The newspapers and the men that opposed the cause of the great Republic, are those like the ass of the fable that dared kick the lion believing him fallen; but today as they see it rise in all its majesty, they change their language. The American question is about life for the liberty of the world.

—GIUSEPPE GARIBALDI, MARCH 27, 1865

THE SPIRIT OF BIGELOW’S FOURTH OF JULY CELEBRATION THAT fabulous night in Paris glowed across much of the Atlantic world in the coming years. The trial of democracy, it seemed, had returned a very different verdict from the one conservatives had relished four years earlier. “Under a strain such as no aristocracy, no monarchy, no empire could have supported,” one English Radical noted, “Republican institutions have stood firm. It is we, now, who call upon the privileged classes to mark the result.” The Union’s triumph, which had been so long doubted by its detractors, sent an exhilarating thrill of vindication through reformers on both sides of the Atlantic. For the moment at least, there was something of a republican Risorgimento, a season of resurgent hope for popular government and universal emancipation.1

From London Giuseppe Mazzini, the champion of Italy’s Risorgimento, summoned America to carry on as the leader of what he proposed as the “Universal Republican Alliance.” It would form a “moral Atlantic Cable,” uniting republicans on both sides of the Atlantic. “You must,” he told Americans, “be a guiding and instigating force, for the good of your own country and that of Humanity.” Mazzini had in mind more than moral force; he called on America to lead the republican international brigades in an invasion of Mexico to overthrow this “outpost of Caesarism.”2

Americans were weary of war and did not answer Mazzini’s call to arms, but his dream of an international republican resurgence was about to be realized in other ways and on many fronts. In the American hemisphere the hostile constellation of slavery, monarchy, and empire that had ringed the United States in 1860 was defeated or in retreat by the end of the decade. The Confederate rebellion had been vanquished, and Reconstruction would proceed on the basis of free labor and the enfranchisement of former slaves. By 1867 it appeared that the Republican Party was determined to defend the hard-earned freedom of black citizens with an ongoing military occupation of the defeated South.

In the Caribbean Spanish dreams of imperial revival died hard in the jungles of Santo Domingo during the spring and summer of 1865. The Santo Domingo republicans, many of them former slaves, had bled the Spanish invaders during four grueling years of guerrilla warfare. Spain’s prime minister denounced the proposal to withdraw as a “humiliating declaration of impotence.” But in April 1865, facing a severely strained treasury, growing signs of unrest in Cuba, and the threat of US naval power in the Caribbean, Queen Isabella II finally called an end to Spain’s experiment in recolonization. Thousands of Dominican collaborators scrambled to board Spanish ships as they departed for Cuba that summer.3

Spain was also forced to withdraw from reckless imperialist ventures in Peru and Chile that had begun with the military seizure of Peru’s guano-rich Chincha Islands in 1864. This eventually led to the blockade and bombardment of Valparaiso, Chile, and Callao, Peru, supposedly in answer to insults to the Spanish flag. By the end of 1866 Spain welcomed the good offices of the United States to help mediate its retreat from the South American morass it had entered.4

In Madrid General Juan Prim, former commander of Spain’s Mexican expedition and leader of the Progressista party, denounced the imperialist government for making Spain “the laughing stock among foreign nations” and in June 1866 led a military revolt. Prim was forced into exile when the rebellion failed and rumors circulated that he was meeting with John Bigelow to arrange for US support of a republican revolution in Spain in exchange for the sale of Cuba. In September 1868 Prim and others led Spain’s Glorious Revolution, which overthrew Queen Isabella II and forced her into exile in France. “The Bourbons are abolished,” the New York Times cheered; finally, Spain stood before the world as “a State without a King and a Government existing by popular will.”5

