1

Before and Surrounding Structuralism

Structuralism has undoubtedly offered the most popular theory of narrative. It was able to build on an age-old tradition, a lot of which it rejected. Yet structuralism also held on to a number of classical concepts, some of which we will explain in this chapter. In the course of these explanations we will also present a few more recent theories that do not really belong to the structuralist canon but that have made important contributions and have very often led to interesting discussions with structuralism. We do not aim to be exhaustive or, for that matter, to provide a history of narratology.1 Instead we mention only those theoreticians and concepts that still figure in narratological discussions.

1. Story and Plot

If narratology is the theory of the narrative text, then it should first offer a definition of narrative. Traditionally a narrative is considered to be a sequence of events. This formulation is highly problematic, and some of the problems it entails seem to defy solution. First of all, this definition simply shifts the problem in defining narrative to the equally problematic concept of “event.” Of what does the event in “Pegasian” consist? Rather than a narrative, isn’t this text perhaps a sketch or a scene?

Second, one could ask what kind of sequence of events appears in a narrative. Can we already speak of a narrative when one event follows the other in time? Or does the link between the events have to be stronger? For instance, does there have to be a link of cause and effect? In order to answer this question, the novelist and theoretician E. M. Forster introduced his famous distinction between story and plot. For the time being we will work with these two terms, but later on in this book we will replace plot with a pair of technical terms gleaned from structuralism: narrative and narration. According to Forster, story is the chronological sequence of events. Plot refers to the causal connection between those events. Forster provides the following example of a story: “The king died and then the queen died.” This sequence becomes a plot in the following sentence: “The king died and then the queen died of grief.”2

Unfortunately the distinction between temporal and causal connections is not always easy to make. Human beings apparently tend to interpret events succeeding each other in time as events with a causal connection. Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan quotes the following joke about Milton: “Milton wrote Paradise Lost, then his wife died, and then he wrote Paradise Regained.”3 The joke resides in the suggestion of an (unspoken) causal connection between the death of the wife and the rediscovery of paradise. The sequence seems chronological, but it has a causal dimension as well.

This means that the distinction between plot and story is by no means absolute. The example readily shows the importance of the reader, who interprets the sentence about Milton and thus turns the story into a plot. We do not reject the fundamental distinction between the two levels, but we want to make clear from the start that such a distinction comes down to a theoretical construct, which doesn’t tie in with concrete interpretations by actual readers. The sequence of events is always the work of the reader, who makes links between the story’s several incidents. This provides the plot with its dynamic, and it also gives rise to the idea that something is in fact happening. Just like the sequence of events, the event itself turns out to be dependent on the reader’s input. It is impossible to define an event in abstracto once and for all. What happens in “Pegasian”? A reader who approaches this text as we have in our introduction might say that quite a lot is happening here. There is a discussion between teacher and pupil about the correct way to ride a horse, followed by a double space and a resolution in which the question of who is right reveals itself to be less important than the fact that both characters use the horse to defy gravity. In “The Map” the events may seem more easily discernible—the acquisition of a map, the bike rides relative to it, and more generally the mapping of ordinary activities—but still, how the events are discerned will depend on the reader.

One may doubt whether meaningful connections that the reader makes between events can be reduced to causal connections. In “Pegasian,” although we do not see all that much cause and effect in the plot development, there is a meaningful transition from the discussion to the conclusion. It is a transition from dogmatism to relativism, from dressage or submission to freedom and takeoff. These connections are not causal, but they are significant and not merely chronological. A plot therefore depends not only on causal connections but on a wealth of relevant connections that transcend mere chronology and are always introduced by the reader.

If we consider plot to be an event sequence meaningful to the reader, then we still have to distinguish the narrative text from other genres. Does a newspaper article constitute a plot-driven narrative? Do nonlinguistic sign systems result in such narratives? Do movies, plays, comic strips, and video games all come down to this type of narrative? For us they do. We define plot-driven narrative as the representation of meaningfully related events. Such a representation can use any sign system, so for us Wasco’s “City” definitely amounts to a story.

This means we use a broad definition of narrative, one that is even broader than that proposed by Susana Onega and José Angel García Landa in their narratology reader. They say, “A narrative is the semiotic representation of a series of events meaningfully connected in a temporal and causal way.”4 In our view the last six words of this sentence can be dropped. For us, meaning in meaningfully related events cannot be reduced to temporality and causality. It results from the interaction between reader and text.

Since we extend temporal and causal links to meaningful connections at large, we deviate from the traditional view on the so-called minimal story—with “story” used here, contrary to Forster, in its general meaning as a synonym of narrative. The concept of the minimal story fits the structuralist search for the smallest units of a text. It has been developed to determine when one can speak of a narrative. If a character says, “Yes, I can come tomorrow,” does that mean we have a story? No, Gerald Prince says, since a story consists of at least three ingredients: an initial situation, an action or event, and an outcome.5 Connections must be temporal as well as causal. For instance, “John was happy, then he lost his girlfriend, and as a result he became unhappy.” Rimmon-Kenan criticizes Prince’s definition and submits that a temporal connection is sufficient to speak of a minimal story.6 For us, meaningful relations suffice, and they might even be metaphorical, metonymical, or thematic, as long as the reader considers them significant. “Yes, I can come tomorrow” does not amount to a narrative, because it does not connect events in any meaningful way. “He could not come then because he was ill” does constitute a narrative since it does make a meaningful connection between events. In this case the link is simply causal, but different links can also create a minimal story. “It was raining hard, in the streets as well as in his heart,” is a minimal story too, as it makes a significant metaphorical (or symbolic) link, and it does not imply causality or temporal sequence.

2. Telling and Showing

In order to avoid complicating the following discussion, we will temporarily assume that we can distinguish more or less easily between events and reality on the one hand and their narrative representation on the other. A narrative never provides a perfect copy of the reality constituting its subject. Persons who narrate what has happened to them will always summarize, expand, embellish, and leave out certain aspects of their experience. Since a narrative text always makes use of a sign system, it is always mediated and will never show reality directly. On the stage certain events can be shown, but this hardly applies to a novel. All this relates to the age-old distinction between what Plato called mimesis and diegesis.7

Mimesis evokes reality by staging it. This is evident in the theater, but narratives too have moments that tend toward mimetic representation, for instance, literally quoted conversations. In this case the narrative almost literally shows what was said in the reality evoked by the text, and yet a complete overlap between narrative representation and the “real” conversation is out of the question. Short phrases like “he said” already indicate an intervention by the narrator. Furthermore, chances are high that the time necessary for the reader to process the conversation in the text will not exactly coincide with the duration of the original conversation. The latter even applies when reading a text meant for the stage, which after all only approximates mimesis. There will probably be a major difference between the duration of the performance and the time necessary to read the text on which it was based.

