Figure 30.1 Size of nonprofit sector paid vs. volunteer workforce, by country

Source: Author; based on data reported in Salamon et al. 2017, pp. 276–279.

COMPARATIVE NONPROFIT SECTOR RESEARCH

A Critical Assessment

Helmut K. Anheier, Markus Lang, and Stefan Toepler

THIS CHAPTER OFFERS A CRITICAL REVIEW of comparative, cross-national research on the nonprofit sector. It argues for a need to revisit the fundamental assumptions underlying comparative research in this area. Specifically, we suggest a reexamination of the definition and classification of nonprofit organizations; a review of the institutional embeddedness of nonprofit organizations and their relationship with the three institutional complexes of market, state, and civil society; and the field’s analytic approach, in particular the social origins theory. We ultimately call for the field’s connection to a wider social science research agenda. The outcome of this would be a comparative-historical research agenda informed by political science and sociology to complement the macroeconomic approach, largely based on national income accounting, that has characterized the field for nearly three decades.

Since the first edition of this book (Powell 1987), the field of nonprofit studies has come of age in many countries. Conceptual issues seem more settled; there is a set of mostly complementary theories about the existence and the behavior of nonprofits in market economies; and the empirical base of the field has improved in both quality and quantity. The academic infrastructure has expanded, too. Teaching programs in a growing number of countries have responded to student demands at both undergraduate and master’s levels (Mirabella and McDonald 2012; Mirabella, Hvenmark, and Larsson 2015); the number of PhD students entering the field has increased (Jackson, Guerrero, and Appe 2014; Shier and Handy 2014); academic journals with respectable impact factors were launched, as were scholarly associations (D. Smith 2013); and textbooks, dictionaries, encyclopedias and handbooks addressing an international audience have been published (e.g., Anheier 2014, Anheier and List 2005; Anheier, Toepler, and List 2010; Wiepking and Handy 2016; D. Smith, Stebbins, and Grotz 2017).

What is more, the policy relevance of nonprofit organizations seems to have increased (Suárez, Chapter 20, “Advocacy, Civic Engagement, and Social Change”; Walker and Oszkay, Chapter 21, “The Changing Face of Nonprofit Advocacy”), leading to greater recognition at both national (e.g., Almog-Bar and Young 2016; S. Smith and Grønbjerg 2015) and international levels (Schofer and Longhofer, Chapter 27, “The Global Rise of Nongovernmental Organizations”; Dupuy and Prakash, Chapter 28, “Global Backlash Against Foreign Funding to Domestic Nongovernmental Organizations”), as reflected in the UN’s Cardoso Report (Cardoso 2004). Independent research institutes and think tanks have sprung up in many countries. So have consultancies specializing in nonprofit organizations or specific topics (such as philanthropy or NGOs), which have proliferated in the political and economic capitals of the world. Being an expert on nonprofit organizations is no longer as unusual as it may have been a generation ago. Indeed, a certain acceptance into the academic and political mainstream marks the field today—something that was certainly absent in the 1980s.

A Field Evolving

At the risk of oversimplification, three major periods characterize the international development of nonprofit research. The 1970s and 1980s saw the field emerge in the context of the American economy and society at a time of extended economic recession and subsequent retrenchment of welfare programs; in the 1990s, international efforts gathered momentum; and the 2000s onward brought a focus on civil society and the advocacy role of nonprofit organizations.

The 1980s were largely a decade of theory building shaped by the U.S. experience, as presented in the first edition of this book (Powell 1987). The research agenda at that time set forth three main questions (DiMaggio and Anheier 1990): why do nonprofit organizations exist in market economies, what is their organizational behavior, and what is their impact? The major theories introduced during that period still provide the foundations for the field, and, indeed, subsequent developments build on them (see Steinberg 2006; Anheier 2014: chap. 8).

Of particular importance here were the heterogeneity theory or government failure theory, which suggested that when unsatisfied demand for public and quasi-public goods occurs in situations of demand heterogeneity and limited public budgets, nonprofit providers form (Weisbrod 1975, 1988; Kingma 2003; Slivinski 2003). The trust theory or market failure theory proposed that the nondistribution constraint makes nonprofits more trustworthy under conditions of information asymmetry, which makes monitoring expensive and profiteering likely (Hansmann 1987; Ortmann and Schlesinger 2003). The stakeholder theory argued that given profound information asymmetries between provider and consumer, which imply significant transaction costs, stakeholders decide to exercise control over delivery of club goods (Ben-Ner and Van Hoomissen 1991; Krashinsky 2003). The interdependence theory posited that because of initial collective-action advantages, nonprofit organizations precede government in providing public goods; however, because of “voluntary failures,” they are likely to develop synergistic relations with the public sector over time (Salamon 1995).

What these theories had in common was that they were based on the “American case” of a liberal market economy with a decentralized, competitive electoral system and heterogeneous demand for quasi-public goods. They were not necessarily meant to have cross-national applicability. Nonetheless, in the late 1980s, the first comparative studies began to appear.1 Estelle James (1983, 1987, 1989) pioneered the field with her empirical work on the supply and demand conditions of nonprofit service provision in developing countries. She argued that they differed from developed market economies mainly in the chronic scarcity of quasi-public goods, such as education and health care, irrespective of demand heterogeneity or trustworthiness considerations. In most cases, such shortages were due to limited state capacities to deliver these goods; in others, it was indicative of elite capture.

Insights from these and other studies formed the basis of entrepreneurship theory (James 1987), which argues that nonprofit organizations are created by entrepreneurs seeking to maximize nonmonetary returns. The entrepreneurs in James’s theory are political, religious, cultural, and humanitarian activists driven by values (including world-views, moral dispositions, beliefs, and opinions) and normative dispositions. They use the nonprofit form for product bundling and co-production—for example, services such as teaching, caring, or healing that take place in a value-based context. Their hope is that infusing service provision with values would make recipients more susceptible to the organization’s ultimate purpose. Religious schools or hospices are perhaps the clearest examples.

At the same time, economists also picked up the notion of product bundling to understand the revenue generation strategies of nonprofit organizations. They differentiated between preferred quasi-public goods, preferred private goods, and nonpreferred private goods (Schiff and Weisbrod 1991). For example, in a religious context, the preferred quasi-public good is the value to be spread in order to create a community of faith, such as the Christian gospel or the Qur’an. Alternately, the preferred private good, which nonprofits aim to optimize, is the education delivered in parochial schools or madrassas. Finally, the nonpreferred private good, which nonprofits use opportunistically, would be sales of religious symbols, pamphlets, or relics.

The co-production concept similarly emerged during that period and received the attention of public administration scholars (Brudney and England 1983) and economists (Ostrom 1975). It refers to situations where the consumers or beneficiaries of a service, often a quasi-public good, collaborate with providers on its design and delivery. For example, patients co-design treatment plans with their health care providers; residents organize neighborhood watches to improve public safety; and nonprofit housing organizations require tenants to help with the construction and maintenance of their future homes (Brandsen, Steen, and Verschuere forthcoming). In addition to individual utility considerations, co-production includes a commitment to a common good and some level of communal trust, which made the concept attractive to social welfare scholars and urban planners.

