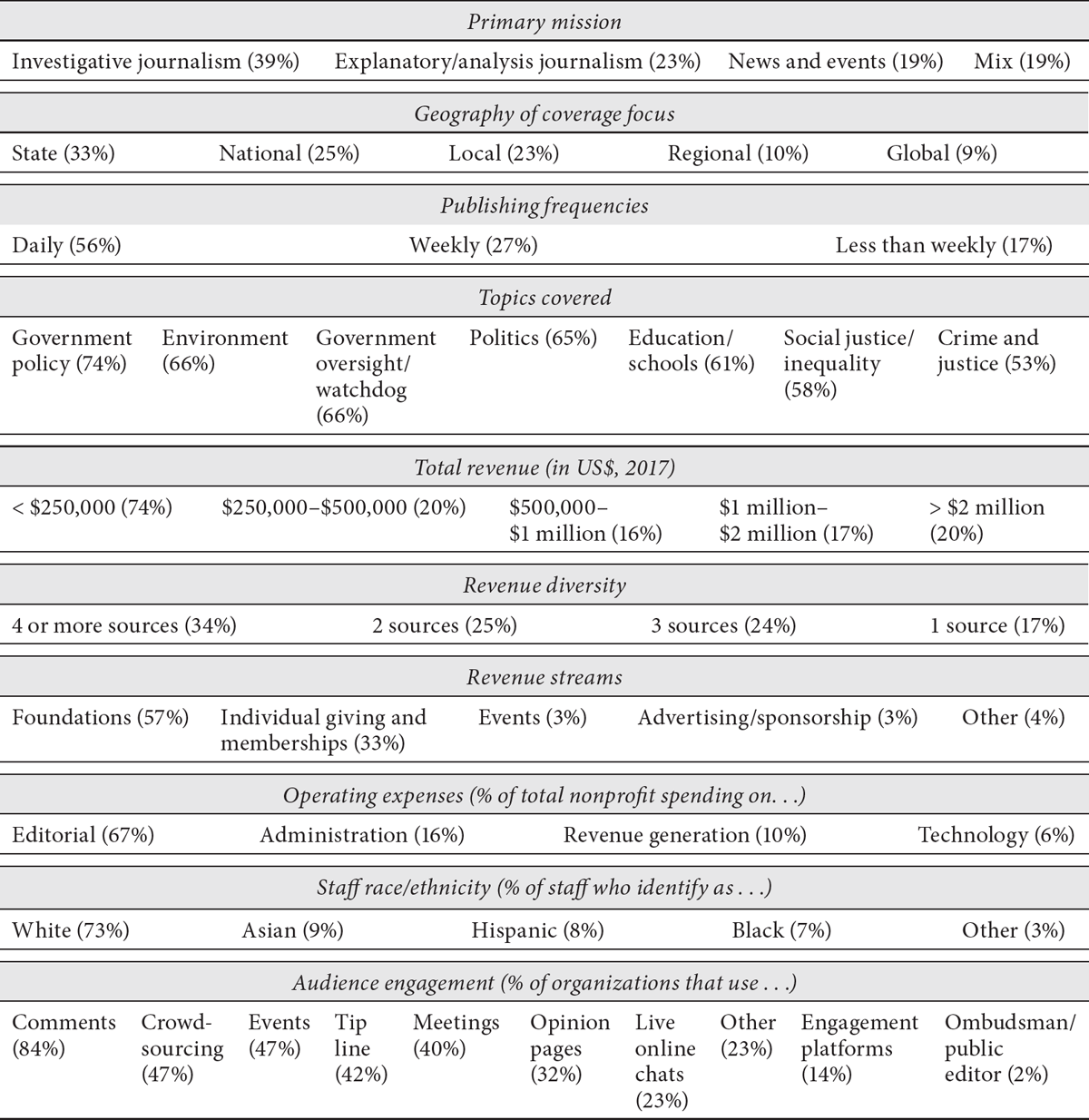

Table 22.1 Self-stated dimensions of nonprofit news organizations

Source: Adapted from McLellan and Holcomb 2018.

ADVOCATING FOR WHAT?

The Nonprofit Press and Models of the Public

Mike Ananny

IT MAY SEEM STRANGE TO PLACE a chapter on journalism in a handbook section focused on advocacy. Especially in American press traditions—steeped in tropes of objectivity, the disinterested pursuit of truth, and a faith in journalism’s ability to separate facts and values—journalists are supposed to be anything but advocates. In the popular imagination and many journalists’ self-conceptions, the press is independent. It doesn’t advocate for anything. It simply investigates, observes, describes, and disseminates information, disclaiming investment in any particular outcome.

There are at least three problems with this narrative. First, journalists do have interests. Publishers, editors, and reporters carry with them their own ideas about what’s right and wrong, what counts as good evidence, and what’s relevant and newsworthy. Decades of scholarship in communication and sociology have traced the rituals, routines, habits, and assumptions driving journalism. Second, the press is never truly independent. Historically, it has always been intertwined with market expectations, government sources, editorial boards, audience demands, new technologies, and cultural norms. Some journalists and armchair political theorists may celebrate the press as a disinterested arbiter of timeless notions of truth, but research and journalists’ own self-reflections suggest otherwise. Press freedom has always been a reflection of each era’s social, political, economic, and technological forces. At different times in history, the press has been closer to or further away from markets, states, audiences, and technologies, but the press has never been a completely autonomous institution. Finally, the press can advocate for something: the public. If the idealized press is interested in anything, it is the public interest: issues and challenges that need to be understood and acted on collectively, separate from whatever markets and states might say. In eras of deep partisan division, technological upheaval, and economic crisis, it may sound quaint to assert this kind of public interest, but if the press should advocate for anything, it is common goods and a civic life beyond whatever a given era commodifies or a particular government defines as a state interest (Ananny 2018).

