2

Structuralism

Contemporary narratology finds its roots in the work of the French structuralists. Issue number 8 of the journal Communications usually figures as the official starting point of the discipline. This issue, which came out in 1966, contained nine articles with proposals for concepts and methods that could be used to study narrative texts. Some of these articles have acquired stature as classics. This certainly holds for the plot analysis proposed by Roland Barthes, which we will discuss shortly, but other contributions, by A. J. Greimas, Claude Bremond, Umberto Eco, Gérard Genette, and Tzvetan Todorov, have remained important as well.1 In his Grammaire du Décaméron (Grammar of the Decameron) published three years later, Todorov introduced the term “narratology”: “We wish to develop a theory of narration here [ . . . ]. As a result, this book does not so much belong to literary studies as to a discipline that does not yet exist, let us say narratology, the science of narrative.”2 The French structuralists recognize the Russian formalists as precursors of this scientific discipline. Vladimir Propp’s analysis of fairy tales can be seen as an embryonic example of structuralist narratology.3

The structuralist distinction between the text as it appears and its underlying patterns also stems from the formalists. As we will see, these Russian literary theorists made a distinction between the abstract chronology of events and their concrete sequence in a narrative text where they often do not proceed in chronological order. Structuralism is characterized by the gap between surface and deep levels. In the collection Qu’est-ce que le structuralisme? (What is structuralism?) Todorov explains that structuralism does not deal with the literary text as it presents itself to the reader but rather with a deep, abstract structure.4 The science of narratology, rather than investigating the surface, should study that which is fundamental to narrative.

This approach has led to the division of the narrative text into three levels. Genette describes the surface level with the term narration—the same in the French original and in our English translation—which comes down to the formulation of the story.5 Narration refers to the concrete and directly visible way in which a story is told. Word choice, sentence length, and narrating agent are all elements that belong to this level. Genette situates the second level slightly under the surface and calls it récit in French, which we will translate as narrative in English. Narrative is concerned with the story as it plays out in the text. Whereas linguistic formulation was central to narration, the organization of narrative elements is central to narrative. Narrative does not concern the act of narration but rather the way in which the events and characters of the story are offered to the reader. For instance, a novel starts with the death of the male protagonist and then looks back to his first marriage from the vantage point of his son, after which it looks forward to the end of that marriage from the perspective of his second wife. So the level of narrative has to do with organizational principles such as (a)chronology and perspective.

Genette’s final and deepest level is histoire, which we translate as story, not least because its most concrete form coincides with E. M. Forster’s concept of story—the chronological sequence of events—as we have presented it in chapter 1 of this handbook. This level is not readily available to the reader. Instead it amounts to an abstract construct. On this level, narrative elements are reduced to a chronological series. The story of the example above would start with mention of the man’s first marriage, then the end of that marriage, and finally the man’s death. Here the protagonist does not appear as a concrete character but as a role in an abstract system. The setting is reduced on this level to abstract characteristics such as high or low and light or dark.

There has been endless discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of such an approach. We limit ourselves to a few remarks that will be useful for the rest of this book. First, structuralist narratology deals with the concrete text only via an abstract detour, notably the construction of a so-called deep structure that ideally remains so abstract that it consists only of symbolic and formal elements. The narratologist’s ideal was the concept of a distinctive feature in phonology. Such a feature does not have a meaning of its own, but it causes differences of meaning. The contrast between voiced and voiceless is a distinctive feature. For instance, phoneme /b/ is voiced and /p/ is voiceless. In itself the difference does not mean anything, but it does result in the difference between “bath” and “path,” for example. Narratology never reaches such an abstract and exclusively formal level. All the elements structuralists isolate in the story as formal components of deep structure invariably carry meaning that destroys their dreams of an absolute formality.

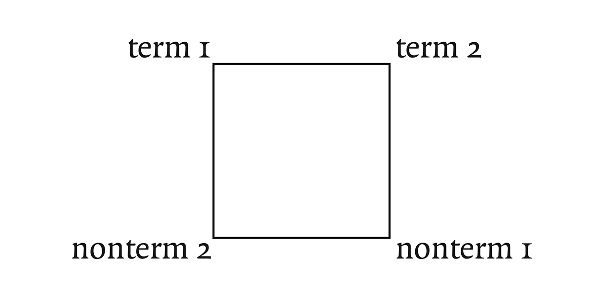

Second, deep structure in principle has to be as universal as possible, but in practice it differs from structuralist to structuralist. The deep structure proposed by Barthes is different from Todorov’s, but it also differs from those of Bremond and Greimas. In devising a deep structure one can apparently settle for different levels of abstraction. In its least abstract form, the story is the chronological sequence of events, but try to go any further and difficulties abound. Greimas’s semiotic square is far more abstract than Barthes’s narrative grammar. Greimas reduces a narrative text—and sometimes even an entire oeuvre—to four terms he combines in a square, which in its schematic form looks like this:

5. Greimas’s semiotic square. Adapted from A. J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale: Recherche de méthode (Paris: Larousse, 1966), 180.

Greimas calls the relation between terms 1 and 2 one of contraries, such as life versus death. Between term 1 and nonterm 1 (or term 2 and nonterm 2) there is a relation of contradiction. For instance, the combination of life and nonlife is contradictory. The connection between term 1 and nonterm 2 (or between term 2 and nonterm 1) Greimas describes as one of implication. Life implies nondeath, and death implies nonlife.6 One could reduce narrative texts to a number of squares and explain textual development as a combination of these squares and their terms. Here is a stock example: a girl is in love with a poor man but has to marry a rich one whom she hates. This situation implies at least two squares: one (A) in which term 1 is prohibition and term 2, order, and another (B), in which term 1 is love and term 2, hate.

6. Greimas’s square, example.

The initial situation combines prohibition (A term 1) with love (B term 1), and order (A term 2) with hate (B term 2). If, as a result of various adventures, the girl is allowed to marry the man she loves after all, the story develops into a combination of nonprohibition (A nonterm 1) with love (B term 1), and of nonorder (A nonterm 2) with hate (B term 2). All stages between beginning and end can be described as a combination of certain terms in certain squares. This approach resembles the reduction of a movie to a set of slides. If one applies such a reduction to an entire oeuvre—which then appears as a single square—a number of essential aspects will inevitably be lost.7

Barthes counters Greimas’s abstract and static square with a dynamic sequence of functions that connect more closely to the order and development of events in the actual text. When later in this book we try to systematize events and actions in our discussion of story, we rely on Barthes’s system because it is more concrete and dynamic than Greimas’s. However, we conclude that discussion with the remark that our choice does not reflect the structuralist treatment of events in the narrative text. There are as many opinions on this subject as there are structuralists.

This variety of deep structures points to a third problem related to this issue: How does one arrive at a particular deep structure? Here too the structuralists fail to come up with an answer. There are no clear discovery procedures.8 Instead of being based on actual texts, deep structures are simply posited.9 There is a considerable risk that texts will be manipulated until they fit the model. In other words, the model sometimes takes precedence over the concrete text, and the theory becomes more concerned with itself than with the literary works it supposedly investigates.