The noneconomic motivations highlighted by James became a preoccupation of a body of comparative research that looked at how nonprofits combine services with value dispositions (see Anheier and Seibel 1990; Wuthnow, Hodgkinson, and Associates 1990). This approach focused on instances of institutional patterns that rest on deep-seated social, religious, or political foundations. Examples are the principle of subsidiarity in Germany (Anheier and Seibel 2001), pillarization in the Netherlands (Burger et al. 1999), the social economy in France (Archambault 1997), the British tradition of charity (Kendall and Knapp 1997), popular movements in Scandinavia (Lundström and Wijkström 1997; Tranvik and Selle 2007), or concepts of the public sphere in Japan (Amenomori 1998). The main insight of this research was that embedded institutional patterns and the underlying values they express—that either challenged or supported the political system in place—shaped not only the size and composition of the nonprofit sector but also the basic orientation of its organizations.2

Comparative Nonprofit Sector Research: Looking Back, Looking Forward

This upswell of research in the 1980s left students of the nonprofit sector conceptually richer, but poorer in evidence that could be used to test the cross-national applicability of these theories. The 1990s corrected some of that imbalance. It was a decade of establishing the methodological and empirical foundations of comparative research. Of these efforts,3 the most impactful was the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (CNP) (Salamon and Anheier 1996). CNP addressed major challenges that had long frustrated students of comparative nonprofit sector research. It introduced a definition, a classification system, and ways of measuring nonprofit activity. Most importantly, CNP succeeded in meeting two major objectives. First, it was instrumental in establishing a satellite account on nonprofit organizations as part of the international System of National Accounts, or SNA (United Nations 2003). Its work on this front allowed for the increased collection of comparable data on different nonprofit sectors across time. Second, CNP aided the creation of initial attempts to understand cross-national variations in nonprofit sector size and scale through the social origins theory.

While systematic comparative nonprofit research, heavily driven by CNP efforts, was taking shape, the early 1990s saw the simultaneous revival of the concept of civil society that often overlapped with nonprofit-focused research but remained distinct in its emphases and intellectual orientations. Civil society rather than nonprofit became the predominant label for more activist and political forms of voluntary action. The civic resistance against the military juntas of Latin America and then the totalitarian state socialism in Central and Eastern Europe patterned interests in Gramscian notions of civil society as a protective sphere guarding society against an overpowering state and emphasizing the potential for conflict.

Central European intellectuals and dissidents like Adam Michnik and Vaclav Havel as well as Western intellectuals like Ralf Dahrendorf and Timothy Garton Ash were prominent voices in the revival of the idea of civil society after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 (e.g., Kumar 1993).

The concept soon gathered considerable political acceptance and was quickly co-opted by influential U.S. foundations (Quigley 1997; Aksartova 2009), which provided additional currency to the policy proliferation of the field as a whole (Lewis 2014). But it also created conceptual confusion as to how the notions of a nonprofit sector and civil society differ: for some, the nonprofit sector and civil society were basically synonymous, exemplified by CNP, which changed its labels from nonprofit to civil society in the late 1990s, while leaving the basic approach described earlier untouched.4 For John Keane (2005:26), CNP was accordingly among the “various research projects that suppose that civil society is equivalent to the not-for-profit ‘third sector.’” In the field of international development, Thomas Carothers (1999) similarly held that civil society often gets equated with NGOs, albeit inappropriately. For others (Dahrendorf 1997; Kaldor 2003), civil society is distinct from the organizational focus of nonprofits and reflected more individual dispositions on the one hand, even reaching into aspects of civility, and institutional characteristics on the other, as exemplified by Jürgen Habermas’s public sphere (1989).

Clearly, the decisions CNP made in the 1990s had, and continue to have, major consequences for the development of comparative nonprofit sector research.5 It is therefore worthwhile to review them in some detail, and in particular so that they may inform a future research agenda. However, as seen, CNP and comparative nonprofit research do not perfectly align with the full breadth of the international civil society discourse. In the following, we will therefore first reexamine the cross-national definition, classification, and theorizing of nonprofit sector research and then discuss the implications of the nonprofit versus civil society dimension before providing a concluding outlook.

Defining Nonprofits

First, there is the question of definition. Although defining what a nonprofit organization was relatively straightforward in the U.S. context,6 it was more complex internationally for two reasons. First, international data systems, most prominently the SNA, defined nonprofit organizations in ways that were unsuitable for comparative research (see special issue of Voluntas 4(2), 1993; Anheier, Rudney, and Salamon 1994). The SNA (2009) uses a standard revenue approach, according to which nonprofits do not price their goods and services to cover the cost of production, are not financed predominantly through taxation, and are not primarily consuming entities. In other words, they are defined as a residual category: they are not market producers, government organizations, or households. Specifically, nonprofit organizations that receive more than half of their revenue through fees, charges, and sales are treated as market producers and allocated to the business sector; those that receive more than half of their revenue from government are treated as part of the public sector; and those that do not offer goods and services are treated as households. The resulting sector of “nonprofit institutions serving households” received little attention by statistical agencies; at the time CNP commenced in 1990, just a handful of the nearly two hundred countries providing SNA statistics reported any data on the nonprofit sector. As a result, available official data on the nonprofit sector were sparse, distorted, and inconsistent (Anheier et al. 1994). Second, with viable approaches lacking for comparative purposes, relying on national definitions and ways of measuring the sector turned out to be a major challenge.

Faced with these issues, CNP turned to the national level. It found that different legal systems, institutional patterns, cultural traditions, and levels of development accounted for a great diversity of organizational forms located between the state, the market, and the family.7 The challenge CNP faced went well beyond seemingly merely semantic issues. For example, the British call public schools what the Americans call private schools; similarly, in Europe, different national definitions of foundations are difficult to reconcile (Toepler 2016, 2018b). Underneath these differences are often deeply rooted institutional histories and cultural patterns—even for close cousins like the American and British charities that share origins in the English Poor Laws of 1601.

In confronting such an immense terminological tangle, CNP chose to focus neither on how nonprofits are defined by respective legal systems nor on their functions, such as charity or public benefit, as defined in different national or cultural contexts. The former would have generated confusion that would have stifled comparative research; the latter would have invited normative debates about what constitutes these functions, how to assess their contributions, and who gets to define the public good. Consider the definitional challenge: what do American nonprofit universities like Yale or Stanford, Japanese industry associations like Keidanren, Catholic schools in France, a network of homes for the elderly run by the social services branch of a Protestant Church in Germany, village associations in Ghana, urban improvement organizations in Brazil, Amnesty International, Greenpeace, a sports club in Denmark, a village hall in England, Islamic endowments in Egypt (waqfs), and the Ford Foundation have in common?

As a way forward, CNP introduced a structural-operational definition (Salamon and Anheier 1992a, 1997) as a common denominator cutting across different functional conceptualizations, legal systems, levels of development, and national traditions. According to this definition, nonprofit organizations are organized, private legal, and self-governing entities that are nonprofit-distributing and voluntary. The sum of entities so defined constitutes the nonprofit sector of a given country.

Taking nonprofits out of their particular legal, cultural, and national contexts was bold. This conceptual maneuver is of critical importance, as it establishes a nonprofit “sector” as the totality of organizations fitting the preceding definition. The CNP approach does not ask if a country has some notion of a distinct sector for organizations set apart from the market and the state, or if the sector fits into the cultural, political, or social context of the country’s institutions. Instead, it identifies the sum of nonprofit organizations based on an operational criterion. Then it estimates the size of the sector using an essentially SNA-like approach to GDP measurement based on employment indicators.

Figure 30.1 shows the relative size of the nonprofit sector measured as a share of the economically active population in all forty-one countries covered by the CNP database as of 2016.8 The sector’s size varies between 15.9 percent in the Netherlands and 0.7 percent in Romania. To arrive at these percentages, CNP sums up the share of both full-time equivalent paid employees and volunteers working in the nonprofit sector relative to the economically active population (e.g., 10.1% + 5.8% in the case of the Netherlands; 0.3% + 0.4% in Romania).

