12

IMMIGRANT ORGANIZATIONS

Civic (In)equality and Civic (In)visibility

Irene Bloemraad, Shannon Gleeson, and Els de Graauw

WHY IS THE STUDY OF IMMIGRANT ORGANIZATIONS a neglected field, and what do we learn in studying such organizations? Scholars of immigration have largely focused on how macro-level phenomena (such as labor markets or ethnoracial hierarchies) influence immigrant incorporation, or on how individual-level attributes (like immigrants’ education) shape outcomes such as employment, intermarriage, or voting. They have rarely examined how organizations affect immigrants, or how immigrants create organizations. Conversely, within research on nonprofit organizations and civic associations, attention to immigrant communities has been peripheral at best. We argue that researchers and practitioners need to pay attention to the civic infrastructures of immigrant communities, that is, the set of somewhat formalized and organized groups that are neither public institutions nor for-profit businesses and that serve or advocate for these communities.

Why should we do so? Bringing the study of the third sector into conversation with immigration showcases the challenge of what we call civic inequality, that is, a disparity in the number, density, breadth, capacity, and visibility of organized groups in a community. Civic inequality is a cause for concern because it can impede immigrants’ access to social services, employment, and leadership opportunities as well as their civic voice in society. Understanding civic inequality also goes beyond the case of immigrants. It should be part of any analysis of nonprofit organizations and marginalized communities.

Still, immigrants deserve specific attention in the nonprofit field. There is a glaring disjunction between the paucity of research and the number of people who are immigrants. As of 2017, around 43 million foreign-born individuals were living in the United States (13 percent of the population), and 7.9 million were living in Canada (21 percent of the population). Additionally, about one in eight residents of France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom, and over one in four residents of Australia and Switzerland, are foreign-born (UNDESA 2017). Although some of the frameworks used to analyze nonprofits and voluntarism can easily extend to immigrants and immigrant organizations, bringing immigration into third sector analysis also raises new questions and demands new explanatory models.

The small but growing body of research on immigrant organizations and immigrants’ civic engagement underscores at least two key considerations for researchers and practitioners. First, we must take into account the additional barriers—and, sometimes, opportunities—that migrants’ legal status brings to nonprofit organizing and associationalism. This is not just a dichotomy between undocumented status compared to the presumption of citizenship evident in most nonprofit scholarship. It is also about studying and understanding the distinct resources, institutional support, and exclusions that come with the multiple legal statuses that people can hold. Noncitizen legal permanent residents or formally recognized refugees who have a pathway to citizenship are generally less vulnerable to deportation and may enjoy more legitimacy in the eyes of citizens than other foreigners. Migrants who hold a much more precarious status with no permanent residence or access to citizenship—such as temporary workers, international students, migrants given temporary humanitarian protection, or undocumented immigrants—face uncertain time horizons, hold fewer formal rights, have limited access to public services and benefits, and are susceptible to deportation. The challenges presented by one’s legal status often overlap with other barriers to civic equality, such as poverty, racial minority status, or limited skills in the majority language.

Second, attention to migration pushes researchers and practitioners to pay attention to transnationalism, both in immigrants’ orientation to civic engagement and in nonprofits’ activism. Immigrants’ prior political socialization—that is, their experiences with a civic and political system different from that of the host country—can shape immigrants’ third sector participation in the country of settlement. Such experiences can also lead to new associational forms or organizing strategies. One example is that of tandas, or informal loan clubs routinely used by Latinx immigrants to provide community-funded loans. Because migrants have life experiences rooted in more than one country, they may also engage in transnational political and civic activities that connect home and host countries through third sector organizing, volunteerism, and charitable giving. This can generate associational dynamics distinct from the activism of traditional international nongovernmental, development, or advocacy organizations (international nongovermental organizations, or INGOs). For example, how does the work, mission, and administration of an INGO like Amnesty International or Doctors Without Borders compare to the development assistance or donations that immigrants send back to their homeland through hometown associations or private charities? In some cases, migrant remittances and activism are encouraged by the sending state, as is the case for the Mexican Tres por Uno (Three for One) matching grant program. In other cases, migrant groups risk surveillance, detention, or even death, in either their home or host country, because of their third sector activities. This is especially the case if their politics, homeland ties, or religion lead them to be labeled subversive or terrorists.

The time is thus ripe for scholars to examine the specificity of immigrant civic engagement and immigrant organizations. We conceptualize an immigrant organization as a civil society or nonprofit organization that serves or advocates on behalf of one or more immigrant communities, promotes their cultural heritage, or engages in transnational relations with countries or regions of origin (de Graauw, Gleeson, and Bloemraad 2013:96). Such organizations may include second- or later-generation individuals of a particular cultural, ethnic, religious, or national-origin background, and even some citizens without immigrant origins. However, a substantial part of the organization’s interests or activities should involve issues that tend to distinguish immigrants from native-born citizens, such as legal status barriers, linguistic or cultural obstacles to service, or concern over economic or political development in the country of origin.

Attention to civic and nonprofit organizing is also important for scholars of migration. Much of the migration literature focuses on immigrants’ individual- or micro-level integration, including research on civic and political engagement. Less attention has been paid to the meso level of immigrant community life, that is, to the voluntary, civic, and nonprofit groups that are the bread and butter of third sector scholarship. Although mainstream nonprofit organizations—ones that do not focus on immigrants and their children—can address some immigrant needs or associational desires, targeted immigrant outreach is rare. In part, this is because mainstream nonprofits often do not have the capacity or interest to invest in multilingual or multicultural outreach to address immigrants’ needs and interests. Sometimes funding sources come with restrictions that prevent nonprofits from helping undocumented residents, as is the case with U.S. federal grants to provide legal aid to poor people. Immigrant populations also have new social and cultural interests or support needs—such as wanting to organize in particular religious communities or needing immigration legal services—that mainstream organizations have trouble identifying, funding, or fulfilling.

Gaps in service delivery and civic organizing feed into what we conceptualize as civic inequality. In one version of civic inequality, differences in civic engagement, at the individual level, can lead to unequal aggregate participation between groups of people, such as between people who are immigrants and those who are native-born. However, civic inequality—and its opposite, civic equality—can also be understood as a group-level attribute, distinct from individual- or micro-level immigrant integration measures or large-scale, macro-level socioeconomic and political structures that scholars usually study. In this version, civic inequality at the meso level is a disparity in the number, density, breadth, capacity, and visibility of organized groups in a community. We advocate in particular for such an organization-focused approach. To advance this research agenda, we provide a detailed discussion of how to measure and analyze civic (in)equality.

Distinguishing immigrants’ meso-level civic infrastructures from micro-level participation is analytically important and carries real-world consequences. The gap between what existing nonprofits do for immigrants and immigrants’ ability to create new associations can be vast and highly problematic for immigrant communities. For instance, local governments often allocate grants to community-based organizations for human or social services, or to subsidize a cultural or sports activity. Absent immigrant-oriented organizations, migrant communities may fail to secure these resources, which can stymie their social integration as well as their ability to have a voice in civic affairs. Conversely, when immigrant communities enjoy a rich infrastructure of third sector organizations, they may benefit from a greater civic presence and voice and faster societal integration. Thus, just as third sector scholars should consider immigrant organizing in their scholarship, migration scholars should better understand how nonprofit organizations and civic engagement shape migration and settlement patterns. More broadly, we believe that the concepts and our proposed empirical measures of civic (in)equality and civic (in)visibility can be extended beyond immigrant populations to study and understand the nonprofit field more generally.

Gaps in Research on Immigrants and the Third Sector

Three distinct academic literatures touch on immigration and the third sector: studies of immigrant integration, research on interest groups and social movements, and scholarship on nonprofit organizations.