It seems as if structuralist narratology, with its division of narrative texts into three layers, adopts a geological model. Critics of structuralism have called this treatment of the text a form of “spatialization.” They have two basic reproaches with regard to this procedure. To begin with, spatialization underestimates the importance of time. A narrative text unfolds in time not only when it comes to its events but also when it comes to the act of reading, which always takes up a certain amount of time. Structuralist narratology represents a narrative text by way of schemata and drawings that are sometimes reminiscent of geometry. Textual elements are literally and figuratively mapped. The resulting map provides a static and general view that does not do justice to the dynamics of the concrete and sometimes quite chaotic process of reading. Second, the structuralists tend to focus on the lines of separation between the three layers, so gradual transitions are often overlooked. In their search for the differences and gaps between the levels, they fail to appreciate gradations and similarities.10

These points of criticism do not detract from the fact that structuralist narratology is the first large-scale attempt to combine all aspects of narrative analysis in a convenient system. The model resulting from the combination of the three levels allows a reader to link all the central aspects of a narrative text. One can see, for instance, how characterization connects with the setting or the method of narration and the perspective from which events are perceived. This leads to congruities that not only offer better insight into the formal organization of the text but also enable the reader to join content and form. Encompassing structuration is and remains structuralism’s major merit since it clarifies both textual content and form. That is why this particular brand of narratology continues to provide an indispensable legacy even to those readers whose main interest lies in later approaches.

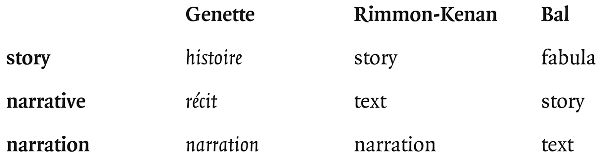

We will elucidate the three levels of the narrative text with reference to three important structuralist narratologists: Gérard Genette, Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan, and Mieke Bal.11 Unfortunately, these critics do not use the same terms for the levels. In order to avoid confusion, we combine all the terms in a figure, whose left column contains the concepts we will favor in this handbook. From our choice one will notice that we no longer use the term “plot,” which we provisionally worked with in chapter 1 when discussing E. M. Forster. While the emphasis of the term “plot” seems to be on what we call narrative, its meaning spills over into our preferred term, “narration.”

7. Narratology’s geological model.

1. Story

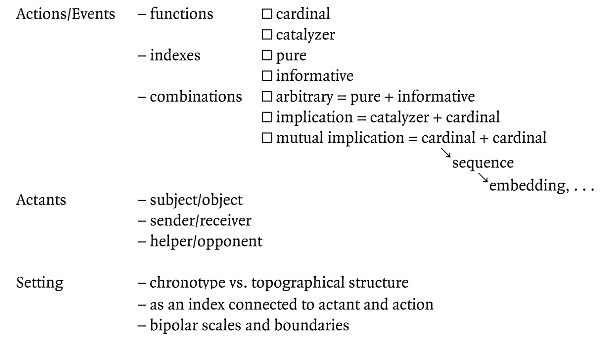

Just like any deep structure, the story is an abstract construct that the reader has to derive from the concrete text. The diagram below shows that the story consists of three aspects that will be discussed separately but that in fact always intermingle. In the course of the discussion, the terms in the figure will gradually become clear.

8. Story

1.1. Events

The story is an abstract level. In the first place it refers to the chronological sequence of events that are often no longer shown chronologically in the narrative. The Russian formalists used the term fabula for this chronological sequence (story) and syuzhet for the specific way in which it was presented in the text.12 Thus, the syuzhet covers both narrative and narration in our terminology.

Several proposals have been made to order events on this abstract level. The Russian formalists consider the motif to be the story’s most basic component. So-called bound motifs are indispensable for the fabula, while unbound motifs are far from essential. A murder, for instance, is a bound motif, while the road an assassin travels to shoot a targeted victim may well be considered an unbound motif since it is not crucial. The assassin’s clothing and age are unbound as well. Unbound motifs may be important on the level of the syuzhet, but they are not on the level of the fabula. Digressions about the killer’s clothing, age, and psychology are important for suspense, but they are unimportant for the development of the action. Formalists also distinguish between static and dynamic motifs. The latter change the progress of events, while the former do not. Bound motifs are usually dynamic and unbound motifs most often static, but this is not a rule. In principle the description of a character’s mental makeup constitutes an unbound motif, but this makeup may result in certain actions that give a decisive twist to the course of events. A murder is usually a bound motif, but if it does not bring about any change, it turns out to be static after all.13

Roland Barthes has refined these distinctions in his “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.”14 He distinguishes functions and indexes. Functions are elements whose interrelatedness is responsible for the horizontal progress of events, that is, their linear development. The relationship between these elements can take many forms, of which temporality, causality, and opposition are the most common. “X buys a gun” is a function that leads to “X uses the gun to kill Y.” The function “X is in love with Y” is opposed to “Y hates X,” and the tension between these two functions brings about a development in the story. Functions belong to what Roman Jakobson calls a syntagm, which is a horizontal sequence of contiguous elements. Elements are contiguous if their relationship comes down to a direct connection between terms such as “part” and “whole,” “cause” and “effect,” “producer” and “product,” “pole” and “opposite.” The link between buying the gun and using it is one between intention and execution. The killer buys the gun in order to use it. Jakobson calls these contiguous relations metonymical.15

Indexes, on the other hand, do not bring about the horizontal progress of events. They refer to a different plane, which means they function vertically. The many telephones on James Bond’s desk in the stories from the 1960s amount to an index of his importance. As a character he belongs to a different plane from the telephones, but he does get extra weight thanks to these instruments. The connection between the two planes could be called symbolic since the telephones symbolize Bond’s importance. The set of telephones reflects Bond’s busy life. In musical terms one could compare functions to melody and indexes to harmony or counterpoint. Melody derives from the horizontal progress of the score, while counterpoint arises from vertical accumulation.

Barthes distinguishes between two kinds of functions. A cardinal function implies a risk, which means it harbors a choice or a possibility. A question provides a minimal example of this type of function since asking a question leaves open the possibility of ignoring it. When the telephone rings, it may or may not be answered. More generally, almost all crucial events of the story belong to this category. An assassination attempt is a cardinal function and includes the possibility of failure. Narrative suspense largely rests on the risk central to this type of function. The second type of function described by Barthes is the catalyzer, which does not involve a risk but instead merely assures the continuation of what the cardinal function has started. When the telephone rings and Bond is in the room, he can walk to the telephone, let it ring for a few moments, and then pick it up. All the movements between the moment the telephone rings and the moment he picks it up are catalyzers, but the ringing and the answering remain cardinal to the whole sequence.

For the indexes Barthes offers a twofold division as well. A pure index is an element the reader must interpret. Bond’s clothing, his taste, and his preference for certain drinks are all interpreted by the reader as symbols of Bond’s sophistication and virility. Next there is the informative index, which is mainly important for spatiotemporal description and which does not require symbolic interpretation or the solution of a mystery. “It was seven forty-five and it was raining” makes up an informative index. Obviously this type may turn out to be a pure index when for instance the time indication enables the reader to accept or reject the suspect’s alibi.

A structure implies elements in a specific relationship to each other. In the present case the elements are the functions and the indexes, and the relations between them generally fall into three types. The combination of pure and informative indexes is arbitrary. In a self-portrait, for instance, direct information about age and place of birth will appear side by side with suggestive indexes the reader must interpret as indications of character. The relation between cardinal functions and catalyzers is that of implication. The catalyzer completes the cardinal function and is therefore implied by it. Finally, two or more cardinal functions have a relation of mutual implication, since one cannot do without the other. A murder cannot do without a murder weapon and vice versa: the gun is not a murder weapon without the actual murder.

For Barthes the combination of cardinal functions leads to sequences. They are independent units whose opening action has no precursor and whose conclusion has no effect. Seduction is a sequence. It starts with certain tactical moves and then results in success or failure, after which it is over. Sequences can in their turn be combined, for instance through embedding. Sequence A (seduction) can contain a sequence B (such as a story about the heroic deeds of the seducer) that may or may not lead to the successful completion of A. The insertion of B literally causes suspense because it temporarily suspends the continuation of A.