The forty-one-country average of this central measure of economic size is 5.6 percent. There are a few countries in the sample whose sector comprises less than 1 percent of the economically active population (e.g., Romania, Poland, and Slovakia). By contrast, there are some countries whose sector’s size exceeds 10 percent (e.g., the Netherlands, Israel, and Belgium). Figure 30.2 shows that in most countries, the nonprofit sector constitutes less than 5 percent of the working population, with 1 to 3 percent as the modal category. Countries with large nonprofit employment share are clearly the exception. The distribution is positively skewed, which means that the median at 4.6 percent is below the average of 5.6 percent. In other words, smaller nonprofit sectors are more common than larger ones.

However, the sector aggregations displayed in Figures 30.1 and 30.2 may not necessarily fit the broader institutional reality of a country. Some of the countries included may not have known that they had a nonprofit sector of this sort, linguistic differences set aside. Countries may have a range of organizations located between the state and the market, their institutional patterns perhaps only weakly organized around the nondistribution constraint and the other features of the structural-operational definition. Even if they can be grouped together along these lines, they may not be thought of as a coherent “sector.”

Figure 30.1 Size of nonprofit sector paid vs. volunteer workforce, by country

Source: Author; based on data reported in Salamon et al. 2017, pp. 276–279.

Figure 30.2 Histogram of nonprofit sector size by country

Source: Author; based on data reported in Salamon et al. 2017, pp. 276–279.

Three brief examples from Europe illustrate these differing conceptions. In France, the overall institutional concept is the social economy, which includes voluntary associations, cooperatives, and mutual corporations (Archambault 1997). In Germany, on the other hand, the notion of public utility largely serves as the overarching concept that covers service providers, associations, and foundations (Anheier and Seibel 2001). Finally, in Britain, there are two parallel notions, charities and voluntary organizations (Kendall and Knapp 1997). These countries use neither CNP’s definition of a “nonprofit organization” nor the concept of a nonprofit sector.

In essence, CNP did for cross-national research what Peter Hall (1992) argued that initiatives like the Yale Program on Nonprofit Organizations did in the United States: it invented the nonprofit sector. Hall criticized the cryptonormative stance of nonprofit research in the United States, which he saw as caught between two opposing “projects”—a liberal approach to increase social participation and a conservative approach to limit the size of government. By contrast, CNP’s intent was more methodological when it established the definition of nonprofit organizations and sectors.

Let’s reexamine the CNP definition in the context of a conceptual mapping of the nonprofit sector and its institutional proximities (Figure 30.3). Recall that the structural operational definition established five core characteristics for nonprofits independent of their basic form, governance structure, or purpose. This is appropriate for national accounts purposes, as such distinctions need not enter SNA logic. Thus stock corporations, for-profit cooperatives, limited liability companies, and joint proprietorships are all market producers despite their differences. Similarly, all types of public agencies and quasi nongovernmental organizations (quangos) are treated as government entities irrespective of their actual form or purpose. Lastly, different types of nonprofit organizations are treated the same under SNA guidelines. Yet the three basic categories of nonprofits (and the many hybrids that exist9) imply not only different types of governance but also different purposes and activities that arise from different institutional contexts. Specifically:

• In the case of nonprofits as membership associations, members and their shared interests provide the raison d’etre for the very existence of the organization; they constitute some kind of internal democracy. Members typically have a decisive role in leadership formation and representation in governing bodies. Membership associations therefore require some degree of freedom of association and a capacity for self-organization. In many countries, freedom of association was a politically contested issue and part of a struggle to establish a realm of citizen engagement independent of direct state supervision. As a result, a country’s degree of self-organization is contingent on state–society relations, as well as factors like religion, education, socioeconomic status, class mobilization, and regionalism.

• For nonprofits as corporations based on set capital and limited liability, a self-perpetuating board substitutes for owners and publicly represents the organization. Such corporations are typically service providers. They operate mostly in the fields of education, social services, health care, and, to a lesser degree, housing. Their emergence is linked to the development of the modern corporation, the rise of the service economy, and the welfare needs of modernizing societies. Unlike associations, they require significant capital and regular revenue. Reforms in recent decades across both advanced and developing countries increasingly see such corporations as part of new public management and quasi-market arrangements.

• Nonprofits as asset-based foundations feature a governing board that holds and operates an endowment in trust for a dedicated charitable purpose. They are among the freest institutions of modern society, in that they can operate independent of short-term expectations of market returns or political support. Unlike associations, they have no internal demos (i.e., membership). In contrast to corporations, they rarely provide a service to customers. Their setup requires not only accumulated capital but also a license or guarantee from government to operate with significant freedom.

As Figure 30.3 illustrates, nonprofit organizations do not exist in isolation from the three institutional complexes of state, market, and civil society. In fact, the nonprofit sector emerged over time in ways that involved complex and conflictual interactions with other institutions. In many cases, it created overlaps with them: markets with social enterprises or cooperatives; the state with public authorities, quangos, and public–private partnerships; and civil society with social movements and forms of civic engagement. We now turn to three historical examples that illustrate the embeddedness of nonprofit organizations.

In France, the state had for prolonged periods of time suppressed most forms of private, voluntary initiative. Although the Ancien Régime had already abolished foundations in order to contain the power of the Catholic Church, the Loi Le Chapelier, established shortly after the revolution in 1791, also forbade all intermediary associations between the citizen and the state. The idea was that the state was to serve as the arbiter of the public will. Although a social economy was gradually developing out of the workers’ movement, organized civic activity remained limited over the following century. It was not until the Law on Associations in 1901 that this type of voluntary organization was relegitimized. The law reintroduced it as a legal form under the tutelage of a central government. The relationship between the market economy and social economy on the one hand, and the association movement and sociability on the other, were part of the emerging nonprofit sector. Whereas the social economy was championed by the workers’ movement, the association movement’s ranks came from the urban middle class. Foundations continued to face a very restrictive political-legal environment throughout most of the twentieth century and were only allowed to operate under state tutelage until the 1980s (Barthélémy 2000; Worms 2002; Archambault 1997). In other words, the French nonprofit sector has historically involved the corporate form of nonprofit service providers closely linked to the social economy. It is less concerned with associations as social self-organization and hardly at all with independent assets.

In the Scandinavian countries, the state also played an important role in shaping the nonprofit sector. During the nineteenth century, broad-based popular movements emerged that connected local members with national politics. These movements provided professional services, political representation, and recreational activities for their membership. The emergence of the welfare state was thus met with a membership-based organizational infrastructure that continued to flank it, even as the actual service provision fell to state institutions (Wollebæk and Selle 2008). In Sweden, the public status of the state church (which lasted until the 1990s) facilitated the transition of nineteenth-century charitable institutions to state responsibility (Lundström and Wijkström 1997). The Swedish nonprofit sector consists mostly of associations developing mutually supportive relations with the state; it is neither a sector of corporate service providers nor of asset-based foundations.