Diegesis summarizes events and conversations. In such a summary the voice of the narrator will always come through. This voice colors narrated events, which are therefore no longer directly available. “The Map” recounts how the boy enters the store and asks about the enchanting map: “Monday afternoon, in the bookshop, I pointed to it. I did not have enough money, so that I had to wait until Saturday.” This summary probably covers an unreported conversation in which the shopkeeper mentions the price of the map, and the boy concludes he will need his next weekly allowance in order to buy it. The narrator summarizes this situation instead of showing it.

In the Anglo-American tradition before structuralism, the difference between diegesis and mimesis equals the difference between telling and showing, between summary and scene. In “The Art of Fiction” (1884) and other theoretical writings, Henry James established his preference for a narrator whom the reader can barely see or hear and who tries hard to show as much as possible.8 In The Craft of Fiction (1921) Percy Lubbock, under the influence of James’s novels, favored showing to telling.9 A mimetic novel usually contains a lot of action and dialogue. In strongly diegetic texts, on the other hand, narrators do come to the fore, so that they ostentatiously place themselves between the related scenes and the readers. In postmodern narratives narrators can behave in such an extremely diegetic way that readers starts to distrust them. So little is left of the original scene that you wonder whether the reported event actually took place.

Although mimesis and diegesis may look like a binary pair, they really constitute the two extremes of a continuum on which every narrative occupies a specific position. “Pegasian” appears more mimetic than “The Map,” not least because Charlotte Mutsaers shows conversation much more directly than Gerrit Krol and because the time of narration in the Mutsaers narrative adheres more closely to the duration of a scene than it does in Krol’s piece. In “The Map” long periods such as the one in which the main character bikes around are summarized in a few sentences. In “Pegasian” the original conversation between the riding master and the female rider remains almost untouched. However, the difference between the two narratives is far from absolute. In narrative prose there exists no such thing as pure mimesis or diegesis. Summaries always have their mimetic aspects, and mimetic representation always has moments of summary as well. This also holds for a graphic narrative like Wasco’s “City,” as the sequence of panels does not cover the two characters’ entire visit to the city.

This combination of mimesis and diegesis has been typical of the novel from its very beginnings. On the one hand the novel is a diegetic genre, and in that sense it forms the opposite of drama, an avowedly mimetic genre that dominated the literary system until at least the end of the eighteenth century. On the other hand novelists often defined their new art by pointing to the mimetic properties of their texts. Authors such as Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, and Jonathan Swift wrote introductions to their novels in which they presented their “new” way of telling as a form of the “old” showing. They paradoxically defended the trustworthiness and prestige of the new diegetic narration by calling upon its mimetic opposite. Whatever found its way into their books was not supposed to be an imaginary summary by a narrator but rather a truthful representation of scenes that actually happened. The tension between summary and scene is inherent in every form of narrative, and it remains central to any discussion of contemporary prose—witness, for instance, the recurring polemic about the combination of fact and fiction in autobiography.

3. Author and Narrator

It has become a commonplace that the author of a book must not be confused with its narrator. However, a total separation between these two agents proves inadequate. Autobiographical fiction, for instance, simply thrives on the close connection between its author, narrator, and main character.10 Occasional discussions about supposedly improper statements in fiction also prove that the theoretical separation between author and narrator does not remain clear in practice. Sometimes authors are even sued for statements made by their characters or narrators. This goes to show that the connection between author and narrator often plays out on the level of ideology.

Wayne Booth has provided a theoretical analysis of this connection in his book The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961), one of the first classics of narratology. A narrative text, Booth writes, is a form of communication, and therefore you always have a sender, a message, and a receiver. These three concepts do not simply translate into author, narrative, and reader. More communicative agents are involved. In his study Booth does not deal with the empirical author in any great detail, but he inserts three more agents between author and narrative, which we will discuss one by one.

The implied author does not actually appear in the text. Implied authors do not have an audible voice, and yet they may form part of a narrative. They constitute the source for the aggregate of norms and opinions that make up the ideology of the text. In other words, the implied author is responsible for the worldview emanating from a narrative. This view can be established in a variety of ways, for instance, on the basis of word choice, humor, and the manner in which characters are introduced. The implied author may have a different ideology than the characters or the narrator. Empirical authors may develop an implied author who is opposed to a specific worldview, but that does not prevent proponents of this ideology from speaking up in their novels. According to Booth, the distance between implied author and narrator offers an excellent criterion to test the latter’s reliability. The more the narrator’s statements resemble the implied author’s ideology, the more reliable the narrator will turn out to be.

This point about the proximity between the narrator and implied author does not hold. The implied author and the narrator’s reliability are not offered in the text itself, but instead they are construed by the reader. There exist no objective procedures to derive the implied author from a narrative. The importance of the reader for the construction of the implied author shows through in the alternative names proposed for it by other critics. Seymour Chatman prefers inferred author.11 Gérard Genette likes auteur induit.12 The degree of the narrator’s reliability is a subjective matter as well, which critically depends on the reader’s preconceived ideas about reliability and trustworthiness.13

As a construction, the implied author therefore depends on the reader and on the textual elements as they are interpreted by the reader. That turns the implied author into a paradoxical concept. On the one hand this implied author is supposed to be at the root of the norms and values in a text and in this way would give the reader direction. Chatman defines the implied author as the “agency within the narrative fiction itself which guides any reading of it.”14 On the other hand the implied author depends on how the reader handles the text. Ansgar Nünning correctly suggests that the location of the implied author in the communicative structure of fiction is very unclear. In theory implied authors occupy a position on the side of the sender since they connect to actual authors, but in practice any implied author amounts to a construction by the receiver (the reader), who makes use of the message (the text) in order to arrive at this construction.15 The exact position of the implied author remains vague. Nünning criticizes Chatman because the latter first says that the reader constructs the implied author and then lets this construction coincide with the text: “The text is itself the implied author.”16 Eventually Chatman combines reader and text in a definition of the implied author as “the patterns in the text which the reader negotiates.”17

Such a blurring of the borderlines between sender, message, and receiver is wasted on structuralist narratology, which attempts to separate these elements as strictly as possible. No wonder Genette opposes the concept of the implied author. He maintains the strict separation between the empirical author, who remains outside the text (and therefore also outside narratology), and the narrator, who belongs to the text (and to narratology). Genette considers an intermediate figure such as the implied author entirely superfluous.18 Opposites meet in connection with this issue. Antistructuralist theorists, who do not regard language as a formal network but rather as subjective expression, hold the same opinion as Genette. Peter Juhl, who studies literature on the basis of intention and expression, contends that a literary work can only say and mean something when readers and critics connect it with an empirical author who guarantees the seriousness and authenticity of the text. The real author must not be hidden behind an imaginary construction, since that would mean that statements in a text lose their value: “The propositions which a work expresses or implies are expressed or implied, not by a fictional ‘implied author,’ but by the real, historical person.”19