Here is how Barthes systematizes story events: he starts from minimal components such as functions and indexes, proceeds to create minimal relationships between these components (arbitrariness, implication, mutual implication), and so arrives at larger units in the story, such as sequences and their combinations.

It goes without saying that such a system works best with narrative texts in which many things happen. No wonder then that Barthes refers to James Bond. Bond stories contain clear sequences like “the murder,” “the hero is summoned,” “the hero starts an investigation,” and “the hero solves the murder.” In order to illustrate Barthes’s theory, we will analyze the story “From a View to a Kill,” which has a very clear sequence chronology.16 The syuzhet hardly deviates from the fabula because the presentation of events in the text closely approximates the story chronology. Only when Bond is keeping watch over a suspicious location in the woods does a short flashback briefly disturb the chronology. According to the Russian formalists, such a minimal difference between the abstract story and the concrete presentation of events is typical of nonliterary texts or of texts that hardly merit the literary label.

The Bond story starts with a murder sequence. An agent of the British secret service is driving his motorbike on a road through the woods. His mission is to deliver secret documents, but he gets shot by a man who has disguised himself so that he can approach the agent without being suspected. The killer then covers the traces of the murder as best as he can. This sequence can be divided into three cardinal functions: the pursuit, the shot, and the cover-up. There are many indexes. An attentive reader knows from the first few lines that the killer on the motorbike is not a positive character. He has eyes “cold as flint,” “a square grin,” and “big tombstone teeth.” His face has “set into blunt, hard, perhaps Slav lines.”17 A Bond reader will interpret these descriptions as characteristics of a criminal, probably from the Soviet Union. The mention of the time and place of the murder—seven in the morning in May, somewhere near Paris—constitutes an informative index.

By identifying functions and indexes, one can get a better understanding of each sequence. The second sequence, for example, could go under the heading “the hero is summoned.” A beautiful girl snatches Bond away from a sidewalk café and tells him about the murder. In this sequence there are more indexes than cardinal functions because information is more important than action. In the third sequence Bond is briefed at the headquarters of Station F. This briefing rounds off the first sequence, since Bond (as well as the reader) gets to hear what came of the cover-up. The remaining suspense of the first sequence is now totally gone. The briefing is followed by the first investigation at SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe), where staff are less than cooperative. Bond nevertheless manages to formulate a hypothesis, which amounts to the cardinal function of this fourth sequence—“the hero’s first investigation.” Bond tests his hypothesis in “the hero’s second investigation,” sequence number five, in which he observes in the woods the secret hideout where the killer and his two accomplices are holed up. Obviously the hero’s hypothesis proves to be correct. In the sixth sequence Bond devises a plan to apprehend the criminals, which he carries out in the seventh and final sequence. This sequence perfectly mirrors the first. Bond has taken the place of the agent on the motorbike, and now he is being shot at just like the agent in the beginning. He tricks the killer and clears the secret hideout, after which he explores his interest in the beautiful girl.

Such a systematization of events offers a number of advantages. First, it provides an overview of the various links between the sequences. The seventh sequence mirrors the first, the third one concludes the first, and the fifth one confirms the hypothesis of the fourth. The ways in which this story builds suspense thus become clear. This method also enhances the reader’s understanding of numerous details that become more meaningful when seen as a pure or informative index. Elements that might have seemed irrelevant in a superficial reading now acquire the importance they deserve, owing to this more searching analysis. For instance, it cannot be a coincidence that the murder is committed on a road through the woods where the criminals are hiding. As we will see in our discussion of the setting, criminals are constantly associated with nature, whereas the hero appears affiliated with culture, the city, and sophistication in general.

Barthes’s systematization becomes more difficult and less relevant for stories with few events. In “Pegasian,” for instance, sequences are difficult to distinguish. One could see the horse-riding lesson as the first sequence and the text’s lesson (“As long as you take off “) as the second. The cardinal function for the first sequence could be condensed as “dressage.” In this view indexes would be made up of all symbols of drill and submission, such as the “real pair of riding breeches” and the “background information” that would teach the pupil respect and politeness. The fact that one of the crucial indexes has to do with a pair of pants could then be seen as the symbolic combination of “dressage” and “dress” (in the meaning of clothing in general). This may indeed appear somewhat far-fetched, but obviously any systematization by the reader will have something arbitrary. There is no cogent method one can simply apply in order to arrive at the deep structure of events. The reader has an important role. The Bond story could be divided into three sequences or thirty sequences. Rather than fixed elements that can be abstracted from the text, structures are constructs that are always partly dependent on the reader.

The choice for Barthes’s system has something arbitrary as well, since many other options are available. For instance, rudimentary systematizations of story events can be found in Propp, who has developed thirty-one functions in his analysis of Russian fairy tales.18 The same goes for Eco, who has distinguished nine crucial moves in a typical Bond novel.19 Todorov claims that “the minimal complete plot consists in the passage from one equilibrium to another. An ‘ideal’ narrative begins with a stable situation which is disturbed by some power or force. There results a state of disequilibrium; by the action of a force directed in the opposite direction, the equilibrium is re-established; the second equilibrium is similar to the first, but the two are never identical.”20 The relatively linear or even deterministic sequence of these functions, moves, or (dis)orders appears only at the level of deep structure. In a concrete fairy tale or Bond novel, that system will mutate in various ways. The same holds for Greimas’s four action phases, consisting of manipulation, competence, performance, and sanction. These phases may also intertwine, thereby reducing the linearity of the narrative evolution.21

Less linear is Claude Bremond’s systematization. He starts from so-called pivotal functions, which always leave open the possibility of success or failure. Barthes’s sequence becomes a succession of three pivotal functions in Bremond. First there is possibility, which is followed by realization, and finally there is completion.22 For instance, a woman can devise a plan to kill her husband in order to inherit his wealth. The murder sequence starts with the possibility of carrying out the plan or not. If it is carried out, then the murder attempt may be successful or it may fail. If the murder proceeds as planned, then the woman may or may not inherit the money. Like Propp and Eco, Bremond envisages various transformations taking place between the relatively simple three-function structure and the often complicated developments in a concrete narrative text.

We have opted for Barthes’s system because it is far less hampered by such a complex series of transformations and because it does not start from frameworks as rigid as those offered by his colleagues. Barthes’s indexes, functions, and sequences are open concepts that the reader has to fill out with elements from the text. They do not impose a rigid order or interpretation. If, however, the reader’s processing gets a central place in the analysis, one moves away from the classical, structuralist action grammar. An example of such a readerly transformation of structuralist concepts can be found in the work of Emma Kafalenos. Building on the work of Propp, Greimas, and Todorov, she develops a model with ten functions.23 She studies them in terms of the concrete narrative (con)text and of the reader’s activities: “I use functions [ . . . ] to record readers’ interpretations as they develop and change (or fail to change) during the process of reading.”24

1.2. Actants

Events cannot be independent of the agents who are involved in them. We describe these agents with the term “figures,” which we will soon specify as actants, following Greimas. The term does not refer to the actual manifestation of a character in the text but rather to the specific role a character plays as an abstract agent in a network of roles on the level of the story. Here too every structuralist has developed his or her own networks and systematizations. Bremond, for instance, conceives of two fundamental roles: a passive one and an active one. Active figures steer and direct events, even though they often do not consciously develop a strategy. A prime example of such a figure is again James Bond. Passive figures such as the agent who is killed at the beginning of “From a View to a Kill” undergo events. On top of this, there are three criteria for going into the details of figure characterization: influence, modification, and conservation. Influence typifies figures—such as a seducer or an informant—who purposefully make a direct impact on the course of events. Modification marks figures who improve or aggravate the situation, while conservation distinguishes those who try to avert change.25 This explanation of Bremond’s criteria consistently presents the figure as an active agent, but obviously there are also passive figures who are influenced, modified, or stopped in their effort toward change. The same character can be both active and passive, depending on the viewpoint. The female rider in “Pegasian” actively wants to improve her situation, but she is “passively” helped by the riding master, who at first seems to hinder her.