In Germany, unlike France and Scandinavia, all forms assumed importance. The principle of self-administration, or self-governance, originated in the nineteenth century as part of a conflict settlement between the expanding Prussian state administration and the rising urban middle class. Under an autocratic regime, it allowed for the development of a specific kind of civil society that emphasized the role of the state as grantor of freedom for the regulated self-organization of municipalities, as well as trades and professions. It also allowed both associations and foundations to flourish in a controlled way. Elsewhere, the principle of subsidiarity provided a framework for settling secular-religious tensions, especially those involving the Catholic Church. After World War II, this principle developed into a policy pattern that prioritized nonprofit over public administration of social services (Sachße 1994), which led to a significant expansion of nonprofit corporations. Finally, the principle of communal economics, linked to the workers’ movement, led to the cooperative movement and the social economy. This principle assumed significant importance during the reconstruction era of the 1950s and 1960s, especially in housing. Many communal organizations later transformed to for-profit entities.

In none of the cases do we see the sort of nonprofit sector conceptualized as by CNP per se. It overlaps with other institutional complexes but in ways that are different in France as they are in Germany or Sweden. What is more, the institutional space that nonprofit organizations occupy can contract, sometimes radically. The introduction of the National Health Service in postwar Britain meant that many hospitals and health-related entities that were organized and registered as charities were nationalized and thereby became public corporations and trusts (Kendall and Knapp 1997). This significantly reduced the economic size of the nonprofit sector. In the United States, Henry Hansmann (1990) showed that nonprofit credit and savings associations, thrift societies, and mutual insurance companies gradually declined as more effective government regulation of the financial sector took hold after the Great Depression. More recently, the conversion of many nonprofit institutions into for-profit entities increased commercial competition and reduced the number of U.S. nonprofit hospitals considerably between the 1980s and late 2000s (Goddeeris and Weisbrod 1998; Gray and Schlesinger 2012).

As with the Scandinavian example, the orientation of the nonprofit sector can change as well. The incorporation of most church-related charities into the public sector, with the parallel proliferation of popular social movements resulting in a civic culture of participation and voluntarism, left only a limited role in terms of service provision for the sector (Lundström and Wijkström 1997). An emerging hallmark of many hybrid and authoritarian regimes, like Russia and China (Benevolenski and Toepler 2017; Teets 2014), is efforts to suppress Western-funded social justice NGOs that are heavily engaged in advocacy activities. At the same time, these governments are creating incentives to enlist more apolitical, service-focused nonprofits in what represents a neoliberal turn away from the statist welfare regimes of the past (Tarasenko 2018).

In short, the institutional positioning of the nonprofit sector illustrated in Figure 30.3 can shift over time, which suggests the notion of co-evolution of institutional analysis (Mahoney and Thelen 2010). The structural operational definition, by contrast, cannot accommodate this phenomenon. Using examples from housing and health care in Victorian England, Susannah Morris (2000) raised this issue. For example, companies constructed social housing on a commercial basis, paying investors dividends, but pursued a fundamentally social mission. Because such organizations would fail a core criterion of the nondistribution constraint, a temporal application of the structural operational definition would lead to a distorted view of the Victorian (quasi) nonprofit sector. Morris accordingly questioned the viability of any conclusions drawn from empirical work based on the CNP definition.

However, the CNP definition’s inability to take historical shifts into account is not necessarily a shortcoming. The CNP definition was first and foremost designed to measure the current economic scale of the nonprofit sector, and to enable cross-national comparisons.10 Variations in scale and composition of the sector at any given point in time are a baseline for assessing larger institutional shifts in the conception of public and private responsibilities and the resulting interplay of the public, market, and nonprofit sectors. For example, in some places, cooperatives and mutuals remain more firmly in the nonprofit realm of solidarity and mutual help, whereas elsewhere they have largely become heavily commercialized and transitioned into the market. The emergence of social enterprise is another sector-straddling phenomenon, where an application of the CNP definition can lay bare different choices in the way that the public and the private are balanced in different contexts.

Yet to gain a better understanding of the field, in particular in view of theory development, it may be time to look at the state, market, and civil society adjacent and their relationships with the nonprofit sector.11 These factors, in turn, are closely related to the functions that researchers like Ralph M. Kramer (1981, 1987) and others have long associated with nonprofit forms:

• Service provider role, often as nonprofit corporations: these organizations take on or complement services offered by government and businesses. They often cater to minority demands and provide trust goods (high information asymmetries and high transaction costs), thereby achieving an overall more optimal level of supply.

• Vanguard role, typically as nonprofit corporations and foundations: as mentioned before, these are less beholden than businesses to owner expectations of return of investment and are not subject to the exigencies of shorter-term political success. They are closer to the front lines of many social problems and, because they can take risks and experiment, they foster innovation in service provision and increase the problem-solving capacity of society as a whole.

• Value-guardian role, as product bundling service providers, but also as associations and foundations: these organizations help express different values (religious, ideological, cultural, etc.) across a population and within particular groups when governments are constrained by either majority will or autocratically set preferences. They thereby contribute to cultural diversity and ease potential tensions.

• Advocacy role, mostly as associations but also as foundations: when governments fail to serve all members of the population equally well, and when prevailing interests and social structures disadvantage certain groups while giving unjust preference to others, nonprofits can serve as public critics and become advocates. They thereby give voice to grievances, reduce conflict, and possibly create policy change.

In other words, we propose that a future research agenda revisit the question of definition. We suggest this not to advocate for the replacement of the structural-operational definition, but in order to enshrine functions or objectives as crucial factors that set nonprofits apart from both governmental agencies and businesses (Toepler and Anheier 2004). The new question that orients research would be this: what organizational forms, based in what institutional sectors, provide quasi-public goods and services and act as vanguards, value-guardians, and advocates? Such questions will lead researchers to examine the interfaces between the nonprofit sector and the state, market, and civil society, including hybrid forms.

Classifying Nonprofit Activities

There is also the issue of the classification of nonprofit activities. Available national and international classifications of economic activities from the SNA12 lump many nonprofit activities into few general categories; they do not provide the specificity needed for measuring sector composition. Bespoke classification systems like the American National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE) prove too country-specific (Salamon and Anheier 1997). In response, CNP developed the International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations, or ICNPO (Salamon and Anheier 1992b). This system was used to show the distribution of employment, expenditure, and revenue data, with the goal of measuring the composition of nonprofit sectors internationally (see Salamon et al. 1999).

Figure 30.4 Nonprofit sector workforce, paid vs. volunteers, in 22 countries by field of expenditure

Source: Based on data reported in Salamon et al. 1999, pp. 478–482.

The ICNPO follows the classification guidelines of SNA-related systems. It is based on the majority expenditure rule, according to which the activity that accounts for the largest share of an entity’s total operating expenditures determines its classification (Salamon and Anheier 1992b). For example, a nonprofit entity spending 51 percent of its operating budget on providing social services, 40 percent on housing, and 9 percent on advocacy would be classified under “social services.” Hence, the ICNPO is an expenditure-based system, not an activity-based one. Consequently, it likely overemphasizes the three fields that make up about two thirds of total nonprofit sector spending: education, social services, and health care (see Figure 30.4). At the same time, it probably downplays activities that are less expenditures intensive, like advocacy, culture, environment, and philanthropy. In other words, service-providing nonprofit corporations that are engaged in endeavors that require large expenditures dominate the resulting measurement of the sector composition, while other activities in fields disproportionately populated with less service-focused nonprofits, including associations and foundations (most of them without employment), figure less prominently.

Figure 30.4 shows the distribution of nonprofit activity across different fields. The graph distinguishes between paid and volunteer work with dark and light gray bars. The dark gray bars indicate that expenditure-intensive fields like education and research, health, and social services make up the largest share of paid nonprofit activity (68 percent); all other fields make up only 31 percent. The light gray bars include the estimates for the substitution value of volunteer activity. Expenditure on culture, which mostly consists of recreational activities and amateur sports, turns out to be substantially higher with volunteers included (25 percent) than without (14 percent).