Exactly how the press defines and pursues this public interest is a perennial debate. What motivates journalists, how they act, where news circulates, which outcomes journalism produces, and how owners, audiences, and states direct their resources—these all constantly shift. Depending on your perspective, they add up to a press that is broken or well tuned. But historical and structural patterns can help us better understand how each era’s press advocates, and how notions of the public interest both emerge from and challenge assumptions about press advocacy. This chapter considers how one domain of journalism—the nonprofit press—advocates for the public interest, by navigating and often explicitly opposing the commercial, market-driven forces that dominate American journalism. Indeed, the continued existence of the nonprofit press shows that free markets are not the same thing as a free press. The nonprofit press imagines—and advocates for—its own ideal of press freedom, its own image of the public interest.

In his foundational study of media concentration and the influence of ownership, C. Edwin Baker (2007) argued that different democracies need different types of media. This deceptively simple claim questioned the idea that the media are a single institutional entity serving a shared and uniform ideal of democracy. It reframed the question of the media–democracy relationship as a two-sided conversation between organizational and institutional forces that configure the media—who owns the media, how journalists practice, which stories emerge, how audiences interpret and act on the news—and normative evaluations of the self-governance that such forces make possible. In characterizing both ideals of democracy and operations of the media as contingent and contestable, Baker highlights the need to consider simultaneously two dimensions of the press: (1) the institutional dynamics that give rise to news production, circulation, and interpretation, and (2) the normative criteria by which to judge those dynamics, take stock of their public significance, and potentially demand new configurations of the press and democracy.

Journalism scholars tend to organize the study of news into three broad themes. The first focuses on the production of news:

• the often unstated, institutionally situated nature of journalistic practices and values, and journalists’ roles as gatekeepers of what qualifies as newsworthy people, places, and events;

• the acquisition of skills and attitudes through curricula, appeals to public service, and norms of professionalization; the role of organizational form, ownership models, and labor markets in determining which events and topics are covered and defined as news; and

• the regulatory forces and legal regimes that constrain and sanction journalists and influence their senses of professional autonomy both real and imagined (Berkowitz 1992; Boczkowski 2009; Carlson 2015a; Christin forthcoming; Gans 1979; Schudson 2000; Tuchman 1978).

The second broad area of scholarship focuses on audiences’ relationships to news:

• how news helps people learn about people and events, change or retrench their opinions, and make and defend identities, and how it drives some actions over others;

• differences among news audiences, with some consumers perceived as more commercially or politically valuable than others;

• advertisers’ roles as intermediaries between journalists and audiences, with the power to influence the kind of news journalists see as commercially viable and publishers’ obligations to distinguish between the kind of news they want to produce and the kind of news advertisers want to support; and

• increasingly, the role that “active audiences” and platform intermediaries play in news: interpreting news differently, driving aspects of news production and circulation, and demanding from journalists and advertisers alike changes aligned with their (dis)pleasure with the news landscapes that have been created for them (Bell and Owen 2017; Braun and Gillespie 2011; Napoli 2011; Prior 2007; Stroud 2011; Wahl-Jorgensen 2007).

Finally, recognizing that the press is the only commercial institutional explicitly mentioned in many constitutions, journalism scholarship asks normative questions about the following:

• the role that journalism and news plays—or should play—in creating the imagined communities of democratic societies;

• the ideological orientations of supposedly autonomous journalists with the power to shape news narratives;

• the kinds of issues that journalists have historically seen as core or peripheral to their democratic roles, and the kinds of people, places, or events that are seen as conventional versus taboo; and

• the underlying conceptions of democracy, freedom, and speech that drive many of the press’s technological infrastructures, regulatory and legal regimes, and professional cultures (Ananny 2018; Anderson 1983; Baker 1998; Christians et al. 2009; Curran and Seaton 2009; Zelizer 2017).

How might we trace through nonprofit news the relationships between journalism’s practices, audiences’ relationships to news, and the press’s institutional power to envision and instrumentally construct self-governing collectives? How do these forces appear in historical and contemporary approaches to press funding, with particular focus on how nonprofit news is supported? Most broadly, how do different types of publics arise from different types of nonprofit funding models?

This chapter offers ways to think about these questions. I suggest that although they have roots in longstanding sociologies of journalism and the news, these questions can be posed anew for a contemporary era in which the press lives not in any single set of news organizations, professional communities, or information genres; rather, it is distributed across a fragmented, loosely coordinated set of sociotechnical conditions that structure news production, circulation, and interpretation. These conditions—which I call the “networked press”—depend not only on journalistic judgment and editorial standards but also on increasingly intertwined relationships with technology companies, algorithmic processes, and the somewhat limited and unstable patterns of online audiences.

In this chapter, I focus on how the networked press is funded and argue that its funding dynamics lead to different types of publics. After historically situating networked press funding dynamics, I sketch a typology that relates these dynamics to types of publics and conclude with some thoughts on how to further investigate the normative patterns of public making that underlie the networked press. Recalling my earlier assertion that the nonprofit press advocates for a particular vision of the public interest and Baker’s call to think about how different types of democracy need different types of media, I show how the nonprofit press both depends on and gives rise to particular types of publics.

U.S. Journalism’s Public Responsibilities as Organizational Form and Ownership

U.S. news organizations’ understandings of their public responsibilities have always been intertwined with their organizational forms and ownership models. Starting in the Revolutionary War era, state actors and government officials openly sponsored particular printers. These patron-backed printers dominated markets with explicitly partisan messages that made no pretense of editorial fairness, content neutrality, or what would eventually be called journalistic objectivity. Newspapers were party instruments; the jobs of writer, editor, and publisher were explicitly combined (the role of reporter not yet having been invented); and publication owners were rewarded with generous government contracts precisely because they could be relied on to print material that helped party interests (John 1998, 2012; Schudson 1998).