The concept of the implied author thus appears highly problematic. Narratology can function perfectly without using the term. Furthermore, a theory that does use it might degenerate into anthropomorphism (since the term humanizes an element allegedly pertaining to the text) and biographism (since readers and critics often enhance the implied author with elements from the author’s real life).20 Biographism is inherent in an approach like Juhl’s, which eventually reduces the implied author to the real author. We accept the implied author only as an intermediate position, that is, as a construction resulting mainly from the interaction between text and reader. The reader can consider the implied author to be a reflection of the real author, but both these authors in fact amount to constructions by the reader and so, obviously, does the reflection.21

Next to the implied author, who remains invisible in the text, Booth places the dramatized author, who does become visible. This is the traditional authorial narrator, whom we will also encounter in the theory developed by Franz Stanzel. Such narrators do not function as characters in the fictional world, since they hover over the narrative, but traditional authorial narrators do become visible through first-person narration. The dramatized author appears only as a narrator, not as a character. Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Masque of the Red Death” provides an excellent example. This story deals with a mass casualty incident within a fortified monastery as the result of a plague known as the “red death.” Not a single person survived, and so the narrator was not present as a witness either. Yet sometimes this narrator becomes visible as the agent in charge of narration: “It was a voluptuous scene, that masquerade. But let me first tell of the rooms in which it was held.”22

Booth also conceives of the dramatized narrator, who does appear in the story as a character. Such narrators take part in the scenes they describe, either as observers or as agents. Finally, undramatized narrators tell the story without being seen. They constantly show the action through the eyes of the characters so as to remain out of sight. They never use the first person, which distinguishes them from dramatized authors. “Pegasian” could be thought to sport an undramatized narrator who would then show us everything through the two main characters. “The Map” has a dramatized narrator who appears as an agent in the story, while telling the story.

Summing up, three agents may appear between author and text: the implied author, the dramatized author, and the narrator—dramatized or undramatized. This division implies both a hierarchy and a shift. The first agent sits closest to the author, while the last occupies the position closest to the text. In chapter 2 structuralist narratologists will prove very explicit about their preference for such neatly separated levels.

Even the most humble undramatized narrator still comes up with a certain amount of summary. Narrative never comes down to purely mimetic representation. A narrator is not absent when hardly noticeable. Visibility and presence are two different dimensions, and one of the biggest merits of structuralists such as Genette and Mieke Bal is the fact that they have pointed this out. Those who confuse invisibility and absence conflate two characteristics and end up with the erroneous view proposed by Chatman in his classic study, Story and Discourse (1978). He speaks of “nonnarrated stories” and proposes a quotation from a conversation or diary as an example of “nonnarrated representation.” According to Chatman, narrators are absent whenever they represent dialogues as a kind of stenographer or diary fragments as a kind of collector.23 In our view there is definitely still a narrator in these cases, although not one who is directly visible. We agree with Rimmon-Kenan, who contends that there is always a narrating agent, even in the representation of dialogues or written fragments. The agent who presents these elements to the reader may be invisible but cannot be absent.24 Chatman’s confusion of the two also shows through in the continuum he posits, which moves from absent narrators over covert narrators to overt narrators. The latter two concern visibility; the former deals with presence. By placing them on one line, Chatman denies the difference between the two dimensions.

4. Narrator and Reader

If a story forms part of a communicative situation in which a sender transmits a message to a receiver, then the latter must also be given some credit in narrative theory. The sender does not turn out to be one easily identifiable agent, and we will see that the receiver of a story does not simply add up to a monolithic entity in the guise of the reader either.

According to Wayne Booth, every text envisions a specific reader with a particular ideology and attitude. This reader forms the counterpart to the implied author, functioning as a second self. Just as the narrator’s reliability depends on the close ties between narrator and implied author, the reliability and the quality of reading depend on the similarity between the implied author’s ideology and the ideology of the reader: “The most successful reading is one in which the created selves, author and reader, can find complete agreement.”25 Booth does not use the term “implied reader” for this reader, but he borrows the concept of the mock reader proposed by Walker Gibson in 1950.26 In reception theory, however, the implied reader does appear, although it must be said that Wolfgang Iser’s definition of this concept hardly corresponds to Booth’s mock reader. For Iser the implied reader is the sum total of indications and signals in the text that direct the act of reading. Important indications can be found in passages resulting in a problem or mystery, the so-called gaps. Iser submits that in the course of its history literary prose has come to feature more and more of these gaps.27

Just like the implied author, the mock reader is an abstraction that cannot be heard or seen in the text. All the problems mentioned in connection with the implied author also apply here.28 Just like that counterpart, the mock reader occupies an intermediate position by being neither the concrete individual reading the text nor the agent explicitly addressed by the dramatized author or narrator. For this particular agent, narratology usually reserves the term narratee, a concept proposed by Gerald Prince.29

Just like the narrator, the narratee can be either dramatized or undramatized. In an epistolary novel the addressee of a letter often acts as a character in the narrative, but that is not really necessary. The undramatized narratee may stand either close to the mock reader or far removed. In the collection containing “Pegasian,” Charlotte Mutsaers also writes a “letter to [her] brother Pinocchio.” This letter, which starts with “Dear Pinocchio,” has an obvious narratee, but he never appears in the story and in that sense remains absent from it.30 A good understanding of the narratee therefore also requires a clear distinction between visibility and presence.

Every text has a narratee, even when she or he remains invisible. Neither “Pegasian” nor “The Map” exhibits an explicitly acting narratee, but the two stories are obviously addressed to someone. Just as there is always an agent of narration, there is also always a narratee. Here we deviate again from Chatman, who posits a non-narratee as the counterpart to his nonnarrator.31 We do agree with Chatman’s suggestion that narrator and narratee do not have to mirror each other when it comes to their visibility. A narrator who acts as a character does not have to address a similar narratee. The narrator-character in “The Map” does not address another character. Conversely, a narrator who does not act as a character may very well address specific characters, perhaps in order to scold or applaud them. In that case the narratee belongs to the universe of narrated events, whereas the narrator remains outside of it.

Two conclusions can be drawn. First, each side of the communicative spectrum in a narrative has its own specific agents. Second, these agents do not necessarily mirror each other. The implied author addresses the mock reader; dramatized authors and any dramatized or undramatized narrators address the narratee, who can exist on various levels. The narratee can belong to the narrative universe or hover above it like the dramatized author, as well as stand close to mock readers or very far from them.

The communicative situation of narrative can be schematized.32 Such a schema might look like this:

1. Narrator, narrative, narratee. Adapted from Wallace Martin, Recent Theories of Narrative (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1986), 154.