Two aspects of this graph are relevant for future research. First, given its emphasis on employment, which concentrates in education, health care, and social services, the picture of the nonprofit sector that emerges seems like a close approximation of the welfare regimes of a given country, and hence its level of economic and institutional development. This points to the importance of nonprofit corporations and their regulation and governance, as entities in these three fields (e.g., schools, universities, hospitals, homes for the elderly) are typically larger and capital- as well as labor-intensive. We will return to the implication of this finding when we consider the possibility that variations in nonprofit sector size and composition reflect broader social, economic, and political forces.

Second, as a result of the SNA rule, the ICNPO’s classifications subordinate an organization’s secondary activities to its primary one. Clearly, this can introduce distortions. For example, a nonprofit that provides mostly social services but also some health care and advocacy would have all of its expenditures classified under “social services.” In the SNA, this is a well-known problem. It is tolerated because multiproduct corporations that reach sufficient size tend to split off into separate entities, which are then classified individually.

However, in the case of nonprofit organizations, product bundling is not only common but close to their very raison d’etre. The primary expenditure rule therefore poses a major conceptual problem, since it disregards product bundling and co-production. This oversight makes it impossible to test a core facet of both nonprofit theorizing (James 1987; Weisbrod 1988) and the rationale for the existence of these organizations in market economies.

A future research agenda could correct these shortcomings by extending the classification of nonprofit activities. As with the CNP definition, the proposal here is not to replace the ICNPO, as it represents a crucial tool for measuring the economic size and composition of the sector following SNA rules. Rather, the goal would be to develop activity measures that combine service delivery with other functions. These would complement the current expenditure approach for measuring the nonprofit sector. Ideally, a conceptually grounded and extended classification system would mirror the functions of nonprofit organizations mentioned earlier.13

Definitions and classifications serve descriptive purposes, yet their main task is to assist in building theories that enhance our understanding of differences among nonprofit sectors around the world. Indeed, using the nation-state as the unit of analysis, CNP developed a much-needed infrastructure for this project.

The social origin theory, initially proposed by Lester M. Salamon and Helmut K. Anheier (1998) and further developed by Anheier (2014:220–223) and by Salamon and his colleagues (2017), remains the main outcome of CNP theory building. It explains the size of a given nonprofit sector by emphasizing the factors responsible for variations in workforce size and its revenue base. The core idea behind this approach is that these variations can be traced back to the institutional embeddedness of the nonprofit sector in familial and community structures, as well as religious, political, and economic systems. Speaking broadly, the decisions of individuals and nonprofit entrepreneurs to rely on the market, the state, or the nonprofit sector for quasi-public goods and services is necessarily influenced by pre-existing supply and demand conditions. These reflect existing power constellations within state–society relations.

Unlike the more microeconomic theories mentioned earlier, the social-origin approach is comparative-historical in nature. It views the nonprofit sector today as a product of past conditions and developments. Rather than having just one deciding factor (e.g., degree of heterogeneity), the theory lays out diverse institutional trajectories that account for cross-national variations among nonprofit sectors. For example, some countries have relatively large nonprofit sectors because their governments pay for a substantial share of the services nonprofits provide. Under these circumstances, the nonprofit sector either could be the extension of a government seeking to limit its active role in service-provision (e.g., Britain) or could be powerful enough to extract significant funds from government (e.g., Germany). Other countries may have large nonprofit sectors because governments spend fairly little on welfare programs (United States), and nonprofit organizations rely on fees and charges rather than government subsidies. By contrast, countries with smaller nonprofit sectors may have a government that delivers adequate quasi-public services directly (e.g., Sweden), or a government that does not but nonetheless restricts nonprofit activities (e.g., Russia).

According to the social origin theory, such outcomes are the result of complex developments stemming from long-term social and cultural “moorings,” as well as conflicts and their settlements among a range of actors and groups with varying power. These might include governments and state authorities, landed elites, urban middle classes, professions, peasants, working-class movements, organized religions, colonial administrations, among others. Even though the outcomes of the interaction of these factors can seem random and context-specific at times, overarching patterns emerge. These invite theoretical expectations that can be further refined (see the discussion of clustering later in this chapter).

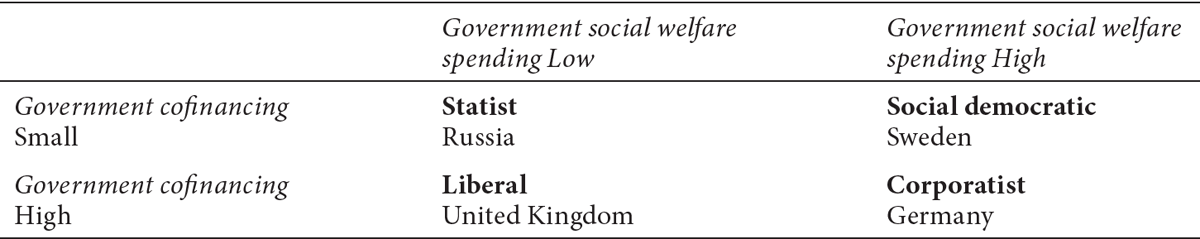

In short, origin theory assumes that long-term constellations among actors and groups shape nonprofit sector scale, scope, and institutional embeddedness (Table 30.1). This approach focuses on the longue durée to examine change along two dimensions: the extent to which governments spend directly on the kinds of activities nonprofits provide (i.e., the direct substitution pattern), and the degree to which governments cofinance the nonprofit sector (i.e., the third-party government or complementarity pattern). These two dimensions can be expanded by a fourfold classification system of nonprofit regime types (Table 30.2), drawing on a welfare typology constructed by Gøsta Esping-Andersen (1990):

• In the liberal type, represented by the United Kingdom, a lower level of government social welfare spending is associated with a relatively high degree of government cofinancing of the nonprofit sector.

• The social democratic type is very much located at the opposite extreme. In this model, exemplified by Sweden, state-sponsored and -delivered social welfare protections are extensive; the room left for service-providing nonprofit organizations is therefore quite constrained.

• In between these two types are two additional ones, both of which are characterized by strong states:

• In the corporatist type, represented by France and Germany, the expanding welfare state has been induced to make common cause with powerful nonprofit institutions linked to established religious and political interests. As a result, the state pays for a significant share of nonprofit service-delivery expenditures.

• In the statist type, the state retains the upper hand in a wide range of social policies. It exercises power on its own behalf, or on behalf of business and economic elites. In such settings—historically Japan has been an example, as are present-day Russia and Mexico—limited government social welfare programs do not translate into high levels of government cofinanced nonprofit activity, as in liberal regimes. Rather, both government welfare initiatives and government sponsorship of nonprofits remain highly constrained.

Advancing the social origins approach beyond its initial formulation requires three steps. The first of these is a proposed conceptual typology with countries grouped under one of the four regime types (Tables 30.1 and 30.2). The second is employing model-based clustering, as suggested by John S. Ahlquist and Christian Breunig (2012), to identify the existence of the regime typology in “the real world” using CNP data. Typology conformation, however, is an intermediate step. The third task, therefore, is to link country clusters corresponding to the four regime types to different characteristics of the social moorings: the role of elites, class relations and social divisions, the power of religions, the strength of various political ideologies, and so on.