Greimas’s actantial model is better known than Bremond’s systematization of roles.26 In its simplest and most useful version, this model consists of six roles or actants. These terms are synonymous with “figures.” There is a subject, who carries out the action and who strives for a specific object. This quest is inspired and provoked by a destinateur, whom we will call “sender” following Cok van der Voort.27 Greimas calls the agent who benefits from the quest the destinataire, which Van der Voort translates as the “receiver.” The agent who assists in the quest is the helper, while the agent who thwarts it is the opponent. This results in the following system:

9. Greimas’s six actants. Adapted from A. J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale: Recherche de méthode (Paris: Larousse, 1966), 180.

The italicized terms indicate the abstract relations between the actants: the subject strives for the object (desire), the sender wants the subject to transmit the object to the receiver, and the opponent and helper are involved in a struggle.

These are all abstract roles that should not be confused with actual characters. One character may play all the roles. In the case of a man who wants to quit smoking, one could say the subject is the smoker and his object, quitting. The sender is also the smoker—he himself wants to stop, he himself thinks it is necessary. The receiver is the smoker as well—he will benefit from giving up. The smoker’s willpower is the helper, and his old addiction amounts to the opponent. This example shows that roles do not have to be played by real characters. In addition, an emotion, a motivation, or an idea can function as an actant, when any of those performs, for example, as the sender.

Just as one character can play all the roles, one role can be played by many characters. Bond can get help from people such as the beautiful girl or the man from intelligence, but his helpers can also be state-of-the-art weapons or even more abstract things, such as his courage or resourcefulness.

This story structure has the advantage of being simple and generally applicable. It can literally be applied to every narrative text. For instance, the Marxist philosophy of history can be represented with the terms offered by Greimas. Its subject is humanity and its object, a classless society. History is the sender and humanity (or at least the proletariat), the receiver. The proletariat is the helper as well, whereas capitalists play the role of the opponent. In the case of “Pegasian” the female rider is the subject, and the story’s object is being able to fly. The horse—more specifically perhaps the winged horse Pegasus, the symbol of the muse linked to poetry—plays the role of the helper. Dressage and the riding master at first seem to act as opponents, but eventually they turn out to be helpers as well. The sender is the desire to overcome gravity, while the receiver is the girl and, on a larger plane, perhaps also the reader who understands the moral lesson.

Simplicity and general applicability are at the same time the model’s disadvantages. It seems just too easy to reduce all characters and motivations to six roles. If the role of the sender can comprise such diverse elements as a motive, an onset, a character who obliges or invites, and an order or a law, then one might ask whether it would perhaps be useful to specify the category of the sender somewhat further or even to divide it into a set of subcategories. The general applicability of the model also means that it lumps all kinds of narrative texts together and treats them indiscriminately, whether it is the Marxist philosophy of history, the story of the man who wants to give up smoking, or the story of the female rider who wants to learn how to fly.

Furthermore, Greimas does not offer an easy method to go from the actual narrative text to the actantial model. Different readers will come up with different actantial structures for the same story. In “Pegasian” the riding master could also become the subject, in which case the object would be the teaching of the necessary discipline. The sender would then be the riding master or, more generally, the demands of horsemanship. The female rider in this view is still the receiver, but she also acts as the opponent. Finally, the helper is the horse, which lets itself be trained. Complex texts with many events risk the development of totally diverging actantial models. Readers who appoint the murderer as the subject of a detective novel will obviously come up with a different model from those who choose the detective for this role.

Extensive narrative texts often complicate the application of the model. Does one need to devise one model for the entire text or one for every chapter? Or maybe one for every sequence or for an even smaller unit? If each of the seven sequences of “From a View to a Kill” is analyzed according to the actantial model, then it becomes clear that James Bond does not act as the subject in the first three sequences. He is absent from the murder sequence. In the second sequence (“the hero is summoned”) he functions as the object. In the third sequence (“the hero is briefed”) he acts as the receiver since he acquires the information. It is only in the fourth sequence that he becomes an active heroic subject, thereby finally assuming the role one would expect of him. This abstract order shows how the main character is first announced and then patiently put together: he goes from absence to object, from object to receiver, and eventually from receiver to hero. Greimas permits the discovery of a structural principle that might otherwise remain unnoticed.

In this way the systematization of actants, just like the systematization of the story’s actions, assures a better understanding of the macro- and microstructures of a narrative text. Actions and events differ from one another on the basis of actant involvement. An action derives from an actant, while an event happens to the actant. In naturalist novels events usually take precedence over actions. Human beings find it hard to resist the events that befall them. However, this contrast between actions and events does not amount to a fundamental distinction, since the actantial model allows for the interpretation of events as actions by abstract actants such as fate, death, old age, or social class. In this way both actions and events can be made to fit the actantial model.

This fact points to the interdependence of actions and actants. The reader will expect certain actions from a specific actant. Very often these expectations are linked to stereotypes circulating in the reader’s social and cultural context.28 By playing with a reader’s anticipations, a narrative text can create suspense and take surprising turns. At the beginning of a detective novel the reader might think that a given character is a helper, but the character’s actions might slowly lead to the suspicion that this individual could be an opponent. Conversely, the confirmation of expectations creates a certain predictability that some readers take as a guarantee of reliability. Certain deeds are expected of heroes. If they do not deliver, they will not be considered real heroes, and in that sense they are unreliable characters. One does not expect the same feats from an octogenarian as one expects from a hero like James Bond.

If we connect the actant to both its actions and its depth, then we are moving from abstract role to concrete character. Traditionally there exists an inversely proportional relationship between the amount of action and the degree to which a figure is psychologically developed into a many-sided character. The more action there is, the less profound the character. This rule may not always apply, but it certainly holds true for traditional genres such as the adventure novel and the detective novel.29 Profundity is defined by the number of character traits and their variation. Forster has made the traditional distinction between, on the one hand, static, one-dimensional flat characters and, on the other, variable, many-sided round characters.30 This distinction is quite problematic. Leopold Bloom in Ulysses has many aspects, but he does not really develop. An allegorical character such as Everyman (from the eponymous medieval morality play) is notably flat, but he does develop.

Rimmon-Kenan proposes to determine the richness of a character with the help of three sliding scales, which together make a three-dimensional coordinate system.31 The first scale indicates complexity and goes from a single characteristic on the one pole to an infinite range of characteristics on the other. The second scale, which deals with development, runs from the pole of stagnation to that of infinite change. The third scale indicates the degree to which the text shows the character’s inner life. At the left end of this scale Rimmon-Kenan situates characters seen only from the outside, while at the other end she places characters whose inner lives are described with great attention to detail. In a psychological novel, many characters will presumably occupy positions close to the right-hand end of the scales (numerous characteristics, significant development, and an insistence on inner life), while in an action-packed story, like the one about James Bond, most characters will appear closer to the left-hand end. In “The Map” the I-character is not very complex, as few of his features are mentioned. On the other hand, there is considerable development since the young I who believes in the magic of mapping evolves into an older I who has practically no illusions left on this score. Of the two types of I, the reader sees mainly the interior.

Such a three-dimensional characterization of role makes the transition from a deep, abstract level to the level of visible characters in the concrete narrative text. Seymour Chatman describes the role as the “syntagmatic reading” of a figure since the latter functions as an element in a horizontal chain of actions, a position in a network of connecting events. The paradigmatic reading considers the figure as a set of traits, a vertical stack of indexes referring to a personality and therefore to a concretely drawn character.32 If one does not see the female rider in “Pegasian” as merely the abstract role of a subject reaching for an object (notably “taking off”), then one shifts to the more concrete level of characterization, at which she will be described with adjectives such as “playful,” “disrespectful,” and “relativizing.”

