Tracks are what is left behind; they bear witness to something that was never there, but always departing, disappearing…They are vestiges of the stride and the instant between strides. To notice them, to retrace them, to make sense of them, is to engage with the leftovers of history and to harness their potential to indicate different paths into the future.

POINTING FINGERS

For Du Fu, traces are not necessarily solid. Structures like the “palaces of Chu” might disappear altogether, but the clouds and rain that cloak Mt. Wu linger on. As traces of the divine made famous by Song Yu, these atmospheric phenomena continue to shape how travelers see and imagine the Three Gorges. In the second poem of Du Fu’s “Singing My Feelings on Traces of the Past 詠懷古跡,” the guji 古跡 is something the poet embodies—a fragment of the past inscribed in the self. What literal-minded travelers fail to recognize when they ask boatmen to point out the palaces of Chu or when they search for Song Yu’s house is that they are traces of the things they seek. Over the course of the Northern and Southern Song dynasties (960–1279), Du Fu became the object of many such seekers, men who searched the landscape for places he had occupied and about which he had written. Some reconstructed buildings associated with the poet, establishing them as sites of literary pilgrimage and worship; others physically inscribed his poems in the landscape. Equally inspired by his fame as a poet and as a moral exemplar, they altered the landscape to make his traces legible or to produce legible traces where none could be found. In the process, they tried to fix the shifting traces of Du Fu’s world, reinscribing them as sites that could be easily identified and visited, a process that continues to this day.

Writers, including Du Fu, had long been interested in locating and describing famous historical sites, but it was during the Song Dynasty that ji became the object of systematic textual and empirical research as part of a larger revolution in spatial thought. The new “modes of space making” that Song scholars developed “formed the basis for spatial ideas throughout the rest of the imperial era and beyond.”2 Their reinscription of the Three Gorges as a landscape of sites was supported by a group of related literary forms—local and empire-wide gazetteers (fangzhi 方志 and zongzhi 總志, respectively), the travel essay, and the travel diary (both youji 遊記)—the development of which coincided with the elevation of Du Fu to the pinnacle of the literary pantheon. According to Eva Shan Chou, Du Fu’s reputation as poet and cultural hero crystalized during the Northern Song (960–1127) as part “of a larger contemporary preoccupation with self-definition, in which Northern Sung [sic] literati sought precedents in the figures of the past.”3 Literati turned mostly to texts for these precedents, but they also sought more tangible links. By searching out what Paul Carter calls the “leftovers of history” in landscapes that were already well known through texts and images, they reinscribed familiar spaces in order to create “paths into the future” by way of the past.

Thanks to his prestige as well as the large number of poems he wrote in and around Kuizhou, Du Fu figures prominently in Song geographical and travel writing on the Three Gorges region. When describing sites directly associated with Du Fu, authors are careful to locate them in relation to the contemporary landscape (as “X miles from the city wall,” for example). When introducing topographical features or other sites of interest, they often cite Du Fu’s poems, not only to add literary depth to their spatial description, but also to give readers a concrete sense of places they might only know through poetry. Du Fu’s role in these texts makes him an indispensable figure for understanding how the Three Gorges region has been reinscribed and reconceptualized over the last millennium. This chapter explores this process by looking at two sites that appear frequently in Du Fu’s poetry: his “Lofty Retreat” (gaozhai 高齋), which was located in the village of Dongtun 東屯 on the outskirts of Kuizhou; and Mt. Wu (Wushan 巫山), the tallest peak in the Wu Gorges and mythical home of the goddess of Mt. Wu.

“Lofty Retreat” (gaozhai 高齋) is the name Du Fu gave to three different homes he occupied in the Kuizhou area. By triangulating the status of his Dongtun “Lofty Retreat” in the eighteenth century, the present day, and the twelfth century, I show not only how the fixed site comes to supplement (and in some cases supplant) the immaterial trace in the cultural imagination, but also how the contemporary spatial reorganization of the Three Gorges has inspired a newly pressing interest in locating remnants of the past. My second site, which takes us away from Du Fu, is Mt. Wu, the supposed setting for Song Yu’s “Gaotang Rhapsody” (Gaotang fu 高唐賦), in which an ancient Chu king sleeps with a goddess in his dreams. The most famous erotic figure in early Chinese poetry, the goddess of Mt. Wu (Wushan shennü 巫山神女) remains a symbol of otherworldly sensuality. Beginning in the Tang Dynasty, and gaining momentum during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), however, a small number of writers worked to sanitize her mythology. Attempts to reform the goddess were based not only in the reinterpretation of Song Yu’s rhapsody, but also in the study of texts that recounted her role in helping Yu the Great bore through the Three Gorges and in the reappraisal of conventionalized descriptions of the landscape of Mt. Wu. Writers who traveled to the region cast a skeptical eye on Mt. Wu and the Wu Gorge, comparing what they saw with what they had read in order to render the landscape spatially and morally unambiguous. Both Mt. Wu and Du Fu’s house at Dongtun provide vividly realized examples of how ephemeral and ambiguous traces of the kind that characterize Du Fu’s Kuizhou poetry have been fixed as legible and enduring sites in the more than twelve hundred years since his death.

FROM ANCIENT TRACE TO FAMOUS SITE

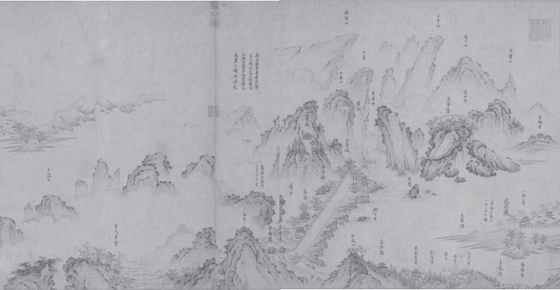

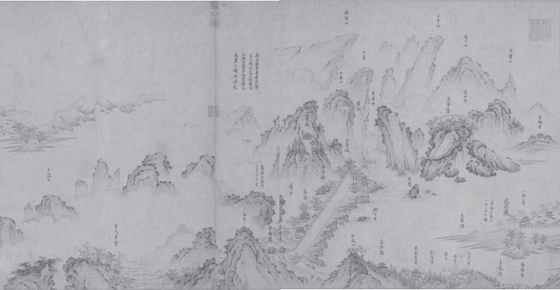

The embrace of the clearly defined “site” over the more ambiguous “trace” (both ji 跡) required clear physical referents for textual knowledge—things to point at and visit, even if only in the mind’s eye. When the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) emperor Qianlong 乾隆 (r. 1735–1796) sat down to admire The Shu River (Shuchuan tu 蜀川圖), a prized Song Dynasty painting of the Yangzi River as it flows through Shu (modern Sichuan), for example, it was the clear labeling of sites of special interest that inspired him to inscribe Du Fu’s “Autumn Stirrings” in an open space near the upper edge of the handscroll:

Historical sites [guji 古跡] are so clear they can be picked out one by one [lili keshu 歷歷可數]. Imagining [xiang 想] old Du in his river pavilion wielding his brush, my inspiration was by no means shallow, so I inscribed his poems on the scroll to mark [志] them as paired treasures.4

For Qianlong, who was steeped in the literary traditions of Shu (modern Sichuan), the clarity of the textualized landscape, which allows him to “imagine” Du Fu in his riverside home, comes not from the painter’s success in capturing the likeness of famous landmarks, but from the addition of 189 written labels that offer the kind of information one finds in gazetteers and maps, including place names and historical landmarks, distances between major towns, brief descriptions of how place names have changed since the Tang, and citations (or, in some cases, paraphrases) of important geographical texts such as the Commentary to the Classic of Rivers and the ninth-century Treatise on the Prefectures and Counties of the Yuanhe Era (Yuanhe junxian zhi 元和郡縣志) (figure 2.1).

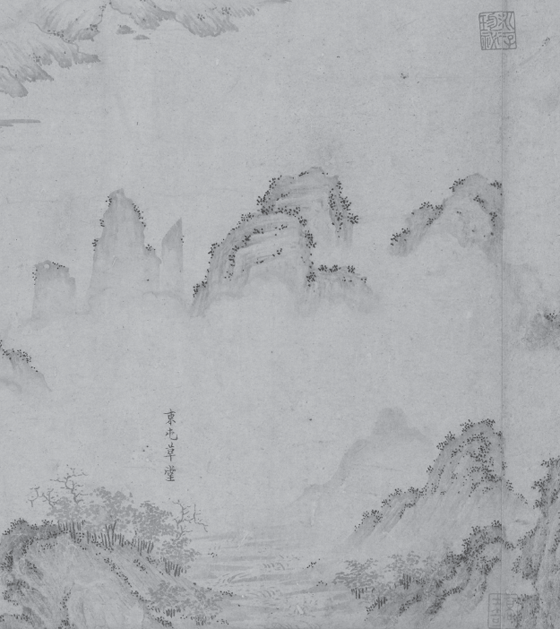

FIGURE 2.1 The Shu River (Shuchuan tu 蜀川圖) (detail), attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 (ca. 1041–1106). This portion of the scroll contains the walled city of Kuizhou, labels for Du Fu’s “lofty retreat” and his home at Dongtun (see figure 2.2), Baidicheng, Qutang, and a host of other local landmarks. See also color plate 4.