Simultaneously, a republican independence movement erupted against Spanish rule in Cuba. During America’s Civil War, slaves in Cuba’s sugar fields could be heard chanting, Avanza, Lincoln, Avanza, tu eres nuestra esperanza (Onward, Lincoln, Onward, you are our hope). Since the 1810s Cuban slaveholders had been loyal to the Spanish crown out of fear that a revolution for independence would unleash a Haitian-style uprising among their slaves. All that changed one morning in October 1868 when Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, a wealthy Cuban sugar planter and liberal intellectual, told his astonished slaves they were free and then invited them to take up arms for Cuba’s freedom. This was the beginning of Cuba’s Ten Years’ War, which failed to emancipate Cuba but succeeded in putting slavery on the road to extinction, first with a “free womb” law in 1870 that granted freedom to children of slave mothers; complete abolition followed in 1886.6

In January 1864 Brazil’s emperor, Dom Pedro II, wrote to one of his senators that “the successes of the American Union force us to think about the future of slavery in Brazil.” So long as the United States sustained slavery, “we were shielded,” as one Brazilian senator put it. By 1871 there was no need for a war to end slavery, another politician poignantly explained. “The world laughing at us was enough; becoming the scorn of all nations . . . was enough.” In 1871 Brazil passed the Rio Branco law, which freed all children born to slave women, but it was not until 1888 that Dom Pedro’s daughter Princess Isabel signed the Golden Law that abolished slavery completely. The next year the last American monarchy was overthrown, and Brazil embarked on its own republican experiment.7

Union victory had already doomed the monarchical experiment in Mexico. In April 1865 Emperor Maximilian took the occasion of Lincoln’s assassination to send a conciliatory letter of sympathy and friendship to the new president, Andrew Johnson. It went unanswered. So did his second letter, and his third. In June 1865 Maximilian sent an envoy to Washington, but Johnson refused to receive any representative of the illegitimate usurpers of power in Mexico.8

With the threat of a Franco-Confederate alliance gone, William Seward, who stayed on as Johnson’s secretary of state, thought time was his best ally in Mexico. He gave no satisfaction to those calling on the United States to invade Mexico and help overthrow Maximilian.9

Matías Romero, the Republic of Mexico’s young ambassador to Washington, impatient with Seward’s inaction, went around him by enlisting support from Union commander Ulysses S. Grant, who had long sympathized with Mexico’s plight. In June 1865 Grant sent a lengthy memorandum to President Johnson, warning him that “a monarchical government on this continent” sustained “by foreign bayonets” constituted an act of hostility against the United States. The spirit of the Monroe Doctrine as defender of American republicanism lived again. Grant was alarmed by news that diehard Confederates were bringing slaves and arms to “New Virginia,” a colony in the Mexican state of Sonora. Maximilian had issued a decree allowing what amounted to slave labor in the Sonora mines. The beleaguered emperor wanted the Confederate exiles to form a bulwark against US invasion. Grant suspected worse, and he warned Johnson that Confederate “rebels in arms . . . protected by French bayonets” were preparing to take control of northern Mexico. If Maximilian’s regime was allowed to endure, he prophesied, America would “see nothing before us but a long, expensive, and bloody war,” with enemies of America “joined by tens of thousands of disciplined soldiers” from the South embittered by four years of failed war.10

Grant ordered General Philip Sheridan to take command of some fifty thousand Union soldiers on the Texas-Mexican border to thwart the plans of Confederate diehards rumored to be mounting a last stand from northern Mexico. Grant told Sheridan, “The French invasion of Mexico was so closely related to the rebellion as to be essentially part of it.” Both men were committed republicans, and they shared a quiet understanding that US forces were also there to intimidate the French, possibly precipitate war with them, and aid Benito Juárez’s beleaguered republican army. Carefully avoiding blatant acts of aggression, Sheridan’s troops left large stores of arms and munitions on the banks of the Rio Grande, which mysteriously disappeared before daybreak. “Grant may yet be the La Fayette of Mexico, the Garibaldi of this continent,” a speaker at one of Romero’s New York banquets proclaimed. “Let the torches of civil war in the United States and Mexico be extinguished in the blood of the minions of Napoleon.”11