Immigrant Integration and Immigrant Organizations

For over a century, U.S.-based social scientists, particularly those in sociology, have studied immigrant integration or assimilation, as it was long called. Their focus has usually centered on measuring and explaining immigrants’ economic, social, and cultural integration. Scholars debate whether intergenerational integration proceeds along a straight line, a bumpy one, or distinct pathways that are segmented by immigrants’ human capital, racial minority status, and social networks within the community.1 The focus is generally on the second, U.S.-born generation, who are more removed from the migrant experience.

Political scientists’ interest in immigrant incorporation was first articulated through the lens of urban politics and political machines and later in terms of electoral coalition-building, partisanship, and voting.2 Yet voting—which is limited to citizens in most jurisdictions—is only a small slice of immigrants’ political and civic engagement (Martinez 2005). Interest in the political and civic incorporation of foreign-born residents waned as political science shifted to focus on minority politics, with special attention to Black and Latinx politics and growing interest in Asian American political activity. Scholars of minority politics have tended to focus on pan-ethnic solidarity and mobilization, downplaying differences among and within immigrant generations or the unique barriers of noncitizenship.

Across these studies and irrespective of discipline, few scholars adequately consider immigrant communities’ civic infrastructures. Rather, in theorizing the determinants of immigrant integration, social scientists focus on how macro-level phenomena such as labor markets, electoral regimes, and ethnoracial hierarchies influence incorporation patterns, or on how individual attributes, like immigrants’ education, shape outcomes such as employment, intermarriage, or voting. In its report on the state of immigrant integration in the United States, the National Academy of Sciences concludes that although “the evidence thus far suggests that civil society groups—whether organized by immigrants or predominantly organized by native-born citizens . . .—can facilitate integration,” overall “research on the civic and organizational foundations of immigrants’ integration is underdeveloped” (NASEM 2015:193).

Immigrant organizations have featured a bit more in historians’ work (e.g., Moya 2005). In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, immigrant-run private charities and voluntary organizations helped compatriots get a job, obtain a business loan, acquire citizenship, or secure food, clothing, and funeral benefits during tough times. Starting in the late nineteenth century, U.S.-born social reformers became involved, establishing settlement houses, including the famed Hull House in Chicago. Funded by religious groups, charitable associations, and wealthy residents, settlement houses largely targeted the poor, a population that included many immigrants in large Midwestern and northeastern U.S. cities at the time. Today, mainstream nonprofit social service organizations and various levels of governments provide some of the assistance that immigrant associations or settlement houses did a century ago. Yet immigrant-focused nonprofit organizations—including formally incorporated and registered nonprofits as well as more informal groups—still remain important sites for immigrant civic engagement and service provision (de Graauw 2016; Ramakrishnan and Bloemraad 2008).

Beyond the United States, scholars take diverging views of the impact of immigrant organizations on integration trajectories. Most believe that engagement with ethnic organizations reinforces immigrants’ ties to each other. Whether this helps or hinders integration is a point of debate. Over fifty years ago, Raymond Breton (1964) coined the term “institutionally complete” to describe immigrant communities where members could conduct most aspects of their lives—work, recreation, religious practice, and social interactions—within ethnic organizations. Studying immigrants in Montreal, Breton concluded that although institutional completeness might prevent interethnic marriage and reinforce an ethnic identity (both considered barriers to immigrant integration), it also facilitated political engagement in the host society (and thus incorporation). Studying immigrant-origin communities in the contemporary Netherlands, Meindert Fennema and Jean Tillie (1999) conclude that immigrant organizations can increase social capital within immigrant communities, thereby increasing social trust and political participation. In these accounts, immigrant organizations may insulate or isolate immigrants in some regards but also promote civic incorporation in other ways. Some also view the biculturalism facilitated by ethnic organizations as psychologically beneficial for immigrants (Berry 2005; Nguyen and Benet-Martínez 2013). Conversely, others claim that excessive intra-immigrant interaction creates “parallel lives,” in which immigrants remain isolated from mainstream society.3 In these accounts, immigrant-run or immigrant-serving organizations tend to be viewed negatively, as slowing or preventing immigrant integration, since they promote bonding social capital over bridging ties.4

Interest Groups and Social Movement Organizations

If the immigrant integration literature is characterized by a primary focus on individuals and relatively little attention to organizations, research on advocacy or interest groups and contentious political and civic behavior has the opposite problem: it views organizations as significant, but it largely ignores immigrants.

In the United States, researchers have studied interest and advocacy groups run by or advocating on behalf of ethnoracial minorities (Berry and Arons 2005; Hung 2007; Minkoff 1995), but much of this work fails to distinguish minorities by nativity and immigrant generation. Thus, conclusions about Latinx or Asian American organizations do not distinguish between foreign-born individuals and later generations made up of the children and grandchildren of immigrants. The failure to examine generational differences makes it impossible to carefully consider the implications of migration or citizenship status on the development, mission, or activities of organizations, or to probe the effects of homeland political socialization on immigrant organizing in the host country. It also obscures language access challenges usually felt much more intensely by first-generation immigrants. Similarly, those interested in civic voluntarism and organizational membership have rarely considered the impact of immigrant background on civic engagement, although they have been attentive to ethnoracial background.5 Only in the last decade or so has U.S.-based organizational scholarship considered immigration status or immigrant background as a key factor shaping civic and political engagement (de Graauw 2016; Marwell 2007; Wong 2006).

The silence around immigration stems from conceptual blind spots as well as data constraints. Many surveys that are used to study civic engagement do not capture immigrant-specific variables such as country of birth, immigration status, citizenship status, or length of residence in the country, making it impossible to identify immigrant civic engagement. And even when such questions are asked, the number of immigrants included in a survey is often too small for nuanced analysis. In the United States, if a nationally representative survey includes one thousand to two thousand respondents, analysts will be lucky to have data on a hundred to two hundred foreign-born people. This group will be highly heterogeneous, hailing from many different countries, holding multiple immigration statuses, and having resided in the United States for just a few years or multiple decades. Teasing out the relative impact of home country, legal status, and length of residence on immigrants’ civic engagement becomes almost impossible.

Fortunately, available statistical data are slowly improving, which is critical to document civic inequalities. One analysis of the 2014 Current Population Survey Volunteerism Supplement finds that rates of volunteerism are nearly twice as high for native-born residents of the United States (27 percent) than for foreign-born residents (15 percent), and that volunteerism is higher among naturalized citizens (18 percent) than among noncitizen immigrants (13 percent) (NASEM 2015:191). European data appear to show similar patterns (Voicu and Şerban 2012). Several in-depth organizational ethnographies also provide insights about immigrant civic engagement, though only for select cities and specific immigrant communities (e.g., Chung 2007). When it comes to research on contentious action, scholars in this field have long recognized the importance of social movement organizations (SMOs). By focusing on organizations rather than individual-level participation, this line of research gets closer to our idea of meso-level civic inequality. But researchers in the field have largely been silent on immigrant mobilization.6 As Irene Bloemraad, Kim Voss, and Taeku Lee argue, “the assumption undergirding most studies of social movements is one of the protesting citizen. Protesters might have second-class citizenship. . . . They can be jailed, attacked, and obstructed . . . but they cannot generally be thrown out of the country altogether” (2011:5, emphasis in original). Immigrants’ vulnerability to detention and deportation, as well as their often more limited access to resources, public legitimacy, and institutional support, carry important repercussions for immigrants’ ability to create and sustain social movement organizations.

