not only interest ourselves, but also the whole civilized world.”56

Garibaldi may not have known how to reply to this bold communication from an obscure, low-level consul in Vienna. He finally replied on September 14: “I am a prisoner and I am dangerously wounded.” He told Canisius that he hoped to “be able to satisfy my desire to serve the Great American Republic, of which I am a citizen, and which today fights for universal liberty [la libertà universale].” Garibaldi had apparently made up his mind that his second country was fighting for emancipation, whatever Lincoln decided to do.57

Once Canisius received Garibaldi’s reply, on September 18 he wrote to Seward, saying he had “hastened” to inform his superior about his self-appointed diplomatic mission. With only a terse cover letter that simply stated what he had done, Canisius sent copies of all his correspondence with Garibaldi. Seward received the letters in early October, about the same time that he was reading them in the New York Times, and he must have been furious. Canisius had gone public with his rogue diplomatic mission and given copies of the correspondence to the Wanderer, a Vienna newspaper. By late September the story had spread like wildfire through the international press.58

Seward was in a bind. He could not risk offending Italy and France by allowing a US consul to publicly praise a jailed rebel leader. He had little choice but to disown Canisius’s overtures as unauthorized and to circulate news to all his ministers in Europe that Canisius had been sacked. His icy letter of dismissal, dated October 10, pointed out to Canisius that not only had he egregiously exceeded his authority, but he had also violated the very principle on which the Union was waging war: he was praising a rebel for his “great and patriotic work” against his own government.59

Canisius was out of line, but his bold personal diplomacy project was paying rich dividends by linking Garibaldi, whose popularity was soaring among liberal Europeans, to the Union cause. Public demonstrations in support of Garibaldi and against Napoleon III, the pope, and the Italian government broke out across Italy and then spread through Europe. “The whole peninsula is shaking as if a volcano were about to blaze forth,” Caroline Marsh, wife of the US minister in Turin, confided to her diary, “and the death of Garibaldi from his wounds, or any severity towards him on the part of the government would be very likely to scatter the throne of Victor Emmanuel to the four winds of heaven.”60

In France dissent smoldered, stringently censored by Napoleon’s regime, but in England violent riots broke out in London’s Hyde Park, Birkenhead, and elsewhere. On Sunday, September 28, a group of about fifty working-class Radicals going by the name Workingmen’s Garibaldian Committee gathered at a large earthen mound in Hyde Park to speak in support of Garibaldi and the cause of republicanism. About one thousand people gathered around them, and as the oratory got under way, a gang of a hundred or more Irish Catholics—men, women, and children—rushed the mound, wielding bludgeons and shouting, “Long Live the Pope!” A brawl ensued for thirty minutes before the crowd dispersed, but the battle would be resumed the next Sunday.61

From prison Garibaldi and his coterie of advisers dexterously managed the press. In a public letter entitled “To the English Nation,” dated September 28 and published in British newspapers on October 3, he hailed England as the refuge from autocracy and tyranny and called upon the English to lead the world toward a new era of peace and liberty. He urged the English to rebuke Napoleon III and his imperialist designs. “Call the French nation to cooperate with you.” “Tell her that conquests are today an aberration, the emanation of insane minds.”

Then he embraced the Union cause unequivocally: “Call the great American Republic. She is, after all, your daughter, risen from your bosom,” and “is struggling today for the abolition of slavery so generously proclaimed by you.” Garibaldi’s letter appeared in British newspapers on October 3, three days before news of Lincoln’s emancipation decree reached London. Garibaldi was proclaiming emancipation before Lincoln. “Aid her to come out from the terrible struggle in which she is involved by the traffickers in human flesh,” he implored the English nation. “Help her, and then make her sit by your side in the great assembly of nations, the final work of the human reason.”62

Garibaldi’s letter “To the English Nation” arrived as Garibaldi meetings, some quite raucous, were taking place throughout Britain. In London Radical workers planned a second large Garibaldi demonstration in Hyde Park on Sunday, October 5. Crowds estimated at eighty to one hundred thousand gathered in the park, and many thronged around the speaker’s mound, which the Garibaldians dubbed the “Hyde Park Aspromonte.” Again the Garibaldians on the mound were assailed by “Irish roughs” armed with bludgeons, and a full-pitched battle ensued, leaving dozens of busted heads and several stilleto wounds from Italians who “made free use of the knife.” “It was not a mere squabble,” according to the alarming report in the London Times. “It was a battle, lacking only the smoke and the lines and squares.” The New York Times had a field day mocking the Hyde Park melee. “Had it occurred in Central Park instead of Hyde Park,” it would have “been cited as a melancholy proof of the decadence of public morals incident to Republican institutions, and as a new motive to intervene ‘in the interest of humanity and civilization.’”63