Classical structuralist narratology restricts the interaction between sender, message, and receiver to the agencies within the text: narrator, narrative, and narratee. This partly harks back to the Russian formalists, who opted for a strict separation between regular and literary communication. As we will make clear in chapter 3, the reader is central to postclassical narratology. But the author has made a sophisticated comeback as well, for instance in the work of Henrik Skov Nielsen, who claims “that the voice we hear in fiction is actually often the voice of the author and not the voice of a narrator.”33 In his effort to tie “narration more closely to its flesh-and-blood author,” Nielsen too rejects the idea of an implied author: “To realize the full potential of authors, we should ‘employ’ rather than ‘imply’ them.”34 Sylvie Patron studies narrative production as a form of enunciation in which “the author [is] the arch-enunciator, as in theatre, or more simply the narrative’s real subject of enunciation.”35 In this she aligns herself with Käte Hamburger, who has stated that third-person narratives are told by the “narrating poet” or “lyric poet,” not by a fictive narrator or by the biographical author.36 Author and reader are combined in the notion of “posture” developed by Jérôme Meizoz as a mixture of discursive and nondiscursive forms of self-presentation, as well as in the reader’s author image as proposed by Fotis Jannidis and Sandra Heinen.37

Calling upon speech act theory, Mary Louise Pratt argues that the separation between literature and everyday communication comes down to the “poetic language fallacy,” and she proposes to integrate the narrative communication of a literary text into the study of regular, day-to-day “natural narrative.”38 This proposal nicely conforms to speech act theory, which starts from the idea that every form of communication must be seen as an act, more specifically, as a contextual interaction between speaker and hearer. Only in a concrete situation do words get their meaning and can some statements exert coercive power. According to Pratt, the reader always considers the interaction between narrator, narrative, and narratee as a reflection of the “natural” communicative interaction between speaker, message, and hearer.39 The reader places literary narration into a larger context that provides conditions for successful communication, such as comprehensibility, honesty, and the belief in what is being said. To the degree that a literary text meets these requirements, it assumes an authority that allows its statements to be considered meaningful.40

Such an insistence on context has the advantage of showing which requirements must be met before a literary text can be recognized, understood, and analyzed. Structuralist narratology does not concern itself with these requirements, since it takes recognition and understanding for granted. It does not ask where they come from and how they become possible. Yet this shortsightedness enables the narratologist to analyze the building blocks and mechanisms of literary narration from up close without worrying about the larger, nonliterary context.

5. Consciousness and Speech

One of the crucial problems of narrative analysis concerns the ways in which the characters’ statements and thoughts appear in the text. In principle the difference between sentences that have actually been uttered and unspoken thoughts does not really matter.41 In both cases we are talking about ideas and emotions belonging to characters, which an actual conversation may of course render more clearly than an unspoken reflection. Characters who are actually speaking may have ordered their thoughts better than someone who is thinking or dreaming, but this does not always have to be the case. Conversations can be very tentative and chaotic, while a sequence of thoughts can be quite clear. We will indicate the evocation of both thoughts and conversations with the term representation of consciousness, and we will address this matter at length since it constitutes one of the major challenges to narrative theory.

The central problem of consciousness representation comes down to the relationship between the representing agent and the one who is being represented. If a narrator represents a character’s thoughts, one may ask to what extent this representation will be pure and authentic. The reader may think that he or she gets the character’s actual ideas, while in fact he or she may only get formulations and opinions belonging to the narrator, who paraphrases the ideas in question. We have mentioned this briefly in the introduction in connection with “Pegasian,” and at that point we distinguished three forms of representation: direct speech, indirect speech, and free indirect speech. We will now develop this division with the help of an authoritative study about consciousness representation in literary narrative: Transparent Minds (1978), by Dorrit Cohn.

Cohn distinguishes two kinds of consciousness representation, which imply two different relationships between narrator and character. First, narrators who represent consciousness can coincide with the character whose thoughts they represent, in which case the narrator most often uses the first person. Such narrators can possibly represent their ideas and feelings in the second person—for instance, when self-directing the comment, “You’re too slow; you’re getting old”—but in fact this “you” comes down to a split-off from the I-figure. Second, narrators who represent consciousness can differ from the character whose thoughts they represent, in which case they use the third person. The second person could be used here when the narrator addresses the character. “Pegasian” is narrated in the third person, and for this Cohn coins the phrase “third-person context.” “The Map” constitutes a first-person narrative, which Cohn refers to as a “first-person context.”

According to Cohn, third-person representation has no fewer than three types, which roughly correspond to indirect, direct, and free indirect speech. Cohn calls the first type psycho-narration. Here an omniscient narrator presents a character’s consciousness without literally quoting, as in, “He sincerely believed she would make him happy.” In psycho-narration the characters’ unconscious may be represented since the narrator has unrestricted access to their interior selves. In fact this method provides the only way to render the emotions and thoughts of which the character is not aware. It is also the most traditional method of consciousness representation. “Traditional” here does not mean that this method would be old-fashioned or that it would have been completely mapped. In psycho-narration the border between reporting narrator and represented character sometimes becomes difficult to draw. Which words must be attributed to the narrator and which to the character? Doesn’t the narrator alter the original words? Is the narrator perhaps being ironic?

The various relationships between narrator and character can be placed on a sliding scale between dissonance and consonance. A narrator can be at odds with the thoughts and statements of the character. To illustrate such dissonance, Cohn discusses a passage from Death in Venice, by Thomas Mann. The main character, Gustav von Aschenbach, thinks it is too late to flee from the doomed city, but the narrator doubts this: “Too late, he thought at this moment. Too late! But was it too late? This step he had failed to take, it might quite possibly have led to goodness, levity, gaiety, to salutary sobriety. But the fact doubtless was, that the aging man did not want the sobering, that the intoxication was too dear to him. Who can decipher the nature and pattern of artistic creativity?”42 This quotation shows that a so-called omniscient narrator may also entertain doubts and develop uncertainties and that dissonance does not necessarily mean that the narrator distorts a character’s thoughts. In this passage you can clearly see what the main character thinks and how the narrator reacts. A conflict between narrator and character does not automatically mean that the narrator censors or alters the character’s consciousness. Neither does it have to mean that narrators distance themselves from the characters. A melodramatic exclamation—“Who can decipher the nature and pattern of artistic creativity?”—could be seen as an echo of Aschenbach’s typical pathos, in which case the narrator adopts an aspect of the character after all—but of course this adoption may be meant ironically.