The lack of attention to immigrants is unfortunate since it is clear that a robust civic infrastructure can help immigrants advance their issues in the public sphere and engender pro-migrant social movements, despite noncitizenship. The pro-immigration protests of 2006 brought millions of people onto the streets (Voss and Bloemraad 2011). The “DREAMer” movement, which mobilizes undocumented youth to advocate for those without legal status, has built powerful, influential nonprofit organizations (Nicholls 2013). Labor unions, which are longstanding actors in the third sector, have been increasingly involved in immigration issues, partly in response to declining union membership and the growing immigrant workforce (Milkman 2006). Organizations are thus important for understanding immigrant advocacy, and the inclusion of immigrants in existing organizations is significant to understanding organizational capacity, group goals, and change over time.7

Nonprofit Organizations and Immigration

Third sector research on the creation, persistence, and disbanding of nonprofit organizations has rarely considered the specificity of immigrant communities. Yet nonprofits intersect with immigrants in multiple ways. Religious institutions, often a first point of contact for immigrants in their new environs, are a vital component of the newcomer community and the integration process (Foley and Hoge 2007; Kivisto 2014). Following World War II, the U.S. government increasingly worked with voluntary resettlement agencies (VOLAGs) to help displaced people and refugees secure housing, find jobs, and get established in the United States (de Graauw and Bloemraad 2017). These agencies, some with religious roots and others of secular origin, now constitute the backbone of the refugee resettlement process, working in partnership with federal, state, and county agencies through public grants and private giving (Bruno 2015). Beyond refugees, nonprofit organizations provide other immigrants with health and legal services, counseling, and emergency food or housing assistance, especially in cases where migrants are explicitly or effectively barred from public programs because of their immigration status (Cordero-Guzmán 2005; de Graauw 2016; Marwell 2007). The small but growing literature on immigrant-serving organizations underscores the important work that the third sector does for immigrant and refugee communities.

Classic theories of the nonprofit sector contend that the creation of nonprofit organizations is motivated by failures of the market or of government (e.g., Grønbjerg 1998; Hansmann 1987). These theories may well apply to nonprofits serving immigrants. In most places, immigrants constitute a minority of the population, and hence profit-driven businesses may be less willing or able to provide goods and services specific to an immigrant minority, producing market failure. Similarly, governments may be less likely to serve immigrant populations, given public opposition, immigrants’ lack of voting power, and the inability of large government bureaucracies to respond efficiently to the evolving needs of changing migrant populations, thereby producing government failure. These market and government shortcomings create needs and opportunities for nonprofit organizations to provide goods and services to the newcomer community.

Existing nonprofit scholarship does not, however, offer a good theoretical framework for understanding when, why, and how nonprofits focus on immigrants and whether immigrants are better served through mainstream or immigrant organizations. Immigrants do not necessarily have to establish their own nonprofits; nonprofit organizations rarely make membership or service provision contingent on nativity. Thus, in some cases, immigrants derive the same benefits from the human and social services, advocacy, and social, cultural, or recreational activities of existing nonprofits as nonimmigrants. Mainstream baseball leagues, animal rights organizations, and food pantries can all include immigrants. Nonprofit scholars have not investigated the relative benefits or trade-offs of involvement in immigrant versus mainstream organizations. Immigration and civil society researchers have paid more attention, debating whether bonding (within-group) organizations or bridging (mainstream) organizations better advance immigrant integration and community social capital. There is no clear verdict, in part because of methodological difficulties in identifying what drives an organization’s impact on integration.

We suspect that the effects of immigrant organizations tend to be positive. Indeed, concerns about “too much” immigrant organizing rest on the unquestioned and problematic assumption that immigrants have the option of participating in a mainstream organization as compared to setting up their own. A more likely alternative is that, absent immigrant organizations, there is a lack of nonprofit support for immigrants. For example, mainstream organizations may not have services germane or easily accessible to immigrants, and they often lack translators or multilingual staff, culturally appropriate human services, or immigrant-related legal services (de Graauw et al. 2013). Mainstream organizations also often engage in inadequate outreach to immigrant communities (e.g., de Leon et al. 2009; LaFrance Associates 2005). This creates barriers for elderly immigrants or immigrant parents who may wish to join a senior center or parent-teacher organization, respectively, but who struggle with English or do not know that such organizations exist. Existing research shows that immigrant-oriented community-based organizations provide bilingual and bicultural human services (Cordero-Guzmán 2005; Marwell 2007), flag immigrants’ unique needs to decision makers (de Graauw 2016), mobilize immigrants’ political participation (Wong 2006), help low-income and precarious immigrant workers, including those without legal status (Fine 2006; Gleeson 2012), and promote cultural vitality (Hung 2007). The activities that mainstream organizations provide, such as football or ballet, may differ from immigrant interests and passions, such as cricket or Mexican folkloric dance.

In these cases, there is a community need for immigrant nonprofit organizations. Based on 501(c)(3) nonprofit data for organizations in four cities in the San Francisco Bay Area, we found that between 2004 and 2007, the proportion of immigrant nonprofits, at 17 percent of the total of all registered nonprofit organizations, was much smaller than the immigrant share of the total population, which stood at 38 percent (de Graauw et al. 2013). We also found that although a longstanding immigrant gateway city such as San Francisco allocated public money to immigrant nonprofits in rough proportion to the percentage of immigrants in the city’s population, newer gateways such as San Jose or immigrant-rich suburbs in Silicon Valley did not, even as foreign-born residents constituted about half of the region’s poor population. These data raise the possibility of significant civic inequality for immigrant communities, even in cities and metro areas with large immigrant communities.