Across Mexico Sarah Yorke Stevenson, a young American living in Mexico City, recalled that a new spirit of resistance “vibrated throughout the land” in the summer of 1865. Panic spread among conservatives, who feared the United States was about to come to Juárez’s rescue. Emperor Napoleon III was reviewing his troops in Algeria when news of the Union’s final victory reached him. With close to forty thousand troops committed to Mexico, another twenty thousand guarding the pope in Rome, and some eighty thousand in Algeria, the French Second Empire was stretched thin. Meanwhile, a powerful united Germany, forged in “blood and iron” by Prussia’s Otto von Bismarck, loomed menacingly across the Rhine River.12

Maximilian had no intention of abandoning Mexico. On the contrary, he took extraordinary steps to establish an enduring dynasty. After eight years of marriage Maximilian and Charlotte had no children, and unflattering rumors of venereal disease or other “difficulties” circulated freely. Maximilian seized upon a bizarre solution that would “Mexicanize” his Hapsburg line; he would adopt the infant grandson of Mexico’s first emperor, Agustín de Iturbide, whose career had ended in 1824 before a Mexican firing squad.13

One of Iturbide’s sons had married an American woman, Alice Green, from Washington, DC. Their son, Augustín, named in honor of his grandfather, was born in Mexico City one year before Maximilian and Charlotte arrived. It must have occurred to Maximilian that a prince with dual citizenship might be a diplomatic asset if he wanted peace with the United States. In September 1865 Maximilian offered to adopt young Augustín and confer upon him the title of prince. The parents were to receive a handsome pension, but by agreement they would leave Mexico and return only with Maximilian’s permission.

On her way to Veracruz a few days later, Alice Iturbide was tormented by a mother’s change of heart. She returned to the capital and sent a heartrending message to Maximilian, imploring him to allow her to reclaim her child. The emperor sent a carriage to pick her up, but instead of being delivered to the royal palace at Chapultepec, the distraught mother was taken to Veracruz, deported, and banned from ever returning to Mexico.14

Prince Iturbide did Maximilian little good. Mexican conservatives were outraged that he had chosen the infant grandson of a deposed tyrant over one of their own aristocratic families. Many were already furious over Maximilian’s refusal to repeal the liberal laws that confiscated church lands and secularized public education. Maximilian still wanted to be an enlightened monarch; he even tried to bring Juárez into his government as prime minister. Mexico’s conservatives wanted a strongman who would crush the godless republicans, not make peace with them.

With US forces on the Mexican border and Juárez’s army scoring victories in the north, Maximilian sought to solidify conservative support by issuing the Black Decree in October 1865. The “time for indulgence has passed,” the decree announced; the “national will” had ratified the monarchy, and “henceforth the struggle must be between the honorable men of the nation and bands of brigands and evil-doers” who would be summarily executed when apprehended.15

Meanwhile, Seward had instructed his minister in Paris, John Bigelow, to meet with the French foreign minister, Drouyn de Lhuys, in April 1865. Bigelow gave assurances that the United States preferred not “to meddle with the experiment which Europe was now making in Mexico.” He pointedly used the word experiment at least eight times and added that his government thought it was in “the interest of all the world that this should be an experimentum cruces,” meaning decisive and final proof.16

In January 1866 Napoleon III stood before the Corps législatif to announce that its “civilizing” mission in Mexico had been completed. French troops would begin withdrawing in stages later in the year. He wrote to Maximilian to explain that Mexico was now sufficiently strong to stand on its own without French aid. No one believed that, least of all Maximilian.17

Maximilian was tempted to return to Miramar Castle near Trieste and live out his days in peace, but his more resolute wife, Empress Charlotte, would have none of it. In July 1866 she embarked on a vain mission to seek aid from the Catholic thrones of Europe. Mexican republicans satirized Maximilian’s plight in a popular song that featured the emperor standing at the shore sadly watching as his empress departed: Adiós, Mamá Carlota, Adiós mi tierno amor, Se fueran los frances, Se va el emperador (Good-bye, Mama Carlota, Good-bye my tender love, The French have left, The emperor will go, too).18

Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie received Charlotte in Paris, but only to encourage her to persuade her husband to return to Europe. She then went to the Vatican and begged Pope Pius IX to stand by the mission to restore Catholic authority to Mexico. The pope gave her no comfort, either. She began rambling incoherently about a scheme of Napoleon III to poison her and then started pleading for asylum at the Vatican. She had been slowly going mad for some time, everyone seemed to conclude in retrospect, but she was not deluded about those who had betrayed her and Maximilian.19

The last of the French forces marched out of Mexico City in early February 1867. Mexicans lined the streets, watching in eerie silence. General François Achille Bazaine, the French commander, invited Maximilian to return with him to Europe, but by this time the emperor of Mexico had decided to accept his fate and stay on in Mexico. With a small band of soldiers he left the capital and prepared to make a last stand near Querétaro, where in May 1867 the republican army took him prisoner, tried him on charges of treason, and sentenced him to death. Garibaldi and Victor Hugo were among the many prominent liberals who pleaded for clemency as a gesture of republican humanity. But Juárez risked rebellion within his own ranks if he dared pardon the author of the Black Decree.20

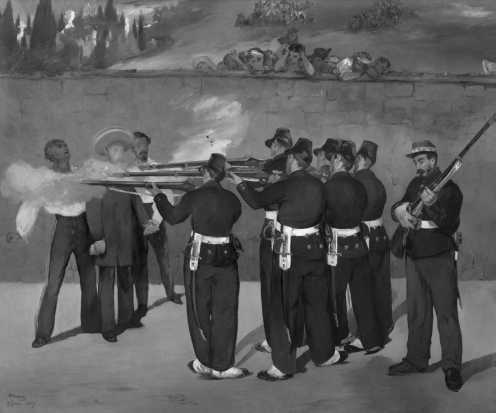

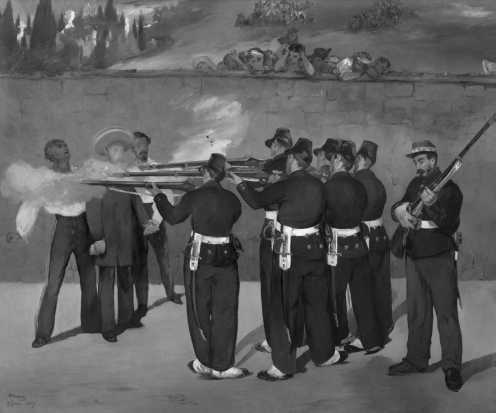

Early on the morning of June 19, 1867, Maximilian was brought before a firing squad outside Querétaro. Thousands of Mexican soldiers looked on as he made a short speech in Spanish that might serve as an epitaph for the entire Grand Design: “Mexicans! Men of my class and race are created by God to be the happiness of nations or their martyrs.” “Long live Mexico!” All six bullets struck their mark.21

News of Maximilian’s execution sent a “painful thrill” throughout the Euro-American world. It arrived in Paris on the day Napoleon III awarded prizes at the Paris International Exposition, which was intended to showcase the city Baron Haussmann had revamped to the glory of the Second Empire. Napoleon said not a word about Mexico that day, and reports of Maximilian’s execution were withheld from the press for some time. Monarchs across Europe denounced Juárez and the Mexican liberals for their “savagery” and even spoke of sending troops to avenge Maximilian’s death. But the shots from Querétaro sent a mournful echo through the courts of Europe, and calls for retaliation soon fell silent. Charlotte never fully regained her sanity, and she lived out her days at Miramar and later in Belgium, where she died in 1927. Shortly before his capture, Maximilian, sensing the end, had arranged for Prince Augustín to be returned to his mother, who came to America with the last prince of Mexico.22

38. The Execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, June 19, 1867, by Édouard Manet. (STAEDTISCHE KUNSTHALLE MUSEUM, PHOTO CREDIT ERICH LESSING, ART RESOURCE, NY)