In the early years of the Republic, before the idea of press freedom had undergone judicial review, state officials routinely vetted printers’ publications, speech perceived as treasonous was banned, and the government’s censorship power was codified in legislation (although the Alien and Sedition Acts were subsequently overturned) (Halperin 2016). The modern notion of press freedom did not yet exist in principle, let alone practice. The institutional press was synonymous with the printing and distribution of publishers’ opinions that often simply echoed those of political parties.

Although this partisan-fueled, state-funded, “party press” era of U.S. news continued through the nineteenth century, it gradually shifted form. Newspapers began to earn revenue through a mix of advertising revenue, newsstand sales, subscriptions, and political patronage. The foundations of the “penny press” era were laid in the 1840s—spurred on by a mix of low-cost printing, population growth, increased literacy rates in multiple languages, and larger urban populations (Schiller 1979; Schudson 1978)—yet many newspapers kept their political affiliations and sponsorships. By 1870, “Republican papers accounted for 54% of all metropolitan dailies and gathered 43% of the total circulation in these cities. Democratic papers comprised 33% of daily newspapers and 31% of circulation” (Hamilton 2006:37). However, as marketplace models rewarded newspapers that appealed to broader audiences and increasingly apolitical advertisers, journalistic independence emerged not from ideals but economic necessity. Rather than functioning as party mouthpieces, publishers like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst discovered that they could refashion newspapers into vehicles for their own images of the public, using the social, technological, and economic underpinnings of the penny press to engage in a kind of editorial trade-off or utilitarian moralism. They could on one hand cheaply produce apolitical news that audiences wanted to read and advertisers wanted to sponsor (murders, love affairs, scandals) with images that attracted attention (Barnhurst and Nerone 2001), and on the other use the proceeds to fund the journalism that they wanted to produce—that they thought audiences needed to be publics. The role of the reporter and the genre of the interview were invented as ways for news organizations to show their audiences and advertising markets that the news was not coming from partisan sponsorship or publishers with agendas but from independent, fact-driven research about the societies within which audiences lived (Schudson 1995). A commercial press emerged from this idea that news was about people’s lives and that newspapers should reflect what printers, journalists, and publishers understood to be public interests (Nerone 2015). The foundations of the contemporary press thus began to appear: by 1900, “independent newspapers accounted for 47% of metropolitan dailies” (Hamilton 2006:38). Muckrakers and investigative reporters like Ida B. Wells, Upton Sinclair, and Nellie Bly mixed social justice missions with gripping narrative styles (Protess et al. 1991). In 1922, Walter Lippmann published his seminal book Public Opinion, in which he lamented how easily the public could be manipulated, coined the word stereotype, and called for a “scientization of journalism” (Hallin 1985). Lippmann’s vision focused the press on independently reporting objective, verifiable facts that could fight government censorship, public relations spin, market subservience, and audiences’ tendencies toward passionate, moblike rule (Butsch 2008). Indeed, this era saw the beginning of modern journalism’s belief that both its financial health and its moral mission lie in the belief of objectivity as “a faith in ‘facts,’ and distrust of ‘values’ and a commitment to their segregation” (Schudson 1978:6).

In a short period of time, the press showed how it could earn financial support not only through state sponsorship and partisan control but also through a variety of alternative means: commercial models, the patronage of wealthy individuals, social justice appeals, engaging and sensationalist narratives, and a commitment to professionalized objectivity. The twentieth century would see an attendant growth of ownership models with commensurate and diverse understandings of editorial judgment and public service. For example, private news companies headed by families (the most common type of news organizations) were often closely affiliated with the public priorities of elite policy makers and industry leaders. Publicly traded companies, in contrast, had fiduciary responsibilities to stock owners and marketplace metrics of success. Foundation-funded trusts and charities supported both short-term reporting projects and long-term institutional investments that aligned with their strategic interests. Nonprofit news corporations aimed for marketplace success, not to pay dividends or build financial dominance but rather for the purpose of reinvesting into coverage and attracting journalists driven by social justice missions. Employee-owned cooperatives arose to give journalists more control over not only their daily work routines and editorial decisions but also what Murdock (1982:122) calls the “allocative” decisions about policy, strategy, hiring, and financing that structure the conditions under which journalists work (Bezanson 2003; Bradlee 1975; Chomsky 2006; Graham 1998; Levy and Picard 2012; Picard and van Weezel 2008; Villalonga and Amit 2006). Indeed, the dominant model of press freedom began to be seen as journalism’s ability, through its financial and ownership models, to separate itself from anything that interfered with its vision of public life.

As Baker suggested, different visions of public life required different types of media—and thus different types of press freedom (Ananny 2018). By the 1920s, many of the economic dimensions of contemporary debates over press freedom and public life had become evident. Several disparate perspectives and motivations that arose in this period persist today. For example, if journalists think that healthy public life requires partisan contests and that their mission is to surface different political positions, they may see anything that interferes with the partisan press as an attack on (their version of) press freedom. If they think that a free press is akin to free markets, they may see journalism’s commercial successes and failures as indicative of the press’s ability to support a marketplace of ideas. If journalists eschew partisanship and commercialism in favor of social justice missions, they may perceive a need for financial investments from civil society actors (e.g., foundations and wealthy patrons) who share their progressive agendas and can insulate them from parties and markets. If they see audience preferences and attention economies as their primary channels, they will seek access to the media and genres that will attract attention and render compelling narratives (e.g., akin to the images, stunts, and investigations that helped nineteenth-century news earn mass appeal). Lastly, if they see their profession grounded in objectivity, they will strive for separation from parties, audiences, markets, social agendas, and sensationalism—a distance from the worlds they report on that lets them separate facts and values.