Consonance does not seem to leave narrators a voice or contribution of their own. They render the characters’ thoughts and reflections without any trace of criticism or rejection. The narrator’s consciousness almost seems to coincide with the character’s, making it impossible for the reader to separate the two clearly. Something of the sort happens in “Pegasian,” in which the narrator does not create any distance from the thoughts arising in the minds of the characters. Neither does the narrator side with one of them. It is difficult to figure out whether this narrator prefers the riding master or the female rider. As the narrator does not intervene, or hardly does so, consonant psycho-narration comes close to literal consciousness representation.

Literal consciousness representation by means of quotations constitutes the second type in a third-person context. Cohn calls it quoted monologue, a term she prefers to more traditional ones such as interior monologue and stream of consciousness. In any case, this variant comes down to the direct quotation of a character’s thoughts in the first person and in the present tense. As the quoting agent, the narrator can largely efface any self-evidence. This narrator can even cover up any tracks of presence, including little phrases such as “he said” or “she thought.”

In Ulysses one often notes that an omniscient narrator relinquishes that status to a character, so that psycho-narration turns into quoted monologue. For instance: “He stood at Fleet street crossing. Luncheon interval. A sixpenny at Rowe’s? Must look up that ad in the national library. An eightpenny in the Burton. Better. On my way.”43 The first sentence clearly features the narrator, who could continue the psycho-narration as follows: “Bloom thought it was time for a lunch break. He asked himself whether he would have a six-pence lunch at Rowe’s.” Instead the narrator goes for direct quotation of the stream of thoughts in Bloom’s mind.

As long as a monologue is set in the first person and the present tense, it is easy to decide whether the sentences originate from the consciousness of the character or from that of the narrator. Person and tense obviously indicate quotation and therefore quoted monologue. But when person and tense are absent, things become more complicated. “Pegasian” features the following passage: “And it wouldn’t hurt to consult a few books on cavalry. Horse riding without background information doesn’t make sense for anyone.” These opinions belong to the riding master, but since they appear out of context, it is impossible to decide whether they amount to a quotation. Maybe the narrator is present here in the form of free indirect speech, which could characterize the sentence prior to this passage: “Little girls who have never personally experienced this heavenly feeling did well not to shoot off their mouths.” The past tense (“did”) might suggest that this is not a quotation but a free indirect representation of consciousness. Perhaps this method of representation continues into the next few sentences.

Free indirect speech brings us to the third type of third-person representation: narrated monologue. As has already been mentioned, free indirect speech is suspended between direct and indirect speech. Here is a simple example:

- Direct speech: He asked her, “Can you leave tomorrow?”

- Indirect speech: He asked her whether she could leave the next day.

- Free indirect speech: Could she leave tomorrow?

Free indirect speech drops the introductory main clause (“He asked her whether”) so that the reported sentence becomes the main clause. It also holds on to the word order of the quotation (in this case the inversion in the original question), and it does not adapt indications of place and time (“tomorrow” is not replaced by “the next day”). Exclamations and interjections that disappear in normal indirect speech are kept. A quotation like “No, no, I have done it today” becomes “No, no, he had done it today” in free indirect speech. These are all characteristics of direct speech, but other than that, free indirect speech does apply the typical changes of indirect speech. It changes the tense and switches the personal pronoun.

The combination of direct and indirect speech often does not allow a reader to decide who is saying what. Indeed the words pronounced or thought by the character seem to be mixed with those spoken by the narrator. A classic case is Madame Bovary, by Gustave Flaubert. Quite a few readers considered this novel shocking because they attributed the character’s ideas to the narrator, whom they would then identify with Flaubert. To them, instead of Madame Bovary trying to negotiate her infidelities in free indirect speech, it was Flaubert himself who presented morally reprehensible action as a form of bliss.

The confusion between character and narrator appears clearly in the following passage from Madame Bovary: “Her soul, wearied by pride, was at last finding rest in Christian humility; and, savouring the pleasure of weakness, Emma contemplated within herself the destruction of her will, leaving thus wide an entrance for the irruption of His grace. So in place of happiness there did exist a higher felicity, a further love above all other loves, without intermission or ending, a love that would blossom eternally!”44 The narrator speaks in the first sentence; in the second, Emma Bovary comes in through free indirect speech. Readers who do not notice the shift could imagine that it is the narrator who ecstatically glorifies eternal love.

The fact that free indirect speech has caused scandals in the course of literary history points to the ideological implications of a certain narrative strategy. Narrated monologue combines the character’s ideology with that of the narrator, and because of this ambiguity the reader has a hard time figuring out the ideology promoted by the text. What does the implied author look like in Madame Bovary or “Pegasian”? Does Flaubert’s narrator really consider Emma’s adultery an escape to happiness? And does the narrator in “Pegasian” agree with the final lines of the story that advocate taking off, regardless of the means? Both narratologist and reader will have to decide for themselves where to draw the boundaries between implied author, narrator, and character. A traditional reader will want to draw them as clearly as possible even if the text rules out an unequivocal choice.

The potential confusion increases when it is no longer possible to tell the person of the narrator from that of the character—in other words, when the narrator’s speech is self-referential. In third-person representation the use of the first person clearly signals a quotation from the character. In a first-person narrative this is not the case anymore. Here a sentence in the first person can be a representation of the consciousness either of the narrating I or of the experiencing I (the I as character), and very often it becomes difficult to make the distinction. Where does the experiencing I start and where does the narrating I end? Usually a space of time separates the two figures, and a typical autobiography, where the older and wiser I tackles the younger and more naïve self, can serve as a good example. Sentences such as “At the time I did not know things would take a different course” prove that there is a clear distinction between the narrating I of the present and the experiencing I of the past. But often it is not that simple.

While at the beginning of “The Map” one can easily distinguish between the eager boy and the disappointed narrator, it becomes much more difficult to do so near the end. The story deals precisely with the way in which initial enthusiasm changes into indifference. This confusion between I-narrator and I-character is even bigger in Gerrit Krol’s novels. They feature many short fragments separated by a double space. It is often impossible to assign a time reference to these fragments, so that one is unable to decide whether the speaker is the I in the present or the I from the past.

Cohn’s three types in the third-person context reappear in the first-person context. The first-person equivalent of psycho-narration is self-narration. Here I-narrators summarize their memories. They do not quote themselves as younger individuals but instead talk, in a way similar to indirect speech, about the ideas and feelings they once had. Self-narration too can be consonant or dissonant. The latter is the case in the following passage from Voer voor psychologen (Feed for psychologists), an autobiographical novel by Harry Mulisch in which the narrating I (the older and wiser Harry) belittles the experiencing I (his younger counterpart): “Again my magic had immediately assumed a black and shady shape. At that time I also started to write, in the most appalling conditions one can think of, artistically speaking. Appalling because my orientation was entirely spiritual . . . and the artistic endeavor is in fact the most unspiritual of all.”45 These are clearly the words of the narrating I. His comments do not intend to create the impression that they accurately represent what young Harry specifically thought about art and the spirit. There is hardly any indirect speech here in the literal meaning of the term. Instead of a truthful recording, the reader gets a crude summary. If psycho-narration and self-narration are indeed related to indirect speech, then the latter must be considered in the largest possible sense as the summary account of what a character has said or thought.