Source: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1916.539

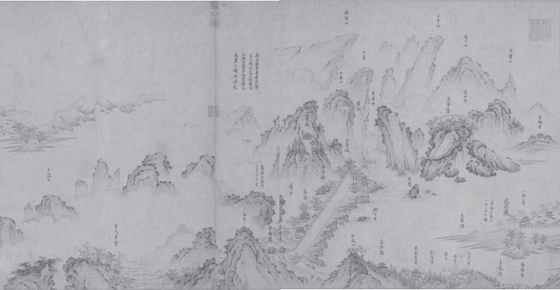

While many of these labels are inscribed over carefully rendered topographical features, such as the mountains that form the Qutang Gorge, or well-known cities, such as Kuizhou, others are simply placed within the negative space that the artist uses to represent the river or cloud-covered mountains. The label for Du Fu’s thatched hall at Dongtun, for example, seems to hang in the air of an empty valley, just beyond the walls of Kuizhou (figure 2.2). Brought to life by texts that have long mediated the materiality of the region, The Shu River in turn reanimates those texts by providing a panoramic landscape in which to inscribe the sites they describe or at which they were written. That many of the painting’s labels mark sites that are not represented suggests that learned viewers would have been able to produce their own mental images, images that might inspire the further inscription of the painting, as was the case for Qianlong. The Shu River is both an object combining pictorial and textual approaches to geography and an object for aesthetic use—not simply something at which to look and point, but an object inscribed and inscribable.

FIGURE 2.2 The Shu River (detail): The label for Du Fu’s “Dongtun thatched hall.”

Source: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1916.539

Qianlong, who is famous for writing on many objects in his vast collections, was more than a little inspired by The Shu River. Altogether, his additions on the painting and in colophons that follow it total more than seventeen hundred characters and include not only the complete text of the “Autumn Stirrings,” but also two quatrains, a number of prose passages, a small painting of a flowering plum branch, and two long poems. The second of these long poems, a 406-character heptasyllabic poem from June 19, 1746 (the same day he inscribed the “Autumn Stirrings”) restages a viewing of the painting by tying its landmarks to the historical, mythological, and literary figures associated with them. It treats the landscape painting as a mnemonic device that evokes Shu not through mimetic representations of its landmarks but through the inscriptions that label those landmarks, including those associated with Yu the Great’s feats:

| 岷山導江幾千里 |

The Min Mountains channel the Jiang for thousands of li |

| 神禹底績猶堪指 |

The God Yu’s feats of merit can still be pointed out5 |

Beginning with this opening couplet, Qianlong’s poem synthesizes the experience of simultaneously reading and viewing the painting, while also providing a hint of what that experience might have looked like—a group of learned men leaning over a prized painting and excitedly pointing out (zhi 指) sites of interest. They point to identify what Qianglong calls guji古跡—traces of the past or historical sites—but which might be more accurately termed shengji 勝跡—“famous sites” rich with cultural meanings brought to life by the knowledgeable viewer. Guji and shengji are sometimes used interchangeably, though they describe slightly different kinds of ji. Scholars have suggested a range of translations for guji, including “heritage sites,”6 “traces of the past” (which sometimes refer to places that no longer exist),7 “ancient sites,”8 and “historical trace[s] in a narrow sense.”9 Shengji, which Wu Hung translates as a “renowned place,” generally refers to a site of scenic or historical interest (or both), “which has become a persistent subject of literary and artistic commemoration and representation.”10 Though guji and shengji overlap in meaning and usage, shengji refers more consistently to physical sites that make up a particular landscape. They may be associated with specific figures or literary moments, and may even take the form of ruins, but they are generally well-defined landmarks enriched by “countless layers of human experience.”11 If the aesthetics of guji depend on a spatialized historical consciousness—a sense of one’s relation to and distance from a particular past—the aesthetics of shengji are based in an appreciation of how the well-defined historical trace contributes to a sense of place in the present.

As a form of imaginative spatial production centered on famous sites, Qianlong’s virtual journey creates a powerful sense of place through text and image. While “sense of place” normally connotes an affective, phenomenological, and cultural connection to one’s immediate surroundings, here it describes an appreciation for place mediated by the textual and visual expressions of other people.12 It is this sense of place that inspires the emperor to further mediate the landscape through a creative act of poetic chorography that links the painting’s sites into a journey that is simultaneously literary, spatial, and historical. This is possible because Qianlong has access not only to poetic works such as Du Fu’s “Autumn Stirrings,” but also to geographical writings designed to fix famous sites in time and space. If his appreciation of Du Fu’s poetry puts him in the long tradition of ji as aesthetic and affective stimuli, his use of the latter hints at how ji functioned as physical sites in spatial thinking in the millennium following the fall of the Tang.

In his long poetic journey and introductory inscription, Qianlong alludes to many such sites, including Du Fu’s former home in Chengdu and his “river pavilion” (jiangge 江閣). By the mid-eighteenth century, Du Fu’s homes and the Three Gorges sites he had written about had been important landmarks for over six hundred years. What distinguishes the posthumous status of Du Fu’s homes from that of the many historical traces Du Fu wrote about, is that the former were defined by literary and visual forms that drew on post-Tang empirical research methods to fix ji as geographically locatable sites. The men who produced such texts, guides, maps, and paintings might have been inspired by Du Fu’s depiction of the Three Gorges as a literary landscape made up of a patchwork of immaterial traces, but they sought to identify and reinscribe Du Fu’s own traces as part of a landscape of sites. In our own time, some scholars, inspired perhaps by the urgent timeline of the rising waters of the Three Gorges reservoir, which reached capacity in 2009, have revived these reinscriptional practices as part of their own attempt to fix, once and for all, the “present location” (xiandi 現地) of Du Fu’s Kuizhou homes or the palaces of Chu that appear in the second of his “Singing My Feelings on Traces of the Past” poems.

In a 2000 article published in the Chinese-language Journal of Du Fu Studies, for example, Tan Wenxing 譚文興 launched an extended critique of a book titled A Study of the Current Locations of Sites in Du Fu’s Kuizhou Poetry, by the Taiwanese scholar Jian Jinsong 簡錦松.13 Jian’s is the first monograph dedicated wholly to identifying the present locations of sites associated with Du Fu, including his Kuizhou homes at Dongtun and Rangxi 瀼西.14 It draws on an extensive body of geographical writing, including travel essays, diaries, and gazetteers, as well as close to a millennium of commentaries on Du Fu’s poetry, scientific literature on the hydrology of the Yangzi, reports produced by the Three Gorges Dam Project, historical and contemporary maps, and on-the-ground research carried out before completion of the dam. Jian’s goal is to break free from what he sees as the circular logic common among Mainland Chinese scholars such as Tan Wenxing, most of whom, he argues, rely on unscientific, error-prone commentarial traditions to identify the present-day locations of sites associated with Du Fu.15 Tan’s critique, in turn, takes Jian to task for contradicting himself and failing to read Du Fu’s poetry with sufficient care.

The substance of this cross-strait argument is less compelling than the shared ideas that underlie it. Despite their disagreements, Tan and Jian are both participating in a contemporary, GPS-calibrated version of the premodern search for precisely located and authenticated sites. The precision that they seek does not contribute to a more sophisticated understanding of the spatiotemporal logic of the ji/trace in Du Fu’s poetry. Instead, xiandi research operates according to the primarily spatial logic of the famous site or shengji, though it seems oblivious to the possibility that its acts of location are also acts of spatial inscription. Like the sources on which it draws, xiandi research contributes to the ongoing production of local, regional, national, and cultural landscapes as constituted by sites of special interest. My point in drawing attention to this approach is not, of course, to rebuke it with the counterclaim that Du Fu’s poetry is pure invention.16 What the literal-mindedness of xiandi scholarship excludes is the way that Du Fu layers citation or “bookish landscapes” together with the fevered visions of memory and the physical geography of Kuizhou.17 The sites that xiandi scholars seek to fix were not fully fixed in Du Fu’s poetry—they were “always departing, disappearing.”18 That is the source of their power. They were experienced by the ailing poet as part of an almost hallucinatory itinerary that led, across a sea of stars or an expanse of water, to other times and other places.