This latter focus on distancing journalists from the social worlds they aimed to describe manifested throughout the twentieth century in a set of increasingly intricate “rituals of objectivity” (Tuchman 1978). These practices rested on the belief that “the news” existed independent of journalists’ reporting. “Good journalism” (Gardner, Csikszentmihalyi, and Damon 2002) manifested as journalists’ ability to accurately report the words of “bureaucratically credible sources” stationed at predictable locations (Tuchman 1978). They reported on scientific public opinion polls (Herbst 1995) and analyzed documents from official sources (Neff 2015). They scoped their stories within newspapers’ thematic sections and avoided thinking too much about a large and abstract public they could never directly know (Darnton 1975). They subtly tried to reflect the wishes of their publishers (Beam 1993; Chomsky 2006; Wagner and Collins 2014) while claiming independence to choose their sources and defend their ledes (Murdock 1977). They learned how to inflect their writing with their own perspectives through subtle word choices that showed sophisticated readers that they were more than simply disinterested scribes (Glasser and Ettema 1993; Lipari 1996). Professional journalists tried to be both deeply embedded within social worlds and independent of them.

By the late twentieth century, several perennial questions of the press and press freedom had been posed: How is a news organization’s image and execution of its public mission influenced by its owners? How does its organizational form influence how it understands its audience? Where does its revenue come from and how does this influence news production and circulation?

New Nonprofit Actors Broaden Journalism’s Institutional Field and Challenge Public Dynamics

This history has often been told though studies of individual news organizations, particular publishers, or case studies of events. Scholars traced the behaviors of canonical, often predictable sources of news work, with little appreciation for how journalism operates as an institution whose “loosely coupled arrays of standardized elements” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991:14) combine to both reveal and shape the conditions under which news is produced, circulated, and interpreted. A full review of these neo-institutional and field-based understandings of journalism is beyond the scope of this chapter, but more recent scholars have conceptualized contemporary journalism not as a monolithic practice but as manifold field-level, multi-organizational processes that live across a set of human and computational actors that, together, create news and its public meanings (Ananny 2014; Benson 2006; Benson and Neveu 2005; Boczkowski 2004; Carlson 2015a).

This field increasingly contains a distinct space of nonprofit journalism. It seems to have distinct normative logics that explicitly reject the commercial nature of mainstream journalism. These logics appear not only in how “nonprofit journalists” (Konieczna and Powers 2017) work but also in a new array of nonprofit and foundation-funded organizations that have arisen to support nonprofit news production (Benson 2017). Their goals are premised on assumptions about how previous news markets have failed journalists, audiences, and ideals of democratic self-governance (Konieczna 2018).

This field is beginning to take stable shape, as described in Konieczna (2018) and summarized in Table 22.1’s overview of a 2018 study of the U.S. nonprofit journalism field by the Institute for Nonprofit News (McLellan and Holcomb 2018).1

Although this snapshot of the field has methodological limitations—self-reports, no longitudinal picture, a lack of cross-tab information that would provide greater specificity—it sketches dimensions along which the field is progressing. Nonprofit news organizations tend to focus on one or two topics, often centered on investigative projects that they see as core to a public interest mission. Nonprofit news organizations are also relatively young, with the median organization eight years old and nearly half the organizations founded between 2009 and 2011. Foundations provide the bulk of revenue to nonprofit news organizations, with most of this money used for editorial expenses. Most staff are white, suggesting that the field of nonprofit news lacks racial and ethnic diversity, much like its commercial, for-profit counterparts (American Society of Newspaper Editors 2017). Finally, unlike their for-profit counterparts—which have increasingly moved audience engagement to social media platforms and discontinued their site comments—nonprofit news organizations seem to keep audiences close by hosting comments and fund-raising through crowdsourcing campaigns on their own websites, running community events and meetings, and holding online chats.

Nonprofit news organizations rely heavily on foundations and are often offshoots of other nonprofit organizations. The Omidyar Foundation, the Sandler Family Foundation, the Kaiser Family Foundation, the Nieman Foundation, and the Columbia Journalism School have all founded news organizations explicitly designed to be freer from commercial revenue pressures than for-profit counterparts. They claim that their funding models, ownership structures, and organizational forms let them pursue public missions and make editorial judgments that are more flexible and responsive to fast-changing conditions of online news. Similarly, though not publishers per se, nonprofit research organizations like the Institute for Nonprofit News, the Pew Research Center, the Knight Foundation, the Reynolds Journalism Institute, and Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism and Brown Institute for Media Innovation have arisen as powerful nonprofit journalistic actors. They fund reporting projects, develop new experimental digital tools, define best practices, disseminate research, sponsor academics, convene public forums, publicly pressure both news organizations and technology companies, and heavily influence what it means to be a public, mission-driven news organization (Lewis 2011).