Charles Francis Adams hastened to inform Seward after the first Garibaldi demonstration, “A serious riot took place in Hyde Park on Sunday last, where a meeting in favor of Garibaldi was attempted.” “All this contributes to divide the attention heretofore so much concentrated on America,” and a good thing too, he might have added. “Less and less appears to be thought of mediation or intervention,” he wrote, and “all efforts to stir up popular discontent” against the Union and in favor of ending the war “meet with little response.” For the first time Adams was profoundly struck by the depth of popular support for the Union. “I am inclined to believe that perhaps a majority of the poorer classes rather sympathize with us in our struggle,” he told Seward, “and it is only the aristocracy and, the commercial body that are adverse.”64

The bonds between Garibaldi and the Union, the pope and the Confederacy, were reinforced as news flashes from Italy intersected with those emanating from Washington in early October. Garibaldi’s full-throated endorsement of the Union cause roused popular support just as news of the Emancipation Proclamation broke in Europe. The shots fired at Aspromonte shook the foundations of power in Italy, France, and Britain. In Italy genuine fears of popular unrest forced King Victor Emmanuel to free Garibaldi and his men and summarily dismiss Prime Minister Rattazzi, who was blamed for the Aspromonte fiasco.

In Paris Garibaldi had become the hero of the hour. “Garibaldi has been vanquished,” Malakoff told New York Times readers, but his name has grown grander and more monumental than ever!” “Daily bulletins of his health are published and sent over the world by telegraph, as if he were, as he really is, the only universal monarch.” Garibaldi “represents a principle,” and people were afraid that the principle, as well as the man, was wounded. Dr. Nélaton, the surgeon credited with saving Garibaldi’s foot, met a boisterous lecture hall full of students clamoring for a full account of their professor’s encounter with their hero. “Half the Police of the town could not prevent a demonstration,” had Nélaton given them the least encouragement, Malakoff mused.65

Henry Sanford, writing from Paris in early October, was heartened by the surge of support coming from France’s liberal public, “whose will is respected because its revolutions are feared.” There were rumors that Garibaldi might raise the republican banner in Italy and that this would set off similar movements in Paris. France’s history showed “what one day’s excitement may do in the atmosphere of this inflammable and inconstant city,” Malakoff noted. Coincidentally, rumors of a plot by Italian revolutionaries to assassinate Napoleon III led to widespread arrests in Paris that October. The Garibaldi imbroglio also caused a crisis in Napoleon III’s cabinet. In order to appease Catholics and Empress Eugénie, he replaced Thouvenel with Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys, a veteran of the Quai d’Orsay and a conservative Catholic who believed fervently in the absolute power of the pope as pontiff of Rome. For now, France would continue to stand by the pope.66

CONFEDERATE HOPES, MEANWHILE, PLUMMETED AFTER ASPROMONTE. From Paris Edwin De Leon wrote to Benjamin, despairing that “the tide which was setting in so strongly toward our recognition . . . was turned by the frantic folly of Garibaldi in Italy.” Slidell also lamented that Napoleon III “could do nothing until Garibaldi is disposed of” and that with the change of foreign ministers in France, it was clear “for the time our question has been lost sight of.” Though Drouyn du Lhuys was far more conservative than Thouvenel on the Roman question, he proved even more determined than his predecessor to keep France neutral on the American question. He was dubious about the Mexican venture and not about to expose France to the risk of another war across the Atlantic.67

In October 1862 Judah P. Benjamin was dismayed to learn that the French were making overtures to Governor Francis Lubbock of Texas by way of encouraging his state to break away from the Confederacy. It appeared that the French wanted a buffer to protect them from their Confederate buffer. The French backed away from Texas, but it reminded Benjamin and Slidell that the French could as easily become rivals as allies and that there were many levels to this game of secession and international intrigue.68

In London Palmerston and Russell were also backing away from intervention. Charles Francis Adams met with Russell in early September after news of Aspromonte arrived, and, in a rare moment of levity, Russell made a joke that Adams must feel relieved to learn that Garibaldi and his band had thwarted “any idea of joint action of the European powers in our affairs.” Adams returned the favor by saying, “I was in hopes that they all had quite too much to occupy their minds” without looking for trouble on the other side of the Atlantic.69