⋆

Though they are heirs to the same Song Dynasty revolution in spatial thinking, today’s xiandi scholars and the Qianlong emperor do very different things with their knowledge of physical sites associated with Du Fu. In 1746, Qianlong and his companions approached The Shu River with a “spatial historical consciousness” that held the scholarly search for concrete sites and the evocative poetics of the ji/trace in balance as part of a creative enterprise combining calligraphic inscription, poetic composition, and painting.19 When Qianlong envisions Du Fu’s river pavilion from the luxurious confines of his Beijing palace, he begins a lyrical-inscriptional detour (by way of the “Autumn Stirrings”) that opens onto Kuizhou and the Three Gorges. Although he dedicates a few lines to the region in his long 1746 poem, the emperor does not describe his vision of Du Fu and his home in any detail. It is only at the end of the collection of colophons that follows The Shu River—where we find an image by the court painter Ding Guanpeng丁觀鵬 (active ca. 1740–1768)—that we get a full sense of how the lyrical immediacy of the Kuizhou landscape interacts with the narrative of the regional panorama of sites.

Ding’s painting (figure 2.3), produced by command of the emperor, is meant to capture the “poetic intention” (shiyi 詩意) of the final couplet of Du Fu’s second “Autumn Stirrings” poem:

| 請看石上藤蘿月 |

Look! the vine and creeper moon that was atop the rocks |

| 已映洲前蘆荻花 |

Shines already on the reed flowers before the islet |

FIGURE 2.3 Ding Guanpeng’s illustration of the final couplet of Du Fu’s second “Autumn Stirrings” poem.

Ding’s interpretation of these lines takes the form of a moonlit scene in which Du Fu stands on a riverbank looking across the water toward a rocky outcropping, a vine-choked pine tree, and the reflection of the moon in the water. To his right, a fisherman in midstream rows toward the bank; to his left is a small group of partially visible buildings. Whereas The Shu River presents an imagined panorama of the Yangzi as it flows through Sichuan—a massive geographical, historical, and administrative region synthesized as a unified cultural scene—Ding’s painting draws on a more intimate landscape style to present the unfolding of a single lyrical moment.20

In chapter 1, I characterized the shifting light in Du Fu’s second “Autumn Stirrings” poem as an immaterial trace with multiple valences—a reflection of the moon, a manifestation of time’s passage, and a reminder of the temporal and spatial chasms that keep him from where he so badly wants to be. For Du Fu, fragments of his past appear and disappear on the surfaces of the Three Gorges like light and shadow cast by the moon. In his visualization of this particular moment, Ding does not try (and indeed cannot hope) to capture the alternation of appearance and disappearance, fullness and emptiness that define the “Autumn Stirrings.” Instead, he focuses on giving shape to Du Fu’s immediate surroundings, including a cluster of buildings, one of which might be the “river pavilion” that first inspires Qianlong’s lyrical detour through the Gorges.

Partially obscured at the edge of the image, these structures link Ding’s painting, Qianlong’s inscriptions (both of which refer to Du Fu’s homes), and the larger landscape of The Shu River (on which Du Fu’s homes in Chengdu and Kuizhou are labeled). Though it retains the historical significance of a guji, Du Fu’s home also functions here as a shengji that is legible as part of a larger cultural landscape of sites comprising the region of Shu. This is precisely how Ding describes The Shu River in a short text that accompanies his painting: “in a single glance across one thousand li of river and mountains nothing is omitted. Each and every noted site and famous region [shengji mingqu 勝蹟名區] follows one after the other in an instant [zhigu jian 指顧間].” The literal meaning of the colloquial phrase, zhigu jian 指顧間, which I have translated as “in an instant,” is “within the time it takes to point and nod.” Just as Qianlong describes pointing out (zhi 指) the physical traces of Yu the Great in his long poem, Ding reminds us that ji are not simply evocative sources of artistic inspiration but also objects in and of the landscape—sites to be pointed out or nodded at while traveling along the river.

FINDING DU FU AT HOME

It is easy to see how thoughts of Du Fu’s home might inspire artistic acts or contribute to a general sense of the Three Gorges as a culturally important landscape. What is not immediately obvious, however, is the extended process by which Du Fu’s home came to be imbued with carefully determined cultural values. During the Song, travel writers and local officials began to produce essays and other texts centered on structures that were presented by locals as Du Fu’s former homes. These same structures appear in empire-wide gazetteers of the thirteenth century, such as Zhu Mu’s 祝穆 (d. after 1246) Fangyu shenglan 方輿勝覽 (first published 1246), and in local gazetteers for Kuizhou, the earliest extant of which was published in 1512.21 Gazetteers are encyclopedia-like texts in which the topography, mythology, history, economy, literature, and other aspects of a county or prefecture were collected and categorized to produce an epistemology of place designed not to question, but to bolster, local claims to fame.

Though their approaches to Du Fu’s homes vary, the scholars and officials who compiled gazetteers and composed travel essays and diaries worked to locate them not just historically, but also spatially, in relation to the landscape of Kuizhou in their own time.22 For more skeptical authors, this sometimes meant questioning local claims, as the famed statesman, diarist, and poet Fan Chengda 范成大 (1126–1193) did when he moored his boat at Baidicheng on August 14, 1177:

My fellow travelers [and I] went to Qutang to sacrifice [si 祀] to the White Emperor and to climb to the Three Gorges Hall and visit the Lofty Retreat, all within the old fort [at Baidicheng]. Although the Lofty Retreat is not necessarily the one about which Du Fu wrote, it still overlooks Yanyu Islet and affords a spectacular vista.23

This entry comes from Fan’s Record of a Wu Boat (Wuchuan lu 吳船錄), one of the earliest and best-known examples of the long-length travel diary genre (youji 遊記).24 It not only exemplifies the skepticism of certain forms of travel writing that became popular during the Song, it also provides evidence of the common practice of making historical claims for preexisting structures or even building new structures and identifying them as the “former residences” of famous figures. While the status of the “lofty retreat” is of only passing concern to Fan Chengda, for other Song travelers and officials, Du Fu’s homes were objects of special interest. During the long period of comparative neglect between his death and literary resurrection, however, the physical landmarks associated with his life in Chengdu, Kuizhou, and a host of sites were allowed to decay. Not yet enshrined as “former residences” of a figure of great fame, they were treated like normal buildings and often fell into disrepair. Some of them, including Du Fu’s famous Chengdu thatched hall (caotang 草堂), which was restored by Lü Dafang 吕大防 (1027–1097) in the eleventh century, or his Dongtun “lofty retreat” in Kuizhou, were rebuilt as memorial structures, sites of pilgrimage for the devout reader.

The story of Du Fu’s literary influence is well known. What has been less thoroughly studied are the complex processes by which the unfolding of that influence, over generations of writers and readers, contributed to the reinscription of Du Fu’s poetic traces as coordinates comprising an itinerary of physical sites and landmarks. And what has been almost entirely ignored are the representational and material effects of this mapping, which slowly reconfigured how certain visitors perceived and experienced the landscape of the Three Gorges. The most direct way in which these processes reconfigured the landscape was through simple architectural intervention. Men like Lü Dafang, who rebuilt Du Fu’s Chengdu thatched hut, sought to reestablish a lost material connection to Du Fu by reconstructing the structures in which he had lived. To produce a sense of place often entailed physically reshaping the landscape and its built structures. This is not to say that “new” structures were seen as fake. Their authenticity depended on their status as sites of ritual and cultural practice, activities that created a powerful connection with the deceased figure of fame.

Physical acts of spatial production were often bolstered by short essays (categorized as ji 記, or in some cases, youji 遊記) written by local officials.25 The literature of sites of interest was designed not only to promote the local, however. In many essays, the reinscription of the ji serves as a way to instantiate important values spatially, as in Lu You’s 陸游 (1125–1210) 1171 essay, “An Account of the Dongtun Lofty Retreat” (Dongtun gaozhai ji 東屯高齋記), which begins as an exercise in locating and attempting to adjudicate the current status of Du Fu’s three Kuizhou Lofty Retreats.26 Part of a larger class of what Lu You calls “lingering traces” (yiji 遺跡), each of these structures is associated with a specific section of Tang Kuizhou, a complex space comprised of walls, temples, and markets that no longer exists. Like all of these structures, Du Fu’s homes were not only located within Kuizhou and its environs, they also helped to constitute those now absent places. According to Lu You, at Baidicheng and Rangxi the physical substrate necessary for even the faintest of traces has been totally effaced.27 The only spot where it is still possible to envision both the location and surroundings of one of Du’s Lofty Retreats is at Dongtun, though Lu You says nothing of actual ruins and provides very little evidence for his conclusion.