1.3. Setting

There is more to the story than actions and actants. Events take place not only in conjunction with certain roles but also in a specific time and place. Such a spatiotemporal indication is often described with the term setting. The Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin prefers to speak of a chronotope, a textual combination of time (chronos) and place (topos).33 According to him, the spatiotemporal setting constitutes the narrative and ideological center of the text because it shapes figures and actions. Abstract themes like love and betrayal acquire a concrete form within and thanks to a specific chronotope. The Greek romance, for instance, features what Bakhtin calls “adventure time,” which requires “an abstract expanse of space” for the genre’s typical abductions, escapes, and pursuits to take place.34 An abstract view of humankind and social reality can be concretized only if figures (humankind) and events (reality) are embedded in the chronotope.35 The heroes of Greek romance thus roam the space that is available to them. Insofar as the text embodies a worldview, it contains an ideological dimension, which we will elaborate in chapter 3.

As the example of the Greek romance already indicates, Bakhtin proposes that every genre and every type of discourse develops its own chronotopes.36 His other examples include the picaresque novel, which centers on “a road that winds through one’s native territory,” and the idyll, which is determined by “the immanent unity of folkloric time.”37 However, one could also think of the Gothic novel with its combination of the haunted house and events often taking place at night. If Bakhtin is right, the story’s credibility rests to a large degree on the interaction between actions/events, actants, and setting.

Actions cannot be separated from the setting. An account of a chase requires the description of the scenery as it rapidly passes. Moreover, the setting often amounts to an index for the action. In the story discussed earlier, it is no coincidence that James Bond unmasks the killer in the same environment where that very killer used a disguise to shoot an agent. Although the road through the woods is not a highway, as an index it refers to culture, while the woods themselves are part of nature. Once Bond has shot the killer on this road and removed his accomplices from the woods, nature has resumed its innocence and attraction. The final scene takes place in the woods. Bond talks to the beautiful girl, and his words show that nature has traded its connotations of terror for those of eroticism: “Bond took the girl by the arm. He said: ‘Come over here. I want to show you a bird’s nest.’ ‘Is that an order?’ ‘Yes.’”38

This example proves that the setting can also function as an index for the actants. Good Westerners live in the civilized city space, whereas bad Soviets live in the natural habitat of the forest. The clash between them plays out in a space between these two environments, as well as in an in-between time, the period between night and day (seven o’clock in the morning).

At first glance the spatiotemporal background against which the story develops appears relatively fixed. The Russian formalists categorize it as a static motif; Barthes would call it a pure or an informative index. Both terms are appropriate since the fictional universe does not cause the story to develop. However, story development is inconceivable without the setting, which makes it possible for actions to take place and actants to become involved in them. It is impossible to imagine roles and events without embedding them in time and space.

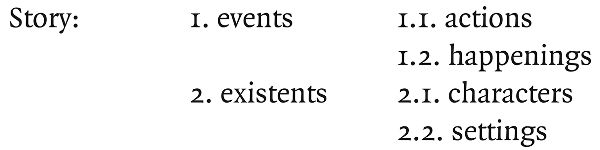

Chatman’s schematic representation of the story insists on the fundamental connections between actions, actants, and setting.39 His visualization is as follows:

10. Chatman’s schematic representation of the story. Adapted from Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1978), 26.

Events are dynamic components of the story, while existents are relatively fixed points around which the story can unravel. Obviously, characters and setting can develop in the course of the story, but in Chatman’s proposal a certain stability remains. Ruth Ronen qualifies this relative permanence by defining setting as “an immediately relevant frame [i.e., a fictional place] regardless of the continuous textual evidence for its relevance.”40 Ronen does not require Chatman’s continuity.

In a very elaborate analysis of setting, Gabriel Zoran tries to solve the fundamental problem: that time rather than space dominates “in the structuring of the narrative text.”41 Bringing in the experience of the reader (who is mostly invisible in structuralist narratology), he distinguishes three levels of the “reconstructed world” in which the characters operate and the action takes place. On the textual level, the fictional world still retains some of the structuring patterns of the text. It may be determined, for instance, by the perspective of a character (which to us is an aspect of “narrative”) or by the narrator’s regular mention of a specific location (which to us is an aspect of “narration”). On “the chronotopic level, the reconstructed world is already independent of the verbal arrangement of the text, but is still dependent on the plot,” which means, for instance, that certain locations are points of departure and others represent the end of the journey. Finally, on the topographic level, “the world is perceived as existing for itself [ . . . ] cut off entirely from any structure imposed by the verbal text and the plot.”42 The topographic level is clearly part of the story in its most abstract guise, and the chronotopic level also implies a degree of the abstraction integral to our definition of the story. Interestingly, the reader supposedly moves back and forth between the three levels, which turns the notion of the story into an element of the act of reading. In chapter 3 of this handbook we will return to the role of the reader in the construction of the fictional world.

Zoran conceives of the topographical structure as a map based on a series of oppositions. Structuralism in general likes to work with binary oppositions that can form the basis of a sliding scale.43 Greimas thus distinguishes between topical spaces (where the action takes place) and heterotopical spaces (where the previous or subsequent actions take place).44 Following Mieke Bal, one could investigate space relying on pairs such as inside versus outside, high versus low, and far versus close.45 It is no coincidence, for instance, that the interminable tortures in the work of the Marquis de Sade almost always take place in the closed, dark space of an underground dungeon. A structuralist will use similar oppositions to characterize time: short versus long, continuation versus interruption, day versus night, light versus dark. In his story “Het lek in de eeuwigheid” (The leak in eternity), the Dutch author Willem Frederik Hermans indulges in the opposition between a long darkness and a brief period of electric illumination by a fixture that switches off automatically. Just as the light comes on briefly in an eternity of darkness, human life appears briefly in an eternity of death.46

The central aspects of Bal’s space and time characterization, which she borrows from the structuralist semiotician Juri Lotman, are the drawing of a borderline and its potential transgression.47 Actions and actants transgressing these borders often play a central role in the story. A burglar or spy is unthinkable without the violation of the border between private and public, open and closed. Murderers and rapists do not respect these borders either. In the bourgeois novel heroes often repair borders, while in the adventure novel they are likely to overturn the bourgeois system. Transgression, for that matter, may be a step on the way to recovery. In the medieval Dutch epic Karel ende Elegast (Charlemagne and Elegast) the title character, Karel, goes out stealing in order to discover who stands inside and who stands outside the feudal space. Of course the stealing takes place at night and includes a journey through a dark wood. Night and the wood form part and parcel of the chaos that normally threatens order but that in this case brings about its restoration.

In “Pegasian” space and time are not evoked very clearly, but some indications are nevertheless available. The story concerns a lesson during which many horses trot around in a “carousel.” The association with a merry-go-round provides points to the story’s central theme— dressage and discipline. The horses do not run around in nature, and their circuits in the riding school make them as unfree as the wooden horses on a merry-go-round. This image therefore conjures up three different spaces: nature, the riding school, and a fairground. If the carousel in the fairground implies an element of fun along with the immobility of its horses, this aspect of the story’s spatial structure might resolve its basic opposition: nature and the discipline of dressage.