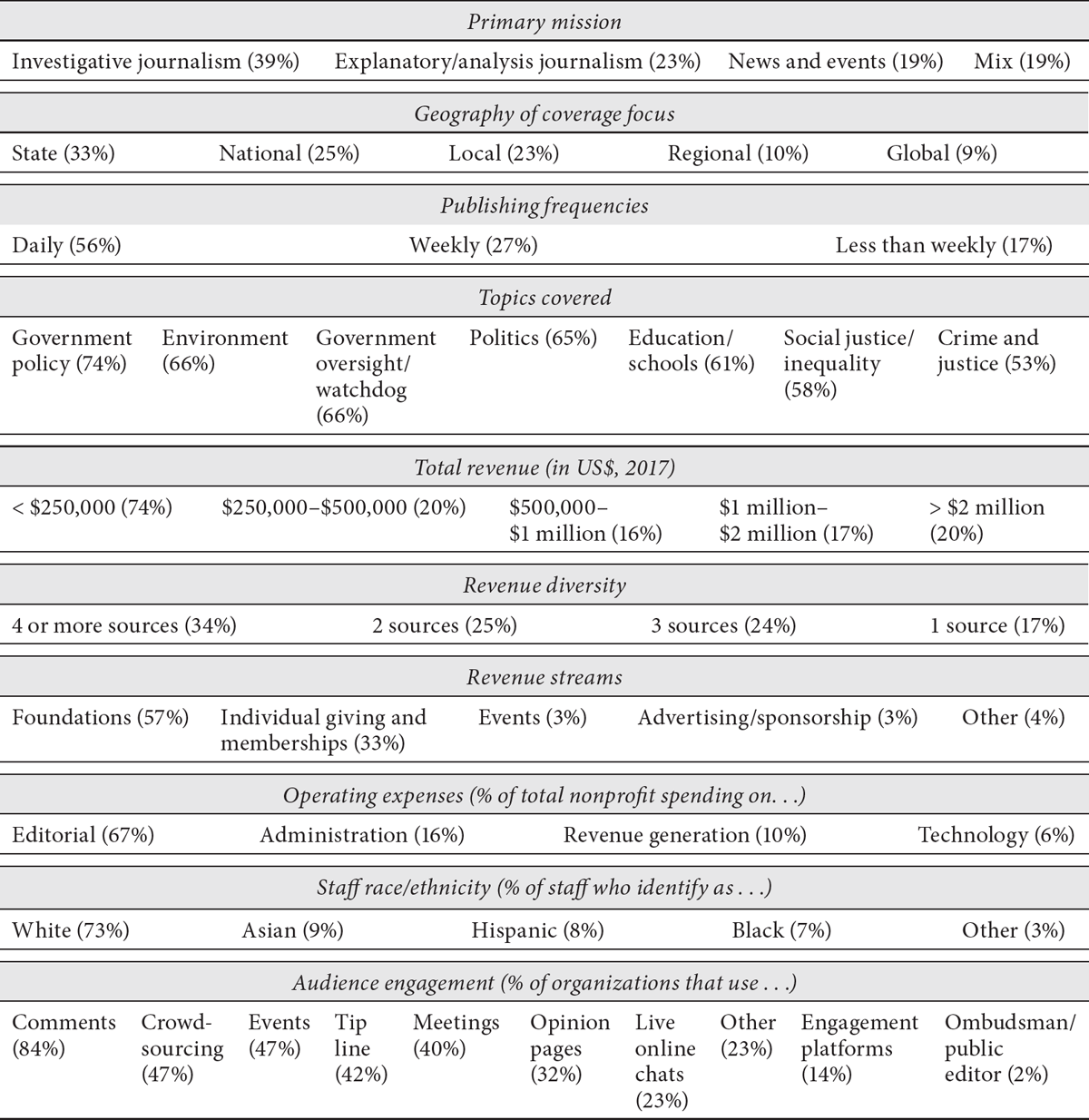

Table 22.1 Self-stated dimensions of nonprofit news organizations

Source: Adapted from McLellan and Holcomb 2018.

The nonprofit journalism space is also characterized by new ways of earning revenue that mix philanthropic, crowdfunded, and membership-supported funds, often blurring lines between for-profit and nonprofit publishing. For example, the New York Times recently created a new philanthropic division to allow it to partner with foundations and universities (New York Times 2017). For-profit news organizations Vox and Vice News regularly partner with nonprofits ProPublica and Marshall Project to gain access to original, high-quality content that they believe their commercial readers want but would not otherwise encounter (Owen 2017). Further, many local news organizations switch between nonprofit and for-profit status (Schmidt 2018; Wang 2016) as they experiment with implementing paywalls, crowdfunding resources for particular stories, renaming subscribers as “members,” and otherwise trying to identify business models that let them be revenue neutral (Aitamurto 2016; Ananny and Bighash 2016; Lee 2017). Indeed, some confusion over official status and form has played out in prolonged IRS deliberations over how to determine the tax-exempt status of news organizations with shifting missions and business models (Chittum 2011; Nonprofit Media Working Group 2013).

It is increasingly hard to talk about nonprofit news as a static or stable category neatly defined by an official organizational form or consistent ownership model. Rather, the term seems to have a broader meaning, indicating a changeable organizational status, invoked as a rhetorical device used to attract revenue, signal editorial independence, and serve as the basis for partnering with a variety of institutional actors. Understanding the field of nonprofit news requires investigating not only the actions of not-for-profit publishers but also the influence of a mix of patrons, publishers, platforms, and discourses that together portray varied images of public service, accountability, and participation.

“We’re Not a Media Company”: How New Technological Actors Help Create the Networked Press and Complicate Its Funding

The nonprofit news sector should thus be understood not only in terms of ownership control and organizational form but also in light of institutional and normative forces jockeying for public power, professional legitimacy, and financial security amid a set of private, for-profit commercially driven media technology platforms that increasingly dominate the conditions under which news circulates (Bell and Owen 2017; Chadwick 2013; Deuze and Witschge 2017; Nielsen and Ganter 2017). Indeed, the earlier reconceptualization of journalism beyond the domain of single organizations and field-level actors is now further complicated by technology companies, many of whom do not see themselves as media companies and do not want to become media companies. Facebook, for example, has repeatedly insisted that it makes technology, not media (Napoli and Caplan 2017). Despite their reluctance to self-identify as media entities, technology companies are creating with news organizations a field of journalism that is distributed across journalists, advertisers, and state regulators, and increasingly shaped by the influence of algorithm makers, data providers, and artificial intelligence creators.