In consonant self-narration the critical voice of the narrating I remains absent so that it seems as if the narrating I’s formulations are completely determined by what the experiencing I thought or felt at the time. The novel Asbestemming (Destination for ashes), by the Dutch author A. F. Th. van der Heijden, provides a clear example. The narrator, who also happens to be called Van der Heijden, describes how during his father’s funeral he for the first time in his life develops the feeling of fatherhood: “Under a high arch of music, deep down there, I clutched my son against me. I do not say this after the fact, the understanding came about at that very moment: that’s where my fatherhood was born. Hardly ever was I so intimate with a human being as then.”46

For Cohn, the quoted monologue of the third-person context becomes the self-quoted monologue in a first-person context. In this first-person version of the quoted monologue the narrating I quotes itself as a character. Here’s an example from the novel Sunken Red, by the Dutch author Jeroen Brouwers: “All I thought was: since she’s dead anyway, I’ll tchoop her doll with the eyes.”47 In the absence of quotation marks, if the introductory main clause (“all I thought was”) were dropped, the reader would have only the use of the present tense to decide whether it is the quoted younger I who is talking or the reporting older I. But if the present tense is used for a general truth, then there is a problem. The I-figure from Sunken Red describes a memory of torture he witnessed as a child in a Japanese internment camp, and the following sentence appears after a colon: “—the sun is the cruelest instrument of torture the Japs have at their disposal, the sun is the symbol of the Japanese nation.”48 Do these words belong to the boy or to the older narrator who is writing the story?

This kind of ambiguity grows in Cohn’s third type of first-person consciousness representation: the self-narrated monologue. Here the use of free indirect speech causes the present tense of the quotation to become past tense. As a result, narrative passages dominated by the narrating I (Cohn’s self-narration) surreptitiously shift to indirectly quoted monologues in which the character is talking (self-quotation). In “The Map” the young I-figure discovers a map of Dorkwerd village. His thoughts are rendered as follows: “I could be surprised by the degree of detail and especially by the name I read: Dorkwerd. The village I knew so well and which I had never seen on a map!” The first sentence contains words by the narrator and is an example of self-narration; the second sentence can be seen as an example of free indirect speech reproducing the thoughts of the character, and it can therefore also be seen as an example of Cohn’s self-narrated monologue.

Readers of a novel or story seldom consciously stop to make a distinction between the many ways of representing the consciousness of characters. However, this does not mean that the distinction would be irrelevant. On the contrary, a certain variety in consciousness representation makes for many of the characteristics a reader can attribute to a text. Quoting thoughts, for instance, may become monotonous, especially if short phrases such as “he thought” or “she believed” are repeated over and over again. On the other hand, quotations may reinforce the reader’s impression of truthful narration. Alternation in consciousness representation may also determine the rhythm of the text. Thus a long interior monologue may be followed by a brief summary of thoughts. By choosing a specific method of consciousness representation, narrators can manipulate the audience. If they criticize a character’s emotions, they help readers toward a specific interpretation that would perhaps be developed less quickly with the help of quotation. In conclusion, consciousness representation is of paramount importance for the understanding and interpretation of narrative. Readers who decide to ignore this fact may end up making the same mistake as those who were shocked by Madame Bovary.

6. Perception and Speech

In the introduction we briefly mentioned perception in “The Map.” We asked whether the little boy who is looking at the map is the same person as the narrating agent. We suggested that the I‑who-remembers is most probably the speaker, while the I-who-is-being-remembered is the one who looks at the map. A similar problem exists when the narrator differs from the character, that is to say (in Cohn’s words), when we are dealing with a third-person context. If a character remembers something, does that character automatically become the narrator of this memory? Or does one have to say that there is an omniscient narrator who represents the memories of a character in the form of Cohn’s consonant psycho-narration? In that case the character is the perceiving agent, while the narrator remains restricted to voicing personal perceptions.

The novel Een weekend in Oostende (A weekend in Ostend), by the Dutch author Willem Brakman, illustrates this problem. Blok, the main character, goes to the toilet and remembers the family visits from his youth: “Once in the toilet he drew the little bolt. [ . . . ] Those visits were strange affairs, no streamers, no swimming pool, no tea [ . . . ] but gaps one helped each other through by exchanging already endlessly repeated stories. [ . . . ] Thus the word ‘ear’ was an unavoidable ticket to the story of Blok’s father and his hospitalization.”49 Who says here that the visits were strange affairs? A structuralist working in the tradition of Mieke Bal and Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan would, as we will see later in great detail, make a distinction between the narrator and Blok. Blok imagines the events, but he does not narrate them, as can be derived from a formulation such as “Blok’s father.”

This distinction between the perceiving and the narrating agent is relatively new. The older so-called point of view tradition combined perspective with narration and thus mixed the figure who perceives with the one who narrates.50 We wish to dwell for a moment on a classic representative of traditional point of view theory, Norman Friedman. He popularized the terms that are still often used outside the discipline of narratology, such as omniscient narrator and I‑witness. The latter is symptomatic in that it proves to what extent traditional theory conflated perception (eye) with speech (I). The I-witness makes up one of the seven positions on Friedman’s point of view scale, which extends from maximal diegesis to maximal mimesis.51

At the pole of diegetic summary Friedman places editorial omniscience, or that possessed by omniscient authorial narrators who stand above the fictional world and summarize everything in their own words. Such narrators are clearly visible and address the reader in the first person so as to show what they think about the people and things they describe. If narrators make their presence slightly less felt, they move to the second position on the scale, which Friedman calls neutral omniscience. Here too readers get a clear idea of their narrators’ appraisal of characters and events, but such narrators no longer speak in the first person and do not directly address the audience anymore. The sentence “She was a nice and well-educated woman” is an example of neutral omniscience. If this sentence is changed to “I can safely say that she was a nice and well-educated woman,” then we have editorial omniscience.

Moving in the direction of the mimetic pole, Friedman conceives of two different I‑narrators who no longer stand above the fictional world but instead belong to it, appearing as characters. Those narrators in the I-witness category tell the story in their own words but lack the omniscience of the authorial narrator. A well-known example of this is Dr. Watson, Sherlock Holmes’s faithful assistant and witness to his adventures. The I-protagonist, on the other hand, is the typical narrator of autobiographical novels. Narrators in this category talk about themselves. The narrator of “The Map” occupies this position.