The link that he does establish is through one Li Xiang 李襄, whose family has lived in Dongtun for several generations and who claims to possess ancient scrolls from the Dali 大曆 reign period (766–779). These scrolls are perhaps the only things actually “still there” (youzai 猶在) from Du Fu’s time in Kuizhou. But what exactly do they have to do with the Tang poet? Are they manuscript copies of his work, perhaps in his own hand, or are they land deeds bearing his signature? Lu You does not answer these questions, but it is clear that the Dali era scrolls play an important role in confirming the spatial and temporal continuity of Du Fu’s presence in Dongtun. As objects from Du Fu’s lifetime, they differentiate Dongtun from Baidi and Rangxi as a place that still bears legible traces of the past, thus offering a site suitable for “visiting and mourning” (diao 弔). These objects are paired with a description of the surrounding area, which is “very reminiscent” (liangshi 良是) of that found in Du Fu’s poetry. As in the opening section of the essay, where Lu You judges Li Xiang’s property against the place described in Du Fu’s poetry, text and landscape are correlated as a way of locating people in space and time.

Lu You’s focus on Dongtun is largely a function of what he claims is the original object of the essay—to “make note” (ji 記) of Li Xiang. Unlike Du Fu, who was an ambitious “man of the world” (tianxia shi 天下士), Li Xiang never even set off on the road to glory, thus avoiding suffering and humiliation. Instead, he chose to stay in place, living as a recluse without having had to seek office and then retire from the world. In this, he continues his connection to Dongtun and maintains the agricultural base necessary for a life of contemplative leisure. By comparison, Du Fu was unable to stay in Dongtun for the span of a single year. Lu You thus implicitly judges Du Fu a failure (shi 失) and Li a success (de 得) in navigating the travails of life while maintaining righteousness and propagating a family line. There is a clear irony to this: not only does the majority of the essay, ostensibly about Li, center on Du Fu, but the text itself is proof of the immortality that literary fame offers. From a certain perspective, Lu You’s essay is about the relative merits of different methods of “turning death into life” (shi si fu sheng 使死復生), ways of maintaining some form of presence in the face of absence. Li Xiang has achieved this by staying in place and becoming an integral component of the landscape of Dongtun. In contrast, Lu You’s failure to find hard evidence of any of the other Lofty Retreats renders Du Fu’s immortality almost totally immaterial. Only at Dongtun, where the poet is evoked by the landscape and the “ancient scrolls” embedded there, does he finds something worthy not only of mourning, but of “expending the effort” (chuli 出力) to memorialize.

If the Dali scrolls are a textual surrogate for the poet, allowing the Li family to legitimate their Dongtun property as an authentic ji, then Lu You’s essay functions as a textual surrogate for readers who are unable to access Du Fu’s “lingering traces” in person. It fulfills this function not by recounting Lu You’s travels around Kuizhou or providing a description of the Lofty Retreat—as the essay’s title seems to promise—but by memorializing the values embodied by Li Xiang and Du Fu and embedded in the landscape of Dongtun. By making Li Xiang a mirror image of Du Fu—possessing a similar loftiness but a different fate—Lu You goes as far as he possibly can with the tools at his disposal towards reinscribing Du Fu in Dongtun. Those tools—the essay, brush, paper, printing, communities of readers and writers—create a sense of Dongtun as a cultural and historical place that can circulate textually throughout the realm. Text not only diffuses the ji, however; it also helps to fix it as an empirically authenticated site while also offering clear spatial details that allow readers to visit it in person, if they so desire.

Essays like Lu You’s reinforce the relationship between people and places, but they only reflect one aspect of the reinscriptional practices that shaped the Three Gorges during the Song. Another aspect is the rebuilding of ancient structures or “former residences” (guju 故居) to serve as sites of pilgrimage. What Lu You does not tell us is that Li Xiang’s residence was just such a reconstruction. For this information, we must turn to an 1197 essay by the Kuizhou official Yu Xie 于𤈱28 (fl. later twelfth to early thirteenth century):

After Shaoling left the Gorges, his land changed owners three times. In recent times it came into the possession of a certain Li family, and scrolls in Du Fu’s hand were still there. Eventually, it [passed to a] son [of the Li family], Li Xiang, who was inclined to good deeds [po haoshi 頗好事] and interested in ancient sites [jiangqiu guji 講求古蹟]. [Li Xiang] once again reconstructed a Lofty Retreat, and, in imitation of the old fellow of Fuzhou’s [efforts to] spread the reputation of Shaoling’s poetic intent, built a Hall of the Great Odes [daya tang 大雅堂]. Overlooking a stream he also built a thatched hall and painted his [Du Fu’s] posthumous portrait. Many years having passed, the roof had fallen into disrepair and was left unrepaired, the scrolls too had been spirited away by someone wielding great power and this former refuge of a past worthy had been all but reduced to a mound of brambles and shrubs [jingzhen zhi xu 荊榛之墟].29

From Yu Xie we learn that Li Xiang was worthy of praise not simply because he led an exemplary life of seclusion, but because he created a popular tourist attraction dedicated to Du Fu, complete with a reconstructed lofty retreat, a thatched hut containing Du Fu’s portrait, and a Hall of the Great Odes, modeled on another Sichuan structure that contained inscriptions of all of Du Fu’s Kuizhou poetry in the hand of Huang Tingjian 黃庭堅 (1045–1105), “the old fellow of Fuzhou.” Li was more than simply “interested in ancient sites”; he created one to serve as a shrine to Du Fu. His Shaoling Shrine (Shaoling ci 少陵祠) was by no means unique, however. According to a dictionary of place names in Du Fu’s poetry, there have been at least eight Shaoling Shrines throughout China, some of which are still active today.30

Perhaps the most famous of all monuments to Du Fu was the Hall of the Great Odes (daya tang 大雅堂) that Li Xiang imitates in Dongtun. The original hall was built in 1100 by Yang Su 楊素, an official in the Sichuanese city of Danleng, in order to fulfill Huang Tingjian’s desire to “write out all of Du Fu’s poems on the two Chuan and the Kui Gorge and have them inscribed on stone.”31 In the essay he wrote to commemorate the construction of the hall, Huang complained that readers who “delight in making far-fetched interpretations [chuanzao 穿鑿; literally, drilling and boring], discarding [a poem’s] greater purpose [dazhi 大旨] and grasping after its inspiration [faxing 發興], believing that each and every object with which they meet—forests and springs, men and things, grasses and trees, fish and insects—is imbued with allegorical significance [yousuo tuo 有所託]…are like those who guess at riddles and codes.”32 For Huang, the hall is meant to reverse the decay of a literary and moral culture (siwen 斯文) grounded in the ancient Book of Odes (which contains a section titled “Great Odes”) and the Songs of Chu, but “lost” (weidi 委地)—literally “cast into the dirt”—since Du Fu’s death.

Just as Yu Xie and his peers would “resurrect” (xing 興) the Dongtun lofty retreat from a “mound of brambles and shrubs” at the end of the twelfth century, Huang Tingjian and Yang Su sought to reverse the loss of a shared literary culture by inscribing Du Fu’s poems in stone and embedding them in Sichuan at the beginning of the century.33 Cultural decay is figured in both cases as a process of ruination that marks a tipping point in a cyclical pattern leading to revival. In Yu Xie’s essay, the character I have translated as “mound”—xu 墟—is also one of the most common words for what we might call a “ruin.” According to Wu Hung, the xu that appeared in premodern poetic and pictorial contexts was most often “an empty site…[that] generated visitors’ mental and emotional responses not through tangible remains,” but rather by stimulating their historical consciousness.34 As with ji, “it is the visitors’ recognition of a place as a xu that stimulates emotion and thought.”35 And like traces, ruins not only inspire subjective reactions, but can also drive visitors like Yu Xie to look past the emptiness of the site to the materiality of the ruin as a thing that can be restored to its original state and inscribed with important cultural values.

For Yang Su and Huang Tingjian, it is the values of a literary tradition exemplified by Du Fu and his poetry rather than a physical structure that are in a state of ruination. To revive them, however, requires the construction of a physical site of worship that materializes the right kinds of reading and writing. Skill in determining the author’s “intention” (yi 意)—both by paying meticulous attention to the original text and by looking beyond it to its sources and context of composition—was an indispensable first step. In Huang’s essay on the Hall of the Great Odes, both comprehension and revival are figured as spatial practices of “ascending the hall” (shengtang 升堂) and “entering the room” (rushi 入室), phrases borrowed from the Analects of Confucius, where they describe the stages of a student’s assimilation of the master’s teachings.36 This upward journey, from the dirt to the master’s inner sanctum, is enabled by the construction of the Hall, but it is by no means assured. It is only by approaching Du Fu through the foundational texts of the literary tradition—a hermeneutic recommendation concretized by the inscription of his poetry within a structure named after the poetry of the Book of Odes—that one can capture their “greater purpose” and avoid tossing the entire tradition into the dirt.