Space and time are important in “The Map” as well. The boy discovers the near-divine map on a Sunday, and he sees it through a forbidden gap. The map’s attraction can largely be attributed to the fact that the boy’s peek at it was unexpected and actually prohibited. Later on, the map allows a look at the entire environment of his youth, at all the roads and pathways he biked as a boy. In this respect the map provides a visible and spatial representation of an entire period in his life. But as soon as that representation is complete, the fun is over. Regarding “The Map,” Zoran’s conception of the topographical structure as a map coincides with the object that evokes the narrator’s entire childhood. This overlap probably helps the reader to imagine space on the topographical level, a mental effect that might well make it easier to develop a version of the nostalgia at the heart of the story. While this interpretation does work with the combination of space and time on the level of the story, its emphasis on the reader goes beyond the tenets of structuralism.

In Wasco’s book of graphic fiction, Het Tuitel complex (The Tuitel complex), the “City” page we focus on in this handbook appears to the right of a page marked “Horizon.” The differences between the two in terms of color (light versus dark) and in terms of image size (wide like a horizon versus narrow, as in an inner city streetscape) appeal to a general opposition between country and town. It’s only at the very end of “City” that the protagonist’s spaceship rises above the roofs and a panoramic view reenters the text, and even then it is not an open space but a cramped, claustrophobic one. The horizon is nowhere to be seen; it is blocked by the mass of buildings. However, Zoran’s topographical structure here amounts to an unusual map, since the urban environment is quite strange. Unusual holes dot the streets and ramps look like dangerous slides. Sharp objects protrude from unexpected places, and there is even a kind of electric chair on a terrace. Panels eleven and twelve feature weird works of art, which enhance the artificiality of the environment. If there is life in this city, it can’t be seen (save for a lonely bird, whose yellow color seems to suggest it doesn’t belong there). Of course the spaceship indicates the future, which could suggest the chronotope of the dystopia, in which a worry about our contemporary world (like the anonymity of city life) appears as a characteristic of a more or less distant time (the city in “City” is empty).

2. Narrative

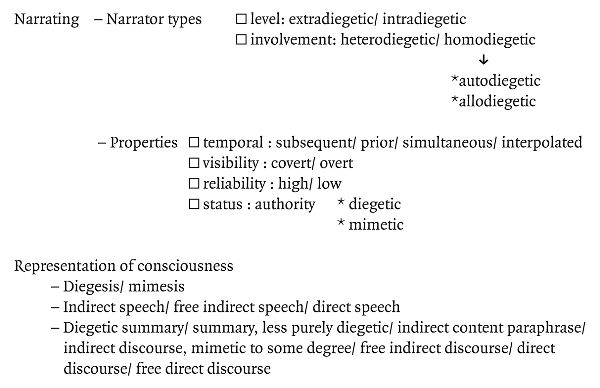

Narrative constitutes the second level of structuralist narratology. This level no longer concerns the abstract logic of sequences but rather the concrete way in which events are presented to the reader. As can be seen in the following diagram, the analysis of narrative consists of three main parts: time, characterization, and focalization.

11. Narrative

2.1. Time

Structuralism analyzes time by studying the relation between the time of the story and the time of the narrative. For instance, a central event in the story may well remain untold in the narrative, or an event that takes a long time to transpire in the story might be mentioned briefly and casually in the narrative. In order to systematize the various aspects of time, Genette uses three criteria: duration, order, and frequency.48

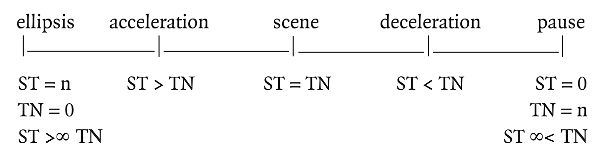

Duration is measured by comparing the time necessary to read the account of an event to the time an event takes on the level of the story. The first of these two dimensions builds on the act of reading in order to determine how long an action or event lasts on the level of narrative. Since these actions and events take place in the narrative as it is being told, this dimension is usually called the time of narration, even though what really matters here is the time of reading. In the next figure presented, this time on the level of narrative appears as TN. The second dimension is usually called narrated time and refers to the duration of events on the level of the story, which is why it appears as ST (story time) below. Since Günther Müller had already introduced the distinction between the time of narration and narrated time in 1948, it existed long before the advent of structuralist narratology.49 Bal distinguishes five possible relations between TN and ST.50 We represent them on a sliding scale as follows:

12. Bal’s sliding scale. Adapted from Mieke Bal, Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative, 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 102.

At the ellipsis pole, an event that does happen in the story is absent from the narrative. As a result, story duration becomes infinitely longer than duration in the narrative. Events that remain untold can be very important. A crime novel, for instance, will effect more suspense when the execution of a planned murder or assault does not appear in the narrative. In a psychological novel, things that remain unsaid can be essential because they may point to repressed or dismissed traumas.

Acceleration is another term for summary. An event that takes a long time can be summarized in one sentence, so that the time of narration is shorter than story time. In “The Map” the narrator says, “and the roads I had not had yet, that is where I went.” The bicycle rides, which must have taken quite some time, are summarized very briefly, which makes the narrative move faster than the story.

Scene indicates an almost perfect overlap of the duration of an event with that of its representation or reading. A dialogue that appears word for word in a novel will take almost as long to read in the text as it takes to utter in the story. The equation sign on the scale, however, is of course a fiction since the time of narration and narrated time are never entirely identical. For instance, it is almost impossible to make pauses in the story conversation last equally long in the text. A brief line such as, “The conversation came to a stop,” is an example of acceleration rather than a scene.

Deceleration occurs when the time necessary to read the description of an event turns out to be longer than the event itself. A text can halt, for instance, at the moment a killer points the gun at a victim. This would take merely a second in the story, but it can be described in dozens of pages. Deceleration, therefore, is very useful for creating or decreasing suspense. An almost scenic description of a fight thus may be followed by a deceleration in which the narrator enters at length into a brief event such as the arrival of the police. The Dutch author Gerard Reve likes to use this strategy: in his novels extended artistic descriptions decelerate the action, which often does not amount to much. Since these descriptions, which circle the unspeakable secret appearing in every Reve novel, are there to justify the passivity of the protagonists, one could say that form adheres to content. At the beginning of Het boek van violet en dood (The book of violet and death), the narrator even makes Reve’s habit explicit: “No, nothing much happens: I meet someone; I meet that someone again once or twice, and then he tragically disappears.”51 The rest of the narrative comes down to one giant deceleration that continuously postpones the little action there is.

Pause represents an extreme form of deceleration. Nothing happens anymore, so the story comes to a standstill. A clear example of this occurs in Max Havelaar, by Multatuli. Stern, the narrator, discusses the precarious balance between the continuing of the narrative and its temporary suspension. By way of example he brings up “the heroine who is leaping from some balcony four floors up.” Instead of describing that action, he brings it to a halt: “Only then, with a bold contempt for all the laws of gravity, shall I leave her floating between heaven and earth until I have relieved my feelings in a detailed picture of the beauties of the countryside.”52 Seventy pages later the narrator returns to the moment when he introduced the pause: “I would give a good deal, reader, to know exactly how long I could keep a heroine floating in the air while I described a castle, before your patience was exhausted and you put my book down, without waiting for the poor creature to reach the ground.”53

The combination of ellipsis, acceleration, scene, deceleration, and pause determines the rhythm of the narrative and contributes to suspense or monotony. Narrative texts with continuous acceleration or deceleration create a much more dynamic impression than texts that always opt for the same type of duration. Sketches such as “Pegasian” mostly go for acceleration, and indeed the riding lesson is described only briefly. “The Map” summarizes an entire period in a few sentences, and it deals with a substantial part of the narrator’s youth in a few paragraphs. This summarizing method of representation is relinquished only briefly in order to describe how the boy sees the map in the shop window. This brief change has an effect similar to that of zooming in with a camera; it enables the reader to concentrate on a specific detail or fleeting event.