In addition, Friedman comes up with two different “character-narrators.” He describes the first one with the formulation multiple selective omniscience. This means that the story is being told from the perspective of at least two characters, so that the reader is offered nonidentical versions of the same event. These characters do not speak in the first person but rather through an inconspicuous omniscient narrator. The novel De Geruchten (The rumors), by Hugo Claus, nicely illustrates this position in that the events surrounding the protagonist René Catrijsse are considered a constantly changing cast of characters.52 The second character-narrator occupies the position Friedman calls selective omniscience, which means that only a single character provides the perspective on the narrated events. In the above quoted passage from Een weekend in Oostende, Blok provides this perspective. “Pegasian” presents a borderline case, because it shows both the view of the riding master and that of the pupil but still devotes most of its attention to the latter.

According to Friedman, selective omniscience has no real narrator. The reader looks almost directly into the minds of the characters.53 This aspect separates selective from neutral and editorial omniscience. The latter two clearly exhibit the intervention of an evaluative narrator. However, we disagree with Friedman when he submits that it would be possible to look directly into the mind of a character without the help of a narrating agent. We would prefer to describe this method of representation as consonant psycho-narration. Like Cohn, we believe that a narrative always implies a narrating agent. Such narrators may not be visible, but they are nevertheless present.

The seventh and final position on Friedman’s scale is supposed to approach pure mimesis. In this dramatic mode events would for the most part be shown almost without any summary or transformation. The point of view becomes that of a camera, which registers (as Friedman likes to suggest) without interfering in the action. On account of its numerous dialogues, a novel in this mode starts to resemble a play. The dramatic mode is almost always limited to parts of the text, but JR, by William Gaddis, with its more than six hundred pages of conversation and almost nothing else, comes close to realizing the ideal that Friedman described long before the publication of this novel. A camera can register only the outsides of people and things; interior processing thus remains unseen. According to Friedman, the dramatic mode almost completely does away with mediation, which was the basic feature of all the other positions.54 The first two mediate by means of omniscience, the two I-narrators mediate because they tell the story, and the character-narrators mediate since they perceive and present people and events. For us, even the dramatic mode still contains a mediating agent whose minimal visibility helps to create the impression of objective, mimetic representation.

Franz Stanzel’s theory is somewhat reminiscent of Friedman’s approach.55 This is because Stanzel too sometimes gets into trouble as a result of combining perception and narration. He maintains, however, that every narrative implies a mediating agent, so that a completely mimetic representation of events is impossible. His concept of mediation (Mittelbarkeit), which includes forms of perception as well as narration, results in three basic narrative situations (Erzählsituationen), which evoke Friedman’s editorial omniscience, his two I-narrators, and his two character-narrators. Stanzel distinguishes between the authorial narrative situation in which the narrator hovers above the story, the first-person narrative situation in which the I-figure takes the floor, and the figural narrative situation in which the narrator seems to disappear in order to make room for centers of consciousness situated in the characters.

Stanzel describes these three situations with the help of three scales, each representing a gradual development between two poles. The first scale is the person scale, which evolves from identity to nonidentity. A narrator may or may not be identical to a character. If narrator and character coincide, then we have an I-narrative, and if they don’t, a he- or she-narrative. This distinction overlaps with Cohn’s separation of first-person and third-person contexts. Stanzel’s second scale concerns perspective, which goes from entirely internal all the way to completely external. In the former you see the events through the eyes of a character in the story and in the latter through the eyes of an agent who stands above the fictional world, such as an authorial narrator. The final scale is that of mode, that is, Stanzel’s term for the degree to which the narrator comes to the fore. This scale slides from the pole of the teller-character, where the narrator is clearly present, to its opposite, where the narrator is nearly invisible. The latter is occupied by what Stanzel calls the reflector, a character whose mind perceives the events and thus gives the reader the impression that he or she has direct access to the character’s mind.

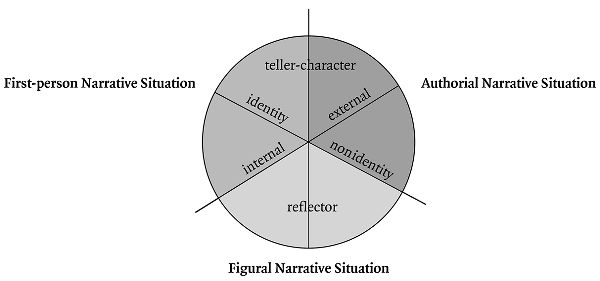

Although these three scales with their opposite poles are clearly reminiscent of the first six positions on Friedman’s scale, Stanzel comes up with a different and, more importantly, a more detailed system. He combines his three scales into a circle:

2. Stanzel’s circle. Adapted from F. K. Stanzel, A Theory of Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 56.

Each of the three basic narrative situations occupies one-third of the circle. The segment of the authorial situation runs from the teller-character pole on the mode scale to the pole of nonidentity on the person scale. In the middle of this segment sits the pole of external perspective, which constitutes the primary characteristic of the authorial situation since authorial narrators first and foremost stand outside the world they talk about. Secondary characteristics include the fact that the narrator is not identical to the character who is the subject of the narrative and the fact that the narrator is clearly present (as opposed to disappearing in favor of a character).

The first-person narrative situation is mainly characterized by identity since the narrator and the character who is the subject of the narrative coincide. It also features the clear presence of a narrator, as well as internal perspective, since one sees everything through the eyes of a figure who appears in the story. Finally, the figural narrative situation has as its basic characteristic the presence of a reflector rather than a teller-character. The narrator seems to have disappeared, so that everything becomes available through the reflector. This automatically means that the perspective is internal and that the narrative is told in the third person, which on the person scale implies nonidentity.

Stanzel’s circular representation has the advantage that the relationships between the various methods of narration are very clear. The various methods do not exist separately; they overlap incrementally into the next grade. There are three clear cases of gradation. First, authorial narration can develop into figural narration when it crosses the junction between the identity scale and the circle, that is, when narrators who do not coincide with any of their characters yield the floor to these characters to such an extent that the narrating voice becomes indistinguishable from the characters’ perceptions and ideas. This situation applies in the case of free indirect speech, which, as we know, occupies the borderline between authorial representation and character-oriented representation. Second, emphatically present authorial narrators can use the first person so regularly that they approach the border with first-person narration. No wonder it is the teller-character pole that constitutes this borderline in Stanzel’s system. When first-person narrators of this type surrender every form of authorial pretense, they restrict themselves to their own internal perspective and cross over to first-person narration. In its extreme version, this surrender results in self-quoted monologues, in which the reader sees only what goes on in the mind of the I-figure. Third, the border between first-person narration and figural narration can be transgressed when fragments of quoted monologue appear framed by descriptions of the character who delivers the monologue. We have already encountered an example of this from Ulysses, in which the character of Bloom switches from being a reflector in a third-person description to a speaker in the first person.