Palmerston’s plans for multilateral intervention had foundered. The Garibaldi crisis distracted the French government, and Russia, nursing its lingering enmity toward France and Britain following the Crimean War, kept aloof. Czar Alexander II regarded the Americans as Russia’s friends, and some said that Lincoln’s election inspired him to change his country’s despotic image and emancipate Russia’s serfs. He had no intention of moving backward by recognizing a nation whose cornerstone was slavery.70

The commotion in Paris, the eerie silence from St. Petersburg, the news of Confederate retreat from Maryland, and the Garibaldi riots in England left Palmerston with the terrifying thought that Britain might face an American army and navy more powerful than ever—alone and with doubtful popular support. By late September Adams wrote Seward with great relief that, for the moment at least, the Garibaldi affair seemed to have eclipsed interest in American intervention.71

But Adams spoke too soon. The British lion was about to roar through the ungoverned throat of Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone, eager aspirant to power as Palmerston’s successor. During a speaking tour that brought him to Newcastle in northern England, Gladstone decided to test public reactions to the idea of intervention in the American war. Early in the speech Gladstone bemoaned the misery America’s war had visited on England’s workers and then predicted that “the success of the Southern States” was inevitable. “Hear, hear!” the crowd cheered.

It was October 7, and news of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had already broken in the British press. Gladstone knew this, but he chose to cast doubt upon the sincerity of Lincoln’s proclamation, and proposed that an independent South would free its slaves more swiftly and with more benign effect than a decree issued by the North. Just as Seward might have predicted, Gladstone went on to say that Lincoln’s emancipation edict would bring unimaginable racial strife to the South.

The time might come, Gladstone said, when it would become the “duty of Europe” to offer its “friendly aid in composing the quarrel.” “We know quite well that the people of the Northern States have not yet drunk of the cup—they are still trying to hold it far from their lips—the cup which all the rest of the world see they nevertheless must drink of.” Then Gladstone offered the lines that quickly reverberated around the world: “We may have our own opinions about slavery; we may be for or against the South; but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis and other leaders of the South have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more than either—they have made a nation.”72

The press, unaware that Palmerston was losing interest in intervention, took Gladstone’s speech as a signal that Britain was about to move toward recognition of the South. London financial markets experienced violent turbulence at the prospect of war. New York Times correspondent Monadnock also thought it was Palmerston’s scheme: “The whole game is prepared, and the first move was the speech of Mr. Gladstone at Newcastle. It is the beginning of the end.” Charles Adams, who a few days earlier had thought Garibaldi had derailed the intervention threat, told his diary on October 9, “We are now passing through the very crisis of our fate.”73

Some thought Gladstone was trying to force the decision on Palmerston and the cabinet by demonstrating public support for intervention. He may also have been trying to bring glory to his own career as sponsor of a humanitarian solution to America’s “terrible war.” If so, the plan backfired very badly. Palmerston resented his younger rival’s overreaching and quickly distanced himself from the speech. If he still harbored any thoughts about the wisdom of intervention, the press reaction gave no encouragement. Even pro-South organs such as the London Times and Saturday Review, condemned Gladstone for putting British neutrality at risk. Friends of the Union lambasted him for hailing a nation “made” to preserve slavery and took pains to point out that it was not Jefferson Davis “making” the Confederate navy so much as the British, who had recently allowed the Alabama to be built and launched in violation of its own professed neutrality.74

Gladstone’s Newcastle speech was another supreme example of a politician’s gaffe: stating honestly what he was not supposed to say in public. Gladstone’s defenders insisted that he had been misunderstood and that he had no intention of speaking for the government. Little of this was true. Gladstone’s own diary entries made it clear that his Newcastle remarks, far from being a “hasty impromptu utterance,” had been “long and well considered” and expressed exactly what Palmerston, Russell, and Gladstone himself had been scheming out of public view. If the speech was a trial balloon to test public opinion, the air went out of it very rapidly. The British people did not want to wage war in support of slavery.75

Inside Palmerston’s cabinet there was also rising opposition to taking sides with the South. On October 14 George Cornewall Lewis, the secretary of war, made a public speech against intervention and three days later circulated a lengthy, forcefully argued position paper against intervention in the American war. Palmerston was distressed by the negative reaction to Gladstone’s Newcastle peroration, and he realized that, despite all the denunciations of the emancipation decree in the press, Lincoln had now declared war against slavery, and any policy favoring an independent South would be seen as an effort to rescue slavery from its doom.76

Looming over all of these concerns was John Bright and the Radicals’ call for the democratization of Britain. The Garibaldi riots in Hyde Park and Birkenhead, similar demonstrations in Italy and elsewhere, and the rumors of revolutionary unrest on the Continent must have been much on Palmerston’s mind when he wrote to Russell at the end of October, complaining of the “Scum of the Community” rising to the surface. But Palmerston was also chastened by recent events and gave clear signs of appeasement. Lady Palmerston made a public show of sending a special bed to Garibaldi and she made entreaties to Charles Francis Adams and his wife to attend parties at the Palmerston home again. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Palmerston was quietly retreating from anything that looked like intervention on behalf of the slave South.77