For Yu Xie, writing twenty-six years after Lu You penned his celebration of Li Xiang and nearly a century after Huang Tingjian’s essay on the Hall of the Great Odes, the shrine to Du Fu at Dongtun was neither a “trace of the past” (guji) nor a “lingering trace” (yiji), but a ruin (xu) totally “incapable of bringing about the intended effect of inspiring one to yearn for worthies and venerate moral virtue” (wuyi zhi sixian shangdezhi yi 無以致思賢尚德之意).37 Conveniently, at this time, Li Xiang was looking to sell his property, so one of Yu Xie’s friends donated the necessary funds and placed the land under the control of the local government. The men then set about restoring its buildings and grounds until it became one of the finest sites in all of Kuizhou. In the same essay, Yu Xie complains that by allowing Du Fu’s Dongtun lofty retreat to decay, Kuizhou had failed to maintain a sense of historical propriety (quedian 缺典).38 For Yu Xie, reconstruction was about far more than promoting sites of local interest for the casual tourist: “As for this labor [shiyi 是役], how could it have been carried out simply for the sake of wandering and gazing [youguan 游觀; i.e., pleasure travel]!”39 Du Fu had long since come to surpass mere literary fame. He was a man who embodied the values and intentions of the classics, “never forgetting his sovereign, even for the space of a meal.”40 When Yu praises his friends’ role in reconstructing the lofty retreat, he uses the language of cultural revival, rather than architectural repair, proclaiming that “they alone were able to revive [xing 興] 400 year old ruins [yizhi 遺趾] and make them new [gengxin zhi 更新之].”41

If Du Fu was important for more than his poetry, it is little wonder that the structures that were built to memorialize him could become more than buildings and the images placed therein more than representations. As sites for the veneration of moral virtue and objects of worship, they were essential to the sacralization of Du Fu. In an essay commemorating the renovation of Du Fu’s famous thatched hall in Chengdu, the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) writer Yang Tinghe 楊廷和 (1459–1529) places Du Fu squarely within a lineage of figures who have been “universally worshipped [si 祀] in antiquity as in the present” in Sichuan. That Du Fu, “who was merely an impoverished refugee, is arrayed loftily alongside” men famous for “great deeds and virtue [gongde 功德]…is truly not just because of his poetry.”42 Du Fu is more than an object of worship; he is an object of worship in Shu, arrayed alongside famous Shu men of the ages.43

The perpetuation of this geographically specific tradition of worship, whether by Yang Tinghe in the Ming, Yu Xie in the Southern Song, Huang Tingjian in the Northern Song, or Qianlong in the Qing, ensured that Du Fu would always be at home in Shu, despite the fact that he had so often ached to leave the south. If Du Fu was forced to share the “clouds and mountains” of Kuizhou with the tribes of the Five Streams, those who worshipped his traces experienced a landscape that was no longer defined by its peripheral heterogeneity.44 The collective acts of spatial inscription that they carried out served as a means of promulgating a new moral and literary orthodoxy from a point in time and space central to Han culture. It also created an entirely new set of traces and itineraries, those grooved and creatively “regroove[d]” by the men and women who traveled to find Du Fu in the landscape, often from the comfort of their studies.45

Instead of textually mapping unfamiliar places (and possibly making them famous in the process), Fan Chengda, Lu You, Yu Xie, Yang Tinghe, and their peers judged the appearance of the landscape against well-known literary works and narratives, and in the case of Du Fu’s former homes, laid out the coordinates of a route for cultural pilgrimage.46 By actively contributing to the production of spaces of tourism and worship, their writings also changed how certain people experienced the landscape. To produce a site of worship legitimated by its status as historical trace was to help foster a moral way of seeing and being in the world. Viewed from this perspective, the qualities of objective observation and description often attributed to Song travel writing in general, and to the essay in particular, seem inadequate. Rather than simply evidence of an objective embrace of gewu 格物 (the “thorough investigation of things”), observation and the modes of reading and writing it supported were tools in the active production of sites and landscapes of cultural devotion.47

For Lu You and Yu Xie, the essay form helped to produce Dongtun as a site of cultural devotion. Since what mattered most was the active creation of a sense of presence through worship, neither writer worked very hard to confirm that Du Fu had actually lived there. Lu You describes the scenery as “very reminiscent,” but he relies primarily on Li Xiang’s claims, which once reproduced in his essay, acquire the air of historical fact. With Yu Xie’s arrival, this historical fact becomes an official one that is repeated through the ages. This is a serious problem for xiandi scholar Jian Jinsong, who suggests that Li Xiang’s story about Dongtun and its Tang-era documents was fabricated to improve his reputation.48 Setting aside the impossibility of judging Li Xiang’s motives from a distance of more than eight hundred years, why does any of this matter? What might we gain from pinpointing the “real” location of Du Fu’s Dongtun home?

We will never know if Li Xiang was as devious as Jian believes him to have been, though it is safe to assume that Lu You and Yu Xie believed his land had once belonged to Du Fu. At the very least, if they had doubts, they kept them to themselves. Their goal was not to prove or disprove Li Xiang’s claim, but to reinscribe Du Fu in the landscape made famous by his poetry. Through this reinscription, the men who wrote about and restored Du Fu’s Dongtun house helped produce a space imbued with meaning and authenticated through pilgrimage and worship. As Yu Xie’s essay makes clear, textual inscription and the reinscription of physical traces on the surface of the earth often went hand in hand. The ji 記 (essay/record) does not simply spread word of the authentic ji 跡; it helps to produce it.

⋆

The history of Dongtun after Du Fu’s death shows how questions of authenticity and spatial continuity are shaped by ritual and worship. There are still pilgrims today to demonstrate this. In his 2015 book, Finding Them Gone: Visiting China’s Poets of the Past, the American translator and poet Bill Porter—who also goes by the Buddhist penname Red Pine (Chisong 赤松)—chronicles a thirty-day pilgrimage to sites associated with poets across China, interspersing a prose travelogue with translations of famous poems written at the sites he visits. As part of his search for “source[s] of inspiration,” Porter seeks out the tracks of the ancients in order to see what and how they saw and to commune with them spiritually by offering libations of whiskey.49

When he travels to Fengjie, the city known in the Tang as Kuizhou, he makes two stops. First, he follows in Fan Chengda’s footsteps to Baidicheng, where he finds a “replacement…carved out of rock near the summit” for Du Fu’s original lofty retreat, which is now submerged.50 For his second stop, he uses none other than Jian Jinsong’s xiandi book to search out Du Fu’s Dongtun property, which he also estimates to be some “fifty meters below the water level.”51 Porter’s project would be impossible without a strong faith in the authenticity of the many “present sites” and “former homes” scattered throughout China. His search for Du Fu seems to prove this faith, but what he does at Dongtun transcends the assumptions of xiandi scholarship. Porter arrives not only to find Du Fu “gone,” but also to discover the erasure of the landscape he made so famous. While it proves impossible to retrace Lu You and Yu Xie’s footsteps to Li Xiang’s Dongtun shrine, Porter inscribes a new site of worship, climbing down a “dirt ridge for several hundred meters” and offering his whiskey to the roots of an orange tree as “intermediary.”52 The search for poets of the past is a search for such intermediaries—objects in the landscape made numinous by faith.

THE DANGERS OF LAZY READING

Few thinkers concerned with the links between specific places and poetic intentions could imitate Yu Xie and Huang Tingjian in constructing a physical site that spatialized the steps leading toward correct interpretation. Yet anyone with the proper training could draw on a set of scholarly practices—described variously as bian 辯 (adjudicate, clarify), kao 考 (investigate, research) and xiang 詳 (explain thoroughly, explicate)—that were designed to support accurate interpretation. It is these practices, combined with observations made in the course of travel, that allow Fan Chengda and Lu You to combat questionable interpretations of Du Fu’s poetry, often by comparing poetic landscapes against the physical spaces on which they were supposedly based. Given the otherworldly appearance of its cloud-shrouded landscapes and its evocatively ambiguous poetics, the Three Gorges region was ripe for this type of adjudication, perhaps because it resisted it so enticingly. Efforts to correct faulty readings entailed not only the demystification of the landscape through the collection of accurate topographic information, but also the reinterpretation of older textual sources and the creation of new ones.