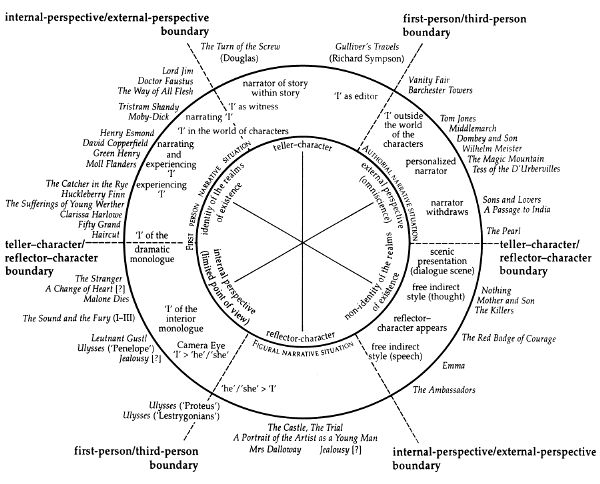

In order to map all these transitions, Stanzel has extended his circle. In the middle of each scale he has drawn a perpendicular line so that on the circle it marks the spot where one side of this scale (for example, that of the teller-character) crosses over into the other (for example, that of the reflector). Stanzel combines the three scales and their respective perpendicular lines in two concentric circles:

3. Stanzel’s double circle. From Susana Onega and José Angel García Landa, Narratology: An Introduction (New York: Longman, 1996), 162. Used with permission.

Stanzel holds that this circle covers all possible narrative situations. All narrative texts would fit into this system. When a narrative deviates from one situation, it approaches another. The circle would also clarify a particular historical development. The reflector would barely show up until modernism appears in the early part of the twentieth century. Traditional novels would all be located in the domains of authorial and first-person narration.

Although Stanzel’s double circle is an impressive systematization, we will not follow his proposal in this handbook. As we will explain when discussing structuralism, we believe it is absolutely necessary to distinguish between the agents of speech and perception. They belong to different levels. The agent of perception is part of the story as it is told, while the agent of speech is responsible for the telling. In spatial terms this distinction would result in different layers that Stanzel’s circle cannot accommodate. His circle is a flat plane that does not distinguish between perceiving and talking but instead considers both as forms of mediation.

This circle is one-dimensional in other respects as well. It deals only with narrative situations and does not say anything about a great many essential aspects of narrative and narratology. What about the manipulation of time? Or what about the difference between summary and scene? How do events connect to become a plot? All these questions are taken up in great detail by structuralist narratology, but they fall outside the scope of Stanzel’s circle.

In an important discussion of Stanzel’s system, Dorrit Cohn suggests that the difference between the scales of mode and perspective is untenable.56 She suggests that an internal perspective inevitably means you are looking into or from the mind of a character, and it therefore implies the reflector mode. An external perspective means equally inevitably that events are represented by an agent who stands outside and above the characters and therefore occupies a place on the teller-character side of the mode scale. The perspective scale is redundant since it coincides with that of mode. That leaves us with two scales—the one related to person, which distinguishes between I and he or she, and the one for mode, which distinguishes between narrator and reflector. Cohn holds that a teller-character shows through as soon as you see the difference between the speaking agent and the character who is the subject of the agent’s speech—or, to put it in her terms, when there is dissonance. To her the reflector illustrates consonance since in that case the narrator becomes so absorbed in the thoughts and feelings of the character that the two figures seem to coincide. To sum up, Cohn simplifies Stanzel and incorporates his view on mode into her theoretical frame of consonance and dissonance. Her circle looks like this:

4. Cohn’s circle. Adapted from Dorrit Cohn, “The Encirclement of Narrative: On Franz Stanzel’s Theorie des Erzählens,” Poetics Today 2, no. 2 (1981): 157–82.

Cohn further believes that there can be no gradual or inconspicuous transition between figural narration in the third person and consonant first-person narration. According to her, the example from Ulysses does not show that one method of narration develops into the other but that the two differ significantly. Here is the passage again: “He stood at Fleet street crossing. Luncheon interval. A sixpenny at Rowe’s? Must look up that ad in the national library. An eightpenny in the Burton. Better. On my way.” The reader will notice that the third-person narrator of the first sentence is suddenly replaced by an I-narrator. The distinction between I and he is therefore not canceled at all. Instead of a vague shift, the passage shows abrupt change, while Stanzel maintains that one form imperceptibly changes into the other. Cohn therefore leaves a gap on the circle between consonant first-person narration and figural third-person narration.

Although Stanzel has a lot of praise for Cohn’s criticism, he rejects this gap.57 Stanzel would read the Joyce example differently. For him, its second and third sentences (“Luncheon interval. A sixpenny at Rowe’s?”) do not allow the reader to decide whether they belong to the first-person narrator or the third-person narrator. In general there are only two indications from which to conclude who is talking: the explicit use of “I” or “s/he,” and the tense of the verb (past in the case of the third person, present in the case of the first). Sentences without an indication of the person and without a verb therefore float between “I” and “s/he,” so that one cannot speak of a rift or an abrupt transition. Here is another example: “His heart quopped softly. To the right. Museum. Goddesses. He swerved to the right.”58 The passage begins and ends with a third-person narrator, while the other Joyce passage started in the third person and ended in the first. Between beginning and end, both passages feature similar brief sentences without a verb or any indication of the person. If you interpret these snippets on the basis of the passage’s last sentence, you would probably read “Lunchbreak” in the first passage as an example of first-person narration, while you would probably consider “To the right. Museum,” in the second, as an example of third-person narration. There are no clear borders or sudden rifts here, Stanzel would say, and he holds on to the continuation of the circumference at the bottom of the circle.

Cohn and Stanzel agree that gradation is definitely possible at the top of the circle, where the authorial narrator changes into the first-person narrator. A visible authorial narrator speaks and does so in the first person. The remnants of his authorial status shine through in the dissonant I-narrator who, just like an authorial narrator, belongs to a world different from that of the characters.

The six topics we have dealt with in this chapter all result in a binary relation, which often comes down to an opposition: story and plot, showing and telling, author and narrator, narrator and reader, consciousness and representation, and perception and speech. In structuralism, which we will address in the next chapter, these six individual topics are combined into an encompassing and hierarchical system. This can be seen as substantial progress since it transposes the various aspects of narrative analysis into a unified whole. In the structuralist system some binary oppositions are qualified and developed, so that they sometimes turn into three-part relations. Thus the connection between story and plot will be extended to the three basic levels of structuralist narratology: story, narrative, and narration. This too is an improvement since we have often had to establish that dual oppositions do not answer to the complexity of a concrete narrative text. As we will see, the structuralist approach tries to accommodate this complexity.