JEFFERSON DAVIS HAD LANGUISHED IN PRISON FOR TWO YEARS AS Union officials weighed the potential consequences of punishment and martyrdom and debated his fate. He was released in May 1867 at the same time as the curtains were closing on Maximilian in Querétaro. During Davis’s time in prison Pope Pius IX sent a token of his esteem, an inscribed photograph of His Holiness that Davis displayed on the wall of his cell. This gesture of respect from one victim of international liberalism to another stood in striking contrast to the pope’s notable silence upon the death of Abraham Lincoln.23

Theories of Catholic involvement in the Lincoln assassination circulated in the United States and abroad, fueled by unfounded rumors that John Wilkes Booth was a fervent convert and knowledge that Mary Surratt, whose boardinghouse in Washington served as a meeting place for the conspiracy, was devout and was attended at the gallows by Catholic priests. Her son John Surratt, also implicated in the conspiracy, absconded to Montreal, where he was given asylum by a Catholic priest. He later fled to Rome and enlisted in the pope’s Pontifical Zouave army. Rufus King, the US minister to Rome, learned of Surratt’s presence and demanded his arrest. Surratt was detained, but mysteriously escaped from prison and was only later apprehended and brought back to stand trial in the United States. Unlike his fellow conspirators, Surratt was tried in civil court and set free by a jury of his peers in heavily Catholic Maryland.24

Catholic conspiracy theories were sensationalized in a book by Charles Chiniquy, a defrocked Catholic priest who had known Lincoln in Illinois and claimed to have shared intimate discussions with him about the “the sinister influence of the Jesuits” in fomenting the entire war. Chiniquy described Booth as a “tool of the Jesuits” and charged that Pope Pius IX’s support of Jefferson Davis and France’s Grand Design for a Catholic monarchy in Mexico were part of a concerted conspiracy to destroy America’s republican example to the world.25

THE UNION’S VICTORY ALSO FORCED CHANGE ON ITS NORTHERN border. The Civil War had served as a sharp reminder to Britain of the vulnerability of Canada. Confederates had launched terrorist raids from Canada into New England late in the war, and the Irish Fenian Brotherhood, made up of Union veterans, had conducted raids in the opposite direction after the war. Both were designed to drag Britain into war with the United States. Britain decided its imperial priorities lay in Europe and Asia, not Canada, and during the Civil War began transforming British North America into a semiautonomous nation that would defend itself.26

What was commonly referred to as “Canada” was a constellation of colonial provinces, each subject to British rule but with little political connection to one another. A series of conventions laid the groundwork for a new confederation, and in 1867 the “Dominion of Canada” was born. Officials prudently decided not to call it the “Kingdom of Canada” for fear of provoking its republican neighbors. When William Seward arranged for the US purchase of Alaska from Russia, also in 1867, Canada annexed provinces below Alaska to form one contiguous confederation, extending along the entire US border.27

Russia’s sale of Alaska was yet another sign of the withdrawal of European empires from the Western Hemisphere. During the Civil War Russia had maintained a benign neutrality toward the Union by rejecting British and French entreaties to join their multilateral scheme for intervention in 1862 and again in 1863. A visit by Russian fleets to New York City and San Francisco in the fall of 1863 was widely interpreted as a gesture of support for the Union. US ships festooned with flags, full-dress banquets, lengthy toasts, and laudatory speeches had welcomed the Russian visitors. Seward’s peaceful purchase of Alaska was also interpreted as a sign of good relations between the two countries, but it signified as well America’s new capacity to enforce the Monroe Doctrine.28

THE REPUBLICAN RESURGENCE OF THE LATE 1860s ALSO SHOOK THE thrones of Europe. Lord Palmerston, the embodiment of the British ruling classes, died in October 1865, and Gladstone inherited a Liberal Party badly split over the vexing issue of democratization. The Reform League, a new grassroots movement, sponsored huge meetings across Britain in the summer of 1866. Brandishing red flags and wearing liberty caps, crowds of men and women poured into London’s Trafalgar Square in tremendous displays of support for the expansion of voting rights. In May 1867 the government turned out thousands of police and armed troops to suppress reform “riots” in Hyde Park, but the Radicals refused to be intimidated. Facing what amounted to revolutionary defiance, the British governing classes caved in. Parliament passed the Reform Act of 1867, which vastly expanded voting rights for adult males and brought John Bright’s dream of transatlantic Anglo-American republicanism that much closer.29