This field—inhabited by technology companies like Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Amazon—shows itself not only in journalists’ practices and media distribution channels but also in subtler infrastructural dynamics. The “networked press” is an often invisible and always intertwined set of sociotechnical structures that determine the conditions under which news is produced, circulated, and interpreted (Ananny 2018). News audiences increasingly live on social media platforms; proprietary algorithmic systems surface some news over others; and user interface designs control how audience members can see, react to, share, and comment on news. Journalists see social network sites not only as publishing channels but as beats in themselves that are worthy of coverage. Moreover, most online news advertising flows through marketplaces that are almost completely controlled by Google and Facebook. The very definition of journalist is changing as increasingly hybrid labor markets emerge for technology “product managers” who can move seamlessly between news organizations and technology companies, shifting between human–computer interaction design and editorial judgment. Just as the press is no longer easily separable into for-profit or nonprofit sectors, it is also increasingly difficult to talk about the press as something that lives only or even mostly within news organizations. The power of technology companies to influence news production, distribution, and sensemaking must be acknowledged.

Amid these dynamics, news organizations seem to be trying to use nonprofit status as a tool for experimentation. This status may function as a potential means toward economic stability among fickle advertising dynamics, as a cultural marker of independence from for-profit technology companies, or an existential, ideological response to an increasingly commercialized, advertising-driven publishing space—an arena that is dominated by actors who, despite their power, do not see themselves as media companies with editorial missions or public responsibilities. For analysts concerned with how organizational forms and ownership structures relate to the press’s public mission, empirical and normative challenges have shifted; they now require seeing “the press” as a relational, networked object of study distributed across sociotechnical infrastructures.

The networked press is simultaneously instrumental and symbolic. It lives in messy, intertwined dynamics between technologists and journalists vying for control over powerful, privately controlled communication infrastructures. It also exists as an ideal—an autonomous institution imagined as a counter to mis- and disinformation, serving as the guarantor of collective, self-determining, democratic publics.

Accordingly, we are at an empirical and normative crossroads. We need to examine the sociotechnical dynamics underpinning the funding of the networked press, including the increasingly blurred lines between for- and nonprofit dimensions. We also need to ask what kind of publics such dynamics assume and create. Recalling Baker’s argument that different democracies need different media, how do different kinds of publics emerge from different types of networked press funding dynamics, especially those playing out in the space between for- and nonprofit journalism?

Different Funding Makes Different Publics

Expanding on earlier work on networked press funding dynamics (Ananny 2018), this section sketches out questions for moments when networked press funding dynamics meet ideals of the public. Specifically, based on an analysis of seven years of trade press discourse (2010–2016) about how the networked press funds itself—what Matt Carlson (2015b) calls the “metajournalistic discourse” that shows how journalism thinks about its institutional dynamics—I first identify seven dimensions of networked press funding. I then propose a set of questions that scholars of both journalism and the nonprofit sector might ask about how funding connects to publics. Although the literature on publics is expansive and broader than what can be discussed here,2 I briefly discuss eight ideals of the public to support this discussion.

Dimensions of Networked Press Funding

• Paywalls. A paywall is a virtual “barrier between an internet user and a news organization’s online content” (Pickard and Williams 2014:195) that can be crossed only by paying money. Some paywalls are always in place, making content available only to subscribers, while others come into effect after users have exceeded the number of articles to which the news organization allows free access.

• Commodified readers. News organizations often sell to advertisers and marketing firms the data they collect on readers’ demographic details and Internet patterns. They also model readers in categories that signal to advertisers their values as consumers or ask readers to answer survey questions in exchange for access to stories. Often without informed consent, readers are commodified into revenue sources for companies other than news organizations. Readers do not overtly pay for the news they consume—it appears to be “free”—but their seemingly private behavioral patterns and demographic characterizations are modeled and sold by both news organizations and technology companies.

• Crowdfunding. Conceptualizing readers as investors, some news organizations raise money from site visitors, asking them to sponsor stories in progress, to support freelancers who make appealing pitches, and to provide feedback on potential coverage by pledging support for topics and coverage areas. Although some news-specific crowdfunding sites have appeared, news organizations and freelance journalists also use all-purpose crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe.com and Kickstarter.com, tailoring their marketing and campaigns to those platforms (Jian and Shin 2015; Jian and Usher 2014).

• Commodified expertise. Some news organizations commodify their journalists’ labor and create price-discriminated access to their products. For example, they earn revenue by selling access to member-only events, to raw data that their journalists have gathered and/or vetted, and to tiered levels of content through application programming interfaces. News organizations increasingly see themselves as curators of people, data, legitimacy, and interpretation, selling access to this trusted expertise (ProPublica n.d.).

• Sponsored content. Variously called native advertising, paid content, or promoted stories, some news organizations explicitly mix commercial and editorial content, creating advertisements that look like stories and subcontracting out staff to advertisers willing to buy journalistically produced marketing materials. Such blurring appears in hybrid genres—ads that look like stories and vice versa—and shared labor pools between advertising and editorial departments (Wojdynski 2016).

• Organizational partnerships. Several news organizations create strategic alliances with other news organizations and technology companies, agreeing to share sourcing and credit, creating platform-specific versions of stories, exclusively sequestering some news within platform-created mobile apps and data formats, and training staff on how best to prepare stories for particular platforms. The terms of such partnership are usually proprietary secrets, but news organizations make such deals as ways to share labor, data, online traffic, or privileged positions within algorithmically determined news feeds (Center for Collaborative Media 2018; Stonbely 2017).

• Research sponsorship. Although not publishers per se, some journalism researchers—both independent think tanks and university academics—enter into strategic partnerships with technology companies, accept sponsorship from platform companies, and receive funding from foundations, all of which have programmatic interests in better understanding the networked press.

Each of these dimensions is relevant to the practices of a range of news organizations and technology companies, and many publishers and platforms engage in more than one of the strategies described. Together, these dimensions illustrate a diversity of revenue dynamics used by both for-profit and nonprofit news organizations.