Bringing Immigrants and Immigration into the Nonprofit Conversation

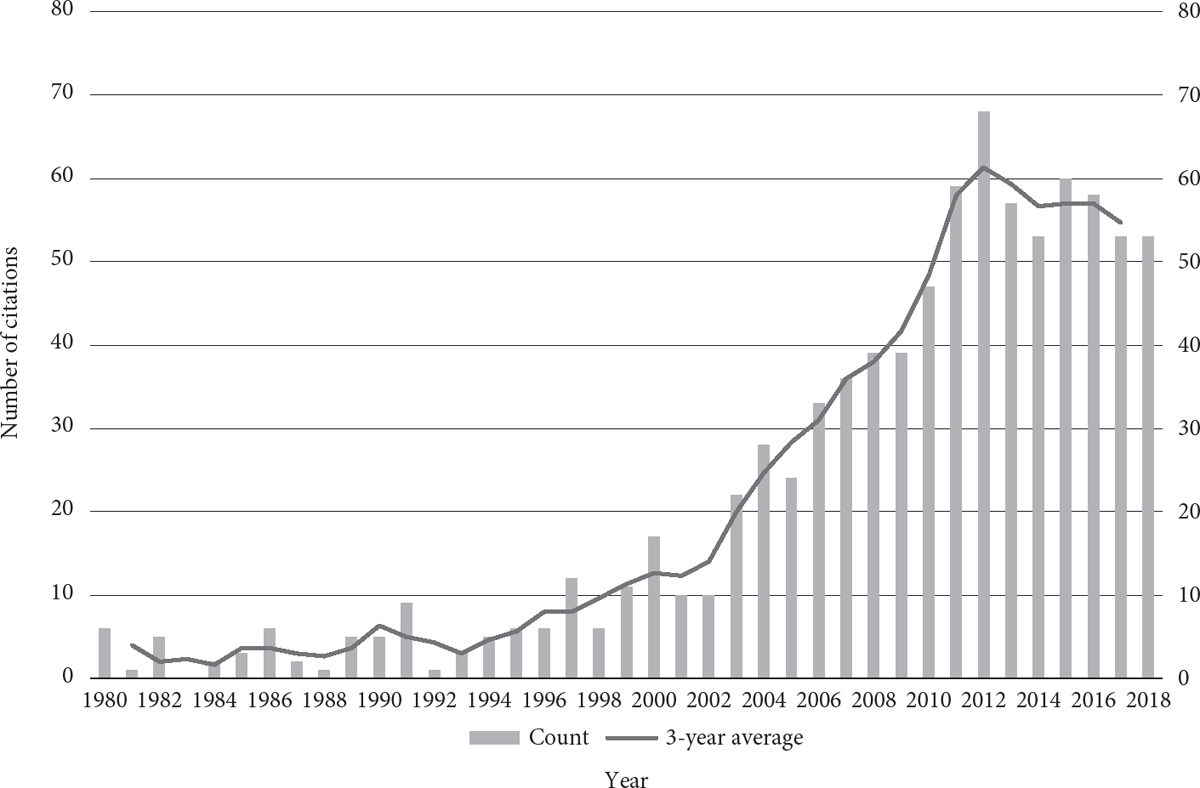

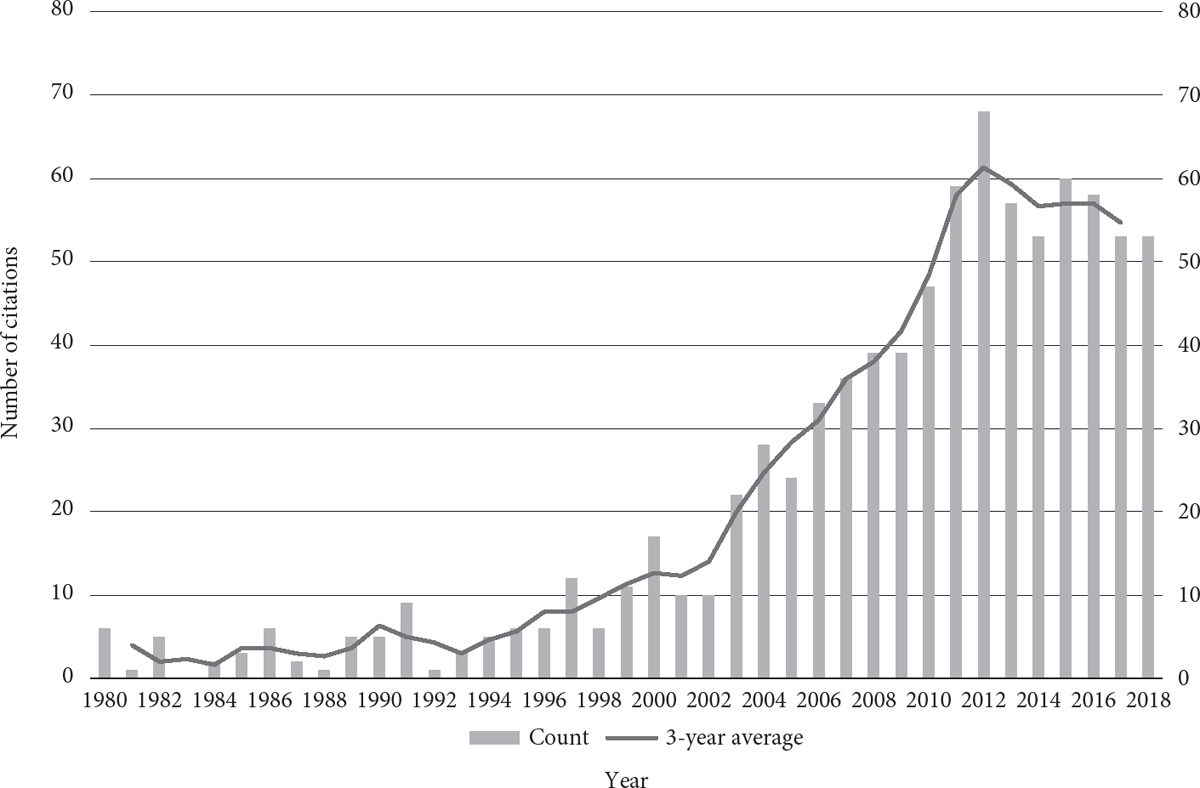

The historic neglect of scholarship on immigration and nonprofit organizations has been rapidly changing over the past decade. As Figure 12.1 shows, through the 1980s and 1990s, Google Scholar counts fewer than ten items per year with titles that include the word “organization” or “organisation” combined with “immigrant,” “migrant,” or “refugee.” But whereas the average number of items was barely three per year in the 1980s, since 2010, Google Scholar counts over fifty-six items per year, an almost twenty-fold increase.8 This burgeoning literature provides an emergent map of key findings, as well as intriguing paths that need to be explored.

How should we bring immigrants and migration into the nonprofit conversation? In what follows, we primarily focus on legal status, usually the factor that most sharply distinguishes migrants from others in a society. But we also underscore the need for more research on the consequences of migrants’ cross-border experiences and ties, for example, in transforming existing associational practices and organizational forms. To illustrate the importance of legal status and a transnational lens, we draw predominantly on U.S.-based scholarship and secondarily on research in Western Europe and Canada. Although this reflects the geographical focus of existing scholarship, future research and theorizing should engage with dynamics in other settings, such as the organizational efforts of migrant workers in the oil-rich Gulf states or of refugees outside traditional immigrant-receiving countries in the West.

Figure 12.1 Citations in Google Scholar with “(im)migrant” or “refugee” and “organization(s)” or “organisation(s)” in the title, 1980–2018

Note: There has been a fifteen-fold increase in the number of articles, from four in 1981 (three-year average) to a high of sixty in 2012. Because Google Scholar can be behind in finding publications issued in the last one to two years, it is likely that the average of fifty-five to sixty citations per year has held constant.

Source: Authors’ calculation from Google Scholar. See note 8 for methodology.

Immigrant Civic Engagement: The Individual Level

Attention to immigrant populations raises new issues of individual-level civic inequality: Who is able to participate and who actually engages in the nonprofit sphere? The limited survey data suggest that, in the United States, foreign-born individuals participate in canonical civic activities less than native-born citizens (NASEM 2015; Ramakrishnan and Baldassare 2004). In Europe, too, immigrants are less likely to be members of an organization and belong to fewer associations than the native born, although differences decrease with length of residence and often disappear by the second generation (Voicu and Şerban 2012).

Intersectional identities also matter. For example, within immigrant communities, some research suggests that women may be more involved, perhaps because of their frequent role as children’s primary caregivers, which requires interfacing with schools, health care services, and government bureaucracies (Jones-Correa 1998; Milkman and Terriquez 2012). Such interactions can build civic skills and political consciousness that motivate engagement. Race, class, and sexuality can also shape immigrant civic activity.

Part—but not all—of the gap between foreign-born and native-born populations’ engagement can be understood through existing explanatory frameworks. As among the native born, strong predictors of immigrants’ civic engagement include education, employment, and trust in others (Morales and Giugni 2011; Sundeen, Garcia, and Raskoff 2009; Voicu 2014; Voicu and Şerban 2012). To the extent that immigrants may have more modest levels of education (e.g., because of limited educational opportunities in their homeland) or are more likely to live in poverty or economic insecurity (because of language barriers or discrimination), these known obstacles to participation greatly impact certain immigrant communities. In the United States, whereas 15 percent of native-born citizens live below the federal poverty level, the proportion rises to 18 percent among the foreign born.9 The latter estimate obscures the impact of immigration status and the particular advantage of citizenship: of immigrants who report being naturalized citizens, only 11 percent fall below the poverty line, but 25 percent of noncitizens are poor by federal standards. Citizenship status also intersects with other attributes to stratify civic participation. Although 35 percent of naturalized immigrants hold a four-year college degree or higher—a slightly higher percentage than the native-born population at 31 percent—only 23 percent of noncitizens enjoy high levels of education, and 39 percent have no high school diploma.