In France the opposition to Napoleon III’s imperial regime was also emboldened by the American example. In a widely noted essay published in May 1865, the Comte de Montalembert, one of France’s leading liberal Catholic intellectuals, eulogized Lincoln and heralded the Union’s victory as a harbinger of democracy’s triumph. “Every thing which has occurred in America, from all which is to follow in the future, grave teachings will result for us,” Montalembert prophesied, “for, in spite of ourselves, we belong to a society irrevocably democratic.”30

Napoleon III’s reign came to its disastrous end three years after Maximilian’s denouement in Mexico. Overreaching as always, the French emperor provoked war with Prussia in 1870. He was ignominiously captured while leading the French army at the Battle of Sedan and was thrown into prison. The opposition seized control of the French government and proclaimed the Third Republic in early September 1870. Following a brutal siege, starving Parisians, who had been reduced to eating rats, dogs, cats, even zoo animals, surrendered to Prussian forces in February 1871, and Bismarck led his victorious army through the streets of a city draped in black. The deposed emperor Napoleon III was later released by the Prussians and, with his wife, Eugénie, fled to exile in Chislehurst, England, where he died in 1873. The radical Paris Commune took command of the city, and for several weeks in the spring of 1871 the revolutionary Communards wreaked havoc on the symbols of aristocratic privilege in Haussmann’s glittering city, leaving Napoleon III’s Tuileries Palace in smoldering ruins. Thus, amid revolutionary violence and insoluble political divisions, France resumed its troubled experiment with republicanism.31

Whereas France was famed for the excesses of republicanism, Germany became known for the new authoritarian state that Otto von Bismarck, the “Iron Chancellor” of Prussia, was building. His vast, centralized German state had annexed large portions of Austria following its quick victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. At the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Germany took over the former French province of Alsace and parts of Lorraine. Bismarck was changing the map of Europe in other ways, too. The 1866 war had forced Austria to surrender Venice to the Italians. Then the Franco-Prussian war forced Napoleon III to abandon Rome and on September 20, 1870, Italian forces stormed the gates of Rome and drove Pope Pius IX into virtual imprisonment within the Vatican. The Italian Risorgimento was complete and with Rome about to become the capital of united Italy. The destiny of united Germany still lay ahead.32

Bismarck never had much patience for democracy. “The great questions of the day,” he once famously said, “are not decided by speeches and majority votes . . . but by blood and iron.” In 1863, during a tedious round of debate among politicians in the Diet over what he described as some petty “German squabble,” Bismarck sat at his desk and feigned taking notes, but he was penning a letter to his old American friend John Lothrop Motley, the US minister to Austria. “My Dear Motley . . . I hate politics, but, as you say truly, like the grocer hating figs, I am none the less obliged to keep my thoughts increasingly occupied with those figs. . . . I am obliged to listen to particularly tasteless speeches out of the mouths of uncommonly childish and excited politicians.” Moving from German to English and back again, even throwing in a bit of Italian, Bismarck then took a jab at his idealistic American friend. “You Anglo Saxon Yankees have something of the same kind also. Do you all know exactly why you are waging such furious war with each other? All certainly do not know, but they kill each other con amore [with love], that’s the way the business comes to them. Your battles are bloody, ours wordy.”33

The unlikely friendship between these men went back thirty years to their days together at the University of Göttingen, where the earnest young American distinguished himself as a scholar and Bismarck made his mark as a bon vivant notorious for drinking, dueling, and eccentric dress. Motley became an eminent historian, and his eloquent advocacy of the Union cause in Europe had earned him an appointment from President Lincoln as US minister to Austria. His friendship with Bismarck had endured vast and growing differences in political ideology. “He is as sincere and resolute a monarchist and absolutist as I am a Republican,” Motley once told his daughter. “But that does not interfere with our friendship.”34

It seemed to this time. Motley did not reply to Bismarck for a full year, and finally the Prussian leader reached out again, employing an unmistakable tone of jocular reconciliation, if not apology, to soothe his old friend “Jack” and implore him to come visit in Berlin. “Let politics be hanged, and come to see me,” Bismarck fairly begged. “I promise that the Union jack shall wave over our house, and conversation and the best old hock shall pour damnation upon the rebels.”