Such a recursive approach to theory construction brings up several fundamental issues. First, because of the long time frame and complexity of the factors it identifies as important, the social origins theory is difficult to test empirically. This difficulty is of a different sort than the economic theories mentioned earlier. The social origins theory lacks the parsimony of economic theories and calls for difficult qualitative judgments about the relative power of broad social groups, actors, and ideologies over time. Moreover, the focus on the longue durée of social moorings entails a certain imprecision in determining which historical factors shape the present and which do not.

Table 30.1 Nonprofit sector size and government social spending

Source: Adapted from Anheier 2014; Salamon and Anheier 1998.

Table 30.2 Government social spending and government cofinancing of the nonprofit sector

Source: Adapted from Anheier 2014; Salamon and Anheier 1998.

Second, model-based clustering of countries does not necessarily lead to empirical results that fall neatly into one regime type or another (Ahlquist and Breunig 2012; Breunig and Ahlquist 2014). If this is the case, the clusters have to be reevaluated to find out why the expected types cannot be found, and why countries do not match. That said, model-based clustering is less likely to generate fewer diverging clusters than explorative and descriptive methods. Yet it cannot relieve researchers from the task of interpreting the identified clusters and checking the reliability of the variables and samples chosen.

Third, we should recall that the CNP definition measures nonprofits divorced from their institutional environment. In allocating countries to a particular regime type, however, social origins theory brings in institutional factors rooted in a country’s social moorings and its broader historical development. In other words, it imputes institutional meaning. For example, the three principles of subsidiarity, self-administration, and communal economy are employed to make a case for the corporatist nature of Germany’s nonprofit sector. Yet these principles are responsible for only limited segments of the sector as delineated by CNP and the ICNPO: social services in the case of subsidiarity, professional associations and chambers when it comes to self-administration, and housing for the communal economy. The other segments of the sector are not implicated, but organizational forms outside the scope of the CNP definition are quangos and their many variants in the case of self-administration, and cooperative societies and mutual associations in the case of the communal economy (see Figure 30.3).

France, too, is classified as corporatist, but the social foundations of its nonprofit sector are completely different from the German case. They include the long-term impact of Jacobine ideology, the workers’ movement, and late-twentieth-century associationism. From a comparative perspective, this suggests that the characteristics of the social moorings are neither necessary nor sufficient across cases, and that they reflect developments specific to a country rather than more general factors associated with the nonprofit regime type in question. In other words, we have a proposed typology (Tables 30.1 and 30.2) but no systematic and parsimonious set of factors associated with particular regime types.

Fourth, the social origins theory can lead to a certain circularity. France, as a corporatist country, developed a corporatist nonprofit sector; Sweden, as a social democratic country, established a social democratic one. But is France corporatist because of its nonprofit sector, or vice versa? Is Sweden social democratic because of its nonprofit sector, or vice versa? In other words, the explanation for grouping countries under particular nonprofit regime types would have to stress the larger institutional forces and patterns that made the French and Swedish nonprofit sectors what they are.

For example, Dag Wollebæk and Per Selle (2008; Selle and Wollebæk 2010) doubt the existence of a social-democratic nonprofit regime. Using the case of Norway, they argue that the institutional characteristics of Scandinavian nonprofit sectors existed long before the emergence of social democracy. Associating the contours of the sector with a social-democratic regime masks key factors of the longue durée, such as historically strong linkages between the local and the national level, the close association between volunteering and organizational membership, and the role of Protestant churches. Together, these factors account for the unique nature of the Scandinavian nonprofit experience.

Fifth, perhaps because Salamon and Anheier (1998) introduced the social origins theory as a heuristic that neither explicitly addresses causality nor clearly identifies its central variables, its applications are too varied for a systematic assessment. Table 30.3 lists over twenty studies applying the social origins theory that have been published between 2000 and 2018. Some studies use the four nonprofit regime types as a dependent variable (explanandum), some as the independent variable (explanans), and for others the explanatory positioning seems unclear. Some studies are qualitative case studies of specific countries, while others employ cross-national quantitative data. Seok Eun Kim and You Hyun Kim (2016) offer the most comprehensive quantitative study to date, yet they use a different dependent variable (a size variable based on SNA and not CNP data) and a different independent variable (government social protection spending instead of government social spending).14 Generally, the studies reveal a great diversity in the operationalization of characteristics and factors associated with the social moorings and developments involved.

In essence, the social origins theory faces challenges that are common to comparative-historical approaches that track long-term institutional shifts to make causal inferences about the present. In many instances, co-evolutionary patterns are at work over the longue durée (Mahoney and Thelen 2010). Sometimes these are triggered or taken into a different direction by epoch-making events, critical junctures, or less fundamental but nonetheless influential developments. So when Wollebæk and Selle (2008) question the applicability of the social democratic model to Norway, they are pointing to co-evolution. James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen’s (2010) insight was that institutions, once created, do not only change in subtle, gradual ways; they also influence adjacent institutions and organizational fields. Their idea applies to the nonprofit sector as well. Wollebæk and Selle (2008), for instance, point to global trends such as individualization and marketization that have begun to reduce the uniqueness of the Scandinavian model through the gradual and subtle ways Mahoney and Thelen (2010) suggest.

These reflections ultimately challenge the explanatory power of regime theories generally. Is the U.S. nonprofit sector a liberal regime because of factors specific to its development as part of American society, or because the United States is a liberal market economy, or because American society is prototypical of a more general Western pattern of modernity with a high degree of individualism and a preference of self-organization over state authority? Could it be that all three somehow apply, and along complex lines suggested by co-evolution? So it should not surprise us that two central features of the social origins theory remain an open issue more than two decades after it was introduced. The first is whether the discernible clusters of countries that the theory supposes can actually be found. The second is whether an emphasis on sector moorings has led to parsimonious sets of explanatory factors that vary more across regime types than within them, and that show idiosyncratic, regime-specific combinations.

What is more, we should expect such a clustering to reveal more than a split between developed economies on the one hand and developing or transition ones on the other. Otherwise, variations would be the result of different levels of economic development (note that in Figure 30.1 most countries with small nonprofit sectors were less-developed countries or transitioning at the time). Results should also show clusters other than those based on the varieties-of-capitalism approach (Hall and Soskice 2001); we see in Figure 30.1 that most of the countries with a large nonprofit sector are coordinated market economies. Clearly, because the social origin theory covers complex explanatory terrain, it has set itself the difficult task of finding patterns and structures that other theories and typologies tend to ignore.

Clustering

Figure 30.5 presents results from model-based clustering for forty-one countries using the variables “government social spending” and “government cofinancing of the nonprofit sector.”15 The model that best fits the most recent CNP data identifies three components with different variance and ellipselike shapes.16 Roughly speaking, the shapes indicate the reliability of the identified clusters. For instance, one can be rather certain that Mexico (MEX) is part of a different cluster than the United States (USA) given that both countries are placed within different shapes. The placement of Austria (AUT) and Hungary (HUN) in the same cluster as the United States (USA)—as indicated by the triangular symbols—is, by contrast, less certain. Slight changes might lead to the placement of Austria (AUT) and Hungary (HUN) in the same cluster as the Czech Republic (CZE). The shapes are thus used to illustrate the underlying model’s certainty about key clusters, whereas the circular, triangular, and square symbols denote general cluster memberships.

Alternately, Figure 30.5 uses a scatterplot to plot the variable government social spending against government cofinancing of the nonprofit sector using most recent CNP data (Salamon et al. 2017:276–279). The data points of France and Germany, for example, are close together because the two chosen variables have similar values for both countries.