We need, however, additional, immigrant-specific explanations for individual-level variation in civic participation. These include the impact of language skills, national origin, and immigration status. Immigrants must demonstrate a working knowledge of English to become a U.S. citizen, and thus lack of citizenship can reflect linguistic barriers to mainstream civic participation. But lack of U.S. citizenship may also signal that a person is undocumented or holds a temporary or precarious legal status. Fear of deportation can reduce civic participation and limit the pool of leaders or alter the civic activities that undocumented residents are willing to take on (Gast and Okamoto 2016). For example, although undocumented workers are no longer considered unorganizable, unions and worker centers must address unique barriers to immigrants’ participation (Milkman 2006). Evidence also suggests that temporary residency status can discourage immigrants from claiming their rights and possibly stymie their civic engagement more generally (Griffith and Gleeson 2017). Shifting political winds regarding immigration, such as during the administration of President Trump, can result in new anti-immigrant policies that make it more challenging or dangerous for undocumented immigrants to engage in the civic sphere. Lack of permanent legal residency clearly hurts third sector involvement, even if it is not an absolute barrier to it.10

Even for immigrants who are legally allowed to reside in the host country, lack of citizenship can be a barrier to creating, leading, or being a member of a nonprofit organization or civic association. Formal restrictions prohibit noncitizens from joining a political party or founding a political association in all eleven Central European countries of the European Union and in Turkey.11 Until 1981, France forbade foreign nationals from forming an association. Given xenophobic or anti-immigrant sentiments among the public, as well as government surveillance of Muslim immigrants for involvement with purported terrorist cells, some immigrants may not participate in a nonprofit or charitable organization, even where the law does not prohibit it, out of fear of drawing the attention of hate groups or government authorities (Chaudhary and Guarnizo 2016).

To understand individual-level civic integration, researchers can extend existing arguments about immigrant integration, either as a process of more or less straight-line assimilation across generations, or as a differentiated process of segmented assimilation by socioeconomic and racial minority status. Alternatively, especially in the first generation, we may need to view immigrants’ civic participation as embedded in a transnational field that is affected by both the context in the country of origin and the country of residence, contexts that vary in their social, economic, and political institutions (Levitt and Glick Schiller 2004). Immigrants can sometimes vote in homeland elections, even if they become naturalized citizens in the country where they live. The outreach efforts of political parties and consular institutions that coordinate with diaspora organizations—in the origin and host countries—may produce unique opportunities for immigrant civic engagement. In general, scholars studying the U.S. case have been more optimistic about the positive effect of homeland mobilization for domestic engagement, whereas the research in Europe is more mixed and raises the question of whether outreach by homeland groups might insulate or isolate migrants.

The experience of having lived in at least two distinct civic and political environments adds complexity to immigrants’ participation in the third sector. Researchers find that associational norms and social or political trust in both the sending and receiving countries help predict civic membership (Aleksynska 2011; Just and Anderson 2012; Voicu 2014). Transnational experience can be a benefit: homeland civic engagement (such as union organizing or participation in political movements) can provide leadership skills, unique viewpoints on associationalism, or organizing strategies that migrants tap in their new country of residence (Hagan 1994). Conversely, prior political socialization can also generate barriers. Especially for those from nondemocratic nations or countries rife with political corruption, migrants may hold different norms about voluntarism and charitable giving and be more suspicious or fearful of civic engagement. Still, home-country effects should not be overstated: the impact of host-society civic norms appears to be a stronger predictor of engagement than those of the homeland, especially as length of stay increases and immigrants become citizens.

Indeed, the willingness of a receiving country to extend citizenship to immigrants affects levels and processes of civic and political integration. Across nineteen European democracies, Aida Just and Christopher J. Anderson (2012) find that acquisition of citizenship increases noninstitutionalized political and civic engagement, especially among immigrants from nondemocratic countries. They suggest that migrants from nondemocratic countries may initially have fewer civic skills, less political knowledge, and weaker political trust or participation norms, but they may develop these norms and skills during the naturalization process, along with reassurances that participation is a right, or even a responsibility, of citizenship. Similarly, Bloemraad (2006) argues that Canada’s strong investments in settlement and multicultural policies help immigrants build community organizations and participate in the public sphere more than immigrants from the same homeland who must navigate the U.S. laissez-faire system of immigrant integration. In this sense, whether a receiving country has a relatively open and liberal citizenship policy—with support for integration—or whether it provides a more hostile reception affects immigrants’ civic engagement.

Local variation within a country also shapes nonprofit activity in immigrant communities. Local political culture, density of existing civic organizations, and demography can determine who is given a seat at the table for organizing (de Graauw and Vermeulen 2016). For example, in San Francisco—a city known for its progressive politics and long history of community involvement in addressing social and political issues—immigrants have created and participate in many nonprofit organizations that advocate for immigrant rights and routinely work with city agencies to provide services to immigrant communities. In Houston, a city more politically divided between Democrats and Republicans, we see notably less of this (de Graauw and Gleeson 2017). Differences between urban, rural, and suburban settings can also shape the evolution and persistence of immigrant organizations.

Immigrant Civic Engagement: The Organizational Level

Researchers must also consider civic inequality at the organizational level. Such civic inequality involves disparities in the number, density, breadth, capacity, and visibility of organized groups in a community (Ramakrishnan and Bloemraad 2008). Rather than focus only on individuals’ organizational membership, voluntarism, and civic activities—the primary focus of research on immigrants and the third sector to date—we argue that immigrant organizations merit study and analysis as a distinct unit of analysis.

As with most measures of inequality, we start from an assumption that communities should, all else equal, have roughly similar motivations, interests, and abilities for civic organizing. If some communities have greater organizational presence than others, we can speak of civic inequality. Inequalities may stem from different interests (some communities feel a greater need to organize than others), differential resources and skills to engage in associational life, or structural factors (such as immigration and settlement policy or immigration and citizenship status) that impede organizing for some while facilitating it for others. When organizational inequalities become large and durable over time, we can even speak of civic stratification. Conversely, where governments and foundations invest in immigrant communities, we may see patterns of organizational parity. Once established, immigrant organizations can be important vehicles for mobilizing resources and enacting and implementing laws that support immigrant needs (de Graauw 2016). At this organizational level, how does an analytical lens that pays attention to immigrants and immigration change what we know about the third sector?

One lesson is that policies quite removed from third sector scholarship, such as immigration and refugee law and their attendant programs, can affect third sector organizing. Existing debates over the founding and persistence of nonprofit organizations often focus on supply or demand arguments (e.g., Grønbjerg and Paarlberg 2001). A demand-side view privileges purpose: nonprofits emerge when they fill a need or interest not met by the business sector (market failure) or by the public sector (government failure), spurring formation of immigrant-run groups such as a Bollywood dance group or an immigrant advocacy organization. Consistent with demand arguments, some researchers find more immigrant organizations in communities with a greater concentration of poorer and more recent immigrants, who face high integration barriers because of limited language skills or lack of citizenship (Chan 2014; Hung 2007; Joassart-Marcelli 2013). Nonprofits located in these places fill an important demand for language-accessible and culturally appropriate services.

Supply-side accounts argue, in contrast, that many needs and interests exist, but organizational creation and survival require a sufficient supply of material resources, such as private giving (by individuals or foundations) or public funding (through government contracting), as well as human capital, such as community members’ leadership skills and connections. In line with such arguments, researchers find differences in nonprofit formation among immigrants from different national or ethnic backgrounds, variation that appears tied—at least in part—to the material and human resources internal to the community (Chaudhary and Guarnizo 2016; Joassart-Marcelli 2013).12 At a policy level, state welfare spending and municipal funding for antipoverty or urban development efforts also affect nonprofit creation and survival, including the vitality of immigrant organizations (de Graauw 2016; de Graauw et al. 2013).

But existing research also suggests that immigrant-specific factors matter. The concept of political opportunity structure, developed in research on social movements, is germane here: immigrant civic infrastructures can vary across countries and within them, depending on whether and how immigration law and migrant-targeted policies affect them. Scholars have demonstrated how the material resources and logistical support of U.S. refugee resettlement programs and Canadian government grants for immigrant integration and multiculturalism affect the number, density, and type of nonprofit organizations that serve distinct immigrant communities or bring immigrants together for social, religious, or recreational purposes (Bloemraad 2005, 2006; Chan 2014; Chaudhary and Guarnizo 2016; Hein 1997; Joassart-Marcelli 2013). Conversely, since undocumented immigrants in the United States are ineligible for most federally funded services, certain public grants or contracts are not available to help organizations that serve these migrant populations (de Graauw and Gleeson 2018). Law and policies can thus supply critical material resources, as with federally and philanthropically funded refugee resettlement, but they can also impede or block integration efforts. When policies change, the impact on immigrant organizations can be significant. President Trump’s decision to drastically downsize the U.S. refugee program in 2018 led dozens of refugee resettlement organizations reliant on U.S. State Department funding to close their doors (Vongkiatkajorn 2018). Bringing migration and immigrant organizations into the nonprofit scholarship thus requires researchers to consider how policy areas unconnected to the third sector nevertheless have an impact on the creation, persistence, and success of nonprofit and community organizations.