Ideals of the Public

Since publics are constructed through complex and intertwined normative, sociological, cultural, and technological forces—that is, they are always made, never found—it becomes evident that different publics are possible, depending on different communicative conditions. Though the list is not exhaustive, the following ideal types of publics often appear as assumptions or goals of the networked press.

• Deliberation and consensus-based. Most closely aligned with Jürgen Habermas’s notion of the public sphere (Habermas 1989), this type of public privileges the rational, information-based exchange of private perspectives among equal, private individuals who discover public consensus on topics of shared interest through deliberation that endures until decisions are made.

• Participatory social good. Grounded in an ideal of civic life as experiencing and sharing a wide variety of cultural perspectives through engagement with a diverse set of people, social positions, media practices, and communicative settings, this model shapes the public good through mutual exchange and experimentation with perspective taking.

• Aggregated opinions. Driven by the development of techniques for modeling, sampling, and representing social groups through individual surveys and statistical methods, this image of the public rationalizes people and public opinion into demographic and quantitative patterns (Salmon and Glasser 1995).

• Shared consequences. Often associated with John Dewey (1954) and American pragmatism, this type of public arises from the discovery of social conditions and material impacts that individuals cannot escape, with the idea of “public” emerging only when people see which aspects of their lives are inextricably linked.

• Sustained differences. Eschewing the ideal of consensus or shared identity, this type of public aims to be a “decentered” space inhabited by people of different languages, identities, and ideological positions who can speak “across their difference” while remaining accountable to each other (Young 2000:107).

• Agonism and contestation. Expanding further on the scope of diversity, this type of public explicitly rejects a goal of consensus, deliberation, or even mutual acceptance of difference; instead it calls for a “sphere of contestation where different hegemonic political projects can be confronted” (Mouffe 2005:3–4).

• Enclaves. Recognizing the harm that visibility can do to historically disempowered groups who need time and space to discover their shared conditions and plan for resistance against dominant social forces, this public calls for private communication within and among groups that need “to survive and avoid sanctions, while internally producing lively debate and planning” (Squires 2002:448).

• Recursive. Inspired by observations of hacking cultures concerned with maintaining the technological ability to control the conditions under which they communicate and convene (Kelty 2008), this public is concerned with having the power to define and manage itself, according to the associative criteria it chooses.

In Table 22.2, I present critical questions at the intersections of funding instruments and public types. Though it is certainly not comprehensive in light of the myriad questions that could be asked—nor does it indicate which questions may be more or less important—the table illustrates how, for any given approach to funding, key questions can be posed around whether, or how, particular publics can emerge from that support.

Starting with a funding instrument, the chart can be read as follows: If this approach to funding is taken, and this type of public is desired, then this question needs to be addressed.

In terms of advocacy, the press is constantly struggling with whether to represent or amplify their own interests and those of others, or to eschew all interests and retreat into objectivity and neutrality, letting events and sources guide their storytelling. Advocacy begins to look complicated.

Sometimes, journalists openly champion interests and values that a given era defines as obviously right and worthy of public mobilization. Though people may differ about policy interventions and remedies, it is largely uncontroversial for journalists to investigate and write about the eradication of poverty, disease, and various social inequalities. Journalists may not get the money and time they need from their editors to pursue the topics in great depth, but few publishers would see a story pitch on links between structural racism and health outcomes as fringe or unprofessional advocacy. This is what James S. Ettema and Theodore L. Glasser (1998) mean when they describe most investigative reporting as fundamentally conservative. Though many investigative journalists courageously pursue stories that challenge power and put themselves at risk, they follow largely uncontroversial commonsense assumptions about what is right and wrong, what is worth advocating for, and what mainstream norms champion. No one questions the values of an investigative reporter exposing government fraud or unjust incarceration; such things are plainly wrong. But when Ida B. Wells wrote her exposés of lynching cultures in the U.S. South, she was criticized by both politicians and journalists for attacking the region’s historical traditions and pursuing her own ethical interests, not broadly shared values. And when, in his investigative novel The Jungle, Upton Sinclair advocated for labor rights by uncovering the unsafe working conditions in meat-packing plants, public officials responded by reforming the plants’ unsanitary food preparation practices; his interests in workers’ unsafe environments and long hours were seen as his personal missions, not widely shared calls to action.

The press usually advocates in ways that people expect. Journalists resist taboo, controversial topics and instead largely work within what Daniel C. Hallin (1986) calls the “sphere of legitimate controversy.” This is the sphere where debate is encouraged, where healthy democratic discourse is thought to live. But debate and discourse are limited to perspectives and opinions that are already seen as acceptable, that align with other people’s commonsense expectations of advocacy. Most news coverage exists in this sphere—such as pro-choice versus pro-life, the death penalty, tax policy, health care, social programs.

Table 22.2 Sample critical questions at the intersection of networked press funding dimensions and types of publics

In contrast, two other spheres receive little attention, but both teach us something about how the press understands advocacy. The sphere of consensus is filled with topics that journalists do not think need advocacy. For example, human trafficking rings may need to be investigated and there are legitimate debates about what to do about it, but no one openly debates the merits of slavery. Mainstream society has reached a consensus that there are not two legitimate sides to slavery. Environmental coverage is a kind of crossover category between the sphere of consensus and the sphere of legitimate controversy. Some politicians persist in seeing the human cause of climate change as debatable, and some news organizations continue to tell “both sides” of the climate change story. But other news organizations have moved the topic into the sphere of consensus. For example, in 2013 the Los Angeles Times declared that it would no longer print letters to the editor that questioned the existence of human-caused climate change (Thornton 2013). To the Times, the debate was over, there was no legitimate controversy, and consensus had been reached. To the extent that the Times was advocating for a particular cause of climate change, it did so by declaring that part of the climate change story to be over.