The first clustering suggests two main findings. First, there seem to be only three clusters, with the social democratic one missing. Second, many countries are in between clusters.

Specifically:

• The countries expected to fall into the statist cluster, such as Russia and Mexico, clearly appear to cluster together. Japan is nowadays outside this cluster, as suggested earlier. All countries in the statist cluster are characterized by low government social spending and low cofinancing of the nonprofit sector.

• The second cluster, by contrast, groups countries expected to fall within liberal and social democratic clusters. Although the United States, as a prototypical liberal country, is grouped with Australia as predicted, it also shares the same cluster as the typically social democratic Norway. Even though the placements of other social democratic countries such as Sweden and Denmark are less clear, these countries are grouped surprisingly close to liberal ones. Government social spending is visibly higher in Norway than in the United States. Still, using government cofinancing of the nonprofit sector as a second measure, the United States and Norway are closer than the United States and Mexico, or Norway and Mexico.

• The third cluster contains European countries that have traditionally been described as corporatist, with high government social spending and high cofinancing of the nonprofit sector.

Figure 30.5 Model-based clustering of nonprofit sectors

Source: Based on data reported in Salamon, Sokolowski, and Haddock 2017. pp. 276–279.

Note: Figure uses ISO3 country abbreviations. See table 30.4 for further details.

Although this three-cluster model best suits the data, there are several models with one to five components that are not considerably worse in terms of fit. One way to respond to difficulties in the identification of clusters is to refine theory building and to assemble data that contain more clustering information. This is what Salamon and his colleagues (2017) attempted by adding a fifth type to the social origins typology: the traditional type. According to Salamon and his colleagues (2017:84–85), this type is characterized by a large number of volunteers and an equally large amount of revenue contributed by philanthropy. In other words, Salamon and his colleagues (2017) argue that the statist type really consists of two types: the original statist type described earlier, and the new traditional type associated with countries like the Philippines and Peru. Table 30.4 lists all countries by hypothesized clusters.

The clustering in Figure 30.5 suggests that Salamon and his colleagues (2017) have a point: a number of countries at the lower end of the statist cluster are grouped very closely together. They expect those countries to form a cluster because they do not just have low levels of government social spending and cofinancing of the nonprofit sector but also depend to a larger extent than traditional statist countries on volunteers and philanthropic giving. To demonstrate the value of the expanded typology, they introduce two additional variables: “volunteer share of the nonprofit workforce” and the “philanthropy share of nonprofit revenue.”

Figure 30.6 Model-based clustering using an expended set of variables

Note: Figure uses ISO3 country abbreviations. See table 30.4 for further details.

Source: Data reported in Salamon, Sokolowski, and Haddock 2017, pp. 276–279.

Will we find five clusters if we rely on more measures than government social spending and cofinancing of the nonprofit sector? Figure 30.6 shows the results from model-based clustering using the same measures from Figure 30.5 plus measures for the volunteer share of the nonprofit workforce and the philanthropy share of nonprofit revenue. The model with the best fit for the extended dataset identifies two components with differing variance and ellipsoidal shape. In order to facilitate comparison between both plots, we use the same plot as in Figure 30.5 but add updated cluster information.

The statist cluster does look different from the previous model, yet not in the expected way. Countries such as Korea (KOR) and Tanzania (TZA) are now placed in the statist cluster, whereas the Philippines (PHL) and Peru (PER) do not appear in a new cluster. Interestingly, the selected model no longer distinguishes between the social democratic, liberal, and corporatist clusters. Instead, it suggests a two-cluster solution that could be interpreted as a split between a statist and a nonstatist cluster. Just as with the previous three-cluster model, we cannot claim that the two-cluster model is substantially better than possible alternatives: models ranging from one to four components are not far off.17

Note that the identification of cluster groupings is not the same as a test of the social origin theory. To test whether the social origin theory can account for variations in the size of different nonprofit sectors, we would first of all have to find clearer groupings. Then we would have to design appropriate measures for the factors with which the theory is concerned: the influence of governments and state authorities, landed elites, urban middle classes, and so on. The task would also involve accounting for settlements between these social actors on regime types, and of regime types on nonprofit sector size. Unfortunately, this will only be possible once comprehensive time series data are available.

The model-based clustering solutions we have presented thus far do suggest, however, that theory building based on regime typologies could be approached from a different angle. Instead of drawing distinctions among ever more fine-grained types and subtypes of nonprofit regimes, both case study researchers and quantitative analysts in the social origin tradition might profit from pondering the question of whether there are actual constraints on theoretical generalization. For instance, can we really claim that differences in volunteering and philanthropic giving are large enough to set the nonprofit sectors of countries apart? Or are such differences likely to disappear when economic development increases or other macro factors change?

What is more, why are the nonprofit sectors of countries with growth trajectories like those of Korea, Russia, and Mexico still substantially different from countries with similar levels of economic development in Europe? It might be that two underlying and consistent clusters emerge. The first would be a cluster of countries where family- and kinship-based networks and autocratic conventions result in lower capacities for self-organization; the second would be a cluster with more “organized democratic publics” (Dewey 1927:98–100), whose ability to form institutions across society is relatively more pronounced. Within these two clusters, different histories of power struggles among social groups become “encoded” in the cultural and structural memory of a given society (Abbott 2016:13–14). Such struggles appear to be akin to the more political dimensions of the civil society concept. Thus we argue that an important step in extending the social origin theory is to tie it more closely to civil society research.

Enter Civil Society

What is civil society, and how does it differ from the nonprofit sector? Clearly, like the nonprofit sector, civil society is at some level an ensemble of many different kinds of organizations, ranging from small community-based associations to large international NGOs like Amnesty International or Greenpeace. But it is more than that. What separates civil society and the nonprofit sector is less what organizations fall under which category than the location of each within the wider society (see Figure 30.1). This implies that the two are differentiated by functions, such as interest mediation and advocacy, as well as individual behaviors, such as civility, civic engagement, and participation in society. Civil society is an arena for the self-organization of citizens and established interests seeking voice and influence, as two prominent definitions by Ernest Gellner (1994) and Keane (1998) make clear.

Located between the state and the market, civil society, according to Gellner (1994:5), is a “set of non-governmental institutions, which is strong enough to counter-balance the state, and, whilst not preventing the state from fulfilling its role of keeper of peace and arbitrator between major interests, can, nevertheless, prevent the state from dominating and atomizing the rest of society.” These institutions may not necessarily be organized. Rather, they express themselves through individual behaviors and value dispositions as well as cultural traditions. Charity, the rule of law, civility, and civic mindedness are institutions, but they may not manifest themselves in a distinct organizational form.

On the other hand, the organizational form that most closely fosters the ideal civil society of the neo-Tocquevillean tradition (e.g., Putnam 1994, 2000), which places importance on creating trusting relations among people, is the membership association. Through the facilitation of face-to-face interactions among individuals, associations serve as the schools of democracy imagined by Alexis de Tocqueville (2003) and Robert Putnam’s creators of trust and norms of reciprocity. Earlier we suggested incorporating the three main forms that nonprofits typically take into definitional approaches. This also has considerable bearings here, as nonprofit corporations and foundations may be less conducive to creating trust and the norms and democratic practices often associated with civil society. Although philanthropic foundations can leverage their grantmaking to support citizen associations and convene communities, the role of nonprofit corporations in the neo-Tocquevillean perspective is less clear. Rightly or wrongly, Putnam (2000) accordingly did not see the post–World War II rise of the nonprofit sector as contradicting his claim of a decline of social capital, the analysis of which was based on mass membership associations rather than corporate nonprofit service providers.