The dynamics of private funding can also play out differently for immigrant organizations. Beyond public grants or contracts, nonprofits also regularly garner revenue from membership dues, philanthropic gifts, corporate sponsorship, and fees for services. Immigrant-serving organizations can face disadvantages in attracting such private funding. Economic hardship within immigrant populations can reduce organizations’ ability to charge membership or service fees. The perceived illegitimacy of immigrants as deserving recipients of funds—because of their legal status or more generally their “foreignness”—can have an impact, as with the reluctance among some philanthropic funders to support immigrant organizations in politically conservative regions. Even when philanthropic donors specifically target immigrant communities, certain activities—such as citizenship assistance, fraud prevention, and get-out-the-vote campaigns—may garner more backing than other immigrant needs, such as deportation defense or criminal defense for incarcerated immigrants, because the former are deemed less politically controversial (de Graauw and Gleeson 2018). Overall, given the growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States and elsewhere, immigrant organizations operate in a more challenging environment than most mainstream organizations.

Measuring Immigrant Organizations, Civic (In)equality, and Civic (In)visibility

What would a research program that examines immigrant nonprofit organizations look like? How should researchers measure concepts such as civic (in)equality and civic (in) visibility?

Identifying the Universe of Immigrant Nonprofits

First, scholars need a sense of the universe of immigrant nonprofits. One tactic is to leverage formal data on incorporated nonprofit organizations. In the United States, this includes data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which captures the tax filings of most incorporated nonprofit organizations (de Graauw 2016; de Graauw et al. 2013; Gleeson and Bloemraad 2012). Researchers interested in immigrant communities have used similar registries in other countries, such as financial data on registered charitable organizations in Canada (Chan 2014) and business association records in the Netherlands (Vermeulen 2006). Government administrative data offer important benefits in data uniformity and scope, especially when the process of building original databases would require tallying thousands, if not millions, of organizations.

Despite advantages, these data also come with challenges. Official statistics such as 501(c) (3) IRS filings in the United States do not represent the full universe of community-based groups, producing organizational undercounts (Grønbjerg and Paarlberg 2002; Lampkin and Boris 2002). U.S. nonprofit registration data miss organizations with limited revenues and religious organizations, both of which are not legally required to register with the government. Germane to immigrant communities, these databases also exclude groups formed by people who do not know about registration requirements, find them onerous or antithetical to their mission, or put off formalizing or incorporating an organization, perhaps out of fear of surveillance by the government or by hate groups. Researchers estimate that federal IRS listings cover only about 60 percent of all civic organizations, an undercount also found among immigrant organizations in the San Francisco Bay Area (Gleeson and Bloemraad 2012; Grønbjerg and Paarlberg 2002). All in all, official databases are incomplete in listing formal immigrant organizations, and they do not tally the small and informal groups active in immigrant communities.

A second problem is that it is difficult to identify immigrant organizations in nonprofit registries. One strategy in the United States is to rely on existing codes that identify minority-oriented organizations. Certain National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE) codes that organizations enter on IRS Form 990 signal that a group engages in activities geared toward ethnoracial minorities. However, these codes can be imprecise for research on immigrants. Not all organizations that target ethnoracial minorities focus on immigrant-origin populations, and not all immigrant-serving organizations label themselves as ethnoracial. Additionally, the NTEE code developed specifically for organizations that provide immigrant/ethnic services (code P84) is not widely used by immigrant nonprofits that also engage in other activities. As an alternative to such codes, some researchers use computer keyword searches for particular labels or strings of words in organizational names, such as Mexican or Korean (Chan 2014; Cortés 1998), or they identify organizations by the ethnic-specific surnames of board members and other leaders (Hung 2007) or by board members’ country of birth (Vermeulen 2006). Such strategies are entirely reasonable but can lead to significant omissions or erroneous inclusion of nonimmigrant organizations.

Another approach, albeit far more tedious and labor intensive, is to hand-code hundreds or thousands of organizations in official databases to identify immigrant-serving organizations. Using a combination of NTEE codes, organizational names, and information collected during fieldwork, we individually coded immigrant organizations after we confirmed (via websites, directories, and interviews) that the organization had a mission or activities that addressed the aspirations or problems of people with immigrant origins (de Graauw 2016; Gleeson and Bloemraad 2012). Other scholars employ similar intensive coding strategies but categorize organizations by the proportion of a group’s clientele or membership that is foreign-born (Cordero-Guzmán 2005; de Graauw 2016). Researchers can also consider organizational activities: for example, whether programming, meetings, and social and recreational activities are offered or conducted in multiple languages.

Given the limits of existing databases, such lists can be supplemented by other sources of information such as directories of social and human services and historically specialized “ethnic” phone directories that listed community groups. In their ongoing research, Els de Graauw and Erwin de Leon are triangulating various directories—including those maintained by immigrant organizations themselves, city officials whose purpose is to serve immigrant communities, and local foundations that invest in immigrant communities—to identify immigrant-serving nonprofits in New York City and to determine how visible these organizations are to government and philanthropic leaders.

Beyond Simple Counts: Comprehensive Organizational Data and Civic (In)visibility

Administrative data frequently suffer from a lack of depth about organizational features important to nonprofit scholars. To collect more comprehensive data, researchers can draw on formal organizational lists to create a list of all immigrant organizations in a particular place, then conduct an original survey of (a sample of) these organizations (e.g., de Graauw 2016). Such a survey can ask about budgets, services, clientele, workforce, membership structure, advocacy activities, and so forth. This method is more time-consuming than relying on existing datasets and requires diligence in securing a strong response rate to the survey, but it offers the important advantage of collecting data unavailable in formal registries.

A persistent challenge—in using either administrative or survey data—is how to define and confirm the prevalence of immigrant-focused activities and programming. Organizations can be very entrepreneurial in attracting new funding streams, without fundamentally reorienting their leadership or building lasting structures that make them more immigrant-friendly. A low- or no-cost health clinic might translate some materials into immigrant languages or employ a bilingual nurse who works a few hours a week but otherwise conducts business as usual. Conversely, some mainstream organizations may go to great lengths to mask the extent to which they serve immigrant populations to avoid criticism from risk-averse funders or xenophobic critics. Finally, it can be difficult to identify whether organizations serve multiple immigrant generations. An existential (and empirical) question arises as to whether later-generation organizations are appropriately considered “immigrant,” or whether they should be conceptualized differently, such as an ethnoracial organization or a mainstream organization. A handful of scholars use ethnography to probe the day-to-day work environment, decision making, and conflicts within immigrant organizations that serve multiple generations (e.g., Chung 2007). Providing important insight that complements large-N data studies, ethnographies reveal the challenge of categorizing individuals and organizations as immigrant or not. At the same time, as with ethnographic work of all sorts, researchers must weigh the trade-off between the depth of knowledge gained versus the breadth of knowledge lost when studying only a few organizations.