Conversely, the sphere of deviance contains issues that are considered too far outside mainstream concern to warrant journalistic attention. For a long time, transgender rights, same-sex marriage, and single-payer health care were all considered too deviant to cover. And for years, the mainstream U.S. press largely ignored the HIV/AIDS epidemic, leaving coverage to the gay press until the issue was seen as sufficiently important to overcome enterprise journalists’ hesitation to cover the gay community (Rogers, Dearing, and Chang 1991).

The press advocates, but it does so in subtle ways. By adopting widely held, commonsense classifications of topics as debatable, taboo, or lacking controversy, it essentially advocates for a conservative system of values, the system that dominates the cultures and eras it operates within. For journalists to do otherwise—to overtly inject their own sense of what they think should be covered separate from what dominant social forces imply—would be to acknowledge that they have points of view, and that those perspectives can and should guide coverage. This is usually a bridge too far for U.S. journalists steeped in rituals and routines of objectivity. In this case, the public is presumed to be a deliberative, consensus-building public that needs journalists to provide disinterested, unbiased information that tells the stories of advocates representing viewpoints seen in acceptable, predictable tension.

Journalistic advocacy can also come from publishers’ interests—from the perspectives of those with the power and resources to inject their own values into coverage. Although they rarely overtly direct their newsrooms, evidence suggests that reporters and editors are aware of their publishers’ interests and will tailor coverage to align with what they perceive their boss’s perspectives to be (Bezanson 2003; Chomsky 2006; Wagner and Collins 2014). To the extent that such a news organization advocates, it does so subtly and through the influence of its owner. Advocacy—or the perception of interests—can also take the form of subtle organizational norms. A news organization that caters to what it sees as its readers’ interests may declare itself independent, but it is, in fact, beholden to market interests. Put differently, such a news organization advocates for its ideas of what markets see as readers’ interests. It becomes a second-order advocate driven by what commercial interests see as audience desires. Such market-driven logics—even those that go unstated but underpin newsroom cultures—may skew coverage away from topics that may be of great public significance but little overt audience interest. Such a newsroom is driven more by customer service than public advocacy.

Relationships between funding and advocacy can also be seen in organizations that focus on particular beats. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s funding of health care reporting is a type of advocacy in that it supports news organizations that cover its broad themes; journalists’ individual reporting may be independent of the foundation’s editorial oversight, but the foundation defines the general scope of coverage. Similarly, the newly funded news organization The Markup—founded by former Wikimedia head Sue Gardner and former ProPublica journalists Jeff Larson and Julia Angwin—is underwritten by Craigslist founder Craig Newmark, as well as the Ford, Knight, and MacArthur Foundations. To the extent that The Markup practices advocacy (in its case, focused on investigative reporting designed to hold technology companies publicly accountable), it does so in ways that are consistent with its funders’ expectations of the beats and debates it will cover.

Many types of advocacy may appear throughout news organizations and journalists’ reporting. Some are overt and appear in choices like whom to interview and what language to use. Others are more structural, embedded in subtle relationships between publishers and editors, journalists and audiences, social norms and habits of reporting. The aim of Table 22.2 is to trace these sources of power and public making through particular funding arrangements and to pose normative questions of those arrangements. Journalism and its funders are under no obligations to pursue any particular vision of the public, but in their choices to accept or pursue some funding over others, they leave clues about which publics they value and advocate for and which are seen as unacceptable or biased. The questions at the intersections of revenue sources and types of publics are meant to help scholars and practitioners alike better appreciate the kind of publics nonprofit news creates.

Conclusion

What kind of publics can different configurations of the press support? Recalling Baker’s claim that different democracies need different media, this chapter argues that the U.S. press has always grappled with how to both ensure and resist intertwined senses of financial success and public service. Striving to be distinct from other forms of publishing, how can news organizations render their organizational missions and senses of public service in their financial models? How do news organizations’ ownership models and financial relationships to markets, states, benefactors, audiences, advertisers, and organizational partners empower or interfere with the kinds of publics they can create?

Though not without historical antecedents, these questions are being posed anew as the core configuration of the press is changing. New entrants have appeared as journalistic partners, new types of fund-raising are now possible, and new understandings about the role of information in public life are in flux as more people than ever, for lower cost than ever, can look like the press. Journalism is faced with the critical question of how it differs from media and technology platforms, and how its public service is like or unlike other information providers.

One way to understand these differences is to examine closely not only how the networked press funds itself but also how different approaches to funding lead to different types of publics. I have tried to argue in this chapter that the press may better be thought of as the networked press—a distributed set of intertwined sociotechnical forces through which news is produced, circulated, and interpreted—and that this networked press is experimenting with a variety of ways of funding itself. Some of these funding techniques make the press seem like a new type of public service—affinities for crowdsourcing, online advertising, and philanthropic support can make journalism seem more accessible than ever. Other approaches show the press to be a deeply commercial enterprise that is highly dependent on online surveillance, subservience to technology platform preferences, and commodification of its labor and data. Although many nonprofit news organizations can be classified according to their official tax status or organizational mission, the degree to which the networked press intertwines commercial and noncommercial forms and for-profit and nonprofit interests makes it difficult to say exactly where the nonprofit press starts and stops.

The nonprofit press represents a kind of advocacy journalism. Its advocacy is not linked to a particular issue, position, or outcome but rather to an ideal of the public. In contrast to a state-driven media system that may confuse government interests with journalistic mission, or a market-driven media system that equates audience desires with public interest, the nonprofit press carves out a third space that is arguably better equipped to advocate for an image of the common good that is free(r) from politics and commerce. The challenge, though, is to identify this third space and advocate for it by thoughtfully and purposefully ensuring the financial health of nonprofit journalism.