Fan Chengda and others carried out just such a reform project on the goddess of Mt. Wu and the Chu poet Song Yu, the subject of Du Fu’s second poem in the “Singing My Feelings on Traces of the Past” series.53 They sought to clear the erotic clouds that had cloaked the goddess for over a millennium and to fundamentally change how people looked at and represented the landscape of the Three Gorges.54 As described in the preface to Song Yu’s “Gaotang Rhapsody,” the goddess is an endlessly changeable being who once shared her bed with a king of Chu:

Once in the past, King Xiang of Chu and Song Yu were strolling the terrace at Yunmeng and gazed at the Gaotang tower, the top of which was covered by clouds and mists, rising peak-like to the apex, when suddenly the appearance [of the vapors] changed and in the briefest span began to mutate and transform ceaselessly. The King asked Yu: “What manner of qi is this?” Yu responded: “These are the so-called morning clouds.” The King said: “And what are morning clouds?” Yu said: “Once in the past, when the previous king was wandering around Gaotang, he grew fatigued and took a nap during the day. In a dream he saw a woman who said: “I am the lady of Mt. Wu; the sojourner of Gaotang. I heard that milord was wandering around Gaotang and wished to offer you my pillow and mat.” The King thereupon honored her with his company. Parting, she took her leave and said: “I reside on the sunny side of Mt. Wu and on the treacherous reaches of Gaoqiu. At daybreak I am the morning clouds, at dusk the driving rain. Morning after morning, evening after evening I am here beneath the Yang Terrace.” The next morning he looked for this and it was as she had said.55

For millennia, writers have embraced the goddess and her lore as a rich source of erotic imagery, an approach that continues to this day, as evidenced by the many pages of kitschy semi-pornographic images of the goddess generated by a simple internet search for Wushan shennü 巫山神女.56 For as long as the goddess has been an erotic figure, however, scholars have taken pains to note that Song Yu’s “Gaotang Rhapsody” is not an erotic poem, or at the very least, that it does not promote sensuality.57 For some, the scenario described by Song Yu, with its mingling of worlds and its suggestion of kingly negligence, offered a negative example through which to establish the bounds of sexual propriety.58

Since at least the Tang, writers have worked this skeptical tradition into their poetic treatments of Mt. Wu and the goddess, arguing that Song Yu’s account is either woefully misleading or embarrassingly misunderstood. One scholar links this approach to the influence of Song Dynasty Neo-Confucianism, which sets up a strict distinction between humans, who experience desire and emotion, and spirits, which do not.59 This is close to the argument that Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850–933) offers in his collection of biographies of Daoist goddesses and saints, the Record of the Assembled Immortals of the Round Citadel (Yongcheng jixian lu 墉城集仙錄), which identifies the goddess as Yaoji 瑤姬, official title Lady Cloudflower (Yunhua furen 雲華夫人).60 According to Du’s account, which was repeated almost verbatim in Li Fang’s 李昉 (925–996) Taiping guangji 太平廣記, “Song Yu wrote his goddess rhapsodies [shenxian fu 神仙賦] to allegorize his passions [yuqing 寓情], [in the process] debauching and besmirching the most illustrious and perfected high immortal. How else could this slander have descended on her?”61

In Du’s Record, Yaoji becomes a skilled practitioner of the Daoist arts of transformation who decides to reside on Mt. Wu after passing the mountain and becoming enamored of its spectacular scenery. Sometime after settling there, she meets Yu the Great, who, in the midst of forming the Three Gorges, was beset by a mysterious wind and interfering demons near Mt. Wu. Unable to finish his work, Yu requests Yaoji’s help, and the goddess responded by “presenting Yu with a stratagem in the form of a text for summoning the hundred spirits and ordering her [attendant] spirits…to help Yu split stones and clear a way for the waves, to relieve blockages and carve a channel through obstructions in order to follow the water’s flow.”62

Du Guangting’s focus on the violation of the goddess is typical of a revisionary approach with precedents in Tang poetry. In an early example, Li Bai describes the goddess as approaching the king of Chu “without desire” (wuxin 無心) and asks his readers:

| 茫昧竟誰測 |

Who will finally fathom this confusing muddle |

| 虛傳宋玉文 |

This fantasy transmitted by Song Yu’s writing63 |

Devoid of the moralistic tone of Du Guangting’s Record, Li Bai’s eighth-century poem describes the entire encounter between the goddess and the Chu king as a humorously empty fantasy transmitted as fact by Song Yu’s writing. It does so by drawing on a strain of doubt that hinges on the mystifying relationship between reality and illusion, waking and dreaming and the world objectively observed and as seen through texts. Doubt and ambiguity are highly conventionalized characteristics of poems on Mt. Wu, especially those collected under the title “How High Mt. Wu” (Wushan gao 巫山高) in Guo Maoqian’s 郭茂倩 (b. 1094) famous anthology of Music Bureau (yuefu 樂府) poetry.64 Most of these highly intertextual poems, written between the sixth and tenth centuries, use the ambiguous qualities of the landscape to heighten its atmosphere of erotic possibility and suspense. Others, however, reject familiar clichés, demystifying the mountain’s clouds and rains and complaining that more than a thousand years of slander had been heaped on the goddess and the kings of Chu.65

In the Song Dynasty, doubts about the erotic nature of the Goddess came to inspire a more careful investigation of the language of the rhapsodies attributed to Song Yu. Before even traveling through the Three Gorges, Fan Chengda had written a preface to a poem in which he reappraised the final lines of Song Yu’s “Goddess” rhapsody:

Previously, when I investigated Song Yu’s talk of “morning clouds,” [and the common claim] that it slandered the kings of ancient times, I discovered it to have absolutely no basis in fact [benwu juyi 本無據依]. As for King Xiang’s dreaming [of the goddess] and his ordering [Song] Yu to compose a fu, [the text] only says: “Her face turned red in anger and she held fast to herself, never could she be trifled with in such a manner [頩顏怒以自持, 曾不可乎犯干]!”66 Later generations did not look into this carefully, uniformly besmirching [Song Yu and the goddess] with their slander…Who will counter all of this baseless derision?67

The playful poem that follows this preface was written in response to a poem by Fan’s friend, which was itself inspired by a painting of Mt. Wu owned by another acquaintance. It presents a capsule history and a symbolic geography for both the spread of a licentious interpretation of Song Yu’s rhapsodies and also for the influence of that licentiousness on poetic representations of other goddesses. In the first half of the long poem, Fan echoes the erotic imagery and language that have made Mt. Wu famous, while also casting doubt on the “standard theme”:

| 瑤姬家山高插天 |

Yaoji’s mountain home—so high it pierces the heavens |

| 碧叢奇秀古未傳 |

Of the exquisite fineness of its emerald groves, since antiquity nothing has been transmitted |

| 向來題目經楚客 |

Without break, a standard theme has come down to us from that wanderer of Chu [Song Yu] |

| 名字徑度岷峨前 |

Whose name has spread straight past Mt. Min and Mt. E |

| 是邪非邪莽誰識 |

But is it true or is it false? Who can comprehend this muddle?68 |

| 喬林古廟常秋色 |

Lofty forests and ancient shrine—forever the color of autumn |

| 暮去行雨朝行雲 |

At dusk departs the driving rain, at dawn come scudding clouds |

| 翠帷瑤席知何人 |

Verdant canopy and jasper mats—do you know to whom they belong? |

| 峽船一息且千里 |

Gorge boats in a breath’s span cross one thousand li |

| 五兩竿頭見旛尾 |

At the ends of paired poles appear pennants’ tips |

| 仰窺仙館至今疑 |

Gazing up to sneak a look at the immortal’s lodge—to this day one remains unsure |

| 行人問訊居人指 |

The traveler makes his enquiries, the locals point the way |

The always-autumnal landscape that Fan describes is the composite product of language and imagery borrowed from earlier poems and texts. Even the mountain’s “emerald groves” (bicong 碧叢) come from a “How High Mt. Wu” poem by the Tang poet Li He 李賀 (790–816).69 What those texts have not communicated, however, at least according to Fan, is how “marvelous and fine” the mountain’s trees are. Inspired by hackneyed accounts of Yaoji’s sensuality, travelers look past the lush greenery to sneak a prurient look at the goddess’s home. When they cannot locate it, they turn to locals, who are only too happy to point the way. In lines 11 and 12, Fan reenacts the dubious pointing that closes out Du Fu’s poem on Song Yu. Whereas Du Fu’s travelers failed to understand how one might embody immaterial traces of the past, Fan Chengda’s have failed even to understand the texts that draw them to the landscape.