Between a strategy of trying to study all organizations or just a handful, some researchers use field methods—including semi-structured interviews with community members and some ethnography—to identify “publicly present” or “civically visible” immigrant organizations (Chaudhary and Guarnizo 2016; Gleeson and Bloemraad 2012). In one study, researchers identified “all groups known to local officials, to ethnic or mainstream media, or to key leaders and volunteers working in the nonprofit sector” as a measure of civic visibility (Gleeson and Bloemraad 2012:348; Bloemraad and Gleeson 2012). The goal is to measure the extent to which decision makers or others outside the immigrant community recognize organizations run by and catering to immigrant residents. A reputational tally was created using semi-structured interviews that asked officials to list all the community organizations in their city, with subsequent probing for organizational sector (e.g., housing, recreation) and demographic groups. In another study, researchers examined what they term “socio-political legitimacy” by focusing on the perspectives of elected and nonelected local officials who make decisions about policy, resources, and services (Gnes and Vermeulen 2018).13 Yet another approach analyzes how mainstream media report on local immigrant communities, including their coverage of organizations (Bloemraad, de Graauw, and Hamlin 2015).

When using reputational data, scholars recognize that journalists and decision makers have imperfect information and do not always have good recall, capturing only a slice of immigrant organizational life. They argue, however, that this civic visibility, or lack thereof, is in itself telling. Understanding which organizations are known beyond the immigrant community carries consequences for organizational survival as well as political decision making, resource allocation, and public attitudes about immigration. For example, in examining immigrant and ethnic organizations in Amsterdam, researchers found that the degree to which organizations are known and legitimate in the eyes of the immigrant constituency and external actors is more important to organizational survival than neighborhood context (Vermeulen, Minkoff, and van der Meer 2016). A drawback, however, is that field-based techniques are time-consuming and often temporally and geographically restricted. Tellingly, almost all hand-coded and field-based research on immigrant organizations focuses on one city or metropolitan region within a manageable but relatively narrow window of time.

Measuring Civic (In)equality

As outlined earlier, we conceptualize civic inequality at the meso level as disparities in the number, density, breadth, capacity, and visibility of organized groups in a community. Making claims about inequality requires some standardized measure of comparison. Against whom or what should immigrant nonprofits be measured?

A straightforward approach compares organizations serving immigrants to those serving the native-born or overall population. Researchers can also compare communities based on national origin, religious affiliation, racial minority background, or some other demographic characteristic.14 One technique is to create a density score, calculating the number of immigrant nonprofit organizations identified in an administrative dataset per 1,000 immigrants in the population, and then to compare that figure to the density of all nonprofits in the general population. Using this approach, we found that around 2006, there were 5.5 registered nonprofit organizations per 1,000 city residents in San Francisco, but only 2.2 immigrant organizations per 1,000 foreign-born residents (de Graauw et al. 2013:99). We also found a roughly two-to-one ratio in nonprofit density for all city residents compared to foreign-born residents in San Jose and two nearby Silicon Valley suburbs.

Alternatively, the proportion of all organizations that serve immigrants (or a particular immigrant community) within the full universe of nonprofit organizations can be compared to immigrants’ share of the total population. Dividing one by the other generates a civic inequality index where a value close to one suggests that a group’s demographic presence in an area is on par with its share of registered nonprofits. Values close to zero suggest significant underrepresentation. Values above one indicate a share of nonprofit organizations larger than a community’s demographic weight. Such a proportionality measure can be extended to consider the number of grants or the dollar amount of public or foundation funding that go to immigrant organizations as a proportion of total nonprofit grants or other funding (de Graauw 2016; de Graauw et al. 2013).

Rather than compile aggregate counts, scholars can also investigate the size of nonprofit organizations, as measured by the number of members, clients, staff, or volunteers, or by the financial resources and activities of the group. Such data provide information on whether immigrant organizations have fewer financial and human resources than mainstream nonprofits. Researchers can further investigate the range of organizational types in a community, to see whether nonprofit activity is concentrated in a particular domain (e.g., religious organizations vs. arts organizations vs. sports organizations). One can also investigate the range of nonprofit activity, for example to identify groups that focus on services or advocacy, or groups whose programming is oriented to more domestic, homeland/transnational, or international activities (see Chan 2014; Chaudhary and Guarnizo 2016). The breadth of organizational types can be a measure of whether an immigrant community is institutionally complete (e.g., Bloemraad 2005; Breton 1964; Chaudhary and Guarnizo 2016). When these measures—be it numbers, funding, domain of activity, or something else—differ substantially for immigrant communities as compared to a majority or native-born reference group, civic inequality may exist.

Why Civic (In)equality Matters for Immigrants

Although little research has examined civic (in)equality in immigrant communities, what has been done suggests that the current number and density of immigrant nonprofit organizations lags compared to demographic benchmarks. Research also shows that the geographic dispersal of these organizations does not necessarily match immigrant settlement patterns, with suburban and rural areas contending with fewer nonprofit resources (de Graauw et al. 2013; Joassart-Marcelli 2013; Roth, Gonzales, and Lesniewski 2015; Truelove 2000).

But why should we be concerned if there are fewer immigrant organizations or if there is less public funding for them? Mainstream nonprofit organizations may serve immigrants well. As we noted earlier, some observers worry that excessive immigrant or ethnic organizing self-segregates a community and impedes immigrant integration. Yet the general literature on the third sector, interest groups, and social movements suggests that civic inequality diminishes democratic voice and service provision, and it reduces access to sports, recreation, and the arts, or to other organizations set up to bring together people who share an affinity or interests. It is thus logical to presume that immigrants and immigrant communities bear negative consequences from civic inequality, with broader implications for how democracy functions in society. Surprisingly, however, there is very little empirical research probing the possible harms or repercussions of civic inequality for immigrant communities, in large part because immigrant organizations have featured so little in scholarship to date. We end the chapter by considering some of those repercussions, as well as avenues for future research.

Underserved: The Hardships of Limited Nonprofit Service Providers

A few studies suggest that in the absence of immigrant organizations, foreign-born residents access fewer human and social services. Immigrants in Silicon Valley, for example, were estimated to have two to four times the social service needs of native-born residents, but they are about half as likely to receive help (Santa Clara County Office of Human Relations 2000). To the extent that immigrants in this region need to turn to nonprofits for help, those that primarily serve communities of color—almost all of which are largely immigrant-serving organizations—had smaller staffs and 40 percent less income than other nonprofits (LaFrance Associates 2005). Similarly, examining Chicago suburbs with substantial Mexican-origin populations, Benjamin J. Roth and his colleagues (2015) found that immigrant organizations were more likely to report low revenues and complain of insufficient funding compared to mainstream nonprofit service providers.

Smaller staff and limited funding could be a reflection of less effective organizations. However, there is reason to believe that the problem instead lies with the lion’s share of resources going to mainstream organizations that are still not adequately addressing immigrant needs. In the Chicago study, despite low revenue, immigrant organizations had a larger percentage of bilingual staff (paid and volunteer), and they offered more immigrant-specific services such as English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, cultural programming, or legal services like citizenship assistance than mainstream organizations (Roth et al. 2015). Similarly, the history of Southeast Asian refugee resettlement in North America in the late 1970s and 1980s suggests that mainstream organizations were ill-equipped to help these newcomers, even when an organization had experience serving displaced people. As a result, earlier-arrived compatriots or citizen co-ethnics established Southeast Asian mutual aid associations and ethnic-specific organizations, often helped by federal government resources, to offer targeted, language-accessible and culturally appropriate services (Bloemraad 2006; Hein 1997).15

An area for future research is to evaluate the impact of nonprofit service provision on immigrant integration over time. Based on the refugee resettlement experience, immigrant organizations may be essential early on, providing immigrants with a safe space for companionship, support, and immigrant-tailored services. We know less about long-term effects—that is, whether immigrants living in nonprofit-rich environments are more successful in their economic, social, and political incorporation. Alternatively, immigrant organizations may be effective in the short term but could isolate immigrants from mainstream society over the long term. Adjudicating between these possibilities will require both large-N empirical studies that map variation in the universe of immigrant civil society, as well as in-depth qualitative research that pinpoints the mechanisms by which organizations affect immigrant populations.