Inside the British and French governments, quiet discussions of the American question continued into the fall and winter of 1862–1863. France’s new foreign minister, Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys, assumed the lead in efforts to bring an end to the American war, first with another attempt at joint intervention and then with a unilateral offer of mediation. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had done nothing to discourage the Great Powers from privately wishing to bring the war to an end or from hoping for the ultimate success of the South. But with public opinion apparently turning against intervention, none had the spine to try using a rejected offer of mediation as an excuse to recognize the South.78

In January 1863 an uprising in Poland against Russian rule suddenly brought new strains to relations among the Great Powers, which further discouraged meddling in American affairs. Most European government leaders still expected the Union to exhaust itself, financially if not militarily, and they began placing their hopes for an end to war on the rise of the antiwar movement in the northern United States. In 1864 Democrats, deeply divided over the war and emancipation, nominated General George McClellan to challenge Abraham Lincoln for the presidency, taking as their motto “The Union as it was.” The Peace Democrats within the party wanted to nullify the Emancipation Proclamation, end the war, and restore the Union with slaveholders. Though McClellan did not agree with them on all points, the election of November 1864 became a plebiscite on war or peace, Union or secession, freedom or slavery.

MEANWHILE, THEODORE CANISIUS WAS STRANDED IN VIENNA WITH a wife and young children and, at thirty-six years old, without a job or funds to get home. Far from remorseful over his diplomatic venture, Canisius felt fully vindicated by all the “commotion” he had caused and was indignant at being fired. He wrote an unapologetic defense of his actions to Seward, making the point that hundreds of military officers from all nations had enlisted in the Union army, and Garibaldi, not least among them, had been officially invited by Seward the year before.

More than seeking Garibaldi’s military aid, Canisius explained, he was enlisting his moral support. “I thought the time had come to let the world know what the great Hero of the Castle of Varignano thinks of us and our cause.” Referring to the “great Garibaldi demonstrations in England” and Garibaldi’s letter “To the English Nation,” Canisius argued that his endorsement had greatly “strengthened our cause throughout Europe.” “I was anxious to affect this at the time when almost everybody seemed to turn against us.”

Canisius had a point, and Seward had to realize the great service his impulsive consul in Vienna had performed. The Italian government, eager to calm the waters, encouraged Seward to forgive Canisius’s breach of diplomatic protocol. No doubt Lincoln, who followed the Garibaldi affair with great interest, agreed, and Seward reinstated Dr. Canisius in December 1862.79

Just as Canisius predicted, in Turin that autumn Marsh was besieged by volunteers, many of them veterans of Aspromonte, wishing to fight for the Union. One public letter from a Garibaldian colonel volunteered “four to six thousand men, commanded by two hundred good officers, and all of them veterans.” A New York Times editorial welcomed “Garibaldi’s Braves” to join Liberty’s war in America. “Dynastic and aristocratic Europe has chosen to bestow its sympathies upon the South” and make it a “war in favor of a privileged class; a war upon the working classes; a war against popular majorities; a war to establish in the New World the very principles which underlie every throne of Europe.” What they despised, the Times said, was “the spectacle of successful democratic institutions, which this country, until two years ago, happily presented,” and they supported the Southern oligarchy “to prove, if possible, the democratic experiment a failure.”80

In late October 1862 Marsh wrote to Garibaldi, still expressing hope that America would “have the aid both of your strong arm and of your immense moral power in the maintenance of our most righteous cause.” But the wounded hero would return to his home on Caprera to convalesce, and would never again walk without aid of crutches or cane.81

It would be another year before America heard from Garibaldi again. In August 1863 he sent a public letter on behalf of the Italian liberals congratulating Lincoln as the world’s “pilot of liberty.” Comparing him to no less than Jesus Christ and John Brown, the letter hailed Lincoln as the great emancipator. “An entire race of men, bowed by selfish egotism under the yoke of Slavery, is, at the price of the noblest blood of America, restored by you to the dignity of man, to civilization and to love.” While America “astonishes the world by her gigantic daring,” old Europe “finds neither mind nor heart to equal her’s.”82

America would no longer have need of Garibaldi’s “strong arm,” as George Marsh put it, but in that perilous autumn of 1862, his “immense moral power” had played a crucial role in the war now being fought for Union and Liberty.