When trying to establish duration, the definition of the time of narration presents a major problem. How does one measure the time the narrative devotes to an event? Is that the time required to describe the event or to read about it? It is usual for reading time to function as the norm, but this speed obviously differs from reader to reader. Structuralists then have recourse to a purely quantitative element: the number of pages. Forty pages to describe one minute means deceleration, while one page to describe a year comes down to acceleration. This means that time is reduced to space or more specifically “the amount of space in the text each event requires.”54 By the reduction of temporal development to a certain number of pages, time is stripped of its dynamics. This connects with the already mentioned spatialization characteristic of the structuralist approach.

Another problem with duration is the definition of narrated time. Some narrative texts, such as the nouveau roman and postmodern encyclopedic novels, make it very difficult to reconstruct the story or even the events. In his encyclopedic novel Groente (Vegetables), the Dutch author Atte Jongstra presents a collage of texts taken from manuals, cookbooks, and reference works, and he even includes pictures. This novel no longer has a story made up of chronological and causal connections. How, then, can readers establish the duration of events? If they can’t, it also becomes impossible to search for the relation between the time of these events and that of their description, which means the structuralist definition of duration does not apply here.

A similar problem arises with regard to order. Order is determined on the basis of the relation between the linear chronology in the story and the order of events in the narrative. If it is impossible to reconstruct story events and to arrange them in a clear chronology, order in a narrative text cannot be assessed by using the structuralist method. If it is possible to order events nicely on the story level, for instance in a sequence from one to five, then one can see how the narrative complicates that order, such as in the sequence four, two, five, one, three.

Genette specifies order with reference to three categories: direction, distance, and reach. Specification always depends on a clear primary narrative. This primary narrative or récit premier functions as a norm or, in spatial terms, as a measure for the location of events in time.55 The primary narrative is not the same as the story, because it is visible in the text and does not necessarily contain all the events of the latter. Still, the primary narrative poses the same problem as the story. If a novel does not allow the reader to establish its primary narrative, one can forget about order altogether. A text brimming with associations, such as James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, cannot be approached with this method.

Two directions are possible with regard to the primary narrative: forward and backward. If the primary narrative shows, for instance, the last three weeks in the life of a man who is the protagonist, all memories of his youth and all anticipations of life after death would fall outside this narrative. Such a memory would be an example of analepsis, and such an anticipation would be an example of prolepsis. The equivalent English terms would be flashback and flashforward.56 In German, Eberhard Lämmert popularized the terms Rückwendung and Vorausdeutung.57

If the analepsis or prolepsis concerns the element in the foreground of the primary narrative, Genette calls it homodiegetic. For instance, if a dying man remembers a moment from his own life, this would constitute a homodiegetic analepsis. If, however, he remembers something about a person who does not appear or has only a minor role in the primary narrative, then the analepsis is heterodiegetic. The dying man may remember a boyhood friend who has disappeared, which may lead to a story about that friend and some related details concerning him, none of which the dying man has experienced himself.

Defining direction can often be tricky. Suppose the dying man remembers something from his adolescence but then looks ahead from that period to his twenties. The prolepsis with respect to his adolescence is an analepsis with respect to the primary narrative. “The Map” features a mild version of this: “because I had had all roads, nothing was added anymore, and one day I would remove the map from the wall.” This one day represents a prolepsis with respect to the period in which the boy was biking around but an analepsis with respect to the moment at which the narrator remembers his youth.

The situation becomes more complex when the various memories are not clearly dated. Many autobiographical novels contain a whirl of memories and anticipations that connect associatively and are very hard to locate. In such a case the reader does not know whether memory A goes backward or forward with respect to memory B. Genette uses the term achrony for passages that cannot be dated. Prolepsis and analepsis, on the other hand, exist only if they can be clearly located in time. They are examples of anachrony, a departure from the chronology in the primary narrative.

Order is a matter of not just direction but also distance, which concerns the temporal gap between primary narrative on the one hand and prolepsis or analepsis on the other. The dying man may remember an event that took place two days ago, which therefore falls within the primary narrative, or he may remember something that happened fifty years ago, which clearly remains outside the primary narrative. If the remembered or anticipated period falls within the primary narrative, Genette speaks of an internal analepsis or prolepsis. External is when this period falls outside the primary narrative. And finally there is mixed analepsis or prolepsis, which covers a memory starting before the primary narrative but ending within it, or an anticipation beginning within the primary narrative and ending outside it.

Apart from direction and distance, order is also characterized by reach. This term refers to the stretch of time covered by the analepsis or prolepsis. If the memory concerns one particular event, then the analepsis is punctual. If it constitutes an entire period, the flashback is durative or complete. The analepsis in “The Map” is durative since it describes the complete extent of time from the discovery of the map until its removal.

Although the number of terms enumerated here suggests a rather abstract system, investigating order in a narrative text is of great importance. The more an author indulges in flashbacks and flashforwards, the more complex the narrative becomes. This also leads to all sorts of new relationships between the various periods. If on the same page the text refers to three or four periods from the life of the protagonist, chances are that a reader will start to see connections between these periods. As a result, themes may emerge more clearly or suspense may increase. In Sunken Red, by Jeroen Brouwers, the main character’s thoughts go back and forth between very divergent moments: the Japanese internment camp, the boarding school, the sexual relationship with Liza, the garden party, the birth of his daughter, and the death of his mother. All these stages connect through the joint image of his mother’s disgrace. The turmoil in the novel’s time structure formally reflects the unrest and roaming typical of the I‑character.

Frequency refers to the relation between the number of times an event occurs in the story and the number of times it occurs in the narrative. Obviously there are three possibilities here: less often, more often, and just as often. When the event occurs just as often in the story as it does in the narrative, Genette uses the term singulative. Something that happens once and is described once is a simple singulative, while a reoccurrence in the story that is described just as often in the text is a plural singulative. The discovery of the map in Gerrit Krol’s story provides an example of a simple singulative. If the boy had visited the store more than once, and if each of these visits had appeared separately in the text, then that would have been a plural singulative.

Very often such an exact coincidence does not seem appropriate. If you describe something that happens regularly every time it happens, the text may become monotonous or endless. For story events that happen repeatedly but are presented only once in the text, Genette uses the term iteration. The first sentence of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past offers a good example of this second type of frequency: “For a long time I used to go to bed early.”58 The formulation “for a long time” probably covers thousands of days on which the protagonist went to bed early. Iteratives are prevalent in the description of habits. Here are some examples from “From a View to a Kill”: “Bond always had the same thing—an Americano—Bitter Campari—Cinzano”; “When Bond was in Paris, he invariably stuck to the same addresses”; “After dinner he generally went to the Place Pigalle.”59 In “The Map” the clause “I occasionally traveled somewhere by train” is an iterative since the journey is mentioned only once but will have taken place many times.

Iteratives can be combined with singulatives. A party described singulatively can contain an iterative such as “He repeatedly harassed his neighbor, until she could not take it any longer and left the table.” Genette calls this an internal iterative since it remains within the temporal limits of the singulatively described party. If it were to fall outside these limits, Genette would call it external. For instance, the description of the party could contain a sentence such as the following: “That is what he would do for the rest of his life: harass people who did not ask for it.”

Genette calls the third type of frequency repetition, by which he means the repeated description in the text of an event that takes place only once on the level of the story. Thus the main character in Sunken Red continues to ruminate on the scene in which his mother is beaten by a Japanese soldier. Repetitions of this kind often embody various standpoints, that is to say, the same event is considered by various characters. With postmodern novels it can be hard to decide whether the various standpoints relate to a single event or various events or whether they are sheer invention. Een fabelachtig uitzicht (A fabulous view), by the Dutch author Gijs IJlander, includes several versions of a walk during which a dead animal, possibly a squirrel, is found. The characters entertain widely diverging views of what happened, which may lead the reader to doubt their truthfulness. The narrator, a stuffed squirrel, does not decide the matter, and perhaps the characters’ views are even the animal’s fabrication.60 For such a complex and undecidable case, structuralism, which functions only on the basis of clear event reconstruction, cannot offer a solution.