For Keane (1998:6), civil society is an “ensemble of legally protected non-governmental institutions that tend to be non-violent, self-organizing, self-reflexive, and permanently in tension with each other and with the state institutions that ‘frame,’ constrict and enable their activities.” Taken together, civil society expresses the societal capacity for self-organization and the potential for the contested but ultimately peaceful settlement of divergent private interests. Civil society for Keane is therefore a broader notion. It is less about delivering a service or organizations and more about how to advance causes that may or may not be deemed as in the public benefit by particular governments, political parties, and businesses and nonprofits. Yet self-organization certainly doesn’t preclude service provision. For example, voluntary associations engaged in mutual support activities over time develop increasingly professionalized services.

However we define the term, merging the nonprofit and civil society research agendas could get in the way of greater conceptual clarity and hinder theory construction. At the same time, both are concerned with questions around the functions of advocacy and value guardianship in particular. What is more, some of the more significant contemporary research trends in the field suggest a growing intersection. More specifically, civil society is arguably under significant threats from two sides. First, many scholars, as well as policy makers and funders, are increasingly concerned about the “closing space” for civil society internationally. This circumscribes the tendency of mostly authoritarian-leaning governments to restrict the more political, claims-making parts of civil society, primarily composed of human rights, democratization, and environmental advocacy NGOs that seek the promotion of (Western) values, often with substantial international donor support (Christensen and Weinstein 2013; Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014; Carothers 2015; Rutzen 2015; Dupuy, Ron, and Prakash 2016; Poppe and Wolff 2017; Dupuy and Prakash, Chapter 28, “Global Backlash Against Foreign Funding to Domestic Nongovernmental Organizations”).

However, there has been a growing sense recently that the space for civil society may be changing rather than closing entirely (Alscher et al. 2017; Anheier, Lang, and Toepler 2019). Space is constricting for certain advocacy organizations but expanding for others. As we mentioned earlier, democratic and authoritarian governments alike are attempting to build relationships with more apolitical parts of nonprofit sectors in efforts to improve the quality and availability of public services (Salamon and Toepler 2015). The push to involve nonprofits into social service contracting has come into view in countries like China (Teets 2014; Zhao, Wu, and Tao 2016) and Russia (Benevolenski and Toepler 2017; Skokova, Pape, and Krasnopolskaya 2018), raising significant concerns about governmental co-optation and reduced self-organization of society. This shift suggests that the relationship and balance between civil society and the nonprofit sector is changing.

Within this changing space, the second threat emerges: a marketization of civil society. As Keane (2005) reminded us, the philosophical development of the concept of civil society in the eighteenth century inexorably linked it to the market. In the post-1989 revival of the idea, however, a “purist” view of civil society took hold that separated it entirely from the market and market influences. Instead, it focused on civil society’s democratization potential and its protective function against both state and market excesses. With the rise of neoliberalism, Keane (2005:27) maintains that “market presumptions” have nevertheless tacitly infiltrated civil society thinking. Putnam-style, neo-Tocquevillean arguments buttressed the notion that a strong civil society leads to better economic performance and governance (Lewis 2014). From this perspective, civil society improves markets and creates good governance by building the trust that functioning markets require; however, other views on civil society take a more critical perspective, arguing that “markets and civil society are structured by mutually exclusive logics” (Keane 2005:27).

Analysts following the latter perspective perceive nonprofits not as constitutive of, but as significant contributors to, civil society development and democracy. Nonprofits do so through the fulfillment of Kramer’s four functions (1987), discussed earlier. Their ability to perform these functions is potentially undermined by marketization that derives from market incentives and practices being pushed on them through New Public Management and similar neoliberal government reform measures (Eikenberry and Kluver 2004; Yu and Chen 2018). As the social contracting space is widening, even in otherwise restrictive political regimes, civil society faces the risk of losing the core functions that nonprofits contribute—although, as Jianxing Yu and Keijian Chen (2018) caution, the dynamics of this change may play out differently in non-Western contexts.

Whether the marketization concerns of nonprofit researchers closely correlate with the co-optation concerns of civil society researchers remains to be seen, but it is clear that the “changing space” for civil society is an area where the research agendas overlap. A comparative research focus on the expressive dimension and the functions of nonprofits is significant here in both nonprofit and civil society research, but it is also important to differentiate among the main nonprofit forms in this respect. The associations of individual citizens banding together in the Tocquevillean notion of civil society may cause political difficulties for the state when they act as value guardians or advocates, thereby risking the contraction of their space. But there are no serious concerns about marketization because service delivery is typically not the core function of these organizations.18

In hybrid and authoritarian regimes, it is typically membership groups engaging in advocacy on rights issues that are the target of repressive state action (e.g., Daucé 2014). However, membership often remains too small to support sustained advocacy efforts at the national level, which creates dependencies on foreign donors that make cutting off international support a key element of the authoritarian suppression of NGOs (see Dupuy and Prakash, Chapter 28, “Global Backlash Against Foreign Funding to Domestic Nongovernmental Organizations”). Although some of these organizations were able to survive in Russia through regional support networks, the forced withdrawal of foreign funds virtually wiped out rights-based NGOs in some parts of the country (Toepler et al. 2019). As membership associations are classically subject to the free rider problem (Olson 1965), funding is a perennial concern for these organizations independent of the political environment in which they operate. The so-called NGOization concern from the social movement literature (Choudry and Kapoor 2013) also applies to associative civil society, as public and private donors prefer to support discreet services rather than advocacy. Another concern for associations is declining membership and active involvement due to individualization trends and the emergence of social media that allow participation in advocacy activity without necessarily corresponding organizational participation (Guo and Saxton 2014; Mosley, Weiner-Davis, and Anasti forthcoming).

By contrast, marketization is an issue of primary importance for the nonprofit corporations that are benefiting from the quickly expanding space for social service contracting in authoritarian countries. Besides religious organizations, the charitable part of the U.S. nonprofit sector is heavily dominated by the corporate form. In Europe, social service providers that historically had the legal form of association converted to corporation/company status, for reasons having to do with liability and expedience in decision making. But in doing so, nonprofits run the risk of losing some of their unique features, such as their value base. Research efforts could therefore usefully focus on identifying opportunities to imbue more of a civil ethos into the delivery of nonprofit services through the leveraging of street-level service delivery expertise. Ideally, this would allow for an increase in political voice and the public contestation of values.

For foundations, the situation is different still. Endowment assets insulate foundations economically from market pressures, but these organizations are not immune from political ones (Toepler 2018a). As quasi-autonomous institutions not accountable to voters, members, or clients, their difficult fit into liberal democratic societies has long been noted (Nielsen 1972; Prewitt 2006), which poses significant questions about their basic democratic legitimacy (Heydemann and Toepler 2006). Accordingly, much research has focused on exploring core foundation roles as a justification of the privileges afforded to them, including innovation, social change, preservation, and complementing or substituting for the state (Anheier and Toepler 1999; Anheier and Daly 2007; Anheier and Hammack 2010; Hammack and Anheier 2013; Anheier 2018). Partly in response to incentives created by government eager to mobilize private resources for public purposes, and partly in response to the creation of new wealth, foundations have begun to proliferate over the past three decades in most parts of the world (Toepler 2018b). At the same time, concerns about elite control over public agendas, the ability of these institutions to address social inequality, and the effects of their administration of social functions have also been proliferating (Anheier and Leat 2018; Anheier, Leat, and Toepler 2018).