In the second half of the poem, Fan explains that the popular understanding of the goddess is based on a sloppy reading of Song Yu’s poem that has been “carelessly spread” (langchuan 浪傳) by “hungry travelers, their eyes ever cold” (jike yan changhan 飢客眼長寒), through the “How High Mt. Wu” poems. Like the “palaces of Chu” and Song Yu’s home in Du Fu’s poem, Mt. Wu of the “How High Mt. Wu” tradition hovers between past and present and illusion and reality, inspiring travelers to seek and locals to point the way, even though their shared object always eludes them. This indeterminacy finds expression both in the lingering “wonder” (another possible meaning of yi 疑) that surrounds the location of the Yang Terrace or the Gaotang tower and the sense of doubt that surrounds the story itself.

If Li Bai’s poem represents a charming exception to the erotic tradition of Mt. Wu poetry, Fan Chengda’s represents a direct attack on it. Fan tries to rehabilitate not just the kings of Chu and the goddess of Mt. Wu, but also Song Yu, whom he sees as a victim of poor reading comprehension. In both his preface and his poem, Fan singles out readers and writers who neglected to “investigate” (cha 察) both the intent and the wording of Song Yu’s rhapsodies, thereby spreading “slanderous language” (xieyu 媟語) and “silly talk of boys and girls” (ernü yu 兒女語) in their own poems. The implications of this failure to read and write correctly are by no means limited to Mt. Wu: Fan identifies it as the origin of a wantonness that spreads, through space and time, and from literary woman to literary woman, till it reaches even the Milky Way and its lonely weaving girl, who becomes a popular figure for romantic longing.

What Fan neglects to mention in his poem on the Mt. Wu painting are any texts—aside from Song Yu’s rhapsodies—that might support his assertions. This changes when he is finally able to visit a temple across the river from Mt. Wu, where he finds stone inscriptions that tell the story of Yaoji’s role in helping Yu the Great carve out the Three Gorges. In the preface to the “How High Mt. Wu” poem that Fan writes to commemorate his visit, he stands by his earlier poem: “in investigating [kao 考] the intent of Song Yu’s rhapsodies, I judged [bian 辨] the matter of Gaotang with extreme thoroughness [shenxiang 甚詳].”70 The stone inscriptions not only confirm this, they also make it possible for him to put an end to both the doubt and the erotic wonder that define the “How High Mt. Wu” poems. Fan does not name the inscribed texts that support his conclusions in his poem and preface, but he does provide more detailed information in the travel diary entry that he wrote at the same time:

The Goddess’s Temple is located atop a small ridge on the bank opposite the peaks [of Mt. Wu]…. A stone carving within the present-day temple cites the Yongcheng ji: “Yaoji, daughter of the Queen Mother of the West, was called The Perfected One of Cloud and Flower. She assisted Yu in driving out the ghosts and demons [from the area of the Gorges] and in cutting through the stone to let flow the waters.” Having merit, she was memorialized in writing [yougong jianji 有功見紀] and is now enfeoffed as the Perfected One of Miraculous Efficacy.71

Du Guangting’s Record provides Fan with an alternative history that is based on deeds of action inscribed in the landscape of the Gorges rather than on clouds gyring atop the mountain.

Referring to her assistance of Yu and her inclusion in Du Guangting’s text, Fan Chengda writes: “having merit, she was memorialized in writing.” This phrase is key to both Fan’s interest in Yaoji and to our understanding of how authors inscribe historical and mythical figures in the landscape through the correct types of reading and writing. In this case, Fan uses the word ji 紀 (to record, to be included in a historical record), which is cognate with and often used interchangeably with ji 記 (write, record; essay), to refer to the stone inscriptions of Du Guangting’s text that fill the goddess’s temple. The version of the goddess’s life contained in those inscriptions differs from the salacious account found in the many texts that misread Song Yu’s rhapsody. Du Guangting does describe her famous capacity for transformation—into clouds and mists, rocks, dragons, and countless other forms—but balances it with the monumental permanence of Yu the Great’s flood control project. In the previous chapter, I described how Yu’s feats and the landscape they produced are classified not only as his traces—his literal footprints and axe marks—but also as marks of his meritorious deeds. Though the surface of the earth is inscribed with the traces of Yu’s and Yaoji’s deeds, and though Du Guangting has described the true history of their connection, careless travelers and readers have preferred to cover their eyes with the clouds and rain of poetic lore.

Fan Chengda responds by invoking a form of writing—the record of merit carved in stone and embedded in the landscape—that reflects the goals of his larger literary project. Like his travel diary and the poems that he wrote alongside it, these inscriptions on stone, if read correctly, force readers to reconsider a physical landscape they had previously known only through faulty practices of reading and writing. Both ji 紀 (to record) and ke 刻 (to inscribe) are inscriptional practices that function primarily to memorialize and preserve a text that makes accurate interpretation possible. For Fan Chengda, Du Guangting’s record and its inscription in the goddess’s temple beneath Mt. Wu supply him with the textual evidence he needs to redeem the goddess and her mountain. It is no coincidence that he cites these inscriptions in the preface to his own “How High Mt. Wu” poem. As he makes clear in the poem itself, he does so to replace the ambiguous clouds and mists of a misguided erotic tradition with the stony permanence of the Gorges as traces of heroic acts carried out by “the perfected one of the west” (the goddess) and Yu:

| 西真功高佐禹跡 |

How lofty the feats of the perfected one of the west, who helped to produce the traces of Yu |

| 斧鑿鱗皴倚天壁 |

So that the scaly marks of ax and chisel could rest on these heaven-soaring cliffs72 |

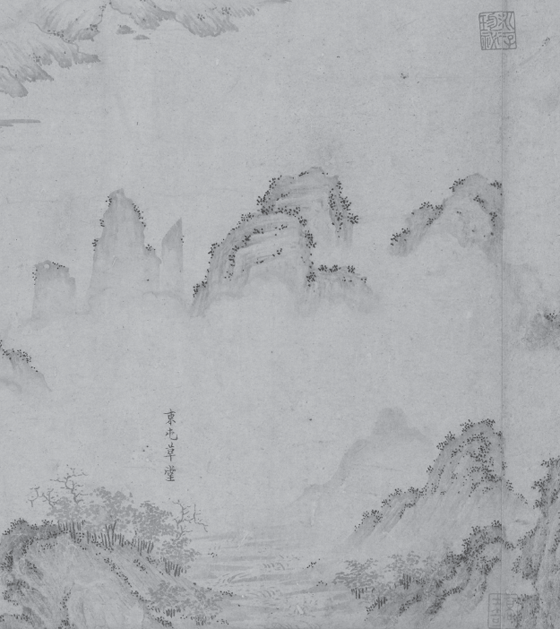

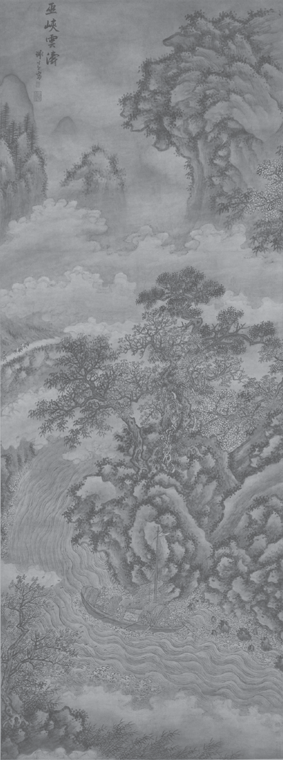

In his first poem on Mt. Wu, Fan Chengda attempts to capture the materiality of the mountain, to offer a vision of the landscape as more than just a figure for the goddess’s transformations. By emphasizing the hitherto neglected fineness of the mountain’s “emerald groves,” Fan not only suggests that there are topographic truths that lie beneath the shapeless mists of innuendo, he also reminds us that his initial topic is not the goddess or King Xiang of Chu, but a painting of a mountain dotted with trees. It is hard to say with any certainty what this painting of Mt. Wu would have looked like. At the very least, its presence in the narrow confines of the Wu Gorge would seem to pose significant challenges for artists. In The Shu River handscroll, the Wu Gorge is depicted from a distance with what appears to be a combined aerial and low-angle perspective (figure 2.4). In a sixteenth-century hanging-scroll painting of the Wu Gorge in the collection of the Cleveland Art Museum, the landscape is dramatically elongated and includes a boat struggling across dangerous rapids (figure 2.5).

FIGURE 2.4 The Shu River (detail): The Wu Gorge.

Source: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1916.539

FIGURE 2.5 Clouds and Waves in the [Yangzi] Gorge of Wushan, Xie Shichen 謝時臣 (1487–ca. 1560); hanging scroll, ink and light color on paper.

Source: Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1968.213.