Jobs and Leadership: Nonprofits as Employers and Schools of Civic Learning

Third sector scholarship considers nonprofits as job generators. In the United States in 2012, the nonprofit sector offered paid work to 11.4 million people, or 10.3 percent of private sector workers (Friesenhahn 2016). Research in immigrant communities also identifies the third sector as a source of employment and economic mobility, especially for those who face barriers entering the general labor market because of limited majority language skills, foreign credentials not recognized in the host country, or employment discrimination (Bauder and Jayaraman 2014; Bloemraad 2006). Immigrant advocacy organizations have even become a source of employment for young undocumented immigrants, although differences in job access are observed across nationality groups and types of nonprofits (e.g., Cho 2017). Thus, in line with existing scholarship, the nonprofit sector offers employment and perhaps upward mobility for the foreign born, but the particular legal situation of immigrants—especially the lack of official employment rights—limits who can find jobs in the third sector, and whether they can be salaried with benefits or must resort to contract or stipend positions that forestall employer-sponsored benefits such as health care. Scholars need to develop more nuanced ways of thinking about nonprofit sector employment, especially for undocumented immigrants whose work is legally and structurally precarious.

Beyond employment, nonprofit organizations have also long been identified in the literature as potential “schools” that teach leadership and civic skills, via either traditional civic associations (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995) or change-oriented social movement organizations (McAdam 1988). There are good reasons to believe that third sector groups can play a similar role for immigrants, especially those who might be unfamiliar with the political and civic norms of the host country, and who feel intimidated to speak out because of linguistic and educational barriers. For example, in Kathleen Coll’s (2010) study of immigrant Latinas in San Francisco, participation in a feminist workers’ organization led to greater claims-making and sense of political efficacy, even among undocumented women. Studying the impact of grassroots youth organizing groups, Veronica Terriquez (2012) reports increased civic and political engagement among immigrant-origin alumni of these groups, leading her to draw parallels between the youth organizations and civil rights groups from the 1960s. And de Graauw (2016) discusses how many elected and nonelected city officials with immigrant backgrounds in San Francisco started their careers in the city’s immigrant nonprofit sector, suggesting that immigrant nonprofits can serve as valuable training grounds and pipelines for immigrant and minority government leaders. Taking organizational inequality seriously raises another hypothesis to explain gaps in foreign- and native-born associationalism: if fewer immigrant-oriented organizations exist in a region, the chances for employment, leadership development, and acquisition of civic skills are reduced.

This is not to say that third sector organizations are a panacea to tackling inequalities in civic engagement. Studying Latinx janitors who are members of what she labels a “social movement union,” Terriquez (2011) finds that impacts can be unequal and differentiated. Comparing union participants and nonparticipants, she finds no differences in parent workers’ engagement with their children’s schools in routine activities like volunteering or attending a parent-teacher organization meeting. However, union participation does lead to more change-oriented activities, such as mobilizing others to attend public meetings and challenging school officials to change institutional practices. In these cases, union training in public speaking, step-by-step organizing, and negotiation provide parents with the skills and confidence to engage school authorities.

Negative public discourse that stigmatizes immigrants’ service use can also hinder nonprofits’ ability to act as “civic schools” or leverage service provision as a mobilizing tool. Melanie Jones Gast and Dina G. Okamoto (2016) did fieldwork in two nonprofits that combine service provision and advocacy. The organizations paired service provision with requests for participation in political education and advocacy work. This led some women to feel that they could ask for help only if they paid the organization back with volunteer hours. Although a reciprocity norm may also exist in nonprofits catering to citizen clients, Gast and Okamoto argue that the feeling of obligation may be amplified for immigrants because of a national public discourse that stigmatizes immigrants’ welfare use and labels the undocumented as particularly undeserving. Some immigrant mothers became reluctant to ask for help, even when their families desperately needed assistance, because they had little time to volunteer or they wanted to avoid public engagement out of fear of immigration enforcement. Here, again, immigrant background is salient to understanding the extent to which third sector groups can act as civic schools for immigrants.

Advocacy and Civic Voice

On balance, existing scholarship suggests that third sector organizations have positive effects on individual civic and political engagement, though researchers face a problem of causal identification: the types of individuals who join or participate in those organizations may just be more civically and politically minded to begin with. Theoretically, there is good reason to believe that positive civic effects also apply to immigrants, and a small number of studies support this argument empirically. Fennema and Tillie (1999) argue that immigrant communities with a denser civic infrastructure of organizations and overlapping board memberships experience increased solidarity, which in turn increases the level of mainstream political participation and generalized trust exhibited by immigrants. However, legal status constraints erect high hurdles for immigrants, and anti-immigrant discourses may do so, too.

A separate question is whether third sector organizations, as independent actors, can produce far-reaching structural social change. In the case of formal nonprofits, third sector scholarship tends to be pessimistic about advocacy and what nonprofits can achieve in politics, often concluding that they do little (e.g., Andrews and Edwards 2004; Berry and Arons 2003; Taylor, Craig, and Wilkinson 2002). In the United States, nonprofits with 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status are limited in the amount of lobbying they can do, and they are barred from partisan electioneering. Nonprofits operating with few staff and on shoestring budgets may not have the resources to invest in advocacy, while those with government contracts may be fearful that their advocacy bites the hand that feeds them. Immigrant organizations have the added challenge of advocating for marginalized and vulnerable communities against a backdrop of increasingly aggressive immigration enforcement and a highly politicized environment with fractured public support for immigrant rights.

Still, given many immigrants’ exclusion from formal politics, nonprofits may play a critical role in civic and political voice for immigrant communities. Recent research shows that immigrant nonprofits have secured important advances in immigrant rights policies (de Graauw 2015, 2016). Not only do they articulate the needs of immigrants often shut out of formal politics because they are denied a vote, but once policies are enacted, they can be especially effective in pushing government bureaucracies to implement new policies, transforming rights and services on the books into reality on the ground. More broadly, social movement organizations in the United States have worked hard to keep the dream of comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, on the political agenda and in the media spotlight. “DREAMer” organizations—immigrant rights groups often led by young undocumented or immigrant-origin activists—are credited with pushing former president Barack Obama to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in 2012, temporarily shielding undocumented youth from deportation and providing work authorization (Nicholls 2013).

Advocacy organizations that speak out on behalf of marginalized communities have, in past scholarship, been criticized for primarily articulating the interests of the most privileged in a minority community, such as white women’s grievances in the feminist movement, rather than intersectional identities and issues (Strolovitch 2007). Scholars studying the pro-immigrant movement have similarly critiqued organizations and leaders for initially privileging the most sympathetic in the undocumented community, highlighting the plight of those who came to the United States as children and who achieved extraordinary success in school or selfless service in the community and military (Yukich 2013). More recently, some observers underscore the broad, intersectional approach to social justice embraced by young immigrant activists who seek coalitions across legal status, sexual identity, race, and class backgrounds (Terriquez 2015). Thus far, the literature on interest and advocacy groups in political science and social movements scholarship has largely ignored immigrants and migration issues. Future research needs to investigate whether existing concepts prevalent in these fields, such as framing, political opportunity structure, and resource mobilization, apply equally to noncitizens, especially those who are formally barred from key rights, who may be seen as illegitimate by voters and decision makers, and who are at risk of deportation.

In short, third sector scholarship needs to take better account of the diverse communities and constituents that nonprofit organizations serve and represent. One core group are immigrants, who may face unique challenges due to precarious documentation status or lack of citizenship, or other reasons linked to migration, such as language barriers or lack of experience with local civic norms. Immigrants may also be a source of innovation for the third sector, as they bring with them unique associational traditions from their country of origin and possible transnational orientations. We also spotlight the way that immigration law and either inclusive pro-immigrant or exclusionary anti-immigrant policies help scholars understand patterns of civic inequality, whereby some immigrant communities remain underrepresented and underserved by third sector organizations across a range of arenas. This civic inequality carries significant implications for resource distribution, employment mobility, and civic voice. Unaddressed, disparities can become solidified into patterns of durable civic stratification with negative implications for immigrants’ long-term societal integration and the overall health of democratic societies.