Motley’s pique seemed calmed by his old friend’s amiable plea, but he could not resist taking up the question that had gnawed at him for more than a year: “You asked me in the last letter before the present one ‘if we knew what we were fighting for.’ I can’t let the question go unanswered. We are fighting to preserve the existence of a magnificent commonwealth which traitors are trying to destroy, and to annihilate the loathsome institution of negro slavery, to perpetuate and extend which was the sole cause of the Treason. If men can’t fight for such a cause they had better stop fighting forevermore.”35

Bismarck’s question echoed the one Garibaldi had raised with US diplomats at the beginning of the war: was this no more than an American quarrel, just another petty local boundary dispute of no great consequence to the larger world? On this occasion Motley—and the Union—had an answer.

IN PARIS ONE EVENING IN APRIL 1865, AT A GATHERING AT PROFESSOR Laboulaye’s home, friends began discussing the idea of a monument to the friendship between France and America. The discussion seemed to grow out of the same spirit as the “two sous” campaign for Mrs. Lincoln’s medal. Censorship still made it risky for Laboulaye and his friends to take action, but five years later the idea was resurrected during another evening gathering of friends at Laboulaye’s country home. Among them was Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, a young artist from Alsace, which had recently been lost to the Germans. Bartholdi was on his way to America, and the group commissioned him to solicit cooperation during his visit and come up with a design for the monument. After days at sea Bartholdi arrived in New York Harbor and was seized by the idea for a colossal allegorical figure of La Liberté éclairant le monde (Liberty enlightening the world), which would stand at the gateway to America.36

“She is not liberty with a red cap on her head and a pike in her hand, stepping over corpses,” Laboulaye explained to French donors a few years later. Liberty “in one hand holds the torch—no, not the torch that sets afire but the flambeau, the candle-flame that enlightens.” In her other hand, “she holds the tablets of law.” Bartholdi had already begun work on the statue, and as the American centennial approached the unfinished Liberty could be seen looming over the streets of suburban Paris. He was able to send the head and torch-bearing arm to the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876, but another ten years would pass before the entire statue was ready to cross the Atlantic.37

39. La Liberté éclairant le monde (Liberty enlightening the world), under construction at the workshop of Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi in Paris before it was erected in New York Harbor in 1886. (AUTHOR’S PRIVATE COLLECTION)

By 1886 when Liberty Enlightening the World was erected in New York Harbor, the resurgent republican spirit of 1865 was giving way to a conscious campaign of reconciliation that asked Americans to lay aside, if not forget, the disturbing legacy of slavery and secession that had torn the nation apart twenty-five years earlier. Americans were beginning to settle on the idea of the Civil War as a senseless and unnecessary interruption of national progress. Thanks to Emma Lazarus’s moving poem “The New Colossus,” written in 1883, the monument would be interpreted as America’s welcome to the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” and escaping the Old World to find refuge in a uniquely American asylum of liberty. In time the Statue of Liberty, as it came to be known, became the symbol of America as a sanctuary of freedom for refugees rather than Liberty Enlightening the World, the monument to the perseverance of republicanism throughout the world. As a national icon the Statue of Liberty would play a central role in the story of exceptionalism that Americans tell themselves about themselves.

But Laboulaye and Bartholdi had something else in mind. With her gaze fixed across the Atlantic, Liberty faces Europe and is striding toward it while at her feet lay the broken chains of slavery. In one hand she holds a tablet marked “July 4, 1776,” and in the other the raised flambeau “radiant upon the two worlds,” as Bartholdi described it.

Liberty Enlightening the World remains the greatest monument to America’s Civil War as the cause of all nations. It honors the international struggle that in the 1860s shook the Atlantic world and decided the fate of slavery and democracy for the vast future that lay ahead.38