To date, I have not been able to identify a single extant painting solely dedicated to the depiction of Mt. Wu or the Wu Gorge from the Song, though it is clear from poetic evidence that the mountain was a pictorial theme as early as the eighth century,73 and Fan’s poem is proof that the tradition of “Mt. Wu paintings” (Wushan tu 巫山圖) paintings continued into the Song. While we may never know exactly what such paintings looked like, we can be sure that most of them failed to satisfy Fan Chengda. In his final extended discussion of Mt. Wu, in his travel diary, he complains that painters of this landscape consistently failed to capture its changeable weather:

At Mt. Wu’s finest spots, no matter whether dark or bright, there are always clouds and mists belting the mountains with their shadows and scudding gently about—this [simply] cannot be painted! I have passed beneath it twice and what I have seen has always been like this. Could it be that it just happened to be so when I passed, or is this region really [perpetually] like this? Perhaps the phrase “scudding clouds” even has some basis in fact [yousuo juyi 有所據依]? As for the paintings of Mt. Wu that have come down to us, they are none of them like this; even those in the official lodge in Kuifu do not resemble [the landscape]. I ordered an official painter to take a small skiff out into the middle of the current in order to make a careful copy [moxie 摹寫], which for the first time achieved a formal likeness [xingsi 形似]. Now, as for those images collected by men of catholic tastes, none of them compare to my painting’s verisimilitude [zhen 真].74

A well-known manifestation of the goddess, “scudding clouds” are present not only in the literary tradition, but also each time Fan passes through the Gorges. Surprised by this correspondence between text and reality, Fan wonders if the atmospheric phenomenon might have something to do with the climate and topography of the region. Having established and reestablished the respectability of the goddess, he is excited by the possibility that even this most immaterial trace of the old stories “has some basis in fact.” It is only by actively engaging with the landscape that one can make such observations, a lesson missed by previous artists who have tried to capture this “unpaintable” scene. Even those images embedded in the landscape (collected in the local government office) “do not resemble” (bulei 不類) what Fan sees.

Fan’s poems and diary are built on the desire for such elusively accurate resemblances. He is mostly comfortable achieving them textually, through the thorough description that constitutes his record of action and through his poetry, but there are places in his journey, including Mt. Wu, where text alone does not suffice.75 Through his commission of a new view of Mt. Wu, he hopes not only to surpass other collectors, but also to create (with the aid of a skilled intermediary) a factual image, the product of an act of dedicated copying (moxie 摹寫) that takes place in the landscape that it represents. It is easy to imagine this painting as a pictorial counterpart to Fan’s diary and the many essays and gazetteers that transformed spatial thinking in the Song—reaching for the objective and the accurate, a product of skilled actions executed on the ground (or water). By accurately inscribing the appearance of the landscape, the painting reinscribes the clouds and rains of the goddess as verified traces of regional climate. As a memento of his journey through the gorges, Fan’s painting also fixes the landscape so that he can return to it from the comfort of his garden in Suzhou, just as the emperor Qianlong casts his gaze across the sweep of the Yangzi from the confines of his Beijing palace.

CODA: “TILL LOFTY GORGES RISE FROM A PLACID LAKE”

This book is grounded in the contention that the representational traditions inspired by the Three Gorges can help us better understand how the region has been transformed physically in the past and present. As imaginary and prospective interventions in the material, landscape poetry, prose, and painting, as much as cartography and engineering schematics, embody forms of spatial thinking that mark the horizon of possibility for such changes. In this chapter and the one that preceded it, I have tried to show how landscape representation inscribes values in place, sometimes through acts of spatial production, as in Dongtun or the Yu the Great Mythology Park, and sometimes by trying to change how people perceive landscape.

To change popular visions of Mt. Wu and its goddess, Fan Chengda and others look beyond the conventional landscape imagery of “How High Mt. Wu” poems to capture the “real” appearance of the region in prose, poetry, and painting. Fan’s goal is to restore what he sees as the broken links between materiality, representation, and morality, not to alter the physical landscape. Yet he pursues this goal by reinscribing the goddess into the spatial mythology of Yu the Great. To inspire readers to see Mt. Wu and its goddess again for the first time, he must remake them as a site and force in the production of landscape. Despite their best efforts, Fan and his peers never succeeded in making flood-control activities a compelling alternative to sexual adventures. To this day, the phrase “clouds and rain of Mt. Wu” (Wushan yunyu 巫山雲雨) remains code for sexual intercourse, and the goddess continues to excite the imagination of artists, poets, and filmmakers. Fan’s approach to Mt. Wu, however, shows how the ji/trace can function not only as an evocative aesthetic figure but also as a physical site to be inscribed and reinscribed with values. It is the fame of the landscape and its sites that not only attracts such acts of reinscription, but also, in some cases, contributes to their success. When Mao Zedong invoked the goddess of Mt. Wu in his 1956 poem “Swimming,” he drew on nearly two millennia of erotically atmospheric poetry, prose, and painting. The techno-poetic landscape that Mao describes in the second half of the poem may be a radical departure from the poetry of past centuries, but it draws on a shared vocabulary and set of images:

| 起宏圖 |

I raise a grand plan— |

| 一橋飛架南北 |

A single bridge, flying, will span south and north |

| 天塹變通途 |

Transforming a natural moat into a thoroughfare |

| 更立西江石壁 |

And across the western Jiang we shall erect a wall of stone |

| 截斷巫山雲雨 |

That will rend Mt. Wu’s clouds and rain |

| 高峽出平湖 |

Till lofty gorges rise from a placid lake |

| 神女應無恙 |

The goddess will surely come to no harm |

| 當驚世界殊 |

Though she will have to marvel at how altered is our world76 |

Written in a traditional poetic idiom favored by Mao—the ci 詞, or lyric, which is closely associated with the literature of the Song Dynasty—“Swimming” makes no mention of the people who will be displaced from the Gorges or the engineering feats that it will require. Instead, it repeats the poetic clichés associated with the goddess while claiming that the world no longer needs such a figure, that it has changed. The political and technological change to which Mao alludes is imagined here as a violent assault on the landscape that embodies the goddess. At the center of this rape fantasy is a soaring phallic wall holding back a placid lake, a glossy, reflective surface that naturalizes Mao’s developmental ideology and fixes forever the changeable Yangzi and its Gorges as a national and cultural Chinese landscape.

“Swimming” exemplifies what Ban Wang describes as Mao’s poetic sublime, an “aesthetic of grandeur [that] maintains masculine dominance by suppressing the feminine.”77 In Mao’s poetry, the feminine represents a dissipating force that threatens the telos of revolutionary history, which can only be achieved through heroic acts of sublimation.78 If Fan Chengda dispels the swirling clouds and rain of the “How High Mt. Wu” tradition to expose the lush greenery of the mountains that spread out along the Yangzi’s northern bank, Mao cuts through these sensual images, to the dirt and stones that will support his dam. Both men appropriate and repurpose the erotic tradition to inscribe the landscape with specific values, but as Fu Baoshi 傅抱石 (1904–1965) imagines it in a 1959 painting, Mao’s poetic transformation is also a promise of a massive physical transformation that overshadows the goddess—no less than the landscaping of a modern China and its positioning within a new world order (figure 2.6). As we shall see in Part II, while the cultural importance of the Three Gorges remains undiminished across millennia, it is redefined in the mid-twentieth century in relation to a new set of political, spatial, and aesthetic ideas. The threat of imperialism, the creation of the Chinese nation, the communist revolution, the “reform” of China’s society and economy after Mao’s death—all of these have contributed to the reinscription of the Three Gorges as a modern national and cultural landscape. As in “Swimming,” the “traditional” is an important part of this process, not simply as a foil for the modern, but as a source of tropes and images for a new kind of Chinese landscape.

FIGURE 2.6 The Goddess Will Surely Come to No Harm (Shennü ying wuyang 神女應無恙, 1959), Fu Baoshi 傅抱石 (1904–1965); ink on paper. See also color plate 5.

Source: Nanjing Museum of Art, Jiangsu

If “Swimming” has a special place in the mythology of the Three Gorges Dam, it is because it lends affective and aesthetic weight to the technological development of the Chinese nation. It testifies to the “real world consequences” of literary tropes that “encourage humans to treat [the world] as an inexhaustible storehouse of goods.”79 The wonder of Yu’s dredging, the endless transformations of the goddess of Mt. Wu, and Li Bai’s impossibly swift journey in “Leaving Baidicheng at Dawn” have all helped make possible Mao’s vision of the Yangzi gorges as not only the object of a “great plan,” but also a site of magic easily assimilated to his messianic vision of socialist development. Like Jiang Zemin’s celebration of the “Chinese people’s spirit of tenacious struggle in ‘transforming nature’” that appears as an epigraph to chapter 1, “Swimming” frames the dam project as not just inevitable but as an expression of Chineseness defined in national, cultural, spiritual, and even racial terms.