2.2. Character

Having addressed time as the first dimension of narrative, we now take up character, the second dimension. While story deals with abstract roles, narrative involves their concretization. The central question in this respect concerns the way in which a character is present and represented in narrative.

First, its presence can be grasped in terms of characteristics, which structuralist narratology tends to schematize in a list of features. The most famous example of this is Barthes’s semantic or semic code, which he also calls the character code and which consists of a combination of minimal semantic characteristics (semes). Characters are the result of such combinations: “When identical semes traverse the same proper name several times and appear to settle upon it, a character is created. Thus, the character is a product of combinations: the combination is relatively stable (denoted by the recurrence of the semes) and more or less complex (involving more or less congruent, more or less contradictory figures); this complexity determines the character’s ‘personality,’ which is just as much a combination as the odor of a dish or the bouquet of a wine.”61 In this view “the person is no more than a collection of semes.”62

Later structuralists, like Philippe Hamon in his classic 1972 study of character, will present a much broader view on character.63 They recognize the role of the reader in the semiotic makeup of the character, but even then the list of semes remains the basic level of investigation. Hamon calls that level the “signified of the character,” and he represents the collection of semes in terms of “axes”—such as gender, geographical origin, and ideology—and “functions,” such as victorious battle and reception of a good.64 Again, a character is described as a list of characteristics.

The second aspect of the character is more dynamic and focuses on the way it is presented in the narrative. Hamon deals with this aspect in two ways: he looks at the character as signified, that is, the form given to the character (e.g., its name), and at the rules that this formulation has to follow (e.g., rules of logic, common sense, and genre). This leads to a complex frame that is hard to use for the practical study of characters and combines the levels of narrative with that of narration. As a consequence, we will start from a much simpler view on characterization, the one offered by Rimmon-Kenan, who discerns three ways of characterization.65

First, a character can be described directly.66 This type of characterization occurs in many traditional novels that introduce a character with an enumeration of character traits. These traits may relate to psychological states as well as to outward appearance. Direct characterization always takes the form of specifying and evaluative statements such as the following: “Mister Hoorn was a warm and honest individual, though his casual conversation and jokes could not be called brilliant. But stupid, no, that he was not.”67

A central question in this connection relates to the origin of such statements. Does the character itself pronounce them? Or do they come from an omniscient narrator, or another character? The answers to these questions have a profound influence on the reliability of the characterization. Direct characterizations belong to the most straightforward strategies to inform the reader, but they can easily be (ab)used to send the reader in the wrong direction. At the beginning of the story “A Rose for Emily,” by William Faulkner, the characterization of “noble” Emily is emphatically positive, but the reader soon realizes that those positive statements are inaccurate and misleading.68

The second type is indirect characterization.69 This type is based on metonymy, that is, it works with elements that are contiguous with the character. Actions, for instance, often follow naturally from a character’s identity. Discourse too says a lot, literally and figuratively. The words and style used by characters betray their social position, their norms and values, and their psychology. The characters’ physical appearance and their environment can be telling too. Ben, the main character of Ansichten uit Amerika (Postcards from America), by Willem Brakman, moves to new residences a number of times, but his environment continues to resemble a labyrinth. His house is “very intricately designed,” and the streets form an obscure network and “become hard to follow.” The phrase “labyrinth of small streets” comes up in all sorts of contexts related to Ben.70 It therefore says something about the claustrophobic and paranoid worldview of this character.

Third, characters can be described with the help of analogy, which leads to metaphor instead of metonymy.71 In “Pegasian” the main character’s identity is partly established through implicit comparison with the horse. Just like the horse, the female rider wants to break free from the ground and take off. The latter refers to the text’s message. The fact that metaphors often refer to a specific ethic or ideology also appears in Theodor Adorno’s study of the images Kafka uses to describe his characters. Kafka often compares his characters to animals and objects, and this metaphorical typification shows how unhuman humankind has become.72

For Rimmon-Kenan the name is an example of characterization through analogy.73 To the extent that the name points to an aspect of the character or to a contiguous element pertaining to it, we believe it still belongs to metonymic characterization. Thus, the names Goodman and Small describe metonymically, whereas Castle or Roach do so metaphorically. In the former case, elements are put forward that belong to the semantic domain of humankind, while in the latter case, other domains come into play. In the novel Bint, by the Dutch author F. Bordewijk, the pupils of a class called “Hell” have suggestive names such as “Saint’s Life” and “Precentor.” Such metaphorical or symbolic names may of course refer to the opposite of what they suggest. A character called Castle may well be weak, in which case the name is ironic, to say the least.

Similar to the name, the alter ego or second self presents a borderline case between metonymical and metaphorical characterization. Metonymical characterization does not lead to osmosis, while its metaphorical counterpart does. The borderline between the two is not always clear. Two supposedly distinct characters may resemble each other in so many ways that one could still speak of identification or blending. This is true, for instance, of the alter egos in De ontdekking van de hemel (The discovery of heaven), by Harry Mulisch. Uri Margolin mentions the example of a character blending with an axolotl, a type of salamander; the two exchange personalities.74 This obviously underscores the dynamic aspect of characterization. Margolin distinguishes between three types: a transformation within one character, an evolution between two or more characters (which leaves the number of characters unchanged), and finally a change in the number of characters (e.g., by cloning or schizophrenic splitting).75

The structuralist penchant for abstract and unchanging deep structures goes against the concrete and dynamic nature of characters and characterization. This difficulty is borne out, for instance, by the impossibility of defining what actually constitutes a hero. Bal has drawn up a list of characteristics, including “the hero occurs often in the story,” “the hero can occur alone or hold monologues,” “certain actions are those of the hero alone,” and the hero “maintains relations with the largest number of characters.”76 A relevant question is not only how many of these characteristics have to apply before one can speak of a hero but also whether the hero concept is at all relevant for nontraditional texts, such as the nouveau roman, or for classical genres, such as the epistolary novel and the novel of manners. In the nouveau roman the hero seems to disappear in favor of an impersonal quasi objectivity; in the epistolary novel, all correspondents being more or less equal, there is no center; and in the novel of manners intense interaction between groups and classes makes a criterion such as “certain actions are those of the hero alone” irrelevant.

More generally, one might ask whether a narrative text always needs a hero. If the answer is yes, a good starting point may be Philippe Hamon’s approach. He enlists a number of narrative characteristics that are typical of heroes; they have qualifications that are unique to them (or at least unique in that particular degree); they have a wide spatial distribution (i.e., they appear often and in many places); they often appear autonomously and on their own; they have functions and can perform actions that are not equally distributed among the other characters; they are often designated by genre conventions and/or by explicit characterizations as “the hero”; and finally, there is a certain abundance and even redundancy in their characterization. However, even these dimensions are not objective and universal criteria for deciding whether or not a character is a hero.77 The role of the reader cannot be disregarded here.

The fact that structuralist narratology holds on to concepts such as hero and villain suggests that it still deals with characterization in a very anthropomorphic way.78 Coming from a theory that explicitly dissociates itself from subjectivist and humanist approaches to literature, this may be surprising. Indeed structuralists do not like empathic readings, which analyze the emotions displayed in the text. And yet they too risk treating constructs of words as people. In postmodern novels characters lose many of their human traits: they blend into one another, they say they are inventions of a narrator or of the text, they disappear as suddenly as they appear. Structuralism hardly knows what to do with such nonanthropomorphic characters, which proves the extent of its remaining anthropomorphism.

2.3. Focalization